Abstract

This article reports on the findings from a social anthropological ethnographic study conducted within the area of women’s freestyle wrestling in Barcelona. The study focused on exploring female wrestlers’ experiences of the connection between their participation and visibility in this sport and the hegemonic gendered cultural schemas established within our society in relation to gender. The ethnography comprised participant interviews and observations which enabled an exploratory thematic analysis of the relevant experiences of female wrestlers and situates these in the context of gender relations in the sport and in society. The preliminary findings are that freestyle wrestling in this context remains a sexist environment and wrestling shows still include stereotyped discourses when it comes to the staging of women’s matches. While there has been some development in terms of female participation in this environment, male dominated discourses, practices and infrastructures still represent a significant barrier for the development of women’s wrestling in Spain.

1. Introduction and Context of Women’s Wrestling

My aim with this paper is to analyse women’s wrestling in the city of Barcelona. The geographical focus was decided as a result of this being the only province in Catalonia to have a freestyle wrestling school. There are women’s wrestling schools in three other cities around Spain (Barcelona, Madrid, Bilbao and Seville) and, as such, these are also areas where freestyle wrestling shows are held. This study focuses on the area of women’s wrestling and therefore, I will look at female wrestlers who have already made their competitive debut and others who are just starting out, training in a school1 with a view to entering a wrestling show at a later date.

In order to gain an understanding of the issues I analyse, in what follows I begin by establishing some context with regard to the sport of women’s wrestling in Spain.

Women’s wrestling was introduced to Spain in the 1990s with the GLOW2 show, which had been running in the United States since 1986. The Telecinco channel, the Spanish broadcaster, renamed it ‘Las Chicas con las Chicas’ (Girls vs. Girls) for the Spanish audience. Telecinco did not dub the original into European Spanish, broadcasting the Latin American Spanish version, although they did contract the services of the commentator, Héctor del Mar.3

Women’s wrestling came back to television in 2006, when the sport enjoyed a popularity boom until 2010, and then the network pulled the show due to low viewing figures. In that same year, a new Spanish TV channel called Marca TV bought the rights to the programme, broadcasting it until 2013 when the channel was closed down. Subsequently, from 2014 onwards, there has only be one wrestling programme on TV, broadcast by the Neox channel, which is owned by the Atresmedia company (Antena 3 Spain).

Additionally, as fans of the sport, we have been able to observe other specific elements in an attempt to further contextualise the standing of female wrestling, which will be discussed later on. The matches that have been given TV air time were frequently viewed as sexualized matches, providing an objectified view of women which focused on their beauty and attractiveness as opposed to the sporting and technical aspects of freestyle wrestling [1]. Examples of matches of that era include the Bra and Panties match, Divas Water Fight, Halloween Divas Battle Royal, Diva Search, Diva Dance Off, PlayBoy Evening Gown, Lingerie Match, Lingerie Contest, Divas Swimsuit Match, Bikini Contest, etc.

With the arrival of female wrestlers such as Becky Linch, Bayley, Sasha Banks or Charlotte, the focus has shifted, with the emphasis now on the technical skills possessed by the female wrestlers. Despite these changes, however, not everything is perfect and egalitarian and, as such, demonstrations of sexism continue to creep in from time to time. An example of this is the WWE’s continued publication of photos of female wrestlers wearing bikinis or lingerie on its official website when, conversely, male wrestlers are never portrayed in similar scenarios. Due to the low visibility of the female wrestlers, in 2013, WWE produced a docu-reality show4 called Total Divas, which mainly follows the private lives of the female wrestlers that star in the show.

Looking at women’s wrestling at a more local level, it is notable that, despite being largely male-dominated, wrestling has been around since the 1920s in Spain. Unfortunately, it has been impossible to unearth any information about the early days of women’s wrestling in Barcelona. The earliest match referenced online took place in 2010 and featured two male and two female wrestlers in teams of two. The ring names of the female wrestlers were Erin Angel and Shanna. They were from Britain and Portugal, respectively, and therefore not local. This gives us valuable information on the limited scale of women’s participation in wrestling within Barcelona as the promoters were forced to bring in independent wrestlers from other countries in order to stage female bouts in Barcelona. The term ‘independent wrestler’ means a wrestler not affiliated to any specific freestyle wrestling company and consequently available to be ‘contracted’ by various companies/schools to wrestle anywhere in the world.

A few years later, in 2013, Spanish Pro Wrestling5 (SPW) made its opening debut as a school and among the wrestlers competing under its banner, we find Dragonita (little dragon) taking part in a number of shows. Amazing Montse also later joined SPW, in 2014, becoming only the second female wrestler at the school at the time. A second wrestling school, Riot Wrestling, opened in Barcelona, in 2015.

In this article, I will refer to the female wrestlers by their artistic name. Before continuing, I explain the reason for the use of the wrestler’s ring names in this paper rather than their personal ones. As the study discusses the visibility of women in this sport, it seems apt that we should promote (to a certain degree) their characters and thus put the focus on the efforts they have made and/or are making in order to become professional wrestlers [2]. If their real names had been included, it is highly unlikely that anyone (within the world of wrestling) would know who they were. I also obviously informed the female wrestlers themselves of my intention to refer to them by their professional ring names and they were delighted with the idea. In short, it is a small gesture to thank them for giving up their time and agreeing to be interviewed without expecting anything in return. This way, if any wrestling enthusiasts are interested in doing so, they will be able to begin following the professional careers of these women.

To begin with, the only female wrestler there was Daphne, but as time went on, the other women I interviewed became members as well. Some, like La Penitencia (The Penance) have now retired from the sport, and other girls have decided to take a break but intend to return. The rest continue to train towards match appearances. The year 2015 also marked the launch of Revolution Championship Wrestling, a wrestling company set up with the aim of promoting the sport in Barcelona, with a number of women’s matches organised as part of their programme.

It should also be noted that, of all the women involved in the sport, Dragonita (little dragon) is the only Spanish female wrestler who is active on the professional circuit. It is important to differentiate between the terms ‘female wrestler’ and ‘professional female wrestler’, since the second category refers to an athlete ‘contracted’ by other companies and who earns money for match appearances. Non-professional wrestlers are able to fight in shows organised by their school or other schools, but they do not receive a fee.

As such, she is a well-known figure on the wrestling scene, where she has even been recognised by winning awards such as that of the best European wrestler in 2014 and the 2016 Planeta Wrestling award6 for the best Spanish wrestler of the year7. A look at the award categories from a linguistic point of view reveals the use of Spanish terminology in a form that corresponds to male competitors, thus rendering the presence of women in the sport invisible. It is true, that not many women had been involved in the sport in Spain up to that point. However, this dynamic is now changing as a result of a new wave of female wrestlers training towards making their match debut and entering the scene where others have already debuted and continue to compete regularly.

More puzzling still is the fact that no category exists to recognise the best women’s European and Latin American wrestler (despite there being a men’s category) when the fact is that there is a very active and well-represented women’s wrestling scene in these countries. This is another example of the fact that the presence of women in this sport is not fully established. Perhaps the introduction of female categories for awards such as these would act as a motivating factor for the women and increase their visibility. Although I do appreciate that both male and female wrestlers are able to compete in the same category to be named the best wrestler, it would only require the inclusion of the feminine grammatical form to put both sexes on an equal footing, as, at present, there is a predisposition towards the use of the masculine linguistic form in Spanish8 when referring to gender, (e.g., todos and nosotros are in the masculine form). For this to occur, however, it would be necessary to ask the female wrestlers their opinion on the matter (giving them a voice and calling for their involvement).

Returning to the subject of female wrestlers at a local level, Amazing Montse joined the SPW school in 2014 and made her debut in her first year, going up against Dragonita (little dragon) in a show organised by Spanish Pro Wrestling (Figure 1) She went on to compete in several more matches that year with her school (going up against male competitors from her school because there were no other female contestants) until she decided to give up the sport due to work commitments, as she was holding down two jobs (outside of wrestling).

Figure 1.

Dragonita (little dragon) vs. Amazing Montse, a singles match as part of a Spanish Pro Wrestling show in 2014. Photo: LPV Photography.

Because of this lack of female competitors, there was no choice but to pair Dragonita (little dragon) up with Amazing Montse in a match organised by their school. For Amazing Montse this match marked her debut since she had only been at the school for a short time. Dragonita (little dragon), on the other hand, had already made her debut and had experience fighting in a number of previous matches. The matches Dragonita (little dragon) had taken part in up to then had all been mixed gender, i.e., she went up against other male wrestlers either from her school or from schools in other countries (who were occasionally able to collaborate with her school).

Establishing some context with regard to women’s wrestling has been useful for the analysis of the questions posed in relation to women’s wrestling at a local level (Barcelona). The influence of the WWE is also worth noting, as all the women interviewed talked about “starting out”, explaining how they became interested in the sport as a result of watching a TV programme called, WWE. Their comments reflected the level of visibility female wrestlers enjoyed at that time and revealed the impact the experience had on them, influencing their perception and understanding of wrestling.

2. Use of Theory

The purpose of the study was to conduct an exploratory analysis into the gendered experiences and context of women wrestlers participating in Barcelona. Given the exploratory and preliminary nature of the findings presented, a number of the sections which follow focus on capturing and presenting the emic, participant-derived meanings, in the data collected. I interrelate this data with the discourses identified in women’s wrestling shows in Barcelona, and focus on perceptions based on a range of sensitising questions, such as: Do female wrestlers have the same levels of visibility and impact as male wrestlers? How many female wrestlers are there in Barcelona? How often do we see women participating in this sport? What kind of cultural transmission exists for women in relation to participation in this sport? What is the discourse in terms of wrestling shows? Is the accompanying discourse important with regard to promoting female participation?

As the analysis is preliminary it does not undertake to provide a fully developed conceptualised account. Nevertheless, the analysis is informed by selected concepts from the fields of gender and sport. Firstly, I draw on the issue of the physical body with regard to the meanings that are culturally attributed to it, such as, for example, discourses on biological determinism. The fact that this issue is based on a naturalisation of these cultural patterns is very interesting in terms of enabling us to understand the visibility and participation of women in this sport. Secondly, (and continuing with the cultural question), I explore the negative implications that arise from the social and cultural construction that is established in relation to gender (in this case, women) through the ideas of gender binaries and hegemony. As they have the capacity to appropriate stereotypes, inequalities and gender classifications, which collectively act to relegate women’s participation in wrestling to the background. Due to the exploratory nature of the analysis presented later in the paper, I develop these concepts at their point of use in the relevant sections below.

3. Study Methodology

The research ethics of this research project were approved by Carles Siches. The ethnography was based on observations of the physical culture of wrestling in Spain, and semi-structured interviews with female wrestlers who have been and are currently involved in freestyle wrestling. An interview was also conducted with Gascó, the only active wrestling show promotor who is operating in Barcelona (Revolution Championship Wrestling—as it features women’s matches within the events it organises). This is an independent Barcelona-based company involved in promoting wrestling events both nationally and internationally. They regularly organise between three and four events a year and frequently feature female wrestling matches on their event posters. The women’s bouts even get top billing on some occasions. One example of which was an all-female programme of matches they put together for two of their events (one in Japan and one in Barcelona). I have also included observations with regard to a number of wrestler training sessions and informal interviews conducted with audience members at various shows organised by the two schools.

Two interviews were conducted with each female wrestler, each 1.5 to 2 h long, and a total of nine wrestlers were interviewed. Following the interviews, I kept in touch with the subjects in the study by phone, contacting them to ask follow-up questions and resolve any doubts that came up [3]. We also met when I attended shows and had informal conversations. The nine female wrestlers I interviewed saw this as a positive step, with these shows providing an opportunity for increased visibility and greater participation. These independent female wrestlers have appeared in a number of shows staged in Barcelona and, consequently, the women I interviewed have had the opportunity to meet their role models, an experience which has consequently encouraged them to stick with the sport and fuelled their ambition to appear in a professional show (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Taken from an Instagram post showing Rinn Laree at a show by Revolution Championship Wrestling.

My interview with wrestling promoter, Carlos Gascó, lasted almost two hours and was also followed up with emails, messages and meetings at various wrestling shows around Barcelona. As a result of this interaction, he subsequently suggested I ‘participate’ on a small scale in the organisation of the shows for his company, Revolution Championship Wrestling. I was responsible for contacting a Spanish company involved in promoting and buying tickets for the events. My job was to publicise the event in order to encourage people to buy tickets and go to see the shows staged by his company. Whenever we met at shows, (as we knew each other) we would often have conversations about current wrestlers, as he was attending shows organised by schools in order to see if he could incorporate any of the wrestlers into the programme for his company’s shows.

Finally, there was little opportunity to carry out any observations during the course of 2016 as Dragonita (Little Dragon) was in London and rarely came back to Spain to appear in matches with her former school. Amazing Montse was already in the process of retiring from the sport as she was finding it hard to keep up her training due to work commitments (away from wrestling). Similarly, La Penitencia (The Penance) was no longer appearing in any matches and, in fact, left the school and, therefore, gave up wrestling shortly afterwards. The observations were more consistent in 2017, as I attended the shows organised by the schools on a monthly basis. The majority of the interviews conducted were with members of the Riot Wrestling School because that was where there were female wrestlers training. I also attended a Revolution Championship Wrestling show. I was only able to attend one of these shows as the company also organises shows in other parts of Spain (Madrid, Seville etc) where the wrestling scene is slightly more active, although their main focus is outside of Spain, as their goal is to raise the company’s profile and attract wrestlers from other countries to take part in matches in Spain in the future. In 2017, they held shows in Seville, the USA and the United Kingdom. However, due to the high cost involved in organising shows of this kind, a lack of financial resources is a limiting factor with regard to the number of events they are able to stage.

In addition to the interviews conducted (semi-structured and unstructured/informal), I also wanted to supplement the research with observations recorded at training sessions, shows organised by the respective schools and shows organised by the wrestling promoter interviewed. I felt that this would provide a key resource in support of the narratives obtained through the interviews and enable us to compare these perspectives with our own observations. Gaining first-hand knowledge of the social space in which the wrestlers interact was key to understanding and describing the reality of the situation. I would have liked to have been able to record more observations, but I only had the opportunity to watch two women wrestlers competing in the ring during the course of my research study because the women involved were still training for their debut appearances and that made it impossible to see them in action on a more regular basis.

Faced with this problem, I also made a point of attending all the shows organised by the two schools in Barcelona because I thought it was important to be able to observe the discourse in action at those events. That is to say, to gauge the male predominance9, the type of dialogue transmitted by the wrestlers (thus developing what is known as the ‘storyline’), the types of characters portrayed by the wrestlers, the audience reaction, etc. These factors have enabled me to draw a number of important conclusions, such as the significance of discourses based on biological determinism in terms of the body and involvement in the sport. I took a notebook along to all the events I attended and recorded everything I felt was important to highlight. My principle focus was the audience, taking note of the numbers of people attending and the audience profile, as well as the comments made by audience members. My observations are also supported by a collection of photographs and a number of video clips. I thought it important to provide photos as a more accurate way of describing the venue and the events referenced. A visual image is often better than a narrative, which is why I opted for this course of action. In terms of the video clips, these show the ring entrances made by the two female wrestlers who made their competitive debuts during the course of the research stage of the study. I wanted to convey the way in which they portrayed themselves through their character, as well as show the audience’s reaction to the female wrestlers once they left the ring.

As mentioned, the analysis of data reported here is preliminary and ongoing. The approach taken might be best described as a thematic analysis which Smith and Sparkes [5] describe as, “a method that minimally organises and describes the data collected in rich detail by identifying, analysing, interpreting, and reporting patterns (that is, themes) within data” (p. 123). The reason this was selected was because in thematic analysis “writing is openly part of the analysis” [5] (p. 124) and, moreover, because it is a flexible and straightforward approach to analysing data. Given the preliminary and exploratory nature of the study, the focus of the analysis was to immerse myself in the data gathered and develop overarching themes. These were then reviewed to see if they were consistent across the data collected (the interview participants, the observational data, etc.). Importantly, the themes identified below are a combination of emic and etic themes. That is, the themes built around the context of the training and shows were participant-based (emic) and the themes around gender differences were conceptual (and therefore etic). As writing up a thematic analysis is part of the analysis itself, I opted to present the data in a way which provides as much rich description as possible and set these alongside the participant’s voices. The intention here is to take the reader into the world of wrestling in Spain from a women’s perspective.

With regard to the methodology implemented, it should be noted that it became necessary to divide the interviews into two parts. This is due to the fact that the study began in 2016. During that year I interviewed three female wrestlers [Dragonita (little dragon), Amazing Montse and La Penitencia (The Penance)]. The first two, both 25 years old, belonged to the Spanish Pro Wrestling School. The year after I had completed the first part of my research, I had the opportunity to conduct an in-depth study of the second school, at which point I was able to ascertain the precise number of female wrestlers involved in the sport in Barcelona. I found that the second school had six female members (Hannah, Andrea Rose, Daphne, Mina, Rinn Laree y Noemí), aged between 19 and 26. Looking at the participation rates for male wrestlers within the same school provides an interesting comparison. In total, there were approximately fifty wrestlers affiliated with the second school (Riot Wrestling). Only six of those fifty were women, a number which goes some way to demonstrating the prevalence of male participation [6] in comparison to female participation in the Barcelona area. I have since been able to identify a number of reasons for this during the course of the study.

4. Findings

4.1. Unequal Participation but Equal Treatment in the Gym Environment

The programme of shows organised by the school usually finishes at the end of June/beginning of July. They end for summer and the new season starts up again in September. A show is held every month during the ten-month-long season and represents an opportunity for the male and female wrestlers to put everything they have learned in their training sessions into practice. As a sport that has an aspect linked to entertainment, there is a group of people responsible for establishing a storyline for each show so that each wrestler (male and female) has a role to play and the story rolls over into the following month, forming something akin to a series as each event marks the start of a new episode that picks up from the previous one. Hence, it provides a kind of ‘hook’ for the fans that follow wrestling. The shows, as far as I could see, almost always attract the same groups of people. They are fans who like to regularly attend these shows on a monthly basis. I also observed that many of the people who came on a regular basis had some kind of connection to the female and male wrestlers themselves in the form of family or friends. This was reflected in the matches themselves because the audiences, when they know the female and male wrestlers competing, are more confident to boo, taunt the heel (villainous) female and male wrestler etc., which all adds to the atmosphere because people have fun and laugh about the insults and booing from some of the members of the audience.

Both the female and male wrestlers also played these games and used the speech to try to bait their rivals, particularly the heel female and male wrestlers who play the role of the baddies. In the case of a fight that features a storyline, the male wrestlers sometimes deliver a speech in the ring before or after their bout so that their story makes sense. In short, it is much like a dialogue that takes place between actors who are going to perform a scene. It is worth emphasising here that, to date, none of the female wrestlers who have made their debut have starred in any kind of speech. These roles have always, therefore, been played by male wrestlers.

In light of the above, my observations correspond to American style wrestling. Mexican and American freestyle wrestling are differentiated by the technique and style used in each form of wrestling. In Mexican wrestling, the movements are more agile, acrobatic, and aerial and the majority of wrestlers wear masks during appearances, whereas the American style is based more on the blows and competitor strength and it is also rare to see masked wrestlers.

It should also be noted that Revolution Championship Wrestling is committed to promoting local Spanish female wrestlers (particularly in Barcelona). They regularly attend the various shows organised by local wrestling schools to select the male and female wrestlers they want to feature on their publicity posters. In the case of Barcelona, they only attend the shows organised by the Riot Wrestling School as this is the only one that is currently active. Once there, they observe and note down relevant information to establish whether the wrestlers would fit into any of the storylines developed for their shows. The term ‘storyline’ is used in the field of wrestling to refer to the story behind each fight. This is a reminder that wrestling is an entertainment show as well as a sport, and the wrestlers form part of a dramatic spectacle which they perform through their characters.

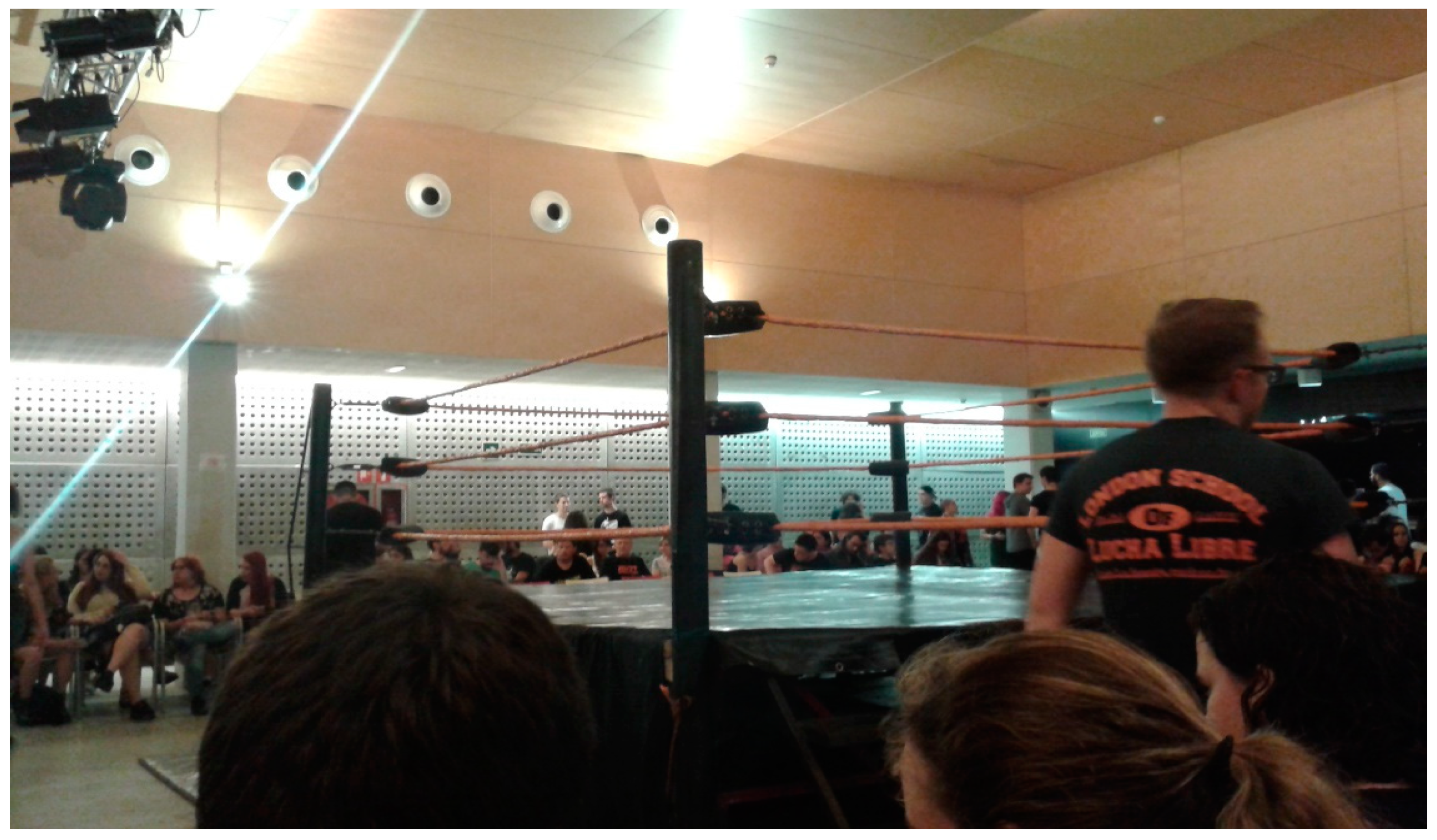

Given the above, I will now go into more detail about the schools themselves in order to provide additional context. The first one is the Spanish Pro Wrestling School10 (Figure 3) that used to be located in Hospitalet de Llobregat, with shows held at the Espai Jove la Fontana civic centre (Barcelona).

Figure 3.

This was the venue where the Spanish Pro Wrestling shows were held. It is also sometimes used as a show venue by the Riot Wrestling School. Photo by: Author.

Conversely, the Riot Wrestling School11 is located near the Clot metro station in Barcelona and its shows are held at another civic centre called Ateneu del Clot (Figure 4). Riot Wrestling also promotes a monthly wrestling show in a cocktail bar called Dixi724 (in Barcelona). Since 2014, this school has also taken part in annual events such as the Psychobilly Meeting, FanCon and the Salón del Manga, which are independent events organised in Barcelona. They use these events to publicise the school, increasing interest in becoming involved in wrestling, as well as its visibility in Barcelona.

Figure 4.

This is the venue used for the majority of the Riot Wrestling shows. Photo by: Author.

In this picture, Rinn Laree can be seen training with other members of her school. The blue mat area is used to for cardio training (1 h session). And finally, the ring area is used to practice the sport’s various moves and techniques (1 h session) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Space where both male and female wrestlers train. Photo by: Author.

As seen in the picture, she was the only female wrestler who was training on that day. The girls are not often all there, training together, at the same time. Sometimes, a few of them meet up there or they train on their own alongside the other male wrestlers at the school. The first part of the training session involved cardio exercises and, as such, she did the same as everyone else. She struggled with some of the ‘warm-up’ exercises. It is important to note that there are wrestlers, both male and female, of all levels of experience and skills at the school. That is to say, it is a small school (in terms of financial resources) as the ones with greater experience act as coaches. There are several coaches12 who come in during the week when work commitments permit, as they work elsewhere and are not paid by the school. All the female and male wrestlers pay a fee to train and take part in the shows once they are ready to get into the ring. The training sessions try to attract the maximum number of people to come together and train. As such, male and female wrestlers of all levels are able to attend, regardless of experience. This may, as first glance, be viewed as a negative factor but it becomes a genuinely rewarding experience because it benefits everyone.

Coming back to the initial point, the second part of the training session produced a number of important observations. In this part, rather than practicing and going over the moves and techniques necessary for wrestling and minimising the risk of injury, Rinn, due to her limited experience, was set different exercises to the rest of the class. This practice was also implemented for another of the male wrestlers, who was also a novice. This part of the training session consisted of getting into the ring with the other female and male wrestlers for an opportunity to practice falls and different moves. The session was led by the coach, who instructed the class on what they needed to be doing and how it should be done. Little guidance was necessary in the case of some of the more experienced male wrestlers who had already taken part in school shows and mastered the techniques. Conversely, when it came to new wrestlers, such as Rinn Laree and her classmate, it was clear that some of the exercises needed to be modified. This did not present a problem for the coach as he was familiar with their level of experience. Despite this, he made a point of encouraging them to go for it as that is the only way to get over the fear associated with trying the elements they still needed to master. However, they decided to opt for practicing another movement that they had been taught in earlier training sessions and wanted to go over again. Finally, training sessions always finish with a quick match where the female and male wrestlers are able to practice everything they have learned during the session. The objective is to apply the moves they have learned in real a match situation. The varying levels of experience among the female and male wrestlers training was not an issue here either. Those who were better in terms of technique were paired up with those who were just learning to wrestle together. This is particularly beneficial for those who are newer to the sport as it provides them with greater confidence when performing certain moves. All those training are given time in the ring to complete a match in pairs and see who wins. The roles of baddie (heel) and hero/heroine (face) are decided before the match starts, and this also represents an opportunity for the female and male wrestlers to practice performing and developing their character. It is an interesting exercise as all the other female and male wrestlers watching also get involved, shouting encouragement or booing the female and male wrestlers according to their character.

To conclude, during my observation of the training session, Rinn Laree seemed very at ease in the class and there was never any sign of any kind of discrimination, inequality, exclusion, etc. She was part of the team just like the rest of them and, in fact, the other male wrestlers went out of their way to help her as much as possible. The only thing that I would highlight is her lack of confidence with respect to trying new, more risky moves, etc., although that can be put down to a fear of picking up injuries and getting hurt, along with a lack of experience.

As part of my observations, in the past year, I have had the opportunity to analyse certain matches which featured the participation of some of the female wrestlers interviewed, as in the case of Dragonita (little dragon), as well as attending shows in which two female wrestlers (Hannah and Daphne) from Riot13 were involved as managers. The remainder of my observations have been conducted at shows organised by the two schools previously mentioned, which did not feature female competitors. Even so, this was an interesting exercise in terms of being able to get a feel for the type of audiences that attend the shows, their levels of engagement and the comments they make in relation to the show they are watching. These same points were also addressed in the shows that featured female competitors, in addition to looking at the way female wrestlers promote themselves (what kind of discourse and/or image they choose to convey to the public).

4.2. Inqualities in the Show Environment: A Lack of Opponents, Intergender Wrestling and Subsidiary Roles

Dragonita (little dragon) had been with the school the longest although she had been living in London since 2012, periodically returning to Barcelona and participating in matches almost until the school closed in 2017. Most of the matches she was involved in were against male wrestlers because there were no women to compete against. She only had the opportunity to face one other female wrestler when Amazing Montse joined the same school.

Her decision to move to another country was motivated by wrestling, because, as she told me in one interview, there was no future for her as a wrestler if she stayed in Spain. During the study, she explained that she worked as a supervisor in a supermarket and also earned money from the matches she was offered by the wrestling promoters based in England. This gave her the opportunity to take part in a number of wrestling shows, not only in the United Kingdom, but also in other countries, such as Japan, the USA, Spain, etc.

Amazing Montse then also joined the SPW school a year later, in 2014, although Dragonita (little dragon) was no longer at the school at that time because she had moved to London. As such, Amazing Montse was the only ‘permanent’ female wrestler signed up with the school. Conversely, La Penitencia (The Penance) was a female wrestler who belonged to the other wrestling school (Riot Wrestling). She was the second female wrestler at her school to make her match debut. When starting out, she was alone as the school’s most active female wrestler, as the other female member of the school (Daphne), despite having appeared in a match, had temporarily retired from the sport. When I interviewed La Penitence (The Penitence), she had been training at the school for a year. On occasion, she had competed against male wrestlers from her school, mainly because there were no other women to go up against. However, she is in favour of intergender wrestling because it allows the female wrestler to show the best ‘version’ of themselves and challenges the hegemonic approach (boys vs. boys and girls vs. girls).

It is very spectacular and I like so much the mixed wrestling matches. You know? The potential of both sides stands out. When you put in one match only girls against girls, and also, these women being inside a product in which they want to make them visible as little princesses, the only thing you see is ‘hair for here, hair for there’(LA PENITENCIA (the penance) interview, March 2016)

Her comments indicate that she does not approve of female wrestlers who put the focus on their physique and beauty rather than their technical skills when they appear in matches. This criticism is based on the references she makes to the WWE wrestling television programme. Women’s wrestling has been defined by these parameters for many years but are in contradiction to the views expressed by the group of female wrestlers interviewed for this study.

It should be noted that by 2017, two of the three female wrestlers interviewed [Amazing Montse and La Penitencia (The Penance)14] had both retired from the sport. As a result, I decided to go back to the Riot Wrestling School, where I met up with Daphne who had just begun training again. Daphne’s interest in sport started when she was very young, as someone who has done judo for many years, she decided to take a break from wrestling to focus on her judo but, drawn back by the friendships she has established and a desire to get into a ring, she has now started training again with the intention of competing. She had previously only taken part in two matches as she was unable to devote sufficient time to her training which therefore prevented her from competing in the ring. During the study, Daphne did not make her debut as a manager until the end of Riot Wrestling’s 2017 season15 of shows.

In the photographs (Figure 6 and Figure 7), we see Daphne in her first match after being away from the ring for a while. She assumed the role of manager and, as such, intervened in the match rather than wrestling herself. She and her teammates went up against another tag team in this match. Daphne played the part of the ‘heel’ (villainous character), performing actions typical of that character: distracting the referee so that her teammates could cheat, hitting the opponent without the referee seeing, bringing an object into the ring (which it is not allowed during a match) for her teammates to use and gain an advantage over the opposition.

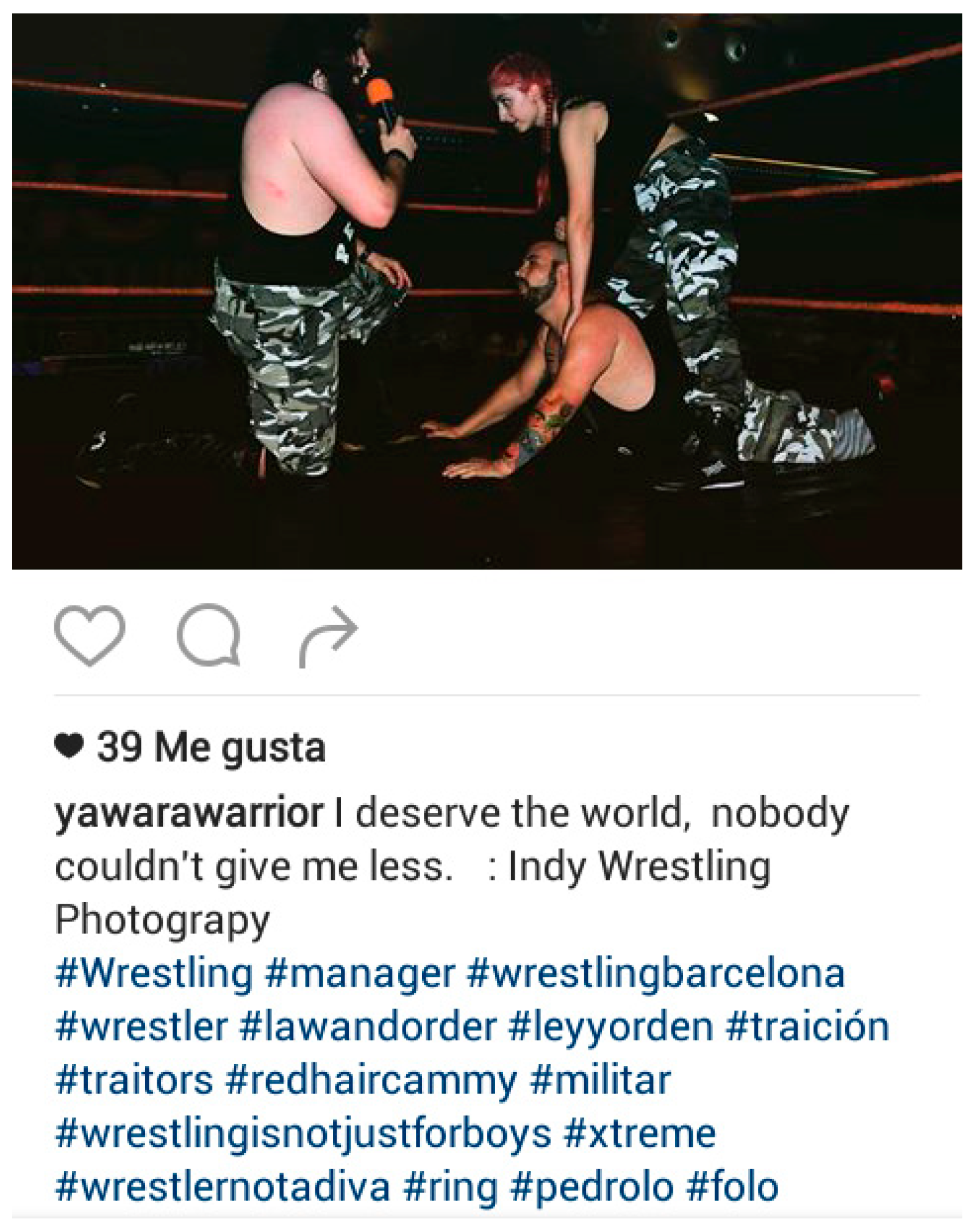

Figure 6.

Daphne participating as a manager with her team Ley and Orden (Law and Order) at the Riot Wrestling School, in a show organised by the Spanish Pro Wrestling School in 2017. Photo by: Author.

Figure 7.

Daphne participating as a manager with her team Ley and Orden (Law and Order) at the Riot Wrestling School, in a show organised by the Spanish Pro Wrestling School in 2017. Photo by: Daphne’s Instagram.

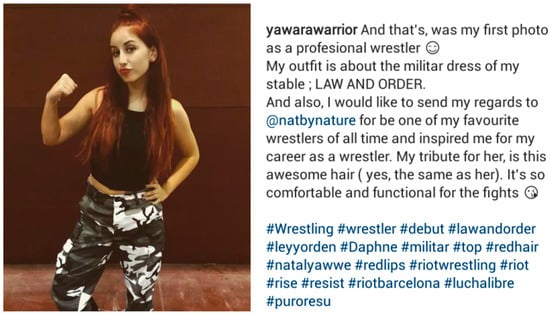

It is interesting to note the costumes worn for that match, with all members of the team dressed the same way. It was the hairstyle that Daphne had chosen that specifically caught my eye, however, as we had previously discussed her female role models from WWE (the programme responsible for introducing her to wrestling) during our interview. As a wrestling fan myself and someone who also avidly watched WWE, I am familiar with the female wrestlers that she mentioned to me in the interview and, when I saw her entering the ring, her hairstyle reminded me of the way one of those female wrestlers wore her hair during her appearances. Elements such as these demonstrate the significance of having female role models and their influence on female wrestlers in terms of their professional careers (Figure 8). On another occasion, when she was also participating as a manager in a show, she copied the hairstyle worn by her greatest female wrestling role model (Figure 9). She talked about a number of female wrestlers during the course of her interview and pointed out the elements she admires in female wrestlers, which make them role models for her. She is emphatic that she is not interested in following in the footsteps of the type of female wrestlers in WWE whose profile is based on being beautiful girls and models [7]. Although she mentioned several of her female wrestling role models, and Natalya (a female WWE wrestler) tops the bill as her greatest idol. The following photographs show Daphne’s hairstyle on the day of the show, with a picture showing her wrestling role model for comparison.

Figure 8.

Natalya (female wrestler of WWE). Photo: WWE.

Figure 9.

Daphne (a female wrestler of Riot Wrestling). Photo taken from her Instagram account.

Going back to the female wrestlers of Riot Wrestling School, Hannah made her debut in September 2017 in a show organised by her school in conjunction with FanCon (an annual alternative entertainments festival) (Figure 10). Daphne also participated in this event again, taking on the role of heel (the baddie) and was part of a team which included two other female wrestlers, called ‘Ley y Orden’ (Law and Order). Hannah, conversely, played the face (heroine) and was part of a team consisting of two other male wrestlers, Issi and Rush (although Hannah currently competes as part of a team of two with other wrestlers from her school) (Figure 11).

Figure 10.

Hannah in the role of manager with her team (Issi and Rush) in a show organized during the FanCon event. Photo by: Author.

Figure 11.

Hannah in the role of manager with her team (Issi and Rush) in a show organized during the FanCon event. Photo by: Author.

We can see from the photographs (particularly the last two) that Hannah and Daphne played a significant role in that match. Although appearing as tag team managers on this occasion, and therefore not wrestling themselves, we can see that their role was to get the audience rooting for their individual teams. As already mentioned, wrestling is a form of entertainment (despite also being a sport). As a result of this element of entertainment, some of the blows are often ‘pretend’. Wrestling is not a sport like boxing where it is all about who goes down first (due to contact). Anyone who watches wrestling understands that everything revolves around the story and what happens within that. Hence, the success of female wrestlers (both those who compete in the ring and those who act as managers) is based on connecting with the audience and winning them over. Therefore, the ‘heel’ wrestler (Daphne), for example, has to get the audience worked up, as the goal is to get them to identify with the person in the ring. So, if you are playing the part of the baddie (heel), you want to be booed and ‘hated’ because that is your role and you attack the good wrestlers (faces) [8].

To date, these two most active female members of the Riot Wrestling School (Hannah and Daphne) have not appeared in individual matches. Andrea Rose (another female wrestler of Riot Wrestling) was also going to make her debut at the above event but was subsequently forced to postpone it due to injury.

Although the formal part of my research study concluded in 2017, I have kept up with events at the Riot Wrestling School as the ultimate goal is to expand on this study in the future. I can therefore report that, as of 2018, Hannah and Daphne remain the most active female wrestlers at the school. Hannah in particular has taken part in a number of contests.

These contests have always been as part of a team, as she has not yet competed in an individual match. It should also be noted that she was the first female wrestler at Riot Wrestling to take part in a ‘Royal Rumble’ match. This is a well-known event among wrestling enthusiasts as a format introduced by the world-famous company, WWE. It is based on a match involving 3016 male and/or female wrestlers. In the case of Riot Wrestling, they opted to stage it with 20 wrestlers, of which there was just one female competitor, Hannah.

With respect to the rest of the female wrestlers, it is worth mentioning that Andrea Rose (Figure 12), Mina (Figure 13) and Rinn Laree (Figure 14) have all made their debuts as managers, although they have not wrestled in a match. Their role has been to manage an all-male tag team17 and their appearances have been sporadic.

Figure 12.

Andrea Rose in the role of manager with her team, in a show organized by her wrestling school in 2017. Photo: Víctor Castillo Blanco.

Figure 13.

Mina in the role of manager with her team (Gin West, Alpha Joe and Rex) in a show organised by her wrestling school in 2017. Photo: Ray Molinari.

Figure 14.

Rinn Laree in the role of manager with her team (Jon Hammer and Carlos Vegan) in a show organised during the Salón del Manga event. Photo by: Ray Molinari.

There have also been developments in terms of the female wrestlers’ involvement in the sport, as several of them have stopped training and therefore have not been able to appear in any matches. Following up with them, they told me that they have decided to take a break for personal reasons, although they did indicate that they intend to return. One of them, Rinn Laree, plans to return in September 2018. The others (Andrea Rose and Noemí) did not specify a particular date but expressed their wish to continue. This is an area I would like to be able to study in the future (women leaving the sport), as this has repeatedly occurred during the course of this study and I would like to carry out further research to discover the reasons why. Certainly, a number of the women I interviewed talked about the difficulties associated with their involvement in the sport. The problem is not related to the women accessing the sport itself, but rather they find that, in the end, they lack the necessary time to commit to the sport [9]. One of the issues with wrestling is that any competitor wanting to participate in one of the wrestling school shows needs to train on an ongoing basis throughout the year as it is impossible to compete against a rival in the ring without the necessary technique. This is necessary to safeguard the female wrestlers against the risk of potential injury. In order to minimise this risk, the level of commitment required in terms of time is, therefore, almost full time. That is to say, individuals need to spend a large number of hours training every week. And when, on top of that, you add the pressures of studying, work and other personal commitments, often you find that the women involved (interviewed to date) end up deciding to give up the sport due to those time constraints.

I can see this when I look at the case of two of the active female wrestlers (Hannah and Daphne) training at the school who, having already completed their studies, are now in stable employment. These women are slightly older and have completed their education, going on to find work within their area of study. They, therefore, now have the ‘security’ of only having to focus on work, rather than juggle work and studying at the same time (as in the cases of the two younger women I referred to earlier who are no longer active at the school).

The sentimental partners of these two more active Riot Wrestling female wrestlers are also involved with the school. That is, they are also male wrestlers. A factor that allows them to dovetail their commitment to the sport with their relationship, as they are both part of the same social scene and are able to spend a lot of time together. They have additionally established friendships and created bonds at the Riot Wrestling School, with the people at the centre becoming more like a family group and, therefore, the school represents a social space where the members are able to meet up with their friends. It therefore acts as a point of connection linking both sport and social interaction.

4.3. Making Sense of Experience: The Social and Cultural Construction of Gender in Wrestling

In our culture, gender is “ascribed” by a baby’s biology at birth. This biological condition forms the basis of the formulation of a social and cultural construction in relation to that individual which, in turn, defines their behaviours, tastes, practices, values:

The physical and moral characteristics, the attributes assigned to sex are based on cultural and social choices and not on a natural inclination. […] The condition of a man and woman is not inscribed in their bodily state, it is socially constructed.[10] (p. 34)

Similarly, Verena Stolcke [11] (p. 79) emphasises invention with regard to the concept of woman, expounding that everything is relegated to a social and cultural construction of gender. This is also the point De Beauvoir makes in her famous quote regarding the construction of women: “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman” [12] (p. 13). In this way, we see how the figure of the woman is conditioned on the basis of biological factors, becoming relegated to the second sex [13]. This gives rise to stratification between men and women, where social attributions are established for each gender.

Consequently, this definition of being the other sex18 implies the subordination of women to men as the dominant sex [14]. Women, for example, are credited with concepts such as weakness, fragility, inferiority but, mainly, her figure is relegated to a purely reproductive function [14] (p. 30).

However, thanks to postmodernist feminist critics (late twentieth century) who took it upon themselves to disprove these biological and physiological theories, it has been demonstrated that cultural schemas are created according to the relevant historical socio-political context [11] (p. 94).

Moreover, the author Mari Luz Esteban [15] also describes the connection between body and gender, explaining that this can act as an important agent in terms of transformational ability, as has been done with respect to the issue of the reproductive/sexual body. Since our body is based on the assimilation of social practices and their repetition, it is the result of the socio-cultural patterns established within our society.

Similarly, Judith Butler defines the gender-related term, performative, signalling that gender is made up of performative acts. Being a woman translates, then, into a performative act that is manifested in the reproductions that occur as part of everyday situations within our social lives.

In gender performativity we can observe how the norms of reality are cited and understand one of the mechanisms by which reality is produced and altered in the discourse of said reproduction.[16] (p. 308)

Moreover, due to these cultural schemas—as the authors Henrietta Moore [14] and Pierre Bourdieu [17] have demonstrated—the woman’s body is symbolised by nature and is situated in a private sphere where its participation in the public sphere is uncommon, and a sport such as wrestling, in this case, is an example of this.

The division of (sexual and other) things and activities according to the opposition between the male and female receives its objective and subjective necessity from its insertion into a system of homologous oppositions.[17] (p. 20)

4.4. Wrestling with Gender Binarisms

Everything I have discussed in the previous section involves a gender binarism that translates into being a man/woman, being male/female. Similarly, Margaret Mead [18] (p. 208) points out that these differences between men and women are found in the social practices that have been culturally constructed as part of our society.

Our culture, then, is based on classifications and gender represents another example of this. This binariness implies that each of the established genders is associated with certain behaviours that will be reproduced within the social sphere [14] (p. 30).

This naturalisation of social roles makes women vulnerable to inequality because the classification between one gender and another corresponds to differentiations by which they are branded as inferior, fragile, etc. The decision to become involved in wrestling can be a difficult one as it is not a sport which sees high levels of female participation, a factor corroborated by the observations and interviews conducted as part of this study, which confirm the limited numbers of female wrestlers involved in the sport in Barcelona. The female wrestlers interviewed gave their thoughts on this low rate of female participation.

Risk was one of the factors most frequently mentioned. Wrestling is a sport that has the potential to invoke fear from the off due to the noise of the canvas in the ring. The blows, jumps and acrobatics come thick and fast, which gives the impression of it being dangerous. Some of the wrestlers have picked up injuries before they have even made their competitive debuts and are understandably afraid of getting hurt again. They completely understand, therefore, why women may be reticent to become involved in the sport. They have even been commissioned to try to encourage other girls they know (such as friends) to get involved but those they have approached have been negative and/or rejected the idea because of the risk associated with being hit by other wrestlers. Once you enter this sporting arena, however, you realise that many of the movements which look to be very physical to the audience involve a degree of performance for the purpose of making the contest seem as real as possible.

However, if you are unaware of all the techniques associated with falling correctly and not hurting yourself, or making noises to simulate real blows, a wrestling bout can make a powerful impression. I observed an example of this during a particular show when I was sitting a few seats away from a woman aged between 60 and 70. I realised that she was a relative of one of the wrestlers taking part in the show. As soon as her son came out, she became anxious for him. She kept shouting encouragement to him during the course of the match, with sentences such as: “Come on, Morillas! You can do it! Do it for your father!” (Personal observation, cancer charity wrestling show organized by Riot Wrestling School, June 2017).

The naturalization of these social roles is, therefore, an important aspect, since it demonstrates how, from birth, gender roles and expectations are attributed to each gender. That is, when it is established that an individual is a woman, she must manifest the appropriate attitude, behaviour, values, etc., in line with that which is classified as being feminine, and the same occurs in the case of men.

Masculinity and femininity had clearly defined and differentiated characteristics. The masculine figure needed to be strong, aggressive, egotistical… whereas the feminine figure was considered fragile, weak and quiet.[19] (p. 69)

Teresa del Valle [20] (p. 8) discusses the naturalisation of gender differences. The author provides the example of girls being associated with better communication skills, which is due to internalised cultural transmission coming from the family nucleus and develops as an expectation to be fulfilled within a social context [20]. The social agents, therefore, on assuming the expectations to be met, decide to opt for one sport or another and project themselves as the norms dictate. As hegemonic models (‘femininity’ and ‘masculinity’) have been created that are reproduced by means of the way an individual acts and participates in the sport. The fact that society is based on social norms (as observed by Erving Goffman [21]) means that each individual is consequently expected to act according to their gender and, whenever that is not the case, they may be subject to stigmas and/or inequality…

Having touched on the subject of family, we should note that a number of the female wrestlers interviewed talked about their experiences with regard to telling family members they wanted to get into wrestling. The family nucleus is very important because an individual’s upbringing will have an impact on their views in relation to this sport. All the girls told me that the initial response they encountered was negative, with, in several cases, their mothers being the principle member of the family to be unsupportive of the idea of their daughters entering the sport. When the girls decided to tell their mothers they were interested in becoming involved with the sport, their immediate response was fear and anguish with regard to their daughter’s decision. The reasons given were diverse but in some cases were repeated. Some were concerned about the risks associated with the sport and were afraid their daughters would be hurt. This reflects a paternalistic discourse with a desire to protect the daughter based on the idea of her greater fragility. Specifically, in other discourses such as the following, wrestling is not seen as a sport that is suited to women’s participation:

“My family is very conventional … Andrea you have to do ballet or things like that, okay? And of course, at that time I felt very guilty because my mother said: but have you seen how they dress? I remember watching the Ninja Turtles and Power Rangers, they were my favourites and my mother would say: no, Andrea! That’s for boys!(ANDREA ROSE interview, May 2017)

The interviews conducted with the female wrestlers indicate that, in the majority of cases, the girls first discovered the world of wrestling through the US television programme (mentioned earlier), WWE. This was highly influential as it provided the women with an introduction to how the sport worked, allowed them to form connections with the male and female wrestlers they saw on the screen and developed their expectations with regard to what they want to see in a wrestling show.

The women responded to this first taste of the sport with admiration for the technical skills displayed by the competitors, spurring them on to continue watching and, in many cases, inspiring them to become involved in the sport in the future. Interestingly enough, not all of the women interviewed were sports enthusiasts before they took up wrestling. Drea, for example, told us that she had hardly played any sport at all previously but said she did not see that as a handicap because, for her, wrestling was all about self-improvement:

I saw wrestling as something that could really give me the personal challenges that I needed, apart from the exercise side that Riot is perfect for.(DREA interview, April 2017)

Returning to the subject of gender binarism, strangely enough, in sports such as athletics, martial arts and wrestling itself, traits that are considered ‘masculine’ are mixed in with the ‘femininity’ that is assigned, in this case, to the female figure. Here you enter a paradox because, if a woman projects herself in a ‘feminine’ way, she will not be accepted because that does not fit with the attributes required to participate in the sport, thus being sexually objectified or discriminated against as a result of gender stereotypes [22]. But if, conversely, she decides to project more ‘masculine’ characteristics that are demanded in a sporting context (toughness, strength…), she will be considered too ‘masculine’ and will also be stigmatised as a result of her corporal and aesthetic expression [23]. It is true that this image is being transformed by athletes seeking ‘balance’ in terms of their image, trying thus, to move away from ‘hegemonic femininity’ without completely abandoning it, thereby seeking a balance between ‘feminine’ and less ‘feminine’ characteristics.

Within women’s sport environments, females continue policing themselves, emphasizing the importance of balancing the perceptions of masculine athleticism with feminine appereance.[24] (p. 116)

It is then, when gender roles are based on hegemonic ideology regarding sexual orientation. The hegemonic discourse is related to heterosexuality and based on its cultural integration within society; it is also consequently reflected in sport, dictating that men have to be ‘masculine’ and women ‘feminine’.

American girls who want to play baseball are encouraged to play softball. The primary component of these sports is that they are offered primarily for girls and women thus ensuring they could not be considered masculine.[24] (p. 117)

Judith Butler suggests that “gender is the repeated stylization of the body, a set of repeated acts that congeal over time to create the appearance of substance, of a natural sort of being” [25] (p. 98). And certainly, as indicated by Teresa del Valle [20] (p. 7), Vikki Krane [24] and Verena Stolcke [11], the body is also subject to transformations that can be implemented through a fight scenario, in which, in this case, the female wrestlers find themselves, which can lead to them becoming empowered to change the established cultural patterns [20] (p. 7).

In spite of the continued existence of patriarchal discriminations and discourses, whether the person manifests their femininity or distances themselves from that socio-cultural definition, one aspect about our culture that is both positive and negative is that it is dynamic. There is, therefore, the potential for change and/or transformation, “The feminine and masculine identity are never fixed but subject to a continuous process of construction and, consequently, they can be redefined” [11] (p. 99).

As such, based on the field work, I can say that not everything is black or white. That is to say, the wrestlers observed did not project themselves as either ‘completely feminine’ or ‘completely masculine’. Because really, what is it to be ‘feminine’ or ‘masculine’? Are we always ‘feminine’ or, conversely, ‘masculine’? Nothing is as simple as that and our identity is composed of a diverse range of elements and/or attributes that define us and that can be contradictory to each other. Not wearing makeup, for example, does not mean that women feel less ‘feminine’. Consequently, not conforming to the idea of ‘hegemonic femininity’ when appearing in the ring may be useful in breaking down barriers and transforming the image associated with female wrestlers:

Generally, women who appear heterosexually feminine are privileged over women perceived as masculine. Consequences of nonconformity to hegemonic feminity in sport often include sexist and heterosexist discrimination. […] However, in less traditional sport settings, females are resisting, challenging, and transforming expectations of hegemonic femininity.[24] (p. 115)

4.5. Male Dominance in the Sport of Wrestling

Wrestling is a male sport because it is considered violent. This perception explains why the women’s wrestling scene is still not as active in terms of participation:

Boys are more likely to view professional wrestling matches on the televisión in part because of their desire to be socially accepted. Girls on the other hand recognise that the professional wrestling is violent and is not considered an appropriate sport for them.[26] (p. 47)

Society isn’t used to girls coming and saying: Mum, I want to be a wrestler. There aren’t many female wrestlers in wrestling in general. Here in Spain, there are only seven or eight, at the most.(CARLOS GASCÓ interview, March 2017)

Teresa del Valle [27] talks about the difficulties associated with women gaining access to areas of power as the classification of women gives us elements of inequality and differentiation generated as a result of cultural transmission.

Socialization is central in the creation of generic identities as well as the way in which content is transmitted at critical moments in the life cycle. One learns to be a woman or a man in the same way that one learns to be a girl, a teenager, a young, mature or elderly woman[27] (p. 7)

She also talks about how this inequality and gender differentiation leads to invisibility in the spheres of power. The assimilation of these unequal power relations translates into symbolic violence as this hierarchical inequality is established as a result of the established cultural schemas that are reinforced throughout our socialization (family, school, country, etc.) [17] (p. 49). That is why, as a result of specific sociocultural systems, as referred to by Xavier Medina and Ricardo Sánchez [28] (p. 7), discourses are created that are accepted throughout our process of socialization, when all this is the result of social and cultural constructions [28]. Given this, we view wrestling as a sport that is socially and culturally constructed and orientated towards the male social sector. The importance of being a man, having strength among other attributes, has resulted in the acceptance of this idea as the norm and impeded women when it comes to deciding to enter the sport, and their acceptance and visibility once involved. “Hence, when women are set on change, doing so, in the majority of cases, implies greater difficulty and effort than it does for men” [27] (p. 10).

Wrestling is a sport that involves risk, in the sense that it can lead to injury, both minor and severe, when competitors lack the necessary experience and technique. During the course of this project I have not come across any cases in which I have observed a male displaying anxiety or distress with regard to the match taking place. In ‘hardcore’ moments during a no-rules match, when a competitor was thrown onto a bed of thumbtacks placed on the canvas, some of the girls sitting in front of me were shocked and looked away when that happened. Conversely, the boy who was with them watched with excitement as it is rare to be able to see this type of match because of the level of danger.

As such, involvement in the sport implies an element of suffering (pain), although it is always avoided as far as possible to protect the health of the wrestlers. Carmen Díez [29] refers to this characteristic (suffering in sport) and the fact that it has been classified as being ‘masculine’. Consequently, a female athlete does not have the same opportunities with regard to entering and/or participating in sports because they are not considered ‘serious’ enough to be able to do so. Hence, this kind of categorisation is also found in wrestling, that translates into viewing whether a sport is suitable for men or, conversely, suitable for women [19] (p. 70).

Similarly, the author Olatz González [30] talks about the exclusion of women in sport, focusing on physical aspects in relation to the body. Sport sometimes requires physical abilities to be able to participate. These sometimes essential skills have been predominantly based on the male body due to a sociocultural construction [2]. As the male gender is oriented towards the public sphere and they are the ones that have the ‘most suitable’ attributes with regard to entering a sport [31].

Another of the discourses I have noted while attending shows is relevant for inclusion here, as it demonstrates the fact that women’s wrestling is not rated as highly as it should be. While waiting for the doors to open at the entrance to a wrestling show, I overheard a conversation between two young men expressing their opinions regarding RCW shows during which they both agreed that the reason RCW shows fail to attract large audiences is because they always feature women’s matches or, “An all-girl show. If they at least brought in some male wrestlers, then people would start coming” (Personal observation, cancer charity wrestling show organized by Riot Wrestling School, June 2017).

The fact that the contemplative body is prioritised is highly significant as it represents the central element. In this case, the prominent figure in the centre of the ring is frequently a man and, as a result, women lack relevant female role models or do not view wrestling as a sport they can be part of. The ring, therefore, becomes a scenario of values that translates into cultural transmission for boys and girls, resulting in the reaffirmation or transformation of the social and cultural constructions established with regard to gender as adults. “Thanks to this emotional disposition, sports put collective values into circulation with great efficiency and can become powerful metaphors of the societies that practice them” [30] (p. 87).

5. Wrestling as a Tool for Women’s Empowerment?

Certain public opinion discourses do not support women’s wrestling, but it should also be noted that some female wrestlers express discourses based on biological determinism with respect to whether or not they are able to participate in this sport. These discourses reinforce the idea that a woman may find it harder to participate in the sport because they are not as strong as the men. In fact, this is a concept introduced by society, which may be assimilated by girls with the result that they are discouraged from becoming involved in the sport. However, there is another side to this sport where physical differences (if they exist) become irrelevant, which is perfectly demonstrated within an intergender/mixed match, where each team member showcases their key skills in terms of technical ability:

We do not have as much strength, but we are more agile, and that has a big impact on what we can do in the ring so we will always tip the balance towards that kind of thing because it really sets us apart and benefits us.(DRAGONITA (little dragon) interview, January 2016)

Rinn Laree’s opinion with respect to mixed team matches is interesting because it shows that the wrestlers themselves are already challenging the limits that they perhaps accepted to begin with, such as the fear of injury, embarrassment about going up against men, uncertainty about being able to perform certain moves [32]. The promotion of transformational discourses such as these, exemplifying them within the wrestling school, could prove influential in bringing this sport to a wider female audience as Rinn Laree comments, “I don’t just want to compete against women because I think we can fight male wrestlers and win” (RINN LAREE interview, April 2017).

Continuing along the same lines is the case of Noemí. She says that, in her ideal scenario, she would like to do away with any differentiation between men’s and women’s events. They should be seen and understood as matches and nothing more. This is an opinion that many of the female wrestlers I interviewed also echoed. Of course, in order to reach that point, many of the discourses that I have mentioned here, which reinforce the idea that female wrestlers are unable to perform on an equal footing with men in the sport, would need to change.

Gender stereotypes still persist, however, at least among members of the public. I witnessed an example of this during a RCW show during which I noted a number of incidences of derogative behaviour from members of the audience aimed at some of the female wrestlers competing that day. One female wrestler even made a point of reproaching some of the men for their reaction to her presence in the ring. The incident in question involved a group of male friends, two of whom started wolf-whistling during the ring entrance of one of the female wrestlers, stopping once they saw that they had caught her attention. She turned quickly, and gave them a defiant look, making it clear she disapproved of their behaviour. The boys immediately stopped but the moment she turned away again, they carried on whistling.

On another occasion, another boy from the same group made a comment during a match involving two female wrestlers. The referee was obviously in the ring with the wrestlers to oversee the match. The referee in question is very well-known to the audience because he is the regular RCW match referee. At one point during the match, one of the female wrestlers had the other pinned against the canvas in a chokehold. The referee was also crouched down beside them because he had to see whether the opponent would concede. At that moment, the boy shouted out, laughing, to say: “Make the most of it Rafa! Now you can ask them for their phone numbers!” (Personal observation, wrestling show organized by Revolution Championship Wrestling, May 2017).

As such, once the time comes when there is equality in terms of opportunities, visibility and participation, it will be possible to talk about matches without needing to concern ourselves about who is playing each character. At the moment, only five of the female wrestlers have made their debut and only two of them are currently still competing. As they say, history is still to be written and, in a sense, these women are the protagonists responsible for conveying the message they want to project within the public arena. It would be unfair, however, to place all the responsibility for this on the shoulders of the female wrestlers themselves because, as indicated by the results of the study, both, participation and visibility are also clearly reliant on other external agents, such as the school itself, in terms of providing the appropriate visibility, as well as the promoters who are responsible for the organisation of the wrestling shows. This is highlighted by Carlos Gasco:

Inequality exists, but not so much from within the world itself, I mean from the wrestlers, but from the way the rest of us treat them. Or the way others treat them, that is, there is a complete inequality but it’s an issue of awareness and of not appreciating their value.(CARLOS GASCÓ interview, March 2017)

Perhaps when these female wrestlers make their debuts, that will help to break away from the type of discourse presented to date in some of the wrestling shows in Barcelona?

6. Concluding Comments

The aim of this paper was to report on some findings from an exploratory social anthropological study in the field of sport, specifically wrestling, in Barcelona, from a gender perspective. The field work and interviews conducted as part of this research project, in addition to some theoretical insights obtained from relevant bodies of literature, have led to the formation of a set of preliminary conclusions that can be summarised as follows:

Wrestling in Barcelona is not an established sport such as, for example, football and basketball. It is not well known and, indeed, there is only one school currently operating within the city.

In addition, wrestling shows are still a sexist environment and the shows still include stereotyped discourses when it comes to the staging of women’s matches and the role of wormen within mixed sex matches. I have had the opportunity to attend shows during which I have witnessed inappropriate comments being made inappropriate comments in which the female wrestler’s physical appearance (beauty or body) was highlighted rather her technical skills. There is an inherent lack of awareness in the sport, as a number of the female wrestlers and the wrestling promoter pointed out in the interviews I conducted. There is a propensity for cultural transmission regarding risk, strength, which discourages girls from entering the sporting arena. Physical cultural discourse (based on biological determinism) still prevails in this sport, which promotes male rather than female participation.

Nevertheless, and in spite of this, it was found that in the local training environment, there was equal treatment of the female wrestlers during training sessions, even though far less women trained. It is suggested that giving female wrestlers screen time (TV) and raising the profile of female wrestlers who are already active (both on a local and international level) has the potential to demonstrate that it is possible for women to compete in the ring (on an equal footing with male wrestlers), thereby opening a door and encouraging girls to follow their example, attain recognition, and demonstrate that they can gain public support and also do equally as well as a male wrestler. This point will be followed up in future work from the study that will consider the importance of having positive female wrestling role models, as it is important for the obstacle of male dominance to be removed to pave the way for gender equality in terms of participation and visibility.

A logical follow-up to this research is the importance of the role played by the media. The promotion of women’s involvement in the sport does not necessarily mean that they are being portrayed in a positive way. It is necessary to promote an egalitarian message for the audiences who watch this sport, in which women are provided the same opportunities as men, i.e., ensure that they are portrayed in the same way as their male counterparts and that their efforts and expertise in wrestling are taken equally seriously. The media needs to act as an effective tool to facilitate the transformation of these cultural schemas and thus, transform the image of women in sport, moving away from that which we have had to date (sexualised, stereotyped image and inequality).

Funding

This research received no external funding

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the female wrestlers (Ana, Andrea, Dafne, Drea, Isa, Montse, Noemí, Raquel and Stella), from the Spanish Pro Wrestling (now closed) and Riot Wrestling schools for their time and the interviews they gave me. Without their input, this work would not have been possible. I would also like to thank Iker Serrano (former wrestler), for helping to get me started by providing me with the initial contacts, and Carlos Gascó for their time, granting me an interview, providing me with information on wrestling and participating (on a small scale) in the organisation of the Revolution Championship Wrestling shows. Last (but not least), I would like to thank Professor José Enrique Agulló from the Universidad Católica in Valencia for his help at the beginning of my research, and Professor George Jennings from the Cardiff Metropolitan University for his time, support and opportunities with regard to presenting my work within the academic arena.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sisjord, M.K.; Kristiansen, E. Elite Women Wrestlers’ Muscles: Physical Strength and a Social Burden. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2009, 44, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channon, A.; Matthews, C.R. Approaching the gendered phenomenon of ‘Women Warriors’. In Global Perspectives on Women in Combat Sports; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Anguera, M.T.; Hernández, A. Avances en estudios observacionales de ciencias del deporte desde los mixed methods. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte 2016, 16, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kaberry, P.M. Aboriginal Woman Sacred and Profane; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 9780415319997. [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes, A.C.; Smith, B. Qualitative Research Methods in Sport, Exercise and Health: From Process to Product; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Niñerola, J.; Capdevila, L.; Pintanel, M. Barreras percibidas y actividad física: El autoinforme de barreras para práctica de ejercicio físico. Revista de Psicología del Deporte 2007, 15, 53–69. [Google Scholar]