Group Environment Questionnaire (GEQ): Validation in Mexican University Athletes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Internal Consistency by Factors

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

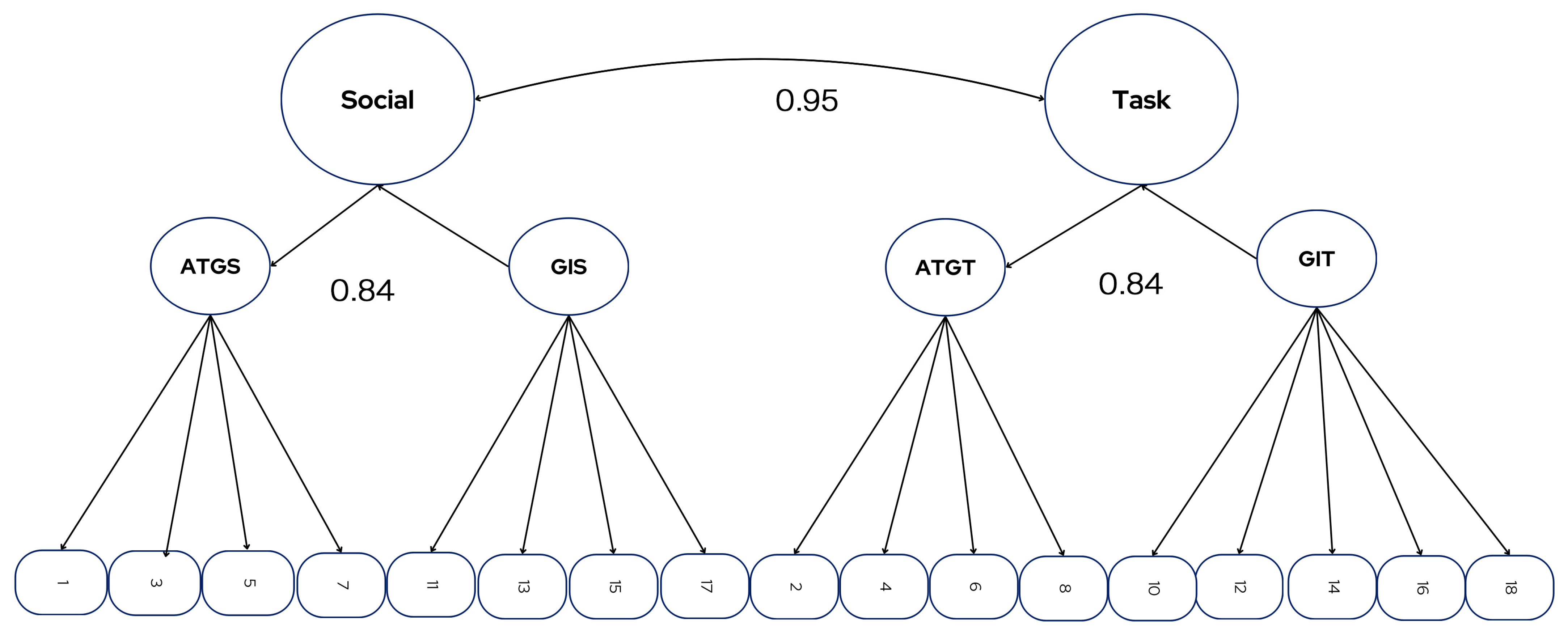

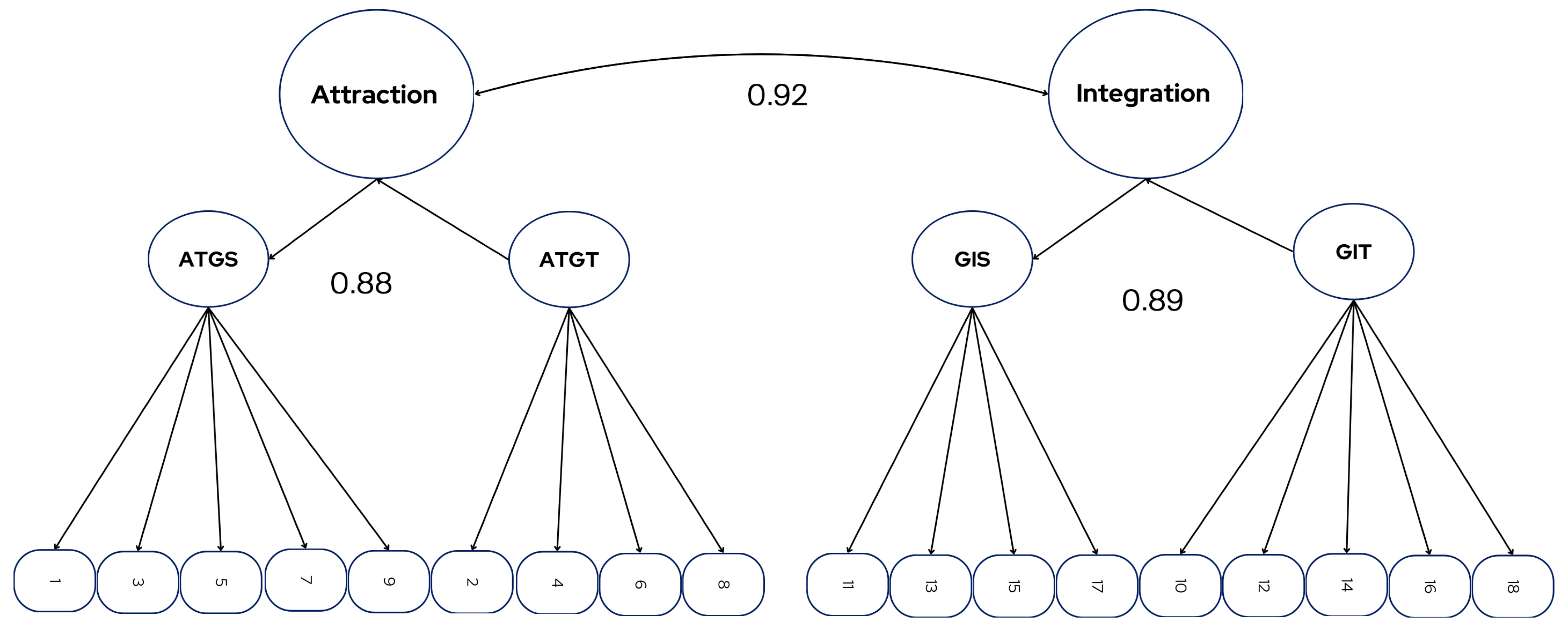

3.4. Bivariate Correlations Between Partial Scales

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GI | Group Integration |

| ATG | Individual Attraction to the Group |

| ATG-T | Individual Attraction to the Group-Task |

| ATG-S | Individual Attraction to the Group-Social |

| GI-S | Group Integration-Social |

| GI-T | Group Integration-Task |

References

- Carron, A.V.; Widmeyer, W.N.; Brawley, L.R. The Measurement of Cohesion in Sports Teams: The Group Environment Questionnaire. Can. J. Sport. Sci. 1989, 14, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Carron, A.V.; Eys, M.A. Group Dynamics in Sport, 4th ed.; Fitness Information Technology: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Carron, A.V. Cohesiveness in Sport Groups: Interpretations and Considerations. J. Sport Psychol. 1982, 4, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapisarda, B.A. The impact of emotional intelligence on work team cohesiveness and performance. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2002, 10, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Xue, L. Relationships among sports group cohesion, psychological collectivism, mental toughness and athlete engagement in Chinese team sports athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høigaard, R.; Säfvenbom, R.; Tønnessen, F.E. The relationship between group cohesion, group norms, and perceived social loafing in soccer teams. Small Group Res. 2006, 37, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedir, D.; Agduman, F.; Bedir, F.; Erhan, S.E. The mediator role of communication skill in the relationship between empathy, team cohesion, and competition performance in curlers. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1115402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Magnusen, M.J.; Andrew, D.P.S. Divided we fall: Examining the relationship between horizontal communication and team commitment via team cohesion. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2016, 11, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budnik-Przybylska, D.; Kaźmierczak, M.; Karasiewicz, K.; Bertollo, M. Spotlight on the link between imagery and empathy in sport. Sport Sci. Health 2021, 17, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carron, A.V.; Widmeyer, W.N.; Brawley, L.R. The development of an instrument to assess cohesion in sport teams: The Group Environment Questionnaire. J. Sport Psychol. 1985, 7, 244–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturbide, L.; Elosúa, P.; Yanes, F. Medida de la cohesión en equipos deportivos: Adaptación al español del Group Environment Questionnaire. Psicothema 2010, 22, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nascimento Junior, J.R.A.D.; Vieira, L.F.; Rosado, A.F.B.; Serpa, S. Validação do Questionário de Ambiente de Grupo (GEQ) para alíngua portuguesa. Mot. Rev. Educ. Física 2012, 18, 770–782. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento Junior, J.R.A.; Contreira, A.R.; Moreira, C.R.; Pizzo, G.C.; Ribeiro, V.T.; Vieira, L.F. Psychometric properties of the Group Environment Questionnaire (GEQ) for the high-performance soccer and futsal context. Rev. Educ. Física/UEM 2016, 27, e2742. [Google Scholar]

- Steca, P.; Pala, A.N.; Greco, A.; Monzani, D.; D’Addario, M. A Psychometric Evaluation of the Group Environment Questionnairein a Sample of Professional Basketball and Soccer Players. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2013, 116, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitton, S.M.; Fletcher, R.B. The Group Environment Questionnaire: A multilevel confirmatory factor analysis. Small Group Res. 2014, 45, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, F.; González-Ponce, I.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Pulido, J.; García-Calvo, T. Adaptation and validation in Spanish of the Group Environment Questionnaire with professional football players. Psicothema 2015, 27, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.; Zhou, S.; Wang, R.; Fan, H.; Wang, Y. Subjective exercise experience and group cohesion among Chinese participating in square dance: A moderated mediation model of years of participation and gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2022, 19, 12978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasecki, P.A.; Loughead, T.; Paradis, K.F.; Munroe-Chandler, K.J. Using a personal-disclosure mutual-sharing approach to deliver a team-based mindfulness meditation program to enhance cohesion. Sport Psychol. 2021, 35, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Santos, R.; Ciruelos, O. Collective efficacy, cohesion, and performance in Spanish amateur female basketball. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2013, 22, 235–238. [Google Scholar]

- González, I.; Sánchez, D.; Amado, D.; Pulido, J.J.; López, J.M.; Leo, F.M. Análisis de la cohesión, la eficacia colectiva y el rendimiento en equipos femeninos de fútbol. Apunt. Educ. Fís. Deporte 2013, 114, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bohórquez Gómez-Millán, M.R.; Delgado Vega, P.; Fernández Gavira, J. Rendimientos deportivos auto y heteropercibidos y cohesión grupal: Un estudio exploratorio. Retos Nuevas Tend. Educ. Física Deporte Recreación 2017, 31, 103–106. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Lafferty, M.E.; Wakefield, C.; Brown, H. “We do it for the team”—Student-athletes’ initiation practices and their impact on group cohesion. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2015, 15, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checa, I.; Gómez-Millán, M.R. Medidas psicométricas de la cohesión en equipos de trabajo universitarios. Retos Nuevas Tend. Educ. Física Deporte Recreación 2020, 37, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ato, M.; López, J.J.; Benavente, A. Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología deportiva. An. Psicol. 2013, 29, 1038–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. On tests and indices for evaluating structural models. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 825–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.T.; Wen, Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler (1999) findings. Struct. Equ. Model. 2004, 11, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, G.; Hwang, H.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. Cutoff criteria for overall model fit indexes in generalized structured component analysis. J. Mark. Anal. 2020, 8, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret-Segura, S.; Ferreres-Traver, A.; Hernández-Baeza, A.; Tomás-Marco, I. El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: Una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. An. Psicol. 2014, 30, 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eys, M.; Loughead, T.; Bray, S.; Carron, A. Development of a Cohesion Questionnaire for Youth: The Youth Sport Environment Questionnaire. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2009, 31, 390–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.L.; Rodrigues, G.T.; de Souza, V.F.M.; Catabriga, L.M.; Kravchychyn, C.; Donato, F.C.; Marção, L.L.; Ferreira, L. Impacto das estratégias de coping e do ambiente de grupo no desempenho de atletas amadores em competição de voleibol. Retos Nuevas Tend. Educ. Física Deporte Recreación 2024, 61, 878–884. [Google Scholar]

| Country/Region | Authors/Year | Sample | Factorial Solution | Reliability (α) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | Nascimento Junior et al., 2012 [12] | 501 athletes | 4-factor model, item adjustments | α 0.76–0.80 |

| Italy | Steca et al., 2013 [14] | 517 male professionals (basketball and soccer) | 4-factor structure, with one modified item | α 0.37–0.76 |

| New Zealand | Whitton and Fletcher, 2014 [15] | 519 semi-elite and elite teams | 4 factor model; with one modified item | α 0.58–0.91 |

| Spain | Leo et al., 2015 [16] | Professional football players | 4-factor model; partial support | α 0.60–0.82 |

| Brazil | Nascimento Junior et al., 2016 [13] | 441 soccer players | 4 factors, with 16 modified items | α 0.75–0.85 |

| China | Gu and Xue, 2022 [5] | 326 active Chinese athletes | 4 factors, with 15 items | α 0.71–0.87 |

| Scales | M | DT | To | K | S-W | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATG-S ω = 0.65 | ||||||

| 1 | 6.83 | 2.67 | −1.07 | −0.1 | 0.77 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 6.47 | 2.94 | −0.70 | −0.74 | 0.78 | <0.001 |

| 5 | 5.82 | 3.08 | −0.36 | −1.41 | 0.83 | <0.001 |

| 7 | 6.32 | 2.91 | −0.68 | −0.94 | 0.81 | <0.001 |

| 9 | 3.98 | 2.66 | 0.44 | −1.01 | 0.88 | <0.001 |

| ATG-T ω = 0.81 | ||||||

| 2 | 6.05 | 2.82 | −0.58 | −0.97 | 0.85 | <0.001 |

| 4 | 5.29 | 3.09 | −0.12 | −1.47 | 0.85 | <0.001 |

| 6 | 5.93 | 2.86 | −0.47 | −1.11 | 0.86 | <0.001 |

| 8 | 5.89 | 2.95 | −0.46 | −1.19 | 0.85 | <0.001 |

| GI-S ω = 0.42 | ||||||

| 11 | 5.35 | 2.18 | −0.09 | −0.46 | 0.94 | <0.001 |

| 13 | 4.45 | 2.64 | 0.23 | −1.05 | 0.91 | <0.001 |

| 15 | 5.56 | 2.24 | −0.12 | −0.53 | 0.93 | <0.001 |

| 17 | 5.60 | 2.64 | −0.25 | −1.01 | 0.91 | <0.001 |

| GI-T ω = 0.22 | ||||||

| 10 | 6.96 | 2.25 | −0.93 | −0.03 | 0.83 | <0.001 |

| 12 | 5.85 | 2.77 | −0.38 | −1.13 | 0.88 | <0.001 |

| 14 | 4.49 | 2.44 | −0.16 | −0.80 | 0.93 | <0.001 |

| 16 | 6.78 | 2.69 | −0.99 | −0.29 | 0.78 | <0.001 |

| 18 | 5.62 | 2.59 | −0.28 | −0.92 | 0.91 | <0.001 |

| Scale | ω | α | M |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATG-T | 0.80 | 0.80 | 23.17 |

| ATG-S | 0.71 | 0.60 | 23.61 |

| GI-T | 0.73 | 0.71 | 23.66 |

| GI-S | 0.52 | 0.50 | 15.42 |

| Models | χ2 | Gl | p | GFI | RMSEA | CFI | IFI | NFI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unidimensional | 177.33 | 84 | <0.01 | 0.90 | 0.07 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.05 |

| Homework/Social | 330.18 | 118 | <0.01 | 0.96 | 0.08 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.08 |

| Attraction/Integration | 382.12 | 134 | <0.01 | 0.95 | 0.09 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.07 |

| Scales | ATG-T | ATG-S | GI-T |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATG-T | - | ||

| ATG-S | 0.66 *** | - | |

| GI-T | 0.19 ** | 0.23 ** | - |

| GI-S | 0.38 ** | 0.38 *** | 0.20 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Corvera-Velarde, F.; Cantú-Berrueto, A.; Mendoza-Farias, F.J.; López-Walle, J.M. Group Environment Questionnaire (GEQ): Validation in Mexican University Athletes. Societies 2025, 15, 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15090259

Corvera-Velarde F, Cantú-Berrueto A, Mendoza-Farias FJ, López-Walle JM. Group Environment Questionnaire (GEQ): Validation in Mexican University Athletes. Societies. 2025; 15(9):259. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15090259

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorvera-Velarde, Faviola, Abril Cantú-Berrueto, Francisco Javier Mendoza-Farias, and Jeanette M. López-Walle. 2025. "Group Environment Questionnaire (GEQ): Validation in Mexican University Athletes" Societies 15, no. 9: 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15090259

APA StyleCorvera-Velarde, F., Cantú-Berrueto, A., Mendoza-Farias, F. J., & López-Walle, J. M. (2025). Group Environment Questionnaire (GEQ): Validation in Mexican University Athletes. Societies, 15(9), 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15090259