Corruption: An Uneven Field of Research—Between State and Private Topics

Abstract

1. Introduction

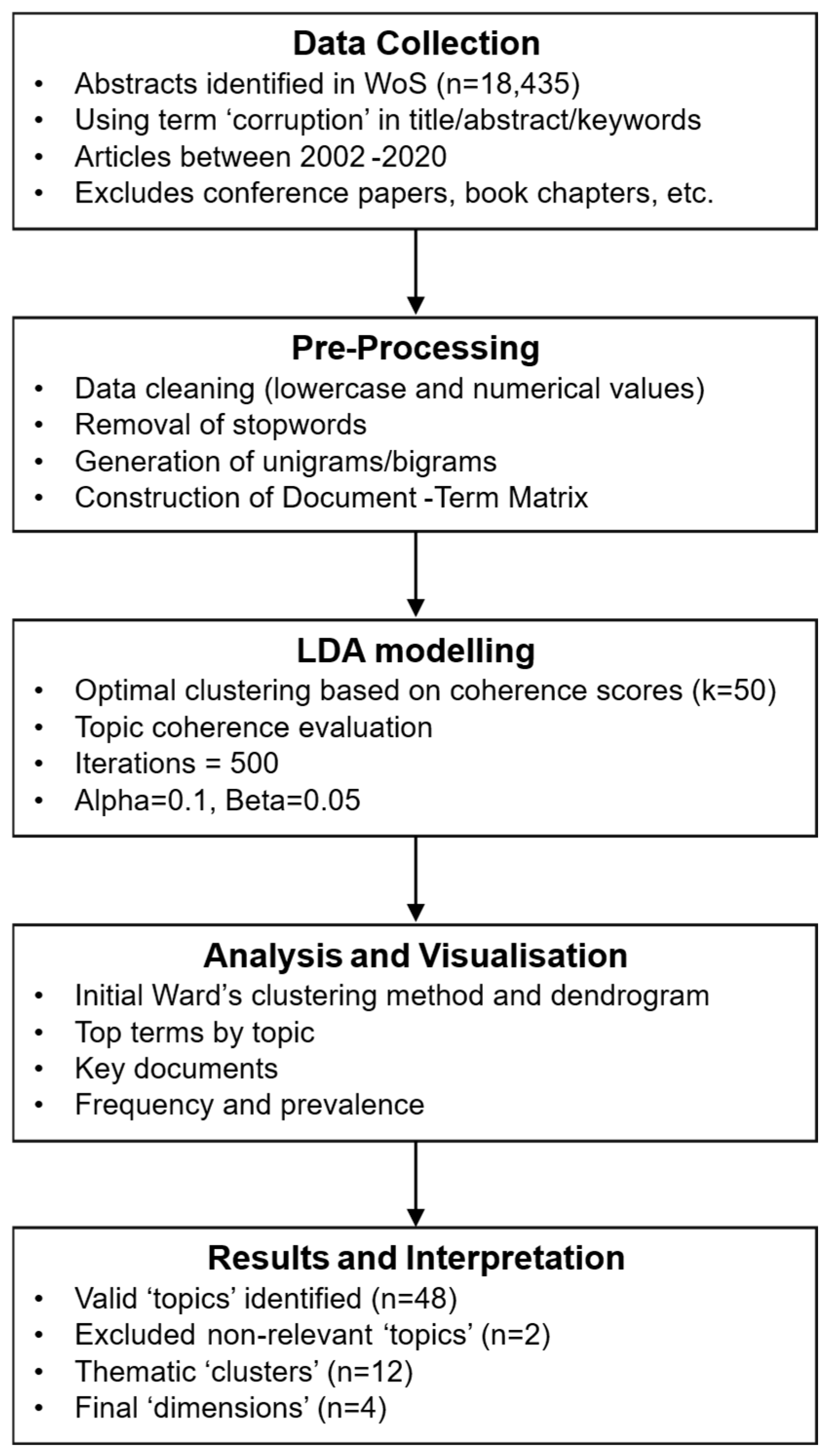

2. Material and Methods

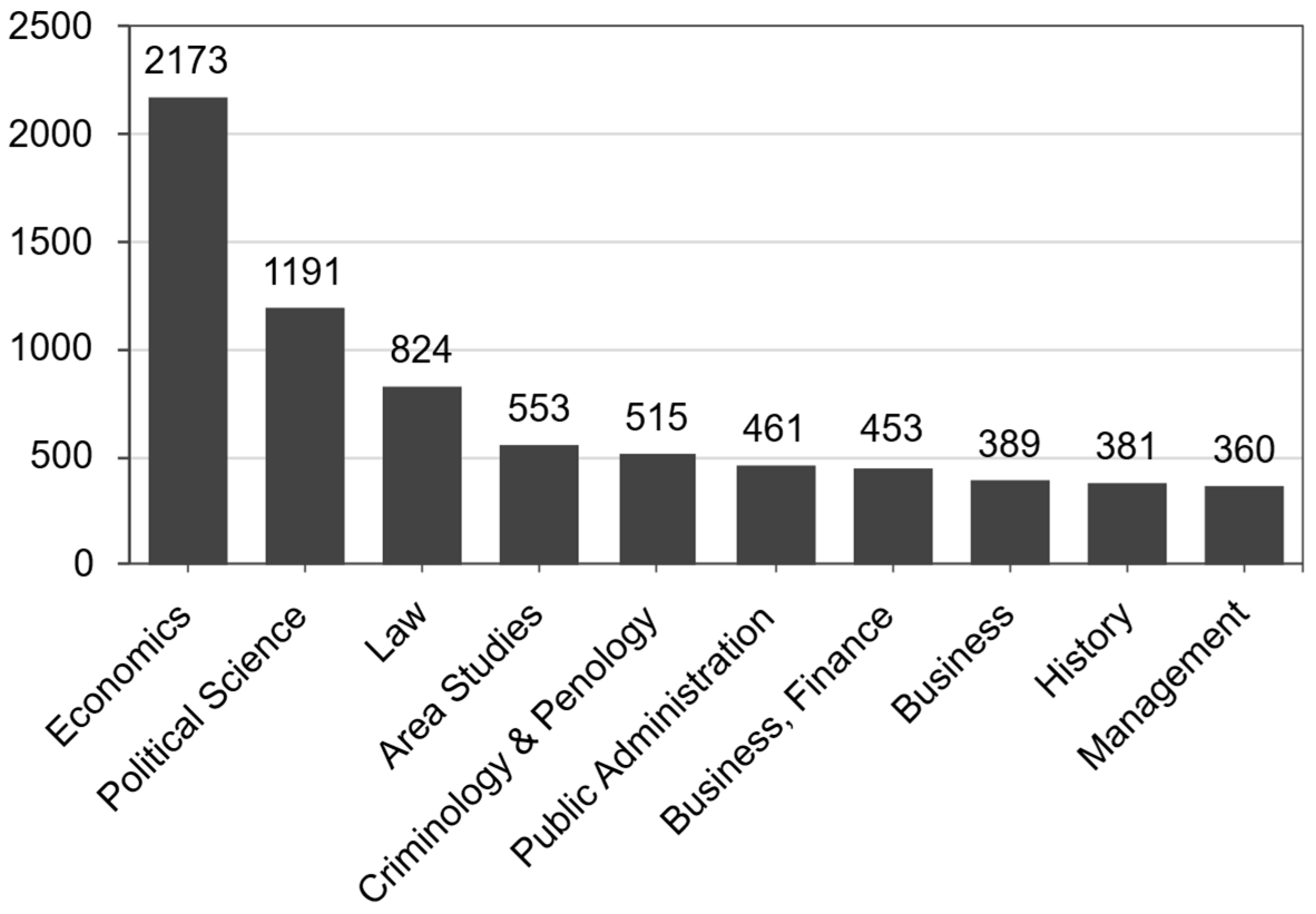

2.1. Data

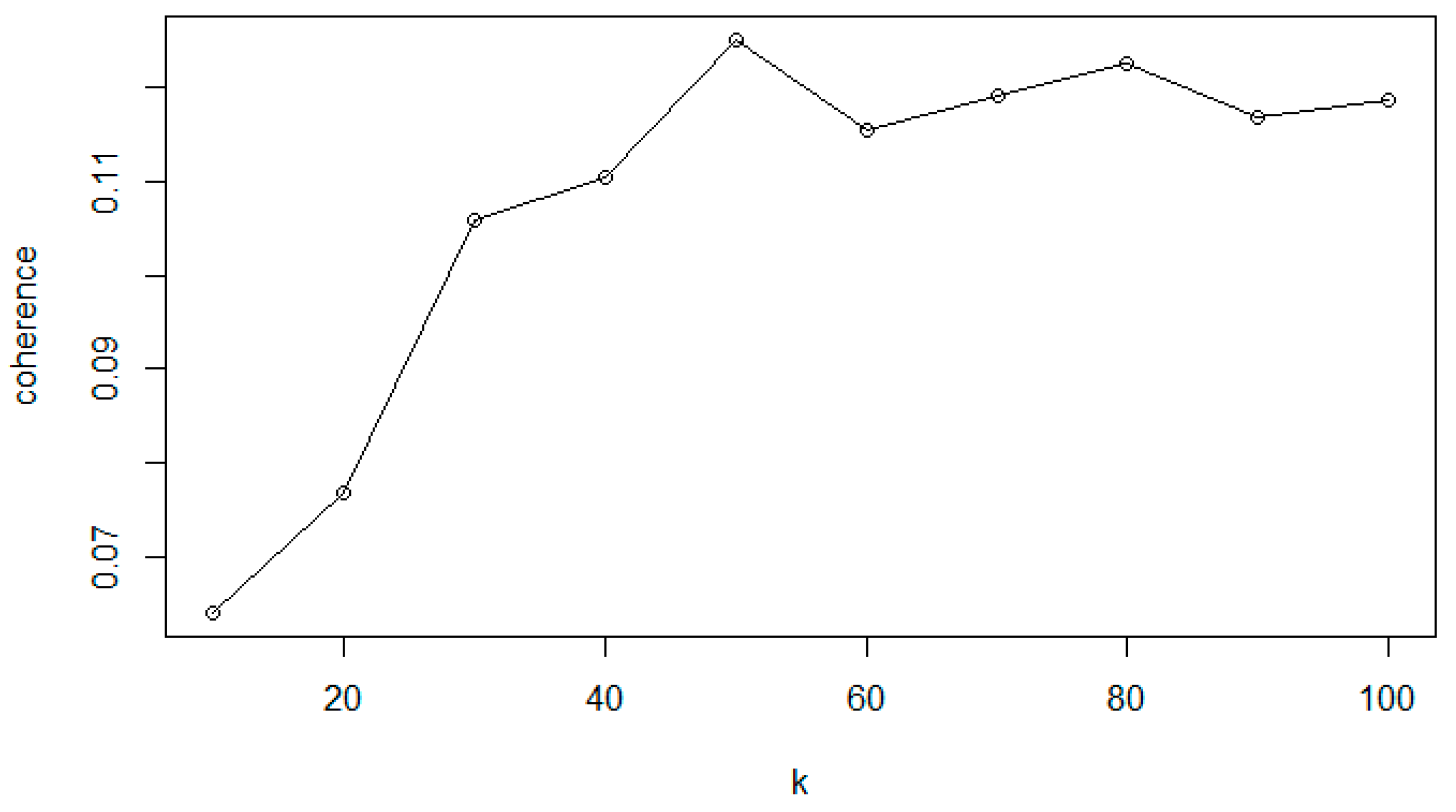

2.2. LDA Topic Model

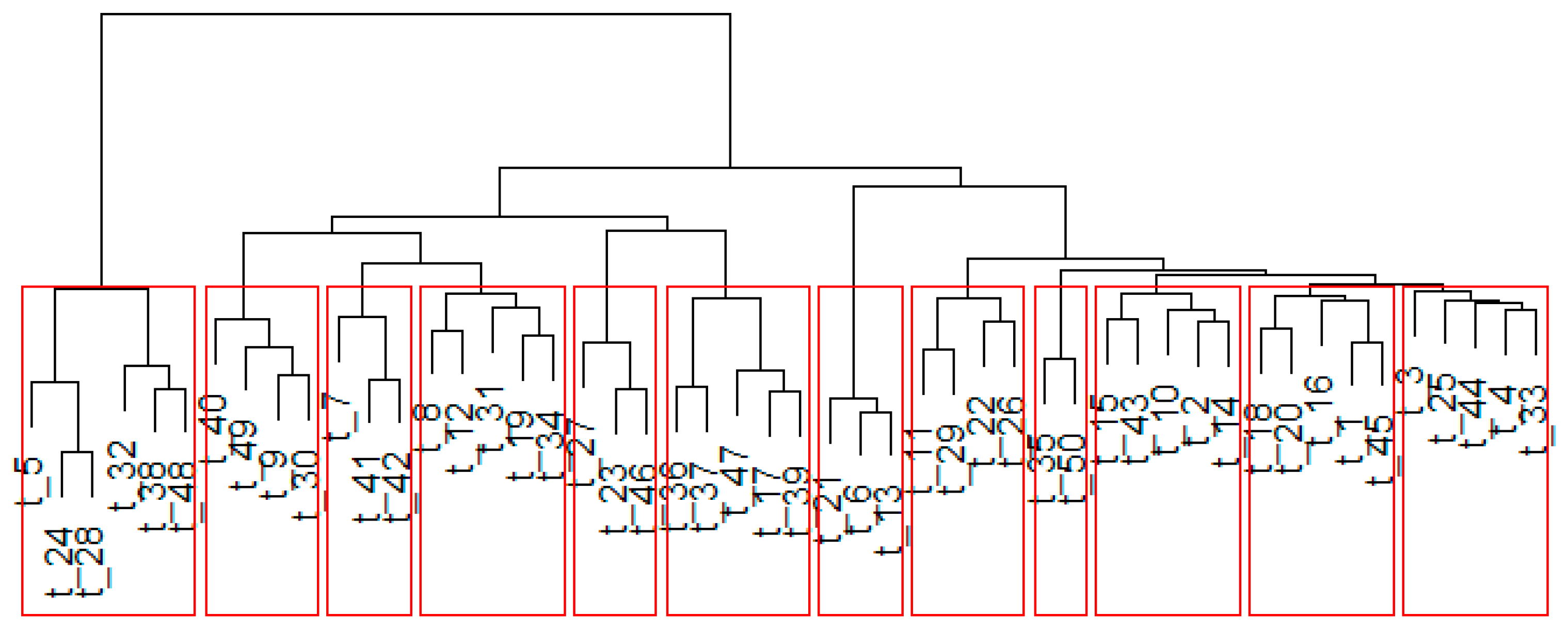

2.3. Clustering

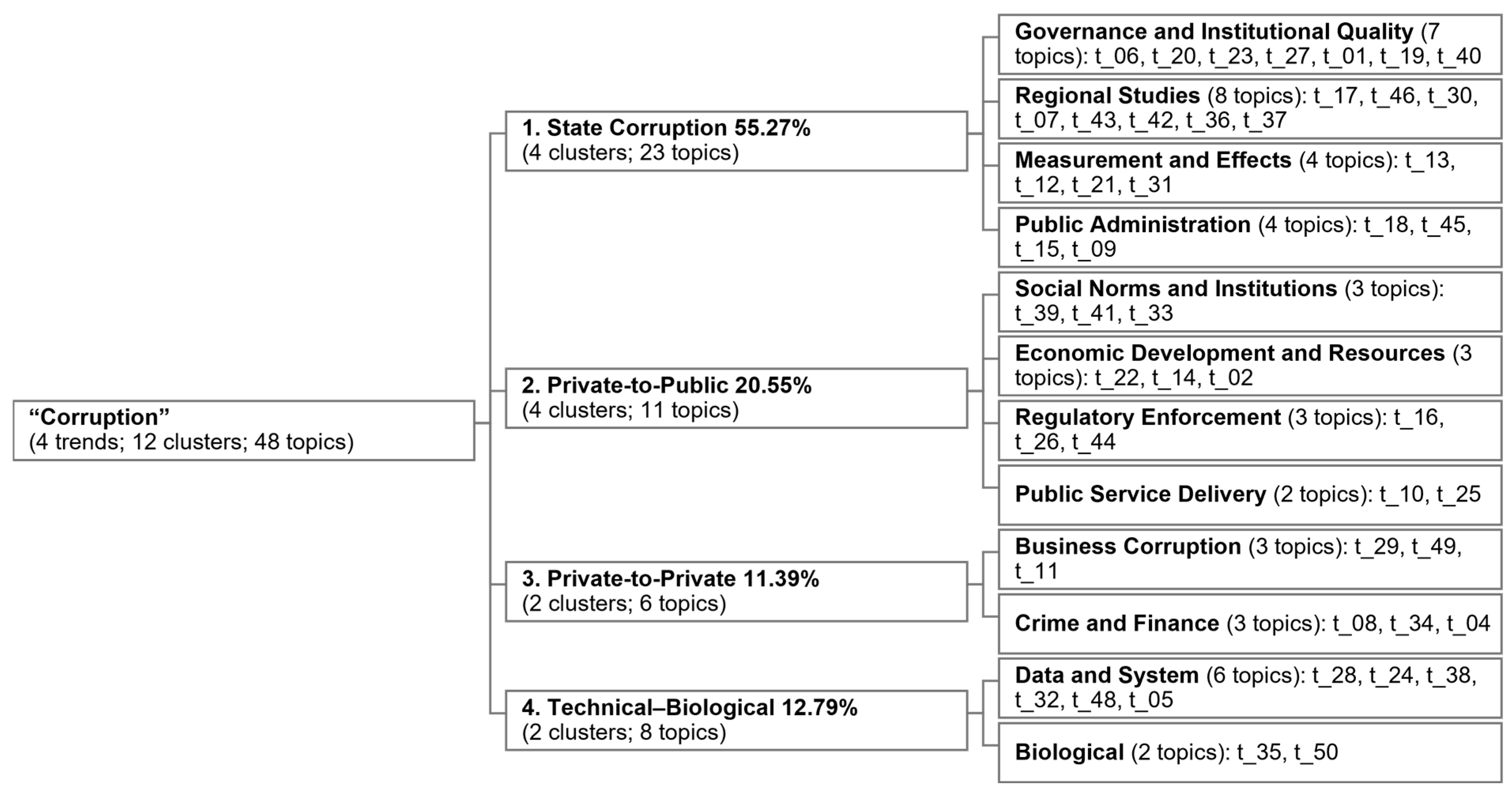

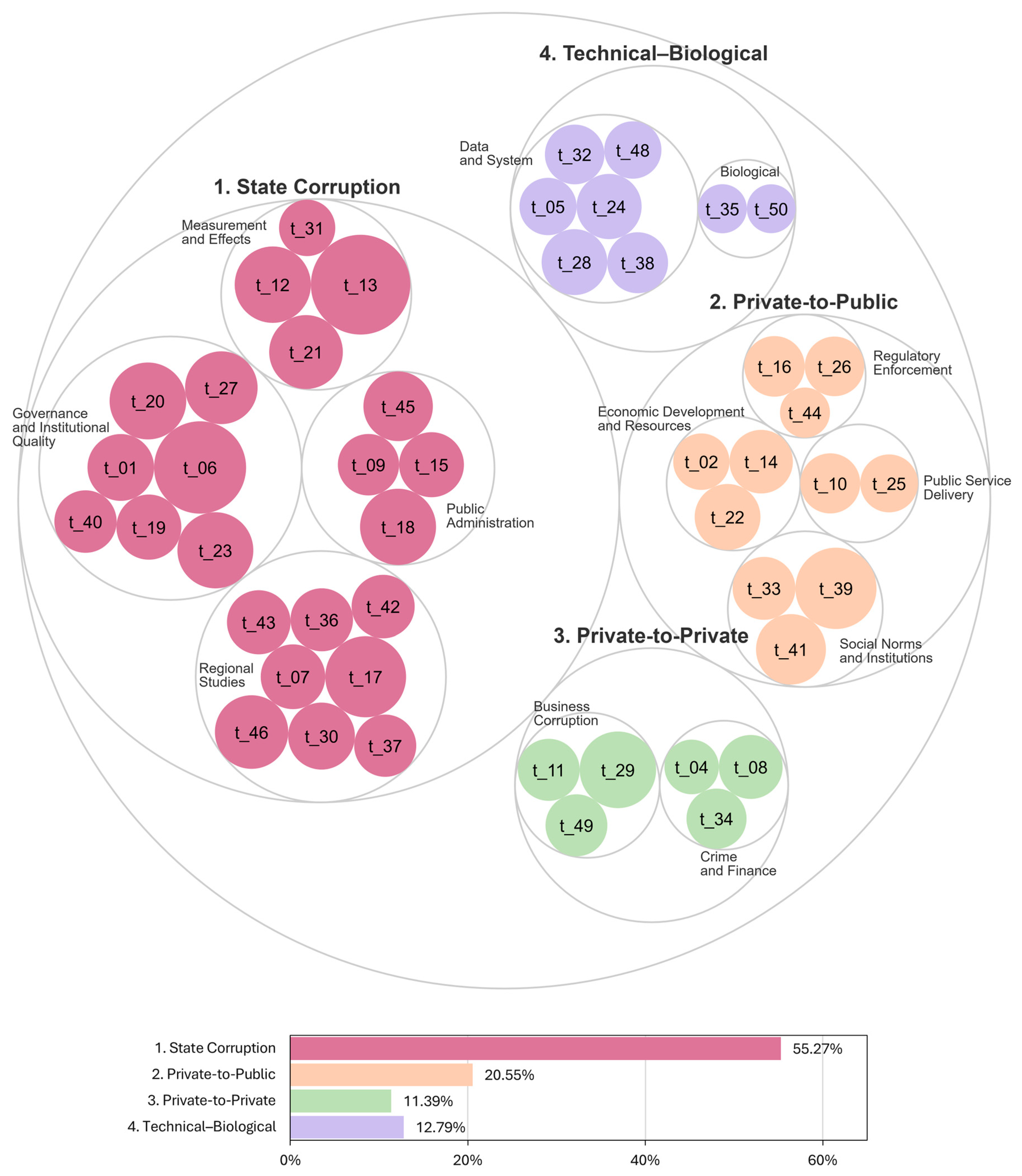

3. Results

3.1. State Corruption

3.2. Private-to-Public

3.3. Private-to-Private

3.4. Technical–Biological Corruption

4. Discussion: The Place of Non-State Corruption in the Literature

4.1. Common Elements and Differences Across Dimensions

4.2. A New Conceptual Framework: Corruption as Operational Deviation

4.3. Implications for Non-State Corruption Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dimension | Cluster | id | Topic | Keywords | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. State Corruption | Governance and Institutional Quality | t_06 | Corruption and economic development | economic, growth, quality, countries, institutional, economic_growth, development, governance, study, results | 4.00% |

| t_20 | Fighting corruption | corruption, anti, anti_corruption, corrupt, paper, anticorruption, measures, fight, problem, article | 2.78% | ||

| t_23 | Anti-corruption reforms | state, political, article, power, reforms, institutions, institutional, reform, argues, politics | 2.72% | ||

| t_27 | Partisan corruption | political, party, electoral, parties, elections, politicians, election, voters, vote, candidates | 2.48% | ||

| t_01 | Good practices | governance, government, transparency, accountability, information, good, public, good_governance, society, civil | 2.09% | ||

| t_19 | Corruption and ethics education | ethical, education, ethics, students, leadership, behavior, business, organizational, moral, study | 1.99% | ||

| t_40 | Rule of Law in the EU | european, eu, law, countries, rule, union, rights, europe, rule_law, human | 1.83% | ||

| Regional Studies | t_17 | Corruption in Eastern Europe | policy, development, challenges, research, paper, issues, literature, developing, implementation, problems | 3.09% | |

| t_46 | Corruption in Latin America | political, democracy, democratic, latin, politics, corruption, social, america, economic, regime | 2.54% | ||

| t_30 | Corruption in Russian institutions | legal, law, criminal, corruption, crimes, legislation, article, authors, russian, system | 2.11% | ||

| t_07 | Corruption in Africa | africa, south, african, conflict, article, war, south_africa, corruption, post, ethnic | 1.97% | ||

| t_43 | Corruption in the East | china, chinese, government, party, reform, corruption, economic, system, indonesia, officials | 1.91% | ||

| t_42 | Corruption in British colonies | century, fraud, corruption, article, history, case, early, period, british, government | 1.88% | ||

| t_36 | Corruption in Soviet countries | economy, economic, development, shadow, ukraine, state, system, shadow_economy, research, analysis | 1.84% | ||

| t_37 | Corruption in the Soviet Union | russia, economic, russian, soviet, society, political, social, post, state, corruption | 1.82% | ||

| Measurement and Effects | t_13 | Effects of corruption | corruption, countries, effect, effects, results, level, find, data, levels, relationship | 4.67% | |

| t_12 | Perceptions of corruption | trust, survey, perceptions, citizens, corruption, perceived, data, study, attitudes, support | 2.74% | ||

| t_21 | Measuring corruption | countries, level, index, factors, corruption, country, indicators, data, variables, analysis | 2.56% | ||

| t_31 | Effects on the population | women, gender, social, female, family, men, sexual, young, male, age | 1.49% | ||

| Public Administration | t_18 | Public officials | corruption, corrupt, bribe, model, bribery, bribes, behavior, officials, costs, game | 2.73% | |

| t_45 | Corruption in the State | public, private, sector, procurement, service, public_sector, government, services, administration, public_procurement | 2.28% | ||

| t_15 | Corruption in local government | local, land, urban, water, government, community, rural, communities, management, development | 1.98% | ||

| t_09 | Corruption in US institutions | court, campaign, law, judicial, corruption, federal, finance, courts, whistleblowing, article | 1.77% | ||

| 2. Private-to-Public | Social Norms and Institutions | t_39 | Corruption and social capital | social, corruption, article, theory, practices, understanding, research, institutional, cultural, analysis | 3.10% |

| t_41 | Corruption in religious institutions | corruption, religious, article, century, essay, language, text, history, church, texts | 2.31% | ||

| t_33 | Corruption in the media and social networks | media, corruption, news, analysis, social, public, political, discourse, article, press | 1.86% | ||

| Economic Development and Resources | t_22 | Corruption and investment | investment, foreign, fdi, countries, trade, country, direct, foreign_direct, host, direct_investment | 2.04% | |

| t_14 | Corruption and inequality | resource, inequality, income, social, natural, poverty, resources, economic, capital, poor | 1.90% | ||

| t_02 | Rent-seeking | oil, term, rent, seeking, long, rent_seeking, long_term, short, nigeria, economic | 1.50% | ||

| Regulatory Enforcement | t_16 | Tax evasion | tax, fiscal, government, decentralization, debt, tourism, revenue, evasion, taxes, tax_evasion | 1.72% | |

| t_26 | Corruption in aid | informal, aid, formal, institutions, entrepreneurship, countries, institutional, development, business, entrepreneurial | 1.67% | ||

| t_44 | Corruption and real estate projects | construction, projects, de, project, risk, la, industry, infrastructure, risks, real | 1.18% | ||

| Public Service Delivery | t_10 | Corruption and pollution | environmental, energy, pollution, trade, emissions, forest, climate, conservation, sustainability, supply | 1.70% | |

| t_25 | Corruption and public health | health, care, medical, health_care, healthcare, payments, services, system, public_health, workers | 1.57% | ||

| 3. Private-to-Private | Business Corruption | t_29 | Corruption in business | firms, firm, business, performance, political, enterprises, find, corporate, bribery, innovation | 2.76% |

| t_49 | Compliance in the USA | international, states, united, enforcement, bribery, compliance, global, law, foreign, united_states | 1.81% | ||

| t_11 | Corporate corruption | financial, corporate, bank, market, risk, banks, banking, companies, crisis, governance | 1.81% | ||

| Crime and Finance | t_08 | Corruption and organized crime | crime, police, criminal, security, organized, trafficking, violence, officers, drug, organized_crime | 1.92% | |

| t_34 | Money laundering | money, moral, laundering, money_laundering, human, people, corruption, paper, life, good | 1.70% | ||

| t_04 | Corruption in sporting events | sport, sports, football, match, fixing, disaster, match_fixing, events, disasters, games | 1.40% | ||

| 4. Technical–Biological | Data and System | t_28 | Facial recognition and processing | data, method, robust, sparse, proposed, based, low, problem, representation, rank | 2.04% |

| t_24 | Corruption of images | noise, proposed, image, method, based, images, model, performance, corruption, results | 2.00% | ||

| t_38 | Corruption of data | errors, data, error, memory, fault, corruption, performance, system, based, software | 1.74% | ||

| t_32 | Corruption of networks and security | network, model, protocol, scheme, corruption, security, protocols, communication, based, networks | 1.67% | ||

| t_48 | Corruption of computer systems | data, system, information, systems, storage, time, security, corruption, based, integrity | 1.54% | ||

| t_05 | Signal and data corruption | data, signal, motion, time, corruption, method, signals, imaging, phase, measurement | 1.54% | ||

| Biological | t_35 | Corruption of cells | cells, cancer, cell, corruption, expression, patients, results, fas, control, dna | 1.13% | |

| t_50 | Corruption of biological processes | corruption, results, surface, analysis, study, water, process, properties, samples, effect | 1.12% |

| 1. | The data was consulted and extracted on 21 July 2021. The initial year corresponds to when WoS began providing complete article data on its platform (i.e., inclusion of SSCI and AHCI). We set 2020 as the end date, when data collection was conducted, which additionally allowed us to analyze established research patterns without the distortions introduced by the COVID-19 pandemic as an emergent research topic. |

| 2. | The frequencies shown in the graph correspond to the labels provided by WoS itself. The top categories are therefore mutually exclusive. However, there are articles that may have more than one category (i.e., an article could be in the intersection between economics and law) and therefore do not contribute to the total of any of them but correspond to a new category (e.g., “Business, Finance” in Figure 1). Because of this, the frequencies of the presented categories could be underrepresented. |

| 3. | Different topic modeling approaches exist in text mining. Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) uses matrix decomposition but lacks probabilistic interpretation [13]. Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) improves interpretability by constraining values to be non-negative [14]. Probabilistic LSA (pLSA) introduces statistical frameworks but can overfit [15]. The Hierarchical Dirichlet Process (HDP) automatically determines topic numbers but is computationally intensive [16]. Newer methods include Structural Topic Models (STMs) incorporating metadata and Dynamic Topic Models (DTMs) for temporal analysis [17]. LDA was selected for its balanced approach, combining probabilistic foundations with computational efficiency and interpretable results. |

| 4. | Silge & Robinson [12] briefly explain the workings of these methods with their advantages and disadvantages. LDA is especially popular for fitting topic models because it performs a two-stage analysis. First, this method understands that each document is a mixture of topics and, second, each topic is a mixture of words. Given this structure, documents can overlap thematically rather than being categorized in a mutually exclusive way, which provides a better analysis. |

| 5. | It is worth noting that classical approaches to corruption, particularly those based on virtue theory and deontological ethics, have historically provided foundational frameworks for understanding corruption as moral transgression [28,29,30]. While these perspectives are primarily documented in books and philosophical treatises rather than scientific articles, their influence pervades contemporary corruption research [31,32,33]. Our analysis of the WoS-indexed literature reveals how these moral and philosophical foundations have been complemented by more empirically oriented research frameworks, showing the field’s evolution from purely moral considerations to include structural and institutional dynamics, while maintaining corruption’s fundamental character as a deviation from ethical principles and established procedures. |

| 6. | It is relevant to clarify that this dimension does not represent a categorization proposed by the authors but rather an alternative use of the term “corruption” that emerges directly from our empirical analysis of the scientific literature. In disciplines such as computer science, engineering, and biology, “corruption” is used to describe processes of deterioration, degradation, or destruction in technical and biological systems. |

References

- Heidenheimer, A.; Johnston, M. Political Corruption. Concepts & Contexts; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-7658-0761-8. [Google Scholar]

- Tanzi, V. Corruption Around the World: Causes, Consequences, Scope, and Cures. IMF Staff Pap. 1998, 45, 559–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treisman, D. The Causes of Corruption: A Cross-National Study. J. Public Econ. 2000, 76, 399–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, P. Corruption and Growth. Q. J. Econ. 1995, 110, 681–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, P. Corruption and Development: A Review of Issues. J. Econ. Lit. 1997, 35, 1320–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, C.W.; Kaufman, D. Corruption and Development; PREM Notes; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Argandoña, A. Private-to-Private Corruption. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 47, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H. Insider Trading as Private Corruption. UCLA Law Rev. 2014, 61, 928–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.J. Corruption, NGOs, and Development in Nigeria. Third World Q. 2010, 31, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivunovic, M. Countering NGO Corruption: Rethinking the Conventional Approaches. AntiCorruption Resour. Cent. 2011, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley, P. Big Fish, Small Pond: NGO–Corporate Partnerships and Corruption of the Environmental Certification Process in Tasmanian Aquaculture. Crit. Criminol. 2020, 28, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silge, J.; Robinson, D. Text Mining with R: A Tidy Approach; O’Reilly: Springfield, MI, USA, 2017; ISBN 1-4919-8162-8. [Google Scholar]

- Deerwester, S.; Dumais, S.T.; Furnas, G.W.; Landauer, T.K.; Harshman, R. Indexing by Latent Semantic Analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1990, 41, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.D.; Seung, H.S. Learning the Parts of Objects by Non-Negative Matrix Factorization. Nature 1999, 401, 788–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, T. Probabilistic Latent Semantic Analysis. In Proceedings of the UAI, Stockholm, Sweden, 30 July–1 August 1999; Volume 99, pp. 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Teh, Y.; Kurihara, K.; Welling, M. Collapsed Variational Inference for HDP. In NIPS’07: Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 3–6 December 2007; Curran Associates Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Volume 20, pp. 1481–1488. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M.E.; Stewart, B.M.; Tingley, D.; Lucas, C.; Leder-Luis, J.; Gadarian, S.K.; Albertson, B.; Rand, D.G. Structural Topic Models for Open-Ended Survey Responses. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 2014, 58, 1064–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmussen, C.B.; Møller, C. Smart Literature Review: A Practical Topic Modelling Approach to Exploratory Literature Review. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunleye, B.; Lancho Barrantes, B.S.; Zakariyyah, K.I. Topic Modelling through the Bibliometrics Lens and Its Technique. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lei, L. A Bibliometric Analysis of Topic Modelling Studies (2000–2017). J. Inf. Sci. 2021, 47, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Doane, W.; Jones, M.T. Package ‘textmineR.’ Functions for Text Mining and Topic Modeling. 2018. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/textmineR/textmineR.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Ward, J.H. Hierarchical Grouping to Optimize an Objective Function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zou, W.; Chen, J.J. Topic Modeling for Cluster Analysis of Large Biological and Medical Datasets. BMC Bioinform. 2014, 15, S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchene, L.; Safari, W. Two-Stage Topic Modelling of Scientific Publications: A Case Study of University of Nairobi, Kenya. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0243208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, R.; Yu, J. A Topic Modeling Comparison between Lda, Nmf, Top2vec, and Bertopic to Demystify Twitter Posts. Front. Sociol. 2022, 7, 886498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, D.; Dymnicki, A.B.; Mohatt, N.; Allen, J.; Kelly, J.G. Clustering Methods with Qualitative Data: A Mixed-Methods Approach for Prevention Research with Small Samples. Prev. Sci. 2015, 16, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, F.; Legendre, P. Ward’s Hierarchical Clustering Method: Clustering Criterion and Agglomerative Algorithm. J. Classif. 2014, 31, 274–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, R. Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gregor, M. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, A. After Virtue; A&C Black: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- De Graaf, G. Causes of Corruption: Towards a Contextual Theory of Corruption. Public Adm. Q. 2007, 31, 39–86. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D.F. Political Ethics and Public Office; Harvard University Press: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein, B.; Varraich, A. Making Sense of Corruption; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein, B.; Teorell, J. What Is Quality of Government? A Theory of Impartial Government Institutions. Governance 2008, 21, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quah, J.S. Five Success Stories in Combating Corruption: Lessons for Policy Makers. Asian Educ. Dev. Stud. 2017, 6, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungiu-Pippidi, A. The Quest for Good Governance: How Societies Develop Control of Corruption; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D.; Robinson, J.A. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty; Crown Currency: Sydney, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, A.; Rothstein, B.; Teorell, J. Why Anticorruption Reforms Fail—Systemic Corruption as a Collective Action Problem. Governance 2013, 26, 449–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R. The Quality of Government. J. Law Econ. Organ. 1999, 15, 222–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, T.P.; Mendelson, S.E. Public Experiences of Police Violence and Corruption in Contemporary Russia: A Case of Predatory Policing? Law Soc. Rev. 2008, 42, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.H. Determinants of Corruption in Developing Countries: The Limits of Conventional Economic Analysis. In International Handbook on the Economics of Corruption; Edward Elgar Publishing: Camberley, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.J. Corruption and “Culture” in Anthropology and in Nigeria. Curr. Anthropol. 2018, 59, S83–S91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.C. Bad Loans to Good Friends: Money Politics and the Developmental State in South Korea. Int. Organ. 2002, 56, 177–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olken, B.A.; Pande, R. Corruption in Developing Countries. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2012, 4, 479–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazekas, M.; Kocsis, G. Uncovering High-Level Corruption: Cross-National Objective Corruption Risk Indicators Using Public Procurement Data. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 2020, 50, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Levendis, J.; Scarcioffolo, A.R. The Efficient Corruption Hypothesis and the Dynamics between Economic Freedom, Corruption, and National Income. J. Dev. Areas 2020, 54, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosa, I.A. Good Regulation versus Bad Regulation. J. Bank. Regul. 2018, 19, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bac, M.; Kucuksenel, S. Two Types of Collusion in a Model of Hierarchical Agency. J. Inst. Theor. Econ. JITE 2006, 162, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strach, P.; Sullivan, K.; Pérez-Chiqués, E. The Garbage Problem: Corruption, Innovation, and Capacity in Four American Cities, 1890–1940. Stud. Am. Polit. Dev. 2019, 33, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P.; Uhlenbruck, K.; Eden, L. Government Corruption and the Entry Strategies of Multinationals. Acad. Manage. Rev. 2005, 30, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.C.; Shahid, M.S. Informal Entrepreneurship and Institutional Theory: Explaining the Varying Degrees of (in)Formalization of Entrepreneurs in Pakistan. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2016, 28, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.; Zurawicki, L. Corruption and Foreign Direct Investment. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2002, 33, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1995, 20, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammigan, I.; Linssen, R. Korruption als »Situational Action«. Eine Theoretisch-Integrative Erklärung Korrupten Verhaltens Auf Basis der »Situational Action Theory. Monatsschrift Kriminol. Strafrechtsreform 2012, 95, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Anand, V. The Normalization of Corruption in Organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 2003, 25, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, D. Extending the Process Model of Collective Corruption. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 107–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misangyi, V.F.; Weaver, G.R.; Elms, H. Ending Corruption: The Interplay Among Institutional Logics, Resources, and Institutional Entrepreneurs. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 750–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromme, M. What next for Anti-Corruption Research in Vietnam? Crime Law Soc. Change 2016, 65, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksynska, M.; Havrylchyk, O. FDI from the South: The Role of Institutional Distance and Natural Resources. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 2013, 29, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frynas, J.G.; Buur, L. The Presource Curse in Africa: Economic and Political Effects of Anticipating Natural Resource Revenues. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020, 7, 1257–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyimah-Brempong, K. Corruption, Economic Growth, and Income Inequality in Africa. Econ. Gov. 2002, 3, 183–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Davoodi, H.; Alonso-Terme, R. Does Corruption Affect Income Inequality and Poverty? Econ. Gov. 2002, 3, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, A.O. The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society. In 40 Years of Research on Rent Seeking 2; Congleton, R.D., Konrad, K.A., Hillman, A.L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 151–163. ISBN 978-3-540-79185-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lambsdorff, J.G. Corruption and Rent-Seeking. Public Choice 2002, 113, 97–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congleton, R.D.; Hillman, A.L.; Konrad, K.A. Forty Years of Research on Rent Seeking: An Overview. In 40 Years of Research on Rent Seeking 2; Congleton, R.D., Konrad, K.A., Hillman, A.L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 1–42. ISBN 978-3-540-79185-0. [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueti, R.; Coppier, R. Tax Revenues, Fiscal Corruption and “Shame” Costs. Econ. Model. 2009, 26, 1239–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonoyan, V.; Strohmeyer, R.; Habib, M.; Perlitz, M. Corruption and Entrepreneurship: How Formal and Informal Institutions Shape Small Firm Behavior in Transition and Mature Market Economies. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 803–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.P.; Sloan, S.; Weng, L.; Dirks, P.; Sayer, J.; Laurance, W.F. Mining and the African Environment. Conserv. Lett. 2014, 7, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H. Corruption, Growth, and the Environment: A Cross-Country Analysis. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2004, 9, 663–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroozi, B.; Rashidian, A.; Moradi, G.; Takian, A.; Ghasri, H.; Ghadimi, T. Out-of-Pocket and Informal Payment before and after the Health Transformation Plan in Iran: Evidence from Hospitals Located in Kurdistan, Iran. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2017, 6, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaal, P.; McKee, M. Fee-for-Service or Donation? Hungarian Perspectives on Informal Payment for Health Care. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 1445–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A.; Gugerty, M.K. Trust but Verify? Voluntary Regulation Programs in the Nonprofit Sector. Regul. Gov. 2010, 4, 22–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptein, M. Understanding Unethical Behavior by Unraveling Ethical Culture. Hum. Relat. 2011, 64, 843–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, G.R.; Trevino, L.K.; Cochran, P.L. Corporate Ethics Programs as Control Systems: Influences of Executive Commitment And Environmental Factors. Acad. Manage. J. 1999, 42, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Faccio, M. Politically Connected Firms. Am. Econ. Rev. 2006, 96, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisman, R. Estimating the Value of Political Connections. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwaja, A.I.; Mian, A. Do Lenders Favor Politically Connected Firms? Rent Provision in an Emerging Financial Market. Q. J. Econ. 2005, 120, 1371–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y. Mimetic Isomorphism, Market Competition, Perceived Benefit and Bribery of Firms in Transitional China. Aust. J. Manag. 2010, 35, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnuson, W. International Corporate Bribery and Unilateral Enforcement. Colum. J. Transnat’l L. 2012, 51, 360. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, R. Market and Political/Regulatory Perspectives on the Recent Accounting Scandals. J. Account. Res. 2009, 47, 277–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, S.M. A Perfect Moral Storm: Climate Change, Intergenerational Ethics and the Problem of Moral Corruption. Environ. Values 2006, 15, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfers, J. Point Shaving: Corruption in NCAA Basketball. Am. Econ. Rev. 2006, 96, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, J.P.; Depken, C.A., II; Gandar, J.M. Market Evidence against Widespread Point Shaving in College Basketball. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2018, 153, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.; Yang, A.Y.; Ganesh, A.; Sastry, S.S.; Ma, Y. Robust Face Recognition via Sparse Representation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2009, 31, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavetski, D.; Kuczera, G.; Franks, S.W. Bayesian Analysis of Input Uncertainty in Hydrological Modeling: 1. Theory. Water Resour. Res. 2006, 42, 2005WR004368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrow, C. The Organizational Context of Human Factors Engineering. Adm. Sci. Q. 1983, 28, 521–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrow, C. Normal Accidents: Living with High Risk Technologies-Updated Edition; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer, M.; Bascompte, J.; Brock, W.A.; Brovkin, V.; Carpenter, S.R.; Dakos, V.; Held, H.; Van Nes, E.H.; Rietkerk, M.; Sugihara, G. Early-Warning Signals for Critical Transitions. Nature 2009, 461, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Ackerman, S. Corruption: A Study in Political Economy; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; ISBN 1-4832-8906-0. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.K. Models of Corruption. In Economics of Corruption; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; pp. 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Nye, J.S. Corruption and Political Development: A Cost-Benefit Analysis. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1967, 61, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, N. Economic Development Through Bureaucratic Corruption. Am. Behav. Sci. 1964, 8, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Ackerman, S. Trust, Honesty and Corruption: Reflection on the State-Building Process. Arch. Eur. Sociol. J. Sociol. Arch. Soziol. 2001, 42, 526–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chayes, S. Thieves of State: Why Corruption Threatens Global Security; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, E.D. Criminal Enterprises and Governance in Latin America and the Caribbean; Cambridge University Press: Camberley, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, M. Redundancy, Rationality, and the Problem of Duplication and Overlap. Public Adm. Rev. 1969, 29, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, R.; Mahoney, J.T. Modularity, Flexibility, and Knowledge Management in Product and Organization Design. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldane, A.G.; May, R.M. Systemic Risk in Banking Ecosystems. Nature 2011, 469, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. The Architecture of Complexity. In The Roots of Logistics; Klaus, P., Müller, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 335–361. ISBN 978-3-642-27921-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-470-53423-6. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. A Sociological Theory of Law; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Simson, V.; Jennings, A. Dishonored Games: Corruption, Money & Greed at the Olympics; SP Books: Paris, France, 1992; ISBN 978-1-56171-199-4. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, D.S.; Thibault, L.; Misener, L. An Agency Theory Perspective on Corruption in Sport: The Case of the International Olympic Committee. J. Sport Manag. 2006, 20, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junghagen, S.; Aurvandil, M. Structural Susceptibility to Corruption in FIFA: A Social Network Analysis. Int. J. Sport Policy Polit. 2020, 12, 655–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frattini, E. ONU Historia de La Corrupción; Bubok Publishing S.L.: Madrid, Spain, 2009; ISBN 978-84-9916-371-0. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, J. Can Self Regulation Work?: A Story of Corruption, Impunity and Cover-Up. J. Regul. Econ. 2007, 31, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenbrunsel, A.E.; Messick, D.M. Ethical Fading: The Role of Self-Deception in Unethical Behavior. Soc. Justice Res. 2004, 17, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, V.; Ashforth, B.E.; Joshi, M. Business as Usual: The Acceptance and Perpetuation of Corruption in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2004, 18, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielke, R. How Can FIFA Be Held Accountable? Sport Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, A. The Dirty Game: Uncovering the Scandal at FIFA; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bayle, E.; Rayner, H. Sociology of a Scandal: The Emergence of ‘FIFAgate’. Soccer Soc. 2018, 19, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. Governance and Corruption in Public Health Care Systems. Cent. Glob. Dev. Work. Pap. 2006, 78, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugden, J.; Tomlinson, A. FIFA and the Contest for World Football; Polity Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 0-7456-1660-7. [Google Scholar]

- Sugden, J.; Tomlinson, A. Football, Corruption and Lies: Revisiting’Badfellas’, the Book FIFA Tried to Ban; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gibelman, M.; Gelman, S.R. A Loss of Credibility: Patterns of Wrongdoing among Nongovernmental Organizations. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2004, 15, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, R.; Owens, T. Promoting Transparency in the NGO Sector: Examining the Availability and Reliability of Self-Reported Data. World Dev. 2010, 38, 1263–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, M.; Carpenter, S.; Foley, J.A.; Folke, C.; Walker, B. Catastrophic Shifts in Ecosystems. Nature 2001, 413, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, B.; Salt, D. Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Spahn, E.K. Implementing Global Anti-Bribery Norms: From the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act to the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention to the UN Convention against Corruption. Ind. Intl. Comp. Rev. 2013, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, C. The Creation of a Review Mechanism for the UN Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime and Its Protocols. Am. J. Int. Law 2020, 114, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Lescano, A.; Teubner, G. Regime-Collisions: The Vain Search for Legal Unity in the Fragmentation of Global Law. Mich. J. Int. Law 2003, 25, 999–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Teubner Self-Constitutionalizing TNCs? On the Linkage of “Private” and “Public” Corporate Codes of Conduct. Indiana J. Glob. Leg. Stud. 2011, 18, 617. [CrossRef]

- Teubner, G. Constitutional Fragments: Societal Constitutionalism and Globalization; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Belmar, F.; Mascareño, A. Corruption: An Uneven Field of Research—Between State and Private Topics. Societies 2025, 15, 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070186

Belmar F, Mascareño A. Corruption: An Uneven Field of Research—Between State and Private Topics. Societies. 2025; 15(7):186. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070186

Chicago/Turabian StyleBelmar, Fabián, and Aldo Mascareño. 2025. "Corruption: An Uneven Field of Research—Between State and Private Topics" Societies 15, no. 7: 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070186

APA StyleBelmar, F., & Mascareño, A. (2025). Corruption: An Uneven Field of Research—Between State and Private Topics. Societies, 15(7), 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070186