Abstract

This study explored factors inspiring female university students in Saudi Arabia to choose entrepreneurship as their career choice. This explorative empirical study sought to explore this phenomenon in the context of a culture of socialization strongly attached to religion and steeped in tradition. Data were collected through a structured questionnaire survey administered to female university students. Descriptive statistics and logistic regression analysis were used to identify influencing factors. The results mostly support previous study findings on perceptions about the drivers of females’ aspirations in venture creation. Entrepreneurship and business-related courses and media roles are recognized as the most influential factors explaining reasons for the choice of occupation and career. However, this study found only mixed support for these variables. Interestingly, this study found that social learning theory was negatively and significantly related to the decision of female university students to start up a business as a career choice, opposite to previous findings. The findings will assist relevant authorities in facilitating an increase in female entrepreneurship to contribute to the national Vision 2030.

1. Introduction

Macroeconomic changes in the global economy since 1945 have resulted in the emergence of gender equity-based labor markets in developed economies, in tandem with socio-cultural and political developments. Females have progressively become more involved in the conventional workforce, with some shift in female paid employment from traditional jobs to non-traditional sectors and activities, but their engagement with entrepreneurship (e.g., starting their own businesses) has been less pronounced [1]. However, changes in the world business environment and society have encouraged increasing numbers of women to deem entrepreneurship a viable alternative career choice, and an estimated 200 million females are starting or running new businesses in 83 economies across the world [2], and by the year 2020 it is estimated that females will own 40–50% of all businesses worldwide [3]. In addition, entrepreneurship is the most obvious solution to the egregious unemployment among educated females worldwide, since it is not possible to achieve sustainable macro-economic development by conventional instruments relating to the labor market and job providers [4]. Consequently, female entrepreneurs are widely encouraged by governments, business sectors, educational institutions, researchers and policy makers as a part of women’s economic empowerment streams. It is evident that entrepreneurship is contributing not only to the sustainable development of women entrepreneurs, but also to the sustainable development of the country’s economy.

The current literature relating to women’s career aspirations regarding entrepreneurship is predominantly positioned in developed countries. Due to the multifaceted entrepreneurial phenomenon, researchers reported conflicting results about the influencing factors that explain a variety of women’s motivations to start a business [5]. Research claims that women’s socialization affects them to act differently, social roles/place may exclude them from social networks and institutional aspects affect women differently. The debate concerning the differences between male and female intention towards entrepreneurship usually focuses on gender’s characteristics [6]. It is generally agreed that women are motivated similarly to men in term of a true need for achievement, independence, and job satisfaction. However, they have less business education, face more barriers to access capital, and more slowly grow their business than men [7,8,9].

A wide range of motivations has been suggested in the literature regarding this complex and sensitive topic. As mentioned by Orhan and Scott [10], researchers have suggested a wide range of motivations for female entrepreneurs and there is no clear consensus on which factor exerts the greatest influence. The inconsistencies of the studies could be due to the population differences across countries [11], economic and political condition [12,13], business environments [13,14], social-cultural [13,15], and technological issues [13,16]. For example, Ozaralli and Rivenburgh [13] stated that the intention of an entrepreneur should also be influenced by the existing and anticipated economic and political infrastructure of the home country. Ascher [11] stated that population growth has an impact on female entrepreneurship as growth in population increases demand and generates competition for few jobs among more people and thus encourages more women to enter entrepreneurship activities. As a result, scholars are advocating the need for some well-established methodologies to capture the reasons to become an entrepreneur [17].

However, studies, especially of female students’ aspirations regarding venture creation in developing countries, have only emerged recently and are comparatively scarce [5]. Researchers such as Chowdhury and Shamsudin [4], Rametse and Huq [18], Amentie and Negash [19], and Abebe [20] mainly focused on this topic. Rametse and Huq [18] identified that parents are on the top of the list in influencing female student’s involvement in business. Chowdhury and Shamsudin [4] found no evidence of social influence on female intention, while higher education is more important. Gaining respect is the most influential motives according to Amentie and Negash [19]. Abebe [20] found that entrepreneurial education has a significant role in motivating students toward entrepreneurship.

With lack of sufficient data and exhaustive studies in developing countries, especially within Middle East and North Africa MENA region, very little is yet recognized about female entrepreneurs. Hattab [21] indicated that the share of female entrepreneurs in the Middle East and North Africa is far lower than other developing countries. However, variations between the region’s countries exist due to the size, natural resources, skills of human capital, and social and political circumstances. Several studies showed that MENA’s women entrepreneurs felt empowered, nevertheless these studies rely on data that did not include male entrepreneurs. In this case, it is not viable to be confident about whether gender-based barriers face women compared to men [22]. Particularly, there is virtually no academic literature that addresses the female students’ career aspirations in starting their own businesses in Saudi Arabia, a developing country with a major G20 economy. The current unemployment problem facing the young generation presents a serious matter, where approximately 78.3% of female university graduates are unemployed [23], with significant geographical, economical, legal, cultural, and political differences from Western developed and other developing countries [24,25]. In recognition of this, the country stresses several actions to fulfill its 2030 vision’s goals, which concern decreasing total unemployment rate from 11.6% to 7%; raising SME’s contribution to GDP from 20% to 35%; and enhancing women’s participation in the workforce from 22% to 30% [26]. The Saudi government has launched its ambitious vision in 2016. It mainly aims to fully exploit the Saudi unique competitive advantages to build the best future of Saudi. There are three competitive advantages: The incubation of the two holy mosques enables Saudi Arabia to play a leading role in the Arab and Islamic world, the use of investment power to diversify the economy, and the importance of the strategical geographic location connecting three continents: Africa, Asia and Europe. Vision 2030 is built around three themes: a vibrant society, a thriving economy and an ambitious nation. Each theme has its own goals. Programs are hence launched to achieve these goals. The theme of a thriving economy is very related to this paper. It focuses on empowering the education system to bridge the gap between the education outputs and the market needs. The theme also provides economic opportunities for the entrepreneur, the small enterprise and the large corporations. The potential of the Saudis, both male and female, are the rewarding opportunities that the Saudi government attempts to exploit. This is a challenging task since the female unemployment rate is higher than the male one. To lower the rate of unemployment, creating job opportunities for young women through entrepreneurship is regarded as one of the ideal solutions, if those youth have a high intention for business creation and are well equipped with the necessary entrepreneurial skills through education and training programs [27].

A Ministry of Labor report [28] emphasizes the role of SMEs—focusing on entrepreneurship and innovation—as a part of the government exertions in persuading investment, creating jobs opportunities, and supporting innovation. In cooperation with the SMEs Authority, Ministry of Labor reviewed laws and regulations to remove obstacles and encourage more Saudi entrepreneurs to start their businesses to employ themselves and open more jobs opportunities for others. They consider female participation in the field of entrepreneurship as essential for a young and fast-growing nation to attain sustainable economic development. Booz et al. [23] mentioned that, to incorporate women into the Saudi labor market, efforts should be given through programs encouraging entrepreneurship, professional improvement, and business skills. Kaled Abalkhail—a Ministry of labor spokesman—said: “There are now 600,000 Saudi women working for the private sector, 30,000 of whom joined the market last September and October”, whereas “this figure stood at 90,000 Saudi women only back in 2011”[29]. By addressing this void, the significance of this study is clearly justified.

Based on the identified literature gap, the following two research questions were devised:

(a) What is the level of entrepreneurial aspiration among female university students in Saudi Arabia?

(b) What factors encourage female university students to deem entrepreneurship as a career choice in Saudi Arabia?

The following sections review related literature and present the theoretical framework in the context of previous studies, report the research method and analysis, and present the findings and conclusion, including a research agenda.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Major efforts have been made to identify different drivers that cause individuals to become entrepreneurs. These drivers are shaped by different life circumstances and career factors influenced by the social, economic and political dimensions [30]. The existing well-established four entrepreneurial motives theories (individual motivations and goals; social learning; human capital; and environmental influences) are grouped into two categories: drive theories and incentive theories [31]. These theories suggest that the internal needs and external rewards motivate an individual to start a new business. The following section considers these four theoretical perspectives relating to goal factors, environmental factors, social learning theory, and human capital, as well as demographic factors, each of which has a corresponding body of empirical research. The proposed study derives from the well-established four theoretical perspectives explaining the inclination of establishing own business: individual motivations and goals; social learning; human capital; and environmental influences. A theoretical perspective is important for research as it serves to organize thoughts and ideas and make them clear to others. These theories were developed based on empirical works which were conducted mostly in developed and non-Muslim countries and showed relationships between these individual level factors and inclination of starting own business as a career choice. These theoretical perspectives are described as “a combination of ideas and assumptions about reality that inform the questions we ask and the kinds of answers we arrive at as a result about driving forces inspiring females to choose entrepreneurship as their career choice”. We used these four established theories to examine applicability of these theories in Saudi Arabia, which exhibits a culture of socialization strongly anchored to religion and steeped in tradition. By addressing this void, the significance of this study is clearly justified. Hypotheses as to the applicability of each view in explaining entrepreneurial aspiration among female university students in the Saudi Arabian context are presented.

2.1. Motivation and Goal Factors

Literature shows that entrepreneurs are driven by several goals which have been widely investigated with regard to their influence on business start-ups. Most studies have identified that the main goal factors motivating women’s aspirations to start a business are the desire for money/wealth, social status and power/being own boss, enjoy challenge and risk, and to contribute to the national economy [18,32,33,34,35,36]. For example, Azmi [32] noted that the desire to be own boss (social status/power) was an important goal factor of female university students in Ethiopia for starting a business. Ilhaamie et al. [33] found that earning more money was the most important goal factor that generated higher motivation towards new business start-up. Amentie and Negash [19] acknowledged that a challenging career was a key positive feature for the female students when considering starting their own business. Rametse and Huq [18] observed that female students in Botswana are motivated by their desire to contribute to the national economy to do business. Conversely, other research illustrated that women do not seek to become entrepreneurs for economistic reasons, but mostly to gain lifestyle benefits such as work flexibility as well as commitment to family and work [37].

Compared with other countries, the occupational segregation and wage disparities between males and females in Saudi Arabia are greater [38]. Due to the implicit structural and perceptual barriers that accompany an entrepreneurial career, we might expect Saudi Arabian educated female students to be motivated by earning more money, social status and power (prestige), commitment to contribute to the national economy, and preference to enjoy the challenge and risk in starting their own businesses. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H1:

Goal factors are positively associated with female students’ aspirations to start businesses as a career choice in Saudi Arabia.

2.2. Environmental Factors

The environment in which entrepreneurship occurs is highly important for new ventures and significantly determines the start-up process [39]. Nematoollah et al. [40] stated that environmental factors play an important role in weakening or strengthening the intentions of people to create a new business. There are many environmental factors discovered in different research papers that influenced individuals to become entrepreneurs. The existing research findings showed that the most critical environmental factors are access to financing, personal entrepreneurial education qualities and also satisfactory government support, which are considered to have a positive impact on individuals’ intention in starting-up their own business [4,41,42,43,44,45,46]. For example, Nasser et al. [43] found that financial support from the government, especially in terms of start-up capital, was an important factor that influenced females in launching their own businesses. In addition, Chowdhury et al. [4] reported that education (particularly university courses about business and entrepreneurship) plays a remarkable role in influencing young people’s aspirations to become potential business people, which is also closely linked to the role of the media, which structures people’s perceptions of entrepreneurship [19,47,48]. For example, Amentie and Negash [19] reported that about 77% of female university students in Ethiopia were positively influenced by the media to start their own businesses. In view of this exclusive and important relationship between media and student aspirations to start their own businesses, this study hypothesized that:

H2:

Environmental factors are positively associated with the interest of educated female students in starting-up their own business in Saudi Arabia.

2.3. Social Learning Theory

The social learning theory developed by Rae [49] explains entrepreneurial behavior and career development in terms of learning by observation of the behavior of others, often denoted as role models. The role model is increasingly acknowledged as an influential factor for the choice of occupation and career. Several existing studies reported a positive impact of parental role models on the decision to start up a business [18,19,50,51]. In addition, some studies found that the presence of a friend or relative in an entrepreneurial role was positive and significantly associated with increased expectancy for an entrepreneurial career [52,53]. Moreover, Amentie and Negash [19] stated that working for an entrepreneur or knowing an entrepreneur had a positive impact on entrepreneurial career choice.

In the Saudi context, a comparatively small percentage of females are entrepreneurs. As the expectation for females is to choose a career that is compatible with family life and responsibilities and not to have demanding careers, socialization and norms for female students to be entrepreneurs would be minimal. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H3:

The influence of social learning theory is negatively associated with the tendency of educated female students to start-up their own business in Saudi Arabia.

2.4. Human Capital

From a human capital viewpoint, it is expected that the level of education, previous entrepreneurial and business experience and skills influence the decision to start up a business. Several studies show that level of education and previous experiences were positively influential factors among students who reported that they are likely to set up a business venture [19,54,55,56,57]. For example, Amentie and Negash [19] stated that the level of education and previous business experience are critical to attract the young to start up a business. Dolinsky et al. [58] also found that entering into a business increased with higher levels of education. Based on the previous research findings, it is expected that a higher level of education and previous business experience would be associated with increased propensity to set up a business venture, leading to the following hypothesis:

H4:

The influence of a higher level of education and previous business experience is positively associated with the intentions of female students to start-up their own business in Saudi Arabia.

2.5. Demographic Factors

Wang and Wong [59] stated that to date an inadequate number of studies has investigated the influence of demographic factors in shaping entrepreneurial intentions of students and the findings of these studies are not consistent. Several studies have reported that demographic factors play a vital role in the formation of entrepreneurial intention, while other studies reported that demographic factors do not have a significant role. For example, studies that investigated career choice intentions of students intending to start up business after completing their studies reported that there is a significant positive relation between age [60,61,62], marital status [60,63], family type [64,65,66,67], and having children [68] and entrepreneurial intention. At the same time, other studies stated that there is no significant relation between age [69,70], marital status [71], and having children [72] and a female’s propensity to start their own business as a career choice. Some studies also reported that there is a significant negative relationship between age [73], marital status and [74] having children [19,68,75,76] and entrepreneurial intention. Based on our review, we propose a null hypothesis:

H5:

There is a significant positive relation between demographic factors and female’s propensity to start their own business as a career choice.

3. Research Methodology

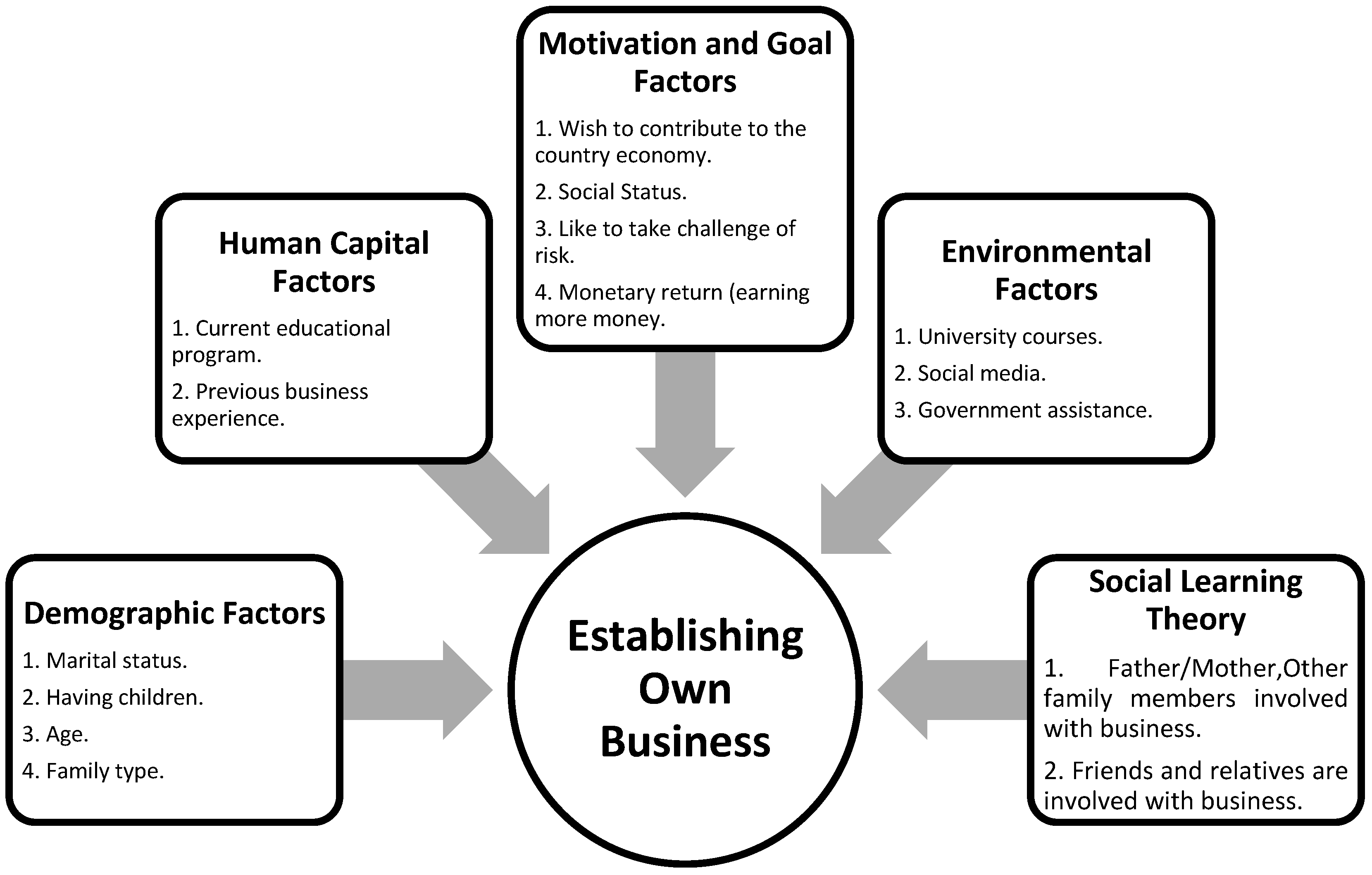

Based on the preceding literature review, this paper provides a comprehensive analysis on the impact of four theoretical perspectives (goals, social learning, environmental, and human capital) on female university student’s entrepreneurial intentions. Based on these four theoretical perspectives, an integrated model was developed and is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed integrated model establishing relationships among influencing factors and setting own business.

From the established body of literature, we identified and analyzed relevant articles and developed a conceptual map illustrating the expected relationships and major hypotheses (Figure 1). These four perspectives and the demographic factors comprise the individual level variables, which are expected to be differentially associated with the intention of female university students to deem entrepreneurship as a career choice. Although it is recognized that the network affiliation (social capital) and GDP per capita will also affect an individual’s decision, these were not the focus of this study. The conceptual model shows impact pathways linking goal, social learning, environmental and human capital perspectives, and demographic factors to encourage female university students to establishing own business as a career choice in Saudi Arabia. The factors affecting the four perspectives, such as marital status, having children, age, family type, current educational program, previous business experience, wish to contribute to the country economy, social status, university courses, social media, government assistance, other family members are involved with business except father, and friends and relatives are involved with business except father are thought to have potential impacts on establishing own business as a career choice among female students. We excluded some important factors that encourage females for starting own business as these factors are not applicable in Saudi Arabian context such as religion, ethnicity, etc. The reasons behind the exclusion of these factors are all Saudis are born Muslims. Therefore, we are not expecting any response from non-Muslim Saudi female students. In the Saudi culture, it is a sign of disrespect to differentiate between Saudis based on their ethnicity. The society is built on such cultural and religious values that discourages such divisions. Therefore, we strongly avoided such questions. The conceptual framework is a reflection of what we proposed to test the above five hypotheses.

3.1. Questionnaire Design

The data for this research were collected using a comprehensive questionnaire developed based on the in-depth literature review and analysis, and then pre-tested and validated by a focus group. The format was confirmed as being appropriate with language levels understood as the survey was conducted in both English and Arabic, using the back-to-back translation approach [77].

3.2. Sample Design and Selection

After getting the ethical clearance from the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Abdulaziz University, a focus group pre-tested the questionnaire to assess its face validity. The focus group was comprised of four female university students drawn from public and private universities and two academic experts. Their feedback confirmed the questionnaire’s validity, which subsequently informed the main study. Following the pre-test stage, a survey was conducted where the revised questionnaire was administered to a systematic random sample of 550 female students (undergraduate and postgraduate) who had completed at least one year of their program, because these students would be able to adequately evaluate their experiences about their study program. Questionnaires were distributed in classrooms as well as through a university-endorsed email. The potential respondents were encouraged to complete the questionnaire with a reminder call one week, two weeks and three weeks after the original distributing questionnaire. It is well-known that one of the main limitations of respondent-driven sampling strategies is the difficulty encountered in evaluating the size of the population being studied. There were 391 usable responses. This study considered only those responses that showed intentions to start up their own business as their career goals, yielding a 54.5% response rate, which is acceptable for such surveys [78]. A minimum of 10% of completed surveys was independently monitored and validated in real time by the project leader. The survey provides insights into the collective opinions of the respondents on a wide range of topics and their perceptions.

We believe that the demographic representation and the distribution of the size of participating universities and samples are the important measure of their representativeness. The distribution of samples is presented in Table 1. Demographic representation was considered as the survey attempted to cover whole Saudi Arabia. According to Ministry of Education [79], proportions of universities (private and public) in Central, West, Eastern, Northern and Southern regions are 33%, 27%, 14%, 14%, and 11%, respectively. In the sample selection, almost the same proportions of universities were maintained to achieve demographic representation. In addition, the distribution of the respondent was compared with the national population distribution reported by General Authority for Statistics [80] to check the representative nature of the respondents. For example, the proportions of respondents in this study drawn from Central, West, Eastern, Northern and Southern regions are 29.3%, 32.3%, 15.3%, 7.8%, and 15.3%, respectively. These proportions were close to the national population distributions of Central, West, Eastern, Northern and Southern regions (i.e., 29.5%, 32.0%, 15.1%, 7.9%, and 15.5%, respectively). Therefore, it can be argued that the respondents closely represent the national distribution of universities and populations.

Table 1.

Distribution of samples.

3.3. Model Design

First, we conducted a multivariate analysis to provide a useful complement to the descriptive snapshot; and second, a logistic regression analysis to explore factors influencing female students with regard to starting own businesses in Saudi Arabia. The specific regression model that we estimated using the samples is represented in the following equation, representing the variables described below:

where YASOB = 1 if participants perceived starting their own business to be “attractive” as a career aspiration and 0 if they perceived it to be “not attractive”.

X1–9 are the independent variables representing motivation index, environment index, social learning theory index, current education program (diploma = 1, bachelor = 2, master’s/PhD = 3), business experience (yes = 1, no = 2), marital status (single = 1, married = 2, divorce = 3), children (yes = 1, no = 2), family type (nuclear family = 1, joint family = 2), and age (17–23 years = 1, 24–30 years = 2, 31–36 years = 3, >36 years = 4), respectively. β1–9 are the coefficients of explanatory variables and u is the error term.

3.4. Variables and Their Measures

3.4.1. Dependent Variable

The dependent variable for this research (Saudi female students’ perception of the attractiveness of starting their own businesses as a career goal) was measured by a question with a response of “attractive” and “not attractive”.

3.4.2. Independent Variables

The independent variables were divided into five groups to capture the dimensions of the theoretical perspectives: goals, environment, social learning theory, human capital and demographic.

An exploratory factor analysis (varimax rotation method) was carried out to test whether the items used in the survey were able to truly measure the specified constructs. The results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Rotated factor matrix, reliability, and validity statistics.

3.4.3. Goal Index

The results of factor analysis showed that four items have a factor loading above 0.60 grouped into one factor, which indicates that these items are adequate to measure female students’ goals related to starting their own business. The validity of the “goal index” construct is confirmed by convergent validity (factor loadings of respective measured items >0.50) and discriminant validity [AVE (0.526) > r2 (0.334)]. Cronbach’s α value of 0.786 for “goal index” indicates high level of reliability and internal consistency of the construct (Table 2).

3.4.4. Environment Index

Three environmental influences-related items have factor loading above 0.50 and are grouped as one factor used to measure the “environment index” construct. The validity of the “environment index” construct is confirmed by convergent validity (factor loadings of respective measured items >0.60) and discriminant validity [AVE (0.639) > r2 (0.420)]. Cronbach’s α value of 0.784 for composite “environment index” has confirmed the reliability of the construct, which indicates that the items studied are internally consistent, and each of the items is unique and not a repetition (Table 2).

3.4.5. Social Learning Theory Index

The “social learning theory index” can be measured by two items having a factor loading above 0.70. The validity is statistically demonstrated by convergent validity (factor loadings of respective measured items >0.60) and discriminant validity [AVE (0.545) > r2 (0.476)]. Cronbach’s α of 0.716 for composite “social learning theory index”, onfirming the reliability of the construct, which indicates that the items studied are internally consistent and each of the items is unique and not a repetition (Table 2).

3.4.6. Demographic Variables

Four demographic variables are considered in this study: marital status, having children, age and family type (joint or nuclear).

3.4.7. Human Capital

Current educational program and previous business experience are considered as human capital in this study.

4. Findings

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics showed that most of the respondents were teenagers (61%). An overwhelming majority (74.7%) of all respondents were single and 71.7% were studying for bachelor’s degrees, among which vast majority (72.6%) was from business studies and remaining 27.3% was from science. About 62% were living in nuclear families. As shown in Table 2, 81% of respondents were from non-business family backgrounds, while only 19% were from such provenance. About 30% were from families with monthly income of SR 15,000–25,000. The majority (82.7%) had no children and 74.7% had no previous business experience. Table 3 summarizes respondents’ descriptive statistics.

Table 3.

Descriptive snapshots of the dataset.

4.2. Students’ Business Preference

Table 4 shows that the majority of respondents (83.3%) reported that they would prefer to do their own business, while only 16.7% would prefer a joint business as their career choice. The obvious attractions of a sole proprietorship include establishing an enterprise, using their own capital instead of taking money from investors, avoiding deals that affect their management control, reducing impediments to running companies with total freedom, and turning their vision into reality. Interestingly, there was a marked preference for starting a small/medium business (71.3%), which reflects some degree of risk avoidance in wishing to avoid the potential pitfalls of too large an enterprise and to have more opportunities for creativity and originality [81]. In addition, fresh and female graduates have less access to formal credit [82,83].

Table 4.

Preference towards business options upon graduation (type of business).

Table 5 shows that the majority (59.33%) of respondents stated that their family members always discouraged them from setting up their own business as their career goal, while only 28.33% respondents stated that their family members always encouraged them and the remaining 12.34% responded neutral. This reflects that a large percentage (about 60%) of parents discouraged the female students from setting up their own businesses as their future career goal. The results of Chi-square test show that, in terms of intention to start up own business, there is no significant (p = 0.56) difference between the perceptions of female students regardless of family’s business background. Those who come from a family which is somehow involved with business are a bit less interested in setting up their own business compared to others.

Table 5.

The relationship between family background, study area and starting own business.

Table 5 also shows that the majority (72.7%) of respondents stated that they were from business schools, while only 27.3% respondents were from other schools. About 89% of students those were from business school reported that they are inclined to start up new business as it is attractive to them while only 46% students from other schools considered starting up new business is attractive. This reflects that setting up own business has been considered by business school students as attractive as their future career goal compare to the students from other schools. The results of Chi-square test show that there is a significant difference (p < 0.001) difference between the perception of female students from business school and other schools intend to start their own.

In response to the question about whom or what influences female students’ intention to start their own business, the majority (87.0%) of respondents replied that they were influenced by educational courses they took, with a significant average rating of 4.35 on a scale of 1 to 5 for all participants surveyed, followed by the media (83.7%), monetary return (74.0%), desire to contribute to the national economy (69.7%), enjoyment of challenges (68.7%), social status (67.0%), and then government assistance (44.0%). Relatively small proportions of respondents replied family background (28.2%), friends and relatives (26.7%), and previous business experience (25.3%) as influences on female graduates starting their own business (Table 6).

Table 6.

Influential motivating factors in starting own business.

4.3. Testing the Hypotheses

The logistic regression model was constructed to examine and explain the perception of Saudi female students for choosing a business as their career goal. There are various potential factors that could attract young people to entrepreneurship and to consider it as their career goal, which are comprehensively considered by the model [84]. The model appears to fit the data reasonably well. The Chi-square value of 145.572 at 0.001 significance level with 13 degrees of freedom indicates that logistic regression is meaningful in the sense that the explained variable is related to each specified explanatory variable. The results of fitting the logistic regression model for the sample data are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Regression on entrepreneurial intention.

The variable goal index (X1) as a determinant of female students’ perception of starting their own business as their career aspiration is statistically significant at the 0.05 level. The result indicates that the students with higher goal index are 2.894 times more likely to be interested in setting up own business after completion of their education than those with a lower goal index. Thus, goal index has a significant influence on perception to deem entrepreneurship as a career choice, which supports hypothesis (H1): goal factors are positively associated with female students’ aspirations to start businesses as a career choice in Saudi Arabia. To further analyze H1, a correlation analysis was conducted between perceptions of career choice and the four motives: remuneration, social status and power (prestige), commitment to contribute to national economy, and enjoyment of challenge and risk. The results indicate that all four motives are positively and significantly (p < 0.01) associated with the perceptions of female students regarding entrepreneurship as career choice, with the strongest relationship between “career choice” and social status and power/prestige (r = 0.662) (Table 8).

Table 8.

Inter-correlation between perception about career choice and goal factors.

The variable environment index (X2) is shown to be a significant determinant of female students’ perception of starting their own business as their career aspiration with a statistical significance level of 0.022. Keeping other variables constant, the positive coefficient value of 1.017 represents an increase in the tendency towards new business start-up due to the increase of one female student with higher level of environment index. The result also indicates that students perceiving a higher level of environment index are 2.764 times more likely to be entrepreneurial compared to those with a lower level of environment index. The correlation result shows that all factors of environment index except “government assistance” are positively and significantly (p < 0.01) correlated with the perception to start new business as a career choice, with the strongest relationship between “career choice” and “encouraged by university courses” (r = 0.213). Thus, this supports hypothesis (H2): environmental factors are positively associated with the interest of educated female students in starting-up their own business in Saudi Arabia.

To include social learning theory as a cause for female students’ interest towards entrepreneurial aspirations, we use only the involvement of father/mother/family members, friends and relatives with business for the model. The family socialization variable (X3) is a negative and significant (p = 0.009) determinant of career aspiration of female students. The negative coefficient value (−1.348) represents the increased presence of parents, friends and relatives involved with business and decreased tendency of female students towards new business start-up. The result also indicates that students with higher social learning through perceived family, friends, and relatives’ entrepreneurial role are 0.260 times less likely to have interest in entrepreneurialism than students with lower social learning. Correlation between career choice and factors of social learning theory index show that factors of social learning theory index are negatively correlated with the perception to start new business as a career choice. In other words, in most cases, female students are discouraged by their parents, friends and relatives for their intention towards new business start-up, which supports hypothesis (H3): the influence of social learning theory is negatively associated with the tendency of educated female students to start-up their own business in Saudi Arabia. The findings of this study show no support for social learning theory and the findings of existing studies reviewed previously.

The regression analysis also indicates that intention of female students to set up a new business significantly varies across education levels. The results show that diploma and bachelor’s students are 0.234 and 0.154 more times less likely to intend to be entrepreneur than postgraduate students (respectively). Thus, the findings support the hypothesis (H4): the influence of a higher level of education and previous business experience is positively associated with the intentions of female students to start-up their own business in Saudi Arabia.

The coefficient of the variable of previous business experience (X5): was found to bear a positive sign with the statistical significance at 0.01 level, indicating that female students (sample size is very low) who were connected to business or business development from a young age tended to show a higher level of interest in entrepreneurship as a career than those who were not connected with business at all. Majority of these respondents were from low income family and their family monthly was less than 5000 Riyals. The result also indicates that the female students with business experience are 10.310 times more likely to intend to start a new business than the students who do not have such experience.

The factor of having a child (X7 = 1) was found to bear a negative sign with statistical significance at the 0.01 level, indicating that female students having children tended to show a lower level of interest in entrepreneurship than others. The results of regression analysis also showed that female students with children are 0.228 times less likely to intend to start a new business than those who did not have children. Thus, the findings do not support the hypothesis (H5): having children is positively associated with the intentions of female students to start-up their own business in Saudi Arabia.

Family type plays some role in an individual’s choice of profession. This variable (X8) bears a negative sign, meaning that female students who are from nuclear families are significantly (p = 0.05) (0.392 times) less interested to consider entrepreneurship as a career choice than others. The indicates that female students from nuclear families are less likely to consider entrepreneurship as their career goal than students from joint families. Thus, the findings support the hypothesis (H5): family type of the respondents is associated with the intentions of female students to start-up their own business in Saudi Arabia.

The results also indicate that marital status (X6) and respondents’ age (X9) do not have an impact on the carrier choice. The study results show that married female students are less likely to intend to start their own business as their career goal compared to single and divorced women, but there is no statistically significant difference among these three groups. In addition, the study results stated that older students have a higher entrepreneurial intention than younger students, but there is no statistically significant difference by age group. Thus, the findings do not support the hypothesis (H5): having children is positively associated with the intentions of female students to start-up their own business in Saudi Arabia. See Table 9 and Table 10.

Table 9.

Inter-correlation between perception about career choice and environmental factors.

Table 10.

Inter-correlation between perception about career choice and social learning theory factors.

5. Discussion

A huge raft of policies, strategies and programs are incorporated by the Saudi government and its partners in Vision 2030 with the fundamental aim of driving national development so that Saudi Arabia can become an exemplary and leading nation in all aspects by unlocking the talent, potential and dedication of its young men and women. Most of these policies are concerned with institutional reforms; the development of religious, cultural and social norms; and financial support and regulation, while the less tangible, but essential, issue of citizen awareness and engagement is ignored, such as fostering the attitudes of female students towards entrepreneurship as a career choice. A lack of understanding of the attitudes and perceptions of female students towards entrepreneurship as well as the ways of operationalizing them is a major barrier to national progress. However, some studies about women entrepreneur are developed [85,86,87], no study was found exploring female students’ career aspirations in starting their own businesses in Saudi Arabia. Thus, there is a crucial need to gain knowledge about young educated women and their views concerning starting their own businesses, and it is essential to investigate and recognize factors that motivate potential female students to initiate business activity. This research adds more information to a seriously under-researched topic by gaining an overall picture of entrepreneurial aspirations of female students toward self-employment in Saudi Arabia.

This study addressed the two research questions by providing an overview of the level of entrepreneurial aspiration among the female university students in Saudi Arabia and identified the factors that encourage female university students to deem entrepreneurship a career choice. This is the first systematic study of Saudi female students’ entrepreneurial aspirations in starting and growing their businesses. This study attempted to investigate the level of entrepreneurial aspiration among the female university students in Saudi Arabia and identified the factors that encourage them to pursue a career as an entrepreneur.

Female university students in Saudi Arabia generally exhibit a strong latent interest in establishing their own business as a career goal. This result is promising and might serve as a signpost to sustain overall socio-economic development, especially to overcome female unemployment problems in the 21st Century, for any nation which exhibits a culture of socialization strongly rooted in religion and immersed in tradition, such as Saudi Arabia. Saudi female students’ higher levels of entrepreneurial intention (more than 84% in this sample) compare to other countries seem somewhat puzzling. It may be the case that as Saudi Arabia does not provide more attractive jobs in private and public sector for graduates due to socio-cultural barriers, leading to high entrepreneurial intentions. It can also be explained by the GEM project which revealed that developing countries with low wages and high unemployment rates have recorded higher entrepreneurial activity than most developed countries [88]. Iakovleva et al. [89] and Davey et al. [90] also concluded that respondents from developing countries/economies were more likely to envisage future careers as entrepreneurs and have stronger entrepreneurial intentions than those from industrialized countries. Given these facts, however, considering the overall high level of entrepreneurial intention of Saudi female students, we cannot claim for certain that this is the case for our Saudi sample.

Similar to prior research that investigated entrepreneurial intentions, the results of this study support the positive association between entrepreneurial intentions and the goal factors (social status/prestige, earning more money, desire to contribute to national economy, and enjoy challenge and risk), environmental factors (university courses, media, and availability of government assistance), human capital factors (previous business experience and higher education level), and demographic factors (no child and joint family type) in line with more recent research by Amentie and Negash [19], Parker [51], and Falck et al. [52]. The reported findings indicate that all variables of the three theoretical perspectives (goals, environmental and human capital constructs) positively and significantly motivated women’s aspiration to start up a business. The results mostly support previous study findings on perceptions about the drivers for female aspirations in venture creation except the social learning perspective. It seems that some other factors are more influential on the entrepreneurial intention of Saudi female students than the opinion of their family or close friends.

An important finding of this study is that the influence of family entrepreneurial role models in their career aspirations was not evident. This study surprisingly found a negative and significant impact of encouragement of parents, friends and relatives as role models on female students’ intention towards new business start-ups. This implies that educated female students are not inspired by entrepreneurs in their social context; rather, the presence of entrepreneurs in their social milieu reduces the desire of female students to start new businesses which does not support the findings of earlier studies [13,91,92]. However, their personal attitudes toward becoming an entrepreneur were high. This led us to consider that culture-specific factors might be responsible for this different finding. Parents’ beliefs, attitudes, behaviors and expectations towards children (i.e., parenting styles), which vary across countries, could be one of the potential reasons, along with the fact that the presence of entrepreneurs in Saudi women’s close family achieves their goals for remuneration and social status/power by default; given that these goals were reported to be the primary motivators for Saudi female students to engage in entrepreneurial activity, when these demand are met they are consequently unmotivated to be entrepreneurs themselves. In addition, a lack of suitable role models to inspire young female students could be another potential reason for this finding, which contrasts to the findings of existing empirical studies. In addition, culture, practices and social norms in Saudi Arabia entail that even when women are permitted to become involved in business, it is expected that they will choose a career that is compatible with family life and responsibilities (i.e., not too demanding in terms of the fulfillment of family expectations). Thus, we can draw the conclusion that the negative relationship could be due to cultural. Saudi Arabia is a country which exhibits a culture of socialization strongly anchored to religion and steeped in tradition. The Saudi family structure encourages Saudi women to give the family more priority than entrepreneurs. When the parents are successful entrepreneurs, women usually have no courage to do business. The opposite can be true as women will be forced to do business to earn a living and satisfy their needs. Anyway, we strongly argue that such findings need further research to find out specifically why this is the case.

Consistent with goal perspective approach, remuneration, acquiring social status/power, contributing to national economy, and enjoying challenges and risk appear to be relevant to entrepreneurial intention. The logistic regression analyses with the inclusion of all factors as well as correlation analysis between perceptions of career choice and four motives showed that having higher aspiration of acquiring social status, contributing to the national economy, gaining more money/wealth enjoying risk and challenges might be helpful in starting a new business made significant contributions on entrepreneurial intent for Saudi students. This affirms previous studies in finding that females who have higher motivation are more likely to engage in entrepreneurial activities [18,19,32,33,34,35,36]. Saudi female students perceived themselves as risk and challenge takers and ready to contribute to the national economy.

Consistent with the environmental perspective approach, the result implies that the media, university courses, and government assistance have influenced female students in Saudi universities to consider entrepreneurship as their career aspiration. These factors have a significant influence in motivating, enhancing and acquainting students with essential entrepreneurial skills and knowledge and in creating strong passion towards entrepreneurship. This finding is in line with existing studies which identify environment as a cause of mind-set change of female towards new business start-up [4,19,20,33,48,93,94]. The results regarding the influence of education on entrepreneurial intention confirmed that entrepreneurships and business educational courses were the main factor influencing female students’ intention to start their own businesses, as in Abebe [20]. Having taken a class that discusses particularly entrepreneurship and business made a significant influence on the intention of Saudi female students. This finding may well suggest that entrepreneurship and business courses at Saudi Arabian universities educating them for entrepreneurship. The students who expressed a higher intention to start a new venture reported that they have taken/are taking such a course. The logistic regression analyses with the inclusion of all factors showed that having taken courses that might be helpful in starting a new business significantly contributed to entrepreneurial intent for Saudi students.

We also investigated the role of media to inspire young Saudi female students towards entrepreneurship. The interesting finding was higher scores in media influence though Saudi Arabia exhibits a culture of socialization strongly rooted in religion and immersed in tradition rather focusing on female’s competition, material success and ambition. This finding sound consistent with previous studies which evident that media plays an important role in influencing the entrepreneurship phenomenon, by creating a discourse that transmits values and images ascribed to entrepreneurship, by providing a carrier promoting entrepreneurial practices, and by encouraging an entrepreneurial spirit in the society [19,47,48]. This finding of the study led us to consider that the current Saudi government is concerned about the role of Saudi women in society and is putting efforts to promote entrepreneurship among Saudi women which could might be responsible for this interesting finding, although we should be cautious in making generalizations with limited data. At the same time, lower scores in government assistance availability indicates that the overall assistance from the government for female entrepreneurship is not up to the level.

The impact of human capital factors on entrepreneurial intention revealed similar results of earlier studies. This study found that students who are in upper level program are more entrepreneurially inclined and have strong intentions to pursue an entrepreneurial career. In general, it is true that the higher the educational level, the higher the ability to think rationally, recognize the importance of entrepreneurial traits, and assimilate more business knowledge. This study is supported by the findings of previous studies which indicate that females with higher education are more likely to intend to set up new businesses [19,54,55,56,57]. The findings also revealed that the students with entrepreneurial/business experience expressed a higher intention to start own business. This result is consistent with the findings of earlier studies which reported that students with previous business experience have a significant and positive influence on their ambition to pursue an entrepreneurial career [19,20,32,95]. This is an expected finding given that business experiences or activities provide students with an opportunity to promote the kind of creative thinking and idea generation central to innovation and new venture development, to acquire certain business skills, confidence and vision, all of which contribute to inclination to start a new business. The gaining of these essential qualities may be a potential reason for Saudi female students to express a higher intention to start their own business.

Another interesting finding was that female students having children showed a lower level of interest in entrepreneurship than others which is inconsistent with the finding of other studies [66,70] but affirming previous studies [19,65,68,76]. The main reason could be the strong family orientation prevalent in Saudi culture and the existence of institutional arrangements that support the working mother model with the proviso that she gives priority to family responsibilities. In Arab societies, the primary and traditional responsibilities of a female are childcare and housework, which is often why they do not have sufficient time to develop the entrepreneurial knowledge or skills essential to start a new business. In addition, another finding of this study revealed that the students who are from joint family are more inclined to start their own business after completing their graduations. This finding is similar with previous study findings [64,65,66,67]. They found that European entrepreneurs rely on familial ties in developing their business. There could be several explanations for this finding. There are more opportunities for the female students who are from joint families to get sufficient moral, psychological and financial support conducive to female entrepreneurialism. In addition, joint families often play a crucial role in helping women entrepreneurs manage business and family responsibilities, such as looking after children, doing housework, etc. It is often the only practical solution, especially when childcare services are limited and the family income does not allow for private care. The culture of Saudi Arabia pervades these particular rationales.

6. Conclusions

The systematic investigation of individual factors influencing inclination of female higher education students to deem entrepreneurship a viable alternative career choice examined the applicability of four theoretical perspectives. This research considers the explanatory power of these four perspectives, derived from studies in developed and non-Muslim countries in a developing and Muslim country context, which has a dominant culture of socialization strongly anchored in religion and steeped in tradition. In terms of culture and social structures, several differences exist between Saudi Arabia and other developed and developing countries where the majority of research on women entrepreneurs has been conducted. This variation in culture and social structures affects the explanatory power for the four theories. Overall, the findings of this study call for a holistic approach to understanding entrepreneurial intention. This study found only mixed supports for previous studies which has been explained in discussion part. Taken together, the findings of this study reflect the differential effect of inspiring factors (goal, environmental, social learning, human capital and demographic) depending on the country context.

The key contribution of the paper is its evidence concerning the effects of family entrepreneurial role models on perceptions of female higher education students to start up business as a career choice. In fact, educated female students are not inspired by entrepreneurs in their social context; rather the presence of entrepreneurs in their social milieu reduces the desire of female students to start new businesses. The findings of this study have significant research implications. Most studies reported that parental role model is a direct and significant, influential factor for the choice of occupation and career, while this study shows that effects of parental role model depends on parenting styles and social and religious context. Thus, we have contributed a new insight to the growing body of research addressing factors inspiring female university students in Saudi Arabia to choose entrepreneurship as their career choice.

This result is promising and might serve as a signpost to sustain overall socio-economic development, especially to overcome female unemployment problems in the 21st Century, for any nation which exhibits a culture of socialization strongly rooted in religion and immersed in tradition, such as Saudi Arabia. The findings will assist relevant authorities in taking the right courses of action to increase female entrepreneurship, helping contribute to achieve Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. The findings draw attention to the importance of macro-level governmental improvements. The findings in this study provide several recommendations for Saudi Arabian policy-makers. Study suggests that the government should deliver some practical programs to change parents’ mind-set to encourage their children to create jobs instead of finding jobs after graduation from higher education as role model is increasingly being acknowledged as an influential factor for the choice of occupation and career around the world. It is also that rather than restricting entrepreneurship education to classes, te educational institutions in Saudi Arabia should incorporate capstone courses which links classroom teaching with real life experiences and arrange short-term training sessions to develop female students’ skills and to enable them to acquire work experience. To address the emotions and attitudes of students through experiential learning and practical experience, educational institutions should design their courses in a way that stimulates more experimentation and creative thinking.

We understand that the findings in this study may not be generalizable across all developing countries due to cultural differences and the relatively small sample size. Future studies may consider a larger sample to reveal other important factors such as whether the intention to start a business decreases after women have married and had children, which influences the decision of Saudi female to start up a business and the business environment in which they operate. Future studies may also need to target female students who chose not to start their own businesses to improve the knowledge about the factors that are preventing entrepreneurship among Saudi female students.

Author Contributions

M.M.I. the team leader and designed the research instruments in consultation with other authors and conducted the research as an expert in the areas of entrepreneurship. A.A.H.B. and T.S.A. analyzed data and M.M.I. contributed to the analysis of the results and drafting of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant No. G-477-120-1436. The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR for technical and financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Domenico, D.M.; Jones, K.H. Career aspirations of women in the 20th century. J. Technol. Educ. 2006, 22, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, J.D.; Brush, G.C.; Greene, G.P.; Litovsky, Y. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2014 Women’s Report; Global Entrepreneurship Research Association: Wellesley, MA, USA, 2015; Available online: http://gemconsortium.org/report/49281 (accessed on 21 December 2016).

- Boz, A.; Ergeneli, A. A descriptive analysis of parents of women entrepreneurs in Turkey. Intellect. Econ. 2013, 7, 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, M.S.; Shamsudin, F.M.I.; Che, H. Exploring potential women entrepreneurs among international women students: The effects of the theory of planned behavior on their intention. World Appl. Sci. J. 2012, 17, 651–657. [Google Scholar]

- De Vita, L.; Mari, M.; Poggesi, S. Women entrepreneurs in and from developing countries: Evidences from the literature. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, C.; de Bruin, A.; Welter, F.; Allen, E. Gender embeddedness of women entrepreneurs: An empirical test of the 5 “M” framework (Summary). Front. Entrep. Res. 2010, 30, 2. Available online: https://digitalknowledge.babson.edu/fer/vol30/iss8/2/ (accessed on 17 February 2017).

- Brush, C. Research on women business owners: Past trends, a new perspective, and future directions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1992, 16, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisrich, R.D.; Brush, C. The woman entrepreneur: Implications of family educational, and occupational experience. In Frontiers of Entrepreneurial Research; Hornaday, J.A., Timmons, J.A., Vesper, K.H., Eds.; Babson College: Boston, MA, USA, 1983; pp. 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, P.G. Women entrepreneurs: Moving front and center: An overview of research and theory. Coleman White Pap. Ser. 2003, 3, 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Orhan, M.; Scott, D. Why women enter into entrepreneurship: An explanatory model. Women Manag. Rev. 2001, 16, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascher, J. Female Entrepreneurship—An Appropriate Response to Gender Discrimination. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2012, 8, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, J.; Gelderen, M.; Thurik, R. Entrepreneurial aspirations, motivations, and their drivers. Small Bus. Econ. 2008, 31, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaralli, N.; Rivenburgh, K.N. Entrepreneurial intention: Antecedents to entrepreneurial behavior in the U.S.A. and Turkey. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2016, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Doing Business 2008; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Salime, M.; Massimiliano, M.P.; Andrea, C.; Dianne, H.B.W. Entrepreneurial intentions of young women in the Arab world: Socio-cultural and educational barriers. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 880–902. [Google Scholar]

- Nissan, E.; Carrasco, I.; Castaño, M.S. Women Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Internationalization. In Women’s Entrepreneurship and Economics. International Studies in Entrepreneurship; Galindo, M.A., Ribeiro, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, K.D. Pushed or pull? Women’s entry into self-employment and small business ownership. Gend. Work Organ. 2003, 10, 433–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rametse, N.; Huq, A. Social influences on entrepreneurial aspirations of higher education students: Empirical evidence from the University of Botswana women students. Small Enterp. Res. 2015, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amentie, C.; Negash, E. The study on female undergraduates’ attitudes and perceptions of entrepreneurship development (comparison public and private universities in Ethiopia). J. Account. Mark. 2015, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Abebe, A. Attitudes of undergraduate students towards self-employment in Ethiopian public universities. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hattab, H. Towards understanding female entrepreneurship in Middle Eastern and North African countries: A cross-country comparison of female entrepreneurship. Educ. Bus. Soc. Contemp. Middle Eastern Issues 2012, 5, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamlou, N. The Environment for Women’s Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa Region; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Available online: https://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTMENA/Resources/Environment_for_Womens_Entrepreneurship_in_MNA_final.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2018).

- Booz and, Co. Women’s Employment in Saudi Arabia: A Major Challenge. 2010. Available online: http://www.booz.com/media/uploads/Womens_Employment_in_Saudi_Arabia.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2017).

- Allen, S.; Truman, C. Women in Business: Perspectives on Women Entrepreneurs; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.M.; Murad, M.W.; McMurray, J.A.; Turki, A. Aspects of sustainable procurement practices by public and private organizations in Saudi Arabia: An empirical study. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 24, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Vision 2030. Available online: http://vision2030.gov.sa/en/foreword (accessed on 21 October 2017).

- Bokhari, A. Entrepreneurship as a solution to youth unemployment in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Sci. Res. 2013, 87, 120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Labor and Social Development. Saudi Arabia Labor Market Report 2016, 3rd ed.; Ministry of Labor and Social Development: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S. Saudi Women Join the Workforce as Country Reforms. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2018/02/06/middleeast/saudi-women-in-the-workforce/index.html (accessed on 2 May 2018).

- Hechavarria, D.M.; Reynolds, P.D. Cultural norms and business start-ups: The impact of national values on opportunity and necessity entrepreneurs. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2009, 5, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsrud, A.L.; Brännback, M. Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2011, 49, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, A.G.I. Muslim women entrepreneurs’ motivation in SMEs: A quantitative study in Asia Pacific Countries. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2017, 7, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhaamie, A.G.A.; Rosmawani, C.H.; Siti, A.B.; Al-Banna, M.H. Motivation of Muslim women entrepreneurs in China SMEs: Towards trading halal goods and services. In Perpspektif Industri Halal Perkembangan Dan Isu-Isu; Suhaili, S., Mohd Abd. Wahab, F.M.B., Nor Azzah, K., Ahmad Sufyan, C.A., Eds.; University of Malaya Press: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2015; pp. 191–207. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, L.V.; Peter, R.V. Woman entrepreneurship in rural Vietnam: Success and motivational factors. J. Dev. Areas 2015, 49, 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, R.; Walsh, J. Characteristics of Thai women entrepreneurs: A case study of SMEs operating in Lampang Municipality Area. J. Soc. Dev. Sci. 2013, 4, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, S.S.; Che, S.Z.; Jani, F. An exploratory study of women entrepreneurs in Malaysia: Motivation and problems. J. Manag. Res. 2012, 4, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, C.G.; Cooper, S.Y. Female entrepreneurship and economic development: An international perspective. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2012, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Women, Business and the Law, 2014; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Available online: http://wbl.worldbank.org/~/media/FPDKM/WBL/Documents/Reports/2014/Women-Business-and-the-Law-2014-FullReport.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2017).

- Hashim, A.S.N.; Yaacob, R.M.; Muhayiddin, N.M. The environmental factors that influence success of women entrepreneurs: Entrepreneurial intention as a mediator. In Proceedings of the 4th International Seminar on Entrepreneurship and Business, Tanjung Bungah, Penang, Malaysia, 17 October 2015; Available online: http://umkeprints.umk.edu.my/5047/1/Conference%20Paper%2040%20%20ISEB%202015.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2017).

- Nematoollah, S.; Davoud, M.; Seyed, M. Entrepreneurial intention of agricultural students: Effects of role model, social support, social norms and perceived desirability. Arch. Appl. Sci. Res. 2012, 4, 892–897. [Google Scholar]

- Brophy, D.J. Financing women-owned entrepreneurial firms. In Women-Owned Businesses; Hagen, O., Rivchun, C., Sexton, D.L., Eds.; Praeger: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, J.D.; Brush, G.C.; Greene, G.P.; Litovsky, Y. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2012 Women’s Report; Global Entrepreneurship Research Association: London, UK, 2013; Available online: http://www.unirazak.edu.my/images/about/GEM_2012_Womens_Report.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2017).

- Nasser, K.; Mohammed, W.R.; Nuseibeh, R. Factors that affect women entrepreneurs: Evidence from an emerging economy. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2009, 17, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H. Creating an Enabling Environment for Women Entrepreneurship in India; United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific: Bangkok, Thailand, 2013; Available online: http://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/ESCAP-SSWA-Development-Paper_1304_1.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2017).

- Staniewski, M.; Szopiński, T. Influence of socioeconomic factors on the entrepreneurship of Polish students. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2013, 12, 163–179. [Google Scholar]

- Zain, M.; Kassim, N.M. The influence of internal environment and continuous improvements on firms’ competitiveness and performance. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 65, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, M.; Weezel, V.A. Media and entrepreneurship: A survey of the literature relating both concepts. J. Media Bus. Stud. 2012, 4, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.; Bosma, N.; Amoros, J. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2010 Report; Global Entrepreneurship Research Association: London, UK, 2011; Available online: http://www.av-asesores.com/upload/479.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2017).

- Rae, D. Entrepreneurship: From Opportunity to Action; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chlosta, S.; Patzelt, H.; Klein, S.B.; Dormann, C. Parental role models and the decision to become self-employed: The moderating effect of personality. Small Bus. Econ. 2010, 38, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. The Economics of Entrepreneurship; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Falck, O.; Heblich, S.; Luedemann, E. Identity and entrepreneurship: Do school peers shape entrepreneurial intentions? Small Bus. Econ. 2010, 39, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, R.; Sorensen, J. Workplace Peers and Entrepreneurship; Entrepreneurial Management Working Paper No. 08-051; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, G.M.; Grilli, L. On growth drivers of high-tech start-ups: Exploring the role of founders’ human capital and venture capital. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 610–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doms, M.; Lewis, E.; Robb, A. Local labour force education, new business characteristics, and firm performance. J. Urban Econ. 2010, 67, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, E.; Kerr, W.R.; O’Connell, S.D. Spatial Determinants of Entrepreneurship in India; NBER Working Paper 17514; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Glaeser, E.; Kerr, W.; Ponzetto, G. Clusters of entrepreneurship. J. Urban Econ. 2010, 67, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinsky, A.L.; Caputo, R.K.; Pasumaty, K.; Quanzi, H. The effects of education on business ownership: A longitudinal study of women entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1993, 18, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wong, P. Entrepreneurial interest of university students in Singapore. Technovation 2004, 24, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, K.; Ahmad, R.; Gadar, K.; Yunus, N. Stimulating factors on women entrepreneurial intention. Bus. Manag. Dyn. 2012, 2, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- De Kok, J.D.; Ichou, A.; Verheul, I. New Firm Performance: Does the Age of Founders Affect. Employment Creation? EIM: Zoetermeer, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gielnik, M.M.; Zacher, H.; Frese, M. Focus on opportunities as a mediator of the relationships between business owners’ age and venture growth. J. Bus. Ventur. 2012, 27, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, W. Informality revisited. World Dev. 2004, 32, 1159–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Lotti, F.; Mistrulli, P.E. Do women pay more for credit? Evidence from Italy. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2013, 11, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaroni, F.M.; Paoloni, P. Are family ties an opportunity or an obstacle for women entrepreneurs? Empirical evidence from Italy. Palgrave Commun. 2016, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.S. A case for comparative entrepreneurship: Assessing the relevance of culture. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2000, 31, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivetz, L. Private Enterprise and the State in Modern Nepal; Oxford University Press: Madras, India, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rønsen, M. The Family: A Barrier or Motivation for Female Entrepreneurship? Discussion Paper no. 727; Statistics Norway Research Department: Oslo, Norway, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, C.C.; Bostan, I.; Robu, B.; Maxim, A.; Diaconu, L. An analysis of the determinants of entrepreneurial intentions among students: A Romanian case study. Sustainability 2016, 8, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniewski, M.W.; Janowski, K.; Awruk, K. Entrepreneurial personality dispositions and selected indicators of company functioning. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1939–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naila, A.; Dahlan, M. Are Women Students More Inclined Towards Entrepreneurship? An Entrepreneurial University Experience. GSTF J. Bus. Rev. (GBR) 2013, 2, 90–103. [Google Scholar]

- Furdas, M.; Kohn, K. What’s the Difference?! Gender, Personality, and the Propensity to Start a Business; IZA Discussion Paper No. 4778; Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA): Bonn, Germany, 2010; Available online: http://anon-ftp.iza.org/dp4778.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2017).

- Krueger, N.; Brazeal, D.V. Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izraeli, D.N. Outsiders in the promised land: Women managers in Israel. In Competitive Frontiers: Women Managers in a Global Economy; Adler, N.J., Izraeli, D.N., Eds.; Blackwell Publishers: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 301–324. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Bañón, A.; Esteban-Lloret, N. Cultural factors and gender role in female entrepreneurship. Suma de Negocios 2016, 7, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H. Essentials of Studying Cultures; Pergamon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. Universities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://www.moe.gov.sa/en/pages/default.aspx (accessed on 21 October 2017).

- General Authority for Statistics. Census 2010; General Authority for Statistics: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2010. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/en (accessed on 21 October 2017).

- Scott, M.; Twomey, D. The long-term supply of entrepreneurs: Students career aspirations in relation to entrepreneurship. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1988, 26, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, S.; Rosa, P. The financing of male- and female-owned businesses. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1998, 10, 225–241. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, S. The role of human and financial capital in the profitability and growth of women-owned small firms. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2007, 45, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, A.; Ritchie, J. Understanding the process of starting small businesses. Eur. Small Bus. J. 1982, 1, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, A.B.; Smith, H.L. Female entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia: opportunities and challenges. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2009, 3, 216–235. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh, D.; Memili, E.; Kaciak, E.; Al Sadoon, A. Saudi women entrepreneurs: A growing economic segment. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieva, F. Social women entrepreneurship in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2015, 5, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, N.S.; Levie, J. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2009 Executive Report; Global Entrepreneurship Research Association: Wellesley, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]