From Voice to Action: Upholding Children’s Right to Participation in Shaping Policies and Laws for Digital Safety and Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analysis of the Normative Framework

2.2. Methodological Considerations: Participation and Resilience, the State of Well-Being and Digital Literacy and Legal Consciousness

2.3. Practical Implementation of Participation Rights

3. Results

3.1. The Normative Framework of Children’s Right to Be Heard

3.2. The Relationship Between Participation and Resilience

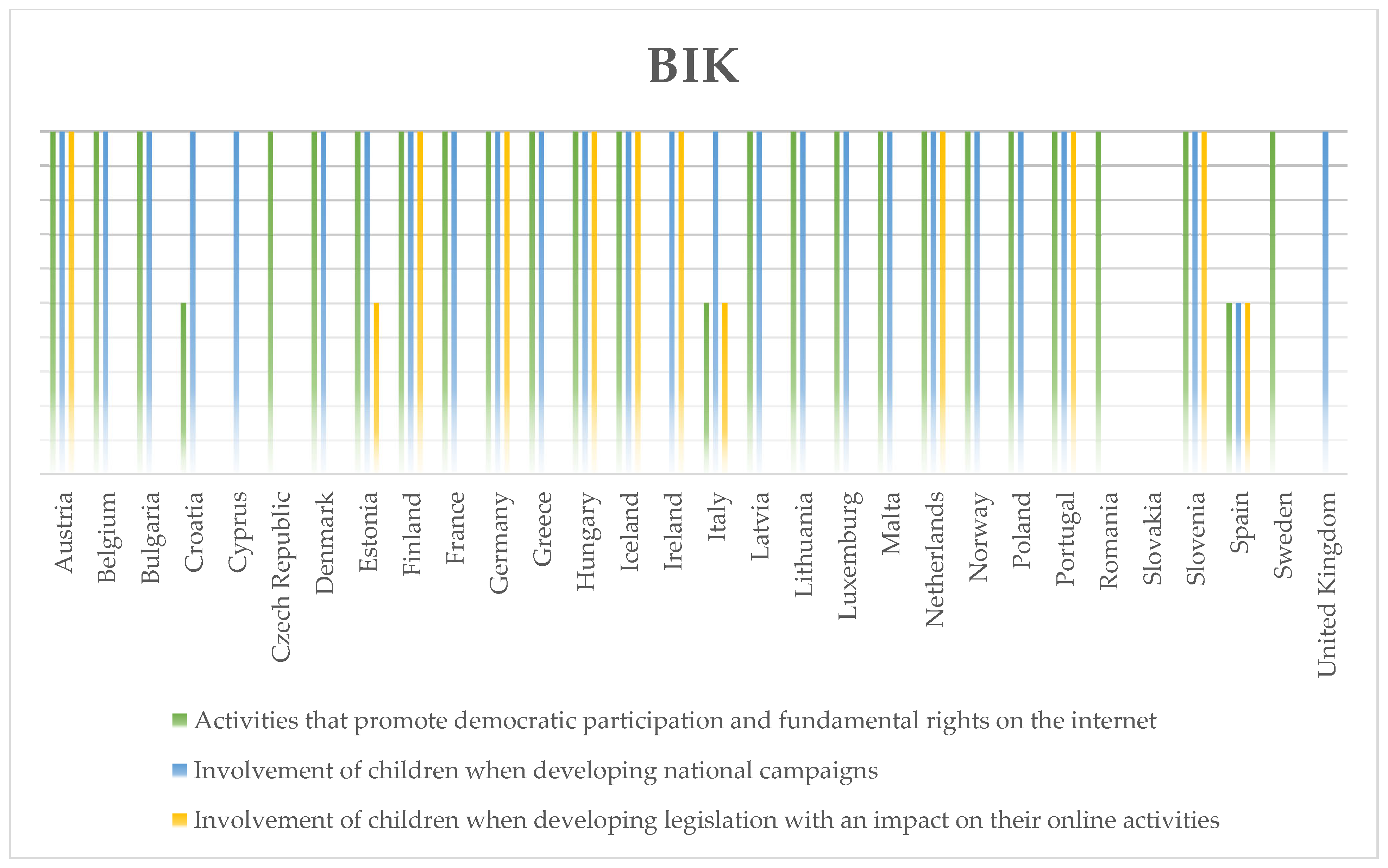

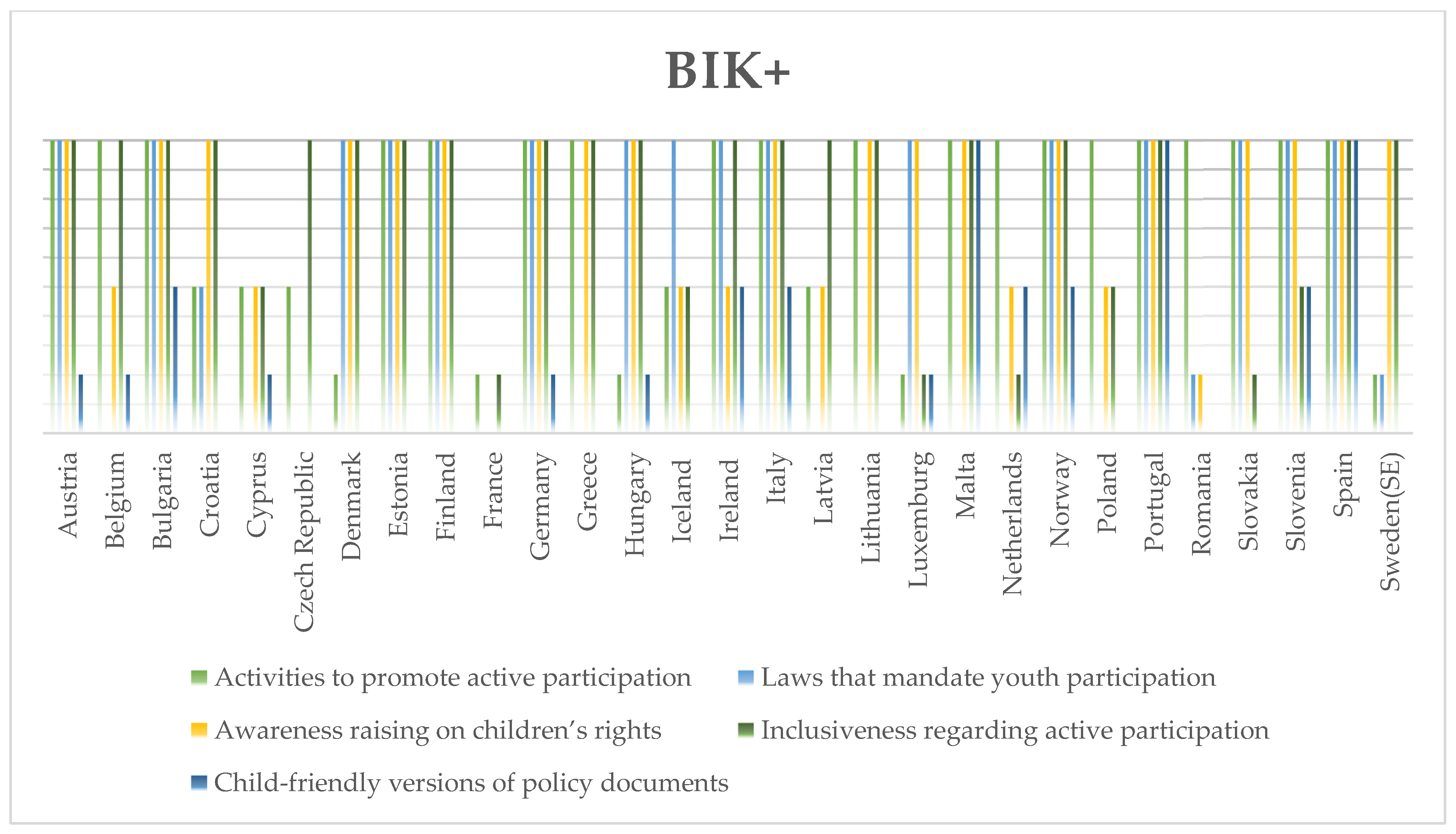

3.3. Findings from the BIK and BIK+ Policy Monitoring

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| BIK | European Strategy for a Better Internet for Children |

| BIK+ | A Digital Decade for children and youth: the new European strategy for a better internet for kids |

References

- Parti, K.; Szabó, J. The Legal Challenges of Realistic and AI-Driven Child Sexual Abuse Material: Regulatory and Enforcement Perspectives in Europe. Laws 2024, 13, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S.; Stoilova, M. The 4Cs: Classifying Online Risk to Children. (CO:RE Short Report Series on Key Topics); Leibniz-Institut für Medienforschung | Hans-Bredow-Institut (HBI); CO:RE—Children Online: Research and Evidence: Hamburg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taft, J.K. Social Movements, INGOs, and the Meaning of Children’s Political Participation: Lessons from the 1997 Oslo Working Children’s Forum. Globalizations 2025, 22, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, R.G.D.S.; Mancini, M.C.; Samora, G.A.R.; Magalhães, R.C.; Drummond, A.D.F. Children and Youth’s Participation at Home, School and Community: Differences between Socioeconomic Status. Rev. Caribeña Cienc. Soc. 2023, 12, 1891–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riádigos, J.; Gradaílle, R. The Forum for the Participation of Children and Teenagers in Teo: A Socio-Educational Context That Enables Children’s Right to Participation. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2023, 153, 107112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munongi, L. “What If We Give Them Too Much Voice?”: Teachers’ Perceptions of the Child’s Right to Participation. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2023, 43, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hareket, E.; Kartal, A. An Overview of Research on Children’s Rights in Primary School: A Meta Synthesis. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 131, 106286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, K. The Subjective Importance of Children’s Participation Rights: A Discrimination Perspective. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2019, 89, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciver, D.; Rutherford, M.; Arakelyan, S.; Kramer, J.M.; Richmond, J.; Todorova, L.; Romero-Ayuso, D.; Nakamura-Thomas, H.; Ten Velden, M.; Finlayson, I.; et al. Participation of Children with Disabilities in School: A Realist Systematic Review of Psychosocial and Environmental Factors. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragnedda, M.; Ruiu, M.L.; Calderón-Gómez, D. Examining the Interplay of Sociodemographic and Sociotechnical Factors on Users’ Perceived Digital Skills. Media Commun. 2024, 12, 8167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C.S.; Vacas, C.G.; Muñoz, E.M.; Levterova, D.; Lazarov, A. Digital Divide and Accessibility in Online Education. Edelweiss Appl. Sci. Technol. 2025, 9, 2548–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sianko, N.; Kapllanaj, M.; Small, M.A. Measuring Children’s Participation: A Person-Centered Analysis of Children’s Views. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 737–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunestveit, M.; Njøs, B.; Seim, S. Collective Participation of Children and Young People in Child Welfare Services—Opportunities and Challenges. Eur. J. Soc. Work. 2022, 26, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, L. ‘Voice’ is not enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 33, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.; Lundy, L. Reconciling children’s policy and children’s rights: Barriers to effective government delivery. Child Care Health Dev. 2015, 29, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaesling, K. Children’s digital rights: Realizing the potential of the CRC. In Global Reflections on Children’s Rights and the Law: 30 Years after the Convention on the Rights of the Child; Marrus, E., Laufer-Ukeles, P., Ukeles, L., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2022; pp. 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrington, C.; Larkins, C. Children at the centre of safety: Challenging the false juxtaposition of protection and participation. J. Child. Serv. 2019, 14, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissenberg, J.; d’Haenens, L.; Livingstone, S. Digital literacy and online resilience as facilitators of young people’s wellbeing: A systematic review. Eur. Psychol. 2022, 27, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, K. Engagement and Immersion in Digital Play: Supporting Young Children’s Digital Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Li, H. A Scoping Review of Digital Well-Being in Early Childhood: Definitions, Measurements, Contributors, and Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L.; Ribeiro, P. Resilience of urban transportation systems. Concept, characteristics, and methods. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 85, 102727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmann, J.; Guenther, E. Organizational Resilience: A Valuable Construct for Management Research? Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 7–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Y. Defining, Conceptualizing, and Measuring Organizational Resilience: A Multiple Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, Á. The Status and Role of Law and Regulation in the 21st-Century Hybrid Security Environment. Acta Univ. Sapientiae Leg. Stud. 2022, 11, 171–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañizares, J.C.; Copeland, S.M.; Doorn, N. Making Sense of Resilience. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, K.R.; Jablow, M.M. Building Resilience in Children and Teens. Giving Kids Roots and Wings, 4th ed.; American Academy of Pediatrics: Itasca, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Digital Literacies: Concepts, Policies and Practices; Lankshear, C., Knobel, M., Eds.; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Weninger, C. Skill versus Social Practice? Some Challenges in Teaching Digital Literacy in the University Classroom. TESOL Q. 2022, 56, 1016–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrin, C.; Audrin, B. Key Factors in Digital Literacy in Learning and Education: A Systematic Literature Review Using Text Mining. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 7395–7419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.; Sharma, B.; Chaudhary, K. Digital Literacy: A Review of Literature. Int. J. Technoethics 2020, 11, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozyreva, A.; Wineburg, S.; Lewandowsky, S.; Hertwig, R. Critical Ignoring as a Core Competence for Digital Citizens. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 32, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurava, G.; Kotilainen, S. Digital Literacy as a Pathway to Professional Development in the Algorithm-Driven World. Nord. J. Digit. Lit. 2023, 18, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, M.C.; Bhawra, J.; Katapally, T.R. Navigating the Digital World: Development of an Evidence-Based Digital Literacy Program and Assessment Tool for Youth. Smart Learn. Environ. 2024, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, E.; Goin, M.E.; Ho, A.; Parks, A.; Rowe, S. Critical Digital Literacy as Method for Teaching Tactics of Response to Online Surveillance and Privacy Erosion. Comput. Compos. 2021, 61, 102654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmoelz, A.; Geppert, C.; Schwarz, S.; Svecnik, E.; Koch, J.; Bieg, T.; Freund, L. Assessing the Second-Level Digital Divide in Austria: A Representative Study on Demographic Differences in Digital Competences. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2023, 44, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, M. Does the Digital Divide Matter? Factors and Conditions That Promote ICT Literacy. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 58, 101536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajam, V.; Reddy, A.B.; Banerjee, S. Explaining caste-based digital divide in India. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 65, 101719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, R.; Squillace, J.; Németh, R.; Cappella, J. The Impact of Digital Inequality on IT Identity in the Light of Inequalities in Internet Access. ELTE Law J. 2024, 12, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjin-Tettey, T.D. Combating Fake News, Disinformation, and Misinformation: Experimental Evidence for Media Literacy Education. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2022, 9, 2037229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, E.-C.; Balaban, D.C. The Effectiveness of an Educational Intervention on Countering Disinformation Moderated by Intellectual Humility. Media Commun. 2025, 13, 9109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, M.; Rúas-Araújo, J.; Horowitz, M. Beyond Online Disinformation: Assessing National Information Resilience in Four European Countries. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailidis, P.; Thevenin, B. Media Literacy as a Core Competency for Engaged Citizenship in a Networked Democracy. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 1611–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, N.J. Gender-Based Violence, Twin Pandemic to COVID-19. Crit. Sociol. 2021, 47, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshmehzangi, A.; Zou, T.; Su, Z. The Digital Divide Impacts on Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 101, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorsi, G.; Gallinoro, V.; Guida, A.; Morittu, C.; Ferro Allodola, V.; Lastrucci, V.; Zanobini, P.; Okan, O.; Dadaczynski, K.; Lorini, C. Digital Health Literacy and Information-Seeking in the Era of COVID-19: Gender Differences Emerged from a Florentine University Experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Key Messages and Actions for COVID-19 Prevention and Control in Schools; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, G.; Lo Scalzo, L.; Giuffrè, M.; Ferrara, P.; Corsello, G. Smartphone Use and Addiction during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: Cohort Study on 184 Italian Children and Adolescents. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, A.; Bethell, C.D.; Yamaoka, Y.; Morisaki, N. How Listening to Children Impacts Their Quality of Life: A Cross-Sectional Study of School-Age Children during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Japan. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2024, 8, e002962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archard, D.; Uniacke, S. The Child’s Right to a Voice. Res. Publica 2020, 27, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1989. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/crc.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Committee on the Rights of the Child. General Comment No. 12 (2009): The Right of the Child to Be Heard. 2009. Available online: https://docstore.ohchr.org/SelfServices/FilesHandler.ashx?enc=YDah9tP9EQ4yJGUbd1XDmaOoMVuVv2KW4ANWL9tpK079%2BonDsRJ0Ml%2FiNhKKcf4S8cVgG4Sb3HsKSs9SKqy5zA%3D%3D (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Committee on the Rights of the Child. General Comment No. 25 (2021) on Children’s Rights in Relation to the Digital Environment. 2021. Available online: https://docstore.ohchr.org/SelfServices/FilesHandler.ashx?enc=H7gSiTrGnN8Kz89nitiHmFJww2AnfdyTopg7NaqMK3cP9VzxbcxmYirTrM%2BToYhGEltLAW33x5DgMRr3Lim7Tg%3D%3D (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Council of Europe. Recommendation on the Participation of Children and Young People under the Age of 18 (CM/Rec(2012)2). 2012. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/youth/-/recommendation-on-the-participation-of-children-and-young-people-under-the-age-of-18 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Council of Europe. Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers on the Guidelines to Respect, Protect and Fulfil the Rights of the Child in the Digital Environment (CM/Rec(2018)7). 2018. Available online: https://search.coe.int/cm/Pages/result_details.aspx?ObjectId=09000016808b79f7 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Council of Europe. It’s Our World: Children’s Views on How to Protect Their Rights in the Digital Environment; A Report on Children’s Consultations; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2017; Available online: https://edoc.coe.int/en/children-and-the-internet/8013-it-s-our-world-children-s-views-on-how-to-protect-their-rights-in-the-digital-environment.html (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Council of Europe. Strategy for the Rights of the Child (2022–2027): Children’s Rights in Action—From Continuous Implementation to Joint Innovation; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2022; Available online: https://rm.coe.int/council-of-europe-strategy-for-the-rights-of-the-child-2022-2027-child/1680a5ef27 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. Proclaimed 7 December 2000; entered into legal force 1 December 2009 (Treaty of Lisbon). Official Journal of the European Union C 326, 26 October 2012, pp. 391–407. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/treaty/char_2012/oj/eng (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Verdoodt, V. Children’s Rights in the Digital Environment: MOVING from Theory to Practice: Best-Practice Guideline; European Commission and European Schoolnet: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Miraglia, F.; Rath-Bosca, A.-C. Howling at the blind lady: Communication barriers between minors, parents, and the law. AGORA Int. J. Jurid. Sci. 2024, 18, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: European Strategy for a Better Internet for Children (COM(2012) 0196 Final). 2012. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52012DC0196 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- O’Neill, B.; Dreyer, S.; Dinh, T. The Third Better Internet for Kids Policy Map: Implementing the European Strategy for a Better Internet for Children in European Member States; European Schoolnet: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://better-internet-for-kids.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2024-11/Third%20Better%20Internet%20for%20Kids%20Policy%20Map%20report%20-%20November%202020.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A Digital Decade for Children and Youth: The New European Strategy for a Better Internet for Kids (BIK+) (COM(2022) 212 Final). 11 May 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52022DC0212 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- All Country Information Sheets from the Third Better Internet for Kids (BIK) Policy Map Report (2020). Available online: https://better-internet-for-kids.europa.eu/en/knowledge-hub/policy-monitor/archive (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- European Commission. Better Internet for Kids (BIK) Policy Monitor—Country Profiles. Available online: https://www.betterinternetforkids.eu/en/knowledge-hub/policy-monitor/country (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Sun, H.; Yuan, C.; Qian, Q.; He, S.; Luo, Q. Digital Resilience Among Individuals in School Education Settings: A Concept Analysis Based on a Scoping Review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 858515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drossel, K.; Eickelmann, B.; Vennemann, M. Schools Overcoming the Digital Divide: In Depth Analyses Towards Organizational Resilience in the Computer and Information Literacy Domain. Large-Scale Assess. Educ. 2020, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lim, J.-A.; Nam, H.-K. Effect of a Digital Literacy Program on Older Adults’ Digital Social Behavior: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kar, A.K.; Gupta, M.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Janssen, M. Digital Citizen Empowerment: A Systematic Literature Review of Theories and Development Models. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2022, 28, 702–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S.; Mascheroni, G.; Stoilova, M. The Outcomes of Gaining Digital Skills for Young People’s Lives and Wellbeing: A Systematic Evidence Review. New Media Soc. 2021, 25, 1176–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, R.; Farkas, Á.; Bučko, B.; Jordan, Z. Public Trust in National Security Institutions as a Key to Sustainable Security. Connect. Q. J. 2024, 23, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.L.; Connery, C.; Blackson, G.N.; Divine, T.F.; Walker, T.D.; Williams, B.; Finke, J.A.; Bartel, K. Developing Resilience in Youth with Incarcerated Parents: A Bibliotherapeutic Blueprint with Tween and Young Adult Literature Chapter Books. J. Correct. Educ. 2020, 71, 44–69. [Google Scholar]

- Young, K.; Billings, K.R. Legal Consciousness and Cultural Capital. Law Soc. Rev. 2020, 54, 120–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrett, N.; Liu, Y.; Vandell, D.L.; Simpkins, S. The Role of Organized Activities in Supporting Youth Moral and Civic Character Development: A Review of the Literature. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2020, 6, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantan, M.; Squillace, J. Privacy Inequality and IT Identities: The Impact of Different Privacy Laws Adoptions. In Proceedings of the AMCIS 2022, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 10–14 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kelemen, R. Cyberfare State Concept: The Impact of the Transformation of Individuals and their Relationships on the Functioning and Security of the State. J. Inf. Ethics 2024, 33, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Keck, M.; Sakdapolrak, P. What Is Social Resilience? Lessons Learned and Ways Forward. Erdkunde 2013, 67, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhomirov, Y.A. Legal Consciousness amid Social Dynamics. Her. Russ. Acad. Sci. 2020, 90, S233–S240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmen, E.; Fazey, I.; Ross, H.; Bedinger, M.; Smith, F.M.; Prager, K.; McClymont, K.; Morrison, D. Building Community Resilience in a Context of Climate Change: The Role of Social Capital. AMBIO 2022, 51, 1371–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. BIK Youth Panel (Better Internet for Kids Youth Panel). Available online: https://better-internet-for-kids.europa.eu/en/bik-youth/panel (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Hope, K.R. Peace, justice and inclusive institutions: Overcoming challenges to the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 16. Glob. Change Peace Secur. 2020, 32, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarden, A.; Roache, A. What is wellbeing? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Dias, J.C. Sustainability and the digital transition: A literature review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, H.; Coll-Seck, A.M.; Banerjee, A.; Peterson, S.; Dalglish, S.L.; Ameratunga, S.; Balabanova, D.; Bhan, M.K.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Borrazzo, J.; et al. A future for the world’s children? A WHO-UNICEF-Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 395, 605–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievens, E. Growing Up with Digital Technologies: How the Precautionary Principle Might Contribute to Addressing Potential Serious Harm to Children’s Rights. Nord. J. Hum. Rights 2021, 39, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 7C Element | BIK (2012) | BIK+ (2022) |

|---|---|---|

| Competence | To promote digital and media literacy through education and teacher training. | To foster digital literacy, critical thinking and media literacy among children. |

| Confidence | To encourage children to participate online safely and responsibly. | To empower children to engage online safely and confidently. |

| Connection | To support Safer Internet Centres and youth networks. | To support the creation of safe online communities for children. |

| Character | To foster respect and responsible behaviour online. | To promote respect for others and responsible behaviour online. |

| Contribution | To engage children in creating positive online content and in policy-making processes. | To engage children in shaping digital policies and initiatives. |

| Coping | To provide tools and training to address cyberbullying and harmful content. | To equip children to deal with online harassment and harmful content. |

| Control | To ensure availability of parental controls, privacy settings and age-appropriate access. | To promote awareness and control of privacy settings and personal data management. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kovács-Szépvölgyi, E.; Tóth, D.A.; Kelemen, R. From Voice to Action: Upholding Children’s Right to Participation in Shaping Policies and Laws for Digital Safety and Well-Being. Societies 2025, 15, 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15090243

Kovács-Szépvölgyi E, Tóth DA, Kelemen R. From Voice to Action: Upholding Children’s Right to Participation in Shaping Policies and Laws for Digital Safety and Well-Being. Societies. 2025; 15(9):243. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15090243

Chicago/Turabian StyleKovács-Szépvölgyi, Enikő, Dorina Anna Tóth, and Roland Kelemen. 2025. "From Voice to Action: Upholding Children’s Right to Participation in Shaping Policies and Laws for Digital Safety and Well-Being" Societies 15, no. 9: 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15090243

APA StyleKovács-Szépvölgyi, E., Tóth, D. A., & Kelemen, R. (2025). From Voice to Action: Upholding Children’s Right to Participation in Shaping Policies and Laws for Digital Safety and Well-Being. Societies, 15(9), 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15090243