The Prison-Identity Complex: Unravelling Labour and Law in Identity-Based Prison Worklines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Identifying the Problem: Identity-Based Prison Worklines

2.1. Gender Worklines in Prison

2.2. Racial and Ethnic Worklines in Prison

2.3. Disability and Age Worklines in Prison

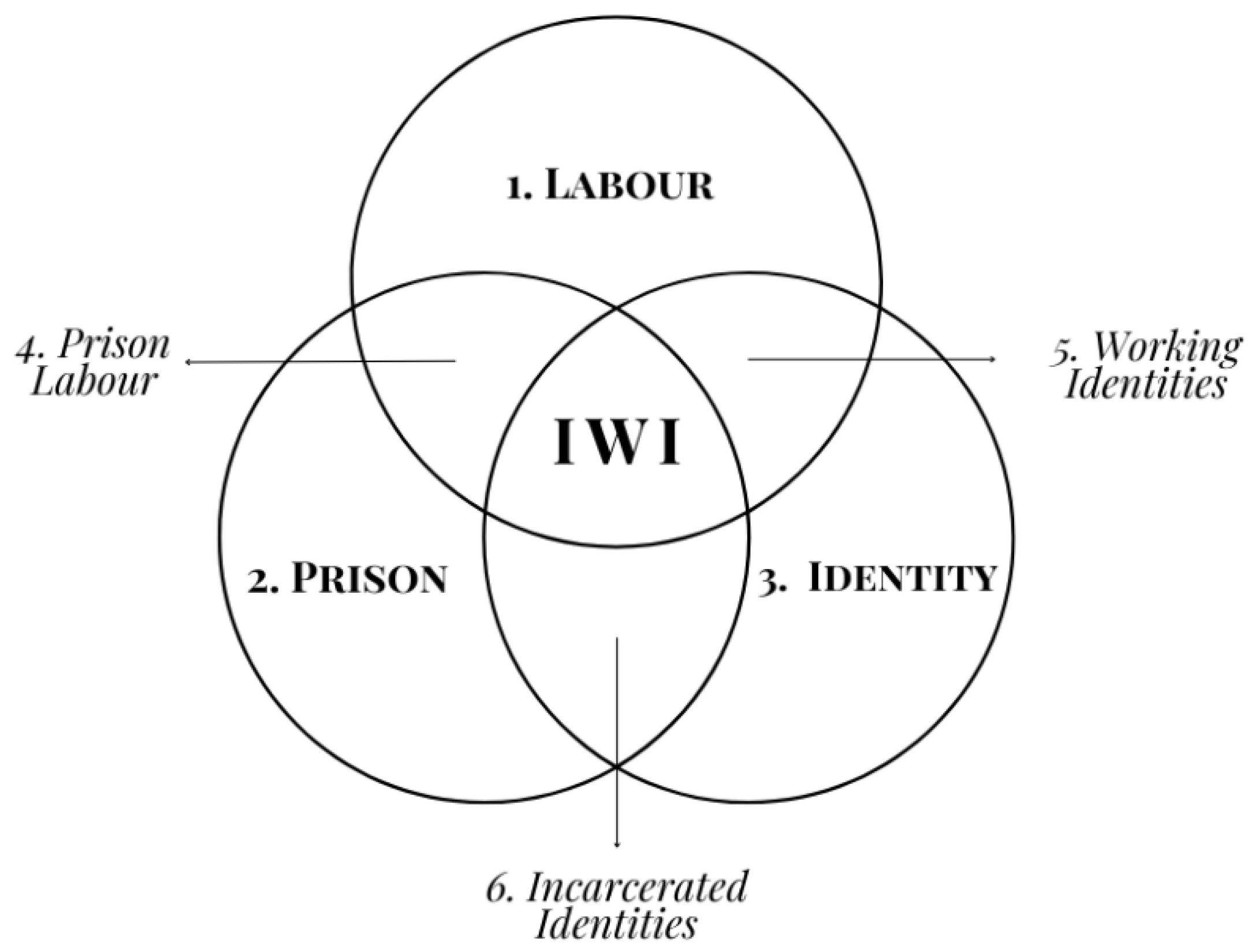

3. Incarcerated Working Identities (IWI): A New Theoretical Model

3.1. Minding the (Scholarly) Gap

3.2. Towards IWI: The Junction of Prison, Labour, and Identity

3.2.1. The Model’s Investigative Focus

- How do prisoners’ identities affect the site of prison labour? This question zones in on the way in which legal and institutional apparatuses of prison labour are divided, structured and re-structured in ways that respond to the identity categories of prisoners-labourers, as well as the ethical and legal implications of that divide. It investigates, for instance, what are the legal ramifications of the segmentation of work within specific facilities and the way in which different work regimes and conditions attach to these divisions.

- How does prison labour affect prisoners’ identities? This question focuses on the myriad ways in which identities are negotiated through prison labour. It explores, for instance, the legal and institutional structures that transform, entrench, or loosen prisoners’ attachment to various identity categories via the mechanism of the work they conduct as prisoners. It inquires how prison labour affects the meaning attached to certain identities and the power various actors in the wider network of prison and prison labour have in shaping this meaning. Finally, it examines the legal and ethical implications of these effects.

3.2.2. A Synergistic and Transformative Approach to Identity

3.2.3. The Model’s Theoretical Methodology

4. Applying the IWI Model to Scrutinise Identity-Based Prison Worklines

4.1. Discrimination

4.2. Identity Re/Construction

“The jobs that they give you kind of put you in a mindset that that’s all you’re going to be good for. In the sense they’ve got, like, bricklaying, plastering, [warehouse], bike shop, and they’re all like…stereotypical to a man…there are people that can draw and can do other things. (Connor)”.(ibid, p. 33).

5. Human Rights Law and Identity-Based Prison Worklines

5.1. Protections Against Discrimination

5.2. Protections Against Identity Re/Construction

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acker, Joan. 1990. Hierarchies, Jobs, Bodies: A Theory of Gendered Organizations. Gender & Society 4: 139. [Google Scholar]

- ACLU, and GHRC. 2022. Captive Labor: Exploitation of Incarcerated Workers. Available online: https://www.aclu.org/publications/captive-labor-exploitation-incarcerated-workers (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Alexander, Michelle. 2012. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Elizabeth. 2017. Private Government: How Employers Rule Our Lives (and Why We Don’t Talk About It). Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anker, Richard. 1997. Theories of Occupational Segregation by Sex: An Overview. International Labour Review 136: 315. [Google Scholar]

- Azinović, Miriam. 2023. Resocialisation Through Prisoner Remuneration: The Unconstitutionally Low Remuneration of Working Prisoners in Germany. Comparative Labor Law & Policy Journal 42: 409. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Gary S. 1985. Human Capital, Effort, and the Sexual Division of Labor. Journal of Labor Economics 3: S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Moshe, Liat. 2020. Decarcerating Disability: Deinstitutionalization and Prison Abolition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter. 1970. On the Obsolescence of the Concept of Honor. European Journal of Sociology 11: 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackett, Adelle, and Alice Duquesnoy. 2021. Slavery Is Not a Metaphor: U.S. Prison Labor and Racial Subordination Through the Lens of the ILO’s Abolition of Forced Labor Convention. UCLA Law Review 67: 1504. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, Louisa, and Daniel Guinea-Martin. 2005. Occupational Segregation by Sex and Ethnicity in England and Wales, 1991 to 2001. National Statistics Feature 113: 501. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, Stefano, and Enrique Alan Olivares-Pelayo. 2021. Carceral Geographies from Inside Prison Gates: The Micro-Politics of Everyday Racialisation. Antipode 53: 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brå. 2015. Work, Education and Treatment in Swedish Prison. Available online: https://bra.se/bra-in-english/home/publications/archive/publications/2015-11-17-work-education-and-treatment-in-swedish-prisons.html (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Bramwell, Richard. 2017. Freedom within Bars: Maximum Security Prisoners’ Negotiations of Identity Through Rap. Identities 25: 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Wendy. 1995. States of Injury: Power and Freedom in Late Modernity. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burrows, Benjamin, and John Crowley. 2019. Disabled Prisoners Are Being Failed by the Current Prison System. Leigh Day Blog, July 29. Available online: https://www.leighday.co.uk/news/blog/2019-blogs/disabled-prisoners-are-being-failed-by-the-current-prison-system/ (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Butler, Judith. 2006. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Carbado, Devon W., and Mitu Gulati. 1999. Working Identity. Cornell Law Review 85: 1259. [Google Scholar]

- Carlen, Pat, and Anne Worrall. 2004. Analysing Women’s Imprisonment. Cullompton: Willan. [Google Scholar]

- Carlen, Pat. (Ed). 2008. Imaginary Penalties. Cullompton: Willan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Philip N. 2013. The Persistence of Workplace Gender Segregation in the US. Sociology Compass 7: 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Hugh. 2024. The Right to Fair Pay and Two Paradigms of Prison Work. European Labour Law Journal 15: 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission for Racial Equality. 2003. A Formal Investigation into HM Prison Service of England and Wales—Part 2: Racial Equality in Prisons. Available online: https://www.statewatch.org/media/documents/news/2003/oct/crePrisons.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Crawley, Elaine, and Richard Sparks. 2005. Older Men in Prison: Survival, Coping and Identity. In The Effects of Imprisonment. Edited by Liebling Alison and Shadd Maruna. Cullompton: Willan, p. 368. [Google Scholar]

- Crewe, Ben. 2009. The Prisoner Society: Power, Adaptation and Social Life in an English Prison. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Crewe, Ben, and Alice Ievins. 2020. The Prison as a Reinventive Institution. Theoretical Criminology 24: 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crittenden, Courtney A., Barbara A. Koons-Witt, and Robert J. Kaminski. 2016. Being Assigned Work in Prison: Do Gender and Race Matter? Feminist Criminology 13: 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangaran, D. 2021. Abolition as Lodestar: Rethinking Prison Reform from a Trans Perspective. Harvard Journal of Law & Gender 44: 203. [Google Scholar]

- Dayan, Colin. 2011. The Law Is a White Dog: How Legal Rituals Make and Unmake Persons. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DodgeMara L. 2002. Whores and Thieves of the Worst Kind. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dolovich, Sharon. 2011. Strategic Segregation in the Modern Prison. American Criminal Law Review 48: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubal, Veena B. 2017. Wage Slave or Entrepreneur: Contesting the Dualism of Legal Worker Identities. California Law Review 105: 65. [Google Scholar]

- Dubal, Veena B. 2023. On Algorithmic Wage Discrimination. Columbia Law Review 123: 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupré, Catherine. 2016. The Age of Dignity: Human Rights and Constitutionalism in Europe. Oxford: Hart Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Emens, Elizabth F. 2012. Against Nature. Nomos 52: 293. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. 2017. Prison Conditions in the Member States: Selected European Standards and Best Practices (European Parliament, Policy Department C: Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs, PE 583.113, 2017). Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2017/583113/IPOL_BRI(2017)583113_EN.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Fenwick, Colin. 2005. Private Use of Prisoners’ Labor: Paradoxes of International Human Rights Law. Human Rights Quarterly 27: 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flömer, Marika. 2020. Women in German Prisons (Civil Society in the Penal System and Turkey’s Center for Prison Studies). Available online: https://cisst.org.tr/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Women_in_German_Prisons.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Foucault, Michel. 1995. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Francisco, Nicole A. 2021. Bodies in Confinement: Negotiating Queer, Gender Nonconforming, and Transwomen’s Gender and Sexuality Behind Bars. Laws 10: 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, Katherine M. 1997. What’s Wrong with Sexual Harassment? Stanford Law Review 49: 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, Nancy. 1995. From Redistribution to Recognition? Dilemmas of Justice in a “Post-Socialist” Age. New Left Review 212: 68. [Google Scholar]

- Fredman, Sandra, and Judy Fudge. 2013. The Legal Construction of Personal Work Relations and Gender. Jerusalem Review of Legal Studies 7: 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frymer, Paul. 2007. Black and Blue: African Americans, the Labor Movement, and the Decline of the Democratic Party. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, David. 2001. The Culture of Control: Crime and Social Order in Contemporary Society. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Garvey, Stephen P. 1998. Freeing Prisoners’ Labor. Stanford Law Review 50: 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genders, Elaine, and Elaine Player. 1989. Race Relations in Prisons. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Light, Michael. 2022. Orange-Collar Labor: Work and Inequality in Prison. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1961. Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. New York: Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, Anthony, and Vincenzo Ruggiero. 2008. Crime, Punishment, and Ethnic Minorities in England and Wales. Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts 2: 53. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, Philip. 2008. “It’s Just Black, White, or Hispanic”: An Observational Study of Racializing Moves in California’s Segregated Prison Reception Centers. Law and Society Review 42: 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, Michele. 2019. The Thirteenth Amendment: Modern Slavery, Capitalism, and Mass Incarceration. Cornell Law Review 104: 899. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried, Heidi. 2015. Why Workers’ Rights Are Not Women’s Rights. Laws 4: 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grana, Sheryl J. 2010. Women and Justice, 2nd ed. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Halley, Janet E. 2002. ‘Like Race’ Arguments. In What’s Left of Theory? Edited by John Guillory, Judith Butler and Thomas Kendall. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Harawa, Daniel S. 2024. In the Shadow of Suffering. Washington University Law Review 101: 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, Jeevan, and Hadassa Noorda. 2024. Imprisoned at Work: The Impact of Employee Monitoring on Physical Privacy and Individual Liberty. Modern Law Review 88: 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatton, Erin, ed. 2021. Labor and Punishment: Work in and out of Prison. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- HM Chief Inspector of Prisons. 2023. Report on an Unannounced Inspection of HMP/YOI Hindley. Available online: https://cloud-platform-e218f50a4812967ba1215eaecede923f.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/sites/19/2024/03/Hindley-web-2023-2.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- HM Inspectorate of Prisons. 2009a. Disabled Prisoners: A Short Thematic Review on the Care and Support of Prisoners with a Disability. Available online: https://lx.iriss.org.uk/sites/default/files/resources/Prisoners_with_Disabilities1.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- HM Inspectorate of Prisons. 2009b. Race Relations in Prisons: Responding to Adult Women from Black and Minority Ethnic Backgrounds, Thematic Report. Available online: https://lx.iriss.org.uk/sites/default/files/resources/Women_and_Race.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Thematic Report by HM Inspectorate of Prisons. 2020. Minority Ethnic Prisoners’ Experiences of Rehabilitation and Release Planning. Available online: https://www.iprt.ie/international-news/hm-inspectorate-of-prisons-minority-ethnic-prisoners-experiences-of-rehabilitation-and-release-planning/ (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- HM Inspectorate of Prisons. 2022. The Experiences of Adult Black Male Prisoners and Black Prison Staff. Available online: https://hmiprisons.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmipris_reports/the-experiences-of-adult-black-male-prisoners-and-black-prison-staff/ (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Hochschild, Arlie R. 2012. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- House of Commons Committee. 2022. Women in Prison. Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5803/cmselect/cmjust/265/report.html (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Howard League for Penal Reform. 2013. Not Hearing Us: An Exploration of the Experience of Deaf Prisoners in English and Welsh Prisons. Available online: https://howardleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Not_hearing_us.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Jenkins, Richard. 2008. Social Identity, 3rd ed. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Karp, David R. 2010. Unlocking Men, Unmasking Masculinities: Doing Men’s Work in Prison. The Journal of Men Studies 18: 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katri, Ido. 2024. The Perils of Gender Self-Determination: Global Shifts in Sex Reclassification Law and Policy. The American Journal of Comparative Law 71: 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Emma. 2018. Segregation by Citizenship. Harvard Law Review 132: 1379. [Google Scholar]

- Kenkmann, Andrea, and Christian Ghanem. 2024. ‘Successful Ageing’ Needs a Future: Older Incarcerated Adults’ Views on Ageing in Prison. Journal of Aging and Longevity 4: 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, Riku, Pekka Martikainen, Mikko Aaltonen, and Mikko Myrskylä. 2025. Industry-Specific Labour Demand, Post-Prison Employment and Recidivism—Evidence from Finland. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammy, David. 2017. The Lammy Review: An Independent Review into the Treatment of, and Black Outcomes for, Asian and Minority Ethnic Individuals in the Criminal Justice System; London: Ministry of Justice. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a82009040f0b62305b91f49/lammy-review-final-report.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Lamont, Michèle. 2002. The Dignity of Working Men: Morality and the Boundaries of Race, Class, and Immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, Rebecca. 2024. A Positive Right to Rehabilitation? An Examination of the ‘Principle of Rehabilitation’ in the Caselaw of the European Court of Human Rights. Human Rights Law Review 24: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBaron, Genevieve. 2012. Rethinking Prison Labor: Social Discipline and the State in Historical Perspective. WorkingUSA: The Journal of Labor and Society 15: 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, Marc. 1987. Farm Workers and the Fair Labor Standards Act: Racial Discrimination in the New Deal. Texas Law Review 65: 1335. [Google Scholar]

- Littman, Aaron. 2021. Free-World Law Behind Bars. Yale Law Journal 131: 1385. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, Catharine. A. 1982. Feminism, Method Marxism, and the State: An Agenda for Theory. Signs 7: 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, David. 2019. Vulnerable Prisoner Masculinities in an English Prison. Men and Masculinities 24: 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantouvalou, Virginia. 2018. The UK Modern Slavery Act 2015 Three Years On. The Modern Law Review 81: 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantouvalou, Virginia. 2020. Welfare-to-Work, Structural Injustice and Human Rights. Modern Law Review 83: 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantouvalou, Virginia. 2023. Captive Workers. In Structural Injustice and Workers’ Rights. Edited by Virginia Mantouvalou. Oxford: OUP, p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- Many Horses v. Racicot, 739 F Supp 1435 (D Mont 1990). ACLU Montana. 1993. Available online: https://www.aclumontana.org/en/cases/many-horses-v-racicot (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- McLennan, Rebecca. 2008. The Crisis of Imprisonment: Protest, Politics, and the Making of the American Penal State, 1776–1941. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McShane, Marilny D., and Frank P. Williams. 1990. Old and Ornery: The Disciplinary Experiences of Elderly Prisoners. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 34: 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melossi, Dario, and Massimo Pavarini. 2018. The Prison and the Factory. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Morash, Merry, Robin N. Haarr, and Lila Rucker. 1994. A Comparison of Programming for Women and Men in U.S. Prisons in the 1980s. Crime & Delinquency 40: 197. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau, Sophia. 2017. Discrimination and Freedom. In The Routledge Handbook of the Ethics of Discrimination. Edited by Kasper Lippert-Rasmussen. Abingdon: Routledge, p. 166. [Google Scholar]

- Morey, Martha, and Ben Crewe. 2018. Work, Intimacy and Prisoner Masculinities. In Perspectives on Prison Masculinities. Edited by Matthew Maycock and Kate Hunt. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan Intimacy and Prisoner Masculinities, p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, Stephanie J., and Kevin A. Wright. 2019. Imprisoned Men: Masculinity Variability and Implications for Correctional Programming. Corrections 7: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarek, Zahid. 2017. Tackling Discrimination in Prison: Still Not a Fair Response. Available online: https://prisonreformtrust.org.uk/publication/tackling-discrimination-in-prison-still-not-a-fair-response/ (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Muhammad, Khalil Gibran. 2019. The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Noorda, Hadassa. 2024. Voluntary’ Prison Labour in The Netherlands. European Labour Law Journal 15: 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshinsky, David. M. 1997. “Worse than Slavery”: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pandeli, Jenna, Michael Marinetto, and Jean Jenkins. 2019. Captive in Cycles of Invisibility? Prisoners’ Work for the Private Sector. Work, Employment and Society 33: 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Fuchs, Amir. 2008. Welfare-to-Work. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Coretta. 2007. Ethnicity, Identity and Community Cohesion in Prison. London: Sage Identity. [Google Scholar]

- Piore, Michal J. 2001. The Dual Labor Market: Theory and Implications. In Social Stratification, Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective, 2nd ed. Edited by David B. Grusky. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ploch, Amanda. 2012. Why Dignity Matters: Dignity and the Right (or Not) to Rehabilitation from International and National Perspectives. NYU Journal of International Law and Politics 44: 887. [Google Scholar]

- Polachek, Solomon W. 1981. Occupational Self-Selection: A Human Capital Approach to Sex Differences in Occupational Structure. Review of Economics and Statistics 63: 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, James G. 2019. Mass Incarceration, Convict Leasing, and the Thirteenth Amendment: A Revisionist Account. New York University Law Review 94: 1465. [Google Scholar]

- Prison System Enquiry Committee. 1922. English Prisons To-day: Being the Report of the Prison System Enquiry Committee. Edited by Stephen Hobhouse and Fenner Brockway. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., Paternoster Row. [Google Scholar]

- Racabi, Gali. 2022. Abolish the Employer Prerogative, Unleash Work Law. Berkeley Journal of Employment and Labor Law 43: 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafter, Nicole H. 1990. Partial Justice: Women, Prisons, and Social Control. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, Adam. 2024. From Hard Labor to Market Discipline: The Political Economy of Prison Work, 1974 to 2022. American Sociological Review 89: 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgeway, Cecilia L. 2011. Framed by Gender: How Gender Inequality Persists in the Modern World. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Dorothy E. 2019. Abolition Constitutionalism. Harvard Law Review 133: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Robin-Olivier, Sophie. 2024. Recent Reforms of Prison Work in France: Stepping Stones on the Way to Equal Rights. European Labour Law Journal 15: 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Dylan. 2019. Abolition as Praxis of Human Being: A Foreword. Harvard Law Review 132: 1575. [Google Scholar]

- Rovner, Laura L. 2001. Perpetuating Stigma: Client Identity in Disability Rights Litigation. Utah Law Review 2001: 247. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, Ashley T. 2019. Early US Prison History Beyond Rothman: Revisiting the Discovery of the Asylum. Annual Review of Law and Social Science 15: 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, Angel E. 2019. In Spite of Prison. Harvard Law Review 132: 1650. [Google Scholar]

- Schouten, Gina. 2019. Liberalism, Neutrality, and the Gendered Division of Labor. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Susie. 2011. Total Institutions and Reinvented Identities. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Amartya. 1999. Development as Freedom. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Shamir, Hila. 2012. A Labor Paradigm for Human Trafficking. UCLA Law Review 60: 76. [Google Scholar]

- Shklar, Judith N. 1990. The Faces of Injustice. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, Reva B. 1993. The Modernization of Marital Status Law: Adjudicating Wives’ Rights to Earnings, 1860–1930. Georgetown Law Journal 82: 2127. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, Jonathan. 2007. Governing Through Crime: How the War on Crime Transformed American Democracy and Created a Culture of Fear. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, Jonathan. 2016. Mass Incarceration on Trial: A Remarkable Court Decision and the Future of Prisons in America. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smoyer, Amy B. 2013. Cafeteria, Commissary and Cooking: Foodways and Negotiations of Power and Identity in a Women’s Prison. Ph.D. thesis, City University of New York, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, Gresham M. 2007. The Society of Captives: A Study of a Maximum Security Prison. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Charles, and Amy Gutmann. 1994. Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Justice. 2019. The Care and Management of Individuals Who Are Transgender. October 31. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/659e906fe96df5000df843e2/transgender-pf.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Thomas, Kendall. 1993. The Eclipse of Reason: A Rhetorical Reading of Bowers v. Hardwick. Virginia Law Review 79: 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 2015. United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners GA Res 70/175. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/documents/justice-and-prison-reform/Nelson_Mandela_Rules-E-ebook.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2015).

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2009. Handbook on Prisoners with Special Needs. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/pdf/criminal_justice/Handbook_on_Prisoners_with_Special_Needs.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2014. Handbook on Women and Imprisonment, 2nd ed. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/documents/justice-and-prison-reform/women_and_imprisonment_-_2nd_edition.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Vagg, Jon, and Ursula Smartt. 1999. England and Wales. In Prison Labour: Salvation or Slavery. Edited by Dirk Van Zyl and Frieder Dünkel. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zyl Smit, Dirk, and Frieder Dünkel, eds. 2019. Prison Labour: Salvation or Slavery?: International Perspectives. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Amy. 2024. The Prisoners Swapping Crime for Dressmaking. BBC News, November 10. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c9xz26g7g74o (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- VanderVelde, Lea. 2022. Modern Employment Law: In Time and Place. St. Paul: West Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant, Loïc. 2009. Punishing the Poor: The Neoliberal Government of Social Insecurity. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walia, Harsha, and Andrew Dilts. 2018. Dismantle and Transform: On Abolition, Decolonization, and Insurgent Politics. Abolition 1: 12. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Michael L. 2016. Race Making in a Penal Institution. American Journal of Sociology 121: 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, David A, and Gene G. Kassebaum. 1965. Women’s Prison: Sex and Social Structure. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Robert P. 2001. Repatriating Low-Wage Work: The Political Economy of Prison Labor Reprivatization in the Postindustrial United States. Criminology 39: 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Theodore Brantner. 1965. The Black Codes of the South. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Tassa. 2016. Gender and Sexuality in Male-Dominated Occupations: Women Working in Construction and Transport. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Yona, Lihi, and Ido Katri. 2020. The Limits of Transgender Incarceration Reform. Yale Journal of Law & Feminism 31: 201. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino, Kenji. 2007. Covering: The Hidden Assault on Our Civil Rights. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Zatz, Noah D. 2008. Working at the Boundaries of Markets: Prison Labor and the Economic Dimension of Employment Relationships. Vanderbilt Law Review 61: 857. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | A Council of Europe study found that 25 of 40 surveyed member states mandate prisoner labour, at least in some circumstances (Mantouvalou 2023). Notably, even in states where prison labour is not legally coereced, incentive structures tied to prison work undermine the voluntary aspect of this work (Hatton 2021; Van Zyl Smit and Dünkel 2019). In The Netherland, for instance, “there is no direct obligation for prisoners to work, but a positive evaluation of their labour is an important aspect in deciding whether they are allowed particular privileges, such as less repetitive and more challenging work options, more possibilities for visits from family and friends, and more time for education.” (Noorda 2024). |

| 2 | In this article, we define prison labour broadly to encompass two main categories: first, service work conducted as part of the prison’s day-to-day maintenance and operations (such as cleaning, food preparation, and laundry services), and second, industrial work performed by prisoners, which may include manufacturing, assembly, or other productive activities often in collaboration with external entities. |

| 3 | Identity is a multifaceted concept, referring to the complex interplay of individual and group characteristics that shape a person’s sense of self. Here, we discuss it in the context of traits prevalent in identity politics and scholarship on socio-legal inequalities, such as gender, race, class, disability, age, religion, nationality, etc. As we detail below, we address both external dimensions of identity (ascribed and institutionally recognised) and internal ones (self-identification and subjective attachment), as well as the dynamic interaction between them. External dimensions often shape how prisons categorise and respond to individuals, while internal ones may influence prisoners’ own preferences and choices, for instance in choosing their work assignments, where their input is sometimes considered. These dimensions are frequently entangled: institutional recognition can shape self-identification, or trigger resistance to imposed labels—a tension we examine as one of the harms in this article. As we discuss below, we additionally complexify the concept of identity and individuals’ attachment to it, building on thinkers such as Wendy Brown and Janet Halley. Finally, we recognise that other social factors, such as gang membership, drug addiction, type of offence, etc. are also highly relevant in shaping prisoners’ self-identification and how they are perceived by others. Exploring all these factors is beyond the scope of this project. Future research may complement our study by exploring additional dimensions of prisoners’ identities. |

| 4 | It is worth noting, however, that by contributing to the substantial body of scholarship documenting carceral harms and interrogating the inherently oppressive nature of penal institutions, our findings simultaneously advance abolitionist discourse. |

| 5 | We build here on Harawa’s lens of human suffering as a methodological tool from which to evaluate debates regarding reform and abolition, ibid, p. 1853; We further echo Angel Sanchez’ metaphor, analogising prisons to a “social cancer.” As he writes: “we should fight to eradicate it but never stop treating those affected by it.” (Sanchez 2019, p. 1652). |

| 6 | Roberts herself draws on Harsha Walia in developing this principle (Walia and Dilts 2018, pp. 14–15). |

| 7 | We refer here mostly to prisoners’ perceived identities, i.e., the external aspect of their identities. However, as we mentioned above, in instances where prisoners have the ability to choose their work assignment, their internal identitiy can also shape their assigned work. |

| 8 | This stereotypical gender dynamic in work assignments, however, should also be complexified, as male prisoners also perform ‘feminine’ work in prison, such as cooking, laundry, and caring for disabled prisoners. |

| 9 | See for instance this quote from the article: “‘At the moment, we’re in the midst of a huge quantity of scrunchies,’ says HMP Downview inmate Suzanne, as she gestures at a pile of hair pieces being put together by seamstresses in the fashion studio.” (ibid). |

| 10 | There is ample research refuting this assumption (e.g., Dolovich 2011). |

| 11 | Rule 4.5 states that “[s]ome individuals who are transgender may need to be placed in a supportive environment, separate from the main regime…”. Rule 4.81 states that some prison facilities “may designate a unit (or units) to hold transgender prisoners separately where this is assessed as necessary under this policy… Prisoners located on any such unit will follow a personalised regime, with access to activities within the main prison regime being risk assessed on an individual basis.” Rule 4.81 of the policy further explains the issue of risk, adding that “[a]ny significant risks posed by a transgender woman to others, or by others to the individual, should be assessed in order to make sure that appropriate accommodation, regime and supervision is provided to manage such risks appropriately.” (The Ministry of Justice 2019). |

| 12 | Their study found the most desirable jobs to be orderly tasks and kitchen work, as well as work in the reception area, while the least desirable were industrial workshop jobs. The distinction between desirable and undesirable jobs in prison hinged on two key factors: the degree of autonomy prisoners experienced during work, and the associated perks, such as coffee or cigarette breaks, access to information, or opportunities to smuggle or trade goods. |

| 13 | ‘Strategy and Resource Guide for the Resettlement of Women Prisoners’ (HM Prison Service 2006), quoted in (HM Inspectorate of Prisons 2009b). |

| 14 | Nevertheless, the report continues, “the investigator added that ethnicity was ‘not taken into account’ in giving out jobs.” (ibid). |

| 15 | Another prisoner was quoted saying: “A lot of the Asians and blacks don’t get the jobs they choose, they always get the prison issued jobs. The white prisoners will often get their own jobs approved.” (ibid). |

| 16 | The report shares several testimonies from incarcerated workers. One illuminating testimony comes from Dolfinette Martin, a formerly incarcerated Black woman: “While incarcerated in Louisiana, she was assigned to manual agricultural labour in the fields. She described how white women worked in ‘prestigious jobs’—the dining hall, housekeeping, or the ‘snack shack’ for visitors. But ‘there weren’t a lot of white girls in the field,’ she observed. ‘The only people who could approach the Deputy Warden to ask for a job were white women,’ she said.” (ibid, p. 52). |

| 17 | As the UN handbook on special needs prisoners states, prisoners with mental health care needs, as well as prisoners with disabilities could be excluded from work opportunities (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2009). |

| 18 | As one elderly German prisoner interviewed by Kenkmann in Ghanem stated: “I’m feeling then excluded, pushed away, not taken seriously. Often it is then so that the younger ones are unreliable and are kicked out of the [work] interventions. I always have to prove that I’m still “useful”, otherwise I’m immediately a goner.” (Kenkmann and Ghanem 2024). |

| 19 | Direct correspondence with the lawyers involved in this case revealed that additional information could not be shared due to confidentiality constraints. |

| 20 | A recent volume dedicated to European prison labour has extensively dealt with the questions of prisoner-workers’ rights, see European Labour Law Journal (2024) 15(3). Some works from this volume specifically deal with the right to work in prison, which is closely related to the debate on prison labour conditions, see for instance (Collins 2024; Noorda 2024). See also (Zatz 2008). |

| 21 | Those include rap music and food practices (Bramwell 2017; Smoyer 2013). |

| 22 | In line with the conceptual framework outlined above, the model examines both external and internal dimensions of identity, as well as the complex relationship between them. Those include how institutional ascriptions shape self-identification, and how, in turn, subjective identifications may inform institutional perceptions and practices. It also attends to the tensions and harms that arise when these dimensions are misaligned. |

| 23 | Acknowledging differences in saliency between them. |

| 24 | Another reason to examine identities synergistically is rooted in the intersectional nature of identities. We acknowledge identity categories are not mutually exclusive. Women, for instance, may be religious or secular, old or young, with or without citizenship status. Accordingly, any attempt to isolate gender from ethnicity, age from nationality, etc. will undoubtedly tell a partial story. The IWI model confronts this challenge by examining various identity traits simultaneously, acknowledging both their interplay and intersection. |

| 25 | Future IWI inspired research could thus question the carceral tendency to segregate between various identity groups into different wings or prison facilities, building, in part, on the way in which this segregation cements identity worklines. |

| 26 | These worklines also draw less legal scrutiny as often they seem to result from prison official broad administrative discretion (Dayan 2011). |

| 27 | See also Dickson v United Kingdom (2007) 44 EHRR 21 at para [32] where the ECtHR acknowledges the problematic tradition of the concept of rehabilitation. |

| 28 | Which emphasises work as a crucial aspect of human capability and freedom. |

| 29 | For instance, in the context of coming out of the closet, receiving gender reaffirming care, etc. |

| 30 | See infra Section 4.1 and Section 4.2. |

| 31 | Scholars have revisited the idea of rehabilitation as encompassing the potential for positive transformative change (Scott 2011; Crewe and Ievins 2020). |

| 32 | Alexander v Home Office, 2 All ER 118 (CA) 120h (1988). |

| 33 | Another case which the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has characterised as discriminatory revolved around a class action filed by women prisoners in Montana during the 1990s, see Many Horses v. Racicot, 739 F Supp 1435 (D Mont 1990). There, female prisoners alleged that they were offered extremely limited jobs, restricted to in-house assignments such as domestic and clerical work, typically occupying no more than a few hours a day. Women with disabilities were completely denied access to such programs. In contrast, men at the Montana State Prison had more extensive opportunities, including a wider variety of work types, longer working hours, and thus better pay. Further, women received no vocational training while men could enrol in various vocational industries: telemarketing, horticulture, industrial arts, motor vehicle maintenance, meat cutting, and business skills. Many Horses v. Racicot (1993) pp. 13–14. The case was settled after the defendant agreed to remedy some of the complaints, see (Many Horses v. Racicot 1993). |

| 34 | For example, in the context of gender segregation, women typically predominate in non-manual professions, while men are more commonly found in occupations requiring manual tasks (Cohen 2013). |

| 35 | Specifically, 60% of women in the workforce are employed in only ten occupations out of 77 total job categories (Wright 2016, p. 18). |

| 36 | While generally, different wages for the same jobs are uncommon in prisons, pay disparities do occur as women and minorities are often channelled into lower-paying jobs. Also note how the transfer of some prison industries to “piece work”, i.e., pay according to productivity, eschews this general principle. |

| 37 | Note, however, the way in which segregation, even when it is horizontal, produces other types of damage such as the strengthening of social stigma on groups. |

| 38 | Of course, extant literature highlights the institutional factors contributing to the construction of workers’ and employers’ preferences (e.g., Acker 1990; Ridgeway 2011). |

| 39 | In most jurisdictions and following International Labour Organization Conventions concerning prison labour, detainees and prisoners who work for private entities must provide their consent to be eligible for such employment. |

| 40 | Simultaneously, structural barriers to employment for women, such as their family responsibilities become mostly irrelevant in the prison context, also diminishing the strength of neo-classical and human capital theory approaches. |

| 41 | These range from losing pay, to other regime benefits such as time outside the cell, etc. |

| 42 | This is not a purely voluntary arrangement among prisoners. While it does reflect some degree of internal identification and collective identity construction (dimensions that we do not wish to ignore) the institutional context within which it occurs is essential. As research on race and incarceration has shown, racialisation in prisons is often amplified through carceral logics that both encourage and enforce racial separation at a level rarely seen outside prison walls (as Goodman himself argues). What may appear as organic self-organisation is often shaped, if not outright engineered, by prison structures. In this particular case, the prison printed the signs “Black barber,” “White barber,” and “Hispanic barber,” supplied the three corresponding metal boxes and the tools for affixing them to the wall, and distributed three distinct sets of haircutting tools. Institutional involvement was thus central not only in enabling, but in materially constituting the racial division of labour within this workline. To that extent, any collective identity at play here must be understood as co-produced by the prison’s racialised architecture of control. |

| 43 | It is quite possible that in other instances as well a biological narrative drives the logic of prison worklines. For instance, the idea that women are incapable of operating heavy machinery, or biologically deterministic ideas regarding prisoners with disabilities. For a critique of this tendency see (Emens 2012). |

| 44 | One key context in which prisoners’ need for recognition in their identity-based transformation arises is among transgender inmates or religious converts, particularly when institutional recognition affects prison conditions. For a discussion on the way prisons construct transgender identity see (Yona and Katri 2020; Francisco 2021). |

| 45 | See rule 2 and rule 5 of the European Prison Rules, as well as Dickson v United Kingdom, Note 27 above, para. [31] (“Rule 2 emphasises that the loss of the right to liberty should not lead to an assumption that prisoners automatically lose other political, civil, social, economic and cultural rights: in fact restrictions should be as few as possible.”). |

| 46 | Notably, as many scholars on dignity have observed, dignity was historically introduced as the progression from honour cultures, described as the “egalitarian step”(Berger 1970). Charles Taylor connects the move toward egalitarian dignity with the collapse of social hierarchies characterising honour cultures (which are intrinsically unequal) (Taylor and Gutmann 1994, pp. 26–27, 42–43). Under this formulation, the connection between dignity and identity re/construction becomes even clearer. If, in honour cultures, one was tied to the status aligned with the identity with which they were born, the move towards dignity was meant to free people from this fixed hierarchy, allowing them to transcend their status. |

| 47 | For a different perspective on the relationship between work and masculinity, see (Gottfried 2015). |

| 48 | Notably, Morey and Crewe also complexify this distinction, noting, for instance, that some tradesmen nevertheless “were often keen to demonstrate a ‘softer’ masculinity, expressing a fondness for cooking or wearing pink” (ibid). |

| 49 | Outside the context of prison labour, research have long acknowledged how racial divisions in prison exacerbate racial animus between prisoners (Walker 2016; Goodman 2008). |

| 50 | Notably, there is ample research demonstrating that legal protections can themselves become mechanisms of identity entrenchment. Plaintiffs often turn to law to seek redress for discrimination or other identity-based harms, hoping to be recognised as entitled to protection. Yet this very process can compel them to perform their identities in ways that are legible to legal institutions (Rovner 2001, p. 250). This is a well-documented and inherent tension in legal identity-based protections. Accordingly, one could argue that offering legal redress for harms such as discrimination and identity re/construction risks reproducing the very dynamics it seeks to challenge. We acknowledge this concern. However, by emphasising prisoners’ procedural freedom, including the ability to decide whether, when, and how to invoke legal protections, we aim to leave space for incarcerated individuals to negotiate this tension themselves, weighing its risks and benefits in light of their own priorities and situated experiences. |

| 51 | Notably, the European Court of Human Rights has “established a doctrine of positive state obligations” See (Mantouvalou 2020, p. 945), meaning that states are obligated to secure the “effective enjoyment” of conventions’ rights. |

| 52 | Future research could cover, for example, the 14th and 8th Amendments of the US Constitution, as well as the American Convention of Human Rights, as possible legal avenues from which to challenge the harms of identity-based prison worklines. |

| 53 | While the EPR are not legally binding, they are followed by many courts, including the European Court of Human Rights. |

| 54 | Shelly v United Kingdom App No 23800/06, [2008] ECHR 108, (2008) 46 EHRR SE16. |

| 55 | This rule has been criticised by scholars for its limited scope, given its reliance on discriminatory intent (Mantouvalou 2018; Shamir 2012). |

| 56 | In a forthcoming article we conduct such critical engagement, demonstrating incongruences between IWI-inspired normative interventions and existing human rights law, as well as a typology of various type of problematic human rights rules that warrant re-examination. |

| 57 | The active duty to secure convention rights could potentially necessitate the creation of identity-transcending job opportunities accessible to all prisoners. However, given the risk raised by abolitionists that reforms or interventions may inadvertently expand or legitimise carceral policies and institutions, this possibility should be addressed with caution. One way to account for this risk would be to demand the replacement of existing structures (rather than their expansion) to afford prisoners greater autonomy in their daily work choices. |

| 58 | Dickson v UK, Note 27 above, para. [55]. This articulation was adopted in other cases, see for instance Murray v The Netherlands [2016] ECHR 10511/10. Note, however, that here The Court nevertheless rests heavily on problematic notions of rehabilitation, tying it to the notion of personal responsibility. |

| 59 | BS v Scottish Ministers, CSOH 47 (2024). |

| 60 | By doing so, courts have invoked abolitionists’ concerns about net-widening and further entrenching the carceral state via the utilisation of seemingly positive values. |

| 61 | No doubt, the ultimate determination of prisoners’ rights remains subject to judicial interpretation, a process which inherently carries the potential for carceral expansion. Nonetheless, in line with our previous discussion, we entrust the management of these risks to the prisoners themselves and those representing them, see (Dangaran 2021). |

| 62 | In a landmark ruling from 2023, Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court has recently ruled that the renumeration rates in two federal states were unconstitutionally low (Azinović 2023). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yona, L.; Milman-Sivan, F. The Prison-Identity Complex: Unravelling Labour and Law in Identity-Based Prison Worklines. Laws 2025, 14, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14030037

Yona L, Milman-Sivan F. The Prison-Identity Complex: Unravelling Labour and Law in Identity-Based Prison Worklines. Laws. 2025; 14(3):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14030037

Chicago/Turabian StyleYona, Lihi, and Faina Milman-Sivan. 2025. "The Prison-Identity Complex: Unravelling Labour and Law in Identity-Based Prison Worklines" Laws 14, no. 3: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14030037

APA StyleYona, L., & Milman-Sivan, F. (2025). The Prison-Identity Complex: Unravelling Labour and Law in Identity-Based Prison Worklines. Laws, 14(3), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14030037