Basic Human Values in Portugal: Exploring the Years 2002 to 2020

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Policies of social and economic inclusion: Portugal has implemented policies to reduce social and economic disparities. Programs such as the Social Integration Income (RSI) exemplify how the government seeks to support the most vulnerable. There is also a strong investment in education and vocational training to increase employability and promote equal opportunities [11,12].

- Health and well-being: The Portuguese healthcare system, based on the National Health Service (SNS), reflects the value of universal and equal access to healthcare. Recent reforms aim to enhance the efficiency and quality of healthcare services while ensuring accessibility for the entire population [13,14,15].

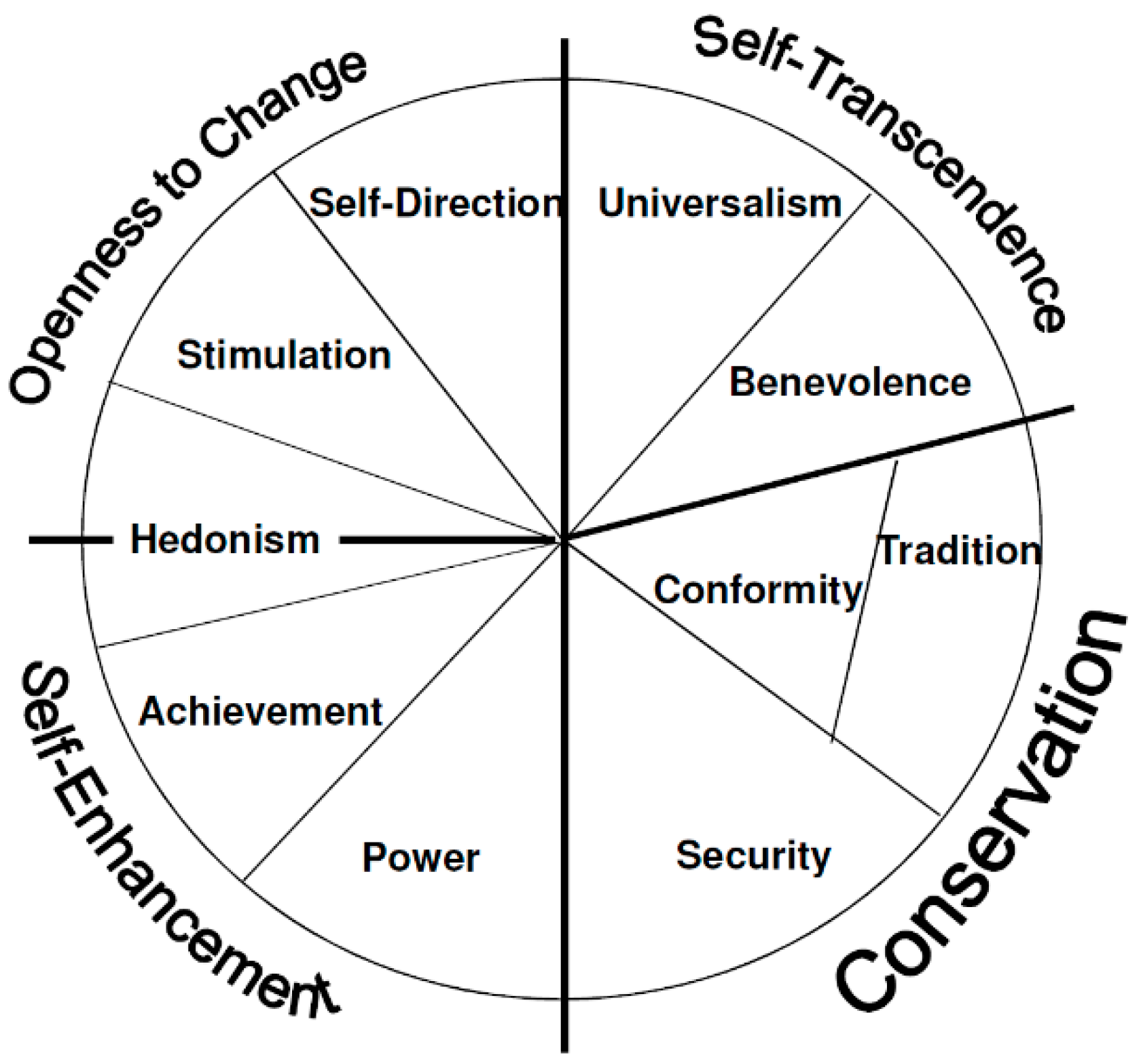

2. Schwartz’s Theory of Basic Human Values

- Self-direction—independent thought and action; autonomy in decision-making and creativity;

- Stimulation—pursuit of excitement, novelty, and challenges;

- Hedonism—pursuit of pleasure and sensory gratification;

- Achievement—emphasis on personal success through demonstrating competence according to social standards;

- Power—desire for social status, prestige, and dominance over people and resources;

- Security—valuing security, harmony, and social and personal stability;

- Conformity—restraining actions that disrupt social harmony or violate established norms;

- Tradition—respect for and commitment to traditional customs and beliefs;

- Benevolence—concern for the welfare of people close to oneself;

- Universalism—understanding, tolerance, and protection for the welfare of all people and nature.

- Openness to Change: Self-Direction and Stimulation;

- Conservation: Security, Conformity, and Tradition;

- Self-Enhancement: Achievement and Power;

- Self-Transcendence: Benevolence and Universalism.

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Variation in Higher-Order Values (HOVs) Subsection

4.2. Comparison of Basic Human Values Among Countries

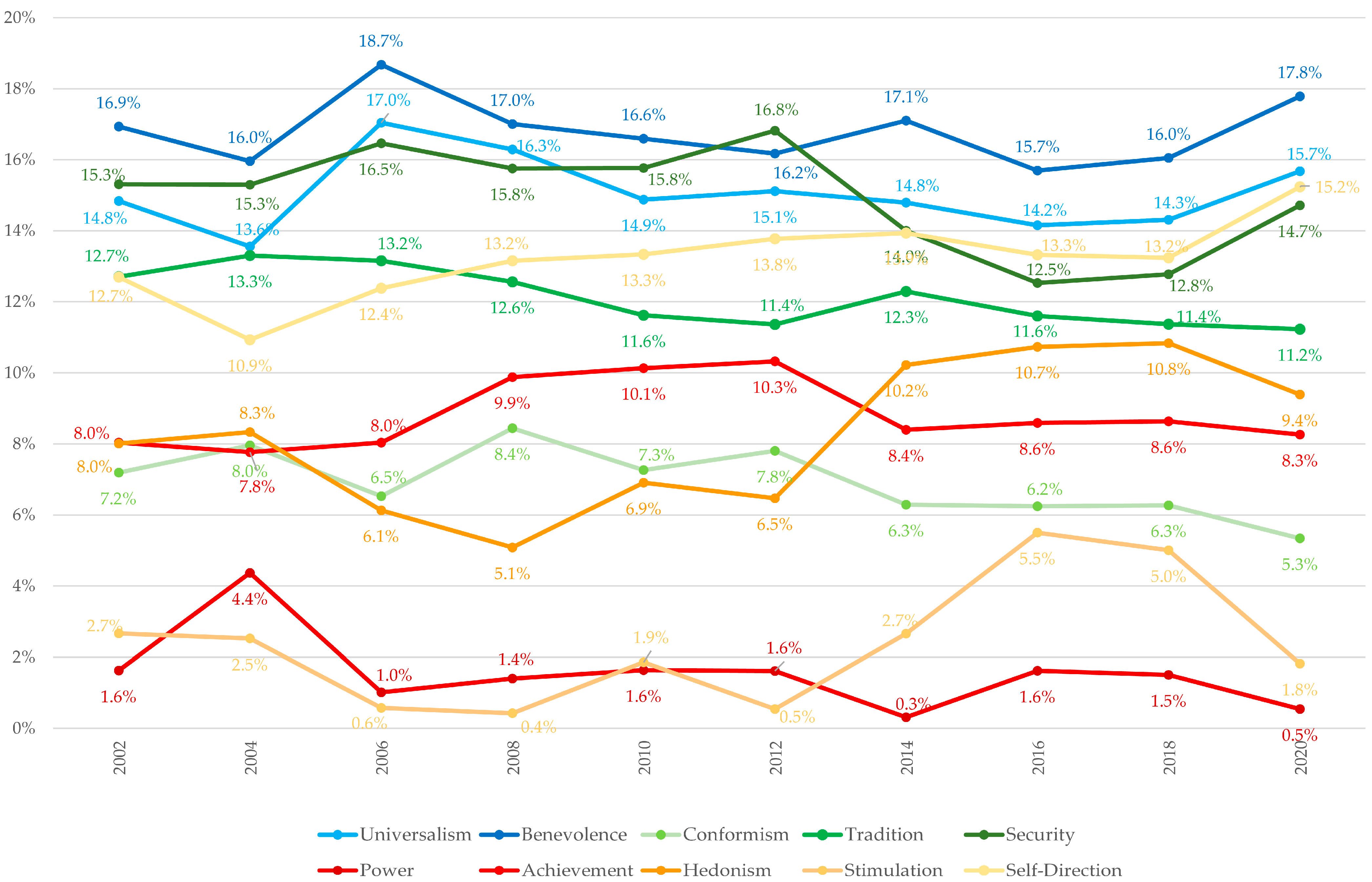

4.3. Changes in the Portuguese Basic Human Values System

4.4. Trends in the Basic Human Values System in Portugal

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BHVs | Basic Human Values |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| CPLP | Community of Portuguese Language Countries |

| ESS | European Social Survey |

| HOV | Higher-Order Values |

| PVQ | Portrait Values Questionnaire |

| RSI | Social Integration Income |

| UEFA | Union of European Football Associations |

| UK | United Kingdom |

References

- Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos. Três Décadas de Portugal Europeu: Balanço e Perspetivas; Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos: Lisbon, Portugal, 2015; Available online: https://ffms.pt/sites/default/files/2022-07/tres-decadas-de-portugal-europeu.pdf?_gl=1*1sgjvs9*_up*MQ..*_ga*MTA0NTY2MzE3MS4xNzQ1MjY0NDI2*_ga_N9RLJ8M581*MTc0NTI2NDQyNi4xLjAuMTc0NTI2NDQyNi4wLjAuMA (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Infraestrutura de Portugal. Planos Estratégicos. Available online: https://www.infraestruturasdeportugal.pt/pt-pt/planos-estrategicos (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Ramos, D.M.; Costa, C.M. Turismo: Tendências de evolução. PRACS Rev. Eletrônica Humanidades Curso Ciências Sociais UNIFAP 2017, 10, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Tourism. Inbound Tourism. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/tourism-statistics/tourism-data-inbound-tourism (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE)-Pirâmides Etárias. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_p_etarias&menuBOUI=13707095&contexto=pe&selTab=tab4 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Pordata. Imigrantes Permanentes Por Sexo, Grupo Etário e Nacionalidade. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/pt/estatisticas/migracoes/imigracao/imigrantes-permanentes-por-sexo-grupo-etario-e-nacionalidade (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Energy Mix—Portugal. Available online: https://www.iea.org/countries/portugal/energy-mix (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Duque, E. Work values in Portuguese society and in Europe. In Trabalho, Organizações e Profissões: Recomposições Conceptuais e Desafios Empíricos. Secção Temática Trabalho, Organizações e Profissões; Marques, A.P., Gonçalves, C., Veloso, L., Eds.; Associação Portuguesa de Sociologia: Lisbon, Portugal, 2013; pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Duque, E. Valores de la sociedad moderna: Una visión del cambio social. Holos 2017, 2, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, J.; Duque, E. Culturas y generaciones: Actitudes y valores hacia la educación, el trabajo y el consumo en tres generaciones de jóvenes españoles. Aposta Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2017, 72, 129–165. [Google Scholar]

- Barata, O. Política Social; Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Políticas: Lisbon, Portugal, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Simões, S. The Impact of Income Support Programs on Transitions to Employment. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Nova, Lisbon, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Saúde Doutor Ricardo Jorge (INSA). Saúde Mental em Tempos de Pandemia—SM-COVID-19: Relatório Final. 2020. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.18/7245 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Pereira, A.; Queirós, C. O stress e as suas consequências na saúde e no bem-estar. In Manual de Psicologia da Saúde; Leal, I., Pais-Ribeiro, J.L., Eds.; Pactor: Lisbon, Portugal, 2021; pp. 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, M.; Navarro Haro, M.; Sousa, B.; Melo, W.; Hoffman, H. Therapists make the switch to telepsychology to safely continue treating their patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: Virtual reality telepsychology may be next. Front. Virtual Real. 2021, 1, 576421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, E. Portugal 2020. An effective policy platform to promote sustainable territorial development? Sustainability 2020, 12, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PNEC. Plano Nacional Energia e Clima 2021–2030; Portugal Energia: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, N.P.; Cohen, S.A.M.; Cantú, W.; Lopes, C. Roteiros e modelos para a identificação de tendências socioculturais e a sua aplicação estratégica em produtos e serviços. Moda Palavra 2021, 14, 228–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laboratório de Gestão de Tendências e da Cultura. Colossos e Decadências: Tendências Socioculturais 2022; Trends and Culture Management Lab: Lisbon, Portugal, 2022; Available online: http://creativecultures.letras.ulisboa.pt/index.php/gtc-trends2022/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Araújo, A.; Araújo, J. A educação nova e o trabalho escolar: Horizonte e polaridades de uma visão educativa. Teor. Educ. 2018, 30, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeira, F. A sociedade de instrução e beneficência A Voz do Operário: Outra forma de fazer política: A propósito da reforma dos serviços escolares (1924–1935). Cad. História Educ. 2020, 19, 87–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimundo, F. Ditadura e Democracia: Legados da Memória; Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.F. Evolutionary modernization theory: Why people’s motivations are changing. Chang. Soc. Personal. 2017, 1, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R.F. Cultural Evolution: People’s Motivations Are Changing, and Reshaping the World; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.G. Os Valores Básicos Humanos e a Influência na Competitividade Turística: Estudo de Caso dos Agentes (re)modeladores do Espaço do Município de Guimarães. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Social Survey (ESS)—Datafile Builder (Wizard). Available online: https://ess.sikt.no/en/data-builder/ (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Schwartz, S. An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2012, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Social Survey (ESS)—Portugal: Documents and Data Files. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20220307233927/https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/docs/round9/fieldwork/portugal/ESS9_questionnaires_PT.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 25, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. Motivation and Personality; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R. The Silent Revolution; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Yankelovich, D.; Zetterberg, H.; Strümpel, B.; Shanks, M. The World at Work. An International Report on Jobs, Productivity and Human Values; Octogon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, L.; Marsh, C. The Protestant work ethic as a cultural phenomenon. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 20, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.L. Atitudes da população portuguesa perante o trabalho. Organ. E Trab. 1995, 14, 33–63. [Google Scholar]

- Vala, J. Valores socio-políticos. In Portugal—Valores Europeus, Identidade Cultural; França, L., Lisboa, I.E.D., Eds.; Instituto de Estudos para o Desenvolvimento: Lisbon, Portugal, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Jesuino, J.C. Processos de Liderança; Livros Horizonte: Lisbon, Portugal, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, A. Dinâmicas dos valores sociais e desenvolvimento socioeconómico. In Contextos e Atitudes Sociais na Europa; Vala, J., Torres, A., Eds.; ICS/Imprensa de Ciências Sociais: Lisbon, Portugal, 2007; pp. 183–218. [Google Scholar]

- Verba, S.; Orren, G.R. The meaning of equality in América. Political Sci. Q. 1985, 100, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halman, L. Capital social na Europa contemporânea. In Valores Sociais: Mudanças e Contrastes em Portugal e na Europa; Vala, J., Villaverde Cabral, M., Ramos, A., Eds.; Instituto de Ciências Sociais: Lisbon, Portugal, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, J.F. Portugal Os Próximos 20 Anos—Valores e Representações Sociais; Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian: Lisbon, Portugal, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, A. Pós-materialismo e comportamentos políticos: O caso português em perspectiva comparativa. In Valores Sociais: Mudanças e Contrastes em Portugal e na Europa; Vala, J., Villaverde Cabral, M., Ramos, A., Eds.; Instituto de Ciências Sociais: Lisbon, Portugal, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Halman, L.; Moor, R. Value shift in Western societies. In The Individualizing Society: Value Change in Europe and North America; Ester, P., Halman, L., Moor, R., Eds.; Tilburg University Press: Tilburg, The Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Halman, L.; Draulans, V. Religious beliefs and practices in contemporary Europe. In European Values at the Turn of the Millennium; Arts, W., Halman, L., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, I.; Hass, G. Racial ambivalence and American value conflict: Correlational and priming studies of dual cognitive structures. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 55, 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vala, J.; Lima, M.E.O.; Lopes, D. Social values, prejudice, and solidarity in the European Union. In European Values at the Turn of the Millennium; Arts, W., Halman, L., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Menezes, I.; Campos, B. The process of value-meaning construction: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 27, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R.; Norris, P.; Welzel, C. Gender equality and democracy. In Human Values and Social Change. Findings from the Values Surveys; Inglehart, R., Ed.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.; Sagie, G. Value consensus and importance: A cross-national study. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2000, 31, 465–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagiv, L.; Schwartz, S.H. Value priorities and subjective well-being: Direct relations and congruity effects. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchione, M.; Schwartz, S.H.; Alessandri, G.; Döring, A.K.; Castellani, V.; Caprara, M.G. Stability and change of basic personal values in early adulthood: An 8-year longitudinal study. J. Res. Personal. 2016, 63, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R.; Schwartz, S.H. Whence differences in value priorities? Individual, cultural, or artifactual sources. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2011, 42, 1127–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. H—From Item to Index. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20190619074933/http://essedunet.nsd.uib.no/cms/topics/1/4/2.html (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- European Social Survey (ESS)—ESS Methodology: Weighting. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20220610093716/https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/methodology/ess_methodology/data_processing_archiving/weighting.html (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Schwartz, S.H. Chapter 7—A proposal for measuring value orientations across nations. In ESS, Questionnaire Development Package of the European Social Survey; European Social Survey: London, UK, 2003; Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20200709074040/http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/docs/methodology/core_ess_questionnaire/ESS_core_questionnaire_human_values.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- SAPO—2008. Available online: https://www.sapo.pt/noticias/artigos/2008 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- SAPO—2014. Available online: https://www.sapo.pt/noticias/artigos/2014 (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- SAPO—2016. Available online: https://www.sapo.pt/noticias/artigos/2016 (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- Vistos e Autorizações de Residência Para Trabalhar em Portugal com Procedimentos Mais Ágeis. Available online: https://www.turismodeportugal.pt/pt/Noticias/Paginas/vistos-e-autorizacoes-de-residencia-para-trabalhar-em-portugal-com-procedimentos-mais-ageis.aspx (accessed on 30 January 2024).

| Study | Context | Dominant Values Identified | Similarities and Differences with the Current Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sagiv and Schwartz [52] | Europe | Universalism, Benevolence | Agreement on the importance of Benevolence. |

| Vecchione et al. [53] | Italy | Conservation, Security | Similarities in Conservation values; differences in Openness to Change. |

| Fischer and Schwartz [54] | International | Universalism, Security, Achievement | Divergences in economic emphasis. |

| Schwartz and Sagie [51] | Europe | Self-Transcendence, Openness to Change, Conservation | Confirms the relationship between economic development and values salience. |

| Human Basic Values | Scores | Difference Score Between Portugal and the Selected Countries | Similarity Index by BHV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portugal | Bulgaria | France | UK | Hungary | Italy | Norway | ||

| Universalism | 15.7% | 2.1% | −0.4% | −0.3% | −0.5% | 0.3% | 1.0% | 2.6% |

| Benevolence | 17.8% | 1.0% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 0.4% | 1.6% | 0.2% | 1.4% |

| Conformity | 5.3% | −4.9% | −2.2% | −2.3% | −2.3% | −4.5% | −6.2% | 4.0% |

| Tradition | 11.2% | 2.4% | −0.2% | 1.4% | 2.8% | −1.3% | 2.5% | 4.1% |

| Security | 14.7% | −2.1% | 2.1% | 1.9% | −4.0% | −1.4% | 3.8% | 7.8% |

| Power | 0.5% | −1.7% | −0.5% | −1.4% | 0.5% | −3.2% | −2.3% | 3.7% |

| Achievement | 8.3% | −4.0% | 4.9% | 1.6% | 1.3% | −2.7% | 2.8% | 8.9% |

| Hedonism | 9.4% | 4.0% | −2.7% | 1.4% | −1.1% | 7.3% | 0.3% | 10.0% |

| Stimulation | 1.8% | −1.5% | −4.0% | −4.7% | 1.2% | 0.8% | −4.4% | 5.8% |

| Self-Direction | 15.3% | 4.7% | 2.6% | 1.6% | 1.8% | 3.2% | 2.4% | 3.1% |

| Similarity Index by Country | 9.6% | 9.0% | 6.6% | 6.8% | 11.7% | 10.0% | - | |

| Sum of the Absolute Differences | 28.2% | 20.3% | 17.3% | 15.7% | 26.2% | 25.8% | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonçalves e Silva, M.; Duque, E. Basic Human Values in Portugal: Exploring the Years 2002 to 2020. Societies 2025, 15, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050137

Gonçalves e Silva M, Duque E. Basic Human Values in Portugal: Exploring the Years 2002 to 2020. Societies. 2025; 15(5):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050137

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonçalves e Silva, Maurício, and Eduardo Duque. 2025. "Basic Human Values in Portugal: Exploring the Years 2002 to 2020" Societies 15, no. 5: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050137

APA StyleGonçalves e Silva, M., & Duque, E. (2025). Basic Human Values in Portugal: Exploring the Years 2002 to 2020. Societies, 15(5), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050137