Barriers Experienced During Fatherhood and the Role of Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Mixed-Methods Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Research Team

2.4. Participant Recruitment

2.5. Data Collection and Data Management

2.5.1. Focus Groups

2.5.2. Survey Measures

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Thematic Analysis

2.6.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Main Themes and Subthemes in Barriers as Stated by the Father Participants

3.3. Limited Access to and Knowledge of Resources in the Community

3.3.1. Gaps in Mental Health Resources

3.3.2. Limited Opportunities for Skill Development, Job Readiness, and Getting Hired

3.3.3. Challenges in Navigating Justice System and Legal Aid

3.3.4. Challenges in Navigating Fatherhood Resources and Programs

3.3.5. Lack of Transportation

3.4. Challenges in Navigating New Roles, Resources, and Fatherhood Responsibilities

3.4.1. Safety of Environment

3.4.2. Separation from Child

3.4.3. Caregiving Responsibility

3.4.4. Financial Responsibility

3.4.5. Lack of Fatherhood Support/Disregard of Father’s Needs

3.4.6. Immigration Challenges

3.5. Important Values in Parenting

3.5.1. Leading Children Through Example, Education, and Communication

3.5.2. Engaging in Activities with Their Kids, Being Present, and Strengthening Family Unit

3.6. Survey Findings

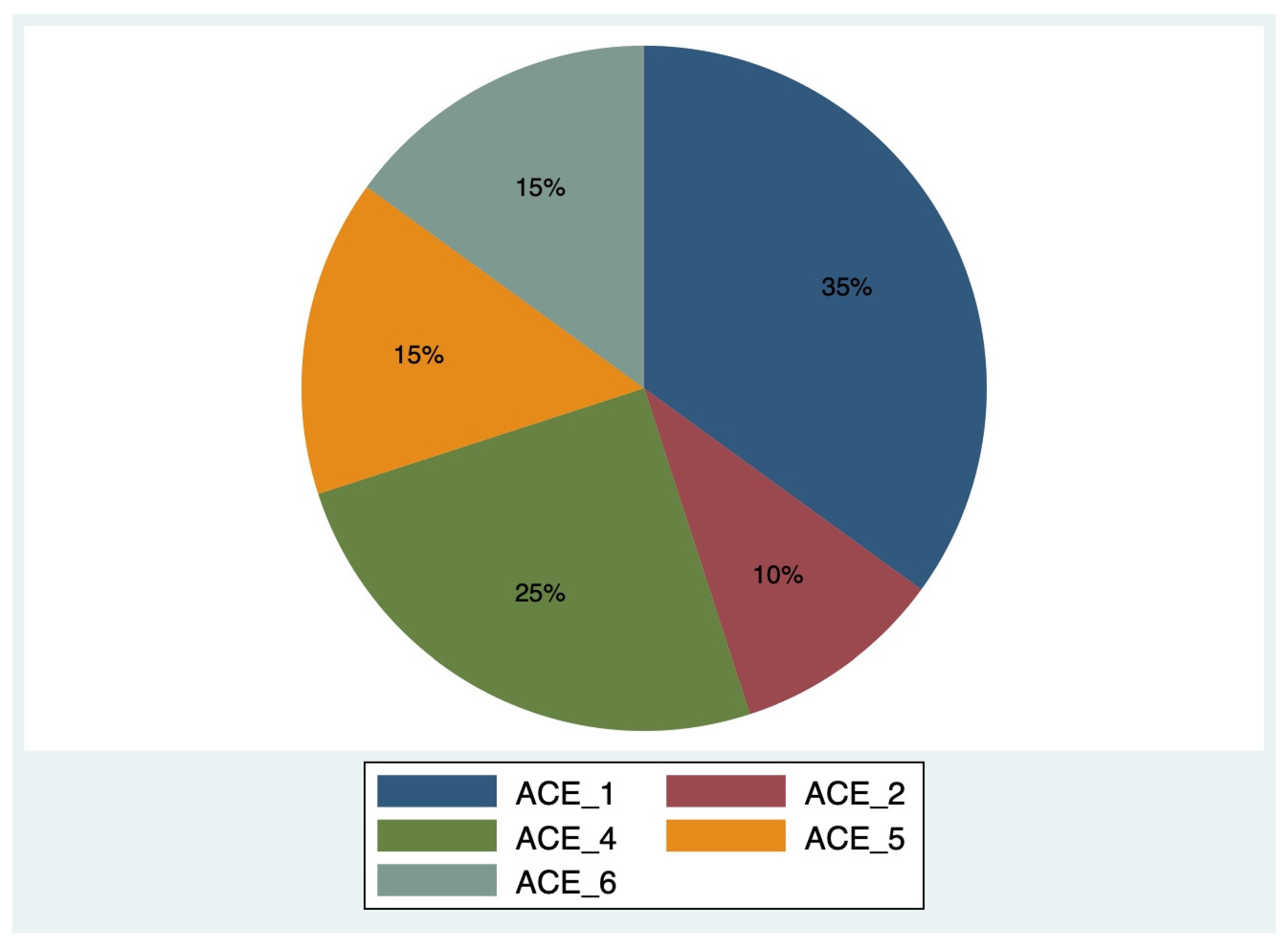

Prevalence of High ACE Scores in Fatherhood

3.7. Associations of Having a High ACE Score (>4) and Relevant Sociodemographic Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yogman, M.; Garfield, C.F.; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. Fathers’ roles in the care and development of their children: The role of pediatricians. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teitler, J.O. Father involvement, child health and maternal health behavior. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2001, 23, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkadi, A.; Kristiansson, R.; Oberklaid, F.; Bremberg, S. Fathers’ involvement and children’s developmental outcomes: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Acta Paediatr. 2008, 97, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rilling, J.K.; Hadley, C. A mixed methods study of the challenges and rewards of fatherhood in a diverse sample of US fathers. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 21582440231193939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, S.; Malone, M.; Sandall, J.; Bick, D. Mental health and wellbeing during the transition to fatherhood: A systematic review of first time fathers’ experiences: A systematic review of first time fathers’ experiences. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2018, 16, 2118–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, L.; DePriest, K.; Wilson, M.; Gross, D. Child poverty, toxic stress, and social determinants of health: Screening and care coordination. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2018, 23, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minkin, R.; Horowitz, J.M. 2. Race, Ethnicity and Parenting. Pew Research Center. 24 January 2023. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2023/01/24/race-ethnicity-and-parenting/ (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Cabrera, N.J.; Hofferth, S.L.; Chae, S. Patterns and predictors of father-infant engagement across race/ethnic groups. Early Child. Res. Q. 2011, 26, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Threlfall, J.M.; Seay, K.D.; Kohl, P.L. The parenting role of African American fathers in the context of urban poverty. J. Child. Poverty 2013, 19, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera, N.J.; Shannon, J.D.; West, J.; Brooks-Gunn, J. Parental interactions with Latino infants: Variation by country of origin and English proficiency. Child Dev. 2006, 77, 1190–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenry, P.C.; Price, S.J.; Fine, M.A.; Serovich, J. Predictors of single, noncustodial fathers’ physical involvement with their children. J. Genet. Psychol. 1992, 153, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mini, N.; Saltzman, F.; Simione, J.A. Expectant Fathers’ Social Determinants of Health in Early Pregnancy. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2020, 7, 2333794X20975628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, P.L.; Black, M.M. The effect of poverty on child development and educational outcomes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1136, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.H.; Corwyn, R.F. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 371–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, B.S.; Johnson, S.; Aqil, A.; Labrique, A.B.; Nelson, T.; Kc, A.; Carabas, Y.; Marcell, A.V. Promoting father involvement for child and family health. Acad. Pediatr. 2018, 18, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giano, Z.; Wheeler, D.L.; Hubach, R.D. The frequencies and disparities of adverse childhood experiences in the U.S. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fast Facts: Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences. 29 June 2023. Available online: https://www.fatherhood.gov/ (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Lyu, R.; Lu, S.; Ma, X. Group interventions for mental health and parenting in parents with adverse childhood experiences: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam. Relat. 2022, 72, 1806–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjothaug, T.; Smith, L.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Moe, V. Does fathers’ prenatal mental health bear a relationship to parenting stress at 6 months? Infant Ment. Health J. 2018, 39, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjothaug, T.; Smith, L.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Moe, V. Prospective fathers’ adverse childhood experiences, pregnancy-related anxiety, and depression during pregnancy: Prospective fathers’ adverse childhood experiences. Infant Ment. Health J. 2015, 36, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szepsenwol, O.; Simpson, J.A.; Griskevicius, V.; Raby, K.L. The effect of unpredictable early childhood environments on parenting in adulthood. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 1045–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.C.; Klein, C.C.; Barnett, M.L.; Schatz, N.K.; Garoosi, T.; Chacko, A.; Fabiano, G.A. Intervention and implementation characteristics to enhance father engagement: A systematic review of parenting interventions. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 26, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About Us. Fatherhood.gov. Available online: https://www.fatherhood.gov/ (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Find Services for Fathers and Families. Hhs.gov. 29 June 2023. Available online: https://acf.gov/css/outreach-material/find-services-fathers-and-families (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Palm Beach County Community Health Assessment Palm Beach County, Florida. Available online: https://palmbeach.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/community-health-planning-and-statistics/ (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Palm Beach County, Florida. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/palmbeachcountyflorida/PST045224 (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Healthy Mothers Healthy Babies Coalition of Palm Beach County, Inc.; Healthy Mothers Healthy Babies Coalition of Palm Beach County, Inc. 2019. Available online: https://www.hmhbpbc.org/ (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- ACEs Aware. Adverse Childhood Experience Questionnaire for Adults. California Surgeon General’s Clinical Advisory Committee. 2020. Available online: https://www.acesaware.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/ACE-Questionnaire-for-Adults-Identified-English-rev.7.26.22.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Biaggi, A.; Conroy, S.; Pawlby, S.; Pariante, C.M. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurgescu, C.; Misra, D.P. Psychosocial Factors and Preterm Birth Among Black Mothers and Fathers. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2018, 43, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, M.; Misra, D. The impact of a father’s adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) on the relationship he has with the mother of his baby. Scientia 2021, 2021, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pediatric ACE Screening Clinical Workflow. Available online: https://www.acesaware.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ACEs-Clinical-Algorithms-Workflows-and-ACEs-Associated-Health-Conditions.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englar-Carlson, M.; Kiselica, M.S. Affirming the strengths in men: A positive masculinity approach to assisting male clients. J. Couns. Dev. 2013, 91, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaleiha, A.; Barber, C.; Tamatea, A.J.; Bird, A. Fathers’ help seeking behavior and attitudes during their transition to parenthood. Infant Ment. Health J. 2022, 43, 756–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowell, T.; Neal-Barnett, A. A systematic review of the effect of parental adverse childhood experiences on parenting and child psychopathology. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2022, 15, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.A.; Howard, D.; Rayford, B.S.; Gordon, D.M. Fathers matter: Involving and engaging fathers in the child welfare system process. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 53, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.M.; Merrick, M.T.; Houry, D.E. Identifying and preventing adverse childhood experiences: Implications for clinical practice: Implications for clinical practice. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 323, 25–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKelvey, L.M.; Whiteside-Mansell, L.; Conners-Burrow, N.A.; Swindle, T.; Fitzgerald, S. Assessing adverse experiences from infancy through early childhood in home visiting programs. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 51, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahlschmidt, M.J.; Threlfall, J.; Seay, K.D.; Lewis, E.M.; Kohl, P.L. Recruiting fathers to parenting programs: Advice from dads and fatherhood program providers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2013, 35, 1734–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.C.; Randell, K.A.; Dowd, M.D. Addressing Parental ACEs in the Pediatric Setting. Adv. Pediatr. 2021, 68, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.S.; Hays-Grudo, J.; Zapata, M.I.; Treat, A.; Kerr, K.L. Adverse and protective childhood experiences and parenting attitudes: The role of cumulative protection in understanding resilience. Advers. Resil. Sci. 2021, 2, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlin, S.L.; Champine, R.B.; Strambler, M.J. A Community’s Response to Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Building a Resilient, Trauma-Informed Community. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 64, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Collman, G.W. Evolving partnerships in community. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 1814–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronte-Tinkew, J.; Burkhauser, M.; Metz, A.J.R. Elements of promising practices in fatherhood programs: Evidence-based research findings on interventions for fathers. Fathering 2012, 10, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Characteristics (n = 61) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |

| Age (n = 61) | ||

| 18–24 | 7 | 11.48 |

| 25–34 | 26 | 42.62 |

| 35–44 | 21 | 34.43 |

| 45–54 | 4 | 6.56 |

| 55–64 | 3 | 4.92 |

| Ethnicity (n = 59) | ||

| Black-African American | 37 | 62.71 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 11 | 18.64 |

| White Caucasian | 5 | 8.47 |

| Black and Asian or Pacific Islander | 2 | 3.39 |

| Black or Native American or American Indian | 1 | 1.69 |

| White and Hispanic | 1 | 1.69 |

| Black and Hispanic | 2 | 3.39 |

| Marital Status (n = 60) | ||

| Single/Never Married | 13 | 21.67 |

| Married | 33 | 55.00 |

| In a relationship | 11 | 18.33 |

| Divorced | 2 | 3.33 |

| Widowed | 1 | 1.67 |

| Employment Status (n = 60) | ||

| Working for wages | 29 | 48.33 |

| Unemployed but actively looking for a job | 11 | 18.33 |

| Unemployed but not actively looking for a job | 6 | 10.00 |

| Self-employed | 8 | 13.33 |

| Unable to work | 4 | 6.67 |

| Student | 1 | 1.67 |

| Homemaker | 1 | 1.67 |

| Annual Income (n = 59) (USD) | ||

| <25,000 | 18 | 30.51 |

| 25,000–50,000 | 17 | 28.81 |

| 50,000–100,000 | 5 | 8.47 |

| >100,000 | 3 | 5.08 |

| Prefer not to say | 16 | 27.12 |

| Number of Children (n = 57) | ||

| 0 | 5 | 8.77 |

| 1 | 19 | 33.33 |

| 2 | 15 | 26.32 |

| 3 | 10 | 17.54 |

| 4 | 4 | 7.02 |

| 7 | 2 | 3.51 |

| 11 | 2 | 3.51 |

| Education Level (n = 59) | ||

| Less than a High School Degree | 10 | 16.95 |

| High School Graduate | 33 | 55.93 |

| College Graduate | 12 | 20.34 |

| Post-Graduate | 4 | 6.78 |

| Barriers to Being Involved in Child’s Life (n = 60) | ||

| Yes | 25 | 41.67 |

| No | 35 | 58.33 |

| Barrier Category (n = 48) | ||

| Work | 17 | 35.42 |

| Lack of transportation | 6 | 12.50 |

| Substance use | 1 | 2.08 |

| Relationship with mother of child | 2 | 4.17 |

| Difficulty with parenting skills | 1 | 2.08 |

| Work/Other barriers | 4 | 8.33 |

| Physical distance/Work/Relationship with mother of child | 1 | 2.08 |

| Physical distance/Relationship with mother of child | 1 | 2.08 |

| Physical distance/Substance use | 1 | 2.08 |

| Physical distance/Other barriers | 1 | 2.08 |

| Relationship with mother of child/Difficulty with parenting skills | 1 | 2.08 |

| Relationship with mother of child/Other | 1 | 2.08 |

| Other | 11 | 22.92 |

| Variables | Categories | ACE Score (n; %) | p-Values Based on the Fisher’s Exact Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE Score Low (<=4) n = 40, 65.6% n (%) | ACE Score High (>4) n = 21, 34.4% n (%) | |||

| Age | 18–24 | 5 (12.5) | 2 (9.5) | 0.573 |

| 25–34 | 18 (45) | 8 (38.1) | ||

| 35–44 | 11 (27.5) | 10 (47.6) | ||

| 45–54 | 3 (7.5) | 1 (4.8) | ||

| 55–64 | 3 (7.5) | 0 (0) | ||

| Ethnicity | Black-African American | 23 (57.5) | 14 (66.7) | 0.906 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 8 (20) | 3 (14.3) | ||

| White Caucasian | 4 (10) | 1 (4.8) | ||

| Black and Asian or Pacific Islander | 1 (2.5) | 1 (4.8) | ||

| Black or Native American or American Indian | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | ||

| White and Hispanic | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | ||

| Black and Hispanic | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | ||

| Marital Status | Single, never been married | 7 (17.5) | 6 (28.6) | 0.056 |

| Married | 26 (65) | 7 (33.3) | ||

| In a relationship | 6 (15) | 5 (23.8) | ||

| Divorced | 0 (0) | 2 (9.5) | ||

| Widowed | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | ||

| Education | Less than a high school degree (ref) | 6 (15) | 4 (19) | 0.869 |

| High school graduate | 22 (55) | 11 (52.4) | ||

| College graduate | 9 (22.5) | 3 (14.3) | ||

| Postgraduate | 2 (5) | 2 (9.5) | ||

| Annual Income (USD) | <25,000 (ref) | 11 (27.5) | 7 (33.3) | 0.942 |

| 25,000–50,000 | 12 (30) | 5 (23.8) | ||

| 50,000–100,000 | 4 (10) | 1 (4.8) | ||

| >100,000 | 2 (5) | 1 (4.8) | ||

| Prefer not to say | 10 (25) | 6 (28.6) | ||

| Number of Children | 0 | 5 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 0.664 |

| 1 | 13 (32.5) | 6 (28.6) | ||

| 2 | 9 (22.5) | 6 (28.6) | ||

| 3 | 6 (15) | 4 (19) | ||

| 4 | 3 (7.5) | 1 (4.8) | ||

| 7 | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | ||

| 11 | 1 (2.5) | 1 (4.8) | ||

| Barriers to Being Involved in Child’s Life | No | 28 (70) | 7 (33.3) | 0.013 * |

| Yes | 12 (30) | 13 (61.9) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gurivireddygari, S.; Hicks, S.; Hayes, E.; Rao, M.; Densley, S.; Choudhury, S.; Kitsantas, P.; Mejia, M.; Sacca, L. Barriers Experienced During Fatherhood and the Role of Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Societies 2025, 15, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060162

Gurivireddygari S, Hicks S, Hayes E, Rao M, Densley S, Choudhury S, Kitsantas P, Mejia M, Sacca L. Barriers Experienced During Fatherhood and the Role of Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Societies. 2025; 15(6):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060162

Chicago/Turabian StyleGurivireddygari, Sravya, Samantha Hicks, Elisabeth Hayes, Meera Rao, Sebastian Densley, Sumaita Choudhury, Panagiota Kitsantas, Maria Mejia, and Lea Sacca. 2025. "Barriers Experienced During Fatherhood and the Role of Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Mixed-Methods Approach" Societies 15, no. 6: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060162

APA StyleGurivireddygari, S., Hicks, S., Hayes, E., Rao, M., Densley, S., Choudhury, S., Kitsantas, P., Mejia, M., & Sacca, L. (2025). Barriers Experienced During Fatherhood and the Role of Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Societies, 15(6), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060162