1. Introduction

Social networking sites (SNS) like Facebook have experienced an enormous growth in membership numbers in the last few years. Facebook alone has about 1.189 billion active users worldwide [

1], with profiles on which people present themselves by providing details on their education, work, interests, and friends, by uploading photos and posting comments that can be viewed by family, friends, and acquaintances. Similarly, services like Google+ and the microblogging service Twitter allow people to set up their own profiles and share feelings and information with more or less tailored audiences.

In providing these features, these platforms allow people to present themselves and stay connected with their social contacts, even across long distances, time zones, and generations. In doing that they (can) satisfy a fundamental human need, the need to belong, which is a necessary precondition for well-being [

2,

3,

4]. While in the early times of Internet communities and social networking sites (SNS) a common assumption was that the new technologies will first and foremost be used to establish connections to strangers, it became apparent that SNS are predominantly used to electronically link to people one knows from offline life [

5,

6]. However, unlike real life interactions, social media communication entails the notion of context collapse in the sense that people from very different groups and contexts (e.g., friends, colleagues, family) are present in the audience [

7,

8]. Independent of the origin of the people one connects with, online networks imply an important resource—what Bourdieu [

9] refers to as social capital [

10,

11]. This refers to the fact that establishing and maintaining relationships leads to emotional, structural, and economic advantages since the people one is related to can offer various forms of support. Social networking sites are well suited to establish and maintain social capital and, for this reason, have been shown to be able to positively influence well-being [

10]. Numerous studies demonstrate a positive relation between intensity of SNS usage, perceived social capital, and well-being [

10,

12,

13]. In line with this, the loss of social capital (for example when a Facebook contact is lost by “unfriending”) is accompanied by negative feelings [

14]. Based on sociological concepts posited by Putnam [

15] and Granovetter [

16], social capital is distinguished into strong ties/bonding social capital and weak ties/bridging social capital [

11]. Strong ties such as family and close friends are assumed to predominantly provide emotional support, whereas weak ties (

i.e., colleagues and acquaintances) are suggested to provide informational support as they come from adjacent networks and therefore are able to bridge to other sources of information [

15]. Starting out from Granovetterʼs [

16] thesis that weak ties have particular strengths that make them even more important than strong ties and the assumption that social networking sites are especially well suited to cater for (but also take advantage of) weak ties [

17], current research on social capital in SNS gravitates to the opinion that weak ties are especially powerful and that bridging social capital is what makes SNS valuable.

Therefore, in sum, the current research on social capital in social networking sites is built on three presuppositions: (a) It is reasonable to distinguish in a dichotomous way between strong ties/bonding social capital and weak ties/bridging social capital; (b) strong ties provide emotional support and weak ties provide informational support; and (c) weak ties are more important in social networking sites as the technological functions make it easy to stay in touch with weak ties and to exchange information. While some of these assumptions have been qualified (for example, Williams [

11] acknowledges that bonding and bridging capital are related and that the factors empirically are oblique rather than orthogonal) or critically discussed against the background of empirical data (for example, Patulny and Svendsen [

18], who criticize the primacy of weak ties), to date none of these assumptions has been challenged sustainably. In fact, most empirical studies test questions within this theoretical framework (see, for example, Ellison

et al. [

10], who show that the intensity of Facebook use is positively associated with perceived bridging and with perceived bonding social capital but do not consider the relation of both dimensions) but scholars rarely conduct a critical test of the basic assumptions themselves. Therefore, the goal of the present study is to empirically address the presuppositions and to provide first data to foster a discussion on the basic theoretical framework. In this line, the present research explores whether the dichotomous conceptualization does justice to the nature of relationships individuals manage online, whether people perceive weak ties to predominantly provide information whereas strong ties provide emotional support and whether weak ties are perceived as relatively more important in SNS.

3. Method

3.1. Sample

Three hundred and thirty-seven participants (186 female) took part in the online survey. Fifteen cases were excluded because they either indicated they have fewer than 20 friends on Facebook (n = 11, which makes it difficult to adhere to the task of identifying three different kinds of contacts) or more than 1000 (n = 4). Moreover, we excluded one person who entered an irrational number for the distance between the own and the contact’s residence and four participants who completed the survey in less than 5 min. The final sample included N = 317 participants (179 female, 134 male; four gave no answer to the question). Their age ranged from 16 to 64 (M = 25.35, SD = 6.97). Most of them were students (71.9%), 13.2% were employed, 3.5% self-employed, 3.2% non-working, 2.8% pupils, 2.2% officials, and 3.2% indicated another occupation. The majority had at least a university entrance degree (94.95%); 35.96% even had a university degree.

With regard to their Facebook use, participants stated to spend M = 59.61 (SD = 71.54) min per day on Facebook in the last week. Moreover, the number of Facebook contacts ranged from 25 to 920 with a mean of M = 229.56 (SD = 153.29).

The survey addressed German Facebook users (as the survey was administered in German) who were recruited online via postings in several Facebook groups and online forums. At the end of the questionnaire, participants had the opportunity to take part in a raffle for one of six coupons (1 × 50€, 5 × 20€) for a large e-commerce site.

3.2. Measures

In order to identify three kinds of contacts that systematically differ with regard to tie strength, we retreated to Granovetter’s definition of tie strength: “the strength of a tie is a (probably linear) combination of the amount of time, the emotional intensity, the intimacy (mutual confiding), and the reciprocal services which characterize the tie.” [

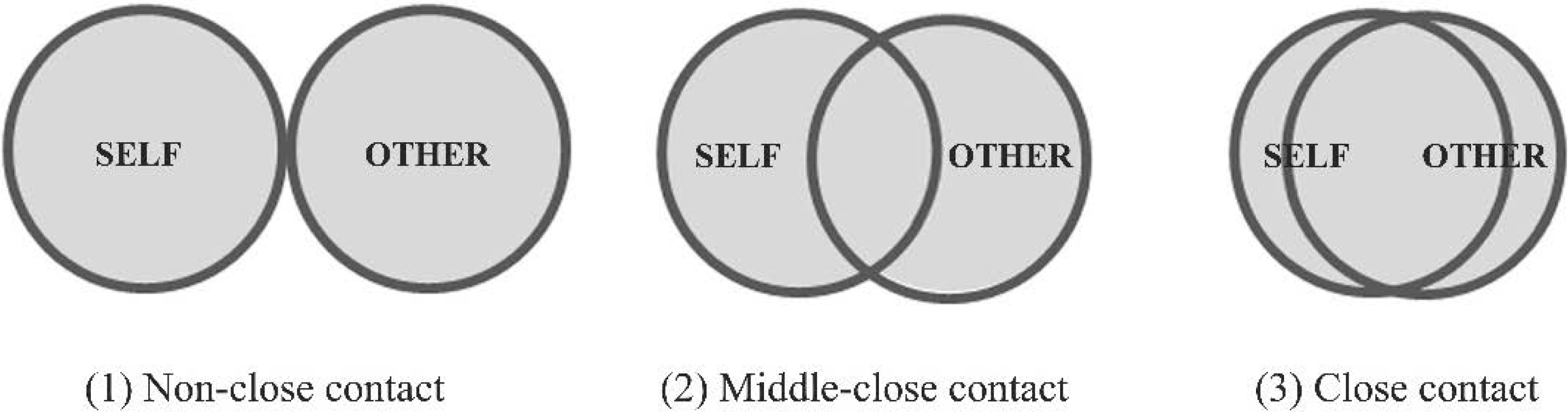

16] (p. 61). By using three illustrations, (1) no overlap of other and the self; (2) partial overlap; (3) great overlap, of the Inclusion of Other in the Self scale [

55], we asked participants for each of the three graphics to think of one of their Facebook contacts who represents the relationship presented by the graphic (see

Figure 1). The scale has been demonstrated to have convergent validity with the Relationship Closeness Inventory [

56] and the Sternberg Intimacy Scale [

57] and is therefore ideally suited to assess the dimensions mentioned by Granovetter [

16]. Recent literature demonstrates that the measure can be employed successfully to measure relationship closeness on Facebook [

44].

Figure 1.

Illustrations of relationship strength.

Figure 1.

Illustrations of relationship strength.

Additionally, in the sense of a manipulation check, we measured the following attributes for each kind of tie:

Frequency of offline contact was measured by two items (“How often do you meet this person offline (personally)?” and “How often do you talk with this person on the phone?”), rated on a 7-point scale from never to often. Due to the fact that only two items were combined, the internal consistency of the items was not very high (1st contact: Cronbachs α = 0.70; 2nd contact: α = 0.52; 3rd contact: α = 0.55).

Frequency of online contact was measured by five items (“How often do you communicate with this person online (other than via Facebook; e.g., by email or Whatsapp)?”, “How often do you visit the Facebook profile of this person?”, “How often do you read Facebook posts of this person?”, “How often do you write private messages with this person via Facebook?” and “How often do you react to Facebook posts of this person (e.g., by liking or commenting)?”), rated on a 7-point scale from never to often. The internal consistency of the items was satisfying (1st contact: α = 0.84; 2nd contact: α = 0.74; 3rd contact: α = 0.78).

Physical distance between places of residence was measured by an open question in which participants were asked to indicate the number of kilometers.

Bonding social capital/emotional support: Participants were asked to indicate on a 7-point scale, from “not at all” to “very much,” how much they agreed with the following two statements: “I trust this person to help me with my problems” and “When I have important personal decisions to make, I can ask this person for advice”. The items were based on the Internet Social Capital Scales (ISCS, Williams [

11]) and adapted to a single person. The internal consistency was satisfying (1st contact: α = 0.85; 2nd contact: α = 0.87; 3rd contact: α = 0.88).

Bridging social capital/informational support: Participants were asked to indicate on a 7-point scale, from “not at all” to “very much,” how much they agreed with the following two statements: “The interaction with this person makes me interested in what people think who are different from me” and “The interaction with this person motivates me to try new things”. The items were based on the Internet Social Capital Scales (ISCS, Williams [

11]) and adapted to a single person. As the items measure the outcome of bridging social capital, the scale was named bridging social capital/informational support. The internal consistency was satisfying (1st contact: α = 0.81; 2nd contact: α = 0.75; 3rd contact: α = 0.71).

Investment: In order to measure the importance and perceived value of the contact, participants were asked: If Facebook establishes a fee of 1€ for each person in the contact list, how likely would you pay this 1€ for this person to remain in your contact list? Answers were given on a 7-point scale from very unlikely to very likely.

Similarly, in order to assess the willingness to support the different contacts, participants were asked the following lottery question: “Imagine you had won 100€ in a Facebook lottery, which you had to allocate among your Facebook contacts. How much of the 100€ would you give to this person?”. Answers were given in absolute numbers.

After this first block of questions regarding individual Facebook contacts with different relationship strengths, we asked several questions about the whole social network on Facebook.

Social Support: Participants were asked to assess their Facebook contacts with regard to different social support dimensions and to indicate for each of the following cases how many contacts in their Facebook list they think would give them the specific kind of support. Specifically, we asked “How many of your Facebook contacts provide you with information which could be important and interesting for you (e.g., recommendations for restaurants, hints for job offers)?” (for informational support), “How many of your Facebook contacts would you expect to give emotional support when you feel bad (e.g., in terms of care or comfort)?” (for emotional support), “From how many of your Facebook contacts would you expect to receive concrete material (e.g., lending of technical devices) or non-material help (e.g., helpers for moving)?” (for instrumental support), and “From how many of your Facebook contacts can you expect personal feedback (e.g., in terms of appreciation or criticism)?” (for appraisal support).

Deleting Facebook contacts: Moreover, we asked participants to indicate how many of their contacts they could imagine deleting against the background of the preceding observation (M = 69.47, SD = 82.63) and how many Facebook contacts they had deleted before (M = 27.44, SD = 59.09).

Investment: We assessed how many of their Facebook contacts participants would keep in their Facebook contact list, if Facebook establishes a fee of 1€ for each person in the contact list.

Bonding and bridging social capital: We used the bonding subscale of the Internet Social Capital Scale (ISCS, Williams [

11]) to measure bonding social capital. The internal consistency of the 10 items was high (α = 0.85, M = 4.4, SD = 1.18). Furthermore, bridging social capital was assessed with the corresponding 10-item subscale (α = 0.86, M = 4.04, SD = 1.12).

We assessed several further variables that were used as control and moderating variables. Demographic information such as gender, age, level of education, occupation, and migration background was measured. Additionally, we assessed the number of contacts on Facebook as well as time spent on Facebook (min per day during the last week). Further, we measured the participants’ need to belong by a newly developed 10-item scale [

4]. Internal consistency of the items was satisfying (α = 0.72, M = 3.49, SD = 0.58).

4. Results

Manipulation check: As a manipulation check, we calculated whether the frequency of offline and online contact is higher for persons with whom participants have stronger relationships than for persons with whom they have weaker relationships.

Repeated measures analyses of variance revealed a significant effect of the within-factor relationship strength on frequency of offline contact (

F (1.66,524.84) = 944.38,

p < 0.001, ƞ

p2 = 0.75) as well as on the frequency of online contact (

F (1.78,561.91) = 938.41,

p < 0.001, ƞ

p2 = 0.67) (Greenhouse Geisser corrected as Mauchly test was significant). Participants indicated highest frequency of offline (M = 5.34, SD = 1.46) as well as online (M = 5.04, SD = 1.36) contact with strong ties and lowest frequency of offline (M = 1.7, SD = 0.94) as well as online (M = 2.4, SD = 1.11) contact with weak ties; contact frequency for ties of moderate relationship strength was on a medium level for offline contact (M = 3.24, SD = 1.21) as well as online contact (M = 3.86, SD = 1.13) and significantly lower than contact frequency with strong ties as well as significantly higher than contact frequency with weak ties. Therefore, in line with Granovetterʼs [

16] definition of tie strength, people spend more time with strong than with weak ties both online and offline.

As additional information, in order to be able to interpret the results, we analyzed whether people live closer to their strong ties than to weaker ties. Here, a repeated measures analysis of variance with the within-factor relationship strength and the dependent variable distance revealed a significant effect (F (1.84,573.68) = 7.08, p = 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.22). Strong ties (M = 204.89, SD = 1091.31) and ties of moderate relationship strength (M = 298.02, SD = 1453.25) lived significantly closer to participants than weak ties (M = 565.42, SD =1876.79). The difference between strong ties and ties of moderate relationship strength was not significant.

4.1. Addressing Single Ties: Relation and Relative Importance of Weak and Strong Ties in Social Networking Sites

H1

Bridging social capital/informational support and bonding social capital/emotional support correlate when assessed for three different types of contact.

We were interested to see whether the assessment of bonding and bridging social capital would vary independently of each other or whether they would correlate. Supporting H1, correlation analyses revealed high correlations between perceived bonding and bridging social capital of weak ties (r = 0.67, p < 0.001), ties of moderate relationship strength (r = 0.49, p < 0.001), and strong ties (r = 0.42, p < 0.001). Moreover, perceived bonding and bridging social capital of all Facebook contacts were similarly well correlated (r = 0.29, p < 0.001).

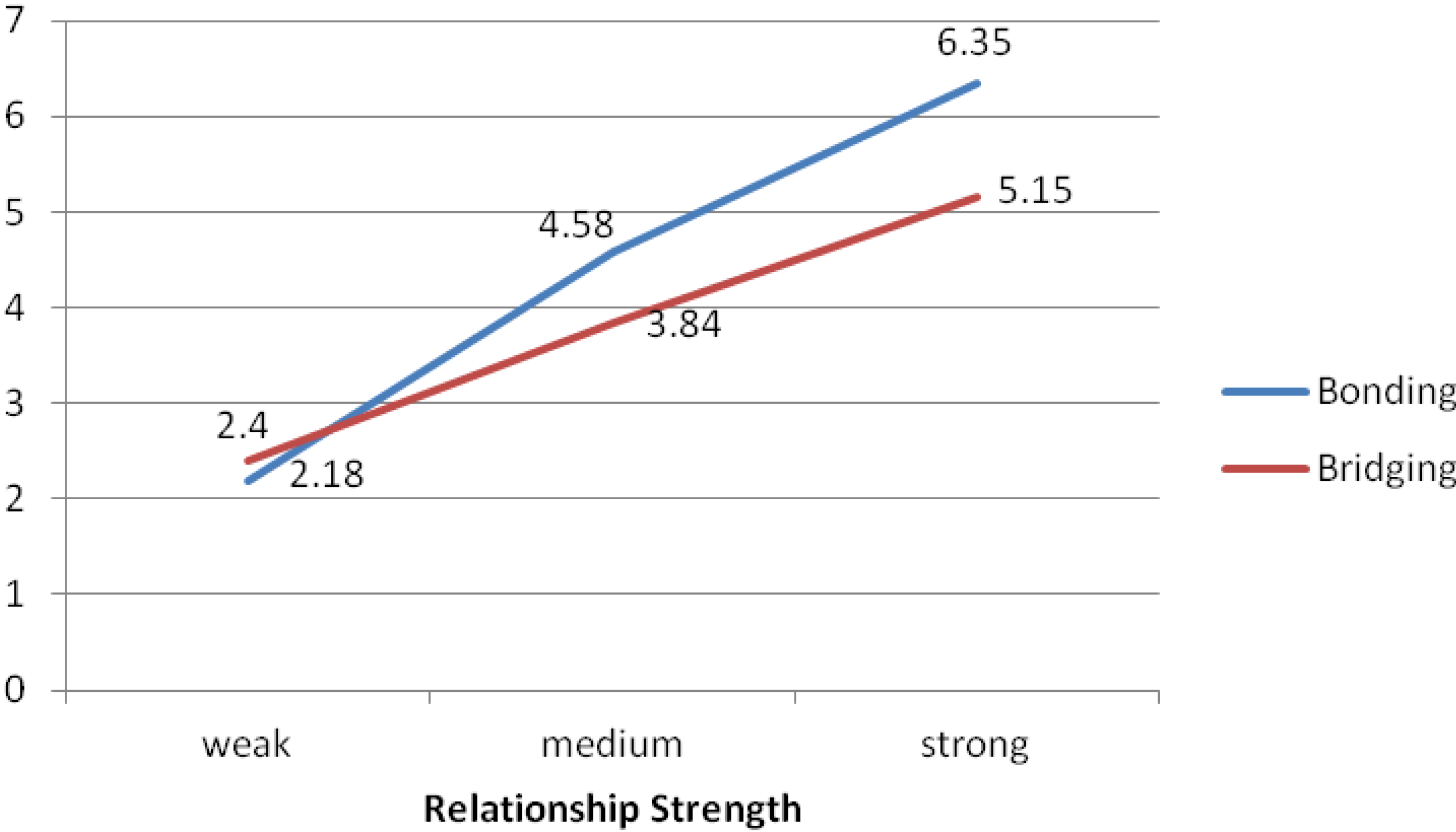

When inspecting the means in

Figure 2, it can be seen that the high correlation for weak ties is due to the fact that both bridging and bonding social capital is perceived to be low, whereas strong ties are evaluated as providing high bonding AND bridging qualities.

Figure 2.

Bonding and bridging social capital for strong, medium, and weak ties.

Figure 2.

Bonding and bridging social capital for strong, medium, and weak ties.

H2

Participants perceive higher bonding social capital/emotional support for persons with whom they have stronger relationships than for persons with whom they have weaker relationships.

A repeated measures analysis of variance revealed a significant effect of the within-factor relationship strength on perceived bonding social capital (F (2,632) = 844.23, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.73). Perceived bonding was highest for strong ties (M = 6.35, SD = 1.14), significantly lower for ties of moderate relationship strength (M = 4.58, SD = 1.66), and lowest (again significantly lower) for weak ties (M = 2.18, SD = 1.52). Therefore, H2 is supported.

H3

Participants perceive higher bridging social capital/informational support for persons with whom they have weaker relationships than for persons with whom they have stronger relationships.

In order to test H3, a repeated measures analysis of variance with the within-factor relationship strength and the dependent variable bridging social capital was conducted. Results revealed a significant effect of relationship strength on perceived bridging social capital (F (1.83,578.60) = 404.35, p < 0.001, ƞp² = 0.56). Perceived bridging was highest for strong ties (M = 5.15, SD = 1.53), significantly lower for ties of moderate relationship strength (M = 3.84, SD = 1.5), and lowest (again significantly lower) for weak ties (M = 2.4, SD = 1.46). Therefore, H3 is not supported, but results, on the contrary, indicate that stronger relationships are perceived to provide higher bridging qualities.

H4

Participants allocate greater amounts of a cash prize to persons with whom they have stronger relationships than to persons with whom they have weaker relationships.

A repeated measures analysis of variance revealed a significant effect of relationship strength on the amount of contribution (F (1.31,411.91) = 369.02, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.54). Highest amounts of money would be given to strong ties (M = 40.48, SD = 30.04), significantly lower amounts would be given to ties of moderate relationship strength (M = 13.94, SD = 16.41), and lowest amounts (again significantly lower) would be given to weak ties (M = 4.11, SD = 11.29). Thus, H4 is supported.

H5

Participants are willing to invest more in persons with whom they have stronger relationships than in persons with whom they have weaker relationships.

A repeated measures analysis of variance revealed a significant effect of relationship strength on investment likelihood (F (1.65,520.47) = 361.28, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = 0.53). Investment was highest for strong ties (M = 5.3, SD = 2.4), significantly lower for ties of moderate relationship strength (M = 4.25, SD = 2.23), and lowest (again significantly lower) for weak ties (M = 2.0, SD = 1.72). Thus, H5 is supported.

4.2. Addressing the Whole Network: Predicting Perceived Bonding and Bridging Social Capital

When assessing the perceived quality of not only selected specific contacts but for the social network in general, we asked participants to indicate the number of contacts that provide informational support, emotional support, and instrumental support, as well as appraisal support. Descriptive values (see

Table 1) suggest that most contacts are perceived to provide appraisal support (

i.e., give feedback), followed by instrumental support (e.g., lending of technical devices) and informational support (e.g., recommendations for restaurants, job offers). The lowest number of contacts was perceived to provide emotional support (only 16 out of 230 contacts on average). Additionally, it can be seen that a rather large number of contacts (roughly one third of actual contacts) is perceived as deletable and that, in fact, a considerable number have already been deleted.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among the measures addressing individuals’ whole social network.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among the measures addressing individuals’ whole social network.

| Measure | N | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|

| 1. Number of Facebook contacts | 317 | 229.56 | 153.29 | - | | | | | | | | | |

| 2. Number of contacts that provide informational support | 317 | 22.03 | 29.07 | 0.31 ** | - | | | | | | | | |

| 3. Number of contacts that provide emotional support | 317 | 16.08 | 16.47 | 0.32 ** | 0.40 ** | - | | | | | | | |

| 4. Number of contacts that provide instrumental support | 317 | 24.04 | 27.36 | 0.32 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.37 ** | - | | | | | | |

| 5. Number of contacts that provide appraisal support | 316 | 29.97 | 40.12 | 0.37 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.60 ** | - | | | | | |

| 6. Number of contacts that could be deleted | 316 | 69.47 | 82.63 | 0.55 ** | 0.14 * | 0.16 ** | 0.05 | 0.15 ** | - | | | | |

| 7. Number of contacts that have already been deleted | 316 | 27.44 | 59.09 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.12 * | 0.18 ** | - | | | |

| 8. Need to Belong | 317 | 3.49 | 0.58 | 0.25 ** | 0.13 * | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.15 ** | −0.02 | - | | |

| 9. Perceived bonding social capital | 317 | 4.40 | 1.18 | 0.07 | 0.19 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.19 ** | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.16 ** | - | |

| 10. Perceived bridging social capital | 317 | 4.04 | 1.12 | 0.18 ** | 0.12 * | 0.22 ** | 0.08 | 0.15 * | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.23 ** | 0.29 ** | - |

In order to examine what predicts the perceived quality bonding social capital (H6) and bridging social capital (H7), hierarchical regression analyses were conducted for these two criterion variables. In steps 1–3 we entered sociodemographic and personality variables in order to control for individual differences, while in the fourth step we entered the number of contacts who are perceived to provide the various forms of social support. Altogether, predictors in the analyses were (1) age and gender (dummy-coded); (2) number of Facebook contacts; (3) participantsʼ individual need to belong; and (4) number of contacts providing informational, emotional, instrumental, and appraisal social support.

The first regression for the criterion of bonding social capital revealed significant effects of gender and the number of contacts providing emotional support (see

Table 2). Females perceived higher levels of bonding social capital. Also, this means that a greater number of Facebook contacts who can provide emotional support led to stronger perceived bonding social capital.

The second regression analysis for the criterion of bridging social capital revealed significant effects of the number of Facebook contacts, need to belong, and the number of contacts providing emotional support (see

Table 2). Results showed that having more Facebook contacts in general, a higher need to belong, and a greater number of Facebook contacts who can provide emotional support led to stronger perceived bridging social capital. This shows that bridging social capital is—just like bonding social capital—affected by the number of ties that can support individuals emotionally.

Table 2.

Hierarchical regression analyses: effects of age, gender, number of Facebook contacts, need to belong, and number of contacts providing informational, emotional, instrumental, and appraisal social support.

Table 2.

Hierarchical regression analyses: effects of age, gender, number of Facebook contacts, need to belong, and number of contacts providing informational, emotional, instrumental, and appraisal social support.

| Predictor | Bonding Social Capital | Bridging Social Capital | Number of Contacts That Could Be Deleted |

|---|

| R2 | β | p | R2 | β | p | R2 | β | p |

|---|

| Step 1 | 0.029 | | | 0.003 | | | 0.010 | | |

| Age | | −0.068 | 0.227 | | −0.001 | 0.987 | | −0.099 | 0.083 |

| Gender | | 0.155 | 0.006 | | 0.051 | 0.374 | | −0.018 | 0.745 |

| Step 2 | 0.033 | | | 0.036 | | | 0.299 | | |

| Number of Facebook contacts | | 0.066 | 0.251 | | 0.189 | 0.001 | | 0.552 | <0.001 |

| Step 3 | 0.043 | | | 0.074 | | | 0.299 | | |

| Need to belong | | 0.108 | 0.074 | | 0.211 | <0.001 | | 0.009 | 0.864 |

| Step 4 | 0.125 | | | 0.107 | | | 0.317 | | |

| Number of contacts providing informational support | | 0.063 | 0.301 | | −0.017 | 0.786 | | −0.003 | 0.956 |

| Number of contacts providing emotional support | | 0.179 | 0.005 | | 0.172 | 0.008 | | 0.022 | 0.695 |

| Number of contacts providing instrumental support | | 0.050 | 0.474 | | −0.068 | 0.333 | | −0.162 | 0.009 |

| Number of contacts providing appraisal support | | 0.130 | 0.067 | | 0.095 | 0.181 | | 0.028 | 0.652 |

A regression analysis for the criterion of number of contacts that could be deleted revealed a significant effect of the number of Facebook contacts as well as the number of contacts providing instrumental support (see

Table 2). This shows that having more Facebook contacts positively affected the number of contacts that one could imagine deleting from the contact list. However, a higher number of contacts who can provide instrumental support led to a smaller number of contacts that one could imagine deleting.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The goal of the present study was to provide first data which can be used to critically reflect on several of the basic assumptions researchers in current analyses of social capital in social networking sites rely on. Therefore, we addressed whether (a) the dichotomous conceptualization does justice to the nature of relationships individuals manage online; (b) whether the two types of social capital are exclusively related to the kind of social benefits they are widely supposed to have; and (c) whether weak ties are perceived as relatively more important in SNS. By employing another kind of measurement approach in which users were asked to rate the value and ascribe social benefits (in the sense of types of perceived support) for specific examples of three different types of contacts, we tried to disentangle contact type and function. We thereby analyzed the field from a different perspective with a view to extending and challenging previous assumptions. We do not suggest that previous research did not give valid results on the nature of social capital in SNS, but we aimed to test whether social capital patterns and experiences would come out differently when looking at the phenomenon from a different angle and when thinking outside the given theoretical box.

First, we wanted to discuss whether the dichotomous conceptualization does justice to the nature of relationships individuals manage online. Here, the most important indication in our data is the fact that in the perception of the users, bridging and bonding capital is highly correlated. For all three examples of contact types (weak, middle, and strong ties) we found a high correlation, the relation being strongest for weak ties (which are evaluated to provide neither informational/bridging capital nor emotional/bonding capital). Therefore, in the perception of the users, bridging and bonding capital seems to be the same, or at least both types of support seem to go together in the sense that those who are perceived to provide emotional support are also perceived to provide informational support and those who do not provide one kind also do not provide the other. That this relation—to that extent—has not been reported in earlier studies is probably due to the way we measured the ascription of functions to the type of contact by distinguishing between three types of contacts (with participants having specific persons of that corresponding category in mind). Previous research looked at the overall bridging and bonding potential of the whole network instead of single contacts, and/or analyzed the effects of intensity of SNS usage on either perceived bridging or bonding social capital without addressing the relation of the latter (see, for example, [

10]). And indeed, when we looked at the overall correlation of bridging and bonding capital in our sample we observed lower correlations compared to the correlations for the specific ties. Still, we do not mean to call into question these previous studies and their results as they certainly have merit for the research realm but we think that our results at least give reason to critically reflect on whether a user-centered approach should continue to assume that people perceive bridging and bonding social capital differently. Also, we suggest that this finding might not only hold true for this kind of computer-mediated environment but might also apply for offline contacts. It is, however, particularly relevant for social networking sites as in this realm the distinction of bridging and bonding social capital and the primacy of weak ties has recently been stressed.

Second, we aimed to call into question whether users perceive weak ties as predominantly providing information whereas strong ties first and foremost provide emotional support. The results of H2 confirm the current belief that strong ties especially lend emotional support (see [

15]). However, when we tested the assumption that weak ties first and foremost provide informational support, the data did not confirm this assumption. On the contrary, users perceive their strong ties to not only lend emotional but also informational support, whereas weak ties were perceived to not lend any kind of support.

This can also be derived from the regression analyses which look at the predictors of perceived bonding and bridging social capital. While—as can be expected—the overall perception of bonding social capital is best predicted by the number of contacts providing emotional support, the overall perception of bridging social capital is not predicted by number of contacts that are perceived to provide informational support, as theory would suggest. Instead, the strongest predictor is peopleʼs individual need to belong, in that people who have a high need to belong perceive their contacts to provide the most bridging qualities. This is in line with earlier research that showed that, for people with a higher need to belong, it is more important to establish and cater for multiple contacts on SNS [

4]. Furthermore, the number of Facebook contacts in general as well as the number of contacts providing emotional support predicts the perception of bridging social capital. Here, the fact that the more contacts a person has, the more bridging capital he/she perceives is perfectly in line with the general assumption that SNS are prone to providing bridging social capital, as it is easy to cater for multiple, heterogeneous contacts [

17]. At first glance, this might be taken as an indication that, objectively and as stated in the literature, people with larger networks indeed have informational benefits. However, the fact that the number of contacts providing emotional but not informational support predicts the perception of bridging social capital hints at the fact that users do not—or at least do not consciously—assume that contacts providing information will contribute to the overall perceived quality of bridging social capital. Instead, here also, contacts providing emotional support are perceived as more crucial.

This suggests that close contacts are seen to be able to provide relevant, new information in online settings. The assumption that strong ties in face-to-face conversations will not yield new information might still hold true—due to the fact that (a) the background knowledge is homogeneous [

11] and (b) face-to-face conversations might lead to the phenomenon Stasser and Titus [

58] described as the failure to pool information because of the tendency to merely discuss what everyone already knows. However, in Facebook this might be different because the environment is set to constantly receive and disseminate new information—which is in most cases is not sent to all contacts but most probably only to closer friends. We would like to stress here that the two items we selected to measure informational/bridging and emotional/bonding capital for each kind of tie were chosen in order to represent the heart of the idea of emotional

versus informational support. For informational support we, however, retreated to the notion of getting interested in new things and thoughts instead of, for example, job offers, as the latter might not have been relevant for the specific sample we expected to reach.

Our results do not necessarily suggest that weak ties do not actually provide valuable information. The basic sociological assumption that weak ties are superior in information dissemination, also suggested by objective analyses, may still hold which show [

42]. Our results, however, demonstrate that although weak ties might be important and necessary for providing information, users do not perceive their networks in that way—at least not as measured for a single weak tie. Instead they experience that strong ties provide them with valuable information. This might simply be due to the wish for consistency (people who are liked and valued are also seen as important information providers) or can result from the fact that information given by strong ties is actually more valuable from a subjective point of view since close friends and family simply know better than acquaintances what movies one would like, which food one would appreciate, and which job or internship would fit.

We also have to acknowledge that the results might be artifacts produced by our measurement approach: In order to have participants think of specific people of specific contact types (weak, middle, and strong ties) we used three pictures of the Inclusion of Other in the Self scale [

55]. Here, it might be problematic that the figure that should prompt weak ties may have depicted a relationship that was too loose (in the sense that participants thought of strangers who merely accidentally became part of their friend list). This could explain why users would not perceive them as providers of relevant information. However, according to the theory then at least the middle figure (partly overlapping circles) should have been perceived as a more valuable information provider compared to the strong tie—which was not the case.

Third, we wanted to challenge the assumption that weak ties are perceived as relatively more important in SNS. The results for H4 and H5 strongly suggest that when asked directly, users evaluate their strong ties on Facebook to be more important than the weaker ones. Closer ties will be treated more favorably and one is more willing to invest in close ties by potentially paying fees to maintain the contact on Facebook.

While this (given the way the questions were posed) is probably not very surprising, there are other indications that users would not value a social networking site that would consist of rather weak instead of strong ties. Users seem to be ready to delete on average one third of their SNS contacts—given the results above, this will probably not be recruited from strong ties but from weak ties. This is confirmed when looking at the regression analysis predicting the number of contacts that can be deleted. Here, the analysis shows that the more contacts people have, the more they are willing to delete some. While this is not surprising, as this can emerge as a significant predictor even when all people indicate an equal share of their contacts as deletable, it is more astonishing that neither emotional nor informational (nor appraisal) support determines the number of persons to delete. Here, it is only instrumental support that keeps users from deleting contacts. Hence, when someone expects his/her contacts to potentially provide instrumental support (

i.e., lending something or helping with moving apartments), he/she will be less willing to delete them. This points to the importance of extending the theoretical framework to forms of social support that go beyond emotional and informational support [

37,

38].

With regard to the question of which kind of support is perceived to be predominant in SNS, an analysis of the descriptive data on number of contacts that provide different types of support seems to be beneficial. In line with the nature of social networking sites, the largest number of contacts is perceived to provide appraisal support (i.e., give feedback). The next largest number is contacts that provide instrumental support, followed by informational support. While this does not directly tell us anything about the perceived importance of informational support, it shows that only a small group of people (22 out of 230) are perceived to provide informational support. Here, the question can be raised whether we succeeded in operationalizing informational support in such a way that participants would understand the concept in the same way it has been put forward by scholars. However, as the examples given in our questionnaire mirror what is assumed about bridging social capital (namely that this means to receive information on diverse fields and to be pointed to things one did not know), we do not think that the results are due to a different understanding between scholars and participants about what informational support entails. Therefore, it might be concluded that users actually have the opinion that only a small percentage of their network provides them with valuable information.

But why would users not value weak ties in the way suggested in recent research? Possibly users simply do not recognize or remember the beneficial information they receive from weak ties. Another reason, however, might be that due to increasing information overload on Facebook more and more people decide to block or ignore information from more distant contacts. Here, also, the specific Facebook algorithms that probably result in the fact that we receive more information from closer contacts than from weaker contacts might be causative. Summing up the results and discussion, we can conclude that, contrary to current assumptions, users perceive strong ties as more important as weak ties and ascribe both emotional and informational support more to strong than to weak ties. Interestingly, these results cannot only be derived from the results stemming from the new measurement approach we employed, but were also supported in the second part of our analyses, in which we more conventionally retreated to common measures for the whole network.

In sum, our approach and results have theoretical, methodological, and applied implications. With regard to theory, social capital research has to be expanded to consider peopleʼs subjective perceptions in greater detail as they do not necessarily match objective measures. With regard to methodology, it is therefore necessary to revisit the way the outcome of social capital is measured. First of all, during our study, the fact that the widely used scale by Williams [

11] assesses the perception of the quality of emotional

versus informational support but not bridging and bonding social capital in the sense of a potential independent variable became very salient. This is something that Williams himself neatly discusses in the original article but that seems to have been blurred in further usage. If our results—that it is necessary to be more careful about the equalization of weak ties/bridging social capital/informational support and strong ties/bonding social capital/emotional support—are to be taken seriously, the terminology of bridging and bonding social capital should maybe be avoided as it links weak ties and informational support as well as strong ties and emotional support. Moreover, there might be additional problems with the common measurement approach: The scale itself has recently been criticized [

59], but primarily with regard to other aspects than the ones mentioned here. Additionally, our results show that the measurement approach must go beyond informational and emotional support and should at least include further types of social support such as instrumental and appraisal support [

37,

38] (which both appear to be even more important and salient in social networking sites than informational and emotional support).

With regard to applied implications, it might be helpful to keep in mind and observe whether Facebook algorithms, which probably further foster the importance and salience of strong ties, contribute to decreasing the potential power of weak ties.

In terms of general limitations (besides the more specific limitations mentioned above) we have to acknowledge that this research should be replicated in other cultures. Although it is not highly likely, the fact that the sample is German might have influenced the results, as there are a few studies which indicate cultural differences with regard to usage patterns of social networking sites [

60]. Germans, for example, differ from American social networking sites’ users in the sense that Germans tend to disclose less [

61]. Also, comparisons between individualistic and collectivistic cultures might be especially informative with regard to the primacy of weak

versus strong ties. It might also be important to consider other SNS than Facebook. Given the fact that all SNS (see, for example, Google+) share similar basic features, we would assume our results are generalizable to other SNS. However, this might already be different for business networks such as LinkedIn, so that the study would need to be replicated in this realm. Also, additional aspects of the users should be considered (see, for example, Ellison

et al. [

32], who advocate taking Internet skills into account). Furthermore, as we acknowledged that the functions of weak and strong ties may be existing as theoretically assumed but might just not be perceived that way by users, future research should combine objective, big data analyses of the networks with surveys such as ours. Here, analyses as presented by Park, Lee, and Kim [

62] might be a good starting point.

In conclusion, we hope to have raised some important questions that might be addressed further in future research. The fact that we found indications that some of the basic assumptions of social capital research in social networking sites should be critically reconsidered should not lead to questioning the merit of previous research but instead should prompt new directions of research and extend current theoretical frameworks. In sum, we would derive from our data that—in the perception of the users—bridging and bonding social capital might not be as distinct as commonly assumed, that the relationship between type of contact and ascribed social support function is not seen by users, and that users appreciate their strong ties on Facebook more than their weak ties.