Mapping (In)Formal Francophone Spaces: Exploring Community Cohesion Through a Mobilities Lens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Geographically Shaped Mobilities

Afterwards, the school [in the Francophone school board] where I primarily work, is here. […] I try to go by bike, but it’s really like up and down [hilly]. Sometimes I abandon all, I take the car, sometimes I take the bus but it’s like two buses and each time that I arrive here, the other one passes me by. […] So I can take the bus to go. But, yeah it’s not easy, if not, a bus I use a lot is [bus route number]. And, in reality because I really love—yeah or otherwise I go by bike. The street [X], it’s like one of the areas that I use most […], it’s really a magnificent cycling trail.

It’s a community cycling shop, so a cycling shop that doesn’t belong to a private entity, that belongs to volunteers. It doesn’t have the goal to make a profit, in fact, they are community cycling shops, and so the goal is to, at once, to provide a means of transportation by bike and to, you can learn bike mechanics very easily in fact.

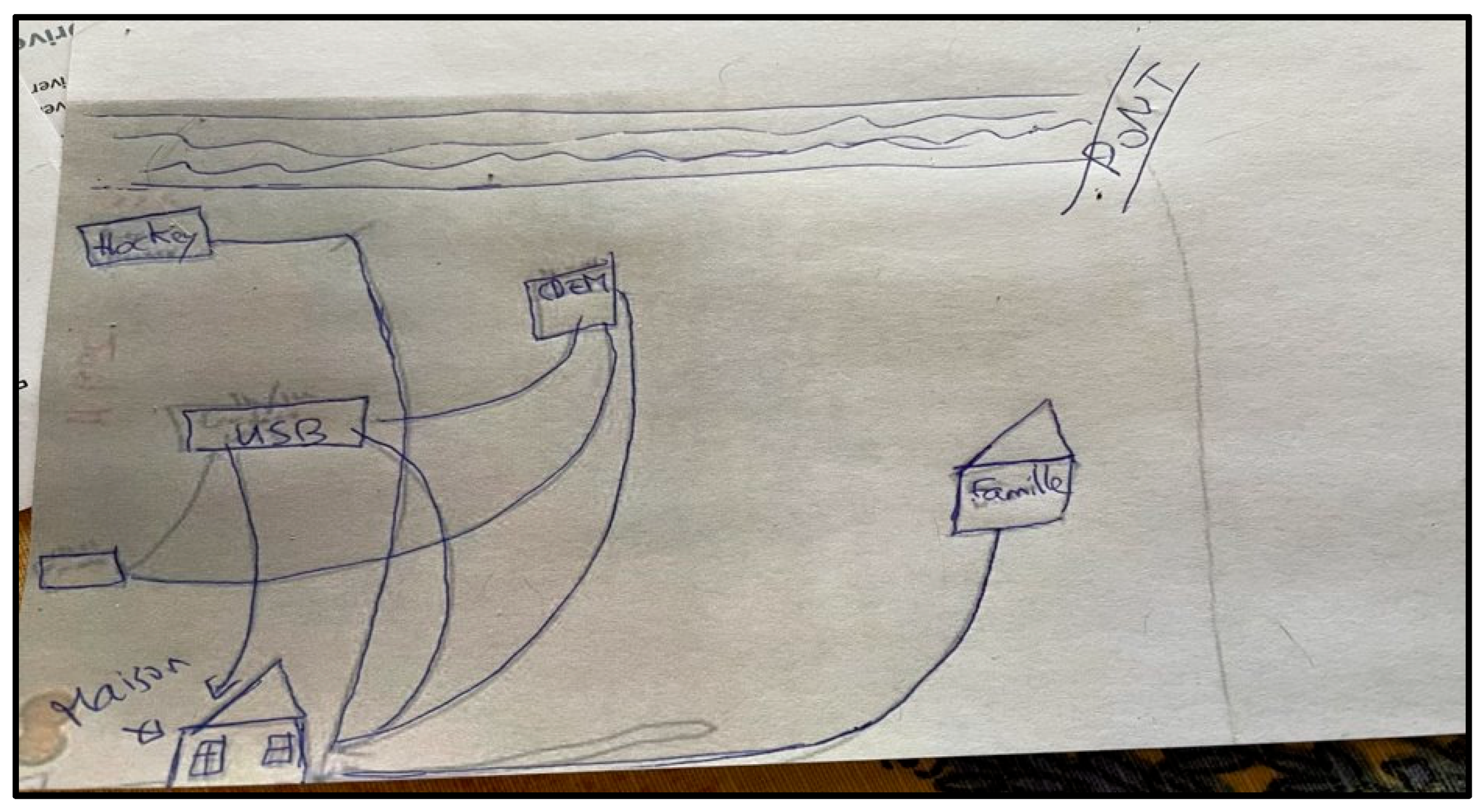

Early here just around 9:00 at the USB [Université Saint-Boniface]. And it’s important that it’s in French, because if not they won’t understand. Same thing when we talk about swimming lessons, when we want to enroll in things like that. The courses have to be in French, otherwise you won’t understand. So the daycare, then I go to the USB and then I cross the street and I go to the office that is just 5 min from here […].

[Interviewer: So for the moment, the vast majority of your local travels are in relation to work […] at Saint-Boniface?] That’s right. So I live in the small community of LaSalle. That is about […] So that, it’s a route that is, let’s say 40- to 45 min. You said you were interested in knowing how I get there then. […] So we go, we would be in a car, there is no bus service, so I come here for work. So that’s, for the moment, that was the case, and has been the case since I was hired, so it’s 5 days a week. Apart from that, my travels are not very numerous. I will go to church.

During a normal work week, I get up early in the morning to go pray at the mosque. Before, I prayed at the University mosque, but now I come to the mosque that is closest to where I live. And I return home to have breakfast and I go to the [auto shop] situated in [town] twice a week for the purchase of cars or car parts since I buy used or damaged cars and I repair and resell them. That’s why I go to [name]’s garage in [town]. I also frequent a lot of social media sites to buy and sell cars.

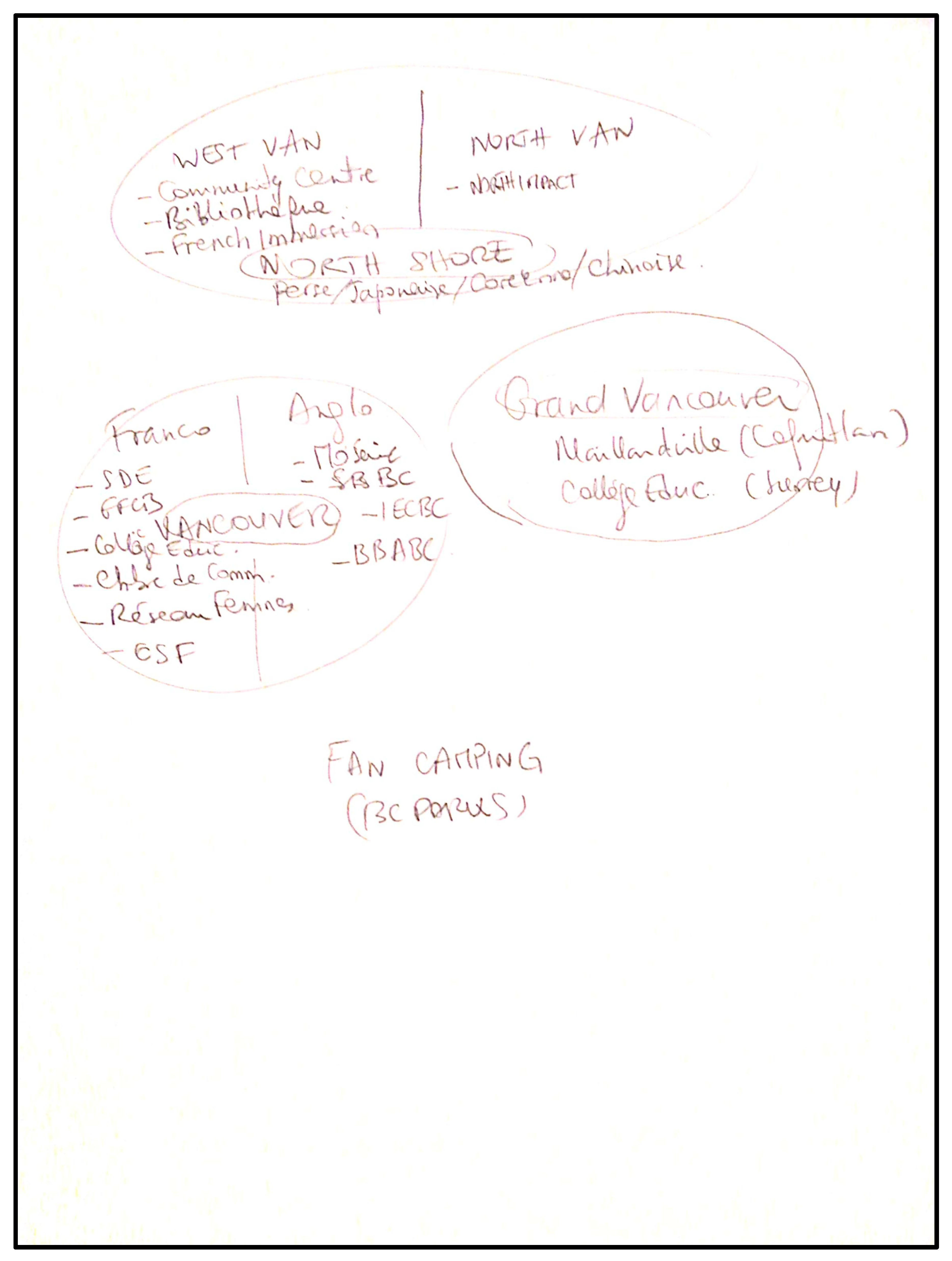

3.2. (In)Formal Francophone Spaces

At the time, it was a lot simpler for me because I was in [specific neighbourhood], it was practically every month. […] the Chamber of Commerce did what we called at the time also a 6 to 8. So, I went regularly, so the Chamber of Commerce, I was never a member, given the fact, the membership criteria are that you have to be an entrepreneur. So, I participated […] in the events, without having any particular status in the structure. And same for the [economic organization] it was as … I was very interested in all their events, whether it be events tied to entrepreneurs, whether it be events tied to economic immigration.

I listen to Radio-Canada, to feel part of the community [laughs], despite finding that still a bit… it’s a bit false, but still [Interviewer: A bit false in what sense?] Well in the sense that it’s random news. You know there is one of the local discussions, but it’s not… I get the impression that I am part of the community, because Radio-Canada, I think I make myself believe that it connects me, but I get the sense that it doesn’t connect me that much.

We always had visits from families from France and I said, “[Mother-in-law], come with me, you will be my entry” (laughs) so she helped me to speak to people and she presented me to everyone, “I’m introducing you to [name]”, that was my entry, with the mothers’ group, we did evenings with mothers in restaurants downtown [Interviewer: It’s informal? Or is there not an organization?] Yes it’s informal it’s the mothers who organize […] [Interviewer: People you met at [Francophone playgroup for toddlers]?] Exactly, mothers who now continue to work in the community, they are professors, they work in daycares, child care services, always in the community, from time to time, I see their updates on Facebook. When I did my daughter’s third birthday, I invited everyone and they are all there.

And sometimes I go once a month or else once in a while to the cultural activities… the [ethnic] community, I see them once a month. But we don’t meet up in Saint-Boniface, we meet in people’s homes… So everyone lives a bit everywhere. […] Francophone community activities are maybe once every three months and that’s in Saint-Boniface. […] There is for example at the [community space] like at the Molière circle, theatre […] or a music concert, or else it’s a reunion, so it’s things like that.

The first thing that comes to mind is the environment at the Université de Moncton. Especially in post-graduate studies, there is a large division between international students and students who are White and born in Canada. That is physically visible in classrooms. It’s literally divided. There are very few interactions, there is an atmosphere of people not wanting to go into projects or to mix with people they don’t know.

She elaborated further on this point, going on to explain that:

I’ve mostly observed it in civil society, I worked for an organization where the head of that organization for a long time, there was a racialized woman who was the executive director. She was excellent, she was fabulous and she received a lot of criticism from members of the organization and other people in the civil society environment […]. Like the things they said implied that because she came from elsewhere, she didn’t understand. It was maybe her culture, it was maybe this, it was maybe her accent. But when I wanted to address those things, like what do you really mean by ‘she doesn’t understand how things work here?’ People don’t want to address that.

I have had Acadian acquaintances at the church in Shediac for years, it is a congregation with Acadians. But outside of that space, we will pretend to continue the relationship elsewhere but it doesn’t work. Since these are not friendships as such, it’s really always in a context. We will meet, yes, we laugh, then it’s over. We get together for such and such an event, then it’s over. We will see each other, greet each other, but there is no such bond of friendship.

3.3. Convergent and Divergent Mobilities

[…] the Francophone spaces that I frequent are mostly immigrants or who have a connection with immigration otherwise there’s no mixing. For example, one, my boss when I worked for the government, our kids were on the same soccer team but we were never together. Another example, I met an Acadian and I invited to a date. He was supposed to call me back, but he never did. I asked him why and he said that it wasn’t a good match him and I, but maybe I asked myself is it because I don’t see myself with his network?

I would really like to have Canadian friends, but it’s so difficult to have Canadian friends despite, I have a [friend] who likes being social with everyone. But born and raised in Canada. Here, it was pretty complicated. There are groups and you have to be part of the group. I find that if there is something that is really missing, it’s that. I find … in Europe, you can go out and make friends like that, here, it’s hard. It’s really groups […] I find that a bit unfortunate, everyone keeps to themselves a bit. Or it’s groups. You have your cinema group. You have your sport group. You have your drinking group.

With the Québécois, I don’t know, I have a very good friend who is Québécois […]. But’s it’s a Québécois who is well travelled, he is very open to other cultures. I get the impression that here the Québécois are very close, in a group. My Québécois friend, him, already he feels Canadian in fact, so, here, I’ve met some Québécois, who tell me they feel more Québécois than Canadian. There, it’s a little barrier that they put between us.

There are some who have left, we have … well yes, yes, essentially my friends are Francophone yes. Yes, that I tell myself we should panic a bit, that we should meet some Anglophones. [Interviewer: But why?] Well I don’t know, just to say … yesterday I was making a film of my best friend who came here and who sees that all my friends are French … who tells me “you went to the other end of the world…” [Interviewer: when you say Francophone or French?] It would essentially be French.

We’re reproducing the Senegal here, my country of origin here. So as long as I’m at the university, I speak French. Whereas when I’m outside it. Since it’s English, the first sentiment, is that I close in on myself because I can’t communicate… but outside of my workplace, it’s with my network that is mainly composed of Senegalese people.

Sometimes, it depends. It’s pretty flexible how I can organize my days. In general, every Wednesday I am in [city]. And three days a week I am at [public school]. And I work from home one day a week. But I also have like this morning, I was in [city] at the Community Center, and that’s just next to, a garden complex where most of the families that I accompany work, so it’s a large immigrant community, a lot of Francophones.

I have built myself a nice little ideal life I can say, it’s the child, a family dog, wife, French. It’s good, I do, I like what I do. And it’s thanks to studying, working. I could have taken courses at the University of Manitoba. A lot, they start at USB, and they go to the UofM and I think it’s ridiculous, that’s me, I don’t like that, it’s here, you stay here, and really it’s… choices, decisions, and I have positioned myself ok, perfectly so that my children can grow up in French.

I drop my children off at daycare [Interviewer: and it’s in French the daycare?] Yes. [Interviewer: Is that a choice that you made?] Yes, yes. [Interviewer: And it’s close also to where you live?] No. It’s not close to where I live. [Interviewer: But you really want him to be in a French-language daycare?] Yes, it’s just that I lived in Saint-Boniface, before and. I don’t know, I didn’t have a very good experience in Saint-Boniface. So, we moved elsewhere because we are more involved in the community where I live.

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Standing Senate Committee on Official Languages (SSCOL). Seizing the Opportunity: The Role of Communities in a Constantly Changing Immigration System; Parliament of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages & Office of the French Language Services Commissioner of Ontario (OCOL & OFLSC). Time to Act for the Future of Francophone Communities: Redressing the Immigration Imbalance; Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014.

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). Policy on Francophone Immigration; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024.

- Government of Canada. Official Languages and Communities. Ottawa, Canada, 2024. Available online: https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/communaction/en/official-languages-and-communities (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, SC 2001, c 27. Available online: https://canlii.ca/t/53z6t (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Parliament of Canada. Bill C-13: An Act to Amend the Official Languages Act, to Enact the Use of French in Federally Regulated Private Businesses Act and to Make Related Amendments to Other Acts. Ottawa, Canada, 2023. Available online: www.ourcommons.ca (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). Ambitious and Historic Measures to Enhance the Vitality of Francophone Minority Communities in Canada. 2024. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/news/2024/01/ambitious-and-historic-measures-to-enhance-the-vitality-of-francophone-minority-communities-in-canada.html (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Iacovino, R.; Léger, R. Francophone minority communities and immigrant integration in Canada: Rethinking the normative foundations. Can. Ethn. Stud. 2013, 45, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madibbo, A. The Way Forward: African Francophone Immigrants Negotiate Their Multiple Minority Identities. Int. Migr. Integr. 2016, 17, 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronis, L.; Huot, S. Imaginaires géographiques de la francophonie minoritaire canadienne chez les immigrants et réfugiés d’expression française. Diversité Urbaine 2019, 19, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mianda, G. Genre, langue et race: L’expérience d’une triple marginalité dans l’intégration des immigrants francophones originaires de l’Afrique subsaharienne à Toronto, Canada. Francoph. D’amérique 2018, 46–47, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huot, S.; Veronis, L. Examining the role of minority community spaces for enabling migrants’ performance of intersectional identities through occupation. J. Occup. Sci. 2018, 28, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piquemal, N.; Zellama, F.; Sall, L.; Rivard, E.; Bolivar, B. Immigration, intégration et marqueurs sociaux au Manitoba: Identité et rapport autre. Cah. Fr.-Can. De L’ouest 2023, 35, 365–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huot, S.; Veronis, L.; Sall, L.; Piquemal, N.; Zellama, F. Favoriser la Cohésion Communautaire Dans un Contexte de Diversité. Report Prepared for the Fédération des Communautés Francophones et Acadienne du Canada. 2020. Available online: https://immigrationfrancophone.ca/directory-documents/documents/favoriser-la-cohesion-communautaire-dans-un-contexte-de-diversite/ (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Huot, S.; Veronis, L.; Sall, L.; Piquemal, N.; Zellama, F. Prioritising community cohesion to promote immigrant retention: The politics of belonging in Canadian Francophone minority communities. J. Int. Migr. Int. 2023, 24 (Suppl. S6), 1121–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourot, A.-C. Comparing ambiguities: Municipalities, Francophone minority communities and immigration in Canada. Can. J. Political Sci. 2021, 54, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violette, I. L’immigration francophone comme marché: Luttes et tensions autour de la valeur des langues officielles et du bilinguisme en Acadie, Canada. Anthropol. Sociétés 2015, 39, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwakongnwi, E.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Musto, R.; Quan, H.; King-Shier, K.M. Experiences of French speaking immigrants and non-immigrants accessing health care services in a large Canadian city. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 3755–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liboy, M.-G.; Patouma, J. L’école francophone en milieu minoritaire est-elle apte à intégrer les élèves immigrants et réfugiés récemment arrivés au pays? Can. Ethn. Stud. 2021, 53, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masinda, M.T.; Jacquet, M.; Moore, D. An integrated framework for immigrant children and youth’s school integration: A focus on African Francophone students in British Columbia, Canada. Int. J. Educ. 2014, 6, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaisse, A.-C.; Huot, S.; Veronis, L.; Mortenson, W.B. Occupation’s role in producing inclusive spaces: Immigrants’ experiences in linguistic minority communities. OTJR 2021, 41, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronis, L.; Huot, S. La pluralisation des espaces communautaires francophones en situation minoritaire: Défis et opportunités pour l’intégration sociale et culturelle des immigrants. Francoph. D’amérique 2019, 46–47, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaisse, A.-C.; Veronis, L.; Huot, S. The ‘in-between’ role of linguistic minority sites in immigrants’ integration: The Francophone community as a third space in Metro Vancouver. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2024, 25, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannam, K.; Sheller, M.; Urry, J. Editorial: Mobilities, immobilities and moorings. Mobilities 2006, 1, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheller, M.; Urry, J. (Eds.) Tourism Mobilities: Places to Play, Places in Play; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Waite, L. A place and space for a critical geography of precarity? Geogr. Compass 2009, 3, 412–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.J.; Hall, T. Pedestrian circulations: Urban ethnography, the mobilities paradigm and outreach work. Mobilities 2016, 11, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaño, Y.; Mittmasser, C.; Sandoz, L. Spatial mobility capital: A valuable resource for the social mobility of border-crossing migrant entrepreneurs? Societies 2022, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In The Sociology of Economic Life; Granovetter, M., Swedberg, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Holtug, N.; Mason, A. Introduction: Immigration, diversity and social cohesion. Ethnicities 2010, 10, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, J.; O’Sullivan, A. Civility, community cohesion and antisocial behaviour: Policy and social harmony. J. Soc. Policy 2013, 42, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffikin, F.; Morrissey, M. Community cohesion and social inclusion: Unravelling a complex relationship. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 1089–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassiter, L.E.; Campbell, E. What will we have ethnography do? Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, R.; Marterella, A. Community-engaged research: A path for occupational science in the changing university landscape. J. Occup. Sci. 2014, 21, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huot, S.; Laliberte Rudman, D. Extending beyond qualitative interviewing to illuminate the tacit nature of everyday occupation: Occupational mapping and participatory occupation methods. OTJR Occup. Ther. J. Res. 2015, 35, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaisse, A.-C.; Huot, S.; Piquemal, N.; Sall, L. The instrumentalization of French-speaking immigration in Canada within a colonial and economistic approach: A critical discourse analysis. Can. Ethn. Stud. 2025, 57, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaisse, A.-C.; Huot, S. Réflexions sur les dynamiques coloniales: Perspectives au sein de la francophonie du Grand Vancouver. Enjeux Société 2025, 12, 150–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piquemal, N.; Delaisse, A.-C.; Sall, L.; Zellama, F.; Huot, S. Francophonie contestée et enjeux d’appartenance: Francophones d’ici et d’ailleurs. Cah. Fr.-Can. De L’ouest, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin, M. Understanding illness: Using drawings as a research method. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 272–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLees, L. A postcolonial approach to urban studies: Interviews, mental maps, and photo voices on the urban farms of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Prof. Geogr. 2013, 65, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S.; Gilligan, C. Visualising migration and social division: Insights from social sciences and the visual arts. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2010, 11, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, K. Making sense of place: Mapping as a multisensory research method. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Besten, O. Visualising social divisions in Berlin: Children’s after-school activities in two contrasted city neighbourhoods. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2010, 11, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Census Profile. 2021 Census of Population. Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 98-316-X2021001. Ottawa. Released 15 November 2023. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&SearchText=vancouver&DGUIDlist=2021S0503933&GENDERlist=1,2,3&STATISTIClist=1,4&HEADERlist=0 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Statistics Canada. Census Profile. 2021 Census of Population. Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 98-316-X2021001. Ottawa. Released 15 November 2023. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&SearchText=winnipeg&DGUIDlist=2021S0503602&GENDERlist=1,2,3&STATISTIClist=1,4&HEADERlist=0 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Statistics Canada. Census Profile. 2021 Census of Population. Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 98-316-X2021001. Ottawa. Released 15 November 2023. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&SearchText=moncton&DGUIDlist=2021S0503305&GENDERlist=1,2,3&STATISTIClist=1,4&HEADERlist=0 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Violette, I.; Boudreau, A. Linguistic issues of Francophone immigration in Acadian New Brunswick. Can. Issues 2008, Spring, 121–124. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/208679069/D6C2DBA7B9D24619PQ/35?accountid=14656&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Granovetter, M. The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited. Sociol. Theory 1983, 1, 201–233. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/202051 (accessed on 18 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Jenson, J. Mapping Social Cohesion: The State of Canadian Research; Canadian Policy Research Networks Inc.: Ontario, ON, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ariely, G. Does diversity erode social cohesion? Conceptual and methodological issues. Political Stud. 2014, 62, 573–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkhodja, C. Immigration and diversity in Francophone minority communities: Introduction. Can. Issues 2008, Spring, 3–5. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/3253447b09fe5ecf21946d323c0b7cf8/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=43874 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Delaisse, A.-C.; Huot, S.; Veronis, L. Cohésion communautaire et distanciations socio-raciales dans la communauté francophone du Grand Vancouver. Cah. Fr.-Can. De L’ouest 2023, 35, 331–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sall, L.; Veronis, L.; Huot, S.; Piquemal, N.; Zellama, F. Immigration et francophonies minoritaires canadiennes: Les apories de la cohésion sociale. Francoph. D’amérique 2021, 51, 87–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1993, 43, 1241–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mianda, G. Migration and the paradox of Canadian bilingualism: The experience of Sub-Saharan African Francophone immigrants in the minoritized Francophone community of the GTA. In Reconstructions of Canadian Identity: Towards Diversity and Inclusion; Tavares, V., Jorge, M.J.M., Eds.; University of Manitoba Press: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2024; pp. 364–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augé, M. Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity; Verso: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. La Production De L’espace; Éditions Anthropos: Paris, France, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Vadeboncoeur, J.D. “(De)constructing NASCAR space”: A Black placemaking analysis of fan agency, mobility and resistance. Societies 2023, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.H.; Bilge, S. Intersectionality; Polity: Malden, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Giardello, M.; Cuervo, H.I.; Capobianco, R. How young Italians negotiate and redefine their identity in the mobility experience. Societies 2024, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhabha, H.K. Nation and Narration; Routledge: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, H.; Ferreira, J. Transformations in local social action in Portugal. Societies 2023, 13, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| City | Vancouver (n = 24) | Winnipeg (n = 25) | Moncton (n = 13) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage |

| Gender | ||||||

| Man | 10 | 42% | 13 | 52% | 6 | 46% |

| Woman | 14 | 58% | 11 | 44% | 7 | 54% |

| Unspecified | 0 | 0% | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% |

| Age range | ||||||

| 18–24 | 1 | 4% | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% |

| 25–34 | 6 | 25% | 1 | 4% | 10 | 77% |

| 35–44 | 7 | 29% | 4 | 16% | 2 | 15% |

| 45–54 | 4 | 17% | 10 | 40% | 1 | 8% |

| 55+ | 6 | 25% | 9 | 36% | 0 | 0% |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Never married | 7 | 29% | 2 | 8% | 5 | 38% |

| Married | 8 | 33% | 17 | 68% | 3 | 23% |

| Common law | 3 | 13% | 1 | 4% | 2 | 15% |

| Separated | 1 | 4% | 2 | 8% | 1 | 8% |

| Divorced | 2 | 8% | 1 | 4% | 2 | 15% |

| Widowed | 1 | 4% | 2 | 8% | 0 | 0% |

| Other | 2 | 8% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Children | 0% | |||||

| Yes | 11 | 46% | 22 | 88% | 3 | 23% |

| No | 13 | 54% | 3 | 12% | 10 | 77% |

| Level of education | ||||||

| Less than secondary diploma | 0 | 0% | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% |

| Secondary diploma | 1 | 4% | 1 | 4% | 1 | 8% |

| Technical diploma | 0 | 0% | 2 | 8% | 0 | 0% |

| College | 4 | 17% | 1 | 4% | 3 | 23% |

| University (Bachelor) | 5 | 21% | 8 | 32% | 6 | 46% |

| University (Post-graduate) | 14 | 58% | 12 | 48% | 3 | 23% |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Unemployed | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 8% |

| Part time | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 23% |

| Full time | 20 | 83% | 25 | 100% | 7 | 54% |

| Independent worker/Entrepreneur | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 8% |

| Retired | 2 | 8% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Student | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 8% |

| Country/region of birth | ||||||

| Abroad | 12 | 50% | 13 | 52% | 11 | 85% |

| South Africa | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 8% |

| Belgium | 0 | 0% | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% |

| Brazil | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 8% |

| Burkina Faso | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 8% |

| Burundi | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Cameroon | 0 | 0% | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% |

| China | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 8% |

| Republic of the Congo | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 8% |

| Ivory Coast | 0 | 0% | 1 | 4% | 1 | 8% |

| El Salvador | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 8% |

| France | 4 | 17% | 4 | 16% | 0 | 0% |

| French Guiana | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Haiti | 0 | 0% | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% |

| Mali | 0 | 0% | 1 | 4% | 2 | 15% |

| Morocco | 0 | 0% | 1 | 4% | 1 | 8% |

| Martinique | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Niger | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 8% |

| Poland | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Rwanda | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Senegal | 0 | 0% | 2 | 8% | 0 | 0% |

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Togo | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Tunisia | 1 | 4% | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% |

| Unspecified | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| In Canada | 12 | 50% | 12 | 48% | 2 | 15% |

| British Columbia | 2 | 8% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Manitoba | 1 | 4% | 5 | 20% | 0 | 0% |

| New-Brunswick | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 15% |

| Ontario | 0 | 0% | 4 | 16% | 0 | 0% |

| Quebec | 8 | 33% | 2 | 8% | 0 | 0% |

| Unspecified | 0 | 0% | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% |

| Status upon arrival (for immigrants) | ||||||

| Refugee | 4 | 17% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Work permit | 4 | 17% | 1 | 4% | 1 | 8% |

| Travel-work permit | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Family reunification | 1 | 4% | 2 | 8% | 0 | 0% |

| Study permit | 1 | 4% | 2 | 8% | 10 | 91% |

| Provincial nominee | 0 | 0% | 3 | 12% | 0 | 0% |

| Qualified worker | 0 | 0% | 5 | 20% | 0 | 0% |

| Express entry | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Unspecified | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Time in city of data collection | ||||||

| Between 0 and 5 years | 12 | 50% | 2 | 8% | 0 | 0% |

| Between 6 and 10 years | 3 | 13% | 3 | 12% | 9 | 69% |

| More than ten years | 9 | 38% | 20 | 80% | 4 | 31% |

| Vancouver CMA | Winnipeg CMA | Moncton CMA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 2,642,825 | 834,678 | 157,717 |

| Knowledge of official languages (French only and English and French combined) | 172,060 (6.5%) | 83,730 (10%) | 76,020 (48.2%) |

| Immigrant population | 1,089,185 (41.2%) | 207,950 (25.9%) | 13,345 (8.5%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huot, S.; Delaisse, A.-C.; Piquemal, N.; Sall, L. Mapping (In)Formal Francophone Spaces: Exploring Community Cohesion Through a Mobilities Lens. Societies 2025, 15, 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080231

Huot S, Delaisse A-C, Piquemal N, Sall L. Mapping (In)Formal Francophone Spaces: Exploring Community Cohesion Through a Mobilities Lens. Societies. 2025; 15(8):231. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080231

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuot, Suzanne, Anne-Cécile Delaisse, Nathalie Piquemal, and Leyla Sall. 2025. "Mapping (In)Formal Francophone Spaces: Exploring Community Cohesion Through a Mobilities Lens" Societies 15, no. 8: 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080231

APA StyleHuot, S., Delaisse, A.-C., Piquemal, N., & Sall, L. (2025). Mapping (In)Formal Francophone Spaces: Exploring Community Cohesion Through a Mobilities Lens. Societies, 15(8), 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080231