1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic precipitated an unprecedented crisis in global education. Following the World Health Organization’s pandemic declaration on 11 March 2020, more than 1.6 billion learners across 190 countries were affected [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Greece implemented strict containment measures from March 2020 to May 2021, requiring immediate school closures [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Institutions faced pressure to transition entirely to online delivery with limited advance notice and varying technological readiness [

11,

12,

13,

14].

1.1. The Shift from Emergency Remote Teaching

Emergency remote teaching differed fundamentally from planned distance education. It was implemented ad hoc without adequate preparation for instructional design, technology infrastructure, or staff training [

15,

16,

17]. Unlike established distance programs, emergency remote teaching was characterized by urgency and uneven resource distribution [

18,

19,

20]. The transition occurred alongside broader societal stressors: health concerns, economic instability, and social isolation [

21,

22,

23]. Students and educators navigated unfamiliar technologies while managing personal challenges [

24,

25,

26]. Learning environments shifted from institutions to homes, blurring boundaries between personal and academic spaces [

27,

28,

29].

1.2. Pre-Pandemic Context and the Digital Learning Landscape

Prior to the pandemic, online learning was quite peripheral in mainstream higher education, catering mainly to nontraditional students and various professional development courses [

30,

31,

32]. The role of technology integration in higher education had been rising gradually, with traditional face-to-face classroom instruction remaining the mainstay in most institutions [

33,

34]. Students’ perceptions and attitudes towards online learning were quite varied, depending on various issues such as technological skills, personal learning styles, course and discipline demands, and cultural norms regarding learning and higher education [

35,

36,

37].

Established theoretical frameworks provide lenses for understanding technology-mediated learning. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) posits that perceived usefulness and ease of use drive technology adoption—constructs reflected in this study’s measures of platform proficiency and comfort with distance learning. The Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework emphasizes social presence and cognitive presence for effective online learning, dimensions captured in preferences for synchronous versus asynchronous modalities. The pandemic provided an opportunity to examine these theoretical constructs under conditions of mandatory rather than voluntary adoption [

38,

39].

Pre-pandemic research has shown ambiguous attitudes among students towards distance learning. Some research has reported positive attitudes, especially among those with high information technology skills and those appreciative of autonomy and flexibility. Meanwhile, research has also shown skepticism towards distance learning quality, with perceived diminished contact with teachers and peers, and difficulties with motivation and self-regulation [

40,

41,

42]. Such pre-pandemic research has been crucial in providing insights into what might be some differing characteristics of emergency remote teaching, as encountered during COVID-19, and contrasted with traditional and designed online learning interventions, respectively [

43,

44,

45].

1.3. The Greek Educational Context

The Greek higher education system had its own set of difficulties in implementing pandemic-imposed restrictions. Like many European countries, Greek universities boasted a long tradition of classroom teaching, with lecture rooms, seminars, and labs at their heart [

46,

47,

48,

49]. The new move to online teaching and learning involved not only technological adjustments, but also significant cultural and intellectual change. Greek students, brought up with the social and communal aspects of campus life, found themselves isolated at home, with academic progress squeezed into computer monitors [

50,

51,

52,

53]. Infrastructure disparities between urban and rural areas, coupled with socioeconomic differences in technology access, created uneven conditions for the online learning transition in Greece [

54,

55,

56]. These access-related challenges are examined in detail in

Section 4 [

57,

58,

59].

1.4. Theoretical and Practical Significance

Understanding student experiences during this exceptional period yields insights beyond crisis response [

60,

61,

62,

63]. The pandemic served as an involuntary global experiment in educational technology adoption, providing evidence for future hybrid learning design. This research is significant for three reasons. First, attitudes are learned dispositions that affect behaviors and outcomes. Second, the mandatory nature of this transition offers insights into technology adoption under necessity rather than choice—a scale not previously explored. Third, assessing emergency policy efficacy informs future educational planning [

64,

65,

66].

1.5. Research Scope and Objectives

This research assesses students’ attitudes, experiences, and responses to mandatory distance learning in Greek higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020 to May 2021). The study captures both immediate responses and evolved attitudes from continued practice. The research covers multiple dimensions: technological (infrastructure, platform usage, technical difficulties), pedagogical (synchronous/asynchronous preferences, perceived effectiveness), psychosocial (isolation, motivation, stress), and demographic (gender, age, academic level).

This research adopts the students’ perspective, recognizing that students are one of the key stakeholders in any change that takes place within an institution of learning. The students come first in this research, and its endeavor is to provide insight into research-informed decision-making in learning and teaching. The research takes into consideration the challenges and opportunities that came with the pandemic, recognizing that, although there were challenges, innovations and new learning pathways emerged.

The time relevance of this research matters, as it encompasses experiences under unique historical conditions where traditional alternatives to education had not been accessible at all. This makes the research unique, as opposed to research undertaken by individuals learning online voluntarily or those involved in hybrid learning, as students get to make choices from available alternatives. The mandatory aspect of online learning under pandemic conditions offers insights into adaptability under alternative conditions not considered by students.

1.6. Research Questions

Based on the critical need to understand student experiences during this unprecedented educational transformation, this study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the overall attitudes and satisfaction levels of Greek higher education students toward distance learning implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic?

RQ2: What are the primary technical, pedagogical, social, and emotional challenges students encountered during the transition to and sustained period of distance learning?

RQ3: How do student preferences differ regarding synchronous (real-time) versus asynchronous (self-paced) learning modalities, and what factors influence these preferences?

RQ4: To what extent does technological infrastructure, particularly internet connectivity and device access, predict student attitudes toward and success in distance learning?

RQ5: What demographic factors, including gender, age, academic level, and field of study, are associated with different distance learning experiences and preferences?

RQ6: What are students perspectives on the future of education, particularly regarding the potential for distance learning to replace or complement traditional face-to-face instruction?

RQ7: What specific features, supports, or modifications would students recommend to improve distance learning effectiveness and satisfaction?

These research questions collectively aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the student experience during an unprecedented period of educational disruption, generating insights that can inform both immediate improvements to distance learning and long-term educational transformation strategies.

1.7. Theoretical Framework and Variable Alignment

This study operationalizes constructs from established theoretical frameworks through specific survey measures.

Table 1 presents the alignment between theoretical frameworks, their key constructs, and the study variables designed to capture these dimensions. The Technology Acceptance Model’s emphasis on perceived ease of use is reflected in measures of platform proficiency time and comfort with distance learning courses. The Community of Inquiry framework’s social and cognitive presence dimensions are captured through synchronous/asynchronous preference items and participation patterns. Digital Divide Theory’s focus on infrastructure access is operationalized through connectivity measures and device availability variables.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

The study used a quantitative cross-sectional approach to examine students’ attitudes and experiences with distance education in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in Greek HE institutions. The need for the cross-sectional approach was imperative in understanding students’ experiences at this decisive time of disruption brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, lasting from March 2020 to May 2021. The methodology used in research was quantitative, making it feasible to examine attitudes, preferences, and experiences, and test statistical associations between research variables.

The research methodology included both descriptive and analysis parts so that all aspects of distance learning could be discussed thoroughly. The descriptive part of analysis was concerned with reporting frequency of attitudes, usage of technology, and problems faced by students, while analysis involved predictions through correlation and regression analysis.

2.2. Participants and Sampling

The target group consisted of students in Greek higher education institutions, and all of these students had to make the transition to distance learning due to COVID-19. Both undergraduate and graduate students, including Ph.D. students, belonging to all academic disciplines, were included in this target group. The participants were obtained by purposive sampling. This was done through email networks and academic departments.

The final pool consisted of participants numbering 477, and all satisfied criteria regarding active enrollment between March 2020 and May 2021, distance learning, at least one complete semester, over 18 years of age, and signing an expression of consent. Students attending institutions with exclusively pre-pandemic distance learning programs and those on leave of absence did not comprise eligible participants.

2.3. Research Instrument

The structured questionnaire was designed for this research and included pandemic-related items and established measurement tools. The stages involved in designing this questionnaire included conducting a literature review, seeking advice from academic researchers, and testing it with students before refining it—this final version consisted of 31 main questions and six themes (see

Table 2).

The demographic part of the questionnaire sought information regarding gender, age group, level of education, and year of study. Questions regarding technology access included usage of platforms such as synchronous platforms such as Microsoft Teams, Skype, Zoom, and Webex, and asynchronous platforms such as Moodle and eClass. The section regarding challenges included difficulties encountered, assistance required, and time taken to master platforms.

The core attitudinal measurement employed five items using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all” (1) to “Very much” (5). These items assessed overall satisfaction with distance learning, comfort with online courses, and preferences for synchronous versus asynchronous modalities. The specific items were: “I like distance learning” (E1), “I feel comfortable with distance learning courses” (E2), “I prefer synchronous distance learning” (E3), “I prefer asynchronous distance learning” (E4), and “I believe that a combination of synchronous and asynchronous distance learning is ideal” (E5).

Several constructs were assessed using single-item measures, a decision driven by practical considerations of survey length and participant burden during an already stressful period. While single-item measures preclude traditional internal consistency assessment (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha), research supports their validity under specific conditions [

67,

68]. The attitude items (E1–E5) used concrete, unambiguous language referring to specific, directly observable preferences (e.g., ‘I prefer synchronous distance learning’) rather than abstract latent constructs, meeting Rossiter’s (2002) [

69] criteria for appropriate single-item measurement. The strong intercorrelations observed among conceptually related items (e.g., r = 0.623 between liking distance learning and feeling comfortable) provide indirect evidence of convergent validity. Nevertheless, future research should employ validated multi-item instruments where available to enable formal reliability assessment.

2.4. Data Collection Procedures

Data collection occurred over four weeks in 2021 using an online survey platform. Institutional approval was obtained prior to data collection. All participants provided informed consent, and data were stored securely with restricted access.

The electronic distribution strategy was designed to reach students through various channels to ensure diverse representation. Of the 700 students who accessed the online survey, 477 completed all aspects of the questionnaire, with a completion rate of 75.7%. This high rate of completion indicates that it was an acceptable length and was of relevance to those responding.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted with SPSS Version 26.0, with alpha set at 0.05 for hypothesis testing. Given the exploratory nature of this investigation and its focus on generating insights for educational policy rather than confirmatory hypothesis testing, trends approaching conventional significance (

p < 0.10) are also reported. This threshold is consistent with recommendations for exploratory research in applied educational contexts, where Type II errors (failing to identify potentially meaningful relationships) carry practical costs for policy development [

70]. However, findings at 0.05 <

p < 0.10 are explicitly labeled as ‘marginally significant’ and interpreted with appropriate caution regarding their preliminary nature. Effect sizes are reported alongside

p-values to facilitate assessment of practical significance independent of sample size limitations.

2.5.1. Descriptive Analysis

The descriptive statistics were used to describe and define the characteristics of the sample. The frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and means and standard deviations for continuous measures, were calculated. The frequencies of responses and combined positive and negative percentages were calculated for individual and scale items of attitude statements that used the Likert scale.

2.5.2. Inferential Analysis

The analysis of correlation was used to determine variable associations through Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Two multiple linear regression models were created to find predictors of distance learning preferences.

The model diagnostic tests included checking for multicollinearity by Variance Inflation Factors of VIF < 10, homoscedasticity by residual plots, normality of residuals by P-P plots, and independence of residuals by Durbin-Watson statistics shown in

Table 3.

2.6. Participant Demographics

The demographic nature of the sampling provided varied viewpoints based on academic level and subjects. The gender demographics provided equal viewpoints between male and female students, with ages stratified from traditional students aged 18–22 to mature students aged 31 and above. The academic demographics included students at all academic years from first to sixth year undergraduate students, postgraduate students seeking higher qualifications, and doctoral students in research programs, as shown in

Table 4.

2.7. Methodological Considerations

The research was also faced with various methodological limitations, which affected the results’ outcomes. The small sample size of 477 participants was not ideal, particularly with respect to testing small and medium effect sizes. The post hoc analysis revealed that there was enough power to handle regression analyses with four predictors.

The purposive sampling strategy, while appropriate for reaching students with direct pandemic learning experience, introduces several potential biases that warrant explicit acknowledgment. First, distribution through academic email networks may have systematically excluded students who had disengaged from institutional communication channels—potentially those most negatively affected by distance learning challenges. Second, the online survey format inherently required functional internet access and basic digital literacy, creating circular selection bias when studying technology-related experiences: students unable to access online surveys are precisely those most likely to have experienced technology-related barriers. Third, voluntary participation likely attracted students with stronger opinions (either positive or negative) about distance learning, potentially underrepresenting those with neutral or ambivalent attitudes who felt less compelled to respond. Fourth, the 75.7% completion rate, while acceptable for online surveys, leaves open questions about systematic differences between completers and non-completers—respondents who abandoned the survey may differ meaningfully from those who completed it. Fifth, students who experienced severe difficulties may have withdrawn from their programs entirely and thus were unavailable for sampling. Collectively, these limitations suggest the sample may overrepresent students who successfully adapted to distance learning. Findings should therefore be interpreted as reflecting the experiences of engaged, digitally connected students rather than the full population of affected learners.

Measurement issues included potential social desirability bias from self-report measures, and potential recall bias from measurement over an extended time period. The choice to measure some constructs with single items precluded assessment of those measures’ reliabilities, although it was necessary to keep the questionnaire length reasonable.

The temporal context under which the data was collected, undertaken after the most intensive period of distance learning, may well have affected participants’ responses, either through recency, adaptation, or retroactive re-evaluation. Such potential biases were addressed in analyzing the findings.

2.8. Quality Assurance

To ensure rigorous analysis, systematic procedures of quality assurance were undertaken. All entries into the dataset were checked for accuracy, and statistical assumptions were checked prior to analysis of each query. The results were explored with regard to statistical and pragmatic significance, and effect size was determined and reported together with

p-value statistics. Replications of principal analyses under various specifications were undertaken to ensure robustness of results (

Table 5).

This methodological approach ensured trustworthy findings about student experiences during educational disruption. The combination of descriptive and inferential analyses defined student experiences and identified factors affecting distance learning success.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.1.1. Participant Characteristics

The research involved 477 participants from Greek higher education institutions, all of whom went through the transition to distance learning brought by the COVID-19 crisis. The participants came from varied academic stages and subjects, ensuring a holistic view of students affected by this extraordinary circumstance.

3.1.2. Technology Infrastructure and Platform Usage

Results of technology usage analysis revealed significant disparities in students’ preparedness for online learning. The largest group of students accessed both synchronous and asynchronous platforms, with 69.8% students accessing both platforms. The synchronous platform predominantly accessed was Microsoft Teams, and all students accessed eClass, which was used as an asynchronous platform. Internet connectivity was also found to be quite varied, with wireless connectivity predominant, though not all students had constant connectivity.

The time taken to execute distance learning after the lockdown in March 2020 differed from one institution to another. The majority of the departments started delivering distance learning online courses within 1–2 weeks, while others took up to 4 weeks to accomplish this. This can affect students’ first impressions and attitudes towards emergency remote teaching.

3.2. Student Attitudes Toward Distance Learning

3.2.1. Overall Satisfaction and Comfort

Student attitudes toward distance learning were predominantly positive, though there was notable variation among individuals. Analysis of the core attitude items demonstrated that most students successfully adapted to online learning despite the challenging circumstances (

Table 6).

The data revealed that 67.9% of students expressed positive attitudes toward distance learning, combining those who liked it “very” much (37.7%) and “very much” (30.2%). Only 13.2% expressed negative attitudes, responding “not at all” (5.7%) or “a little” (7.5%). This positive overall reception suggests successful adaptation despite the emergency nature of the transition.

Comfort levels with distance learning courses were even higher, with 71.6% of students reporting high comfort. The combined percentage of students who felt “very” (35.8%) or “very much” (35.8%) comfortable was identical, indicating consistent positive experiences. Remarkably, only 3.8% of students reported discomfort with online courses, suggesting that technical and pedagogical challenges did not prevent most students from achieving a sense of ease with the new learning format.

3.2.2. Learning Modality Preferences

Learning modality preferences revealed insights for future course design. Only 22.6% of participants strongly preferred synchronous learning, despite its similarity to face-to-face communication.

Asynchronous learning was shown to be more appealing with 43.4% of students preferring it, although “very much” was slightly more popular at 30.2%. It appears that students found it appealing to learn at their own pace, and asynchronous learning was seen as allowing this, although this method and synchronous learning did not quite address all students’ needs.

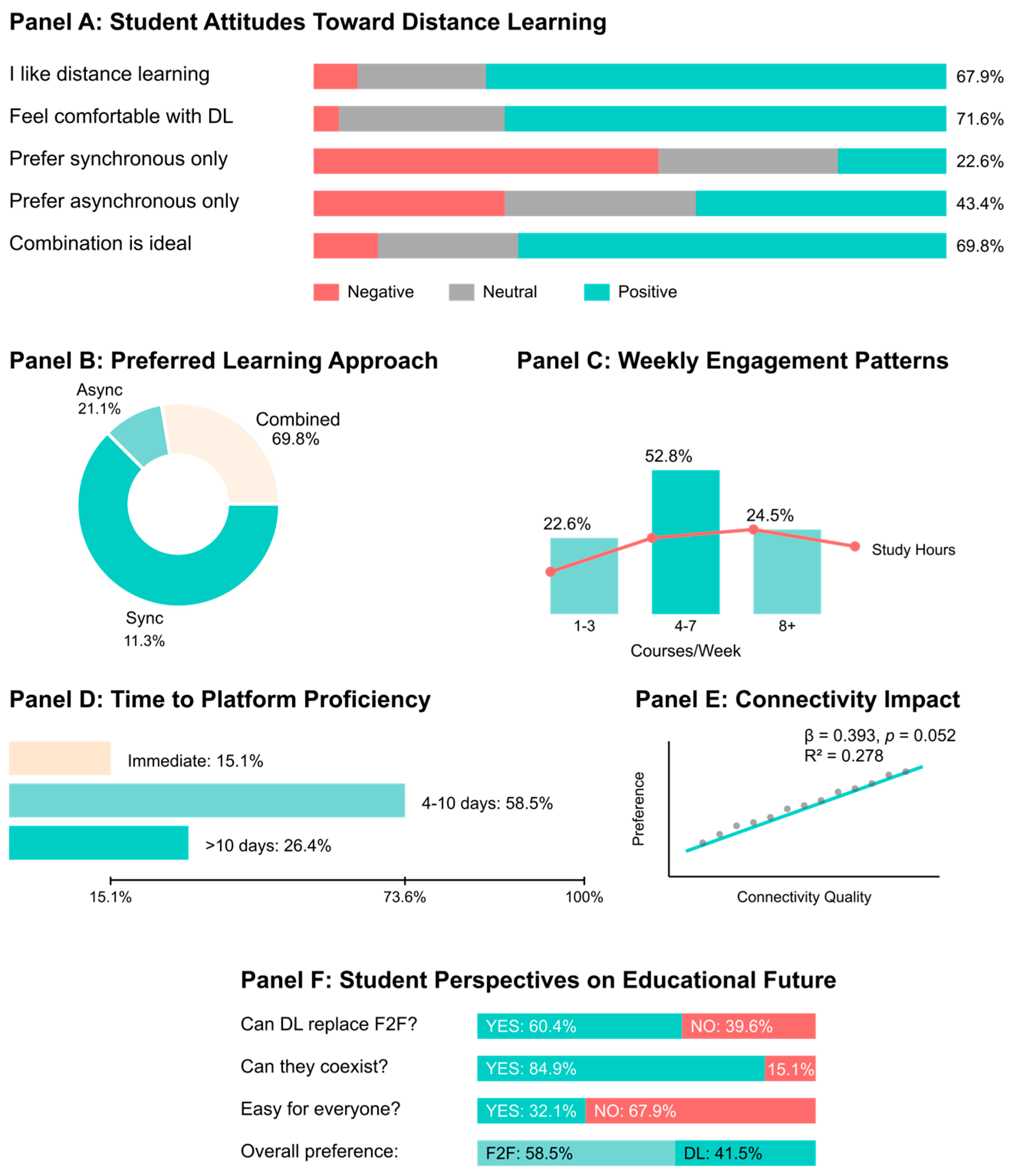

The blend of synchronous and asynchronous learning was found to be the most preferable method, with 69.8% of participants thinking that this is the most preferable method. The response choice “very much” to this question received 47.2% of all responses, which is an indication of high agreement and represents the strongest agreement with any of the response choices in all questions regarding preferences. Six-panel

Figure 1 analyzing distance learning experience.

Panel A displays student attitudes using stacked horizontal bars (orange for negative, gray for neutral, teal for positive responses), revealing 67.9% positive attitudes toward distance learning and 71.6% comfort levels with online courses. Panel B illustrates learning modality preferences through a donut chart (teal shades), showing 69.8% favor combined synchronous-asynchronous approaches. Panel C presents weekly engagement patterns with bars indicating 52.8% of students attend 4-7 courses weekly, while a red line tracks study hours distribution. Panel D demonstrates adaptation timeline with cascading bars showing 58.5% achieved platform proficiency within 4-10 days and cumulative percentages reaching 73.6% within this timeframe. Panel E displays the relationship between connectivity quality and combined learning preference through gray dots (individual responses) and a teal regression line, revealing connectivity as the strongest predictor (β = 0.393, p = 0.052). Panel F compares future educational perspectives using paired bars (teal for yes/positive, orange for no/negative), showing 84.9% support for coexistence of distance and face-to-face education despite 58.5% maintaining preference for traditional face-to-face instruction.

3.3. Challenges and Adaptation

3.3.1. Technical Difficulties and Support Needs

Students encountered various challenges during the transition to distance learning, with technical issues being prominent. The ease of initial platform use varied considerably, with scores ranging from 1 (very difficult) to 5 (very easy). While some students found platforms immediately intuitive, others required substantial time to develop proficiency (

Table 7).

A majority of students (58.5%) acquired proficiency in distance learning platforms within 4–10 days, while 26.4 percent acquired it after over 10 days. Just 15.1 percent acquired it immediately, which indicates the learning process involved with implementing emergency remote teaching.

The issues primarily faced by students ranged over various aspects. Access-related issues, as well as technology-related difficulties, were often encountered, including a lack of experience with learning technology platforms. Insufficient equipment and poor connectivity also caused problems, although some students faced no serious issues.

3.3.2. Participation Patterns

The analysis of participation trends has shown various degrees of students’ involvement. The students differed with respect to the number of courses and time they spend with academic pursuits each week, as shown in

Table 8.

Most students (52.8%) were involved in 4–7 courses per week, which was considered to be a standard full course load. Study hours per week were found to be evenly distributed regarding moderate (7–13 h, 34.0%) and considerable (14–20 h, 35.8%) levels. Interestingly, 69.8% students were involved in both synchronous and asynchronous learning sessions, reiterating the combined method preferences confirmed by attitude assessment.

3.4. Perspectives on Educational Future

Student opinions on the future role of distance learning in education revealed complex perspectives on the place of technology in academic instruction (

Table 9).

Although 60.4% of students think that distance education has the potential to replace traditional learning, not all students share such thoughts, as 39.6% recognize that traditional classroom learning is irreplaceable. The realization that distance education is not accessible to all students, as seen in “no” responses at 67.9%, indicates that students are aware of inequities.

The high level of support for distance and face-to-face learning to coexist (84.9%) reveals students’ plans for a hybrid, not completely substitutionary, future with traditional approaches. Despite choice pressure, 58.5% opted for face-to-face delivery, while 41.5% in favor of distance learning is quite high and may be driven by enthusiasm from their pandemic experiences.

3.5. Regression Analysis Results

3.5.1. Predictors of Combined Learning Preference

Multiple regression analysis was conducted to identify factors predicting preference for combined synchronous and asynchronous learning. The model included connectivity type, device purchases, and platform usage as predictors (

Table 10).

The model accounted for 27.8% of variance in combined learning preference (R

2 = 0.278), though the overall model approached but did not reach conventional statistical significance (F (4, 26) = 2.500,

p = 0.067). Internet connectivity emerged as the strongest individual predictor (β = 0.393,

p = 0.052). While this result does not meet the conventional α = 0.05 threshold, several considerations support its cautious interpretation: (a) the effect size is medium-to-large by Cohen’s (1988) [

70] conventions, suggesting practical importance; (b) the theoretical basis for infrastructure affecting learning preferences is well-established; and (c) the pattern aligns with qualitative findings from pandemic education research. Nevertheless, this finding should be considered preliminary and requires replication with larger, more representative samples before firm conclusions are drawn. The modest overall model fit suggests additional unmeasured factors contribute substantially to learning modality preferences.

Device purchase was positively, though not significantly, correlated with combined learning preference (β = 0.313, p = 0.099), and this indicates that those students who acquired devices to support distance learning may have tended towards combined approaches. The platform usage predictors were not significant, and this shows that it was not as important to be familiar with platforms as it was to be familiar with infrastructure.

3.5.2. Demographic Predictors of Distance Learning Preference

The second regression analysis was conducted to see if demographic variables were predictive of a preference for modern distance-learning methodologies (

Table 10). The demographic model failed to achieve statistical significance (R

2 = 0.048, F (4, 48) = 0.605,

p = 0.660), with no individual predictor reaching significance. The minimal explained variance indicates that demographic factors, as measured in this study, do not meaningfully predict distance learning preferences in this sample. Given the non-significant overall model, detailed interpretation of individual predictor coefficients is not warranted. These null findings should be interpreted primarily as absence of evidence for demographic effects rather than evidence of their absence—the sample size and demographic homogeneity (predominantly young undergraduates) may have been insufficient to detect small but meaningful effects. The regression coefficients are presented in

Table 11 for transparency and to inform power analyses for future research, not to support substantive conclusions about demographic influences.

3.6. Correlation Analysis

Correlation analysis revealed meaningful patterns in the relationships among attitude items, providing insight into the structure of distance learning preferences (

Table 12).

There was a strong positive relationship between overall liking of distance education and comfort with online classes (r = 0.623, p < 0.01), indicating that these attitudes correlate and seem to emerge simultaneously. The liking of blended delivery was also positively correlated with overall satisfaction (r = 0.478, p < 0.01) and overall comfort (r = 0.521, p < 0.01), suggesting that students appreciative of hybrid approaches generally enjoyed their overall experience.

The weak negative relationship between asynchronous and synchronous preferences, with r = −0.156 and ns, indicates that these are not opposite points in one dimension, but to a degree, independent preferences. This confirms that students greatly prefer combined approaches, as they found value in each.

3.7. Summary of Key Findings

The findings illustrate a predominantly positive attitude towards distance learning among Greek higher education participants, with 67.9% showing positive attitudes and 71.6% feeling comfortable with online learning. The majority’s attitude towards learning synchronously and asynchronously together, at 69.8%, indicates that students recognize and appreciate the value of interaction and self-paced learning.

Technical infrastructure, specifically internet connectivity, was revealed as the main predictor of having positive attitudes towards blended learning, with higher explanatory value than demographic or platform-related aspects. Although most of the students were able to adjust to distance learning within 4–10 days, the realization that online learning is not accessible to all students to an equal degree (67.9%) reveals an understanding of inequity.

The consensus is that distance and traditional forms of education can and should exist side by side, with 84.9% holding this view, and with 58.5% of students preferring traditional forms of education, it is likely that the future of higher education lies not in revolutionary new approaches, but in making traditional approaches more flexible and adaptable.

4. Discussion

This holistic research inquiry responds to seven research questions, each focusing on aspects of the learners’ experience in adapting to the transition enforced by the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, shifting to distance learning methodologies. The results obtained from this research reveal intricate learners’ transition and development experiences, influencing and transforming, in effect, theories and approaches regarding distance learning technology adoption and application in crisis conditions.

4.1. RQ1: Overall Attitudes and Satisfaction Levels

The first research question investigated attitudes of students towards pandemic-driven distance learning and found a generally positive attitude towards distance learning, which surpassed initial expectations. The majority of Greek higher education students had positive attitudes towards distance learning, and more students felt comfortable with distance learning and online courses. This was despite its unexpected and emergency nature of its application and overcoming various technological and pedagogical difficulties encountered by students and educators [

71,

72,

73,

74].

Such findings dispute traditional beliefs regarding the need for proper planning and progressive execution of online learning adoption. Conventional literature assumes that prior preparation, teacher training, and familiarization of students are mandatory pre-requisites before commencing distance learning. But what has emerged under the pandemic scenario is that if alternative learning systems are not available, students can quickly adjust to new learning platforms with unexpected success. Such adaptability implies that resistance to online learning may not be inability, but choice prior to the pandemic scenario [

75,

76,

77].

The high comfort levels supported suggest that skills in technology proficiency are not as intimidating as was earlier perceived. The ability to operate different platforms, different forms of electronic material, and academic pursuits entirely under mediated instruction indicates that students possess dormant skills that were unlocked by crisis developments. This has very important implications with regard to technology integration in the future, and one can presume that such concerns regarding preparedness by institutions are likely to be unwarranted [

78,

79,

80,

81,

82].

The difference between comfort and preference, however, reveals certain crucial nuances. The students were prepared to adapt to technological aspects with ease, but their adaptability does not necessarily mean that students prefer to learn online only. This reveals that effective crisis management and effective learning outcomes, such that students can cooperate with ease in suboptimal conditions although appreciating their limitations, are not at all alike [

83,

84,

85].

Addressing RQ1, which examined overall attitudes toward distance learning, findings revealed predominantly positive responses. A total of 67.9% of students expressed positive attitudes, with only 13.2% reporting negative attitudes. This positive reception suggests successful adaptation despite the emergency transition context. These findings align with TAM’s post hoc attitude formation mechanism, wherein successful task completion shapes subsequent attitudes [

86]. International studies report comparable patterns: Batdı et al. [

86] found similar positive responses in their meta-analysis of COVID-19 online learning effectiveness, while Gamage et al. [

87] documented high engagement in hybrid settings.

4.2. RQ2: Primary Challenges Encountered

The diversified difficulties emerging from distance learning, as revealed by the second research question, include technology, teaching, social, and emotional, thereby validating that distance learning difficulties are not merely technological in nature. The technological difficulties, even if significant, are intertwined with teaching difficulties such as issues with focusing, poor teaching, and poor feedback. The limited social interaction and home difficulties contributed towards personal difficulties such as home distractions and screen fatigue [

88,

89,

90,

91].

The interrelatedness of these issues implies that finding effective solutions to distance learning difficulties necessitates holistic, not piecemeal, strategies. It is impossible to find technological fixes to pedagogical issues or address social isolation through enhanced pedagogical practice [

92,

93,

94,

95]. The fact that difficulties emerge along several dimensions implies that students experiencing one form of problem are likely to be dealing with multiple difficulties at once, providing one explanation for inequitable outcomes [

96,

97,

98].

The salience of connectivity problems, both as a technological problem and determinant of overall satisfaction, highlights infrastructure’s bedrock status. Connectivity problems spawn ripple problems with regard to attending synchronous sessions, turning in assignments, accessing resources, and collaborating with peers. This confirms worries about the digital divide and precisely identifies the process by which inequalities among infrastructure relate to disadvantage in education [

99,

100,

101,

102].

The social and emotional issues that were identified demonstrate the not-so-visible expenses that come with distance learning, something that is overlooked in its efficiency-related debate. The absence of collateral learning with peers, interaction with instructors, and group study sessions form part of those losses, which can never be replaced by recordings and electronic materials, respectively. The above-mentioned highlights that effective online learning has to be designed with connections in mind, not after [

103,

104,

105].

Addressing RQ2, technical challenges emerged as the primary barrier to effective distance learning. Connectivity problems significantly affected participation in synchronous sessions, with students reporting difficulties maintaining stable connections during live lectures. These findings extend Digital Divide Theory by demonstrating how technical barriers cascade into pedagogical impacts. Per the CoI framework, unstable connectivity undermines social presence by disrupting real-time interaction [

106,

107,

108]. Li [

106] documented similar urban-rural disparities in post-pandemic China, while Adeniyi et al. [

107] found comparable infrastructure gaps across USA and African contexts.

4.3. RQ3: Synchronous Versus Asynchronous Preferences

The third research question, concerning modality preferences, has led to the most interesting and significant finding emerging from the research, which is that there was an overwhelming preference for combined modalities over synchronous and asynchronous approaches alone. The pattern established by this preference reflects an advanced level of understanding regarding the benefits of each modality and recognizing that face-to-face and self-paced environments offer differing benefits [

109,

110,

111,

112,

113].

The comparatively weak desire for exclusive synchronous learning, although it is more similar to traditional learning, indicates that learners are not merely attempting to transfer traditional learning experience into an online context. Instead, they value asynchronous learning’s convenience and at the same time understand its benefits with regard to synchronous learning, which can provide immediate feedback and build social presence. This indicates that learners make judgments regarding learning modalities based not on surface-level resemblance to traditional learning, but its affordances [

114,

115,

116,

117,

118,

119].

The huge interest in combined modalities has massive implications for designing learning events. Contrary to traditional alternative approaches such as asynchronous and synchronous, it appears that each has unique functions that are optimally addressed by combining them strategically. Abstract theories can be offered in asynchronous environments designed for repeated review, with practice sessions, discussion, and problem-solving carried out in synchronous environments designed for collaborative learning and immediate interaction [

120,

121].

The independence of synchronous and asynchronous preferences, shown by their weak correlation, defies efforts to define these as opposite points along one continuum. This implies that students preferring synchronous learning may not necessarily dislike asynchronous learning, and designing hybrid learning that optimizes each based on their strengths may not necessarily involve making sacrifices regarding one over the others [

122,

123,

124,

125,

126].

Addressing RQ3, hybrid learning emerged as the strongly preferred modality (69.8%). This preference reflects students’ desire to combine real-time interaction with self-paced flexibility. Interpreted through the CoI framework, hybrid models balance all three presence types: synchronous components support social and teaching presence through real-time interaction, while asynchronous components enhance cognitive presence by allowing reflective engagement [

127,

128,

129,

130]. This interpretation aligns with Nyman et al. [

127], who found health sciences students valued hybrid formats for balancing clinical communication skills with self-directed study.

4.4. RQ4: Technological Infrastructure as Predictor

The fourth research question explored the impact of infrastructure within distance learning, and connectivity emerged as the strongest determinant of attitudes towards Blended Learning approaches. The significance of this finding goes far beyond statistical associations, raising critical questions about learning equality and the role of institutions in providing learners with access to learning [

131,

132,

133].

The supremacy of connectivity over demographic variables in defining satisfaction defies individualistic theories about distance learning success. Instead, infrastructure stands out as the decisive factor, which indicates that investments by institutions and governments in connectivity can greatly enhance distance learning success. The infrastructure concept redefines accountability from individual students about overcoming personal deficiencies to institutions and governments, making them responsible entities to provide infrastructure support to distance learning [

134,

135,

136].

The discovery that device purchase had marginal positive associations with satisfaction indicates that technology access has various channels. Students with technology investments may well have established stronger mental affiliation with distance education, converting need into an opportunity. The mental aspect of technology adoption should be explored in more detail, and its relationship with institutionally provided devices and technology usage, rather than technology access [

137,

138].

The modest variance explained by the regression equation indicates that there is more to distance learning success than captured by this equation. Unaccounted-for variables may include, but are not restricted to, home learning environment, family support, prior online experience, and teacher effectiveness. This phenomenon indicates that more than one aspect must be addressed if distance learning success is to be promoted, and infrastructure, although necessary, is not a sufficient condition to ensure success [

139,

140].

Addressing RQ4, connectivity emerged as the strongest predictor of positive attitudes (β = 0.393), though the

p-value of 0.052 exceeds conventional significance thresholds. This marginally significant result warrants cautious interpretation as a trend requiring further investigation rather than confirmed findings. Nevertheless, the direction and magnitude of this relationship align with Digital Divide Theory’s emphasis on access as foundational to technology acceptance. Müller et al. [

141] similarly found infrastructure stability predicted course effectiveness in blended designs, while Burbage et al. [

142] documented CoI-mediated pathways from technical reliability to self-efficacy [

143].

4.5. RQ5: Demographic Factors and Differential Experiences

The fifth research question examined whether demographic factors predicted distance learning preferences, yielding null results across all variables examined (gender, age, education level, device availability). The failure to find significant demographic effects could reflect several possibilities: the sample may have been insufficiently powered to detect small effects; the predominantly young undergraduate sample may have restricted variance on key demographic dimensions; or pandemic conditions may have genuinely leveled traditional demographic differences in technology-related attitudes [

144,

145,

146,

147,

148,

149]. Rather than concluding that demographics are unimportant for distance learning, we note that this study was not optimally designed to test demographic moderator effects. More targeted investigations with stratified sampling and adequate representation across demographic groups would be needed to draw firm conclusions about whether and how demographic factors influence distance learning success [

150,

151,

152]. The null findings do suggest, at minimum, that within a relatively homogeneous student population, other factors—particularly infrastructure access—may be more consequential than individual demographic characteristics [

153,

154].

The null demographic findings warrant cautious interpretation. Several explanations are plausible: (a) crisis conditions may genuinely level traditional demographic stratification when everyone must adapt; (b) the sample’s demographic homogeneity (predominantly young undergraduates) may have restricted variance insufficiently to detect meaningful effects; (c) the study may have been underpowered for small demographic effects; or (d) infrastructure factors may have overwhelmed demographic variation in this context. We cannot definitively distinguish among these interpretations. The minimal demographic effects contrast with some pre-pandemic literature suggesting gender and age differences in technology attitudes, but are partially consistent with recent pandemic-era studies. However, Li’s (2025) [

106] findings of meaningful urban-rural differences suggest that demographic effects may emerge more clearly in studies specifically designed to capture such variation through stratified sampling. The null findings should therefore be interpreted as absence of evidence rather than evidence of absence, and more targeted investigations would be needed to draw firm conclusions about demographic moderators of distance learning success.

4.6. RQ6: Future Educational Perspectives

The sixteenth research question involved analyzing students’ views regarding post-Coronavirus pandemics and what they envision concerning learning. This inquiry was crucial in determining their attitudes, which, in most cases, may not necessarily be polarized between traditional and distance learning. The belief, however, that distance learning can theoretically and possibly replace traditional teaching shows their high level of understanding regarding different teaching methodologies [

155,

156].

The awareness by students that distance and face-to-face education can co-exist is an indication of advanced thinking regarding complementarity rather than competition in the sector. The existence of such robust support for coexistence indicates that students foresee their own futures concerning flexible choices depending upon contents, context, and individual conditions as opposed to limitations by institutions [

157,

158,

159,

160,

161].

The recognition that not all students can easily and readily participate in distance learning indicates an awareness of critical consciousness regarding matters of equal and fair educational provision. The students understand that while they may be able to adjust and succeed, this does not eradicate difficulties faced by others, indicating an awareness of things such as privilege and barriers to learning. This indicates that students possess social awareness, which can be utilized to ensure fair and equitable development in academic policies by making students part of transformations in learning institutions.

The majority’s choice to learn face to face, regardless of prior positive experiences with online learning, confirms that some values in schools refuse to be digitized. The unofficial school curriculum, including campus life and intellectual dialog, has an inestimable value that students refuse to give up. This tendency warns against technological solutions, focusing instead on expediency rather than comprehensive education [

162].

Addressing RQ6, the strong hybrid preference documented in

Section 4.3 (69.8%) has clear implications for future educational planning. Students envision continued integration of online components within traditional structures rather than full replacement of face-to-face instruction. Post-pandemic research validates this preference. Sosnova et al. [

163] found hybrid formats enhanced learning effectiveness across European institutions, while Mulenga and Shilongo [

164] documented successful hybrid innovations in developing contexts. These findings suggest the pandemic accelerated lasting pedagogical transformation [

165].

4.7. RQ7: Recommendations for Improvement

The implicitly researched question of improvement potential in the seventh research question arises from all findings, pointing towards various paths towards optimizing distance learning effectiveness. Learning students’ experiences suggest improvement avenues in infrastructure, teaching, and support services with practical outlook limitations regarding what can and what cannot be accomplished in distance learning education, respectively, concerning [

166,

167].

The prominence of connectivity issues highlights the need to prioritize infrastructure improvement above all else. Unfortunately, infrastructure is not exclusive to improved bandwidth and must include sound devices, proper software, IT support, and creating technology proficiency. Holistic infrastructure initiatives must focus on all aspects, not attributing technological success to internet connectivity alone [

168,

169,

170,

171].

Some improvement suggestions in teaching based on students’ experiences include improved integration of synchronous and asynchronous aspects, improved communication of teaching expectations, provision of feedback, and encouragement of interaction with peers. The need for combined approaches indicates that teaching in online environments does not rely on either traditional teaching or self-directed learning, and new teaching approaches must be created that take advantage of all three aspects dynamically [

172,

173,

174,

175].

The improvement of support services is seen as very important to address these identified social and emotional issues. Mental health support, academic advice, and learning communities need to be rethought in remote environments. The pandemic has shown that support services are vital to keep students engaged, and their absence has caused isolation and disconnection, which technology cannot solve by itself [

176,

177,

178,

179,

180].

The three improvement domains identified—infrastructure, pedagogical design, and support services—map coherently onto the theoretical frameworks guiding this study. Infrastructure improvements address Digital Divide Theory’s emphasis on access as foundational to participation; pedagogical innovation relates to TAM’s ease of use and usefulness constructs by shaping how students experience online learning; and support services address the Community of Inquiry framework’s social presence requirements by providing human connection and guidance. This convergence suggests that the three frameworks collectively provide comprehensive guidance for hybrid education design: none alone is sufficient, but together they identify the key dimensions requiring coordinated attention. These improvement priorities align with recommendations from recent international scholarship, including Bonk and Graham’s (2023) comprehensive handbook on blended learning [

181], Tedeschi et al.’s (2024) analysis of remote teaching patterns [

182], and Azouri and Karam’s (2023) findings from the MENA region [

183], confirming that these considerations transcend specific national or disciplinary contexts.

4.8. Synthesis and Theoretical Implications

Taken together, these results make it clear that pandemic-driven distance learning caused more positive outcomes than were envisioned and that pressing issues must be addressed. The success of remote learning in times of crisis has shown resilience and adaptability, and hybrid approaches suggest long-term change regarding what can be expected in educator-delivered services. The results generalize theory by showing that crisis-context adoption is not equivalent to voluntary technology acceptance. The Technology Acceptance Model’s perceived ease of use and usefulness help explain, but not the hybrid preference, and so explanations include teaching fit and social presence. Theoretically, modality complementarity and crisis adaptation need to be treated separately as distinct phenomena [

184,

185,

186,

187,

188]. The patterns observed suggest what might be termed ‘Educational Modality Fluency’—a proposed construct reflecting students’ apparent ability to navigate and evaluate diverse learning environments. This concept, however, requires formal operationalization and validation before it can be considered an established contribution. We offer it as an interpretive proposition for future research rather than a direct outcome of the present analysis [

189,

190,

191,

192,

193,

194,

195].

4.9. Toward a Framework for Sustainable Hybrid Education

Drawing on patterns observed in this study, supplemented by the broader literature on distance and hybrid learning, we propose a conceptual framework for sustainable hybrid education (

Figure 2). This framework is offered as a heuristic organizing tool and theoretical contribution rather than an empirically validated model. While specific elements—particularly the centrality of connectivity infrastructure and the importance of modality flexibility—receive support from the current findings, the framework as a whole represents a synthesis awaiting empirical testing. The proposed relationships between the three pillars (technological infrastructure, pedagogical innovation, social presence) and the four outcomes (engagement, satisfaction, learning effectiveness, equity) are theoretically grounded but would require path analysis or structural equation modeling with purpose-designed instruments to establish their validity.

The framework has pointed out three pillars, which are essential to be effective in hybrid learning. The first technological infrastructure pillar not only deals with infrastructure but also with platform development, technology support, and technological literacy. The pedagogical innovation pillar discusses teaching and learning programs, creative assessment designs, and staff development to provide distance learning. The third social presence pillar deals with social presence, social interaction, and sustaining institute identity.

Such pillars ensure that four key outcomes of education are addressed, and those are engagement, satisfaction, learning effectiveness, and equity. However, this model recognizes that all four outcomes interact with each other such that performance in one area can act as a motivator to enhance performance in another area. For instance, satisfaction may be improved by better technological support, and such support can enhance learning effectiveness and overall equity.

The framework also has feedback loops that enable improvement. The information gathered based on the experiences of students, such as satisfaction, engagement, and learning outcomes, can be used to adjust technological, teaching, and social approaches. This iterative process takes into account that what works best may differ depending on subjects, students, and environments, and therefore encourages testing and evolution.

4.10. Limitations

This research faces various limitations that impact its findings and generalizability. The sample size with 477 participants, although offering qualitative insights into what students went through, is not very robust regarding its statistical strength in detecting narrowly defined research findings. The research sampling method, although commensurate with its objective of covering pandemic-related experiences, may at times be vulnerable to bias, with students who overcame distance learning difficulties possibly underrepresented.

The limitations of this design are that it takes a snapshot of attitude at one point in time and does not enable anyone to make causal associations or longitudinal changes. The attitudes of students after experiences may be different from those encountered in transition and may be affected by reflective thinking and reverting to face-to-face teaching after online experiences. Longitudinal research with students at various points over time would be far more enlightening and insightful into attitude changes and development [

196,

197,

198,

199,

200,

201,

202].

The use of self-report measures may pose potential biases such as social desirability bias, recall bias, and personal subjective metaphor interpretation of scale items. Students may provide responses that may be perceived as what is expected and acceptable, and not what ought to be students’ attitudes. The measurement of students’ actual attitudes may be gained by platform analytics and academic performance, which could validate self-report measures [

203,

204,

205,

206,

207,

208,

209].

The specificity of the Greek context, in terms of geographical and cultural parameters, does not allow generalizations concerning other countries’ systems. The unique characteristics and conditions of Greek tertiary institutions may shape trends deviating from those found in other countries. An international comparative study would help identify what can be generalized and what is context-dependent regarding pandemic experience trends worldwide [

210,

211,

212,

213,

214,

215,

216].

The temporal context of data collection (2020–2021) represents an important limitation for contemporary interpretation. Findings reflect attitudes formed during active crisis conditions when face-to-face alternatives were entirely unavailable. Students’ preferences may have shifted substantially as the pandemic receded and in-person options resumed. Additionally, the technological landscape has evolved considerably since data collection, with normalized video conferencing, improved connectivity infrastructure, expanded learning management systems, and emerging AI-assisted learning tools potentially reshaping the distance learning experience. Students entering higher education in 2024–2025 experienced hybrid learning throughout secondary education, creating potentially different baseline competencies and expectations than the 2020–2021 cohort studied here. The findings should therefore be interpreted as documenting attitudes during a specific historical episode of forced technology adoption rather than reflecting current student preferences or predicting future educational trends.

4.11. Future Research Directions

Three priority directions for future research emerge directly from this study’s findings and limitations:

First, longitudinal tracking of hybrid learning adoption is needed. The cross-sectional design captured attitudes at one point during an ongoing crisis. Research following cohorts from pandemic-era learning through post-pandemic hybrid implementations would clarify whether preferences for combined modalities persist when face-to-face options are available, and how initial crisis experiences shape long-term learning behaviors [

217,

218,

219].

Second, infrastructure-outcome pathway analysis is warranted. Connectivity emerged as the strongest predictor, but the mechanisms underlying this relationship remain unclear. Future studies should employ mediation analysis to examine whether connectivity affects outcomes primarily through increased synchronous participation, reduced technical frustration, enhanced access to resources, or improved capacity for peer collaboration—providing actionable targets for institutional investment [

220,

221,

222].

Third, equity-focused investigation of access barriers deserves priority attention. The recognition by 67.9% of students that distance learning poses differential accessibility challenges warrants dedicated investigation. Purposive sampling of underrepresented groups—students who withdrew, those in rural areas, those from low-income backgrounds—would illuminate barriers invisible in convenience samples and inform truly inclusive hybrid system design [

223,

224].

While other directions merit investigation—including faculty development needs, cross-national comparison, and emerging technology integration—these three priorities address the most direct gaps revealed by the current study and would most immediately inform evidence-based policy for hybrid education implementation [

225,

226,

227,

228,

229].

4.12. Temporal Context and Contemporary Relevance

This study captures student experiences during a unique historical moment—the acute phase of mandatory distance learning when face-to-face alternatives were entirely unavailable. While four years have elapsed since data collection, this temporal distance does not diminish the study’s contributions; rather, it positions the findings as baseline documentation of forced technology adoption patterns against which subsequent developments can be compared.

The study’s contemporary relevance operates on multiple levels. First, the strong preference for hybrid modalities (69.8%) documented during the crisis has proven prescient—post-pandemic higher education has indeed moved toward blended formats worldwide, validating students’ vision for educational futures. Second, the infrastructure-satisfaction relationship identified here continues to inform institutional technology investments; connectivity remains a foundational concern even as specific platforms evolve. Third, the finding that demographic variables minimally predicted adaptation success challenges assumptions about digital divides that persist in current policy discussions.

That said, several developments since data collection warrant acknowledgment. The normalization of video conferencing, proliferation of AI-assisted learning tools, and expansion of learning management system capabilities have transformed the technological landscape. Students entering higher education today experienced hybrid learning throughout secondary education, potentially creating different baseline competencies and expectations. Post-pandemic research has documented phenomena such as ‘Zoom fatigue’ and renewed appreciation for in-person interaction that may moderate the enthusiasm for online modalities captured in our data.

We position this study as contributing historical evidence of crisis-induced adaptation rather than prescriptions for current practice. The patterns documented here—rapid adaptation capability, infrastructure centrality, preference for modality flexibility—represent empirical anchors for understanding how the pandemic reshaped educational expectations. Future research should explicitly examine how the ‘pandemic cohort’s’ formative experiences compare with students who entered higher education after restrictions ended.

5. Conclusions

The present research, focusing on students’ personal experiences with the transition to distance learning due to the COVID-19 crisis, underlines profound shifts in attitudes and expectations towards education. Greek higher education students emerged as surprisingly flexible and accommodating with regard to emergency remote learning, with students generally displaying positive attitudes towards distance learning despite inadequacies in preparation.

The ultimate selection of hybrid models of learning is, therefore, the most revolutionary aspect of this research. Modern students no longer consider online and traditional learning as alternative forms of education, but rather as interrelated parts of comprehensive learning processes. The insight and sophistication of students’ attitudes towards hybrid forms of learning illustrate revolutionary changes in what students can and must achieve.

Quality of infrastructure, specifically internet connectivity, was found to be the strongest determining factor in favor of having enjoyable distance learning experiences, irrespective of one’s personal demographics, including one’s age, gender, and level of education. The far-reaching implication of this outcome is that if and when technology-related disparities are addressed, it may be feasible to achieve comparable outcomes regardless of individual performance. The absence of individual influence in determining success implies that distance learning-related difficulties are not individual issues.

The fast pace at which adaptation was seen, with students achieving proficiency on the platform in a matter of days, shows that technological issues can be overcome if sufficient support is present. The realization by students that distance technology creates inequities based on resource availability shows advanced understanding not only of technology’s capabilities but also its limitations in providing equitable outcomes. This shows that there is a mature understanding of technology’s potential and limitations.

The intricate attitude towards the future of education is a reflection of rather nuanced thinking regarding technology and its role in teaching. The students’ desire to see technology-enabled distance learning displace traditional teaching, contrasted with their desire to see teaching and learning conducted face to face and combined with technology, reveals that students understand that there is irreplaceable value in some aspects of traditional teaching by means of teaching and learning that cannot be replicated in technology-enabled distance environments.

The framework that has emerged with respect to sustainable hybrid forms of education has provided strategic guidance for post-pandemic change. Implementation of such change can be facilitated by nurturing and sustaining interest in technology infrastructure, innovative approaches to learning, and social presence. Instead of regarding each one of these as discrete, unrelated efforts, this framework has encouraged their integration to support technology-mediated learning while protecting traditional forms of education.

Critical practice considerations include infrastructure as the cornerstone of equity, redefinition of pedagogical approaches through comprehensive faculty development, and redefinition of support services in distributed learning environments. The crisis has brought to light some deficits, particularly those concerning mental health and social connections, and redefinition of approaches in hybrid environments is warranted. Assessment and feedback need thorough redefinition with new approaches that capitalize on technology while preserving academic integrity and authentic assessment.

The contribution of this research lies in theoretically grounded findings, which demonstrate that crisis-induced technology adoption diverges widely from voluntary technology adoption trends. The Educational Modality Fluency concept represents an entirely new type of competency, one that encompasses not only technological proficiency but also metacognition regarding each type of modality’s contribution to determining specified learning outcomes. The new model not only goes beyond technology adoption but also addresses technology usage determined by type and context.

The pandemic has proven that change in education is achievable if need arises. The next step, however, is to ensure that this energy is channeled towards deliberate and research-backed innovation that benefits students broadly. This can be achieved by recognizing that technology is not an end but a means to achieve better outcomes by leveraging its potential with effective teaching approaches and interaction.

Moving into the future, if hybrid forms of education are to be sustainable, research and experimentation, and an open-minded attitude towards traditional norms, will be needed. The findings in this series of student experiences can be used to inform post-pandemic realities that post-secondary education will face. The overriding theme among students has been their need to have choices while still maintaining traditional values.

It is important to acknowledge the temporal positioning of this study. The findings document a specific historical moment in educational transformation—the acute phase of mandatory distance learning when traditional alternatives were unavailable. The patterns observed should be read as evidence of what was possible and what students preferred under crisis conditions, providing empirical grounding for the hybrid educational models that have since become institutionalized. As higher education continues to evolve beyond the pandemic, periodic reassessment of student preferences and experiences will be necessary to ensure that post-pandemic hybrid designs remain responsive to changing needs, technological possibilities, and generational expectations.

Thus, this research shows that, in spite of the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, COVID-19 has precipitated innovations in education and unlocked new approaches to learning and teaching. The enthusiasm for online learning and advanced preferences for hybrid approaches suggest that there is a readiness to move towards an evolution of learning and teaching in support of hybrid learning and teaching approaches. The transition towards hybrid learning and teaching approaches has started and must move forwards with innovations and developments in infrastructure and learning and teaching systems.