FoMO as a Predictor of Cyber Dating Violence Among Young Adults: Understanding Digital Risk Factors in Romantic Relationships

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Cyber Dating Violence

1.2. Fear of Missing Out

1.3. Aims of the Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics Information

2.2.2. Cyber Dating Violence

2.2.3. Fear of Missing out

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitation and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kranenbarg, M.W.; Van Gelder, J.L.; Barends, A.J.; de Vries, R.E. Is there a cybercriminal personality? Comparing cyber offenders and offline offenders on HEXACO personality domains and their underlying facets. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 140, 107576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawrin, M.K.; Nderego, E.F. Psychological challenges of cyberspace: A systematical review of meta-analysis. Indian. J. Health Wellbeing 2022, 13, 294–300. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, L.M.; Clemans, K.H.; Graber, J.A.; Lyndon, S.T. Traditional and cyber aggressors and victims: A comparison of psychosocial characteristics. J. Youth Adolesc. 2011, 40, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caridade, S.; Braga, T.; Borrajo, E. Cyber dating abuse (CDA): Evidence from a systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019, 48, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoffstall, C.L.; Cohen, R. Cyber aggression: The relation between online offenders and offline social competence. Soc. Dev. 2011, 20, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, M.; Nappa, M.R.; Chirumbolo, A.; Wright, P.J.; Pabian, S.; Baiocco, R.; Cattelino, E. Is adolescents’ cyber dating violence perpetration related to problematic pornography use? The moderating role of hostile sexism. J. Health Commun. 2024, 39, 3134–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick, A. A meta-analysis of media consumption and rape myth acceptance. J. Health Commun. 2021, 26, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hust, S.J.T.; Rodgers, K.B.; Cameron, N.; Li, J. Viewers’ perceptions of objectified images of women in alcohol advertisements and their intentions to intervene in alcohol-facilitated sexual assault situations. J. Health Commun. 2019, 24, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.J.; Paul, B.; Herbenick, D. Preliminary insights from a US probability sample on adolescents’ pornography exposure, media psychology, and sexual aggression. J. Health Commun. 2021, 26, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascardi, M.; Avery-Leaf, S. Gender differences in dating aggression and victimization among low-income, urban middle school students. Partn. Abus. 2015, 6, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Rivas, M.J.; Redondo, N.; Zamarrón, D.; González, M.P. Violence in dating relationships: Validation of the Dominating and Jealous Tactics Scale in Spanish youth. An. Psicol./Ann. Psychol. 2019, 35, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, M.L.; Thompson, R.E. Predicting the emergence of sexual violence in adolescence. Prev. Sci. 2018, 19, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, S.H. The power of family and community factors in predicting dating violence: A meta-analysis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 40, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, P.; McGarry, J.; Dhingra, K. Identifying signs of intimate partner violence. Emerg. Nurse 2016, 23, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrascosa, L.; Cava, M.J.; Buelga, S. Perfil psicosocial de adolescentes españoles agresores y víctimas de violencia de pareja. Univ. Psychol. 2018, 17, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, T.L.; Resseguie, N. Primary and secondary prevention programs for dating violence: A review of the literature. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2007, 12, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, J.L.; Bromfield, L. Better together? A review of evidence for multi-disciplinary teams responding to physical and sexual child abuse. Trauma. Violence Abus. 2019, 20, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazos, M.; Oliva, A.; Hernando, A. Violencia en relaciones de pareja jóvenes y adolescentes. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2014, 46, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey Anacona, C.A. Prevalence, risk factors, and problems associated with dating violence: A literature review. Av. En Psicol. Latinoam. 2008, 26, 227–241. Available online: http://repository.urosario.edu.co/handle/10336/15974 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Wolfe, D.A.; Wekerle, C.; Scott, K.; Straatman, A.L.; Grasley, C. Predicting abuse in adolescent dating relationships over 1 year: The role of child maltreatment and trauma. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2004, 113, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdol, L.; Moffitt, T.E.; Caspi, A.; Newman, D.L.; Fagan, J.; Silva, P.A. Gender differences in partner violence in a birth cohort of 21-year-olds: Bridging the gap between clinical and epidemiological approaches. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1997, 65, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.P.; Magee, M.M.; Griffin, L.D.; Dupuis, C.W. Effects of a group preventive intervention on risk and protective factors related to dating violence. Group. Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2004, 8, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrajo, E.; Gámez-Guadix, M.; Pereda, N.; Calvete, E. The development and validation of the cyber dating abuse questionnaire among young couples. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Reyes, V.; Jaureguizar, J.; Redondo, I. Cyberviolence in young couples and its predictors. Behav. Psychol./Psicol. Conduct. 2022, 30, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollen, E.W.; Ameral, V.E.; Palm Reed, K.; Hines, D.A. Sexual minority college students’ perceptions on dating violence and sexual assault. J. Couns. Psychol. 2017, 64, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, M.; Bianchi, D.; Chirumbolo, A.; Baiocco, R. The cyber dating violence inventory: Validation of a new scale for online perpetration and victimization among dating partners. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 15, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrajo, E.; Gámez-Guadix, M. Abuso” online” en el noviazgo: Relación con depresión, ansiedad y ajuste diádico. Behav. Psychol. 2016, 24, 221. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10486/679217 (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Draucker, C.B.; Martsolf, D.S. The role of electronic communication technology in adolescent dating violence. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2010, 23, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernet, M.; Lapierre, A.; Hébert, M.; Cousineau, M.M. A systematic review of literature on cyber intimate partner victimization in adolescent girls and women. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 100, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweig, J.M.; Dank, M.; Yahner, J.; Lachman, P. The rate of cyber dating abuse among teens and how it relates to other forms of teen dating violence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 42, 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-deArriba, M.L.; Nocentini, A.; Menesini, E.; Sánchez-Jiménez, V. Dimensions and measures of cyber dating violence in adolescents: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2021, 58, 101613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flach, R.M.D.; Deslandes, S.F. Cyber dating abuse in affective and sexual relationships: A literature review. Cad. Saúde Pública 2017, 33, e00138516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galende, N.; Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Jaureguizar, J.; Redondo, I. Cyber dating violence prevention programs in universal populations: A systematic review. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patchin, J.W.; Hinduja, S. Sextortion among adolescents: Results from a national survey of US youth. Sex. Abus. 2020, 32, 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.; Cénat, J.M.; Lapierre, A.; Dion, J.; Hébert, M.; Côté, K. Cyber dating violence: Prevalence and correlates among high school students from small urban areas in Quebec. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 234, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Ouytsel, J.; Ponnet, K.; Walrave, M. Cyber dating abuse: Investigating digital monitoring behaviors among adolescents from a social learning perspective. J. Interpers. Violence 2017, 35, 5157–5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, D.M.; Knoble, N.B.; Shortt, J.W.; Kim, H.K. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partn. Abus. 2012, 3, 231–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohut, A.; Keeter, S.; Doherty, C.; Dimock, M.; Christian, L. Assessing the Representativeness of Public Opinion Surveys; Pew Research Internet Project; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Leisring, P.A.; Giumetti, G.W. Sticks and stones may break my bones, but abusive text messages also hurt: Development and validation of the Cyber Psychological Abuse scale. Partn. Abus. 2014, 5, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, M.J.; Martínez-Ferrer, B.; Buelga, S.; Carrascosa, L. Sexist attitudes, romantic myths, and offline dating violence as predictors of cyber dating violence perpetration in adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 111, 106449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, K.; Keast, H.; Ellis, W. The impact of cyber dating abuse on self-esteem: The mediating role of emotional distress. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2017, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taquette, S.R.; Monteiro, D.L.M. Causes and consequences of adolescent dating violence: A systematic review. J. Inj. Violence Res. 2019, 11, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghtaie, N.; Larkins, C.; Barte, C.; Stanley, N.; Wood, M.; Øverlien, C. Interpersonal violence and abuse in young people’s relationships in five European countries: Online and offline normalisation of heteronormativity. J. Gend.-Based Violence 2018, 2, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonard, K.E. The prevalence and overlap of technology-assisted and offline adolescent dating violence. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 1056–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, M.; Bianchi, D.; Cattelino, E.; Nappa, M.R.; Baiocco, R.; Chirumbolo, A. Quando il Sexting diventa una forma di violenza? Motivazioni al sexting e dating violence nei giovani adulti. Maltrattam. Abus. Infanz. 2017, 19, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J.R.; Choi, H.J.; Brem, M.; Wolford-Clevenger, C.; Stuart, G.L.; Peskin, M.F.; Elmquist, J. The temporal association between traditional and cyber dating abuse among adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, A.M.; King, L.; Abbey, A.; Boyd, C.J. Adolescent peer-on-peer sexual aggression: Characteristics of aggressors of alcohol and non-alcohol related assault. J. Stud. Alcohol. Drugs 2009, 70, 700–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reed, L.A.; Tolman, R.M.; Ward, L.M. Gender matters: Experiences and consequences of digital dating abuse victimization in adolescent dating relationships. J. Adolesc. 2017, 59, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.A.; Ward, L.M.; Tolman, R.M.; Lippman, J.R.; Seabrook, R.C. The association between stereotypical gender and dating beliefs and digital dating abuse perpetration in adolescent dating relationships. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP5561–NP5585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ouytsel, J.; Ponnet, K.; Walrave, M. Cyber dating abuse victimization among secondary school students from a lifestyle-routine activities theory perspective. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 33, 2767–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, B.; Caridade, S.; Araújo, I.; Lobato, P. Mapping the cyber interpersonal violence among young populations: A scoping review. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dank, P.; Lachman, P.; Zweig, J.M.; Yahner, J. Dating violence experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorent, V.J.; Ortega-Ruiz, R.; Zych, I. Bullying and cyberbullying in minorities: Are they more vulnerable than the majority group? Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Storey, A. Prevalence of dating violence among sexual minority youth: Variation across gender, sexual minority identity and gender of sexual partners. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015, 44, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisner, S.L.; Greytak, E.A.; Parsons, J.T.; Ybarra, M.L. Gender minority social stress in adolescence: Disparities in adolescent bullying and substance use by gender identity. J. Sex. Res. 2015, 52, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkett, M.; Espelage, D.L.; Koenig, B. LGB and questioning students in schools: The moderating effects of homophobic bullying and school climate on negative outcomes. J. Youth Adolesc. 2009, 38, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhai, J.D.; Yang, H.; Montag, C. Fear of missing out (FOMO): Overview, theoretical underpinnings, and literature review on relations with severity of negative affectivity and problematic technology use. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2020, 43, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Murayama, K.; DeHaan, C.R.; Gladwell, V. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Raza, A.; Haider, A.; Ishaq, M.I. Fear of missing out and compulsive buying behavior: The moderating role of mindfulness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Dhir, A.; Talwar, S.; Kaur, P.; Mäntymäki, M. Dark consequences of social media-induced fear of missing out (FoMO): Social media stalking, comparisons, and fatigue. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 171, 120931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Bao, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Wei, X.; Lei, L. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescents’ cyberbullying victimization: The new phenomenon of a “cycle of victimization”. Child. Abuse Negl. 2022, 134, 105888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, M.; Rosati, F.; Chirumbolo, A.; Baiocco, R.; Nappa, M.R.; Cattelino, E. Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) and sexting motivations among Italian young adults: Investigating the impact of age, gender, and sexual orientation. J. Soc. Pers. Relationsh. 2025, 42, 633–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, P.; Sariyska, R.; Riedl, R.; Lachmann, B.; Montag, C. Linking internet communication and smartphone use disorder by taking a closer look at the Facebook and WhatsApp applications. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2019, 9, 100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzi, I.M.A.; Fontana, A.; Lingiardi, V.; Parolin, L.; Carone, N. “Don’t Leave me Behind!” Problematic Internet Use and Fear of Missing Out Through the Lens of Epistemic Trust in Emerging Adulthood. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 13775–13784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; Altavilla, D.; Ronconi, A.; Aceto, P. Fear of missing out (FOMO) is associated with activation of the right middle temporal gyrus during inclusion social cue. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, N.I.; Lieberman, M.D. Why rejection hurts: A common neural alarm system for physical and social pain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2004, 8, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, L.; Liu, Y. The identity-based explanation of affective commitment. J. Manag. Psychol. 2014, 29, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D. Social identity, self as structure and self as process. In Social Groups and Identities: Developing the Legacy of Henri Tajfel; Robinson, W.P., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1996; pp. 143–167. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzadi, N.; Asim, S.; Toor, M.A.; Arshad, M. Five Factor Model of Personality as a Predicator of Callous-Unemotional Traits among Students. Pak. J. Psychol. Res. 2024, 39, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramsky, T.; Watts, C.H.; Garcia-Moreno, C.; Devries, K.; Kiss, L.; Ellsberg, M.; Jansen, H.A.; Heise, L. What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. BMC Public. Health 2011, 11, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breiding, M.J.; Black, M.C.; Ryan, G.W. Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence in eighteen US states/territories, 2005. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhu, F.; O’Campo, P.; Koenig, M.A.; Mock, V.; Campbell, J. Prevalence of and risk factors for intimate partner violence in China. Am. J. Public. Health 2005, 95, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N.W.; Yao, W. Assessing the Victim–Perpetrator Overlap in Adolescent Dating Violence in China: A Latent Class Analysis. J. Interpers. Violence 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, S.H. Who are the victims and who are the perpetrators in dating violence? Sharing the role of victim and perpetrator. Trauma. Violence Abus. 2019, 20, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reingle, J.M.; Staras, S.A.; Jennings, W.G.; Branchini, J.; Maldonado-Molina, M.M. The relationship between marijuana use and intimate partner violence in a nationally representative, longitudinal sample. J. Interpers. Violence 2012, 27, 1562–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reingle, J.M. Victim–offender overlap. In Encyclopedia of Theoretical Criminology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.M. Incidence and outcomes of dating violence victimization among high school youth: The role of gender and sexual orientation. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 33, 1472–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, M.; Bianchi, D.; Baiocco, R.; Pezzuti, L.; Chirumbolo, A. Sexting, psychological distress and dating violence among adolescents and young adults. Psicothema 2016, 28, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ran, G.; Zhang, Q.; He, X. The prevalence of cyber dating abuse among adolescents and emerging adults: A meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 144, 107726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsey, A.C.; Pomeroy, W.R.; Martin, C.E. Sexual behavior in the human male. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 894–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nappa, M.R.; Morelli, M.; Bianchi, D.; Baiocco, R.; Cattelino, E.; Chirumbolo, A. The dark side of homophobic bullying: The moderating role of dark triad traits in the relationship between victim and perpetrator. Rass. Psicol. 2019, 36, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, S.; Fioravanti, G. Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Italian version of the fear of missing out scale in emerging adults and adolescents. Addict. Behav. 2020, 102, 106179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbe, J.M. Negative Binomial Regression; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamovi, version 2.3; Computer Software; The Jamovi Project: Sydney, Australia, 2023.

- Gallucci, M. GAMLj: General Analyses for the Linear Model in Jamovi. Available online: https://gamlj.github.io/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Alfasi, Y. Attachment insecurity and social media fear of missing out: The mediating role of intolerance of uncertainty. Digit. Psychol. 2021, 2, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durao, M.; Etchezahar, E.; Albalá Genol, M.Á.; Muller, M. Fear of missing out, emotional intelligence and attachment in older adults in Argentina. J. Intell. 2023, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yan, S.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, Y. Do mobile social media undermine our romantic relationships? The influence of fear-of-missing-out on young people’s romantic relationships. In Proceedings of the Information Behaviour Conference (ISIC), Berlin, Germany, 26–29 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Varchetta, M.; Fraschetti, A.; Mari, E.; Giannini, A.M. Social Media Addiction, Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) and online vulnerability in university students. Rev. Digit. Investig. Docencia Univ. 2020, 14, e1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Sánchez, J.G. Factores psicológicos y consecuencias del Síndrome Fear of Missing Out: Una Revisión Sistemática. J. Psychol. Educ./Rev. De Psicol. Y Educ. 2022, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinker, V.; Dewald-Kaufmann, J.; Padberg, F.; Reinhard, M.A. Aggressive intentions after social exclusion and their association with loneliness. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 273, 1023–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, J.; Cai, G.; Wei, X. Social exclusion and social anxiety among Chinese undergraduate students: Fear of negative evaluation and resilience as mediators. J. Psychol. Afr. 2024, 34, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Baumeister, R.F. Social exclusion increases aggression and self-defeating behavior while reducing intelligent thought and prosocial behavior. In Social Psychology of Inclusion and Exclusion; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2004; pp. 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Rozgonjuk, D.; Sindermann, C.; Elhai, J.D.; Montag, C. Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) and social media’s impact on daily-life and productivity at work: Do WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat Use Disorders mediate that association? Addict. Behav. 2020, 110, 106487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Vega, L.E.; Gómez-Muñoz, A.M.; Feliciano-García, L. Adolescents Problematic Mobile Phone Use, Fear of Missing out and Family Communication. Comun. Media Educ. Res. J. 2019, 27, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, M.; Urbini, F.; Bianchi, D.; Baiocco, R.; Cattelino, E.; Laghi, F.; Chirumbolo, A. The relationship between dark triad personality traits and sexting behaviors among adolescents and young adults across 11 countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, M.; Plata, M.G.; Isolani, S.; Zabala, M.E.Z.; Hoyos, K.P.C.; Tirado, L.M.U.; Baiocco, R. Sexting behaviors before and during COVID-19 in Italian and Colombian young adults. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2023, 20, 1515–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.CDV perpetration | 1 | 3.41 (4.20) | |||||

| 2.CDV victimization | 0.78 *** | 1 | 3.73 (4.91) | ||||

| 3.FoMO | 0.13 *** | 0.13 *** | 1 | 24.3 (8.31) | |||

| 4. Age | −0.07 * | −0.09 ** | −0.21 *** | 1 | 22.3 (2.57) | ||

| 5.Gender | 0.71 * | −0.03 | 0.92 ** | −0.06 | 1 | / | |

| 6.Sexual orientation | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.13 *** | −0.02 | 0.14 *** | 1 | / |

| Cyber Dating Violence Perpetration | Cyber Dating Violence Victimization | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | B | SE | Exp(B) | LCI | UCI | p | B | SE | Exp(B) | LCI | UCI | p |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.02 | 0.41 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 0.05 |

| Gender | −0.13 | 0.10 | 0.88 | 0.72 | 1.07 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 1.17 | 0.95 | 1.45 | 0.13 |

| SO | 0.02 | 0.10 | 1.02 | 0.84 | 1.25 | 0.80 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 1.04 | 0.85 | 1.28 | 0.68 |

| FoMO | 0.03 | 0.01 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.04 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.04 | <0.001 |

| FoMO*Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.05 | 0.85 |

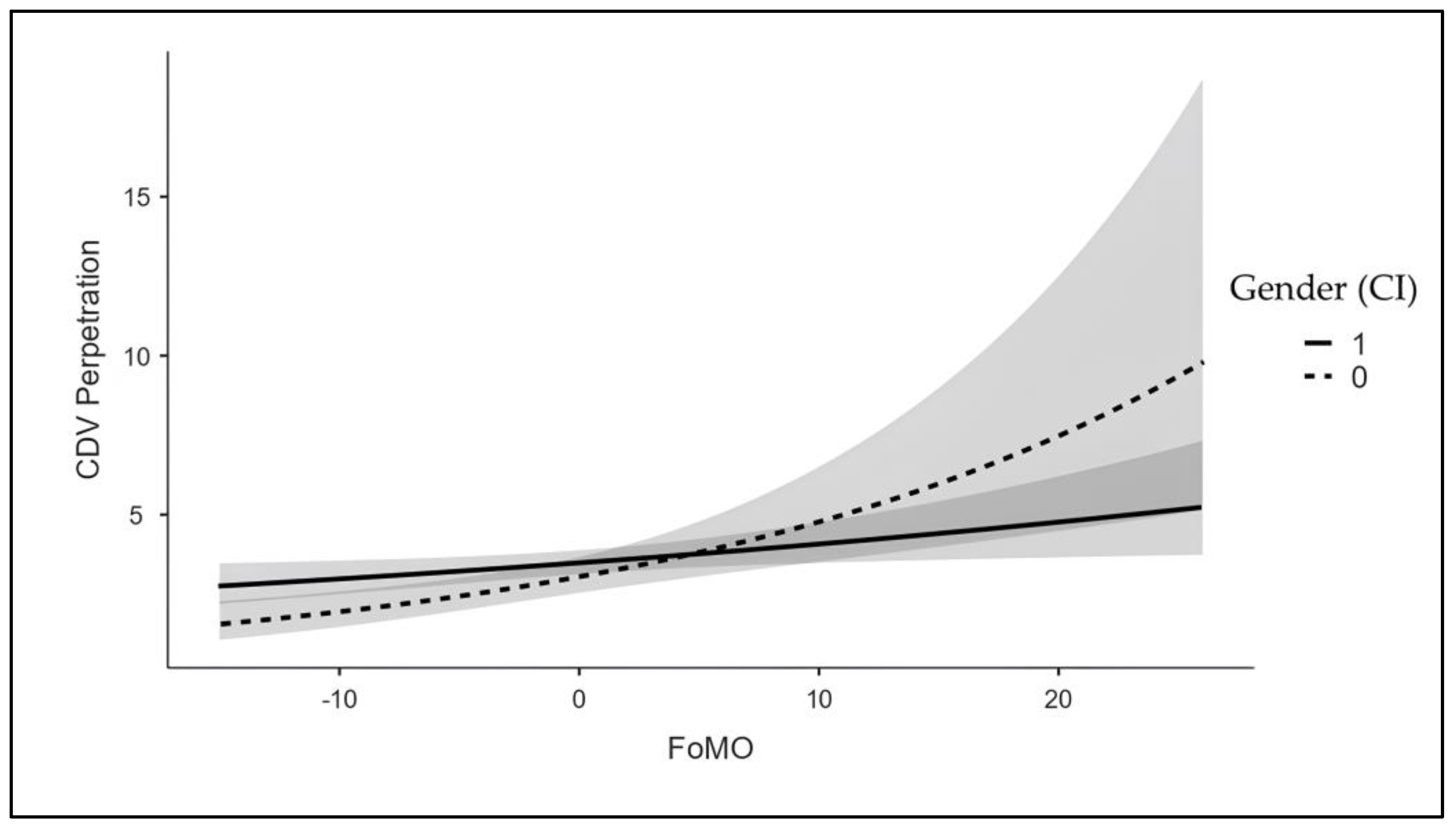

| FoMO*Gender | 0.03 | 0.01 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.04 | 0.22 |

| FoMO*SO | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.05 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ragona, A.; Morelli, M.; Ruggeri, L.; Cattelino, E.; Chirumbolo, A. FoMO as a Predictor of Cyber Dating Violence Among Young Adults: Understanding Digital Risk Factors in Romantic Relationships. Societies 2025, 15, 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15090258

Ragona A, Morelli M, Ruggeri L, Cattelino E, Chirumbolo A. FoMO as a Predictor of Cyber Dating Violence Among Young Adults: Understanding Digital Risk Factors in Romantic Relationships. Societies. 2025; 15(9):258. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15090258

Chicago/Turabian StyleRagona, Alessandra, Mara Morelli, Lia Ruggeri, Elena Cattelino, and Antonio Chirumbolo. 2025. "FoMO as a Predictor of Cyber Dating Violence Among Young Adults: Understanding Digital Risk Factors in Romantic Relationships" Societies 15, no. 9: 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15090258

APA StyleRagona, A., Morelli, M., Ruggeri, L., Cattelino, E., & Chirumbolo, A. (2025). FoMO as a Predictor of Cyber Dating Violence Among Young Adults: Understanding Digital Risk Factors in Romantic Relationships. Societies, 15(9), 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15090258