1. Introduction

Since the second half of the 20th century, the concept of stress has gained increasing attention in psychology, medicine, and the social sciences. Initially discussed mainly within clinical settings, it has now become an integral part of everyday language and thinking. Over the past decades, stress has emerged as a global problem, amplified by modern lifestyles, urbanization, rapid technological changes, and heavy work demands.

As Brinkmann [

1] explains, stress has become a symbol of many inconveniences of modern life, appearing in diverse situations such as workplace tasks, household responsibilities, traffic challenges, or daily administrative hurdles. Stress, being a natural part of survival and adaptation processes, is not inherently harmful. In some cases, positive stress, or eustress [

2], can enhance performance and motivation. However, chronic and prolonged stress, particularly in the workplace, can lead to serious mental and physical health issues. Therefore, managing and preventing stress is crucial for maintaining both individual well-being and societal health quality.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has emphasized the importance of supportive environments and health-conscious lifestyles since the Ottawa Charter of 1986, advocating for systemic interventions at the level of communities, schools, and workplaces. Chronic workplace stress notably contributes to cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and other health risks [

1]. According to the 2023 IPSOS survey, one-third of the Hungarian population identifies stress as a major health concern, demonstrating its growing societal impact [

3]. Given that employees spend a significant portion of their lives at work, where they often face high expectations and constant pressure, the workplace is a critical arena for stress management and prevention initiatives. Recognizing the workplace as a setting for health promotion is crucial according to the WHO’s guidelines.

Today, people spend a significant part of their working lives in a work environment, with an average working week of around 40 h. Work is not only a means of making a living; it also becomes an important part of personal identity and social relationships. On the one hand, it can give purpose and meaning, as well as structure and content to our days, weeks, years, and lives. It also plays an important role in the development of an individual’s identity and self-esteem. These positive effects are most effective when work demands are optimal (rather than maximal), when employees are allowed to exercise a reasonable degree of autonomy, and when the work organization has a friendly and supportive atmosphere. If this is the case, then work can be one of the most important health-promoting (salutogenic) factors in life [

4]. Conversely, if these conditions are not met, many stressors present in the work context can have significant negative effects on individuals’ health, one of the most significant of which is work-related stress. In a survey of 31 European countries, 40% of workers felt that stress was not adequately managed at work [

5]. As a consequence, there is a growing recognition in the academic community of the seriousness of the challenges of work-related stress and psychosocial risks in the field of occupational health and safety, which is cited by many actors (e.g., the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, governments, policy-makers, researchers) as a global workplace and public health problem [

6].

The father of the modern concept of stress is Selye. It was Selye, a Austro-Hungarian doctor, who really popularized the concept of stress. He first used it in 1936 to describe the strain on the body caused by physical and psychological stressors (such as heat, cold, excessive demands, or time pressure). According to Selye, these stressors trigger a non-specific response of the body, characterized mainly by the activity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, i.e., the release of glucocorticoids (steroid hormones of the adrenal cortex). This process, which is always stereotyped and non-specific, has been termed general adaptation syndrome. According to Selye’s and more modern interpretations, stress is therefore a neutral concept, which is nothing more than the body’s reaction to constant demands and stress. Within this, Selye differentiates between two types: eustress and distress, depending on the impact of the stress. Eustress refers to a positive type of stress that inspires and motivates performance, while distress has a negative impact on the individual and is experienced as a burden [

7].

The concept of stress is discussed in many approaches from different perspectives, whether biological reactions, environmental influences, or cognitive appraisal processes [

8]. There are also many models in workplace stress research that examine the development and effects of stress on employees from different perspectives. These models help to understand how stress affects workers’ well-being and performance, and how stress can be managed effectively. One of the most influential theoretical models in this area is the Job Demand-Control Model (JDC), developed by Karasek [

9]. This model emphasizes that high job demands can in themselves cause stress, but that, if an individual has sufficient control over his or her job, the level of stress can be reduced. If job demands are high but control is low, this can lead to increased stress, which in the long run can lead to burnout and health problems [

10]. The Job Demand-Resources Model (JDR) is an improved version of the JDC model that also considers the resources available to workers. According to the model, not only job demands, but also resources, play an important role in the management of stress. Resources can be physical (e.g., adequate working conditions), psychological (e.g., self-confidence), social (e.g., support from colleagues), or organizational (e.g., career development opportunities). The model assumes that the presence of adequate resources can alleviate stress caused by high demands and improve employee performance and well-being. The JDR model’s view of psychological resources can be closely related to the concept of psychological capital (PsyCap), also explored in this thesis, and its implications in the workplace context. Thus, according to the JDR model, such psychological resources, among which PsyCap can be considered one, contribute to workers’ better responses to high job demands, thus reducing stress levels and increasing well-being and performance. Therefore, PsyCap can also be considered as an internal resource that enhances employees’ resilience to workplace stressors and plays a particularly important role in managing stress and optimizing employee performance in the context of the JDR model [

10]. Another model, the Effort–Reward Imbalance Model (ERI), created by Siegrist [

11], suggests that stress occurs when individuals make significant efforts but are not adequately rewarded for these efforts. This imbalance triggers negative emotions and stress, whereas a balanced effort–reward relationship can result in positive emotions and improved well-being. The Conservation of Resources Theory (COR), by Hobfoll [

12], also focuses on the management of stress at work, but with an emphasis on the conservation and enhancement of an individual’s resources. According to Hobfoll’s theory, stress occurs when an individual’s resources are threatened or when he or she is unable to acquire the resources needed to cope with stressors. Stress is amplified when an individual suffers a loss of these resources. In summary, workplace stress models shed light on different aspects of how stress develops and is managed. While the transactional model emphasizes the role of cognitive appraisal, the JDC and JDR models focus on the balance between job demands and resources. The ERI model emphasizes the fairness of social exchanges, while COR theory focuses on the conservation and acquisition of an individual’s resources. What these models have in common is an emphasis on the importance of resources, whether external or internal.

Stress at work is a major problem worldwide, closely linked to health risks. According to research [

13], workplace stress is the second most significant source of stress for US workers and is also associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. This trend is not only observed in the US, but also globally. In Germany, a survey by Techniker Krankenkasse [

14] found that nearly half of employees identified their workplace as a primary source of stress, with excessive workload, tight deadlines, constant interruptions, and work–life imbalance being the most common causes. In addition, the number of sick days taken due to burnout has increased dramatically in recent years, almost 20-fold since 2004, underlining the health effects of workplace stress. In Hungary, a research team from Semmelweis University investigated the psychosocial risk factors of workplace stress in 2013, as part of the National Workplace Stress Survey, involving more than 19,000 employees. The COPSOQ II questionnaire used in the survey assessed several stress factors [

15]. Notably, 40% of the participants had experienced nagging at work, one of the most significant risk factors for work-related stress. The results of this research therefore underline the importance of examining mobbing in a thesis, highlighting its relevance and necessity. Moreover, international comparisons of the COPSOQ II questionnaire have also shown that Hungary scores worse than other countries in terms of workplace stress, due to low scores in job meaningfulness and quality of leadership [

15]. These findings clearly show that both workplace stress and the problem of mobbing or bullying has a serious impact on the quality of life of workers. This makes the study of mobbing particularly important, as a better understanding of this phenomenon is essential in reducing workplace stress and improving workers’ mental well-being.

In terms of definition, there are several other terms and concepts that are associated with mobbing. Workplace aggression is perhaps one of the most common terms used in this context [

16]. This term covers all forms of behavior whereby individuals attempt to cause harm to others in their workplace or organization. However, harm at work can take different forms. Some aggression is overt, such as physical attacks. In such cases, the term workplace violence is used. This term is much more specific than workplace aggression, as it refers only to cases where direct physical assaults or aggressions occur in the workplace. Examples include threats of physical violence, armed assaults, or physical acts such as pushing another person [

17].

Another term is used in the literature that also refers to workplace harassment and is most often identified as bullying. Especially in the English-speaking context, workplace bullying is used as a synonym for mobbing [

18]. Bullying also involves purposeful, aggressive behavior towards the victim, which occurs repeatedly. It is important to note that the term bullying is also associated with threats of violence and aggression, but this is rarely the case in workplace bullying [

19]. The concept of conflict is also closely related to bullying. Social conflict describes an interaction between persons where at least one party experiences different perceptions, thinking, and emotions from the other [

20], and the difference between bullying and conflict is related to a temporal characteristic: in the case of bullying, bullying must occur at least once a week for at least 6 months [

19]; conflict has no such temporal limitation. Of course, a conflict can also develop into mobbing, but this is by no means true for all workplace conflicts [

19]. Not far removed from mobbing is workplace incivilities, which are low-intensity, non-standard behaviors aimed at offending the other party by disregarding workplace norms. The intentions here are not always clear, but the behavior is usually impolite and reflects a lack of respect for others [

21]. Intensity is not a factor in the definition of mobbing, but it is assumed that the intensity of mobbing is higher with increased frequency and longevity [

22]. Separate from mobbing, there is also the phenomenon of bossing (abusive supervision), where managers engage in persistent, hostile verbal and non-verbal behavior towards their subordinates without physical contact [

23]. According to Hershcovis [

22], three main factors can be highlighted that distinguish this concept from others: the offensive leader, the persistent nature of the behavior, and the fact that physical actions are not part of the concept. However, this construct can also be defined as a specific form of mobbing. Social undermining is also a construct that addresses a particular aspect of workplace aggression. Duffy, Ganster, and Pagon [

24] define social undermining in the workplace as behavior that is intended to prevent others from developing positive relationships, success, and reputation at work. Compared to the previously mentioned constructs, the outcomes are particularly emphasized here. The intentions are those of the aggressor, and this construct also suggests that it can lead to the deterioration of workplace relationships. The behavior and attitudes of third parties, such as co-workers or managers, may change because of undermining the victim [

22]. Workplace bullying is defined as a broad spectrum of workplace aggression and is one of its defining types. A detailed description of the types has proved important in placing these phenomena precisely in context and distinguishing them clearly from other forms of aggression. This will allow a better understanding of the specificities of mobbing and how it fits into the broader framework of psychosocial risks at work.

The literature on the consequences of workplace mobbing has been growing in recent decades, especially since the 1990s, when research in this area saw a significant upsurge, particularly in Scandinavia. During this period, researchers have recognized a growing problem with serious psychological and economic consequences for both individuals and organizations. The phenomenon of workplace mobbing has also attracted considerable interest in psychological research in the German-speaking world and is now an indispensable area of research in the literature on mental health in the workplace. However, as the literature highlights, many challenges remain, especially regarding the theoretical basis and the effectiveness of prevention and treatment strategies. Although the terms bullying and mobbing are often used to describe bullying behavior, workplace mobbing appears to be the most consistently used term within the research community. Over the past two decades, researchers have made significant progress in developing conceptual clarifications, frameworks, and theoretical explanations to help understand and address this highly complex, but often oversimplified and misunderstood, phenomenon. Indeed, as a phenomenon, workplace mobbing is now better understood and research findings are relatively consistent regarding its prevalence, targets, witnesses, and negative effects on organizational effectiveness, as well as some of its likely antecedents. This thesis uses Leymann’s definition, which was discussed in more detail above. Workplace mobbing is defined as follows: the term mobbing refers to deliberate harassment or hostility directed at a person at least once a week for 6 months, with the purpose of removing that person from the workplace community or job [

19].

Psychological capital (PsyCap) is a relatively new concept that has grown out of the positive psychology movement. It is a branch of psychology that focuses on the scientific study of the positive experiences, strengths, and virtues of human life. It has been popularized by prominent psychologists such as Martin Seligman, who have shifted the focus from the traditional deficit-focused approach to human development and well-being. It was in this vein that Luthans et al. [

25] introduced the concept of PsyCap to draw attention to the positive psychological resources of individuals. The study of this construct in the workplace context, particularly in relation to stress, is relevant and valuable in several ways as it is particularly important in times of increasing stress and burnout to find solutions that not only aim to alleviate external circumstances, but also focus on strengthening the psychological capacities of the individual. The research on PsyCap is also important to me because I believe that understanding and developing it can play a significant role in reducing stress in the workplace and promoting the overall well-being of employees.

The construct is made up of four main elements, often known as the HERO model: hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism are the four main psychological resources that together form the higher-order construct of PsyCap. These components rely on each other and act synergistically, thus collectively forming a whole that is greater than the sum of the parts [

26]. Empirical research has also demonstrated that each of the four PsyCap components has a unique impact and contributes to the construct of PsyCap. In addition, these resources have a convergent property, meaning that together they form a higher-level hidden structure. Luthans distinguishes PsyCap from other concepts and forms of human capital and social capital. Human capital, in Luthans’ view, is the sum of personal knowledge, skills, and abilities that can be developed through experience or training. The other form of capital distinguished by Luthans, social capital, is a concept from sociology and refers to the network of mutual acquaintanceships and relationships that can help social progress. In other words, while human capital focuses more on what you know and social capital on who you know, PsyCap builds on the individual’s inner resources: who you are and what you can become [

25]. Although we often use terms such as hope or optimism in everyday conversation, in the concept of PsyCap, these dimensions have specific meanings. Hope in the scientific context of PsyCap means that an individual can see a possible path to a better future; the term includes the willpower to achieve goals. It is important for hope to formulate plausible and achievable goals and to be able to find new or alternative ways to overcome obstacles. Efficacy/self-efficacy means that an individual is confident that, after making the necessary efforts, he or she can successfully follow a path to achieve goals. Resilience is the ability of an individual to return to baseline or an even stronger position after emotionally challenging life events, including stressful work situations. This includes the ability to bounce back from adversity and to cope with challenges, particularly through mental, emotional, and behavioral resilience. Optimism refers to the way one views life and tends to attribute positive events to one’s own or one’s community’s abilities, while negative events are attributed to temporary, external circumstances. Optimism also refers to the general tendency to expect good things in the future. Importantly, optimism is not an unrealistic belief or expectation that everything will always go smoothly. Rather, it refers to an attitude that the future will generally be positive, coupled with an understanding that life will naturally bring challenges [

27].

While PsyCap is known to buffer stress, it is unclear how it interacts with negative social stressors like mobbing [

28,

29]. Moreover, few studies have compared these dynamics across countries; therefore, our research is gap-filling, and aims to start a discussion on the topic. Given the evidence that PsyCap can mitigate stress and that high-stress environments may breed conflict, we propose to examine how PsyCap and mobbing concurrently influence stress levels. Our study extends previous research by addressing these factors in three countries. We set the following hypotheses:

H1.

There is a negative correlation between PsyCap and perceived job stress. This hypothesis suggests that individuals with higher PsyCap experience lower levels of stress at work because PsyCap facilitates effective stress management. According to this theory, PsyCap is an internal resource that supports individuals in coping with stress. Theoretical approaches and the literature both support the contention that PsyCap enhances individuals’ coping skills, thereby reducing perceived stress levels [25,30]. H2.

There is a positive correlation between job stress and experiences of workplace bullying/bullying. The presence of mobbing increases perceived workplace stress because it can destabilize an individual’s psychological well-being. The relationship between stress and mobbing is supported by several literature sources, which suggest that mobbing exposes individuals to ongoing psychological strain [19,31]. H3.

There is a significant difference between groups with high, medium, and low PsyCap in terms of perceived work stress. Different levels of PsyCap may be associated with different perceptions of stress. This hypothesis assumes that individuals with higher PsyCap experience less intense workplace stress at work [32]. At the planning phase of the research, we did not aim to examine the moderating or mediating factors; however, the findings in this paper refer to some factors, mentioning the need for further studies in this field.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

The questionnaire focused primarily on people with employment status in Germany, Austria, or Hungary, with a particular focus on those who may have been victims of mobbing or harassment in the workplace. The questionnaire was designed and data collected using SoSci Survey software. Prior to data collection, a preliminary pre-test was carried out to clarify any misunderstandings or problems. The formal data collection took place between 29 September and 17 October 2024. For the 106 answers, data cleaning consisted of the following steps: exclusion of incomplete and overly brief interviews, checking for response bias, checking for target group membership, and analyzing outliers. The final, cleansed dataset consisted of a total of n = 89 complete and valid interviews, which met all important requirements for analysis. The participation was voluntary, anonymous, and no compensation was provided. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and participants were informed about the study’s purpose and gave informed consent by proceeding with the survey. Data analysis was performed using SPSS software (Version 28.0).

The questionnaire consisted of a total of 58 questions, and was divided into five main topics. In the first part, respondents were asked questions about sociodemographic variables, which were intended to provide a comprehensive picture of the social and demographic characteristics of the participants. The questions covered topics such as age, gender, educational attainment, employment status, country of employment, and field of work. The second part of the questionnaire focused on workplace characteristics and job requirements, focusing on the basic characteristics of the workplace environment, tasks expected, effort required during work, and the expected performance. This section contributed to understanding the stress factors in the workplace environment. The third part served to assess psychological capital (PsyCap), which was measured using a 24-question questionnaire. Responses were on a 6-point scale (e.g., “Right now I see myself as being pretty successful in training”, where 1 is “strongly disagree” and 6 is “strongly agree”). The fourth part of the questionnaire focused on the assessment of workplace stress. Workplace stress was measured using 10 questions (responses on a 5-point scale), taken from a questionnaire designed to assess general stress perception and adapted to the workplace environment. This part allowed respondents to report on the level of stress they perceived in their work and its sources (e.g., “Over the last past month how often have you felt that you were unable to fulfill all of your obligations?” where 1 is “never” and 5 is “very often”). The final section examined experiences of workplace bullying, conflict situations, and deviant behavior. The questions focused on how often respondents had experienced workplace bullying and the nature of the conflicts they had experienced (responses on a 5-point scale, e.g., “Have you experienced threats of violence at work in the last 12 month?” where 1 is “never” and 5 is “yes, on a daily basis”). Overall, the structure of the questionnaire provided a comprehensive picture of the participants’ workplace experiences, personal and psychological resources, and perceived levels of workplace stress and conflict.

The measures used in the research were PsyCap, workplace stress, and workplace bullying. PsyCap was measured using the Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ) developed by Luthans, Avolio, and Avey. The PCQ measures the four main components of PsyCap: hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism. It contains six statements for each component, for a total of 24 items. Respondents were able to indicate their agreement with each statement on a 6-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater PsyCap. The questionnaire was available in both Hungarian and German translations, ensuring easy accessibility in a language that respondents could understand.

A shortened version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) was used to measure stress at work, adapted into Hungarian by Stauder and Konkolÿ [

33]. Although the PSS-10 was not originally designed specifically for a workplace context, the questionnaire emphasizes the need for respondents to relate the questions to their work situation. The PSS-10 was chosen because of its brevity and simplicity: another instrument on psychosocial factors at work, the 92-item version of the Copenhagen Questionnaire on Psychosocial Factors at Work II (COPSOQ II), proved to be too long and difficult to access for open use. However, a subset of the COPSOQ II questionnaire was used to measure workplace mobbing and conflict and violence behaviors. This instrument has also been used in previous Hungarian surveys, such as the 2013 survey mentioned in the literature, which found that 40% of employees had experienced workplace bullying [

15]. We asked respondents how frequently they experienced harassment or bullying behaviors at work (with options ranging from never to daily). For analysis, we classified respondents into those who have experienced mobbing (at least occasionally) versus those who have not, or considered the frequency distribution as an outcome. The detailed questions of the COPSOQ II (e.g., “

Have you been subjected to bullying at work?” or “

How often do you experience conflicts with colleagues?”) were found to be suitable for detecting the occurrence of workplace conflicts and bullying incidents, thus fitting the objectives of the research to measure the level of workplace bullying. However, it is important to note that the COPSOQ II questionnaire was only available for free use in Hungarian; only the first edition of the German version was available, which did not yet include questions on measuring conflict and bullying behaviors. Therefore, in this case, in the German version, these questions have been translated by the researchers. For all three questionnaires, we used the scientifically validated translation forms (Hungarian and German), if any were available and published.

2.2. Sample Characteristics

After data cleansing, out of a total of N = 89 valid cases, 89 persons could be clearly classified into the predefined gender categories (male, female, other). Slightly more than half of the valid cases, 51.7%, were male, while 48.3% were female and 0% were other. Thus, in terms of the sex ratio of the respondents, the survey provides a relatively balanced sample. Descriptive statistics show that the age range of the respondents is between 19 and 63 years. The mean age is 40.3 years, the standard deviation is 13.29 years, and the median is 40 years. Furthermore, the spread between age groups is 44 years. Looking at the generational distribution of the sample, it can be observed that generations Z and X are represented in relatively similar proportions and together form a majority (Generation X: 36%, Generation Z: 33.7%). In contrast, Generation Y is represented by 21.3% and the baby boomer generation by 9%. The distribution of respondents by country of employment shows that the majority work in Germany (n = 38) and Hungary (n = 37). The largest proportion of respondents in the sample, 42.7%, identified Germany as their place of work. Hungary represents the second largest group, with 41.6% of respondents working there, just behind Germany. Austria has a smaller group of 15.7% of respondents (n = 14), indicating that, although it is present in the sample, its share is much smaller than the previous two countries.

The mean of PsyCap in the overall sample is 4.64, indicating a high level of PsyCap (6-point Likert scale), and the median value, reflecting the central trend, is 4.66, showing a concentration of values around the mean, indicating that most individuals have a similar level of PsyCap. The overall range of values is 3.29, i.e., the data are distributed between a minimum value of 2.62 and a maximum value of 5.9. The variance is 0.496 and the standard deviation is 0.70, indicating a relatively small dispersion; individuals’ PsyCap levels differ from the mean by a moderate but appreciable amount. In terms of the percentage distribution of the overall sample, the data show that 9% of participants fall into the low PsyCap category, which represents eight participants. The moderate PsyCap level is the most frequent category, with 49.4% of participants, or 44 people, falling into this category. The high PsyCap category includes 41.6% of the sample, for a total of 37 participants. The distribution clearly shows that moderate PsyCap levels dominate, while the proportion of participants with low PsyCap levels is the smallest. The high PsyCap level also represents a significant proportion of the sample, but is below the prevalence of the moderate category.

A comparison of PsyCap at the national level reveals the following: in Germany, 10.5% of respondents have low PsyCap; in contrast, around 45% of respondents have moderate PsyCap, while a further 45% have high PsyCap. In the analysis of the Austrian questionnaire sample, no respondents with low PsyCap were found. The survey results show that 57.1% have moderate PsyCap, while 42.8% have high PsyCap. For Hungarian respondents, the survey showed that about 11% have low PsyCap, 51% moderate, and 38% have high PsyCap. It is important to note that the different distributions of PsyCap observed in different countries needs further research, as various cultural, economic, and social factors may lie behind the differences. Due to the small number of groups (Germany n = 38, Hungary n = 37, but, most importantly, Austria n = 14,), we cannot make representative statements about the generalizability of the results, and it is therefore important to aim for larger samples in further studies. Further research may help to explore why these countries show different patterns in levels of PsyCap and how these factors affect individuals’ lives and social status.

When analyzing the sample in terms of perceived stress at work, overall, 15.7% of respondents experience high levels of stress, while 40.4% experience moderate stress, and 39% experience low stress levels. These data indicate that the distribution of workplace stress is relatively even, but that high and moderate stress levels affect a significant proportion of respondents. The statistical data indicate that the average workplace stress level is 2.73, indicating a moderate level (5-point Likert scale). The median is 2.6, meaning that half of the respondents experience lower stress levels and half experience higher stress levels. A standard deviation of 0.622 and a variance of 0.387 indicate that stress levels are closely around the mean. The spread is 3.1, the minimum is 1.5, and the maximum is 4.6, reflecting the most extreme stress levels. These results highlight that workplace stress levels span a wide spectrum. Although a significant proportion of respondents experience moderate stress, the proportion of respondents who perceive high levels of stress is also noteworthy. Here again, it is important to note that further research is needed to gain a deeper understanding of what other factors influence levels of stress at work.

A comparison of workplace stress at national level reveals that, in Germany, 47.3% of respondents experience low levels of workplace stress, 36.9% report moderate levels of stress, and 15.8% experience high levels of stress. In Austria, 21.4% of respondents experience low, 57.1% moderate, and 21.4% experience high levels of stress at work, indicating a predominance of moderate stress. In Hungary, 48.6% of respondents report low stress, 37.8% moderate, and 13.5% report high work stress. Combining the levels of moderate and high work stress, some differences between the countries emerge. In Germany and Hungary, roughly half of the respondents experience low levels of work stress, while the other half experience moderate or high levels of stress. In Austria, on the other hand, the vast majority of respondents report medium or high levels of stress at work, while low levels of stress are only reported by a minority. The data show that higher levels of work stress predominate in Austria, while Germany and Hungary have a more balanced proportion of lower and higher stress levels.

To determine the internal consistency of the PsyCap variable, I conducted a Cronbach’s alpha analysis consisting of 24 questions in total. The resulting high Cronbach’s alpha value (α = 0.886) indicates that the scale has excellent internal reliability. This result indicates that the correlation between the questions is strong and that the items reliably measure aspects of PsyCap. The structure of the instrument for measuring PsyCap is further analyzed using factor analysis. Both the Bartlett’s test (chi-square (210) = 1063.89, p < 0.001) and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) sample adequacy index (KMO = 0.891) indicate that the variables are appropriate for factor analysis. The results showed that five factors had eigenvalues greater than 1.0, but excluding recoded items, a four-factor model emerged, explaining 64.32% of the variance. This structure is thus already consistent with the four subscales often used in the literature on PsyCap, which represent the main components of PsyCap. The four-factor solution observed in the analysis confirms the theoretical model that the four dimensions of PsyCap are distinct yet collectively contribute to the activation of an individual’s internal resources.

Based on the results of the research, the distribution of PsyCap, workplace stress, and mobbing experiences showed different patterns across generations and genders. Members of the baby boomer generation had higher levels of low PsyCap and high stress, while Generation Z was characterized by moderate PsyCap. Women reported higher rates of mobbing experiences, especially in its regular forms. These results emphasize the need for group-specific approaches to workplace well-being and PsyCap development, especially considering the different needs of different generations and genders. This difference may contribute to more effective management of workplace stress and the prevention of mobbing, especially among older generations and women, who, according to the sample, are most affected by these phenomena.

3. Results

We assumed that there is a negative correlation between psychological capital (PsyCap) and perceived job stress (H1). The statistical analysis showed that there is indeed a negative correlation between PsyCap and perceived work stress (see all correlation data in

Table 1). The results of Spearman’s correlation analysis confirm this hypothesis, as the obtained correlation coefficient (r = −0.573) indicates a significantly strong negative correlation between PsyCap and perceived job stress. This relationship suggests that individuals who have higher PsyCap tend to experience lower levels of stress at work, which is consistent with and supports findings in the literature. However, it is important to stress that the observed relationship is only correlational and not causal. Correlation suggests that there is a relationship between the two variables but does not prove that one variable directly influences the other. Although a negative relationship between higher PsyCap and lower job stress can be detected, this does not mean that an increase in PsyCap automatically leads to a decrease in stress. It is possible that a third factor, such as job support or other environmental influences, or even mobbing, which will be examined in more detail later, could jointly influence both variables. Equally, it is also possible that the direction of the correlation is inverted and that, in fact, a reduction in job stress contributes to an increase in PsyCap. This could suggest that those who experience lower stress in their workplace are more likely to have higher PsyCap; however, the correlation in this form does not confirm a causal relationship. Therefore, further research is needed to explore the exact direction of the relationship between the variables and possible underlying causes.

We also assumed that there is a positive correlation between job stress and experiences of workplace bullying/bullying (H2). There is a clear positive correlation between stress at work and the experience of workplace bullying or teasing. Workplace stress was significantly positively correlated with mobbing experiences (Spearman’s r = 0.323,

p = 0.002), indicating that higher stress levels are associated with greater reported exposure to workplace bullying. This finding is also in line with previous research on workplace environments, which suggests that increased stressful situations may contribute to increased conflict and the emergence of workplace mobbing phenomena [

34,

35]. Workplace stress, especially high levels of stressful situations, often create an environment that fosters negative interactions and tension between competitors. These factors may contribute to the development of mobbing because, in stressful environments, people may be more prone to aggressive or oppressive behavior, with the consequence that victims of mobbing often perceive threat and exclusion [

36]. However, it is also worth noting that the correlation is not one-way. The reverse direction is also plausible, as mobbing can also have a negative impact on workplace stress levels. Individuals who are victims of mobbing often experience an increase in workplace stress as the constant harassment and bullying takes a psychological toll on them, leading to stressful situations. It is therefore important to consider the complexity of the relationship and how both factors can interact. In the correlational analysis of the three hypotheses under consideration, it is therefore important to stress once again that the observed relationships are only correlational, which means that they do not prove causality. For example, the negative correlation between higher PsyCap and lower job stress does not imply that an increase in PsyCap automatically leads to a decrease in stress. A third factor, such as job support, may also influence both variables. Moreover, the direction of the correlation may be inverted, i.e., a reduction in job stress may contribute to an increase in PsyCap. These factors highlight the limitations of correlational analyses, and further research is needed to better understand the relationship between the variables and to explore causality.

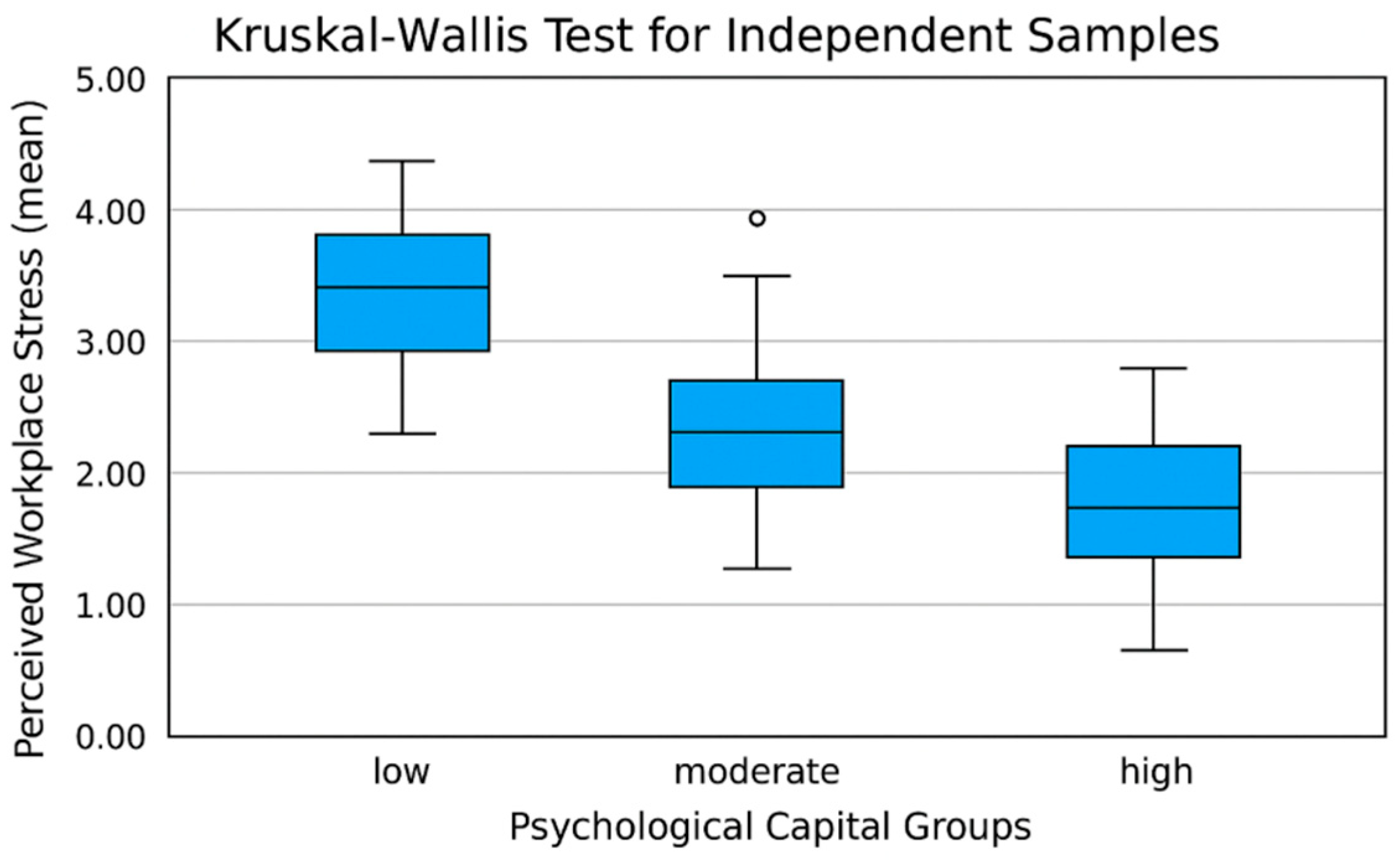

According to our third hypothesis (H3), there is a significant difference between groups with high, medium, and low PsyCap in terms of perceived work stress (see the distribution data in

Table 2). In the research, we created the categories according to the questionnaire’s scores (1–2: low, 3–4: medium, 5–6: high). The assumption was that individuals with high PsyCap are more likely to cope with stressful situations at work. In contrast, individuals with low PsyCap may be more vulnerable to workplace stress. To decide which test was appropriate for comparing means, it was first necessary to examine the normal distribution of the data. Since both the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and the Shapiro–Wilk tests showed significant results for the group with moderate PsyCap, it was assumed that the data did not follow a normal distribution. Therefore, non-parametric methods were used for further analyses.

Both tests (Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk) reject the null hypothesis and assume that the assumption of a normal distribution cannot be accepted. The groups in the sample do not follow a normal distribution for the two constructs: PsyCap and job stress. Since the parametric test conditions are not met and more than two groups (low, moderate, and high PsyCap levels) need to be compared, the Kruskal–Wallis test can be used for further analysis. The result of the Kruskal–Wallis test was asymptotically significant (

p < 0.001), allowing the null hypothesis to be rejected. This result suggests that there are significant differences in the level of perceived workplace stress between groups with different levels of PsyCap: low, medium, and high PsyCap (H(2) = 24.551,

p < 0.001, Eta

2 = 0.262). This indicates that the level of PsyCap has an impact on the perceived workplace stress of individuals and that different levels of PsyCap may be associated with different perceptions of stress. To further examine the results, I used pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction to identify which groups had significant differences. The results of the post-tests showed a significant difference in perceptions of workplace stress between the high and low PsyCap groups (z = 4.804,

p = 0.000). An effect size of r = 0.71 is considered a strong effect based on Cohen’s (1992) guidelines, suggesting that individuals with high PsyCap experience significantly lower levels of workplace stress than those with PsyCap. In addition, significant differences were also found between moderate and low PsyCap groups in terms of job stress (z = 3.338,

p = 0.003). The effect size r = 0.46 again indicates a strong effect, indicating that even moderate levels of PsyCap are associated with significantly lower perceptions of job stress than low PsyCap levels. When comparing the high and medium PsyCap groups, there was also a significant difference in perceptions of job stress (z = 2.646,

p = 0.024), although this is a medium effect based on the r = 0.29 effect size. This indicates that, although higher levels of PsyCap also show an improvement compared to the medium level, a more moderate effect is observed here (see the data in

Figure 1 and

Table 3).

These results support the idea that levels of PsyCap are strongly associated with perceived levels of workplace stress, and that individuals with higher levels of PsyCap tend to experience less workplace stress. Thus, the results so far show that PsyCap plays a significant role in the perception of stress at work.

4. Discussion

The aim of the study was to explore the relationship between psychological capital (PsyCap), perceived work stress, and experienced workplace bullying. Our results largely support the proposed hypotheses. First, as predicted, PsyCap was strongly associated with lower stress (H1). Second, higher stress coincided with a higher incidence of workplace bullying (H2). Third, employees’ stress levels differed according to their PsyCap levels, with those having low PsyCap experiencing considerably more stress than those with moderate or high PsyCap (H3). These findings reinforce the notion that PsyCap is a protective resource and that stressful environments are linked to negative social outcomes like mobbing. We also explored whether PsyCap buffers the effect of mobbing on stress; this moderation was not clearly supported by our data, suggesting the relationship between stress and bullying holds across various levels of PsyCap.

Previous research pointed out positive correlation between PsyCap and organizational commitment [

37]. There are important results on workplace mobbing, workplace stress, and PsyCap, which are in line with the findings of this research, although moderating or mediating effects are not clear yet [

38,

39,

40]. The most strongly supported function of PsyCap in the literature is that it acts as a basic set of personal resources. On the one hand, as an antecedent, it can reduce the likelihood of becoming a target of mobbing; on the other hand, as a mediator, it plays a key role in the causal chain between mobbing and ill-being. Harassment depletes PsyCap, and this loss of resources leads to negative health consequences. The findings highlight the importance of organizations addressing the prevention of mobbing and the enhancement of PsyCap, both of which can contribute to improving well-being in the workplace [

10,

22,

30]. The significant negative correlation observed in this research between PsyCap and perceived workplace stress clearly indicates that PsyCap is an important protective factor in managing workplace stress. The Kruskal–Wallis test used in this study, which compares groups with different levels of PsyCap, revealed significant differences in the level of perceived job stress. Our results suggest that even moderate PsyCap plays a significant role in reducing perceptions of stress at work. The largest stress reduction was observed between low and moderate PsyCap groups (as evidenced by a large effect size r = 0.46), whereas improving from moderate to high PsyCap yielded a smaller additional benefit (medium effect r = 0.29).

Our research also investigated the relationship between workplace bullying and PsyCap, with a particular focus on how bullying affects levels of workplace stress. The results showed no significant difference between PsyCap in work environments that experience mobbing and those that do not. However, the data showed a slight trend: those who did not experience mobbing had slightly higher PsyCap, but the differences did not reach statistical significance. The small number of items in the group of those who regularly experienced mobbing (n = 5) may have limited the precision of the statistical analysis, and thus this sample may have also limited the reliability of the results. In future research, it would be important to include larger samples to explore a wider spectrum of experiences of mobbing. Although the research did not reveal any significant differences, the observed trend suggests that efforts to prevent mobbing and create a positive workplace environment are essential in strengthening PsyCap.

As for the limitations of the research, while it is important to show significant associations between PsyCap, work stress, and mobbing, the correlation method is not suitable for drawing firm conclusions about which factor causes the other. Thus, the analysis does not answer the question of whether high PsyCap reduces stress and susceptibility to mobbing, or vice versa, i.e., whether reducing stress and preventing mobbing results in higher PsyCap. The cross-sectional research design is also a limiting factor. Data collection at a single point in time does not allow for the examination of dynamic, long-term effects of changes over time, such as PsyCap and workplace stress. Without longitudinal studies, i.e., studies over a longer period, it is difficult to determine how levels of PsyCap change as a function of changes in workplace stress and mobbing, and vice versa. This would be particularly important for a deeper understanding of the relationship between mobbing and PsyCap. An additional limitation is the sample size, in particular the low number of respondents who regularly experience mobbing (n = 5) or the number of cases in Austria (n = 14), which reduces the statistical reliability of the results. In particular, the small sample size of Austria caused precision problems in the cross-country comparison, which makes the results less reliable for this country. The use of self-report methods also presents limitations, as respondents provide their answers based on their own subjective experiences. This type of measurement is often subject to biases that may arise from respondents’ personal perceptions, self-evaluation tendencies, or even social conformity pressures. This can be particularly relevant when assessing workplace stress and mobbing, as these phenomena trigger emotional reactions and often have significant subjective components. The perceived frequency and intensity of work-related stress and mobbing may differ from objective reality due to possible biases resulting from self-reporting. In summary, the main limitations of the research include the lack of ability to establish causal relationships from cross-sectional and correlational studies, the small sample size, especially for some countries and groups, and the potential for bias from self-report methods. Future research would benefit from longitudinal studies and larger and more representative samples to explore more deeply and accurately the links between PsyCap, workplace stress, and mobbing.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that psychological capital (PsyCap) is a significant protective factor against workplace stress and that stressful environments are linked to a higher incidence of mobbing. Employees with higher PsyCap report lower stress levels, with even moderate PsyCap conferring substantial benefits compared to low PsyCap. While PsyCap did not moderate the relationship between mobbing and stress, its consistent association with lower stress highlights its value as a core resource for employee well-being. The findings underscore the importance of organizational strategies that both prevent mobbing and actively develop employees’ PsyCap through training, leadership support, and resource-building initiatives. Such dual interventions have the potential to foster healthier work environments, reduce stress, and strengthen resilience across diverse occupational settings.

Future research should also investigate other aspects, such as the different forms of mobbing and their impact on PsyCap, and the role of workplace support systems in employee well-being. In addition, the moderation analysis revealed that the interaction of PsyCap and mobbing had a significant effect on perceived workplace stress levels, but PsyCap did not prove to be an effective moderator of the relationship between mobbing and perceived stress. This indicates that, although PsyCap and mobbing may jointly influence perceived stress, PsyCap is not a direct moderating factor in this relationship. In the cross-country comparison, there were no significant differences in the level of PsyCap between Germany, Austria, and Hungary. However, the prevalence of mobbing was found to be more intense in Hungary: while 76.4% of respondents had not experienced mobbing, the regular occurrence of the phenomenon, on a monthly, weekly, or daily basis, was found to be significantly more frequent in Hungary than in Germany and Austria. The results of the survey show that the phenomenon of workplace mobbing is not only present in Hungary, but also more frequent, highlighting the need for measures to prevent and tackle mobbing. The findings highlight that the long-term effects of mobbing, especially on PsyCap and workplace stress, need further investigation and that further research is needed to gain a deeper understanding of the relationship between mobbing and PsyCap in order to develop more effective intervention strategies in the future.

As this survey raised many questions in connection with the causal structure of the examined phenomena, further research is necessary. More longitudinal studies are needed to explore causal relationships. The bidirectional relationship identified by meta-analyses (poor mental health increases the risk of harassment) requires further clarification, as does the monitoring of the long-term effects of interventions. Further research is needed to explore how the type of harassment (work- versus person-focused) and its sources (manager versus colleague) interact with PsyCap, and how these dynamics differ in high-risk occupations (e.g., healthcare, law enforcement, hospitality).