1. Introduction

Climate change has created one of the major crises of our times and undoubtedly one of the greatest threats facing the planet. The rise in temperature and the need to adapt to new climate conditions have been highlighted by the scientific community and environmental policymakers [

1]. Climate-induced hazards such as floods, forest fires, and droughts affect human communities, nonhuman species, and ecosystems all around the world.

New terms and emotions that affect people’s health and well-being, such as ecological emotions, eco-anxiety, climate-anxiety, and solastalgia, have been revealed and are studied in an interdisciplinary field worldwide. Children and young people are social groups that are particularly vulnerable to negative ecological emotions and pessimistic ideas about the future of their planet and their own lives.

On the other hand, the Mediterranean region is particularly vulnerable to the climate crisis. Over the last years, our study country, Greece, has been hit by significant and catastrophic climate-related natural events such as megafires, floods, and droughts [

2,

3,

4,

5].

The impact of the climate crisis on young people’s lives has not yet been studied thoroughly in Greece. In the framework of our research, young people from a vulnerable region to the climate crisis are facilitated to express their emotions and ideas about the consequences of climate change. At the same time, the participants in our research are future teachers who will affect the development of young children’s environmental consciousness. We attempt to listen to what these young people need and visualize the orientation of the environmental education content.

2. A Literature Review

2.1. The Vulnerability of Generation Z to Climate Change

Children and young people are included in social groups that are particularly vulnerable to the consequences of climate change. These consequences affect many dimensions of their lives, such as their health, academic development, and well-being, as well as other serious issues such as their survival in affected countries, mental health, and life choices [

6,

7,

8]. Children and young people of Generation Z (born between 1997 and 2012), also known as the climate generation, have been born and lived their whole lives in a world with circumstances of global warming and climate change. According to Ray [

9], Generation Z is particularly sensitive to environmental crises and environmental problems and has already developed and empowered environmental consciousness.

Children and young people worry, suffer, and act against the ecological crisis and especially climate change [

10]. It is no coincidence that Generation Z is represented by young environmental activists who not only worry about the ecological crisis and climate change but also take responsibility for environmental action and teach us what it is like to “do it yourself” [

11]. A typical case is the environmental activist Greta Thunberg [

12], but also young people who participate in well-known ecological movements such as FFF, as well as in less-known environmental actions worldwide [

13,

14].

2.2. The Emergence of Ecological Emotions

The experience of negative emotions by children and young people has begun to be studied by researchers and highlighted by the media worldwide. New terms that define these emotions have been introduced. Among them, eco-anxiety and solastalgia are at the top of the list. Eco-anxiety can be described as the distress that people experience from the consequences of the ecological crisis. It appears non-clinical and has been approached with great interest by different scientific fields during the last few years. It includes various negative (and a few positive) ecological emotions such as worry, fear, dread, anger, guilt, grief, hopelessness, and despair [

15,

16]. Climate anxiety includes a variety of ecological emotions and is used to determine anxiety related to the climate crisis [

17]. Solastalgia is a relevant emotion, a term created by Albrecht [

18] to express mourning for the transformation or destruction of the physical world. Solastalgia expresses the pain experienced by losing a home environment due to environmental degradation [

19].

In this study, we focus especially on climate anxiety, which can be approached as the manifestation of eco-anxiety, which is related to distress from the climate crisis [

17]. However, there is a long list of emotions that people experience because of climate change. Recently, Pihkala [

17] developed a taxonomy of various and different climate emotions that is further represented in the Climate Emotions Wheel [

20] where they are grouped into four categories: fear (overwhelm, panic, powerlessness, anxiety, worry), sadness (despair, loneliness, loss, depression, shame, guilt), anger (disappointment, betrayal, frustration, outrage, indignation), and positivity (interest, empowerment, inspiration, empathy, gratitude, hope).

Although there is not much data on the ecological emotions of young people, the studies that evaluate and approximate them come mainly from the Global North, and indeed, mainly from countries that are economically and technologically more developed and shielded against the effects of the climate crisis. We do not have quantitative and qualitative data on the ecological emotions of young people in the Global South [

21] but also in countries of the Global North that are more exposed to climate-induced hazards and do not have sufficient economic and technical tools to deal with the consequences of climate change [

22], including the European countries of the Mediterranean region. Countries of the Global South, due to complex economic, political, and social barriers, are particularly vulnerable to the climate crisis, and their residents experience climate distress at particularly higher levels [

23]. Although there is insufficient data from the Global South compared to the Global North on climate anxiety [

10], the first studies that are emerging document inequality in the experience of climate distress [

24].

In the largest international survey on climate anxiety by Hickman et al. [

25], it was astonishing that the great majority of young people belonging to Generation Z (aged 16–25 years) who participated expressed climate anxiety, including emotions of sadness, anxiety, anger, powerlessness, helplessness, and guilt due to the climate crisis. Although there is great interest in exploring ecological emotions and their connection to physical and mental health, as well as the well-being of children and young people, there is not enough research data yet that captures the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of Generation Z climate anxiety.

2.3. The Importance of Listening to Young People’s Eco-Anxiety

Hickman ([

26], p. 422) underlined the importance of listening to young people’s eco-anxiety and suggests that “some intergenerational relational healing can be found by transforming eco-anxiety into eco-awareness, eco-community, eco-agency, eco-aliveness, eco-empathy, eco-compassion, eco-care, and eco-awakening as humanity continues to learn how to live with and on a suffering planet.” In their study, Jones and Lucas [

27]—documented the significance of expressing, communicating, and sharing climate emotions among young people (15–19 years old) in Australia and the potential of creating safe intergenerational zones of listening to these feelings for young people’s support, but also environmental action and change.

There is also slight evidence that eco-anxiety includes, among other components, an existential depth [

10]. This element is very important since it underlines the potential of ecological emotions to contribute to the development of environmental consciousness and engagement in environmental action. Ojala [

28] has suggested the usefulness of negative ecological emotions in activating the willingness and ability to energetically participate in and act toward environmental values.

We are in front of an emotional ecological youth movement that may also affect the dynamics and qualities in the formation of environmental consciousness. Hickman [

26] suggests that youth’s eco-anxiety should be approached as a response to the ecological crisis. Children and young people should be supported through strengthening their emotional resilience and empowering their environmental actions. We suggest that the larger and deeper this reservoir of ecological emotions becomes, and the more intensely they are experienced by Generation Z due to the rapid increase in the effects of climate change, the more likely the possibilities for the transformation into deep environmental consciousness. A kind of consciousness that has to do with environmental values but also with an existential redefinition of the human–nature relationship and connectedness.

2.4. Linking Ecological Emotions with Environmental Education

According to Pihkala [

17] difficult ecological emotions may be experienced and transferred between environmental education teachers and students. It is important not to deny or avoid ecological distress or pathologize anxiety that derives from climate change. Both students and educators need to be aware of these emotions, but also to have a place to express them and cope with them within the framework of environmental education/education for sustainability.

The approach to emotions will be one of the future areas that need to emerge in climate education research and praxis [

29,

30]. Pihkala [

17] has given a comprehensive overview of the research on ecological emotions in the field of environmental education/education for sustainability and has highlighted the gap that exists and the need for future research in the field, including the negative emotions in environmental education/education for sustainability theory and practice.

The current research aims to contribute to the emergence of data on the ecological emotions and thoughts of young people about the future under the global threat of the climate crisis. Τhe research data are selected from a region that is vulnerable to extreme climate-induced natural hazards and which has not yet been studied in the context of the subject under investigation. Furthermore, this study attempts to formulate proposals for the orientation of the environmental education content. Updating pedagogical research in line with the demands of climate change should also consider the voice and needs of young people. This research explores the perceptions of future environmental education teachers regarding the teaching and learning methodology of environmental education/education for sustainability.

3. Methodology

The main purpose of this research was to assess young people’s ecological emotions and perceptions regarding climate change, as well as their ideas for the content of environmental education. Data were collected from young people, students at a University Pedagogical Department in Volos, Greece. The participants belong to Generation Z (born between 1997 and 2012) and live in a Mediterranean country that is vulnerable to climate incidents. For example, the city of Volos was recently exposed to an extreme flood event. In September 2023, Cyclone Daniel struck the region of Thessaly, including the city of Volos. The cyclone was formed in the Mediterranean basin and followed the unusually high sea surface temperatures over the last months. The cyclone affected Greece and Libya and became the severest storm in Mediterranean history [

31], leaving behind human deaths, changes in regional ecosystems, and damages of billions of dollars.

The current study analyses data that were collected from an online questionnaire from November 2023 to January 2024. The research participants were selected by convenience sampling. Ninety-three (93) mainly female students at a University Pedagogical Department, aged 18–26 years old (1st–4th academic years), completed an online questionnaire. The questionnaire was based on the assessment of climate anxiety as approached by the measurement scales of Clayton & Karazsia [

32] and [

26]. It also included an assessment of young people’s ideas about their needs and desires regarding the shaping of the content of environmental education. Responses were recorded using a combination of a three-item response scale (yes/no/prefer not to answer) and a Likert-type scale from 1 to 5 (with 1 = not at all and 5 = very much).

This study is exploratory and purely descriptive in nature, aiming to shed light on participants’ emotions and thoughts regarding their experience of the climate crisis. We analyze the participants’ responses across the following four dimensions:

- (a)

The type of emotions they experience because of climate change. Participants were asked to identify and rate the intensity of emotions such as sadness, anger, anxiety, and others (

Appendix A, Questions 1 and 2);

- (b)

Their emotional reaction to the changes in their immediate environment and important and valuable places due to climate change. Solastalgia was approached as a multidimensional emotion related to the participants’ immediate environmental degradation, causing a sense of loss, disruption of place attachment, and distress. Solastalgia was investigated through questions that included direct or indirect exposure to climate-related disasters as well as emotional perception of environmental change regarding important and valuable places to participants (

Appendix A, Questions 4–7);

- (c)

The thoughts they have because of climate change. Participants were prompted to share their thoughts about the future, both their own and that of the planet, considering climate change (

Appendix A, Questions 3, 8);

- (d)

The fields they would like environmental education to include (e.g., behavior change, action, contact with nature, scientific knowledge, etc.). Participants were asked to identify key areas they consider environmental education should cover (

Appendix A, Questions 9 and 10).

This research paid particular attention to ethical issues to ensure the anonymity and safety of the participants. The purpose and content of this research were explained in detail to the participants and their right to withdraw at any time. The students voluntarily participated in this research. The research proposal was approved by the Pedagogical Department’s Ethics Committee in 2023 (10516/26-10-2023). Participation was voluntary and not linked to any course evaluations. The issue of climate change was not part of the environmental education curriculum, ensuring no pressure related to course assessment. The anonymity of participants was maintained throughout the research process, with no personal data collected beyond age. A specific field was included for participants to confirm their understanding of the research purpose and consent to participate. All data was securely stored on researchers’ computers in password-protected folders.

4. Results

This study included responses from 93 participants, with the majority (72%) aged between 18 and 20 years, and the remaining 28% aged between 21 and 26 years. A notable portion (62.4%) reported being directly affected by climate change, while 32.3% stated they had not experienced direct impacts. Among those affected, 31.7% experienced a natural disaster related to climate change, such as floods in Thessaly (64.5%), wildfires in regions like Rhodes, Evros, and Attica (25.8%), and droughts (33.3%). Additionally, 77.4% indicated that they knew someone who had been directly impacted by climate change, highlighting the widespread impact of these events within participants’ communities.

4.1. Climate Anxiety

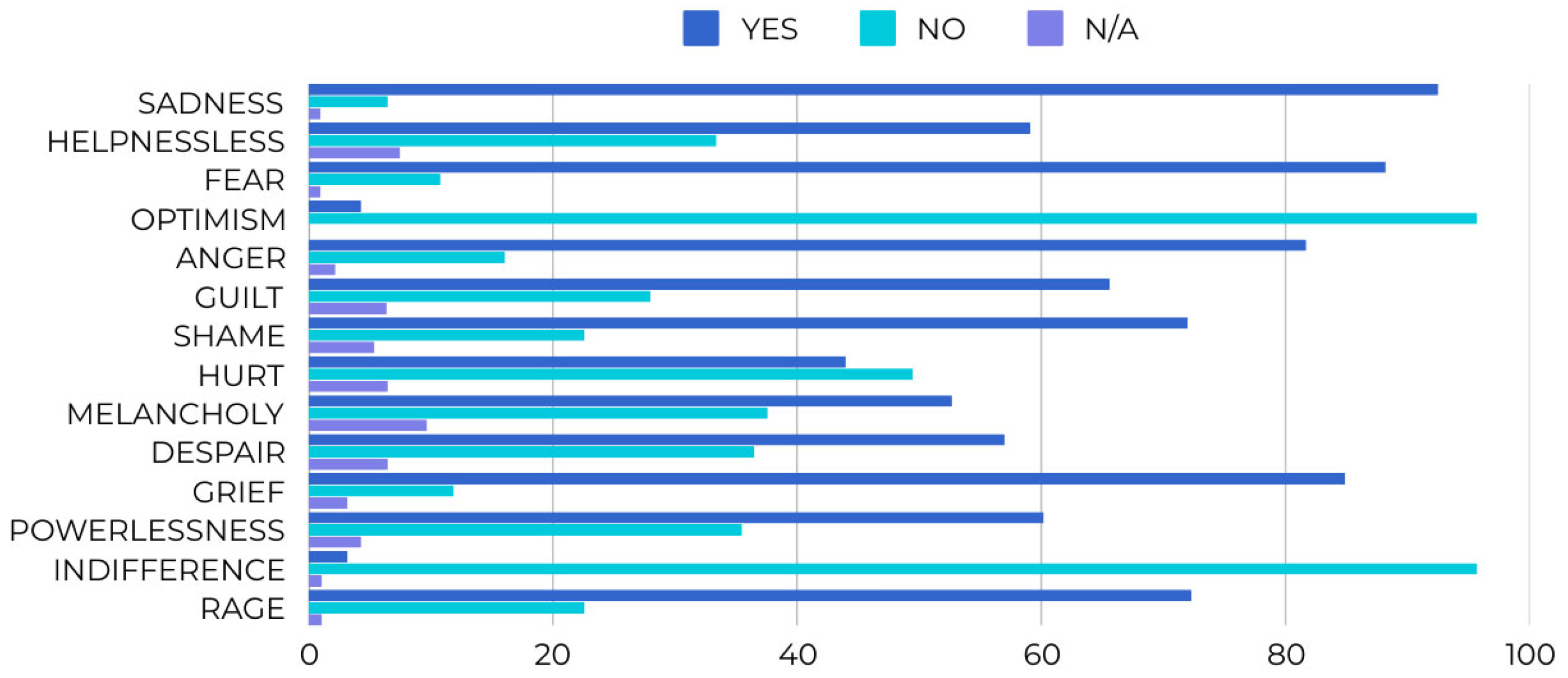

The survey revealed a high level of climate anxiety among participants, with sadness (92.5%), fear (88.2%), anger (81.7%), and helplessness (59.1%) being the most frequently reported ecological emotions. In contrast, optimism (4.3%) and indifference (3.2%) were the least reported emotions. Among the participants, grief (84.9%) and rage (76.3%) were common emotional responses (

Figure 1 and

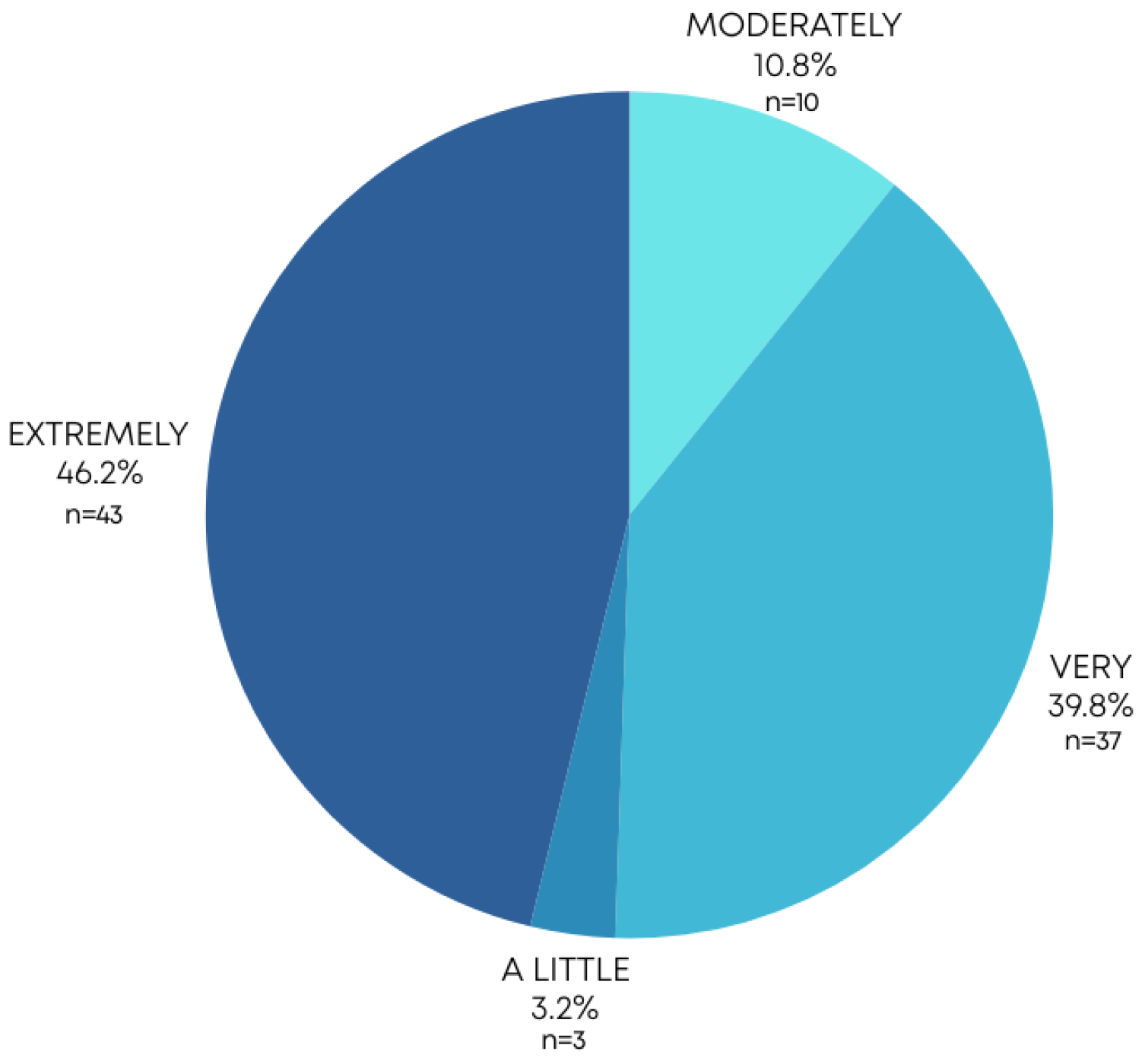

Table 1). Participants expressed high emotional distress linked to climate change (M = 4.30; SD = 0.76). The majority (86%) reported experiencing emotions of climate change “extremely” (46.2%) or “very” (39.8%), with a smaller proportion feeling “moderately” (10.8%) or “a little” (3.2%) (

Figure 2).

The participants’ negative emotions about the climate crisis are classified into the four main categories of the Climate Emotions Wheel [

20]: (a) 44–92.5% of the participants reported feeling various emotions under the major category of sadness (sadness, shame, guilt, hurt, melancholy, despair, grief); (b) 59.1–88.2% of the participants reported feeling various emotions under the major category of fear (fear, helplessness, powerlessness), and (c) 76.3–81.7% of the participants reported feeling various emotions under the major category of anger (anger, rage). Optimistic emotions were reported only by 4.3% of the respondents.

To understand further ecological emotions, we compared them with the experience of natural disasters such as floods, wildfires, and droughts. The results revealed that the young participants who had experienced such events tended to report higher levels of emotions under the categories of sadness, fear, and anger. For instance, among those who had experienced wildfires, 96.4% reported feeling sad, and 89.3% reported feeling fear compared to 91% (sad) and 86% (fear) of those who had not experienced a wildfire. Rage was slightly higher among participants who had recently experienced a wildfire (83.3%) compared to participants exposed to wildfires in the past five years (82%). These observations strongly support the assumption that participants’ exposure to extreme climate-induced natural disasters heightened the intention of negative emotional reactions.

4.2. Solastalgia

The data provides a broad view of the impacts of climate change among participants. A significant portion of the participants (62.4%) reported that they have been directly affected by climate change in some capacity, which may involve changes to their home, family, work, or daily life. Additionally, most respondents (77.4%) knew someone who had experienced direct impacts from climate change, indicating a broad social network affected by environmental change.

Regarding perceived changes in familiar and cherished places due to climate change, 78.5% of respondents have observed such alterations. The emotional response to these changes varies, although in general, participants expressed significant distress (M = 4.41, SD = 0.72). Of those who noted changes, 52% are “very upset”, and 34.7% are upset “a lot”, revealing the experience of solastalgia by young people regarding favorite and valuable places. In contrast, only 1.3% are not “much” affected, and 9.3% report being “moderately” upset (

Figure 3).

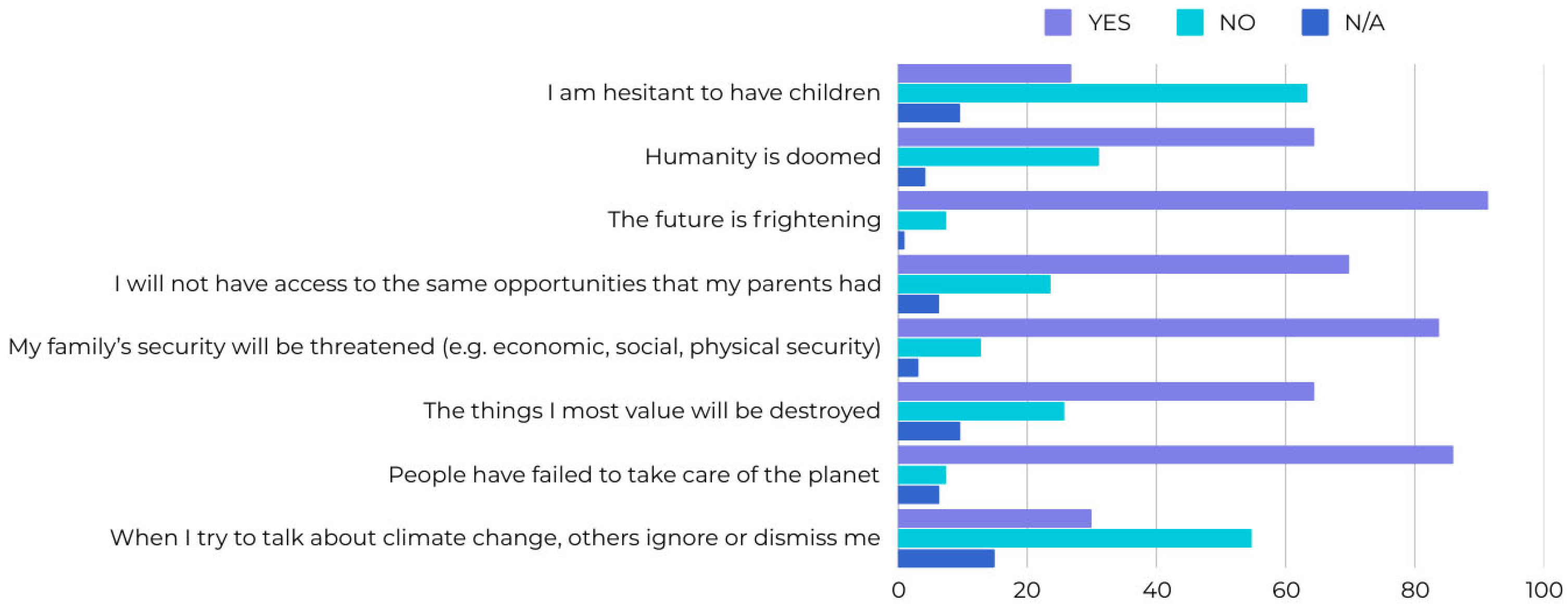

4.3. Thoughts and Concerns About the Future

The majority of participants expressed a profound concern about the future, with 91.4% of the respondents indicating that they find the future “frightening”, and 69.9% a sense that their access to opportunities would be compromised compared to previous generations. Additionally, 83.9% of the respondents worried about threats to their family’s security, including economic, social, and physical aspects. The perception of a broader failure to address climate change was also prevalent, with 86% agreeing that humanity has not adequately taken care of the planet. This concern extends to pessimistic thoughts, since data suggest that 64.5% of the participants reported that the things they most value are at risk of destruction. The data also reflects a notable sense of disappointment, since 64.5% of respondents agreed with the sentence that “humanity is doomed” (

Figure 4).

4.4. Suggestions from Young People for the Orientation of Environmental Education Content

The findings reveal participants’ agreement on the importance of environmental education in addressing the climate crisis (M = 4.38, SD = 0.85). According to the data analysis, a significant part of the participants (53.8%) highlighted that environmental education is “very much” crucial for solving the climate crisis, while 34.4% consider it “a lot” important (

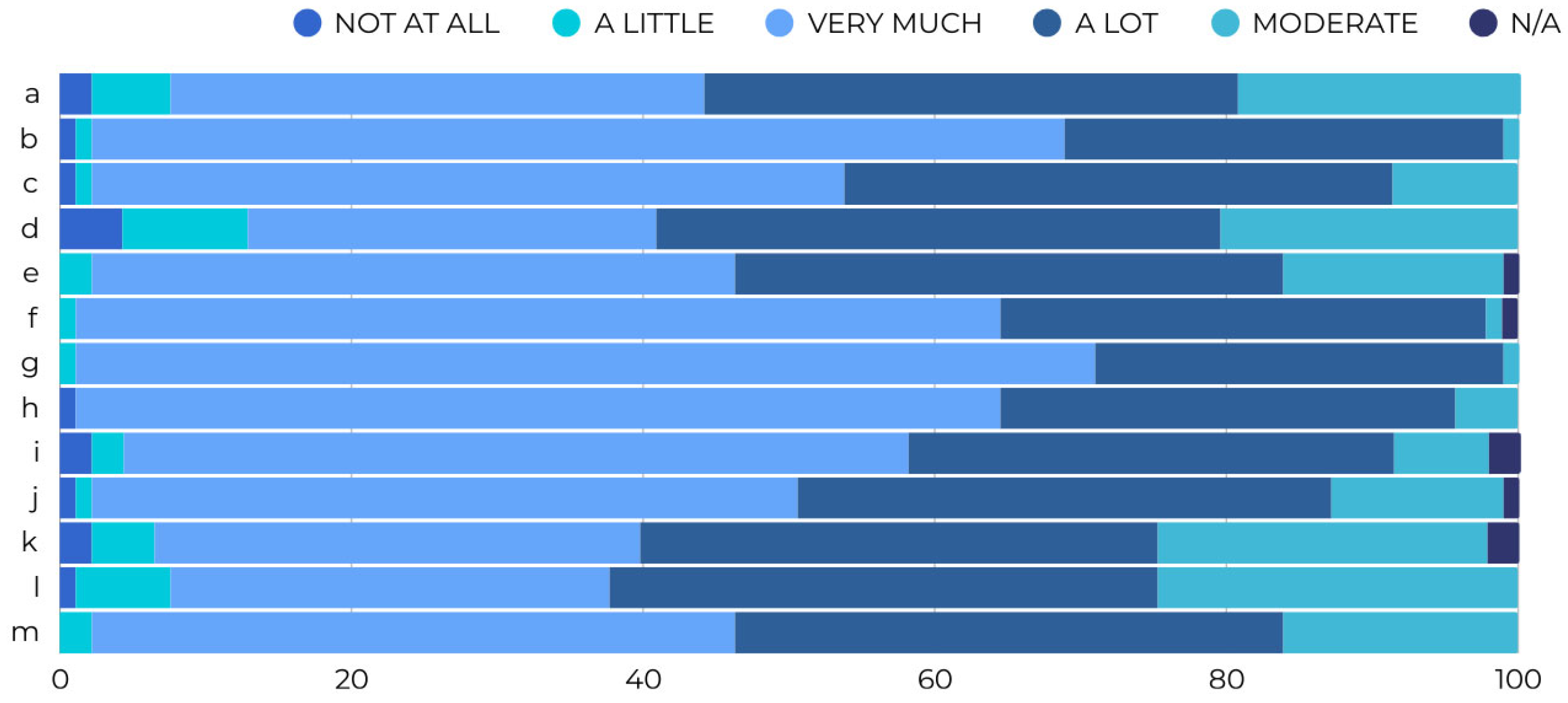

Figure 5). This strong statement indicates a widespread recognition of the role that education plays in fostering awareness and action on climate change.

Cronbach’s alpha for the 13 items measuring agreement with specific pedagogical axes of environmental education was satisfactory (α = 0.90). The investigation of different pedagogical approaches to environmental education content revealed a range of perspectives among the participants (See

Table 2 for means and standard deviations and

Figure 6 for percentages of responses). Although more traditional dimensions, such as the acquisition of scientific knowledge (with a percentage of 36.6% highlighted it as “very much” crucial) and the strengthening of pro-environmental behavior (a percentage of 66.7% highlighted it as “very much” crucial) are supported by many respondents, new approaches also gather significant percentages. On the contrary, the dimensions that would be expected to be closer to Generation Z do not particularly attract the interest of young people. For example, using technological tools and social media does not seem to excite young people as much as we might expect. Furthermore, the perspective of learning ways to be more resilient to the effects of climate change, which is promoted by environmental policy and education for sustainability, does not particularly concern young people.

Contact with nature gathers a significant percentage of young people’s preferences as content in environmental education, with the vast majority of responders rating it as “very much” (n = 59/63.4%) or “a lot” (n = 31/33.3%) important. After all, in recent years, this field has been closely examined by scholars within the field. Furthermore, young people prefer their ideas and needs for the immediate environment they live in to be heard and considered. In other words, they reveal a need for strengthening young people’s participation in decision-making at the local level. There is also a significant need for providing space to express their emotions about climate change, a dimension that is underestimated in the environmental education/education for sustainability field. This is strongly supported by the data, as 63.4% of participants (n = 59) rated this need as “very much” important and 31.2% (n = 29) as “a lot” important.

Young participants—future environmental education teachers—prefer to be involved in environmental actions. A significant percentage about environmental activism was recorded (n = 65/69.9%), which is higher than other preferences such as the use of technology that participants expressed as “very much” (33.3%) or “a lot” important (35.5%), or the need for resilience solutions that highlighted as “a lot” important by a percentage of 38.7%.

Data analysis revealed an orientation toward participatory and action-oriented forms of engagement. For example, in sub-question if it is important (e) “to have the space to protest and resist decisions made on the issue of climate change” (

Table 2), 44.1% (

n = 41) of participants answered “very much” and 37.6% (

n = 35) answered “a lot”, highlighting that many participants think that it is important to declare and take action for environmental change.

As previously mentioned, the highest level of agreement was recorded for the sub-question about the importance (g) “To be encouraged to participate in environmental actions (e.g., tree planting, awareness actions, etc.)”, with 69.9% (n = 65) of participants selecting “very much” and an additional 28.0% (n = 26) selecting “a lot”.

Finally, there are choices that emerge the need for deeper existential, social, and political changes that should be included in environmental education theory and praxis. For example, there is a significant percentage of preferences for reconsidering the development model of overconsumption (n = 45/48.4%), but also the human dominance over nature and the exceptional role of human beings within the more-than-human world (n = 50/53.8%). Young participants emphasize ideas that were traditionally more marginal in the field of environmental education, such as ecocentrism or degrowth.

5. Discussion

5.1. Assessing the Young Participants’ Emotional Responses to the Climate Crisis

This study contributes to the interdisciplinary scientific dialogue on the climate crisis, offering insights into the emotions and perceptions of a small-scale sample of young people in a Mediterranean region who are vulnerable to climate-induced hazards. The participants, having recently experienced catastrophic climate-induced natural disasters such as cyclones, floods, megafires, and droughts, expressed particularly negative emotions and perceptions for their own future and the future of the planet.

The high prevalence of negative emotions such as sadness, fear, and anger underscores the psychological distress that the ecological crisis imposes on younger generations. Negative emotions range at higher levels than the average emotions of young people recorded in the global survey by Hickman et al. [

25]. For example, 92.5% of the participants reported feeling sadness, 88.2% fear, and 81.7% anger, combined with the average rates of 66.7% (sadness), 67.3% (fear), and 56.8% (anger) of the global survey. The negative emotions of young people who participated in this study converge more with the emotions of young people in the Global South and are a little bit higher than in other Mediterranean countries that have better economic and technological support, ensuring resilience to climate-induced natural hazards.

To the list of ecological emotions assessed in our research, we added two emotions that include a more social and political dimension and reaction: helplessness and rage. These two emotions, experienced by most of the participants (helplessness: 59.1% and rage: 76.3%), reveal that disapproval is not only an individual reaction but appears as a reflection of broader systemic failures to address the climate crisis effectively. Helplessness is linked to the lack of systemic support for the effects of climate change that young people are now directly experiencing. Rage indicates strong disapproval and despair in the face of the political system and may indicate a tendency for future environmental protests and environmental activism. In countries of the Global North, this concern has been expressed through the development of environmental activism and the assumption of responsibility for action by young people [

11,

14].

5.2. Confronting Solastalgia with Action-Oriented Place-Based Pedagogy

The research findings suggest that the young participants experience solastalgia regarding the catastrophic changes in their favorite places in their immediate environment. Climate change has a tangible and distressing emotional impact on youth’s personal lives and their broader social circles. The substantial emotional response to traumatic environmental changes underscores the seriousness with which these changes are perceived [

33], reflecting deep concerns about the ongoing and future consequences of climate change.

The importance of including emotional dimensions in educational strategies and practices [

34] is highlighted by most of the participants. Understanding and addressing young people’s emotions in educational settings is critical to fostering environmental change and reimagining the orientation of the environmental education context. In our research, we examine the kind of ideas that future environmental education teachers belonging to Generation Z have about the content of environmental education. What is their own vision for the future of environmental education? As eco-philosopher Morton [

35] has very aptly argued, emotions are to be transformed and conceptualized into the ideas of the future. In this case, young people’s ecological emotions are of great importance as they will become future environmental education teachers who will undertake the formation of young children’s environmental consciousness.

This research highlights the potential of environmental education in addressing both the cognitive and emotional dimensions of climate change. Participants’ strong endorsement of participatory and action-oriented approaches reveals the need for experiential and critical learning opportunities that connect pedagogical theory with praxis [

36]. Furthermore, the demand for safe spaces to express and discuss emotions related to climate change emphasizes the importance of embracing the emotional world in the environmental education context and curricula [

37].

Furthermore, the experience of solastalgia among the research participants highlights the profound connection between individuals and their immediate environments. Witnessing the degradation of familiar and cherished places exacerbates emotions of loss and distress, reinforcing that there already exists the ground for developing a critical place-based educational approach [

38]. Environmental education programs that are based on local ecosystems and communities can help children and young people connect, participate, and act with their surroundings, fostering a sense of belonging, stewardship, and collective responsibility [

39].

5.3. The Existential Depth of Ecological Emotions and Its Impact on the Environmental Education Content

Finally, many participants visualize a deeper approach to environmental education, addressing two issues: the need to change the model of overconsumption in our societies, and the need to redefine our relationship with the nonhuman world. Regarding the first issue, the hypothesis of degrowth [

40] has not yet been introduced widely in environmental education/education for sustainability, and this trend deserves to be researched widely.

Regarding the second issue, the need for existential reconsideration of our relationship with nonhuman nature justifies approaches that have long been on the fringes of ecological thinking and traditional environmental education/education for sustainability. For example, the philosopher A. Naess [

41] argued since 1973 that it is time to ask deeper questions about the ecological crisis and not limit ourselves to a shallow approach to its consequences and its treatment. The need for a closer relationship with nature as content in environmental education is expressed by most of the participants. This issue is already covered by scholars in the field who have developed innovative methodological and philosophical approaches to reimagine environmental education and education for sustainability [

42].

6. Limitations of This Research and Future Research Directions

There are several limitations to the current study. First, the survey is based on a quantitative approach to participants’ experiences, emotions, and perceptions. Second, there is no data analysis in relation to demographic variables. Finally, the survey presents a small-scale inquiry into young people’s emotions and opinions in a specific region of the Mediterranean. The data analysis is based on a geographically and demographically bounded sample of participants.

The limitations of the current study could be transformed into opportunities for future research regarding methodology, sample extension, and comparisons in neighboring countries. For example, it would be interesting to compare the findings with a broader sample of young people of the same age from various regions of the Mediterranean, which are vulnerable to climate-induced catastrophic events. Furthermore, a qualitative research methodology with multiple data selection methods that are friendly to Generation Z communication choices might contribute to a better understanding of young people’s emotions and opinions regarding climate change. Finally, there is a need for a thorough inquiry into the cognitive model of a direct correlation between young people’s experiences of catastrophic climate-induced natural events and their opinions on the orientation of environmental education.

7. Conclusions

The findings of this research shed light on the profound impact of the climate crisis on young people in a Mediterranean region that is vulnerable to climate-induced natural hazards, revealing a significant level of climate anxiety. The particular intensity of negative ecological emotions among young research participants is partly linked to their recent experience of extreme natural disasters such as cyclones, floods, wildfires, and drought events. Climate anxiety is not only an emotional response to the climate crisis but also influences young participants’ daily lives, affecting future aspirations and personal choices.

This study highlights the need to address ecological emotions within educational frameworks. The young participants strongly emphasized the importance of environmental education in addressing the climate crisis, highlighting their need for the redefinition of the content of environmental education. The research findings underline the importance of integrating cognitive, emotional, experiential, participatory, political, and existential dimensions into environmental education theory and praxis, promoting a holistic response to climate change.

This study highlights that young participants belonging to Generation Z turn collectively to a deeper, existential need for environmental change and demand fundamental changes in the way we think, live, and dream of our societies. Young people in the specific Mediterranean region, through the experience of negative ecological emotions, reimagine environmental education in a new, holistic way. There are indications of new approaches to youth’s needs within environmental education that deserve to be further explored and discussed within the field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.T.; methodology, I.T. and F.B.; validation, I.T. and F.B.; formal analysis I.T., A.M.K. and F.B.; investigation, I.T. and A.M.K.; data curation I.T., A.M.K. and F.B.; writing—original draft preparation, I.T. and A.M.K.; writing—review and editing, I.T. and F.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Early Childhood Education (10516/26-10-2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Natural disasters: flood, Thessaly flood 2023, forest fire, summer 2023 wildfires (Rhodes, Evros), past 5-year wildfires (Evia, Samos), Attica wildfire, drought, other;

Response Type: three-item response scale (yes/no/prefer not to answer).

Emotions: sadness, helplessness, fear, optimism, anger, guilt, shame, hurt, melancholy, despair, grief, powerlessness, indifference, rage;

Response type: three-item response scale (yes/no/prefer not to answer).

Statements: I am hesitant to have children; Humanity is doomed; The future is frightening; I will not have access to the same opportunities that my parents had; My family’s security will be threatened (e.g., economic, social, physical security); The things I most value will be destroyed; People have failed to take care of the planet; When I try to talk about climate change, others ignore or dismiss me;

Response type: three-item response scale (yes/no/prefer not to answer).

Question 4. Have you personally been directly affected by climate change (e.g., your home, your family, your family’s work, your daily life)?

Statements: Learn more scientific information about climate change; To be encouraged to have more environmentally friendly behaviors (e.g., recycling, turning off the light switch, etc.); To have a space to express their feelings about climate change; To learn ways to be more resilient to the effects of climate change; To have the space to protest and resist decisions made on the issue of climate change; To have opportunities for greater contact with nature; To be encouraged to participate in environmental actions (e.g., tree planting, awareness actions, etc.); To have space for their ideas and needs to be heard and taken into account for the environment they live in; To be encouraged to adopt of a more equal position in relation to the natural world; There should be space to utilize technological tools; There should be space to use social media; To have space for the use of the arts (art, music, the literature, etc.);

Response Type: Likert Scale (with 1 = not at all and 5 = very much).

References

- United Nations Environment Programme. Annual Report 2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/annual-report-2023 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Fang, B.; Bevacqua, E.; Rakovec, O.; Zscheischler, J. An increase in the spatial extent of European floods over the last 70 years. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 3755–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtis, I.M.; Vangelis, H.; Tigkas, D.; Mamara, A.; Nalbantis, I.; Tsakiris, G.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. Drought assessment in Greece using SPI and ERA5 climate reanalysis data. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidis, S.P.; Proutsos, N.D.; Solomou, A.D.; Michopoulos, P.; Bourletsikas, A.; Tigkas, D.; Spalevic, V.; Kader, S. Spatiotemporal monitoring of post-fire soil erosion rates using earth observation (EO) data and cloud computing. Nat. Hazards 2024, 121, 2873–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigkas, D.; Proutsos, N.D.; Sofou, G.; Papalexis, D.; Kitsos, A.; Vangelis, H.; Tsakiris, G.; Papadiamantopoulou, E.; Stournaras, K. Extreme hydrometeorological events and the role of reclamation works and irrigation-drainage systems in the era of climate crisis. In Proceedings of the 12th World Congress of EWRA: Managing Water-Energy-Land-Food Under Climatic, Environmental and Social Instability, Thessaloniki, Greece, 27 June–1 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S.D.; Manning, C.M.; Krygsman, K.; Speiser, M. Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Implications, and Guidance; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S.D.; Pihkala, P.; Wray, B.; Marks, E. Psychological and Emotional Responses to Climate Change among Young People Worldwide: Differences Associated with Gender, Age, and Country. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.D. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.J. A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety: How to Keep Your Cool on a Warming Planet; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tsevreni, I.; Proutsos, N.; Tsevreni, M.; Tigkas, D. Generation Z Worries, Suffers and Acts against Climate Crisis—The Potential of Sensing Children’s and Young People’s Eco-Anxiety: A Critical Analysis Based on an Integrative Review. Climate 2023, 11, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, S. Young environmental activists and Do-It-Ourselves (DIO) politics: Collective engagement, generational agency, efficacy, belonging and hope. J. Youth Stud. 2022, 25, 730–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunberg, G. The Climate Book: The Facts and the Solutions; Penguin Publishing Group: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mayes, E. Young People Learning Climate Justice: Education Beyond Schooling Through Youth-Led Climate Justice Activism. In Handbook of Children and Youth Studies; Wyn, J., Cahill, H., Cuervo, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, S. Young environmental activists are doing it themselves. Political Insight 2019, 10, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluda-Verdú, I.; Senent-Valero, M.; Casas-Escolano, M.; Matijasevich, A.; Pastor-Valero, M. Fear for the future: Eco-anxiety and health implications, a systematic review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-Anxiety Tragedy, and Hope: Psychological and Spiritual Dimensions of Climate Change. Zygon J. Relig. Sci. 2018, 53, 545–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-Anxiety and Environmental Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G. ‘Solastalgia’. A new concept in health and identity. PAN Philos. Act. Nat. 2005, 3, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, G.; Sartore, G.M.; Connor, L.; Higginbotham, N.; Freeman, S.; Kelly, B.; Stain, H.; Tonna, A.; Pollard, G. Solastalgia: The distress caused by environmental change. Australas. Psychiatr. 2007, 15, S95–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P.; Kamenetz, A. A Guide to Climate Emotions; Climate Mental Health Network: California, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aruta, J.J.B.R.; Simon, P.D. Addressing climate anxiety among young people in the Philippines. Lancet Planet Health 2022, 6, e81–e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruta, J.J.B.R. Mental health efforts should pay attention to children and young people in climate-vulnerable countries. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 321–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnwell, G.; Wood, N. Climate justice is central to addressing the climate emergency’s psychological consequences in the Global South: A narrative review. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2022, 52, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.-P.; Chan, H.-W.; Clayton, S. Climate change anxiety in China, India, Japan, and the United States. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 87, 101991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mello, C.; van Susteren, L. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. Lancet Planet Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C. We need to (find a way to) talk about…Eco-anxiety. J. Soc. Work. Pract. 2020, 34, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Lucas, C. ‘Listen to Me!’: Young People’s Experiences of Talking About Emotional Impacts of Climate Change. Glob. Environ. Change 2023, 83, 102744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Hope and Worry: Exploring Young People’s Values, Emotions, and Behaviour Regarding Global Environmental Problems. Ph.D. Dissertation, Orebro University, Orebro, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. Environmental education after sustainability: Hope in the midst of tragedy. Glob. Discourse 2017, 7, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A. Climate change education and research: Possibilities and potentials versus problems and perils? Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 767–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argüeso Dl Marcos, M.; Amores, A. Storm Daniel fueled by anomalously high sea surface temperatures in the Mediterranean. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.D.; Karazsia, B.T. Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarello, S. Solastalgia: Climatic Anxiety—An Emotional Geography to Find Our Way Out. J. Med. Philos. Forum Bioeth. Philos. Med. 2023, 48, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magklara, K.; Kapsimalli, E.; Liarakou, G.; Vlassopoulos, C.; Lazaratou, E. Climate crisis and youth mental health in Greece: An interdisciplinary approach. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. 2024, 33, 2431–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, T. Feelings Are Ideas from the Future. Gray Area Festival, San Francisco, USA. 30 September 2022. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-h50qnjycho (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Gruenewald, D.A. The best of both worlds: A critical pedagogy of place. Educ. Res. 2003, 32, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.; Oakley, J. Engaging the emotional dimensions of environmental education. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 21, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald, D.A. Foundations of place: A multidisciplinary framework for place-conscious education. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2003, 40, 619–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, D. Place-Based Education: Connecting Classrooms and Community; Orion Society Press: Great Barrington, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Latouche, S. Degrowth and the Paradoxes of Happiness. Ann. Fond. Luigi Einaudi 2020, 54, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naess, A. The shallow and the deep, long-range ecology movement. A summary. Inq. Interdiscip. J. Philos. 1973, 16, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, A.; Malone, K.; Barratt Hacking, E. (Eds.) Research Handbook on Childhoodnature: Assemblages of Childhood and Nature Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).