1. Introduction

Despite important differences among companies related to Artificial Intelligence (AI) implementations (differences due to industry affiliation, size of the company, or region), the specialists are unanimous in their conclusion: “AI will be in just about every product and service we buy and use” [

1] (p. 97). The fourth Industrial Revolution or Industry 4.0 has driven significant changes as innovations and fast-paced technologies require professionals who have the skills and knowledge to adapt the corporate strategies and stir organizations toward success [

2].

Employees are now expected to have acquired key competencies, predominantly technology-driven skills, especially in the field of Artificial Intelligence. Following Industry 4.0 imperatives, educational institutions aim at equipping graduates with unique human skills that provide both a competitive advantage in using new technologies and aligning the future of learning with the needs of businesses in the context of emerging technologies. As a consequence, the learning process requires even more pressingly a cooperation between universities and the business environment. Young graduates have to be equipped with the abilities, knowledge, and skills that are required in the reshaped labor market, enabling them to access emerging job opportunities driven by the creation and continuous development of Artificial Intelligence.

A significant factor of successful AI implementation in an organization is “the acquisition and development of learning about this technology” [

3] (p. 361). In order to gain a competitive advantage from the implementation of new technologies, a company needs employees who have the ability to use and apply AI in a proper and profitable manner.

The aim of this study is to present the perspective of businesses on what they consider to be of significant importance in the process of educating graduates to boost their AI familiarity. In this sense, the study also examines the future of business and Higher Education collaboration with the purpose of equipping future employees and enabling them to use and implement AI for commercial purposes.

Theoretically, the study creates a multi-dimensional model of AI preparedness that integrates ethical reasoning, lifelong learning, and industry–education collaboration. This integrative view goes beyond existing work that often focuses solely on either technical competence or theoretical attitudes toward AI, by presenting business expectations as a central axis for curriculum alignment and graduate readiness.

The present study is organized as follows: the first section provides an insight into the literature that examines the concept of AI familiarity and how AI familiarity enhances willingness to use and to be positive towards AI implementation. This study approaches Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a general-purpose tool, focusing on its application in business contexts by employees who are not technology specialists. From a business perspective, it is particularly important that employees develop a general familiarity with emerging technologies, as this can help reduce the anxiety often associated with increased digitalization and technological change. Subsequently, the study examines the analyses that have investigated business–HE cooperation in order to maximize the benefits the education process brings to businesses.

The second section is devoted to the methodological part. This study adopted a qualitative approach, based on in-depth interviews with 16 middle-management representatives from international corporations operating across diverse industries.

The data were analyzed using Gioia’s methodology, which facilitated a structured identification of first-order concepts, second-order themes, and aggregate dimensions. This analytical framework enabled a nuanced understanding of business expectations regarding the role of HE institutions in preparing graduates who are capable of meeting economic and commercial imperatives under the pressure of AI diffusion. Gioia methodology facilitated the identification of how business expectations resonate with the theoretical constructs presented in the first part of the article: Firms emphasized not only the need for basic AI knowledge (linked to the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)) but also the capacity for critical and ethical judgment (linked to Social Cognitive Theory). Thus, the research questions and emergent themes are directly anchored in—and extend—the theoretical background laid out in the early sections. The paper ends with conclusions, limitations of the study, and future research avenues.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Skills and AI Familiarity

Digital skills have become essential across all industries in the past decades. Nowadays companies aim to hire employees that have a wider set of competences: domain-specific knowledge, digital tools competences, and the ability to adapt quickly to new technological developments [

4] (p. 1). At the same time, in the academic world, students and teachers must also be dedicated to continuous learning and adaptation because of the rapid pace of technology advancements [

4] (p. 5). What is clear is that, from now on, digital proficiency is a vital element that gives significant benefits for both social involvement and career opportunities [

4] (p. 5).

The spread of Artificial Intelligence across different sectors has transformed the known operational methods of companies [

5] (p. 1). With this, numerous nuances take shape. One is that the autonomous functioning of AI systems creates unpredictable outcomes if users do not have the competence to control those systems. Similarly, algorithms behind those AI systems can often generate decisions which humans find difficult to comprehend [

6] (p. 5). In this regard, a level of familiarity with the topic of AI comes into question.

Ref. [

7] defines familiarity as one intuitive sense of recognition, but one different from recalling specific details about an event. People can experience familiarity as a personal feeling of confidence towards an activity. At the same time, this feeling can lead to biased preferences towards familiar things.

Ref. [

8] (p. 4) describes familiar users in their relation with AI systems as those who already understand AI systems and such technologies. These users show greater acceptance for autonomous applications. For example, people who are already used to delegating tasks to other humans (e.g., driving) tend to accept automation of these tasks, but, at the same time, tend to resist the automation of other activities that they do not perform as often. Their study conducted between 2018 and 2022 shows that increased familiarity with AI leads to higher acceptance of most AI applications, demonstrating that prior knowledge plays an important role in shaping attitudes [

8] (p. 4).

From another perspective, the Social Cognitive Theory framework analyzed all those individual patterns of users directly based on familiarity level, observation skills, and self-efficacy in relation to AI tools. The Social Cognitive Theory states that familiarity with AI tools can lead to an increase in self-efficacy, which thus produces better results [

9].

According to [

10] (p. 3), people base their purchasing decisions and social interactions on familiar experiences, which become stronger with each positive encounter, while [

11] (p. 4) mentioning that users develop familiarity with chatbots through their understanding of interaction methods and their knowledge of how to receive recommendations or help, which, in the end, affects their decision to use the tool. Familiarity builds cognitive trust because users develop trust in systems after having positive interactions with them [

12].

According to the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), familiarity is influenced by external factors (exposure to AI information, information credibility, and institutional support) as well as by internal factors (intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy) [

13]. The role of educational process is to shape in a critical way the role of external factors and, in this way, to be the ground for internal factors to flourish. A concrete example is offered by [

5] (p. 2), who explain that medical students today learn about AI through coursework, workshops, and conference demonstrations, which has made them familiar with language-model tools (including ChatGPT4) that they use for studying and clinical simulations. The acceptance of AI integration in future medical practice depends on student familiarity with AI technology, which leads them to believe AI will improve physician capabilities through personalized education and better diagnostic choices. The majority of students support adding AI training to medical curriculum because they want to benefit from these advantages [

14] (p. 14). A similar conclusion is drawn by [

9], who states that the level of AI familiarity refers to the extent of knowledge that educators and students have in using AI-related tools. The more frequently people use similar AI systems, the higher their cognitive engagement becomes, which leads to a deeper understanding of the technology. Generally, familiarity has a positive impact on the engagement level with AI, while also the engagement significantly affects the intention to use. The higher the engagement level, the higher the intention to use will be [

9].

2.2. Familiarity Considerations and Its Importance in Business

It becomes clear that AI adoptions create important competitive advantages for companies. Businesses that implement AI tools and do it at an early stage (the so-called front-runners) can benefit from significant economic improvements. In this context, the implementation of AI naturally shifts the employment needs from basic digital skills work to positions that require complex digital expertise, cognitive skills, and creative thinking. This trend is believed to continue to increase significantly by 2030. For this to become a reality, organizations are required to maintain strategic investments in AI and show patience. At the same time, a rapidly changing job market driven by AI demands active participation not only from the business side but also from educational institutions and individuals who must continuously train and adapt [

15].

Building on this narrative, according to [

16], 7 out of 10 firms are expected to embed AI in their core business processes by 2030. The pace of adoption seems to exceed expectations highlighted by [

16]. The McKinsey’s 2024 global survey shows that already 72% of companies deploy some form of AI and 65% use generative-AI tools in at least one business function. This was almost double the share recorded ten months earlier. The McKinsey study also reveals that this organizational surge is mirrored at individual level as well. Staff, especially senior leaders, are now much more likely than in 2023 to use AI assistants, both at work and in their personal lives, turning basic familiarity with AI interfaces into a default workplace expectation [

17]. As far as depth of familiarity is concerned, roughly 5% of respondents, the “high performers”, already attribute more than 10% of EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes) to generative AI [

18]. Surveys on American companies show annual growth of 73–78% in relation to AI, signaling that basic AI familiarity is spreading fast. The same study estimates that employee level use of AI is between 20 and 40%, with positions such as software development showing higher percentages. As adoption accelerates, in this context the real question is how intensively and skillfully businesses and employees use AI, not whether they use it at all [

19].

Businesses that integrate AI technology need to operate a fundamental change in their operational framework, considering new solutions for ethical concerns. The most significant ethical factors mentioned by the literature for responsible AI implementation include bias reduction from algorithms, maintaining openness in systems, accountability measures along with data protection, workforce management, and technology misuse prevention [

20] (pp. 4–5).

Recent past incidents demonstrate that suboptimal understanding of AI systems creates dangerous effects on all ethical issues mentioned above. A study conducted at the University of Washington, using 550 real CVs, demonstrated that the most advanced language models selected white male names in 85% of the cases, indicating that the technology still maintains historical prejudices [

21] (p. 11). For this, the regulatory agencies have started to enforce stricter rules. The EU AI Act requires high-risk systems to maintain event logs while providing detailed documentation and requiring human oversight before deployment [

22] (p. 17), while the U.S. Department of Labor’s AI and Inclusive Hiring Framework provides employers with guidelines for testing recruitment algorithms for discriminatory effects [

23] (p. 12).

Privacy violations raise major concerns regarding abusive practices. The case of the Dutch Data Protection Authority that imposed a EUR 30.5 million fine on Clearview AI for its illegal facial recognition database development is one example in this regard [

24] (p. 21).

Using AI for scams, thefts, and other criminal activities became more and more present. Malicious actors continue to exploit familiar communication methods. The case regarding the use of deep-fake senior executive impersonations by fraudsters who tricked an Arup worker into sending USD 25 million to them is another example [

25] (p. 3). Overall, it is clearer that, besides technical understanding, stricter governance alongside rigorous critical-thinking abilities is needed for successful AI business implementation.

On this premise, the human ability to think critically remains essential for today’s world of artificial intelligence. According to [

26] (p. 1), users need to critically assess generative language model outputs because these models frequently provide confident but misleading answers. The relationship between AI tools usage frequency and critical thinking ability shows a negative connection according to [

27] (pp. 24–25), who found that “cognitive offloading” functions as a mediator to decrease human thinking activity. Leaders need to understand human and organizational aspects of AI implementation according to [

28] (p. 60) for effective AI management. In all those aspects, critical thinking serves as a crucial decision-making component. Ref. [

29] (p. 3) indicates that high AI dependency can lead users to accept flawed results, which shows the requirement for independent judgment. This means that the development of critical thinking skills represents a fundamental requirement for using AI responsibly and efficiently.

2.3. The Cooperation Between Higher Education Institutions and Business

According to [

30], effective collaboration between universities and the business sector requires co-developing curricula aligned with industry needs, involving professionals in academic activities and building sustainable partnerships based on shared objectives, mutual trust and institutional support mechanisms, like policy incentives and formal recognition.

In the complex changing environment due to AI advancements, it is clearer that the relationship between Higher Education institutions and businesses must adapt as well. Labor disruption is accelerating. The current workforce has reduced expectations from global employers because of AI automation tasks amount to 40% [

31] (p. 7). Therefore, the skills and the future workforce will look entirely different from today. Research shows that roles involving repetitive and predictable tasks are more likely to be automated, while jobs requiring human interaction and unstructured problem-solving are less susceptible to AI takeover. Bearing this in mind, higher education must remain flexible and continually adapt to these changes [

32] (p. 20). Ref. [

33] (pp. 2–3) argue that the quality of education in the field of information technology is dependent on the cooperations between leading companies and universities.

Conversely, a large number of higher education leaders still report that their faculties are unfamiliar with or resistant to generative AI, and that their institutions are largely unprepared to equip students for a workforce where AI skills are crucial [

34].

Nevertheless, opportunities for specific types of collaboration between the academic world and businesses arise rapidly. For example, in the USA, the University of Michigan has partnered with Google to offer all its students’ free access to Google Career Certificates, including courses on AI essentials, directly embedding industry-validated training into the academic experience [

35]. Another effective example comes from the newly announced system of California State University. They partnered with global leading companies in technology such as Google, Microsoft, and Adobe to launch a pioneering public–private initiative called “AI Workforce Acceleration Board.” This board’s mission is to align directly university curricula with the AI skills required by California state’s economy and to create industry programs for students [

36]. Likewise, according to the Association of American Universities [

37], OpenAI developed a partnership with fifteen research institutions (including seven AAU universities) in March 2025 with the objective of boosting research breakthroughs and reshape education, providing students the opportunity to experience hands-on learning, guided by an advanced version of OpenAI’s chatbot. This partnership is likely to assist MIT in improving their AI models, Duke University in identifying potential benefits in various scientific fields and Texas A&M in creating more Artificial Intelligence for Education opportunities. The main outcome of this initiative is expected to address the skills gap for young graduates seeking employment with powerful corporations. These models represent a shift to active co-creation, where businesses are not just consumers of talent, but active participants in their development, in close collaboration with Higher Education institutions.

While these ideas are promising, the overall picture also shows challenges in these collaborations between universities and business. Ref. [

38] mentions that, while usually academia is driven by long-term knowledge generation and theoretical exploration, the businesses focus is on the short term and market driven results. Also, despite the fact that some employers require ethical skills, these do not hold significant importance in the hiring process yet, even if graduate literacy in AI governance, regulation, and awareness of potential risks is expected [

39]. Effective partnerships should be made focusing on shared objectives and adaptive coordination mechanisms. Flexible timelines that respect both academic rigor and commercial urgency are essential for success, along with mutual trust and ongoing dialog.

3. Methodology

This study is a qualitative inquiry, based on in-depth interviews with 16 middle-management representatives of international companies. Respondents are active in departments that involve a constant interaction with new employees. As our study focused mostly on young graduates, business representatives’ opinions are most valuable for the purpose of our study.

Data were collected from November 2024 to March 2025. The respondents held middle-management positions in sales, Human Resources, maintenance, production, consultancy, and customer services in international companies that belong to different industries. The 16 respondents were from international companies that operate in Romania (Adobe, OMV Petrom, Dacia Renault, Holcim, McCann, Lear Corporation, Dr. Max, Raiffeisen Bank, On Com, Danfoss, Honeywell). The sample of respondents was selected based on convenience, with the aim of including as many industries as possible and providing a broad perspective across various employee categories. Since the focus of our study is on AI as a tool, used for current tasks at workplaces, we aimed to capture a wider view of the experiences and perceptions of ‘typical’ young employees.

The theoretical framework of this study builds on the theories of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (the influence of internal and external factors on familiarity) and Social Cognitive Theory (familiarity increase self-efficacy), both of which underpin our investigation into AI familiarity. These theories informed the design of our research questions, particularly:

What do businesses consider essential for higher education to provide in terms of AI familiarity among graduates (future employees)?

How do businesses envision the future of collaboration between the corporate sector and higher education institutions concerning the use and implementation of AI in business practices?

Data have been analyzed using Gioia methodology. This methodology allows for a structured data framework that traces the progression of themes from coding stage [

40,

41]. This approach centers on a three-tiered analytical structure:

first-order concepts, which emerge from the participants perspective;

second-order themes, developed through the researcher’s interpretive lens; and

aggregate dimensions, which represent broader theoretical insights [

42]. The appropriateness of Gioia’s methodology for this study stems from the fact that the interviewees are considered to be knowledgeable subjects. Their opinions are valuable for the study, and the interpretation is built upon them.

4. Findings

4.1. Coding and First Order Concept Formation

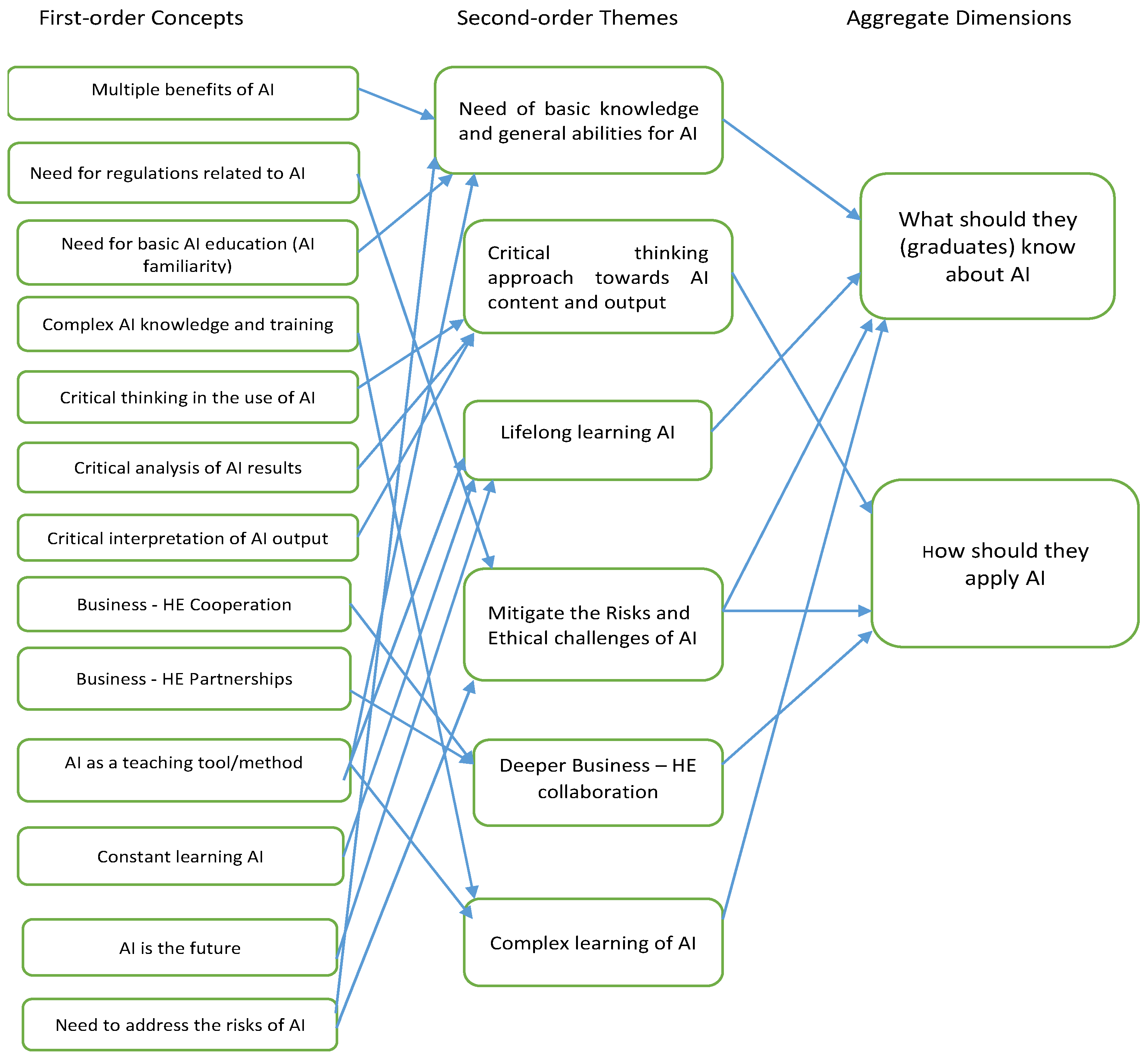

After the transcription of the interviews and revisiting the notes, the research team put together a set of first-order concepts. Thirteen first-order concepts emerged from the interviewees’ comments (see

Figure 1).

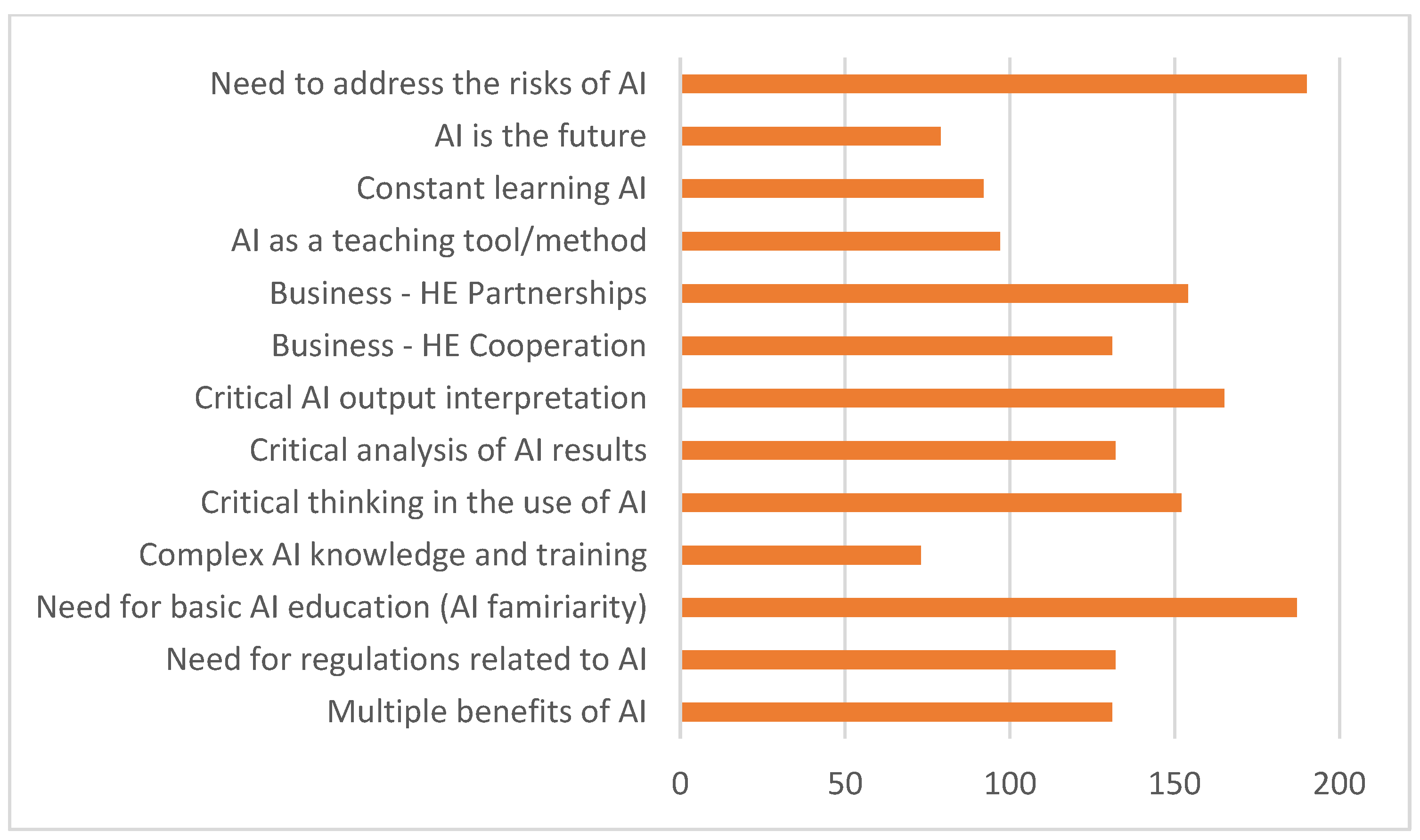

The first question posed for discussion was related to what businesses consider essential for higher education to provide in terms of AI familiarity among graduates (future employees). It was high homogeneity among the opinions expressed by the respondents, reflected by a high frequency registered by all these first order concepts (

Figure 2).

All the respondents mentioned several times the “Need for basic AI education (AI familiarity)” or the “multiple benefits of AI”. The respondents formulated in different ways the need for critical thinking, critical analysis, and critical interpretation related to AI output as an essential part of any kind of training linked to AI use and implementation. Codes as “Critical thinking in the use of AI”, “Critical analysis of AI results”, or “Critical AI output interpretation” registered among the highest frequencies. Ethical aspects and risks associated with AI arose as an important first-order concept. “Need for AI related regulations” scored 132 entries and “Need to address the risks of AI” 190 entries (the highest frequency among first-order concepts). Business representatives expressed the view that AI should be integrated into the educational process (coded as “AI as a teaching tool/method”). They emphasized the importance of recognizing AI as an evolving field that requires ongoing adaptation and learning (coded as “Constant learning AI”) and highlighted their belief that AI will eventually become a normal part of everyday life (coded as “AI is the future”). Additionally, a group of comments was categorized under “Complex AI knowledge and training”, reflecting the idea that developing innovative, efficient, and user-friendly technological solutions demands advanced and sophisticated expertise.

The second question—regarding how businesses envision the future collaboration between the corporate sector and higher education institutions in the context of AI use and implementation in business practices—revealed a strong consensus among respondents. All participants identified various forms of collaboration, such as agreements, case study development, and knowledge-sharing sessions (coded as “Business–HE cooperation”), as well as more structured partnerships including training courses, internships, applied projects, and joint research initiatives (coded as “Business–HE Partnerships”).

4.2. From First-Order Concepts to Second-Order Concepts and Aggregate Dimension

Following the Gioia’s approach, the first order concepts were grouped afterwards in second order concept, shaping a more explicative perspective on graduates’ AI familiarity. Their perspectives concentrate towards six directions: “Need of basic knowledge and general abilities for AI”, “Critical thinking approach towards AI content and output”, “Mitigate the Risks and Ethical challenges of AI”, “Lifelong learning of AI”, “Deeper Business–HE collaboration” and “Complex learning of AI” (

Figure 1).

The second order concept “Need for basic knowledge and general abilities for AI” encompassed four main codes: (1) Multiple benefits of AI, (2) Need for basic AI education (AI familiarity), (3) AI as a teaching tool/method, and (4) Need to address the risks of AI.

The inclusion of the first three codes in this category was anticipated, as businesses generally appear satisfied with a foundational understanding of AI. However, in sectors requiring advanced expertise, views were grouped under the category “Complex learning of AI”.

There was unanimous agreement among respondents that universities should offer dedicated AI courses—both to help students grasp AI functionalities and to provide advanced programs for those seeking specialization and involvement in AI development. As one participant noted: “Universities should include courses dedicated to AI, to help students understand the functionalities of AI technology, but also advanced programs for those who want to specialize and participate in the development of AI” (CB).

Businesses particularly value the practical application of AI education. As one respondent emphasized: “Students would gain enormously from courses that not only explain to them how AI works, but also how to apply it to a real project, in real-world situations” (HT).

This view echoes a longstanding concern in the business community that education remains overly abstract and insufficiently aligned with real-world challenges.

An especially noteworthy finding is the call for AI ethics courses. One participant stated: “It is essential that higher education includes courses dedicated to the ethics of using artificial intelligence in business” (CC). Concerns around biased algorithms are becoming increasingly prominent, making AI ethics a top priority. As another respondent explained: “I believe that these courses should be introduced as a priority in faculties with technical profiles (IT, engineering, etc.), given that graduates from these profiles are more likely to be directly involved in the development and implementation of AI models” (DV).

“Critical thinking approach towards AI content and output” grouped codes as follows: (1) Critical thinking in the use of AI, (2) Critical analysis of AI results, (3) Critical interpretation of AI output. All the respondents use a lot of time developing the importance of critical thinking, some of them considering this aspect as the most important: “Mainly, critical thinking is important, it seems that this ability is being diluted a lot” (CG). Everything that defines AI should have a critical thinking approach: “critical thinking is extremely important—I see a huge wave of people using AI solutions without putting them through the filter of their own thinking” (AS).

Ethical aspects and regulations on AI were present all the time in the discussions. These codes formed the second order concept “Mitigate the Risks and Ethical challenges of AI”. The importance of ethics and regulations related to AI and the risks that emerged from the lack or insufficiency of ethics and rules on AI are very well articulated by the respondents: „the regulation area should be the first to be touched” (AS) or „latest laws and regulations should be incorporate into the AI models” (AZ). Business seems to pay more attention to the ethical skills developed by graduates, and they consider the ethical dimension in teaching AI as much as important as knowledge about AI: „all students should be informed about the benefits that AI can bring in terms of productivity, but also about the dangers related to the information generated by AI” (AZ). “I think it is essential that future employees are not only users of AI, but also to fully understand the impact it has” (CS).

“Lifelong learning AI” grouped codes as AI as a teaching tool/method, Constant learning AI, AI is the future. Business representatives expressed, in different ways, that universities need to foster a mindset in graduates that recognizes we are at the start of a rapidly evolving era, marked by the growing influence of new technologies in both everyday life and traditional business practices. Cultivating habits of continuous learning, sustained exposure to AI, and practical experience in its application is essential for universities moving forward: “we need to learn constantly about the new technologies, as they develop faster and faster” (FN).

Finaly, the last second order concepts that results from interviews is related to the Business–HE collaboration, “Deeper Business–HE collaboration”. First, businesses are very interested in developing partnerships and agreements with HE, and this is not a new aspect. It was expected that this desire to be even more acute, when technological developments are so fast. Businesses note that now, when the pace of technological development is so rapid, this cooperation can further mitigate the inertia, partly natural, that education has towards the development of the labor market. These partnerships that the business wants to develop allow for increased adaptability to the labor market and a much more applicative dimension of the educational process: “universities can’t always anticipate the precise skills needed in real-world settings. By collaborating, we can help shape the training of future employees—ensuring they not only understand AI in theory but also know how to apply it effectively in practice” (CS).

Two aggregate dimensions emerged from the interviews analysis. As illustrated in

Figure 1, business’ opinion is heading towards two dimensions of the AI familiarity:

what they should know and

how they should apply it. These aggregate dimensions proposed by this study are grounded in TAM and Social Cognitive Theory. TAM directly informed the analysis of the

“what should they know” dimension of AI familiarity based on the influence of external and internal factors—such as exposure to AI, perceived usefulness, and self-efficacy—on attitudes toward technology use [

11,

13,

43,

44]. Social Cognitive Theory (the roles of observation, continuous learning, and self-efficacy in shaping behaviors) offers key elements to interpreting the second dimension,

“how should they apply it”, particularly the emphasis on critical thinking, ethical awareness, and lifelong learning [

9,

10,

11,

12].

5. Discussions

The dual framework outlined by the two aggregate dimensions introduces a practical reconceptualization of AI familiarity that aligns cognitive understanding with behavioral and ethical application, a perspective that is underdeveloped in the current literature.

The first dimension—

what graduates should know about AI—centers around the satisfaction expressed by the business sector with the AI familiarity their employees have. Familiarity is very important in accepting technological changes [

13,

43]. Employers appreciate that graduates are increasingly familiar with AI and show a willingness to apply it in business contexts. According to data presented in this study, this sense of satisfaction can be attributed to at least two key factors. One, highlighted by a respondent’s comment, relates to the relatively low percentage of companies that currently integrate AI into their core operations. As a result, the fact that employees possessing even a basic understanding of AI is seen as a valuable asset and a step forward for technologically aspiring organizations may indicate that AI integration within the core business operations remains at a relatively low level. Despite the high figures showed by McKinsey reports [

17], the respondent considers that “Currently, only 1.5% of companies in Romania are using AI, which suggests that many employers themselves may not yet have a clear understanding of what skills to expect from employees when it comes to using and implementing AI” (DM). Employees’ familiarity with artificial intelligence (AI), while important, is insufficient for businesses to fully realize the potential efficiency gains that AI can offer [

45]. Organizations must be strategically prepared to implement and integrate AI effectively; otherwise, the performance gap between industry leaders and the others is likely to widen [

45]. Furthermore, scholars have raised concerns about the potential for AI investment to exacerbate global economic polarization and marginalization. Concentration of AI-related investments in a limited number of countries could deepen economic disparities between nations. Nobel Prize-winning economist Simon Johnson highlights the extent of this concentration, noting that approximately 95 percent of global AI development spending occurs in the United States, 3 percent in Europe, and 2 percent in the rest of the world—excluding China, for which reliable expenditure data is unavailable [

46] (p. 67).

A second factor could be that businesses are looking more for a mindset oriented towards AI adoption rather than deep technical expertise—except in industries directly involved in developing AI technologies. Given the rapid pace of technological advancement, what matters most to companies is that graduates are open to learning, adaptable, and capable of applying AI tools effectively in real-world situations. Rather than expecting in-depth AI knowledge, businesses emphasize the importance of broader skills—particularly the ability to know, understand, manage, and mitigate the risks and challenges associated with AI implementation. Studies showed that familiarity with AI affects positively the perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness of AI, which is critical important for business success [

11,

13,

43,

44].

The second dimension is

“how should they apply AI”. This was the most consistent theme that recalled critical thinking, ethical approach, and collaboration with businesses. Many members of the Generation Z, while quite proficient in using digital tools and quick to adopt new technologies, often show a limited degree of critical thinking when it comes to understanding the broader implications of artificial intelligence [

47,

48,

49]. They tend to focus on the functionality and convenience AI offers, without fully considering its limitations, potential risks, or long-term consequences (data privacy, algorithmic bias) [

50]. Additionally, there appears to be a lower level of engagement with the ethical dimensions of AI use—such as fairness, transparency, and accountability. As AI becomes more deeply embedded in everyday life and the workplace, it is increasingly important to cultivate a mindset that not only values innovation but also questions about its responsible use and mostly, about applying AI in a responsible way [

48]. Encouraging this kind of awareness, and mostly, an ethical behavior towards AI use should be a priority. Business collaboration plays a crucial role in shaping future-ready graduates. As it was already mentioned, greater involvement of industry in curriculum design, developing real-world scenarios for students to solve, and forming strong partnerships with universities can significantly enhance the quality of education [

35,

36,

37,

51]. This collaboration not only helps produce graduates who are better aligned with labor market needs but also ensures they are equipped with essential skills for effective AI use, in a responsible way. These include critical thinking, ethical awareness, and practical problem-solving abilities. By bridging the gap between academic knowledge and industry expectations, such partnerships foster more responsible and capable professionals in an AI-driven world.

6. Conclusions

The purposes of this study were to investigate the opinion of businesses’ representatives of international corporations on what businesses consider essential for Higher Education to provide in terms of AI familiarity of graduates and how they see the future of collaboration between the corporate sector and Higher Education institutions concerning the use and implementation of AI in business practices. The researchers employed a qualitative enquiry to explore these opinions, and they adapted Gioia’s methodology to identify patterns of these opinions and their significance.

Our study contributes to the literature by offering a conceptual advancement in how AI familiarity is understood from a business perspective—shifting the discussion from a purely technical or educational lens to a practical, employer-centered framework. By using Gioia’s methodology to extract grounded insights from industry professionals across sectors, we identify two novel aggregate dimensions of AI familiarity: (1) what graduates should know about AI, and (2) how they should apply it. This dual framework introduces a practical reconceptualization of AI familiarity that aligns cognitive understanding with behavioral and ethical application, a perspective that is underdeveloped in the current literature. These contributions offer actionable insights for both scholars and policymakers in AI education, particularly in business and management fields, where applied AI competencies are increasingly vital.

For scholars, the findings of this empirical study provide further evidence underscoring the necessity of adopting a multifaceted approach to AI implementation in higher education—addressing both the knowledge necessary for understanding AI and its practical application for business purposes. Such an approach ensures that graduates are equipped not only with cognitive skills about AI but also with the capacity to translate this knowledge into value-creating practices within organizational contexts, in a responsible manner. Moreover, integrating these dimensions into higher education curricula can bridge the gap between academic preparation and market demands, fostering a workforce that is agile, technologically competent, responsible, and capable of navigating the evolving digital economy.

In general, businesses need basic knowledge related to AI use for various purposes, except for the case of those graduates that are supposed to “create” AI, who need deep knowledge in Computer Science, algorithms, mathematics, and other specific disciplines necessary to create AI. For the majority of businesses, basic knowledge about AI is sufficient. In general, organizations want the graduate to be “fertile ground”, ready “for sowing”, where each business, depending on its specifics and its strategic objectives in the short, medium or long term, can plant those “seeds” that will bring profit. This fertile ground actually represents AI familiarity, which, for businesses, actually means a positive attitude towards AI (and new technologies in general), the ability and desire to learn continuously, and the ability “to juggle”, to adapt to what new technology brings.

The dimension of how individuals should apply their knowledge of AI—or how to demonstrate AI familiarity in practice—emerged as a top priority for businesses. This practical application is seen as the greatest challenge, reflecting a broader concern around the need for a critical and ethical approach to AI use. As one respondent aptly put it, “garbage in, garbage out.” Employers are looking for individuals who can evaluate AI-generated outputs critically, determine their accuracy based on evidence, and avoid accepting results at face value without thoughtful analysis.

This perspective emphasizes that decision-making must remain human-led, grounded in responsibility, compliance with legal standards, and adherence to ethical principles. Accordingly, several respondents stressed that courses on AI ethics and critical thinking are even more essential than technical AI training itself.

There is a growing concern within the business community about the decline in critical thinking skills. Some fear that as AI familiarity increases, it could surpass the development of ethical awareness and critical reasoning—leading to uncritical acceptance of AI outputs and poor decision-making. This highlights a key business priority: ensuring that AI competence is balanced with ethical responsibility and reflective judgment.

Some respondents also expressed criticism toward employers’ ability to identify graduates with strong AI competencies, both in terms of technical familiarity and the ability to apply critical thinking and ethical judgment. These critiques are rooted in the observation that only a small percentage of companies currently use AI for strategic business purposes. As a result, many of these organizations lack clarity about the AI-related skills they should be seeking in potential employees. In such cases, AI is typically applied to low-level tasks—such as drafting messages or generating simple reports—rather than being integrated into more strategic or impactful business functions. This limited use hampers employers’ ability to articulate more sophisticated requirements and expectations regarding AI capabilities in their workforce.

The second topic of discussion—how businesses envision future collaboration with Higher Education institutions regarding the use and implementation of AI in business practices—led to largely predictable yet unanimous conclusions. All respondents agreed that partnerships and various forms of collaboration are essential for enhancing the practical skills of graduates. For example, one suggestion involved teaching students how to use tools like ChatGPT to analyze and improve business strategies. Some large corporations have already launched joint initiatives aimed at bridging the gap between education and industry, ensuring that academic training remains relevant to real-world business needs while also fostering closer ties between businesses and universities.

These findings are relevant for policymakers as well. As AI continues to transform the labor market, educational policies must proactively address the multifaceted challenges arising from these disruptive technologies. In the pursuit of enhancing employability, policymakers require robust, evidence-based frameworks not only to inform the design and development of educational strategies but also to establish regulatory mechanisms that foster technological advancement while ensuring the ethical deployment of AI. This entails the creation of comprehensive standards for data protection, privacy, and cybersecurity, thereby safeguarding both individuals and institutions from potential risks. Strengthening governance in these areas is essential to promote public trust and to ensure that the societal benefits of AI are realized equitably and responsibly.

As a final remark, Artificial Intelligence represents an inevitable and integral part of the future landscape. The critical challenge moving forward lies in maximizing its potential benefits while safeguarding ethical standards, promoting responsible use, and ensuring alignment with societal and human values.

7. Limits of the Study

This study is subject to certain inherent limitations. Due to its qualitative design, the findings cannot be generalized to the all international companies nor to other companies. Furthermore, the respondents, despite the international dimension of the companies they are working for, may have a perception generated by their Romanian experience. However, the exploratory nature of the research aims to outline a preliminary framework reflecting the business perspective on the desired level of AI familiarity among graduates and can be a starting point for further research. The analysis does not account for industry-specific characteristics, based on the premise that each sector possesses unique dynamics and requirements. Nevertheless, this research provides a valuable foundation for future investigations—such as studies focused on industry-specific expectations or the relationship between digital skill levels and AI adoption in business contexts.