1. Introduction

The systematic role played by digital platforms, and the underlying algorithmic systems and datafication processes, in the construction of everyday experience and in the organization of social life is a multifaceted issue that social researchers have attempted to address in various forms.

Several contributions have conducted macro-structural analyses of the functioning of digital platforms, highlighting the role of data extraction [

1], the colonialist conditions imposed on users [

2], and issues related to algorithmic discrimination [

3,

4]. The socio-technical character of these dynamics has been scrutinised by authors who focused on the organisational, technical and decision-making practices that contribute to algorithmic production at the meso-level [

5,

6], while other scholars in several research areas, ranging from audience research [

7], communication studies [

8], critical algorithm studies [

9], and human–machine interaction [

10], have focused on users’ agential activities at the micro-level. Although findings from different studies showed ambivalences, negotiations and tensions [

11,

12,

13], a frequent trait of everyday digital experience is users’ normalization of datafication processes. In this regard, the apologetic and ideology-laden narratives surrounding metrification, datafication, and computation have become deeply embedded into daily practices [

14], contributing to the framing of data-driven logics as taken-for-granted features of online activities [

8]. Furthermore, these narratives nurture neoliberal forms of individualism and resignation [

8,

15], fostering the consolidation of hegemonic power arrangements [

16].

To address the overwhelming power of platforms and the implications of datafication, over the past two decades, a range of research areas has underscored the importance of implementing educational initiatives aimed at fostering critical literacy around the role of data and algorithms in contemporary social life [

14,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Given the absence of a unified, consensual definition of critical literacy, and the coexistence of multiple theoretical and pedagogical frameworks, the term “digital literacies”—in its plural form—has increasingly been used to describe a plethora of different approaches that are multidimensional, contextual, and shaped by various educational models and disciplinary traditions [

20,

21,

22,

23]. In this paper, within the field of critical digital literacies, we present a set of research and educational initiatives that, drawing on Markham’s critical pedagogical approach [

14,

21], aim to nurture critical awareness of digital platforms, enabling individuals to recognise the contexts in which data extraction and algorithmic subsumption occur, to analyse their socio-political implications, and to envision potential strategies for change.

Specifically, this article builds on our previous and ongoing research on youth to explore how research and teaching in digital society can be conducted through methodological techniques that support the analysis of everyday media experiences. To do so, we discuss four empirical case studies: (i) the use of autoethnographic diaries; (ii) the constitution of youth juries; (iii) the development of a critical digital literacy educational manual; (iv) the implementation of interactive workshops. Rather than presenting the results of these studies, which are the focus of other works [

16], our interest lies in using this set of cases to offer a practical, multi-level approach for researchers and educators, showing how critical awareness can be cultivated through various initiatives that address critical digital literacy across different levels. In particular, we contend that a key element in this process is the intertwinement of three foundational elements shared by these interventions, i.e., a critical theory stance, a qualitative orientation, and the cultivation of situated knowledge. By the term “critical theory stance”, we refer to the application and “soft-peddling” of the principles of critical theory, as suggested by Markham [

14], to scrutinize tacit power asymmetries and ideological structures embedded in everyday digital experiences. Then, by qualitative orientation, we understand positioning individuals as qualitative researchers of their own datafied activities, using reflexive methods to analyse in-depth the construction of meaning in algorithmic environments and to challenge the following quantification and reduction in social life [

14]. Finally, cultivating situated knowledge favours a context-sensitive analysis of one’s own digital routines within particular socio-cultural and temporal environments.

While technological innovation, and the narratives and hype that follow it, easily render words and definitions obsolete, we contend that the combination of these three components allows the integration of work done in relation to different interrelated technological artifacts—e.g., media, algorithmic, or (big) data literacy. This promotes an approach to critical digital literacies that aim to encourage forms of collective engagement, contesting the dominant neoliberal paradigm which promotes resigned and individualistic stances regarding contemporary digital life. Thus, our contribution lies in synthesising these elements into a coherent approach and providing empirical examples of their application. By doing so, this article offers a fruitful path to put the theoretical principles of critical pedagogy into concrete practices that can be adopted by researchers, teachers and practitioners to help individuals examine and resist the extractive and asymmetrical power dynamics of digital platforms.

The article is structured as follows. The first section examines different critical pedagogies in relation to the digital realm. Then, we advance a critique of hyper-individualistic and uncritical perspectives on digital well-being, highlighting the need for forms of critical digital literacy challenging resignation to extractive platform practices. The following section presents four pedagogical initiatives applicable as resources for researchers, educators and practitioners. Finally, the potential of critical, qualitative and situated initiatives is discussed in detail.

2. Critical Pedagogies in the Digital Age

As digital technologies become increasingly embedded in everyday life [

12], the necessity of promoting digital literacies is recognized by researchers and policy agendas alike. Literacy is often narrowly understood as a set of functional skills, such as accessing and navigating the Internet, using various platforms, or utilizing digital tools to share, search for, and create content [

22]. In this context, public policy often emphasizes issues of e-safety and technical capacities imagined to be essential in future labour markets [

23]. Several contributions have argued against this reductionist functional view, advocating for forms of “critical” digital literacy that recognise knowledge of the ideological and political social dynamics shaping technological production and critical attitudes as essential dimensions [

14,

24].

Within this scenario, several concepts have been mobilized in order to refer to the set of skills, knowledge, and attitudes citizens should be equipped with so as to engage critically with a deeply datafied society [

25]. For example, critical scholarly work has centred concepts such as big data literacy [

26,

27,

28] artificial intelligence literacy [

29,

30,

31], algorithmic literacy [

32], among others. Overall, a lack of a consensual definition of what “digital literacy” is coexists with different approaches, each placing distinct emphasis on the forms of knowledge and skills necessary to participate in a digitalized society [

23,

24]. In this sense, the use of the plural term “literacies” has been considered more accurate to address the diverse educational approaches and strategies directed at preparing citizens to critically engage with digital technologies [

20,

22].

A key framework for the scholarly work done within the field of critical digital literacies is critical pedagogy. Building on Paulo Freire’s [

33] work, critical pedagogies consider the process of

conscientização (critical consciousness raising) as a vital part of becoming literate, recognizing that literacies are inseparable from contextual political, social, and cultural values, and, therefore, are never neutral [

22,

34,

35]. Within the context of digital technologies, several authors—such as Markham [

14], D’Ignazio and Bharghava [

27], Stornaiuolo [

36] and Pangrazio and Selwyn [

19]—have emphasized how the process of becoming critically conscious allows individuals to recognize, understand, and act upon ideological systems of power and control that permeate media relationships. This implies making sense of one’s digital experience, situating it in broader historical, political, and cultural structures.

Adapting the critical pedagogy framework toward the field of critical digital literacies, Annette Markham’s [

14,

21] work connects critical pedagogy to critical theory concerning datafication processes. Specifically, Markham deliberately starts from Gramsci, Freire, and the critical theory of the Frankfurt School to propose a pedagogical model designed to promote critical data and algorithm literacy [

37]. To do so, in her manifesto, Markham [

14] (p. 755) contends that the goal of her critical pedagogy is to make individuals “autoethnographers of their own digital lives,” i.e., to adopt diverse forms of intervention at both micro and macro levels to help people analyse their own online activities, the underlying datafication processes, and the context and ways in which they occur.

A specific focus on datafication is shared by key contributions published by authors such as Acker, Bowler, Pangrazio, Sefton-Green, and Selwyn [

19,

24,

38,

39]. Their works are foundational to the field of critical data literacies and share the common goal of developing strategies to identify data in context, understand their implications, and relate to them.

Another significant network of researchers in this regard is the Critical Big Data and Algorithmic Literacy Network, which aims to promote interdisciplinary dialogue on the same topics and build a database of teaching materials. Some works emerging from this network, such as the ones by Carmi and Yates [

40] or Sander [

17,

41], can be seen as practices directed at promoting forms of critical data literacy among students and citizens through the combination of theory and action. Moreover, a strand of research that has seen a dramatic development in recent years is that of critical edtech studies [

18,

42]. On the one hand, these contributions aim to analyse the technological devices used in the educational sector [

43]; on the other hand, they also focus on how these technologies are designed and their socio-political implications [

44].

In this scenario, we thus acknowledge the existence of multiple digital literacies, with a multidimensional character, situated in distinct socio-cultural contexts, and grounded in diverse disciplinary traditions. Furthermore, we highlight the importance of the contextual and critical dimensions embedded within these digital literacies, which are crucial for interrogating the power dynamics and socio-political implications of computational systems. Building on this framework, our contribution is situated within the field of critical digital literacies [

20,

23], addressing key issues associated with contemporary practices involving algorithmic media—namely, well-being, individualism and resignation—which will be further explored in the next section.

3. Literacy and the Neoliberal Burden: Well-Being, Individualism and Resignation

While the aforementioned scholarly work recognizes the value of critical pedagogical approaches, much discourse around digital media still tends to adopt hyper-individualistic and often uncritical perspectives. Indeed, both within scientific work and in public discourse, debates regarding the potential negative implications of the ubiquitous presence of digital media are often framed in a pathological perspective, mobilizing concepts of digital addiction, technostress, or social media fatigue [

45,

46,

47]. Although we recognise the relevance of these debates, these approaches frequently overlook or devalue how structural aspects and power relations permeate digital environments [

48,

49].

Similarly, scholarly and public discourses about digital well-being [

46,

50,

51] or digital wellness [

52,

53], centres individuals’ behaviour and responsibility [

54], emphasizing self-control as the main answer to promote digital health, and reinforcing a logic of self-optimization, self-improvement and individual accountability [

55,

56,

57]. This reflects a neoliberal vision of well-being, failing to consider “unequal social determinants of health” and how one’s choices are “prestructured by contingent social, financial, and environmental circumstances” [

58] (p. 3835).

These perspectives echo tech companies’ approaches to well-being, based on user accountability, overlooking deeper criticisms of their business models [

47]. As described by Beattie and Daubs [

54] (p. 7), “digital well-being says nothing about the concentration of power via a few technology conglomerates, the exploitation of cheap labour or scarce minerals in manufacturing phones, and the health of tech workers who perform undesirable labour such as moderating online hate speech”. Such dynamics mirror what Dennis [

59] terms the “McDonald’s model”, which puts the responsibility on users for the consumption of a potentially harmful product—whether it be chicken nuggets or posts on social media—thereby absolving producers of responsibility, avoiding regulation and public condemnation. By anchoring the discussion on digital well-being around individual usage and choices, researchers and practitioners risk to ignore the political, ideological and economic structures underlying technological adoption [

60].

Moreover, the weight and burden of self-managing digital well-being affect citizens. Indeed, behaviours that characterize collective problems (e.g., the difficulty of managing time spent online), associated with the very design of digital platforms, which serve their business models, result being treated as individual issues [

61]. This situation can lead to feelings of guilt or shame when the user feels like they are “failing” in exercising their agency [

62,

63]. In parallel, individuals experience increasing pressure to master digital literacies, self-regulate their online habits, and serve as a “good example” for others around them (especially children) [

57].

In this scenario, it is common for individuals “to blame themselves for being lured and distracted by technologies that are designed to captivate users in order for companies to capitalize on the data they produce” [

16] (p. 98). However, users are left to their own devices in navigating spaces that privilege commercial benefit, in many instances at the expense of users’ well-being [

64]. This responsibility may be particularly challenging—and unfair—when it comes to children and adolescents, who often struggle to grasp the consequences of datafication for issues of privacy, freedom, and social justice [

65,

66].

Another key element in this regard is resignation. Empirical research shows that young people often share apathy and a sense of powerlessness regarding the datafication of their own lives and the functioning of digital environments [

66]. This posture of indifference is not, however, a necessary result of ignorance or disinterest; on the contrary, it is often the result of feelings that digital technologies are impossible to resist or fully avoid [

15,

16,

67]. In this context, young people tend to trivialize their digital privacy, considering themselves powerless and incapable to challenge, resist, or change digital structures [

66,

68].

These attitudes echo what Draper and Turow [

15] (p. 1) call digital resignation, that is, a social political phenomenon “produced when people desire to control the information digital entities have about them but feel unable to do so”. While Draper and Turow’s [

15] (p. 4) work centres, specifically, resignation regarding issues of privacy and surveillance, the same framework might be expanded to all instances where structural issues related to digital technologies “causes people to despair about their ability to guide their futures”. Corporations actively cultivate this cynicism by individualising users’ frustrations, moving them away from collective action, anger, or resistance and towards a disempowered and resigned posture.

In this context, several authors have called for research dedicated to understanding how structural aspects of digital environments impact users’ well-being, health, and daily practices [

45,

46,

51,

58,

59]. Furthermore, there has been a growing call for pedagogical activities aimed at contrasting forms of resignation and engaging with the structural dimensions of digital platforms [

37]. The Data Detox Kit [

69]— an educational resource created by Tactical Tech—exemplifies how the bridge between individual struggles and constitutional aspects of digital platforms can be explored and critically approached by users. The resource suggests that the reader reflects beyond individual responsibility regarding smartphone “overuse”, learning to identify persuasive design strategies (e.g., winning streaks, autoplay) and resist them both individually and collectively.

Although critical pedagogies in relation to digital literacies are still a relatively “niche” field, we concur that this framework can be a particularly fitting approach to address the gaps and fragilities of the present hyper-individualistic approaches. Specifically, we consider their retrieval of a Freireian pedagogical framework particularly valuable in considering education as a practice of freedom that rejects the individual as a self-sufficient subject “abstract, isolated, independent, and unattached to the world” [

33] (p. 81), an idea opposed to dialogue and the following critical understanding of the world. Education—and social transformations derived from critical consciousness—are always collective endeavours, people educate each other in communion, in a world-mediated mutual process. These premises might help to answer calls such as the one made by Docherty [

58] (p. 3829), who writes: “we must explore alternative, more relational, visions of digital well-being that do not so rigidly turn on the moralized pivots of neoliberal self-care and personal technological autonomy”. Within a critical pedagogical framework, critical consciousness raising is presented as a fundamental step towards liberating and revolutionary political action. In this context, critical digital literacies—based upon collaboration, collective political action, and dialogue—may help us to shift the focus from individual actions and behaviours, imagining collective paths of resistance and transformation.

4. Pedagogical Initiatives in a Datafied Society

In this section, we discuss four pedagogical initiatives aimed at fostering critical data and algorithm literacy, namely, (i) the use of autoethnographic diaries; (ii) the constitution of youth juries; (iii) the development of a critical digital literacy educational manual; (iv) the implementation of interactive workshops. Rather than presenting empirical findings, our aim is to detail the design and the methodological and theoretical underpinnings of these initiatives, highlighting their pedagogical potential and adaptability for researchers, educators, and practitioners across different levels.

4.1. Autoethnographic Diaries

The first initiative discussed is the use of autoethnographic diaries with students, which focus on individual practices and subjective experiences. Specifically, the goal of guided autoethnography is to help participants narratively reconstruct and analyse their routine digital experiences, in order to defamiliarize everyday situations with algorithmic media, examine the applied interpretive frames and the emerging meaning-making processes [

37]. The use of autoethnographic diaries can be considered a form of action-research [

14,

70], pursuing both a research and pedagogical goal. Indeed, the researcher can collect micro-level, first-hand, self-produced narratives on individuals’ relationships with digital platforms, while simultaneously promoting in the participants forms of critical consciousness about the socio-technical infrastructures propaedeutic to critical data literacy [

71].

The theoretical foundations of this initiative lie in the critical pedagogy framework elaborated by Annette Markham [

14,

21] and in her “multimethod pedagogical design” [

37] that aims to train individuals to conduct self-oriented analyses of their own experiences and develop reflexivity regarding the everyday practices and contexts through which datafication processes unfold and the following implications.

Drawing on this framework and on previous research experiences by Markham and colleagues [

14,

72,

73] and with other researchers [

74,

75], Pronzato developed a week-long diary structure, written in Italian, in the form of an autoethnographic challenge. Specifically, the structure consists of seven prompts and an algorithmic media fast exercise. Thus, each day for seven days, participants are required to complete a creative task based on prompts that composed the structure of the autoethnographic challenge. All of these prompts are adaptations of others used in previous research [

14,

73] and inspired by different tenets taken from ethnography, autoethnography, phenomenology, design thinking, and critical theory. More precisely, in this autoethnographic challenge, students are asked to complete the following tasks (see

Table 1).

Pronzato adopted this diary structure in his doctoral studies, involving 40 voluntarily recruited undergraduate students (aged 20 to 22), and then in subsequent research endeavours, with the aim to investigate how young individuals interpret and relate with algorithmic media in their everyday life. After the dissemination and publication of the results produced by Pronzato [

16], Kubrusly used this diary structure as a starting point for her ongoing doctoral research project focused on young people, aged 12 to 14, in Portugal. Specifically, the research goal is to understand how adolescents understand and manage their digital well-being. In this context, autoethnographic diaries are combined with other methodological techniques to centre young participants’ experiences and allow them to co-create recommendations to promote their digital well-being. Participants are part of a convenience sample from two schools where the field work is conducted, with informed and voluntary consent being required from both participants and one legal guardian.

The diary, created in Portuguese, is intended to be used over a period of seven consecutive days (see

Table 2). Each of the seven days in the diary is structured in two parts. First, a “digital well-being thermometer,” i.e., a short qualitative questionnaire repeated daily to assess how the diarist feels, their online activities and how they impacted their well-being. Following the thermometer questionnaire, each day is dedicated to a specific thematic dimension related to the issue of digital well-being.

Overall, the use of autoethnographic diaries aims to enable students to wield inductive qualitative research methods in order to conduct personal empirical analysis of their own relationships with digital media. Through the prompts of the autoethnographic challenge, participants can observe themselves “from a distance,” defamiliarize their own media activities, and scrutinise all those microscopic moments in which the social power of the platforms is exercised. Moreover, the technique allows participants to analyse their everyday digital lives without evaluation and choosing for themselves which moments to question [

80]. In this sense, this intervention can be considered a form of intervention aimed at increasing awareness towards the hegemonic power of tech owners, and developing critical digital literacy.

4.2. Youth Juries

In the second initiative, there is a shift from the level of analysis of individual practices and subjective experience to the collective construction of knowledge and deliberation regarding the implications of digital media. In the context of Kubrusly’s previously mentioned PhD project, youth juries are proposed as a methodological technique to position young participants as experts in their own lived experiences while, simultaneously, stimulating reflections on how these experiences are traversed by broader sociocultural dynamics.

To understand how adolescents manage, imagine, and conceptualize their digital well-being, this project proposes an instrumental case study in two Portuguese schools in the Lisbon metropolitan area. Theoretically, a holistic and situated framework of individual digital well-being—broadly defined as an experience that reflects a balanced relationship with digital technologies in contexts increasingly permeated by them—is adopted.

Youth juries are group discussions, similar to focus groups; however, their ultimate goal is for participants to reach a series of recommendations or decisions on a given topic [

81]. In this sense, juries aim to provide spaces where young people are positioned as agents and active citizens, including them in decision-making processes that concern their lives, and allowing for a “bottom-up” dynamic in formulating public agendas and policies [

82,

83]. During a jury, participants may present their opinions, explain the factors that shape their way of thinking, and, potentially, engage with other arguments and perspectives presented by peers throughout the jury. The role of the facilitator, in this sense, is fundamental in securing an inclusive discussion, without interfering in the tone and direction set by participants, while carefully managing relational dynamics to maintain a safe, horizontal, and equitable space for expression [

82].

The use of the word “jury” is intentional, seeking to evoke a sense of responsibility and empowerment on the part of the participants [

81]. Just like in any jury, participants are invited to engage in a process of deliberation—i.e., “a talk-based process to reach mutually acceptable solutions to social problems through an exchange of and reflection on stories, experiences, opinions, argumentation and persuasion” [

83] (p. 2). The space for voicing their views—in an open-minded and flexible style of communication—accommodates the process of constructing and expressing opinions, which is often “confusing”, “messy” and non-linear [

82].

Several studies have successfully employed the youth jury method, acknowledging this technique as a useful strategy to promote participants’ critical digital literacy [

81,

83]. The jury deliberation dynamic increases the sense of confidence and self-efficacy among young participants who are able to not only develop critical awareness about how hegemonic powers shape digital media, but engage in collective problem-solving, discussing future strategies of social transformation.

Within the project discussed in this section on Portuguese adolescents, the youth jury process answers to two central goals. First, it asks participants to collaborate in the process of data analysis from previous data collection—in this case, an online questionnaire answered by themselves and fellow peers in their school. Second, it invites them to create recommendations to promote their own digital well-being with different audiences in mind, such as peers, family, teachers, local government, international entities, and big tech companies.

The jury is organized in five moments. First, a simple ice-breaker activity where participants introduce themselves and answer two questions: What do adults usually misunderstand about young people’s digital lives? And, what would you change in the digital world, if you could? The second step is to share the provisional results of the online questionnaire and ask them to interpret the results, highlighting what they believe might be surprising, worrying, or important about them. They will be invited to reflect upon how they would promote digital well-being among respondents of the questionnaire.

In the third step, jurors will engage with two vignettes about teenagers’ experiences online. Youth juries often use vignettes, that is, fictional or hypothetical scenarios, to stimulate a discussion about values and beliefs related to the issues at hand. Vignettes are particularly effective for engaging groups of young people, especially when it comes to sensitive topics [

82]. In the context of youth juries, vignettes usually serve the dual purpose of encouraging collective reflections among participants, based on a common starting point [

81], and of allowing participants to distance themselves from the situations being discussed, since it is often easier to discuss abstract characters than one’s frustrations and experiences, understanding them as part of a broader political and social scenario [

83]. Vignettes—paired with deliberation—can propose a fruitful balance between playfulness and critical reflection, creating an experience that is “both judicious and enjoyable” [

82] (p. 2).

In this study, participants will be asked about how they relate the vignettes to their experiences and to the topic of digital well-being. A key issue to be discussed during this step is responsibility. For instance, if one of the characters is having a hard time disconnecting from social media or is being fed with conspiracy theories, who is responsible? Participants will be encouraged to reflect upon how diverse social actors and entities—the characters themselves, their parents, their schools, the creators of the digital platforms, etc.—are intertwined with the struggles faced by the character to manage their digital well-being.

The fourth step is dedicated to the creation of recommendations to promote young people’s (the same age as the jurors) digital well-being. Jurors are challenged to think about recommendations with different target audiences in mind (e.g., peers, families, school, government, tech companies…). The fifth and final step is a debriefing moment, reflecting upon how this experience impacted jurors, as well as how the format of the jury could be improved in the future.

Ultimately, the youth jury technique combines the possibility of promoting participants’ critical consciousness regarding their own digital lives with an intentional effort of centering youth’s voices and rights [

82]. This allows for a relational process of knowledge production where the process of deliberation allows for participants to emerge from a “culture of silence”, often imposed by disparities of power between young people and adults [

83].

4.3. A Critical Data Literacy Educational Manual

The third case study shows the production of educational content and its appropriation in a pedagogical project with undergraduate students. Acknowledging a gap in resources about big data literacy available in Portuguese, Kubrusly dedicated her master’s thesis [

84] to the creation of a manual to promote the big data literacy of adolescents aged 14 to 17. To map the scientific literature on youth’s big data literacy, in February 2023, an integrative review was conducted to understand how big data literacy is conceptualized and operationalized, mapping theoretical frameworks and other concepts associated with it [

25]. Then, a scoping review was dedicated to empirical research done on children, adolescents, and young adults [

66].

Regarding the concept of big data literacy, critical and qualitative approaches were predominant. The scoping review revealed that “mythological” conceptions of (big) data [

85]—that consider data as neutral and truthful units of knowledge—are still prevalent among young people. Finally, while educational initiatives can improve their big data literacy, they struggled to overcome feelings of resignation regarding the datafication of their lives, which was regularly understood as unavoidable and inescapable.

Next, an analysis of existing resources on the topic of big data literacy was conducted. Two main sources were consulted, namely, the Critical Big Data and Algorithmic Literacy Network database and Ina Sander’s critically commented guide to data literacy tools [

86].

Three educational resources were selected, namely, the

Digital Defense Playbook [

87], also utilized in Pronzato’s workshop described below; Onuoha and Nucera’s

A People’s Guide to AI [

88], which aims to inspire reflection about and usage of emergent technologies as a tool of liberation; the

My Data and Privacy Online: A Toolkit for Young People [

89] created as part of an LSE research project on children’s digital lives.

Resources were analysed with the goal of identifying themes explored and pedagogical strategies employed. Notably, resources covered multiple topics related to online data ecosystems; however, the mythological aspects of big data were seldom addressed. Among the most used pedagogical strategies were questions, activities, and proposed reflections on personal experiences in digital spaces. The use of hypothetical scenarios (e.g., role playing as “data agents”) was often used to teach critical and practical skills related to working with data or to stimulate readers’ imagination regarding technologies’ potential impacts in their futures.

Stemming from this work, big data’s mythology, the challenges of working with data, and the limitations of data-based technologies were considered central to the creation of the educational manual. The manual—titled Who Cares About Big Data? An Educational Manual for Adolescents—is divided into three main thematic chapters. The first one is dedicated to defining (big) data, exemplifying how they permeate our daily lives, and discussing big data’s mythological aspects. The second chapter explores issues of digital privacy and its relation to online commercial ecosystems. Finally, the third chapter is dedicated to technologies closely related to big data, such as algorithms and artificial intelligence.

The manual took the format of a 70-page PDF file, combining exposition through text and illustrations with interactive activities, a deliberate strategy to engage the reader with the content (

Figure 1). Activities included questions about readers’ lives and everyday experiences, quizzes, spaces for drawing, hypothetical scenarios for critical data analysis, and imaginative exercises about the future (e.g., creating a new social media platform and thinking about its privacy policy).

Reflecting on the challenge of moving the reader away from an apathetic view of the datafication of their own lives, an intentional effort was made to balance risks and opportunities related to (big) data-based technologies, using concrete examples. Furthermore, the final activity of chapter three is dedicated to “science fiction” exercise where the reader is selected to participate in a worldwide committee responsible for creating policies related to datafication processes. By putting the reader in a hypothetical position of power, where they can decide about the usage of AI in key social contexts or create recommendations for government agencies, educational institutions, technology companies, and fellow citizens, the manual reminds the reader of their ideals and visions for the present and future, potentially inspiring them to act towards them.

After the pilot version of the manual was ready, Kubrusly—together with other researchers (see acknowledgments)—implemented a pedagogical project in a Media Education and Information Management undergraduate course at the Polytechnic University of Setúbal in Portugal. This initiative was inspired by action-research paradigms [

90]. First, undergraduate students were introduced to the topic of big data literacy, its relevance for their lives and to the educational manual. The class was then divided into eight groups, each one dedicated to one of the manual’s key themes: (i) Data and self-surveillance; (ii) Challenges of data analysis; (iii) Digital footprint and online commercial ecosystems; (iv) Digital privacy; (v) Big data and AI.

Each group created an educational workshop, inspired by the activities of the manual, and implemented it with high schoolers, the target group for the manual. Most groups conducted their workshops in classroom settings. Informed and voluntary consent was obtained for all participating undergraduate students. After the implementation of the workshops, each group wrote a research report detailing the experience. A total of 42 undergrad students and 168 high schoolers participated in this pedagogical initiative. While the undergraduate students were invited to collect data on high schoolers’ big data literacy, the core goal of this endeavour was not to conduct an empirical research, but more so to promote the critical awareness of involved students regarding the impacts of datafication, and to develop research and teaching skills for the undergraduates.

Overall, undergraduate students reported having enjoyed this experience, describing feeling empowered and proud of occupying the roles of educators and researchers, which sustained their motivation and compromise with this time and labour-intensive pedagogical project. The main negative aspects were related to time restraints to organize and implement the workshops. The age proximity between the first-semester undergraduate students and the high schoolers who participated facilitated a peer-to-peer learning environment, where both groups shared personal experiences and learned from each other. However, the lack of training in scientific writing and methodology significantly impacted the undergraduate students’ ability to write rigorous research reports.

According to field notes, topics related to big data literacy were unknown to most high school students, who were often curious to learn more. In the workshops, examples closely related to their daily lives were useful to grab attention and keep participants engaged. Most students also said they were uncomfortable with their privacy being violated, by ill-intended individuals (e.g., hackers) and public or private entities (e.g., tech companies). Both high school and undergraduate students often focused on the “dangers” of the internet, notably individual risks without a structural and more critical view of these issues.

Although undergraduate students enjoyed the autonomy to create the workshops and be creative, the lack of uniformity among workshops was challenging, resulting in a fragmented research experience. The struggle to secure informed and voluntary consent from all 168 high school participants—mostly due to time constraints and issues with field work organization—also negatively impacted the possibility of broad dissemination of research results regarding high schoolers’ big data literacy. Nonetheless, this was a stimulating pedagogical experience that was highly successful in engaging undergraduate students in a hands-on process of teaching and learning.

4.4. Interactive Workshops

The last case study addresses an additional level of analysis, focusing on situated embodied learning and collective engagement in classroom settings. The classroom has historically been a key environment in which to learn and scrutinise social and technological dynamics. This section discusses a type of initiative that aims to make the classroom a more interactive learning environment that can be propaedeutic to the promotion of critical data and algorithm literacy. Specifically, based on five activities held by Pronzato in spring 2023 and 2024 at IULM University (Milan, Italy) and University of Siena (Italy) two interactive workshop models are proposed to help students examine the ecosystems in which digital platforms are produced and adopted, as well as their implications. Both workshops discussed in this section were prepared and conducted in Italian.

The first workshop model is based on the

Digital Defense Playbook [

87], published by Our Data Bodies (ODB). ODB is a U.S.-based nonprofit association, based in the marginalized suburbs of the cities of Charlotte (North Carolina), Detroit (Michigan), and Los Angeles (California). ODB aims to defend human rights and social justice in relation to surveillance and datafication processes, thereby focusing on how data are collected from communities that are already marginalized by ethnicity, class, gender, sexual identity and orientation, and then stored and used by public and private actors, potentially amplifying pre-existing inequalities and forms of discrimination [

3,

4]. ODB produced a playbook with several educational activities aimed at making people more aware of datafication processes and the potential of forms of community organizing. Three interventions organized by Pronzato in spring 2023 were based on this resource. Specifically, he adapted in Italian and expanded the workshop “Your Data Body” [

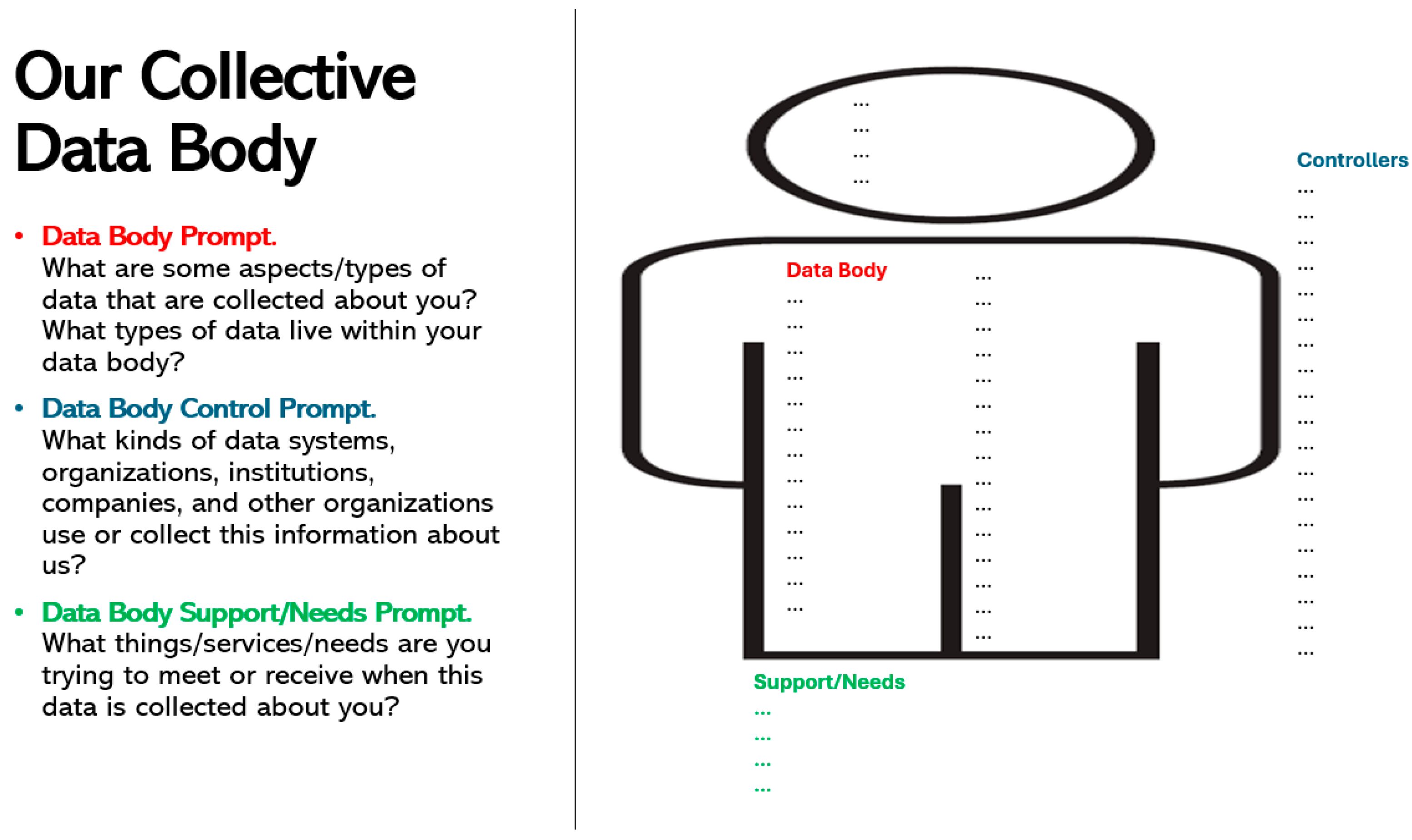

87]—an activity designed to help participants explore their digital selves by reflecting on how physical characteristics, behaviours, and personal needs are transformed into data by both public and private entities, and to consider potential forms of resistance. While the original workshop focused on surveillance activities enacted by state actors, Pronzato decided to situate the analysis on datafication processes enacted by private platforms such as social media and streaming services. The workshop includes three exercises, namely, examining various digital platforms to identify the types of data extracted from users, the systems and organizations that collect and manage these data points, and the underlying needs users attempt to fulfil within these datafication processes (see

Figure 2). Then, participants are asked to draw their own data bodies under the surveillance of contemporary public institutions and tech companies, and then to imagine their data bodies free from this surveillance.

Taken together, the activities of this workshop model are an example of how it is possible to make individuals reflect on the datafication processes underlying their everyday activities, thus cultivating forms of critical data literacy and promoting a deeper understanding of the socio-political dimensions of datafication in the classroom.

The second model of workshops is based on the combination of two analytical frameworks: the tool

The algorithmic ecology developed by Stop LAPD Spying and Free Radicals [

91] and the project

Anatomy of an AI System by Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler [

92].

The first tool was developed by the U.S. non-profit organizations Stop LAPD Spying and Free Radicals [

91] as a reaction to the discrimination perpetrated by predictive policing algorithmic software. Their approach aims to decentralize these technologies, examine “the different actors that shape the algorithm,” and understand “whose interests the algorithm serves, with the ultimate goal of dismantling the actors creating algorithmic harm” [

91] (np). In particular, technologies are considered as “designed to operationalize the ideologies of the institutions of power to produce intended community impact.” Within this framework, four layers of analysis are proposed by these two organisations: community impact (which people are impacted by the software programs analysed and how), operationalization (which technical elements of a program and actors legitimize and implement these technologies), institutions (which institutions are involved in and benefit from the platform’s production), and ideologies (the ideological values that underlie the technological artifacts and are perpetuated by it). The ultimate goal is to create an “ecology” of the algorithm.

In the workshop model presented in this paper, the focus of analysis was redirected toward commercial digital platforms embedded in everyday life, adapting the four aforementioned “ecological” layers. Furthermore, three further levels of analysis were incorporated, drawing inspiration from the “topographic” approach proposed by Crawford and Joler [

92]. Specifically, the additional layers introduced were: natural resources (the materials extracted, and energy sources required to operate the platform); labour (the types of work and workers involved in the production of the technology); data (the kinds of information abstracted and collected by the platform) (see

Table 3). The intertwinement of these layers aims to foreground the extractive mechanisms underpinning the development and functioning of digital platforms, particularly in relation to environmental impact, labour conditions, and the appropriation of human activities as data.

In these workshops, participants are invited to work in groups, select a digital platform of their choice, and collaboratively reconstruct its various components. The goal is not to achieve exhaustive analysis, but rather to create an opportunity for critical reflection and awareness of the underlying dynamics. By allowing participants to choose the platform, the activity encourages them to explore the social, cultural, and power relations embedded within the selected ecosystem. This initiative is thus intended to initiate a process of developing critical consciousness about the heterogeneity of computational systems, their function as “information infrastructures” [

93], and the multiple levels at which they can be interrogated.

Overall, the two workshops are examples of how classroom resources can be adapted or developed to work both individually and in groups on the implications of algorithmic media. As needed, different workshops can focus on the abstraction, transformation and extraction of personal activities as data, on the broader ecology or the power relationships underlying platform production and functioning. Then, it should be noted that, while the workshops are not designed with formal assessment tasks, their implementation depends on specific boundary conditions, including sufficient time allocation, facilitation by educators familiar with critical data studies, and institutional flexibility to accommodate participatory, non-evaluative learning formats. In this sense, workshops can be considered as tools aimed at favouring momentary and embodied interactions, which can centre different foundational aspects of a critical approach to digital literacy.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In the previous sections we presented four case studies, from our prior and ongoing research on youth, aimed at implementing forms of critical digital literacy. The goal of the autoethnographic diaries is to foster critical awareness of the functioning and embeddedness of algorithmic media, thereby facilitating processes of narrative reconstruction, defamiliarization and reflection on one’s everyday digital engagements. A more collective approach can be found in youth juries, which position adolescents as active agents and foster critical dialogue around sociocultural dimensions of digital life. By engaging participants in collective discussion and decision-making, in fact, this technique helps young people articulate collective understandings of their digital well-being and recommendations for healthier digital environments. Drawing on an extensive revision of prior literature and practices, the critical data literacy educational manual offers interactive pedagogical content designed to help individuals critically engage with the complexities of datafication. Moreover, it shows how this type of materials can be appropriated and become spaces of empowerment. Finally, the interactive workshops emerge as classroom resources aimed at favouring the analysis of the contexts of digital platforms’ production, adoption and implications.

The case studies engage with critical digital literacy across different levels, i.e., from individual self-reflection (autoethnographic diaries), to collective deliberation (youth juries), to the creation and appropriation of pedagogical materials (educational manual), and to situated, embodied learning in group settings (interactive workshops). Nonetheless, they share three key characteristics, i.e., a critical theory stance, a qualitative orientation, and the cultivation of situated knowledge. We argue that the intertwinement of these three elements provides a starting approach to elaborate and implement initiatives that can put into practice the theoretical principles of critical pedagogy and favour the development of proactive forms of critical digital literacy.

As mentioned earlier, the integration of critical theory principles and notions to digital literacy is a long-standing stance of Markham [

14] (p. 575), who, building on Gramsci and Freire, argues that critical theory “forms the foundation for anything we might call literacy”. Specifically, this standpoint starts from “the idea that there’s something wrong” about everyday online experiences “and works to investigate the who, what, where, when, and how of this wrongness” [

14] (p. 757) that characterise contemporary datafication, automation and algorithmisation processes. Sustained interaction over time with systems governed by rigid procedural frameworks and opaque mechanisms favour the naturalization of value-laden infrastructures as neutral, thus progressively concealing the embedded ideological apparatuses that strategically reproduce asymmetrical power relations through institutionalized processes and arrangements [

8,

94]. In this context, critical theory can allow individuals to scrutinise and move beyond naïve perceptions of technological innovation toward a critical understanding of daily digital engagements [

37].

More specifically, the proposed initiatives follow Markham’s [

14] idea to “soft-peddle” critical theory, i.e., embedding critical concepts through pedagogical practices focused on critique and social change. This approach encourages participants to recognize power asymmetries in the functioning of digital platforms by reflecting on their own experiences, promoting critical awareness without requiring formal and explicit expertise in critical theory.

Then, in a world in which metrification and datafication processes, and automated decision-making, have become a tacit part of everyday life, the second element that we consider foundational in our approach to critical digital literacy is a qualitative orientation. The initiatives we presented share the ontological and epistemological premises of the interpretive methodological framework which underlie the use of qualitative techniques in sociological and anthropological inquiry. In this sense, we concur with Markham [

14] (p. 754) that is necessary to help individuals “become qualitative researchers of their own experience,” and we argue that the use of these methods can favour the analysis of the socio-cultural structures and dynamics that influence technological production and adoption. Specifically, qualitative methods serve a dual purpose. First, the tenets and techniques of ethnography and autoethnography enable individuals to scrutinise in-depth how meaning is constructed in everyday digital activities, the way taken-for-granted practices reproduce patterns, and the ecological networks from which technological artifacts are generated and propagated [

37]. Second, the use of qualitative techniques can be seen as a reaction to the neoliberal imposition of metrics and quantitative understanding of social life through digital media that inevitably simplify human life through opaque forms of categorization [

95,

96]. From this perspective, the development and cultivation of crucial elements of qualitative research, such as reflexivity, embodiment, contingency, subjectivity and empathy [

97], challenges the reductive abstraction and decontextualization of human experience through algorithms and data [

73]. In this sense, putting “meanings into motion” [

98] allows to foreground meaning-making as an active, embodied process, integral to both research and pedagogy, and to shift attention from “data” to the “analysis, interpretation, and representation” [

14] (p. 757) of social life and technological development.

The third element, intertwined with the use of qualitative epistemologies is the cultivation of situated knowledge, which operates on two interconnected levels. At the first level, there is a focus on situated daily routines and relations with embedded and ubiquitous digital technologies [

73]. Interpretations of social life are, in fact, always contextualized within specific socio-cultural environments and moments in time, hence, the proposed initiatives aim to enable individuals to critically analyse and self-reflect on their everyday personal relationships with digital media in a nuanced and context-sensitive manner. Participants can choose which moments of their digital engagements to analyse for themselves, thus fostering contextual awareness of the expansion of the hegemonic power of platforms. At a second level, as non-native English speakers who work in Southern European countries, we frequently have to use resources that are predominantly available only in English. This scarcity raises important questions regarding the purpose, accessibility, and scope of these materials. Although the materials we produced and the participants involved in our projects are mainly from the Global North, we nonetheless find it important to highlight these issues. Indeed, as other contributions have already highlighted in the field of education [

99,

100], it is crucial to invite broader reflections on issues of linguistic inclusion and decolonization of knowledge within digital literacy.

Given these three key elements of our critical digital literacy approach, we argue that the initiatives discussed not only foster critical awareness of one’s platform engagements, but also invite participants to challenge individualism, promoting collective strategies of resistance. By intentionally discussing everyday activities—be it through writing in a diary or reflecting collectively about vignettes in youth juries—participants can distance themselves from their online routines. This process of defamiliarization invites them to think critically about aspects of digital platforms that are often considered “neutral” or “natural”, reflecting on how socio-cultural values, forms of power and ideologies permeate them. Alongside this, participants are also invited to center the issue of responsibility and think about the different powers, groups, and social agents that are responsible for the dynamics underlying their everyday digital practices. These exercises align with the idea that situating one’s individual experiences in relation to structures of power is the first step towards raising one’s voice as “part of a wider project of possibility and empowerment” [

34] (p. 5). Moreover, participants are also prompted to assume responsibility, imagine alternative futures and articulate potential counteractivities. The combination of these different features can challenge the individualization of struggles related to digital experiences and favour a move away from resigned postures and the imagination of more collective paths of resistance.

Then, although the initiatives discussed centre young people, as many others dedicated to digital literacy, we believe that people of all ages could benefit from participating in these pedagogical and research experiences. The issues discussed in this article—digital resignation, a lack of critical consciousness regarding social, political, and cultural power dynamics that permeate digital technologies, and the struggle to transform individual struggles into collective action, among others—are by no means exclusive to youth. On the contrary, adults who are responsible in caring for children and adolescents face increased pressures to be role models for younger generations when it comes to the use of digital media, navigating a complex web of responsibilities, expectations, and moral obligations [

57,

101,

102].

We acknowledge that there also are potential limitations that can be identified to this article. First, we did not conduct semi-structured interviews or post-test surveys after the implementation of the four initiatives as it was beyond our scope to detect measurable outcomes. These action-research practices and interventions, in fact, are “not interested in a long-term evaluation on change, but in the momentary and embodied interaction between researcher and participant” that foster “a spark” [

21] (p. 236) to promote critical awareness. Nonetheless, from a more post-positivist perspective, concerns can arise related to the absence of follow-up surveys, tests and interviews in all the interventions. From the same post-positivist standpoint, another limitation may lie in our reliance on methods such as autoethnographic diaries and youth juries, which depend on participants’ own reflections and narratives [

103], and thus can be considered limited in their scope. While the reliance on self-reported data may be constraining at the research level, we contend that, within an interpretive approach and a critical pedagogy framework, such methods are valuable to foster self-reflexivity and situated understanding, rather than generalised outcomes. Another concern involves the inherent power imbalances embedded in certain methods. Frequently, participants are university students, whose recruitment presents various challenges [

104]. Due to our academic positions, students may selectively reveal or conceal aspects of their experiences. However, our interventions are intentionally designed as action-research and pedagogical initiatives focused on youth [

14]. Thus, as argued by Ling Shi [

70], students partaking in these initiatives should be seen as collaborators whose learning experiences contribute to reflection and knowledge construction, within a collaborative relationship. Finally, our initiatives were implemented in the Global North, and we recognise the necessity to engage people across different social, cultural and linguistic contexts.

Nonetheless, the interventions we presented showed the importance of promoting forms of critical awareness that can be valuable in challenging the individualism and resignation frequently characteristic of contemporary digital life, fostering collective engagement and possibilities for transformative action. Not only as educators, but as researchers engaged with and oriented by the field of critical digital literacies, we must think creatively about methodologies that allow us listen attentively to our participants, centering their voices and experiences, and, ultimately, creating spaces and opportunities for critical consciousness raising.