Abstract

Despite extensive research on health in working life, few studies focus on this issue from the perspective of managers in small-scale enterprises (SSEs). To gain deeper knowledge of managers’ perceptions and strategies for dealing with workplace health management, 13 Norwegian and Swedish SSE managers were interviewed after participating in a workplace health development project. The methodical approach was based on Grounded Theory with a constructivist orientation. The main theme that emerged was ‘ambiguity in workplace health management and maintaining the business’, which was related to the categories ‘internal workplace settings’, ‘workplace surroundings’, and ‘leadership strategies’. The managers experienced ambiguity due to internal and external demands. These requirements were linked to the core challenges in dealing with multitasking leadership, financial decision-making, labour legislation, staff development and maintaining business. However, the managers developed new skills and competence and thereby a more reflexive approach and readiness to create a health-promoting workplace from being part of a development project. The implications are that managers in SSEs need to exchange experiences and discuss workplace health issues with other managers in networks. It is also important that occupational health services and social and welfare organizations use tailor-made models and strategies for supporting SSEs.

1. Introduction

Encouraging entrepreneurship has become a priority in contemporary economies worldwide due to its contribution to growth and enhanced business [1,2,3]. In particular, small-scale enterprises (SSEs) with fewer than 20 employees are important for both national and regional economic sustainability and for the jobs they provide [4]. In Sweden and Norway, around one-fifth of the working population is employed in this enterprise category [5,6].

Despite extensive research on psychosocial working conditions and health in working life, few studies focus on these issues from the perspective of managers and employees in SSEs [7,8,9]. This is surprising, because extensive research emphasizes that SSEs have limited personnel and financial resources, and limited competence in Occupational Health and Safety Management (OHSM) [10,11,12,13,14]. In this study, we approached health from a broad physical, psychological and social perspective across both work and home contexts, as defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO) [15].

Workplace Health Management (WHM) consists of a set of leadership behaviours that continuously interact with the working environment to design an environment that enhances employee health [16]. WHM is rarely addressed in small business research [17,18,19,20]. WHM is crucial for improvements in psychosocial working conditions and health [21], but few studies explore the challenges SSEs experience regarding these issues and which contextual factors can contribute to improvements. The aim of the study is to explore SSE manager’s understandings and approaches to WHM after participating in a health-promoting development project.

1.1. Workplace Health Management in Small-Scale Enterprises

Difficulties in working with health and working conditions arise because managers are responsible for many business activities, with little time for giving priority to health and working conditions [22]. Nevertheless, SSEs have good conditions for creating a healthy working environment due to their unique social and organizational attributes [23,24,25]. This is because the distance between decision-makers and co-workers is short, and managers as well as co-workers have considerable control of their work tasks [8,26,27,28]. The characteristics of SSEs create potential for developing a positive culture at the workplace, which can in turn contribute to improving individual health and organizational performance [29]. In sum, this can create positive health and psychosocial working condition outcomes [30].

SSEs in Norway and Sweden are subject to legal requirements for maintaining a working environment that provides a basis for a healthy and meaningful working situation [31,32]. However, SSEs experience constraints in implementing OHSM and there are few structures for support. Compared with large-scale enterprises, they do not have the structural, financial, or personnel resources to implement complex systems [33].

A study has shown that SSE managers experience the role of the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (SIA) and their coordination as unclear [34]. The SIA in Sweden and the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Organization (NAV) are government agencies with the purpose of assisting companies and individuals with health problems and helping people back to a job, so that fewer people depend on public benefits. Most companies in Norway and Sweden relate to these governmental agencies in policy, pension and sick leave issues.

In Norway and Sweden, the workforce in SSEs has less access to occupational health services (OHS) than larger enterprises [32,35,36]. A Swedish study showed that OHS providers did not develop a close relationship with their SSE clients [37]. Other research shows that OHS have problems in reaching out to SSEs in Norway as well as in Sweden [14]. This indicates that SSEs may experience problems in finding information or solutions to their problems in health and working environment issues. Additionally, they are sceptical or suspicious of external consultants [12]. The support depends on personal contacts with a trusting relationship that can motivate their engagement [12,38]. Knowledge is the key factor enabling SSEs to work with these issues, while the implementation of interventions seems mainly driven by economic resources [39].

1.2. The Workplace Health Management Development Project

The WHM development project was oriented towards SSEs and focused on issues of management, psychosocial working conditions, and workers’ health and lifestyle. One goal of the project was to develop and implement models and methods for improving health and psychosocial working conditions for this enterprise group. One OHS in Norway and another OHS in Sweden guided the SSEs and conducted the development project. Both OHS mainly focused on leadership competence with regard to health and psychosocial working conditions, but they also included individual-based components focused on managers and their employees, such as rehabilitation, healthy lifestyle promotion and physical activity. Thus, the interventions can be described as multicomponent interventions in accordance with the European Network of Workplace Health Promotion [23]. The first stage of the project focused on investigations of health and psychosocial working conditions at the workplace. The managers took part in physical health examinations followed by discussions about how to improve their health and lifestyle. In Norway, the OHS consultants also mapped the psychosocial working conditions for co-workers at the managers’ workplace using a questionnaire. Each participating SSE received the results summarized and presented in a local meeting. In Sweden, OHS consultants investigated the working conditions through a visit, and had dialogues afterwards with the local manager.

In the second stage, managers participated in network meetings guided by OHS consultants in each country over a period of about 12 months. These meetings covered issues such as the managers’ work-life balance, physical status and lifestyle, leadership behaviours and tools for improving psychosocial working conditions such as conflict management and feedback to staff. These meetings also included discussions about the managers’ experiences of health challenges at the workplace. In the third stage, managers received individual support from OHS personnel by telephone, e-mail, Skype and one-to-one meetings. In Norway, the OHS consultants once again mapped health and psychosocial working conditions for the participating SSEs. In Sweden, only managers participated in this mapping. Additionally, the OHS consultants provided the managers with feedback on workplace conditions and their possibilities for future measures to develop a healthier workplace.

2. Materials and Methods

We interviewed 13 of the 18 SSE managers who participated in the development project, eight from Norway and five from Sweden. We used a heterogeneous recruitment strategy, meaning that the managers varied in their duration of employment at the workplace, the type of enterprise in which they worked, gender, age, education and civil status. The interviewees were all managers of SSEs with up to 20 employees in rural areas of Sweden and Norway, and the SSEs belonged to different lines of business in the private sector. Table 1 describes the characteristics of the interviewees.

Table 1.

Characteristics and experiences of study participants.

2.1. Data Collection

Managers were interviewed one year after the end of their participation in the development project, and on one occasion. Data were collected between April to June in 2016; interviews lasted from 35 to 120 min and took place at the interviewee’s workplace. Two of the authors conducted the interviews. The interviews followed a thematic topic-centred interview guide. The topics concerned the managers’ experiences of participating in various aspects of the project and if these experiences influenced their leader behaviours, the support they received from OHS and if this support was valuable for themselves and the employees, their use of WHM measures in the workplace, and their view of future need concerning WHM measures and support from OHS. The interviewees were free to talk about other issues during the interviews even if these were not part of the topic-centred interview guide. The interviews were in the form of conversations where interviewers asked follow-up questions when statements or experiences were unclear. One researcher took notes during the interviews, and they were audio-recorded and transcribed.

2.2. Analysis

The data were analysed using a methodical approach based on Grounded Theory with a constructivist orientation [40,41,42]. In this approach, interviewing and analysis occur concurrently, allowing new topics to be explored if necessary. After conducting and analysing the first three interviews, we refined the topics covered in the interviews.

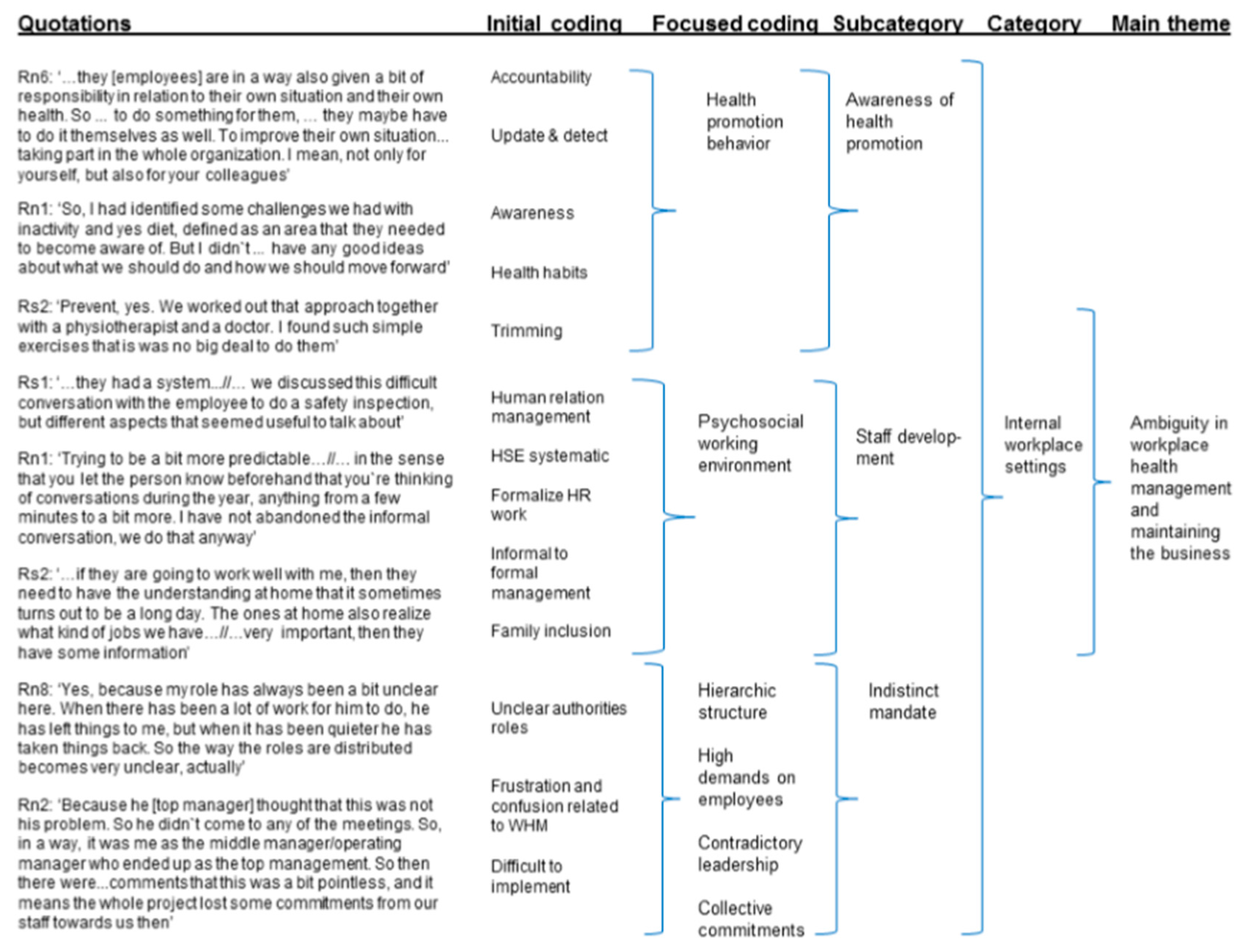

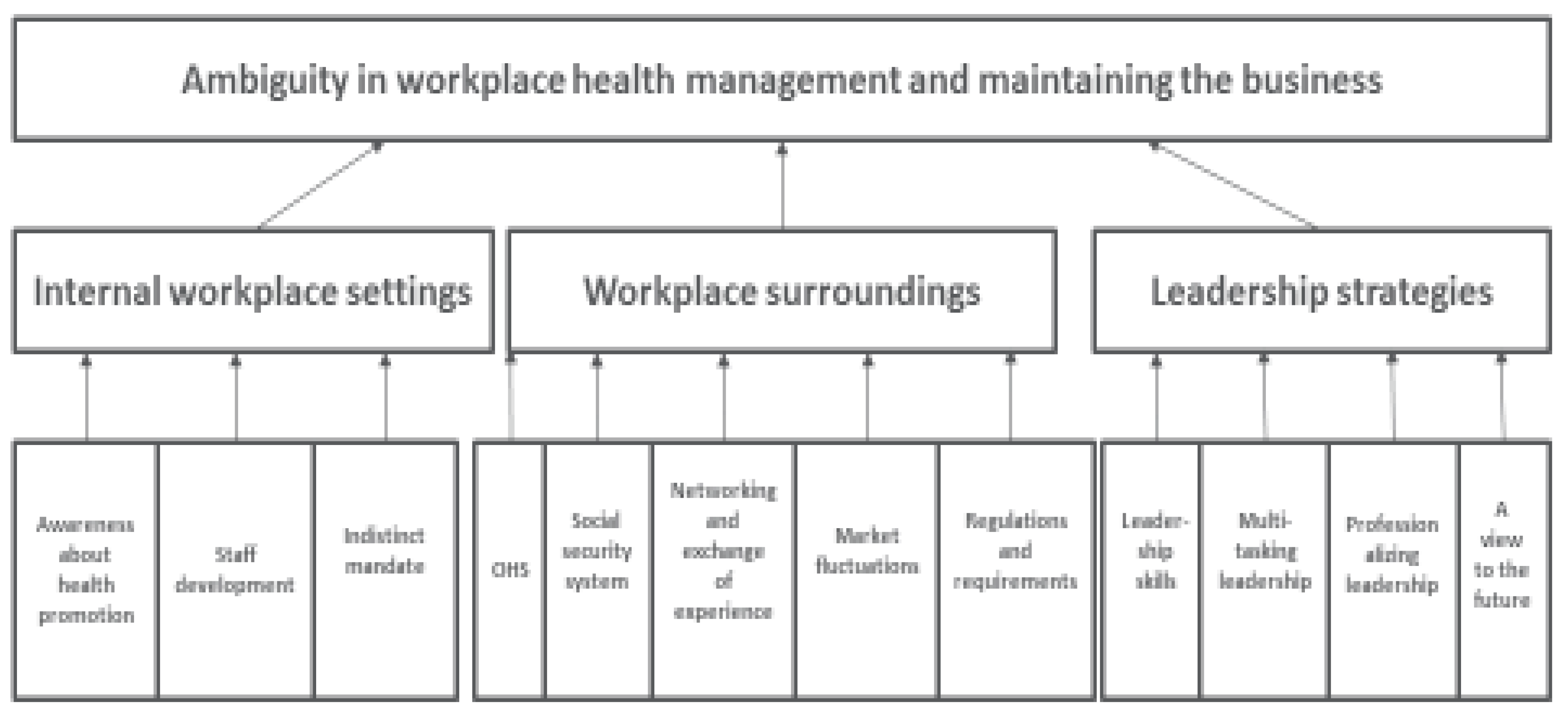

The data were successively read and analysed, and notes were written. We used the written notes at the various stages to identify emerging codes and categories, and to crystallize questions and direction for the analysis [40]. Figure 1 demonstrates the coding process. It started with initial coding of excerpts from the interview data, followed by focused coding, following the guidelines of Grounded Theory coding [40]. During the initial coding, we studied data as fragments, sentences, words, segments and incidents for their analytical value. During the focused coding, we selected the most useful initial codes, and tested them in the larger dataset. During this step of the analysis, data were continuously compared with each other and with the initial codes. We then sorted these codes and reduced them into a focused coding structure. During this analytical step, we formed subcategories based on comparison of the focused coding and initial coding. Finally, we grouped the subcategories into three main categories. Figure 2 describes the stages in this stepwise analysis.

Figure 1.

The steps of coding and the emerging categories exemplified by the category ‘Internal workplace settings’.

Figure 2.

The main theme, three categories, and related subcategories.

To increase the validity and credibility of the data analysis, two of the authors coded the interviews separately to improve the trustworthiness and then compared the analysis to reconcile inconsistency. Then all authors discussed and agreed on the coding, checked it against the transcript of the interviews and conducted a dialogue and saturation process by answering probing questions such as ‘what’, ‘how’, and ‘for whom’ to exhaust the preliminary coding schemes. Finally, the authors analysed and agreed on the theoretical and empirical coding and the analytical schemes.

The three categories included ‘internal workplace settings’, ‘workplace surroundings’, and ‘leadership strategies’. Each of the three categories included several subcategories. For example, the category ‘workplace surroundings’ consisted of five subcategories of ‘OHS’, ‘social security system’, ‘networking and exchange of experience’, ‘market fluctuations’ and ‘regulations and requirements’. One core theme emerged that encompassed the three categories: ‘ambiguity in workplace health management and maintaining the business’. Quotes by Swedish managers are marked with Rs and by Norwegian managers with Rn.

2.3. Ethics

The Swedish Regional Committee approved the study (Dnr 2014-28-31M). The informants gave written consent to participate in the study. The informants received information about their option to withdraw from the study without giving any reason. We anonymized and stored data according to the Swedish Act on Ethical Review of Research Involving Humans (SFS 2003:460 (2005)) [43].

3. Results

The main theme, ‘ambiguity in workplace health management and maintaining the business’, reflected the high degree of ambiguity among managers about how to develop a healthy workplace at the same time as running the business. Managers had to balance between demands and expectations from the market and the working environment regulations. Developing the SSE into a healthy workplace within this context added yet another challenge for the managers.

The three categories that formed the main theme: ‘internal workplace settings’, ‘workplace surroundings’ and ‘leadership strategies’ are each described further below.

3.1. Internal Workplace Settings

Internal workplace settings had an impact on manager’s approach to WHM. Being part of the development project made them more conscious and reflective about the possibilities for developing a healthier workplace. Through their participation in the project managers received positive suggestions about how to address health issues and health prevention strategies at the workplace, and to assist employees to take care of their own health. At the same time, managers felt restricted by their structural surroundings and their role as managers. If health issues were not prioritized by senior management or the board, however, managers found it difficult to implement WHM.

3.1.1. Awareness about Health Promotion

According to the managers, the development project influenced the work environment positively as co-workers increased their awareness and responsibility regarding personal health.

Rn4: So not only should one work out, but that one meets others … to keep a good work environment is also a health-promoting thing. Not necessarily to lift many kilos or run as many kilometres (as possible), just that people enjoy staying at work too. That is also an important piece (of workplace health). Not necessarily, that one should work out then. Just do things together. Therefore, we have social gatherings besides working out, perhaps more unhealthy ones, perhaps a few beers on payday.

The managers expressed that co-workers increased their awareness regarding nutrition and inactivity after they participated in the development project. During the project, the managers learned methods for health promotion to address specific problems in their workplaces, for instance the role of nutrition and exercise in health promotion. Importantly, the project taught managers to pay attention to preventative measures for their employees.

Rn1: So, I had identified some challenges we had with inactivity and yes diet, defined as an area that they needed to become aware of. But I didn’t really have any good ideas about what we should do and how we should move forward.

3.1.2. Staff Development

Based on knowledge they gained from participating in the project, the managers could target their personnel policy and be prepared for difficult conversations about health in the workplace. Some managers benefited from structuring their staff appraisals and using a more formalized approach. Some managers reduced the number of meetings at the workplace and adjusted them to focus on specific health topics.

Rn1: Trying to be a bit more predictable there as well—in the sense that you let the person know beforehand that you’re thinking of having a dialogue like that, so that the employee can also be prepared…a couple of conversations during the year, anything from a few minutes to a bit more. I have not abandoned the informal conversation, we do that anyway.

The managers learned to include social gatherings and family context into the personnel policy of the enterprise. Providing information to family members helped to improve their understanding of the enterprise and of the possible stresses and strains likely to be experienced by the employees. This enabled families to remain supportive of the employees.

Rs2: You try to arrange something once or twice a year, something completely different… Yes, so now for the autumn, I have ordered a theatre trip to Stockholm with partners… if they are going to work well with me, then they need to have the understanding at home that it sometimes turns out to be a long day. The ones at home also realize what kind of jobs we have. However, we always include partners for all Christmas arrangements… very important, then they have some information about the situation and generally hear about what the finances look like and what is being planned.

3.1.3. Indistinct Mandate

In some enterprises, the development project was run by a middle manager rather than the senior manager. These middle managers expressed a sense of unclear authority and duties in the project and in the company. This made it difficult to carry out the intentions of the development project at the workplace and realise its potential. Middle managers in SSEs needed to be flexible to respond to different demands at different times.

Rn8: Yes, because my role has always been a bit unclear here. When there has been a lot of work for him to do, he has left things to me, but when it has been quieter he has taken things back. So the way the roles are distributed becomes very unclear, actually. And then I feel uncertain.

Even if the project was managed by middle managers, it was important that the project had legitimacy among the senior management. Without senior management endorsement, the project would suffer from low engagement among the employees.

Rn2: Because he (senior manager) thought that this was not his problem. So he didn’t come to any of the meetings. So, in a way, it was me as the middle manager/operating manager who ended up as the top management. And I had to play my cards the way I wanted and the way it was supposed to be. So then there were… comments that this was a bit pointless, and it means that the whole project lost some commitment from our staff towards us then.

3.2. Workplace Surroundings

The workplace context had an impact on manager’s approach to WHM. The OHS involved in the project, became collaborators for practicing and developing WHM. Managers learned from this collaboration as it helped them with strategies for developing a healthy workplace. Through this process, they improved their skills and gained new insights into WHM. The project also gave managers new perceptions into how to utilize the support from the social security system for sick employees. However, these positive experiences learned through participating in the project could be challenging to apply as there were several and sometimes conflicting demands within and outside the workplace. Ensuring both the workplace finances and the market situation of the enterprise were the foremost priority for most managers, and therefore these issues typically received greater attention than WHM.

3.2.1. Occupational Health Services

In both Sweden and Norway, the OHS consultants were critical for educating and guiding the managers at the workplace.

Rn7: I had both confirmed something and revealed something. I think it was a useful process but the challenge is to continue to further develop ourselves. One thing is when someone from outside comes and runs things, even if we do the planning, it was the OHS (name) who supervised the entire staff team through the process. The challenges are when one is going to continuing further… we need to get commitment and some knowledge from the employees as well as a sense of belonging and resilience to the project. I do not know, in the employee group, we discovered parts that were challenging, things we got to work with so that it is not that challenging anymore.

The OHS consultants mentored managers in their leadership by discussing and prioritizing areas of importance and relevance for WHM.

Rs1: One can perhaps compare it a little bit to a mentoring relationship. If we talk about a management relationship, this is a mentoring relationship. You get a chance to discuss and share questions with someone who is perhaps more practised and experienced… a mentor who takes part in the discussion but also raises relevant issues. Have you thought about this? What do you do then? What can you do? Give good examples.

The managers commented that the support and external views of the OHS consultants were helpful to them in their daily work and enabled them to think about how to work with health promotion issues in the workplace.

The OHS consultants helped managers to gain skills across various fields, which the managers could take advantage of in their daily work. If they needed expertise to create a more health-promoting workplace, they had a counterpart with whom to discuss their ideas.

3.2.2. Social Security System

The development project entailed information about the support system offered by the relevant social insurance agencies: SIA (for Swedish SSEs) and NAV (for Norwegian SSEs). Such information made managers more aware of how to use this support system during sick leave or to prevent work-related absences.

Rn3: …and that was actually to absorb, yes, what the rules actually were. How do those rules on sick leave work, what are we entitled to, what can we claim?

Norwegian managers in particular said that they had gained new knowledge and experience from the project by using the NAV Inclusive Workplace Support Centre to prevent sick leave, work-related stress and burnout and getting more focus on the 24-h human.

The project gave managers more insight into how they could work to promote health and get support for organizational preventive measures.

Rn1: When we are planning to make changes in our company, we try to work together with NAV—we get some support from them for conducting courses and meetings and so on… Try to be proactive and work with prevention instead of taking things up when the damage has happened.

3.2.3. Networking and Exchange of Experience

The development project initiated network meetings for managers. These meetings gave managers an opportunity to share experiences with others and reduced the sense of loneliness in handling workplace issues.

Se3: Yes, spontaneously, it was interesting to see that it did not really matter what kind of business you worked in, it was a bit of the same problem. I felt like that… in my role, I am very lonely… And, I felt somewhere there that they (other managers) are sitting with the same thoughts and speculations as I do… But that was, like the very biggest thing I felt, that you are not alone. Besides, it is nice to be able to come there…

Unrelated to their participation in the development project, some managers were part of networks of entrepreneurs. In these networks, they had sparring partners with whom they could discuss difficult issues regardless of their nature.

Managers stressed how useful it was to discuss issues with managers from other sectors because the element of competition was removed, allowing managers to openly discuss challenges they faced in their workplaces.

Rs2: Yes, that’s why we say it’s good that we are from different industries. Then one can be more open.

The external circumstances that influenced health promotion efforts in the workplace were common across the different SSEs. Managers had to consider a variety of factors that extended beyond the aspects and skills learned through the development project. Exchanging experiences in these networks helped managers to expand their way of thinking and solve complex problems.

Rn5: Support group with 12 leaders. We use that a lot… there, we are good at sharing. We report problems or issues. Every 6 weeks… different experiences, you always have some of them who have been involved in something similar. Yes, those meetings get priority… over time, we get to know each other well in that group. And then you know who has expertise in what… then we phone them… when I have the same problem a bit later, then I remember that.

3.2.4. Market Fluctuations

Managers needed to pay attention to the market competition, prices and fluctuations, in addition to any information about health promotion they learned in the development project. As managers, they needed to consider the entire enterprise and its market situation when they drew up their priority list, including how to comply with public regulations and company requirements.

The managers had to persevere, working to retain customers and to keep their market position at the same time as keeping their employees healthy and productive. This resulted periodically in high workloads both for managers and employees and for this reason managers could find it difficult to prioritise health-promotion measures at the workplace.

Rs1: Because it is a difficult thing I think, as a small business owner, to say no. You depend on having work, after all, and maybe you have some repeat customers that you desperately want to look after—to help at any price. Because otherwise, you know, maybe the customer will go to someone else, and then maybe you will lose that customer. And so, to some extent you become dependent on your customers’ needs, and that is the biggest problem… I think many people feel that the workload is heavy, stressful… Yes, you notice that people are, or, the staff are a bit stressed out. You work a lot of overtime to meet those deadlines.

3.2.5. Regulations and Requirements

Norway and Sweden have working environment legislation for all private and public enterprises. Many enterprises therefore have agreements with OHS units. Business managers are aware that if they do not follow government regulations they may lose customers and the market may respond negatively.

Rn6: The HSE (health, safety and environment) part is there as a requirement. Yes, you must have all that in place, yes.

Interviewer: So when you submit a tender, you also need to state that you… RN6: That we have the HSE part in place, yes. And that may also be verified by the big contractors.

It was the manager’s job to ensure that the enterprise complied with all relevant rules and regulations. This could be burdensome because these were not adapted to the reality of SSEs. The Labour Regulations and Labour Inspection imposed the same requirements for equipment and the working environment on small and large enterprises, which was burdensome for some managers.

Rs5: We have exactly the same requirements from legislators as (name of large competitor), and what do they have? They have huge staffs for both personnel and the environment and things like that… We do not have the resources. But one day we must be at the environment office, the next day it’s the working environment—then it’s personnel, the payroll office, the planning department, logistics’… But we aren’t familiar with these complex, complex EU formulations. I would have thought there could be a lighter variant of the package for small companies. We have inspection, not every year, we are… they see that we are well prepared when it comes to the various documents and that we keep track of certain things.

3.3. Leadership Strategies

To work with WHM was challenging for the managers. Participating in the project helped them develop their leadership skills and identify strategies for a healthy workplace. Thus, managers received support from the OHS on how to develop their WHM, and to become more sensitive to strengths and limitations of their enterprises. Nevertheless, even if this process gave managers new strategies and skills this came at a cost as managers had multiple tasks and roles to fulfil and had to make decisions about the opportunity costs associated with pursuing WHM in relation to their other responsibilities within the enterprise.

3.3.1. Leadership Skills

The development project included leadership support. Managers received a ‘toolbox’ for how to practice leadership, handle roles, responsibilities and employee relations, which they found useful.

Rn3: …very good people holding the courses actually. So… A step back in time and a bit of theory and challenged us on how we were as people and what we needed to think through. Yes, I think that was very useful. As well as learning something about that, yes, not that it was so very new, but it is so good to focus on that leadership part, because there has not been much of that.

Leadership support provided the opportunity to work with relevant cases to find tailor-made solutions that the managers could apply in the workplace.

3.3.2. Multitasking Leadership

Multiple roles in the enterprise affected the managers in relation to health promotion work. The managers had considerable leeway in shaping the management of the enterprise. At the same time, they had many responsibilities and roles to fulfil. This led to complications and created dilemmas for how to practise leadership at the same time as giving priority to health-promotion measures.

Rs1: The dilemma for the small business owner… having many strings to your bow is the reality…director of personnel, finance, occupational health.

Practising management triggered many stressors, such as long working hours and dilemmas regarding priorities.

Rs5: Above all, it’s that there are many people who are in the same situation in small businesses—you are not alone with your problems. There were a lot of ‘aha!’ moments, everyone has problems of various kinds. Many people have similar problems. Many felt that they were heading towards breaking point.

The environment of the SSE, therefore, created a unique challenge for managers that made it extremely difficult to balance their different work tasks and values. As a result, many managers experienced heavy workloads that, ironically, detracted from their own health in the workplace.

3.3.3. Professionalizing Leadership

Managers said that the development project gave them an opportunity to reflect on their own leadership and become more professional.

Rn1: So that is a kind of shift that creeps in… In parallel with that there is… yes, you see that…we are so many employees that now we should have working-hour arrangements that are a bit clearer. It should be more predictable in every way. So there will be less flexibility than there was before, and yes, totally different. And it is clear that with 10 employees that it is different from with 2 […].

To professionalize and improve their leadership competence was difficult in the SSE context where there is less security and fewer resources for development.

Rn3: …focus on the leadership role in such small enterprises, a leader who is better trained. We are not especially well equipped for this role when we have finished our education. And some go straight into a management job…you can become more secure in the role after all, or less secure too… yes, it’s not something one should take lightly… Responsibility.

3.3.4. A View to the Future

The managers envisioned a different future, where they could find time and space to develop the enterprise into a health-promoting workplace.

Rn6: …things that we don’t mobilize in everyday life because there are a few too many hats to put on. So the fact that someone comes from outside and gets a grip on just those things that maybe have a tendency to get a bit lightweight, the work that doesn’t get your full attention… perhaps we focus most on production in everyday life… health and environment stuff—tends to get put aside.

Some managers expressed the need for different conditions in the external regulatory context so SSEs had better opportunities for developing a health-promoting workplace with reasonable legislative support.

Rs5: Yes the work environment authority, what’s their name? Yes that’s what they’re called, the ones whose rules and regulations we must comply with. It should have been possible to have a function like that for small businesses, medium-sized businesses, and large businesses.

Some managers added that there was no good way to certify SSEs in relation to their healthy workplace practices. Such recognition would provide positive incentives to SSEs and would assist them in prioritizing health promotion.

4. Discussion

This study explores the approaches of SSE managers to dealing with WHM after participating in a health-promoting development project. Research shows that many SSEs do not prioritize OHSM [12] and that they have limited competence in creating health-promoting workplaces [13]. However, we know little about the processes leading to these outcomes for SSEs. By gaining insight into the reality, problems and dilemmas for managers of SSEs in WHM issues, it may be possible to circumvent some of these outcomes. The aim of development projects such as those studied in this research is to address the challenges faced by managers in promoting health in the workplace. Thus, they provide an important source of information about management perspectives.

Before participating in the development project, managers had limited competence in relation to WHM. The network meetings provided an opportunity for dialogue with other managers and the support from the OHS consultants generated greater awareness of WHM. Together these experiences provided managers with tools for developing psychosocial working conditions and improving employee health. However, external factors related to, for example, market fluctuations and managerial demands compromised their capacity to apply WHM.

As demonstrated in the findings, both internal and external surroundings affected managers’ development and practice of WHM. The development projects were valuable in assisting managers to improve WHM internally in their SSEs. It helped managers to improve their skills and achieve more structure in staff appraisals and staff meetings, and to improve their personnel policy. Research shows that active participation from both managers and co-workers is a crucial factor for achieving favourable results in health-promoting projects [21,23]. Managers experienced these projects as a successful method for engaging both co-workers and themselves in a shared vision for a healthier workplace. The projects were particularly successful in raising awareness about preventive measures in a straightforward manner that could be easily implemented. Good health among employees is likely to be associated with an organization with active communication across the entire organization and common values at all levels [44,45]. This creates an environment where employees are indispensable to the business and a satisfying working culture is promoted. Research shows that SSEs have advantages for creating health-promoting workplaces due to their social and organizational attributes [23,24]. Most of the managers interviewed in this study also attested to the positive possibilities in their workplaces, but noted that participation in the project created better internal conditions for improved competence and skills in WHM.

External circumstances influenced the managers in their attempts to develop a health-promoting workplace. Although the managers valued the content of the projects and intended to prioritize WHM, they needed to consider a range of other forces. In particular, market competition and the position of the company in the sector strongly affected the managers’ priorities and latitude for practising WHM. Regardless of their industry or enterprise, managers reflected an ambiguity about how to develop a healthy workplace and concurrently proceed with maintaining the business. Sometimes, market fluctuations or customer requirements resulted in heavy work demands on the managers. Managers needed to balance demands, expectations from the market, as well as government and industry regulations with the demands and ambitions arising from participating in the health-promoting project. These findings are in line with earlier research in several ways. Being a manager in an SSE comes with responsibility for a diverse range of business activities [22] and high levels of conflicting work demands combined with long working hours [8,46]. In addition, high economic pressure, lack of financial and personnel resources may be obstacles to prioritizing health-promoting measures [47].

This study indicates that managers may be overloaded with work tasks. The need to meet health promotion or safety requirements as well adds to the burden. This conflict explains the managers’ ambiguity about developing a more health-promoting workplace. In principle, managers were positive about the necessity to prioritize WHM, but found it difficult to implement. Thus, this study has found that managers lacked the capacity rather than commitment to give priority to health-promoting processes. The results also suggest that external supports from services such as OHS, SIA and NAV need to included systems tailored towards SSEs. This would make it easier for managers to commit to and prioritize health-promotion efforts. The managers emphasized that activities in the WHM development project contributed to higher awareness about health and working condition issues. They appreciated information about how to handle WHM and found it valuable to receive guidance from external experts. More importantly, they responded to this support by implementing changes in their workplaces.

The managers described the SSE environment as both a barrier and an opportunity for promoting and creating a health-promoting workplace. OHS was an important consultant partner and supervisor for educating managers and co-workers in health and issues related to working conditions. Research shows that collaboration between OHS and SSEs depends on a continuous dialogue and the willingness of OHS to adjust services flexibly to meet specific needs of their customers [37]. The fact that this health-promoting project created increased collaboration between OHS and the participating SSEs is interesting because both Norwegian and Swedish studies have found that OHS are mainly used for individual health examinations and employee health care [14,36]. The Norwegian managers had mainly positive experiences with the support received from the NAV in prevention of disease and sickness absence. For a Norwegian SSE, it is possible to have an agreement with NAV to be an inclusive workplace, and therefore receive financial support for rehabilitation and prevention measures. Swedish managers showed a more lukewarm attitude towards the support from SIA. This is consistent with other studies showing that SSE managers have a low degree of support from the Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate [34]. This means there may be potential in exploring how the Swedish social security system organizes, supports and considers the conditions surrounding the SSE in state-financed rehabilitation and preventive regulations.

The findings in this study suggest that managers of SSEs often search for support in professional and industry networks for how to address challenging issues. During the project, to varying degrees, managers took part in network meetings to discuss management, working conditions or health issues in the workplace. To share and exchange experiences with other managers, particularly those from other sectors, seemed to be an important mechanism for increasing managers’ competence concerning health-promoting workplaces. This result is in line with other research [33,48]. However, for long-term benefits, trust and close relations in the networks are important [12,49]. A study by Limborg and Grøn [50] found advantages in networks of enterprises from the same sector for finding solutions to sector-specific challenges. However, in this study, we found benefits from removing the potential for competition among similar businesses. The network meetings in the project not only provided guidance and an arena for consulting other managers; they also, together with the OHS consulting, provided a space for being more reflective and professional about leadership. Some managers valued participating in other networks where human resource issues were discussed together with business issues.

The managers experienced rules and regulations about occupational health and safety as not adapted to SSEs, which is consistent with other research [33]. For this reason, SSE managers expressed problems in finding information about tools for working with health issues [12]. Thus, it is import to develop information systems and adapted models of regulation for SSEs. Reliable knowledge and support from external consultants was a key driver for occupational health and safety interventions in SSEs [39].

Engaging in a health-promotion project can improve managers’ awareness, formalized expertise and actual competence. However, the challenge is how managers apply these qualifications in the company, and their leadership practices. During the project, managers received assistance in identifying, sorting and prioritizing key elements for success in WHM. In addition, managers gained insight and expertise in methods for dealing with challenges related to health promotion. However, this study reveals why it is still difficult to implement health-promotion strategies and give them priority among other tasks. The managers expressed a need for support from different OHS actors, as well as time and incentives to develop the enterprise into a health-promoting workplace.

This article contributes new insights into this field of knowledge. It highlights issues related to developing SSEs, and challenges for dealing with WHM that influence the managers in their leadership. A crucial question for future research is how positive WHM processes can be sustained in the long term in SSEs after learning from a development project.

4.1. Limitations and Strength of the Study

A strength of the study is that it does not aim to extend findings derived from selected samples to people at large, but rather to transform and apply the findings to similar situations in other contexts [51]. Note that a particular interpretation is one of many possible, but we judge the findings in this study to be transferrable to small-scale managers in similar contexts. Although the sample is heterogeneous, the managers were representative of SSEs because they comprised a range of different enterprises. The purpose of sampling in qualitative research is to ensure maximum variability that can inform the relevance of the findings rather than to seek homogeneity.

The managers were not selected at a national level, but represent SSEs managers from one geographical area in Norway and another in Sweden. The data collected are retrospective, and therefore biased by interviewees’ selective memories and reflections after participating in the development project. Thus, the findings should be interpreted with caution. A limitation could be that the managers were already active participants in a WHM development project and might therefore have a positive attitude to working with these issues that might not be found in other managers. However, they could also represent common manager attitudes and problems in SSEs. The generalizability of these findings should be examined in future research.

4.2. Conclusions and Implications

This study shows that managers in SSEs approach WHM with ambiguity due to competing internal and external demands. They faced significant challenges in simultaneously dealing with multitasking leadership, managing financial decisions, work legislation, staff development and maintenance of business. Nevertheless, the projects appeared to support managers to develop new skills and competence and thereby a more reflexive approach and readiness to create a health-promoting workplace.

One implication of this study is the recognition that managers in SSEs need to exchange experiences, discuss workplace health issues with other managers and receive guidance from OHS consultants. One way of addressing this need could be through developing local and regional networks for these issues. A second implication is that tailor-made models and strategies for supporting managers in SSEs may assist in promoting health in these workplaces. OHS consultants should be able to support the managers concerning WHM processes and to give individual leadership support. Such support should also focus on how the managers could improve their own working conditions and work-life balance. There is also a need to tailor processes to the SSE context. A final implication is that further research is needed on work life and practices in SSEs to identify possibilities and obstacles for WHM using various methods and theoretical approaches.

Acknowledgments

We owe special gratitude to the managers in SSEs in Norway and Sweden who generously shared their experiences with us.

Author Contributions

All the four authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, and interpretation of data. All authors drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content, and made final approval of the version to be published. The second and forth author performed all interviews.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. This work was supported by AFA Insurance Sweden (Dnr 130190).

References

- Bridge, S.; O’Neill, K.; Martin, F. Understanding Enterprise, Entrepreneurship and Small Business; Palgrave MacMillan: Hampshire, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Davidsson, P. Researching Entrepreneurship; Springer Science + Business Media, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield, I. Self-Employment in Europe; Institute for Public Policy Research: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. The European Industrial Relations Dictionary. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sv/observatories/eurwork/industrial-relations-dictionary (accessed on 3 August 2012).

- Statistics Norway. 2014. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/virksomheter-foretak-og-regnskap/statistikker/bedrifter/aar/2015-01-23 (accessed on 11 December 2015).

- Statistics Sweden. SCB:s Företagsregister 2011; Company Register; Statistics Sweden: Örebro, Sweden, 2011.

- Grant, S.; Ferris, K. Identifying sources of occupational stress in entrepreneurs for measurement. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2012, 4, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordenmark, M.; Vinberg, S.; Strandh, M. Job control and demands, work-life balance and wellbeing among self-employed men and women in Europe. Vulnerable Groups Incl. 2012, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U.; Roesler, U. Health of entrepreneurs versus employees in a national representative sample. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 717–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornberger-Dankvardt, S.; Ohlson, C.-G.; Westerholm, P. Arbetsmiljö-Och Hälsoarbete I Småföretag—Försök till Helhetsbild (Arbetsliv I Omvandling 2003:1); Work Environment and Work for Health in Small Enterprises—An Attempt to Provide an Overview; National Institute of Working Life: Stockholm, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Frick, K.; Langaa Jensen, P.; Quinlan, M.; Wilthagen, T. (Eds.) Systematic Occupational Health and Safety Management; Elsevier Science Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hasle, P.; Limborg, H.J. A review of the literature on preventive occupational health and safety activities in small enterprises. Ind. Health 2006, 44, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torp, S.; Moen, B.E. The effects of occupational health and safety management on work environment and health: A prospective study. Appl. Ergon. 2006, 37, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinberg, S.; Torsdatter Markussen, L.; Landstad, B.J. Cooperation Between occupational Health Services and Small-Scale Enterprises in Norway and Sweden: A Provider Perspective. Workplace Health Saf. 2017, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, P.; Winkler, B.; Dunkl, A. Creating healthy working environment with leadership: The concept of health-promoting leadership. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breucker, G. Small, Healthy and Competitive. New Strategies for Improved Health in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises; Report on the Current Status of Workplace Health promotion in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs); Federal Association of Company Health Insurance Funds: Essen, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, B.L.; Hall, N.; Watson, N. Health at work in small and medium sized enterprises. Issues of engagement. Health Educ. 2005, 105, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacEachen, E.; Kosny, A.; Scott-Dixon, K.; Facey, M.; Chambers, L.; Breslin, C.; Kyle, N.; Irvin, E.; Mahood, Q. The small Business Systematic Review Team. Workplace health understandings and processes in small businesses: A systematic review of the qualitative literature. J. Occup. Rehabilit. 2010, 20, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, M.; Karlqvist, L. Small and Medium Sized Enterprises. A Literature Review of Workplace Health Promotion; National Institute for Working Life: Stockholm, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shain, M.; Kramer, D. Health promotion in the workplace: Framing the concept; reviewing the evidence. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 61, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasle, P.; Bager, B.; Granerud, L. Small enterprises—Accountants as occupational health and safety intermediaries. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Network for Workplace Health Promotion (ENWHP). The Lisbon Statement on Workplace Health in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs); Adopted in Lisbon, June 2001; ENWHP: Essen, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Meggeneder, O. Style of management and the relevance for workplace health promotion in small and medium sized enterprises. J. Public Health 2007, 15, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D.; McMahan, S.; Philips, K. Workplace Health Promotion in Small Businesses. In Health Promotion in the Workplace; O’Donnell, P., Ed.; Delmar Thomson Learning: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 493–540. [Google Scholar]

- Hessels, J.; Rietveld, C.A.; van der Zwan, P. Self-employment and work-related stress: The mediating role of job control and job demand. J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 32, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, K.; Schrey, K.; Ahonen, G.; Kaleva, S. The effects of promoting Organizational health on worker well-being and organizational effectiveness in small and medium-sized enterprises. In Healthy and Productive Work—An International Perspective; Murphy, L.R., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2000; pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, O.H.; Hasle, P.; Bach, E. Working in small enterprises: Is there a special risk. Saf. Sci. 2007, 45, 1044–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E.K.; Day, A.L. Building Healthy Workplaces: Where We Need to Be. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2005, 37, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.; Landstad, B.J.; Gundersen, K.T.; Vinberg, S. Leader-based workplace health interventions—A before-after study in Norwegian and Swedish small-scale enterprises. Int. J. Disabil. Manag. 2016, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Norwegian Working Environment Act. Lov Om Arbeidsmiljø, Arbeidstid Og Stillingsvern Mv. (Arbeidsmiljøloven); LOV-2015-12-18-104; Arbeids-og Sosialdepartementet: Oslo, Noway, 2015. (In Norwegian) [Google Scholar]

- The Swedish Working Environment Act. Arbetsmiljölag; SFS nr. 2014:659; Swedish Government: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014. (In Swedish)

- Nitsche, S. New Ways of Providing Occupational Health Management via a Network for Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises. In Healthy at Work; Wiencke, M., Cacace, M., Fischer, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Bern, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- The Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate [Inspektionen för Socialförsäkring]. Arbetsgivare I Små Företag. En Intervjustudie Om Deras Erfarenheter Av Sjukskrivningsprocessen; Inspektionen för Socialförsäkring: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012. (In Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson, K.; Andersson, I.-M.; Josephson, M. Swedish entrepreneurs’ use of occupational health services. Workplace Health Saf. 2011, 59, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moen, B.E.; Hanoa, R.O.; Lie, A.; Larsen, Ø. Duties performed by occupational physicians in Norway. Occup. Med. 2015, 65, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, L.; Sjöström, J.; Antonsson, A.-B. Successful collaboration between occupational health service providers and client companies: Key factors. Work 2015, 51, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvorning, L.; Hasle, P.; Christensen, U. Motivational factors influencing small construction and auto repair enterprises to participate in occupational health and safety programs. Saf. Sci. 2015, 71 Pt C, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagno, E.; Masi, D.; Leao, C.P. Drivers for OSH interventions in small and medium-sized enterprises. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2016, 22, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, A.; Charmaz, K. The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory; SAGE: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; SAGE: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hjälmhult, E.; Giske, T.; Satinovic, M. (Eds.) Innføring I Grounded Theory; Introduction to Grounded Theory; Akademika Forlag: Oslo/Trondheim, Norway, 2014. (In Norwegian) [Google Scholar]

- SFS 2003:460. Lag Om Etikprövning Av Forskning Som Avser Människor. [Act on Ethical Review of Research Involving Humans]. Available online: http://www.riksdagen.se/sv/Dokument-Lagar/Lagar/Svenskforfattningssamling/Lag-2003460-om_etikprovning_sfs-2003-460/ (accessed on 3 August 2012). (In Swedish).

- Alvesson, M. Organisational culture and health. In Healthy at Work; Wiencke, M., Cacace, M., Fischer, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Bern, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kets de Vries, M.F.R. The Leadership Mystique: Leading Behavior in the Human Enterprise; FT/Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson, K.; Vingård, E.; Josephson, M. Self Rated Health and Working Conditions of Small-Scale Enterprisers in Sweden. Ind. Health 2007, 45, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tappura, S.; Syvänen, S.; Saarela, K.-L. Challenges and Needs for Support in Managing Occupational Health and Safety from Managers’ Viewpoints. Nord. J. Work. Life Stud. 2014, 4, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, I.-M.; Hägg, G.M. Arbetsmiljöarbete i Sverige 2004. En Kunskapssammanställning över Strategier, Metoder Och Arbetssätt för Arbetsmiljöarbete; Work Environment Approach in Sweden 2004; A Breakdown of Strategies, Methods and Work Practices for Work Environment; National Institute of Working Life: Stockholm, Sweden, 2006; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Street, C.; Cameron, A.-F. External Relationships and the Small Business: A Review of Small Business Alliance and Network Research. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2007, 45, 239–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limborg, H.J.; Grøn, S. Networks as a Policy Instrument for Smaller Companies. Nord. J. Work. Life Stud. 2014, 4, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research, Principles and Methods, 7th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).