1. Introduction

The world faces an environmental crisis characterized by increasing global temperatures, more frequent extreme weather events, and a considerable decline in biodiversity [

1,

2]. Urgent global action is needed to mitigate these effects and transition toward sustainable practices. One approach to accomplish this goal is to provide education focused on the environment and sustainability. Education is pivotal in addressing the environmental crisis because it influences individuals to think critically about issues such as resource use, pollution, and energy conservation, as well as modify behaviors that lead to environmental degradation [

3,

4].

Environmental and sustainability education in the United States has historically focused on primary, secondary, and post-secondary students. Many K-12 educational systems incorporate these issues into art, science, and social studies curricula to create a fundamental understanding of the environment and sustainability [

5,

6,

7]. College programs inside and outside the classroom have also gained traction in recent years, providing students with the coursework and experience necessary to evaluate environmental problems and solutions [

8,

9,

10]. Given their roles as future employers and policymakers, the focus on traditional students is understandable [

11]. However, this narrow approach overlooks the immediate impact individuals outside schools and universities can have on environmental policies and practices [

4]. With their ability to vote, organize, and influence public policy and cultural norms, adult learners are uniquely positioned to drive immediate and large-scale changes in environmental behavior, often having a more direct impact than students still in training [

12]. However, accessible, low-barrier opportunities for these learners remain under-researched and underdeveloped [

13,

14].

To date, much of the existing literature on environmental and sustainability education continues to focus on K-12 and university students, with less emphasis on adult environmental education (AEE) [

5,

6,

15]. Despite this trend, a body of research regarding AEE has emerged. Beginning in the 1970s, environmental leaders in the field advocated for structured and ongoing educational programs designed specifically for adults. Advocates for such programs contended that they would have a more enduring effect on individual learning and community-wide environmental initiatives [

16,

17,

18]. Eventually, the orientation of the field changed, emphasizing sustainable development and increased citizen engagement [

4]. By the 1990s, scholars began to argue that AEE should empower adults to become active change agents in their communities, shifting from earlier models focused primarily on knowledge transfer [

17].

In recent years, both scholars and practitioners have concentrated on integrating environmental education with adult learning theories, as well as on the development and application of conceptual frameworks and overarching philosophies within AEE [

17,

19]. The employment of transformative and participatory learning strategies emerged as a particular area of focus in the research. Scholars identified these approaches as crucial in fostering meaningful, action-oriented learning that empowers individuals and communities to address environmental challenges.

In the context of AEE, transformative learning highlights the importance of learners evaluating their values, beliefs, and assumptions regarding the environment and society. This approach calls for learners to shift how they perceive environmental issues while also spurring action to address environmental problems [

20]. Participatory approaches focus on engaging learners through activities and experiences while promoting shared learning [

17]. Specifically, participatory learning relies on action research, workshops, and community-driven environmental projects involving adults in addressing environmental challenges [

21]. Both methods aim to empower learners to take significant action within their communities.

Additionally, there is a growing focus on providing environmental and sustainability education in informal settings, specifically tailored to the unique needs of the communities they serve [

13,

14,

22]. This approach recognizes the importance of customizing environmental education to make it more relevant and impactful for adult learners. Simultaneously, researchers have questioned the exclusion of vulnerable and marginalized communities from existing environmental education initiatives [

13]. As a result, efforts are being made to design and implement AEE programs that are more inclusive and accessible, addressing the unique challenges and perspectives of underserved populations [

19]. The shift towards community-centered, inclusive AEE is crucial for fostering widespread environmental awareness and action across diverse societal groups [

23,

24].

Despite the growing body of research on AEE and a significant shift toward equitable engagement, few studies examine who participates in AEE programs or whether participants remain engaged over time. While the literature on program outcomes, such as increased awareness of environmental issues and enhanced content knowledge, is extensive, fewer studies examine participation rates, participant characteristics, program engagement, or consistency in participation [

5,

25]. Research on agricultural extension programs offers some insights into audience types and engagement levels within audience segments, but there is limited exploration of these trends in the broader AEE context [

26,

27]. Understanding participants’ backgrounds, how many individuals attend programs on average, and which modalities (e.g., online or in-person) prove more effective all inform program design and impact program success.

This descriptive study addresses the gap in the literature by reviewing programs conducted by a policy and research center at a small liberal arts college in southwestern Pennsylvania, a region with considerable mineral resource extraction activities. The events, which feature experts in the field who discuss various topics related to energy and sustainability, are free and open to the public, with some programs hosted in person and others online. The study analyzed archival, secondary data to describe participation based on event format (in-person or online) and program topic (general interest or high regional impact). Furthermore, the study investigated the sectoral affiliation of attendees (governmental, nonprofit, private citizen, etc.) and the frequency of repeat participation in these events.

The study found that between January 2021, when the program offerings began, and March 2025, the most recent event offered, the organization conducted 23 events with 1478 attendees, an average of approximately 64 participants per event. Of the participants, 68 percent were business leaders or private citizens, and another 12 percent and 11 percent came from academia and nonprofit organizations, respectively. Government officials and representatives from K-12 organizations constituted approximately 9 percent of attendees. In addition, 174 individuals (approximately 11 percent) joined in multiple events since 2021, showing continued engagement amongst a segment of participants.

The Center’s events covered various topics, including solar projects collocated with agricultural activity (agrisolar), decarbonization efforts, and hydrogen energy development. Despite the increasing prevalence of online programming, the in-person events were some of the best-attended, as were programs focused on topics with high regional significance and cutting-edge technologies. For example, the events focusing on hydrogen energy and carbon capture, held at the height of the US Department of Energy’s hydrogen hub funding opportunity (which, if awarded, would have significantly impacted the region), received high levels of interest. As evidenced by the diversity of attendees and the variety of topics covered, demand for education that empowers adults to engage with environmental and sustainability issues exists.

Based on the findings, the researcher contends that low- or no-cost AEE programs, which cater to community and regional needs and interests through online and in-person formats, can achieve success. These programs can engage diverse learners and maintain interest over time. The researcher further contends that colleges and universities are particularly well-suited to implement such programs due to their organizational strengths, prominent role within the community, and capacity to attract distinguished speakers.

This study advances the literature on AEE by providing much-needed quantitative insights into participation patterns, an area largely overlooked in previous research. While existing studies have focused on the philosophies, pedagogies, and outcomes of AEE, there has been limited exploration of who participates in these programs and how their engagement changes over time. By analyzing real-world participation data from a series of free, public-facing events, this study sheds light on key demographic trends, including sector affiliation and regional relevance of topics.

2. Materials and Methods

This study examined archival registration data from 23 public seminars organized by a policy and research center in southwestern Pennsylvania from January 2021 to March 2025. Using the data, the researcher calculated average attendance rates, compared registrations for online and in-person programs, examined sector affiliation of participants, and identified the percentage of individuals who participated in multiple programs. Subsequent sections provide an overview of the Center and its activities, along with specific materials, data collection methods, and descriptive approaches employed in the research study.

2.1. The Center and Its Activities

The Center for Energy Policy and Management (CEPM) is a part of Washington & Jefferson College, a private liberal arts institution of about 1400 undergraduate students in southwestern Pennsylvania. Formed in 2012 amidst the region’s shale gas boom, the Center was charged with providing credible information to the community on the region’s most pressing energy and environmental issues. The Center, which is fully supported by external grants, has three full-time staff members and several student research fellows, with the number of employed students varying from semester to semester. The staff and students conduct research, publish a weekly newsletter about energy and environmental issues in the region, and facilitate on-campus energy projects (e.g., oversee EV charging stations, dormitory activities related to energy and the environment, etc.).

Each academic year, beginning in 2021, the Center holds free and open-to-the-public programs focused on current and emerging issues related to energy and sustainability. The events are held during the day, primarily online via Zoom, though the Center has hosted in-person conferences at the college once each of the last three years. The programs typically feature one to three speakers who are experts on a particular topic. These speakers work for state and federal government agencies, private firms, and nonprofits specializing in energy and environmental issues. The speakers share their knowledge and insights during the programs through presentations, panel discussions, and interactive Q&A sessions. Attendees can engage directly with these experts, asking questions throughout the program. The events cover various topics, including renewable energy technologies, energy efficiency strategies, and environmental policy developments. The topics are based on current events, emerging trends identified by the staff, and the availability of speakers.

Event attendees were solicited via email and social media platforms, including Facebook and LinkedIn. Visitors to the Center’s website can also find information and register for the programs. Registration is managed through the event platform Eventbrite, which allows users to browse and register for programs by time, topic, and geographic area. Eventbrite sends participants periodic reminders about the programs.

2.2. Data Collection and Organization

The primary data for this analysis were sourced from the archival registration records of all 23 public seminars organized by the Center for Energy Policy and Management. These seminars were conducted both online as webinars and in person. The participant data included registration IDs and email address domains, with specific email addresses de-identified. Since the data were collected for administrative and logistical purposes related to event registration and were anonymized before analysis, the research did not require Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval.

For analysis, the participant data for separate events were first organized into a structured dataset. Each seminar was categorized by event type (online or in-person) and the regional significance of the topics covered (i.e., local versus more general/global relevance). The sector affiliation data for participants were divided into five main categories: academia, business leaders and private citizens, government representatives (federal, state, and local), K-12 professionals, and nonprofit organizations. Participants were classified based on the domain of the email address used for registration on Eventbrite. For instance, attendees with a “.edu” email were identified as academic participants, while those with “pa.gov” were classified as government participants. Although using email domains helped identify general trends, it was not a perfect indicator, as misclassification of emails was possible, especially for those associated with more common domains, such as “gmail.com”.

2.3. Data Analysis

The analysis of participant data for this study sought to uncover patterns and insights related to the demographics and participation trends in the public seminars hosted by the Center from January 2021 to March 2025. This analysis serves as a foundation for understanding the reach of the Center’s educational initiatives among adult populations. Descriptive statistics were calculated to offer an overview of participant demographics and attendance trends. The total number of attendees for each seminar was recorded, and the average attendance per event was determined. Additionally, the breakdown of participants by sector affiliation was examined, focusing on the distribution of attendees across various categories.

The researcher compared registration rates between in-person and online programs. In addition, the regional relevance of the seminar topics was assessed by comparing attendance rates for events centered on local issues with those addressing broader subjects. These topics were categorized based on the event’s topic and timing. For instance, the webinar titled “First in the World: An Airport That Generates Its Own Power,” which discussed the Pittsburgh International Airport’s use of natural gas and solar panels, was classified as having “regional importance.” In contrast, events that offered a general overview of EV charging stations were not given this designation. The process of categorizing the events was subjective but validated by external reviewers in the region.

Due to the interdependence of the events and the substantial number of participants who registered for multiple sessions, the data analysis was limited to a descriptive methodology. This overlap in participant attendance introduced potential dependencies among the events, making the use of some statistical techniques inappropriate. In other words, because participants may have attended multiple events, the dataset includes repeated measures, which violates the independence assumption of some statistical tests. Consequently, the study delivered a detailed and comprehensive data description, emphasizing trends, patterns, and key observations across various events. This descriptive approach facilitated a clearer understanding of the overall trends within the dataset while acknowledging the limitations imposed by the non-independence of events and participant overlap.

Utilizing the Center’s activities for this analysis was appropriate because the programming exemplified several themes prevalent in the AEE literature. By providing free and accessible programs, the Center promotes inclusive education, a core tenet of AEE that seeks to engage a wide array of adult learners, especially those without access to formal education [

22,

28,

29]. The events’ hybrid format, mainly online with some in-person gatherings, also reflects the AEE trend of creating adaptable learning environments that cater to different learning preferences and geographical areas [

4,

11,

25]. The programs’ interactive elements, such as Q&A sessions, underscore the literature’s support for participatory methods in AEE, which empower adult learners and enable them to contribute to sustainable solutions. Additionally, the Center’s focus on current energy and sustainability issues aligns with AEE’s move towards addressing immediate socio-ecological challenges. Given this intersection, the programs offer a valuable opportunity to observe AEE in practice and to evaluate participation and engagement rather than focusing solely on outcomes.

3. Results

This study analyzed participant data from 23 public seminars organized by the Center for Energy Policy and Management at Washington & Jefferson College between January 2021 and March 2025. The events received 7469 page views and 1478 participants, a conversion rate of 19.8 percent. The average number of participants was approximately 64 individuals. The minimum and maximum were 17 and 116 participants, respectively. The primary objective of this analysis was to investigate participation patterns, the influence of program topic on participation, the sector affiliation of participants, and continued engagement.

3.1. Event Format, Topic, and Attendance

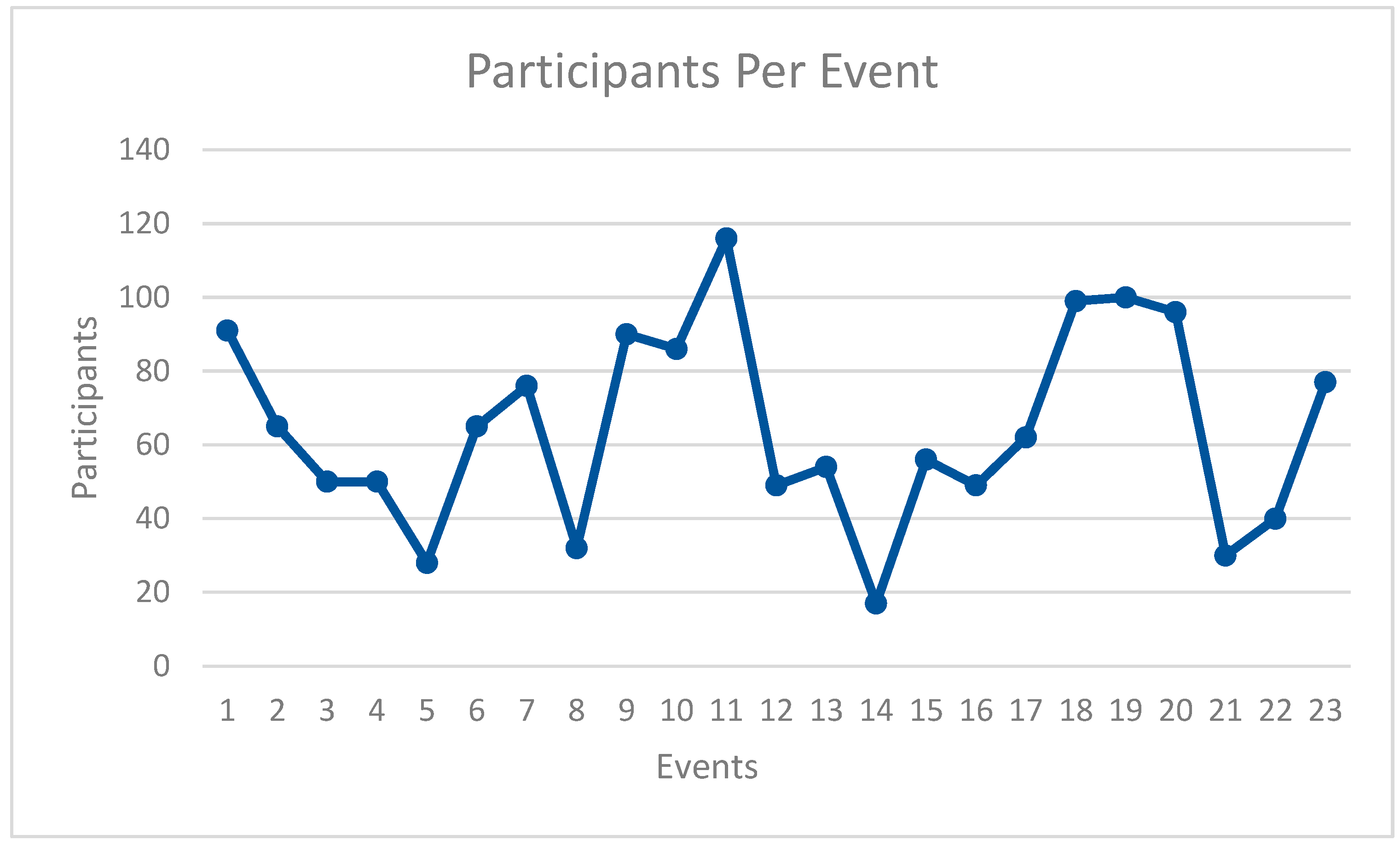

The analysis of event attendance revealed notable differences between in-person and online events as well as differences in attendance based on topic. Each event is listed in the

Table 1 below, including the title/topic, regional nature of the topic (shown as ‘y’ for yes and ‘n’ for no), type, date, participant total, and page views for the program on EventBrite.

While more individuals attended online programs overall, the average attendance rate of in-person programs was higher. On average, in-person events attracted approximately 104 participants, reflecting strong engagement in face-to-face settings. In contrast, online events yielded a lower average attendance, with about 58 participants per session. This disparity in attendance may suggest varying levels of engagement and interest depending on the mode of delivery, with in-person events drawing a larger crowd.

Events such as “Shedding Light on Energy Efficiency: Streetlight Procurement” (February 2023) had a relatively low level of engagement, with only 17 participants and 114 page views, indicating that more specialized topics may attract limited interest. In contrast, subjects centered on advanced technologies, such as “Hydrogen” and “Clean Hydropower,” elicited greater interest, evidenced by higher attendance and page views in both in-person and online formats. Additionally, topics related to corporate issues, exemplified by “Corporate Responsibility in the Natural Gas Industry” (January 2021), achieved substantial attendance (91 participants) and significant page views (300), suggesting an increasing interest in corporate environmental responsibility within the energy sector.

Analyzing participation over time supports the importance of the program topic in participation levels. As shown in

Figure 1, no significant loss or gain in involvement over time is observed. This suggests that the topic impacts interest and participation rather than a general growth or decline in programming.

3.2. Influence of Regional Relevance on Attendance

Of the 23 seminars conducted during the study period, 13 events were categorized as addressing topics of lower regional priority or general interest, with 651 participants across these events. In contrast, the 10 events focused on higher regional priority topics, such as local energy initiatives or region-specific environmental challenges, attracted 827 participants. The difference in registrations suggests that participants were more inclined to attend seminars addressing issues with clear, local relevance. Higher attendance at events with regional significance supports the notion that local issues drive greater interest and engagement in environmental and sustainability education.

3.3. Sector Affiliation of Participants

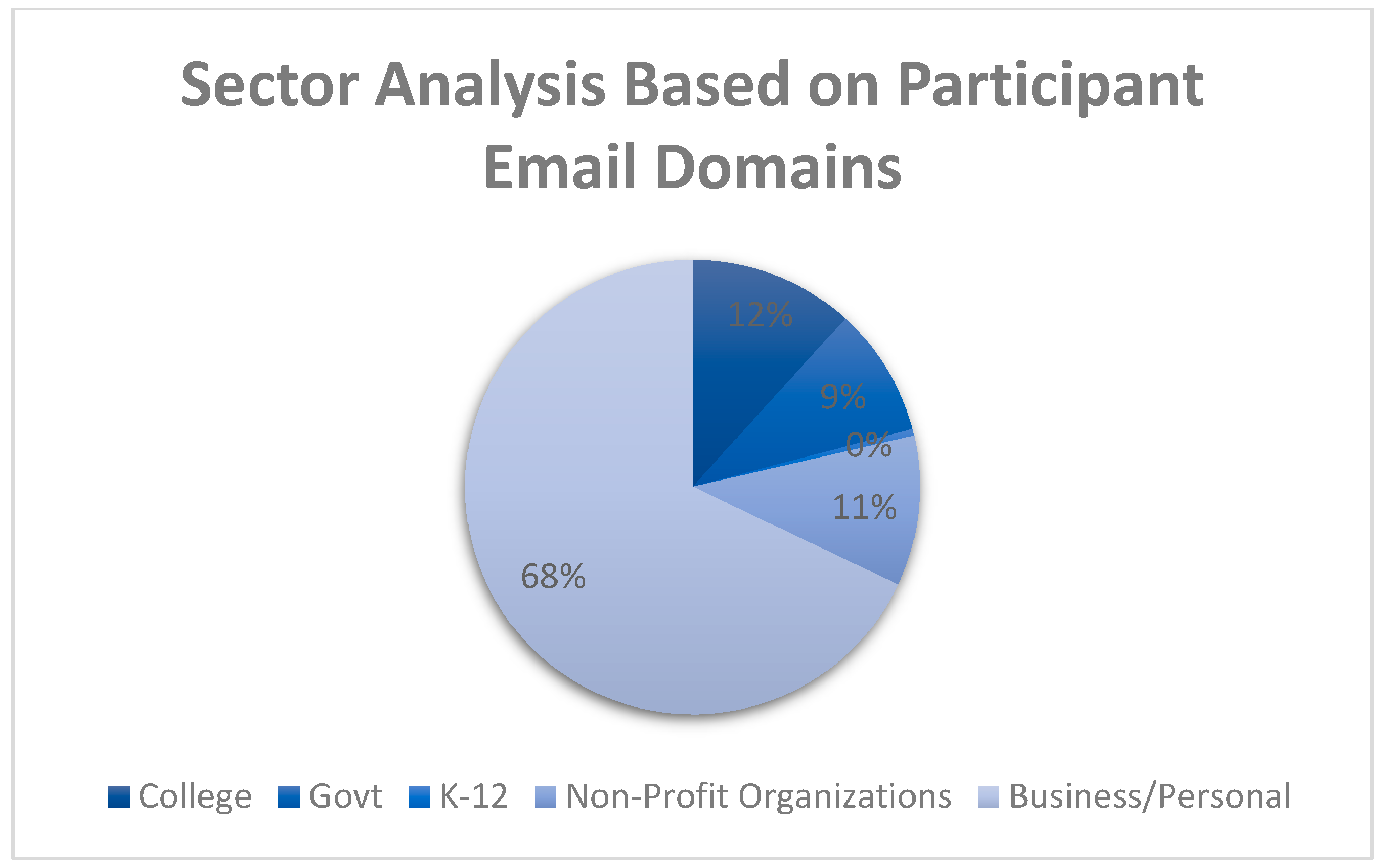

Examining the sector affiliation of seminar attendees revealed the diversity of individuals engaging with sustainability topics. A majority of participants, 68 percent, were private citizens or affiliated with business organizations (

Figure 2). A review of the email domains suggests that attorneys, consultants, and individual citizens participated in the programs offered. The large proportion indicates that environmental and sustainability issues are of significant concern to individuals in the private sector and the public, who are likely motivated by personal or professional interests in sustainability practices. Such a trend is understandable given the regional context of the Center. Working professionals in the area often have clients tied to energy development projects, while private citizens live near or are impacted by energy production, transmission, or distribution.

Faculty, staff, and students from inside and outside Washington & Jefferson College represented 12 percent of the participants. While individuals from the College occasionally attended programs offered by the Center, individuals from other institutions also participated in the programs. Online programs were particularly popular among faculty, staff, and students at other institutions.

At the same time, nonprofit organizations, which often focus on environmental advocacy and social justice, comprised 11 percent of participants. These organizations were typically regionally or state-based. Further review indicated they were likely to attend both in-person and online programs regularly.

The 9 percent representation from government agencies suggests a moderate level of interest from public sector employees, likely driven by policy considerations related to sustainability and environmental governance. While some of the governmental participants worked at state-level organizations, the majority worked in local government at the borough, township, and county levels.

Notably, K-12 representatives accounted for less than 1 percent of the participants, highlighting the limited involvement of K-12 students and educators in these community, adult-oriented seminars. The lack of participation among K-12 community members potentially signals a lack of awareness or salience of the topics covered in the programs in that community. Additionally, the perceived technical complexity of some of the topics may have dissuaded K-12 representatives from participating.

3.4. Repeated Attendance and Engagement

The analysis also revealed patterns of repeated engagement among program participants. A total of 174 individuals (approximately 12 percent of all registrations) attended more than one seminar during the study period, indicating a sustained interest in the topics presented. More than 90 percent of repeat attendees came from outside the College. On average, these individuals attended 3.12 programs, with a median of 2.0 programs. The relatively low median (2.0) compared to the mean (3.12) suggests a skew in participation, where a few individuals attended significantly more seminars than the rest.

The higher engagement levels observed among repeat attendees emphasize the importance of creating opportunities for continued learning within AEE programs. Participants who return for multiple sessions may be more invested in building their knowledge on sustainability issues and, therefore, could be ideal targets for more advanced or specialized content. Furthermore, repeated attendance could provide opportunities for more in-depth discussions on some sustainability issues.

4. Discussion

This study analyzes attendance trends, sectoral representation, and the regional significance of sustainability for free in-person and online seminars. Although this study does not focus on pedagogical methods or educational outcomes, it provides critical insights into engagement for environmental education initiatives. Understanding the engagement patterns of individuals from different sectors with sustainability programming lays the foundation for developing more inclusive and accessible AEE initiatives. The findings also illuminate the impact of online platforms in broadening access to education and the role of in-person events in fostering deeper community connections.

4.1. Event Type and Mode of Delivery

The research showed differences in attendance rates between in-person and virtual events, with the programs averaging 104 and 58 participants, respectively. The higher rates observed for in-person events indicate that participants may find more value in personal interactions and the chance to engage directly with instructors, peers, and local environmental specialists. Past research comparing online and in-person instruction has shown mixed results. Some studies examining performance in online learning environments found online formats to be more effective, with higher student performance, while others reported better outcomes for in-person instruction [

30,

31]. The gap observed in the present study is consistent with research highlighting the advantages of community-focused, face-to-face learning for environmental education programs [

23,

32,

33].

The relatively low registration rates for online events prompt questions about the influence of virtual platforms on participation in AEE. Although online learning provides accessibility and flexibility, especially for adult learners with hectic schedules or those residing in remote locations, it might not offer the same degree of personal interaction and active discussion as in-person learning. This observation aligns with criticisms of virtual learning environments, which argue that they may not fully engage learners in meaningful, participatory ways [

34,

35]. The decreased attendance at online events might also highlight the difficulties of sustaining engagement in virtual settings, where distractions and the absence of social interaction could hinder the transformative learning experience.

4.2. Significance of Topics

The research revealed that the program topic played a significant role in determining participation and influenced engagement in two important ways. First, niche topics that were more specialized or technical tended to attract fewer participants. Topics like energy efficiency considerations for streetlight procurement or the impacts of EVs on state budgets proved less popular, both in terms of page views and actual participation. While valuable in addressing specific sustainability issues, these topics did not attract the same level of interest as broader or more “cutting-edge” themes, such as renewable natural gas or agrisolar projects.

Second, the regional significance of the topics proved to be an influential factor in registrations. Programs that addressed issues directly relevant to the local community or regional concerns saw higher interest. For example, the programs focused on carbon capture and hydrogen energy development received more interest than global or general interest topics, like the energy impacts of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. As highlighted in the literature review, AEE programs should address the specific issues and concerns of the communities they aim to serve, incorporating both global and local environmental issues into the educational process [

13,

23,

24,

36]. These findings comport with the literature’s emphasis on context-specific learning that connects to participants’ real-life experiences [

20,

37,

38].

4.3. Sector Affiliation and Community Engagement

A substantial majority of the participants, 67.9 percent, came from businesses and private citizens. In contrast, academia accounted for 11.7 percent of participants, while governments contributed 9.2 percent, and nonprofits and NGOs made up 10.7 percent. Only 5 percent of participants came from K-12 educational entities. These figures offer valuable insights into the engagement patterns of various sectors and highlight the interest level of private citizens and businesses.

The active participation of private citizens in the AEE events reflects the growing importance of encouraging personal accountability and community-focused initiatives in sustainability education. This is consistent with the transformative learning framework in the literature, which stresses the need for nurturing a sense of agency and drive to address environmental challenges [

16,

39,

40]. As the literature points out, individuals can play a key role in advancing sustainability efforts at the grassroots level [

33,

41,

42]. They actively pursue opportunities to expand their knowledge and participate in meaningful environmental activities. This aligns with the “lifelong learning” concept in sustainability education, which extends from birth to death and aims to promote ongoing awareness and action throughout one’s life [

4,

22,

43].

The engagement of business stakeholders is also significant, as the AEE literature frequently highlights the private sector’s dual role as both a challenge and an opportunity in sustainability education [

44]. Initially, AEE research focused on the contributions of community-based and non-governmental organizations in promoting environmental learning [

45,

46]. However, recent developments have increasingly recognized the critical role of businesses in advancing sustainability. Wals et al. (2017) note a growing consensus that companies should be integrated into the sustainability education framework as contributors to and mitigators of environmental harm. In this context, the participation of business professionals in these events presents an opportunity for AEE to impact corporate decision-making and encourage a transition towards more sustainable business practices [

4].

4.4. Repeat Attendance and Engagement

The study also highlighted the relatively frequent return of participants, indicating a strong engagement with the educational programs offered. The repeated involvement in AEE events implies that participants may perceive these gatherings as essential venues for continuous reflection, discussion, and personal development concerning environmental matters. This pattern is significant in sustainability education, where continued involvement is crucial to developing the comprehensive understanding and dedication needed to effect substantial change [

46,

47].

The focus on repeated attendance in AEE underscores the notion that environmental education should go beyond merely increasing awareness of environmental issues; it should also aim to foster ongoing involvement and action. Educational approaches that motivate participants to attend multiple events, potentially addressing various facets of sustainability, are more likely to result in enduring shifts in attitudes, behaviors, and practices. Furthermore, repeated participation could strengthen community bonds, encouraging participants to engage in collective action, a central goal in transformative AEE practices.

4.5. Low-Barrier Educational Opportunities for AEE

The events analyzed in this study exemplify low-barrier AEE opportunities or events with minimal entry requirements. The events hosted by the Center were free of charge, open to the public, and offered online and in person. These characteristics enabled participants with financial or geographic constraints to participate. Furthermore, these events typically lasted one to three hours, making attendance feasible for busy adults compared to more traditional, comprehensive educational programs.

Removing barriers to participation is essential for engaging diverse groups of adults, particularly those who may not have the time, resources, or inclination to participate in more traditional, formal education settings [

16,

38,

41]. These low-barrier events also help diversify audiences, ensuring that environmental education is not confined to a specific group but reaches a wide range of stakeholders. These low-barrier opportunities align with the growing emphasis in the AEE literature on the importance of accessibility and inclusivity in fostering pro-environmental behavior, as they create entry points for adult learners to engage with complex sustainability issues [

15].

4.6. The Role of Colleges and Universities in AEE

The present study highlights the role colleges and universities can play in AEE. Given their financial and organizational resources as well as their established ties within local communities and regions, colleges and universities are uniquely positioned to offer low-barrier AEE events. Higher educational institutions generally have the financial and organizational infrastructure needed to effectively plan and execute a range of educational programs aimed at adult learners. Their extensive experience in event management, including coordinating lectures, conferences, workshops, and seminars, allows them to host large-scale educational events that can engage a broad and diverse audience. Furthermore, they can utilize their established communication platforms, including websites, newsletters, and email lists, to promote events and attract participants from various backgrounds.

In addition to their organizational strengths, colleges and universities have better access to high-quality speakers who are experts in the field. Faculty members, researchers, and other professionals affiliated with universities can provide attendees with new perspectives and insights into emerging trends. Universities can tap into external networks outside the institution, drawing in professionals from government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and private sector companies. Since universities are often deeply embedded in the regions in which they are located, they can tailor programming to address specific local environmental challenges and concerns. The combination of strong organizational skills, access to a network of skilled professionals, and their capacity to address local environmental challenges uniquely positions colleges and universities as pivotal contributors to the expansion of AEE.

The findings of the study and the strengths of colleges and universities outlined here support the idea of universities as “conveners” for their communities [

48]. Past research contends that higher education institutions can serve as community anchors that foster social, economic, and technological development [

49]. The work of the Center in offering the programs fits squarely within that role and supports knowledge gain and increased awareness of environmental and sustainability issues among participants.

4.7. Advancing the Literature

This research adds to the AEE literature by examining participation and engagement trends. Most research on AEE emphasizes pedagogical methods, philosophies, and program outcomes, while giving less attention to the audiences attending such events. Consequently, a limited understanding exists of who participates in environmental education, what influences their involvement, and how different program types might attract specific adult groups. This study demonstrates that individual citizens and businesses are highly engaged in learning about the environment and sustainability by examining participation patterns, especially regarding sector affiliation (such as businesses, government, academia), event format (online versus in-person), and topic preferences. Furthermore, in-person programs remain highly popular even after the shift to online learning post-COVID-19. Finally, emerging energy topics and regionally salient topics prove highly popular.

4.8. Limitations of the Study

While the study offers valuable insights, there are several limitations. First, using digital technologies for gathering data and conducting seminars may introduce selection bias. Although online seminars can reach a wider audience, they tend to attract individuals who are already comfortable with digital platforms or have access to stable internet connections. Utilizing digital registration platforms may exclude certain demographic groups, especially those from lower socio-economic backgrounds or rural areas with limited internet access. Furthermore, the digital approach to data collection, which involved monitoring online registration and attendance, did not yield data regarding the reasons for attendance or participants’ learning outcomes.

Another limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size of in-person events (311 attendees) compared to online seminars (1167 attendees). The skew in the number of participants between the two formats may not fully reflect broader trends in adult learning preferences or sectoral participation. Future studies should aim to balance the data by including a more diverse range of in-person events and exploring the nuances of engagement in both online and face-to-face settings.

Finally, given the Center’s location in a region with past and current mineral resource extraction activities and energy production, greater interest in energy, the environment, and sustainability is possible. As a result, engagement with these issues may naturally be stronger, particularly for concerned citizens and working professionals. Therefore, data from additional programs in other locations would prove helpful and highlight emerging trends in AEE.

5. Conclusions

This study analyzed the engagement patterns, sectoral involvement, and regional significance of AEE seminars organized by a policy and research center in southwestern Pennsylvania from January 2021 to March 2025. The findings highlighted several key trends that add to the literature examining adult participation in AEE. Notably, in-person programs were more popular than online events when comparing registration averages. In addition, seminars with high regional significance experienced higher attendance, indicating that content directly relevant to participants’ lives fosters greater engagement.

The sectoral analysis of participants showed that business leaders and private citizens constituted the largest group of attendees (68%), followed by academics (12%), nonprofit professionals (11%), and government representatives (9%). K-12 educators accounted for less than 1% of the participants. The study also found a high level of continued engagement, with 174 individuals attending more than one seminar. On average, repeat attendees participated in 3.12 programs. Continued engagement is critical for AEE programs, which strive to educate and empower citizens through ongoing educational opportunities.

This research makes a substantial contribution to the field of AEE by presenting quantitative data on participation patterns in AEE programs. While much of the current AEE research has concentrated on qualitative insights or theoretical discussions, this study addresses a gap by supplying quantitative data on adult participation patterns, which is crucial for crafting more focused and effective educational strategies. Additionally, the findings support transformative and participatory learning frameworks and research focused on equity and context-specific content for AEE programs.

In the future, researchers should build upon the study’s findings by exploring the motivations for participation in specific sectors and the factors contributing to repeated attendance. A more comprehensive analysis of the efficacy of various event formats, in-person or online, could also prove helpful and enable educators to tailor AEE programs to diverse audiences more effectively. Finally, longitudinal studies could also provide valuable insights into the long-term impacts of AEE on behavioral changes and community engagement in sustainability initiatives.