Development of Technology for Processing Pyrite–Cobalt Concentrates to Obtain Pigments of the Composition Fe2O3 and Fe3O4

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

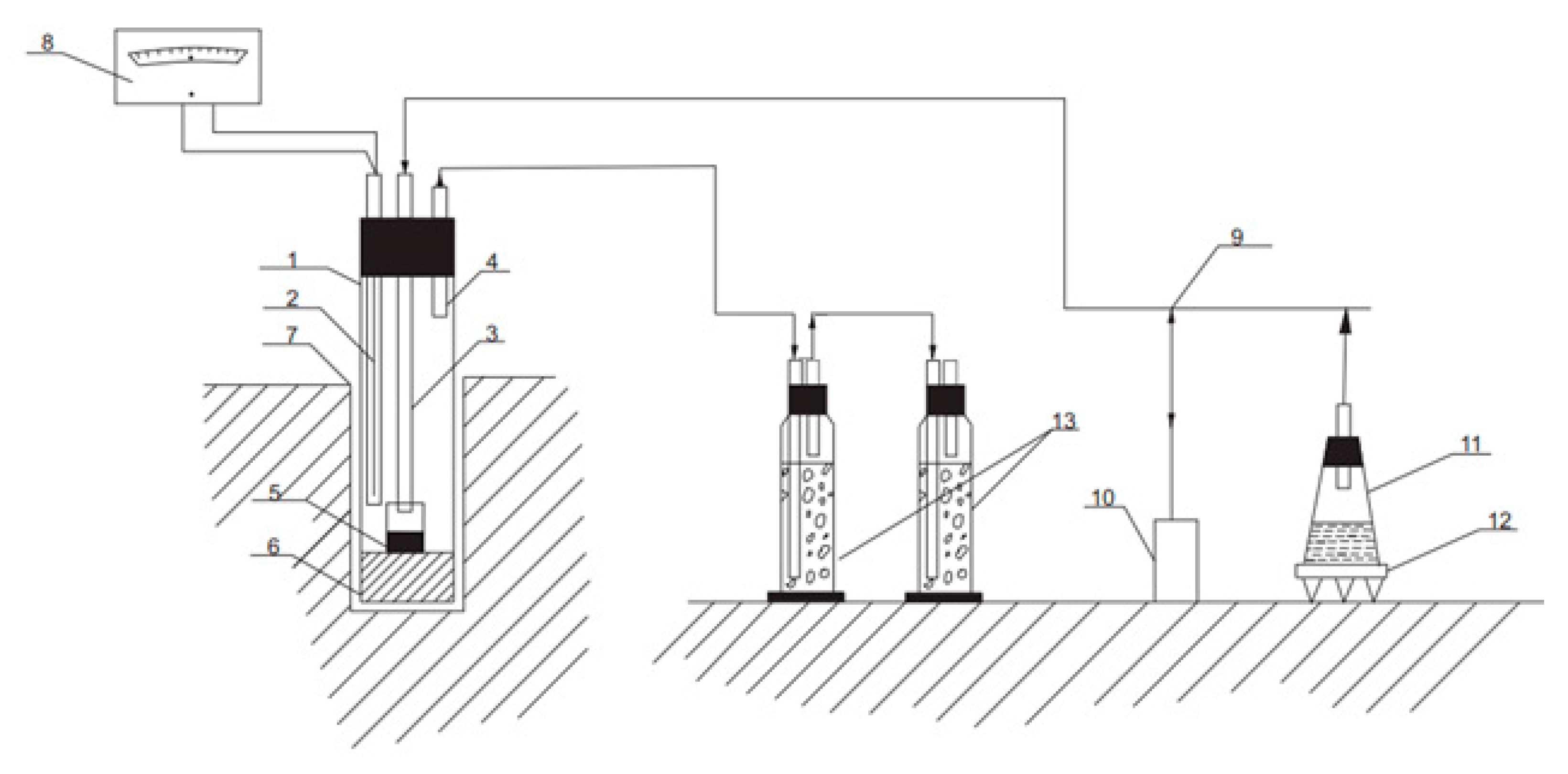

2.1. Experimental Procedure for the Chloride Volatilization Process

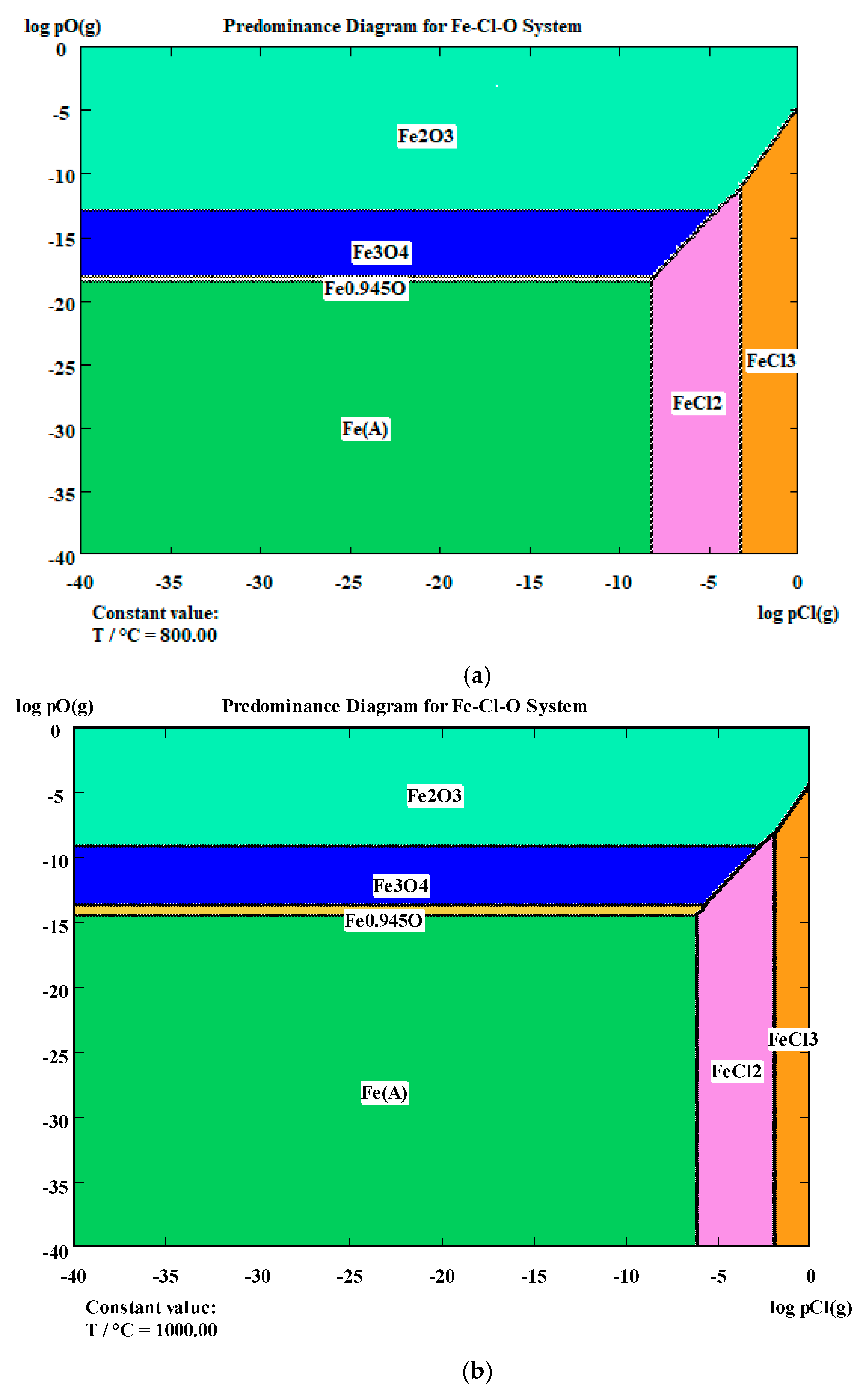

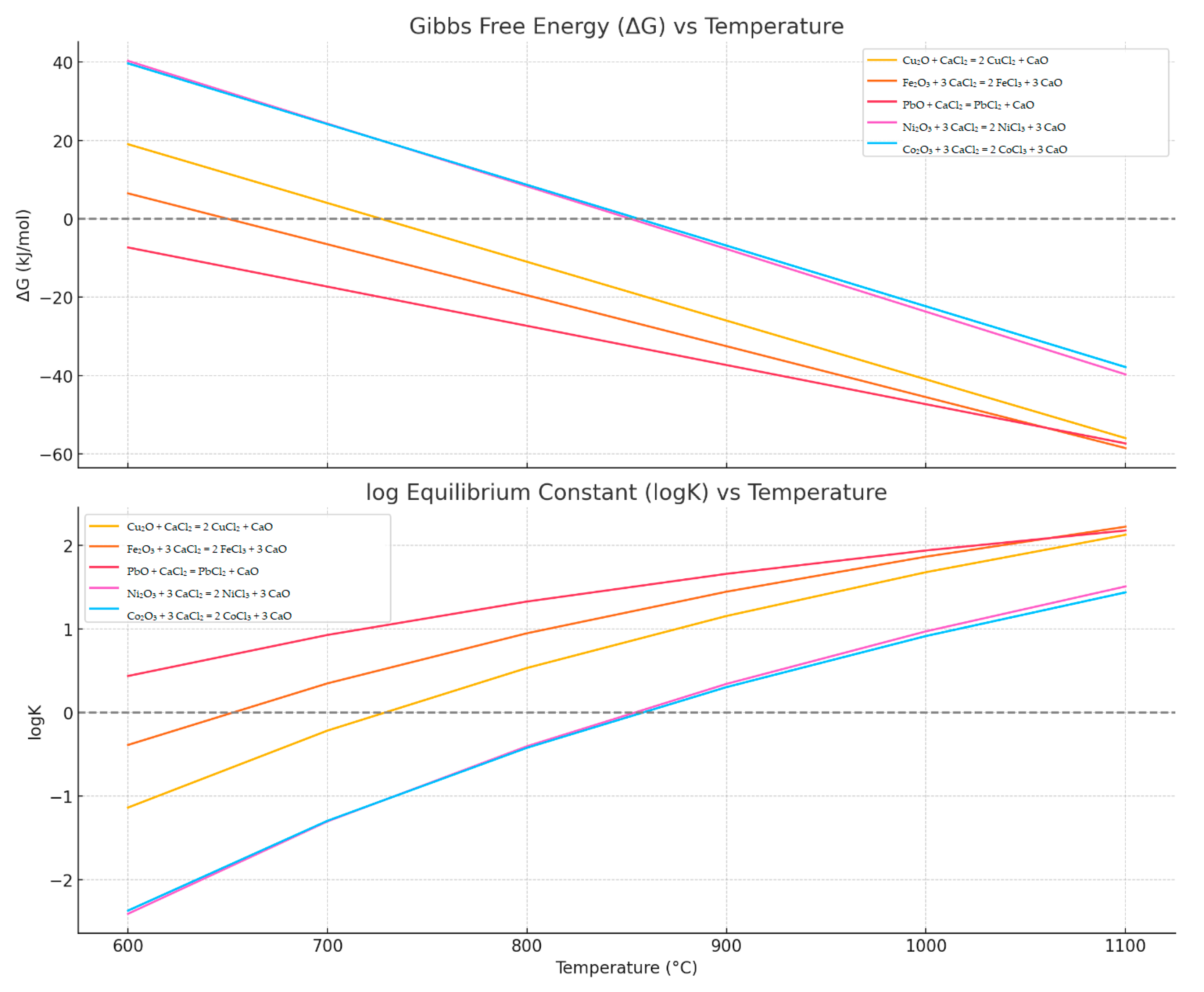

2.2. Thermodynamic Analysis of the Chloride Volatilization Process

- PbO + CaCl2 → PbCl2 + CaO—the earliest onset, with T_eq around 527 °C;

- Cu2O and Fe2O3—mid-range equilibrium temperatures, approximately 650–730 °C;

- Ni2O3 and Co2O3—require higher chlorination temperatures, above 850 °C.

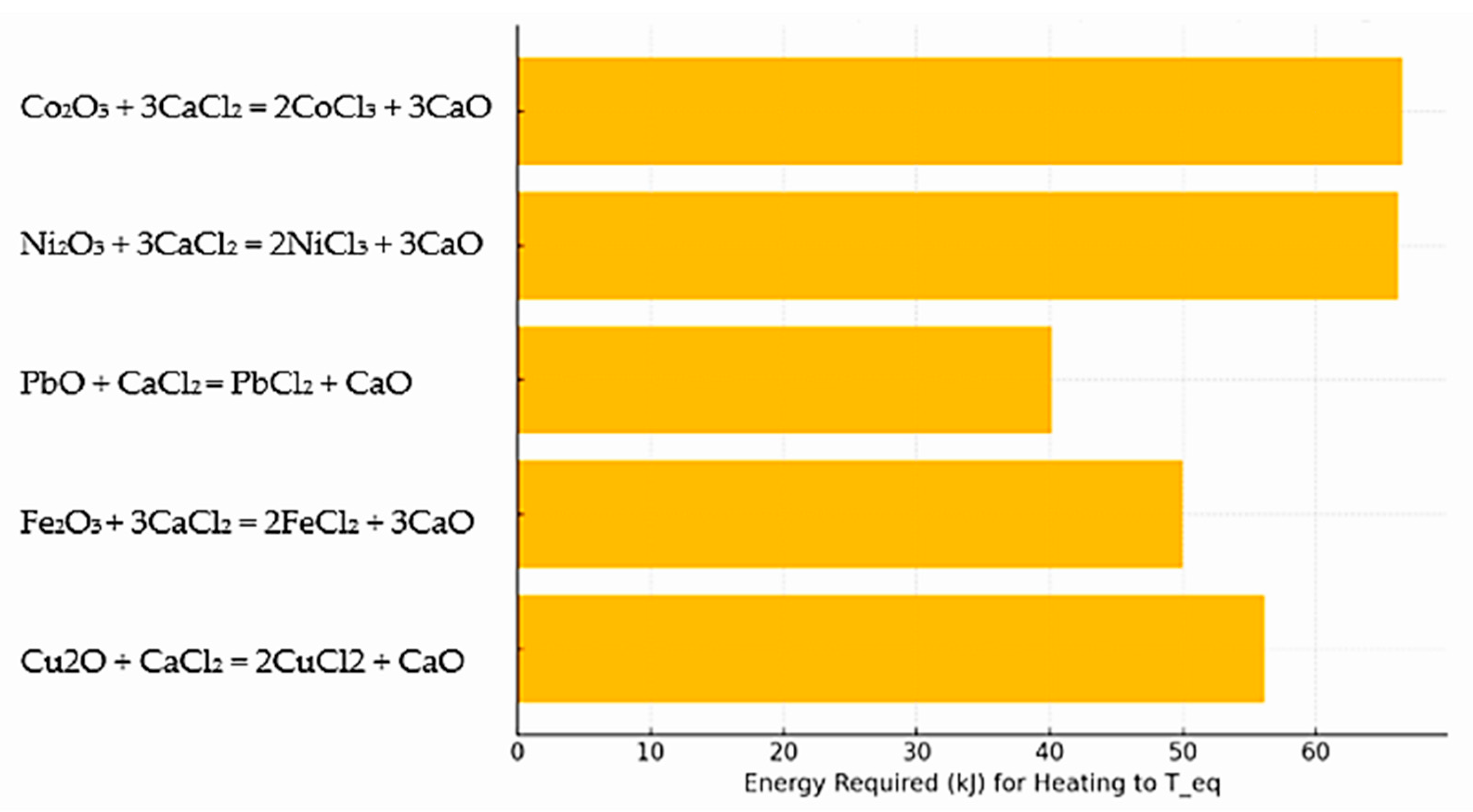

- Lead volatilization requires only approximately 40 kJ.

- Copper and iron require around 50–60 kJ.

- Nickel and cobalt require more than 65–70 kJ, indicating their higher energy demand for volatilization.

- Lead volatilization requires only ~40 kJ;

- Copper and iron require approximately 50–60 kJ;

- Nickel and cobalt require more than 65–70 kJ, highlighting their greater energy demand for volatilization.

- Initial stage (600–800 °C): efficient removal of Pb, Cu, and Fe;

- Elevated temperatures (900–1100 °C): required for volatilizing Ni and Co;

- This enables stepwise selective chloride volatilization, beginning with Pb, followed by Fe/Cu, and finally Ni/Co.

3. Results and Discussion

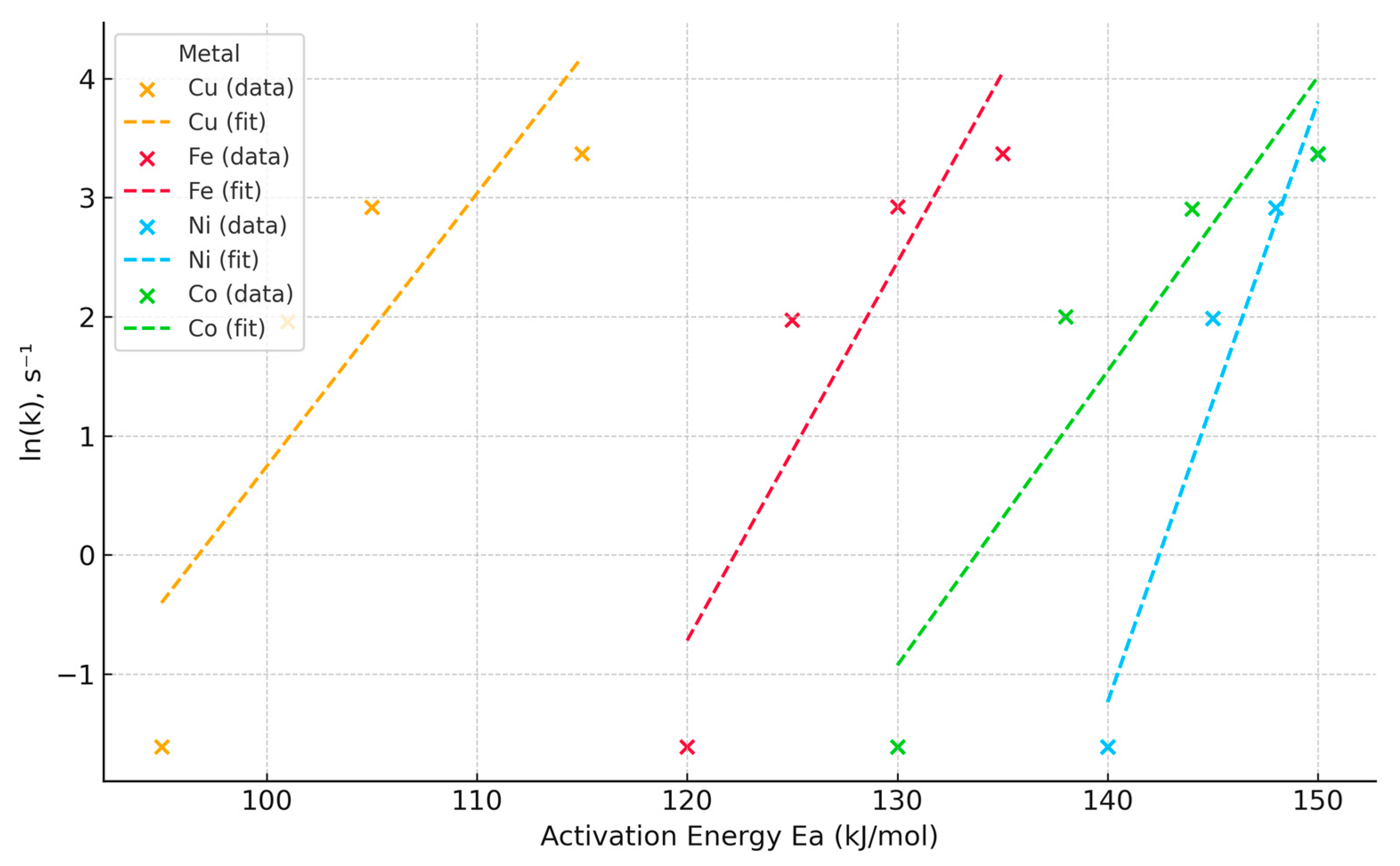

3.1. Kinetic Evaluation of the Chloride Volatilization Process

- –

- Stage I (500–650 °C): removal of lead;

- –

- Stage II (700–750 °C): chlorination of copper and iron;

- –

- Stage III (850–900 °C): volatilization of nickel and cobalt.

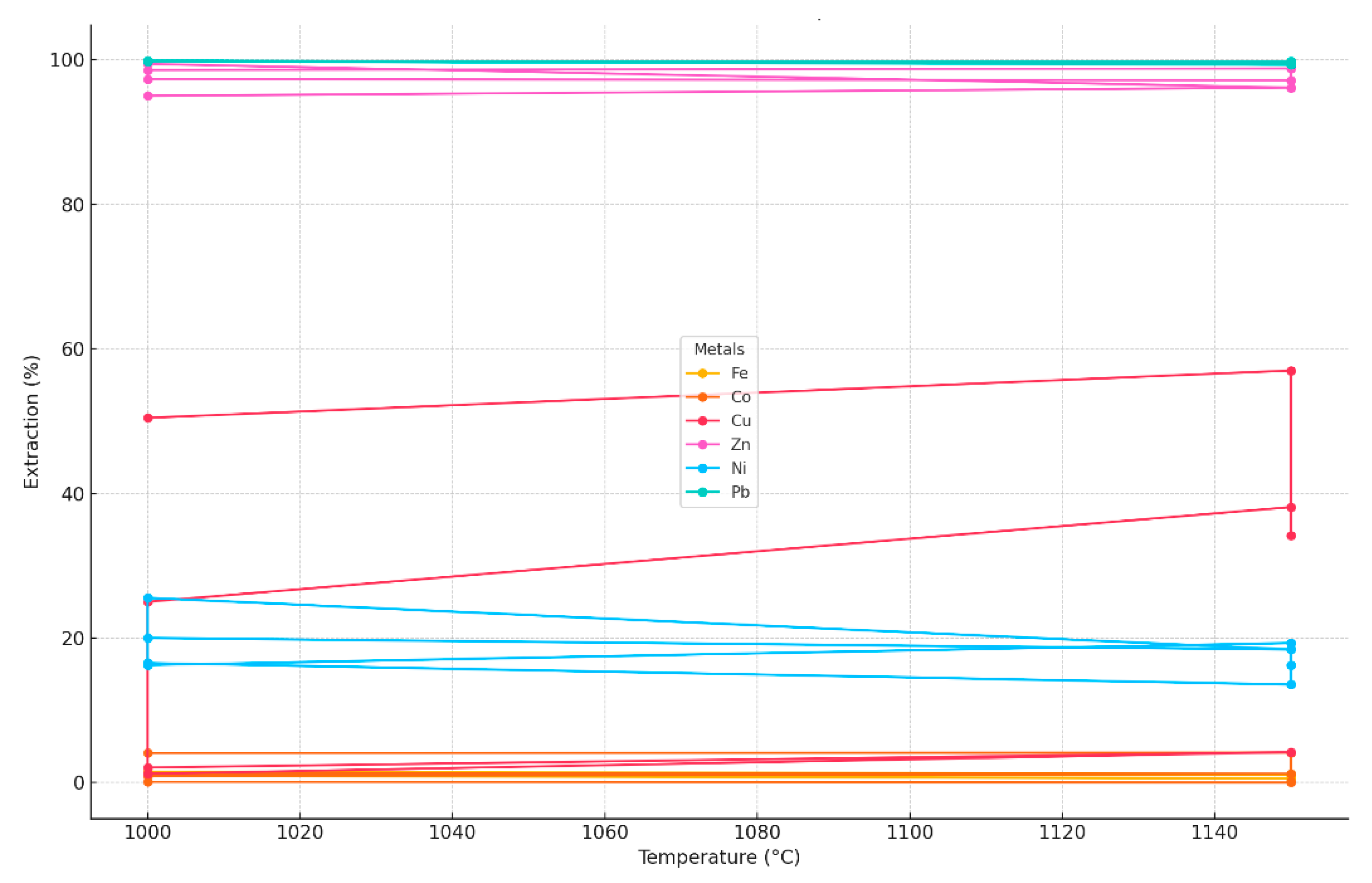

3.2. Technological Investigation Results of the Chloride Volatilization Process

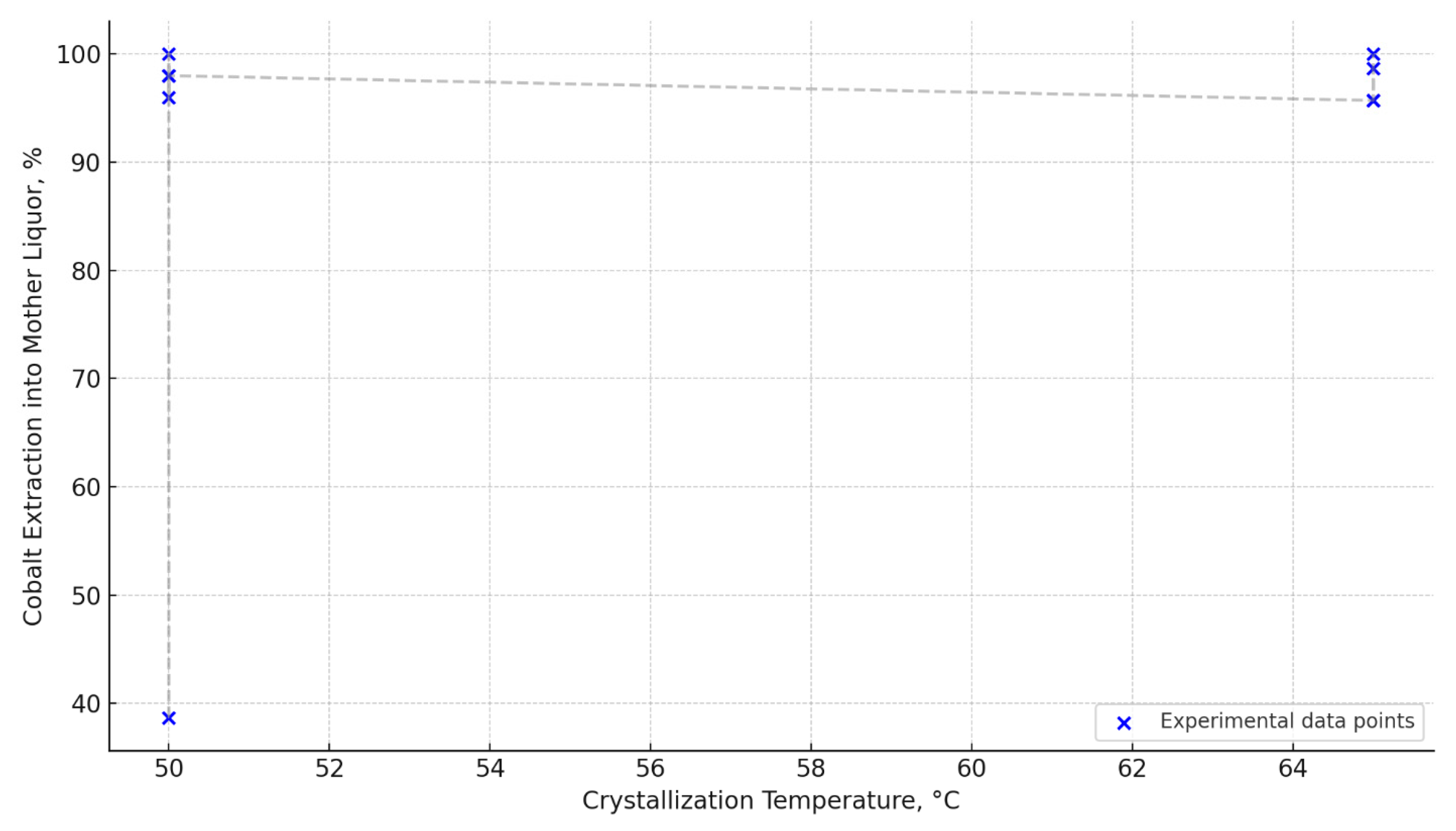

3.3. Results of the Crystallization Process of Ferric Chloride Solutions

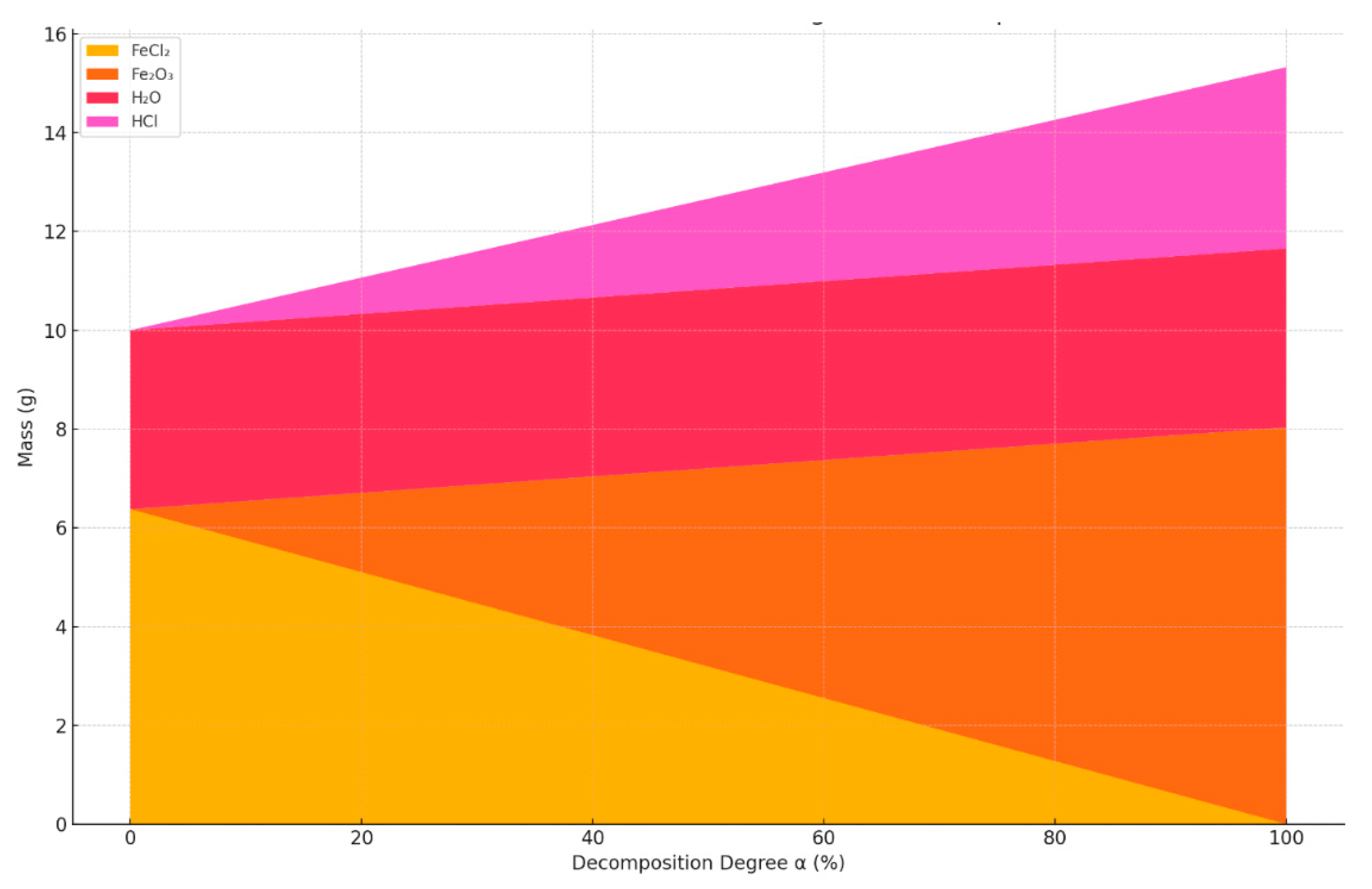

3.4. Results of High-Temperature Hydrolysis of Iron Chlorides and Production of Iron Oxide Powders

- –

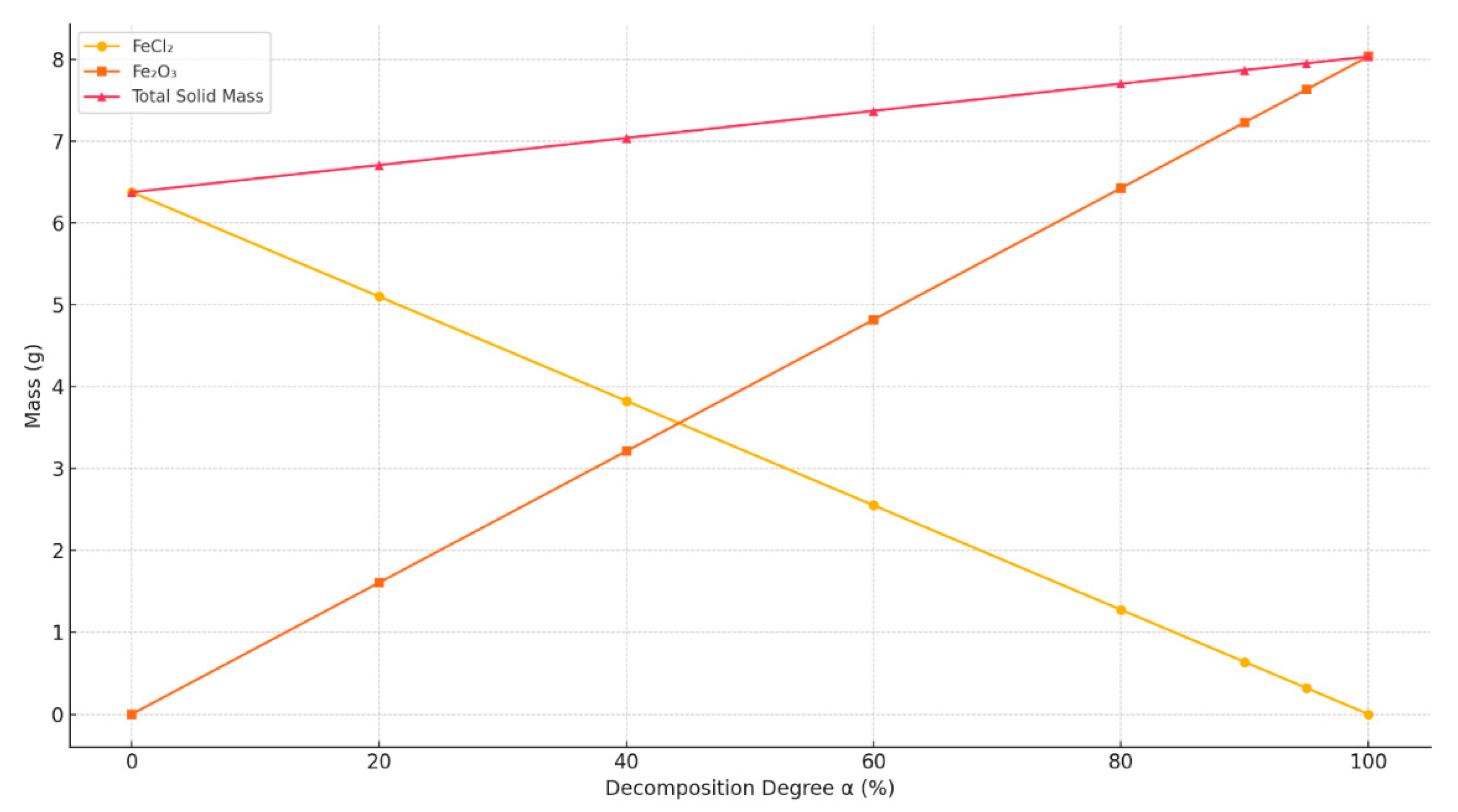

- At low decomposition levels (α = 0–40%), the solid residue is dominated by undecomposed FeCl2 or its hydrates;

- –

- In the intermediate range (α = 40–80%), transitional phases such as FeO or Fe3O4 begin to form;

- –

- At high decomposition levels (α > 90%), the residue consists almost entirely of Fe2O3.

- At α = 0%, the solid residue consists entirely of FeCl2 (~6.38 g);

- At α = 100%, the product is fully converted into Fe2O3 (~8.03 g);

- As α increases, the total mass of the solid residue also increases, due to the fact that Fe2O3 has a higher molar mass than FeCl2 on a per-Fe basis.

| α (%) | FeCl2 (g) | Fe2O3 (g) | H2O (g) | HCl (g) | Total Solid (g) | Total Volatile (g) | Total Mass (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0000 | 6.3754 | 0.0000 | 3.6246 | 0.0000 | 6.3754 | 3.6246 | 10.0000 |

| 20.0000 | 5.1003 | 1.6065 | 3.6246 | 0.7336 | 6.7068 | 4.3581 | 11.0649 |

| 40.0000 | 3.8253 | 3.2129 | 3.6246 | 1.4671 | 7.0382 | 5.0917 | 12.1299 |

| 60.0000 | 2.5502 | 4.8194 | 3.6246 | 2.2007 | 7.3695 | 5.8253 | 13.1948 |

| 80.0000 | 1.2751 | 6.4258 | 3.6246 | 2.9343 | 7.7009 | 6.5588 | 14.2597 |

| 90.0000 | 0.6375 | 7.2291 | 3.6246 | 3.3010 | 7.8666 | 6.9256 | 14.7922 |

| 95.0000 | 0.3188 | 7.6307 | 3.6246 | 3.4844 | 7.9494 | 7.1090 | 15.0584 |

| 100.0000 | 0.0000 | 8.0323 | 3.6246 | 3.6678 | 8.0323 | 7.2924 | 15.3247 |

| (1) | |||||||

| d, Å | I % | Mineral | d, Å | I % | Mineral | ||

| 5.49178 | 75.0 | - | 2.77582 | 68.2 | - | ||

| 4.36989 | 59.5 | - | 2.52700 | 62.3 | Magnetite | ||

| 3.97457 | 100.0 | FeCl2·4H2O | 2.19463 | 74.4 | - | ||

| 3.47475 | 59.7 | - | 2.18234 | 76.3 | - | ||

| 3.34786 | 60.3 | - | 2.12789 | 66.7 | - | ||

| 3.00418 | 89.6 | - | 1.73713 | 62.6 | - | ||

| (2) | |||||||

| d, Å | I % | Mineral | d, Å | I % | Mineral | ||

| 4.84037 | 36.6 | - | 2.42369 | 39.1 | - | ||

| 2.96683 | 53.9 | - | 2.09653 | 43.9 | - | ||

| 2.69821 | 35.7 | Hematite | 1.61509 | 50.2 | - | ||

| 2.52895 | 100.0 | Magnetite | 1.48287 | 54.4 | - | ||

- The mass of FeCl2 decreases linearly with increasing α;

- The mass of Fe2O3 increases linearly as α increases;

- The total mass of the solid residue increases with α, which is important to consider in solid product yield calculations and equipment loading estimates.

- The mass of FeCl2 decreases;

- The masses of Fe2O3 and HCl increase;

- The mass of H2O remains constant, as it is entirely released during dehydration, regardless of α.

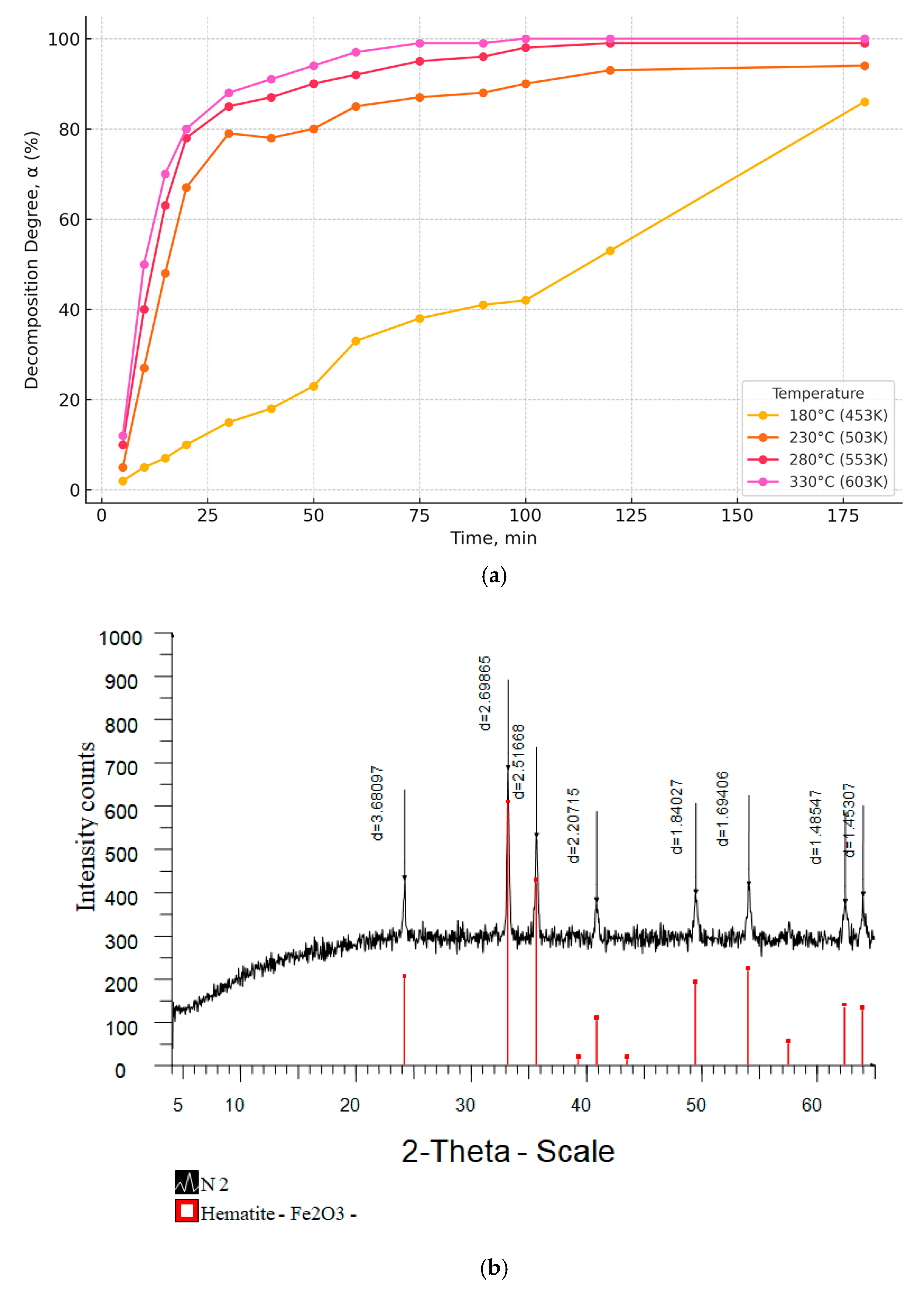

3.5. Investigation of the Mechanism and Kinetics of High-Temperature Hydrolysis of FeCl3·6H2O Crystals in an Oxidizing Atmosphere

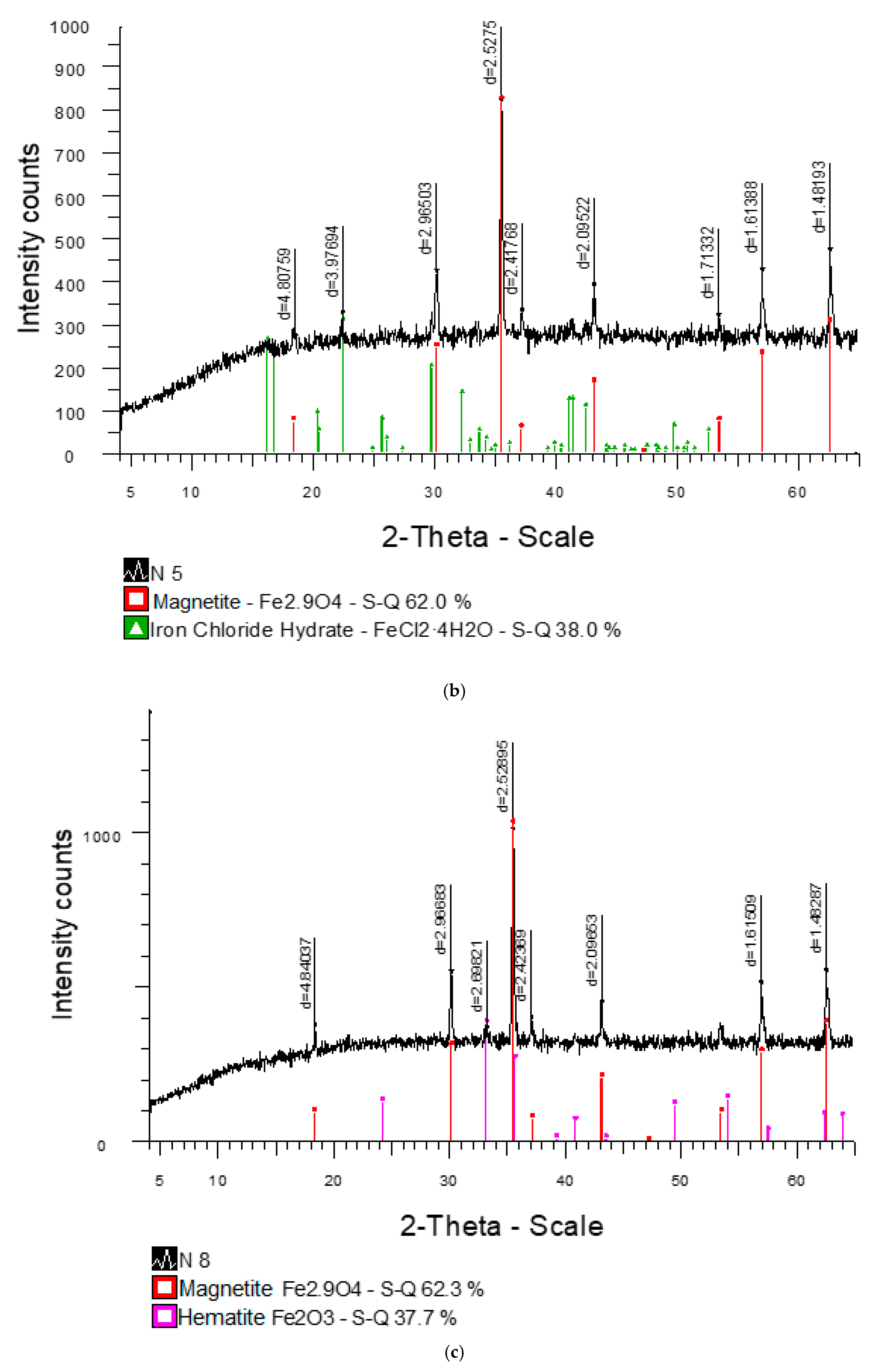

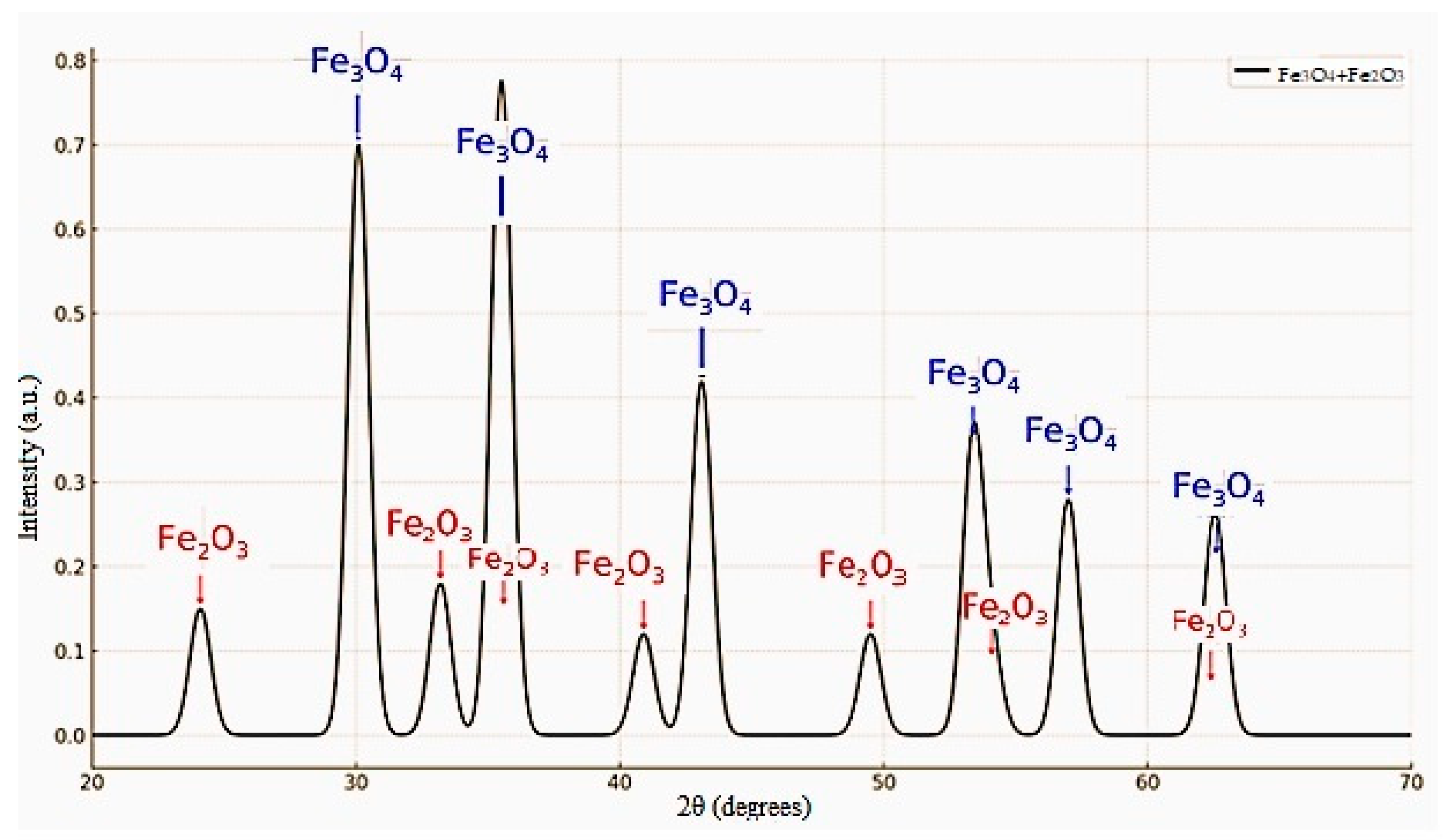

3.6. Investigation of the Composition and Properties of Powders Obtained by High-Temperature Hydrolysis of FeCl2·4H2O and FeCl3·6H2O Using Physicochemical Methods

- →

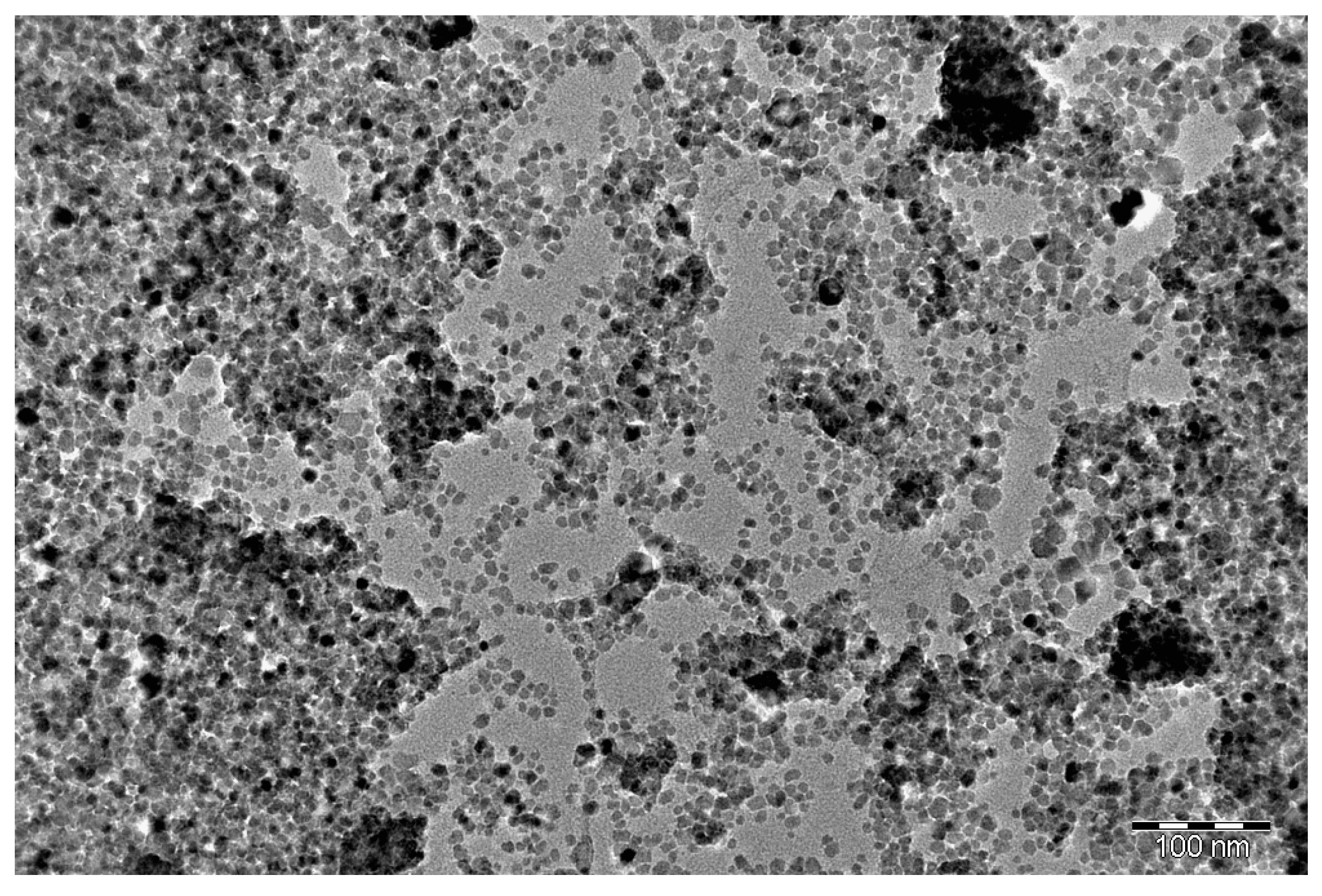

- The formation of ultrafine particles (5–30 nm);

- →

- A sharp increase in specific surface area (SSA);

- →

- Spherical, well-dispersed particle morphology;

- →

- Limited crystal growth even at high decomposition degrees.

- –

- High-temperature hydrolysis of FeCl3·6H2O is preferable for producing high-purity hematite;

- –

- FeCl2·4H2O hydrolysis yields magnetite and, with further decomposition, a mixture of magnetite and hematite;

- –

- The temperature range of 627–677 °C is optimal for producing a stable pigment mixture;

- –

- The composition of the pigment can be finely tuned by adjusting hydrolysis time and temperature;

- –

- Desired pigment color properties can be obtained: Fe2O3—bright red; Fe3O4—dark gray or black;

- –

- The results of SSA are 286 m2/g.

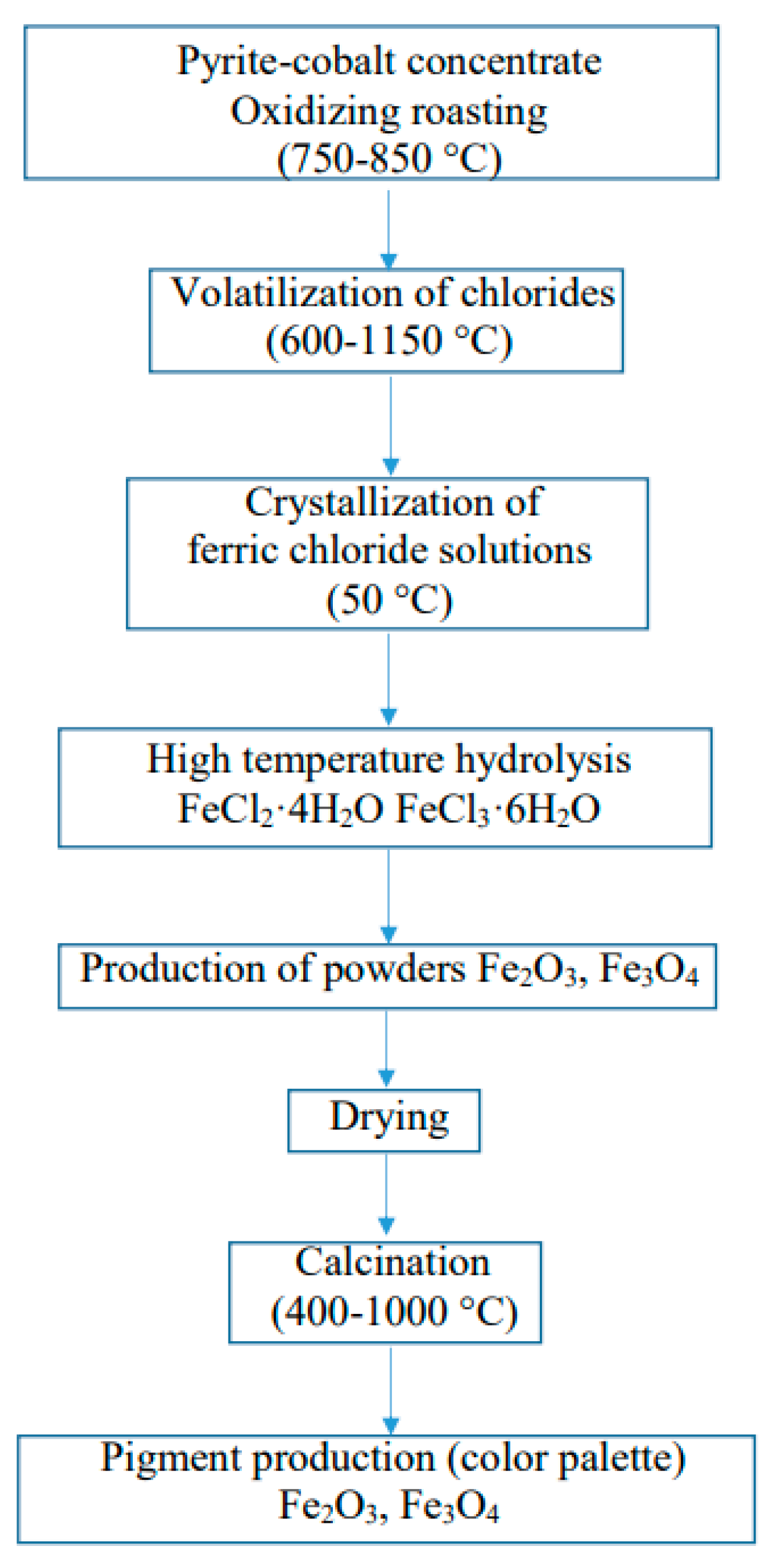

3.7. Production of Iron Oxide Pigments Fe2O3 and Fe3O4

- →

- chloride volatilization with CaCl2;

- →

- precursor formation: FeCl2·4H2O;

- →

- crystallization;

- →

- precursor formation: FeCl3·6H2O.

- →

- Removal of residual FeCl2: washing with 1–2% NaOH solution, followed by rinsing with distilled water;

- →

- Drying at 110–120 °C;

- →

- Calcination conducted in a muffle furnace at 600–1000 °C.

| Calcination Temperature | Duration | Atmosphere | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| 400 °C | 1 h | Air | Enhancement of red color (hematite) |

| 600–700 °C | 1–2 h | Air | Color deepening, crystal growth |

| 800–900 °C | 1–2 h | Air | Intense red color, increased Fe2O3 content |

| 1000 °C | 1 h | Air | Pure hematite, maximum crystallinity |

- Phase transformations and compositional changes:

- 2.

- Crystal growth and packing density:

- 3.

- Calcination atmosphere:

- 4.

- Partial conversion of hematite to magnetite:

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SSGPO | Sokolov–Sarbai Mining and Processing Production Association |

| JSC | Joint Stock Company |

| CATL | Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited |

References

- Yaylali, B.; Deveci, H.; Yazici, E.Y.; Celep, O. Extraction of cobalt from a cobaltiferrous pyrite concentrate using H2SO4-NaNO3 lixiviant system. Miner. Eng. 2023, 198, 108077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Business Research Company. Sulfuric Acid Global Market Report 2025. 2024. Available online: https://www.thebusinessresearchcompany.com/report/sulfuric-acid-global-market-report (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Research and Markets. Sulfuric Acid Market by Raw Material. Application and Region—Global Forecast to 2027. Business Wire. 2022. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20220928005916/en/The-Worldwide-Sulfuric-Acid-Industry-is-Projected-to-Reach-%2428.5-Billion-by-2027---ResearchAndMarkets.com (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Elsadek, M.; Ahmed, H.; Suup, M.; Sand, A.; Heikkinen, E.; Khoshkhoo, M.; Sundqvist-Öqvist, L. Recycling of pyrite and gypsum mining residues through thermochemical conversion into valuable products. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 199, 107219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikov, A.S.; Ye Zhakipbaev, B.; Zhanikulov, N.N.; Kolesnikova, O.G.; Akhmetova, E.K.; Kuraev, R.M.; Shal, A.L. Review of technogenic waste and methods of its processing for the purpose of complex utilization of tailings from the enrichment of non-ferrous metal ores as a component of the raw material mixture in the production of cement clinker. Rasayan J. Chem. 2021, 14, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajoki, J.; Karppinen, A.; Rinne, T.; Serna-Guerrero, R.; Lundström, M. Leaching strategies for the recovery of Co. Ni. Cu and Zn from historical tailings. Miner. Eng. 2024, 217, 108967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomchenko, N.; Muravyov, M. Sequential bioleaching of pyritic tailings and ferric leaching of nonferrous slags as a method for metal recovery from mining and metallurgical wastes. Minerals 2020, 10, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerschmidt, J.; Wrobel, M.; Mozaffari, S.; Harris, D. More out of tailings: Metal and acid production, circularity and energy transition. In Nickel-Cobalt-Copper, Proceedings of the ALTA 2024 Nickel-Cobalt-Copper Sessions, Perth, Australia, 27–29 May 2024; ALTA: Melbourne, Australia; pp. 268–279.

- Gomes, T.; da Rosa, R.; Cargnin, M.; Quadri, M.B.; Peterson, M.; de Oliveira, C.M.; da Rosa Rabelo, N.; Angioletto, E. Pyrite roasting in modified fluidized bed: Experimental and modeling analysis. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 261, 117977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.B.; Yi, L.; Song, Y. Comprehensive Utilization of Pyrite Concentrate Pyrolysis Slag by Oxygen Pressure Leaching. Minerals 2023, 13, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

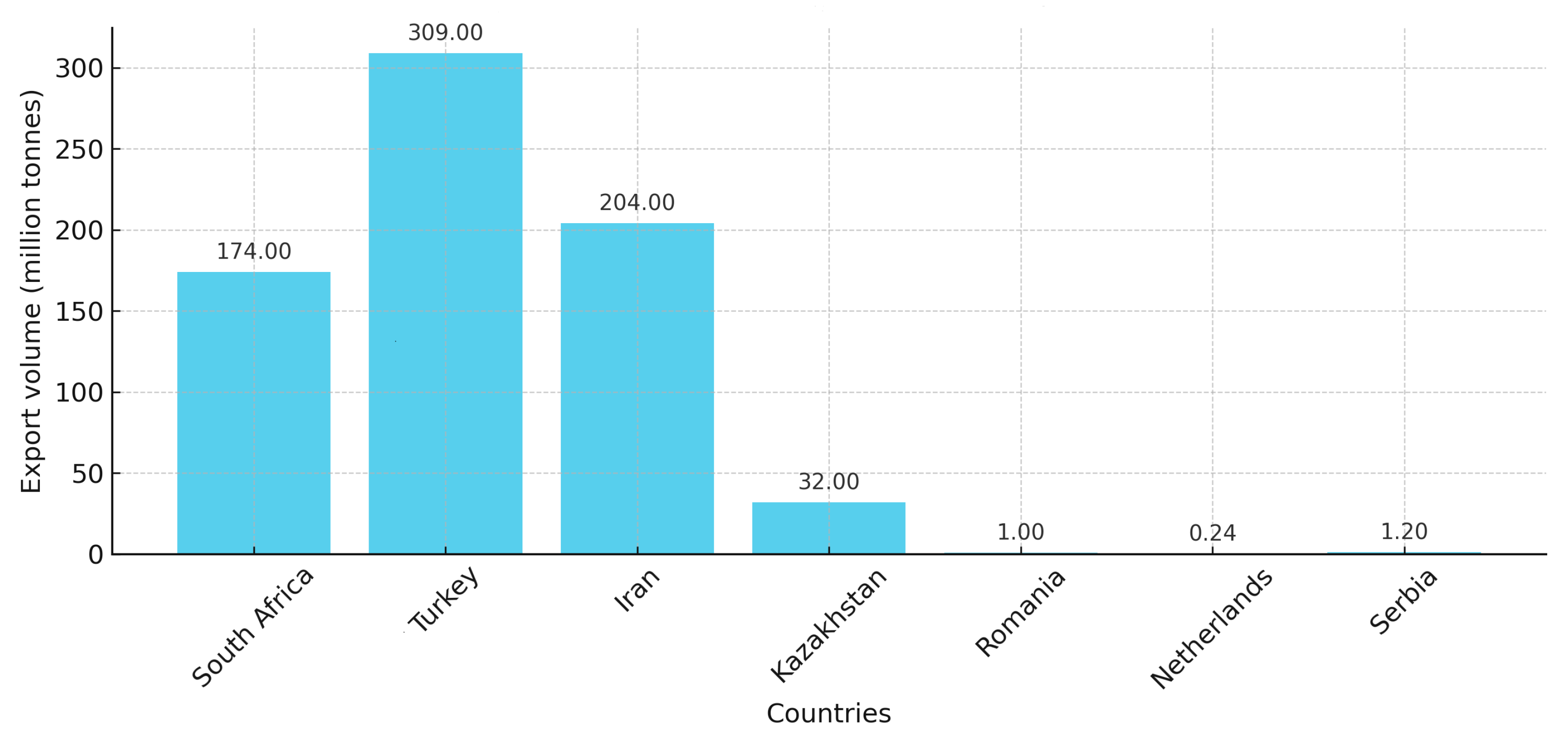

- United Nations Comtrade Database. Pyrites. Unroasted (HS Code 2502). Available online: https://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=ComTrade&f=_l1Code%3A27 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Manzoor, U.; Mujica Roncery, L.; Raabe, D.; Souza Filho, I.R. Sustainable nickel enabled by hydrogen-based reduction. Nature 2025, 641, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumiwa, J.R.; Mizik, T. Advancing nickel-based catalysts for enhanced hydrogen production: Innovations in electrolysis and catalyst design. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 109, 961–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisel, F.; Neef, C.; Marscheider-Weidemann, F.; Nissen, N.F. A forecast on future raw material demand and recycling potential of lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 192, 106920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajne, A.; Gupta, T.V.K.; Ramani, H.; Joshi, Y. A critical review on the machinability aspects of nickel and cobalt based superalloys in turning operation used for aerospace applications. Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. 2024, 10, 833–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, J.; Xing, M.; Elkins, J.; Liu, J.P. Hard and semi-hard magnetic materials based on cobalt and cobalt alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 824, 153874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopéz, R.; Jordão, H.; Hartmann, R.; Ämmälä, A.; Carvalho, M.T. Study of butyl-amine nanocrystal cellulose in the flotation of complex sulphide ores. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 579, 123655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alksnis, A. Kinetics of Roasting of Pyrrhotite; University of Toronto (Canada): Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Parpan, G.; Andrieu, B.; Vidal, O.; Delannoy, L.; Le Boulzec, H.; Gervais, M.; Jegourel, Y.; Delalande, S. Examining Copper Supply Feasibility in Decarbonization Pathways: A Mine-Level Dynamic Approach. EarthArXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.H.; Chen, W.; Fan, X.L.; Liu, J.M.; Wu, L.B. Review and prospects of bioleaching in the Chinese mining industry. International Journal of Minerals. Metall. Mater. 2021, 28, 1397–1412. [Google Scholar]

- Cháidez, J.; Parga, J.; Valenzuela, J.; Carrillo, R.; Almaguer, I. Leaching chalcopyrite concentrate with oxygen and sulfuric acid using a low-pressure reactor. Metals 2019, 9, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Zhu, D.; Pan, J.; Li, S.; Yang, C.; Guo, Z.; Xu, X. A critical review on metallurgical recovery of iron from iron ore tailings. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Jing, N.; Song, Y.; Sun, W. Green and efficient comprehensive utilization of pyrite concentrate: A mineral phase reconstruction approach. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 276, 119425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abikak, Y.B.; Kenzhaliev, B.K.; Gladyshev, S.V.; Abdulvaliev, R.A. Development of Technology for Processing Pyrite Cinder to Produce Non-Ferrous Metal Concentrate. Teknomekanik 2022, 5, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Yuan, S.; Wen, J.; He, J. Review on comprehensive utilization of nickel laterite ore. Miner. Eng. 2024, 218, 109044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.R. Recovery of Metals from Pyrite. U.S. Patent Application US2021/0156003 A1, 27 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Adhav, K.D.; Badgujar, N.P.; Alswieleh, A.; Nagaraj, K. Sustainable synthesis of iron oxide nanopigments: Enhancing pigment quality through combined air oxidation and cavitation techniques. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2024, 101, 101363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, A.S. Sinteznanostrukturirovannogookisdazheleza (III) metodomvysokotemperaturnogogidroliza [Synthesis of nanostructured iron(III) oxide by high-temperature hydrolysis]. In Proceedings of the VI Scientific and Technical Conference of Students, Postgraduates and Young Scientists “Week of Science–2016”, St. Petersburg, Russia, 18–25 April 2016; p. 311. [Google Scholar]

- Global iron oxide pigments market size of about USD 2.2 billion by 2020. Coat. Prot. 2021, 42, 17.

- Dyachenko, V.T. AlternativnyemetodypererabotkipirrotinovykhkontsentratovNorilska [Alternative methods for processing Norilsk pyrrhotite concentrates]. Tsvetnye Met. 2004, 5, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lavecchia, R.; Piga, L.; Pochetti, F.; Chacon, L. Production of titanium chloride by chlorination of ilmenite with carbon-tetrachloride. Trans. Inst. Min. Metall. Sect. C-Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. 1993, 102, C174–C178. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, N.; Taki, O.; Weissenbaeck, H.; Vogl, D. Processing Method for Recovering Iron Oxide and Hydrochloric Acid. U.S. Patent 8,628,740 B2, 14 January 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, B.; White, C. Process for the Recovery of Metals and Hydrochloric Acid. U.S. Patent No. 9,889,421, 13 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Motovilov, I.Y.; Luganov, V.A.; Mishra, B.; Chepushtanova, T.A. Oxide powders production from iron chloride. CIS Iron Steel Rev. 2018, 15, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, N.; Pownceby, M.I.; Bruckard, W.J.; Chen, M. The direct leaching of nickel sulfide flotation concentrates–a historic and state-of-the-art review part I: Piloted processes and commercial operations. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2023, 44, 407–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raabe, D. The materials science behind sustainable metals and alloys. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 2436–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abikak, Y.B.; Kenzhaliyev, B.K.; Retnawati, H.; Gladyshev, S.V.; Akcil, A. Mathematical modeling of sulfuric acid leaching of pyrite cinders after preliminary chemical activation. Kompleks. Ispolz. Miner. Syra=Complex Use Miner. Resour. 2023, 325, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Mu, W.; He, L.; Li, C.; Bi, X.; Lei, X.; Luo, S. Sustainable nickel recovery via chlorination roasting from primary and secondary resources. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 6205–6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luganov, V.A.; Chepushtanova, T.A.; Motovilov, I.Y.; Guseinova, G.D. Poluchenie poroshkov metallicheskogo i okislennogo zheleza nanodispersnykh razmerov [Production of Nanosized Metallic and Oxidized Iron Powders]; Monograph; Satbayev University Publishing House: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 2017; 150p. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. Research on the New Process of Preparing Natural Iron Oxide Red Pigment by Deep Purification of Specularite. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University, Jinan, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, M.; Singh, A. Synthesis and characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe2O3. Fe3O4): A brief review. Contemp. Phys. 2021, 62, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Gupta, S.K.; Singh, A. Determination of optical properties of γ-Fe2O3 crystalline phase synthesized from ferritin using UV-VIS absorption spectrum. AIP Conf. Proc. 2021, 2352, 020067. [Google Scholar]

- Uschakov, A.V.; Karpov, I.V.; Lepeshev, A.A. Plasma-chemical Synthesis of Fe3O4 Nanoparticles for Doping of High Temperature Superconductors. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2017, 30, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seredavina, T.; Zhapakov, R.; Murzalinov, D.; Spivak, Y.; Ussipov, N.; Chepushtanova, T.; Bolysbay, A.; Mamyrbayeva, K.; Merkibayev, Y.; Moshnikov, V.; et al. The Analysis of the ZnO/Por-Si Hierarchical Surface by Studying Fractal Properties with High Accuracy and the Behavior of the EPR Spectra Components in the Ordering of Structure. Processes 2024, 12, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimov, Y.G. High-Temperature Hydrolysis of Ferric Chloride. Bachelor’s Thesis, Satbayev University, Almaty, Kazakhstan, 2019. Available online: https://official.satbayev.university/download/document/9896/Каримoв%20Ерлан.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

| Synthesis Method | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-precipitation | Fe3O4, Fe2O3 | Simplicity, low cost | Limited control over particle size |

| Hydrothermal | Fe3O4, Fe2O3 | Morphology control, high crystallinity | Requires high temperature and pressure |

| Biosynthesis | Fe3O4 | Eco-friendliness, safety | Scale-up complexity |

| Green synthesis methods | Fe3O4, Fe2O3 | Eco-friendliness, use of renewable resources | Possible impurities, limited control over properties |

| Patented methods | Fe3O4, Fe2O3 | Innovation, enhanced pigment properties | Limited access, potential licensing restrictions |

| Element | Oxide | Element wt% | Oxide Molar Mass | Element Atomic Mass | Element Count | Element wt in Oxide | Element Fraction in Oxide | Mineralogical wt% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe | Fe2O3 | 8.68 | 159.69 | 55.85 | 2 | 111.7 | 0.6995 | 12.41 |

| Ni | Ni2O3 | 15.0 | 165.38 | 58.69 | 2 | 117.38 | 0.7098 | 21.13 |

| Co | Co2O3 | 24.0 | 165.87 | 58.93 | 2 | 117.86 | 0.7106 | 33.78 |

| Cu | Cu2O | 11.78 | 143.09 | 63.55 | 2 | 127.1 | 0.8883 | 13.26 |

| Zn | ZnO | 6.01 | 81.38 | 65.38 | 1 | 65.38 | 0.8034 | 7.48 |

| Pb | PbO | 16.4 | 223.2 | 207.2 | 1 | 207.2 | 0.9283 | 17.67 |

| Reaction | T (°C) | ΔH (kJ/mol) | ΔG (kJ/mol) | ΔS (J/mol·K) | K | logK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu2O + CaCl2 → 2 CuCl2 + CaO | 600 | 150 | 19.03 | 150 | 0.0727 | −1.14 |

| 700 | 150 | 4.03 | 150 | 0.6079 | −0.22 | |

| 800 | 150 | −10.97 | 150 | 3.4206 | 0.53 | |

| 900 | 150 | −25.97 | 150 | 14.3374 | 1.16 | |

| 1000 | 150 | −40.97 | 150 | 47.9817 | 1.68 | |

| 1100 | 150 | −55.97 | 150 | 134.6702 | 2.13 | |

| Fe2O3 + 3 CaCl2 → 2 FeCl2 + 3 CaO | 600 | 120 | 6.49 | 130 | 0.4090 | −0.39 |

| 700 | 120 | −6.51 | 130 | 2.2357 | 0.35 | |

| 800 | 120 | −19.51 | 130 | 8.9052 | 0.95 | |

| 900 | 120 | −32.51 | 130 | 28.0247 | 1.45 | |

| 1000 | 120 | −45.51 | 130 | 73.6590 | 1.87 | |

| 1100 | 120 | −58.51 | 130 | 168.1831 | 2.23 | |

| PbO + CaCl2 → PbCl2 + CaO | 600 | 80 | −7.32 | 100 | 2.7392 | 0.44 |

| 700 | 80 | −17.32 | 100 | 8.5002 | 0.93 | |

| 800 | 80 | −27.32 | 100 | 21.3590 | 1.33 | |

| 900 | 80 | −37.32 | 100 | 45.8685 | 1.66 | |

| 1000 | 80 | −47.32 | 100 | 87.3583 | 1.94 | |

| 1100 | 80 | −57.32 | 100 | 151.4753 | 2.18 | |

| Ni2O3 + 3 CaCl2 → 2 NiCl3 + 3 CaO | 600 | 180 | 40.30 | 160 | 0.0039 | −2.41 |

| 700 | 180 | 24.30 | 160 | 0.0496 | −1.30 | |

| 800 | 180 | 8.30 | 160 | 0.3946 | −0.40 | |

| 900 | 180 | −7.70 | 160 | 2.2031 | 0.34 | |

| 1000 | 180 | −23.70 | 160 | 9.3877 | 0.97 | |

| 1100 | 180 | −39.70 | 160 | 32.3888 | 1.51 | |

| Co2O3 + 3 CaCl2 → 2 CoCl3 + 3 CaO | 600 | 175 | 39.66 | 155 | 0.0042 | −2.37 |

| 700 | 175 | 24.16 | 155 | 0.0505 | −1.30 | |

| 800 | 175 | 8.66 | 155 | 0.3788 | −0.42 | |

| 900 | 175 | −6.84 | 155 | 2.0160 | 0.30 | |

| 1000 | 175 | −22.34 | 155 | 8.2513 | 0.92 | |

| 1100 | 175 | −37.84 | 155 | 27.5055 | 1.44 |

| System | Optimum T for Chloride Sublimation | Volatile Forms | Conditions for Gas Formation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ni-Cl-O | 1000 °C | NiCl3 (г) | High pCl2 |

| Co-Cl-O | 1000 °C | CoCl3 (г) | High pCl2 |

| Fe-Cl-O | 1000 °C | FeCl3 (г) | Moderately high pCl2 |

| Zn-Cl-O | 900–1000 °C | ZnCl2 (g) | Moderate pCl2, presence of CaCl2 |

| Ca-Cl-O | Not required | No | CaCl2 is stable in the liquid phase |

| Metal | Reaction | Theoretical CaCl2 Consumption (g) | Temperature (°C) | Reaction Rate Constant, k (c−1) | Activation Energy, Ea (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | Cu2O + CaCl2 → 2CuCl2 + CaO | 0.1226 | 800 | 0.1538 | 95 |

| 0.1226 | 1000 | 7.3291 | 101 | ||

| 0.1226 | 1100 | 18.6548 | 105 | ||

| 0.1226 | 1150 | 28.9697 | 115 | ||

| Fe | Fe2O3 + 3CaCl2 → 2FeCl2 + 3CaO | 0.244 | 800 | 0.1538 | 120 |

| 0.244 | 1000 | 7.3291 | 125 | ||

| 0.244 | 1100 | 18.6548 | 132 | ||

| 0.244 | 1150 | 28.9697 | 135 | ||

| Ni | Ni2O3 + 3CaCl2 → 2NiCl3 + 3CaO | 0.396 | 800 | 0.1538 | 140 |

| 0.396 | 1000 | 7.3291 | 144 | ||

| 0.396 | 1100 | 18.6548 | 148 | ||

| 0.396 | 1150 | 28.9697 | 150 | ||

| Co | Co2O3 + 3CaCl2 → 2CoCl3 + 3CaO | 0.608 | 800 | 0.1538 | 130 |

| 0.608 | 1000 | 7.3291 | 138 | ||

| 0.608 | 1100 | 18.6548 | 145 | ||

| 0.608 | 1150 | 28.9697 | 150 |

| Metal | Equation ln (k) | Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Cu | 0.240·Ea − 23.33 | Moderately sensitive to temperature |

| Fe | 0.321·Ea − 39.46 | Rapid increase in reaction rate |

| Ni | 0.505·Ea − 71.82 | Highly sensitive to temperature |

| Co | 0.257·Ea − 34.54 | Average temperature sensitivity |

| Experimental Conditions | Residue Weight (g) | Components Contention in Cinder, g | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaCl2 Consumption (% of Theoretical) | Temperature (°C) | Water Vapor Consumption (% of Required) | Sulfur Consumption (% of Charge Weight) | Charcoal Consumption (% of Charge Weight) | Fe | Co | Cu | Zn | Ni | Pb | |

| 140 | 1000 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 2.2 2.28 | 0.856 0.0861 | 0.23 0.2301 | 0.05 0.052 | 0.009 0.0023 | 0.12 0.122 | 0.0004 0.00077 |

| 100 | 1150 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2.24 2.3 | 0.859 0.0857 | 0.2349 0.235 | 0.0875 0.086 | 0.00035 0.00045 | 0.13 0.131 | 0.00025 0.00072 |

| 100 | 1000 | 100 | 3 | 2 | 2.25 2.01 | 0.86 0.0861 | 0.24 0.2390 | 0.92 0.0843 | 0.000670 0.00104 | 0.125 0.1255 | 0.0004 0.00016 |

| 140 | 1000 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2.6 2.47 | 0.86 0.0862 | 0.24 0.24 | 0.072 0.074 | 0.0006 0.00084 | 0.13 0.129 | 0.00025 0.00052 |

| 100 | 1150 | 100 | 0 | 2 | 2.07 2.14 | 0.864 0.08615 | 0.24 0.239 | 0.0775 0.0778 | 0.00285 0.0018 | 0.125 0.126 | 0.00075 0.00125 |

| 140 | 1150 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.17 2.06 | 0.865 0.08620 | 0.23 0.2301 | 0.05 0.0515 | 0.002 0.0014 | 0.12 0.124 | 0.0012 0.00098 |

| 140 | 1150 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2.36 2.53 | 0.864 0.0863 | 0.2349 0.2341 | 0.055 0.05880 | 0.00055 0.00064 | 0.129 0.127 | 0.0004 0.00113 |

| 100 | 1000 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2.06 2.21 | 0.86 0.086 | 0.2298 0.2305 | 0.0575 0.0594 | 0.00207 0.00114 | 0.125 0.126 | 0.00275 0.00098 |

| Residue Weight (g) | Extraction of Charge Components into Sublimates, % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe | Co | Cu | Zn | Ni | Pb | |

| 2.2 2.28 2.27 | 1.5 0.9 1.2 | 4.2 4.08 4.14 | 57.7 56.1 56.9 | 95 96.14 95.57 | 20 18.4 19.25 | 99.75 99.53 99.64 |

| 2.24 2.3 2.4 | 1.2 1.4 1.3 | 2.1 2.04 2.07 | 25.8 25.3 25.55 | 99.42 99.25 95.33 | 13.4 12.3 12.85 | 99.84 99.56 99.7 |

| 2.25 2.01 2.1 | 1 0.9 0.95 | 0 0.2 0.1 | 22 28 25 | 98.87 98.3 98.58 | 16.7 16.36 16.53 | 99.73 99.9 99.8 |

| 2.6 2.47 2.5 | 1 1.1 1.05 | 0 0 0 | 39 37.2 38.1 | 99 98.6 98.8 | 13.4 13.7 13.55 | 99.84 99.68 99.76 |

| 2.07 2.14 2.2 | 0.5 0.87 0.685 | 0 0.2 0.1 | 34.3 34 34.15 | 95.25 97 96.12 | 16.7 15.8 16.25 | 99.53 99.23 99.38 |

| 2.17 2.06 2.1 | 0.4 0.68 0.54 | 4.2 4.08 4.14 | 57.7 56.3 57 | 96.67 97.66 97.16 | 20 18.6 19.3 | 99.23 99.4 99.31 |

| 2.36 2.53 2.6 | 0.5 0.64 0.57 | 2.1 2.6 2.35 | 53.3 50.1 51.7 | 99.08 98.93 99 | 13.7 15.2 14.45 | 99.75 99.31 99.53 |

| 2.06 2.21 2.3 | 0.9 1 0.95 | 4.16 4.01 4.085 | 51.3 49.6 50.45 | 96.55 98.1 97.32 | 16.7 15.8 16.25 | 99.26 99.4 99.83 |

| Initial Co conc. (g/L) | Initial Co Amount (g) | Initial Fe conc. (g/L) | Crystallization Temp. (°C) | Volume After Evaporation (mL) | Evaporation Degree (%) | Co Conc. in Filtrate (g/L) | Co Amount in Filtrate (g) | Co Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 40.0 | 162.0 | 50.0 | 350.0 | 12.5 | 0.114 | 39.5 | 98.7 |

| 0.1 | 40.0 | 162.0 | 50.0 | 300.0 | 25.0 | 0.133 | 40.0 | 100.0 |

| 0.1 | 40.0 | 162.0 | 50.0 | 350.0 | 12.5 | 0.112 | 39.2 | 98.0 |

| 0.1 | 40.0 | 162.0 | 50.0 | 300.0 | 25.0 | 0.128 | 38.4 | 96.0 |

| 0.1 | 40.0 | 162.0 | 50.0 | 350.0 | 12.5 | 0.112 | 39.2 | 98.0 |

| 0.6 | 24.0 | 189.0 | 65.0 | 200.0 | 50.0 | 0.115 | 23.0 | 95.7 |

| 0.8 | 32.0 | 195.0 | 65.0 | 350.0 | 12.5 | 0.09 | 31.5 | 98.7 |

| 0.8 | 32.0 | 195.0 | 65.0 | 300.0 | 25.0 | 0.105 | 31.5 | 95.7 |

| 0.8 | 32.0 | 195.0 | 65.0 | 250.0 | 37.5 | 0.128 | 32.0 | 100.0 |

| No. | Volume After Evaporation (mL) | Co Concentration in Pregnant Liquor (g/L) | Co Amount in Pregnant Liquor (g) | Co Recovery (%) | Evaporation Degree (% of Initial Volume) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 350 | 0.2 | 70 | 83.3 | 12.5 |

| 2 | 300 | 0.253 | 76 | 90.3 | 25 |

| 3 | 250 | 0.31 | 77.5 | 92.2 | 37.5 |

| 4 | 200 | 0.42 | 84 | 100 | 50 |

| 5 | 350 | 0.2 | 70 | 83.3 | 12.5 |

| 6 | 300 | 0.251 | 75.4 | 89.8 | 25 |

| 7 | 200 | 0.41 | 82 | 97.6 | 50 |

| Duration, min | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 80 | 100 | 120 | 180 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FeCl2·4H2O, T = 330 °C | ||||||||||||

| Degree of decomposition α, % | 4.87 | 11.80 | 14.45 | 16.96 | 20.50 | 24.70 | 30.30 | 32.74 | 37.16 | 39.59 | 40.41 | 44.46 |

| FeCl2·4H2O, T = 430 °C | ||||||||||||

| Degree of decomposition α, % | 19.10 | 25.14 | 29.49 | 31.70 | 35.76 | 43.65 | 50.58 | 58.47 | 70.86 | 86.56 | 93.49 | 95.11 |

| FeCl2·4H2O, T = 530 °C | ||||||||||||

| Degree of decomposition α, % | 41.95 | 68.87 | 85.16 | 94.82 | 96.00 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 |

| FeCl2·4H2O, T = 630 °C | ||||||||||||

| Degree of decomposition α, % | 60.53 | 92.83 | 97.40 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 |

| Decomposition Degree α | Residual Composition | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| α < 30% | FeCl2·xH2O + FeCl2 partially decomposed | Chloride form dominates |

| α ≈ 50–70% | FeCl2 + FeO/Fe2O3 (mixture) | Intermediate composition |

| α > 90% | Fe2O3 + Fe3O4 (depending on conditions) | Oxide phases, almost no Cl− |

| α ≈ 100% | Almost pure Fe2O3/Fe3O4 | Complete transformation |

| α (%) | Fe2O3 (g) | D10 (μm) | D50 (μm) | D90 (μm) | SSA (m2/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.5000 | 2.5000 | 4.0000 | 4580.1527 |

| 20.0000 | 1.6065 | 1.2120 | 2.0200 | 3.2320 | 5668.5058 |

| 40.0000 | 3.2129 | 0.9240 | 1.5400 | 2.4640 | 7435.3128 |

| 60.0000 | 4.8194 | 0.6360 | 1.0600 | 1.6960 | 10,802.2469 |

| 80.0000 | 6.4258 | 0.3480 | 0.5800 | 0.9280 | 19,742.0374 |

| 90.0000 | 7.2291 | 0.2040 | 0.3400 | 0.5440 | 33,677.5932 |

| 95.0000 | 7.6307 | 0.1320 | 0.2200 | 0.3520 | 52,047.1895 |

| 100.0000 | 8.0323 | 0.0600 | 0.1000 | 0.1600 | 11,450.8168 |

| Indicator | Tendency with Increasing α | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| D10 (μm) | decreases from 1.5 to 0.06 | reducing the size of the smallest 10% particles—finer powder |

| D50 (μm) | decreases from 2.5 to 0.1 | the median particle size is significantly reduced—the powder becomes ultrafine |

| D90 (μm) | decreases from 4.0 to 0.16 | the size of even the largest 10% of particles decreases—the range of sizes narrows |

| Δ (D90–D10) | narrows from 2.5 to 0.1 | indicates a narrower particle size distribution at high α |

| Duration, min | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 80 | 100 | 120 | 180 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FeCl3·6H2O, T = 180 °C | ||||||||||||

| Degree of decomposition, α % | 0.00 | 5.13 | 6.59 | 7.83 | 12.39 | 18.19 | 23.10 | 32.95 | 37.91 | 41.40 | 52.50 | 86.30 |

| FeCl3·6H2O, T = 230 °C | ||||||||||||

| Degree of decomposition, α % | 0.00 | 25.44 | 47.04 | 68.14 | 77.57 | 78.41 | 81.23 | 85.23 | 88.55 | 91.65 | 94.01 | 94.92 |

| FeCl3·6H2O, T = 280 °C | ||||||||||||

| Degree of decomposition, α % | 3.83 | 43.88 | 63.09 | 77.45 | 83.93 | 88.72 | 96.32 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 |

| FeCl3·6H2O, T = 330 °C | ||||||||||||

| Degree of decomposition, α % | 10.48 | 48.11 | 67.37 | 79.65 | 85.68 | 89.68 | 97.00 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 | ≈100 |

| (1) | ||||||||||||

| d, Å | I % | Mineral | d, Å | I % | Mineral | |||||||

| 2.70594 | 100.0 | Hematite | 2.10782 | 73.2 | - | |||||||

| 2.55417 | 86.4 | - | 1.48704 | 82.1 | - | |||||||

| 2.51626 | 89.3 | - | - | - | - | |||||||

| (2) | ||||||||||||

| Products Composition | Formula | Contention, % | Hydrolysis Temperature, °C | |||||||||

| Hematite | Fe2O3 | 100 | 330 | |||||||||

| Phase | Formula | Mass Fraction (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetite | Fe3O4 | 60–80 | Main product at ~60% decomposition |

| Hematite | Fe2O3 | 10–30 | Appears at higher decomposition degrees (>60%) |

| Residual iron chloride | FeCl2 | 0–10 | Remains if decomposition is incomplete |

| Temperature, °C | Element Content, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | Cl | Fe | Total | |

| FeCl2·4H2O | ||||

| 430 | 24.3 | 13.2 | 62.5 | 100.00 |

| 630 | 27.6 | - | 72.4 | 100.00 |

| FeCl3·6H2O | ||||

| 603 | 29.55 | - | 70.45 | 100.00 |

| Conditions | Dominant Phase | Pigment Color |

|---|---|---|

| 430 °C, α ≈ 60% | Fe3O4 (magnetite, ~62%), residual FeCl2 | Black/dark gray |

| 630 °C, α > 60% | Fe3O4 (62%) + Fe2O3 (38%) | Dark brown |

| 727–827 °C, α ≈ 100% | Fe2O3 (hematite, >90%) | Red–brown/red |

| Pigment Composition (wt.%) | Fe3O4 (%) | Fe2O3 (%) | Color | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90–100% Fe3O4 | ≥90 | 0–10 | Black | Primers, masking agents |

| 70% Fe3O4/30% Fe2O3 | 70 | 30 | Dark brown | Metal coatings |

| 50% Fe3O4/50% Fe2O3 | 50 | 50 | Brown | Construction mixtures |

| 20% Fe3O4/80% Fe2O3 | 20 | 80 | Red–brown | Architectural pigments |

| ≥90% Fe2O3 (hematite) | 0–10 | ≥90 | Red | Ceramics, paints |

| Temperature (°C) | Main Phase | Pigment Color |

|---|---|---|

| 400–600 | Fe2O3 (hematite) | Red |

| 700–800 | Fe2O3 + Fe3O4 | Red–brown |

| 900–1000 | Fe3O4 dominates | Dark red/black |

| Calcination Temperature | Main Phase | Color | Crystallinity | Porosity | Magnetism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 400 °C | Fe2O3 | Dark red | Medium | High | Non-magnetic |

| 700 °C | Fe2O3 | Bright red | High | Medium | Non-magnetic |

| 900 °C | Fe2O3 | Intensely red | Very high | Low | Non-magnetic |

| 1000 °C | Fe2O3 | Dark red | Maximum | Very low | Non-magnetic |

| 600–800 °C (Fe3O4 dominates) | Fe3O4 | Red-black/Brown | High | Medium | Ferromagnetic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chepushtanova, T.; Altmyshbayeva, A.; Merkibayev, Y.; Mamyrbayeva, K.; Yespenova, Z.; Mishra, B. Development of Technology for Processing Pyrite–Cobalt Concentrates to Obtain Pigments of the Composition Fe2O3 and Fe3O4. Metals 2025, 15, 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15080886

Chepushtanova T, Altmyshbayeva A, Merkibayev Y, Mamyrbayeva K, Yespenova Z, Mishra B. Development of Technology for Processing Pyrite–Cobalt Concentrates to Obtain Pigments of the Composition Fe2O3 and Fe3O4. Metals. 2025; 15(8):886. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15080886

Chicago/Turabian StyleChepushtanova, Tatyana, Aliya Altmyshbayeva, Yerik Merkibayev, Kulzira Mamyrbayeva, Zhanat Yespenova, and Brajendra Mishra. 2025. "Development of Technology for Processing Pyrite–Cobalt Concentrates to Obtain Pigments of the Composition Fe2O3 and Fe3O4" Metals 15, no. 8: 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15080886

APA StyleChepushtanova, T., Altmyshbayeva, A., Merkibayev, Y., Mamyrbayeva, K., Yespenova, Z., & Mishra, B. (2025). Development of Technology for Processing Pyrite–Cobalt Concentrates to Obtain Pigments of the Composition Fe2O3 and Fe3O4. Metals, 15(8), 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15080886