1. Introduction

Rural education represents one of the most significant challenges for Colombia’s social and economic development, evidencing persistent gaps that affect the quality and accessibility of the educational system. Despite the multiple policies and initiatives implemented by the national government, disparities between urban and rural education continue to be pronounced, reflecting the complexity of addressing the specific needs of rural communities [

1,

2]. This situation not only compromises the individual development of students but also perpetuates cycles of inequality that affect the progress of entire regions.

The current landscape of rural education in Colombia is characterized by interrelated structural challenges: deficient school infrastructure, scarcity of pedagogical resources, limited availability of qualified teachers, and curricula poorly adapted to local realities. These factors, combined with geographic, social, and economic barriers, create an educational ecosystem that hinders the achievement of equitable outcomes. The implementation of the National Rural Education Plan, although representing a significant effort to address these issues, has shown heterogeneous results that demonstrate the need for more contextualized and sustainable interventions [

3,

4,

5].

It is important to recognize that the Colombian context presents institutional particularities that require analytical differentiation regarding rural education. While it is true that cultural and linguistic diversity constitutes a central element in Colombian rural territories, most indigenous communities have their own Indigenous Educational System (SEIP), supported by specific regulations that recognize the autonomy of each people to establish their educational guidelines. According to the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia [

6], 102 indigenous peoples coexist in the country, maintaining 65 native languages.

This multi-ethnic and plurilingual reality operates under an educational system parallel to the regular national system, which implies that, although the SEIP shares some problems with general rural education—such as infrastructure limitations, teacher training, and resources—it operates under completely different normative, curricular, and governance frameworks that respond to specific cosmogonies, epistemologies, and political-educational projects of each people. Thus, the SEIP has its own educational authorities, pedagogical methodologies, and evaluation mechanisms that differ substantially from national educational policies. The foregoing, combined with the researchers’ experience as researchers, teachers, and educational administrators in rural areas, makes this study focus on the analysis of educational quality policies for rural communities that operate within the regular national educational system, differentiating itself from the specialized analysis that the SEIP would deserve as an autonomous system of indigenous education with its own institutionality and reference frameworks. This delimitation of the study does not seek to exclude indigenous educational realities, but rather to respect the autonomy of these communities, who deserve a specialized analysis that recognizes the complexity of their own systems and avoids external impositions of conceptual frameworks that do not correspond to their realities.

In this context, it becomes essential to develop an in-depth analysis that allows for understanding not only the current challenges but also the opportunities for transformation within the rural educational system. The present study examines: What are the factors that influence rural educational quality policies in Colombia? The findings reveal a significant disconnection between policies formulated at the national level and their contextualized implementation in rural territories. It is also identified that factors such as sustainable financing, intersectoral articulation, and urban–rural gaps emerge as the main determinants of the effectiveness of these educational interventions.

The analysis focuses on three fundamental axes: curricular adaptation to local contexts, strengthening teacher training, and strategic integration of educational technologies, seeking to contribute to the development of more effective and equitable policies [

7,

8,

9]. Through a qualitative methodological approach based on Grounded Theory and rigorous theoretical triangulation, this study identifies that the success of rural educational policies crucially depends on their adaptability to local sociocultural realities and the active participation of communities in their design and implementation.

The relevance of this research lies in its potential to inform the design and implementation of educational policies that effectively respond to the specific needs of rural communities. By examining both obstacles and successful experiences, this analysis provides evidence pointing toward the need for a significant reorientation of educational policies. The conclusions indicate the importance of prioritizing the design of genuinely rural educational policies, not adaptations of urban models, contextualized teacher training, sustained investment in appropriate infrastructure, and the development of evaluation and implementation mechanisms that recognize and value the particularities of the Colombian rural context.

1.1. Rural Education: International Experiences and Lessons

Analysis of the rural education situation at a global level reveals shared patterns and challenges that transcend geographical boundaries and cultural contexts. Biddle et al. [

10] have identified that, despite advances in rural educational research, significant gaps persist in areas such as equity, access, and educational quality globally, reflecting the need to rethink educational policies from a perspective that recognizes the particularities of the rural environment.

In China, although rural educational policies have contributed to poverty reduction through targeted programs [

11], Li and Xue [

12] note that the system still faces significant challenges in ensuring high-quality education in rural areas. These challenges are particularly manifested in the inequitable distribution of educational resources between regions and the difficulty in retaining qualified teachers in remote areas, perpetuating cycles of educational inequality. In India, the situation reflects similar patterns: the New National Education Policy (NEP) has succeeded in improving initial access to education, but Rangarajan et al. [

13] warn that teaching–learning conditions and educational outcomes remain concerning in remote rural areas, where the lack of adequate infrastructure and pedagogical resources significantly limits educational quality.

In the European context, research in Germany reveals that maintaining stable patterns of educational quality in rural environments requires continuous efforts and significant resources, directly impacting the development and learning of rural students [

14]. This situation is complicated by the need to constantly adapt educational programs to changing populations and limited resources. Glass [

15], in his report for the Council of Europe, highlights that, despite the active role of local and regional authorities, challenges in retaining young people in rural areas persist, partly due to the perception of limited opportunities and the lack of connection between education and local development prospects. Spain presents a particular case where, although significant advances have been made in the integration of educational technologies, Moraleda-Ruano and Bernal-Romero [

16] identify persistent challenges in the sustainability of rural schools and in attracting qualified teaching staff, affecting the continuity and quality of educational programs.

The situation in sub-Saharan Africa reveals even more pronounced and structural challenges. Sugata and Keisuke [

17] identify critical gaps in educational performance between urban and rural areas, manifested not only in academic results but also in dropout rates and school progression. These disparities are exacerbated by limited access to basic resources, deficient infrastructure, and a chronic shortage of trained teachers, creating a cycle of educational disadvantage. In Tanzania, Lindsjö [

18] documents how these disparities significantly affect rural educational quality, especially impacting the development of basic skills and learning opportunities. The situation in Zimbabwe, according to Makachira and Muchabaiwa [

19], reveals a profound crisis in the quality of multigrade education in satellite schools, where the lack of resources, inadequate training, and absence of pedagogical support seriously compromise the effectiveness of these educational programs.

In Latin America, Mora [

20] identifies a persistent pattern of structural challenges in rural areas that goes beyond the simple lack of resources. Inadequate infrastructure, combined with limitations in teacher training and curricula with limited relevance to the rural context, creates significant barriers to effective learning. These obstacles are magnified by the socioeconomic and geographical conditions of the region, generating a cycle of educational inequality that is transmitted across generations and limits opportunities for personal and community development.

Recent experiences show that in northern Norway, despite the rich ethnic diversity of Sámi, Kven, and Norwegian populations, educational systems maintain uniform curricula that ignore this cultural diversity, demonstrating that rurality represents vibrant societies with contrasts and not homogeneous spaces [

21]. Along the same lines, the Australian longitudinal analysis shows, after examining more than 500 academic contributions over three decades, the persistence of nine perennial themes: insufficient financing, difficulties in teacher preparation and retention, curricular disconnection with local realities, deficit discourses about rurality, systemic inequities, and disconnection between school, family, and community [

22]. On the other hand, in Ghana, the implementation of policies such as free secondary education, school feeding programs, and the physical expansion of educational institutions to remote communities significantly improved school participation rates, revealing that the central problem does not lie in “being rural” but in marginalization processes that devalue rural cultural capital [

23].

Through these diverse contexts, common patterns emerge that require urgent attention and sustainable solutions: the need to strengthen basic educational infrastructure, improve teacher training and retention programs, adapt curricula to local realities, and ensure sustainable financing for rural educational programs. These shared challenges suggest the importance of developing educational policies that not only recognize the particularities of each context but also address the structural barriers that limit educational quality in rural environments, promoting a comprehensive approach that considers both immediate needs and long-term development aspirations of rural communities.

1.2. Panorama of Rural Education in Colombia

The research problem under investigation is situated within Colombia’s rural educational system, which faces a series of critical challenges that have affected the quality and accessibility of secondary education in these areas. According to the National Department of Statistics (DANE), as of 2023, there are 13,631,928 school-age individuals in Colombia, with approximately 26.7% residing in rural areas.

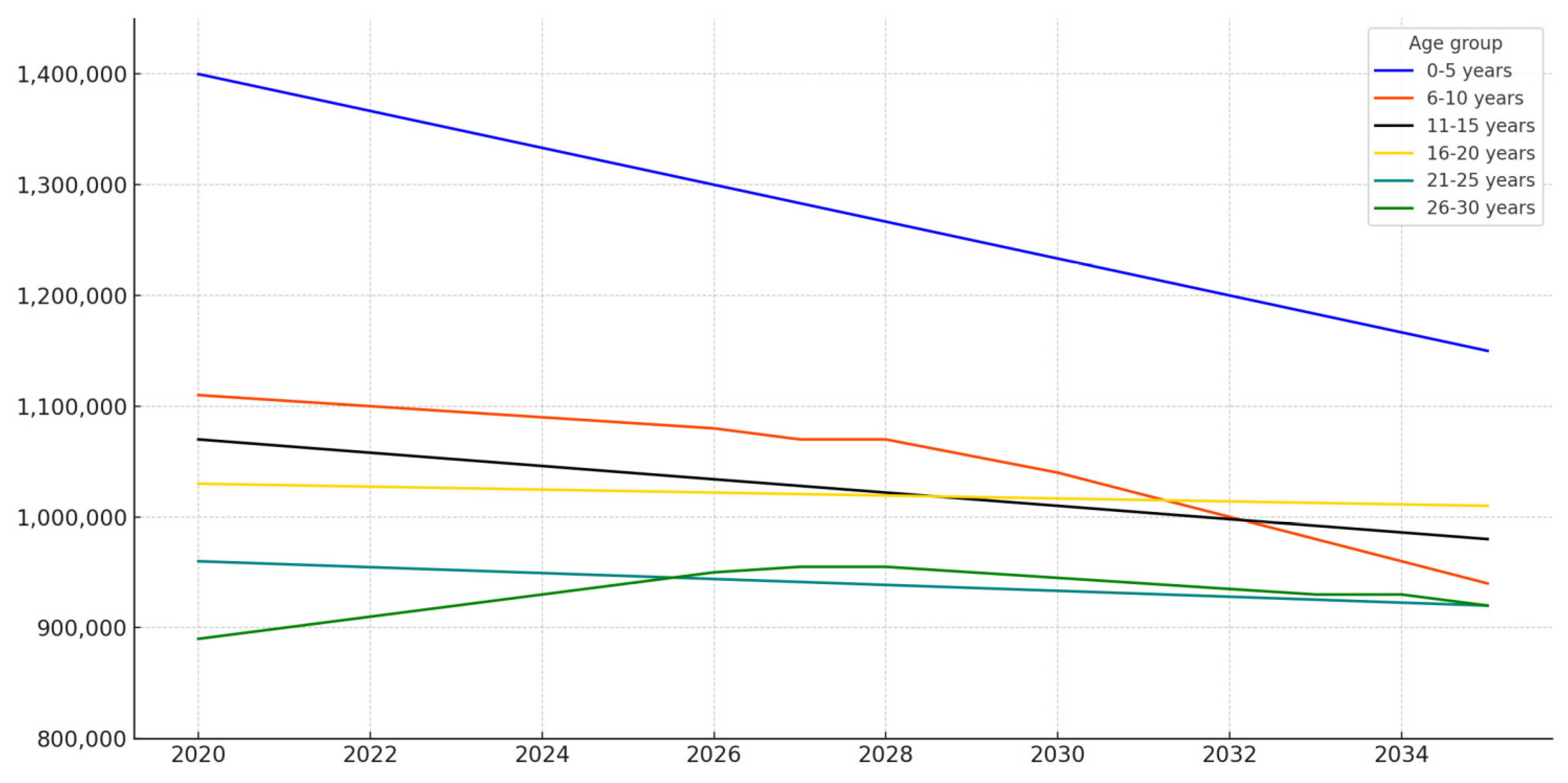

According to Statistical Analysis Report LEE No. 98, dated 9 July 2024 of the 55,889 educational institutions in Colombia, 67% are rural with a predominant orientation toward morning sessions (76%). Additionally, a progressive decrease in rural student population is projected, as shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1 below shows the population projections in rural areas for young population groups in Colombia, illustrating the anticipated demographic changes through 2035. The graph depicts a progressive decrease in rural youth population across different age categories, highlighting a significant demographic trend that has important implications for educational planning and policy development in rural regions.

According to the National Quality of Life Survey (ECV) conducted by DANE in 2022, Colombia’s population aged 15 years and older amounted to 39,839,574 individuals. Of this total, 95.9% were literate. However, marked geographical disparities are observed: 2.7% of the urban population aged 15 years and older lacked reading and writing skills, compared to 9.2% in rural areas.

Despite efforts made by the government through policies such as the National Rural Education Plan, inequalities between rural and urban areas persist. Challenges include inadequate infrastructure, scarcity of educational and technological resources, and limited availability of trained teachers. These structural problems significantly restrict educational opportunities for rural students, perpetuating social and economic inequality in the country [

20,

24,

25].

Furthermore, current educational policies have failed to close the gap in academic performance and school retention between rural and urban students. Standardized assessments, such as the SABER tests, show that students in rural areas continue to lag behind their urban counterparts. This situation is exacerbated by the lack of a curriculum adapted to local realities and needs, which hinders the relevance and effectiveness of education provided in these communities [

26,

27,

28]. A more comprehensive and contextualized approach is necessary in the formulation and implementation of public policies that respond to the cultural, social, and economic particularities of rural areas to improve the quality and equity of education in Colombia.

In recent years, rural education in Colombia has been the subject of analysis and debate due to persistent inequalities compared to urban areas. Policies implemented to improve educational quality in rural areas have shown mixed results, highlighting the need for greater contextualization and adaptation of educational strategies. Recent studies have identified that inadequate infrastructure and limited availability of educational resources are key factors that continue to affect access to and quality of education in the country’s rural areas [

24,

25]. Additionally, socioeconomic and geographical barriers continue to perpetuate educational inequality, underscoring the need for more inclusive policies adapted to local realities [

29,

30].

Directive management in rural educational institutions has also been a central topic in the discussion on improving educational quality. Recent research has suggested that directive leadership plays a crucial role in the effective implementation of educational policies and in creating more equitable and effective learning environments. However, there is a significant gap in training and support for administrators in rural areas, limiting their capacity to address the specific challenges of these contexts [

3,

31]. This lack of adequate training and resources for rural educational leaders directly affects the quality of teaching and, ultimately, the academic performance of students, reinforcing the need to strengthen directive management in these areas.

Moreover, the use of educational technologies has been identified as a potentially transformative tool for improving education in rural areas. Although the integration of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in rural schools has been promoted as a solution to overcome resource and access limitations, implementation has been uneven. Recent research highlights the importance of providing specific training and technological resources adapted to rural needs to maximize the impact of these technologies [

2,

32]. Despite advances in this area, it is evident that sustained efforts are required to ensure that ICT can truly close the educational gaps between rural and urban areas in Colombia.

1.3. Legal and Policy Framework for Colombian Rural Education

Education in Colombia’s rural areas has been a focus of public policy, particularly through the efforts of the Ministry of National Education (MEN) to improve educational quality and reduce disparities between rural and urban areas. The MEN’s public policy has been oriented toward creating strategies that seek to guarantee inclusive and equitable education throughout the country, emphasizing the importance of school infrastructure, teacher training, and the relevance of educational curricula for rural communities [

33]. However, the outcomes of these policies have been mixed, as rural areas continue to face significant challenges in terms of educational access and quality [

1].

Educational quality in rural contexts has been a central theme on the agenda of both the MEN and international organizations such as UNESCO. According to UNESCO, educational quality is measured not only by academic performance but also by the capacity of schools to provide a safe, inclusive, and equitable learning environment [

34]. In Colombia, the Synthetic Index of Educational Quality (ISCE) has been used as a tool to evaluate educational quality across various regions, including rural areas. Nevertheless, the gaps in educational quality between rural and urban zones remain notable, indicating the need for a more comprehensive approach adapted to the particularities of these communities [

25].

Directive management plays a crucial role in the effective implementation of educational policies and in improving educational quality in rural schools. Cassasus [

35] emphasizes that effective directive leadership is essential for creating learning environments that promote equity and educational quality. In Colombia’s rural schools, directive management faces particular challenges due to resource scarcity, limited specialized training, and the need to adapt to unique geographical and sociocultural contexts [

3]. Despite these challenges, it has been demonstrated that strong directive management can significantly improve academic performance and school retention in rural areas [

35].

Furthermore, the integration of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in rural schools has been promoted as a strategy to overcome resource limitations and improve educational quality. However, ICT implementation in rural areas has been uneven, and its impact largely depends on the capacity of school administrators to effectively manage these resources and ensure they are used in ways that benefit all students [

2,

32]. To maximize the impact of ICT, it is necessary to provide specific training to rural administrators and teachers, as well as adapt technologies to local needs and contexts [

33].

The legal framework governing rural education in Colombia is grounded in the Political Constitution of 1991, which establishes education as a fundamental right and a public service with a social function. In this context, the General Education Law (Law 115 of 1994) establishes general guidelines for organizing the Colombian educational system, including specific provisions to guarantee coverage and quality of education in rural areas. This law underscores the State’s obligation to provide necessary resources to ensure inclusive and equitable education, adapted to the geographical and cultural particularities of rural communities [

33].

Additionally, Decree 3011 of 1997, which regulates the provision of educational services in rural and dispersed areas, reinforces the State’s commitment to rural education. This decree establishes that educational institutions in rural areas must have curricular programs adapted to local conditions, including cultural, productive, and environmental aspects. It also emphasizes the importance of community participation in school management, promoting community integration in decision-making related to education, which is fundamental to ensuring that education is relevant and meaningful for students in these contexts [

33,

34].

At the international level, Colombia has committed to following the guidelines of UNESCO and other international organizations that promote inclusive and equitable education. This includes compliance with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically SDG 4, which seeks to ensure inclusive, equitable, and quality education for all. The Colombian legal framework, in line with these international commitments, has developed specific policies and programs to improve educational quality in rural areas, although challenges persist in the effective implementation of these policies, especially with regard to equity and directive management in rural schools [

3,

35].

2. Materials and Methods

To respond to the research question, “What are the factors that influence rural educational quality policies in Colombia?”, this study utilized a qualitative approach based on Grounded Theory, enabling the generation of emergent theory from the analysis of qualitative data related to educational public policies. This approach, grounded in the works of Glaser and Strauss [

36], as well as the methodological developments of Strauss and Corbin [

37] and Charmaz [

38], was structured in three main phases:

Open coding: Initial identification of key concepts present in the collected data, highlighting recurrent patterns and preliminary relationships.

Axial coding: Deepening the relationships between main categories and subcategories, facilitating the construction of robust theoretical connections.

Selective coding: Integration of categories and subcategories into a coherent theoretical narrative, focused on critical factors that influence rural educational quality policies.

To strengthen the validity and depth of the analysis of educational quality policies in Colombia’s rural areas, theoretical triangulation was employed as a methodological strategy. According to Flick [

39], triangulation consists of “the combination of different methods, study groups, local and temporal settings, and distinct theoretical perspectives to address a phenomenon” (p. 67), allowing for a deeper and more complete understanding of the object of study. In this sense, triangulation was structured from three complementary approaches that permitted a more comprehensive interpretation of the phenomenon under study:

Educational public policy approach: normative documents and programs implemented in Colombia were analyzed, comparing them with international models of rural education proposed by various organizations [

34,

40].

Sociocultural perspective of rural education: concepts of contextualized education, cultural relevance, and community participation were incorporated to evaluate how current policies respond to local realities [

2,

20,

35,

41].

Educational quality model in rural contexts: a multidimensional educational quality model was used that defines quality as an integral construct that transcends traditional academic performance indicators to incorporate criteria of cultural relevance, territorial equity, and contextualized development, based on the theories of [

3,

25,

30,

42].

The application of theoretical triangulation allowed not only for contrasting different interpretations of the data but also for comparing sources and identifying emerging patterns in the relationship between design, implementation, and sustainability of educational policies in rural areas. As Denzin [

43] points out, triangulation strengthens the credibility of findings by reducing interpretative biases that could arise from an analysis based on a single perspective.

Along the same lines, qualitative data management was developed using ATLAS.ti software version 25 (the latest version available), which allowed for organizing, coding, and analyzing large volumes of information systematically. As highlighted by Friese [

44] and Saldaña [

45], the use of digital tools such as ATLAS.ti facilitates transparent and reproducible analysis, ensuring methodological rigor in qualitative research.

The data corpus included key documents of national and international public policies, official reports (such as those published by DANE and the Ministry of National Education), and relevant academic literature (see

Table 1). This methodological approach was iterative and dynamic, allowing for adjustments during the analysis process as relevant categories emerged. Contextual validity of the findings was prioritized through data triangulation based on a frequency analysis of codes in the 34 reviewed documents. This process allowed for organizing and classifying the data, highlighting the most relevant and recurrent themes to better understand the analyzed reality.

The inclusion criteria for document selection were: (a) publications related to rural education in Colombia or Latin America, (b) academic articles published between 2012 and 2024 to ensure currency of information, (c) texts that specifically addressed educational policies, educational quality, or management in rural contexts, (d) availability of complete access to the document, and (e) direct relevance to the Colombian regular national educational system. On the other hand, exclusion criteria included: (a) documents that focused exclusively on urban education, (b) academic articles prior to 2012 to maintain temporal relevance, (c) texts that dealt only with technical or administrative aspects without connection to quality policies, (d) restricted access or incomplete documents, (e) materials that addressed exclusively the Indigenous Educational System (SEIP) due to its differentiated normative and operational framework, and (f) duplicate publications or preliminary versions of documents already included. The search was conducted in academic databases (Scopus, Web of Science, SciELO) and institutional repositories of the Ministry of National Education, DANE, UNESCO, OEI, and FAO. The temporal limitation (2012–2024) was applied only to academic articles, while official governmental documents were included regardless of their publication year given that they maintain normative and operational validity.

Finally, since this research was based on documentary analysis of available public sources, institutional ethics committee approval was not required. However, the study followed ethical principles of documentary research [

46,

47], including appropriate citation of all consulted sources, responsible use of public information, and respect for the copyright of the analyzed documents.

3. Results

Analysis identified that educational quality policies implemented in Colombia’s rural areas during the last decade have faced significant challenges related to inadequate infrastructure, lack of trained human resources, and limited adaptation of curricula to local needs. Additionally, it was observed that the limited incorporation of educational technologies has perpetuated digital and social gaps, negatively affecting equity and educational quality in these contexts. To deepen the understanding of these issues and their interrelationships, a systematic analysis of available documentation was conducted.

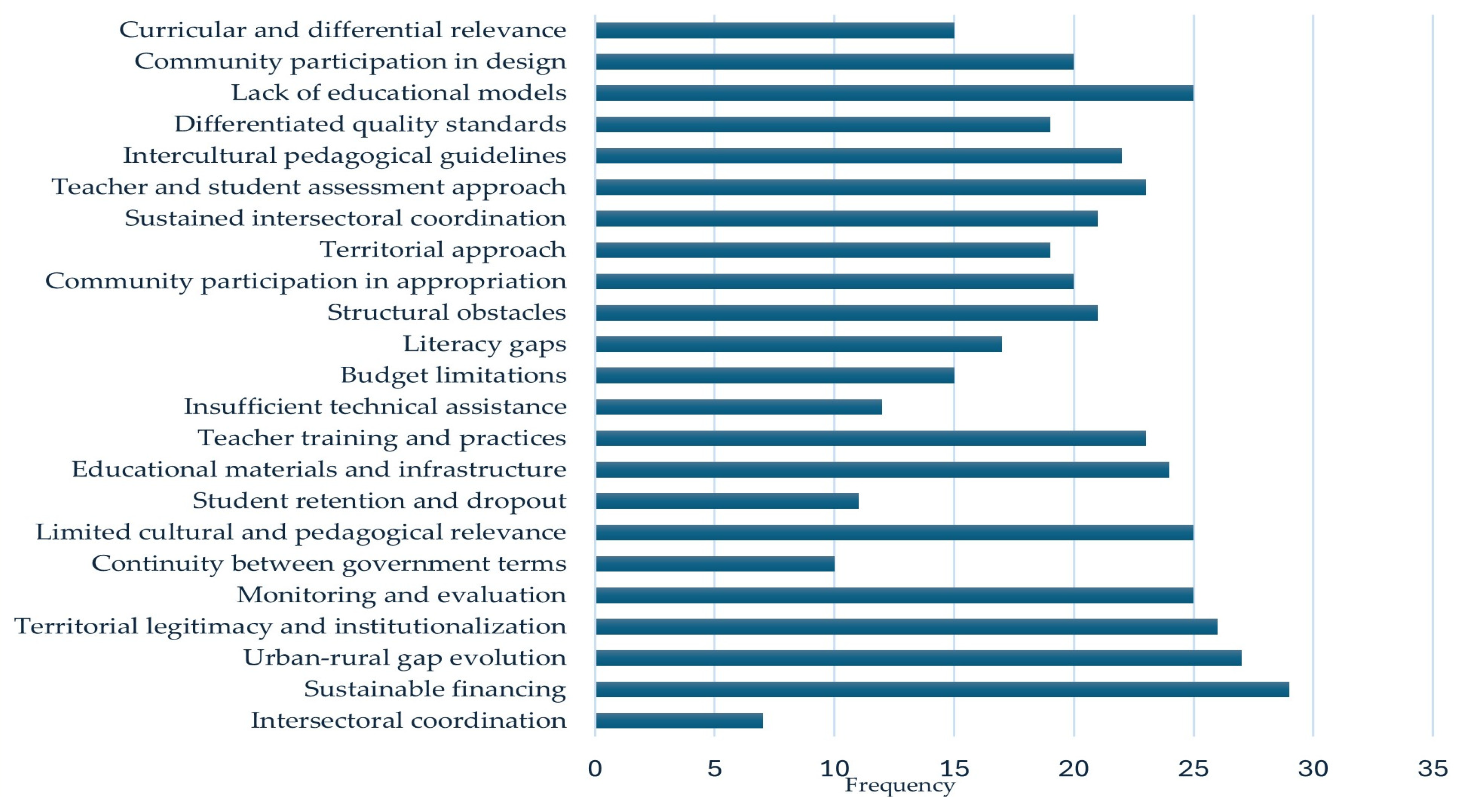

The analysis through ATLAS.ti enabled the identification and categorization of significant patterns in the 34 documents analyzed. The coding process revealed not only the frequency of appearance of different concepts but also the interrelationships between various dimensions of rural education. Through code co-occurrence analysis, significant connections were identified between categories such as sustainable financing and teacher retention, or between intersectoral articulation and cultural relevance of the curriculum. This depth of analysis was fundamental for understanding the multidimensional nature of challenges in rural education and the potential synergies between different policy interventions. The visual representations generated by the software (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) allow for an appreciation of both the frequency of identified categories and their interrelationships, providing a solid foundation for formulating educational policy recommendations.

The application of triangulation as a methodological strategy significantly enriched the findings by contrasting different theoretical perspectives. This approach revealed that rural educational policies in Colombia, while conceptually aligned with international recommendations such as those proposed by UNESCO [

34] and OECD [

40], present important gaps in their territorial implementation. The results of this triangulation process demonstrated that factors such as sustainable financing and urban–rural gaps do not operate in isolation but interact, creating cycles that perpetuate educational inequalities.

Similarly, when contrasting with international experiences, significant parallels emerge between the challenges faced by Colombia and other countries with similar geographic and socioeconomic contexts. For example, experiences documented in rural areas of China [

11] and India [

13] show common patterns related to inequitable distribution of resources and difficulties in retaining qualified teachers. However, the analysis also identified that, unlike experiences such as those implemented in Spain [

16], Colombian policies have shown greater difficulty in maintaining the long-term sustainability of rural educational interventions, particularly when facing governmental transitions.

Based on this analysis, specific recommendations are proposed, including investment in school infrastructure, improvement in teacher training and professional development, and integration of information and communication technologies to strengthen educational capacities. These strategies seek not only to improve equity and quality levels but also to promote inclusive education adapted to the realities of rural communities in Colombia

Figure 2 shows the distribution of frequencies of key factors influencing rural educational quality in Colombia based on the analysis of 34 documents.

The frequency analysis of codes in the 34 reviewed documents shows that the categories with the highest number of mentions are sustainable financing (29 mentions), territorial legitimacy and institutionalization (28), and monitoring and evaluation (27). These themes stand out as fundamental pillars to guarantee the sustainability and continuity of rural educational policies. Added to these are limited cultural and pedagogical relevance (26) and lack of educational models (25), aspects that signal the urgency of reviewing and adapting pedagogical proposals to local contexts.

Also highlighted are teacher training and practices (24 mentions) and the availability of educational materials and infrastructures (23) as key elements for the effective implementation of policies. The approach to teacher and student evaluation (22) and structural obstacles (21), along with community participation in design (20) and in appropriation (19), shows that the quality and relevance of policies depend largely on the articulation between technical and community aspects.

At medium frequency are intercultural pedagogical guidelines (18 mentions), budgetary limitations (17), sustained intersectoral articulation (16), curricular and differential relevance (15), and territorial approach (14). These dimensions reflect structural and pedagogical challenges that, although not the most cited, have profound implications for educational equity.

Finally, the least mentioned categories include literacy gaps (13 mentions), differentiated quality standards (12), insufficient technical assistance (11), lack of knowledge of territories (10), student retention and dropout (9), continuity between government periods (8), intersectoral articulation (7), and evolution of urban–rural gaps (6). Although their frequency is lower, their presence signals gaps that must be addressed to achieve a comprehensive response, especially in identifying local needs, technical support, and educational permanence. Nevertheless, it also emphasizes the need to overcome structural barriers and promote greater community participation, as well as strengthen cultural relevance in the design of policies that truly respond to the dynamics of rural territories.

Figure 3 displays a semantic network illustrating the interconnections between main categories (blue nodes) and subcategories (green nodes) that influence rural educational policies in Colombia.

The semantic network presented in

Figure 3 was constructed through the systematic process of relational analysis in ATLAS.ti, following three methodologically structured stages. First stage—Coding and categorization: During axial coding, co-occurrence patterns between codes were identified when they appeared simultaneously in the same textual segment or paragraph of the analyzed documents. ATLAS.ti automatically records these co-occurrences, but the interpretation of their theoretical meaning was performed manually by the researchers. Second stage—Categorical grouping: Individual codes were grouped into three main categories (Policy Design, Implementation, and Continuity and Sustainability) based on established Grounded Theory and theoretical triangulation. This grouping was not automated but resulted from the interpretive analysis of the researchers, considering conceptual coherence and the frequency of joint appearance of codes. Third stage—Validation of relationships: Connections between categories were validated through three criteria: (a) statistically significant co-occurrence (coefficient > 0.1 in ATLAS.ti), (b) theoretical coherence with the applied rural educational quality model, and (c) triangulation with analyzed international literature. The relationships represented by connection lines indicate conceptual links verified in at least 30% of the documents where both categories appeared. The final visualization was generated by ATLAS.ti’s network analysis function, but the interpretation of relationships, denomination of main categories, and validation of the theoretical coherence of the network were analytical processes performed entirely by the researchers, thus ensuring the conceptual validity of the resulting model.

In this way, the network visualizes the relationship structure between the different categories that influence rural educational policies. The blue nodes represent the main categories (Policy Design, Implementation, and Continuity and Sustainability), while the green nodes represent the subcategories that relate to these. The connection lines show direct relationships between categories, demonstrating how each element links with others in the rural educational system. This visualization is particularly relevant for understanding the interconnected nature of the different components of rural educational policy and how each element contributes to the functioning of the system as a whole.

Analysis of the Semantic Network: Categories and Interrelations

The semantic network generated from the document shows the interconnection between various categories and subcategories that influence the quality policies of rural education. In the Design category, the subcategories are directly related to the educational policy design process, evidencing specific aspects such as monitoring and evaluation, teacher training, cultural relevance, and intersectoral articulation, fundamental elements for achieving effective and contextualized design.

In the Implementation category, the subcategories focus on the challenges and barriers that may arise during the execution of educational policies. Structural obstacles, budgetary limitations, and literacy gaps emerge as the main factors that can negatively affect this process, highlighting the importance of considering these elements in the implementation phase.

In the Continuity and Sustainability category, the subcategories emphasize the importance of maintaining policy coherence and sustainability over time. Continuity between different governments, constant monitoring and evaluation, as well as sustainable financing, are revealed as crucial elements to ensure that implemented policies have a lasting and significant impact on the rural educational system.

4. Discussion

The rural educational system in Colombia faces a series of profound challenges that affect both the quality and accessibility of education. The critical factors identified in this research—sustainable financing, intersectoral articulation, and urban-rural gaps—operate as an interconnected system that determines the effectiveness of rural educational policies. To fully understand these challenges, it is essential to examine several key aspects, including infrastructure, human resources, curriculum relevance, inclusion and equity, community participation, and the impacts of current educational policies [

41].

School Infrastructure. School infrastructure in Colombia’s rural areas is often inadequate, with buildings in poor condition, a lack of proper sanitation facilities, and a general shortage of technological resources. The lack of access to paved roads and public transportation further complicates regular student attendance and the delivery of educational materials. Without adequate facilities, it is difficult to create a learning environment that is safe and conducive for students. Furthermore, the lack of access to technology limits digital learning opportunities, which are essential in the modern world [

48].

In this context, the contrast with experiences documented in Spain by Moraleda-Ruano and Bernal-Romero [

16] is revealing, as they identified that the sustainability of rural educational infrastructure depends not only on initial investment but also on institutional capacity for continuous maintenance. Analysis of Colombian data suggests that the weakness lies not only in the lack of infrastructure but in the absence of management models that guarantee its long-term functionality, particularly concerning technological resources. This problem reflects what can be conceptualized as an “implementation gap”—defined as the systematic disconnection between educational policies formulated at the national level and their effective materialization in specific rural territories. This gap operates in three interrelated dimensions: temporal, where short budgetary cycles contradict the long-term nature of educational transformations; territorial, where centralized models do not consider the geographical, climatic, and cultural particularities of each rural educational institution; and operational, where the lack of local institutional capacities prevents the sustainability of interventions.

The extreme geographical dispersion of Colombian rural territory exponentially amplifies these challenges, creating conditions where educational institutions can be separated by distances exceeding 50 km on impassable roads, with student populations facing travel times of up to two hours to access their educational centers. This reality contrasts dramatically with international experiences such as those documented by Kuger et al. [

14] in Germany, where rural contexts present relatively compact dispersion. In Colombia, each rural educational institution operates practically as an isolated microsystem, which invalidates educational management models designed for contexts with less dispersion and demands technological, logistical, and pedagogical solutions specifically adapted to these conditions of isolation.

Human Resources. Another significant challenge is the availability of qualified teachers. In rural areas, there is often a shortage of teaching staff, forcing teachers to teach multiple subjects and grades. This overload can affect the quality of teaching and teacher well-being. Additionally, continuous training and professional development are insufficient due to distance and lack of training opportunities. To improve education in these areas, it is crucial to invest in training and continuous support for teachers, ensuring they are well-prepared and motivated to face the specific challenges of rural areas [

49].

Analysis through theoretical triangulation allows us to identify that the teaching problem in Colombian rural areas transcends a simple numerical shortage to constitute a challenge of formative relevance. The category “teacher training and practices” (24 mentions) shows significant connectivity with “limited cultural and pedagogical relevance” (26 mentions), suggesting that current teacher training programs do not adequately address the specific competencies required for rural contexts. This finding coincides with what was documented by Yoosefi et al. [

31], who identified that teaching effectiveness in rural environments correlates more significantly with contextual adaptability than with general academic training. The cultural diversity that characterizes each Colombian rural territory demands intercultural teaching competencies that are not contemplated in traditional training programs, where multiple knowledge systems coexist—from peasant knowledge to Afro-Colombian knowledge—that require differentiated pedagogies.

Curriculum Relevance. The educational curriculum must be relevant to the reality of rural students, incorporating elements that are meaningful and useful for their lives and communities. This includes integrating agricultural practices, traditional knowledge, and life skills. A flexible curriculum that adapts to local needs can help ensure that students not only acquire academic knowledge but also practical skills that allow them to contribute to their communities. Furthermore, assessments should be culturally and contextually appropriate, considering the diverse realities of rural students [

50]. The high frequency of “lack of educational models” (25 mentions) in the analysis shows that rural educational institutions lack curricular frameworks specifically designed for their contexts, frequently operating with improvised adaptations of urban models that do not recognize territorial particularities or the educational opportunities offered by the rural environment.

Inclusion and Equity. Inclusion and equity are fundamental principles in any educational system. It is essential to ensure that all children and youth in rural areas have access to quality education, regardless of their gender, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status. This involves implementing specific policies and programs that address the barriers faced by the most vulnerable students. Additionally, the inclusion of information and communication technologies (ICT) in rural schools is crucial for closing the digital divide and providing students with the necessary tools for learning in the 21st century [

51]. The “structural obstacles” (21 mentions) identified in the analysis reflect systemic barriers that go beyond the simple lack of resources, including factors such as the absence of basic services (electricity, potable water, connectivity), the seasonality of local productive activities that affects school attendance, and gender dynamics that limit educational access, particularly for rural girls.

Community Participation. Community participation is essential for effective school management. Involving parents and the community in school management can strengthen the bond between school and community, creating a supportive environment for students. Community support programs can also provide additional resources and emotional support to students, improving their educational experience. Furthermore, ensuring adequate and equitable allocation of financial resources for rural schools is fundamental to addressing inequalities and improving education quality [

41]. The analysis revealed a significant differentiation between “community participation in design” (20 mentions) and “community participation in appropriation” (19 mentions), suggesting that while rural communities may be consulted during policy design, their effective involvement in the implementation and sustainability of educational interventions remains limited.

Impacts of Educational Policies. The National Rural Education Plan in Colombia has had mixed impacts. Despite efforts to improve quality and educational coverage in rural areas, significant challenges persist. Infrastructure remains deficient, teacher training and professional development are inadequate, and school dropout rates remain high. Additionally, low enrollment rates generally reflect low academic performance among rural students. The limited implementation of flexible educational models and the lack of adequate teacher preparation are persistent problems that must be addressed to improve rural education [

48]. These mixed impacts reflect local sociopolitical dynamics that introduce critical variables that are frequently underestimated, where the coincidence between short electoral cycles and the need for long-term interventions creates a “sustainability threshold” that requires approximately 5–7 years of consistent implementation to generate verifiable impacts. “Continuity between government periods” (24 mentions) emerges as a critical factor that determines whether rural educational policies manage to transcend administrative changes to consolidate as State policies.

Moreover, when contrasting global rural educational strategies with implementation possibilities in the Colombian context, the need emerges for a process of “contextual translation” that transcends the simple adoption of foreign models. While experiences such as those in Spain [

16] and Germany [

14] offer valuable lessons on institutional sustainability and pedagogical differentiation, their effective implementation in Colombia requires considering territorial particularities such as extreme geographical dispersion, cultural diversity, and local sociopolitical dynamics [

41].

This adaptation is not merely technical but fundamentally political, requiring the strengthening of three key dimensions: first, educational governance models that effectively empower local authorities, transitioning from nominal decentralization to real transfers of decision-making capacity and resources [

9]; second, community participation mechanisms that evolve from symbolic consultations toward processes of co-design and educational co-management, recognizing peasant communities as legitimate educational agents [

51]; and third, culturally situated pedagogical practices that value diverse epistemologies and traditional knowledge without reproducing the false dichotomy between “scientific” knowledge and “ancestral” knowledge [

52].

In this context of contextual adaptation, it is fundamental to recognize that the Colombian educational system has been historically influenced by European pedagogical models that, while contributing organizational structures, also reproduced colonial logics that devalued local forms of knowledge and perpetuated asymmetric power relations between urban and rural areas. Contemporary efforts for educational decolonization, documented by authors such as Vidal et al. [

53] in the documentary analysis, reflect a growing understanding of the need to overcome these colonial inheritances through the development of genuinely Latin American pedagogical theories and practices. This decolonial perspective does not imply an absolute rejection of external knowledge, but the construction of horizontal epistemic dialogues that recognize the validity of multiple forms of knowledge and promote what Castro-Gómez and Grosfoguel call “epistemic diversity” as the foundation of truly emancipatory education. Latin American popular education theory, with exponents such as Paulo Freire and Orlando Fals Borda, offers conceptual frameworks that allow rethinking rural education from paradigms that value territory, local culture, and community participation as constitutive elements of the educational process, not as obstacles to overcome.

Experiences such as Escuela Nueva in Colombia demonstrate that the most successful interventions are those that achieve local appropriation of general educational principles [

50], allowing each community to adapt methodologies and contents according to their particularities without sacrificing quality standards, thus creating genuinely Colombian responses to the country’s rural educational challenges, in contrast to standardized approaches observed in contexts such as Zimbabwe [

19] or India [

13]. The findings suggest that the effectiveness of rural educational policies depends fundamentally on their capacity to recognize and articulate the bidirectional relationship between quality rural education and integral territorial development, where the most successful interventions establish explicit links with integrated rural development projects, creating virtuous cycles that position rurality as a space for educational innovation and territorial development.

5. Conclusions

The research conducted on rural education in Colombia reveals significant findings that demonstrate the complexity and multiple challenges faced by the educational system in these areas. Generally speaking, the analysis using ATLAS.ti revealed that the most frequent categories (sustainable financing with 30 mentions, intersectoral articulation with 29 mentions, and evolution of urban–rural gaps with 28 mentions) are closely linked to the sustainability and effectiveness of rural educational policies. This interrelationship, confirmed by code co-occurrence analysis, suggests that any effective intervention must simultaneously consider these aspects, adopting a systemic approach that recognizes both local particularities and the structural needs of the rural educational system. Furthermore, the low frequency of categories such as ‘limited cultural and pedagogical relevance’ (26 mentions) and ‘student retention and dropout’ (15 mentions) does not imply lesser importance but rather suggests areas that require greater attention in the formulation of rural educational policies.

The theoretical triangulation implemented showed that, although Colombia has developed regulatory frameworks aligned with international recommendations, a significant gap persists in their territorial implementation. This “implementation gap”—defined as the systematic disconnection between centrally formulated policies and their effective materialization in specific rural territories—is not solely due to budgetary limitations but to the disconnection between centralized policy design and the heterogeneous realities of Colombian rural contexts, particularly evidenced in the high frequency of “continuity between government periods” (24 mentions) as a critical factor.

In this sense, the semantic network (

Figure 3) shows a complex interconnection between different factors that influence the quality of rural education; each category and subcategory does not act in isolation but is influenced by multiple factors. The three main categories identified—Policy Design, Implementation, and Continuity and Sustainability—operate as an interconnected system where relationships validated through statistically significant co-occurrence (coefficient > 0.1 in ATLAS.ti) demand a systemic approach that considers dynamic relationships between variables and anticipates cascade effects of educational interventions.

Comparison with international experiences allowed for the identification that, while countries such as Spain and Germany have developed effective mechanisms for the sustainability of rural educational interventions through governmental changes, Colombia faces particular challenges in policy continuity. This discontinuity, reflected in the analyzed data, prevents reaching what the analysis suggests as a “sustainability threshold”—approximately 5–7 years of consistent implementation—necessary for rural educational interventions to generate verifiable impacts. The documented extreme geographical dispersion amplifies these challenges, creating conditions where educational institutions operate as isolated microsystems that invalidate management models designed for contexts with less dispersion.

Similarly, similarities are identified with the Australian longitudinal analysis that identifies nine perennial themes that coincide with the critical factors found in Colombia: insufficient financing, teaching difficulties, curricular disconnection, and systemic inequities [

22]. The experience of Ghana demonstrates that the problem does not lie in “being rural” but in marginalization processes that devalue rural cultural capital [

23], reinforcing that urban–rural gaps do not constitute inherent deficiencies but manifestations of development models that have privileged urban centers.

The Complexity of the Rural Context: Education in rural areas presents unique challenges derived from the geographical, socioeconomic, and cultural characteristics of these communities, as evidenced by the high frequency of “structural obstacles” (21 mentions) and “budgetary limitations” (17 mentions) identified in the analysis. It is crucial to design educational strategies that consider these complexities to promote equitable educational development. This requires flexible policy frameworks that allow adaptations according to the specific characteristics of each rural territory.

The critical relationships between subcategories, validated through co-occurrence analysis, indicate that improvement in one area can have positive effects on others. For example, strengthening “sustained intersectoral articulation” (16 mentions) could address the “lack of educational models” (25 mentions), and improving “community participation in design” (20 mentions) could positively impact “community participation in appropriation” (19 mentions).

Finally, a significant finding confirmed by theoretical triangulation is the bidirectional relationship between quality rural education and territorial development. The analyzed data suggest that the most successful educational interventions are those that establish explicit links with integrated rural development projects, creating a virtuous cycle where education responds to territorial needs while contributing to transforming them positively. This systemic understanding, supported by experiences such as the Colombian Escuela Nueva documented in the analyzed literature, positions rurality as a space for educational innovation and territorial development, not as a lag to overcome.

Finally, this research presents limitations that open opportunities for future studies; the documentary analysis included academic literature up to 2024 and current official documents, establishing a solid knowledge base, but which requires continuous updating given the dynamic nature of rural educational policies. Therefore, future research should incorporate emerging literature and new regulatory developments to maintain the validity of the analysis. On the other hand, studies could be implemented that directly capture the voices of rural teachers, students, and the community in general. Likewise, it is particularly necessary to develop research that documents the processes of overcoming the identified “implementation gap”, the analysis of the specific impact of educational technologies in contexts of extreme geographical dispersion, and comparative studies that examine different models of intersectoral articulation in rural educational policies. These lines of research will contribute to the development of more robust theoretical and methodological frameworks for the design and implementation of contextually relevant and territorially effective rural educational policies.