Microstructure and Dry-Sliding Wear Behavior of B4C Ceramic Particulate Reinforced Al 5083 Matrix Composite

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Material

2.2. Metallographic Experiment

2.3. Wear Test

3. Results and Discussion

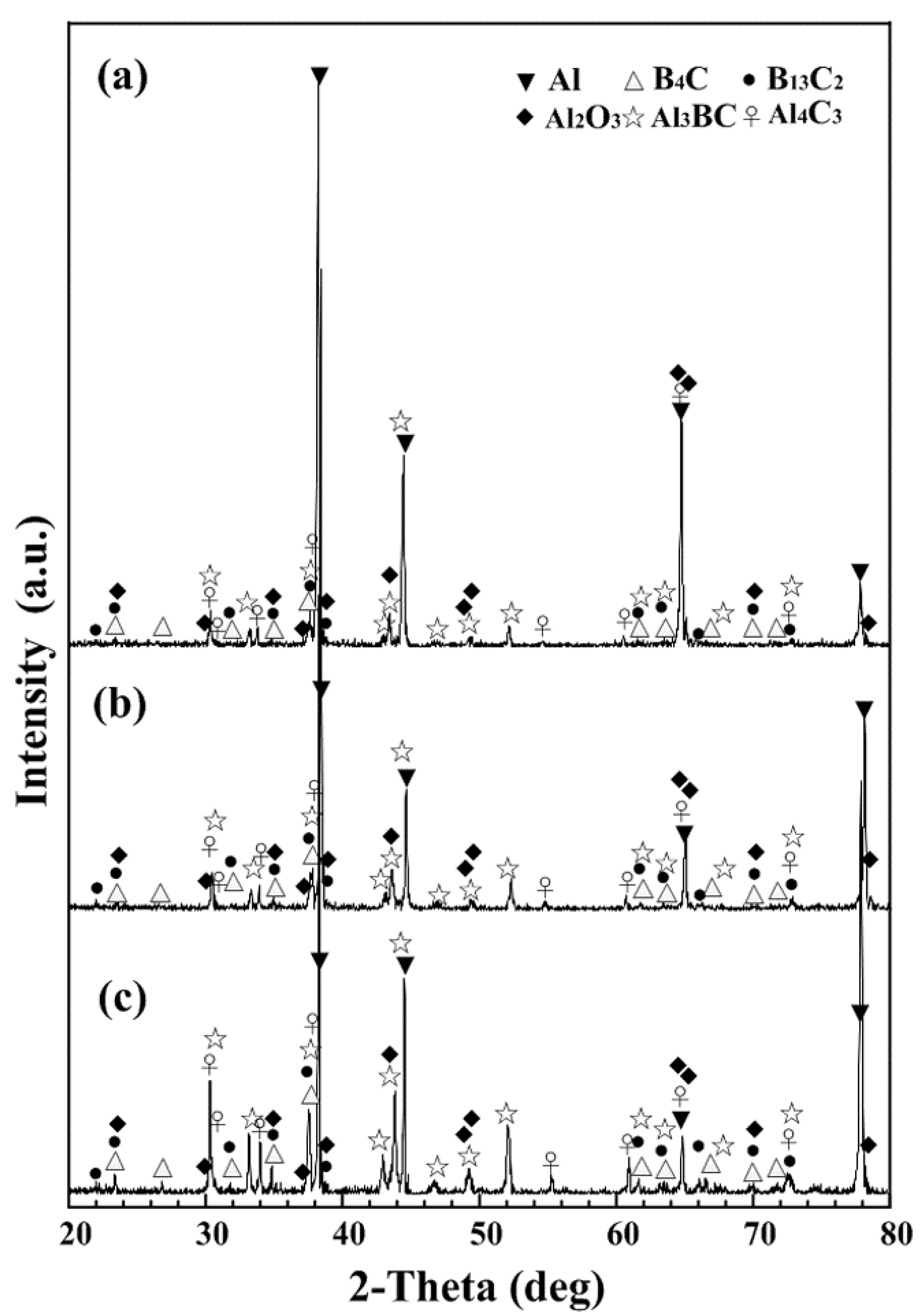

3.1. Microstructure and Phase Composition of B4C/Al 5083 Composite

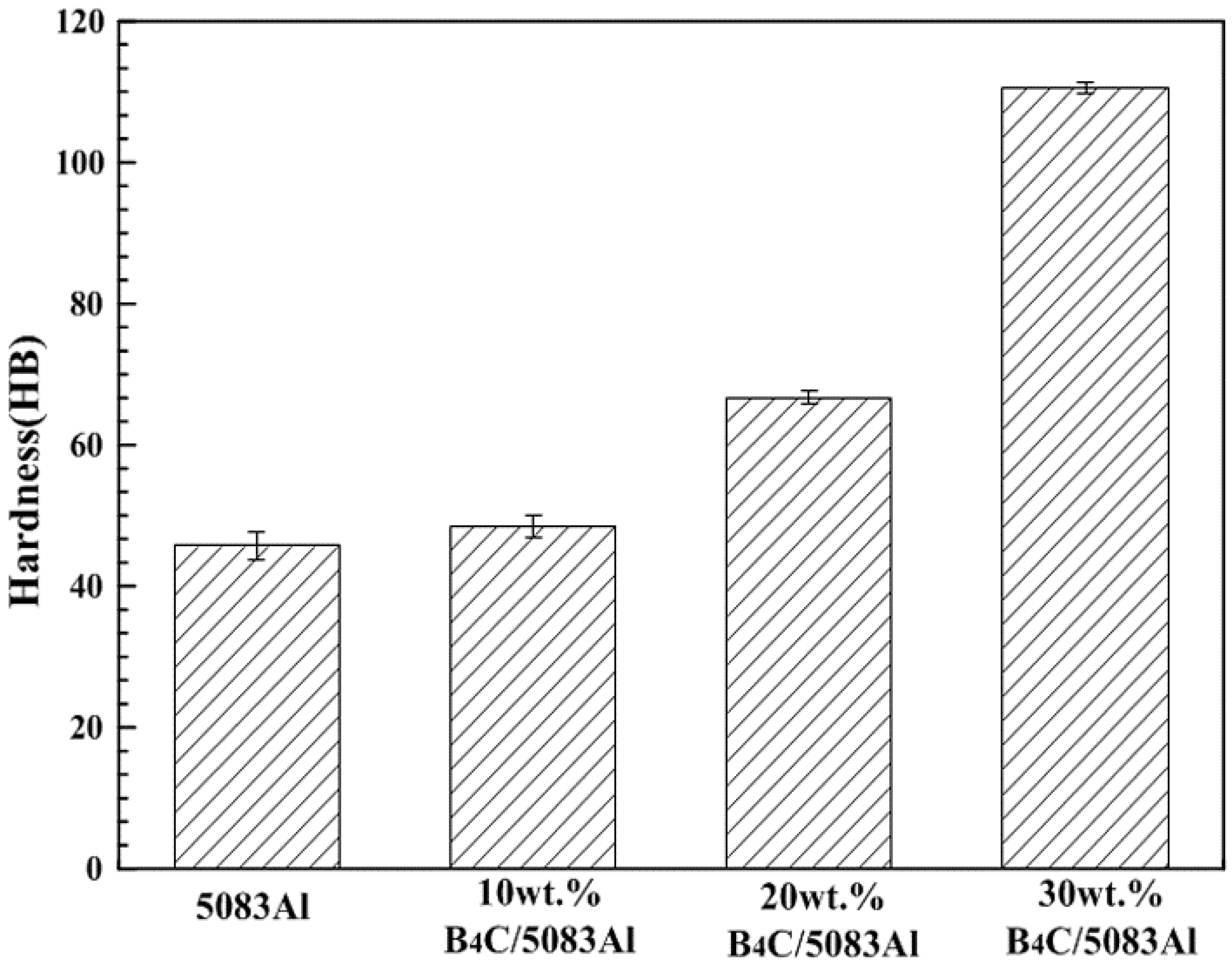

3.2. Hardness

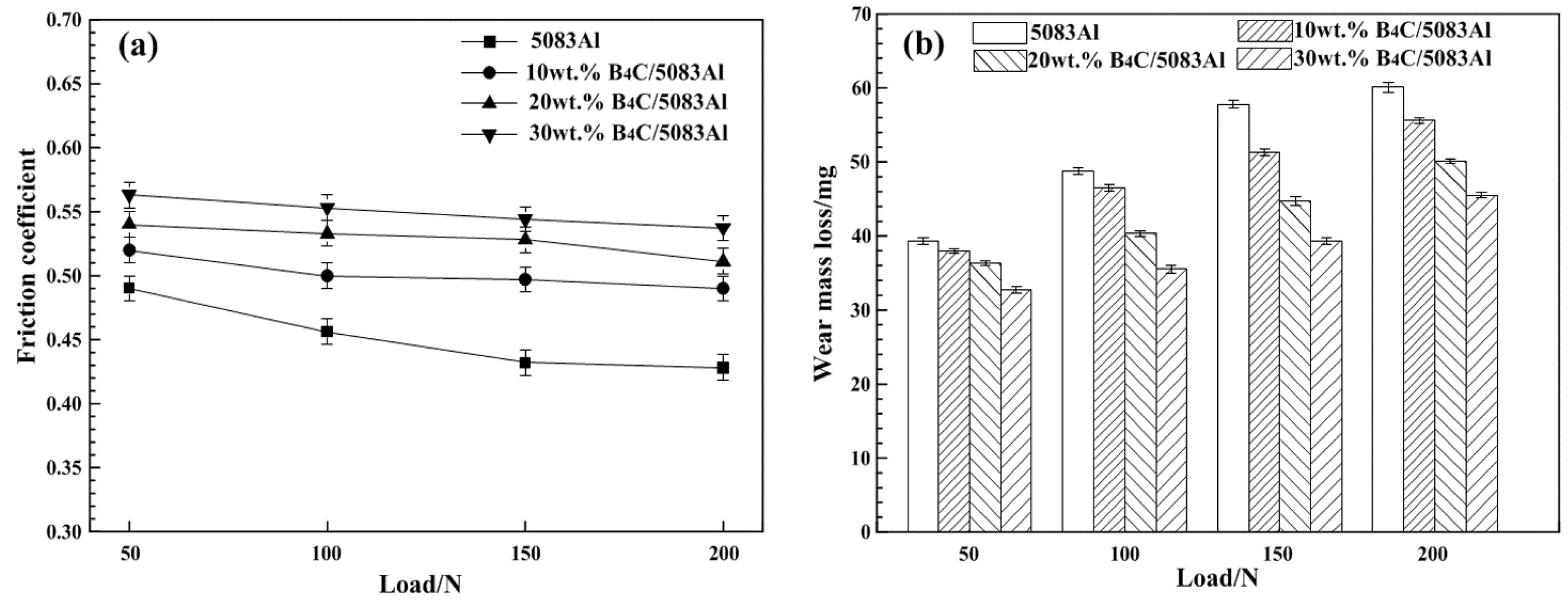

3.3. Wear Behavior

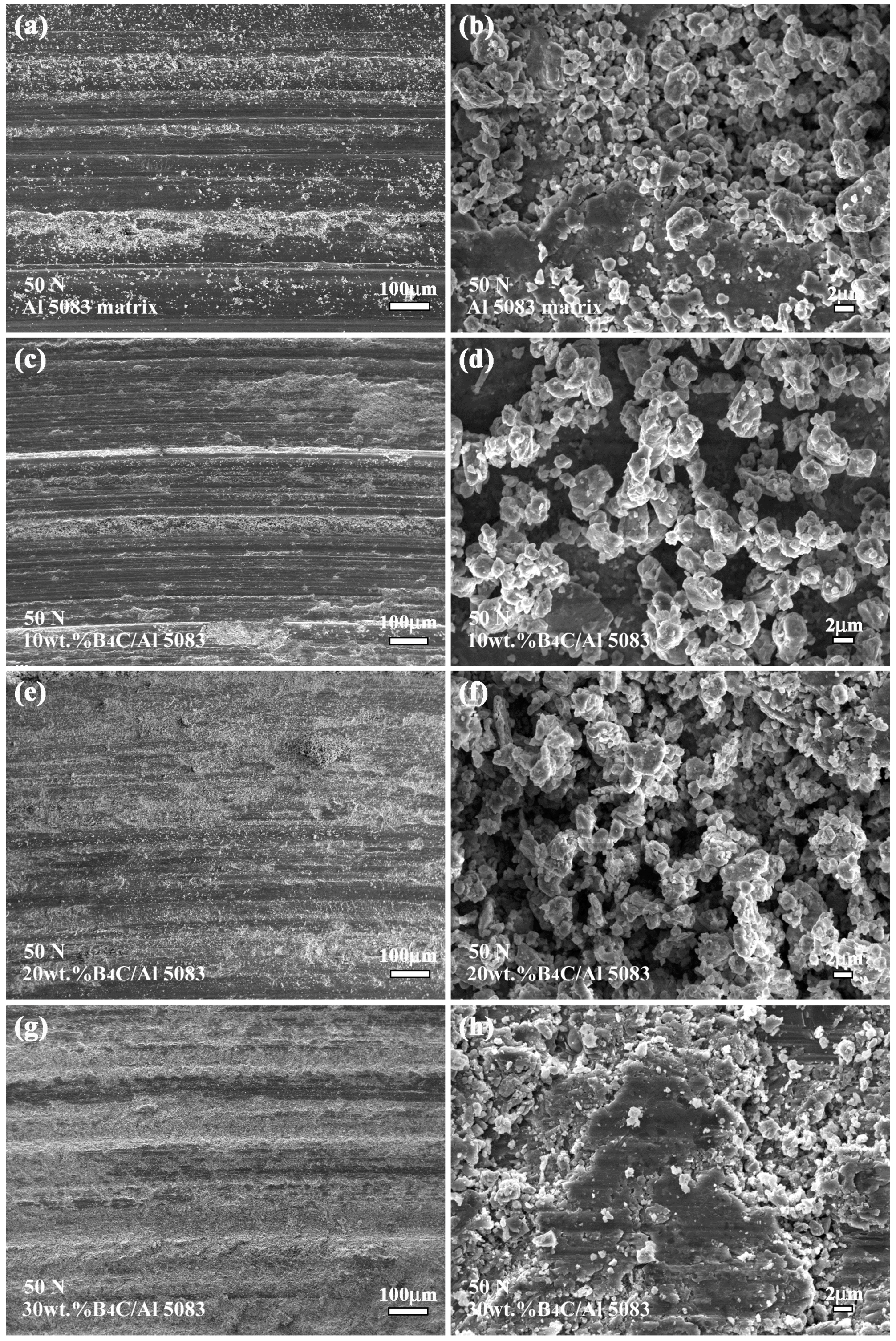

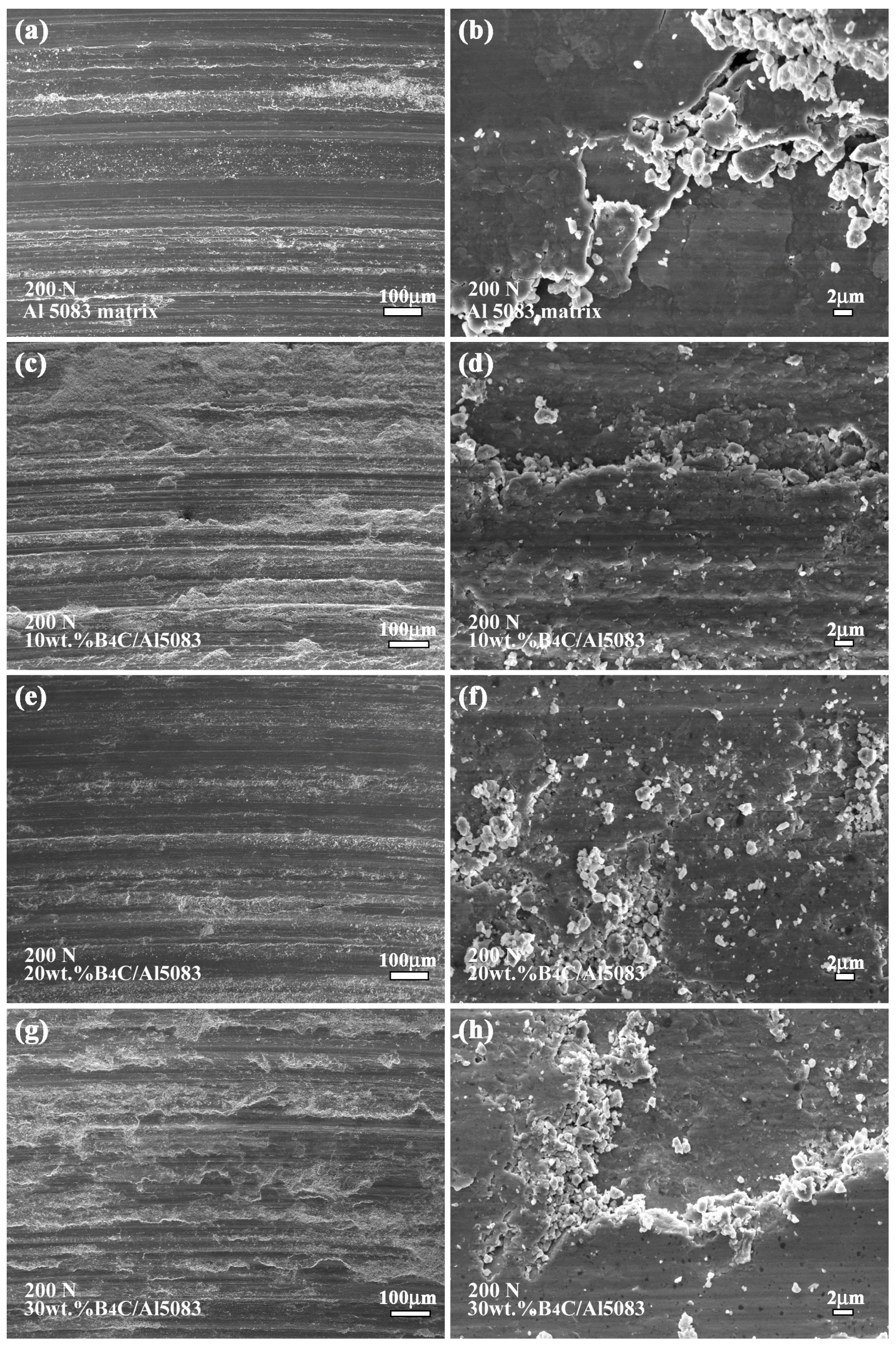

3.4. Wear Surface

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- A B4C/Al 5083 composite with a relatively higher density was fabricated successfully. B4C particles presented a relatively homogeneous distribution in the Al 5083 matrix. No severe particle segregation phenomenon existed in the composite.

- (2)

- The B13C2, Al3BC and Al4C3 phases were detected from XRD patterns, suggesting B4C particles have reacted with the Al5083 matrix, which enhanced the wettability of the B4C in the matrix.

- (3)

- The hardness values, friction coefficient and wear resistance of the B4C/Al 5083 composites were higher than those of the Al 5083 matrix. The 30 wt % B4C/Al 5083 composite exhibited the highest wear resistance and friction coefficient.

- (4)

- At a low applied load of 50 N, the dominant wear mechanisms of the B4C/Al 5083 composites were micro-cutting and abrasive wear. At a high load of 200 N, the dominant wear mechanisms were micro-cutting and adhesion wear. The adhesion wear was associated with the formation of a delamination layer, which protected the composite from further wear and enhanced the wear resistance.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Toptan, F.; Kilicarslan, A.; Kertil, I. The effect of Ti addition on the properties of Al-B4C interface: A microstructural study. Mater. Sci. Forum 2010, 636, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Mai, Y. Wear behavior of SiCp/Al-Si composites. Wear 1994, 176, 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, A.; Abdollahi, L.; Biukani, H. Creep behavior and wear resistance of Al 5083 based hybrid composites reinforced with carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and boron carbide (B4C). J. Alloy. Compd. 2015, 650, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baradeswaran, A.; Perumal, A.E. Influence of B4C on the tribological and mechanical properties of Al 7075-B4C composites. Compos. B-Eng. 2013, 54, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizenshtein, M.; Froumin, N.; Shapiro, T.E.; Dariel, M.P.; Frage, N. Wetting and interface phenomena in the B4C/(Cu-B-Si) system. Scr. Mater. 2005, 53, 1231–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Kang, S. Advances in manufacturing boron carbide-aluminum composites. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2004, 87, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Dong, H.; Lu, K. Coating different thickness nickel-boron nanolayers onto boroncarbide particles. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008, 202, 2927–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N.K.; Kawai, M.; Saji, T. Co-deposition of B4C particles and nickel under the influence of a redox-active surfactant and anti-wear property of the coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2005, 200, 2414–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.C. Advanced materials and powders. Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 2001, 80, 64–66. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Q.; Wu, C.D.; Luo, G.Q.; Fang, P.; Li, C.Z.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhang, L.M. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-7075/B4C composites fabricated by plasma activated sintering. J. Alloy. Compd. 2014, 588, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.D.; Fang, P.; Luo, G.Q.; Chen, F.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, L.M.; Lavernia, E.J. Effect of plasma activated sintering parameters on microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-7075/B4C composites. J. Alloy. Compd. 2014, 615, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipek, R. Adhesive wear behaviour of B4C and SiC reinforced 4147 Al matrix composites (Al/B4C-Al/SiC). J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2005, 162, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.B.; Xiong, Z.P.; Xia, Q.B. Friction and wear behaviors of B4C/6061Al composite. Mater. Des. 2014, 60, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.W.; Zhao, Y.G.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.G.; Jiang, Q.C. Fabrication of in situ TiC locally reinforced manganese steel matrix composite via combustion synthesis during casting. Mater. Des. 2013, 44, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.S.; Wu, G.H.; Jiang, L.T.; Li, R.F.; Xu, Z.G. Analysis of morphology and microstructure of B4C/2024Al composites after 7.62 mm ballistic impact. Mater. Des. 2014, 63, 658–663. [Google Scholar]

- Sarikaya, O.; Anik, S.; Aslanlar, S.; Okumus, S.C.; Celik, E. Al-Si/B4C composite coatings on Al-Si substrate by plasma spray technique. Mater. Des. 2007, 28, 2443–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Lu, J. Applications and the properties of boron carbide ceramic material. J. Wuyi Univ. 2002, 3, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, P.C.; Cao, Z.W.; Wu, G.H.; Zhang, J.H.; Wei, D.J.; Lin, L.T. Phase identification of Al-B4C ceramic composites synthesized by reaction hot-press sintering. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2010, 28, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G.; Kara, F.; Turan, S. Quantitative X-ray diffraction analysis of reactive infiltrated boron carbide-aluminium composites. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2003, 23, 1243–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halverson, D.C.; Pyzik, A.J.; Aksay, I.A.; Snowden, W.E. Processing of boron carbide-aluminum composites. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1989, 72, 775–780. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Q.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Ren, L. Microstructure and Dry-Sliding Wear Behavior of B4C Ceramic Particulate Reinforced Al 5083 Matrix Composite. Metals 2016, 6, 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/met6090227

Zhao Q, Liang Y, Zhang Z, Li X, Ren L. Microstructure and Dry-Sliding Wear Behavior of B4C Ceramic Particulate Reinforced Al 5083 Matrix Composite. Metals. 2016; 6(9):227. https://doi.org/10.3390/met6090227

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Qian, Yunhong Liang, Zhihui Zhang, Xiujuan Li, and Luquan Ren. 2016. "Microstructure and Dry-Sliding Wear Behavior of B4C Ceramic Particulate Reinforced Al 5083 Matrix Composite" Metals 6, no. 9: 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/met6090227

APA StyleZhao, Q., Liang, Y., Zhang, Z., Li, X., & Ren, L. (2016). Microstructure and Dry-Sliding Wear Behavior of B4C Ceramic Particulate Reinforced Al 5083 Matrix Composite. Metals, 6(9), 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/met6090227