Abstract

This study explored how dance style preferences among recreational dancers in Greece reflect intersections of cultural identity, demographic background, and lifelong engagement. A total of 912 participants were analyzed using chi-square and Kruskal–Wallis tests, Spearman correlation, and k-means cluster analysis. Significant associations were found between gender and stylistic preferences, with women favoring ballet and contemporary styles, while men preferred traditional and partner-based forms such as tango. Kruskal–Wallis tests indicated that age influenced stylistic preferences, though it did not significantly differentiate participant clusters. A weak but statistically significant positive correlation was observed between age and years of dancing experience. k-means clustering revealed four distinct participant profiles based on gender, residence, experience, and stylistic engagement, highlighting culturally shaped participation patterns. Urban dancers exhibited broader stylistic diversity, whereas rural dancers showed stronger preferences for traditional genres, emphasizing the influence of cultural heritage. These findings demonstrate how identity, environment, and experiential factors could shape recreational dance paths across the lifespan. The study highlights the need for culturally responsive, inclusive, and participant-centered dance education and culturally informed tourism programming that accommodates diverse pathways of engagement. Future research is recommended to investigate motivational factors and cross-cultural patterns to further deepen understanding and inform recreational dance communities.

1. Introduction

Dance, in its recreational form, represents a distinct sector of participation that differs fundamentally from professional or vocational training. Recreational dance is generally defined as non-competitive, non-elite engagement in dance for leisure, education, or community purposes, often of moderate intensity and frequency, and not oriented toward career development or staged performance [1,2]. Such programs typically occur in schools, community centers, or local studios and are accessible to participants of all ages and abilities. This distinction is essential for situating recreational dancers as a population whose motivations and outcomes are best understood within leisure studies and cultural capital frameworks [3].

Studies reported that recreational dance produces health outcomes comparable to, and in some cases more effective than, structured forms of exercise. Improvements in cardiovascular fitness, body composition, musculoskeletal strength, and day-to-day functionality have all been reported across the lifespan [4]. Beyond measurable physical benefits, dance contributes to psychosocial well-being, enhancing body image, reducing anxiety, and strengthening social connectedness [1,3].

Socially, recreational dance fosters cooperation, inclusion, and community belonging, as participants often learn, rehearse, and perform in group settings [2]. Unlike many other leisure activities, recreational dance uniquely integrates artistic creativity with physical exertion, requiring minimal equipment while offering both individual fulfillment and collective engagement. Research has highlighted its esthetic, artistic, and creative dimensions and emphasized how participation fosters embodiment, identity formation, belonging, self-worth, affective expression, and creativity [5]. These qualities highlight that recreational dance is not only a vehicle for health promotion but also a cultural and artistic practice that enriches lived experience and sustains engagement through its intrinsic appeal. In contexts such as Greece, this dual role is especially marked, as recreational dance functions both as a mode of cultural preservation through folk traditions and as a contemporary leisure pursuit [6,7]. According to those, understanding the factors that shape participation becomes critical.

Dance preferences and motivations are shaped by a complex interplay of demographic factors, including age, gender, residence, and years of dancing experience [8,9]. These elements influence not only the styles of dance individuals choose but also the reasons behind their participation, reflecting broader cultural, social, and personal dynamics [10,11].

1.1. Gender and Dance Preferences

Researchers highlighted the complex relationship between gender and dance preferences, emphasizing the need for awareness and inclusivity in dance education and practice to challenge and move beyond traditional gender stereotypes. Oliver and Risner [12] examined how gender impacted various aspects of the dance world, including preferences, participation, and pedagogy. The study provided information about how gender influences the daily lives of dancers, choreographers, directors, educators, and students. Additionally, another study discussed how dance and gender intersect, revealing that gender not only regulates a dancer’s life choices but also influences the dance they produce, which in turn broadcasts gender representations [13]. Gender significantly influences dance preferences, with societal norms and cultural expectations often shaping the types of dance styles individuals are drawn to [13].

Coronel et al. [14] found that males choose mainly athletic and rhythm-centric styles such as hip-hop, whereas females are more evenly distributed across styles like contemporary and ballet, which often emphasize esthetic and expressive qualities. These distinctions align with societal norms and gender roles, where dance forms often carry traditional gendered connotations. Similarly, studies in England revealed that men prefer to breakdance and hip-hop for their competitive and physical nature, while women prefer ballet and jazz due to their alignment with societal ideals of grace and beauty [15].

1.2. Age, Dance Preferences, and Motivation

Research indicated that age significantly influences dance preferences, with individuals tending to favor dance styles that align with their developmental stage and life experiences. Barreiro and Furnham [10] examined recreational dancers across seven dance styles, such as ballet, contemporary, jazz/tap, hip-hop, belly dance, ballroom, and Latin, and found that motivations for choosing specific dance styles varied with age. Mood enhancement was a significant motivator across most styles, but its influence differed among age groups, suggesting that age-related factors play a role in dance style selection.

Additionally, Lovatt’s [8] research on dance confidence across different age groups revealed that dance confidence levels fluctuate at significant points in the developmental cycle. The findings suggested that age-related changes in self-perception and confidence may influence dance participation and preferences. Furthermore, a systematic review by Hwang and Braun [16] examined the effectiveness of dance interventions in improving older adults’ health. The review found that various dance styles, including ballroom, contemporary, cultural, and jazz, were effective in enhancing physical health outcomes among older adults. These findings suggested that as individuals age, their engagement with certain dance styles may be influenced by health considerations and the physical benefits associated with those styles. These studies collectively highlighted the complex relationship between age and dance preferences, indicating that age-related factors, including psychological, social, and health considerations, play a significant role in shaping individuals’ choices of dance styles.

Some other studies emphasized that age significantly impacts dance preferences and motivations. Younger dancers are drawn to high-energy, dynamic styles like hip-hop and rock and roll, often seeking novelty and challenge [14,17]. In contrast, older participants prefer styles such as traditional dance, ballroom, or Latin dance, which emphasize cultural connection and expressiveness [7,10]. Musil et al. [18] examined matters of age and aging in relation to dance, traversing the human lifespan from early childhood to older adulthood. They mentioned that age impacts dance by influencing physical abilities, artistic expression, and learning styles. Younger dancers excel in flexibility and energy, while older ones emphasize artistry and expression. Maraz et al. [9] emphasized the importance of inclusive dance education that accommodates individuals across the lifespan. Another study investigated the motivations behind teenagers’ participation in traditional dance activities [9]. Findings suggested that factors such as escape, relaxation, socialization, and learning new dances are significant motivators, indicating that age-specific preferences should be considered in dance education programs.

1.3. Residence and Cultural Identity

Residence plays a critical role in shaping exposure to and participation in dance. Urban areas, characterized by cultural diversity and access to professional training, foster engagement in contemporary and diverse dance styles [15]. Conversely, rural settings often emphasize traditional or folk dances that align with localized cultural heritage, as seen in Greece, where traditional dances serve as a medium for cultural preservation and social bonding [6,7]. Among foreign participants, traditional Greek dance also serves as a conduit for cultural immersion, blending recreation with tourism [7]. A recent study highlighted the specific motivations of members of traditional dance groups participating in tourist events, emphasizing the importance of cultural identification, collectivity, and experiential engagement as key elements of cultural tourism through dance [11]. The findings suggested that traditional dancing serves as a motive in cultural tourism, with significant attendance motives being Greek culture, social relations, and improvement of dancing skills.

Additionally, Dr. S. Ramesh [19] highlighted that dance exceeds entertainment to become a mirror reflecting societal norms and cultural expressions, indicating that cultural context plays a crucial role in shaping dance practices. Studies showed that residence and cultural context significantly influence dance education, affecting both the content taught and the methodologies employed. They highlighted the need for culturally responsive teaching practices that consider the unique cultural backgrounds and experiences of learners in different settings [20,21,22]. Furthermore, traditional dance events have been shown to foster cultural tourism, offering participants immersive experiences that connect them with local identity and heritage. In this context, Sgoura et al. [11] highlighted the motivational and experiential dimensions that drive dancers’ involvement in such events, particularly within rural communities.

1.4. Years of Experience and Style Versatility

Dancing experience correlates with evolving preferences and motivations. Beginner dancers often prioritize enjoyment and social interaction, preferring styles like salsa and traditional Greek dances that emphasize relaxation and friendship [4,6]. Experienced dancers, however, seek technical challenges and opportunities for mastery, favoring styles such as ballet and contemporary dance [10].

Zahiu et al. [23] further observed that long-lasting training enhances cognitive and motor adaptations, allowing experienced dancers to perceive choreography more holistically and engage deeply with complex movement sequences. The study emphasized the development of coordination, rhythmicity, and spatial-temporal orientation through targeted training programs, which directly connects years of experience with versatility in dance education and performance. This supported the broader claim that dance education aims to enhance technical skills, artistic expression, and versatility.

While specific studies directly linking years of dance experience to style versatility are limited, existing literature and expert opinions suggest a positive correlation between the two. Engaging in various dance styles over time enhances a dancer’s adaptability, broadens their movement vocabulary, and fosters versatility.

Conclusively, the interplay of age, gender, residence, and years of dancing experience shapes dance preferences and motivations. However, significant gaps exist in the provision of recreational dance opportunities, particularly in the Greek context. Urban–rural disparities and the limited integration of traditional Greek dances into popular recreational programs underline the need for targeted interventions. Addressing these gaps could enhance accessibility and preserve cultural heritage, ensuring that dance remains a vital part of both recreational and cultural life. These insights have critical implications for dance education and tourism programming.

Examining demographic factors is crucial, as it provides an insight into the diverse needs and preferences of participants. By aligning strategies with these demographics, dance programs could promote inclusivity, foster lifelong engagement, and contribute to the enrichment of personal and cultural expression. This approach is especially significant in Greece, where dance serves as a bridge between tradition and modernity, offering opportunities for both personal growth and cultural preservation.

1.5. Aim of the Study

The study aimed to examine the relationship between age, gender, residence, years of dancing experience, and dance style preferences among recreational dancers in Greece. Additionally, it sought to segment participants into distinct groups based on demographics, engagement metrics, and dance style preferences, with the goal of informing the development of personalized dance education, dance-based recreation, and culturally informed tourism programming.

The research hypotheses were as follows:

H1:

Age is associated with dance style preferences among recreational dancers.

H2:

Gender influences dance style preferences, with expected differences between male and female participants.

H3:

Place of residence (urban vs. rural) is associated with dance style preferences.

H4:

Years of dancing experience affect dance style preferences.

H5:

There is a positive correlation between participants’ age and their years of dancing experience.

H6:

Recreational dancers can be segmented into distinct profiles based on demographic characteristics, engagement variables, and dance style preferences.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study involved 912 recreational dancers recruited from dance studios and clubs participating in various dance styles across urban and rural centers, studios, and dance schools in Greece. Participants were eligible if they met the following criteria: (a) active participation in both individual and group dance practices and (b) being over 17 years of age. Individuals who did not meet these criteria were excluded.

Most of the participants were female (80.0%) and urban residents (58.4%). The largest age group was 17–29 years (45.2%), and the majority reported more than 8 years of dance experience (58.4%). Modern/contemporary dance was the most preferred style (24.5%), followed by traditional dance (19.5%) and ballet/classical dance (15.8%). Demographic characteristics, dance experience, and style preferences are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, dance experience, and style preferences.

2.2. Process

Participants completed a structured written questionnaire under the direct supervision of researchers at dance schools or studios prior to their practice sessions. They were informed beforehand that their responses would remain strictly anonymous. To ensure clarity and ease of completion, the questionnaire included detailed written instructions and was supplemented with oral explanations provided by the researchers. The study took place in professional settings, where instruction was delivered by experienced and certified dance educators. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Department of Physical Education and Sport Science, University of Thessaly (protocol No. 3-2/5.6.2024).

2.3. Data Preparation, Variable Transformation, and Statistical Analyses

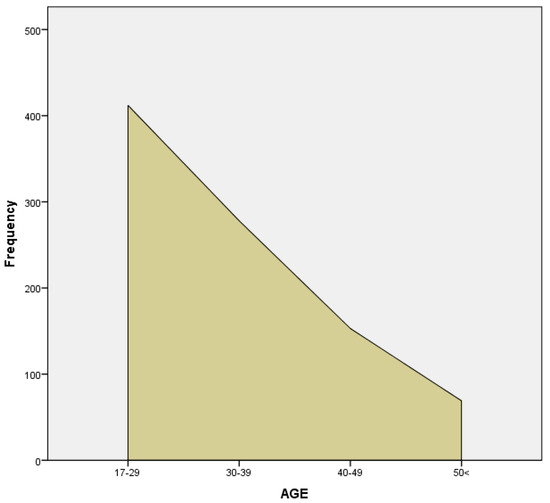

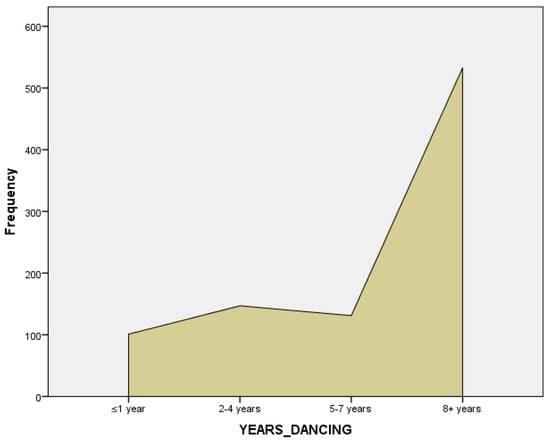

Prior to statistical analyses, all variables were systematically reviewed for accuracy, completeness, and missing values. Of the initial sample, 77 participants were excluded due to incomplete responses. The continuous variables, age and years of dancing experience, were assessed for distributional characteristics using histograms (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Histogram of age distribution.

Figure 2.

Histogram of years of dancing distribution.

Both variables exhibited clear deviations from normality. The age variable exhibited a left-skewed distribution, indicating a predominance of younger participants, while years of dancing experience showed a right-skewed distribution, suggesting a larger number of experienced dancers. Given the ordinal nature of these variables and the observed non-normal distributions, non-parametric statistical methods were applied throughout the analyses. Continuous variables (age and years of dancing experience) were normalized using min-max scaling to rescale values between 0 and 1, ensuring equal contribution to the distance-based clustering analysis [24]. Categorical variables, including gender, residence, and dance style preferences, were dummy-coded for analyses that required numerical input, particularly for clustering. Dance style preferences were recoded into binary variables (1 = preference, 0 = no preference) for each style, following established methodological standards [25].

Different statistical techniques were used to address the specific research hypotheses. To examine H1 through H4, which investigated associations between demographic variables (age, gender, residence, and years of dancing experience) and dance style preferences, crosstabulation analyses and chi-square tests were conducted. For each significant association, Cramér’s V was calculated to assess the strength of the relationship [26,27]. To test H5, which hypothesized a correlation between age and years of dancing experience, a Spearman correlation was performed, given the non-normal and ordinal nature of the variables. Finally, to address H6, k-means clustering analysis was applied to segment participants into distinct profiles based on demographics, experience levels, and stylistic preferences. The optimal number of clusters was determined using the elbow method, balancing model simplicity with explanatory power.

Post-segmentation analyses involved chi-square tests and Cramér’s V to assess associations between cluster membership and categorical variables (gender, residence, dance style preferences), and Kruskal–Wallis tests to identify differences across clusters for continuous variables (normalized age and years of dancing experience). For significant results, effect sizes (η2) were calculated using the formula η2 = H/(N − 1) [28]. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 28.0.

3. Results

3.1. Associations Between Demographic Characteristics and Dance Style Preferences—Crosstabulation Analyses

Crosstabulation analyses were performed to examine the associations between the following demographic characteristics: age, gender, residence, and years of dancing experience and participants’ dance style preferences. This approach enabled the identification of potential patterns and relationships, providing insights into how personal attributes may shape stylistic inclinations among recreational dancers.

3.1.1. Associations Between Age and Dance Style Preferences

Consistent with Hypothesis 1 (H1), a significant relationship was found between age and dance style preference, χ2(18) = 150.38, p < 0.001. Younger participants (17–29 years) were more inclined toward modern/contemporary dance (33.7%), whereas older participants (40–49 and 50+ years) demonstrated a preference for traditional dances (31.4% and 34.8%, respectively). Additionally, participation in tango increased with age, peaking among the 40–49 age group (22.2%). The effect size (Cramér’s V = 0.234) suggested a weak to moderate association between age and kind of dance.

3.1.2. Associations Between Gender and Dance Style Preferences

Supporting Hypothesis 2 (H2), a significant association was observed between gender and dance style preference, χ2(6) = 45.24, p < 0.001. Female participants primarily preferred ballet/classical (17.8%) and modern/contemporary (25.6%) styles, while male participants showed stronger preferences for traditional dance (22.5%) and tango (20.9%). The effect size, measured using Cramér’s V (V = 0.223), indicated a weak association between gender and dance style preferences.

3.1.3. Associations Between Residence and Dance Style Preferences

In line with Hypothesis 3 (H3), significant differences in dance preferences were identified based on participants’ place of residence, χ2(18) = 94.51, p < 0.001. Urban participants reported higher preferences for modern/contemporary (25.0%) and ballet/classical (19.9%) styles, whereas rural participants overwhelmingly preferred traditional dances (52.5%). The strength of the association was weak (Cramér’s V = 0.186).

3.1.4. Associations Between Years of Dancing Experience and Dance Style Preferences

Supporting Hypothesis 4 (H4), years of dancing experience were also significantly associated with dance style preference, χ2(18) = 138.69, p < 0.001. Participants with less than one year of experience preferred traditional dance (33.7%) and dance aerobics (26.7%), while those with eight or more years of experience primarily chose ballet/classical (21.2%) and modern/contemporary (25.7%) styles. The effect size (Cramér’s V = 0.225) indicated a weak to moderate association between years of dancing experience and dance style preference.

3.1.5. Correlations Between Age and Years of Dancing Experience

Supporting Hypothesis 5 (H5), a Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between age and years of dancing experience. This non-parametric method was chosen due to its suitability for analyzing ordinal variables and skewed distributions without requiring assumptions of linearity or normality.

The results revealed a statistically significant but weak positive correlation between age and years of dancing experience (rs = 0.072, p = 0.029). This indicates that older participants tended to have slightly more years of dancing experience; however, the strength of the relationship was minimal.

The analysis included a substantial sample (N = 912), enhancing the reliability of the findings. Despite the statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level, the small effect size suggests that age accounted for only a limited proportion of the variance in dancing experience. These results imply that other factors may have a more substantial influence on the accumulation of years of dance participation among recreational dancers.

3.2. Segmentation of Dancers Based on Demographics and Dance Style Preferences

3.2.1. Descriptive Statistics for Normalized Variables

A descriptive analysis was performed to summarize the characteristics of the variables age and years of dancing participation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for normalized variables (used in clustering analysis).

3.2.2. k-Means Cluster Analysis

Supporting Hypothesis 6 (H6), a k-means clustering analysis was conducted to segment participants into distinct groups based on demographic characteristics (gender, residence), years of dancing experience, and dance style preferences. The clustering solution revealed four meaningful profiles of recreational dancers, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of clusters based on demographics, dance style preferences, and experience.

3.2.3. Cluster Profiles

Cluster 1: Rural Experienced Female Participants

Cluster 1 comprised exclusively rural female participants, representing 33.6% of the sample (n = 306). This group demonstrated a strong preference for traditional (23%), modern dance (22%), and ballet (19%), with minimal interest in tango (8%) and aerial dance (7%). Participants in this cluster exhibited the highest years of dancing experience (normalized mean = 0.76) and moderate age (normalized mean = 0.31).

Cluster 2: Urban Male Beginners

Cluster 2 included urban male participants, constituting 11.9% of the sample (n = 109). Participants in this cluster demonstrated relatively lower years of dancing experience (normalized mean = 0.65) and a preference for traditional (24%), modern (21%), and tango (17%) dance styles. Minimal participation was observed in dance aerobics (5%).

Cluster 3: Urban Female Generalists

Cluster 3 represented urban female participants, accounting for the largest proportion of the sample (46.5%, n = 424). Participants exhibited diverse preferences, favoring modern dance (29%), ballet (17%), and traditional (16%) styles, with minimal interest in tango (8%) and aerial dance (7%). They were younger than average (normalized mean = 0.26) but had relatively high levels of dancing experience (normalized mean = 0.74).

Cluster 4: Urban Female Contemporary/Modern Dance Specialists

Cluster 4 included exclusively urban female participants, comprising 8.0% of the sample (n = 73). Participants in this cluster demonstrated a singular focus on modern dance (100%), with no reported participation in other dance styles. They were the youngest (normalized mean = 0.18) and showed the highest years of dancing experience (normalized mean = 0.78).

ANOVA diagnostics from the k-means clustering indicated significant differences across clusters for multiple dance styles: modern/contemporary (F = 247.23, p < 0.001), traditional (F = 8.87, p < 0.001), ballet (F = 12.54, p < 0.001), tango (F = 10.88, p < 0.001), and aerobic dance (F = 7.78, p < 0.001). Demographic variables, specifically gender and residence, effectively differentiated the clusters, with rural participants characterizing Cluster 1 and urban participants characterizing Clusters 2, 3, and 4.

3.3. Post-Segmentation Analysis: Associations Between Cluster Membership, Demographic Variables, Dance Style Preferences, and Engagement Metrics

Following the k-means clustering, post-segmentation analyses were conducted to explore associations between cluster membership and key demographic, behavioral, and engagement variables. Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables (gender, residence, dance style preferences), while Kruskal–Wallis tests assessed differences in continuous variables (age, years of dancing experience). Effect sizes were calculated using Cramér’s V and η2 to assess the strength of associations and differences.

3.3.1. Association Between Cluster Membership and Gender

A chi-square test revealed a highly significant association between cluster groups and gender (χ2(3) = 912.00, p < 0.001). The distribution of gender across clusters was highly uneven: Clusters 1, 3, and 4 consisted exclusively of female participants (100%), while Cluster 2 consisted exclusively of male participants (100%). The effect size, measured using Cramér’s V (V = 0.99), indicated a very strong association, highlighting that gender played a defining role in cluster differentiation.

3.3.2. Association Between Cluster Membership and Residence

The association between cluster membership and residence was also statistically significant, χ2(3) = 94.51, p < 0.001. Cluster 1 was composed entirely of rural participants (100%), while Clusters 2 and 3 were predominantly urban. Cluster 4 exhibited a more balanced distribution of urban and rural participants. The effect size (Cramér’s V = 0.186) indicated a weak association, suggesting that while residence influenced cluster formation, its role was less decisive compared to gender.

3.3.3. Association Between Cluster Groups and Dance Style Preferences

A chi-square test further revealed a significant association between cluster membership and dance style preferences, χ2(18) = 62.63, p < 0.001. Distinct stylistic preferences characterized each cluster (Table 4):

Table 4.

Statistical differences across clusters for demographic, dance style, and engagement variables.

Cluster 1 participants favored traditional (23.2%), modern/contemporary (21.6%), and ballet/classical (19.3%) styles.

Cluster 2 participants preferred traditional (23.9%), modern/contemporary (21.1%), and tango (16.5%).

Cluster 3 participants primarily favored modern/contemporary (28.5%), ballet/classical (16.7%), and traditional (15.6%) styles.

Cluster 4 participants demonstrated strong preferences for modern/contemporary (17.8%) and tango (27.4%).

The effect size (Cramér’s V = 0.234) indicated a weak to moderate association, suggesting that dance style preferences contributed to, but did not exclusively define, cluster membership.

3.3.4. Differences in Age and Years of Dancing Experience Across Clusters

Kruskal–Wallis tests were conducted to examine differences in the continuous variables age and years of dancing experience among the four clusters.

Age: The Kruskal–Wallis test revealed no significant differences in the distribution of age across clusters, H(3) = 5.56, p = 0.135. This result indicated that age was similarly distributed among the clusters. Consequently, the null hypothesis, that the distribution of age is the same across clusters, was retained.

Years of Dancing Experience: In contrast, the Kruskal–Wallis test identified a significant difference in years of dancing experience across clusters, H(3) = 8.26, p = 0.041. Thus, the null hypothesis was rejected, indicating that years of dancing experience varied significantly among the clusters.

The effect size (η2) was calculated to quantify the magnitude of the observed difference using the formula η2 = (H − k + 1)/(n − k), where H = 8.26, k = 4, and n = 912. The calculation revealed η2 ≈ 0.006, indicating a very small effect size. Although the difference in years of experience was statistically significant, its practical significance was minimal, suggesting that stylistic preferences and demographic characteristics played a more substantial role in cluster differentiation.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to examine how demographic characteristics (age, gender, and residence) and engagement-related factors (such as years of dancing experience) relate to dance style preferences among recreational dancers in Greece. Additionally, it sought to segment participants into meaningful profiles based on these variables and preferences. The findings confirmed several of the proposed hypotheses, revealing statistically significant associations between gender, age, and residence and participants’ stylistic choices. Moreover, cluster analysis identified distinct groups of dancers characterized by unique combinations of demographic traits and dance preferences. These results are discussed in relation to previous research and theoretical frameworks, offering both confirmation of existing patterns and new visions. The implications of these findings for dance education, and dance-based recreation and tourism programs design are also explored, along with directions for future research.

4.1. Gender and Dance Style Preferences

The results of this study indicated that gender plays an important role in shaping dance style preferences among recreational dancers. Female participants demonstrated stronger preferences for ballet/classical and modern/contemporary styles, while male participants favored traditional and tango dances. These findings support Hypothesis 2 (H2), suggesting that gender-based differences influence the selection of dance styles even at the recreational level.

Consistent with prior studies by Oliver et al. [12] and Andreoli [13], gender emerged as the most influential factor shaping dance preferences. The observed tendency for women to prefer ballet and modern/contemporary styles, and men to favor traditional dance and tango, reinforces established understandings of how socialization and cultural norms influence artistic preferences. These findings also align with Barreiro and Furnham [10], who emphasized the role of gendered stereotypes in shaping engagement with different dance genres. However, the present results extend prior work by demonstrating that gender differences persist even within recreational, non-professional settings, suggesting deep-rooted social influences on leisure choices.

The persistence of these preferences in leisure contexts suggested that gender-based expectations influenced not only professional or educational paths in dance, but also personal leisure activities. This observation was particularly relevant for dance educators and leisure tourism program designers, as it highlighted the importance of gender-sensitive pedagogical approaches that challenged traditional stereotypes and promoted inclusive participation across a wide range of dance genres.

4.2. Age and Dance Style Preferences

The findings demonstrated that age was significantly associated with dance style preferences among recreational dancers, supporting Hypothesis 1 (H1). Younger participants were more inclined toward high-energy and contemporary dance styles, such as modern/contemporary, while older participants showed stronger preferences for traditional dance and tango.

Age-related patterns in dance preferences similarly confirmed previous findings. Barreiro and Furnham [10] and Lovatt [8] reported that younger participants tend to prefer more energetic, innovative styles, while older individuals are drawn toward expressive or culturally rooted dance forms. This trend was evident in the current study, with younger dancers favoring modern/contemporary styles and older participants showing greater affinity for traditional dance and tango. Additionally, Hwang and Braun’s [16] assertion that older adults increasingly value the health and expressive benefits of dance participation was supported by the strong engagement with traditional forms among older participants.

The preference of older participants for traditional dances highlights the enduring cultural value of folk and heritage dances within the recreational dance community, even as newer generations favor contemporary forms. However, the observed effect size indicates a weak-to-moderate association. While statistically significant, these results suggest that age may be only one of several factors shaping stylistic preferences, and other variables such as motivations, cultural exposure, and social context, may play equally or more influential roles [3,4]. For dance education and tourism program design, these patterns suggest that age-specific preferences should be considered when planning curricula and recreational offerings, ensuring that programs both preserve cultural traditions and cater to the evolving tastes of younger dancers.

4.3. Residence and Dance Style Preferences

The study findings revealed that participants’ place of residence was associated with their dance style preferences, supporting Hypothesis 3 (H3). Residence was also a significant, although less dominant, factor influencing dance style preferences. Rural participants demonstrated a stronger preference for traditional dance forms, while urban participants tended to favor modern/contemporary and ballet/classical styles. These results are in line with prior research highlighting the role of cultural environment and exposure in shaping recreational dance choices.

In line with Filippou et al. [7] and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (2017), rural participants were more likely to favor traditional dance, reflecting cultural preservation and community identity, while urban participants’ inclination toward modern and ballet styles reflects broader global cultural and educational influences. The study by Sgoura et al. [11] confirms that cultural tourism events centered on traditional dance serve not only as a means of preserving local identity, but also as a motivation for active participation, social connection, and cultural recognition among dancers, particularly in rural areas. These results reinforce the need for culturally responsive teaching strategies, as emphasized by Masunah [20], that balance the preservation of local traditions with exposure to global trends. This also suggests that residential context continues to shape cultural and recreational practices despite increasing globalization.

For dance education and tourism program development, understanding these patterns emphasizes the importance of designing regionally responsive curricula. Educational initiatives should seek to celebrate and sustain traditional forms in rural areas while also providing urban dancers with opportunities to engage in both contemporary innovation and cultural preservation.

4.4. Years of Dancing Experience and Dance Style Preferences

The findings indicated that years of dancing experience were significantly associated with dance style preferences, supporting Hypothesis 4 (H4). Participants with more extensive dance experience showed a preference for more technically demanding styles, such as ballet/classical and modern/contemporary, whereas less experienced participants tended to favor accessible and community-oriented styles like traditional dance and dance aerobics.

The findings of the present study supported previous research by Zahiu et al. [23] and Barreiro and Furnham [10], who suggested that beginner dancers tend to prioritize accessible and socially oriented styles, while more experienced individuals are drawn to technically demanding and expressive forms. In line with these findings, the current study showed that less experienced participants preferred traditional dance and dance aerobics, whereas those with more years of experience gravitated toward ballet and modern/contemporary styles.

Although a statistically significant positive correlation was found between age and years of dancing experience, the relationship was weak. This weak correlation suggests that age alone may not be a strong predictor of accumulated experience among recreational dancers. This likely reflects the diverse entry points into recreational dance, where individuals begin at different life stages driven by varied motivations, such as socialization, cultural connection, or personal well-being [1,5]. This aligned with previous suggestions that dancing experience may be shaped by individual life circumstances and motivations rather than simply progressing with age [6,9]. Recreational dancers may begin their engagement at various life stages, driven by goals such as socialization, relaxation, or cultural connection.

These findings emphasized the importance of experience as a key factor in shaping dance preferences. For dance educators and tourism program designers, this highlighted the value of tiered program structures that cater to different experience levels, allowing both novice and advanced dancers to develop their skills, explore stylistic diversity, and maintain long-term participation.

4.5. Correlation Between Age and Years of Dancing Experience, Clustering Profiles, and Interpretations

The analysis revealed a statistically significant but weak positive correlation between age and years of dancing experience, supporting Hypothesis 5 (H5). Although older participants generally reported more years of dance experience, the correlation was weak, suggesting that age alone is not a strong predictor.

This finding resonated with previous research suggesting that age influences dance participation patterns, but not in a linear or deterministic way. For instance, Lovatt [8] mentioned that confidence in dance fluctuated across age groups, potentially affecting long-term engagement. Similarly, Maraz et al. [9] and Barreiro and Furnham [10] highlighted that motivations such as socialization, escape, and health benefits varied across the lifespan, influencing when and why individuals begin or continue dancing.

Therefore, in recreational dance populations, years of experience likely reflected personal motivations and life contexts rather than chronological age alone. This highlights the importance for dance education programs to be accessible and adaptable to all age groups, acknowledging that individuals may enter dance at different life stages with varying backgrounds and goals.

The clustering analysis segmented participants into four distinct profiles based on gender, residence, dance style preferences, and years of dancing experience, supporting Hypothesis 6 (H6). Each profile revealed unique combinations of demographic and stylistic characteristics that offered insights into participants’ cultural identities, engagement patterns, and educational needs.

Cluster 1. Rural Experienced Female Participants: This group consisted entirely of rural female participants with high levels of dancing experience and strong preferences for traditional, modern/contemporary, and ballet styles. Their engagement illustrated a sustained commitment to dance that blended cultural preservation with expressive exploration. The prominence of traditional dance within this group reaffirmed the role of rural settings in sustaining folk practices as part of collective identity [6,7]. At the same time, their interest in modern and ballet styles suggested an openness to creative development and technical refinement. For educational and tourism programming, this group would benefit from curricula that reinforce cultural continuity through traditional dance while also offering access to stylistically rich and expressive forms to support personal growth and sustained participation.

Cluster 2. Urban Male Beginners: This profile included urban male participants with relatively few years of dancing experience. Their stylistic preferences centered on traditional, modern/contemporary, and tango styles. This combination aligned with previous findings that male dancers often gravitate toward rhythm-based and partner-oriented forms [14], reflecting culturally embedded ideas about masculinity and movement. Their lower experience levels suggested a population at an early stage of recreational engagement, potentially facing social or cultural barriers to participation. For this group, educational programs should emphasize accessibility, inclusion, and social interaction, especially through beginner-level instruction in familiar or socially accepted styles. Creating male-supportive environments with attention to motivation and confidence-building could enhance retention and foster deeper engagement.

Cluster 3. Urban Female Generalists: Representing the largest segment of the sample, they included urban female dancers with diverse preferences across modern/contemporary, ballet, and traditional dance. With relatively high levels of experience, this group reflected both breadth and depth in their engagement. Their stylistic variety likely stemmed from greater exposure to multiple genres available in urban environments [15] and pointed to a recreational identity that embraced artistic diversity and versatility. Educational strategies for this group should emphasize advanced and cross-genre programming, offering opportunities for technical progression, choreographic exploration, and creative performance that align with their motivation for artistic expression.

Cluster 4. Urban Female Contemporary/Modern Dance Specialists: This cluster consisted of urban female dancers with the highest levels of dancing experience and a focused interest in contemporary/modern dance, along with notable engagement in tango. The data revealed no participation in ballet, suggesting that the group’s identity was instead anchored in expressive, emotionally driven, and possibly improvisational dance forms. Their exclusive stylistic focus may indicate a deep affinity with contemporary/modern dance values such as individuality and artistic autonomy. For this highly committed cluster, educational programs should offer intensive technical instruction, creative freedom, and mentorship opportunities. Their engagement patterns mirrored elements of semi-professional specialization, even within a recreational context, highlighting the need for advanced-level programming that supports personal expression and sustained artistic investment.

The clustering analysis revealed participant profiles that, in some cases, were defined by gender, with certain clusters consisting almost exclusively of male or female participants. This result highlights the strong predictive power of gender in shaping recreational dance preferences, a finding widely supported by existing literature demonstrating that social norms and gendered cultural expectations strongly influence dance engagement [1,14,29,30,31].

However, it is important to interpret these findings with caution due to the gender imbalance within the sample, where female participants represented a substantially larger proportion of respondents. Prior research on clustering and segmentation has shown that when datasets are unevenly distributed, clustering algorithms tend to overweight dominant variables, in this case, gender, potentially producing clusters that reflect sample distributions rather than revealing latent, multidimensional participant profiles [4,5]. As highlighted in leisure and cultural participation studies, factors such as intrinsic motivations, esthetic preferences, identity salience, and cultural belonging often play a crucial role in explaining individual engagement beyond demographics alone [3,5]

Overall, the cluster analysis demonstrated that recreational dancers form heterogeneous communities shaped by the intersection of gender, residence, experience, and stylistic orientation. These clusters reflected distinct cultural identities, whether rooted in tradition, urban eclecticism, or expressive modernism, as well as differing pathways of engagement with dance. The findings reinforced the importance of designing inclusive, differentiated, and culturally responsive dance programs that move beyond one-size-fits-all models. Recognizing and addressing these profiles can support lifelong participation, artistic development, and the preservation and evolution of dance as both cultural practice and personal expression.

Accordingly, the post-segmentation analysis confirmed the central role of gender, residence, and stylistic preferences in shaping distinct participant profiles. Gender emerged as the most decisive factor, while residence and years of experience contributed to secondary differentiation. These findings highlight the need to design inclusive, participant-centered recreational dance programs that move beyond one-size-fits-all models and address the specific educational and cultural needs of each profile. Integrating these insights into educational policy and practice can enhance cultural preservation, social engagement, and lifelong participation in recreational dance.

4.6. Practical Implications

The findings of this study offer important guidance for the development of participant-centered, culturally sensitive, and experience-appropriate dance programs. The identification of distinct clusters based on demographics, dance preferences, and experience levels highlights the necessity of moving beyond traditional age- or gender-based segmentation to more detailed program design strategies. Each identified participant cluster suggests specific educational needs and opportunities:

Rural Experienced Female Participants (Cluster 1) exhibited strong preferences for traditional, contemporary, modern, and ballet styles, alongside high levels of experience. Dance programs for this group should prioritize traditional dance workshops to maintain cultural continuity while also introducing ballet and modern dance modules to diversify technical skills and artistic exploration.

Urban Male Beginners (Cluster 2) demonstrated preferences for traditional, modern, and tango styles, coupled with lower experience levels. Programming for this group should emphasize beginner-level traditional and tango dance classes that foster accessibility, build confidence, and address barriers commonly faced by male dancers in recreational settings. Emphasizing a supportive and socially engaging environment would be critical to sustaining participation.

Urban Female Generalists (Cluster 3), who showed a broad interest in modern, contemporary, ballet, and traditional styles, combined with substantial experience, would benefit from diverse and advanced programming. Offering a range of technique classes and creative performance opportunities could support their versatility and encourage continued artistic growth.

Urban Female Contemporary/Modern Dance Specialists (Cluster 4), focused exclusively on modern, contemporary dance, with high levels of experience, would be best served by specialized, intensive programs. Masterclasses, technique refinement workshops, and artistic mentorships could meet the needs of this highly dedicated group.

4.7. Bridging Tradition and Innovation

The overall findings emphasize the critical role of dance participation as a bridge between cultural heritage and contemporary innovation. In rural areas, programs should reinforce traditional dances while introducing modern styles to promote artistic diversification. In urban settings, modern, contemporary, and ballet curricula should be enriched with elements of traditional dance to sustain cultural awareness and offer holistic development.

Given that age was not a major differentiating factor between clusters, program segmentation should not rely solely on chronological age. Instead, it should prioritize actual experience levels, motivational profiles, and stylistic interests. Beginner-friendly and advanced options should be available across all age groups, ensuring that personal development paths are respected and encouraged.

Finally, the observed variations in stylistic preferences across residence and gender highlight the need for culturally responsive curricula. Programs must be sensitive to local traditions while also offering exposure to a range of styles. Traditional dance festivals and events, especially those integrated into tourism programming, provide an effective bridge between heritage preservation and experiential learning. As mentioned by Sgoura et al. [11], these activities motivate participation not only through cultural expression but also through social engagement and identity reinforcement within a tourism framework. Incorporating motivational factors, such as social interaction, fitness, cultural connection, and artistic expression, into program design could enhance participant engagement, satisfaction, and lifelong participation.

Beyond methodological considerations, it is also important to mention the particularities of the Greek context. Greece has a long-standing and vibrant tradition of folk and community dance, where recreational participation is closely tied to cultural identity, social cohesion, and collective expression [6,7,19]. This contrasts with patterns in many European and North American contexts, where recreational dance is more often associated with studio-based training in genres such as ballet, jazz, or hip-hop [1,3]. Similarly, in Latin American countries, recreational dance often centers on social forms such as salsa, samba, or tango, which serve as both leisure practices and cultural markers [4,32].

These cross-cultural comparisons suggest that the Greek case highlights a dual role for recreational dance: simultaneously a means of cultural preservation through traditional practices and a contemporary leisure activity accessible to diverse groups. While the findings may therefore not be directly generalizable, they nonetheless resonate with international experiences where dance functions at the intersection of health, identity, and cultural expression [5].

4.8. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

While this study provides valuable insights into the relationship between demographic factors and dance style preferences, some limitations remain. The analysis focused primarily on demographic and engagement variables, without directly examining motivational factors such as social, cultural, or artistic motivations. Future research should incorporate motivational and psychological dimensions to develop a more comprehensive understanding of recreational dance engagement. Additionally, the study was conducted within a single national context, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Cross-cultural research would be beneficial to identify whether similar participant profiles and stylistic patterns emerge in different cultural environments. Future studies should explore motivational influences and expand to diverse cultural settings to deepen the understanding of recreational dance participation and inform inclusive educational practices.

Finally, the uneven gender distribution within the sample may have influenced the clustering results, as the overrepresentation of female participants can lead clustering algorithms to overweight gender as a primary distinguishing variable [4,5]. While the present study provides valuable insights into how demographic factors such as gender, age, residence, and years of experience shape dance style preferences, it does not directly examine participants’ motivations for engaging in recreational dance. Prior research has highlighted that social interaction, health benefits, emotional expression, and cultural belonging often play a critical role in shaping participation patterns [1,5]. Future research should therefore aim to combine balanced sampling strategies with segmentation models that integrate psychosocial, motivational, and cultural variables alongside demographics to detect hidden, multidimensional patterns of engagement and provide a more participant-centered understanding of recreational dance. Understanding how factors such as intrinsic enjoyment, social interaction, cultural belonging, and perceived health benefits influence participation can inform inclusive educational practices and culturally responsive tourism initiatives, while also revealing hidden engagement patterns that are not captured by demographics alone [4,9].

5. Conclusions

This study explored how demographic factors relate to dance style preferences among recreational dancers in Greece. The analysis revealed that gender, place of residence, and years of dancing experience significantly shape stylistic preferences, whereas age showed only a weak association. Through cluster analysis, four distinct participant profiles emerged, each reflecting different demographic patterns and levels of engagement with specific dance genres. One key finding was the strong influence of gender in determining dance identity, with entire clusters composed exclusively of either men or women. Additionally, participants from rural areas showed a consistent preference for traditional dance styles, closely linked to cultural expression and community life. More experienced dancers tended to identify more deeply with traditional forms, while urban participants displayed greater openness to contemporary styles. These findings reflect the unique cultural landscape of Greece, where recreational dance embodies both heritage preservation and contemporary expression, while also contributing to the broader international discourse on leisure, identity, and cultural engagement.

These insights emphasize the importance of designing inclusive and flexible programs that reflect the varying needs, experiences, and motivations of different dancer groups. Culturally responsive dance education and tourism initiatives that account for these differences can enhance participation, support cultural continuity, and strengthen the role of dance in social connection and identity. Future research should further investigate the underlying motivations for participation in recreational dance, especially in relation to cultural identity, locality, and tourism, to better inform inclusive practices in education, community planning, and cultural programming.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Z.; methodology, A.Z.; software, A.Z.; validation, A.Z., D.G., K.A. and G.Y.; formal analysis, A.Z.; investigation, A.Z.; resources, A.Z.; data curation, A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.Z., D.G., K.A. and G.Y.; visualization, A.Z.; supervision, A.Z., D.G., K.A. and G.Y.; project administration, A.Z. and D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board Internal Ethics Committee (IEC) of the Department of Physical Education and Sport Science (DPESS), University of Thessaly, Greece (University of Thessaly’s Code of Ethics, protocol number 2402, 5 June 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. Due to ethical and privacy considerations, the data will be shared in anonymized format upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study. The research was conducted independently, without any financial or personal relationships that could influence its outcomes.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the existing affiliation information. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Burkhardt, J.; Brennan, C. The Effects of Recreational Dance Interventions on the Health and Well-Being of Children and Young People: A Systematic Review. Arts Health 2012, 4, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontone, M.; Vause, T.; Zonneveld, K.L.M. Benefits of Recreational Dance and Behavior Analysis for Individuals with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Literature Review. Behav. Interv. 2021, 36, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.F.; Vartanian, M.; Sancho-Escanero, L.; Khorsandi, S.; Yazdi, S.H.N.; Farahi, F.; Borhani, K.; Gomila, A. A Practice-Inspired Mindset for Researching the Psychophysiological and Medical Health Effects of Recreational Dance (Dance Sport). Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 588948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong Yan, A.; Cobley, S.; Chan, C.; Pappas, E.; Nicholson, L.L.; Ward, R.E.; Murdoch, R.E.; Gu, Y.; Trevor, B.L.; Vassallo, A.J.; et al. The Effectiveness of Dance Interventions on Physical Health Outcomes Compared to Other Forms of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 933–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, K.; Redding, E.; Crickmay, U.; Stancliffe, R.; Jobbins, V.; Smith, S. The Aesthetic, Artistic and Creative Contributions of Dance for Health and Wellbeing across the Lifecourse: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2021, 16, 1950891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokka, S.; Mavridis, G.; Mavridou, Z.; Kelepouris, A.; Filippou, D.A. Traditional Dance as Recreational Activity: Teenagers’ Motives for Participation. Sport Sci. 2015, 8, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Filippou, F.; Goulimaris, D.; Mihaltsi, M.; Genti, M. Dance and Cultural Tourism: The Effect of Demographic Characteristics on Foreigners’ Participation in Traditional Greek Dancing Courses. Stud. Phys. Cult. Tour. 2010, 17, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lovatt, P. Dance Confidence, Age and Gender. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 50, 668–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraz, A.; Király, O.; Urbán, R.; Griffiths, M.D.; Demetrovics, Z. Why Do You Dance? Development of the Dance Motivation Inventory (DMI). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiro, C.A.; Furnham, A. Individual Differences as Predictors of Seven Dance Style Choices. Psychology 2019, 10, 916–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgoura, A.; Kontis, A.P.; Stergiou, D. Views and Motivations of Members of Dance Groups During Their Participation in Traditional Dance Tourist Events. In The International Conference on Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 441–447. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, W.; Risner, D. (Eds.) Dance and Gender: An Evidence-Based Approached; University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2017; ISBN 9780813062662. [Google Scholar]

- Andreoli, G.S. Dance and Gender Relations: A Reflection on the Interaction between Male and Female Students in Dance Classes. J. Educ. Soc. Policy 2019, 6, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronel, A.J.; Tiglao, R.M.; Solayao, R.; Lobo, J. Gender and Dance Motivation as Determinants of Dance Style Choice. Am. J. Arts Hum. Sci. 2022, 1, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Digital, Culture Media & Sport. Taking Part 2016/17: Dance Profile for Adults in England; Department for Digital, Culture Media & Sport: London, UK, 2017.

- Hwang, P.W.-N.; Braun, K.L. The Effectiveness of Dance Interventions to Improve Older Adults’ Health: A Systematic Literature Review. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2015, 21, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frömel, K.; Stratton, G.; Vasendova, J.; Pangrazi, R.P. Dance as a Fitness Activity the Impact of Teaching Style and Dance Form. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2002, 73, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musil, P.; Risner, D.; Schupp, K. (Eds.) Dancing Across the Lifespan; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-3-030-82865-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, S. Dance and Society: An Exploration of Cultural Expression and Social Impact. J. Humanit. Music. Danc. 2023, 3, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masunah, J. Multicultural Dance Education for Teaching Students with Disabilities. Multicult. Educ. 2016, 23, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sutiyono, S. Values of Multiculturalism in the Process of Teaching and Learning the Dance Arts. J. Stud. Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- McGreevy-Nichols, S.; Scheff, H. Teaching Cultural Diversity Through Dance. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2000, 71, 4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahiu, M.; Manos, M.; Drăghici, G.F. Coordination in Formation Dancesport at Beginner Level. Discobolul-Phys. Educ. Sport. Kinetother. J. 2020, 59, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, G.W.; Cooper, M.C. A Study of Standardization of Variables in Cluster Analysis. J. Classif. 1988, 5, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.A.R.; Solimun; Nurjannah. Computational Statistics with Dummy Variables. In Computational Statistics and Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cramér, H. A Contribution to the Theory of Statistical Estimation. Scand. Actuar. J. 1946, 1946, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, M.; Tomczak, E. The Need to Report Effect Size Estimates Revisited: An Overview of Some Recommended Measures of Effect Size. Trends Sport. Sci. 2014, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, W.; Risner, D. (Eds.) An Introduction to Dance and Gender. In Dance and Gender: An Evidence-Based Approached; University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Risner, D.; Oliver, W. 3. Behind the Curtain: Exploring Gender Equity in Dance among Choreographers and Artistic Directors. In Dance and Gender: An Evidence-Based Approach; University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael Aitchison, C. Gender and Leisure; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; ISBN 9781135135867. [Google Scholar]

- Kringelbach, H.N.; Skinner, J. Dancing Cultures: Globalization, Tourism and Identity in the Anthropology of Dance; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).