Young People’s Critical Politicization in Spain in the Great Recession: A Generational Reconfiguration?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Crisis Generation: A Shared Experience

2.1. Dimensions of Generational Analysis and “the Crisis Generation”

2.2. Shared Experience of Job Insecurity and Lack of Expectations

3. Context of Youth Politicization

3.1. Political Management of the Economic and Financial Crisis

3.2. Political Corruption and Its Impact on Public Opinion

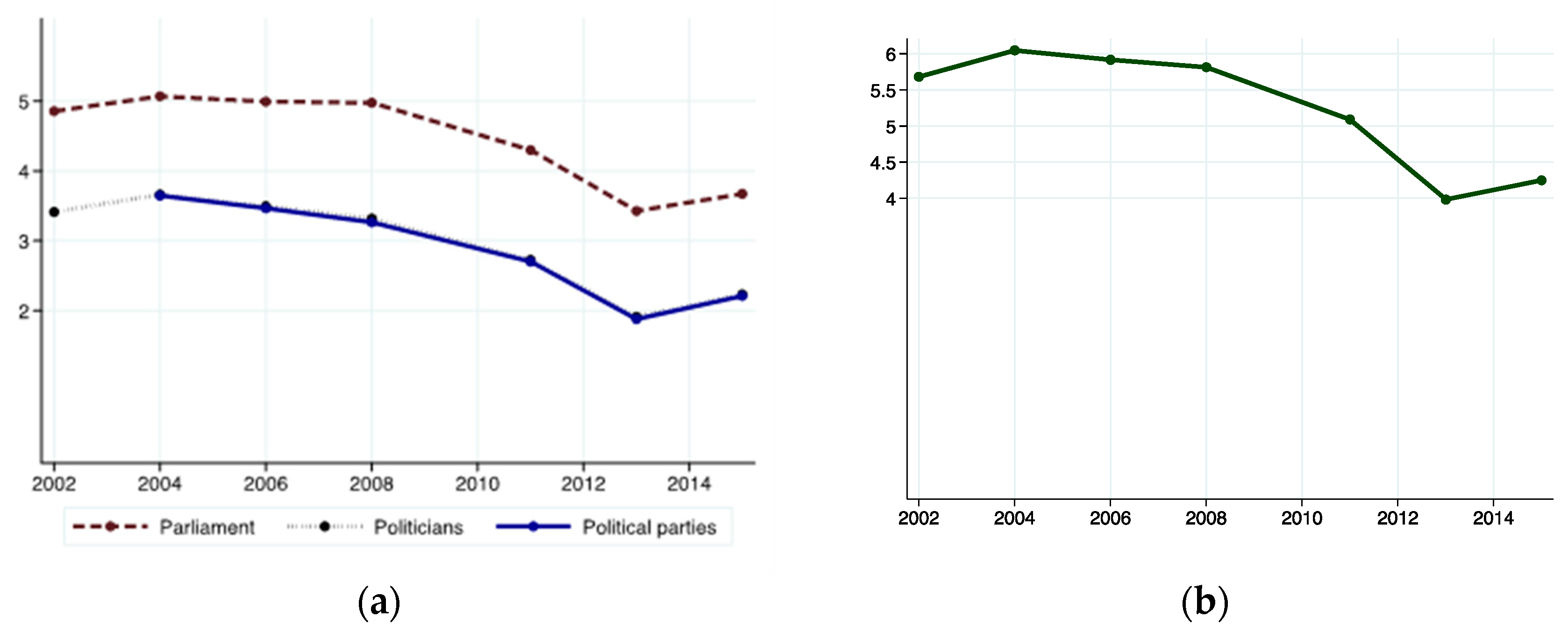

3.3. Political and Institutional Distrust on the Rise

3.4. Problems of Representation and Blockage of the Political System

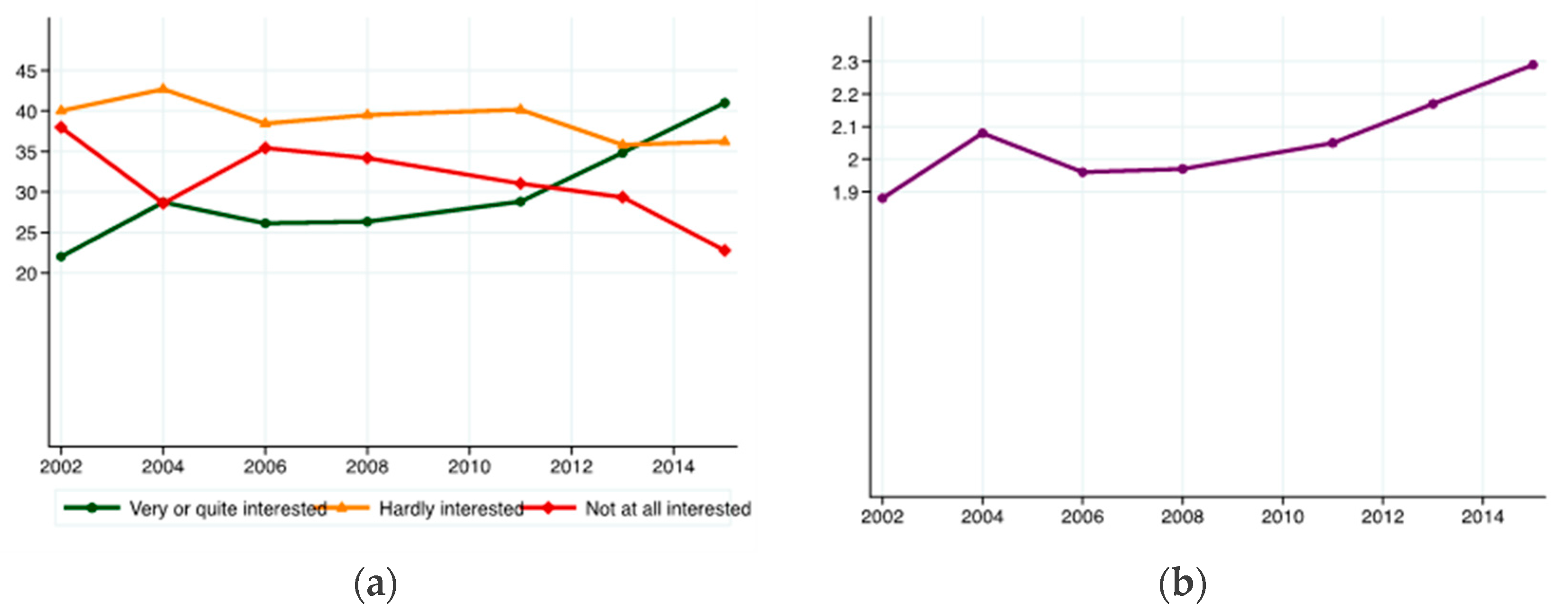

4. Youth Attitudes Towards Politics in Changing Times

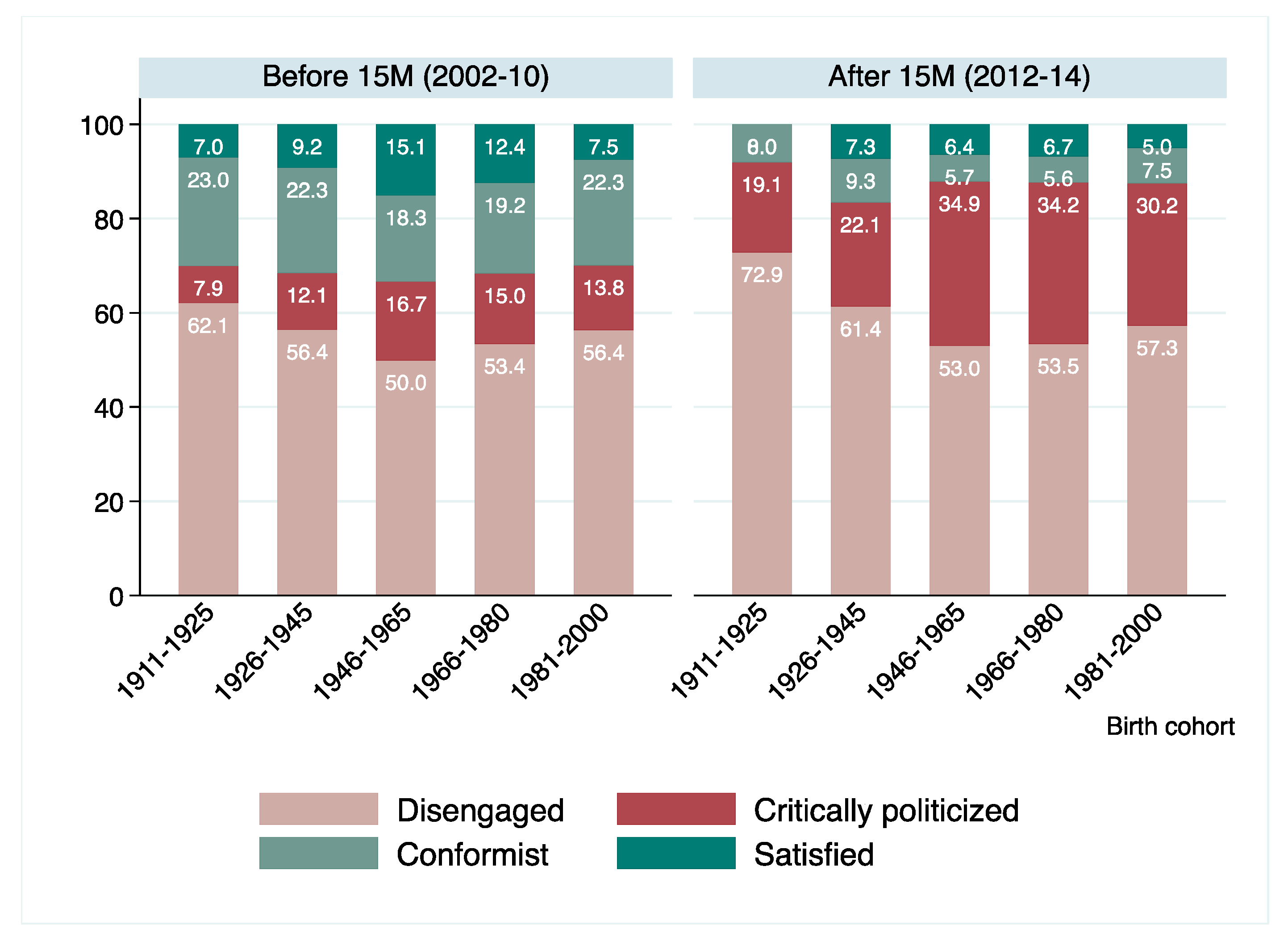

5. Research Design: Data and Methods

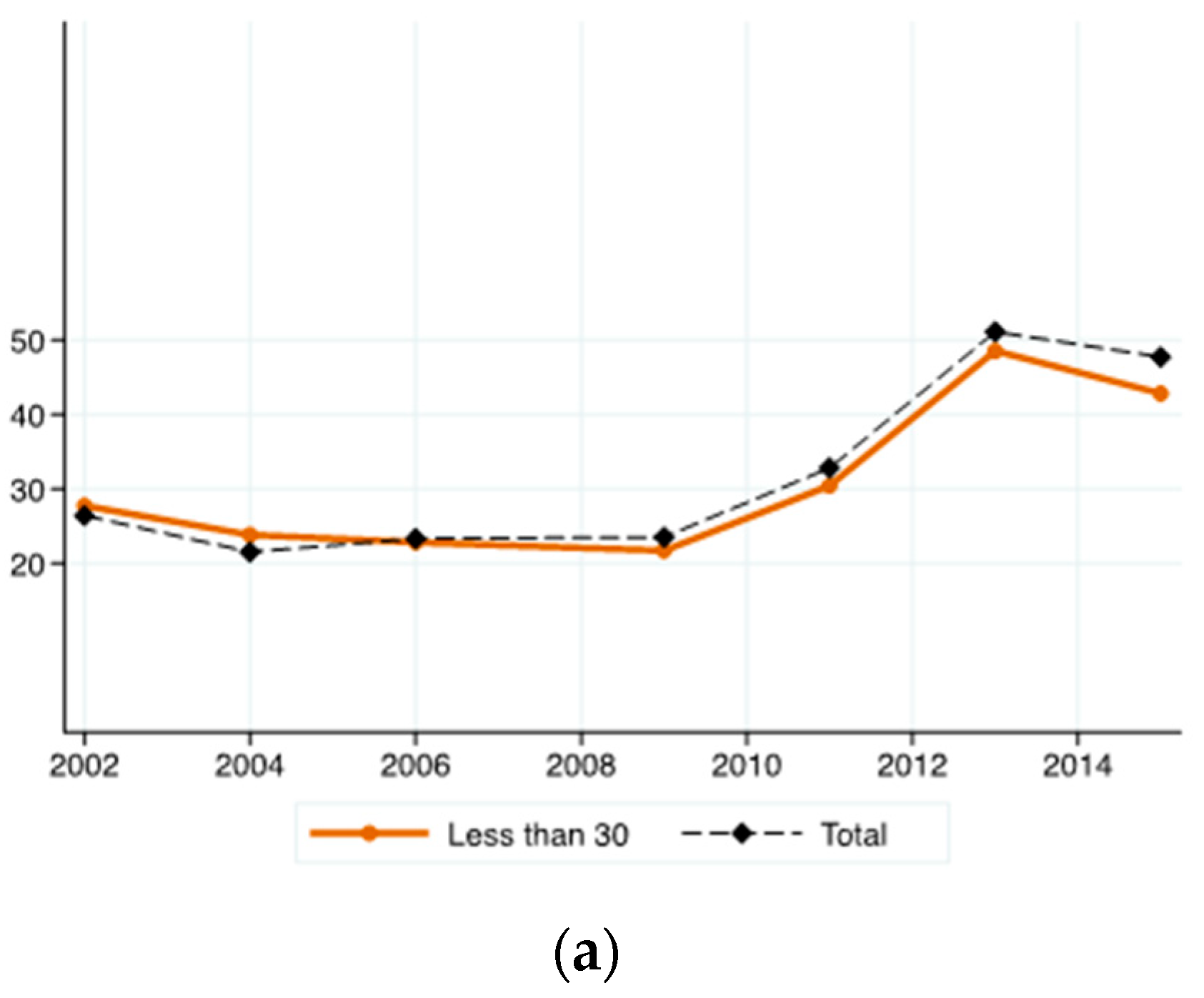

5.1. First Stage: Attidudinal Change of Young People in Spain

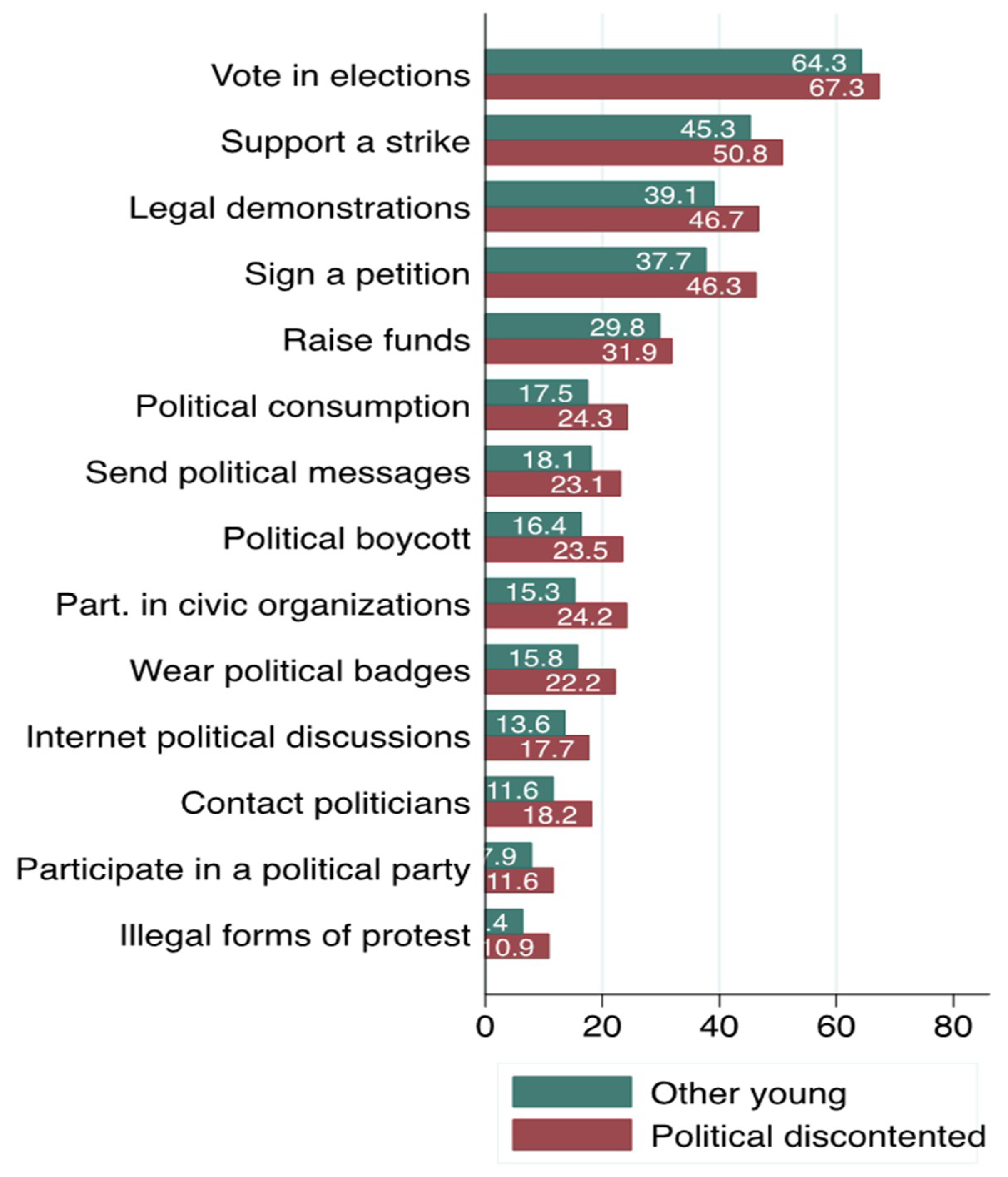

5.2. Second Stage: Analysis of the Most Discontented Youth

6. Findings

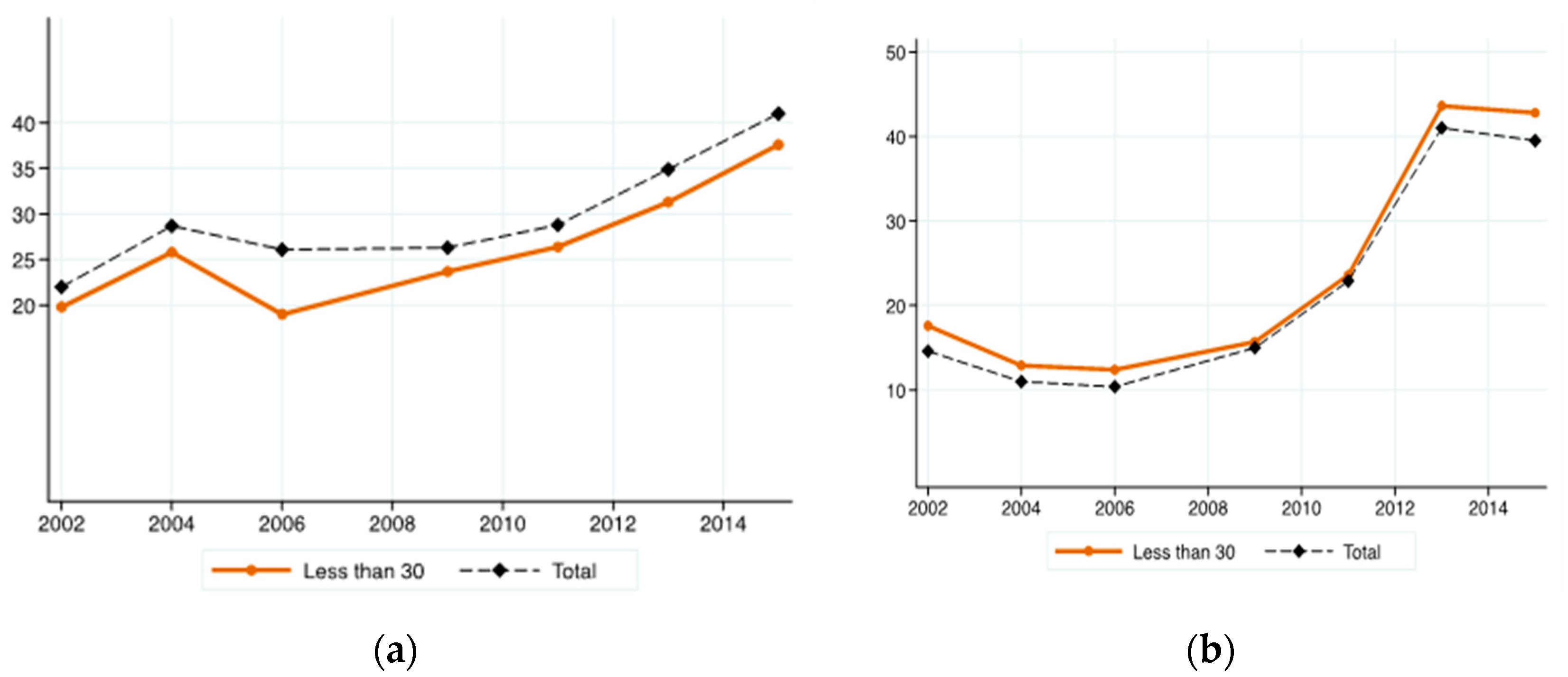

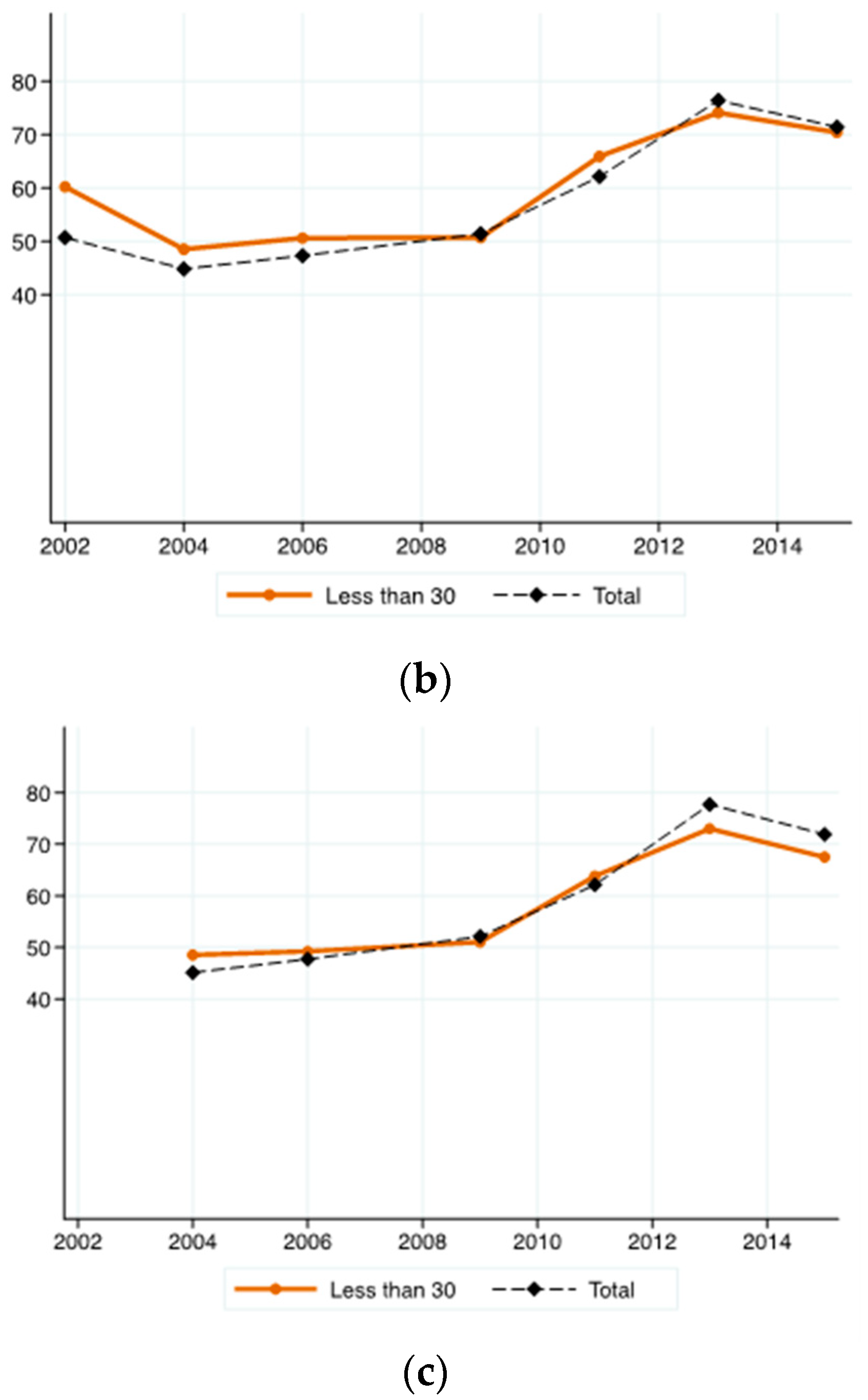

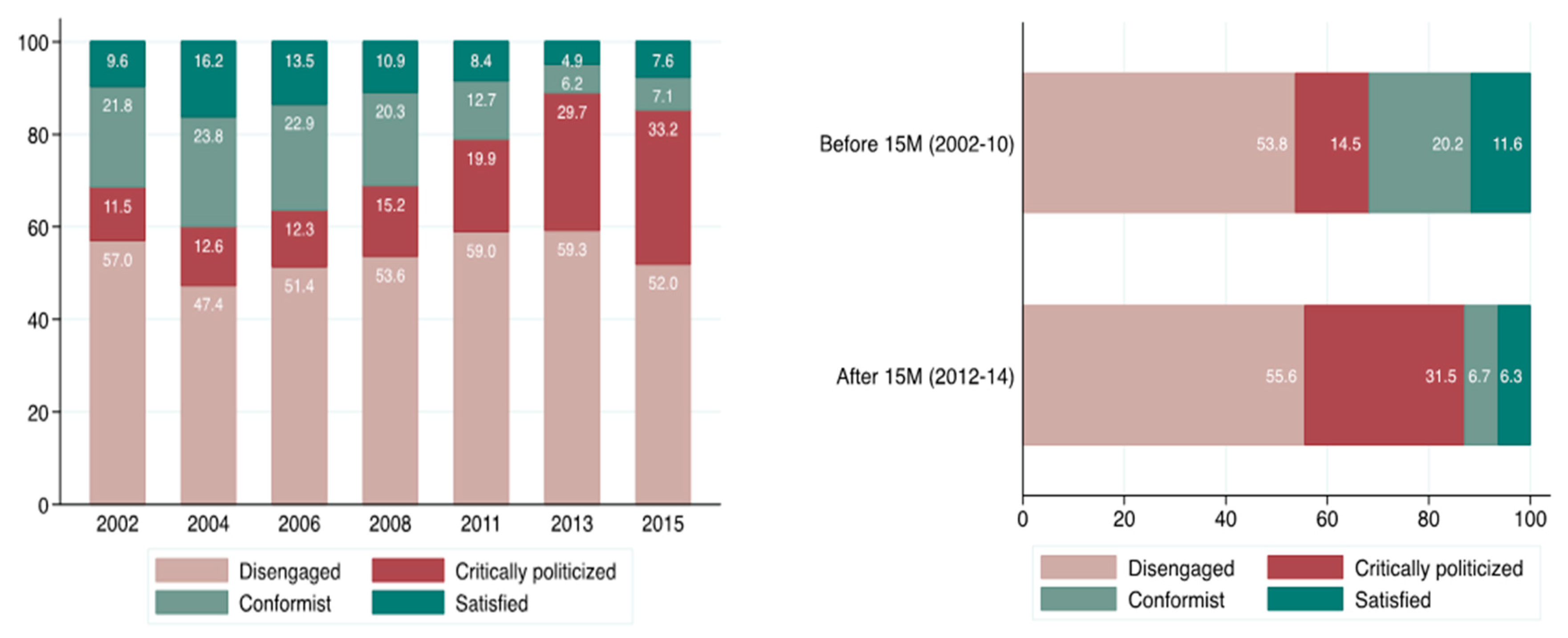

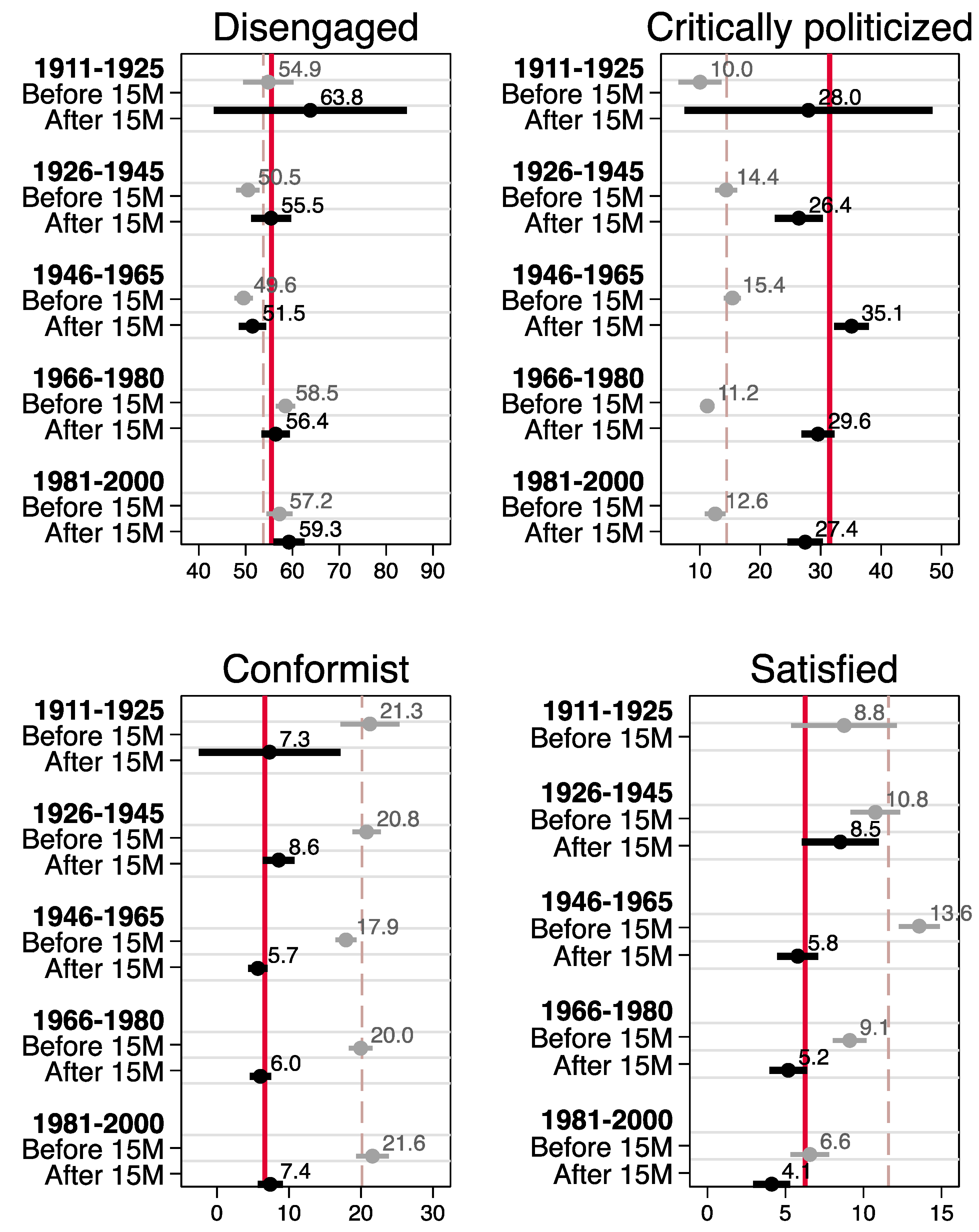

6.1. Between Disengagement and Critical Politicization

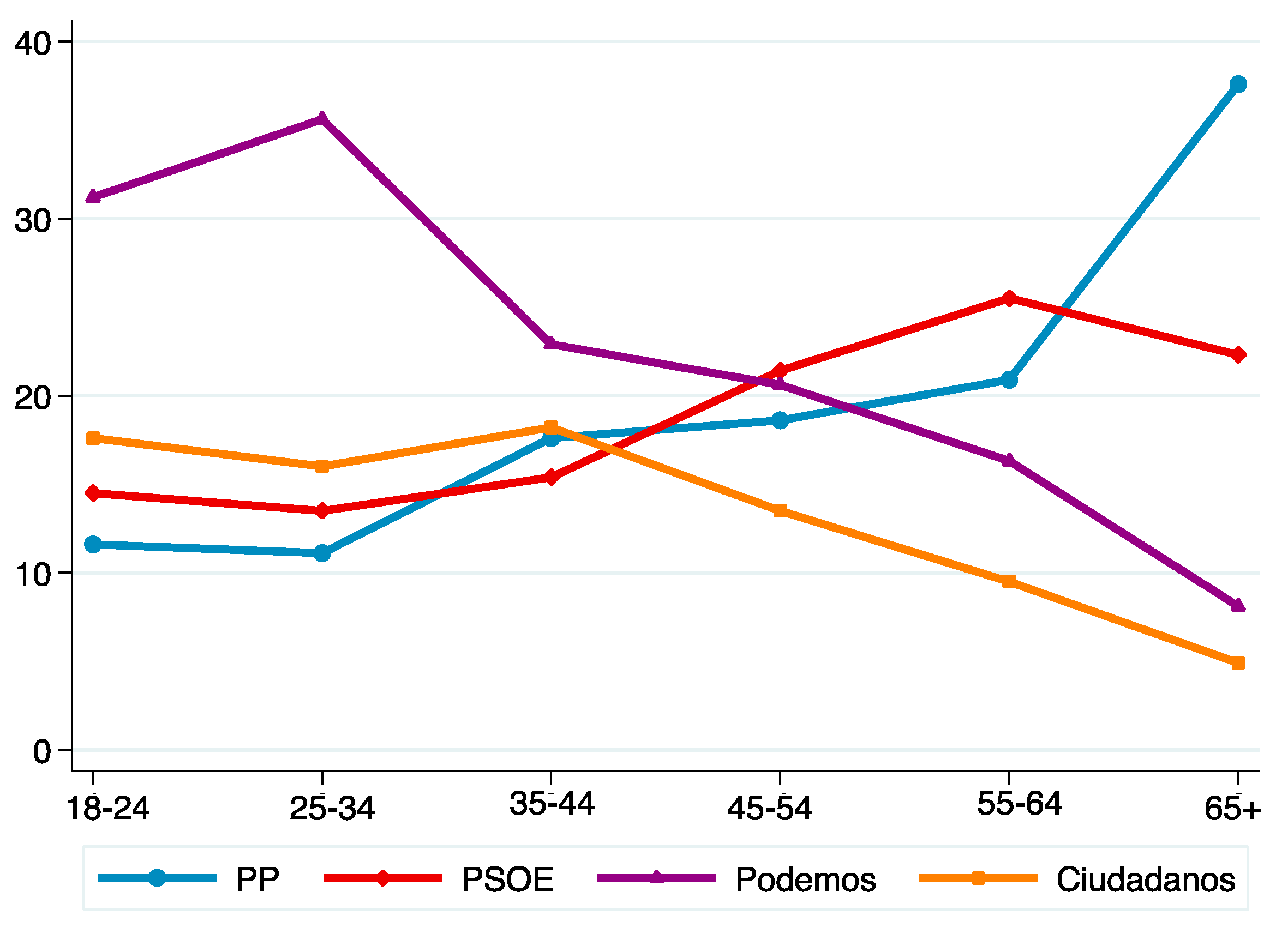

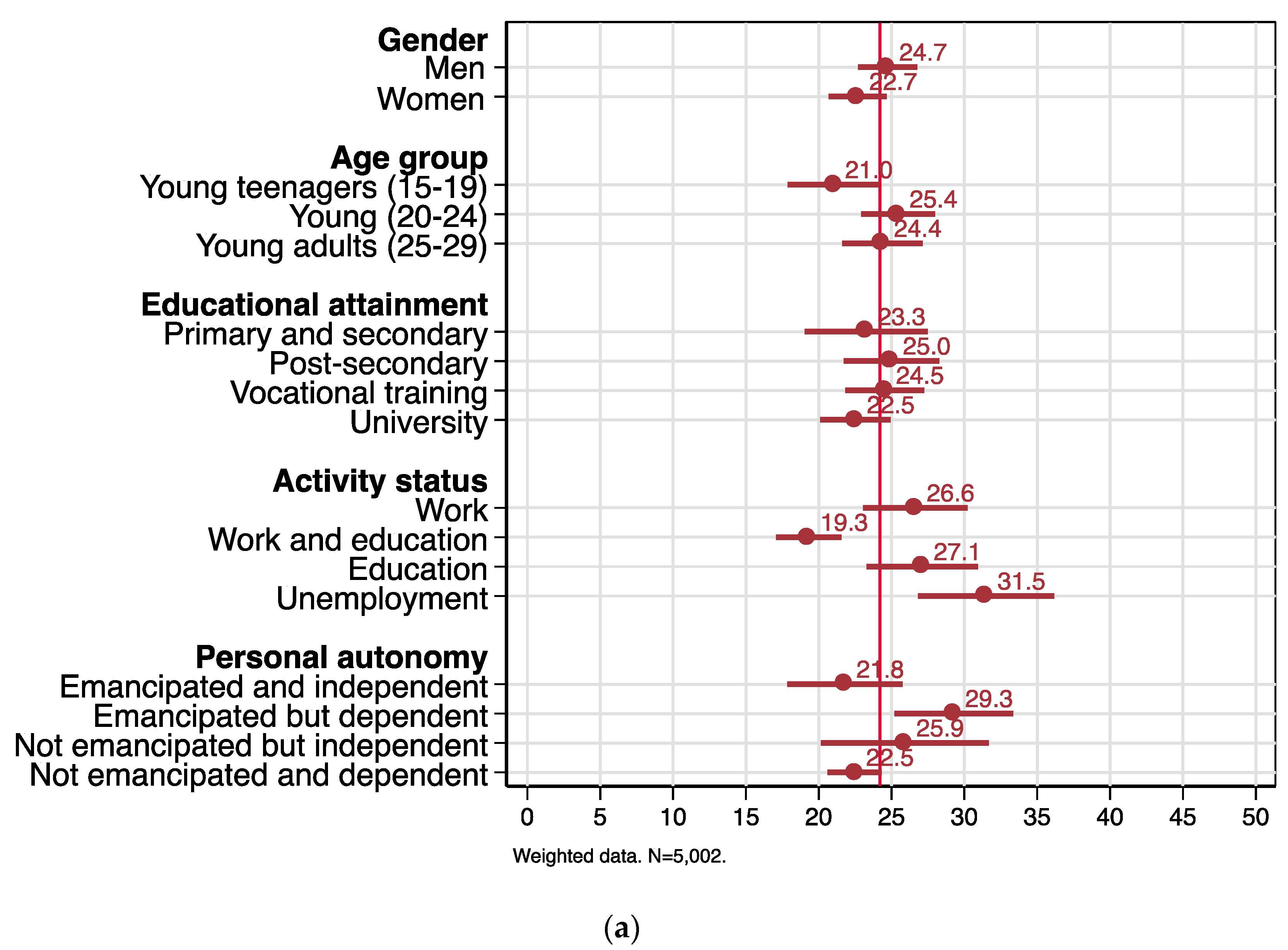

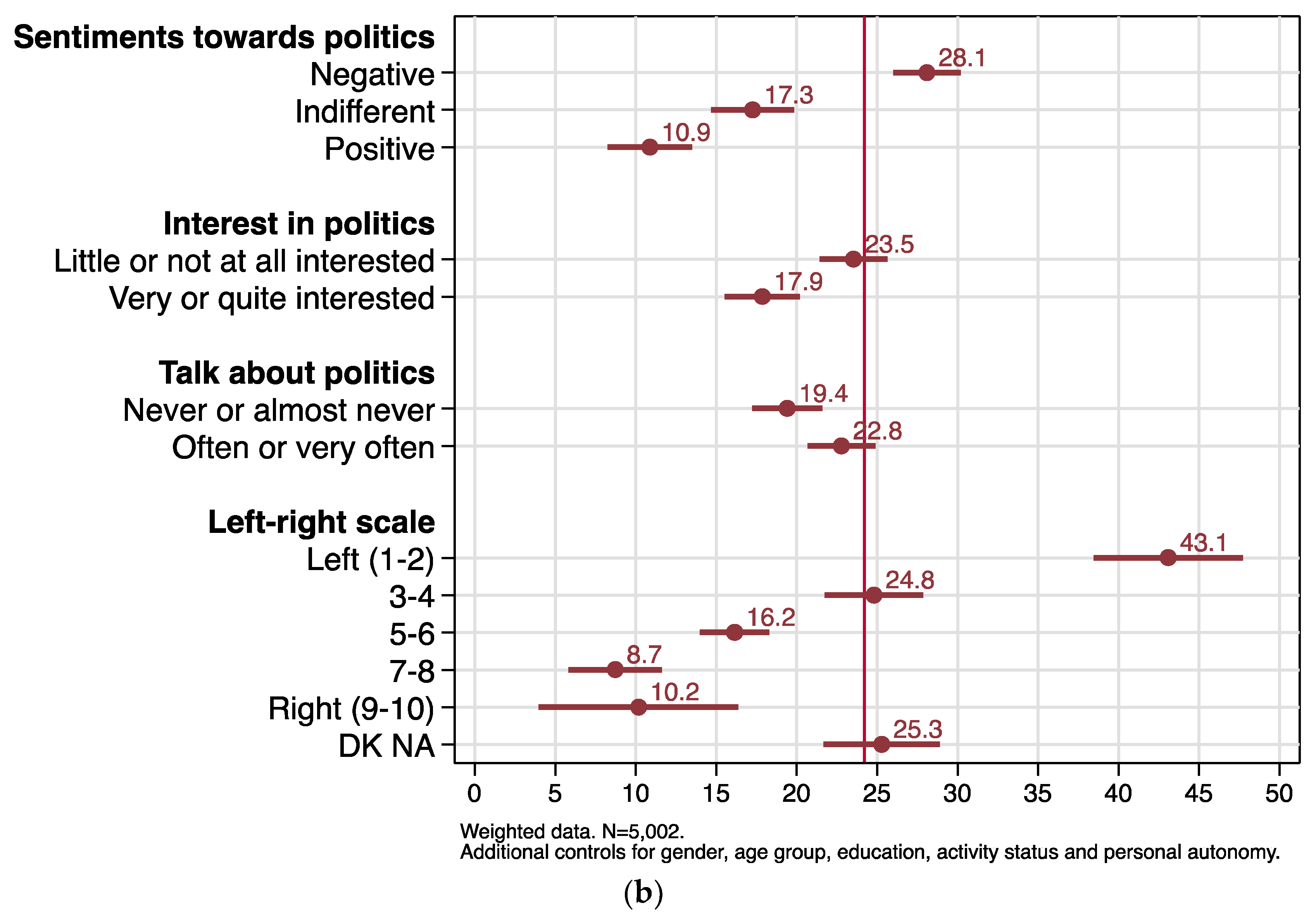

6.2. Dissatisfaction with the Political Situation: Profiles and Implications

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dimension | Variable in the Questionnaire | Categories Used to Construct the Typology |

|---|---|---|

| Regime performance: satisfaction with how democracy works | On the whole, how satisfied are you with the way democracy works in (country)? Please answer using this card, where 0 means extremely dissatisfied and 10 means extremely satisfied. The question refers to how the democratic system works ‘in practice’, as opposed to how democracy ‘ought’ to work. | Low: 0–5 or DK/NA High: 6–10 |

| Regime institutions: trust in national Parliament | Please tell me on a score of 0–10 how much you personally trust each of the institutions I read out. 0 means you do not trust

an institution at all, and 10 means you have complete trust. - …(country)’s Spanish Parliament | Low: average score ranging between 0 to 4, or DK/NA in the three variables * High: Average score higher than 4 * |

| Political actors: trust in politicians and political parties | Please tell me on a score of 0–10 how much you personally trust each of the institutions I read out. 0 means you do not trust

an institution at all, and 10 means you have complete trust. - …politicians? - … political parties? | |

| Interest in politics | How interested would you say you are in politics? Are you … (read out) … very interested, quite interested, hardly interested, or not at all interested? (Don’t know). | Low: hardly interested, not at all interested in politics or DK/NA High: very or quite interested in politics |

Appendix B

| ESS Round (Fieldwork) | Less Than 30 | 30–44 | 45–59 | 60 and More | Total (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESS 1 (2002) | 18.7 | 28.7 | 19.3 | 33.3 | 100% (1717) |

| ESS 2 (2004) | 24.3 | 29.6 | 21.4 | 24.8 | 100% (1640) |

| ESS 3 (2006) | 23.6 | 28.1 | 22.4 | 25.9 | 100% (1876) |

| ESS 4 (2008) | 21.8 | 28.6 | 21.3 | 28.3 | 100% (2572) |

| ESS 5 (2011) | 21.1 | 29.5 | 25.5 | 23.9 | 100% (1880) |

| ESS 6 (2013) | 16.8 | 30.3 | 25.2 | 27.7 | 100% (1888) |

| ESS 7 (2015) | 17.7 | 26.0 | 27.6 | 28.7 | 100% (1925) |

| Total | 20.6 | 28.7 | 23.3 | 27.5 | 100% (13,498) |

| ESS Round (Fieldwork) | (1911–1925) | (1926–1945) | (1946–1965) | (1966–1980) | (1981–2000) | Total (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESS 1 (2002) | 8.3 | 28.3 | 31.4 | 24.2 | 7.9 | 100% (1717) |

| ESS 2 (2004) | 4.6 | 21.2 | 31.7 | 29.7 | 12.8 | 100% (1640) |

| ESS 3 (2006) | 4.5 | 20.3 | 31.0 | 28.8 | 15.5 | 100% (1876) |

| ESS 4 (2008) | 3.2 | 20.6 | 29.2 | 28.9 | 18.0 | 100% (2572) |

| ESS 5 (2011) | 1.7 | 15.1 | 30.2 | 30.2 | 22.9 | 100% (1880) |

| ESS 6 (2013) | 0.9 | 15.2 | 31.1 | 30.3 | 22.5 | 100% (1888) |

| ESS 7 (2015) | 0.5 | 15.3 | 30.3 | 28.0 | 25.9 | 100% (1925) |

| Total | 3.3 | 19.3 | 30.6 | 28.6 | 18.2 | 100% (13,498) |

Appendix C

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disengaged | Critically Politicized | Conformist | Satisfied | |

| Birth cohort (ref. 1911–1925, greatest generation) | ||||

| 1926–1946 (silent generation) | 0.84 | 1.504 * | 0.973 | 1.256 |

| [0.101] | [0.321] | [0.133] | [0.290] | |

| 1946–1965 (baby boomers) | 0.809 * | 1.632 ** | 0.809 | 1.635 ** |

| [0.0953] | [0.341] | [0.109] | [0.367] | |

| 1966–1980 (generation X) | 1.162 | 1.135 | 0.925 | 1.045 |

| [0.140] | [0.239] | [0.127] | [0.238] | |

| 1981–2000 (millennials) | 1.102 | 1.286 | 1.021 | 0.732 |

| [0.138] | [0.279] | [0.145] | [0.176] | |

| Time (ref. Before 15-M) | ||||

| After 15-M (2011–2015) | 1.452 | 3.479 ** | 0.292 | 0.612 *** |

| [0.679] | [1.936] | [0.219] | [0.112] | |

| Birth cohort * Time | ||||

| 1926–1945 * After 15-M | 0.84 | 0.614 | 1.225 | 1.26 |

| [0.402] | [0.350] | [0.939] | [0.324] | |

| 1946–1965 * After 15-M | 0.743 | 0.854 | 0.945 | 0.640 ** |

| [0.352] | [0.480] | [0.721] | [0.145] | |

| 1966–1980 * After 15-M | 0.632 | 0.952 | 0.883 | 0.891 |

| [0.300] | [0.536] | [0.675] | [0.203] | |

| 1981–2000 * After 15-M | 0.749 | 0.757 | 0.994 | |

| [0.357] | [0.429] | [0.760] | ||

| Gender (ref. Men) | 1.495 *** | 0.622 *** | 1.145 *** | 0.609 *** |

| [0.0563] | [0.0300] | [0.0577] | [0.0376] | |

| Economic difficulties at household (ref. Good economic situation) | 1.453 *** | 0.96 | 0.616 *** | 0.731 *** |

| [0.0678] | [0.0588] | [0.0418] | [0.0645] | |

| Educational attainment (ref. basic education) | ||||

| Upper secondary education | 0.561 *** | 2.138 *** | 0.805 *** | 2.067 *** |

| [0.0270] | [0.132] | [0.0526] | [0.165] | |

| Tertiary education | 0.325 *** | 3.448 *** | 0.652 *** | 3.347 *** |

| [0.0178] | [0.220] | [0.0505] | [0.262] | |

| Observations | 13,314 | 13,314 | 13,314 | 13,314 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (ref. Male) | 0.893 | 0.768 *** |

| [0.0723] | [0.0654] | |

| Age (ref. Young teenagers, 15–19 years old) | ||

| Young, 20–24 years old | 1.283 ** | 1.347 ** |

| [0.154] | [0.167] | |

| Young adults, 25–29 years old | 1.211 | 1.273* |

| [0.169] | [0.182] | |

| Educational attainment (ref. Primary and secondary) | ||

| Postsecondary | 1.099 | 1.122 |

| [0.159] | [0.170] | |

| Vocational training | 1.072 | 1.026 |

| [0.152] | [0.154] | |

| University | 0.959 | 1.034 |

| [0.139] | [0.161] | |

| Activity status (ref. Work only) | ||

| Work and education | 0.660 *** | 0.727 ** |

| [0.0889] | [0.102] | |

| Education | 1.025 | 0.958 |

| [0.142] | [0.141] | |

| Unemployment | 1.268 * | 1.318 * |

| [0.174] | [0.188] | |

| Economic independence (ref. Emancipated and independent) Emancipated but dependent | 1.485 *** | 1.435 ** |

| [0.220] | [0.224] | |

| Not emancipated but independent | 1.255 | 1.395 * |

| [0.221] | [0.263] | |

| Not emancipated and independent | 1.040 | 1.068 |

| [0.143] | [0.157] | |

| Sentiments towards politics (ref. Negative) | ||

| Indifferent | 0.535 *** | |

| [0.0560] | ||

| Positive | 0.312 *** | |

| [0.0455] | ||

| Interest in politics (ref. little or not at all interested) Very or quite interested in politics | 0.704 *** | |

| [0.0756] | ||

| Talk about politics (ref. Never or almost never) Often or very often | 1.232 ** | |

| [0.120] | ||

| Left–right ideological scale (ref. Left, 1–2) 3–4 | 0.441 *** | |

| [0.0557] | ||

| 5–6 | 0.253 *** | |

| [0.0321] | ||

| 7–8 | 0.127 *** | |

| [0.0267] | ||

| Right (9–10) | 0.151 *** | |

| [0.0542] | ||

| DK NA | 0.455 *** | |

| [0.0652] | ||

| Constant | 0.324 *** | 1.289 |

| [0.0725] | [0.339] | |

| Observations | 5002 | 5002 |

References

- El Muro Invisible. Las Dificultades de ser Joven en España; Debate; Politikon: Madrid, Spain, 2017.

- Benedicto, J. Informe Juventud en España. 2016. Available online: http://www.injuve.es/sites/default/files/2017/24/publicaciones/informe-juventud-2016.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2018).

- Prior, M. You’ve Either Got It or You Don’t? The Stability of Political Interest over the Life Cycle. J. Politics 2010, 72, 747–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neundorf, A.; Smets, K.; García, A.G. Homemade Citizens: The Development of Political Interest during Adolescence and Young Adulthood; SOEP Papers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research No. 693; Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW): Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, L.; Jackman, S. A generational model of political learning. Elect. Stud. 2014, 33, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K. Concepts of Bounded Agency in Education, Work and the Personal Lives of Young Adults. Int. J. Psychol. 2007, 42, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, W. Youth transitions in an age of uncertainty. In Handbook of Youth and Young Adulthood; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Woodman, D.; Wyn, J. Youth and Generation: Rethinking Change and Inequality in the Lives of Young People; Sage: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mannheim, K. The problem of generations. In Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge; Kecskemeti, P., Ed.; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1952; pp. 276–320. [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds, J.; Turner, B. (Eds.) Generational Consciousness, Narrative and Politics; Rowman & Littlefield Pub.: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Delli, C.M.X. Age and history: Generations and sociopolitical change. In Political Learning in Adulthood; Sigel, R.S., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989; pp. 11–55. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, J.; O’Connor, H. Youth and Generation: In the middle of an adult world. In Handbook of Youth and Young Adulthood. New Perspectives and Agendas; Furlong, A., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Furlong, A.; Cartmel, F. Young People and Social Change; Open Univ. Press: Buckingham, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fondeville, N.; Ward, T. Scarring Effects of the Crisis; Research Note 06/2014; Commission European: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano, P.; Spilimbergo, A. Growing up in a Recession. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2014, 81, 787–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortino, S.; Tejerina, B.; Cavia, B.; Calderón, J. Crise Sociale et Précarité; Champ Social: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Côté, J. Towards a new political economy of youth. J. Youth Stud. 2014, 17, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedicto, J.; Fernandez, L.; Gutierrez, M.; Martín, E.; Morán, M.L.; Perez, A. Transitar a la Intemperie. Jóvenes en Busca de Integración; INJUVE: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de Mosteyrín, L.; Morán, M.L. Buscando un lugar en el mundo. Los imaginarios juveniles de futuro en tiempos de crisis. Mélanges Casa Velázquez 2017, 47, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feixa, C.; Rubio, C.; Ganau, J.; Solsona, F. (Eds.) Emigració Juvenil, Moviments Socials i Xarxes Digitals; L’Emigrant 2.0.; Departament de Treball, Afers Socials i Famílies, Direcció General de Joventut: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinaga, J.; Comas, D. La Juventud Española. El Imaginario de la Transición Permanente; En VVAA Informe España 2015; Fundación Encuentro: Madrid, Spain, 2015; pp. 33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Benedicto, J.; Morán, M.L. De la Integración Adaptativa al Bloqueo en Tiempos de Crisis: Preocupaciones y Demandas de los Jóvenes; Morán, M.L., Ed.; Actores y Demandas en España; Análisis de un Inicio de Siglo convulse; Los Libros de la Catarata: Madrid, Spain, 2013; pp. 56–80. [Google Scholar]

- Perugorría, I.; Tejerina, B. Politics of the encounter: Cognition, emotions, and networks in the Spanish 15M. Curr. Sociol. 2013, 61, 424–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, N. Young people took to the streets and all of a sudden all of the political parties got old: The 15M movement in Spain. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2011, 10, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamponi, L.; Bossi, L. Which Crisis? European Crisis and National Contexts in Public Discourse. Politics Policy 2016, 44, 400–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanos, E. Collective Learning Processes within Social Movements: Some Insights into the Spanish 15M Movement, in Laurence Cox y Cristina Flesher Fominaya. In Understanding European Movements; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor, J. El 15M, Las Mareas y su Relación con la Política Sistémica. El Caso de Madrid. Anuario Conflicto Social 2013. Available online: http://revistes.ub.edu/index.php/ACS/article/view/10391/13173 (accessed on 14 June 2018).

- Polavieja, P. Economic Crisis, Quality of Work and Social Integration: The European Experience. In Economic Crisis, Political Legitimacy, and Social Cohesion; Duncan, G., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 256–278. [Google Scholar]

- Colloca, P. The Hopeless Forecast under the Gloomy Sky. Crisis of Political Legitimacy and Role of Future Perspective in Hard Times. Partecip. Conflitto 2018, 10, 983–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Villaverde, J.; Garicano, L.; Santos, T. Political Credit Cycles: The Case of the Eurozone. J. Econ. Perspect. 2013, 27, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, F. Building Boom and Political Corruption in Spain. South Eur. Soc. Politics 2009, 14, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villoria, M.; Jiménez, F. La corrupción en España (2004–2010): Datos, percepción y efectos. Rev. Esp. Investig. Sociol. 2012, 138, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villoria, M.; Jimenez, F. Cuánta corrupción hay en España? Los problemas metodológicos de la medición de corrupción (2004–2011). Rev. Inst. Eur. 2012, 156, 13–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lapuente, V. La Corrupción en España: Un Paseo por el Lado Oscuro de la Democracia y el Gobierno; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, L. From Recession to Long-Lasting Political Crisis? Continuities and Changes in Spanish Politics in Times of Crisis and Austerity; Working Papers 334; Institut de Ciències Polítiques i Socials Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, F. Los efectos de la corrupción sobre la desafección y el cambio político en España. Revista Internacional de Transparencia e Integridad 2017, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Maravall, J.M. Los Resultados de la Democracia: Un Estudio del sur y el este de Europa; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Morán, M.L.; Benedicto, J. La Cultura Política de los Españoles. Un Ensayo de Reinterpretación; Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas: Madrid, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Galais, C. Cada vez más apáticos? El desinterés político juvenil en España en perspectiva comparada. Rev. Int. Sociol. 2012, 70, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedicto, J. Cultural structures and political life: The cultural matrix of democracy in Spain. Eur. J. Political Res. 2004, 43, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torcal, M. The Decline of Political Trust in Spain and Portugal: Economic Performance or Political Responsiveness? Am. Behav. Sci. 2014, 58, 1542–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, G. Challenging business as usual? The rise of new parties in Spain in times of crisis. West Eur. Politics 2018, 41, 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orriols, L.; Cordero, G. The breakdown of the Spanish two-party system: The upsurge of Podemos and Ciudadanos in the 2015 general election. South Eur. Soc. Politics 2016, 21, 469–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Albacete, G.; Lorente, J.; Martín, I. How does the Spanish ‘crisis generation’ relate to politics? In Political Engagement of the Young in Europe. Youth in the Crucible; Thijssen, P., Siongers, J., van Laer, J., Haers, J., Mels, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 50–71. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, P. (Ed.) Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, G.; Montero, J.R. Against Bipartyism, Towards Dealignment? The 2014 European Election in Spain. South Eur. Soc. Politics 2015, 20, 357–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.J.; Bouza, F. Las Razones del Voto en la España Democrática 1977–2008; Libros La Catarata: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, M.; Simón, P. Qué Pueden Cambiar Podemos y Ciudadanos en el Sistema de Partidos? Zoom Politico 2015/27; Fundacion Alternativas: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lavezzolo, S.; Ramiro, L. Stealth democracy and the support for new and challenger parties. Eur. Political Sci. Rev. 2018, 10, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, P. The challenges of the new Spanish multipartism: Government formation failure and the 2016 general election. South Eur. Soc. Politics 2016, 21, 493–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, K.; Gómez-Pastrana, T.; Mena, L. Movimiento 15M: ¿quiénes son y qué reivindican? Zoom Político 2011, 4, 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- García, F.J.F.; Fernández, O.A.S. Crisis politica y juventud en España: El declive del bipartidismo electoral. SocietàMutamentoPolitica 2014, 5, 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, D.; O’Toole, T.; Jones, S. Young People and Politics in the UK: Apathy or Alienation? Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, R. Disgruntled, Disillusioned and Disengaged. Public Attitudes to Politics in Britain Today. Parliam. Aff. 2012, 65, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, M.; Foard, N. Young People, Political Participation and Trust in Britain. Parliam. Aff. 2012, 65, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghe, M.; Boonen, B. Youth engagement in politics. Generational differences and participation inequalities. In Political Engagement of the Young in Europe. Youth in the Crucible; Thijssen, P., Siongers, J., van Laer, J., Haers, J., Mels, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps, E. Understanding Electoral Turnout among British Young People: A Review of the Literature. Parliam. Aff. 2012, 65, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, H. Ben Oldfield: Cajoling or coercing: Would electoral engineering resolve the young citizen–state disconnect? J. Youth Stud. 2016, 19, 1259–1280. [Google Scholar]

- Benedicto, J.; Morán, M.L. La construcción de los imaginarios colectivos sobre jóvenes, participación y política en España. Rev. Estud. Juv. 2015, 110, 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Easton, D. A Reassessment of the Concept of Political Support. Br. J. Political Sci. 1975, 5, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, F.; Tomlinson, D. International Comparisons of Intergenerational Trends; Resolution Foundation: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, M. Jóvenes, participación y actitudes políticas en España, ¿son realmente tan diferentes? Rev. Estud. Juv. 2006, 75, 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Armingeon, K.; Guthmann, K. Democracy in crisis? The declining support for national democracy in European countries 2007–2011. Eur. J. Political Res. 2014, 53, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundación, A. El Descontento con el Funcionamiento de la Democracia en España; Informe sobre la Democracia en España 2015; Reformular la política; Fundación Alternativas: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro, B.; Sánchez-Cuenca, I. In the whirlwind of the economic crisis: Local and regional elections in Spain, May 2011. South Eu. Soc. Politics 2012, 17, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, J.R.; Gunther, R.; Torcal, M. Democracy in Spain: Legitimacy, discontent, and disaffection. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 1997, 32, 124–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambor, T.; Clark, W.R.; Golder, M. Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Anal. 2005, 14, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrys, A.; Wyn, J.; Younes, S. Beyond apathetic or activist youth. ‘Ordinary’ young people and contemporary forms of participation. Young 2010, 18, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, T. Beyond Crisis Narratives: Changing modes and repertoires of political participation among young people. In Geographies of Politics, Citizenship and Right: Children and Young People as Participants in Politics; Skelton, T., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The 15-M Movement (‘Movimiento 15-M’ in Spanish), also known as the Indignados Movement, stands for 15 May, the 2011 date when the first large demonstration took place that started an important antiausterity movement in Spain. Demonstrators protested against the lack of a ‘real democracy’, high unemployment rates, particularly for young people, but also against politicians, the political system, political corruption, and welfare cuts more generally. See Reference [24] for further details. |

| 2 | Additional analyses of the evolution in the average evaluation of these indicators are available from the authors upon request. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | Our contribution was built upon classical texts that account for the complexity and multidimensionality of the concept of political support. We refer of course to David Easton’s seminal works [60], where he distinguished between support for the political community, the regime, and the authorities, but also to Pippa Norris [45], who developed a fivefold conceptualization that defined the political community, regime principles, regime performance, regime institutions, and political actors. |

| 5 | Cohorts used replicate one of the most common classifications internationally. Each cohort is usually identified with a generational label: those individuals born between 1911 and 1925 are labelled as the “Greatest generation”), the so-called “silent generation” (1926–1946), baby boomers (1946–1965), generation X (1966–1980) and millennials (1981–2000). See, for example, Reference [61]. Members of the crisis generation are included in the last cohort. |

| 6 | For expository reasons, although the typology comprises four categorical values, we preferred to run four separate binomial logistic models instead of a multinomial logistic regression. |

| 7 | The question is formulated as: “Which of the descriptions on this card comes closest to how you feel about your household’s income nowadays?”, with four possible responses. In the models, this variable was included as a dichotomous variable, referring, on the one hand, to those with economic difficulties (“Finding it difficult on present income” or “Finding it very difficult on present income”) and, on the other hand, to those with a good economic situation at household level (“Living comfortably on present income” or “Coping on present income”). |

| 8 | The local elections held at that time, on 22 May 2011, the vote share of the PP (37.5%) increased a little compared to the preceding local elections in 2007 (35.6%), while the PSOE suffered important losses, and, in four years, its vote share went down from 34.9% to 27.8% in 2011 [65]. In addition to that, in the general election on 20 November 2011, the PP increased its vote share with respect to the previous elections, going from 39.9% to 44.6% and its leader, Mariano Rajoy, became Prime Minister with an absolute majority. |

| 9 | If the variable age group is used, instead of year of birth, the results of the evolution are very similar. |

| 10 | These analyses are not shown in this text, but are available from the authors upon request. |

| 11 | A preliminary revision of the eighth round of ESS results shows that change trends are maintained, but it is necessary to spend more time to know if they are confirmed in the long term. |

| Interest in politics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| Satisfaction with democracy or/and trust in political institutions and actors * | Low | DISENGAGED | CRITICALLY POLITICIZED |

| High | CONFORMIST | SATISFIED | |

| Disengaged | Critically Politicized | Conformist | Satisfied | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1926–1946 (silent generation) | 1.08 | 1.83 | 0.42 | 0.78 |

| 1946–1965 (baby boomers) | 1.06 | 2.06 | 0.32 | 0.42 |

| 1966–1980 (generation X) | 1.00 | 2.28 | 0.29 | 0.55 |

| 1981–2000 (millennials) | 1.02 | 2.09 | 0.35 | 0.64 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benedicto, J.; Ramos, M. Young People’s Critical Politicization in Spain in the Great Recession: A Generational Reconfiguration? Societies 2018, 8, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8030089

Benedicto J, Ramos M. Young People’s Critical Politicization in Spain in the Great Recession: A Generational Reconfiguration? Societies. 2018; 8(3):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8030089

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenedicto, Jorge, and María Ramos. 2018. "Young People’s Critical Politicization in Spain in the Great Recession: A Generational Reconfiguration?" Societies 8, no. 3: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8030089

APA StyleBenedicto, J., & Ramos, M. (2018). Young People’s Critical Politicization in Spain in the Great Recession: A Generational Reconfiguration? Societies, 8(3), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8030089