The Role of Heart Rate Levels in the Intergenerational Transmission of Crime

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Crime Runs in the Family

1.2. Underarousal: Fearlessness and Stimulation-Seeking

1.3. Heart Rate Levels as a Mediator

1.4. Heart Rate Levels as a Moderator

1.5. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

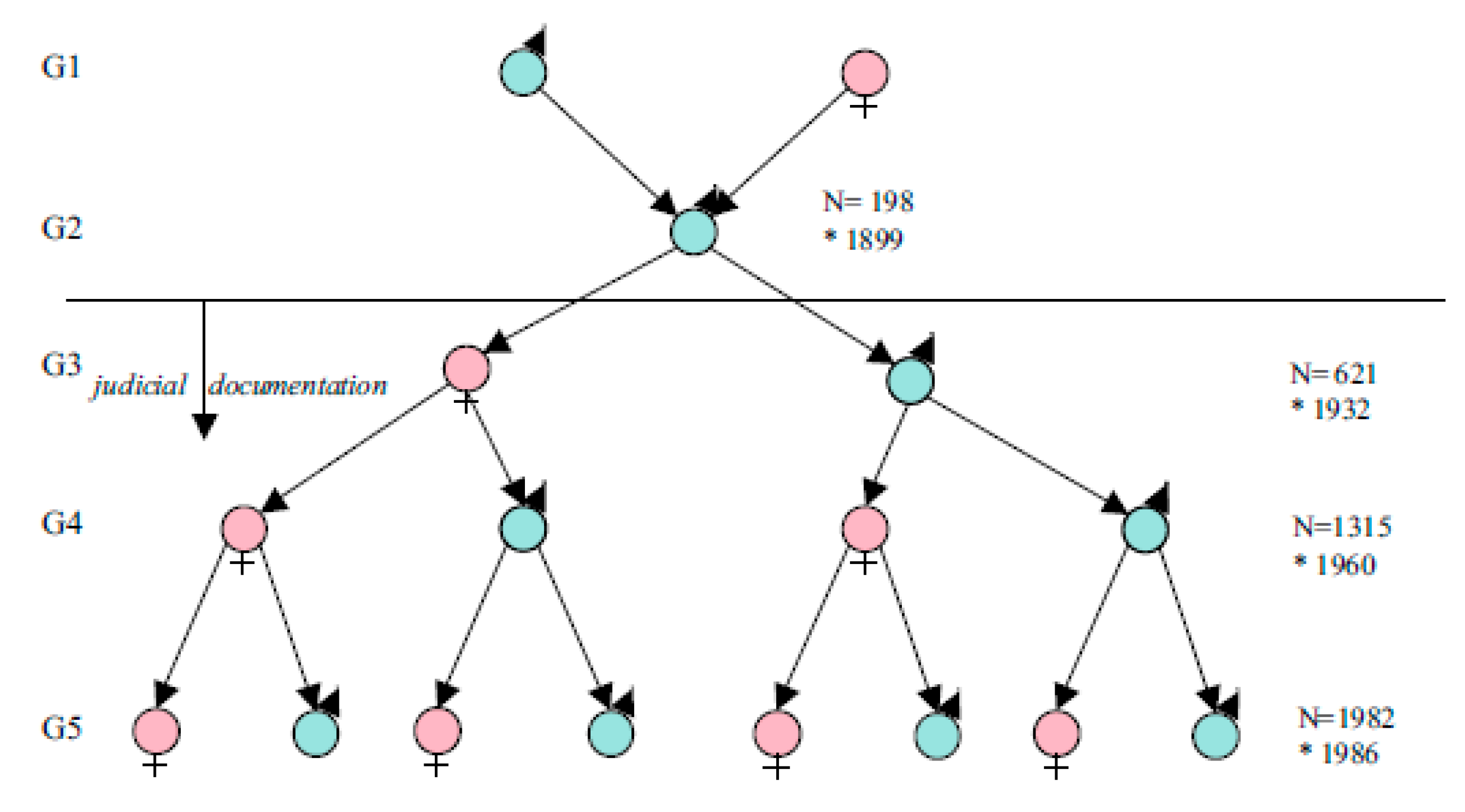

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Intergenerational Transmission of Crime

3.3. Heart Rate Levels

3.4. Heart Rate Levels as a Mediator

3.5. Heart Rate Levels as a Moderator

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dugdale, R.L. The Jukes: A Study of Crime, Pauperism, Disease, and Heredity; Putnam: New York, NY, USA, 1877. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, H.H. The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeble-Mindedness; The Macmillan Company: New York, NY, USA, 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Bijleveld, C.C.J.H.; Wijkman, M.D.S. Intergenerational continuity in convictions: A five-generation study. Crim. Behavi. Ment. Health 2009, 19, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrington, D.P.; Barnes, G.C.; Lambert, S. The concentration of offending in families. Leg. Criminol. Psychol. 1996, 1, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Rakt, M.; Nieuwbeerta, P.; de Graaf, N.D. Like father, like son. The relationships between conviction trajectories of fathers and their sons and daughters. Br. J. Criminol. 2008, 48, 538–556. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, J.; Raine, A. Heart Rate Level and Antisocial Behavior in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2004, 43, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sijtsema, J.J.; Nederhof, E.; Veenstra, R.; Ormel, J.; Oldehinkel, A.J.; Ellis, B.J. Effects of family cohesion and heart rate reactivity on aggressive/rule-breaking behavior and prosocial behavior in adolescence: The Tracking Adolescents’ Individual Lives Survey study. Dev. Psychopathol. 2013, 25, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Weijer, S.G.A.; Bijleveld, C.C.J.H.; Blokland, A.A.J. The intergenerational transmission of violent offending. J. Fam. Violence 2014, 29, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latvala, A.; Kuja-Halkola, R.; Almqvist, C.; Larsson, H.; Lichtenstein, P. A longitudinal study of resting heart rate and violent criminality in more than 700,000 men. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, J.; Hallal, P.C.; Mielke, G.I.; Raine, A.; Wehrmeister, F.C.; Anselmi, L.; Barros, F.C. Low resting heart rate is associated with violence in late adolescence: A prospective birth cohort study in Brazil. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrington, D.P. Developmental criminology and risk-focused prevention. In The Oxford Handbook of Criminology; Maguire, M., Morgan, R., Reiner, R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Weijer, S.G.A.; Beaver, K.M. An Exploration of Mate Similarity for Criminal Offending Behaviors: Results from a Multi-Generation Sample of Dutch Spouses. Psychiatr. Q. 2017, 88, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akers, R.L. Social Learning and Social Structure: A General Theory of Crime and Deviance; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beaver, K.M. Biosocial Criminology: A Primer, 2nd ed.; Kendall/Hunt: Dubuque, IA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, C.J. Genetic contributions to antisocial personality and behavior: A meta-analytic review from an evolutionary perspective. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 150, 160–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrington, D.P.; Coid, J.W.; Murray, J. Family factors in the intergenerational transmission of offending. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2009, 19, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, D.C.; Farrington, D.P. The familial transmission of criminal convictions. Criminology 1997, 35, 177–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, D.P.; Jolliffe, D.; Loeber, R.; Stouthamer-Loeber, M.; Kalb, L.M. The concentration of offenders in families, and family criminality in the prediction of boys’ delinquency. J. Adolesc. 2001, 24, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornberry, T.P.; Freeman-Gallant, A.; Lizotte, A.J.; Krohn, M.D.; Smith, C.A. Linked lives: The intergenerational transmission of antisocial behavior. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2003, 31, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornberry, T.P.; Freeman-Gallant, A.; Lovegrove, P.J. Intergenerational linkages in antisocial behaviour. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2009, 19, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornberry, T.P. The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree (or does it?): Intergenerational patters of antisocial behavior—The American Society of Criminology 2008 Sutherland Address. Criminology 2009, 47, 297–325. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Rakt, M.; Ruiter, S.; de Graaf, N.D.; Nieuwbeerta, P. When does the apple fall from the tree? Static versus dynamic theories predicting intergenerational transmission of convictions. J. Quant. Criminol. 2010, 26, 371–389. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Rakt, M.; Nieuwbeerta, P.; Apel, R. Association of criminal convictions between family members: Effects of siblings, fathers and mothers. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2009, 19, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beijers, J.E.H.; Bijleveld, C.C.J.H.; van de Weijer, S.G.A.; Liefbroer, A. ‘All in the family?’ The relationship between sibling offending and offending risk. J. Dev. Life-Course Criminol. 2017, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisell, T.; Lichtenstein, P.; Långström, N. Violent crime runs in families: a total population study of 12.5 million individuals. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raine, A. Antisocial behavior and psychophysiology: A biosocial perspective and a prefrontal dysfunction hypothesis. In Handbook of Antisocial Behavior; Stoff, D.M., Breiling, J., Maser, J.D., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Raine, A. The Psychopathology of Crime: Criminal Behavior as a Clinical Disorder; Academic Press Inc.: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, M. Sensation Seeking: Beyond the Optimal Level of Arousal; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington, D.P. The relationship between low resting heart rate and violence. In Biosocial Bases of Violence; Riane, A., Brennan, P.A., Farrington, D.P., Mednick, S.A., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Raine, A.; Venables, P.H.; Mednick, S.A. Low resting heart rate at age 3 years predisposes to aggression at age 11 years: Evidence from the Mauritius Child Health Project. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 1457–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raine, A.; Venables, P.H.; Wiliams, M. Relationships between central and autonomic measures of arousal at age 15 years and criminality at age 24 years. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1990, 47, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadsworth, M.E.J. Delinquency, pulse rates and early emotional deprivation. Br. J. Criminol. 1976, 16, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, T.E.; Caspi, A. Childhood predictors differentiate life-course persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways among males and females. Dev. Psychopathol. 2001, 13, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, T.A.; Keller, S.; Franklin, T.W.; MacMillan, S.N. Low Resting Heart Rate and Antisocial Behavior. Crim. Justice Behav. 2009, 36, 1125–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, A.; Venables, P.H.; Wiliams, M. High autonomic arousal and electrodermal orienting at age 15 years as protective factors against criminal behavior ate age 29 years. Am. J. Psychiatry 1995, 152, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lorber, M.F. Psychophysiology of Aggression, Psychopathy, and Conduct Problems: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 531–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, W.G.; Piquero, A.R.; Farrington, D.P. Does resting heart rate at age 18 distinguish general and violent offending up to age 50? Findings from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. J. Crim. Justice 2013, 41, 213–219. [Google Scholar]

- Choy, O.; Raine, A.; Venables, P.H.; Farrington, D.P. Explaining the Gender Gap in Crime: The Role of Heart Rate. Criminology 2017, 55, 465–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portnoy, J.; Farrington, D.P. Resting heart rate and antisocial behavior: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 22, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, P.H. Autonomic and central nervous system factors in criminal behavior. In The Causes of Crime: New Biological Approaches; Mednick, S.A., Moffitt, T.E., Stack, S.A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Choy, O.; Raine, A.; Portnoy, J.; Rudo-Hutt, A.; Gao, Y.; Soyfer, L. The mediating role of heart rate on the social adversity-antisocial behavior relationship: A social neurocriminology perspective. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2015, 52, 303–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, P.A.; Raine, A.; Schulsinger, F.; Kirkegaard-Sorensen, L.; Knop, J.; Hutchings, B.; Rosenberg, R.; Mednick, S.A. Psychophysiological protective factors for male subjects at high risk for criminal behavior. Am. J. Psychiatry 1997, 154, 853–855. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Vries-Bouw, M.; Popma, A.; Vermeiren, R.; Doreleijers, T.A.H.; van de Ven, P.M.; Jansen, L.M.C. The predictive value of low heart rate and heart rate variability during stress for reoffending in delinquent male adolescents. Psychophysiology 2011, 11, 1596–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moelker, R.; Olsthoorn, P.; Miepke Bos-Bakx, M.; Soeters, J. From Conscription to Expeditionary Armed Forces: Trends in the Professionalization of the Royal Netherlands Armed Forces; HDO/KMA: Breda, the Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Imbens, G.; van der Klaauw, W. Evaluating the cost of conscription in the Netherlands. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 1995, 13, 207–215. [Google Scholar]

- Van Schellen, M.; Apel, R.; Nieuwbeerta, P. The impact of military service on criminal offending over the life course: Evidence from a Dutch conviction cohort. J. Exp. Criminol. 2012, 8, 135–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggen, H.; van der Heide, W. Criminaliteit en Rechtshandhaving 2004; WODC/Boom Juridische Uitgevers: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, M.; Taggart, P. Vagotonicity of violence: Biochemical and cardiac responses to violent films and television programmes. Br. Med. J. 1973, 134, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | Percentage | Total N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any crime | 417 | 53% | 794 |

| Non-violent crime | 396 | 50% | 794 |

| Violent crime | 121 | 15% | 794 |

| Any crime father | 300 | 54% | 557 |

| Non-violent crime father | 282 | 51% | 557 |

| Violent crime father | 70 | 13% | 557 |

| Paternal crime during childhood | 72 | 12% | 557 |

| Paternal violence during childhood | 10 | 2% | 557 |

| Heart rate: low (48–71 bpm) | 251 | 32% | 794 |

| Heart rate: medium (72–75 bpm) | 246 | 31% | 794 |

| Heart rate: high (76–120 bpm) | 297 | 37% | 794 |

| Non-Violent Crime OR (95%-CI) | Violent Crime OR (95%-CI) | All Crime OR (95%-CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paternal non-violent crime | 1.512 (1.054–2.169) * | ||

| Paternal violent crime | 2.192 (1.229–3.907) ** | ||

| All paternal crime | 1.512 (1.057–2.161) * | ||

| Exposure | 1.011 (0.990–1.033) | 0.995 (0.970–1.021) | 1.015 (0.994–1.036) |

| N | 557 | 557 | 557 |

| Heart Rate | Non-Violent Crime OR (95%-CI) | Violent Crime OR (95%-CI) | All Crime OR (95%-CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate: | |||

| High (76–120 bpm) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Medium (72–75 bpm) | 1.124 (0.829–1.523) | 1.508 (0.977–2.327) ** | 1.108 (0.792–1.551) |

| Low (41–71 bpm) | 1.172 (0.849–1.618) | 1.648 (1.099–2.470) * | 1.212 (0.878–1.674) |

| Exposure | 1.006 (0.998–1.015) | 1.002 (0.992–1.011 | 1.010 (1.000–1.019) * |

| N | 794 | 794 | 794 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium vs. High | Low vs. High | Medium vs. High | Low vs. High | |

| Paternal crime during childhood | 0.823 (0.446–1.519) | 0.666 (0.339–1.308) | ||

| Paternal violence during childhood | 0.963 (0.192–4.836) | 1.354 (0.392–4.673) | ||

| Exposure | 0.957 (0.931–0.983) ** | 0.938 (0.911–0.965) *** | 0.957 (0.932–0.984) ** | 0.940 (0.913–0.967) *** |

| N | ||||

| Intergenerational Transmission of: | Low Heart Rate Son OR (95%-CI) | Medium Heart Rate Son OR (95%-CI) | High Heart Rate Son OR (95%-CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-violent crime | 1.369 (0.735–2.550) | 1.458 (0.804–2.643) | 1.917 (1.036–3.546) * |

| Violent crime | 3.434 (1.197–9.853) * | 2.168 (0.818–5.750) | 1.573 (0.509–4.862) |

| All crime | 1.249 (0.674–2.316) | 1.407 (0.774–2.558) | 2.201 (1.202–4.032) * |

| N | 180 | 188 | 189 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Van de Weijer, S.; De Jong, R.; Bijleveld, C.; Blokland, A.; Raine, A. The Role of Heart Rate Levels in the Intergenerational Transmission of Crime. Societies 2017, 7, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7030023

Van de Weijer S, De Jong R, Bijleveld C, Blokland A, Raine A. The Role of Heart Rate Levels in the Intergenerational Transmission of Crime. Societies. 2017; 7(3):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7030023

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan de Weijer, Steve, Rinke De Jong, Catrien Bijleveld, Arjan Blokland, and Adrian Raine. 2017. "The Role of Heart Rate Levels in the Intergenerational Transmission of Crime" Societies 7, no. 3: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7030023

APA StyleVan de Weijer, S., De Jong, R., Bijleveld, C., Blokland, A., & Raine, A. (2017). The Role of Heart Rate Levels in the Intergenerational Transmission of Crime. Societies, 7(3), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc7030023