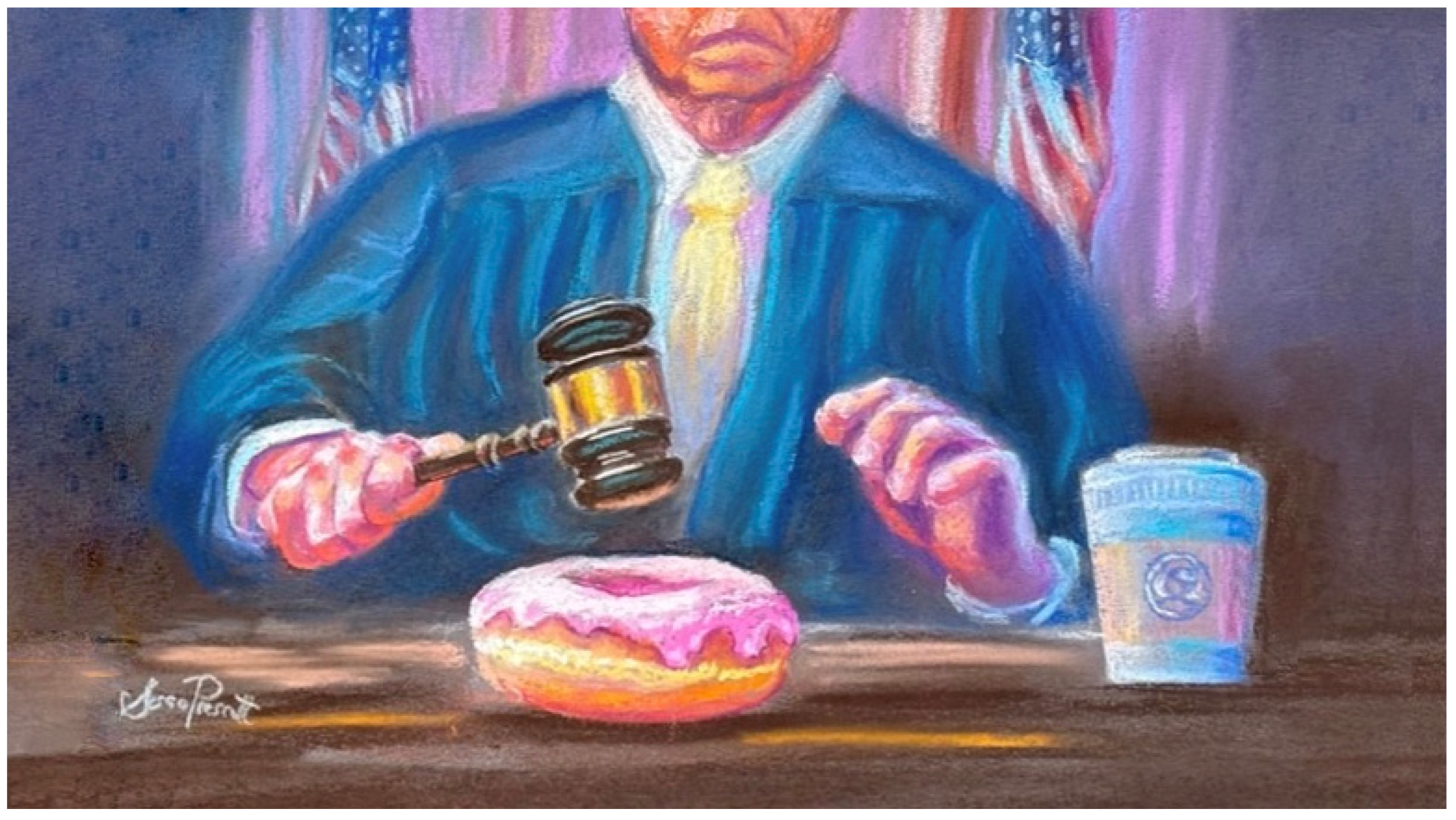

On Gastronomic Jurisprudence and Judicial Wellness as a Matter of Competence

Abstract

1. Introduction

“The length of sentences received by criminals…depends as much upon the condition of the judge’s digestion as upon the enormity of the offense.”Editors of the Waukesha Freeman, 1880 (Anon 1880).

“The object of the law [did not] contemplate that the term of imprisonment should depend, as was suggested by one of our State Prison Directors, on what the judge ate for breakfast.”Judge Noble Hamilton, 1886 (Hamilton 1886).

2. Stress and Burnout in the Courtroom Work Group

3. Hypoglycemia and Self-Control

4. Self-Control Fatigue and the Hungry Judge

“Your lank-jawed hungry judge will hang the guiltless, rather than eat his mutton cold!”William Shakespeare (Cibber 1847)

5. Future Directions

6. Conclusions

“To the students of gastronomic jurisprudence, breakfast foods assume a controlling role: what the judge eats will determine what the Constitution says.”Richard H, Ernst, Yale Law Review, 1937 (Ernst 1937).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abar, Leila, Eurídice Martínez Steele, Sang Kyu Lee, Lisa Kahle, Steven C. Moore, Eleanor Watts, Caitlin P. O’Connell, Charles E. Matthews, Kirsten A. Herrick, Kevin D. Hall, and et al. 2025. Identification and validation of poly-metabolite scores for diets high in ultra-processed food: An observational study and post-hoc randomized controlled crossover-feeding trial. PLoS Medicine 22: e1004560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abiri, Behnaz, Shirin Amini, Hajar Ehsani, MohammadAli Ehsani, Parisa Adineh, Hakimeh Mohammadzadeh, and Sima Hashemi. 2023. Evaluation of dietary food intakes and anthropometric measures in middle-aged men with aggressive symptoms. BMC Nutrition 9: 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adjibade, Moufidath, Chantal Julia, Benjamin Allès, Mathilde Touvier, Cédric Lemogne, Bernard Srour, Serge Hercberg, Pilar Galan, Karen E. Assmann, and Emmanuelle Kesse-Guyot. 2019. Prospective association between ultra-processed food consumption and incident depressive symptoms in the French NutriNet-Sante cohort. BMC Medicine 17: 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrova-Karamanova, Anna, Irina Todorova, Anthony Montgomery, Efharis Panagopoulou, Patricia Costa, Adriana Baban, Asli Davas, Milan Milosevic, and Dragan Mijakoski. 2016. Burnout and health behaviors in health professionals from seven European countries. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 89: 1059–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshabibi, A. S., M. E. Suleiman, K. A. Tapia, R. Heard, and P. C. Brennan. 2020. Impact of time of day on radiology image interpretations. Clinical Radiology 75: 746–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Eric, Desiree R. Delgadillo, Jennifer Yang, Rishabh Agarwal, Jennifer S. Labus, Shrey Pawar, Madelaine Leitman, Lisa A. Kilpatrick, Rvai. R. Bhatt, Priten Vora, and et al. 2024. Stress-resilience impacts psychological wellbeing as evidenced by brain–gut microbiome interactions. Nature Mental Health 2: 935–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anon. 1880. Our State Prison. Waukesha: Waukesha Freeman, January 29, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Associated Press. 1951. Diet ‘trance’ blamed for shoplifting lapse. The Bridgeport Telegram, July 20, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, Roy F., Bradley RE Wright, and David Carreon. 2019. Self-control “in the wild”: Experience sampling study of trait and state self-regulation. Self and Identity 18: 494–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, Roy F., Nathalie André, Daniel A. Southwick, and Dianne M. Tice. 2024. Self-control and limited willpower: Current status of ego depletion theory and research. Current Opinion in Psychology 60: 101882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, Anton S., Sungmin Woo, Doris Leithner, Angela Tong, Marius E. Mayerhoefer, and H. Alberto Vargas. 2024. The “Hungry Judge” effect on prostate MRI reporting: Chronobiological trends from 35′004 radiologist interpretations. European Journal of Radiology 179: 111665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beedie, Christopher J., and Andrew M. Lane. 2012. The role of glucose in self-control: Another look at the evidence and an alternative conceptualization. Personality and Social Psychology Review 16: 143–53. [Google Scholar]

- Benton, David. 1988. Hypoglycemia and aggression: A review. International Journal of Neuroscience 41: 163–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benton, David, N. Kumari, and Paul F. Brain. 1982. Mild hypoglycaemia and questionnaire measures of aggression. Biological Psychology 14: 129–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergonzoli, Katja, Laurent Bieri, Dominic Rohner, and Christian Zehnder. 2024. Hungry Professors? Decision Biases Are Less Widespread than Previously Thought. arXiv arXiv:2408.06048. [Google Scholar]

- Berryessa, Colleen M., Itiel E. Dror, and Bridget McCormack. 2023. Prosecuting from the bench? Examining sources of pro-prosecution bias in judges. Legal Criminol Psych 28: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshyah, Salem, Issam Hajjaji, Wanis Ibrahim, Asma Deeb, Ashraf El-Ghul, Khalid Akkari, Ashref Tawil, and Abdul Shlebak. 2018. The year in Ramadan fasting research (2017): A narrative review. Ibnosina Journal of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences 10: 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldt, Ethan D., Christina L. Boyd, Roberto F. Carlos, and Matthew E. Baker. 2021. The effects of judge race and sex on pretrial detention decisions. Justice System Journal 42: 341–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, Ralph. 1976. Hostility in fantasy: A further test of the hypoglycemia-aggression hypothesis. Aggressive Behavior 2: 257–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovill, Diana. 1973. A case of functional hypoglycaemia—A medico-legal problem. The British Journal of Psychiatry 123: 353–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunsberger, Karin, Richard O. Flamm, and Brian Buckler. 2021. The Relationship between Social Dominance Orientation and Dietary/Lifestyle Choices. Sustainability 13: 8901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bublitz, Christoph. 2020. What Is Wrong with Hungry Judges? A Case Study of Legal Implications of Cognitive Science. Maastricht Law Series 11: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, Bree, James Coyle, Anne Brafford, Donald Campbell, Josh Camson, Charles Gruber, Terry Harrell, David B. Jaffe, Tracey L. Kepler, Patrick Krill, and et al. 2017. Report of the National Task Force on Lawyer Wellbeing: Practical Recommendations for Positive Change. Washington, DC: American Bar Association. Available online: https://lawyerwellbeing.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Lawyer-Wellbeing-Report.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Buden, Jennifer C., Alicia G. Dugan, Sara Namazi, Tania B. Huedo-Medina, Martin G. Cherniack, and Pouran D. Faghri. 2016. Work characteristics as predictors of correctional supervisors’ health outcomes. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 58: e325–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushman, Brad J., C. Nathan DeWall, Richard S. Pond, Jr., and Michael D. Hanus. 2014. Low glucose relates to greater aggression in married couples. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111: 6254–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bystranowski, Piotr, Bartosz Janik, Maciej Próchnicki, and Paulina Skórska. 2021. Anchoring effect in legal decision-making: A meta-analysis. Law and Human Behavior 45: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Press. 1952. Sugar deficiency lowers mentality, jail doctor says. The Gazette, August 23, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Casaleiro, Paula, Ana Paula Relvas, and João Paulo Dias. 2021. A critical review of judicial professionals working conditions’ studies. International Journal of Court Administration 12: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassens Weiss, Debra. 2012. Weight gain is apparently a hazard of the job for lawyers and judges, survey says. American Bar Association Journal. Available online: https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/weight_gain_is_apparently_a_hazard_of_the_job_for_lawyers_and_judges_survey (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Chatziathanasiou, Konstantin. 2022. Beware the lure of narratives: “Hungry judges” should not motivate the use of “artificial intelligence” in law. German Law Journal 23: 452–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Gonglu, Shuang Lin, Shinan Sun, Mengmeng Feng, and Xuejun Bai. 2024. The negative effects of ego-depletion in junior high school students on displaced aggressive behavior and the counteraction of the natural environment. Acta Psychologica 250: 104481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibber, Colley. 1847. Modern Standard Drama: Richard III. New York: Berford and Company Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Clapham, Brian. 1965. An interesting case of hypoglycaemia. Medico-Legal Journal 33: 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Dan, Ronald P. Stolk, Diederick E. Grobbee, and Christine C. Gispen-de Wied. 2006. Hyperglycemia and diabetes in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders. Diabetes Care 29: 786–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Coletro, Hillary Nascimento, Raquel de Deus Mendonça, Adriana Lúcia Meireles, George Luiz Lins Machado-Coelho, and Mariana Carvalho de Menezes. 2022. Ultra-processed and fresh food consumption and symptoms of anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: COVID Inconfidentes. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN 47: 206–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, Isabel, Ângela Romão, Andreia E. Almeida, and Sara Ramos. 2023. Protecting police officers against burnout: Overcoming a fragmented research field. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology 38: 622–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal, Nursel, and Saniye Bilici. 2024. An overview of the potential role of nutrition in mental disorders in the light of advances in nutripsychiatry. Current Nutrition Reports 13: 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danziger, Shai, Jonathan Levav, and Liora Avnaim-Pesso. 2011a. Extraneous factors in judicial decisions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108: 6889–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danziger, Shai, Jonathan Levav, and Liora Avnaim-Pesso. 2011b. Reply to Weinshall-Margel and Shapard: Extraneous factors in judicial decisions persist. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108: E834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelis, Tori. 2023. Continuing Education: Nutrition’s role in mental health. Monitor on Psychology 54: 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- DeVoe, Sanford E., Julian House, and Chen-Bo Zhong. 2013. Fast food and financial impatience: A socioecological approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 105: 476–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeWall, Nathan, Timothy Deckman, Matthew T. Gailliot, and Brad J. Bushman. 2011. Sweetened blood cools hot tempers: Physiological self-control and aggression. Aggressive Behavior 37: 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donohoe, Rachael T., and David Benton. 1999. Blood glucose control and aggressiveness in females. Personality and Individual Differences 26: 905–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, Charles Clay, and Clement Charles Doyle. 2007. Wretches Hang That Jury-men May Dine. Justice System Journal 28: 219–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin, Ronald. 1974. Hard cases. Harvard Law Review 88: 1057–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englich, Birte, Thomas Mussweiler, and Fritz Strack. 2006. Playing dice with criminal sentences: The influence of irrelevant anchors on experts’ judicial decision making. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 32: 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, Ozkan, and Naci Mocan. 2018. Emotional judges and unlucky juveniles. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10: 171–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, Richard. 1937. Judicial statistics and the constitutionality of minimum wage legislation. Yale Law Review 46: 1227–28. [Google Scholar]

- Esquivel, Monica. 2021. Nutrition strategies for reducing risk of burnout among physicians and health care professionals. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 15: 126–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbein, Diana, and Susan E. Pease. 1994. Diet, nutrition, and aggression. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation 21: 117–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forestier, Cyril, Margaux de Chanaleilles, Matthieu P. Boisgontier, and Aïna Chalabaev. 2022. From ego depletion to self-control fatigue: A review of criticisms along with new perspectives for the investigation and replication of a multicomponent phenomenon. Motivation Science 8: 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabayoyo, Lunel J., Dennis V. Madrigal, and Deborah Natalia E. Singson. 2024. Occupational Stress, Psychological Distress, and Coping Strategies of First-Level Judges in the Philippines: Examining the Influence of Demographics and Caseloads. Philippine Social Science Journal 7: 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gailliot, Matthew T., and Roy F. Baumeister. 2007. The physiology of willpower: Linking blood glucose to self-control. Personality and Social Psychology Review 11: 303–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gailliot, Matthew T., Roy F. Baumeister, C. Nathan DeWall, Jon K. Maner, E. Ashby Plant, Dianne M. Tice, Lauren E. Brewer, and Brandon J. Schmeichel. 2007. Self-control relies on glucose as a limited energy source: Willpower is more than a metaphor. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92: 325–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearhardt, Ashley N., Nassib B. Bueno, Alexandra G. DiFeliceantonio, Christina A. Roberto, Susana Jiménez-Murcia, and Fernando Fernandez-Aranda. 2023. Social, clinical, and policy implications of ultra-processed food addiction. BMJ 383: e075354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemesi, Kathrin, Sophie Laura Holzmann, Birgit Kaiser, Monika Wintergerst, Martin Lurz, Georg Groh, Markus Böhm, Helmut Krcmar, Kurt Gedrich, Hans Hauner, and et al. 2022. Stress eating: An online survey of eating behaviours, comfort foods, and healthy food substitutes in German adults. BMC Public Health 22: 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Rachel, Rebeca Eriksen, Deepa Singh, Anne-Claire Vergnaud, Andrew Heard, Queenie Chan, Paul Elliott, and Gary Frost. 2018. A cross-sectional investigation into the occupational and socio-demographic characteristics of British police force employees reporting a dietary pattern associated with cardiometabolic risk: Findings from the Airwave Health Monitoring Study. European Journal of Nutrition 57: 2913–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gketsios, Ioannis, Thomas Tsiampalis, Aikaterini Kanellopoulou, Tonia Vassilakou, Venetia Notara, George Antonogeorgos, Andrea Paola Rojas-Gil, Ekaterina N. Kornilaki, Areti Lagiou, Demosthenes B. Panagiotakos, and et al. 2023. The Synergetic Effect of Soft Drinks and Sweet/Salty Snacks Consumption and the Moderating Role of Obesity on Preadolescents’ Emotions and Behavior: A School-Based Epidemiological Study. Life 13: 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glöckner, Andreas. 2016. The irrational hungry judge effect revisited: Simulations reveal that the magnitude of the effect is overestimated. Judgment and Decision Making 11: 601–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, Ann E., Kenneth M. MacLeod, Brian M. Frier, and Ian J. Deary. 1995. Changes in mood during acute hypoglycemia in healthy participants. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 68: 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Donoso, Clara, Almudena Sánchez-Villegas, Miguel A. Martínez-González, Alfredo Gea, Raquel de Deus Mendonça, Francisca Lahortiga-Ramos, and Maira Bes-Rastrollo. 2020. Ultra-processed food consumption and the incidence of depression in a Mediterranean cohort: The SUN Project. European Journal of Nutrition 59: 1093–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Ja K., Luenda E. Charles, Ki Moon Bang, Claudia C. Ma, Michael E. Andrew, John M. Violanti, and Cecil M. Burchfiel. 2014. Prevalence of obesity by occupation among US workers: The National Health Interview Survey 2004–2011. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 56: 516–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagni, Alyssa J., M. Catherine Prater, Chad M. Paton, and Jamie A. Cooper.Guadagni. 2025. Cognitive function in response to a pecan-enriched meal: A randomized, double-blind, cross-over study in healthy adults. Nutritional Neuroscience, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez García, Ana G., and Carlos M. Contreras. 2023. Anxiety Constitutes an Early Sign of Acute Hypoglycemia. Neuropsychobiology 82: 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Martínez, Carlos, Nancy Babio, Lucía Camacho-Barcia, Jordi Júlvez, Stephanie K. Nishi, Zenaida Vázquez, Laura Forcano, Andrea Álvarez-Sala, Aida Cuenca-Royo, Rafael de la Torre, and et al. 2024. Glycated hemoglobin, type 2 diabetes, and poor diabetes control are positively associated with impulsivity changes in aged individuals with overweight or obesity and metabolic syndrome. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1540: 211–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, Noble. 1886. Punishment: Prevention, fear, and reformation; inconsistencies of law. The Oakland Tribune, December 10, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Allison P., and Maya Sen. 2019. Bias and judging. Annual Review of Political Science 22: 241–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemrajani, Rahul, and Tony Hobert, Jr. 2024. The Effects of Decision Fatigue on Judicial Behavior: A Study of Arkansas Traffic Court Outcomes. Journal of Law and Courts 12: 435–443. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Dennis, William Sargant, and Mollie Heppenstall. 1943. A case of matricide. The Lancet 241: 526–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkinson, Alexander, Anli Zhou, Judith Johnson, Keith Geraghty, Ruth Riley, Andrew Zhou, Efharis Panagopoulou, Carolyn Chew-Graham, David Peters, and Aneez Esmail. 2022. Associations of physician burnout with career engagement and quality of patient care: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 378: e070442-95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holler, Sophie, Holger Cramer, Daniela Liebscher, Michael Jeitler, Dania Schumann, Vijayendra Murthy, Andreas Michalsen, and Christian S. Kessler. 2021. Differences between omnivores and vegetarians in personality profiles, values, and empathy: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 579700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, Julian, Sanford E. DeVoe, and Chen-Bo Zhong. 2014. Too impatient to smell the roses: Exposure to fast food impedes happiness. Social Psychological and Personality Science 5: 534–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Elizabeth J., Tony KT Lam, and Frank A. Duca. 2022. The Gut Microbiome: Connecting Diet, Glucose Homeostasis, and Disease. Annual Review of Medicine 73: 469–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Zhengyuan, Guanghui Chen, Zhongyu Ren, Ling Xiao, Ziyue Chen, Yinping Xie, Gaohua Wang, and Benhong Zhou. 2025. Urolithin A ameliorates schizophrenia-like behaviors and cognitive impairments in female rats by modulating NLRP3 signaling. International Immunopharmacology 151: 114336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, Roland, Alexander F. Schmidt, and Friederike Gerstenberg. 2014. Exploring the interplay of trait self-control and ego depletion: Empirical evidence for ironic effects. European Journal of Personality 28: 413–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, Avi, Mosi Rosenboim, and Tal Shavit. 2021. Time preference under cognitive load-An experimental study. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 90: 101633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juul, Filippa, Niyati Parekh, Euridice Martinez-Steele, Carlos Augusto Monteiro, and Virginia W. Chang. 2022. Ultra-processed food consumption among US adults from 2001 to 2018. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 115: 211–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayyatzadeh, Sayyed Saeid, Safieh Firouzi, Maral Askari, Farzane Mohammadi, Irandokht Nikbakht-Jam, Maryam Ghazimoradi, Mohammad Mohammadzadeh, Gordon A. Ferns, and Majid Ghayour-Mobarhan. 2019. Dietary intake of carotenoids and fiber is inversely associated with aggression score in adolescent girls. Nutrition and Health 25: 203–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirtipal, Nikhil, Youngchang Seo, Jangwon Son, and Sunjae Lee. 2024. Systems Biology of Human Microbiome for the Prediction of Personal Glycaemic Response. Diabetes & Metabolism Journal 48: 821–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto, Ichiro. 2023. Subclinical reactive hypoglycemia with low glucose effectiveness—Why we cannot stop snacking despite gaining weight. Metabolites 13: 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Douglas, Carmen Guenther, and Shelley Rosslein. 2016. Do as I say, not as I do: Lifestyles and counseling practices of physician faculty at the University of Alberta. Canadian Family Physician 62: e393–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kocher, Martin G., Konstantin E. Lucks, and David Schindler. 2019. Unleashing animal spirits: Self-control and overpricing in experimental asset markets. The Review of Financial Studies 32: 2149–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Wenwen, Hui Wang, Jianmei Zhang, Danhong Shen, and Danjun Feng. 2021. Perfectionism and psychological distress among Chinese judges: Do age and gender make a difference? Iranian Journal of Public Health 50: 2219. [Google Scholar]

- Kouchaki, Maryam, and Isaac H. Smith. 2014. The morning morality effect: The influence of time of day on unethical behavior. Psychological Science 25: 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krill, Patrick R., Ryan Johnson, and Linda Albert. 2016. The prevalence of substance use and other mental health concerns among American attorneys. Journal of Addiction Medicine 10: 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, Melissa M., Mojtaba Lotfaliany, Allison M. Hodge, Adrienne O’Neil, Nikolaj Travica, Felice N. Jacka, Tetyana Rocks, Priscila Machado, Malcolm Forbes, Deborah Ashtree, and et al. 2023. High ultra-processed food consumption is associated with elevated psychological distress as an indicator of depression in adults from the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. Journal of Affective Disorders 335: 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sunghee, and Myungjin Choi. 2023. Ultra-Processed Food Intakes Are Associated with Depression in the General Population: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutrients 15: 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennartsson, Anna-Karin, Ingibjörg H. Jonsdottir, Per-Anders Jansson, and Anna Sjörs Dahlman. 2025. Study of glucose homeostasis in burnout cases using an oral glucose tolerance test. Stress 28: 2438699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, Inbar. 2022. Hercules on a Diet. In Judicial Decision-Making: Integrating Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives. Edited by Piotr Bystraowski, Bartosz Janik and Maciej Próchnicki. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 159–77. [Google Scholar]

- Linder, Jeffrey A., Jason N. Doctor, Mark W. Friedberg, Harry Reyes Nieva, Caroline Birks, Daniella Meeker, and Craig R. Fox. 2014. Time of day and the decision to prescribe antibiotics. JAMA Internal Medicine 174: 2029–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Junxiu, S. Yi Stella, Rienna Russo, Victoria L. Mayer, Ming Wen, and Yan Li. 2023. Trends and disparities in diabetes and prediabetes among adults in the United States, 1999–2018. Public Health 214: 163–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, Alan C., and Stephen J. Schoenthaler. 2023. Nutrition, Behavior, and the Criminal Justice System: What Took so Long? An Interview with Dr. Stephen J. Schoenthaler. Challenges 14: 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loseman, Annemarie, and Kees van den Bos. 2012. A self-regulation hypothesis of coping with an unjust world: Ego-depletion and self-affirmation as underlying aspects of blaming of innocent victims. Social Justice Research 25: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumaga, Roberta Barone, Silvia Tagliamonte, Tiziana De Rosa, Vincenzo Valentino, Danilo Ercolini, and Paola Vitaglione. 2024. Consumption of a Sourdough-Leavened Croissant Enriched with a Blend of Fibers Influences Fasting Blood Glucose in a Randomized Controlled Trial in Healthy Subjects. The Journal of Nutrition 154: 2976–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manippa, Valerio, Raffaella Lupo, Luca Tommasi, and Afredo Brancucci. 2021. Italian breakfast in mind: The effect of caffeine, carbohydrate and protein on physiological state, mood and cognitive performance. Physiology & Behavior 234: 113371. [Google Scholar]

- Marchini, Francesco, Andrea Caputo, Alessio Convertino, Chiara Giuliani, Olimpia Bitterman, Dario Pitocco, Riccardo Fornengo, Elisabetta Lovati, Elisa Forte, Laura Sciacca, and et al. 2024. Associations between continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) metrics and psycholinguistic measures: A correlational study. Acta Diabetologica 61: 841–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, C. R., G. Panhuysen, A. Tuiten, H. Koppeschaar, D. Fekkes, and M. L. Peters. 1998. Does carbohydrate-rich, protein-poor food prevent a deterioration of mood and cognitive performance of stress-prone subjects when subjected to a stressful task? Appetite 31: 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, C. Rob, and Peter J. Rogers. 2020. Effects of high and low sucrose-containing beverages on blood glucose and hypoglycemic-like symptoms. Physiology & Behavior 222: 112916. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, Rob, Geert Panhuysen, Adriaan Tuiten, and Hans Koppeschaar. 2000. Effects of food on cortisol and mood in vulnerable subjects under controllable and uncontrollable stress. Physiology & Behavior 70: 333–42. [Google Scholar]

- Masicampo, Emer J., and Roy F. Baumeister. 2008. Toward a physiology of dual-process reasoning and judgment: Lemonade, willpower, and expensive rule-based analysis. Psychological Science 19: 255–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mawritz, Mary B., Rebecca L. Greenbaum, Marcus M. Butts, and Katrina A. Graham. 2017. I just can’t control myself: A self-regulation perspective on the abuse of deviant employees. Academy of Management Journal 60: 1482–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrimmon, Rory J., Fiona ME Ewing, Brian M. Frier, and Ian J. Deary. 1999. Anger state during acute insulin-induced hypoglycaemia. Physiology & Behavior 67: 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- McElroy, Todd, David L. Dickinson, and Irwin P. Levin. 2020. Thinking about decisions: An integrative approach of person and task factors. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 33: 538–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merbis, M. A. E., F. J. Snoek, K. Kanc, and R. J. Heine. 1996. Hypoglycaemia induces emotional disruption. Patient Education and Counseling 29: 117–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijakoski, Dragan, Jovanka Karadzinska-Bislimovska, Vera Basarovska, Anthony Montgomery, Efharis Panagopoulou, Sasho Stoleski, and Jordan Minov. 2015. Burnout, engagement, and organizational culture: Differences between physicians and nurses. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences 3: 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Monica K., Charles P. Edwards, Jenny Reichert, and Brian H. Bornstein. 2018a. An examination of outcomes predicted by the model of judicial stress. Judicature 102: 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Monica K., Jenny Reichert, Brian H. Bornstein, and Grant Shulman. 2018b. Judicial stress: The roles of gender and social support. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 25: 602–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misrani, Afzal, Sidra Tabassum, Zai-yong Zhang, Shao-hua Tan, and Cheng Long. 2024. Urolithin A prevents sleep-deprivation-induced neuroinflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction in young and aged mice. Molecular Neurobiology 61: 1448–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Gregory. 2010. Evaluating judges. In The Psychology of Judicial Decision Making. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 249–68. [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni, Houra, Fatemeh Malek Mohammadi, Zahra Karampour, Shirin Amini, Behnaz Abiri, and Mehdi Sayyah. 2021. The relationship between history of dietary nutrients intakes and incidence of aggressive behavior in adolescent girls: A case-control study. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN 43: 200–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrug, Sylvie, LaRita C. Jones, Marc N. Elliott, Susan R. Tortolero, Melissa F. Peskin, and Mark A. Schuster. 2021. Soft Drink Consumption and Mental Health in Adolescents: A Longitudinal Examination. Journal of Adolescent Health 68: 155–60. [Google Scholar]

- Muth, Anne-Katrin, and Soyoung Q. Park. 2021. The impact of dietary macronutrient intake on cognitive function and the brain. Clinical Nutrition 40: 3999–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordali, Erica, Pablo Marcos-Prieto, Giulia Avvenuti, Emiliano Ricciardi, Leonardo Boncinelli, Pietro Pietrini, Giulio Bernardi, and Ennio Bilancini. 2024. Prolonged exertion of self-control causes increased sleep-like frontal brain activity and changes in aggressivity and punishment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121: e2404213121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmnäs-Bédard, Marie SA, Giuseppina Costabile, Claudia Vetrani, Sebastian Åberg, Yommine Hjalmarsson, Johan Dicksved, Gabriele Riccardi, and Rikard Landberg. 2022. The human gut microbiota and glucose metabolism: A scoping review of key bacteria and the potential role of SCFAs. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 116: 862–74. [Google Scholar]

- Penttinen, Markus A., Jenni Virtanen, Marika Laaksonen, Maijaliisa Erkkola, Henna Vepsäläinen, Hannu Kautiainen, and Päivi Korhonen. 2021. The association between healthy diet and burnout symptoms among Finnish municipal employees. Nutrients 13: 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, Emil, Kinga Barrafrem, Andreas Meunier, and Gustav Tinghög. 2019. The effect of decision fatigue on surgeons’ clinical decision making. Health Economics 28: 1194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Linda. 1978. Brain Neurophysiology in Persons with Reactive Hypoglycemia. Ph.D. dissertation, The Union for Experimenting Colleges and Universities. Union Graduate School West, San Francisco, CA, USA. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/d02b17684fbcf3a6756e4a465035f430/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Peterson, Linda. 2023. It’s All in Your Head. Available online: https://hypoglycemia.org/all-in-your-head/ (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Pfeiler, Tamara M., and Boris Egloff. 2018. Personality and attitudinal correlates of meat consumption: Results of two representative German samples. Appetite 121: 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiler, Tamara M., and Boris Egloff. 2020. Personality and eating habits revisited: Associations between the big five, food choices, and Body Mass Index in a representative Australian sample. Appetite 149: 104607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfundmair, Michaela, C. Nathan DeWall, Veronika Fries, Babette Geiger, Tanya Krämer, Sebastian Krug, Dieter Frey, and Nilüfer Aydin. 2015. Sugar or spice: Using I3 metatheory to understand how and why glucose reduces rejection-related aggression. Aggressive Behavior 41: 537–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratas, Matilde Maia, João Paulo Dias, Gustavo Ferreira da Veiga, and Luciana Sotero. 2025. Burnout and other psychosocial factors in Portuguese judges: The influence of sociodemographic and work variables. International Journal on Working Conditions 28: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Prater, Erin. 2023. Nearly half of the U.S. population has diabetes or prediabetes—and many have no clue. Are you among them? Fortune. December 23. Available online: https://fortune.com/well/article/diabetes-prediabetes-obesity-half-united-states-population-insulin-wegovy-type1-type2-signs-symptoms/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Prescott, Susan L., and Alan C. Logan. 2017. Each meal matters in the exposome: Biological and community considerations in fast-food-socioeconomic associations. Economics and Human Biology 27, (Pt B): 328–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priel, Dan. 2020. Law is what the judge had for breakfast: A brief history of an unpalatable idea. Buff. L. Rev. 68: 899. [Google Scholar]

- Pyle, Benjamin, and Clifford Rosky. 2025. Measuring Lawyer Mental Illness: Evidence from Two National Surveys. SSRN. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5242114 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Ramey, Sandra L., Madeleine M. Liotta, Ji Eun Park, Meghan S. O’Leary, and Elizabeth A. Mumford. 2024. Exploring the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 as a screening tool for wellness in law enforcement. Police Practice and Research 25: 150–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rania, Marianna, Mariarita Caroleo, Elvira Anna Carbone, Marco Ricchio, Maria Chiara Pelle, Isabella Zaffina, Francesca Condoleo, Renato de Filippis, Matteo Aloi, Pasquale De Fazio, and et al. 2023. Reactive hypoglycemia in binge eating disorder, food addiction, and the comorbid phenotype: Unravelling the metabolic drive to disordered eating behaviours. Journal of Eating Disorders 11: 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, Alexis, Karen A. Myatt, and Priscilla V. Marotta. 2011. Surviving bench stress. Family Court Review 49: 610–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Jake M., Nicole Redvers, Araceli Camargo, Christina A. Bosch, Martin F. Breed, Lisa A. Brenner, Megan A. Carney, Ashvini Chauhan, Mauna Dasari, Leslie G. Dietz, and et al. 2022. Twenty Important Research Questions in Microbial Exposure and Social Equity. mSystems 7: e0124021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, Christopher C., Joel Koopman, Allison S. Gabriel, and Russell E. Johnson. 2016. Who strikes back? A daily investigation of when and why incivility begets incivility. Journal of Applied Psychology 101: 1620–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuthpongtorn, Chatpol, Long H. Nguyen, Olivia I. Okereke, Dong D. Wang, Mingyang Song, Andrew T. Chan, and Raaj S. Mehta. 2023. Consumption of Ultraprocessed Food and Risk of Depression. JAMA Network Open 6: e2334770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Aguadero, Natalia, Jose I. Recio-Rodriguez, Maria C. Patino-Alonso, Sara Mora-Simon, Rosario Alonso-Dominguez, Benigna Sanchez-Salgado, Manuel A. Gomez-Marcos, and Luis Garcia-Ortiz. 2020. Postprandial effects of breakfast glycaemic index on cognitive performance among young, healthy adults: A crossover clinical trial. Nutritional Neuroscience 23: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarris, Jerome, Alan C. Logan, Tasnime N. Akbaraly, G. Paul Amminger, Vicent Balanzá-Martínez, Marlene P. Freeman, Joseph Hibbeln, Yutaka Matsuoka, Dadvid Mischoulon, Tetsuya Mizoue, and et al. 2015. Nutritional medicine as mainstream in psychiatry. Lancet Psychiatry 2: 271–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarr, Lew. 1972. Dr. Salk: Book deals with man’s relation, not medicine. Courier-Post, November 15, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Schrever, Carly. 2024. The human dimension of judging: A summary of a recent interview study of Australian judicial officers. Judicial Officers Bulletin 36: 111–16. [Google Scholar]

- Schrever, Carly, Carol Hulbert, and Tania Sourdin. 2019. The psychological impact of judicial work: Australia’s first empirical research measuring judicial stress and wellbeing. Journal of Judicial Administration 28: 141–68. [Google Scholar]

- Schrever, Carly, Carol Hulbert, and Tania Sourdin. 2024. The privilege and the pressure: Judges’ and magistrates’ reflections on the sources and impacts of stress in judicial work. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 31: 327–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoubridge, Andrew P., Jocelyn M. Choo, Alyce M. Martin, Damien J. Keating, Ma-Li Wong, Julio Licinio, and Geraint B. Rogers. 2022. The gut microbiome and mental health: Advances in research and emerging priorities. Molecular Psychiatry 27: 1908–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showalter, C. Robert, and Daniel A. Martell. 1985. Personality, stress and health in American judges. Judicature 69: 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Skead, Natalie K., Shane L. Rogers, and Jerome Doraisamy. 2018. Looking beyond the mirror: Psychological distress; disordered eating, weight and shape concerns; and maladaptive eating habits in lawyers and law students. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 61: 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommerfield, Andrew J., Ian J. Deary, and Brian M. Frier. 2004. Acute hyperglycemia alters mood state and impairs cognitive performance in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 27: 2335–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, Catherine C., Jesseca RA Pirkle, and Kimberly Kirkpatrick. 2017. Diet-induced impulsivity: Effects of a high-fat and a high-sugar diet on impulsive choice in rats. PLoS ONE 12: e0180510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, Sabrina, Christina Hoeber, Olaf Uhl, Berthold Koletzko, Thomas F. Münte, Hendrik Lehnert, Raymond J. Dolan, Sebastian M. Schmid, and Soyoung Q. Park. 2017. Impact of nutrition on social decision making. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114: 6510–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, Taiki, Haruhiko Tokuda, Hisayuki Miura, Shuji Kawashima, Takafumi Ando, Yujiro Kuroda, Nanae Matsumoto, Kosuke Fujita, Kazuaki Uchida, Yoshinobu Kishino, and et al. 2023. Cross-sectional association of metrics derived from continuous glucose monitoring with cognitive performance in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 25: 222–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Mengtong, Qida He, Guoxian Li, Hanqing Zhao, Yu Wang, Ze Ma, Zhaolong Feng, Tongxing Li, Jiadong Chu, Wei Hu, and et al. 2023. Association of Ultra-processed Food Consumption with Incident Depression and Anxiety: A Population-based Cohort Study. Food and Function, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Swami, Viren, Samantha Hochstöger, Erik Kargl, and Stefan Stieger. 2022. Hangry in the field: An experience sampling study on the impact of hunger on anger, irritability, and affect. PLoS ONE 17: e0269629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swenson, David, Joan Bibelhausen, Bree Buchanan, David Shaheed, and Katheryn Yetter. 2020. Stress and resiliency in the US Judiciary. Journal of the Professional Lawyer 2020: 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tampubolon, Manotar, Tomson Situmeang, and Paltiada Saragih. 2023. Judicial breakfast as an external factor in judicial decision making in courts. F1000Research 12: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, Kevin, Jasmeet Singh, Asta Medisauskaite, and Juliet Hassard. 2022. Doctors’ perceived working conditions, psychological health, and patient care: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 80: 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Cheryl. 2024. 2024 UK Judicial Attitude Survey Northern Ireland Judiciary. University College London, Judicial Institute. Available online: https://www.judiciaryni.uk/publications/2024-judicial-attitude-survey-findings-report (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Torres, Luis C., and Joshua H. Williams. 2022. Tired Judges? An Examination of the Effect of Decision Fatigue in Bail Proceedings. Criminal Justice and Behavior 49: 1233–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Feng-Jen, and Chang-Chuan Chan. 2010. Occupational stress and burnout of judges and procurators. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 83: 133–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl, Andrzej, and Justin Pickett. 2025. Noise in Judicial Decision-Making: A Research Note. CrimRxiv. Available online: https://www.crimrxiv.com/pub/88emhqng/release/1 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Utter, Jennifer, Sally McCray, and Simon Denny. 2023. Eating behaviours among healthcare workers and their relationships with work-related burnout. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 15598276231159064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veser, Petra, Kathy Taylor, and Susanne Singer. 2015. Diet, authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, and predisposition to prejudice: Results of a German survey. British Food Journal 117: 1949–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virkkunen, Matti. 1986. Insulin secretion during the glucose tolerance test among habitually violent and impulsive offenders. Aggressive Behavior 12: 303–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virkkunen, Matti, and Matti Huttunen. 1982. Evidence for abnormal glucose tolerance test among violent offenders. Neuropsychobiology 8: 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiao-Tian, and Gang Huangfu. 2017. Glucose-specific signaling effects on delay discounting in intertemporal choice. Physiology & Behavior 169: 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xiao-Tian, and Robert D. Dvorak. 2010. Sweet future: Fluctuating blood glucose levels affect future discounting. Psychological Science 21: 183–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werneck, André O., Davy Vancampfort, Adewale L. Oyeyemi, Brendon Stubbs, and Danilo R. Silva. 2020. Joint association of ultra-processed food and sedentary behavior with anxiety-induced sleep disturbance among Brazilian adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders 266: 135–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcox, Matthew D., Guy S. Taylor, Peter I. Chater, Kyle J. Stanforth, Maria I. Zakhour, Rebecca Williams, James Collier, and Jeffrey P. Pearson. 2024. The Effects of a Breakfast Meal of a Proprietary, Powdered, Plant-Based Food or a Standard Breakfast on Appetite. SSRN. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5013527 (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Wilder, Joseph. 1940. Problems of criminal psychology related to hypoglycemic states. Journal of Criminology and Psychopathology 1: 219. [Google Scholar]

- Wilder, Joseph. 1943. Psychological problems in hypoglycemia. The American Journal of Digestive Diseases 10: 428–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder, Joseph. 1947. Sugar metabolism and its relation to criminology. In Handbook of Correctional Psychology. Edited by R. M. Lindner and R. V. Seliger. New York: Philosophical Library, pp. 98–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, Michael D., Desta Fekedulegn, Michael E. Andrew, Alexander C. McLain, James B. Burch, Jean E. Davis, James R. Hébert, and John M. Violanti. 2022. Longitudinal and cross-sectional associations between the dietary inflammatory index and objectively and subjectively measured sleep among police officers. Journal of Sleep Research 31: e13543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, Michael D., James Burch, Nitin Shivappa, John M. Violanti, Cecil M. Burchfiel, Desta Fekedulegn, Michael E. Andrew, Tara A. Hartley, Diane B. Miller, Anna Mnatsakanova, and et al. 2014. Association of a dietary inflammatory index with inflammatory indices and metabolic syndrome among police officers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 56: 986–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Wen-Chi, Ching-I. Lin, Yi-Fan Li, Ling-Yin Chang, and Tung-liang Chiang. 2020. The mediating effect of dietary patterns on the association between mother’s education level and the physical aggression of five-year-old children: A population-based cohort study. BMC Pediatrics 20: 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyshak, Grace, and Robert S. Lawrence. 1983. Health-promoting behavior among lawyers and judges. Journal of Community Health 8: 174–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Hanyi, Laurent Bègue, Laure Sauve, and Brad J. Bushman. 2014. Sweetened blood sweetens behavior. Ego depletion, glucose, guilt, and prosocial behavior. Appetite 81: 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Jie, Zupeng Yan, and Qingjun Liu. 2022. Smartphone-based electrochemical systems for glucose monitoring in biofluids: A review. Sensors 22: 5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Sumiko, Emiko Aizawa, Naoko Ishihara, Kotaro Hattori, Kazuhiko Segawa, and Hiroshi Kunugi. 2025. High Rates of Abnormal Glucose Metabolism Detected by 75 g Oral Glucose Tolerance Test in Major Psychiatric Patients with Normal HbA1c and Fasting Glucose Levels. Nutrients 17: 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahedi, Hoda, Roya Kelishadi, Ramin Heshmat, Mohammad Esmaeil Motlagh, Shirin Hasani Ranjbar, Gelayol Ardalan, Moloud Payab, Mohammad Chinian, Hamid Asayesh, Bagher Larijani, and et al. 2014. Association between junk food consumption and mental health in a national sample of Iranian children and adolescents: The CASPIAN-IV study. Nutrition 30: 1391–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Xiaobei, Soumya Ravichandran, Gilbert C. Gee, Tien S. Dong, Hiram Beltrán-Sánchez, May C. Wang, Lisa A. Kilpatrick, Jennifer S. Labus, Allison Vaughan, and Arpana Gupta. 2024. Social Isolation, Brain Food Cue Processing, Eating Behaviors, and Mental Health Symptoms. JAMA Network Open 7: e244855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Yanru, Zhuoran Li, Shan Jin, and Xiaomeng Zhang. 2024. The Impact of Cognitive Load on Cooperation and Antisocial Punishment: Insights from a Public Goods Game Experiment. Behavioral Sciences 14: 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Liwen, Jing Sun, Xiaohui Yu, and Dongfeng Zhang. 2020. Ultra-Processed Food Is Positively Associated With Depressive Symptoms Among United States Adults. Frontiers in Nutrition 7: 600449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Xiaojia, Jiamei Song, Xindi Shi, Chunmei Kan, and Chaoran Chen. 2024. The effect of authoritarian leadership on young nurses’ burnout: The mediating role of organizational climate and psychological capital. BMC Health Services Research 25: 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Logan, A.C.; Berryessa, C.M.; Mishra, P.; Prescott, S.L. On Gastronomic Jurisprudence and Judicial Wellness as a Matter of Competence. Laws 2025, 14, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14030039

Logan AC, Berryessa CM, Mishra P, Prescott SL. On Gastronomic Jurisprudence and Judicial Wellness as a Matter of Competence. Laws. 2025; 14(3):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14030039

Chicago/Turabian StyleLogan, Alan C., Colleen M. Berryessa, Pragya Mishra, and Susan L. Prescott. 2025. "On Gastronomic Jurisprudence and Judicial Wellness as a Matter of Competence" Laws 14, no. 3: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14030039

APA StyleLogan, A. C., Berryessa, C. M., Mishra, P., & Prescott, S. L. (2025). On Gastronomic Jurisprudence and Judicial Wellness as a Matter of Competence. Laws, 14(3), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14030039