Abstract

The 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda and its aftermath led to large-scale individual traumatization, disruption of family structures, shifts in gender roles, and tensions in communities, which are all ongoing. Previous research around the world has demonstrated the transgenerational effects of mass violence on individuals, families and communities. In Rwanda, in light of recurrent episodes of violence in the past, attention to the potential ‘cycle of violence’ is warranted. The assumption that violence is passed from generation to generation was first formulated in research on domestic violence and child abuse, but is receiving increasing attention in conflict-affected societies. However, the mechanisms behind intergenerational transmission are still poorly understood. Based on qualitative research with 41 mothers and their adolescent children, we investigated how legacies of the 1994 genocide and its aftermath are transmitted to the next generation through processes in the family environment in Rwanda. Our findings reveal direct and indirect pathways of transmission. We also argue that intergenerational effects might best be described as heterotypic: genocide and its aftermath lead to multiple challenges in the children’s lives, but do not necessarily translate into new physical violence. Further research is needed on how children actively engage with conflict legacies of the past.

1. Introduction

When a child asks you: What happened to your family? Who killed them? Isn’t it [sibyo]?! In the future they will say, ‘It is these ones who killed our grandfathers, our aunts, our cousins.’ They will say, ‘Long ago Hutus killed Tutsis, they were in power of such and such…; let us also kill them.’Mother and genocide survivor, aged 40, Rwanda.

This study is inspired by the concern about the potential of recurring mass violence in conflict-affected societies [1]. Many scholars of the Great Lakes Region in central Africa, for instance, refer to repeated outbreaks of violence along ethnic and political lines [2,3,4]. In Rwanda specifically, the infamous genocide against the Tutsi of 1994 followed earlier episodes of violence along ethnic lines [5]. In 1994, approximately one million of Rwanda’s seven million inhabitants were killed, mostly Tutsi [6]. In the aftermath of the genocide, roughly 120,000 people were arrested and detained as suspected killers [7,8], some of whom were indefinitely or temporarily released under presidential decree. Over time, more than 1,000,000 people faced trial in ordinary and Gacaca courts; as a result, over three hundred thousand individuals were (re-)imprisoned or detained in community work camps [9]—in total 84,896 were sentenced to the Travaux d’Interet General [10]—and many more had to pay reparations to victims [11]. It can thus be presumed that all families in Rwanda have in some way been affected by the genocide and its aftermath—as victims, perpetrators or otherwise—and may struggle with the legacies (See also, [12]).

The history of recurrent episodes of mass violence in Rwanda speaks to literature and theory about the cycle of violence. The theory of the cycle of violence, which refers to the idea that violence is passed on from generation to generation, was first formulated in research on domestic violence and child abuse [13,14] and it receives significant attention in studies investigating the intergenerational continuity of anti-social behavior and offending [15,16]. These studies have shown that experiences as victims or as perpetrators may shape the course of offending later in life and of next generations (see for a literature review, [17]). Furthermore, traditional theoretical perspectives consider processes of homotypic versus heterotypic continuities. Homotypic continuity would be considered the classical idea of ‘violence begetting violence,’ whereas continuities over generations may also be heterotypical. Heterotypic continuity refers to the transmission of violence or other maladapted behaviors that do not become visible in that exact same type of behavior, but may be reflected in other adverse outcomes in the next generation [18]. Such forms of continuity may also entail experiences of victimization in one generation affecting anti-social behavior among the next generation. In conflict-affected societies, the theoretical perspective of the cycle of violence theory is receiving increasing attention [19,20,21,22,23,24]. The mechanisms responsible for intergenerational continuity in violence, however, are still poorly understood in this field [25]. Various studies have revealed that caregivers and parenting matter, both as risk and protective factors [26,27,28,29]. Others have focused more on relations between memory and violence, for instance [30]. Yet research is still scant and findings are inconclusive and sometimes contradictory [25]. The study presented here therefore aims to further the understanding of the mechanisms that may contribute to intergenerational continuities of violence in conflict-affected societies. More specifically, the article investigates the pathways through which experiences of genocide and its aftermath in Rwanda are passed on to the next generation. To understand how the second generation is affected by mass violence and its aftermath, we built on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model on child development [31]. Our focus was on processes of intergenerational transmission in the primary environment in which children grow up, namely the household or the family. We approached the family environment as embedded within the community environment and influenced by the more distal, wider society.

2. Methodology

The article is based on five months of fieldwork research—from July to November 2016—among 41 families. Fieldwork research was conducted in rural areas in four provinces in Rwanda; in seven out of the 30 districts of the country. To facilitate logistics and access, the localities were identified through our local partners (see recruitment procedure below), who were present in eight of the country’s 30 districts; in diverse corners of the country. We included mothers and their (adolescent) children as representing the first and second generation. We focused on mothers rather than fathers for several reasons. Firstly, mothers are seen as children’s primary caregivers in Rwandan society. Also, a recent study on post-genocide traumatization showed that women reported more traumatic experiences than men [32]. Moreover, most people killed during the genocide were men [6] and many other men were tried and imprisoned on genocide related charges [33,34]. This has affected the sex ratio in Rwandan households and society at large [35]. The children included in this study were between 18 and 24 years old. They were born just before or just after the genocide that occurred 22 years ago. This means that they have not consciously experienced the genocide, and can thus be considered part of the second generation. In addition, in order to be able to investigate the mother-child relationship and interactions as potential pathways of transmission, we interviewed only individuals who at the time of the interview lived as children—also an ascribed social position—in their parental home. Field researchers interviewed the youngest child of the household who fulfilled these criteria. This was to limit selection bias.

Respondents were recruited through the community-based sociotherapy program (CBSP), executed by a consortium of three local non-governmental organizations. CBSP seeks to address psychosocial health problems and facilitate reconciliation and social cohesion in the aftermath of war and genocide [36]. Sociotherapists and leaders from the local communities helped to identify potential respondents. Both mothers who participated in the program and mothers who were on the waiting list for participation were included. The sampling strategy ensured diversity and answered to the ethical concern of securing psychosocial referral for respondents if needed. Mothers could belong to different social categories, including genocide survivors, (ex-)prisoners’ wives and returnees, and women who were married, divorced or widowed, for example (see Table 1). They could also belong to different social categories at the same time. For instance, someone could be both a genocide survivor and a prisoner’s wife. Of the 41 mothers who participated in the study, 22 were ex-participants of the community-based sociotherapy program and 19 were on the waiting list. The included mothers were between 38 and 64 years old, with an average age of 50 years. Among the children, 14 were boys and 27 were girls, they were between 18 and 24 years old, with an average age of 20 years. Three girls were mothers themselves. Unmarried, they lived with their child in their mother’s household. The interviewed children’s level of education ranged from primary three to the second year of University. Most of them were no longer in school.

Table 1.

Background information on respondents.

Data was collected by five Rwandan field researchers who were chosen after a rigorous selection process. All of them have obtained relevant Bachelor or Master degrees, namely in clinical psychology, sociology, social work, nursing, public health and peace studies & conflict transformation. All had previous experience with qualitative research. Additional training in qualitative research methods was provided. The quality of the data was further secured through on the ground support by a senior researcher (the third author). The local team also ensured (cultural) validation of the interview guide and supported the translation of tools from English to Kinyarwanda.

In each household, three consecutive interviews were conducted. The first interview—with the mother—concerned the household composition, living conditions and key events that had affected the household, including the genocide. The second interview, also with the mother, explored family functioning, parenting practices, family relationships, as well as how these were affected by key events and by the support available in the social environment. The third interview revolved around the same themes and was conducted with the adolescent child. Interviews were held at the home of the respondents, which enabled complementary observational data on living conditions and interactions between the household members. On a few occasions, interviews took place at the workplace of the mother. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by the data collectors, who also translated the first interviews (on household composition, etc.). A professional translator was hired to translate interview data of all second and third interviews into English for processing. (The design of the consecutive interviews was inspired by [29]).

We used Atlas-ti software to analyze the data in three steps. First, the interviews from four randomly selected households were thematically analyzed and then coded by the first and second author. Differences were then discussed and resolved in order to develop a thematic codebook, which was applied to all interviews of all households. Throughout the coding process, we added new codes if needed, after deliberation. In total, we identified 27 codes pertaining to six overarching themes. The codes pointed to the mechanisms of intergenerational transmission of legacies of genocide, which, as a third step, the first author analyzed in detail.

The study obtained official approval from the Rwanda National Ethics Committee (RNEC). All respondents were informed about their rights to participate and withdraw, the use and storage of the data, and they signed informed consent forms prior to the interviews. The process and forms were approved by the Rwandan Ministry of Health and by the Rwanda National Ethics Committee: http://www.rnecrwanda.org/No.552/RNEC/2016. In publications, including this article, all names stated are pseudonyms.

3. Findings

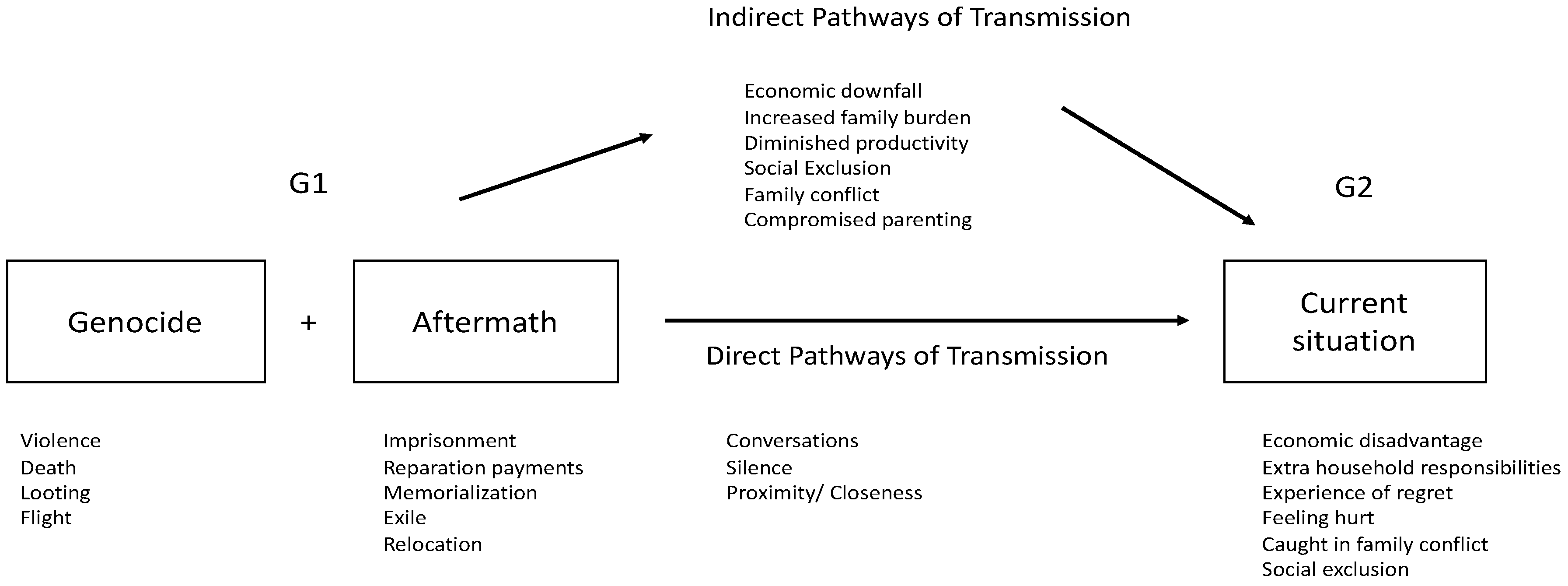

Our findings confirm the profound effects of the genocide and its aftermath on individuals, families and communities in Rwanda [22,34,37,38,39]. Mothers testified to experiencing and witnessing many traumatizing events, and to bearing the psychological, physical, social and economic consequences of the past violence. They articulated clearly and strongly how the past continued to shape their present lives. Their children learned and lived effects of the genocide and its aftermath as well, and in varying degrees expressed connections between their daily preoccupations to what had happened in the dark hours of the past. In this section we describe the different mechanisms in the intergenerational transmission of legacies of genocide and its aftermath that we identified in our findings (see Figure 1). We first describe various ‘indirect pathways of transmission.’ Indirect pathways of intergenerational transmission concern the ways in which the genocide and related events affect the second generation’s socio-ecological environment, and through that, the child. These pertain, firstly, to the economic dimensions of family life, which affect the daily experiences of children of the second generation and include economic downfall, an increased family burden and diminished productivity in our respondents’ perspectives. Other mechanisms relate to interpersonal dimensions and include social exclusion, family conflict and compromised parenting. Subsequently, we describe the ‘direct pathways of transmission’ we identified, namely closeness between parent and child, and intergenerational conversations and silence (cf. [30,40]). The direct pathways of intergenerational transmission concern the ways in which the genocide and its aftermath are reflected upon, reconstructed and communicated or silenced by the mother to the child. In the last part, we take a child-centered perspective and describe how the interviewed children experienced and dealt with the legacies of genocide and its aftermath transmitted in the family environment.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms in the intergenerational transmission of legacies of genocide and its aftermath.

To illustrate our findings, we spotlight the experiences recounted by respondents in one of the interviewed households—“Household 40”. Though each mother and child had their own views and stories of the past and present, the findings in Household 40 are particularly helpful to exemplify our arguments. We also draw on our findings among other households in order to expand upon how the different mechanisms worked and to include elements we found in the other households.

3.1. Introducing Household 40

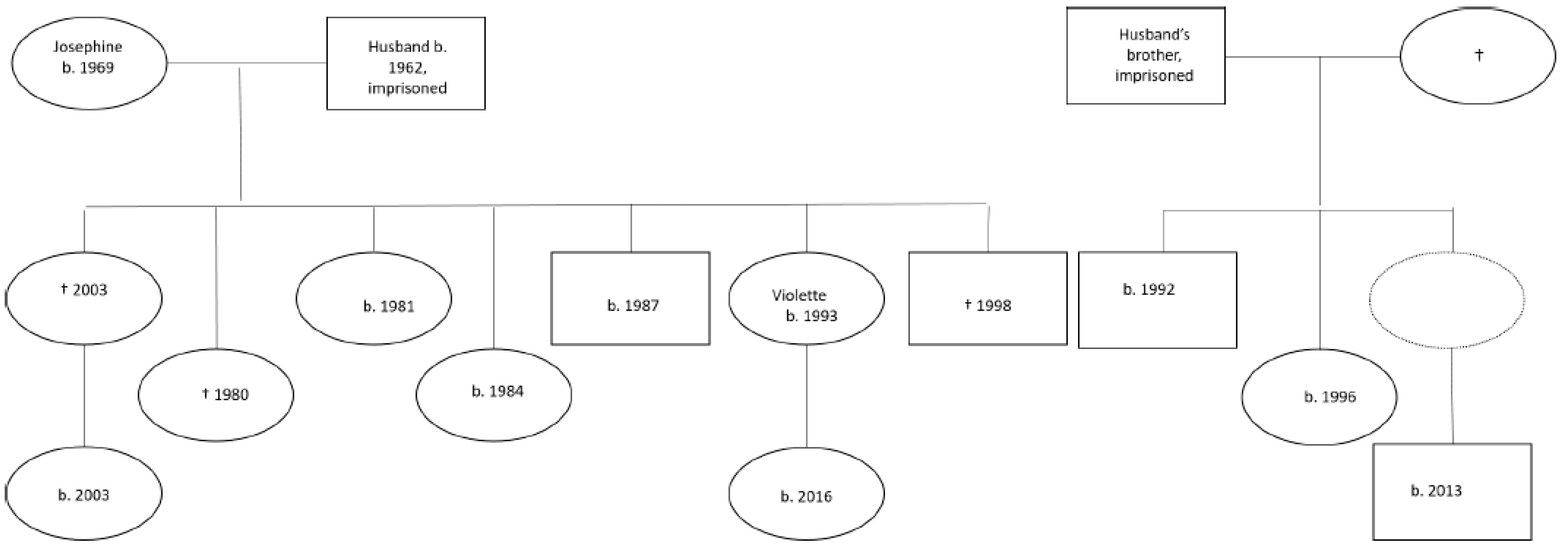

Household 40 is located in a small, rural town in the south-west of Rwanda. In Rwanda, households are often composed of various family and non-family members. Both the extended family system and human loss or imprisonment during and after the genocide, shape who lives together as a family; which is also the case for this particular household. The household counts eight members, namely the 47 year old mother (she is also a grandmother) and seven children aged between a few months and 29 years. The husband is absent. Ten years ago, he was sentenced to more than 35 years’ imprisonment for involvement in genocidal violence. The mother, Josephine, was born from a Tutsi mother and Hutu father. She barely survived persecution, lost her brothers and was eyewitness to the murder of several neighbors. The couple has seven children together, three of whom died due to ill health—although, in the death of a teenage daughter, a few weeks after the girl had given birth, the mother suspects that poison may have been involved. The child of the deceased daughter remains in the household and is 12 years old. The father died without having recognized the child, resulting in his family not resuming any responsibility. Another daughter (Violette) recently gave birth at home. The girl’s partner “didn’t care, it was a problem”. The only remaining son of 29 is also part of the household, but is not often at home. He had started an affair with the second wife of his father (his father had—unofficially—married a second woman). There are three other children. Two are the children of Josephine’s husband’s younger brother, who was also imprisoned for involvement in the genocide. Just after the sentencing, the brother’s wife passed away and other relatives did not want to take the children in. The last child in the household is a grandchild of another younger brother of her husband: “He is like my grandchild”. There is one daughter, married, in Kigali, who supports the family from time to time. For instance, she bought her mother a small plot of land for cultivation. This is their main source of revenue (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Family tree of Household 40.

3.2. Indirect Pathways of Transmission

3.2.1. Economic Downfall

The mother and the interviewed daughter, Josephine and Violette (24 years old) respectively, felt that the most urgent challenges they encountered in their day-to-day life “are those related to poverty”. Many respondents shared this point of view. Mothers struggled especially with providing their children with decent housing, health care costs and school fees. Josephine, for instance, felt that the children:

“…lead a bad life (…) they sleep in a bad place as they are blown by the wind [because there is no proper cover on the house] (…). They have no foam mattress (…) [and] I also look forward to their getting a mutual health insurance cover in order for them to be able to get health care services (…) [and] if they could also further their studies!”

Many families described the lack of resources as a direct consequence of the genocide and the post-genocide justice-related measures. People had lost land, cattle and means, some were ordered to pay reparations to compensate the losses of genocide survivors, and many people had to share land—between those who had stayed in Rwanda and those who had returned after years of exile—or were relocated. In other words, due to a family’s economic downfall accompanying the mass violence and its aftermath, children of the second generation experienced economic disadvantage.

3.2.2. Increased Family Burden

In Household 40, like in many Rwandan households, making ends meet is mostly perceived as a family’s co-responsibility. Generally, all household members are ascribed specific tasks to make the household run smoothly. These include, for instance, procuring income, working the land, sweeping the floor, collecting water or grass, feeding the cow and cooking. Gender, age and childbearing shaped specific responsibilities and tasks. As such, Josephine said about the boy of three years old, “he is still very young, he is not yet capable of doing anything”, and about Violette, “she also gave birth so her responsibilities recently increased”. The distribution of tasks and responsibilities meant that if family members were no longer around, the burden on those remaining increased. Josephine explained, “We work in collaboration according to our number”. In view of this, mothers mentioned how the loss of their husbands due to death or imprisonment meant that they had become the main or only breadwinner. Several mothers, including Josephine, also stressed that they therefore experienced motherhood as a very heavy burden. The loss or absence of extended family members could also affect the family burden. For instance Josephine, due to her husband’s brother’s imprisonment, had three extra children to take care of. In some other families, single mothers spoke about the dilemmas of starting a new relationship after the loss of their husbands: while this could help them improve their economic situation and the family burden balance, it might also mean more children and thus create an extra burden.

3.2.3. Diminished Productivity

One of the reasons why economic downfall and the extra burden on a family were difficult to carry in the years after the genocide were health problems resulting from the mass violence. Some mothers suffered from severe emotional health problems. Josephine ascribed her problems to the experienced negative events—the loss of relatives, witnessing and barely escaping killings, and later, the imprisonment of her husband. Her emotional suffering, she explained, stood in her way of economic development: “You cannot achieve anything as long as your heart is bound. In short, there cannot be any development”.

Sometimes, physical, social and emotional health problems were seen as interconnected. Below is an illustrative interview excerpt, where a mother and genocide survivor, aged 61, explains how her intestinal cancer was caused by the genocide and led to her inability to work:

- Mother:

- I am suffering from bad diseases as a result of genocide; I am no longer able to dig(…) It’s cancer. (…).

- Interviewer:

- They passed some sticks through the vagina?

- Mother:

- No here [FR: she showed me].

- Interviewer:

- Oh sorry, you can put on your clothes.

- Mother:

- The problems of losing my people resulted in disease. It really hurt me. (Mother, genocide survivor, aged 61).

For many mothers, health problems appeared to become progressively disturbing because they were exacerbated by aging. Josephine noted in this regards that, “in these negative events you encounter ‘hurdles’ coupled with old age, and all this holds you back because your strengths are gradually waning (…) I do what I can…nowadays, I do what I can”.

3.2.4. Social Exclusion

Mothers and children regularly mentioned the lack of resources together with the ambition to “improve conditions,” which resonates strongly with the national discourse on Rwanda’s path to development. Accordingly, many mothers and children made mention of national development programs and projects that could help achieve better living conditions. Josephine mentioned projects “happening at the Cell level (…) which help us try to stand on our own feet”. Development initiatives, nonetheless, could also be a source through which the past was rendered present in more piercing ways, as local dynamics could provoke feelings of exclusion. For instance, in relation to Girinka (the one cow per family program), which has the stated objective to benefit all Rwandans who are categorized as poor, Josephine lamented:

“[At] community development work (umuganda), they say: ‘Please choose people who should be given cows.’ Then, when it comes to those with husbands in jail, they say ‘Never! Never!’… Considering this, shh, you ask yourself: ‘It’s not me who committed the crime, it is he who committed the crime. Me and the children didn’t commit any crime.’ I wonder whether I can be victimized for a crime I have not committed (…) You feel stigmatized, saying: ‘Why don’t they receive us while we are all Rwandans?’”

The quote reveals how exclusion from programs may be experienced as a consequence of stigma and discrimination experienced in specific localities—even if official aims are inclusive. The negative effects of stigma and discrimination on attempts to remedy poverty thus indirectly transmit negative effects of the genocide to the second generation. The experience of exclusion rendered past social divisions relevant in the present—also between community members (horizontal)—and they appeared to be accompanied with a strong sense of injustice, as we see for instance in Josephine’s statement above.

3.2.5. Family Conflict

Many households we visited, including Household 40, were single parented. When husbands were still around, and sometimes even when they were in prison, family conflict was recurrently raised as a problem and obstacle. In Household 40 conflicts were not explosive, but still present. Josephine’s husband had already been in prison for almost ten years and he reproached her for not visiting and taking care of him properly. Josephine also felt that she and their children should visit him regularly and bring him a gift as custom demanded, but she was unable to afford this. It was an important source of tension between the spouses, but it also affected Josephine’s relationship with her children, particularly with her son, whom she reproached for not taking over responsibilities in this regard: “I cannot tell him ‘try to get something to take to the prisoner.’ Never! It is me who toils to get it, but you will see that it is too tough for me”.

Often, in conflicts between spouses, children got caught in the middle. For instance, some mothers recounted how their husbands did not love their children because of the conflict between the spouses: “[My neighbor] and others told me: ‘That man does not hate children. If he hated them, he would not be staying at home. He hated them because you also hated him’” (Wife of ex-prisoner, aged 52). In other families, we saw that children, particularly boys, meddled in the conflict to try and protect their mothers against their fathers’ abuse. Some fathers were said to have threatened to kill their wife and children. In one such family, conflict between father and son got so bad that an aunt decided to adopt the son and take him to Uganda, where she lived.

Mothers and children mentioned various reasons for the origin or escalation of family conflicts, besides the (temporary) separation of husbands and wives due to imprisonment that was the cause of trouble in Household 40. For instance, there were mothers who pointed to the bad temper or drinking habits of their husbands, sometimes suggesting a relationship between this and the psychological hardship the men had experienced in prison. One mother rather thought that her ethnicity may have been the cause of the conflicts that had occurred between her and her husband and could also be the reason for the separation with her children. She explained that her husband had never taken care of their children, as they and their mother “looked alike”. Speaking about her children, she said, crying:

“After genocide, I stayed with my children but they misbehaved, they started to smoke [weed], they stole things in my house and sold them, finally they left for good. Up to now, I don’t know where they live. I’m always sad because of my children, I don’t know if they hate me because I’m a Tutsi”.(Mother in mixed marriage, aged 59).

Furthermore, missing family members, because of their social importance, were seen to affect conflict between spouses. For instance, one mother explained the threats and abuse she experienced from her husband as a result of her having lost her family during the genocide, as it made her unable to give her husband what she ought to give:

“I often tell myself: the reason why he doesn’t care about me is maybe because he doesn’t have a brother-in-law so that they can talk to each other as brothers-in-law, so they can share a drink, so they can do whatever…so that when he has a new baby he receives drinks like other parents who have new babies; he has just to find something for himself when we get a new baby…I tell myself: maybe the reason is because I don’t have parents (…) In short, you suspect something about yourself”.(Mother in mixed marriage, aged 40).

Traditional mechanisms in society that served to de-escalate, have also been affected by the genocide and its aftermath. Several mothers pointed out that the loss of extended family members, who played an important role in conflict mediation, hampered family conflict resolution. In this regard, one mother explained that because her parents and siblings had been killed, she had no place to flee to when she and her husband needed to cool off.

3.2.6. Compromised Parenting

The damaged family composition as a direct consequence of the genocide and its aftermath, the physical and emotional health problems of mothers and the family conflict, harmed children also through their effects on (compromised) parenting. For instance, Josephine said that because her “heart is bound,” she was very strict and sometimes used abusive words to her children. Reflecting on how she had been raising her children until recently, she explained: “I would not tolerate any mistake however small it might be. I would immediately insult him, saying: ‘Shit! Dead people are better than you.’” Violette also recognized that her mother was not always up to the task of parenting. She described that in those moments, roles were reversed:

“I am affected in the sense that time comes when she remembers the past experiences she went through. This requests me to be close to her and to advise her as I can. (…) You will see her with a strange behavior. When she is in this situation, I get close to her, saying, ‘Dear mother, even though my father is in prison, we should not continue to be overwhelmed by grief, we should see to it that we can meet this need by ourselves without thinking of who would have met it for us.’”

Mothers also explained that their parenting was affected negatively by the fact that they were alone in raising their children. For instance, this mother felt unable to monitor her children properly:

“Checking up on the children…in any case, when you are a single person, there are certain things that you miss. You may not know how the children have spent the day because they had no one to check up on them; when I come back home, I’m tired, so you find they cannot be checked up on… this is important, uuh; because of this, some of them may behave differently because you don’t have time to check up on them. You find that it is a problem. Those are the effects that you can see on your side. Sometimes you are unable to meet their wishes as well as you should because you don’t have the means or because you have no time, things like that”.(Wife of prisoner, paid reparations, aged 44).

Family conflict took its toll on the care given to children. As a consequence of the constant fighting with her husband, the mother quoted below felt unable to interact with her children like other parents would:

“The consequence [of the conflict with their father] is, as you see, the children are grown up; they tell me: but, Mama, will it be possible one time for you to chat with us as our parents? Do you know that at such and such’s place (for their classmate), do you know that they told them this or that, they told them old folktales? Will you happen one time to talk to us, because you are always quarrelling, will you really talk to us as the children you gave birth to? I tell them: as for me, you will see me for some time and I will chat with you. They say: So you would tell us old stories, about kings in the past? Heh, I say, ‘I will tell you about it.’”.(Mother in mixed marriage, aged 40)

3.3. Direct Pathways of Transmission

3.3.1. Conversations and Silence

The genocide and related events were also transmitted to the next generation through the sharing or silencing of experiences of the troubled past. Mothers expressed diverging opinions on how best to deal with the question of whether or not to tell their children what had happened. Some mothers told us that they preferred not to talk about the past events. They used statements like “It is in the past,” “Bygones are bygones” and “It is history,” to explain why the genocide and its aftermath, or what had happened to them and their family specifically, was not a topic of conversation with their children. Other mothers rather downplayed the events, perhaps in an attempt to protect their children from learning how their loved ones had suffered. They said things like: “I have transcended it”, “Others have suffered more”, or “It is my problem”.

Some mothers who felt that it was better not to tell their children, would, unintendedly, still confront their children with such stories:

“The genocide has more effects because, for example, when a child asks for money, I tell him: ‘If the genocide had not taken your father, I would now be relieved, and you would address your problems to him.’ Sometimes it happens that I say this by accident, but I feel that I’m not fair to them because I shouldn’t even say it since they were too young and don’t even know what happened”.(Genocide survivor, aged 52).

There were also mothers who felt that, even though it was difficult, they should tell their children, because silence stood in the way of their relationship. They needed their children to understand why they were sometimes distressed or absent. For instance, the mother and genocide survivor (aged 47) quoted below explained how, after years of silence, explaining her children what grieved her, had been helpful:

“This year particularly, I dared taking my children to the memorial site. When I uttered my testimony on the dark moments of the genocide, the children have come to realize that my behavior is seriously hindered by the genocide and they encourage me. At the moment, such an event no longer threatens me to the extent of disturbing my children.(Genocide survivor and in a mixed marriage, aged 47).

Others again felt that children should learn about the genocide to prevent such a fate from happening again. Yet, even some children felt that this was not without risk: “The task here is to explain to children how things happened so that they understand and work hard so that it never occurs again. However, after being informed about what happened, this may also trigger conflicts” (Daughter of genocide survivor, aged 22).

3.3.2. Proximity

A sense of proximity or a close bond between mothers and their children could also serve to transmit legacies of the genocide to the next generation. The following quote from a daughter of a genocide survivor, is illustrative. The girl describes how she feels for her mother’s memories of suffering: “Another negative effect is that an attackers’ group assailed her. When she remembers this, it also hurts us” (Daughter of genocide survivor, aged 23). Mothers described that specific events provoked the traumatic memories, which children noticed. In this regard, the interviews showed that many mothers were struggling especially in the national period of commemoration, which commences each year in April and lasts 100 days, as long as the genocide lasted. The first week, the so-called mourning week, is often experienced as most traumatic. The suffering provoked by bad memories were so strong that some mothers tried not to listen to the radio during this week. The memories could also be triggered throughout the year by more everyday events, such as the experience of poverty, of not being able to pay school fees or health costs, or because people ran into the killers of family members or into the people who had provided testimonies against their loved ones. Furthermore, Josephine described that her husband being on trial, thirteen years after the genocide, had triggered memories of the bad experiences she had lived through during the genocide. In these moments, words or silences were not always necessary for children to feel for, or rather with, their mothers. The sense of proximity and closeness to mothers seemed to stand in opposition to some children’s relationships with their fathers, especially when they were or had been in prison. Some children appeared to have little contact with their fathers; simply because they were not there. This seemed to be the case for Violette. She described a highly ambivalent picture of her relationship with her father, noting his absence, but holding on to an ideal of how their relationship would have been had he not been in prison: “if he were here, he would have collaborated with us”. In other families, separation with fathers resulted from children getting caught in the middle of spousal conflicts.

3.4. How Children Respond to the Legacies

The findings thus far described reveal various important mechanisms through which legacies of the genocide and its aftermath are passed on to the next generation. Most of these mechanisms indirectly reach children, such as their mother’s decreased productivity or the larger family burden. Other mechanisms, such as the conversations and silences or proximity, reveal direct pathways of transmission from mothers to children. Nonetheless, children experience and interact differently with the legacies they encounter in their family environment. All children that we interviewed had been confronted with legacies of the genocide and related traumatic events. In this regard, we found that many children suffered from economic disadvantage, experienced heavy family responsibilities, regretted missing out on rights and opportunities, felt hurt and loss with their mothers, suffered from family disruption because of conflicts between spouses, stigma and social exclusion in the community and country, as well as could feel emotionally torn between staying loyal to the family and the past and moving on to a better and harmonious future. In this section we take a child-centered perspective to improve our understanding of children’s responses.

Firstly, with regards to economic disadvantage, many children recounted that their needs could not or not easily be met by their caregiver(s). Often, but not always, they knew that this was due to their family’s living conditions following the genocide and its aftermath. For instance, when Violette’s father was imprisoned, it became very difficult for her family to afford school fees. Violette, nonetheless, did manage to finish her secondary school studies, unlike many other children. Still, the constant worry about school fees had taken an emotional toll on her:

“Previously, life was bad because after my father was imprisoned, we were left with our mother only (…) I was worried and would go to school worried; I was worried, wondering whether I would get school fees. But I have completed my studies and even though I am jobless, I am not as worried as I was before”.

Various other children explained that they responded to their family’s economic hardship and the difficulties to redress it—because of their mother’s ill health or because of the lack of helping hands—by assuming extra household responsibilities themselves. As such, one boy we interviewed, explained that when his father was imprisoned, he felt compelled to “toil to support our mother and improve our living conditions”. He dropped out of school to breed and sell hens “lest my mother should become a beggar” (Son of wife of ex-prisoner, aged 22). In Household 40, we saw that Violette adopted parental responsibilities by becoming an important go-to person in case of economic distress and related negative emotions of her mother and her siblings. Her mother said about her:

“For instance, when [Violette] realizes my loneliness, she approaches and talks with me. When I tell her “I don’t see what to do with [12-year old grand-daughter], I don’t have a pen…” Also, raising an orphan child is a complex responsibility. When I scold her a little bit, she becomes sad, and starts moaning, saying, ‘I don’t know what would be the situation if my parents were still alive.’ You will see Violette talking with us, saying: ‘You, (…) it’s true that you are an orphan, but you are not the only one. Leave aside this story of you being an orphan because you are not the only person on this world who is sad, you are not the only one who is poor. Therefore, calm down. Where my mother is, she watches for you. Let us do this so that we get the pen”.

Notably, a number of children, especially boys, described how these family responsibilities were at odds with their own ambitions to prepare for independent householding. Given that we interviewed children who were still living at their parental homes, but were reaching an age at which marriage and independent householding was starting to be expected, several children mentioned that they worried about how to reach this. In fact, we saw that this concern was shared by many mothers as well.

The experience of regret was another consequence that children struggled with. Children realized that they, for instance, should have had grandparents, uncles or a father, but that they missed out on that normalcy. Or, they expressed regret about not having been to school although that ought to have been their right, or about having to spend their own earnings on products that their caregivers should have been providing for them:

- Interviewer:

- “What do you consider to be your own most salient problem in daily life—what disturbs your peace?

- Child:

- In my life, this cannot miss because as I sit here I should be at school like other children, but it did not work. (Son of genocide survivor and ex-prisoner, aged 24).

“The situation was very fine [when my father was still alive]. But nowadays, when I have worked for some coins, I use them to buy body lotion, but if he were alive, he would himself give me money, saying: ‘my daughter, go and buy that body lotion there’. And I would use [my] money for another purpose”.(Daughter of returnee and widow, aged 18).

Various mothers and children noted that children felt hurt because their mothers were hurt. For instance, in the following interview excerpt, we read that a mother sees that her children feel badly because of her own losses:

“My relationship with my children, even those negative events you’ve talked about, I don’t go into them much. This is because they often ask me: Mama, don’t you have brothers? I say: No, they killed him. Why did they kill him? I said of course during the war they killed him. (…) I see that this is also a consequence for my children, the fact that I don’t have parents”.(Mother in mixed marriage, aged 40).

Some children recounted how they felt sad about seeing or being reminded of the conflict and violence between their parents. As mentioned, often, many children also suffered directly from these situations, for instance because children had to move out to reduce conflict (see page 10, above) or because parents (temporarily) abandoned the family:

- Interviewer:

- “Is there a problem you [often] think about?

- Girl:

- Hehehehe (she laughed). Except in the past when my father would beat my mother. These days when they quarrel, I think about this and this makes me very sad.

- Interviewer:

- How old were you when he would beat her?

- Girl:

- I was in form 4; that is when my mother left and deserted us”. (Daughter of ex-prisoner, 19 years).

Furthermore, several children experienced stigma or social exclusion because of their mother’s or father’s reputation in the community. One girl explained that their family was not well liked in the community because her mother had testified against some neighbors who had subsequently been imprisoned. The girl and her family were thus left to fend for themselves without support or friendship. Children of tried perpetrators also felt to be stigmatized or excluded from, for instance, social and material support projects. Violette said in this regard that it was for her the most important form of injustice, or “violence”, that she experienced in her life. She said: “I feel that we should not be accountable for what my father did; if he was imprisoned perhaps after having committed a crime, we, we don’t know any [thing about it]”.

Josephine had attempted to protect her children by not telling that her husband’s label (“brand”) as perpetrator had been, she thought, behind the reason for them to be excluded from important support programs: “If you tell [the children] about this, they can feel that they are not liked by ‘Rwanda.’” Still, many children appeared aware of such processes of stigma and social exclusion, and this caused children to experience the same or even stronger hurdles in their relationships with community members. For instance, in one family we encountered a boy who felt personally hurt when he saw that the killers of his father had been welcomed by his mother at their home: “When I saw him, I didn’t show that I was angry, but I don’t know how I felt; I felt bad (…) On that day, I even wanted to leave this place. I was unhappy and somehow traumatized” (Son of genocide survivor, aged 24). Another example, in the following interview excerpt, shows how a child feels torn between remaining loyal to what had happened to his/her mother and taking advantage of the benefits of positive community relations with neighbors and peers.

- Boy:

- “So she would tell us those who killed her parents; she would tell us their living conditions before, in those hard moments. And when I thought about it as a child, I felt I wouldn’t look at the person who persecuted my mother; I felt we shouldn’t talk to each other; this affects me negatively in relation to the other child whereas I could learn something from him; so we leave out the issues; we talk just about ordinary topics. That is how I am affected.

- Interviewer:

- Yes…does it affect your relationship with your siblings in the extended family?

- Boy:

- In the extended family, I feel the consequences when she tells all of us about it; let’s say you are my friend from the same [background] group, we children understand fast, this can be a reason for me not to talk to the other child and you realize that it is in fact a conflict; you say: such and such person did this and that to us; that is why I feel we shouldn’t talk to each other. For example, even if you are classmates, you say: that one, I can’t even sit with him”. (Son of genocide survivor, aged 18).

It should be noted further that children, notwithstanding the struggles with legacies of violence, were also active in trying to mitigate and remedy some of the harm they identified. We see this with, for example, the above quoted boy:

“The thing I can change personally is to try to make her understand that those events have passed; that there is no option, so she should forget about them progressively. I would show her that she should get out of it so that she can make it possible for us to have good relationships with others”.(Son of genocide survivor, aged 18).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In this article we explored how experiences of genocidal violence and its aftermath are being transmitted to the next generation in Rwanda. Our research question and analysis was inspired by concerns in conflict-affected countries that violence may recur and the theoretical model of the cycle of violence. The model has originally been developed in contexts of family violence and has proven to be valuable for understanding continuity in offending. Since recently, the cycle of violence theory is receiving increasing attention in conflict-affected contexts [19,20,21,22,23,24,26,27,28,29], perhaps because rates of relapse into conflict are worrying [1]. Overall, insight into the mechanisms fostering intergenerational continuity is still limited, however. Farrington [41], speaking about intergenerational continuity of criminal behavior, provides a number of potential underlying mechanisms, which may be more or less relevant for conflict-affected contexts. He argues that (i) there may be shared risk factors among members of multiple generations; (ii) these risk factors may interact with environmental risk factors; (iii) assortative mating may play a role; (iv) social learning (i.e., violent attitudes or behavior) may be underlying within the family home environment; and (v) genetic factors may mediate the effects of transmission from parent to child [41]. Further empirical research that investigates and contributes to theorizing the cycle of violence in conflict-affected societies is important, for various reasons. Firstly, unlike in societies not affected by conflict, violence is not restricted to families and individuals but is also organized by state and non-state parties and occurs at societal level as well [42], and there is reason to assume that broader societal conflict may transfer to families from different socio-ecological levels and vice versa [43,44]. In conflict-affected countries, substantial higher levels of domestic or familial violence often occur [45,46]. In this regard, research in contexts marred by chronic violence—in Western and non-Western settings—has shown that family dynamics and caregiving may impact children’s functioning and their role in reproducing violence [28,47,48,49]. Together with other risk factors or vulnerabilities at different system levels, compromised caregiving may contribute to putting society at risk for new episodes of violence or conflict [22,24,29]. Second, in conflict-affected societies, there may be difficulties in disentangling potential confounding effects of, for example, cultural differences or poverty [25]. For example, Baldwin et al. [50], who explored effects of societal conflict on intergenerational transmission of poverty—through transitory poverty—suggested that conflict may drive processes of intergenerational poverty while poverty drives conflict. Careful analysis of relevant mechanisms in conflict-affected societies is thus needed.

In this article we explored how legacies of the genocide and its aftermath are being transmitted across generations in Rwanda. We focused on mechanisms of transmission in the family environment, the primary environment in which children grow up, and conceptualized this environment as connected to community and society system levels. Our findings showed direct and indirect pathways of intergenerational transmission (see Figure 1). We distinguished the different mechanisms analytically, although the way they are experienced by members of Household 40 and others is that in practice, they are deeply entangled. Among the families we interviewed, indirect mechanisms were especially dominant. They were constantly present through the daily challenges mothers and children encountered in making ends meet, working towards improved living conditions and effects of the compromised household composition, such as experienced in the functioning and relationships of and between parents as well as with children. As Bronfenbrenner’s theory on child development postulates, such repetition is an important condition for leaving an imprint on the child [31]. It is furthermore in line with more general theoretical perspectives on intergenerational continuity just mentioned [41], namely, that processes of social learning (e.g., silencing/ communication, stigmatization, social exclusion, parenting behaviors and strategies such as connectedness and availability) and shared risk factors or disadvantages (i.e., transitional poverty) may underlie intergenerational continuity. With regards to the direct mechanisms of intergenerational transmission, we found for instance, the conversations or silences about what had happened in the past. These findings remind of Kidron’s [40] ethnographic work in Israel on how silences transmit knowledge from Holocaust survivors to their descendants. We also identified the potential role of proximity and distance in the relationships of children with parents through which hurt of the past could be directly passed to the next generation. These direct mechanisms were affected by irregular confrontation with people in the community who had harmed one’s family, or the moments of sentencing and release of prisoners. Yet they were triggered especially by the yearly recurring period of national commemoration and mourning. In this regard, further research may help identify in more detail the relationships between (official) commemoration—memory—and intergenerational processes (cf. [30]).

Our in-depth qualitative approach, which included three interviews per household, enabled substantive insight into the family dynamics in Rwandan households. However, our findings are based on a relatively small sample of households in Rwanda. The diversity created through our sampling approach, which entailed the inclusion of households that were geographically spread across Rwanda, and of mothers pertaining to a variety of social categories, helped to ensure a comprehensive view on relevant mechanisms. Nonetheless, the majority of respondents were women, which may have influenced our findings to some degree. Gender “likely plays complex roles in the context of extreme adversity” ([51], p.240), [52]. Furthermore, as mentioned in the methodology section, we also included in our sample both households who had undergone sociotherapy and those who had not (yet). In other words, the sample can be said to be similar to a clinical sample of people seeking treatment, which may have influenced respondents’ abilities to recognize the impact of the genocide or they may have experienced its impact to a greater extent than others.

Our findings have helped to identify several promising directions for further research. Firstly, quantitative research may enable an identification of which of these mechanisms of transmission are most prevalent or pertinent for negative outcomes, and which mechanisms may be most prevalent among specific social categories. Second, we need to better understand the dynamic dimensions of legacies and their transmission. For instance, mothers especially identified changes as they were aging, making some (indirect) mechanisms more present or acute with the passing of time (e.g., diminished productivity due to worse health) (cf. [12]), whereas other mechanisms diminished in presence or strength. To give an example of the latter, one mother felt that after she had been able to take her children to a memorial site and discuss with them what had grieved her, her parenting—an indirect mechanism of transmission—improved. Third, children were coming of age too, meaning that their needs and their possibilities to interpret and (re)act to the legacies developed over time. Insight into these changes over time are important in order to identify opportunities for intervening in the cycle of violence, which may be strongly connected to children’s life stages [50,51]. Fourth, further research is needed to refine insight into the various outcomes of societal violence. In particular, prospective studies are needed to examine the long-term effects of these legacies.

This study is among the first to study intergenerational transmission of genocide and its aftermath in Rwanda so shortly after events have taken place. Our findings give some insight into how children experienced and responded to legacies they encountered. They suggest that intergenerational legacies in Rwanda can best be understood in terms of so-called heterotypic continuity: genocide and related events leading to multiple challenges in the children’s lives, but, notwithstanding the concern, not (yet) necessarily translating into new physical violence. For instance, we showed that children suffered from the economic challenges in terms of obtaining basic commodities like body lotion or in terms of their possibilities to go or continue school, that they assumed heavy family responsibilities—sometimes to the extent that they could not start preparing for independent householding—felt regret about missing out on normalcy and opportunities, had suffered from disruption in their family caused by conflicts between their parents, and experienced stigma and social exclusion in the community because of their parents’ reputation. Some of these findings may be considered risk factors for maladaptive behavior in the future. For instance, it is known that family cohesion and specific caregiving practices such as monitoring, supervision, involvement and supportive or close parent-child relationships may promote prosocial behavior and positive, civic engagement [52,53], whereas family conflict, abuse and neglect may worsen negative effects of exposure to community violence and contribute to processes that reproduce violence [21,54,55,56]. Given that the majority of respondents were women and girls, future research should investigate how gender will influence findings. Various studies show, for instance, that expressions of psychological distress can differ among boys and girls [51,52,56,57].

Our findings also underline that children were not passive recipients of the legacies passed on by older generations, but actively interpreted and interacted with the world around them; sometimes taking on their parents’ generation’s experiences as their own and other times attempting to transform these, for instance by creating bonds with peers whose own parents had harmed their family in the past. Further research is needed to better understand how children may overcome negative effects of intergenerational transmission (resilience) [51]. In particular, research would benefit from investigating how children forget, adopt or transform the legacies of the earlier generation into their own lives.

Our study contributes to empirical research that systematically identifies mechanisms of intergenerational transmission of legacies of genocide and its aftermath in Rwanda. Therewith, we aim at contributing to adapting and improving the cycle of violence theoretical perspectives to conflict-affected settings, and thus strengthening efforts through which these potential cycles may be broken.

5. Research Ethics Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975. It was approved by the Rwandan Ministry of Health and by the Rwanda National Ethics Committee: http://www.rnecrwanda.org/No.552/RNEC/2016.

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. Before the start of each interview, subjects were informed verbally and through an ‘informed consent’ form about the research objectives and process as well as their rights to participate. They were explained that they could refrain from answering specific questions or withdraw at any moment. Informed consent was obtained from both mothers and children. Subjects were also informed that the information obtained would be used for research purposes only and that reporting would not contain information that could be traced back to individuals. As such, names used in the manuscript are fictitious. We also notified subjects that we would transcribe, anonymize and securely save the interviews and audio files, in line with data management guidelines of the NSCR.

Respondents were selected through CBSP and were either former participants or on the waiting list for enrolment. This ensured that respondents had access to trained community sociotherapists, if necessary. To enable research uptake for improving interventions, findings have been shared with stakeholders in the Netherlands and with CBSP staff and its implementing partners in Rwanda. Preparations are made for further dissemination of results in Rwanda.

Acknowledgments

This research was performed as a collaboration between the Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement (NSCR) and Community Based Sociotherapy Programme in Rwanda (CBSP, a consortium of Prison Fellowship Rwanda (PFR), EAR Byumba and Duhumurizanye Iwacu Rwanda). Generous funding was provided by I-Wotro, W08.400.2015.140. Furthermore, we express our gratitude to our respondents for their willingness to share their time and impressive stories with us. We also thank our team of interviewers in the field, Theophile Sewimfura, Jeanine Nyinawabega, Veronique Mukakayange, Jeannette Kangabe and Augustin Musafiri. We benefited from the help of Juvenal Rubegwa who translated interviews from Kinyarwanda to English. Furthermore, we thank CBSP, in particular Bishop Gashagaza Deo as executive director of PFR, and the CBSP team in the Kigali office and their local counterparts, who helped the Netherlands-based team interpret findings and accompanied them in fruitful discussions during their visit to Rwanda.

Author Contributions

All five authors contributed substantially to the design of the study, the production, analysis, or interpretation of the results, and/or preparation of the manuscript; Lidewyde Berckmoes developed the methodology of the research, provided feedback on the data collection process, coded and analyzed the data and prepared the manuscript; Veroni Eichelsheim conceived of the project, developed the methodology, provided feedback on the data collection process, coded the data and contributed to their analysis. Furthermore, she provided comments to the paper; Theoneste Rutayisire contributed to the methodology, particularly in terms of ensuring cultural appropriateness, coordinated the data collection process on the ground, and provided comments to the analysis and the paper; Annemiek Richters conceived of the project and provided feedback and suggestions throughout the research process; Barbora Hola conceived of the project, ensured overall coordination, provided feedback on the data collection process, contributed to the analysis of the data and provided comments to the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Collier, P.; Elliott, V.L.; Hegre, H.; Hoeffler, A.; Reynal-Querol, M.; Sambanis, N. Breaking the Conflict Trap: Civil War and Development Policy. In A World Bank Policy Research Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/13938/567930PUB0brea10Box353739B01PUBLIC1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 12 September 2017).

- Lumsden, M. Breaking the Cycle of Violence. J. Peace Res. 1997, 34, 277–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uvin, P. Life after Violence: A People’s Story of Burundi; African Arguments; Zed Books: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Berckmoes, L.H. (Re) producing Ambiguity and Contradictions in Enduring and Looming Crisis in Burundi. Ethnos J. Anthropol. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamdani, M. When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda; Fountain Publisher Ltd.: Kampala, Uganda, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rwanda Ministry for Local Government. The Counting of the Genocide Victims: Final Report; Ministry for Local Government, Department for Information and Social Affairs: Kigali, Rwanda, 2002.

- Jones, N. The Courts of Genocide, the Politics and the Rule of Law in Rwanda and Arusha; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, P.H. The Gacaca Courts, Post-Genocide Justice and Reconciliation in Rwanda: Justice without Lawyers; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hola, B.; Brehm, H.N. Punishing Genocide: A Comparative Empirical Analysis of Sentencing Laws and Practices at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), Rwandan Domestic Courts and Gacaca Courts. Genocide Stud. Prev. Int. J. 2016, 3, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwishyaka, J.L. Abantu Barenga Ibihumbi 30 Bakatiwe Gukora TIG Baburiwe Irengero Batayikoze. Available online: www.igihe.com (accessed on 7 June 2017).

- National Service of Gacaca Jurisdictions. In Report on the Activities of the Gacaca Courts; National Service of Gacaca Jurisdictions: Kigali, Rwanda.

- Both, J. Conflict Legacies: Understanding Youth’s Post-Peace Agreement Practices in Yumbe, North-Western Uganda. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherland, 21 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Widom, C.S. The cycle of violence. Science 1989, 244, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, A.; McClay, J.; Moffitt, T.E.; Mill, J.; Martin, J.; Craig, I.W.; Taylor, A.; Poulton, R. Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science 2002, 297, 851–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.; Thornberry, T.P. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent involvement in delinquency. Criminology 1995, 33, 451–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, A.A. The relationship between adolescent physical abuse and criminal offending: Support for an enduring and generalized cycle of violence. J. Fam. Violence 2005, 20, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, D.P. Family Influences on Delinquency. In Juvenile Justice and Delinquency; Springer, D.W., Roberts, A.R., Eds.; Jones and Bartlett: Sudbury, ON, Canada, 2011; pp. 203–222. [Google Scholar]

- Berzenski, S.R.; Yates, T.M.; Egeland, B. A Multidimensional View of Continuity in Intergenerational Transmission of Child Maltreatment. In Handbook of Child Maltreatment; Volume 2 of the Series Child Maltreatment; Korbin, J.E., Krugman, R.D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Weingarten, K. Witnessing the effects of political violence in families: Mechanisms of intergenerational transmission and clinical interventions. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2004, 30, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betancourt, T.S.; Williams, T. Building an evidence base on mental health interventions for children affected by armed conflict. Intervention 2008, 6, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palosaari, E.; Punamaki, R.; Qouta, S.; Diab, M. Intergenerational effects of war trauma among palestinian families mediated via psychological maltreatment. Child Abus. Negl. 2013, 37, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieder, H.; Elbert, T. Rwanda—Lasting imprints of a genocide: Trauma, mental health and psychosocial conditions in survivors, former prisoners and their children. Confl. Health 2013, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, M.; Neuner, F.; Elbert, T. Transgenerational consequences of PTSD: Risk factors for the mental health of children whose mothers have been exposed to the Rwandan genocide. International. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saile, R.; Ertl, V.; Neuner, F.; Catani, C. Does war contribute to family violence against children? Findings from a two-generational multi-informant study in Northern Uganda. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catani, C. War at Home—A Review of the Relationship between War Trauma and Family Violence. Verhaltenstherapie 2010, 20, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewirtz, A.; Forgatch, M.; Wieling, E. Parenting practices as potential mechanisms for child adjustment following mass trauma. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2008, 34, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.J.; Tol, W.A.; De Jong, J.T.V.M. Indero: Intergenerational trauma and resilience between Burundian former child soldiers and their children. Fam. Process 2014, 53, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betancourt, T.S.; McBain, R.K.; Newnham, E.A.; Brennan, R.T. The intergenerational impact of war: Longitudinal relationships between caregiver and child mental health in postconflict Sierra Leone. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 1101–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berckmoes, L.H.; De Jong, J.T.V.M.; Reis, R. Intergenerational transmission of violence and resilience in conflict-affected Burundi: A qualitative study of why some children thrive despite duress. Unpublished work.

- Argenti, N.; Schramm, K. Remembering Violence: Anthropological Perspectives on Intergenerational Transmission; Berghahn Books: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Rugema, L.; Mogren, I.; Ntaganira, J.; Krantz, G. Traumatic episodes experienced during the genocide period in Rwanda influence life circumstances in young men and women 17 years later. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, P.; Kaufman, Z.D. (Eds.) After Genocide, Transitional Justice, Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Reconciliation in Rwanda and Beyond; Hurts Publishers: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schindler, K. Who Does What in a Household after Genocide? Evidence from Rwanda; Discussion Paper No. 1072; German Institute for Economic Research: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rutayisire, T.; Richters, A. Everyday suffering outside prison walls: A legacy of community justice in post-genocide Rwanda. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 120, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Community Based Sociotherapy. Available online: www.sociotherapy.org (accessed on 30 June 2017).

- Umubyeyi, A.; Mogren, I.; Ntaganira, J.; Krantz, G. Women are considerably more exposed to intimate partner violence than men in Rwanda: Results from a population-based, cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health 2014, 14, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingelaere, B. Inside Rwanda’s Gacaca Courts: Seeking Justice after Genocide; The University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sarabwe, E.; Richters, A.; Vysma, M. Marital conflict in the aftermath of genocide in Rwanda: An explorative study in the context of community-based sociotherapy. Interv. Int. J. Ment. Health Psychosoc. Work Couns. Areas Armed Confl. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidron, C.A. Toward an Ethnography of Silence: The Lived Presence of the Past in the Everyday Life of Holocaust Trauma Survivors and Their Descendants in Israel. Curr. Anthropol. 2009, 50, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrington, D.P. Developmental and life-course criminology: Key theoretical and empirical issues. The 2002 Sutherland Award Address. Criminology 2003, 41, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson-Gómez, J. The Sound of Barking Dogs: Violence and Terror among Salvadoran Families in the Postwar. Med. Anthropol. Q. Int. J. Anal. Health 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, S.; Thorpe, R.; Tol, W.; Fonseca, M.; Silove, D. Testing a cycle of family violence model in conflict-affected, low-income countries: A qualitative study from Timor-Leste. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 130, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, E.M.; Goeke-Morey, M.C.; Schermerhorn, A.C.; Merrilees, C.E.; Cairns, E. Children and Political Violence from a Social Ecological perspective: Implications from Research on Children and Families in Northern Ireland. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 12, 16–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richters, A.; Sarabwe, E. Everyday partner violence in Rwanda: The contribution of community-based sociotherapy to peaceful family life: Original contribution. Afr. Saf. Promot. 2014, 12, 18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Orero, M.B.; Heime, C.; Cutler, S.J.; Mohaupt, S. CPRC Working Paper 71 & CPRC Annotated Bibliography 4. In The Impact of Conflict on the Intergenerational Transmission of Chronic Poverty: An Overview and Annotated Bibliography; Chronic Poverty Research Centre: Manchester, UK, 2007. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08c0eed915d622c0010c7/71Baldwin_Orero_et_al.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2017).

- Gorman-Smith, D.; Tolan, P. The role of exposure to community violence and developmental problems among inner-city youth. Dev. Psychopathol. 1998, 10, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fergus, S.; Zimmerman, M.A. Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2005, 26, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodkind, J.; LaNoue, M.; Lee, C.; Freeland, L.; Freund, R. Involving parents in a community-based, culturally grounded mental health intervention for American Indian youth: Parent perspectives, challenges, and results. J. Commun. Psychol. 2012, 40, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunar, D.; Kagitcibasi, C.; Leckman, J.; Britto, P.; Panter-Brick, C.; Pruett, K. Is early childhood relevant to peacebuilding? J. Peacebuild. Dev. 2013, 8, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Narayan, A.J. Child development in the context of disaster, war, and terrorism: Pathways of risk and resilience. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 227–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, E.M.; Merrilees, C.E.; Taylor, L.K.; Mondi, C.F. Developmental and Social-Ecological Perspectives on Children, Political Violence, and Armed Conflict. Dev. Psychopathol. 2017, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, L.K.; Townsend, D.; Merrilees, C.E.; Goeke-Morey, M.C.; Shirlow, P.; Cummings, M. Adolescent civic engagement and perceived political conflict: The role of family cohesion. Youth Soc. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, E.M.; Taylor, L.K.; Merrilees, C.E.; Goeke-Morey, M.C.; Shirlow, P. Emotional insecurity in the family and community and youth delinquency in Northern Ireland: A person-oriented analysis across five waves. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 57, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlap, E.; Sturzenhofecker, G.; Sanabria, H.; Johnson, B.D. Mothers and daughters: The intergenerational reproduction of violence and drug use in home and street life. J. Ethn. Subst. Abus. 2004, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lösel, F.; Farrington, D.P. Direct protective and buffering protective factors in the development of youth violence. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43, S68–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bongers, I.L.; Koot, H.M.; Van der Ende, J.; Verhulst, F.C. The normative development of child and adolescent problem behavior. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003, 112, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).