Post-COVID-19 Analysis of Fiscal Support Interventions on Health Regulations and Socioeconomic Dimensions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Crisis and Intervention Theories

2.2. COVID-19 as Health Crisis

2.3. COVID-19 as Socioeconomic Crisis

2.4. Fiscal Support Interventions

2.5. Conceptual Model and Study Hypotheses

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

4.2.1. Direct Relationship

4.2.2. Mediation Analysis

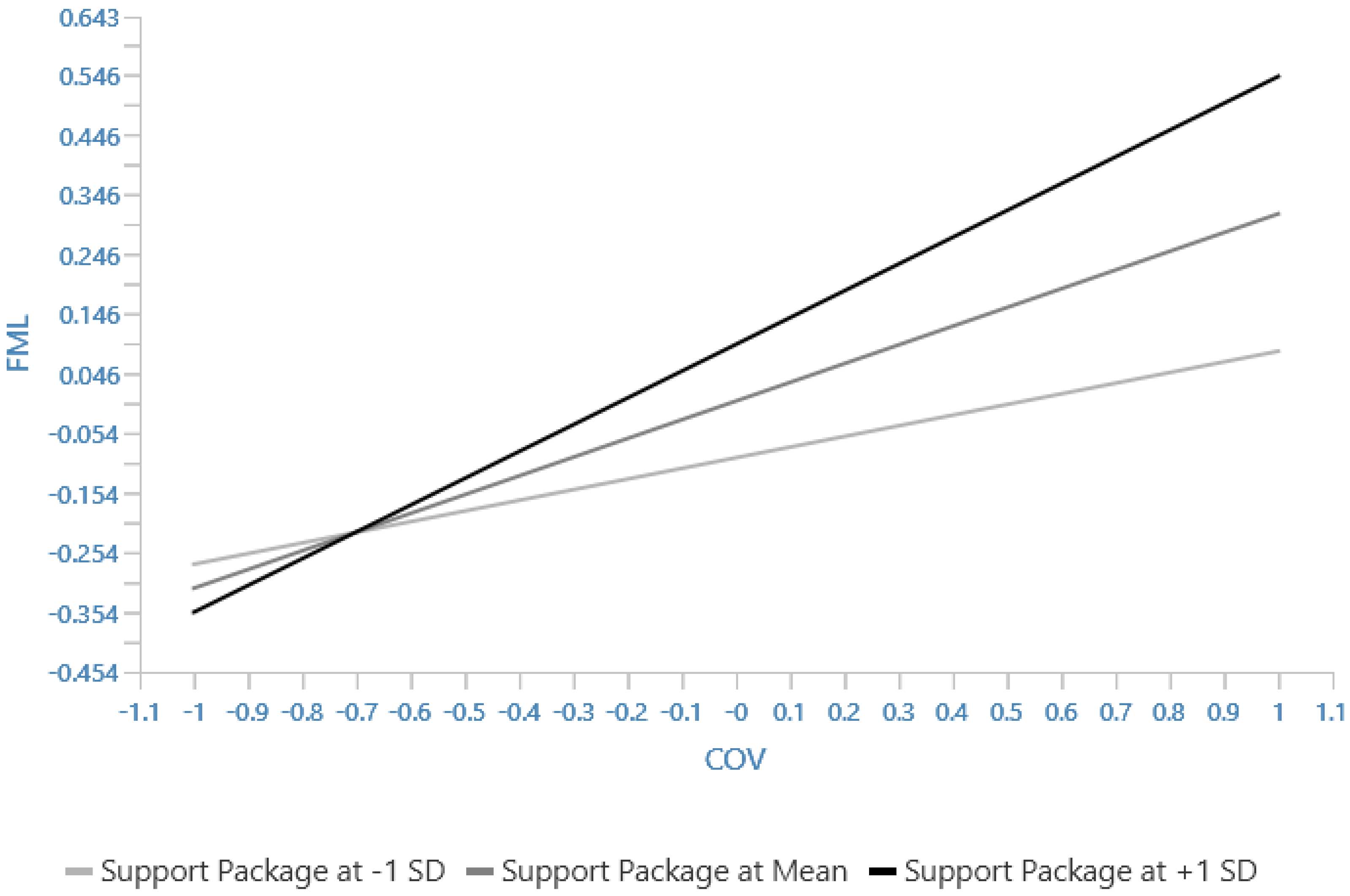

4.2.3. Moderation Analysis

4.2.4. Multigroup Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion, Implications, and Suggested Future Directions

6.1. Policy Implications

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Questionnaire Items

| Items | |

| The coronavirus had an impact on our employment status in our household (loss of work, diminished income). | VAR1 |

| COVID-19 had a negative impact on our levels of poverty in our household (affordability). | VAR2 |

| COVID-19 had a negative impact on our equality compared to other families in my community (progress in life or well-being). | VAR3 |

| COVID-19 had an impact on our way of life (e.g., family, social interaction, or community safety). | VAR4 |

| I or a member of my family have lost employment due to COVID-19. | VAR5 |

| A member of my family and I are struggling to find employment due to COVID-19. | VAR6 |

| I or a member of my family are working reduced hours due to COVID-19. | VAR7 |

| A member of my family or I have had a contract of employment terminated due to COVID-19. | VAR8 |

| A member of my family or I have had to relocate to find employment since COVID-19 (past 28 months). | VAR9 |

| My family is still able to have three meals a day. | VAR10 |

| My family has access to running water. | VAR11 |

| My family has a warm shelter to keep from bad weather conditions. | VAR12 |

| My family members can afford to see a doctor (hospital) in the event of illness. | VAR13 |

| My family is able to afford clothing for all our family members. | VAR14 |

| I or a member of my family suffers from stress due to COVID-19 challenges. | VAR15 |

| I or a member of my family suffers from anxiety due to the impact of COVID-19. | VAR16 |

| I or a member of my family is experiencing increased alcohol usage due to COVID-19. | VAR17 |

| I or a member of my family is experiencing increased drug usage due to COVID-19. | VAR18 |

| A member of my family or I have had to seek help for a mental illness due to COVID-19. | VAR19 |

| My family has received the family support needed during a time of difficulty since the COVID-19 outbreak. | VAR20 |

| My family has received the social support needed during a time of difficulty since the COVID-19 outbreak. | VAR21 |

| I and members of my family have felt the support of our friends even over the COVID-19 lockdown periods. | VAR22 |

| Our family has maintained strong family ties even after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. | VAR23 |

| A member of my family or I have been a recipient of the government relief fund (R350 unemployment Fund, UIF Claim, Top up grant, Food parcel distribution, etc.). | VAR24 |

| The R500 billion government support package has cushioned the financial negative impact caused by COVID-19. | VAR25 |

| The lockdown imposed by the government has helped to flatten the curve for COVID-19 infections. | VAR26 |

| The travel bans introduced by the government has minimized the full impact of COVID-19 on the country. | VAR27 |

| The curfews introduced by the government have helped mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. | VAR28 |

| Making the wearing of face masks mandatory has assisted in the spreading of the COVID-19 virus. | VAR29 |

| Limiting the number of people attending funerals, cremations, and other gatherings has been helpful in reducing the infection rate of COVID-19. | VAR30 |

References

- Alizadeh, H.; Sharifi, A.; Damanbagh, S.; Nazarnia, H.; Nazarnia, M. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the social sphere and lessons for crisis management: A literature review. Nat. Hazards 2023, 117, 2139–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandal, N.; Tanwar, R.; Saketh, M.; Pilania, U. Impact of COVID-19 on People; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, M.; Zaid, A.; Sohrabi, C.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, R.; Agha, M. The socio-economic implication of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A Review. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 78, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnitzler, L.; Janssen, L.; Evers, S.; Jackson, L.; Paulus, A.; Roberts, T.; Pokhilenko, I. The broader societal impacts of COVID-19 and the growing importance of capturing these in health economic analyses. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2021, 37, E43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2022. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Worldometer. South Africa Coronavirus: 4,076,463 Cases and 102,595 Deaths. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/south-africa/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Justman, J.E.; Abularrage, T.F. Insights on COVID-19 mortality and HIV from South Africa. Lancet HIV 2024, 11, e67–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, C.; Davies, R.; Gabriel, S.; Harris, L.; Makrelov, K.; Modise, B.; Robinson, S.; Simbanegavi, W.; van Seventer, D.; Anderson, L. Impact of COVID-19 on the South African Economy: An Initial Analysis; Southern Africa—Towards Inclusive Economic Development: Cape Town, South Africa, 2020; Volume 111, pp. 1–37. Available online: https://sa-tied.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/pdf/SA-TIED-WP-111.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Khowa, T.; Cimi, A.; Mukasi, T. Socio-economic impact of COVID-19 on rural livelihoods in Mbashe Municipality. Jàmbá-J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2022, 14, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, A.; Hoy, C.; Ortiz-Juarez, E. Estimates of the Impact of COVID-19 on Global Poverty, WIDER Working Paper 2020/43; The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research: Helsinki, Finland, 2020; Available online: https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/Publications/Working-paper/PDF/wp2020-43.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Ngcamu, B.; Mantzaris, E. The effects of COVID-19 on vulnerable groups: A reflection on South African informal urban settlements. Afr. Public Serv. Deliv. Perform. Rev. 2021, 9, a483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work. Seventh Edition: Updated Estimates and Analysis; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Coller, R.J.; Webber, S. COVID-19 and the well-being of children and families. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e2020022079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuntellaa, O.; Hydea, K.; Saccardob, S.; Sadoffc, S. Lifestyle and mental health disruptions during COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2016632118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandlazi, M.; Nyasha, S. Assessment of the COVID-19 pandemic in south africa. Ann. Spiru Haret Univ. Econ. Ser. 2023, 23, 441–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anakpo, G.; Nkungwana, S.; Mishi, S. Impact of COVID-19 on school attendance in South Africa. Analysis of sociodemographic characteristics of learners. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burri, M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Domestic Violence in South Africa; UJ Press eBooks: Johannesburg, South African, 2022; pp. 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Statement on the Fifteenth Meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 pandemic. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(COVID-19)-pandemic?adgroupsurvey={adgroupsurvey}&gclid=CjwKCAjw1YCkBhAOEiwA5aN4ATC1w9CRFr_Q2nZLtdwO1zd5LHZ66vOg3_cNeDV7JchBSQDcvQ5d9RoCl7cQAvD_BwE (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- European Commission. Q&A: Future Pandemics are Inevitable, But We Can Reduce the Risk. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research-and-innovation/en/horizon-magazine/qa-future-pandemics-are-inevitable-we-can-reduce-risk (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Bai, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, M.; Bian, L.; Liu, J.; Gao, F.; Mao, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wu, X.; Xu, M.; et al. The next major emergent infectious disease: Reflections on vaccine emergency development strategies. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2022, 21, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauci, A.S.; Folkers, G.K. Pandemic Preparedness and Response: Lessons from COVID-19. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 228, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Must Be Ready to Respond to Next Pandemic: WHO Chief. 2023. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/05/1136912 (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Ghazalian, P.L. Globalization and the Fallout of the COVID-19 Pandemic. World 2025, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khambule, I. COVID-19 and the Counter-cyclical Role of the State in South Africa. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2021, 21, 380–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitiga-Mabugu, M.; Henseler, M.; Mabugu, R.; Maisonnave, H. Economic and Distributional Impact of COVID-19: Evidence from Macro-Micro Modelling of the South African Economy. S. Afr. J. Econ. 2021, 89, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhan, R.; Prabheesh, K. The economics of COVID-19 pandemic: A survey. Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 70, 220–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons Leigh, J.; Fiest, K.; Brundin-Mather, R.; Plotnikoff, K.; Soo, A.; Sypes, E.E.; Whalen-Browne, L.; Ahmed, S.B.; Burns, K.E.A.; Fox-Robichaud, A.; et al. A national cross-sectional survey of public perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic: Self-reported beliefs, knowledge, and behaviors. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folayan, M.O.; Abeldaño Zuñiga, R.A.; Virtanen, J.I.; Ezechi, O.C.; Yousaf, M.A.; Jafer, M.; Al-Tammemi, A.B.; Ellakany, P.; Ara, E.; Ayanore, M.A.; et al. A multi-country survey of the socio-demographic factors associated with adherence to COVID-19 preventive measures during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft, R.; Sur, D.; Greenblatt, A.; Donahue, P. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Workers at the Frontline: A Survey of Canadian Social Workers. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2021, 52, 1724–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Koning, R.; Egiz, A.; Kotecha, J.; Ciuculete, A.C.; Ooi, S.Z.Y.; Bankole, N.D.A.; Erhabor, J.; Higginbotham, G.; Khan, M.; Dalle, D.U.; et al. Survey Fatigue During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis of Neurosurgery Survey Response Rates. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 690680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clay, K.C.; Abdelwahab, M.; Bagwell, S.; Barney, M.; Burkle, E.; Hawley, T.; Kehoe Rowden, T.; LaVelle, M.; Parker, A.; Rains, M. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on human rights practices: Findings from the Human Rights Measurement Initiative’s 2021 Practitioner Survey. J. Hum. Rights 2022, 21, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, A. Perceptions of Dental Students towards Online Teaching during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Open Access J. Dent. Sci. 2023, 8, 00358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, M.-C.; Schnakovszky, C.; Herghelegiu, E.; Ciubotariu, V.-A.; Cristea, I. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Quality of Educational Process: A Student Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, E.; Lippens, L.; Sterkens, P.; Weytjens, J.; Baert, S. The COVID-19 crisis and telework: A research survey on experiences, expectations and hopes. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2021, 23, 729–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.K.; Dinh, H.; Nguyen, H.; Le, D.-N.; Nguyen, D.-K.; Tran, A.C.; Nguyen-Hoang, V.; Nguyen Thi Thu, H.; Hung, D.; Tieu, S.; et al. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on College Students: An Online Survey. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotayo, A.O.; Ogunniyi, A. COVID-19 Pandemic, Poverty and Health Outcomes in South Africa: Do Social Protection Programmes Protect? J. Afr. Econ. 2024, 33 (Suppl. S1), i9–i29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hegde, S.; Son, C.; Keller, B.; Smith, A.; Sasangohar, F. Investigating Mental Health of US College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newson, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zein, M.E.; Sulik, J.; Dezecache, G.; Deroy, O.; Tunçgenç, B. Digital contact does not promote wellbeing, but face-to-face contact does: A cross-national survey during the COVID-19 pandemic. New Media Soc. 2024, 26, 426–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis, A.; Paksarian, D.; Alexander, L.; Derosa, J.; Dunn, J.; Nielson, D.M.; Droney, I.; Kang, M.; Douka, I.; Bromet, E.; et al. The Coronavirus Health and Impact Survey (CRISIS) reveals reproducible correlates of pandemic-related mood states across the Atlantic. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönkkö, R.; Rutherford, S.; Sen, K. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the poor: Insights from the Hrishipara diaries. World Dev. 2022, 149, 105689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Headey, D.; Goudet, S.; Lambrecht, I.; Maffioli, E.M.; Oo, T.Z.; Russell, T. Poverty and food insecurity during COVID-19: Phone-survey evidence from rural and urban Myanmar in 2020. Glob. Food Secur. 2022, 33, 100626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schotte, S.; Zizzamia, R. The livelihood impacts of COVID-19 in urban South Africa: A view from below. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 165, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narjis, S.; Yaseen, M.; Anwar, S.; Makhdoom, M.S.A. The Socio-Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Households in Punjab, Pakistan. J. Econ. Impact 2022, 4, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiramkhanov, T.; Bogdan, S.; Yerbol, I. Analyzing and Responding to the Spread of COVID-19. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 4th International Conference on Smart Information Systems and Technologies (SIST), Astana, Kazakhstan, 15–17 May 2024; pp. 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Maldonado, M. COVID-19 as a Global Risk: Confronting the Ambivalences of a Socionatural Threat. Societies 2020, 10, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, R. Effects of Pandemic Outbreak on Economies: Evidence From Business History Context. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 632043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walby, S. Crisis and society: Developing the crisis theory in the context of COVID-19. Glob. Discourse 2022, 12, 498–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.A. From Research to Social Improvement: Understanding Theories of Intervention. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2000, 29, 81–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankonen, N. Intervention Theories. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Gellman, M.D., Turner, J.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidani, S.; Fox, M.; El-Masri, M.M. Guidance for the Reporting of an Intervention’s Theory. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2020, 34, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahara, M.A.; Charles, E.; Bagonza, A.R.; Lubaale, G.; Esther, E.C.; Joel, M.; Eze, V.H.U. Government Interventions and Household Poverty in Uganda: A Comprehensive Review and Critical Analysis. IAA-JSS 2023, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, W.J.V.; Kok, M.T.J. Government Interventions in Sustainable Supply Chain Governance: Experience in Dutch Front-running Cases. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 83, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, G.; Chopra, D. Development and Welfare Policy in South Asia; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh, A.; Radu, C.F.; Feniser, C.; Borşa, A. Governmental Intervention and Its Impact on Growth, Economic Development, and Technology in OECD Countries. Sustainability 2020, 13, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Waldt, G. Government Interventionism and Sustainable Development: The Case of South Africa. Afr. J. Public Aff. 2015, 8, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H.W.; Apio, C.; Goo, T.; Heo, G.; Han, K.; Kim, T.; Kim, H.; Ko, Y.; Lee, D.; Lim, J.; et al. Effects of government policies on the spread of COVID-19 worldwide. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtotywa, M.M.; Mtotywa, V.L.V. Diagnostic assessment of post-COVID-19 operations for business model reconfiguration decision. J. Manag. Res. 2022, 9, 66–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, T.; Brewer, T.; Veltcheva, D.; Huntingford, C.; Bonsall, M.B. How and When to End the COVID-19 Lockdown: An Optimization Approach. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, N.; Geyrhofer, L.; Londei, A.; Dervic, E.; Desvars-Larrive, A.; Loreto, V.; Pinior, B.; Thurner, S.; Klimek, P. Ranking the effectiveness of worldwide COVID-19 government interventions. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 1303–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susič, D.; Tomšič, J.; Gams, M. Ranking Effectiveness of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions Against COVID-19: A Review. Informatica 2022, 46, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferhani, A.; Rushton, S. The International Health Regulations, COVID-19, and bordering practices: Who gets in, what gets out, and who gets rescued? Contemp. Secur. Policy 2020, 41, 458–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.Y.; Lee, Y.R.; Cho, M.H.; Kim, Y.T.; Heo, B.Y. Impact of Government Intervention in Response to Coronavirus Disease 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukhi, N.; Mokhele, T.; Parker, W.A.; Ramlagan, S.; Gaida, R.; Mabaso, M.; Sewpaul, R.; Jooste, S.; Naidoo, I.; Parker, S.; et al. Compliance with Lockdown Regulations During the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Africa: Findings from an Online Survey. Open Public Health J. 2021, 14, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelsohn, A.S.; De Sá, A.; Morden, E.; Botha, B.; Boulle, A.; Paleker, M.; Davies, M.A. COVID-19 wave 4 in Western Cape Province, South Africa: Fewer hospitalisations, but new challenges for a depleted workforce. S. Afr. Med. J. 2022, 112, 13496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaglia, L.; Verdun, A. Explaining the response of the ECB to the COVID-19 related economic crisis: Inter-crisis and intra-crisis learning. J. Eur. Public Policy 2022, 30, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, J.D.; Verhagen, W.; Mapes, B.; Bohl, D.K.; Xiong, Y.; Yang, V.; McNeil, K.; Solórzano, J.; Irfan, M.; Carter, C.; et al. How many people is the COVID-19 pandemic pushing into poverty? A long-term forecast to 2050 with alternative scenarios. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebel, M.; Gundert, S. Changes in Income Poverty Risks at the Transition from Unemployment to Employment: Comparing the Short-Term and Medium-Term Effects of Fixed-Term and Permanent Jobs. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 167, 507–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J. African Truth Commissions and Transitional Justice; Lexington Books: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ndou, E. Inflation-Income Inequality Nexus in South Africa: The Role of Inflationary Environment. J. Appl. Econ. 2024, 27, 2316968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtotywa, M.; Motaung, M. Effects of Poverty Challenges on Youth Learnership Success. Dev. S. Afr. 2024, 41, 628–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajefu, J.B.; Demir, A.; Rodrigo, P. COVID-19-induced Shocks, Access to Basic Needs and Coping Strategies. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2023, 35, 1347–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiters, G. The Moving Line Between State Benevolence and Control: Municipal Indigent Programmes in South Africa. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2016, 53, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiwire, P.; Evers, S.M.; Mahomed, H.; Hiligsmann, M. Willingness to pay for primary health care at public facilities in the Western Cape Province, Cape Town, South Africa. J. Med. Econ. 2021, 24, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Man, A. “It Is the Poor Who Will Suffer the Most”: The Discriminatory Impact of Covid-19 Lockdown Restrictions on the Poor in South Africa. PER 2023, 26, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahmandnia, B.; Hamdanieh, L.; Aghababaeian, H. COVID-19 and Unfinished Mourning. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2020, 35, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketwa, A.; Kang’ethe, S.M. Manifestation of the Socio-Psychological Impact of COVID-19 in Selected Contexts around the Globe. Perspect. Glob. Dev. Technol. 2024, 23, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kgatle, M.S.; Segalo, P. Grieving during a Pandemic: A Psycho-Theological Response. Verbum Eccles. 2021, 42, a2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A.; Rhinard, M. Crisis management performance and the European Union: The case of COVID-19. J. Eur. Public Policy 2022, 30, 655–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.; Nokhepheyi, Y. The Ministerial Advisory Committees and 3 years of COVID-19 expertise—Is the Department of Health’s model for information-sharing pandemic-ready? S. Afr. Med. J. 2024, 114, e1943. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, M. The role of fiscal stimulus packages in addressing economic conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tanmiyat Al-Rafidain 2021, 40, 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddik, M.N.A. Economic stimulus for COVID-19 pandemic and its determinants: Evidence from cross-country analysis. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgin, C.; Williams, C.C.; Oz-Yalaman, G.; Yalaman, A. Fiscal stimulus packages to COVID-19: The role of informality. J. Int. Dev. 2022, 34, 861–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langry, F.; Rena, R. Socio-Economic Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic and its Impact on the South African Informal Economy. Afr. J. Inter/Multidiscip. Stud. 2023, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazenda, A.; Matjane, K.; Maleka, M.S.; Mushayanyama, T.; Masiya, T. Challenges in the Implementation of the City of Johannesburg’s Expanded Social Package in Alleviating COVID-19 Induced Food Insecurity. Afr. Public Serv. Deliv. Perform. Rev. 2021, 9, a470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielli, S.; Patria, R.; Donnelly, P.; Ashrafian, H.; Darzi, A. Economic interventions to ameliorate the impact of COVID-19 on the economy and health: An international comparison. J. Public Health 2020, 43, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Economic Justice (IEJ). An Emergency Rescue Package for South Africa in Response to COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.groundup.org.za/media/uploads/documents/IEJFull.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- South African Presidency. Statement by President Cyril Ramaphosa on Further Economic and Social Measures in Response to the COVID-19 Epidemic; The South African Presidency: Pretoria, South African, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Key Policy Responses from OECD. 2020. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/#policy-responses (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- IMF. Policy Responses to COVID-19. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19 (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- World Bank. Measuring Poverty. 2020. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/measuringpoverty (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Bricka, T.M.; He, Y.; Schroeder, A.N. Difficult Times, Difficult Decisions: Examining the Impact of Perceived Crisis Response Strategies During COVID-19. J. Bus. Psychol. 2022, 38, 1077–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilakati, V.M.; Bentley, W. ‘Same Storm—Different Boats’: A Southern African Methodist Response to Socio-Economic Inequalities Exposed by the COVID-19 Storm. Theol. Viat. 2021, 45, a136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtotywa, M.M. Conversations with Novice Researchers; AndsM: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Leedy, P.D.; Ormrod, J.E. Practical Research: Planning and Design, 12th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. Census 2022: Statistical Release P0301.4; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2023. Available online: https://census.statssa.gov.za/assets/documents/2022/P03014_Census_2022_Statistical_Release.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.; Zhao, K.; Fils-Aime, F. Response rates of online surveys in published research: A meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2022, 7, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J.H.; Magno, F.; Cassia, F. Reviewing the SmartPLS 4 software: The latest features and enhancements. J. Mark. Anal. 2024, 12, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Peng, C.Y. Principled missing data methods for researchers. Springerplus 2013, 2, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. IBM SPSS Statistics 26 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 16th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtotywa, M.M.; Kekana, C. Post COVID-19 Online Shopping in South Africa: A Mediation Analysis of Customer Satisfaction on e-Service Quality and Purchase Intention. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2023, 15, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; Lau, R.S.; Wang, L.C. Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2023, 41, 745–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, C.M.; Brady, M.K.; Calantone, R.; Ramirez, E. Discriminant validity testing in marketing: An analysis, causes for concern, and proposed remedies. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 44, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, T.; Bhorat, H.; Hill, R.; Stanwix, B. Lockdown stringency and employment formality: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa. J. Labour Mark. Res. 2023, 57, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestetti, R.B.; Furlan-Daniel, R.; Couto, L.B. Nonpharmaceutical public health interventions to curb the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2022, 16, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, K.; Regmi, K.; Lwin, C.M. Factors Associated with the Implementation of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions for Reducing Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassier, I.; Budlender, J.; Zizzamia, R.; Jain, R. The labor marsssket and poverty impacts of COVID-19 in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Econ. 2023, 91, 419–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. Quarterly Labour Force Survey: Quarter 3, 2023; Statistical Release P0211; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bhorat, H.; Oosthuizen, M.; van der Westhuizen, C. Estimating a poverty line: An application to free basic municipal services in South Africa. Dev. S. Afr. 2012, 29, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DPLG National Framework—Department of Provincial and Local Government. National Framework for Municipal Indigent Policies; Pretoria Government Printers: Pretoria, South Africa, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. Quarterly Labour Force Survey: Quarter 2, 2023; Statistical Release P0211; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- John, V.M. The Violence of South Africa’s COVID-19 Corruption. Peace Rev. 2021, 33, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S. The Impact of Corruption and Unethical Conduct During COVID-19 Pandemic on Public Funds, South Africa. J. Public Policy Adm. 2022, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesso, C.; Hamman, A. Grappling with the scourge of money laundering during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa. J. Anti-Corrupt. Law 2023, 6, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudau, P. The Implications of Food-Parcel Corruption for the Right to Food during the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Africa. ESR Rev. Econ. Soc. Rights S. Afr. 2022, 23, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borodovsky, J.T. Generalizability and representativeness: Considerations for internet-based research on substance use behaviors. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 30, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, S.K. External validity & non-probability sampling. Indian J. Med. Res. 2015, 141, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Variables | M | SD | Λ | α | ρA | ρc | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poverty level (PVL) | VAR1 | 5.27 | 2.075 | 0.880 | 0.868 | 0.870 | 0.919 | 0.792 |

| VAR2 | 5.36 | 1.984 | 0.931 | |||||

| VAR3 | 5.41 | 1.844 | 0.857 | |||||

| VAR4 | 6.55 | 0.686 | ||||||

| Employment level (EMP) | VAR5 | 4.64 | 2.253 | 0.879 | 0.878 | 0.897 | 0.911 | 0.674 |

| VAR6 | 4.94 | 2.116 | 0.854 | |||||

| VAR7 | 4.39 | 2.234 | 0.753 | |||||

| VAR8 | 4.16 | 2.304 | 0.876 | |||||

| VAR9 | 3.68 | 2.217 | 0.732 | |||||

| Life quality (LQT) | VAR10 | 5.95 | 1.134 | 0.786 | 0.882 | 0.854 | 0.598 | |

| VAR11 | 6.25 | 0.767 | 0.622 | |||||

| VAR12 | 6.37 | 0.627 | 0.734 | |||||

| VAR13 | 5.58 | 1.496 | 0.889 | |||||

| VAR14 | 5.19 | 1.653 | 0.821 | |||||

| Health and well-being (HWB) | VAR15 | 5.12 | 1.774 | 0.702 | 0.8 | 0.842 | 0.864 | 0.616 |

| VAR16 | 5.09 | 1.816 | 0.708 | |||||

| VAR17 | 3.5 | 2.1 | 0.854 | |||||

| VAR18 | 2.84 | 1.937 | 0.861 | |||||

| Family and social support (FML) | VAR19 | 4.79 | 2.059 | 0.746 | 0.825 | 0.853 | 0.665 | |

| VAR20 | 4.16 | 2.016 | 0.884 | |||||

| VAR21 | 3.7 | 1.956 | 0.903 | |||||

| VAR22 | 4.98 | 1.661 | 0.631 | |||||

| VAR23 | 5.66 | 1.421 | ||||||

| Relief fund (RLF) | VAR24 | 3.2 | 2.151 | 1 | ||||

| Support package (SUP) | VAR25 | 3.44 | 1.948 | 1 | ||||

| COVID-19 health regulations (COV) | VAR26 | 4.97 | 1.676 | 0.849 | 0.884 | 0.898 | 0.915 | 0.685 |

| VAR27 | 4.95 | 1.772 | 0.87 | |||||

| VAR28 | 4.96 | 1.745 | 0.896 | |||||

| VAR29 | 5.7 | 1.241 | 0.727 | |||||

| VAR30 | 5.63 | 1.558 | 0.785 |

| EMP | FML | HWB | COV | PVL | LQT | RLF | SUP | SUPP × COV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterotrait– monotrait ratio (HTMT)— matrix | EMP | |||||||||

| FML | 0.117 | |||||||||

| HWB | 0.713 | 0.113 | ||||||||

| COV | 0.061 | 0.376 | 0.120 | |||||||

| PVL | 0.712 | 0.103 | 0.536 | 0.060 | ||||||

| LQT | 0.444 | 0.392 | 0.370 | 0.226 | 0.422 | |||||

| RLF | 0.358 | 0.112 | 0.275 | 0.133 | 0.344 | 0.162 | ||||

| SUP | 0.139 | 0.208 | 0.119 | 0.303 | 0.067 | 0.070 | 0.171 | |||

| SUPP × COV | 0.052 | 0.073 | 0.063 | 0.280 | 0.038 | 0.066 | 0.041 | 0.010 |

| Effects | Path | β | t-Statistics | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effects | COV- > EMP | −0.081 | 1.239 | 0.215 |

| COV- > FML | 0.324 | 5.317 | 0.000 | |

| COV- > HWB | −0.085 | 0.997 | 0.319 | |

| COV- > PVL | −0.047 | 0.576 | 0.565 | |

| COV- > LQT | 0.215 | 2.683 | 0.007 | |

| COV- > RLF | 0.126 | 2.225 | 0.026 | |

| RLF- > EMP | 0.341 | 6.683 | 0.000 | |

| RLF- > FML | 0.050 | 0.837 | 0.403 | |

| RLF- > HWB | 0.261 | 4.405 | 0.000 | |

| RLF- > PVL | 0.328 | 6.413 | 0.000 | |

| RLF- > LQT | −0.202 | 2.619 | 0.009 | |

| SUP- > EMP | 0.110 | 1.806 | 0.071 | |

| SUP- > FML | 0.100 | 1.665 | 0.096 | |

| SUP- > HWB | 0.082 | 1.208 | 0.227 | |

| SUP- > PVL | 0.035 | 0.513 | 0.608 | |

| SUP- > LQT | −0.065 | 0.974 | 0.330 | |

| SUP × COV- > EMP | −0.009 | 0.161 | 0.872 | |

| SUP × COV- > FML | 0.135 | 2.817 | 0.005 | |

| SUP × COV- > HWB | 0.017 | 0.238 | 0.812 | |

| SUP × COV- > PVL | −0.002 | 0.005 | 0.996 | |

| SUP × COV- > LQT | 0.015 | 0.309 | 0.757 | |

| Direct | COV- > EMP | −0.124 | 1.989 | 0.047 |

| COV- > FML | 0.318 | 5.167 | 0.000 | |

| COV- > HWB | −0.118 | 1.413 | 0.158 | |

| COV- > PVL | −0.088 | 1.109 | 0.267 | |

| COV- > LQT | 0.241 | 3.230 | 0.001 | |

| COV- > RLF | 0.126 | 2.225 | 0.026 | |

| RLF- > EMP | 0.341 | 6.683 | 0.000 | |

| RLF- > FML | 0.050 | 0.837 | 0.403 | |

| RLF- > HWB | 0.261 | 4.405 | 0.000 | |

| RLF- > PVL | 0.328 | 6.413 | 0.000 | |

| RLF- > LQT | −0.202 | 2.619 | 0.009 | |

| SUP- > EMP | 0.110 | 1.806 | 0.071 | |

| SUP- > FML | 0.100 | 1.665 | 0.096 | |

| SUP- > HWB | 0.082 | 1.208 | 0.227 | |

| SUP- > PVL | 0.035 | 0.513 | 0.608 | |

| SUP- > LQT | −0.065 | 0.974 | 0.330 | |

| SUP × COV- > EMP | −0.009 | 0.161 | 0.872 | |

| SUP × COV- > FML | 0.135 | 2.817 | 0.005 | |

| SUP × COV- > HWB | 0.017 | 0.238 | 0.812 | |

| SUP × COV- > PVL | −0.002 | 0.005 | 0.996 | |

| SUP × COV- > LQT | 0.015 | 0.309 | 0.757 | |

| Effects | Path | β | t-statistics | p-value |

| Specific indirect effects | COV- > RLF- > PVL | 0.041 | 2.052 | 0.040 |

| COV- > RLF- > FML | 0.006 | 0.718 | 0.473 | |

| COV- > RLF- > LQT | −0.025 | 1.554 | 0.120 | |

| COV- > RLF- > HWB | 0.033 | 1.979 | 0.048 | |

| COV- > RLF- > EMP | 0.043 | 2.092 | 0.036 |

| Gender | Age | Area of Stay | Members of the Household | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | Female– Male | 35–45 Years and ≤35 Years | 35–45 Years and >45 Years | <35 Years and >45 Years) | Suburb or City Center— Township | Suburb or City Center— Village or Farm | Township— Village or Farm | ≤3 Member—4–5 Members | 3 Members or Less to >5 Members | 4–5 Members—<5 Members |

| COV - > RLF-> PVL | −0.044 | 0.046 | −0.078 | −0.124 * | −0.001 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.039 | 0.052 | 0.013 |

| COV - > RLF -> FML | −0.006 | 0.006 | 0.031 | 0.025 | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0.006 | −0.026 | −0.032 |

| COV - > RLF -> LQT | 0.051 | −0.035 | −0.079 | −0.044 | 0.047 | −0.008 | −0.055 | −0.031 | −0.003 | 0.028 |

| COV - > RLF -> HWB | −0.070 | 0.028 | −0.039 | −0.067 | 0.031 | 0.028 | −0.003 | 0.045 | 0.016 | −0.029 |

| COV - > RLF -> EMP | −0.068 | 0.043 | −0.078 | −0.121 * | −0.004 | 0.038 | 0.041 | 0.038 | 0.035 | −0.003 |

| SUP × COV - > EMP | −0.021 | −0.035 | 0.074 | 0.108 | −0.082 | −0.007 | 0.075 | 0.047 | −0.188 | −0.236 |

| SUP × COV - > FML | −0.127 | 0.250 * | −0.046 | −0.296 * | −0.003 | 0.437 | 0.440 | −0.057 | −0.052 | 0.005 |

| SUP × COV - > HWB | −0.095 | −0.201 | 0.066 | 0.267 | −0.037 | −0.092 | −0.055 | 0.119 | −0.112 | −0.232 |

| SUP × COV - > PVL | 0.079 | −0.350 * | −0.136 | 0.213 | 0.071 | −0.096 | −0.167 | 0.315 * | −0.028 | −0.343 |

| SUP × COV - > LQT | 0.234 * | 0.219 | 0.214 | −0.005 | 0.189 | 0.355 | 0.166 | −0.024 | 0.178 | 0.202 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mtotywa, M.M.; Mdletshe, N.N. Post-COVID-19 Analysis of Fiscal Support Interventions on Health Regulations and Socioeconomic Dimensions. Societies 2025, 15, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060143

Mtotywa MM, Mdletshe NN. Post-COVID-19 Analysis of Fiscal Support Interventions on Health Regulations and Socioeconomic Dimensions. Societies. 2025; 15(6):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060143

Chicago/Turabian StyleMtotywa, Matolwandile Mzuvukile, and Nandipha Ngcukana Mdletshe. 2025. "Post-COVID-19 Analysis of Fiscal Support Interventions on Health Regulations and Socioeconomic Dimensions" Societies 15, no. 6: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060143

APA StyleMtotywa, M. M., & Mdletshe, N. N. (2025). Post-COVID-19 Analysis of Fiscal Support Interventions on Health Regulations and Socioeconomic Dimensions. Societies, 15(6), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060143