1. Introduction

Located east of the Anacostia River, Washington, D.C.’s Ward 8 is a historically marginalized and predominantly Black community, where 88.06% of residents identify as African American. Despite enduring structural inequalities, including high poverty rates, elevated unemployment, and chronic disinvestment, homeownership remains a marker of resilience. Approximately 23% of homes are owner-occupied, and the median home value is nearly 50% lower than the citywide average (USD 724,600) [

1,

2]. In recent years, a growing population of Black middle-class homeowners has begun to reshape the local landscape, contributing to a complex narrative of socioeconomic change within this racially homogeneous, yet economically diverse, ward.

Ward 8’s historical experience of redlining, spatial exclusion, infrastructure neglect, and inequitable redevelopment continues to shape both the built environment and public perceptions. Throughout the 20th century, Black residents were disproportionately affected by federally sanctioned housing policies, including redlining, racially restrictive covenants, and discriminatory mortgage lending. These exclusionary practices not only reinforced residential segregation but also denied Black families the opportunity to build intergenerational wealth through homeownership [

3].

Although neighborhoods such as Anacostia and Congress Heights have recently attracted public and private investment, revitalization efforts often prioritize new residents while overlooking longstanding disparities. Ward 8 remains stigmatized by narratives of crime, poverty, and health inequity [

4,

5,

6]. However, despite systemic barriers, Black homeownership persists as a symbol of community resilience and upward mobility.

Understanding this historical and spatial context is essential for examining how Black middle-class homeowners in Ward 8 perceive and engage with civic institutions, including public libraries. Rather than framing this study through the lens of gentrification or upward class mobility alone, it proceeds from the foundational premise that Black residents in Ward 8 are not a monolith. This research interrogates how intragroup class distinctions, particularly identification with or divergence from the Black creative class (BCC), shape relationships between individuals and public institutions.

Public libraries, historically civic spaces [

7,

8], have long been rooted in middle-class values surrounding knowledge, cultural participation, and self-development [

9,

10]. These values influence not only how libraries design their programming and outreach strategies but also how various social groups perceive libraries as relevant, trustworthy, or culturally resonant. Similarly, “librarians share concerns about the erosion of civic engagement and participation in our communities” and “libraries are places essential to the political processes of democracy; places that reinforce the notion of association” [

11] (p. 75). Public tax-supported libraries were established in the mid-19th century as supplements to public schools, as well as “civilizing agents and objects of civic pride in a raw new country.” Later in the century, public libraries continued “the educational process where the schools left off and by conducting a people’s university, a wholesome, capable citizenry would be fully schooled in the conduct of a democratic life.” By the 1920s, libraries had become recognized as informal education centers where all could gain access to the ideas necessary for self-governance [

11] (p. 79).

This study challenges stereotypical and one-dimensional assumptions about racially homogeneous communities by revealing how internal class diversity within the Black middle class influences patterns of institutional engagement, specifically with public libraries. By emphasizing intersectionality and symbolic capital, it advocates for more detailed research methods and institutional practices. For libraries, the findings underscore the importance of conducting community analyses to identify the diverse characteristics and needs within a community [

12]. Community analysis, in simple terms, involves understanding the community being served; this information helps libraries plan their services and programs, whether civic or otherwise. Therefore, library community analysis involves examining two aspects: community characteristics and the significance of these characteristics [

13] (p. 451). Libraries use this data to enhance and provide culturally relevant programming and civic platforms, prevent uniform access patterns, and foster greater interest and trust in institutions. There is a logical nature between the practice of community analysis and culturally relevant program development for communities like Ward 8. However, this operational approach questions whether data-informed decision-making provides a comprehensive and adequately tailored approach to differentiating programs across the spectrum of backgrounds, experiences, socioeconomic statuses, and interests that exist within racially homogeneous communities.

Starr and Keller [

14] argue that empirical evaluation of library program effectiveness in Black communities is limited. While frameworks such as community analysis are useful, they often fail to capture how intersectionality and intragroup diversity shape engagement. The history of Black people in America and libraries is long and deeply significant, shaped by slavery, segregation, the civil rights movement, desegregation, and more recent moments, such as the Ferguson and Baltimore protests. These historical and contemporary struggles also provide an assets-based narrative, one that underscores the civic importance and symbolic meaning of libraries in Black communities [

15,

16]. Consequently, research that attends to the intersections of race, socioeconomic class, education, and identity in relation to library engagement is not only a contribution to the literature but also a necessary and timely intervention.

Problem Statement and Hypothesis

This study is grounded in the proposition that Black homeowners in Ward 8, while racially homogenous and collectively situated within a shared geographic and institutional context, are not a monolithic group. Instead, they reflect diverse class-based identities and cultural orientations that may shape how they engage with public institutions, including libraries. To explore these dynamics, the study adapts Elfreda Chatman’s Small World Theory [

17] and Richard Florida’s creative class framework [

18] to conceptualize Ward 8 as a spatially bounded environment in which shared institutional exposure (e.g., to public services, schools, and libraries) may influence patterns of engagement, even in the absence of strong interpersonal ties among residents.

At the center of this inquiry is the role of BCC identity, a sociocultural construct marked by higher education, salaried employment, and homeownership. This identity is shaped by access to cultural capital and reflects class-specific worldviews that may affect how residents interpret or participate in public life. The research question guiding this investigation is: How does educational attainment influence BCC identity, and what role might that identity play in shaping public library engagement among Black homeowners in Ward 8, Washington, D.C.?

Based on this framework, the study hypothesizes that Black homeowners with higher levels of education are more likely to identify as part of the BCC. This status may inform how they view and use public libraries within their social and cultural world.

2. Theoretical Framework

This study builds upon three theoretical frameworks to illustrate the relationship between Black middle-class homeowners in Ward 8, Washington, D.C., and their engagement with public libraries in their quadrant. First, Elfreda Chatman’s Small World Theory explains how individuals’ information behaviors are shaped by the boundaries of their immediate social worlds, where shared norms and routines constrain access to outside perspectives [

17]. Second, Richard Florida’s Creative Class framework identifies a class of professionals (e.g., scientists, artists, engineers, and information technologists), whose creativity and innovation are said to drive economic growth [

18]. Last, Kimberlé Crenshaw’s Intersectionality framework shows how overlapping systems of race, class, and gender generate distinct forms of privilege and marginalization, emphasizing that, even within racially homogeneous groups, class and social position produce divergent experiences [

19].

Individually, these theories provide valuable but partial insights. Chatman highlights the importance of spatial and institutional proximity but does not capture internal class variation. Florida centers class identity but overlooks how race and structural barriers limit access to creative-class membership. In addition, critics highlight that Florida’s model reinforces neoliberal urban agendas, contributes to gentrification, and maintains inequality by privileging occupational categories tied to elite segments of the economy [

20]. However, this study incorporates Crenshaw’s perspectives, as it emphasizes intra-group variation, demonstrating that race alone cannot explain institutional engagement when class and gender stratification operate simultaneously [

19,

21]. Taken together, the three frameworks offer a multi-dimensional perspective: Chatman explains spatial and institutional constraints, Florida frames symbolic class identity, and Crenshaw reveals how race and class intersect to produce variation within a racially uniform community.

This study adapts these theoretical frameworks to reflect the lived experiences of Black homeowners in Ward 8:

- 1.

Small Spatial World™ (adapted from Chatman): Rather than focusing on interpersonal ties, this framework emphasizes how shared geography and institutional exposure (e.g., proximity to libraries) shape engagement patterns;

- 2.

Black Creative-Class Identity (adapted from Florida): In response to critiques of Florida’s narrow occupational definition, creative-class identity is reconceptualized as a symbolic identity rooted in higher education, homeownership, and salaried employment. This adaptation foregrounds cultural capital markers as meaningful signals of belonging within a marginalized urban community. While Florida’s model excludes ‘working-class creative’ occupations, this study does not collect data on participants’ specific occupations and does not assume they are working class. Instead, the adaptation emphasizes markers of middle-class identity, homeownership, education, and salaried employment as symbolic signals of belonging within a marginalized urban community;

- 3.

Intersectionality (adapted from Crenshaw): Applied to highlight how intra-group differences in education, income, and class position stratify institutional trust and engagement, even among Black homeowners who share racial identity and neighborhood context. Intersectionality’s unique contribution here is its ability to capture variation within a racially homogeneous group, something neither Chatman’s nor Florida’s frameworks directly address.

Role of Cultural Capital and Creative Class Among Black Homeowners

Bourdieu [

22] describes cultural capital as existing in three forms: embodied (lasting dispositions of the mind and body, such as language, aesthetic preferences, and social manners), objectified (material cultural items like books, artworks, or technology), and institutionalized (formal credentials or professional qualifications). In this study, cultural capital refers to the skills, education, and dispositions that help individuals navigate institutional systems and establish legitimacy within them. While both concepts acknowledge the importance of education and skills, cultural capital functions as an underlying resource that reinforces or supports creative-class identification, whereas BCC identity captures the symbolic and social aspects of class identity in a specific racial and spatial context.

Florida’s original creative class framework emphasizes professional occupational categories whose creativity and knowledge production are viewed as key drivers of economic growth [

23,

24,

25]. This study parallels that emphasis by treating education, homeownership, and salaried employment as symbolic markers of belonging for Black homeowners in Ward 8 [

26]. However, rather than relying on occupational role alone, cultural capital is used as a measurable foundation that supports BCC identification while also shaping institutional trust and engagement.

This approach also responds to limitations in Florida’s framework. Human geographer Oli Mould [

27] critiques the concept of “creativity,” arguing in

Against Creativity that it is often used as a buzzword and exclusionary marketing tool by corporations, politicians, and civic leaders to boost productivity, consumption, and economic growth, while also deepening social inequality and the gentrification of urban areas. In contrast, this study focuses specifically on Black middle-class homeowners in Ward 8, emphasizing how education, homeownership, and salaried employment shape institutional engagement in a historically marginalized space [

28,

29]. By incorporating cultural capital, the framework ensures that symbolic and educational resources, rather than occupational categories alone, define BCC identity. In this way, the framework parallels Florida’s linkage of creativity and class while extending it to capture the racialized and spatial realities of Black homeowners in Ward 8.

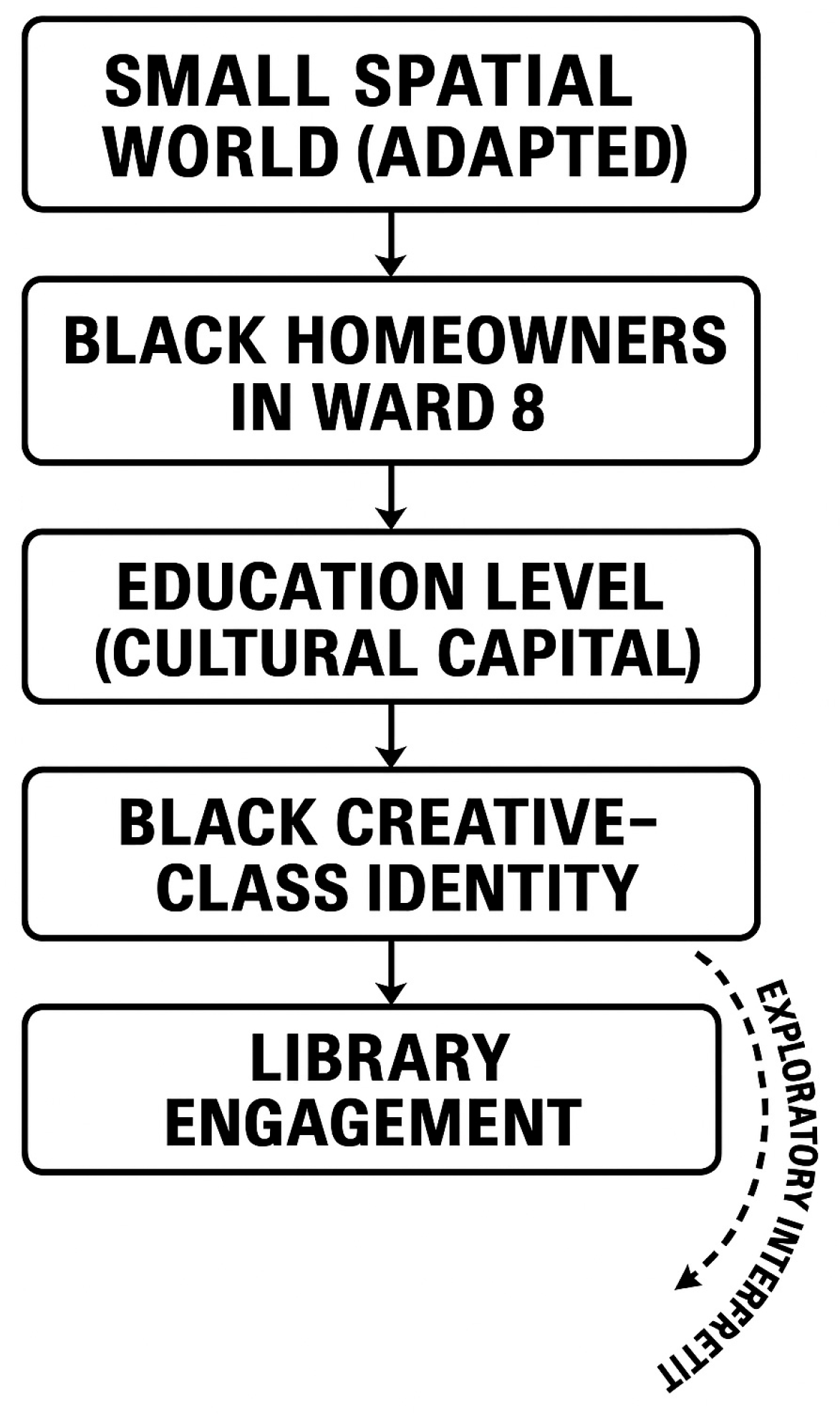

The adapted frameworks directly informed the study’s hypotheses. Educational attainment, conceptualized as cultural capital (Bourdieu, Florida), was modeled as a predictor of BCC identity, which, in turn, was modeled as a predictor of public library use (Chatman, Florida). These relationships are depicted in the conceptual model (

Figure 1), illustrating how educational attainment, creative-class identity, and library use are interconnected. Within this framework, the adapted Small Spatial World emphasizes geographic and institutional proximity, BCC identity highlights symbolic class belonging rooted in education and homeownership, and cultural capital provides the measurable foundation linking these dimensions. Together, these elements demonstrate how education and class identity intersect to shape library engagement among Black homeowners in Ward 8.

In

Figure 1, the conceptual framework incorporates an adapted version of Chatman’s Small World Theory, now reframed as Small Spatial World, along with Florida’s creative class and Crenshaw’s intersectionality frameworks. It demonstrates how educational attainment, as a form of cultural capital, affects the development of BCC identity. The model includes an exploratory interpretation of how class identity may shape wider patterns of library engagement.

3. Literature Review

The historical relationship between Black communities and public libraries spans decades of barriers and motivations directly tied to systemic racism, exclusion, segregation, and the ongoing fight for information access and digital equity within library spaces. This literature review examines how persistent equity barriers and meaningful motivators shape patterns of library use among Black communities.

Generational mistrust of public libraries is rooted in historical exclusion and systemic inequities. Under Jim Crow, access was either denied outright or restricted to underfunded Negro branches, reinforcing racial caste systems and limiting access to information [

30,

31]. Although the Civil Rights Movement dismantled legal segregation, discriminatory attitudes and institutional biases persisted in more covert forms [

32]. In the years following, federal initiatives funded experimental libraries in marginalized Black and Brown communities to combat poverty and decentralize library authority. However, the eventual withdrawal of funding left unresolved political tensions between these communities and public libraries [

33].

These embedded beliefs of mistrust are reinforced when patrons encounter racial bias in service delivery, policies, or interpersonal interactions. Such experiences highlight the need for libraries to demonstrate trustworthiness and cultural competency rather than rely on marketing campaigns to build trust [

34,

35]. Libraries that maintain hard-nosed fines and fee policies in the name of equity enforcement often overlook the disproportionate burdens these pose on community members of color living with systemic socioeconomic inequities [

36]. Leadership decisions regarding branch placement, reduced operating hours, and program design that do not reflect community needs further restrict equitable access and statute the symbolic distancing between Black communities and library institutions that share a Small Spatial World [

17,

37].

Despite these entrenched challenges, libraries rooted in Black communities remain vital resources, capable of becoming trusted third places that address both information access and digital equity needs. The legacy of Historically Black Colleges and Universities’ libraries offers a powerful model, leaving a lasting imprint on the social, economic, and political service delivery approaches within Black communities. HBCU libraries provided both a competitive lens to White America literacy activities and strategic tools to organize against Jim Crow segregation [

15,

37,

38,

39]. Libraries that adopt community-designed services grounded in equity and informed by Critical Race Theory, drawing from the HBCU model, can more effectively meet the needs of patrons of color, particularly in bridging the digital divide [

40].

Beyond these broader patterns, historical case studies provide vital insights into the symbolic and cultural significance of libraries for African Americans. Research on Louisville’s segregated Negro branches demonstrates how, even under exclusionary conditions, Black librarians and patrons promoted civic engagement and created spaces of empowerment [

41]. Similarly, oral history studies remind us that libraries in Black neighborhoods have long been more than just buildings with books; they serve as civic anchors and cultural havens amid systemic inequalities [

42]. Therefore, focusing on culturally grounded and avoidant approaches to library engagement in historically marginalized Black communities is essential to strengthen the ability of libraries to serve as spaces of empowerment, belonging, and civic participation [

14].

Library spaces that authentically reflect Black history through collections, programs, and health and well-being services contribute to trust building and stimulate motivations for engagement [

43,

44]. Collectively, this body of research suggests that library engagement among Black communities is shaped less by individual socioeconomic status and more by how effectively institutions address historical inequities, foster cultural alignment, and provide resources that are both relevant and accessible.

4. Materials and Methods

This study used a quantitative survey to explore the relationship between education, income, and self-identified class identity and how Black homeowners in Ward 8, Washington, D.C., use public libraries. The research is based on an adapted version of Chatman’s Small World Theory, Florida’s creative class framework, and Crenshaw’s intersectionality concept. Chatman’s Small World Theory is reinterpreted here as a Small Spatial World, focusing on how proximity to shared institutional spaces influences behavior even without direct personal connections. Florida’s creative class framework is expanded to include indicators like homeownership, educational achievement, and salaried employment as markers of identity among Black middle-class homeowners. Crenshaw’s intersectionality further emphasizes how overlapping aspects of race, class, and education shape trust and engagement with institutions. These frameworks guided the survey design and analysis and the interpretation of results.

4.1. Research Design

This study employs a quantitative research design using a custom-developed survey instrument to examine the relationship between educational attainment, BCC identity, and public library use among Black homeowners. The instrument was designed to capture indicators of cultural capital, class-based self-identification, and binary library usage. The goal was to explore how internal class distinctions within a racially homogenous population shape patterns of institutional engagement.

The following research design section outlines the survey approach, participant recruitment, and analytic strategies used to operationalize these frameworks in examining library engagement.

4.2. Sample Population

The final sample comprises 56 Black homeowners residing in Ward 8, Washington, D.C. Of the 75 individuals who initiated the survey, only the completed responses (n = 56) were included in the analysis. The remaining 19 incomplete surveys were excluded.

The sample reflected variation in age, education, income, homeownership, and length of residency. These characteristics align with the common demographic markers of middle- and upper-income Black homeowners identified in previous research [

45,

46,

47], supporting the representativeness of the sample.

The eligibility criteria required the participants to (1) own and reside in a home located in Ward 8; (2) self-identify as Black/African American or Black/Two or More Races; and (3) provide informed consent. Those who did not meet these criteria were screened out. The resulting sample represents a targeted subset of Black homeowners whose responses support the study’s examination of class identity and institutional behavior.

4.3. Survey Design and Instrumentation Development

A validated survey instrument specifically capturing the intersection of race, creative-class identification, and public library use was not available. Therefore, a custom survey was developed for this study. The survey consisted of closed-ended questions designed to capture demographic variables (e.g., age, race, income, and education), creative-class identification, and how often they engage with public libraries. Grounded in Chatman’s Small World Theory, Florida’s creative class framework, and Crenshaw’s intersectionality, an 8-item binary-response survey was constructed to operationalize key independent, dependent, and control variables [

48]. To adapt Florida’s framework to this racial and spatial context, “creative-class identity” was measured in two ways: (1) through symbolic and demographic indicators, such as education, professional employment, homeownership, and residence in Ward 8, and (2) through an explicit self-identification question in which participants were asked directly, “Do you identify as part of the Black creative class as defined by this research?” This dual approach allowed the survey to capture both objective cultural capital markers and participants’ subjective identification with the creative class, offering a more context-specific understanding of cultural capital among Black middle-class residents.

4.4. Reliability and Validation

The survey underwent multi-phase validation to ensure cultural relevance and conceptual alignment. Subject matter experts in LIS and Black urban life reviewed the tool for content validity. A literature review guided item development to maintain consistency with Chatman, Crenshaw, and Florida’s frameworks.

4.5. Measures

These measures support analysis of the relationship between creative-class identity and library use, while accounting for demographic variation.

4.6. Ethical Considerations

Given the sensitivity of studying race, class, and institutional behavior, the survey prioritized confidentiality and psychological safety [

49]. All responses were anonymous and securely stored. Participation was voluntary, and no identifying information was collected. The study received IRB approval and adhered to ethical protocols throughout.

4.7. Pilot Testing

Ten demographically similar individuals (but not residents of Ward 8) participated in a pilot test. Structured feedback improved the clarity, tone, and contextual relevance of survey items. Their input helped ensure that the final instrument accurately reflected the lived experience of Black middle-class homeowners in urban settings.

4.8. Recruitment

Participants were recruited through community listservs, word of mouth, and Ward 8 Advisory Neighborhood Commissions (ANCs). Materials included QR codes and links for accessibility. Ethical safeguards around anonymity and informed consent were upheld during all outreach efforts.

4.9. Data Collection

Goal-directed sampling was used to reach eligible Black homeowners in Ward 8. The survey was administered online over a four-week period.

4.10. Data Analysis: Model Assumptions and Statistical Power

Logistic regression was used to evaluate associations among variables. Diagnostic tests confirmed model stability:

A post hoc power analysis (statsmodels, Python 3.15.5) showed power = 0.75 (α = 0.05, Cohen’s h = 0.5). Although slightly underpowered, this is acceptable for exploratory studies involving hard-to-reach populations [

50].

4.11. Administration

The survey, titled the Black Homeowner Survey, was deployed via Qualtrics XM (Provo, UT, USA, 10 December 2024). It contained eight items (See

Table A1 for survey instrument): binary and single-response multiple-choice questions. Questions measured demographics, creative-class identity, and public library use. All items were structured to ensure consistent data entry and reliable analysis.

The survey design emphasized the structured collection of demographic information (including race, income, education, age, and class identity), enabling the detection of trends and variations in institutional behavior among Black homeowners [

51,

52].

4.12. Positionality Statement

As researchers, we recognize that our identities influenced the design, implementation, and interpretation of this study. The lead author, a Black homeowner with ties to Ward 8, brought insider knowledge and critical distance that guided the decision to focus on Black homeowners rather than renters. Owner-occupied homeownership was highlighted as the central theme of the study, representing both economic stability and long-term investment in neighborhood institutions and community life.

The second author is a library and information science scholar focusing on equity, diversity, and social justice. The second author’s role as a critical LIS researcher provided theoretical support and expertise, placing this work within larger discussions about information behavior and equitable access.

Together, our positionalities, one rooted in lived community experience and the other in scholarly expertise, influenced the framing of the research questions, the choice of theoretical frameworks, and the interpretation of findings. We acknowledge that research is never completely neutral, and our perspectives shaped the priorities we pursued and how the participant voices were understood.

5. Results

This section presents the descriptive and inferential statistical findings from a study of 56 Black homeowners living in Ward 8, Washington, D.C. Descriptive statistics describe the sample demographically. Conversely, inferential statistics are used to examine the relationships among creative-class identity, public library use, educational attainment, and household income through binary logistic regression models. As a reminder, creative-class identity in this study was measured both through symbolic and demographic indicators (education, professional employment, homeownership, and residence in Ward 8) and through participants’ explicit self-identification as members of the Black creative class, ensuring that the results reflect both objective markers and subjective identifications.

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

Participants ranged in age from 25 to 64 years, with a mean age of 48.87 years (SD = 13.07). Age distribution was centered around middle adulthood: 16.1% were between 25 and 34 years old, 23.2% between 35 and 44, 28.6% between 45 and 54, and 16.1% between 55 and 64. Educational attainment was high, with 20% of participants holding a bachelor’s degree, 30% a master’s degree, and 13% a doctorate or professional degree. The average education level, measured on a 1–6 ordinal scale, was 4.07 (SD = 1.52). Household income also reflected middle-to-upper-middle-class status. Approximately 36% of respondents reported annual household incomes between USD 100,000 and USD 199,999, and 16% reported incomes exceeding USD 200,000. The mean income level on a 1–7 scale was 3.21 (SD = 1.65). Collectively, these characteristics are consistent with the socio-demographic profile of the BCC, as defined in the study’s adapted conceptual framework. Refer to

Table A2 and

Table A3 for details on continuous variables and respondent percentages by category.

5.2. Creative-Class Identification

Of the 56 participants, 46 individuals (82.1%) self-identified as part of the BCC, while 10 individuals (17.9%) did not. This distribution reflects the predominance of creative-class identification within the sample, consistent with its educational and professional profile.

5.3. Library Use

Regarding public library use, 31 participants (55.4%) reported using the library at least occasionally, while 25 participants (44.6%) indicated that they never used the library. These figures formed the basis for the binary dependent variable used in regression analysis.

5.4. Inferential Statistics

Binary logistic regression was employed to evaluate three models, each testing a theoretically grounded relationship between key variables. Listwise deletion was applied as needed for missing data; the full sample size (n = 56) was retained across all analyses.

5.5. Model 1: Creative-Class Identity → Public Library Use

This model corresponds to Hypothesis 1, which expected that Black homeowners who identify with the creative class would be more likely to engage with public libraries. Creative-class identity served as the independent variable, and public library use (yes/no) was the dependent variable. The results indicated that creative-class identity was not a statistically significant predictor (B = 0.262, SE = 0.699, z = 0.375, p = 0.707, 95% CI [−1.107, 1.632]). The odds ratio (OR = 1.30) suggested that individuals who identified with the creative class had 30% higher odds of using public libraries compared to their counterparts. However, the effect was not statistically significant. Model fit was poor, with a pseudo-R2 of 0.0018, an AIC of 80.85, a BIC of 84.90, and a classification accuracy of 55.4%.

While demographic data such as age, education, and income were collected, these were treated as control variables rather than independent predictors of library use. This approach reflects the study’s theoretical framework, which emphasizes symbolic and cultural dimensions of class identity (Florida, Bourdieu, Chatman, and Crenshaw) rather than demographic traits. Prior research indicates that older adults and higher-earning or college-educated Black individuals are often library users, but these were not the focus of this study. Thus, creative-class identity was tested as the primary predictor of library engagement, with demographic variables serving as controls to ensure robustness.

5.6. Model 2: Educational Attainment → Creative-Class Identity

This model corresponds to Hypothesis 2, grounded in Florida’s creative class framework and Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital. It predicted that higher levels of education would increase the likelihood of identifying as part of the creative class. Educational attainment, measured on a 1–6 ordinal scale, demonstrated a statistically significant relationship (B = 0.456, SE = 0.216, z = 2.107, p = 0.035, 95% CI [0.032, 0.880]). The odds ratio (OR = 1.58) indicated that each one-level increase in education was associated with a 58% increase in the odds of identifying with the creative class. The model demonstrated relatively strong fit and classification accuracy, with a pseudo-R2 of 0.086, an AIC of 52.03, a BIC of 56.08, and a classification accuracy rate of 78.6%.

5.7. Model 3: Household Income → Creative-Class Identity

This model corresponds to Hypothesis 3, which explored whether household income predicted creative-class identification. This test was included to distinguish the symbolic role of education from purely economic resources. Income was treated as an ordinal variable from one (<USD 50,000) to seven (>USD 500,000). While the coefficient for income was positive, it was not statistically significant (B = 0.193, SE = 0.220, z = 0.878, p = 0.381, 95% CI [−0.238, 0.624]). The odds ratio (OR = 1.21) indicated a 21% increase in the odds of identifying with the creative class per unit increase in income, though the confidence interval crossed zero. The model had a low pseudo-R2 (0.015), with an AIC of 55.76, a BIC of 59.81, and a classification accuracy of 82.1%, indicating strong predictive accuracy but weak explanatory power.

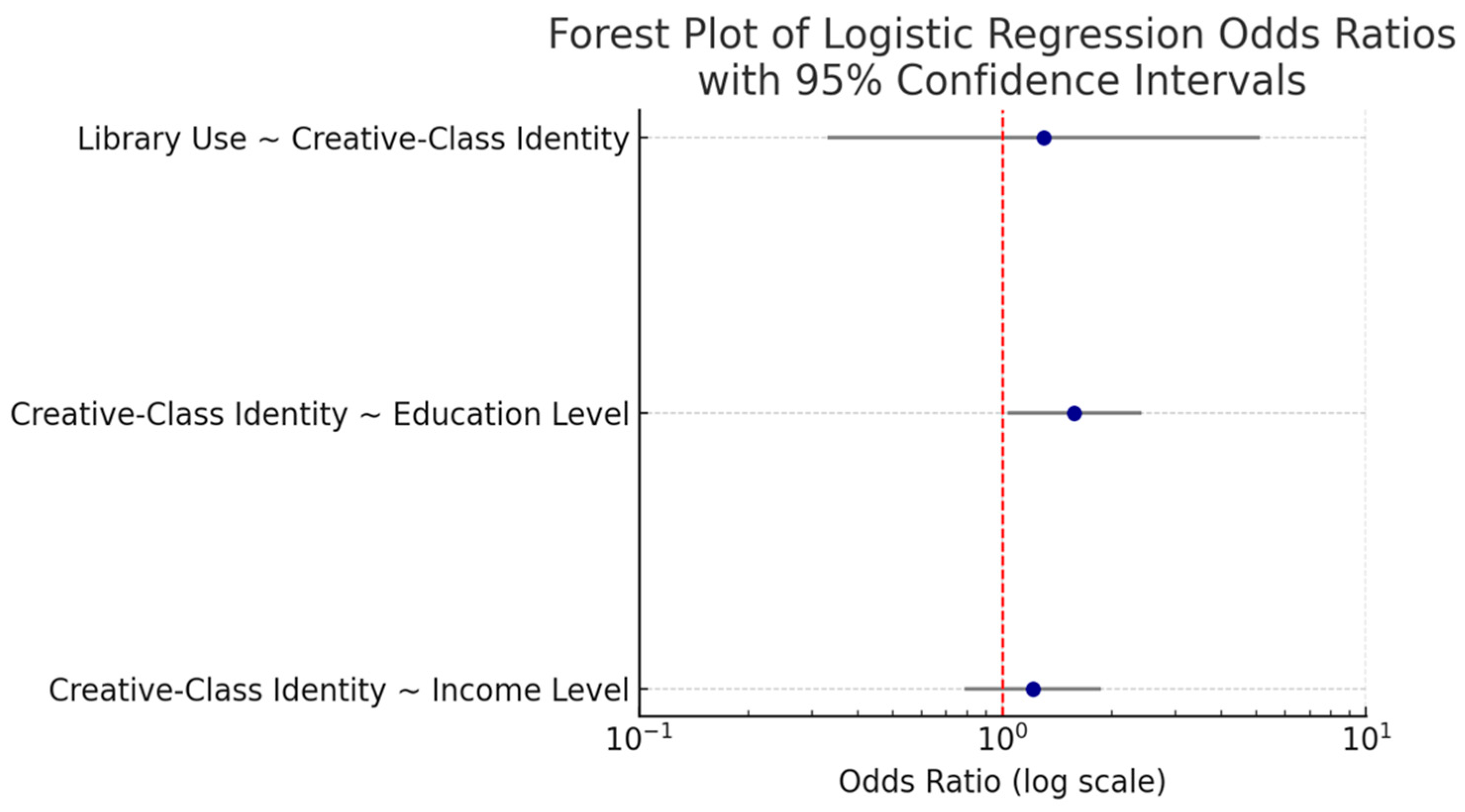

These results are summarized in

Figure 2, which presents odds ratios and confidence intervals for all three regression models. Additionally,

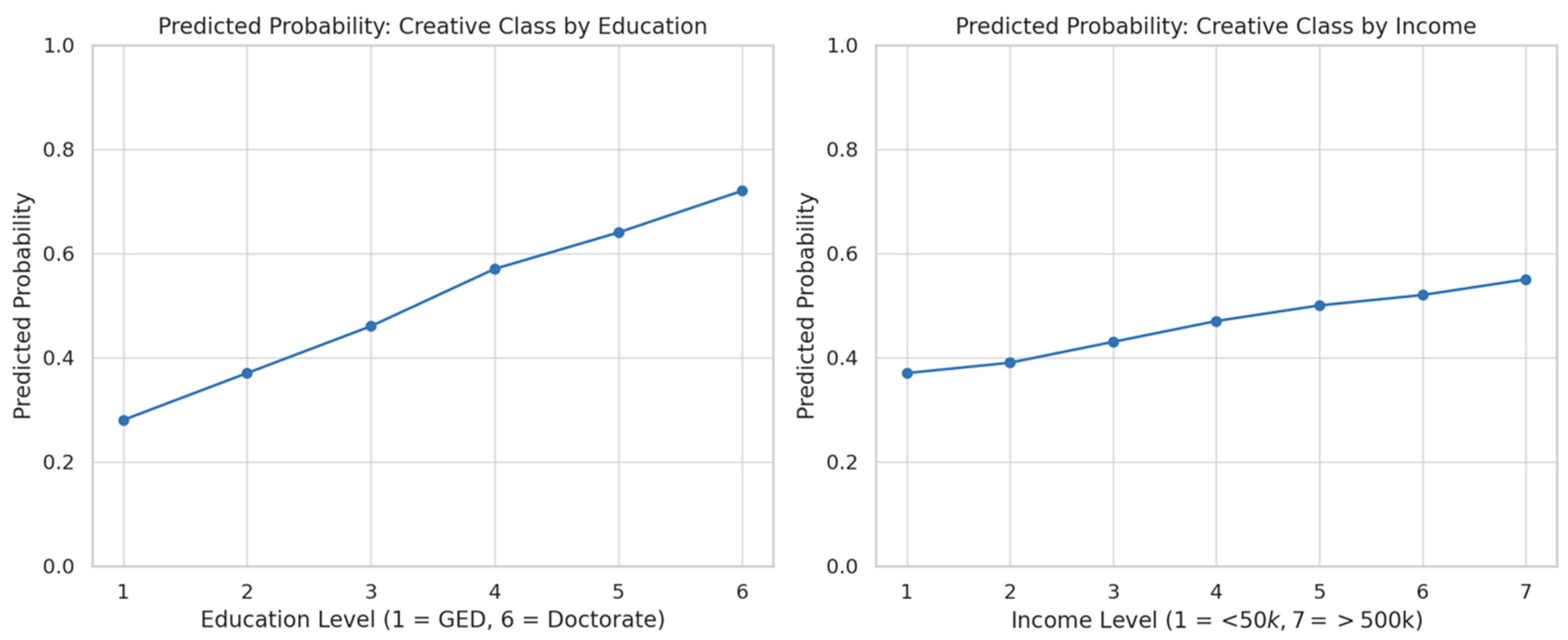

Figure 3 illustrates the predicted probability of creative-class identification by education and income level.

Figure 2 illustrates the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (log scale) from the three logistic regression models. Creative-class identity did not significantly predict library use (OR = 1.30, 95% CI [0.33, 5.11]). Education significantly predicted creative-class identity (OR = 1.58, 95% CI [1.03, 2.41]); income did not (OR = 1.21, 95% CI [0.79, 1.87]). The vertical red line represents the null effect (OR = 1).

Figure 3 predicted the probability of creative-class identity as a function of education (left panel) and income (right panel) among Black homeowners. The education effect is statistically significant (

p < 0.01), while the income effect is not (

p > 0.05), suggesting that education is a more robust predictor of creative-class self-identification.

5.8. Model Fit Comparison

Model fit was evaluated using AIC, BIC, and classification accuracy. The education-based model exhibited the best overall fit (AIC = 52.03, BIC = 56.08, accuracy = 78.6%), followed by the income model (AIC = 55.76, BIC = 59.81, accuracy = 82.1%). The creative-class-identity-to-library-use model performed the weakest (AIC = 80.85, BIC = 84.90, accuracy = 55.4%). In summary, educational attainment was the only statistically significant predictor of creative-class identity. Neither household income nor creative-class identity significantly predicted public library use.

6. Discussion

This study examines the relationship between cultural capital indicators, specifically higher education, homeownership, and salaried employment, and BCC identity, and their association with public library use among Black homeowners in Ward 8, Washington, D.C. The findings challenge the assumption that shared racial or geographic identity results in shared institutional behavior, reinforcing the theoretical complexities advanced by Chatman [

17], Florida [

18], Crenshaw [

19,

21], and Bourdieu [

22].

Among the study’s key findings, educational attainment emerged as a statistically significant predictor of creative-class identity, while household income did not. Although the original hypothesis anticipated that creative-class identity would be positively associated with public library use, the results revealed a more nuanced dynamic. Creative-class identity was not a significant predictor of library use, suggesting limits to the explanatory power of cultural identity alone in shaping institutional engagement.

Consistent with the study’s theoretical orientation, demographic characteristics such as income, education, and age were incorporated as controls rather than tested as stand-alone predictors of library engagement. This decision reflects the emphasis in Chatman’s Small World Theory, Florida’s Creative Class, and Crenshaw’s Intersectionality frameworks on cultural identity and structural positioning rather than demographic markers [

17,

18,

19,

21,

37]. Prior studies have shown that higher-income, college-educated, and older Black adults sometimes exhibit greater library participation [

53,

54], but such associations were not central to this study’s research questions. Instead, the focus remained on whether symbolic class identification, rather than socioeconomic status or age, shaped library usage in a historically marginalized urban community.

The relationship between education and creative-class identity reinforces Florida’s argument that education serves as a central axis of class identity in knowledge-based economies [

18,

22]. This finding also supports Bourdieu’s [

22] theory of cultural capital by highlighting how educational attainment confers symbolic power, thereby reinforcing class distinctions within racially homogeneous communities. In a place like Ward 8, marked by systemic disinvestment and historical racial exclusion, education becomes not only a pathway to economic mobility but also a key marker of identity and status among Black middle-class residents [

44,

45].

The historical legacy of library desegregation provides further insight into current patterns of engagement. As shown by the desegregation efforts of the 20th century, Black communities have long fought for equal access to public libraries, challenging both formal and informal exclusionary practices [

15,

38,

55,

56]. This legacy continues to influence perceptions of institutional trust, cultural belonging, and how welcoming libraries are seen, especially in communities like Ward 8 that have faced systemic marginalization.

The lack of a significant relationship between income and creative-class identity complicates the conventional understandings of class as primarily economic. This divergence underscores the importance of symbolic and cultural capital, particularly education, in shaping how individuals see themselves and relate to public institutions, even within middle- and upper-income brackets.

The adaptation of Chatman’s Small World Theory provides a valuable lens for interpreting these findings. While Chatman emphasized how information behavior emerges from tightly bounded social worlds, this study recontextualized her framework to focus on shared spatial and institutional exposure in Ward 8 rather than interpersonal ties. However, the findings reveal that shared proximity to public institutions, such as libraries, did not lead to uniform patterns of engagement. Creative-class identity did not significantly predict public library use, suggesting that spatial proximity and class identification alone are insufficient for shaping information behavior. In line with Chatman’s work, this underscores the role of institutional trust, perceived cultural alignment, and symbolic relevance in determining whether libraries are integrated into one’s “small world.”

Crenshaw’s [

21] framework of intersectionality further illuminates the findings by highlighting meaningful variation among participants who, while uniformly identifying as Black and residing in the same geographic community, expressed divergent class-based identities. Educational attainment, in particular, emerged as a stratifying factor that influenced self-perception, cultural orientation, and potential institutional trust. These results affirm the need for intersectional approaches in LIS and urban studies that consider the co-constitutive roles of race, class, and education in shaping institutional engagement.

This study also contributes to broader scholarly discourse on class-based identity and library engagement among the Black middle class. For instance, Hicks [

57] argues that libraries often reflect white, middle-class cultural norms under the guise of neutrality. Despite participants’ educational attainment and identification with creative-class identity, library use was not statistically associated with that identity, suggesting that cultural alignment, rather than socioeconomic status alone, is central to shaping institutional trust and engagement.

Similarly, Mehra and Braquet [

58] show how libraries can alienate marginalized users through embedded cultural assumptions in service design and spatial layout. While their work focused on LGBTQ+ communities, the parallels are compelling: even middle-class Black homeowners may encounter subtle forms of exclusion when institutional norms fail to reflect their lived experiences. Vinopal [

59] reinforces this critique by arguing that libraries often fail to interrogate their structural inequalities. The finding that neither income nor creative-class identity predicted library use suggests that barriers to engagement persist, even for those with high levels of cultural capital. This supports Vinopal’s call for equity-centered library redesigns that prioritize both cultural responsiveness and institutional self-reflection.

Collectively, these findings contribute to a growing body of literature that critiques assumptions of uniform access, trust, and belonging within public institutions. For libraries to serve as equitable civic spaces, they must go beyond resource provision and address the cultural signals embedded in their spaces, programming, and engagement strategies. The findings affirm the need for public libraries to adopt culturally inclusive programming that acknowledges class-based variation within racially homogeneous communities, particularly the Black middle class.

6.1. Limitations

This study provides valuable insights into the relationship between cultural capital and library use among Black homeowners in Washington, D.C., but several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the small sample size (n = 56) restricts how broadly the results can be applied. Finding verified owner–occupants was challenging due to gaps in public datasets and difficulties in building trust. Although outreach through listservs and word-of-mouth proved effective, it may have introduced bias by favoring socially connected individuals. The lack of a neutral “third place” in Ward 8, a welcoming community space for Black middle-class residents, further hindered trust-building and participation. Second, the study’s focus on Ward 8 could limit its generalizability. Although often considered a single unit, the ward comprises distinct neighborhoods with different levels of investment, infrastructure, and cohesion, which may influence civic behavior in various ways. Finally, relying on self-reported, cross-sectional survey data limits causal inferences and may be affected by recall bias or social desirability bias, especially on sensitive topics related to class, income, and institutional involvement. While the survey was theoretically grounded and reviewed for validity, closed-ended questions might not fully capture the nuances of class identity or symbolic perceptions. Recognizing the challenge of openly discussing these themes, the study prioritized confidentiality and voluntary participation to encourage honest and reflective responses.

6.2. Implications

The findings of this study offer valuable insights for public libraries, urban planners, and local policymakers working to create equitable and culturally responsive civic institutions. For libraries, outreach and programming must go beyond economic status and consider cultural identity and class-based worldviews. Having a creative-class affiliation among Black middle-class residents does not automatically lead to trust or use of institutions. Instead, libraries must engage with the symbolic and cultural aspects of belonging. Urban planners should incorporate the perspectives of Black middle-class homeowners into long-term development plans that prioritize equity and sustainability. Recognizing differences within groups in civic behavior helps prevent oversimplifying the cultural diversity of historically marginalized communities. Likewise, policymakers need to understand that Black residents in Ward 8 are not a homogeneous, single group. Factors such as education, income, and cultural identity influence how individuals interact with institutions and participate in civic life. Overall, this study emphasizes that attending public libraries is not simply a result of middle-class or creative-class identity; it is shaped by cultural values, family legacies, and class-based experiences. Public institutions must adopt culturally responsive approaches that go beyond demographic checkboxes to better meet the diverse and complex needs of the communities they serve.

7. Conclusions

This study contributes to the growing body of research on race, class, and public institutional engagement by examining how BCC identity, shaped by cultural capital, relates to library use among Black homeowners in Washington, D.C.’s Ward 8. The findings yield three key conclusions:

Education, rather than income, is the most consistent predictor of creative-class self-identification, underscoring the primacy of cultural capital in shaping class identity within the Black middle class;

While creative-class identity is culturally and symbolically meaningful, it does not predict public library use in this population. This suggests that perceptions of institutional relevance and trust are influenced by factors beyond socioeconomic indicators alone;

Intersectionality remains critical to understanding engagement patterns within racially homogeneous communities. Black homeowners in Ward 8 differ meaningfully in their orientation toward public institutions based on intragroup class identity and cultural worldview;

The adapted theoretical framework developed in this study advances both LIS and urban studies by challenging the assumption that middle-class status ensures uniform patterns of institutional engagement. It adapts Chatman’s Small World Theory to focus on shared spatial and institutional contexts rather than tightly bounded social networks, reinterprets Florida’s creative class framework to center the lived experiences of the Black urban middle class, and applies Crenshaw’s intersectionality to illuminate intragroup differences, demonstrating that race alone is insufficient to explain institutional behavior.

Together, these adaptations underscore the importance for public institutions, particularly libraries, to reassess how cultural signaling, spatial context, and internal class diversity impact civic participation and information behavior. Future research should incorporate qualitative or mixed-method approaches to explore how cultural identity, symbolic alignment, and lived experiences shape trust, belonging, and engagement with public institutions among Black middle-class populations. Such approaches will enable scholars and practitioners to identify and address the structural and symbolic barriers that persist in historically marginalized communities more effectively.