3.1. The Process of Building the Motivation to Become a Foster Family

The results of this research allow us to argue that the motivation driving families to foster a child is rooted in the values of altruism and is supported by the families’ affection for children, as well as their sensitivity to the maltreatment that affects many children in Portugal. It was perceived that the altruism exhibited by these families was not unconditional, an important consideration being the importance attributed to the wellbeing of the foster family itself. The valorisation of the family unit as a suitable context for the socialisation of children and the desire to provide children with the right to grow up in a family were also part of the motivation to become a foster family. At the same time, these motivating conditions establish clear foster family limits by making it visible that the family’s provision of foster care will be re-evaluated if the provision of that childcare affects the established family balance. These results, observed during this study of foster families in Portugal, are consistent with other national and international studies, namely Schofield, Beek, Sargent, & Thoburn [

8], Delgado [

2], Howell-Moroney [

9], and Leschied et al. [

10]. These authors also highlight altruistic values focusing on the child’s wellbeing or the individual’s sense of contributing to society, the desire to promote a good home for the child, the desire to provide an institutionalised child with a parent’s love and a home, as well as the desire to help a child with special problems and help the wider community/society by providing adequate levels of protection and development opportunities for children.

According to this study, these motivational aspects—particularly those associated with the personal and professional biography of foster carers, as well as carers having experienced direct or indirect contact with residential care or other contexts of de-protection—are factors that contribute to help predispose families from a variety of different backgrounds to become foster families. This is an aspect that is less focused on by the available international and national literature on foster families, highlighting the contribution of this research to the study of foster care, particularly to the process of building the motivation for foster care. In addition to the biographical component, which may be more evident in the study of attitudinal processes, the carer’s contact with experiences of de-protection appears to us as a suggestive explanatory element for the motivation of non-professional foster families. In fact, some studies show the influence of the professional trajectory of caregivers as a motivational factor, there being examples of foster carers who, in the past, have worked in a professional capacity with children or families in need (e.g., as nurses, teachers, or in other professions in the social care area, namely, families with quasi-professional care-characteristics [

11]).

Other studies also point out the importance of knowing other foster families as a motivational factor, as well as the role the children of old caregivers can play in integrating children into new foster families (see Nutt [

11], Del Valle et al. [

12] and Delgado [

2]). In the present study, only one of the interviewed caregivers had previously known a foster family in a professional context, the experience projecting the desire to help a child into her future in an intensive way, despite the fact that in her daily life she had already observed many children deprived of both their basic emotional and physical needs.

Advocacy for the cause of foster care, such as that which has been developed in a particularly active way by the NGO involved in facilitating and supporting care in northern Portugal, will only have an impact upon potential carers when the predisposition to become a foster family is already anchored in the potential candidates. This study shows that the care-giving participants subject to the process of sensitisation and recruitment that this organisation performs were, in a more or less conscious way, already predisposed to participate in the supporting of children subject to poor situational circumstances. The billboards and brochures they fund, with appealing images of children, act as a motivational driver, awakening a latent desire in potential carers to welcome a child into their home, or inducing their children to express the desire to become a foster family. Positive reports of children’s and families’ experiences with videos that the NGO divulges confirms the theory that such material feeds and reinforces the predisposition to foster, leading to the final decision of candidacy. Such narratives show the importance of the diversity of approaches and media used in publically diffusing and advocating the figure of the foster family.

Empirical data also shows self-centred motivations for foster care. The fostering of a child can satisfy the ambitions and personal desires of a carer (“The girl … the girl I have never had, I do not know if you are understanding me … I have a boy, I have never wanted having more”—foster carer), perhaps providing fraternal relations to their only begotten son. Fostering can confer a sense of family wellbeing, joy, self-esteem, and a sense of social utility; fostering can even help a carer avoid depressive signals, giving meaning to their everyday life, as well as offering an occupation and the warmth of human company. Nutt [

11] noticed in her study that a participant whose mother had committed suicide regarded the upbringing of children as the fundamental purpose of his life, “Without them, I would be depressed”, fostering providing him with a sense of meaning within his life. The motivation for fostering can be child-centred, self-oriented, and society-oriented, with most families involving themselves with foster care for reasons centering on the child (cf. Maeyer et al. [

13], Rhodes et al. [

14]). Howell-Moroney [

9] observed self-centred motivations, such as the desire to be loved by a child, as the motivation for almost half of the participants in his study. It should also be noted that he found more self-centred motives in people who had no religious motivation to foster. Fostering can also be a way of gaining self-esteem, obtaining an emotional reward, healing the wounds of the past, or as a consistent form of employment [

11]. Satisfying the desire to “fill the empty nest” when biological children are older, the low chances of adopting a child, or the desire to provide companionship for a child [

10] are other motivations pointed out in the literature.

From the point of view of economic convenience, often associated as the dominant social motivation for foster families, our study is consistent with the results of the current international research [

11,

15]. As the results show, carers do not express economic interests in the first instance; stating that money does not count, carers consider the unconditional love they offer children to be far more important than the remunerative value they receive. Although, it is observed (as mentioned in the testimony of a support team) that there may be candidates with economic interests, especially when considering foster care as a replacement for a regular job. Carers, in their testimonies, do not seem to regard foster care as a way of professionalising women, focusing more on foster care as the domain of both personal and family fulfilment, as a healthy occupation, or both. In any case, as pointed out by the professionals of one support team, it is not the fact that carers receive a monetary value compatible with their performance, and with the expenses inherent to the child, “that makes the measure less affectionate”. This motivational dimension gains an added significance when considering the limited monetary values that Portuguese foster families receive from the welfare system as a reward for their community service and a reimbursement for the increase in their family expenses. Foster families often end up making personal sacrifices they should not have to make, even though the participants understand that this is part of the commitment they have made. Based on the literature, however, Delgado [

2] points out that fostering at the international level exhibits a tendency towards professionalisation, despite verifiable apprehensions regarding the disappearance thereof of the informality and altruism characteristic of a personally motivated form of foster care.

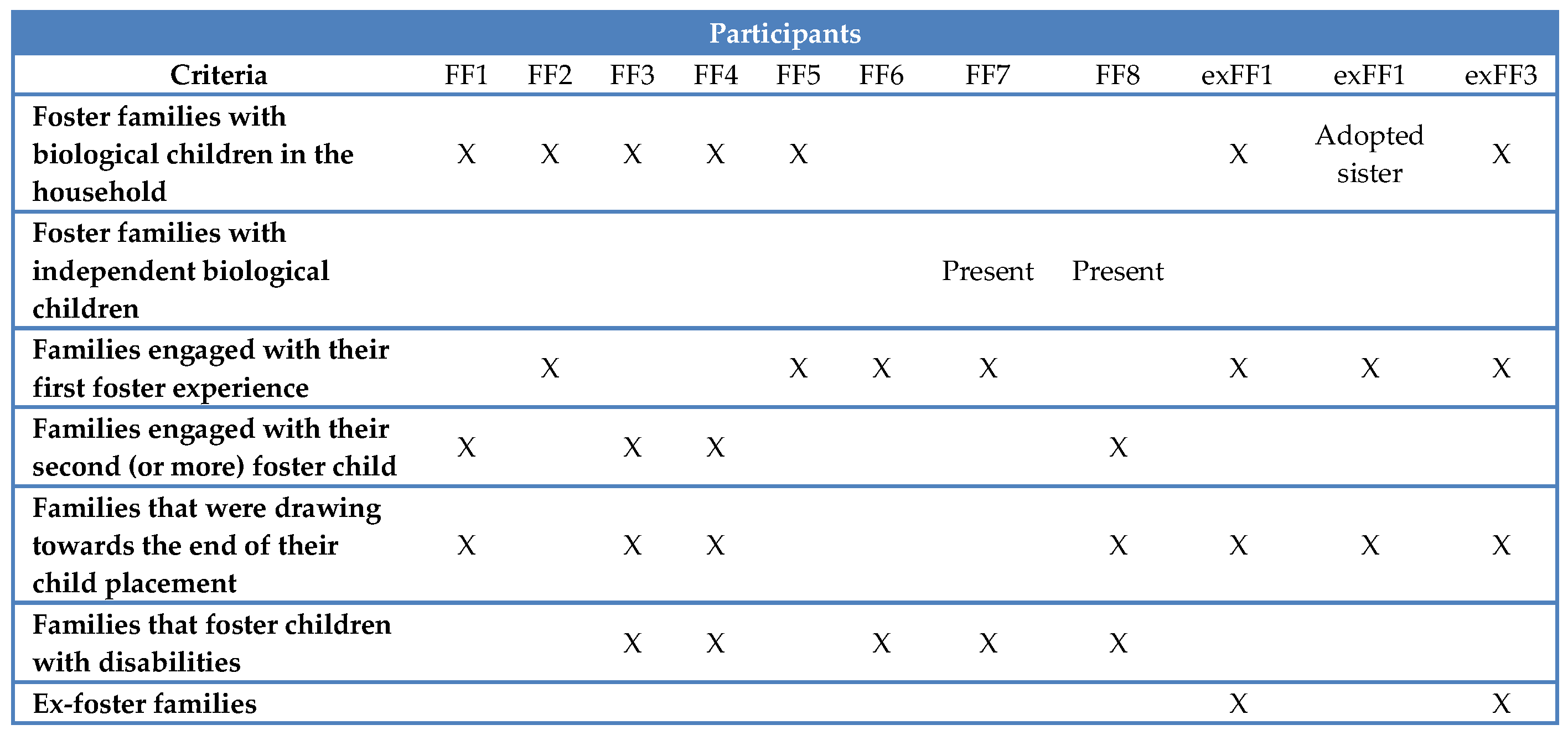

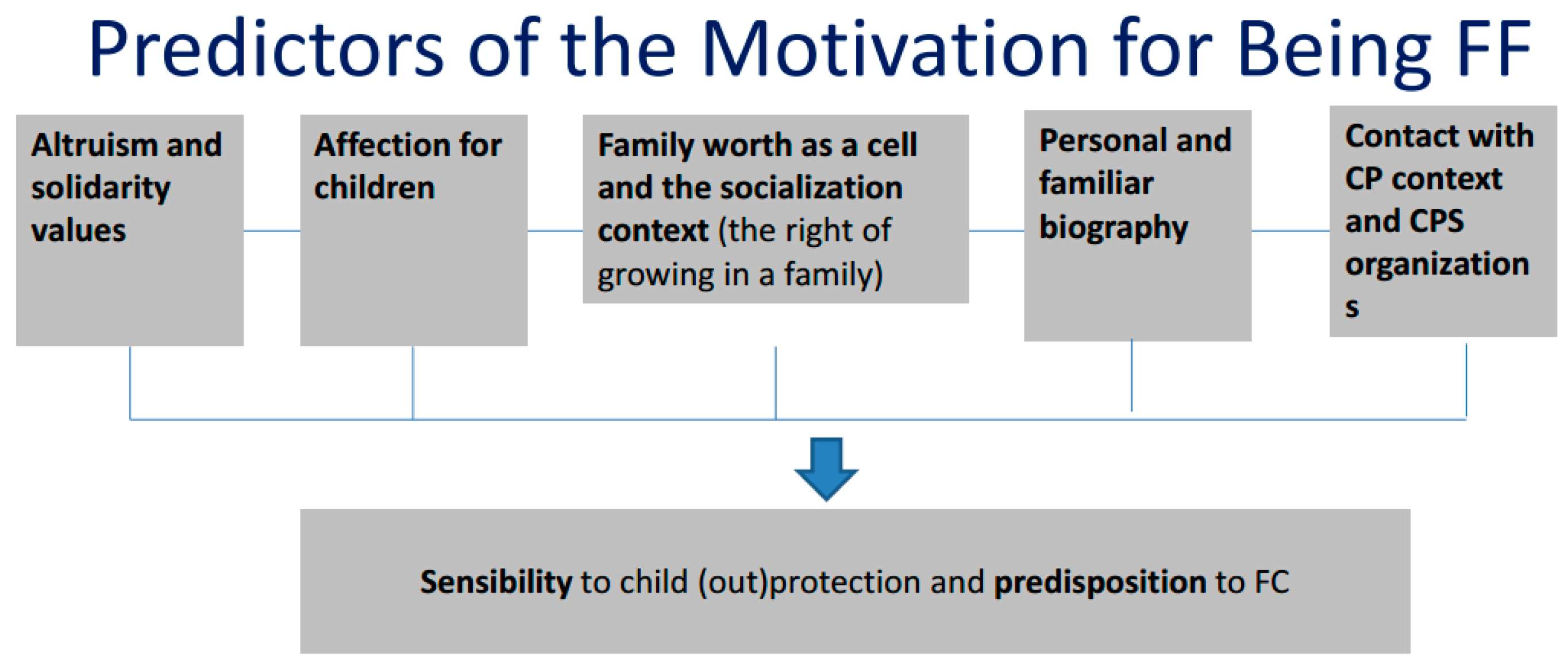

It can be concluded, as can be seen in

Figure 2 (Predictors of the Motivation for Being a Foster Family), that the motivation of these foster families was rooted in values of altruism, supported by their affection for children and their sensitivity to issues of child-protection. These factors, associated with a carer’s personal and professional biography, as well as their direct or indirect contact with care-contexts in which children lack protection, produce a predisposition to become a foster family.

3.2. The Experience of Being a Foster Family

From the point of view of the foster experience, it is lived by the carers, both in terms of the challenges and rewards. For the study participants, being a foster family was deemed a rewarding experience, particularly when considering the recognition afforded to the child, the family, the community, and the professionals involved. Even situations in which the carers had considered giving up or placements with a lot of negative aspects, the carers continued to say that it was “worth it” and that they would repeat every step. Personal and family development, as well as the positive impact on the child’s development (see also Palacios & Amorós [

3], Nutt [

11]; and Delgado et al. [

4]) are the most valued points of the foster experience—aspects also pointed out by the professionals interviewed.

The arrival of the child into the foster home is a moment of joy and emotion. The child is wanted and integrated into the family as if he/she was another family member, a process described by both the experts and the studies of Oliveira [

16] and Blythe [

17]. Family relationships assume the characteristics of parenthood and fraternity, including the foster child’s relationship with the carer’s extended family and friends. Personal and family dynamics really change. However, change is viewed as occurring naturally during the process. Adjustments are made in terms of physical space, schedules, and routines. In a more contrasting position, Nutt [

11] points out that foster children can change the lives of foster families completely, since the system expects that they will be much more than just carers. The professionals of one team recalled how a foster family is required, upon their reception of a foster child, to open themselves and their family to the professionals of the various services related to the child protection system, as well as to the courts [

11]. Tribuna & Relvas [

18] admit that the conciliation between the different subsystems of foster family (biological parents, children, foster families, and the social services) can complicate the experience for the carers, acknowledging that a clear mode of communication and relations between these various bodies can bring stability to the complex network which is established.

Among the participants, the procedural aspects of the service are understood as being part of the foster process, carers being aware of the bureaucratic and legal demands inherent to the assumed function of the carer. Carers are ready to receive the support team, as well as to arrange visits with the biological family. The data collected indicated that it could be complicated for carers to have children whose parents are different. Scheduling meetings with one or two mothers in parallel with one or more fathers can lead to a family overload, especially from the point of view of the monetary expenditure and time required (for example, when such visits involve the carers engaging in extensive travel). This indicates that, according to foster families, when it is expected to maintain regular contact with the biological family, it will be easier to foster siblings.

Only two of the families were affected by the wear and tear of their experience as carers to a sufficiently negative degree for them to consider stopping. Such fatigue is directly related to the behaviour of the child they place, and may induce moments of instability. However, such fatigue is often mitigated when carers see the satisfaction of the child and feel the emotional rewards of the experience. Nevertheless, in a study by Triseliotis et al. [

19], some carers admitted their need for a resting period between placements. This study does not exhibit this need, and may even be considered to present evidence contradicting this thesis, especially since the more experienced of the interviewed families were the most readily available to continue fostering uninterruptedly. There is a greater overload in carers whose husbands are less actively involved in the care process due to their schedule, place of work, or motivation for engaging with foster care. Heslop [

20] argues that male and female carers are often underestimated and stereotyped, stating that both men and women have great skill sets applicable to the education, care, and discipline of foster children, as well as suggesting that coaches often help male carers to negotiate their role in the foster care process. From this point of view, we can see the importance of an atmosphere of mutual support and cooperation among family members. Carers are the main providers of care for both their own family and the foster child. Overloading is reduced and family satisfaction increases when there is a fair distribution of the household tasks between the carers (such tasks even being distributed amongst their own children).

Both teams interviewed were unaware of the existence of foster families who had effectively ceased their fostering activities of their own initiative. Carers’ children tend to be satisfied with the presence of a foster child, often collaborating in the provision of the basic care, supervision, play, and schoolwork. They build a fraternal relationship. Biological children admit to being jealous in some situations, which is unsurprising considering that they frequently have to share their parents’ attention with a foster child. Some carers claimed to give more attention and time to their foster child, often to the detriment of their own children, in an attempt to make up for the care they had not received in the past. They try to compensate for the negative impacts of fostering on children, employing strategies such as listening the children their own motivation for fostering, developing awareness of the personality characteristics and previous life-course of the child, and planning ‘alone moments’ between parents and their biological children, without the presence of their foster child. The international literature (Höjer et al. [

21]) also suggests techniques such as involving biological children in the decision to accept a foster child; informing them about foster care in general, as well as about each child; identifying protected moments for their own children; limiting information about the process; discussing problems derived from their fostering; and preparing their own children for the end of the foster period, in order to soften the impact. Through the experience of foster care, carers’ children can develop values of solidarity, sharing, and fraternity, or just suffer and revolt, creating conflicts. In care-denial situations, carers tend to consider giving up receiving a child, or delay a new placement, in order to protect their family unit. Nutt [

11] has obtained significant results in terms of analysing how the children of carers can be marginalised by parents engaged in fostering, evoking the role of the authorities in the protection of these children. As this is an undoubtedly relevant issue, the evidence gathered in this study seems insufficient to confirm Nutt’s thesis of the marginalisation of carers’ children as a result of their fostering, or the need for the intervention of the social services in order to ensure carers’ children are protected. However, based upon the research informing this study, it is possible to acknowledge that younger children may suffer more from fostering than older children, due to the higher level of attention they require from their parents. The foster families in the present study all have children who seem to have suffered from their family’s reception of another child. However, these families say that, when their children are older and eventually independent, they intend to become a foster family again.

The relationship between the carers and the foster child’s family of origin was generally described as positive. Conflict was only noted in one instance. The foster families tend to empathise with the biological parents, reassure them, and share a joint role in determining educational strategies for the child. They often perceive economic and material shortages in the biological family, and can seek to assist thereof, providing food aid, for example. By helping the biological family, carers intend to help the child. Given the frequent contact and sharing of their daily lives (namely, the task of caring for and educating the same child), in some cases the family of origin can become a part of the foster family, a phenomena confirmed by both Cleaver [

22] and Nutt [

11]. A good relationship with the biological family means the foster family is often able to maintain contact with the child after the placement has ended, which is typically one of the family’s greatest wishes.

Many participants state that they respect the family of origin’s right to both live with the child and share the responsibilities of parenting, as noted by Riggs [

23]. Tribuna & Relvas [

18], analysing this dimension of the foster care experience, introduced the concept of ‘paradoxical double-parenthood,’ understanding that “the child is subject to a communication with two logical levels (between the biological family and the foster family), which are irreconcilable”. The child often finds him or herself divided between two spheres of influence. On the one hand, the foster child is loyal to the parenting of the biological subsystem of their two sets of parents, often expressed non-verbally, and including strong aspects of passivity and social maladjustment; on the other hand, the child must adapt to the functional parenting subsystem of their foster family, expressed verbally and espousing values intended to facilitate the child’s adaptation to normative social values.

Curiously, regarding the issue of contact with families of origin, the interviewed professional teams had a variety of different opinions, ranging from a view emphasising the ability of the foster family to form a positive relationship with the family of origin, to a view strongly indicating a perceived difficulty or incapacity of carers to deal with them. Both Riggs [

23] and Nutt [

11] admit in their studies that foster families have a fragile and ambiguous role when compared with the family of origin and the social services, in terms of their legal powers and authority.

In line with national and international studies (such as Amorós & Palacios [

3]; Martins [

24]) and with the testimony of supporting teams, a carer’s greatest challenge seems to be the management of a foster child’s challenging behaviour in domestic scenarios. Carers perceive and respect the characteristics and life-history of the child, often employing strategies they have used with their own children—demonstrating the positive application of skills derived from their experiences with their own children. Delgado et al. [

4] points out that “carers do not enjoy an equal decision-making freedom in relation to their children, nor can the behaviour of the children in question be compared in most situations to their behaviour. To steal, to lie, to destroy, to beat, to take drugs, to escape are some of these behaviours.” For these families, fostering means not only to form, but also to re-socialise a child, many carers admitting that it is a complex task. The results of this study are similar to those exhibited in Nutt’s [

11] research, revealing how carers tried to understand and explain a child’s behaviour, but experienced a great degree of difficulty in perceiving “what was really going on in the mind of the child” [

25]. That a family “truly cares” about their foster child is a common expression, emphasising how selfless motivation and affection are factors central to a successful placement. Resilience in managing stress is also a key family trait required for the successful fulfilment of a child’s foster placement.

The capacity for family resilience is especially important due to the stress and anxiety families experience when waiting for a child to be placed. Factors such as not knowing how long the foster selection process will take, the procedures, and the fear that the endeavour will fail can take their toll. Often, such stresses continue throughout the child’s placement and after it has ended. As pointed out by Delgado et al. [

4], coupled with the challenges of being a carer, foster families perceive several rewards for their endeavour, mostly associated with the positive affects they have on the development of the child, the child’s recognition of this, and the affection they convey as a result of their improved situation. Some participants reported that a child’s smile was enough to reinforce their resilience.

Adequate professional support is a core care aspect, especially from the point of view of behavioural management, which often lacks specialised intervention and guidance. Carers appreciate their relationship with care professionals, as well as their availability and appreciation of the carers’ task. The wider social support of carers’ family and friends is also fundamental for the success of the foster experience, as pointed out by Ciarrochi, et al. [

26].

Participants in this study emphasised a feeling of apprehension relative to the cessation phase of a foster placement, their primary fear being that of losing contact with the foster child. Schofield & Beek [

27] support the importance of emotional attachment as a factor related to the potential success of a placement. Carers often disagree about the future insertion of foster children, namely into theirs family of origin, believing the child’s best interests to be served by remaining in the foster family. The foster family can feel a double-pronged suffering at the end of a placement, firstly perceiving the child’s desire to continue their placement with the family, and secondly feeling the loss of the child and the intimacy of that relationship upon their departure. Experienced families develop strategies to cope with the emotional demands of the separation process, which merit the attention of the social services. Such techniques include accommodating two children (i.e., tending sisters) simultaneously in order that they might support each other upon the cessation of their placement, as well as creating a strong primary relationship network of family and friends in order to accommodate the feeling of emptiness when the children leave and provide a source of emotional support. Other techniques include maintaining contact with the child after the cessation, preserving memories of the foster experience through the use of photographs, videos, and other memorabilia, and receiving new foster children before the cessation of a child’s placement in order to facilitate an emotional transition period and alleviate the anguish caused by the ultimate loss of the foster child. There was a difference of opinion amongst the professionals interviewed as to which technique was the most effective coping mechanism. In one case, the acceptance of the transitional measure adopted by foster families was emphasised; in another, such a provision was criticised. This study shows that when families contact the social services in order to apply for a foster placement, they often believe that they can keep the child in their household until adulthood, admitting a feeling of disappointment when they receive information contrary to this presumption. It also shows that families accept the transitional nature of the foster care measure, and they are aware a cessation of care will eventually occur. Although they anticipate this period to cause some suffering, they are satisfied with their ability to maintain contact with the child and see her/him well after the end of the placement. Family support at this stage should not be overlooked. Delgado [

2], based on studies and research projects, suggests that the official entities can “admit the possibility of adoption by the carers, fulfilling certain requirements and according to well-defined criteria”. Most of the participating families would indisputably approve of the possible use of adoption as a solution to the shortcomings of the foster-care process. Furthermore, we, as researchers, must admit that, in many situations, such a solution would be in the child’s best interests.

De-attachment differs from situation to situation. Biehal [

28] identifies four types of perceived attachment in foster care: “as if” (almost adoption); “as” (carers were other parents); “qualified” (with feelings of hurt and ambivalence towards their biological parents); and “provisional” (as in the cessation phase).

Essentially, as Palacios [

29] points out, it is important to prepare for the transition period. There is an ambiguity of purpose inherent to the caring role of the foster family. On one hand, the foster family is asked to be actively involved and to create an affectionate relationship with the child; on the other hand, the transitional nature of the foster measure is emphasised (see Delgado, et al. [

8]).

As mentioned, the ability to maintain contact with a child after the cessation of their placement reassures foster families, an aspect of the care process foreseen by the writers of the Manual of the Key Processes of Foster Care (Manual dos Processos-Chave do Acolhimento Familiar) [

30], as well as being covered in article 34 of DL 11/2008 of 17 January (permission to maintain contact being granted depending on the favourable opinion of the care professionals involved and the agreement of the biological family). Delgado [

2,

4] justifies the desire to maintain contact by citing the creation of mutually affective bonds during the child’s reception, both the carers and the child being able to remember their common history, and the positive effects of this attachment being weakened gradually and naturally after the child is removed, rather than abruptly ending. The desire of the foster families to preserve their relationship with their foster children demonstrates that the attachment formed during placements was of an emotional, not a utilitarian, nature; an attachment beyond the immediate emotional character of the care process. Attachment is built and often maintained after the cessation of care.

Some participants were emotional when talking about fostered children they had not contacted for years. These aspects indicated that the foster families accepted the transitional nature of the measure (“not staying with children forever”), whilst considering the possibility of maintaining future contact.

3.3. Renewing the Disposition to Continue Being a Foster Family

In terms of a third dimension, our study shows that resilience to the difficulties of accommodating children with traumatic experiences and challenging behaviour, the quality of the carer support provided by the social services, and the ability to maintain contact with the child after the cessation of care contribute to renew a family’s disposition to be a foster family.

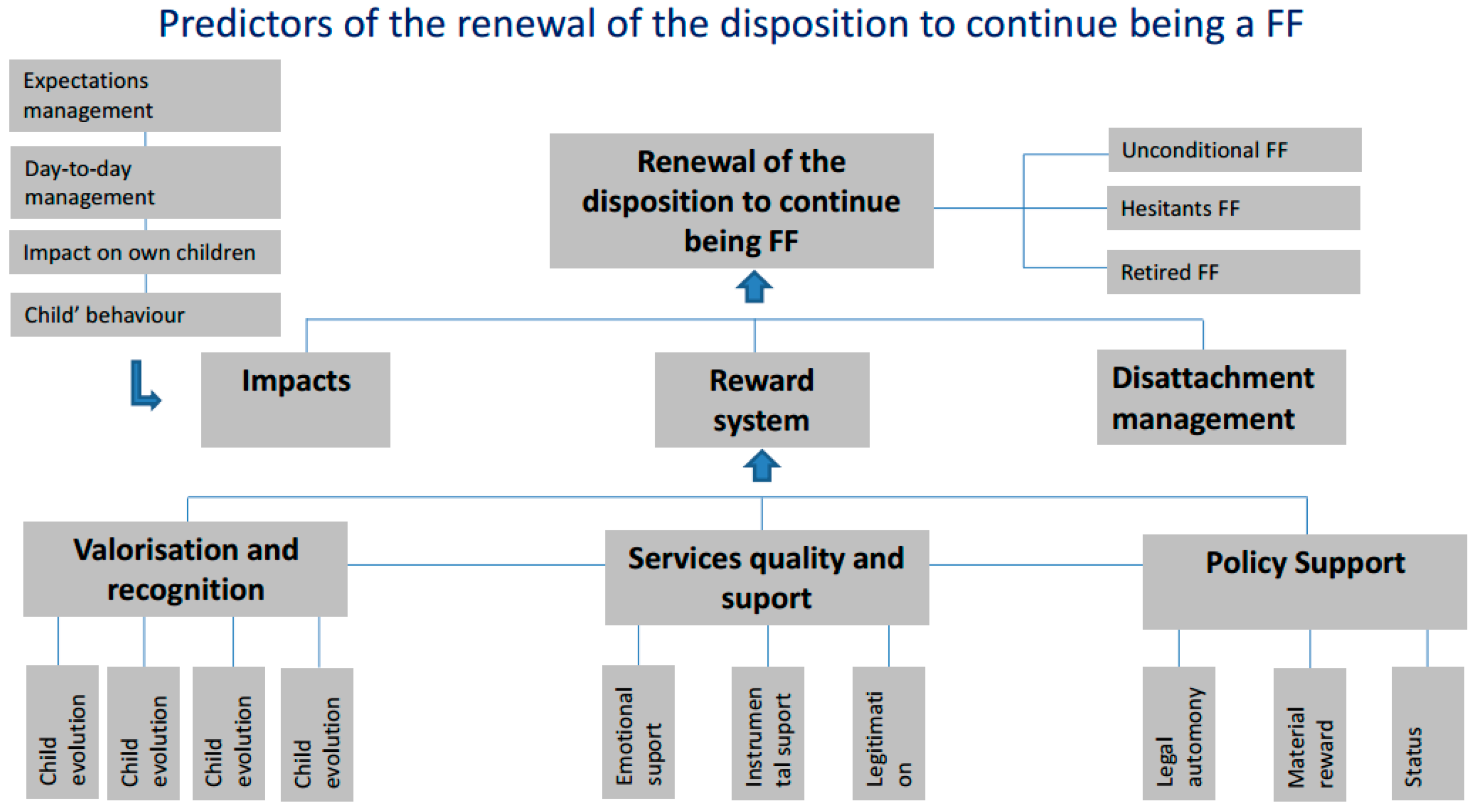

As seen in

Figure 3 “Predictors of the Renewal of the Disposition to Continue Being a Foster Family”, below, impacts upon the carer’s family, the rewards system, and the management of the de-attachment period are also clearly influential. Impacts upon carers’ lives include the management of their expectations, daily life, the impact of fostering on their biological/adoptive children, and the management of both their biological and fostered children’s behaviour. The rewards for the foster experience include the valorisation and recognition carers receive from the child itself, their biological family, extended family, and the wider support team; support provided by the social services, including emotional support, instrumental support, and legitimacy attributed to their role; and the legal framework informing the care-process, including carers’ legal autonomy, material rewards provided for the provision of care, and the positive impact of fostering upon their social status. Finally, the management of the de-attachment at the end of a placement, particularly the quality of the preparation and support provided by the social services, is highly influential.

The happiness that a foster child exhibits as a result of being with the right foster family, the feeling of belonging to that family, and the positive personal development they experience, are deemed by many foster families as compensation and recognition enough for the “effort” and care they contribute every day.

The extended family and friends of foster families can contribute to their personal satisfaction by acting in solidarity with them, recognising the social value of carers, praising their availability, and encouraging that they continue fostering children in need. In the present study, only one family reported being deprived of support by their extended family and friends, consequently finding themselves in conflict with some of their relatives. The carers reported that the placement was stopped, saying, however, that there was a possibility they would return to fostering in the future.

Respect, reinforcement, support, and the recognition of professionals and the social services are also fundamentally motivating elements upon which carers rely, as well as being indicators of the outcome of their performance as carers. Situations in which the professionalism of the supporting teams is not manifested and the provision of carer support is inadequate often discourage carers. In the event of a conflict between the foster family and the foster child, carers understand that the supporting team will always take the side of the child, in a manner often deemed as detrimental to the foster family. This can leave carers feeling accused, discredited, unnecessary, and useless. Their feel their performance is undermined despite the effort they have made. However, contrary to such attitudes, it is important to legitimise the carer’s role and status in order to facilitate the successful placement of a child and maintain the active fostering of experienced foster families.

Based on the results of the present study, the future availability of carers, as well as their will to foster a new child, can be classified as belonging to three distinct groups: “unconditional”, “hesitant”, and “retired”. The more experienced foster families regarded foster care as if it were habituated, often finding it hard to imagine a life without children, describing themselves as readily available to foster two or more children simultaneously, and professing the wish to continually foster until something prevented them from doing so. They reported friends and family as encouraging and supportive of them in their fostering endeavours. The “hesitant” foster families (and those who had stopped fostering) were in the midst of their first placement, often experiencing challenges that made them oscillate in terms of the decisiveness of their commitment to fostering. They described the encouragement received from the people close to them as fragile. Their biological children or husband tended not take care of the extra children (especially in the case of families that stopped fostering, which have been designated in this study as ex-foster families). The designation of “retired” may be used to describe foster families who did not intend to accommodate further children due to their progressing age and consequent loss of capacity. Feeling old, they expressed the wish to dedicate themselves to their own family, with no intention of supporting any new foster children.

In the opinion of one of the supporting teams interviewed, foster families expect to be rewarded with gratitude for the task they carry out, and consider a parent’s care for their own biological children to be a social requirement.

The interviewed professionals considered a family’s disposition to foster new children to be correlated with the quality of the previous cessation of care, the sense of accomplishment attained from fostering, or with the realisation or frustration of their initial expectations as carers. In fact, this study revealed that one of the participants, upon experiencing a painful and unsuitable cessation of care, had, at a later date, with the intervention of the social services support team, again fostered other children, remaining a self-professed “unconditional” carer.

Efforts to increase the number of placements in foster care through the recruitment of families have not proved sufficient. The support, training, and professional consideration awarded to carers are in need of substantial reform. Delgado [

2] also argues that the provision of a financial margin provides carers with the freedom of choice, contributing to the retention of existing foster families and attracting new candidates. There are many studies exhibiting a diverse array of results and implications for practice, programming, and policy analysis (Denby et al. [

31]), all of which professionals need to take into account when intervening with foster families in order to ensure both the family’s satisfaction and the success of the placement. The results of this study have lead the authors to reinforce the need for organizations to make timely decisions (particularly in terms of bureaucracy), reflecting the shared commitment of both the carers and the social services to the wellbeing of children. Carers must be dealt with consistently, their motivations must be respected, their roles kept clear, and they must be treated as team members. Further conclusions include that foster families should have easy access to support services, be provided with rest periods between placements, that professionals should consistently address the needs of foster families, and that such needs should be recorded and retained as a fundamental body of information for the purpose of sharing carer experiences with other foster families. Another conclusion of note, derived from the present study, is that of foster families seemingly wanting to apply their competence in care, emotional solidarity, and social skills to good effect, the more experienced families being the most likely to continue fostering (the foster family profile designated as “unconditional” being characterised as “addicted to childcare”).