Abstract

This article presents an integrative review of the role of the 7S-Based Feeding framework (Healthy, Sustainable, Safe, Social, Sovereign, Solidary, and Satisfactory) and its relationship with the One Health approach and human development in Latin America. Through an analysis of 18 articles selected via the PRISMA methodology and coded using ATLAS.ti, thematic patterns and analytical gaps were identified using Sankey diagrams and qualitative content analysis. The results indicate that the dimensions most frequently addressed were Sustainable, Healthy, Safe, and Social. In contrast, the Sovereign and Solidarity-based dimensions were underrepresented, while the Satisfactory dimension was entirely absent. Only one-third of the articles explicitly applied the One Health framework. The study proposes a theoretical integration of these approaches to enhance the understanding of food systems as determinants of well-being. It concludes that incorporating the 7S-Based Feeding framework into public food policies could strengthen their impact on equity, health, and resilience in Latin American communities.

1. Introduction

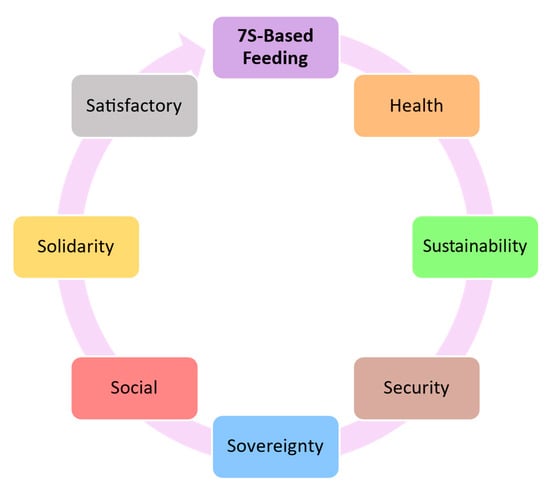

In recent years, the debate on food systems has gained momentum as a priority in the global health, sustainability, and human development agenda. Food crises, climate change impacts, persistent nutritional insecurity, and inequalities in access to healthy foods underscore the need for integrative approaches that link multiple dimensions of human well-being. From this perspective, the 7S-Based Feeding framework emerges as a conceptual model that unites seven key dimensions.

Figure 1 was created by the authors to visually represent the 7S-Based Feeding framework in English, originally introduced in Spanish by Urrialde de Andrés ([1], pp. 31–35). The illustration is based on the conceptual model proposed by the author.

Figure 1.

Key dimensions comprising the 7S-Based Feeding framework.

According to Urrialde de Andrés ([1], pp. 31–35), this approach seeks to reorient the current food paradigm toward a multidimensional, ethical, and systemic perspective aligned with One Health principles. Within this framework, feeding is not limited to individual nutrition or caloric intake but is understood as a process deeply interconnected with public health, environmental sustainability, social justice, and cultural self-determination.

Thus, the 7S-Based Feeding model expands the analysis to include aspects that remain underrepresented in public policies, such as food sovereignty, solidarity-based cooperation in food production and distribution, and the cultural pleasure of eating. Although these dimensions have been addressed independently in the scientific literature, a unified approach integrating them into a holistic model for human development and public health has yet to be consolidated [2].

The need for food system transformation is supported by numerous studies demonstrating strong links between dietary patterns, structural inequalities, and health outcomes. For instance, child malnutrition continues to disproportionately affect indigenous and rural communities in Latin America [3,4] while overweight and obesity coexist with nutritional deficits in countries like El Salvador and Bolivia [5,6]. Simultaneously, factors such as food inflation [7], food insecurity [8], and exposure to contradictory nutritional information [9] have intensified challenges to achieving healthy and sustainable diets across the region.

Despite emerging consensus on the urgency of transforming food systems, the scientific literature presents contrasting perspectives on the direction and depth of such changes. On one hand, studies advocate for agroecology-based models, local production, and community empowerment as effective strategies to improve nutritional health and sustainability [10,11]. These studies argue that traditional agricultural practices, combined with ancestral knowledge and social participation, generate positive impacts on both physical well-being and territorial development.

On the other hand, the relationship between feeding and human development has been extensively studied across disciplines, integrating health, economics, politics, and sustainability [12]. In this context, the One Health approach has gained prominence by recognizing the interdependence of human, animal, and environmental health as foundational pillars for food safety and population well-being [13].

In Latin America, a region characterized by significant ecological and socioeconomic diversity, public health and feeding challenges have been exacerbated by poverty, climate change, and unequal access to healthy and sustainable foods [14]. Zoonotic diseases, malnutrition, and recurring health crises have highlighted the need for integrated approaches addressing feeding from a holistic perspective [15].

The One Health approach has garnered significant attention in recent years for its capacity to address complex interconnections between human, animal, and environmental health. In contrast, the 7S-Based Feeding framework—composed of seven interdependent dimensions: Healthy, Sustainable, Safe, Social, Sovereign, Solidary, and Satisfactory—is a more recent conceptual proposal. Originally introduced in Spanish by Urrialde de Andrés ([1], pp. 31–35), it is an emerging conceptual model as a response to growing calls for integrative models that go beyond traditional views of food systems.

While the framework has not yet been widely debated in the academic literature, it presents a promising basis for further research, especially in connection with public health and sustainable development. This article represents the first scholarly attempt to cite, translate, and apply this framework in English-language academic literature, aiming to explore its potential intersections with One Health and human development in Latin America.

Some proponents argue that food safety and human health cannot be separated from environmental and animal well-being [12]. In Latin America, where inequalities in access to food and health services are pronounced, the One Health approach offers a comprehensive model to address these challenges [13].

Conversely, several authors question One Health’s effectiveness, arguing that its implementation faces multiple barriers in Latin America. According to Mueller [16], One Health remains largely theoretical and lacks practical application in regional public policies. Political unwillingness and fragmented health systems hinder its adoption. Furthermore, Hakizimana et al. [17] contend that One Health-based strategies may favor large agricultural and pharmaceutical industries, disadvantaging small producers and rural communities. Finally, Korsnes et al. [18] argue that structural inequalities in Latin America impede the implementation of transdisciplinary approaches like One Health, as they require collaboration and systemic economic efforts that are often unfeasible in the region.

While integrated approaches like One Health and emerging frameworks such as 7S-Based Feeding hold potential to address food security and reduce social inequalities, their implementation often encounters structural limitations. Several authors emphasize the transformative capacity of participatory food policies and sovereignty-oriented models [19,20], while others point to persistent political and institutional barriers that hinder their systemic adoption, especially in Latin American contexts [21]. These tensions reflect the need for further empirical research and adaptive policy instruments.

Communication plays a crucial role in shaping food systems that are both inclusive and resilient. In Latin America, where food insecurity often intersects with structural inequalities, effective communication is essential for promoting healthy behaviors, disseminating rights-based nutritional knowledge, and fostering collective engagement in food governance. The 7S-Based Feeding framework—through dimensions such as Sovereignty, Solidarity, and Satisfaction—implicitly embeds communicational processes, making it a valuable analytical tool to interrogate how food-related messages are shared, contested, and co-produced across social, political, and public health spheres.

Although increasing academic attention has been given to the interconnections between feeding, public health, and sustainability—particularly through the growing number of studies that explore these links from environmental and nutritional standpoints [22,23,24]—the 7S-Based Feeding framework has yet to be formally recognized as a unified conceptual approach in the scholarly literature. Existing research tends to address each dimension separately, without establishing explicit, integrated connections among health, safety, sustainability, sovereignty, social inclusion, solidarity, and dietary satisfaction.

This theoretical and methodological gap raises a critical question: To what extent have the components of 7S-Based Feeding been studied within human development and comprehensive public health in Latin America? To address this, the present integrative review is structured around the following research questions:

- Which dimensions of 7S-Based Feeding have been most studied in relation to human development and public health in Latin America?

- Are there documented synergies between 7S-Based Feeding and the One Health approach in the academic literature?

- Which gaps exist in the literature regarding the integration of 7S-Based Feeding into public policies?

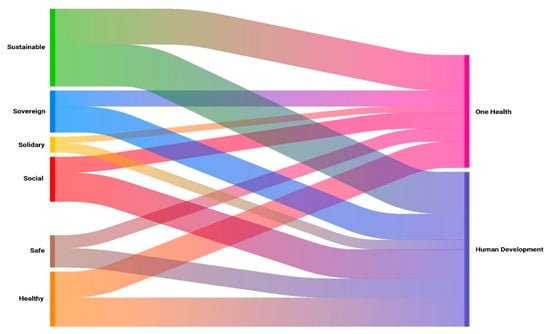

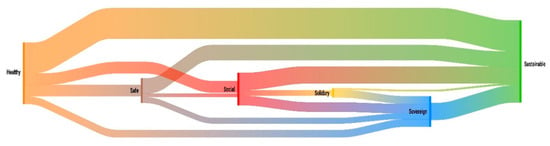

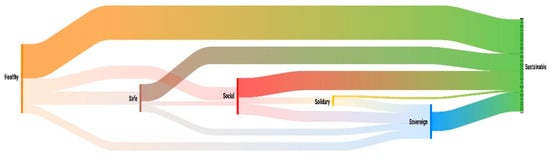

To synthesize key findings, a Sankey diagram was developed to visualize connections between 7S-Based Feeding dimensions, the One Health approach, and their impact on human development. To synthesize key findings and to better visualize the combined presence and co-occurrence of the 7S dimensions, the One Health approach, and human development themes across the reviewed articles, a Sankey diagram was generated, as presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Sankey diagram of the integration of 7S-Based Feeding with the One Health approach and human development.

This diagram was developed from the qualitative content analysis conducted using ATLAS.ti. Codes representing each thematic component were applied to the full texts of the 18 selected articles. The relative thickness of the links in the diagram reflects the frequency and interconnection of co-occurrences among these codes, offering a visual synthesis of the integrative potential among the 7S framework, One Health, and human development.

The following eight findings represent the original results of this integrative review. They were derived through a qualitative coding process conducted using ATLAS.ti, applied to the full texts of the 18 selected articles. The results were interpreted based on the frequency and intersection of coded categories corresponding to the 7S dimensions, the One Health approach, and human development indicators. These findings are not previously published and reflect patterns of thematic co-occurrence visualized in the Sankey diagram (Figure 2). Based on this visual and conceptual mapping, the most relevant findings are presented below in a structured form:

- The Sustainable dimension emerges as the most transversal element of the 7S-Based Feeding model, demonstrating strong connections to both the One Health approach and human development.

- Healthy and Safe dimensions, historically associated with nutrition and food safety, show significant linkages to human development. Their connection to One Health particularly highlights feeding’s role in disease prevention and comprehensive well-being promotion.

- The Social dimension occupies a strategic position, serving as a conceptual bridge between feeding systems, equity, and community participation. Its dual relationship with One Health and human development suggests that more integrative studies recognize social cohesion and food justice as social determinants of health.

- Sovereign and Solidary dimensions exhibit relevant but less frequent connections, indicating their presence in regulatory frameworks or community-focused studies, though not yet fully integrated into regional policy-oriented research.

- The Satisfactory dimension remains unrepresented in the diagram, reinforcing the previously noted conclusion of its systematic absence in the literature.

- The intersection between One Health and 7S-Based Feeding is particularly strong in studies addressing sustainability, health, and governance simultaneously, suggesting an emerging trend toward collaborative intersectoral models still in development.

- Connections to human development span multiple dimensions but concentrate especially on those linking health, food safety, and territorial resilience. This confirms that the 7S-Based Feeding framework, while not yet officially recognized as a formal concept, effectively functions as a structural criterion for evaluating population well-being in the region.

The previous literature has noted the importance of framing food communication not only through nutritional or safety lenses, but also through culturally embedded narratives that reflect social justice, identity, and environmental stewardship [25,26]. The 7S approach, by integrating values such as Social, Sustainability, and Solidarity, aligns with calls for more dialogical and transformative models of food communication. This alignment underscores the need to shift from top-down informational models toward participatory frameworks that allow for the co-creation of food knowledge, particularly among marginalized populations in the Global South.

This article is organized as follows: Section 1 contextualizes the study within food safety and public health fields, emphasizing the need for an integrative approach incorporating 7S-Based Feeding in relation to the One Health model. The research problem is established and justified based on existing literature gaps. Section 2 details the PRISMA methodology application, explaining search processes, article selection/exclusion criteria, and databases employed.

Section 3 presents results from the analysis of selected articles, examining how each 7S-Based Feeding dimension has been addressed in the Latin American context and identifying potential synergies with One Health. Section 4 discusses findings in comparison with previous studies and reflects on challenges for integrating 7S-Based Feeding into public policies. Finally, Section 5 synthesizes key conclusions, highlighting contributions to the public health and food safety fields.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed an integrative literature review following PRISMA guidelines to ensure transparency and reproducibility in article selection. The review focused on identifying how components of the 7S-Based Feeding framework have been studied in relation to human development and comprehensive public health in Latin America.

The literature search was conducted in ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, and MDPI between 2 February and 27 March 2025. These databases were selected for their extensive access to open-access, peer-reviewed literature in the fields of public health, nutrition, food systems, and sustainability, with strong representation of research relevant to Latin America. While broader indexing databases such as Scopus and Web of Science were considered, the chosen platforms ensured accessibility, thematic relevance, and inclusion of emerging regional scholarship from the Global South. The search period spanned from 2015 to 2025 to include recent and relevant studies.

2.1. Search Strategy

The search strategy combined key terms using Boolean operators (AND, OR), resulting in the following query: (“One Health”) OR (“One Health” AND (“Nutrition” OR “Food Safety”) AND “Latin America”) OR (“One Health” AND “Human Development” AND “Latin America”) OR (“Nutrition” OR “Food Safety” AND “Human development” AND “Latin America”).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The search was conducted from 2 February 2025, to 27 March 2025, and was limited to publications in the disciplines of nutrition and food science, public health, economics and development, sociology and anthropology, and political science to ensure that the results focused on the objective of this review. To ensure the relevance of the selected studies, the following criteria were applied:

Inclusion criteria:

- Peer-reviewed articles (2015–2025).

- Studies focused on Latin America or with a global scope including Latin America.

- Articles analyzing links between feeding, public health, and human development.

- Research incorporating at least one of the following:

- Integration of the One Health approach in feeding and food safety analyses.

- Examination of one or more dimensions of 7S-Based Feeding (Healthy, Sustainability, Safety, Sovereignty, Social, Solidarity, Satisfaction).

- Discussion of the impact of feeding systems on human development and public health.

- Systematic reviews, case studies, and empirical articles with primary data.

Exclusion criteria:

- Purely technical studies (e.g., agribusiness and agricultural economics) without public health relevance.

- Food safety studies lacking explicit health, sustainability, or sovereignty focus.

- Restricted-access or unverifiable documents.

2.3. Study Selection and Filtering Process

Although the search covered the period from 2015 to 2025, no articles published in 2025 met the inclusion criteria or were available in full at the time of analysis. As a result, the final sample includes publications from 2015 to 2024.

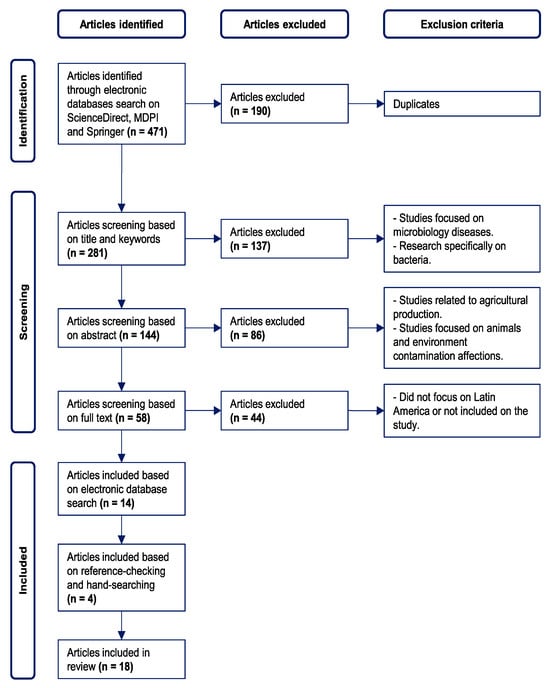

Following the PRISMA workflow, 471 articles were identified in the consulted databases, of which 190 were removed due to duplication, leaving 281 documents. Subsequently, 137 articles were discarded as they were identified as studies focused on microbiological diseases and studies on bacteria, resulting in a total of 144 articles. From these, 86 articles related to agricultural production and diseases caused by environmental and ambient pollution, with no relation to food, were excluded, leaving 58 articles.

Then, 44 articles were eliminated for not being focused on Latin America or for not including Latin America in the study, resulting in 14 relevant articles. However, to complement this integrative review, a manual search was conducted in the bibliographic references of the relevant articles, identifying four related articles, resulting in a total of 18 articles included in this review. Figure 3 shows the flow diagram of the article selection process according to PRISMA.

Figure 3.

Flow diagram of the article selection process.

2.4. Data Analysis

For data analysis and interpretation, ATLAS.ti software was utilized as a qualitative analysis tool to organize, code, and visualize emerging patterns in the reviewed literature. This software facilitated the identification of thematic categories related to the 7S-Based Feeding framework and the One Health approach, enabling systematic information structuring and cross-study comparisons. Coding was performed inductively and deductively, combining keyword searches with recognition of conceptual connections between articles.

All interrelationships, co-occurrences, and thematic flows presented in the results—particularly in Sankey diagrams and tables—are derived directly from the coding of the 18 selected articles. These interpretations are grounded in the evidence extracted from the texts analyzed using ATLAS.ti.

This approach allowed not only for the systematization of findings but also for the detection of synergies and gaps in the literature. The results of the analyzed studies are presented below, highlighting the most relevant findings concerning 7S-Based Feeding and its interaction with the One Health approach and human development.

Table 1 provides a summary of the selected studies, including the following fields for each article: authors, research question/objective, methodology, and research design. The studies listed below have been ordered alphabetically by the first author’s last name to enhance clarity and consistency in the presentation of the analyzed materials. Subsequently, a qualitative analysis of the 18 articles was conducted, examining the following aspects for each study:

Table 1.

PRISMA-informed synthesis table including study characteristics.

- (a)

- Geographic region and study period: The specific geographic focus (Latin America or subregions) and time period covered were documented.

- (b)

- 7S components addressed: The 7S-Based Feeding dimensions examined in each article were identified.

- (c)

- Integration of the One Health approach: Whether the article explicitly incorporated the One Health framework was evaluated, particularly regarding human health connections.

- (d)

- Link to human development and public health: How each study connected feeding components to human development and public health outcomes was analyzed, emphasizing impacts on quality of life, equity, and population well-being.

Table 2 presents a detailed summary of the following fields for each article: authors, study period, country/geographic region, 7S-Based Feeding dimensions addressed, One Health approach (if applicable), and connection to human development and public health.

Table 2.

Summary of key findings from qualitative analysis of selected studies.

While the core analysis was qualitative and based on thematic coding, the use of frequency counts and diagrams served to complement and visualize the distribution and interconnections of codes, without substituting the interpretative depth required in qualitative research.

3. Results

The systematic review identified 18 articles directly addressing one or multiple components of the 7S-Based Feeding framework (Healthy, Sustainable, Safe, Sovereign, Social, Solidarity-based, and Satisfactory) within the context of human development and comprehensive public health in Latin America. These studies also explicitly incorporated or mentioned the One Health approach, exploring connections between human health and other dimensions.

3.1. Analysis by Geographic Region and Study Period

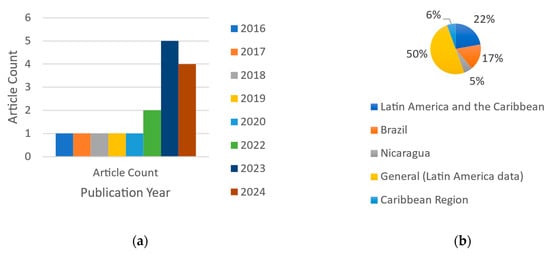

Analysis of academic output on food systems and their relationship with the One Health approach reveals a growing publication trend in recent years, as shown in Figure 4a. While relatively low output was observed between 2016 and 2019 (with only one article per year), the number of publications began increasing in 2020, peaking in 2023 with five articles.

Figure 4.

Distribution of reviewed articles by (a) publication year and (b) region or country of study.

In 2024, academic output continued to rise (four articles), suggesting sustained interest in the intersection of food safety, sustainability, and public health. This pattern reflects growing global concern about food safety and climate change impacts on food production, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic, which exposed vulnerabilities in food systems.

Regarding geographic distribution, the analysis reveals a predominance of studies focused on Latin America and the Caribbean, suggesting particular interest in this region due to its high biodiversity, agricultural significance, and food safety challenges. Four articles were identified with explicit focus on Latin America and the Caribbean, while three studies specifically addressed Brazil—one of them centered on Curitiba—reflecting this country’s importance in food production/export and implementation of sustainable food policies.

Nicaragua emerged as a particular case study, highlighting the relevance of local-level analyses in developing contexts. Additionally, one study focused on the Caribbean, a region especially vulnerable to climate change impacts on food production and water access. Beyond regional focus, nine studies adopted global perspectives, developing tools applicable across contexts or evaluating international trends in food safety, sustainability, and public health. Overall, as shown in Figure 4b, the geographic distribution demonstrates a balance between globally-scoped studies and those examining Latin America and Caribbean contexts.

This distribution shows a strong research orientation toward food safety, sustainability, and public health aspects, with less emphasis on solidarity and food sovereignty. To further examine these findings, the following section presents a qualitative analysis of the 7S-Based Feeding dimensions, identifying patterns, gaps, and research opportunities for each.

3.2. Analysis of 7S-Based Feeding Dimensions

To understand the impact of food systems on human development and comprehensive public health in Latin America, it is fundamental to examine how the 7S-Based Feeding framework is addressed in the scientific literature. In this qualitative analysis, each dimension of the 7S-Based Feeding has been identified in the selected articles through a systematic approach based on the explicit presence of key terms, the context in which they are framed, and the relationship they establish with the One Health approach.

To ensure a systematic and replicable approach, a detailed classification scheme was developed using predefined criteria and thematic indicators for each 7S-Based Feeding dimension. This scheme, fully outlined in Table 3, includes key aspects and search terms that guided the coding process within ATLAS.ti and ensured consistency in identifying each dimension. To ensure that each 7S-Based Feeding dimension was contextually rather than semantically identified, this table developed established, operational definitions and interpretative cues, allowing for grounded content analysis through the software ATLAS.ti. The following interpretations and visualizations represent an analytical synthesis of the 18 selected articles coded in ATLAS.ti, without incorporating external literature sources beyond those included in the final review set.

Table 3.

Framework of specific criteria and terms for detecting 7S-Based Feeding dimensions.

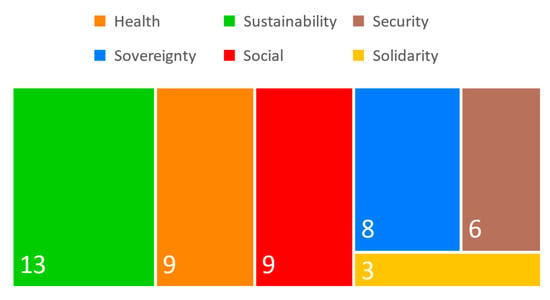

The analysis of the reviewed articles reveals a marked priority in the Sustainability dimension, which is present in 13 of the analyzed articles. This reflects the growing concern for the environmental viability of food systems. The Healthy and Social dimensions follow in importance, each mentioned in nine articles, indicating a strong focus on the relationship between food and human well-being, as well as on the inequalities that affect access to healthy and sustainable food.

On the other hand, the Sovereign dimension is a relevant theme in eight studies, highlighting the importance of the autonomy of local food systems and resistance to the influence of transnational corporations. The Safe dimension, present in six articles, has been mainly studied from a cooperation perspective, while Solidarity has been the least addressed with only three articles in the analyzed literature. Finally, no studies were identified that explicitly addressed Satisfaction as a central dimension in food systems. These findings can be observed in Figure 5, which presents the count of articles in which each of the analysis dimensions is addressed.

Figure 5.

Coverage of the 7S-Based Feeding elements in the reviewed articles.

The numeric representation of dimensions, such as the Healthy and Social dimensions each appearing in nine articles, was derived from the structured qualitative coding performed using ATLAS.ti. Presence was coded only when a dimension was substantively discussed in the article, according to the criteria established in Table 3. The co-occurrence of dimensions was further explored through relational coding, which was then visualized to support interpretation, not to replace it.

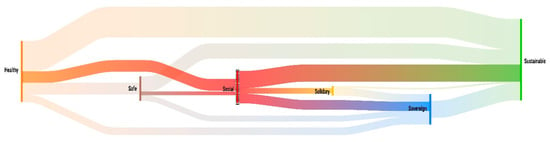

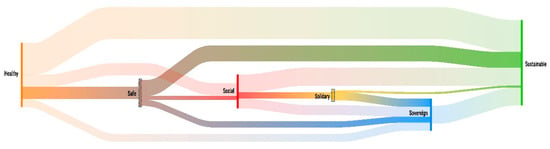

The use of ATLAS.ti and the coding applied to the selected articles allowed for the identification of between certain synergies in the interactions of the 7S-Based Feeding dimensions, generating Sankey diagrams with the purpose of visualizing specific flows and connections between the different components of this study. Figure 6 offers an overall view of how the 7S-Based Feeding dimensions interact within the analyzed literature, highlighting interdependencies across the full framework.

Figure 6.

General overview of the 7S-Based Feeding elements interactions Sankey diagram.

The synergies visualized in Figure 6 are based on the co-occurrence of coded dimensions in the same analytical units across articles. These were manually identified through qualitative interpretation of how different 7S dimensions were conceptually linked in the literature (e.g., discussions of health and sustainability in the same section of an article). ATLAS.ti was used to organize and visualize these relationships, not to generate them automatically.

Firstly, Healthy and Safe are observed to be key starting points within the analysis, indicating that food safety and nutritional quality are central factors in the analyzed studies. These dimensions do not operate in isolation but rather interrelate with other elements such as the Social and Sovereign dimensions, demonstrating the importance of community and equity factors in food systems.

Simultaneously, the Social dimension is presented as a key intermediate node, acting as a bridge between Safe and other dimensions such as Solidarity and Sovereign. On the other hand, Sovereign is linked with Solidarity, suggesting that control over food systems is not only a political or economic issue but is also influenced by values of cooperation and equity. Finally, Sustainability is presented as the final outcome of the interaction between all of the previous dimensions, consolidating itself as the objective towards which all other dimensions converge.

This analysis of the interaction between the 7S-Based Feeding dimensions reveals that the Social dimension plays a central role in the connection and transition between other key dimensions of the food system. Figure 7 focuses specifically on the Social dimension, portraying its bridging role and examining its cross-cutting relevance among other dimensions. It is observed how the Healthy, Safe, Sovereign, and Solidary dimensions are significantly linked to the Social dimension, which acts as an intermediate node that channels and modulates these relationships. This finding reinforces the importance of social dynamics in the configuration of food systems, which has been previously noted in studies on food safety and social security [28].

Figure 7.

Sankey diagram highlighting the central role of the Social dimension.

Figure 7 specifically highlights how this dimension serves as a critical bridge between food safety and sustainability, demonstrating that dietary practices cannot be analyzed in isolation but are rather influenced by social, cultural, and community factors. This aligns with the right-to-food framework, which emphasizes the need for inclusive and equitable food systems [20].

The intersection of the Social dimension with food safety and sovereignty becomes particularly relevant in crisis contexts, where food sovereignty policies have proven crucial for democratizing food governance [19] Food insecurity not only affects access to nutrition but also carries implications for social and political stability, as evidenced by research on domestic terrorism and unequal resource access [27].

Sovereign maintains deep connections with the Social dimension by emphasizing community autonomy in defining food production and distribution strategies. In Latin America, food sovereignty policies have been instrumental in democratizing food system governance, enabling greater participation of small producers and promoting more equitable models [33].

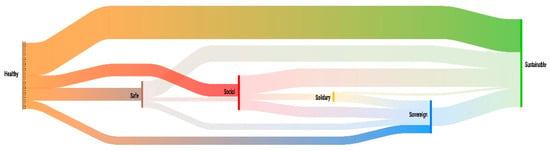

While the Social dimension emerges as a key articulator within food systems, the Healthy dimension constitutes a determinant factor in shaping safe, sustainable, and accessible food systems. Figure 8 isolates the Healthy dimension to examine its direct and indirect links to food safety and sustainability, underscoring its foundational role in promoting well-being. Reveals strong interconnections between Healthy and both Safe and Sustainable dimensions, suggesting that nutritional health cannot be understood without considering safety and sustainability impacts across food production and consumption.

Figure 8.

Sankey diagram highlighting the role of the Healthy dimension.

The Healthy dimension reflects complex relationships with environmental, sanitary, and productive factors. A central aspect involves the role of food production/consumption in public health, where exposure to harmful substances (pesticides and emerging contaminants) presents significant challenges in Latin America [33].

The Healthy–Safe linkage underscores health risks associated with zoonoses and foodborne illnesses, particularly in meat production and animal product consumption [30]. In the Caribbean, for instance, the high prevalence of bacterial pathogens in animal production systems reinforces the need for strengthened food safety surveillance and regulations [32].

The Healthy-Sustainable connection emphasizes the necessity of dietary transitions to reduce negative impacts of current production systems while improving access to healthy/sustainable diets [37]. Technological innovations in alternative proteins and sustainable agriculture have been identified as key strategies for enhancing food system resilience and climate change mitigation [38].

Sovereign extends beyond access and control to influence food quality and safety. Reliance on industrial mass-production systems has generated public health issues, including increased incidence of zoonotic diseases and antibiotic-resistant bacteria in animal production [32].

Nevertheless, within the food system, Sustainable is the most frequently addressed dimension in the analyzed articles, reflecting the growing global concern for sustainability in food production and consumption. The analysis of the reviewed articles reveals a marked priority in the Sustainability dimension, which is present in 13 of the analyzed articles. This reflects the growing concern for the environmental viability of food systems—particularly regarding climate resilience, pollution reduction, and resource conservation. While sustainability is a multidimensional concept that includes social and economic aspects, the analysis in this review focused primarily on environmental sustainability indicators, as detailed in Table 3.

Figure 9 highlights the Sustainable dimension and its extensive connections across the framework, particularly in terms of environmental and socioeconomic relevance. Sustainable dimension establishes strong connections with Healthy, Safe, Social, and Sovereign, evidencing its cross-cutting role in the transformation of the food system toward a more equitable and regenerative model.

Figure 9.

Sankey diagram highlighting the role of the Sustainable dimension.

The importance of sustainability in food system analysis responds to the need to ensure food safety and social welfare without compromising natural resources. Justice and equity in food systems have been the subject of intense debate in Brazil, where various proposals seek to balance economic interests with environmental preservation and the safety of small producers [36]. This tension is also observed in water management, an essential resource for food production that faces inequalities in access and quality in Latin America [21].

One of the main challenges at the intersection between Sustainable and Safe is the contamination of agricultural ecosystems by pesticides and toxic waste, which affects soil, water and food quality in the region [33]. Likewise, the protection of marine ecosystems has been proposed as a key strategy to improve nutrition and equitable access to protein sources, ensuring the sustainability of fisheries and marine biodiversity [41].

Finally, Sustainability and Sovereignty are intrinsically related. A truly sustainable system must not only minimize its environmental impact but also empower local communities to autonomously and resiliently manage their own resources. In this sense, food sovereignty is key to ensuring that peoples do not depend on volatile external markets but rather strengthen their sustainable production capacities [39].

To conclude this analysis, while sustainability, health and sovereignty have been widely studied in the food systems literature, Figure 10 presents a focused analysis of the Safe and Solidarity dimensions, which are less emphasized in the literature, yet crucial for equitable and secure food systems. It shows that the Safe and Solidary dimensions have received less attention in the reviewed studies. This suggests that food safety continues to be addressed mainly from a technical or regulatory perspective, without deep integration with other dimensions of the food system.

Figure 10.

Sankey diagram highlighting the role of the Safe and Solidarity dimensions.

Similarly, solidarity, although recognized as a key principle in food governance, has been less frequently explored in terms of concrete cooperation strategies and equitable food distribution.

Food safety is a fundamental pillar in the transition toward more equitable and sustainable food systems. However, the reviewed studies show that this dimension has been addressed in a fragmented manner, focusing mainly on regulatory and food safety aspects, with less attention to its interrelationship with socioeconomic factors and resource access [29].

Unlike other dimensions such as Sustainability or Sovereignty, Solidarity has been scarcely addressed in the reviewed studies, indicating a gap in the exploration of cooperation strategies within food systems. Despite growing concern about equity in food access, food solidarity initiatives have been documented mainly in terms of social movements and political resistance, rather than as formal mechanisms for distribution and mutual support [36].

From a broader perspective, solidarity in food systems is also related to social welfare and trust in institutions, factors that have been identified as determinants for stability and the acceptance of new food production and distribution strategies [34]. However, the lack of structured policies that promote cooperation among producers, distributors and consumers remains an obstacle to the effective integration of this dimension in food systems.

The analysis of the 7S-Based Feeding dimensions has allowed for the identification of key patterns in the academic literature, highlighting how certain dimensions, such as sustainability, health and social aspects, have been widely addressed, while others, such as solidarity and safety, have received less attention.

However, to more deeply understand the interconnection between food, public health and human development in Latin America, it is essential to analyze how these elements have been integrated within the One Health approach. Next, we examine how the reviewed literature has incorporated this perspective and what the main challenges and opportunities are in its application.

3.3. Analysis of the Integration of the 7S-Based Feeding with the One Health Approach

In Latin America, the need to integrate the One Health approach becomes particularly relevant given the high burden of diseases related to consumption of ultra-processed products, tobacco, alcohol and other harmful dietary practices, as warned by Reynales-Shigematsu et al. [40] who directly link these factors to public health outcomes and propose intervention strategies from a food perspective.

Likewise, the development of tools such as the Global One Health Index (GOHI) has allowed for the evaluation of the performance of food systems through integrated health, environment and food safety indicators, highlighting the need for systemic approaches to address health and nutritional risks in regions like Latin America [31]. In this context, this section analyzes how the selected articles have incorporated this approach, whether totally, partially or absent, identifying trends, gaps and opportunities to strengthen its application in research and public food policies in the region.

The analysis of the incorporation of the One Health approach in the selected articles reveals an even distribution among three levels of integration: total, partial and absent, with six studies in each category. This trend indicates that, while there is growing recognition of the One Health approach in recent literature, its full application is not yet widespread. As shown in Figure 11, only one third of the analyzed studies explicitly and systematically integrate the human, animal and environmental components in their analytical frameworks. Another third partially addresses some of these components, typically human and environmental health, without fully incorporating the animal dimension.

Figure 11.

Assessment of One Health approach incorporation in the reviewed articles.

Finally, one–third of the articles completely omit application of the approach, focusing their analyses on social, political or economic aspects without articulating them with ecological or health determinants. This distribution demonstrates both the progress and current limitations in adopting the One Health approach within food studies in Latin America. Table 4 summarizes the main studies that explicitly incorporate the One Health approach in food system analyses in Latin America and the Caribbean. This synthesis reveals how articles vary in their themes, geographic scales, and approaches to operationalizing the framework.

Table 4.

Comparative overview of explicit One Health integration in the reviewed articles.

All included studies integrate at least two of the three One Health components (human, animal and environmental health), with four representing examples of full integration. For instance, the study by De Moura et al. [29] on the One Health Index applied to Curitiba constitutes an advanced model of comprehensive urban assessment, while Pérez-Escamilla’s [39] work links food safety with Sustainable Development Goals, bridging population health and environmental sustainability. Other studies like hose by Hilber et al. [33] and Espinosa et al. [30] address challenges such as pesticide exposure and zoonotic diseases from an intersectoral perspective. Collectively, this table reinforces that One Health adoption is expanding, though its application remains more common in environmentally- and epidemiologically-oriented studies than those focused on social or political dimensions.

The studies compiled in Table 5 represent works that, while not explicitly applying the One Health approach or integrating all three core components (human, animal, and environmental health), do substantively address two of them—primarily human-environmental combinations. This pattern reflects a common trend in the recent food and environmental literature, where ecological impacts and public health effects are considered interrelated, though without full articulation with animal health or explicit mention of the One Health approach.

Table 5.

Comparative overview of articles with partial One Health integration.

For example, Mahlknecht and González-Bravo [35] examine the water–energy–food nexus in Latin America and the Caribbean, highlighting links between natural resource access and food safety from environmental and human perspectives. Similarly, Viana et al. [41] analyze how marine protected areas can enhance human nutrition while promoting marine ecosystem conservation.

Meanwhile, Mešić et al. [38] and Elver [20] address the need to transform food systems toward sustainable, adaptable models by integrating environmental and population health components, though without considering animal dimensions or explicitly using the One Health conceptual framework. Articles like McDermid et al. [37] and Ingutia [21] explore social, institutional and equity dimensions in resource access, enriching the analysis of structural determinants affecting public health, though from legal or social justice frameworks. Together, these studies demonstrate a growing commitment to interdisciplinarity while revealing the need for more complete and explicit adoption of the One Health approach in food and sustainability research across Latin America.

To conclude this analysis, Table 6 presents articles that, while analyzing topics closely related to health, food, or sustainability, neither integrate the One Health approach nor mention it as a conceptual framework. In these works, dimensions comprising the One Health approach—such as animal health or environmental impacts—are either completely absent or treated fragmentarily without connection to human health or food systems.

Table 6.

Comparative overview of articles with absent One Health integration.

For instance, the study by Reynales-Shigematsu et al. [40] focuses on the reduction in alcohol and tobacco consumption as a strategy for cancer prevention, addressing risk factors exclusively from a public health perspective, without considering their connection to food systems or environmental impacts. Other studies, such as those by Maluf et al. [36] and Godek [19], examine sustainability, food sovereignty, and political participation through a lens of social justice, yet they do not incorporate ecological or health determinants into their analytical frameworks.

Similarly, the study by Bellinger and Kattelman [27] links food insecurity to sociopolitical instability in developing countries, focusing its analysis on conflict and structural violence. In contrast, works such as those by De Araújo Palmeira et al. [28] and López-Concepción et al. [34] address local governance and the perception of well-being from an institutional and public policy perspective, without considering the ecological or animal dimension. Overall, these studies make significant contributions to the analysis of social, political, and cultural factors related to food, yet they overlook the transdisciplinary approach that characterizes the One Health framework.

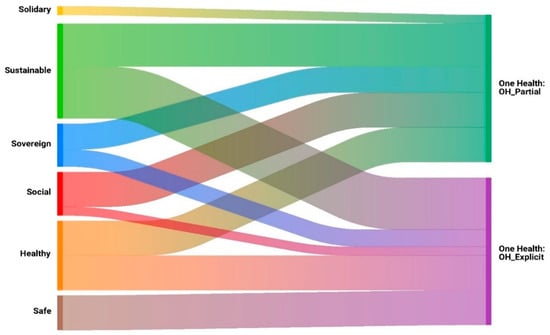

To further explore the relationship between 7S-Based Feeding and the One Health approach, a Sankey diagram was developed, as shown in Figure 12, which links each dimension to the articles that incorporate this approach, either explicitly or partially. This visualization makes it possible to identify which dimensions are prioritized or underrepresented within the studies that adopt the One Health framework, and it offers a synthetic overview of the most frequent thematic connections among health, sustainability, security, and sovereignty in the recent scientific literature.

Figure 12.

Sankey diagram analyzing the relationship between the 7S-Based Feeding dimensions and the explicit and partial implementation of the One Health approach.

This Sankey diagram visualizes the interconnections between the dimensions of 7S-Based Feeding and the studies that incorporate the One Health approach either explicitly or partially. The represented flows allow for the identification of which food-related dimensions are most present in studies that adopt this framework, and whether these connections are addressed comprehensively or in a fragmented manner.

Sustainable and Healthy are the dimensions with the highest number of links, both in studies that apply the approach explicitly and in those that do so partially. This reinforces previous findings that these dimensions lie at the core of current concerns regarding food systems, particularly in relation to environmental risks, zoonotic diseases, and the transition toward more resilient models. The Safe dimension appears primarily in studies with an explicit focus, suggesting that food safety is closely linked to the use of formal tools such as the One Health Index or integrated assessments of health risks.

In contrast, the Sovereign and Solidary dimensions are scarcely represented in studies that explicitly address the One Health approach, and even among those that apply it partially. This suggests that the values of food self-determination, cooperation, and community support networks remain isolated topics within the literature operating under the One Health framework, representing a significant gap for future interdisciplinary research. Finally, the Social dimension is linked to both types of integration (explicit and partial), though with less intensity than the more technical-health dimensions. This indicates that the social component tends to be included as context or a conditioning factor, but not always as an active variable in intersectoral health analysis models.

Understanding how food systems impact human development requires moving beyond technical or sectoral analysis. The dimensions of 7S-Based Feeding and the One Health approach offer tools for diagnosing problems and proposing solutions, yet their true value emerges when connected to indicators of well-being, equity, and public health.

The following section analyzes how the reviewed articles establish a clear relationship between food systems and comprehensive human development in the Latin American context, identifying approaches, gaps, and opportunities for food policies with sustained social impact.

3.4. Analysis of the Connection Between 7S-Based Feeding, Human Development, and Public Health

Food systems directly and indirectly influence multiple dimensions of human development and comprehensive public health, particularly in regions such as Latin America, where structural inequalities exacerbate the social, environmental, and health impacts of food. 7S-Based Feeding and the One Health approach provide a valuable conceptual framework to explore connections across human, animal, and environmental health. However, our review found that its methodological integration with indicators of well-being, justice, and quality of life is still limited in the current literature.

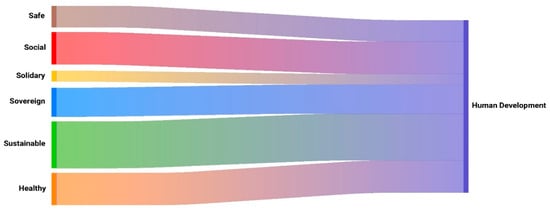

This section analyzes how the studies included in this review articulate food with key dimensions of human development, such as access to basic services, nutrition, equity, local governance, and subjective well-being. Through this exploration, the aim is to identify patterns, gaps, and opportunities to strengthen a more comprehensive and people-centered perspective within regional food policies. To visualize these interconnections, a Sankey diagram was developed, as shown in Figure 13, which makes it possible to observe which dimensions are more prominent in the academic discourse related to human development and which remain underrepresented.

Figure 13.

Sankey diagram analyzing the connections between the 7S-Based Feeding dimensions and human development in the reviewed articles.

Figure 13 visually presents the connections between 7S-Based Feeding and human development, revealing a clear pattern of predominance of certain dimensions over others. Among them, Sustainable, Healthy, and Safe appear most frequently in relation to human development. This can be explained by the way the recent scientific literature emphasizes the sustainability of food systems, disease prevention, and safe access to food as essential conditions for improving well-being and reducing social and environmental vulnerabilities.

The Social dimension also shows a significant presence in connection with human development, particularly in articles that address equity, participatory governance, and collective well-being. In contrast, the Sovereign and Solidary dimensions appear to a lesser extent, generally in studies that promote community participation, cooperation among stakeholders, and food autonomy, although still with limited analytical depth. Finally, the Satisfactory dimension remains absent, suggesting a notable omission regarding the recognition of enjoyment, cultural identity, or the subjective experience associated with food as part of comprehensive human development.

This diagram not only highlights current conceptual contributions, but also reveals asymmetries in the integration of the 7S-Based Feeding dimensions within the human development framework. This opens a field of opportunity for future research aimed at strengthening the connection between food and human well-being in a holistic manner.

In addition to the visual analysis presented in Figure 13, the information was systematized in a table that summarizes the articles presenting an explicit link between the 7S-Based Feeding dimensions and human development.

Table 7 identifies the four most frequently addressed dimensions and describes how each is related to key indicators of well-being, public health, equity, or resilience. This synthetic representation provides a clear view of which dimensions have greater empirical and conceptual support in the recent academic literature, as well as the types of contributions being made from an interdisciplinary and applied perspective.

Table 7.

Most frequently 7S-Based Feeding dimensions connected to human development in the reviewed articles.

Table 7 synthesizes the most robust connections between the dimensions of 7S-Based Feeding and human development, identifying the articles that address these links in an explicit and relevant manner. Sustainable, Healthy, Safe, and Social are the most interconnected dimensions, reflecting a trend in the recent literature to prioritize issues such as access to natural resources, nutrition, food safety, and social equity as structural conditions of human well-being.

These links are explored through various approaches, ranging from epidemiological analysis to proposals for participatory governance and technological adaptation. While several dimensions of the 7S show a clear articulation with human development, others exhibit a much more limited or marginal presence in the reviewed literature. This is the case for the Sovereign, Solidary, and Satisfactory dimensions, whose connections appear less frequently and, in some cases, in an indirect or implicit manner.

Table 8 summarizes the articles that address these aspects, indicating the type of connection they establish with human development and the approaches used. This representation helps to highlight both the existing analytical gaps and the opportunities for future research that integrates these perspectives into the discussion on food systems and human well-being.

Table 8.

The least frequently mentioned 7S dimensions connected to human development in the reviewed articles.

In particular, the Sovereign dimension is addressed in articles that discuss food autonomy and the democratization of governance, while Solidary appears linked to proposals for cooperation and social justice, although with limited discussion. In contrast, the Satisfactory dimension was not represented in any of the articles analyzed, reinforcing the notion that current studies tend to privilege technical or structural perspectives, overlooking subjective aspects such as the pleasure of eating, cultural identity, or emotional satisfaction, all of which are essential to a comprehensive understanding of human development.

In general, the results obtained reveal consistent patterns in the way the analyzed studies address the dimensions of 7S-Based Feeding and their relationship with public health and human development in Latin America. Based on these findings, the following section offers a critical reflection on their implications, the tensions between theoretical and applied approaches, and the opportunities that arise to guide future research and integrative public policies.

4. Discussion

Although the findings reveal relevant patterns and interconnections between the 7S-Based Feeding framework, One Health, and human development, we acknowledge that the limited number of high-relevance articles (18) may constrain the generalizability of the conclusions across all Latin America. The rigorous inclusion criteria may have excluded some partially relevant studies, and expanding the scope in future reviews could potentially alter the observed frequency of specific dimensions. Therefore, the current study should be interpreted as an exploratory mapping of the existing literature, highlighting current gaps rather than offering a comprehensive regional diagnosis.

The analysis conducted allows for a critical reflection on the degree of development and articulation achieved by the dimensions of 7S-Based Feeding in the recent scientific literature, as well as their relationship with the One Health approach and their potential as a structuring axis for public policies aimed at human development in Latin America.

Unlike other systematic reviews that address the link between food safety, public health, and sustainability from fragmented or sectoral perspectives, this study proposes an integrative analysis based on the 7S-Based Feeding model, articulated with the One Health approach and specifically focused on Latin America. This approach makes it possible to move beyond the thematically limited perspective that characterizes much of current research, and proposes a holistic reading of food systems as interdependent socio-ecological structures with direct implications for human development.

Likewise, although there is growing interest in issues such as nutritional equity and the integration of gender perspectives into food policies, as evidenced by the studies of Nisbett et al. [42] and Agarwal [43], these approaches have not yet been incorporated into a comprehensive framework such as 7S-Based Feeding. The study conducted in this article complements these perspectives by situating them within a broader context that also includes sovereignty, solidarity, knowledge, and satisfaction as pillars of food system development.

In the field of global health, reviews such as those by Pungartnik et al. [44] examine the interfaces between One Health and Global Health, emphasizing the need for intersectoral collaboration yet without delving into food-related dimensions or their implications for regional human well-being. In contrast, studies like those by Sperling et al. [45] on food safety in the COVID-19 context highlight the resilience of food systems, but they do so without incorporating integrated models such as 7S-Based Feeding, nor do they address cultural, political, or community-based analytical approaches.

In the Latin American context, this study expands upon the contributions of research such as the studies by Shamah-Levy et al. [46] on food governance in Mexico and Justo et al. [47] on real-world evidence in public health by incorporating subjective cultural and political dimensions that are often excluded from institutional technical analysis. To proceed with this section, each of the research questions outlined in Section 1 will be addressed based on the findings obtained.

4.1. Which Dimensions of 7S-Based Feeding Have Been Most Studied in Relation to Human Development and Public Health in Latin America?

In the conducted analysis, the Sustainable dimension emerged as the most frequently addressed among articles classified as highly relevant, reflecting persistent concerns about the ecological viability of food systems in Latin America. This trend aligns with international studies emphasizing the urgent need to strengthen environmental resilience in food production and consumption. However, the approach found in the reviewed studies tends to focus primarily on ecological aspects, relegating the economic and social dimensions of sustainability to secondary importance.

Conversely, dimensions such as Solidary and Satisfactory exhibit limited or absent representation. This omission aligns with previous critiques in the literature highlighting how predominant food systems approaches frequently overlook cultural, affective, and relational factors—elements equally essential for social well-being and cohesion. In this context, the present study identifies a significant gap warranting exploration in future research focused on the subjective value of food systems, particularly in diverse and culturally rich contexts such as Latin America.

4.2. Are There Documented Synergies Between 7S-Based Feeding and the One Health Approach in the Academic Literature?

Although some identified articles explicitly apply the One Health approach while others address it partially, structural integration between this paradigm and the 7S-Based Feeding dimensions remains limited. Cases documenting direct application of the approach typically include tools such as the One Health Index (OHI), which enable cross-sectional assessment of human, animal, and environmental health. This overlap suggests an emerging—though still incipient—conceptual convergence in the region.

The recent literature suggests that in Latin America, the One Health approach has been implemented primarily from a biomedical or epidemiological perspective, without effectively integrating the social or cultural determinants affecting food systems and human development. In this context, the 7S-Based Feeding framework could represent a valuable pathway for operationalizing One Health in more comprehensive food policies, as it enables visualization of how food practices, public health, and sustainability interconnect through a systemic approach.

It is important to clarify that while this review identifies the absence of an integrated analytical framework across existing studies, it contributes to the construction of such a framework by synthesizing commonalities between the One Health approach and the 7S-Based Feeding dimensions. This work does not claim to present a finalized model but offers a methodological foundation for future research seeking to integrate these perspectives more cohesively.

4.3. Which Gaps Exist in the Literature Regarding the Integration of 7S-Based Feeding into Public Policies?

Although certain dimensions such as Safe and Sustainable have been partially incorporated into food-related public policies in some Latin American countries, the comprehensive approach proposed by the 7S-Based Feeding model has yet to be explicitly or systematically adopted. This finding aligns with recent reviews highlighting the fragmentation of food policies in the region, which are often driven by reactive responses rather than intersectoral planning frameworks.

In countries such as Nicaragua and Brazil, significant efforts have been documented regarding food sovereignty and agroecology. However, these advances remain uneven and often fail to achieve institutional scaling. This review identifies a disconnect between academic progress and its translation into public policies, representing an opportunity to develop food governance frameworks that integrate participatory, territorial, and culturally adapted approaches—aligned with the principles of 7S-Based Feeding.

One of the most notable gaps identified in the reviewed literature is the absence of explicit incorporation of the 7S-Based Feeding framework as a comprehensive structuring model for public food policies. While several studies engage with individual dimensions of the framework, none apply it in an integrated manner to inform policy design.

And last but not least, the Satisfactory dimension is particularly absent, revealing a disconnect between institutional strategies and people’s everyday food experiences. Similarly, the Solidarity and Sovereign dimensions typically appear only in studies with strong normative approaches or within social movements, without being translated into established policies at state or regional levels.

The coding analysis not only captured thematic presence but also enabled the detection of gaps through the absence or limited occurrence of certain dimensions, particularly “Solidarity” and “Satisfaction.” Similarly, the infrequent integration of all three analytical axes—7S, One Health, and human development—signaled a fragmented academic landscape that lacks a unified approach. These patterns formed the basis for identifying gaps and recommendations for future research.

The communicational implications of this study are particularly relevant for the development of inclusive food policies and community-based interventions. For instance, the prevalence of the Social and Sovereignty dimensions in the reviewed literature suggests that community participation and advocacy are central to local food governance in Latin America. These dimensions provide strategic entry points for communication initiatives aimed at amplifying marginalized voices, documenting indigenous knowledge, and mobilizing collective actions for sustainable food systems. Such communicational strategies are essential for linking public health goals with culturally rooted practices and identities.

In summary, this article—based on an integrative review—offers a conceptual and methodological synthesis by combining the 7S-Based Feeding framework with the One Health approach, human development, and public health in the Latin American context. Although it does not present original empirical data, its strength lies in synthesizing existing evidence and revealing novel connections useful for future research and policymaking.

5. Conclusions

This integrative review demonstrates that 7S-Based Feeding constitutes an emerging model with high analytical potential for examining the relationships between food systems, public health, and human development, particularly in complex contexts such as Latin America. Throughout the analysis of the 18 selected articles, it was evidenced that the Sustainable, Healthy, Safe, and Social dimensions are the most frequently addressed, reflecting a current trend in the literature to prioritize aspects related to food safety, nutrition, climate change, and structural inequalities. Key findings of this review include the following:

- The Social dimension emerges as a pivotal element that links food systems with issues of equity and civic engagement. This position highlights its relevance as a social determinant of health within both the One Health and human development frameworks.

- The convergence of the One Health perspective with the 7S-Based Feeding framework becomes most evident in research that integrates sustainability, public health, and governance, reflecting a growing, though still evolving, trend toward intersectoral collaboration.

However, notable gaps were also identified. The Sovereign and Solidary dimensions receive less attention and are primarily addressed through normative or marginal approaches, while the Satisfactory dimension remains entirely absent. This omission underscores the need to incorporate the subjective, cultural, and emotional aspects of food systems into theoretical frameworks and public policy design. Similarly, integration between the One Health approach and 7S-Based Feeding remains at a preliminary stage, limiting opportunities to develop truly intersectoral and systemic interventions.

Methodologically, this study demonstrates that it is possible to establish a bridge between qualitative analysis, systematic coding, and data visualization to construct cross-cutting interpretations of complex phenomena. The adoption of tools such as ATLAS.ti and Sankey diagrams enabled the clear and well-founded identification of connection patterns, frequencies, and gaps, thereby adding substantial value to the interpretation process.

As a final contribution, this study highlights that adopting the 7S-Based Feeding model would not only enrich academic analysis but could also promote the formulation of fairer, more participatory, and sustainable food policies—particularly when combined with approaches such as One Health, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Human Development Index (HDI), and related frameworks.

Furthermore, the integration of 7S-Based Feeding with the One Health framework contributes a novel lens for advancing communication strategies in food systems. It encourages a shift toward relational, multisectoral communication practices that bridge the health-environment-development nexus. This communicational perspective not only enhances the applicability of the 7S framework but also responds directly to the urgent need for integrated strategies that support informed decision-making, knowledge democratization, and active citizenship in food system transformation.

Recognizing food systems as multidimensional phenomena, deeply interconnected with all aspects of human life, represents an essential step toward building more equitable, adaptable, and healthier societies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A.-A., M.S.H.-L. and J.F.G.-T.; methodology, B.A.-A., M.S.H.-L. and G.H.-R.; software, B.A.-A.; validation, M.S.H.-L., G.H.-R. and J.F.G.-T.; formal analysis, B.A.-A. and M.S.H.-L.; investigation, B.A.-A. and M.S.H.-L.; data curation, B.A.-A. and M.S.H.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A.-A. and M.S.H.-L.; writing—review and editing, M.S.H.-L., G.H.-R., J.F.G.-T., H.A.-B., A.R.-M. and J.R.-R.; visualization, M.S.H.-L. and J.R.-R.; supervision, M.S.H.-L. and J.R.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Urrialde de Andrés, R. Compuestos Bioactivos de Origen Vegetal. Nuevo Campo de Actuación en la Estrategia “One Health”; Ediciones Gráficas Rey, S.L., Ed.; Real Academia Europea de Doctores: Barcelona, Spain, 2023; pp. 31–35. Available online: https://raed.academy/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/libro-ingreso-Rafael-Urrialde-Compuestos-bioactivos-de-origen-vegetal-compr-v3.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Vento, S. Opinion: Medical education in many low- and middle-income countries needs urgent attention and serious improvement. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1548112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Guillén, E.; Ochoa-Díaz-López, H.; Castro-Quezada, I.; Irecta-Nájera, C.A.; Cruz, M.; Meneses, M.E.; Gurri, F.D.; Solís-Hernández, R.; García-Miranda, R. Intrauterine growth restriction and overweight, obesity, and stunting in adolescents of indigenous communities of Chiapas, Mexico. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Cajachagua-Torres, K.N.; Guzman-Vilca, W.C.; Quezada-Pinedo, H.G.; Tarazona-Meza, C.; Huicho, L. “National and subnational trends of birthweight in Peru: Pooled analysis of 2,927,761 births between 2012 and 2019 from the national birth registry. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2021, 1, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, W.; Melgar, P.; Garcés, A.; de Marquez, A.D.; Merino, G.; Siu, C. Overweight and obesity of school-age children in El Salvador according to two international systems: A population-based multilevel and spatial analysis. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo Gómez, K. Mapping obesity in women and chronic malnutrition in children across the municipalities of Bolivia: Spatial clusters and regionalization. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2024, 16, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-H.; Lee, S.A.; Lim, J.-Y.; Park, C.-Y. Effects of food price inflation on infant and child mortality in developing countries. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2016, 17, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, N.; Murray-Kolb, L.E.; Mitchell, D.C.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.; Na, M. Food Insecurity and Mental Well-Being in Immigrants: A Global Analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2022, 63, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, M.; Torres Carrasco, M.E.; Morales, D.; Kuritzky, A.; Abril-Ulloa, V.; Encalada, L. ‘Eating healthy’: Distrust of expert nutritional knowledge among elderly adults. Appetite 2021, 165, 105289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaconu, A.; Berti, P.R.; Cole, D.C.; Mercille, G.; Batal, M. Agroecology and nutritional health: A comparison of agroecological farmers and their neighbors in the Ecuadorian highlands. Food Policy 2021, 101, 102034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomich, T.P.; Lidder, P.; Coley, M.; Gollin, D.; Meinzen-Dick, R.; Webb, P.; Carberry, P. Food and agricultural innovation pathways for prosperity. Agric. Syst. 2019, 172, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, L. Science, truth and power. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2025, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D.R.; Barry, D.A. A One Health approach for South American hemorrhagic fevers. CABI One Health 2025, 0008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, J.A.; Alexander, M.; Chong, M.Y.C.; Link, H.M.; Pejchinovska, M.; Gazeley, U.; Ahmed, S.M.A.; Chou, D.; Moller, A.-B.; Simpson, D.; et al. Global and regional causes of maternal deaths 2009–2020: A WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2025, 13, e626–e634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, N.M.S.; Boschiero, M.N.; Marques, L.F.A.; Marson, F.A.L. The Oropouche fever in Latin America: A hidden threat and a possible cause of microcephaly due to vertical transmission. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1490252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, J.C. Medelacide: The intentional and systematic destruction of healthcare infrastructure. Glob. Soc. Chall. J. 2025, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakizimana, J.N.; Yona, C.; Makange, M.R.; Adamson, E.K.; Ntampaka, P.; Uwibambe, E.; Gasana, M.N.; Ndayisenga, F.; Nauwynck, H.; Misinzo, G. Complete genome analysis of the African swine fever virus genotypes II and IX responsible for the 2021 and 2023 outbreaks in Rwanda. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1532683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsnes, M.; Efstathiou, S.; Veine, S.; Loeng, M.; Alexandri, M.P.; De Grandis, G.; Sonetti, G. Losing control, learning to fail: Leveraging techniques from improvisational theatre for trust and collaboration in transdisciplinary research and education. Glob. Soc. Chall. J. 2025, 4, 129–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godek, W. Food sovereignty policies and the quest to democratize food system governance in Nicaragua. Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 38, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elver, H. Right to Food. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2023, 36, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingutia, R. Who is being left behind in water security, where do they live, and why are they left behind towards the achievement of the 2030 agenda? Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippidis, G.; Ferrer-Pérez, H.; Gracia-de-Rentería, P.; M’barek, R.; Sanjuán López, A.I. Eating your greens: A global sustainability assessment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanzo, J.; Rudie, C.; Sigman, I.; Grinspoon, S.; Benton, T.G.; Brown, M.E.; Covic, N.; Fitch, K.; Golden, C.D.; Grace, D.; et al. Sustainable food systems and nutrition in the 21st century: A report from the 22nd annual Harvard Nutrition Obesity Symposium. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, K.C.E.; Neto, J.C.; Aragon, D.C.; Antonini, S.R. Nutritional status and age at menarche in Amazonian students. J. Pediatr. 2024, 100, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, T.; Barling, D. Food security and food sustainability: Reformulating the debate. Geogr. J. 2012, 178, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellinger, N.; Kattelman, K.T. Domestic terrorism in the developing world: Role of food security. J. Int. Relat. Dev. 2021, 24, 306–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araújo Palmeira, P.; De Mattos, R.A.; Salles-Costa, R. Food security governance promoted by national government at the local level: A case study in Brazil. Food Sec. 2020, 12, 591–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moura, R.R.; de Castro, W.A.C.; Farinhas, J.H.; Pettan-Brewer, C.; Kmetiuk, L.B.; dos Santos, A.P.; Biondo, A.W. One Health Index (OHI) applied to Curitiba, the ninth-largest metropolitan area of Brazil, with concomitant assessment of animal, environmental, and human health indicators. One Health 2022, 14, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, R.; Tago, D.; Treich, N. Infectious Diseases and Meat Production. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 76, 1019–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.-Y.; Chen, F.-M.; Zhang, C.-S.; Zhou, Y.-B.; Li, T.-Y.; Qiang, N.; Zhang, X.-X.; Liu, J.-S.; Wang, S.-X.; Yang, X.-C.; et al. Assessing food security performance from the One Health concept: An evaluation tool based on the Global One Health Index. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2023, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, M.M.M.; De Almeida, A.M.; Willingham, A.L. An overview of food safety and bacterial foodborne zoonoses in food production animals in the Caribbean region. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2016, 48, 1095–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilber, I.; Bahena-Juárez, F.; Chiaia-Hernández, A.C.; Elgueta, S.; Escobar-Medina, A.; Friedrich, K.; González-Curbelo, M.Á.; Grob, Y.; Martín-Fleitas, M.; Miglioranza, K.S.B.; et al. Pesticides in soil, groundwater and food in Latin America as part of one health. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 14333–14345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Concepción, A.; Gil-Lacruz, A.; Saz-Gil, I.; Bazán-Monasterio, V. Social Well-Being for a Sustainable Future: The Influence of Trust in Big Business and Banks on Perceptions of Technological Development from a Life Satisfaction Perspective in Latin America. Sustainability 2022, 15, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlknecht, J.; González-Bravo, R. Measuring the Water-Energy-Food Nexus: The Case of Latin America and the Caribbean Region. Energy Procedia 2018, 153, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluf, R.S.; Burlandy, L.; Cintrão, R.P.; Jomalinis, E.; Carvalho, T.C.O.; Tribaldos, T. Sustainability, justice and equity in food systems: Ideas and proposals in dispute in Brazil. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2022, 45, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermid, S.S.; Hayek, M.; Jamieson, D.W.; Hale, G.; Kanter, D. Research needs for a food system transition. Clim. Change 2023, 176, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]