Abstract

In a series of momentary encounters with the surface details of The Lowry Centre, a cultural venue located in Salford, Greater Manchester, UK, this article considers the fate of the image evoked by the centre’s production and staging of cultural experience. Benjamin’s notion of ‘aura’ as inimical to transformations of art and cultural spectatorship is explored, alongside its fatal incarnation in Baudrillard’s concept of ‘simulation’. L.S. Lowry, I argue, occupies the space as a medium: both as a central figure of transmission of the centre’s narrative of inclusivity through cultural regeneration, and as one who communes with phantoms: remainders of the working-class life and culture that once occupied this locale. Through an exploration of various installations there in his name, Lowry is configured as a ‘destructive character’, who, by making possible an alternative route through its spaces, refuses to allow The Lowry Centre to insulate itself from its locale and the debt it owes to its past.

I have been called a painter of Manchester workpeople. But my figures are not exactly that. They are ghostly figures, which tenant these courts and lane-ways and which seem to me so beautiful.L.S. Lowry (1975)

The ghost is not simply a dead or missing person, but a social figure, and investigating it can lead to the dense site where history and subjectivity make social life. The ghost or the apparition is one form by which something is lost, or barely visible, or seemingly not there to our supposedly well-trained eyes, makes itself known or apparent to us in its own way, of course. The way of the ghost is haunting, and haunting is a very particular way of knowing what has happened or is happening. Being haunted draws us affectively, sometimes against our will and always a bit magically, into the structure of feeling of a reality we come to experience, not as cold knowledge, but as a transformative recognition.Avery Gordon (1997)

Manchester was the scene of Lowry’s loneliness. It gave a guise of locality to the phantoms that passed before his eyes. It imbibed him with the particular melancholy that blows in off the Pennines.Howard Jacobson (2007)

1. Introduction: Cities and Phantoms

In the winter of 1926, Walter Benjamin, German-Jewish cultural commentator and literary critic, visited Moscow and was heartened at the sight of children and workers inhabiting galleries and museums with a new-found confidence, instead of the guilt-ridden look of the thief so familiar to the German proletariat in similar cultural venues [1]. What is central to what follows is this observation of Benjamin’s that space has the potential for transformation depending on how it is inhabited.

The modern city as phantasmagoric, as imbued with the ghostly shimmer emanating from the world of commodities, is a concept Benjamin takes from Marx in his exploration of the ‘dreamhouses’ of nineteenth-century capitalism: arcades, railway stations, winter gardens [2]1. Benjamin writes: “The world dominated by its phantasmagorias…is ‘modernity’” ([2], p. 26). As Hetherington reminds us, the ghost is a figural revelation eschewing the route of rational discourse. It speaks not in words but images ([4], p. 65). Such an understanding, as with Benjamin’s work, is also to privilege the minor within the everyday, or rather the everyday’s ability to provoke an unexpected reconfiguration beyond empirical fact: to prompt a re-ordering of vision that allows us to see differently what we already thought we knew.

This re-ordering of vision, to complicate what is before the eyes, is central to L.S. Lowry’s art. His famous cityscapes teem with figures, structures and stories, composites of the North-West of England he encountered on his daily perambulations as a rent collector in the mid-twentieth century. These ‘dreamscapes’ were his attempts to capture on canvas a life he saw ebbing away before his eyes: modern, urban, industrial working-class life and culture. An outsider, by virtue of his class position, his bachelor status and his day-job, Lowry, at the margins of this scene, became its best-known painter. But this renown came late in his life and perhaps most significantly after his death in 1976.

Thirty-seven years after his death, Lowry is once more the focus of media attention. A recent swathe of articles have been written about the artist reassessing his legacy to coincide with the 2013 major retrospective of his work at Tate Britain [5,6,7], and an exhibition of ‘unseen’ Lowry paintings at the eponymous cultural venue: The Lowry, Salford, UK (Figure 1). He is poised on a threshold, a familiar site for a rent-collector; precariously balanced, knocking on the art establishment’s door once more. But if we explore an earlier attempt at his canonization, at The Lowry, we find that L.S. Lowry is not so easily invited in. He rather inhabits the building as a medium, in both senses of the word: as an official figure through whom the centre’s story and ambitions for cultural regeneration are transmitted, and as one who communes with phantoms: a friend of ghosts, zombies and ghouls. L.S. Lowry, then, is a disruptive and destructive presence, one who allows the past to speak.

Figure 1.

The Lowry, Salford. Source: CC-BY-NC-SA by mrrobertwade.

2. Melancholy: The Modern Mood

Howard Jacobson, in the second annual Lowry lecture, describes L.S. Lowry as a lonely figure, ‘imbibed [by] the particular melancholy that blows in off the Pennines’ [8]. Manchester and its environs is the source of this mood. But this is not a mood unfamiliar to other places, other cities. Indeed, Benjamin discovers in Baudelaire’s poetry melancholy (‘spleen’) configured as the mood of urban modernity [9]. As the particular forlorn longing that accompanies the experience of the vast metropolis in all its horror and intoxication, it affected nineteenth-century Paris as much as it did twentieth-century Manchester. For Benjamin it is a mood that clings equally to other European cities under the thrall of capitalism with its constant parade of the novel and the innovative with the pall of the always-the-same. Yet it is within this maelstrom, within the social and cultural formations of everyday life, we might locate ‘chips of Messianic time’ [10]; threshold moments to different, other futures, which might still be realized. Melancholy is such a threshold state, for Benjamin, one that might propel those in its sway to transformative encounters: with prostitutes; collar studs; snow globes; Charlie Chaplin films; Mickey Mouse cartoons and other ‘heroes’ and ephemera of quotidian city living. Fleeting, fragmentary experiences, throwaway, disposable knick-knacks; all the more prized because of their fragility and the inevitability of their passing. For French sociologist and professional ‘Cassandra’ Jean Baudrillard, melancholy is a dead-end street. Modernity, for him, ‘ends with a yawn’. The novelty wears off. Consumption becomes the organising principle of social life, a life that is thoroughly aestheticised in the hermetically sealed coffin of the ‘hyperreal’ [11]. Cultural spectatorship becomes a Disneyland processing of bodies through space; pop culture is infantile and infantilizing, we are trapped in safety reins. When Andy Warhol first forces paint through a stencil his screen prints of food items and popular celebrities function as a critical commentary on post-war Western consumer capitalism. When Warhol is producing the same prints thirty years later, the repetition of the same joke short-circuits any critical potential: bad copies of bad copies on a never-ending loop. The conspiracy of art is complete [12]. Popular culture offers no transformative moment: it cannot be paused or interrupted from within. For Baudrillard, Benjamin’s fragile faith in the messianic potential of the everyday peters out, hastened by the image technologies of late capitalism. And thus, for Baudrillard, we are left instead with melancholy not as catalyst to other states but as ironic fascination; an orientation to the present best captured in his 1980s travelogue America [13] where the only thing for it is to stare and sneer. The intention, at best, is disturbing the glittering empty surfaces of postmodern consumer culture whilst hoping for a symbolic ‘abreaction’ [14], an event to push the system to its limit. An event without precedent that reorders the world beyond recognition, not willed, not waited for, not expected, but nonetheless inevitable. An event such as 9/11 fits the bill [15].

In what follows I consider how cultural venues such as The Lowry, as catalysts to urban change, might facilitate or constrain the potentially transformative encounters that so fascinate Benjamin about the metropolitan scene, and so depress Baudrillard about contemporary cultural spectatorship. Melancholy, of course, is also the mood of haunting, a longing for a past that can never return, a future that might never come, and a burning dissatisfaction with the now. And ghosts, of course, are also abreactions, unseemly tellers of forgotten truths; fragile figures of disturbance and dispossession. Let’s proceed, then, to explore The Lowry with L.S. Lowry and his spectres.

3. Going to the Match, Going to The Lowry

The day is overcast and rather gloomy. I’m sure the rain isn’t far away. The winter chill is evidenced by the figures who hurry through the vast expanse of space towards the ground like arrows; bent almost double as if to ward off the wind’s icy fingers. Hats of various styles: flat caps, bowlers and trilbies, cover their heads, while scarves and gloves offer further protection and a splash of colour. In the distance, the factory chimneys belch out their plumes of smoke and the church spire towers over the rows of redbrick terraced houses. To the right is an elevated figure, a soapbox beneath his feet to raise him above the crowd that has gathered. It’s hard to say if he’s a trade unionist, a missionary or merely a programme seller. There aren’t many women, I notice. A few are dotted here and there but even they are outnumbered by the dogs; stick-like figures that appear, because of their slender shape, to mirror their master’s gait, bending into the wind. The dogs outnumber even the children. Directly ahead looms the football ground. Its rhomboid silhouette dominates the scene and its stands appear already to be brimming with spectators. At the very top of the stand, on the right hand side, it is possible to make out a row of small, bird-like figures that, after a moment, reveal themselves to be another line of spectators. Feeling brave, perhaps, sitting with legs swinging atop the highest edge of the stand, taking in, not the best view of the match, but certainly a bird’s eye view of the surrounding area. And this surrounding area is formed of the leitmotifs of mid-twentieth century, working-class, urban life, captured on canvas by its most eminent painter: L.S. Lowry. As I step away from the painting, I read the card mounted on the wall to the left: Going to the Match (1953) (Figure 2). The card further reveals that the image is a painting of football spectators making their way to a match at Burnden Park in Bolton. I shiver in sympathy with the figures in the painting, chilled to the core by the aggressive air-conditioning, aimed, one supposes, at preserving the artworks and preventing their deterioration so that future visitors, future generations even, might enjoy their nostalgic, homely, cosily-wrapped depictions of the past. But this painting, indeed, any of L.S. Lowry’s art, may never have been here at all.

Figure 2.

Going to the Match, 1953. Source: author.

The inclusion of Lowry’s art was, in fact, almost an afterthought, and certainly it was not part of Stirling and Wilford’s original sketches for the site. It was only after a feasibility study had been carried out with regard to the use of the space as a gallery and the likely audience demographic researched, that the presence of visual art was considered. Salford Art Gallery already owned the L.S. Lowry collection and so a ready-made collection was within easy reach. As Myerson remarks in Making The Lowry (2000):

Lord Cultural Resources reached the conclusion that the visual art dimension of the project needed to be reconsidered. Not only did the mainly small-scale works in the L.S. Lowry collection require an intimate sequence of custom-made galleries but there needed to be a study centre for the collection. In addition, having studied the demographics of the North-West of England, which has the highest concentration of children under 15 in the whole of Europe, Lord proposed a second gallery attraction—an interaction gallery for children and families which explored the nature of the performing and visual arts.([16], p. 26)

The desire to provide a space that was far removed from the hushed reverence of usual gallery atmosphere is evidenced. The fact that demographic research played such a large part in the actual design of the building suggests that the scheme’s success was crucial to the developers and the funders of the project and few chances were taken: this project had to appeal to as broad a cross-section of the local community as possible. Indeed, this reaching out to children was matched only by a reaching out to a broad spectrum of class groupings. This was to be a ‘dreamhouse’ for all. As local councillor, Bill Hinds, pointed out: “Art in this country has always been a class issue. I’ve always felt that ordinary working-class people, kids especially, have never really been encouraged to participate in art” ([16], p. 26). Although this early optimism remained tempered by realism regarding the likely impact on the cultural lives of visitors a centre such as The Lowry could expect. Hinds said later: “I don’t expect everyone will suddenly become an opera lover or a ballet lover or an expert on painting, but I do believe that everyone should have the opportunity to develop their minds and not feel it’s not for the likes of them but for somebody higher up the social strata” ([16], p. 29). So, who better, then, as an artist, to draw in a wide variety of class groupings than L.S. Lowry with his prosaic, provincial, middlebrow, figurative scenes that everyone can relate to?

The Lowry’s gallery spaces encourage us to enter into Lowry’s vision both thematically and chronologically. Thus, the famous cityscapes are often clustered together serving to intensify their impact and to sharpen the eye to the subjects and the spatial arrangement of Lowry’s paintings. The theme of the crowd is apparent but in particular it is the architecture of the crowd that appears to have fascinated Lowry: their clockwork precision, their strategic comings and goings, the order in the rabble, the symmetry of the everyday. Going to the Match evidences Lowry’s command of the urban crowd and its formations. Eric Newton of the Manchester Guardian noted at the time, ‘I cannot remember any picture of moving crowds more clearly stated than in Going to the Match, 1953, where two streams of spectators cross each other diagonally as though they had been drilled by a master of choreography’ ([17], p. 85). It was, as Levy notes, not individuals that caught the artist’s eye but ‘the masses of people… [the] rhythms they made against the background of streets and buildings, mills and factories’ ([18], p. 17). Lowry’s cityscapes are not merely realist scenes, however, but rather composites of the actual and the imagined. As Levy notes, Going to the Match ‘is not a picture of a particular football match but a ‘vision’ of all football matches’ ([18], p. 79).

Lowry’s envisioning, his way of looking at both the real and imagined urban crowd, relates to his experience as an outsider. He remarks ‘had I not been lonely, I should not have seen what I did’ ([17], p. 3). Lowry’s mode of looking, then, this being simultaneously in but not of the crowd, is analogous to one of Benjamin’s (and Baudelaire before him) key urban figures, the flâneur. The flâneur is part of the urban mass but moves against it in particular ways, whether by traversing or seeing it differently, from the perspective of the outsider, exile or stranger. The crowd is both disturbing and intoxicating. For Baudelaire, as Benjamin describes, it is a reservoir of electrical energy into which one dips receiving the jolt of modern urban life. Benjamin writes, “Moving through this traffic, involves the individual in a series of shocks and collisions. At dangerous intersections, nervous impulses flow through him in rapid succession, like the energy from a battery. Baudelaire speaks of a man who plunges into the crowd as into a reservoir of electrical energy” ([9], p. 328). For Benjamin, this shock-like form of modern experience (Erlebnis) as a constituent feature of the modern city where coherent experience (Erfahrung) no longer endures. For Baudrillard, the city crowds of New York are also a source of energy. Not the enervation of shock and agitation but rather of the glittering filmic surface: ‘turbulent, lively, kinetic, and cinematic, like the country itself’ ([13], p. 18). The best way to experience the American city according to Baudrillard is not on foot at all, but rather as it speeds past the eye via another the screen: the wind-shield of a car.

In many ways, the limited palette of Lowry’s city scenes are in dramatic contrast to the child-friendly, primary-coloured interiors of The Lowry centre itself. The fact that Lowry’s work was never a raison d’être for the centre is apparent in Clelland’s review of the space itself for Architecture Today, which raises the question of the success of the gallery spaces in terms of design. There is a sense in which, for him, the galleries housing of Lowry’s art appears ‘tacked-on’, almost a dirty secret clouding the bright optimism the centre wishes to project. He notes:

The work of L.S. Lowry is not pivotal to the complex. Indeed the galleries for the permanent display of his paintings are perhaps the least convincing architectural achievements; the walls appear dull beneath an overweening roof… with the Salford of Lowry long gone, his automaton figures take their place in the freer, though perhaps more sinister, world we inhabit today.([19], p. 50)

The early years of post-revolutionary Russia, at least, offered a more inspiring vision of cultural spectatorship, for Benjamin. He notes: “Nothing is more pleasantly surprising on a visit to Moscow’s museums than to see how, singly or in groups, sometimes around a guide, children and workers move easily through these rooms” ([1], p. 183). Indeed, for Benjamin, a museum or gallery that broadened its appeal was to be congratulated. Fundamental to the comfort and inclusiveness of such spaces were the kinds of displays and exhibits housed therein. Benjamin singles out the Polytechnic Museum for its “many thousands of experiments, pieces of apparatus, documents and models” ([1], p. 183) as particularly successful, as well as the Tretikov Gallery where “the proletarian finds subjects from the history of his movement” ([1], p. 183). Freed from the constraints of class-bound life the worker or child is able to educate him or herself, fostering their own appreciation of art. Even, perhaps, establishing a counter-canon, unfettered by bourgeois norms, and no longer forced to consider established “masterpieces” as such. The comrade will “rightly acknowledge[s] very different works… [those]… that relate to him, his work, and his class” ([1], p. 184).

Lowry’s paintings, with their focus on the everyday life of the working classes, at rest and play, perhaps function as this re-appropriation of art as meaningful to ordinary people that Benjamin imagined. That Lowry is popular is both his privilege and his downfall. Art critic Brian Sewell once remarked, that if the general public had their way, all galleries would house nothing but Lowry’s [20]. This was not a compliment. If the London art establishment condescended to Lowry for being too provincial, too picturesque, he was also relegated by left-wing art critics for not being political enough, since, disappointingly, his paintings did not show the workers at work2. Instead, we see their scrawny outlines escaping from the mill, the factory and the school; snatching their brief moments of leisure at the fun fair and the football match3. His vision was sociological, curatorial even, but not political. Lowry acknowledged he did not ‘care for the crowds in the way a social reformer does’ but as ‘part of a private beauty that haunted [him]’ [17]; he painted, and was moved to paint by, ghosts. And as such his paintings have an anamnestic power. There is a distance, then, between how Lowry lived and what he sees; between what he saw and what we might. He was both present and dislocated, in and out of time. Time as both the here and now—his paintings as composites of time present and past—and time as rhythm: the industrial beat to which the cityscape hummed. And that is why his paintings are not the cosy, insular, nostalgic depictions of the North we see at first glance4. Not celebrations but lamentations; of a life long gone but once lived, and of the life even before that. The fashions of the stick-like figures who populate his scenes attest to this: flat caps, bowler hats, scarves and boots evident in mid-twentieth century paintings long after such styles had waned. As Andrews notes: ‘He was once asked why all the people in the crowd scenes in his pictures, even in the 1950s, wore the old-fashioned clothes, the shawls and the caps and big boots, of a by gone age. He replied: ‘That’s because my real period was the Depression age of the twenties and thirties. My interest in people is rooted there. I like the shape of the caps. I like the working-class bowler hats, the big boots and shawls.’ But Lowry was only pleasing the questioner, not answering the question. Working-class bowler hats for any but special occasions were extinct by the 1920s. Lowry’s true period was the time before the Great War: the period of his Mill Worker, shawled and clogged, of 1912; the period of Hindle Wakes’ ([17], p. 75). In this way Lowry’s ‘dreamscapes’, by focusing on the fashions of past, on similar sights and the repetition of the familiar, were a process of preservation, of keeping alive the past even as it dwindled. A gap is established where ghosts live on.

4. The Image: From Aura to Simulation

For Benjamin, if modern urban life is about the shattering of experience as intelligible, enduring and coherent, the concomitant transformation in terms of cultural reception, however, might produce other possibilities. In the fragment Dreamkitsch (1927), which is his earliest discussion of Surrealism’s potential for the revelation of quotidian experience, Benjamin notes the spatial quality of what we traditionally understand as ‘art’, which “begins at a distance of two meters from the body” ([23], p. 4). This distance, then, is an important aspect of the ‘aura’ of the artwork and its mode of reception in the traditional gallery space, along with notions of singularity, originality and artistic genius. In this way, through ritual and tradition, (the artwork’s ‘cult value’), auratic art is complicit with bourgeois power relations and cultural values. But aura is also marked by reciprocity, between the viewer and the artwork, a seeing and being seen. Benjamin writes:

Experience of the aura thus arises from the fact that a response characteristic of human relationships is transposed to the relationship between humans and inanimate or natural objects. The person we look at, or who feels he is being looked at, looks at us in turn. To experience the aura of an object we look at means to invest it with the ability to look back at us.([9], p. 338)

On viewing Lowry’s paintings, we are embroiled in the auratic gaze, as one of modern life’s evanescence, even as we experience his art in what Benjamin would consider a post-auratic encounter—in a centre committed to accessibility, irreverence, mass spectatorship. This is as much to do with the tricky, ambiguous concept of aura itself, which, as Gilloch notes, combines both negative and positive moments; ‘on the one hand it is a form of obscurity and inscrutability’, on the other ‘of melancholy, incomparable beauty, a moment of mutual recognition’ ([24], p. 177).

Benjamin, of course, sought the ‘destructive’ potential that new ‘post-auratic’ arts, namely film and photography, heralded. Instead of transmitting cultic and ritualistic relationships to the aesthetic, film exploded the everyday in the ‘dynamite of the split second’ opening up space and time for viewers to ‘set off calmly on journeys of adventure’ ([6], p. 265). The everyday, then, carried secret cargo that might be detonated by light and heat on celluloid. Democratic potential is realized in film’s expansive dissemination, made possible through the ease of its reproducibility, ‘meeting the recipient halfway’, and in their own circumstances ([6], p. 254). Benjamin notes the shift from ‘cult value’ to ‘exhibition value’, formed out of the act of collective viewing. Art can now come to us. He notes: ‘painting, by its nature, cannot provide an object of simultaneous collective reception, as architecture has always been able to do, as the epic poem could do at one time, as film is able to do today’ ([6], p. 264). If auratic art is the ineffable distance however close we may be, post-auratic art is proximity through the technological interrogation of time and space. But this is not without risk. Aura might be re-animated even in film, through the re-touch and the cultish worship of the movie star5. Post-auratic images, for Benjamin, are always on a knife-edge between political transformation and the insulation of change. It is in this context that the contingent nature of new aesthetic forms must be understood. For Baudrillard, there is no such dilemma. It is this constant wresting away of transformative potential, conditioned by the ascendency of the replication, circulation and exhibition of images that Baudrillard takes from Benjamin and deploys in his concept of simulation, thereby demonstrating the fragility of Benjamin’s hopefulness. Such aesthetics cannot be revelatory, in the way that Benjamin imagined, for Baudrillard, since they work to produce, not critical depth or distance, but rather immersion, the abyss of surface.

At the exit to The Lowry’s gallery spaces is a fixed installation called Meet Mr Lowry. This biographical film is screened on a loop for visitors who take their seats in an open-plan space of benches. This serves to stress the casual, non-didactic, non-auratic nature of the delivery of information, and is in contrast to the more formal seating arrangement of the centre’s theatres. Lowry is shown discussing his paintings and his inspirations in a very plain, apparently non-self-reflexive way. He says, “I just paint what I see”. There is little artistic pretension; in fact, he is actively resistant to such indulgence. This is of course, in itself a construction of a particular ‘image’. Lowry was well known for misleading interviewers, the press and even his biographers. He was particularly keen that the fact of his day-job as a rent collector be concealed lest he was deemed to be a mere ‘weekend painter’ or ‘hobbyist’ [26]. Yet at other times, he actively encouraged the idea that he was merely ‘tinkering at his pictures’. Lowry’s self-commentary is playfully contradictory. At times he explicitly undermines the notion of himself as an artistic genius (‘I am not an artist, I am a man who paints’). The film, then, as well as containing Lowry’s autobiographical reflections also offers up some rather crude psychological analysis, making reference to his closeness to his mother, the fact of his never having married and the discovery of paintings after his death which evidence a libidinal quality absent from his more well-known cityscapes. However, even to construct him as not an enigmatic, inscrutable, genius or as a ‘serious’ artist, and instead as accessible and ‘ordinary’ is still absolutely to bestow ‘auratic’ reverence upon him in terms of his ‘ordinariness’ and his ‘naivety’. The footage of him talking as an elderly man ascribes Lowry with a non-threatening-naïf quality; echoing the lack of threat the building itself, which houses his work and takes his name, seeks to engender to enable its self-talk of inclusivity and accessibility for all. This is the cult of L.S. Lowry. The romantic nostalgia of Lowry as ‘everyman’ imbues the centre with a borrowed authenticity. Providing a familiarity that morally guarantees the building’s insertion into the Salford cityscape, smoothing out its rupture. We do not encounter Lowry’s subject matter here as he did: alienating and disturbing, beautiful and mournful in the same moment, but rather as comfortable, familiar, digestible; the cityscape is shorn of its critique by the cultural experience The Lowry stages.

5. The Masterplan: Zombies, Doppelgängers and Cannibals

At the entrance to The Lowry’s gallery spaces, an exhibition of 2007 staged the latest music video by the Manchester pop/rock band Oasis [27]. In The Masterplan, the band is inserted, as Lowryesque characters into an animated Lowryesque cityscape, which references various paintings including Going to the Match (1953), Man Lying on a Wall (1957) and Daisy Nook (1946) (Figure 3a,b). Oasis’s own aesthetic self-consciously trades on nostalgic depictions of Northern vernacular culture; their image, styling and sonic output infused with a veneer of romanticized hindsight, repetitiously drawing on the legacy and signifiers of ‘swinging sixties’ pop culture. Here, showcased as participants in Lowry’s paintings, aligning the band and The Lowry galleries with these signifiers of Northern working-class life and its lost, but mourned (and fictional), urban coherence. The message implies that Oasis, in their video, make the journey all spectators of Lowry’s work wish they could: they enter into the world of his paintings. And that Oasis also, by virtue of belonging to this place, fit easily and seamlessly into these scenes. For Baudrillard, this is a strategy all contemporary cultural spectatorship attempts: to align the viewer, as closely as possible, with the artwork. He writes:

All cultural spaces are involved, some new museums, following a sort of Disneyland processing, try to put people not so much in front of the painting—which is not interactive enough and even suspect as pure spectacular consumption—but into the painting. Insinuated audiovisually into the virtual reality of the Dejeuner sur l’herbe, people will enjoy it in real time, feeling and tasting the whole Impressionist context and eventually interacting with the picture.([28], p. 22)6

Figure 3.

(a) Oasis’s Going to the Match. (b) Oasis’s Man on Wall.

This is not Benjamin’s post-auratic democratisation either, but the recreation of synthetic aura, or in Baudrillard’s idiom a simulation of aura. Distance is obliterated but the experience insulates against change rather than transforms, as in the ‘re-touch’ ([30], p. 95). For Benjamin, technological reproduction must maintain the contingency of the media form rather than attempt to recreate ‘aura’ by ‘monumentalising’ the present. The staging of the Oasis video does just that. In simulating Lowry’s cityscapes, the iconography of the video plays on the image of L.S. Lowry as a signifier of working-class, Northern culture, and therefore as a short-hand for authenticity. Yet the visual signifiers in the animation are less Lowry’s critical vision than the trite song Matchstalk Men’s cosy depictions7. Oasis function not as bringers of life to Lowry’s paintings but as zombies; un-dead inhabitants, stalking unthinkingly through his industrial scenes, thus emptying out their critical power.

The notion of habitation is central to the sociological concept of haunting, as formulated most distinctly in the work of Avery Gordon in Ghostly Matters [31], but also by Jacques Derrida in Specters of Marx [32]. For Gordon, haunting offers up a ‘transformative recognition’ made possible by ghosts who are not merely dead or missing persons but ‘social figures’ that reveal to us a way of knowing thought lost or ‘barely visible’ to contemporary eyes [31]. Ghosts haunt spaces, taking possession of them in distinctly different ways to the living. Tracking such phantoms, exploring their habits, their flickering into view, points to the ephemerality of our own existence, its fragile and precious truths, the site where ‘history and subjectivity make social life’ [31]. In Lowry’s Going to the Match, scurrying spectators brim with anticipation and expectation. Its reanimation in The Masterplan, disperses his criss-cross crowd into a homogenous blue mass, clothed in the colours not of Bolton Wanderers, but of Oasis’s local team Manchester City. Here the crowd are already inside the ground, victory is already assured; there is nothing left to hope for.

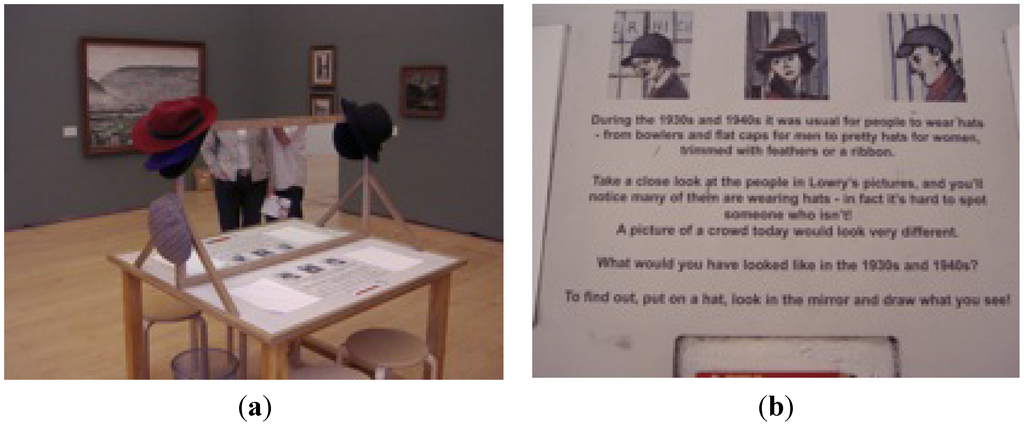

If the aesthetic flourish of The Masterplan, then, reanimates class as an aesthetic trick or third-order simulation, this is not the only version of this theme that recurs in The Lowry. In the galleries, next to the paintings of the industrial scene, is a mirrored desk (Figure 4a,b). On each of its ends hang scarves, flat-caps and bowler hats, the very costumes of the working classes depicted on the surrounding walls. Children are encouraged to sit at the desk, put on a hat and scarf and draw what they see of themselves in the mirror. A curious doubling occurs. Dopplegängers, in the guise of post-industrial children, reanimate the everyday work-wear of the industrial masses, in a spectacle of play, albeit directed play. In this encouragement of creativity there is a certain unease or discomfort, a jarring, just as the doppelgänger’s appearance is an ominous signal of impending death. The markers of class distinction, here, are reduced to a dress-up box; class is consumed and discarded as a game, configured as ‘exotic object’ of curiosity and novelty [33]. The children that visit The Lowry, of course, are freed at the end of their labour to return to their, by comparison, affluent lives. Hats and scarves are removed, drawings rolled, ready for the fridge magnet. As is usual with contemporary venues of cultural spectatorship, the gift shop is a key site in the complex, the place to stock-up on all things Lowry-themed8.

Figure 4.

(a) Mirror and ‘dress-up’ clothes. Source: author. (b) Instructions. Source: author.

For Baudrillard a successful disturbance of this form of cultural consumption would be better registered not by the apparition of children dressing-up as Lowry’s figures, but by the ‘abreaction’ of all the children falling into The Lowry’s commissioned demographic turning up at once; a living crowd of Going to the Match’s proportions. Not a haunting, then, but a ‘hyperconformist’ occupation [11]. In a rather macabre vision, at its opening event, The Lowry hired a children’s face painter. This was not to produce the usual lions, tigers and bears of the birthday party but, rather, the sallow-cheeks and dark-rimmed eyes of Lowry’s figures. The grey faces of Salford’s past returned, albeit briefly, inscribed on the faces of the post-industrial generation children in the gallery. A ghoulish enactment of aura—as a face-to-face encounter- as reciprocity, occurs, in the corporeal reenactment of Lowry’s figures on a living child. As Benjamin notes, ‘cult value does not give way without resistance. It falls back to a last entrenchment, the human countenance’ ([6], p. 257).

Such a haunting, then, draws our attention to contemporary markers of class, which cannot be so easily wiped clean. Lowry’s figures were ‘matchsticks’ because they were worn bare through work, whippet-thin through poverty and poor diet, traversing the cityscape on foot. The children who arrive at The Lowry in the family 4 × 4, solicited via the centre’s demographic study are removed from the horrors of industrial Salford The Lowry re-stages. Current bodily marks of exclusion: obesity, drug and alcohol abuse, heart-disease, are no doubt all too familiar to those occupying the Ordsall Estate, to the South East of the centre, across the dual carriageway [35]. The health priorities of the Local Authority tell us Lowry’s workers are still with us, in other guises; the dispossessed live on.

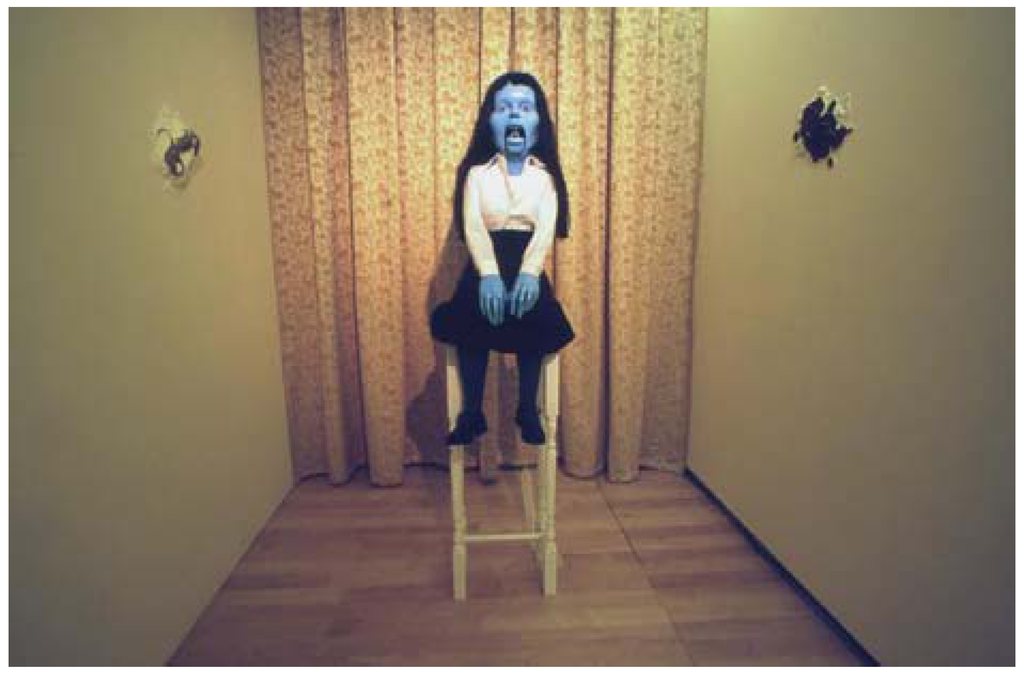

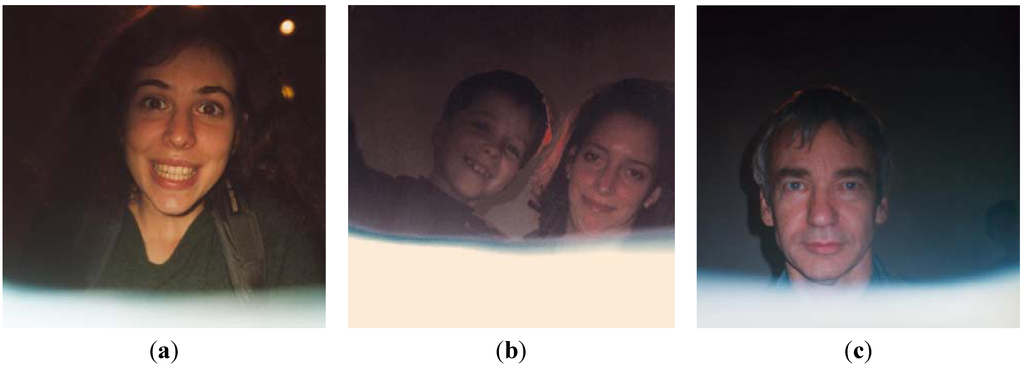

In a final momentary and unexpected encounter, as part of an early exhibition entitled The Double, The Lowry hosted Lindsay Seer’s work Candy Cannibal (2000) (Figure 5), we are confronted with the fleeting and fragile possibilities Benjamin attributed to the post-auratic and the urban scene. A ventriloquist’s dummy sits on a stool at the end of a corridor. Her mouth contains a camera. She makes no sound, speaking only in images, capturing the fascinated and thrilled expressions of spectators as they peer curiously into her face. The corridor’s walls are lined with renderings of animals eating their own kind. The camera gobbles up the faces and spits out an image. But the image produced also captures a moment of unexpected reciprocity, human emotion in freeze-frame: surprise, delight, unease, all made visible by the freakish figure of Candy Cannibal. Affective transformations made possible by collapsing the auratic and the post-auratic into each other, the face and the camera, connected (Figure 6). This phantom doesn’t speak—it tells its story through images of its audience. We do not, then, look at Candy Cannibal as art object, but at ourselves, uncannily, as subjects, in a moment of astonished remembrance and recognition.

Figure 5.

Candy Cannibal at The Lowry. Source: the artist and Matt’s Gallery, London, UK.

Figure 6.

(a) Audience Member. Source: the artist and Matt’s Gallery, London. (b) Audience Members. Source: the artist and Matt’s Gallery, London. (c) Audience Member. Source: the artist and Matt’s Gallery, London, UK.

6. Conclusion: Rent-Man, or Repo Man: Collecting What Is Owed

The Lowry stages encounters of cultural spectatorship encased within its purpose built arena for ‘art and entertainment’, as a phantasmagoria of 21st century urban dreams9. We already know Lowry didn’t belong. Even in the centre that takes his name, he almost wasn’t there. In its displays of L.S. Lowry’s work such as Going to the Match, we stand before the painting caught up in the tricky, magical transmission of aura as a ghostly encounter with the past. In Meet Mr. Lowry we view the life of the artist on film—post-auratically- yet this works not to dispel, but rather, to reverse one of Benjamin’s images, to pump aura back in, narrating Lowry’s life as a figure of naivity, an everyman and a nobody10. His critical vision, its ability to look askance at the industrial scene, is undercut, by the recuperation of him as nostalgic, charming and quaint. The same fate befalls Oasis and their re‑animation in Lowry’s ‘dreamscapes’; as a parade of zombies; simulated cutouts that do not fit. Via the dressing-up box, ghouls and doppelgängers trouble the scene of cultural consumption, pointing us to the contemporary markers of class that cannot be removed, disturbing the gallery’s surface, and directing our attention out of the centre, and into the lives of Salford’s inhabitants beyond its walls.

In a series of momentary encounters, with the surface details in The Lowry: a painting, a music video, a dressing-up box and a guest installation, I have sought to privilege the apparently insignificant or easily overlooked. In doing so, something of the staging of the centre’s cultural spectatorship is revealed. Some of these encounters are auratic, some fall into simulation, others succeed unexpectedly; a battle of wills between Benjamin and Baudrillard in constant play. In Candy Cannibal, the transformative moment shimmers into view in the split-second snap of the camera’s shutter. The present is haunted by the faces of the only very recently past. Reminding us of those who were once here, and are just as quickly gone. L.S. Lowry, then, is not smoothly inserted into this cultural space, just as this building is not smoothly inserted into Salford’s cityscape. Awkward edges poke out, like the scrawny elbows and dirty knees on Lowry’s canvasses; phantoms jostle for our attention, their presence evidencing the rupture, disturbing the shiny surfaces of cultural regeneration, as they will us to notice them. Lowry becomes Benjamin’s ‘destructive character’11 [36], his melancholic presence both haunts and revitalizes our experience of The Lowry, what it claims to repay, in his name: the debts owed to Salford’s past. The Lowry, as part of the 21st century cityscape, can still disturb and be disturbed; be alternately occupied, re-possessed.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

- 1. For an exploration of other contemporary dreamhouses of cultural regeneration see [3].

- 2. Marxist critic John Berger initially had high hopes for Lowry when he chose his work for the Looking Forward exhibitions at London’s Whitechapel Gallery in 1952, 1953 and 1956, respectively. Lowry jostled with British figurative realists, Kitchen Sink realists and Sickertian cityscapes by Ruskin Spear. Yet, as Spalding argues, ‘Berger’s initial appreciation of Lowry became more critical as his political attitudes hardened’ ([21], p. 95).

- 3. Art critic Marina Vaizey notes, in the catalogue accompanying Lowry’s memorial exhibition at London’s Lefevre Gallery shortly after the artists death: ‘It is cosy and tempting (and all too many have been tempted) to dismiss, with a note of condescension his work as being charming, naïve and quaint. For some, this may mean it is all the more acceptable. But if we look carefully at the intelligent, imaginative and continually surprising compositions, the grainy silvery radiance of his drawings, his powerful way with colour, and with texture, we can, if we have but eyes to look, how far from the picturesque his vision is. His is a tough-minded, resolute view” ([22], p. 3).

- 4. As Jacobson notes: “Not looking at what’s before our eyes we have taken Lowry’s matchstick men and matchstick cats and dogs…to be warmly appreciative, nostalgic evocations of the teeming street life of Manchester and Salford and it might be that every now and then temptation seized him to give into sentimentality of that sort…but for the most part these matchstick figures hurry off the canvas, the forward slope of their bodies suggesting not just dejection, or the bad weather…but a sort of propulsion disconnected to their wills” [8].

- 5. As Leslie notes: ‘The star cult, promoted by the capitalist entertainment industry through fan clubs and spectacles, conserves the magic and rotten shimmer of the artificially boosted commodified star personality. Its complement, the cult of the public, a corrupt concept of mass ‘Volk’ attempts to substitute for class’ ([25], p. 136).

- 6. Disneyland for Baudrillard is an important signifier of what he calls the ‘deterrence function’ of cultural spaces. For Baudrillard, Disneyland may appear to reinforce the ideologies of American values, albeit in “miniature and comic strip form” but it actually exists as a function of deterrence, as an attempt at “saving the reality principle” by “concealing the fact that the real is no longer real” The ludic, childish qualities of Disneyland exist in order to trick us into believing that ‘outside’ is adult when in fact “childishness is everywhere”. Thus Baudrillard argues, “Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real, when in fact all of Los Angeles and the America surrounding it are no longer real but of the order of the hyperreal and of simulation” ([29], p. 175).

- 7. In the general conscience of the British public the image of L.S. Lowry as cosy and nostalgic, was encouraged, one might argue, by the rather unfortunate, trite, British number one single of 1978, Matchstick Men by Brian and Michael, whose subject matter was the familiar figures in Lowry’s paintings. The lyrics attest to the ordinariness of Lowry’s imagery: “he painted Salford’s smoky tops on cardboard boxes from the shops” and “kids who had nowt on their feet”.

- 8. Esther Leslie details the version of cultural consumption described as it pertains to Tate Modern in [34].

- 9. Benjamin reminds himself in his notes for the essay on Baudelaire to consider: ‘The concept of culture as the highest development of phantasmagoria’ ([2], p. 917).

- 10. Benjamin writes Atget’s city photographs “work against the exotic, romantically sonorous names of the cities” and thereby “suck the aura out of reality like water from a sinking ship” ([36], p. 518).

- 11. Benjamin writes, “The destructive character sees nothing permanent. But for this very reason he sees ways everywhere. Where others encounter walls or mountains, there, too, he sees a way…Because he sees ways everywhere, he always stands at a crossroads. No moment can know what the next will bring. What exists he reduces to rubble-not for the sake of rubble, but for that of the way leading through it” ([35], p. 542).

References and Notes

- Benjamin, W. Moscow Diary; Eiland, H., Translator; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, W. The Arcades Project; Eiland, H.; McLaughlin, K., Translators; The Belknap Press of Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Z. Erasing the traces, tracing erasures: Cultural memory and belonging in Newcastle/Gateshead, UK. In Walter Benjamin and the Aesthetics of Change; Pusca, A., Ed.; Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington, K. Capitalism’s Eye: Cultural Spaces of the Commodity; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Winterson, J. Stick It to the Man. The Guardian. 15 June 2013. Available online: http://www.guardian.co.uk/ (accessed on 16 June 2013).

- Jury, L. Undiscovered L.S. Lowry Work Found on the Back of Painting Ahead of Tate Show. The Independent. 24 June 2013. Available online: http://www.Independent.co.uk/ (accessed on 25 June 2013).

- Darwent, C. The Matchstick Men Aren’t Quite Where Lowry Left Them. The Independent. 29 June 2013. Available online: http://www.Independent.co.uk/ (accessed on 30 June 2013).

- Jacobson, H. The Proud Provincial Loneliness of L.S. Lowry. The Guardian. 26 March 2007. Available online: http://www.guardian.co.uk/ (accessed on 13 April 2008).

- Benjamin, W. Selected Writings, Volume 4, 1938–1940; Eiland, H.; Jennings, M.W., Translators; The Belknap Press of Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, W. Illuminations; Pimlico: London, UK, 1999; p. 255. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, J. Simulacra and Simulation; Glaser, S., Translator; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, J. The Conspiracy of Art: Manifestos, Interviews, Essays; Lotringer, S., Ed.; Hodges, A., Translator; Semiotext(e): New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, J. America; Turner, C., Translator; Verso: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, J. The Uncollected Baudrillard; Genosko, G., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, J. The Spirit of Terrorism; Turner, C., Translator; Verso: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Myerson, J. Making The Lowry; The Lowry Press: Salford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, A. The Life of L.S. Lowry; Jupiter Books: London, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, M. The Paintings of L.S. Lowry: Oils and Watercolours; Jupiter Books: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Clelland, D. Harmonic Scale: Michael Wilford & Partners at The Lowry. Architecture Today 2000, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- The Lowry Website. Available online: http://www.thelowry.com/press-releases/2004/05/29/michael-parkinson-and-ian-mckellen (accessed on 25 June 2013). Sewell said: ‘the spectre of popular opinion. Lord, save us from it. If the National Gallery were in the hands of popular opinion it would be filled with the works of L S Lowry’..

- Spalding, F. British Art since 1900; Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, M. Catalogue Notes. L.S. Lowry RA 1887–1976: [Exhibition], 4 September–14 November 1976; Royal Academy of Arts: London, UK.

- Benjamin, W. Selected Writings, Volume 2, Part 1, 1927–1930; Eiland, H.; Jennings, M.W., Translators; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Gilloch, G. Walter Benjamin: Critical Constellations; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, E. Walter Benjamin: Overpowering Conformism; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde, S. A Private View of L.S. Lowry; Collins: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- The Tate. Available online: http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/lowry-and-painting-modern-life/ (accessed on 16 September 2013). Tate Britain currently has a link to The Masterplan video as part of its current Lowry retrospective.

- Baudrillard, J. Art & Artefact; Zurbrugg, N., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, J. Selected Writings; Poster, M., Ed.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2001; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Caygill, H. Walter Benjamin: The Colour of Experience; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, A. Ghostly Matters Haunting and the Sociological Imagination; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, J. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International; Kamuf, P., Translator; Routledge: New York, NY, USA/London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Highmore, B. Cityscapes: Cultural Readings in the Material and Symbolic City; Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, E. Tate Modern: A Sweet Year of Success. Radical Philosophy 2001, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Salford City Council. Available online: http://www.salford.gov.uk/ (accessed on 15 June 2013). The Ordsall Estate was deemed in 1994 to be one of the poorest, most deprived estates in the UK with unemployment, teenage pregnancy and mortality rates above the national average. The Local Authority is keen to point out how the area has benefitted generally from the development of Salford Quays, of which The Lowry is a key element. There has been a shift in the area’s ‘image’, best indicated by rising house prices and the building of flats and houses catering for young professionals. However, major inequalities still persist as detailed in the various neighbourhood documents of Salford City Council.

- Benjamin, W. Selected Writings, Volume 2, Part 2, 1931–1934; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).