Abstract

Work and paid employment has become a central aspect of social identity in our contemporary work societies. The assumed positive aspects of wage labour and employment on individual well-being are hardly questioned. It is instead claimed that work offers the individual a sense of purposefulness, a possibility to contribute to the collective good and a daily structure. Since its late emergence in the 1960s, the disability rights movement has put an emphasis on exclusion from work and employment. Nevertheless, all over the world, people with disabilities still belong to the most marginalised groups in the labour market. Using disability rights monitoring as a method, this paper explores what role the disability rights framework plays in shaping and transforming our present work society. Based on a German context, it is outlined how the international human rights framework has influenced the social policies that support the inclusion of disabled people in work and employment. Including the narratives of disabled people, it is outlined that despite comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation, the German labour market remains exclusionary and discriminatory against people with disabilities. Recently introduced measures, however, point to a new direction and aim to create a more equal and just world of work that acknowledges embodied differences and the needs and capabilities of disabled and non-disabled workers.

1. Introduction

The mainstream ethos that participation in the workforce is an important feature of modern European self-identity is commonly shared among people with and without disabilities [1,2,3]. The popular question “Who do you do for work?” in initial encounters reveals the predominant role of employment status in the formation of a valued social identity. The connection of identity with occupational status is not necessarily a universal experience. However, it is dominant in welfare states, in which social inclusion and the entitlement to social benefits is often closely linked to the economic participation of the individual [4]. In European social policy, the assumed positive aspects of employment and occupation on individual well-being are hardly questioned (see, for example, the European Disability Strategy 2010–2020 or the Employment Equality Framework Directive). It is instead claimed that employment and occupation are key elements that contribute to the full participation of citizens in economic, social and cultural life. Employment offers the individual a sense of purposefulness and a possibility to contribute to the collective good. The structure of paid work, with its working hours, reimbursement and tax systems, regulates and organises social interactions in complex societies [1,5].

In recent decades, such workfare approaches have not only changed citizenship norms, they have also shaped disability policies [3]. In many countries, disability benefits have been cut and active labour market policies have been promoted instead. Participation in employment and occupation has become a perquisite to receive social entitlements [6,7,8,9,10,11]. One aim of such policy developments is to minimise the “significant burden” disability benefits place on public finances [12] (p. 12).

Since its late emergence in the 1960s, the disability rights movement has put an emphasis on exclusion from work and employment. Adopting a Marxist materialist approach to history, scholars argue that the oppression of disabled people in modern societies can be traced back to the origins of Western industrial society and the social relations of production in capitalist societies. Due to exclusion from the ‘mode of production’, disabled people are excluded from mainstream social structures [13,14,15,16]. The United States and Canada were the first countries that responded to these claims, with initial introductions of scattered equality provisions in different areas of law. The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 is often described as a landmark law [17]. In the meantime, many states have followed and introduced comprehensive legislation that prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability inter alia in the area of employment. In Germany, the Act of Equalization of Persons with Disabilities (Behinderungsgleichstellungsgesetz (BGG)) came into force on 1 May 2002 and has only recently been reformed in July 2016. The first version of the BGG did not acknowledge that for disabled people to achieve de facto equality, different treatment and positive discrimination measures are often necessary [18] (p. 434). These issues have been addressed in the amendment of the BGG. The amendment in 2016 put the main emphasis on accessibility and extended the definition of discrimination. Within the new act, the denial of necessary social provisions and accommodations is also considered discriminatory; consequently, indirect discrimination is addressed. Nevertheless, the BGG only applies to the public sector and does not cover discrimination in working life. In Germany, discrimination in working life is addressed by the General Equality Act (Allgemeines Gleichbehandlungsgesetz (AGG)) and the Social Code Book IX (SGB IX). The employment discrimination obligation (§ 81 SGB IX) has been enacted with the intention to adopt the EU equality directive 2000/78/EG of 2000. However, § 81 does not fulfill the obligations of the EU equality directive. On the one hand, it only applies to persons who have been classified as severely disabled, and on the other hand, most of the obligations under § 81 only apply to people who are employed but not to unemployed people looking for a job [19,20,21]. Despite existing legislation, disabled people find themselves in a disadvantaged position in the German labour market. In 2016, the unemployment rate of severely disabled people was 12.4% compared to 6.1% for non-disabled people [22] (p. 161). Since 2007, the unemployment rate of severely disabled people has decreased by 5%, while the unemployment rate of non-disabled people has decreased by 25% [23]. A comprehensive Government report on the Participation of Disabled People outlines that the employment rate of both disabled men and women was 58% compared to 83% of non-disabled men and 75% of non-disabled women [24] (p. 130). Furthermore, the participation report of 2016 showed that only 40% of the people with an impairment claimed that their earnings were their main source of income, whereas 74% of the overall working age population sustained their living through employment [25] (p. 155).

Soldatic and Chapman argue that the disability movement has recently been weakened by trying to comply with the new workfare agenda. Service providers have been privatised in a neoliberal manner and funding schemes have increasingly focused on outcomes. As a consequence, the most ‘able of the disabled’ became the central focus of support measures [7] (p. 144). Such reforms are most effective for those that are already close to the labour market, but not to people with disabilities who have very limited labour market opportunities [8]. Disability scholars have further shown that policy approaches requiring participants to engage in the competitive labour market in exchange for social entitlements neglect discriminatory issues and the role of cultural and structural barriers such as inaccessible transportation or the lack of personal care support within workplaces [7,26]. Workfare approaches further undermine the changing nature of the world of work, the lack of suitable work opportunities and the pluralisation of life styles [6,8,9,26,27]. In contrast to current transnational and national strategies that put active labour market policies at their core (e.g., European Disability Strategy, German National Plan), disability advocates call for a dual strategy of “work facilitation for those who want it and can meaningfully take part in the labour process and the general valorisation of non-working lives for those including impaired people, who are unable to work” [3]. They argue that emphasis must shift from looking at the integral rather than the integrable nature of disability to human existence. Such a shift would require a reconceptualisation of the expectations of productivity based upon the divergent capacities of the individual and of the workday itself [28]. Such a recalibration would extend worth and identity to those systemically deprived from the labour market [29].

Using disability rights monitoring as a method, this paper explores what role the disability rights framework plays in shaping and transforming our present work society. Based on a German context, it is outlined how the international human rights framework has influenced social policies that support the inclusion of disabled people in work and employment. Including the narratives of disabled people, it is outlined that despite comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation, the German labour market remains exclusionary and discriminatory against people with disabilities. Recently introduced measures, however, point to a new direction and aim to create a more equal and just world of work that acknowledges embodied differences and the needs and capabilities of disabled and non-disabled workers.

2. Employment Policies and the Legal Framework for People with Disabilities in Germany

In Germany, active labour market policies for disabled people emerged at the beginning of the twentieth century. At the end of the First World War, a large group of injured war veterans seemed to have an unquestionably legitimate claim to the moral and financial support necessary for their reintegration into work and thus into society [30] (p. 3). Since 1917 German Unions have claimed an employment quota to support war veterans (“Kriegsinvaliden”). The government (Reichstag) introduced such an employment quota of 2% in 1918 for all employers who employed more than 50 workers. Reintegration into work became the main policy aim in regard to injured and disabled soldiers. A rehabilitation system, which was at that time one of the most advanced and best-organised in the world with its mixture of church and state-sponsored institutions and hospitals, strengthened this aim [30] (p. 9). The social policy agenda changed dramatically when in the years before the Second World War, social Darwinism and eugenic world views become dominant in Germany [31,32,33]. From 1933 until the end of the World War II, the National Socialists took power over Germany. Under the leadership of Adolf Hitler, they established a dictatorship and enforced their Nazi eugenics with the ultimate goal to improve the Aryan race. Besides Jews and Roma people, the Nazi regime persecuted people with disabilities. In particular, people with a mental disability and people suffering from an incurable illness were perceived as unworthy of living in the first place and as a burden to society in the second place. The murdering of such groups was therefore seen as a social duty to sustain the German race [33] (pp. 19–20) and releasing people from their suffering was described as an “act of mercy” [34]. Until the end of the Nazi regime, about 100,000 disabled people were killed and many more had become subject to forced sterilisation [31,32].

Although people with disabilities were amongst the group on whom the National Socialists attempted to enforce their distinctions between the sick and the healthy with the ultimate goal of eliminating the sick from the body of the German nation, the rights of people with disabilities have not found much response in both parts of the German post-war society [30]. After World War II, veterans did not have the same heroic status as after World War I and disability discourses were mainly influenced by a charity approach. In West Germany, the “Severely Injured People Act” (“Schwerebeschädigtenrecht”) was reformed and renamed the “Severely Disabled People Act” (“Schwerbebehindertengesetz”) in 1974. The Severely Disabled People Act has formed the basis of German disability policy ever since. For the first time in the German context, disability policies were extended to cover all severely disabled people, whatever the origin or nature of their disability [35] (p. 230). The new law modernised, amongst other things, the quota system and strengthened the rights of an ombudsman for disabled people. The Severely Disabled People Act of 1974 also introduced sheltered workshops in Germany. Sheltered workshops are by law obliged to offer people with a disability who are unable to work at least three hours a day in the open labour market the right to work in sheltered employment, for as long as they are able to produce ‘a minimum amount of economically useful work’ (SGB IX § 136). By legislation, work in a sheltered workshop needs to be adjusted to disabled people’s needs and abilities. In 1974 sheltered workshops were established to offer people with a mental disability an alternative form of employment. In the meantime, sheltered workshops are open to all disabled people who, on account of the nature or severity of their disability, cannot (yet) enter or re-enter the open labour market. In regard to Visier’s classification of the types of sheltered employment situations, Germany is grouped within the ‘intermediate model’, in which the disabled worker is perceived as a ‘quasi-employee’ [36] (p. 358). In sheltered workshops, disabled people who are admitted to sheltered workshops due to their incapacity to work in the open labour market and people who are regularly employed, such as supervisors and social workers, have a different employee status. Whereas regular employees earn a regular wage and are covered by national and EU labour law, disabled co-workers are by legislation considered as ‘quasi workers’ (§ 221 SGB IX). Consequently, they are not covered by national or EU labour laws and their reimbursement is very low (about 180 €/month). Although transition to the open labour market is the ultimate goal of sheltered workshops, the transition rate is very low (only 0.16% between 2002 and 2006 [37] (p. 111).

In West Germany, a broad rehabilitation system of special institutions emerged after World War II. Rehabilitation became the dominant paradigm and within the rehabilitation paradigm, work and integration into mainstream work and employment became a core goal supported by physicians, policy makers and researchers. However, this goal was mainly achieved through the rising number of admissions to segregated workshops. Whereas disabled people in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) often gained a high degree of material security, many of them were segregated in institutions and excluded from mainstream social structures [30,32]. Rights based approaches and/or a political consciousness only emerged in the 1980s due to supranational and international influences [38,39]. In contrast to the FRG, the Eastern parts of Germany, the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was influenced by socialist theories and practice from 1949 to 1990. In the Socialist State, the image of the ideal citizen was portrayed as a strong, healthy worker who can achieve economic justice for all through his/her individual productivity in socialist labour processes [40]. Based on the materialist perspective within the socialist worldview, all human beings were seen as fundamentally equal and largely shaped by their environment. Poore stresses that the concept of “performance” is crucial when discussing disability policy in the GDR. For disabled people, the predominant emphasis on performance had contradictory tendencies. On the one hand, the constant emphasis on individual performance in terms of work productivity resulted in broad efforts to rehabilitate people with disabilities and to integrate them in the labour force, but on the other hand, however, there was a constant pressure to perform, which also had an exclusionary effect on many disabled people who needed extra care and support and who were truly not able to work in existing industries [30] (pp. 249–250). Due to a lack of economic resources, less productive members of society were often housed in inappropriate aged care facilities or special institutions [41]. The absence of any discernible social and political lobbies for people with disabilities prevented a social push towards self-determination and participation until the end of the GDR in 1990 [40]. After the reunification process in 1990, most of the Western political and economic systems had been imposed on the former Eastern parts of Germany.

The first policy change after the reunification occurred in 2001, when the amendment of the Severely Disabled People Act took place. In order to standardise the various existing regulations and policies and to include the discrimination prohibition enshrined in Article 3 of the German Constitution, a new rehabilitation law—the Social Code Book No. 9 (SGB IX)—was introduced. The SGB IX inherited the definition of disability and the distinction between severely disabled and disabled people. According to § 2 SGB IX, persons are disabled if their physical functions, mental capacities or psychological health are highly likely to deviate for more than six months from the condition which is considered typical for the respective age and whose participation in the life of society is therefore restricted [19]. The effect of the functional impairment is labelled degree of disability (GdB). The GdB is measured in units of 10 on a scale from 20 to 100. People with a degree of disability of at least 50 are recognised as people with severe disabilities in the terms of the law.

Becoming the blueprint for the development of disability policies around the globe, the international human rights framework has recently influenced German disability policy. Germany signed the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with disabilities in 2007. The Convention came into force on 26 March 2009. Germany did not present any declarations, reservations or objections in relation to the UNCRPD and its Optional Protocol. In the German context, however, contradictions have emerged in regard to the official German translation. Article 50 of the CRPD states that the Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish texts of the present Convention shall be equally authentic and therefore these texts represent the initial purpose of the Convention. Several passages of the German translation have been subject to criticism by disability organisations and advocates. Due to this widespread criticism, a shadow translation has been published [42]. Overall, the negotiation process of the CRPD has been accompanied by the ongoing debate about the extent to which the CRPD is already implemented in German legislation. Whereas one group of researchers and policy makers argue that the CRPD has nothing new to offer as the German system already treats its disabled citizens as rights bearers and not as objects of charity [43], other scholars claim that the German system is still marked by segregation and a paternalistic welfare system and, therefore, is not in line with the human rights convention [39,44]. In regard to work and employment, the second group, in particular, condemns the widespread system of sheltered employment and the special education system. Furthermore, the English term “inclusive” and “inclusion” have been translated to “integrative” and “integration” in the official German translation. Scholars argue that the German translation is more compatible with the concept of “integration”. Consequently, the German translation does not reflect the original spirit of the Convention, which emphasises an inclusive labour market [45] (p. 108). Following this debate, the German term “Inklusion” is nowadays widespread in its use in policy discourses that address the inclusion of disabled people in work and employment and in education (see, for example, the “National Action Plan”, or the “Initiative Inklusion”). The ratification process has raised awareness among policy makers and the wider public. On 23 December 2016, a new disability law, the “Federal Participation Act” (“Bundesteilhabegesetz”)—a law for strengthening the participation and self-determination of people with disabilities—was signed to further strengthen the CRPD in the German system. The new law comes into force in four stages from 2017 until 2023. The Federal Participation Act (BTHG) amends the SGB IX and extends it to three parts: part one of the BTHG regulates rehabilitation benefits; part two includes integration supports; and part three consists of various provisions for the employment of severely disabled people.

The German system of employment support for disabled peopled is broad. Employment support includes various measures, such as inter alia anti-discrimination legislation, an employment quota for private and public employers, ombudsmen for severely disabled people, financial incentives to employers, work place adaptions, Work Assistance, Supported Employment and a special dismissal protection. Nevertheless, the bureaucratic procedures are highly complex and many of the measures in place (e.g., Work Assistance, Supported Employment, dismissal protection) are only available to people who are classified as severely disabled [46,47].

The monitoring obligation of the Convention (Article 33) requires State Parties not only to maintain, strengthen, designate or establish a human rights framework but also to monitor its implementation. As Pinto claims, human rights monitoring is the activity that enables societies to evaluate whether progress in securing rights has taken place and it further provides information about existing gaps [48]. Furthermore, the monitoring process is an important instrument to enhance public awareness and empower people affected by human rights violations. Monitoring, in this sense, is intended to bring about social change and the critical goal of disability rights monitoring is to contribute to the improvement of the human rights protection of disabled people [48] (pp. 455–456). The ultimate test for a legislation that aims to implement the CRPD is its “substantive effectiveness” [49]. “Substantive effectiveness” can be defined as the degree to which the legislation and the practical application of the measures at a national level produce a real positive change for disabled people [49]. Whereas political effectiveness can be analysed through documental analysis, formal and, in particular, substantive effectiveness require the inclusion of disabled people’s narratives. Exploring disability narratives in human rights discourses and monitoring projects, Titchosky argues that monitoring projects that use qualitative methods and include disabled people and their voices in the monitoring process offer the opportunity to influence the perceptions of what is perceived as human and who is considered as a citizen, or as a rights holder [50].

3. Methodology and the Research Participants

For the present study, semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted. The interviews were guided through a set of closed and open questions which were adopted from the Disability Rights Promotion International (DRPI) interview guideline. DRPI is a collaborative project that has established a comprehensive, sustainable, international system to monitor the human rights of persons with disabilities. Working in partnership with disability organisations, human rights experts, academics, and others advocating for equal rights, DRPI has developed monitoring tools and has trained persons with disabilities in all five continents to become monitors of disability rights [48] (pp. 451–478). The questions in the present study inquired about experiences in the context of work and employment. Participants were recruited through a mixed approach, combining the snowball technique, a sampling strategy recognised as able to reach difficult to access and marginalised groups [51] (pp. 62–63), and a statistically non-representative stratified sampling technique [52], which ensures that the participants represent maximum diversity in regard to the independent variables. The following three variables were considered relevant to the research: age, gender and type of disability. In total, 16 people with a disability were willing to participate in the study. Due to the limited availability of resources, both in economic and temporal terms, all interviews were conducted in the Southern part of Germany. While it is not claimed that findings from such a small sample can be generalised, it is believed that the analysis will outline, to a greater or lesser extent, the experiences other disabled people share across Germany. The final sample comprised of an adult population of both sexes aged between 22 and 63 years. Among the interviewees, there were nine female participants and seven male participants. Disability is a heterogeneous, intersectional and multi-dimensional phenomenon. People who are classified as disabled do not only differ in regard to their gender, age or racial background, but also in regard to the types and degrees of their impairments (body functions and structures) [53]. For the present study, the body functions and structures (impairments) were categorised according to four subcategories that are also outlined in Article 1 of the CRPD: (1) intellectual impairments, (2) physical impairments, (3) psycho-social/mental impairments, and (4) sensory impairments. All types of impairments were represented, with a higher prevalence of physical impairments (six participants) and the lowest prevalence of sensory impairments (two participants).

Depending on the experiences the interviewees shared with the interviewer, the major part of the interview guideline included less structured open-ended questions that allowed us to investigate issues and areas that came up during the interview process and that had not been thought about prior to the interviews [54] (p. 177). At the end of the interview guideline, a set of questions sought socio-demographic information, such as sex, age, income, and type of disability. Prior to the interviews, participants were informed about the purpose of the study. The interviews were only conducted with the informed consent of the participant and in an accessible mode. On average, the interviews lasted about an hour and were recorded in full. Before analysing the interview, the audio material was transcribed anonymously to protect participants’ identity. The data collected through the in-depth interviews, the de facto data, was integrated in a coding scheme. The present research used NVivo 10, computer software also used by the DRPI project to code and organise information from the individual interviews. The purpose of coding is to convert qualitative data into quantifiable data that offers the possibility for comparative methods [55] (p. 102). For the data analysis, the human rights principles, “dignity”, “autonomy”, “participation, inclusion and accessibility”, “non-discrimination and equality”, and “respect for difference” were used as an underlying framework to critically assess individual experiences [56] (p. 3). Dignity refers to the inherent worth of every person. The code was applied whenever study participants felt respected and valued in their own experiences and opinions without fearing physical, psychological and/or emotional harm [57] (p. 20). Autonomy means that a person is able to make his or her own choices independently or with assistance and support. The lack of opportunities and alternative choices due to limited or no adequate information is also considered a violation to the principle of autonomy [18,57]. Inclusion is the right of all persons to participate fully and effectively in society. If persons with disabilities are absolutely prevented from participating in an event or activity due to accessibility restrictions, the situation was coded as a violation to the right of inclusion or exclusion [57] (p. 21). Although physical barriers such as inaccessible public transportation systems are the most obvious restrictions to full participation, spatial exclusion is only one aspect. Discriminatory attitudes and paternalistic worldviews in which disabled people are perceived as inferior also facilitate social exclusion and were coded as such [58]. Discrimination and non-equality occurs when any distinction, exclusion or restriction on the basis of disability denies the effective recognition, enjoyment or exercise of human rights and basic freedoms on an equal basis with others. The code of discrimination was applied whenever a study participant experienced a different negative treatment on the basis of his/her disability, either directly or indirectly. In the context of disability, formal equality, which means to treat all human beings equal regardless of their human characteristics, often puts disabled people in a disadvantaged position because reasonable accommodation and accessibility is not provided [17]. Such formal equality was coded as discrimination and inequality. Closely connected with the principle of non-discrimination and equality is the principle of ‘respect for difference’ and the promotion of diversity. Respect for difference involves recognising and accepting persons with disabilities as part of human diversity. It includes having disability-related needs properly addressed. Whenever a person is labelled, judged and/or insulted on the basis of certain assumptions that others make about his/her disability, a violation to the diversity principle occurs [57] (p. 22).

4. Individual Experiences in Germany—Disabled People Caught between Undignified Work in Sheltered Employment and a Discriminatory Open Labour Market

In regard to occupation status, the majority of participants (nine persons) were working in sheltered employment; the remaining seven participants had a paid occupation in the open labour market at the time of the interview. Comparing occupation status with the type of disability, there was a correlation between the type of disability and occupation status. All participants who had an intellectual or a psycho-social disability worked in sheltered employment. In contrast, five out of the six participants with a physical disability and all participants with a sensory disability had a paid occupation in the open labour market. These results are consistent with official figures regarding people working in sheltered workshops. In 2012, 77.49% of people who were employed in sheltered workshops had an intellectual disability, 19.18% had a psycho-social disability and only 3.33% had a physical disability. The sample further indicated that academic qualifications connect with occupation status. In Germany, a well-established infrastructure of special schools exists which provide special schooling for children with disabilities. In general, special schools are further differentiated into schools for people with learning/intellectual impairments and students with sensory impairments. Special schools are adapted to the needs of their students. In general, there are fewer students in class, the teachers are trained and technical equipment is provided. Although the school laws of most Federal States provide the opportunity for inclusive schooling, inclusive education is granted only if a ‘disproportionate burden’ is avoided. The aim in any special school is the completion of a mainstream secondary school certificate. Students who are not able to achieve this goal due to their disability can gain a special education degree after year nine or ten. In Germany, the special education degree is of less value than a regular certificate of students completing year nine or ten of mainstream schooling. Only one research participant with a special education degree was working in the open labour market. Of the nine interviewees who worked in sheltered employment, five had a special education degree, one had no degree, two completed the first cycle (primary school) and one interviewee was attending middle school (until year 10). These numbers indicate that for many people attending special schools (in particular, people with intellectual disabilities) the only possibility to participate in working life seems to be in sheltered employment. For many years, this one-way route has been subject to widespread criticism. A comprehensive study about the ‘development of the admission numbers of sheltered workshops’ conducted in 2006 revealed that around 41% of the people who started working in a sheltered workshop were admitted directly from a special school and the majority of this group had an intellectual disability [37] (p. 7). Two of the five interviewees with an intellectual disability had been directly admitted from a special school to a sheltered workshop. The ISB gGmbH report further revealed that the majority of people who have been working in the open labour market prior to their admission to a sheltered workshop have a psycho-social disability [37] (p. 9). Two of the three interviewees who had a psycho-social disability had been working in the open labour market prior to their admission to a sheltered workshop. These two participants disclosed that prior to their admission to the sheltered workshop they both experienced long periods of unemployment, in which they were undergoing medical treatments and diverse rehabilitation therapies.

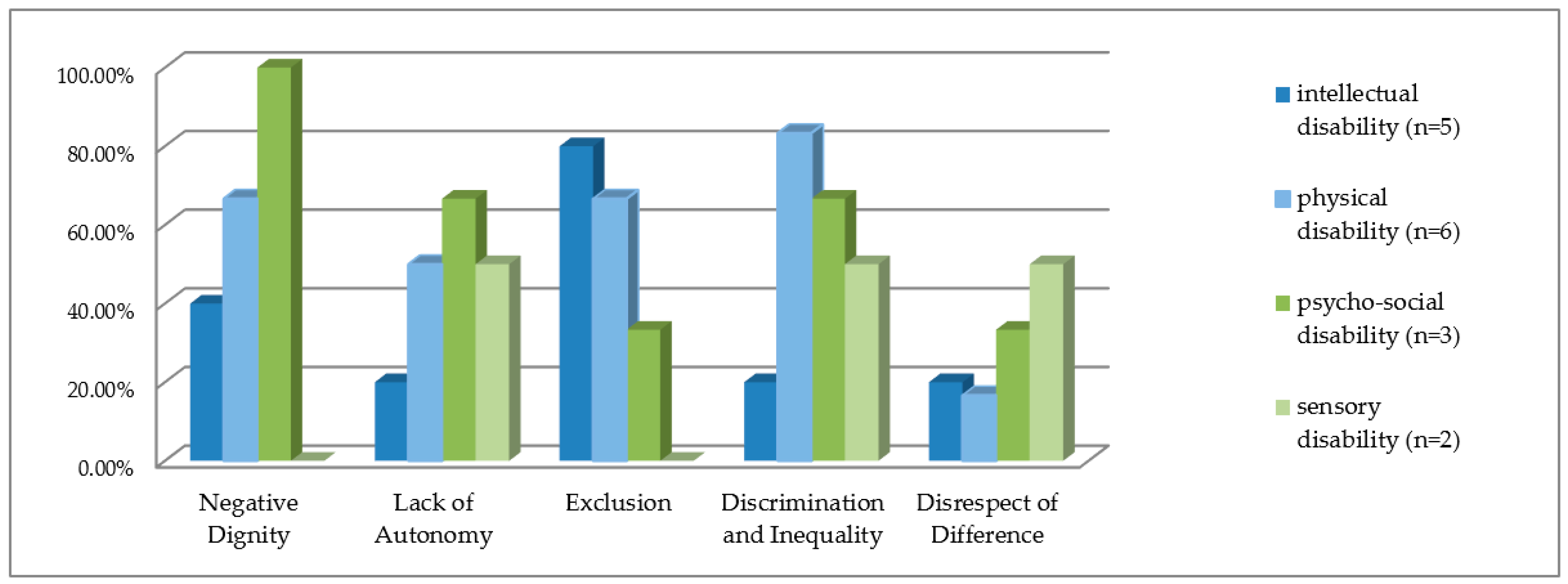

Considering human rights principles, all participants reported at least one situation related to work and employment in which they felt that human rights principles were protected or violated. None of the interviewees experienced violations in regard to all five principles; however, three participants reported that four out of the five human rights principles considered in this study had been violated. Six participants reported that three human rights principles had been violated. Depending on the type of disability, the experienced human rights implications differed to a great extent; while people with an intellectual disability reported a high prevalence of exclusion (four out of the five interviewees), people with a physical disability reported the highest prevalence of feeling discriminated against (five out of six interviewees) (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1.

Relative distribution of Human Rights violations by type of disability.

If we compare the source of income and occupation status, one result stands out. All participants working in a sheltered workshop depended on additional sources of income. While six out of the seven participants who worked in the open labour market had a sustainable income, all participants who worked in sheltered workshops depended on additional support in the form of welfare or pension payments. One participant outlined their difficult financial situation as follows:

“You have to survive from month to month. Sometimes, I think this is really depressing and there is no hope that this circumstance might change in the future” (female, 58 years old, psycho-social disability, working in a sheltered workshop)

The results indicate that work in a sheltered workshop does not comply with the concept of decent work [59] and article 27 of the CRPD, which outlines that the right to work includes the right to the opportunity to gain a living by work.

The fact that all interviewees with a psycho-social disability experienced a situation in the context of sheltered employment in which they felt that their dignity had been violated sustains the argument that sheltered employment probably implies undignified work. The experiences of the study participants with a psycho-social disability who felt disrespected and devalued in the context of sheltered work was caused by the organisation and structure of sheltered workshops. In sheltered workshops, disabled co-workers (disabled people who are admitted to sheltered workshops due to their incapacity to work in the open labour market) and people who work in the sheltered workshops as regular employees (such as supervisors, social workers etc.) have a different employee status. Whereas the regular employees earn a regular wage and are covered by national and EU labour law, disabled co-workers are by legislation considered as ‘quasi-workers’ (§ 221 SGB IX). Consequently, they are not covered by national or EU labour law and reimbursement is very low. The feeling that comes along with such a differentiation was described by one female participant as follows:

“… I feel a bit as a second class human being… [pause] it’s not just me having such a feeling, many [co-workers] feel the same” (female, 58 years, psycho-social disability, working in a sheltered workshop)

The interviewee outlined that her feeling of being of less worth was linked to the fact that, whereas non-disabled employees, such as supervisors and social workers, have an extra room where they can make coffee or tea during breaks, disabled workers have no such facilities and the disabled co-workers are not allowed to use the same room as their supervisors. Hurt feelings, low self-esteem, lack of confidence, depression and sadness were also caused by the type of work disabled co-workers had to undertake in a sheltered workshop, as another interviewee with a psycho-social disability described:

“It is extremely difficult for me to sit the whole day during work and to do always the same monotone tasks. I am not getting motivated and I do not have the feeling that I am needed. You just do your tasks and this is extremely boring…” (male, 48 years, psycho-social disability, working in a sheltered workshop)

The interviewee defined his work as monotone and boring, because he has to always do the same tasks. Furthermore, he has no control about the work tasks he is obliged to do. Hence, the work is not giving him a sense of purposefulness and he is not challenged by the work he is doing. The fact that monotone work often causes undignified work conditions has already been outlined in the context of industrial labour processes [60].

Additionally, exclusion was most predominant among people with an intellectual disability (see graph above). Four out of five participants with an intellectual disability reported situations in which they felt excluded. These experiences were in two cases directly linked to the segregated nature of sheltered workshops: in one case, the bus that takes the participant to the sheltered workshops was not a regular public bus, but a specific bus which stigmatises the passengers as different. For this participant, this caused discrimination and led to the feeling that he was excluded from wider society:

“There is a sign on the bus showing the name of the organisation [organisation for disabled people]. Hence people know that the passengers of the bus are working in a sheltered workshop. There are some youths who harass and stigmatise us” (male, 38 years, intellectual disability, working in a sheltered workshop)

As Reeve claims, such types of support (e.g., special buses) create additional psycho-emotional barriers, which maintain social exclusion and isolation [61] (p. 104). In another case, the direct admission from a special school to a sheltered workshop was described as a structural barrier that prevented inclusion into mainstream support measures and the open labour market:

“When we finished school (special education school), all my friends went to the closest sheltered workshop, so I went there too” (female, 28 years old, intellectual disability, working in a sheltered workshop)

The interviewee lacked the relevant information about alternative options. At the time, when she finished her special school education in 2010, she wanted to work in the open labour market as a storekeeper or in a similar position. However, she thought she had no possibility of working in the open labour market. She was not given any relevant information about exiting support measures, which were rare at that time. She was instead admitted to the closest sheltered workshop, as were all her other classmates. Furthermore, two out of the three persons with a psycho-social disability disclosed that their admission to a sheltered workshop was not a voluntary decision but one that was forced by a shortage of alternatives and connected support mechanisms in the open labour market. One situation clearly reflected a lack of autonomy:

“If I would have refused to go to a sheltered workshop, then my legal guardian wouldn’t have organised to get me out of the care facility” (female, 58 years old, psycho-social disability, working in a sheltered workshop)

The narratives show that the open labour market in Germany is not accommodating and welcoming for people with disabilities. In particular, people with intellectual and psycho-social disabilities experience widespread exclusion. Sheltered workshops often function as an alternative to unemployment. Discriminatory attitudes, however, were also reported by interviewees working in the open labour market. A violation to the principle of discrimination was most prevalent among people with a physical impairment (five out of six interview partners). In two cases, the discrimination took place during the application process. Both reported discriminations were shared by participants who were wheelchair users:

“I even received a rejection letter with a note saying that there are special institutions for people with severe disabilities. The addresses of these institutions were enclosed in the letter…” (female, 35 years old, physical disability, working in the open labour market)

Another one disclosed:

“I was invited to a pre-interview and I didn‘t feel comfortable. Many people participated in this pre-interview and they wanted to know a lot about my disability. Even the company doctor was involved, he studied my medical reports. There was a lot of uncertainty amongst the decision makers. They were not sure if things would work out. They told me that the building was inaccessible and they offered me another position instead. However, the condition was that I had to do an internship of two weeks. The internship was meant to show if I could do the work or not…” (male, 22 years old, physical impairment, working in the open labour market)

The fact that their disability was visible played a role in the reported situations. In Germany, discrimination on the basis of disability is prohibited by the Constitution and under the Act of Equalization of Persons with Disabilities. The Act of Equalization of Persons with Disabilities (Behinderungsgleichstellungsgesetz (BGG)) came into force on 1 May 2002 and was reformed in July 2016. Although the BGG was celebrated as a milestone by the German disability movement for equality, Degener outlines that the original document which was drafted by the Forum of Disabled Lawyers was substantially altered by the government before it came into force [19]. The BGG adopted the same definition of disability as enshrined in § 2 of the Social Code Book IX (see above). In contrast to the non-discrimination and equality definition of the CRPD, the initial non-discrimination definition of the BGG neglected the fact that formal equality often leaves disabled people in a disadvantaged position [62] (pp. 448–449). The first version of the BGG did not acknowledge that for disabled people to achieve de facto equality, different treatment and positive discrimination measures are often necessary [18] (p. 434). These issues have been addressed in the amendment of the BGG. The amendment in 2016 put the main emphasis on accessibility and extended the definition of discrimination. Within the new act, the denial of necessary social provisions and accommodations is also considered discriminatory and, consequently, indirect discrimination is addressed. Nevertheless, the BGG only applies to the public sector. Public buildings, for example, need to be made accessible; the private sector and hence the majority of businesses and enterprises have no obligation under the BGG. Furthermore, discrimination in working life is not covered by the BGG. In Germany, discrimination in working life is addressed by the General Equality Act [Allgemeines Gleichbehandlungsgesetz, AGG] and the Social Code Book IX [SGB IX]. Under § 81 SGB IX, public employers have a legal obligation to invite an applicant to a job interview if the applicant discloses that s/he has a severe disability. There is no such obligation for private enterprises. The employment discrimination obligation (§ 81 SGB IX) was enacted with the intention to adopt the EU equality directive 2000/78/EG of 2000. However, § 81 does not fulfill the obligations of the EU equality directive. On the one hand, it only applies to persons who have been classified as severely disabled, and on the other hand, most of the obligations under §81 only apply to people who are employed but not to unemployed people looking for a job [19,20,21]. As the narratives show, legislation also proved ineffective in the case of the 22 years old wheelchair user who rejected the offer to do an internship. Only one interviewee—the one who received the rejection letter stating that there are special institutions for disabled people—made a legal claim under anti-discrimination legislation. Although at the end she won the case and the company was forced to offer her the position, she declined the job offer, as she no longer felt comfortable to work with the people who discriminated against her.

The same interviewee reported that the quota system played a positive role in helping her to get a contract with another company:

“One reason [to employ me] was probably the fact that the company wants or has to fulfil its obligation under the quota law […] I think the quota enforces the employment of disabled people in the open labour market. Without the quota this wouldn’t be the case… I am convinced that if there wouldn’t be a quota system, less disabled people would be employed” (female, 35 years, physical disability, working in the open labour market)

Another interviewee who also functioned as an ombudsman disclosed:

“In every interview or even prior to the interview, the applications are gone through to find applications of persons with a severe disability. These applications are definitely promoted” (female, 60 years, physical disability, working in the open labour market)

The quota law in Germany applies to both public and private employers. However, it is only applicable to companies who employ at least twenty people. While the quota might support that people with a disability are promoted in the application process, the quota cannot prevent that discriminatory attitudes are still widespread. One interviewee with a physical impairment experienced such a discriminatory attitude during an internship she was doing in the open labour market:

“Everyone is friendly, but there is a psychological barrier… They [colleagues in the shop she is doing an internship] do not dare to ask me something.” (female, 37 years old, physical disability, working in a sheltered workshop)

Psychological barriers, often caused by the common fear of disability [16] (p. 155), were also described by another interviewee as the source of discriminatory attitudes:

“Everyone says, he is having MS [Multiple Sklerosis] and many are afraid of this, because they don’t know anything about this kind of illness…” (male, 36 years old, physical disability, working in the open labour market)

The low prevalence of reported discriminatory attitudes amongst people with an intellectual disability (only one out five interviewees) is closely connected to their employment in a sheltered workshop. Sheltered workshops are by law obliged to offer people with disability who are unable to work in the open labour market the right to work in sheltered employment for as long as they are able to produce ‘a minimum amount of economically useful work’ (SGB IX § 136, para. 2). By legislation the work in the sheltered workshop needs to be adjusted to disabled people’s needs and abilities, and people in sheltered workshops have the right to work part-time if this is beneficial to their physical and psychological well-being. In contrast, work in the open labour market is often not considerate of disabled people’s needs. Inflexible work arrangement and insufficient or lacking support systems, as well as inaccessible environments, such as inaccessible public transportation, emergency and fire doors were repeatedly reported as barriers that hinder their full inclusion.

5. Discussion

Surprisingly, it was not the most frequent request for legislative or economic change that was made by the participants, but the call for more respect and increased disability awareness among employers, colleagues and the general public. As several study participants disclosed, the disability ombudsman in companies plays an important role; having someone who supports you in your fight for equal enjoyment and access rights serves as a source of mutual support, something several interview participants demanded. Disability ombudsmen also strengthen what Hall and Wilton have framed as the “collective action” of disabled people in the open labour market [63] (pp. 870–882). Furthermore, the narratives show that a supportive environment which is considerate of disabled people needs also requires some protection mechanisms to ensure that disabled people are not subject to arbitrary behaviours. Specific legislation, such as the quota law or the right to return to sheltered employment, is required to protect disabled workers and job applicants.

The reported stories show that the present open labour market is, despite broad anti-discrimination legislation, exclusionary and discriminatory against people with disabilities. In particular, people with intellectual and psycho-social disabilities experience widespread exclusion. While the system of sheltered workshops offers, on the one hand, an alternative form of employment that is considerate of disabled people’s needs and that values social participation over individual productivity, on the other hand, it strengthens the segregation of disabled people. The UN CRPD clearly rejects the concept of forced separation of disabled people in sheltered/segregated employment [64] (p. 31). The ratification of the Convention thus requires the German government to revise its sheltered employment system [65] (pp. 8–9). The German government has responded with the recently introduced Federal Participation Act. The new Act does not abolish but confronts the system of sheltered workshops in many aspects. A main aim of the Participation Act is to support and sustain alternative forms of employment in the open labour market. Several measures have been introduced to achieve this aim. For example, up until 2017, people who were working in sheltered workshops risked losing their incapacity pensions if they attempt to make a transition into the open labour market. In Germany, people who are unable to work at least three hours a day in the open labour market due a disability are entitled to an incapacity pension if they have paid contributions to the pension scheme previously. The amount of the incapacity pension depends on previous contributions and working years. Additionally, people who have been working in sheltered workshops for at least twenty consecutive years are entitled to an incapacity pension. In the past, transition to the open labour market also meant the risk of losing such pension entitlements. The BTHG includes a provision that people with disabilities have the right to return to sheltered workshops if their transition to the open labour market is unsuccessful. Additionally, Supported Employment is further promoted to interrupt the direct admission from special education settings to sheltered workshops. The newly introduced “Job Budget” enables people who are entitled to work in sheltered employment to receive a cash benefit that empowers them to pay up to 75% of gross income to an employer if the employer provides them with employment in the open labour market. This measure is a first step to create a “social labour market” [66]. Recent legislative changes acknowledge that the current labour market is still based on an able-bodied norm and that long-term measures are needed to facilitate the inclusion of people who have been historically excluded from labour processes. Measures such as Supported Employment and the Job Budget confront values which are traditionally associated with wage labour. At the core of the recently introduced measures lies not the aim to achieve maximum individual productivity, but to achieve maximum social participation through the provision of financial, personal and structural support. However, it remains to be seen if the measures will be effective [49]. The present analysis has shown that it is still a long way to go for disabled people to achieve equal status in the open labour market.

As outlined above, the world of work through the lens of disability requires a discourse in which values generally associated with waged labour such as independence, self-reliance, productivity and mainstream work arrangements need to be altered. To achieve real change, the voices of disabled people need to be heard. This paper argues that the international disability human rights framework provides a tool of empowerment and change as the monitoring obligation of the CRPD gives a voice to people with disabilities. People with disabilities who, due to their individual needs and capabilities are unable to comply with the current world of work, might take a leading role in creating an inclusive and social labour market. Unquestionably, such an alternative labour market needs to be seen in global terms. All over the world, workers are confronted with diminishing security and standardisation of work processes [1]. Nowadays, as work-centred societies are losing their central meaning [1], work often means a life on the margins of poverty for many social groups [67] (p. 82). Social policies that support and accommodate more just, equal and inclusive ontologies of work not only increase the inclusion of people with disabilities, but provide new perspectives for everyone.

Acknowledgments

This study received no funding. The cost associated with publishing this article as open access was provided through researcher funds.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Beck, U. The Brave New World of Work; Polity Press: Malden, MA, USA, 2001; ISBN 0-7456-2398-0. [Google Scholar]

- Galer, D. Disabled Capitalists: Exploring the Intersections of Disability and Identity Formation in the World of Work. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2012, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abberley, P. Work, Disability, Disabled People and European Social Theory. In Disability Studies Today; Polity Press: Malden, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 120–138. ISBN 978075626574. [Google Scholar]

- Bussemaker, J. Citizenship and changes in life-courses in post-industrial welfare states. In Citizenship and Welfare State Reform in Europe; Bussemaker, J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 71–84. ISBN 0-415-18927-6. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, H. Vita Activa Oder Vom Tätigen Leben, 6th ed.; Piper: München, Zürich, 2007; ISBN 9783492236232. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J. Rethinking disability policy. Viewpoint. 2011. Available online: https://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/default/files/jrf/migrated/files/disability-policy-equality-summary.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2014).

- Soldatic, K.; Chapman, A. Surviving the Assault? The Australian Disability Movement and the Neoliberal Workfare State. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2010, 9, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R.; Harris, S.P. “No Rights without Responsibilities”: Disability Rights and Neoliberal Reform under New Labour. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2012, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittig-Kope, H.; Bremer, F.; Hansen, H. Teilhabe in Zeiten verschärfter Ausgrenzung? Kritische Beiträge zur Inklusionsdebatte; Paranus Verlag: Neumünster, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978-3-940636-10-2. [Google Scholar]

- Schlund-Vials, C.J.; Gill, M. Disability, Human Rights and the Limits of Humanitarianism; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4724-2091-6. [Google Scholar]

- Soldatic, K.; Meekosha, H. The Place of Disgust: Disability, Class and Gender in Spaces of Workfare. Societies 2012, 2, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers; A Synthesis of Findings Across OECD Countries; OECD: Paris, France, 2010; ISBN 978-92-64-08884-9. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, M.; Barnes, C. The New Politics of Disablement, 2nd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Houndmills/Basingstoke/Hampshire, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-333-94567-4. [Google Scholar]

- Abberley, P. The Concept of Oppression and the Development of a Social Theory of Disability. Disabil. Handicap Soc. 1987, 2, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, V. Attitudes and Disabled People; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, P. Stigma: The Experience of Disability; Geoffrey Chapman: London, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, G.; Degener, T. A Survey of International, Comparative and Regional Disability Law Reform. In Disability Rights Law and Policy: International and National Perspectives; Transnational: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 3–129. [Google Scholar]

- Welti, F. Behinderung und Rehabilitation im Sozialen Rechtsstaat. Freiheit, Gleichheit und Teilhabe Behinderter Menschen; Mohr Siebeck: Tübingen, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Degener, T. The Definition of Disability in German and Foreign Discrimination Law. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2006, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deinert, O.; Neumann, V. Rehabilitation und Teilhabe Behinderte Menschen, 2nd ed.; Handbuch SGB IX; Nomos: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3-8329-3937-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ritz, H.-G. Besondere Regelungen zur Teilhabe schwerbehinderter Menschen. In SGB IX–Kommentar zum Recht Schwerbehinderter Menschen: Und Erläuterungen zum AGG und BGG; Vahlens Kommentare; Jung, K., Cramer, H., Fuchs, H., Hirsch, S., Ritz, H.-G., Eds.; Vahlen: München, Germany, 2011; pp. 425–486. ISBN 978-3-8006-2953-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesagentur für Arbeit. Arbeitsmarkt 2016; Bundesagentur für Arbeit Statistik: Nürnberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesagentur für Arbeit Statistik. Situation Schwerbehinderter Menschen; Blickpunkt Arbeitsmarkt; Bundesagentur für Arbeit Statistik: Nürnberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales (BMAS). Teilhabebericht der Bundesregierung über Die Lebenslagen von Menschen mit Beeinträchtigungen. Teilhabe–Beeinträchtigung–Behinderung; Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales: Bonn, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales (BMAS). Teilhabebericht der Bundesregierung über Die Lebenslagen von Menschen mit Beeinträchtigungen; Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales: Bonn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, C. “Work” is a four letter word? In Working Futures: Policy, Practice and Disabled People’s Employment; University of Sunderland, Cornell University ILR School Disability: Tyne and Wear, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cattacin, S.; Gianni, M.; Mänz, M.; Tattini, V. Workfare, citizenship and social exclusion. In Citizenship and Welfare State Reform in Europe; Bussemaker, J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 59–70. ISBN 0-415-18927-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, D.T. Foreword. In A History of Disability; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2002; pp. vii–xiv. ISBN 978-0-472-11063-6. [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor, M. Citizenship in Name Only: Constructing Meaningful Citizenship through a Recalibration of the Values Attached to Waged Labor. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2012, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poore, C. Disability in Twentieth-Century German Culture; Corporealities; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-472-11595-2. [Google Scholar]

- Burleigh, M. Tod und Erlösung. Euthanasie in Deutschland 1900–1945; Pendo: Zürich, Switzerland; München, Germany, 2002; ISBN 978-3-85842-485-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fandrey, W. Krüppel, Idioten, Irre. Zur Sozialgeschichte Behinderter Menschen in Deutschland; Silberburg-Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 1990; ISBN 978-3-925344-71-8. [Google Scholar]

- Klee, E. “Euthanasie” im NS-Staat. Die “Vernichtung lebensunwertes Lebens”; S. Fischer Verlag: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1983; ISBN 978-3-596-24327-3. [Google Scholar]

- Binding, K.; Hoche, A. Die Freigabe der Vernichtung Lebensunwertes Leben. Ihr Maß und ihre Form; Verlag von Felix Meiner: Leipzig, Germany, 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Waddington, L. Disability, Employment and the European Community; Maklu: Antwerpen, Belgium; Apeldoorn, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Visier, L. Sheltered employment for persons with disabilites. Int. Labour Rev. 1998, 137, 347–365. [Google Scholar]

- Detmar, W.; Gehrmann, M.; König, F.; Momber, D.; Pieda, B.; Radatz, J. Entwicklung der Zugangszahlen zu Werkstätten für Behinderte Menschen; ISB gGmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bielefeldt, H. Zum Innovationspotenzial der UN-Behindertenrechtskonvention; Deutsches Institut für Menschenrechte: Berlin, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3-937714-80-6. [Google Scholar]

- Graumann, S. Von einer Behindertenpolitik der Wohltätigkeit zur Politik der Menschenrechte: Die neue UN-Konvention für die Rechte von Menschen mit Behinderungen. Behinderung ohne Behinderte? Perspektiven der Disability Studies; Universität Hamburg: Hamburg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barsch, S. Bildung, Arbeit und geistige Behinderung in der DDR–zwischen Anspruch und Wirklichkeit. Dtschl. Archiv 2008, 41, 480–487. [Google Scholar]

- Fulbrook, M. The People’s State. East German Society from Hitler to Honecker; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Übereinkommen über die Rechte von Menschen mit Behinderungen. Available online: http://www.nw3.de/attachments/article/93/093_schattenuebersetzung-endgs.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2018).

- Luthe, E.-W. Behindertenrechtkonvention–viel Lärm um nichts. In Rechtliche Aspekte inklusiver Bildung und Arbeit. Die UN-Behindertenrechtskonvention und ihre Umsetzung im deutschen Recht; Küstermann, B., Eikötter, M., Eds.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 40–54. ISBN 978-3-7799-3243-7. [Google Scholar]

- Degener, T. Die UN-Behindertenrechtskonvention als Inklusionsmotor. RdJB 2009, 57, 200–219. [Google Scholar]

- Trenk-Hinterberger, P. UN-BRK und Teilhabe am Arbeitsleben. In Rechtliche Aspekte inklusiver Bildung und Arbeit. Die UN-Behindertenrechtskonvention und ihre Umsetzung im deutschen Recht; Küstermann, B., Eikötter, M., Eds.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 105–131. ISBN 978-3-7799-3243-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung, Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung, Institut Arbeit und Technik (ZEW; IAB; IAT). Evaluation der Maßnahmen zur Umsetzung. Arbeitspaket 1: Wirksamkeit der Instrumente. Modul 1d: Eingliederungszuschüsse und Entgeltsicherung; Gelsenkirchen und Mannheim: Nürnberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brussig, M.; Schwarzkopf, M.; Stephan, G. Eingliederungszuschüsse: Bewährtes Instrument mit zu Vielen Varianten; Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung (IAB) der Bundesagentur für Arbeit: Nürnberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, P.C. Monitoring Human Rights: A Holistic Approach. In Critical Perspectives on Human Rights and Disability Law; Basser, L.A., Jones, M., Rioux, M.H., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 451–478. ISBN 978-90-04-18958-4. [Google Scholar]

- Gubbels, A. The legislative phase of the implementation of the UNCRPD 2017. In EU Disability Law and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; ERA, Academy of European Law: Trier, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Titchosky, T. Monitoring Disability: The Question of the “Human” in Human Rights Projects. In Disability, Human Rights and the Limits of Humanitarianism; Gill, M., Schlund-Vials, C.J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Arber, S. Designing Samples; Gilbert, N., Ed.; SAGE Publication: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India, 2001; pp. 58–84. [Google Scholar]

- Trost, J.E. Statistically nonrepresentative stratified sampling: A sampling technique for qualitative studies. Qual. Sociol. 1986, 9, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickenbach, J.E. The international Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health and its relationship to disability studies. In Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies; Watson, N., Roulstone, A., Thomas, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hopf, C. Qualitative Interviews in der Sozialforschung. Ein Überblick. In Handbuch Qualitative Sozialforschung. Grundlagen, Konzepte, Methoden und Anwendungen; Flick, U., Kardorff, E.V., Keupp, H., Rosenstiel, L.V., Wolff, S., Eds.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1995; pp. 177–181. ISBN 978-3-621-27229-2. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967; ISBN 0-202-30260-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rioux, M.H.; Basser, L.A.; Jones, M. Critical Perspectives on Human Rights and Disability Law; Martinus Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-90-04-18950-8. [Google Scholar]

- Disability Rights Promotion International (DRPI). A Guide to Disability Rights Monitoring, Participant Version; York University: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stichweh, R. Inklusion/Exklusion, funktionale Differenzierung und die Theorie der Weltgesellschaft. In Große Armut, großer Reichtum. Zur Transnationalisierung sozialer Ungleichheit; Suhrkamp: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organisation. Decent Work Indicators. Concepts and Definitions; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; ISBN 78-92-2-126425-5. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, A. Die Würde des Menschen Inder Arbeitswelt; Europäische Verlagsanstalt: Kiel/Hannover/Hamburg, Germany, 1969; ISBN 978-3-434-10077-5. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve, D. Part of the problem or part of the solution? How far do ‘reasonable adjustments’ guarantee ‘Inclusive Access for Disabled Customers’? In Disability, Spaces and Places of Policy Exclusion; Soldatic, K., Morgan, H., Roulstone, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales (BMAS). Evaluation des Behindertengleichstellungsgesetzes; Universität Kassel: Kassel, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, E.; Wilton, R. Alternative spaces of ‘work’ and inclusion for disabled people. Disabil. Soc. 2011, 26, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraina, S. Analysis of the Legal Meaning of Article 27 of the UN CRPD: Key Challenges for Adapted Work Settings. GLADNET Collection. 2012. Available online: https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1559&context=gladnetcollect (accessed on 19 April 2014).

- Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Concluding Observations on the Initial Report of Germany; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arbeitskreis Arbeitsmarktpolitik. Solidarische und sozialinvestive Arbeitsmarktpolitik: Vorschläge des Arbeitskreises Arbeitsmarktpolitik; Hans-Böckler-Stiftung: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3-86593-284-6. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, U. Die Inklusionslüge. Behinderung im Flexiblen Kapitalismus; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2015; ISBN 978-3-8376-3056-5. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).