Social Support and Negative Emotions in the Process of Resilience: A Longitudinal Study of College Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Works

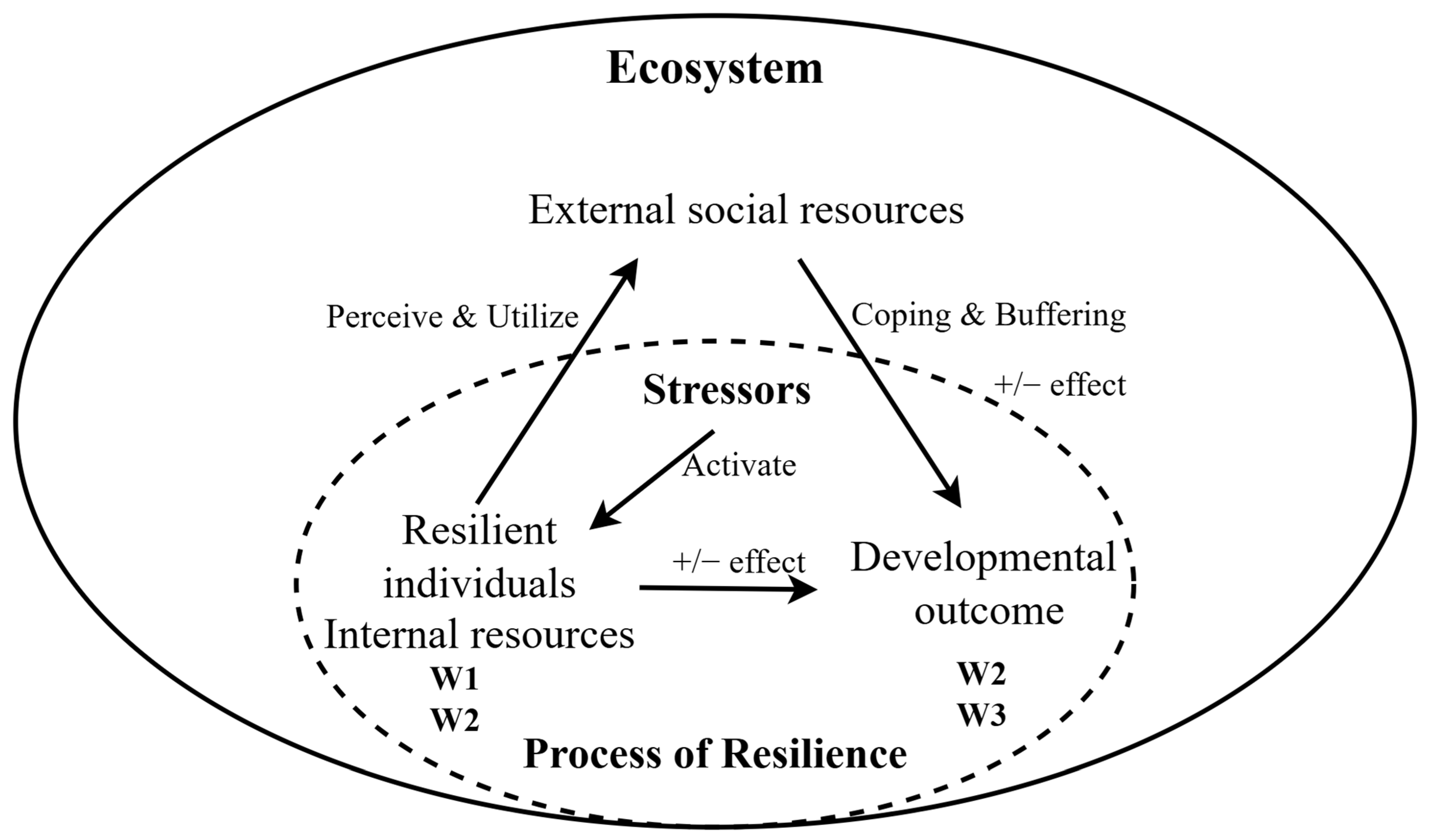

1.2. Theories and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias Assessment

3.2. Demographic Characteristics

3.3. Correlation Analysis

3.4. The RI-CLPM for Resilience, Social Support, and Negative Emotions

4. Discussion

4.1. Factors Influencing Resilience, Social Support, and Negative Emotions

4.2. Relationships Among Resilience, Social Support, and Negative Emotions over Time

4.3. Social Support Has Two Effects as a Dual Factor

4.4. Recommendations for Mental Health Works

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PR | psychological resilience |

| SS | social support |

| NE | negative emotions |

References

- O’Leary, K. Global increase in depression and anxiety. Nat. Med. 2021, 398, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Baierna, A.; Tan, C. Building an integrated mental health education system in schools. Chin. J. Sch. Health 2024, 45, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Gu, J.; Zhu, X.; Yang, M.; Shi, D.; Shang, J.; Zhao, F. Negative emotions and quality of life among adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2020, 20, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Lucke, C.M.; Nelson, K.M.; Stallworthy, I.C. Resilience in Development and Psychopathology: Multisystem Perspectives. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 17, 521–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, M. Philosophy in Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.W.; Schindler, D.E. Getting ahead of climate change for ecological adaptation and resilience. Science 2022, 376, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheffer, M.; Bolhuis, J.E.; Borsboom, D.; Buchman, T.G.; Gijzel, S.M.W.; Goulson, D.; Kammenga, J.E.; Kemp, B.; van deLeemput, I.A.; Levin, S.; et al. Quantifying resilience of humans and other animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 11883–11890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Dupre, M.E. Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cowen, P.J. Cortisol, serotonin and depression: All stressed out? Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 180, 99–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daviu, N.; Bruchas, M.R.; Moghaddam, B.; Sandi, C.; Beyeler, A. Neurobiological links between stress and anxiety. Neurobiol. Stress 2019, 11, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hounkpatin, H.O.; Wood, A.M.; Boyce, C.J.; Dunn, G. An Existential-Humanistic View of Personality Change: Co-Occurring Changes with Psychological Well-Being in a 10 Year Cohort Study. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 121, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windle, G. What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 2011, 21, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Rodríguez, F.M.; Martínez-Ramón, J.P.; Méndez, I.; Ruiz-Esteban, C. Stress, Coping, and Resilience Before and After COVID-19: A Predictive Model Based on Artificial Intelligence in the University Environment. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 647964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, H.L.; Vaingankar, J.A.; Abdin, E.; Sambasivam, R.; Fauziana, R.; Tan, M.-E.; Chong, S.A.; Goveas, R.R.; Chiam, P.C.; Subramaniam, M. Resilience and burden in caregivers of older adults: Moderating and mediating effects of perceived social support. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwick, S.M.; Sippel, L.; Krystal, J.; Charney, D.; Mayes, L.; Pietrzak, R.H. Why are some individuals more resilient than others: The role of social support. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salti, M.; Bergerbest, D. The Idiosyncrasy Principle: A New Look at Qualia. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 17, 1794–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckermann, A.; McLaughlin, B.P.; Walter, S. The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Mind; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S. Social Relationships and Health. Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldomini, M.; Lee, J.W.; Nelson, A.; Hwang, R.S.; Alharbi, K.K.; Sinky, T.H.; Quronfulah, B.S.; Khan, W.A.; Elamin, M.O.; Nour, M.O. The Moderating Role of Social Support on the Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences on Life Satisfaction and Mental Health in Adulthood. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2025, 32, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagnild, G.M.; Young, H.M. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. J. Nurs. Meas. 1993, 1, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham, J.E. Response Rates and Responsiveness for Surveys, Standards, and the Journal. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2008, 72, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, J.; Leppert, K.; Gunzelmann, T.; Strauß, B.; Brähler, E. Die Resilienzskala-Ein Fragebogen zur Erfassung der psychischen Widerstandsfähigkeit als Personmerkmal. Z. Klin. Psychol. Psychiatr. Psychother. 2005, 53, 16–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.H.; Yang, S.Q.; Margraf, J.; Zhang, X.C. Reliability and Validity Test for Wagnild and Young’s Resilience Scale (RS–11) in Chinese. China J. Health Psychol. 2013, 21, 1324–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fydrich, T.; Sommer, G.; Tydecks, S.; Brähler, E. Fragebogen zur sozialen Unterstützung (F-SozU): Normierung der Kurzform (K-14). (Social support questionnaire (F-SozU): Standardization of short form (K-14).). Z. Med. Psychol. 2009, 18, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The Structure of Negative Emotional States: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishara, A.J.; Hittner, J.B. Testing the significance of a correlation with nonnormal data: Comparison of Pearson, Spearman, transformation, and resampling approaches. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, D.G.; Bland, J.M. Standard deviations and standard errors. Br. Med. J. 2005, 331, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagerland, M.W. t-tests, non-parametric tests, and large studies—A paradox of statistical practice? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012, 12, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, H.A.; Simmering, M.J.; Sturman, M.C. A Tale of Three Perspectives: Examining Post Hoc Statistical Techniques for Detection and Correction of Common Method Variance. Organ. Res. Methods 2009, 12, 762–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozionelos, N.; Simmering, M.J. Methodological threat or myth? Evaluating the current state of evidence on common method variance in human resource management research. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2021, 32, 194–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson-Collentine, A.; van Assen, M.A.L.M.; Hartgerink, C.H.J. The Prevalence of Marginally Significant Results in Psychology Over Time. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 30, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merluzzi, T.V.; Philip, E.J.; Yang, M.; Heitzmann, C.A. Matching of received social support with need for support in adjusting to cancer and cancer survivorship. Psychooncology 2016, 25, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoadu, M.; Agormedah, E.K.; Obeng, P.; Srem-Sai, M.; Hagan, J.E., Jr.; Schack, T. Gender Differences in Academic Resilience and Well-Being Among Senior High School Students in Ghana: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Children 2024, 11, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goubet, K.E.; Chrysikou, E.G. Emotion Regulation Flexibility: Gender Differences in Context Sensitivity and Repertoire. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fancourt, D.; Aughterson, H.; Finn, S.; Walker, E.; Steptoe, A. How leisure activities affect health: A narrative review and multi-level theoretical framework of mechanisms of action. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagné, T.; Kurdi, V. Vegetarianism and mental health: Evidence from the 1970 British Cohort Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 351, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Sherman, D.K.; Taylor, S.E. Culture and social support. Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, R.; Espetvedt, M.N.; Lyshol, H.; Clench-Aas, J.; Myklestad, I. Mental distress among young adults–Gender differences in the role of social support. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, R.; Courtney, A.L.; Ferguson, I.; Brennan, C.; Zaki, J. A neural signature of social support mitigates negative emotion. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1987, 57, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, L.; Gaul, D.; Penco, R. Perceived Social Support and Stress: A Study of 1st Year Students in Ireland. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 21, 2101–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, M.; Linden-Carmichael, A.; Lanza, S. College Students’ Sense of Belonging and Mental Health Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 70, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P. Maslow, Abraham (1908–1970) and Hierarchy of Needs. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Interest Groups, Lobbying and Public Affairs; Harris, P., Bitonti, A., Fleisher, C.S., Binderkrantz, A.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Bian, F.; Zhu, Y. The relationship between social support and academic engagement among university students: The chain mediating effects of life satisfaction and academic motivation. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, F.; Li, J.; Xin, W.; Cai, N. Impact of social support on the resilience of youth: Mediating effects of coping styles. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1331813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J. Social connection as a critical factor for mental and physical health: Evidence, trends, challenges, and future implications. World Psychiatry 2024, 23, 312–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | N | W1PR | W1SS | W1NE | N | W2PR | W2SS | W2NE | N | W3PR | W3SS | W3NE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 816 | 58.29 ± 9.840 | 56.64 ± 9.972 | 7.71 ± 9.631 | 816 | 57.81 ± 14.309 | 53.89 ± 12.267 | 18.81 ± 17.573 | 816 | 56.21 ± 14.235 | 51.94 ± 12.494 | 39.85 ± 17.570 |

| Female | 679 | 57.57 ± 9.813 | 58.27 ± 9.529 | 6.13 ± 8.165 | 679 | 57.43 ± 10.791 | 55.37 ± 10.653 | 11.52 ± 13.099 | 679 | 55.95 ± 11.473 | 53.61 ± 11.047 | 33.19 ± 14.252 |

| p | 0.159 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.560 | 0.013 | 0.001 | 0.701 | 0.006 | <0.001 | |||

| Travel frequency | ||||||||||||

| Not have | 889 | 56.47 ± 9.709 | 56.06 ± 9.934 | 7.46 ± 8.748 | 858 | 56.73 ± 13.089 | 53.53 ± 11.665 | 16.72 ± 16.592 | 967 | 55.04 ± 12.971 | 51.39 ± 11.704 | 38.2 ± 16.88 |

| Once or more | 606 | 60.16 ± 9.601 | 59.3 ± 9.289 | 6.31 ± 9.385 | 637 | 58.86 ± 12.375 | 55.96 ± 11.328 | 13.85 ± 15.294 | 528 | 58.02 ± 12.986 | 55.08 ± 11.854 | 34.3 ± 15.421 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.016 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Vegetarian or not | ||||||||||||

| Not a vegetarian | 910 | 58.02 ± 9.771 | 57.87 ± 9.653 | 6.52 ± 8.197 | 961 | 57.65 ± 11.693 | 54.8 ± 11.174 | 13.3 ± 14.403 | 1036 | 55.92 ± 12.725 | 52.72 ± 11.862 | 34.41 ± 14.999 |

| No fish or/and meat | 585 | 57.88 ± 9.931 | 56.61 ± 9.995 | 7.73 ± 10.146 | 534 | 57.61 ± 14.664 | 54.15 ± 12.28 | 19.45 ± 18.15 | 459 | 56.48 ± 13.761 | 52.64 ± 11.947 | 42.27 ± 18.293 |

| p | 0.791 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.953 | 0.300 | <0.001 | 0.459 | 0.902 | <0.001 |

| Variable | W1PR | W1SS | W1NE | W2PR | W2SS | W2NE | W3PR | W3SS | W3NE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1PR | 1 | ||||||||

| W1SS | 0.378 *** | 1 | |||||||

| W1NE | 0.353 *** | 0.410 *** | 1 | ||||||

| W2PR | 0.641 *** | 0.295 *** | 0.313 *** | 1 | |||||

| W2SS | 0.352 *** | 0.714 *** | 0.365 *** | 0.425 *** | 1 | ||||

| W2NE | 0.319 *** | 0.351 *** | 0.779 *** | 0.390 *** | 0.441 *** | 1 | |||

| W3PR | −0.491 *** | −0.238 *** | −0.246 *** | −0.439 *** | −0.260 *** | −0.248 *** | 1 | ||

| W3SS | −0.290 *** | −0.267 *** | −0.284 *** | −0.287 *** | −0.314 *** | −0.291 *** | 0.384 *** | 1 | |

| W3NE | −0.244 *** | −0.209 *** | −0.304 *** | −0.237 *** | −0.238 *** | −0.314 *** | 0.320 *** | 0.479 *** | 1 |

| 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Outcome | p | Low | Up | Standardized Coefficient |

| Autoregressive | |||||

| W_R1 | W_R2 | 0.001 | 0.062 | 0.225 | 0.098 |

| W_R2 | W_R3 | 0.000 | 0.062 | 0.225 | 0.143 |

| W_S1 | W_S2 | 0.007 | 0.034 | 0.212 | 0.095 |

| W_S2 | W_S3 | 0.008 | 0.034 | 0.212 | 0.120 |

| W_N1 | W_N2 | 0.000 | 0.313 | 0.421 | 0.184 |

| W_N2 | W_N3 | 0.000 | 0.313 | 0.421 | 0.366 |

| Cross-lagged | |||||

| W_S1 | W_N2 | 0.008 | −0.337 | −0.050 | −0.096 |

| W_N2 | W_R3 | 0.000 | −0.155 | −0.067 | −0.148 |

| W_N2 | W_S3 | 0.000 | −0.144 | −0.064 | −0.159 |

| Trait Covariances | |||||

| R_trait | S_trait | 0.000 | 24.985 | 37.299 | 0.858 |

| R_trait | N_trait | 0.000 | −26.153 | −13.210 | −0.705 |

| S_trait | N_trait | 0.000 | −23.122 | −11.042 | −0.597 |

| Gender | S_trait | 0.002 | 0.508 | 2.218 | 0.111 |

| Gender | N_trait | 0.000 | −3.591 | −1.840 | −0.277 |

| WP Contemporaneous Covariances | |||||

| W_R1 | W_S1 | 0.000 | 25.172 | 37.947 | 0.527 |

| W_S1 | W_N1 | 0.000 | −22.706 | −9.932 | −0.278 |

| W_R1 | W_N1 | 0.000 | −24.756 | −11.086 | −0.297 |

| W_R2 | W_S2 | 0.000 | 68.060 | 86.157 | 0.693 |

| W_S2 | W_N2 | 0.000 | −24.465 | −6.759 | −0.108 |

| W_R2 | W_N2 | 0.028 | −21.296 | −1.122 | −0.066 |

| W_R3 | W_S3 | 0.000 | 76.182 | 92.206 | 0.771 |

| W_S3 | W_N3 | 0.069 | −15.153 | 0.614 | −0.052 |

| W_R3 | W_N3 | 0.317 | −13.261 | 4.312 | −0.028 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Chen, H. Social Support and Negative Emotions in the Process of Resilience: A Longitudinal Study of College Students. Societies 2025, 15, 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15090238

Zhang Y, Chen H. Social Support and Negative Emotions in the Process of Resilience: A Longitudinal Study of College Students. Societies. 2025; 15(9):238. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15090238

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yuqi, and Hongshuo Chen. 2025. "Social Support and Negative Emotions in the Process of Resilience: A Longitudinal Study of College Students" Societies 15, no. 9: 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15090238

APA StyleZhang, Y., & Chen, H. (2025). Social Support and Negative Emotions in the Process of Resilience: A Longitudinal Study of College Students. Societies, 15(9), 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15090238