Exploring the Role of Food Security in Stunting Prevention Efforts in the Bondowoso Community, Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Stunting Prevention Efforts

2.2. Food Security

3. Materials and Methods

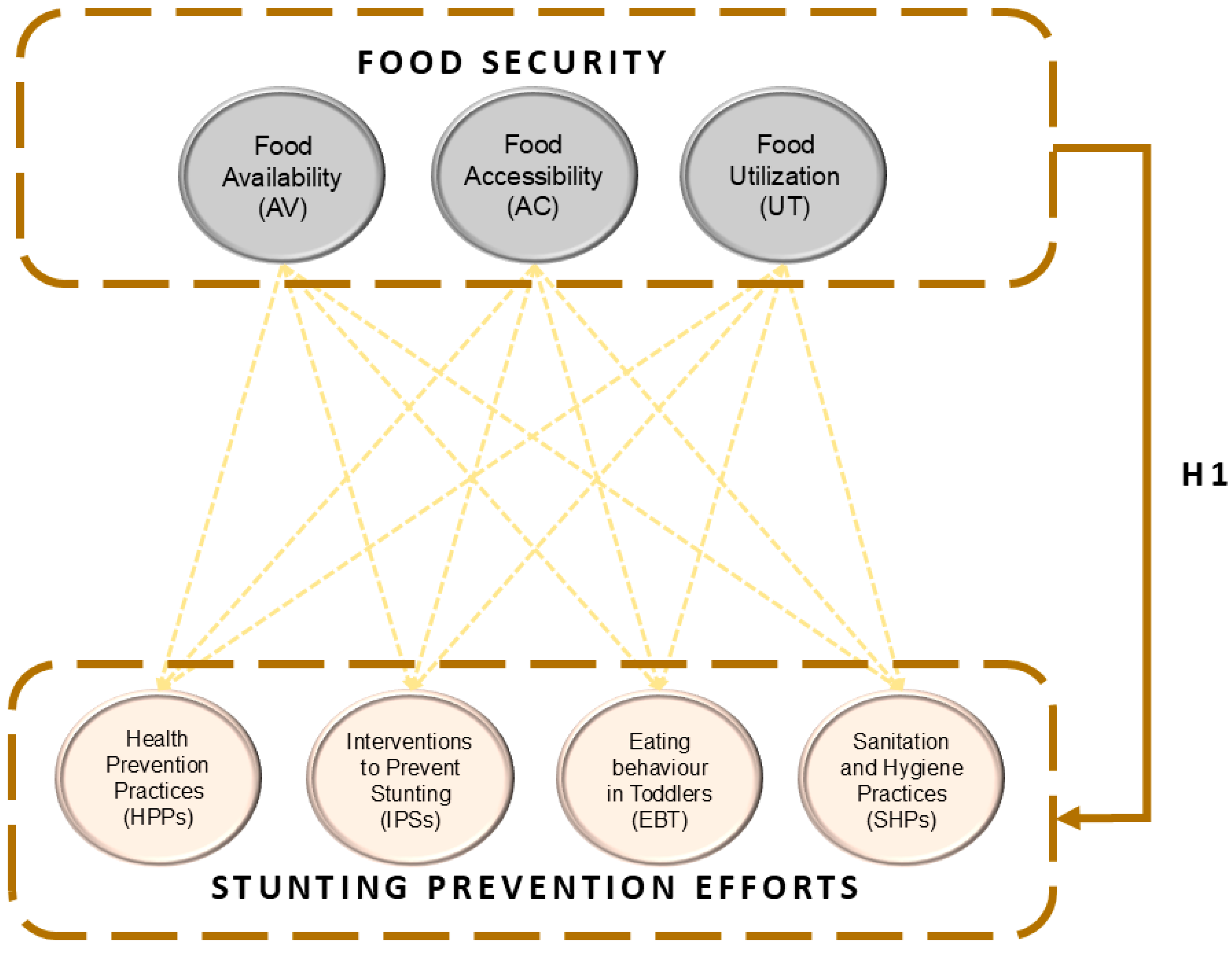

3.1. Research Model Development

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Subjects

3.4. Variables and Indicators

3.5. Sampling Strategy

3.6. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. PLS-SEM Analysis

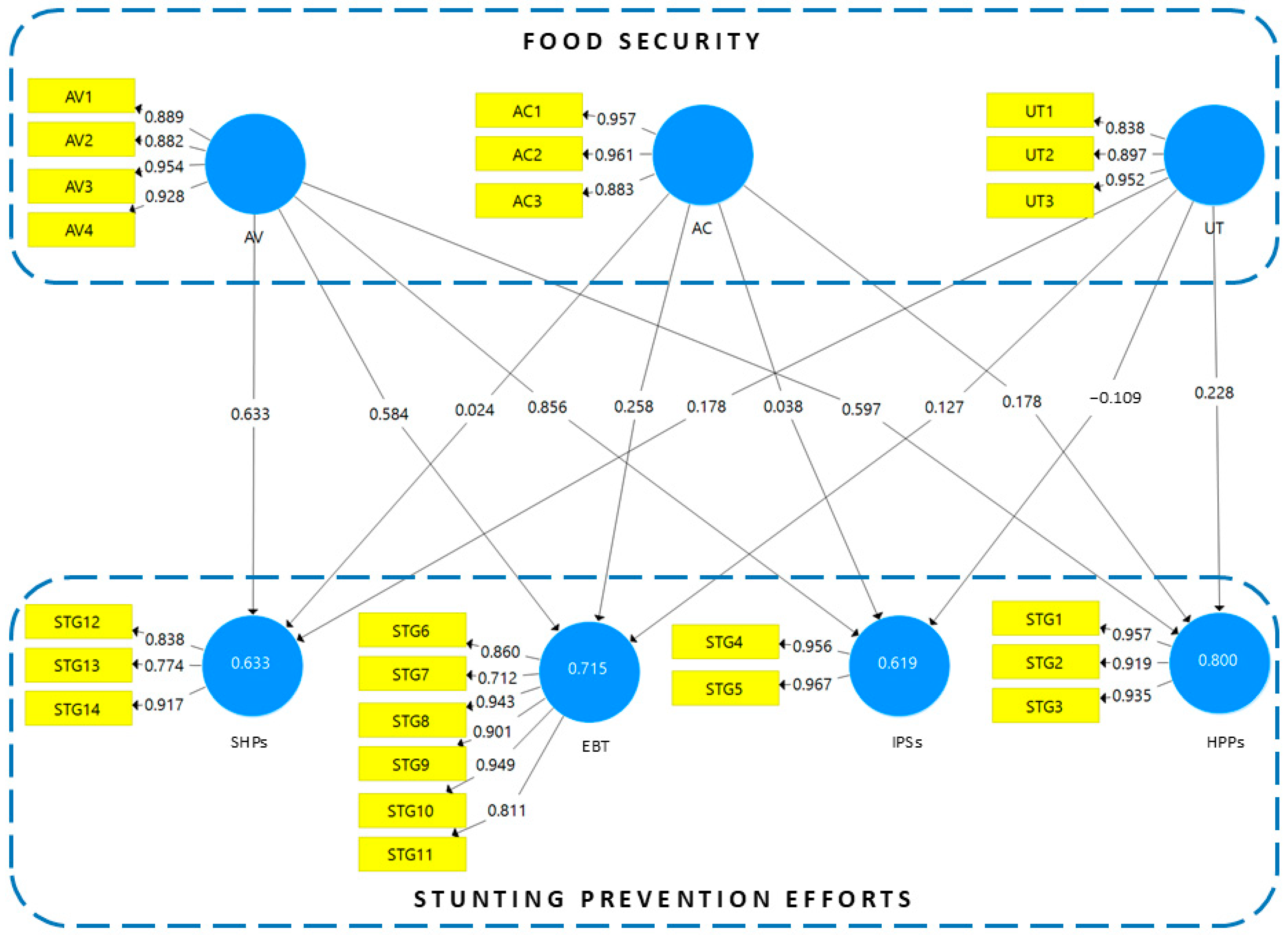

4.1.1. Measurement Model

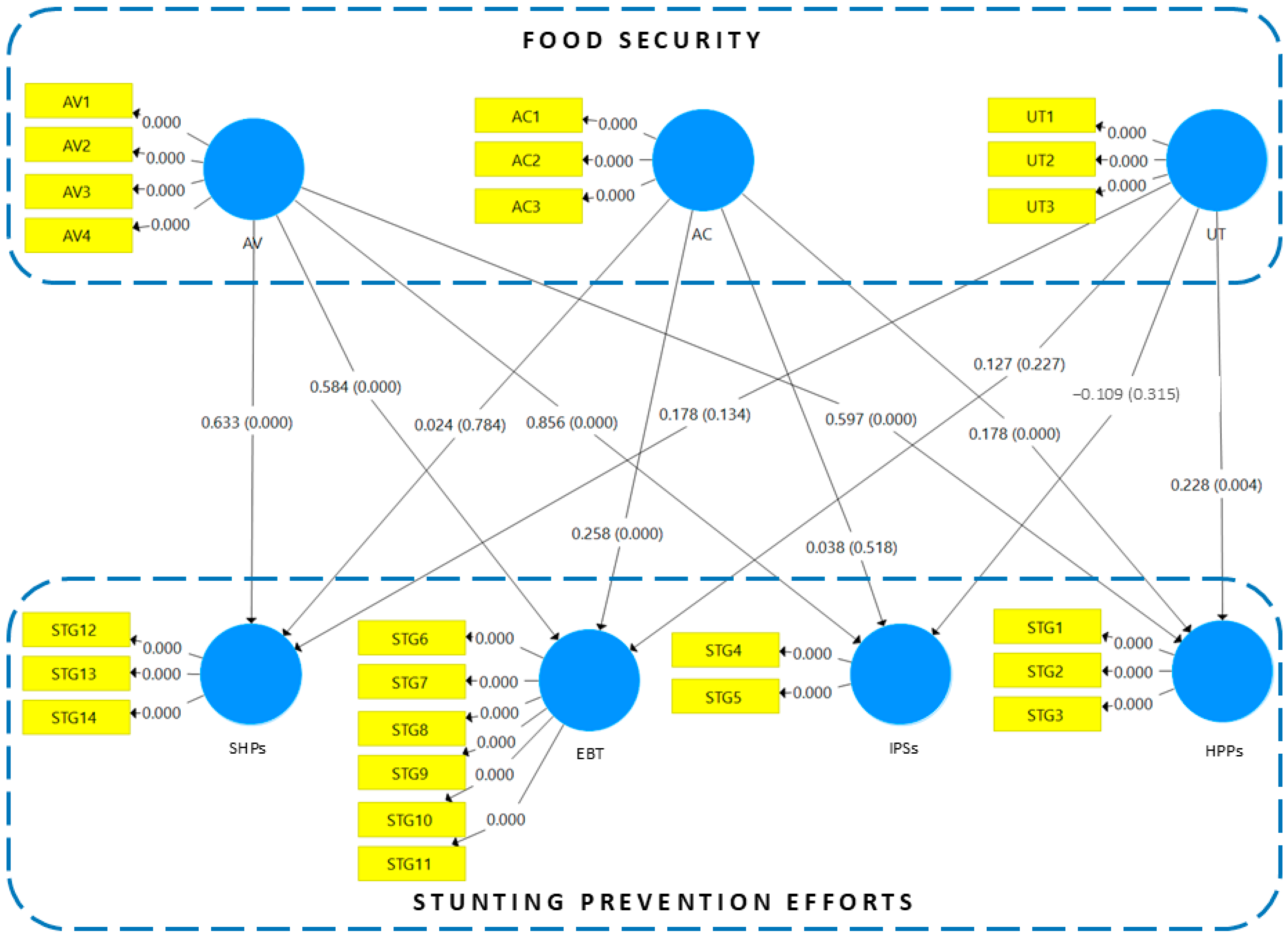

4.1.2. Structural Model

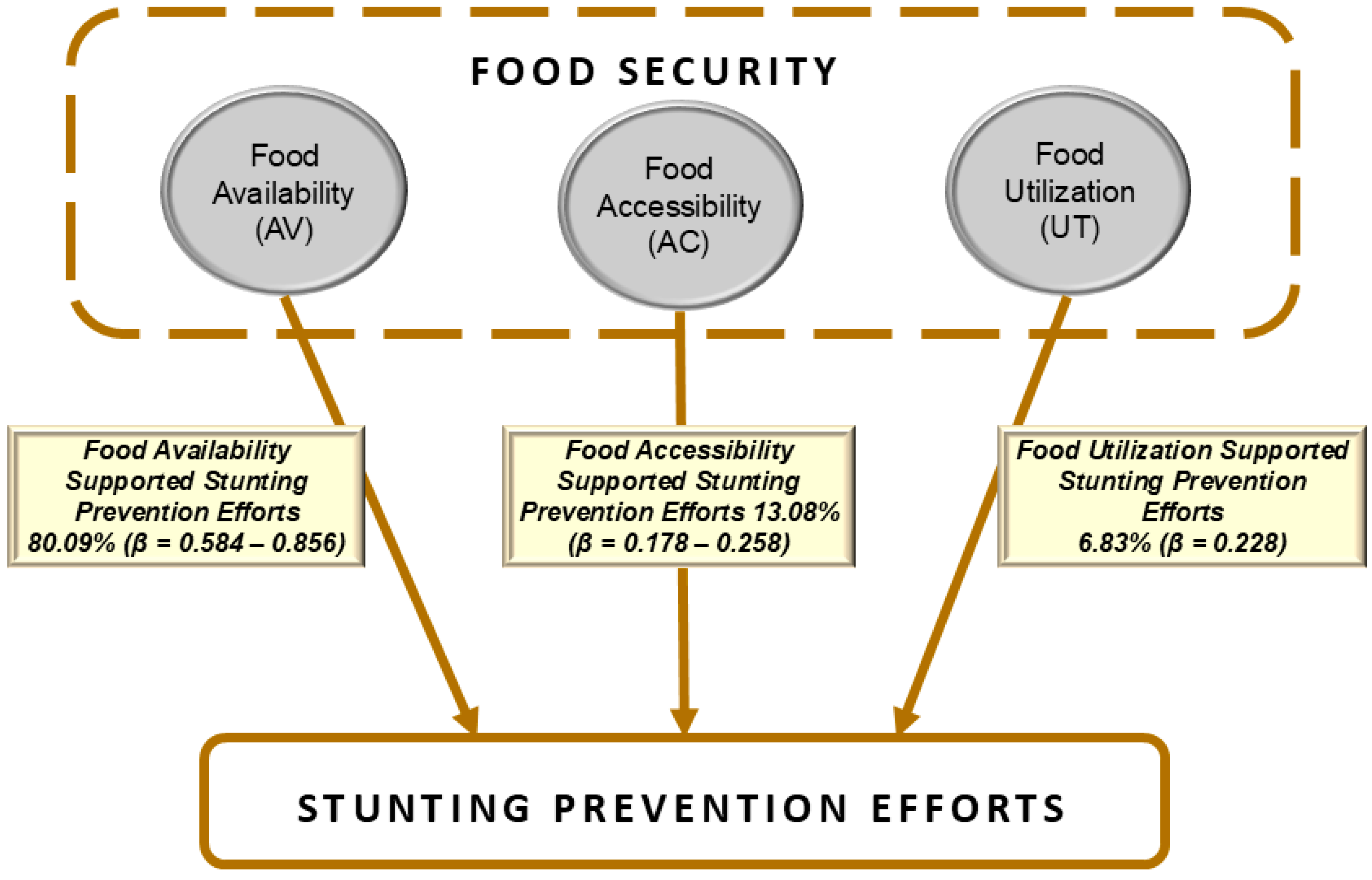

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tjenemundan, D.; Guampe, F.A.; Kayupa, O.O.; Labesani, C.; Alfian, M. Pencegahan Stunting Melalui Penguatan Ketahanan Pangan dengan Metode Partisipasi Aktif pada Masyarakat Desa Kumpi Kecamatan Lembo Kabupaten Morowali Utara. PaKMas J. Pengabdi. Kpd. Masy. 2024, 4, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehena, Z.; Hukubun, M.; Nendissa, A.R. Pengaruh Edukasi Gizi terhadap Pengetahuan Ibu tentang Stunting di Desa Kamal Kabupaten Seram Bagian Barat. Moluccas Health J. 2021, 2, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawaroh, H.; Nada, N.K.; Hasjiandito, A.; Faisal, V.I.A.; Heldanita, H.; Anjarsari, I.; Fauziddin, M. Peranan Orang Tua Dalam Pemenuhan Gizi Seimbang Sebagai Upaya Pencegahan Stunting Pada Anak Usia 4-5 Tahun. Sentra Cendekia 2022, 3, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofiatun, F.D. Shaping Healthy Beginnings: A Systematic Review on the Impact of Parenting Styles on Toddler Nutritional Status. Nurs. Health Sci. J. 2024, 4, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kininmonth, A.R.; Herle, M.; Haycraft, E.; Farrow, C.; Tommerup, K.; Croker, H.; Pickard, A.; Edwards, K.R.; Blissett, J.; Llewellyn, C.H. Reciprocal associations between parental feeding practices and child eating behaviours from toddlerhood to early childhood: Bivariate latent change analysis in the Gemini cohort. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erik, E. Stunting Pada Anak Usia Dini. Etos J. Pengabdi. Masy. 2020, 2, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardani, L.K.; Aulia, V.; Hadhikul, M.; Kardila, M. Risks of Stunting and Interventions to prevent Stunting. J. Community Engagem. Health 2023, 6, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sri Wahyuni, S.; Sutarno, M. Stunting Prevention Intervention in Pregnant Women in 2023. Int. J. Health Pharm. 2024, 4, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, D.P.; Riantina, A.; Nurindalia, B.; Juniarti; Kirana, T.A.; Mayang, D.I.; Idris, H.; Flora, R.; Misnaniarti; Hasyim, H. The Role of Food Security in the Incident of Stunting in Toddlers. Community Med. Educ. J. 2023, 4, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisnoiry, S.; Enjelika, T.N.; Siahaan, B.M.G.; Dupa, L.P. Efektivitas Program Ketahanan Pangan dalam Menangani Kasus Stunting di Kabupaten Asahan Tahun 2024. As-Syirkah Islam. Econ. Financ. J. 2024, 3, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layang, S.; Lailiyah, B.N.; Ishudi, P.C.; Oktavia, R.B.; Wulandari, L.A.; Cahyanti, M.; Wijaya, S.; Kadmaer, K.B.P.; Hasibuan, T.; Agustinus, N.; et al. Food Security for Stunting Prevention with Hydroponic Plant Cultivation in the Tumbang Miri Village. ABDIMAS TALENTA J. Pengabdi. Kpd. Masy. 2023, 8, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardede, P.D.K.; Saraan, I.I.K. Food Security Office Strategies for Addressing Stunting Issues in Medan City. J. Peasants’ Rights 2023, 2, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shofa, N.Z.; Ahmad, B.B.; Raisa, D.; Hadi Kurniyawan, E.; Tri Afandi, A.; Endrian Kurniawan, D.; Rosyidi Muhammad Nur, K. Food Security on The Incidence of Stunting in Agricultural Areas. Nurs. Health Sci. J. 2024, 4, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihite, N.W.; Nazarena, Y.; Ariska, F.; Terati, T. Analisis Ketahanan Pangan Dan Karakteristik Rumah Tangga Dengan Kejadian Stunting. J. Kesehat. Manarang 2021, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabilah, K.; Muhdar, I.N.; Lestari, W.A.; Sariman, S. The Relationship Between Macro-Nutrient Intake, Food Security, and Nutrition-Related Knowledge with the Incidence of Stunting in Toddlers. J. Health Nutr. Res. 2024, 3, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belayneh, M.; Loha, E.; Lindtjørn, B. Seasonal Variation of Household Food Insecurity and Household Dietary Diversity on Wasting and Stunting among Young Children in A Drought Prone Area in South Ethiopia: A Cohort Study. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2021, 60, 44–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, I.P.; Ningsih, W.I.F.; Sari, D.M. The Correlation Between the Household Food Security and the Incidence of Stunting in Toddlers 6-59 Months in Seberang Ulu I Palembang. J. Ilmu Kesehat. Masy. 2023, 14, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazew, T. Risk Factors of Stunting and Wasting among Children Aged 6–59 Months in Household Food Insecurity of Jima Geneti District, Western Oromia, Ethiopia: An Observational Study. J. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 2022, 3981417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, A.J.; Humphrey, J.H. The stunting syndrome in developing countries. Paediatr. Int. Child Health 2014, 34, 250–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surmita, S.; Sekartini, R.; Kekalih, A.; Hendarto, A.; Prawitasari, T.; Novita Chandra, D.; Andriani, R.; Nur Fauziyah, R. Effect of Complementary Feeding Training on Posyandu Cadres Knowledge as Stunting Prevention On 6–12 Months Children. Int. Conf. Interprofessional Health Collab. Community Empower. 2023, 5, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; Kiely, M.; McCarthy, E.K. Influences on the dietary patterns and eating behaviours of 18–36-month-old toddlers in Ireland. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2024, 83, E402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngure, F.M.; Reid, B.M.; Humphrey, J.H.; Mbuya, M.N.; Pelto, G.; Stoltzfus, R.J. Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), environmental enteropathy, nutrition, and early child development: Making the links. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1308, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiyah, S.; Razak, R.; Budiastuti, A.; Sunarsih, E.; Ekasari, R. The Relationship between Personal Hygiene, Maternal Health Status, and History of Diarrhea to Stunting Cases in Indonesia: Systematic Review. Media Publ. Promosi Kesehat. Indones. (MPPKI) 2024, 7, 2886–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, D.P.; Yusuf, S.; Andid, R.; Darussalam, D.; Dimiati, H.; Amna, E.Y. Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) factors associated with stunting among under-fives: A hospital-based cross-sectional study in Banda Aceh, Indonesia. AcTion Aceh Nutr. J. 2024, 9, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiastutik, I.; Pranaka, R.N.; Amaliyah, N.; Hediyanti, G.; Trisnawati, E. The Relation of Infectious Diseases, Water Access, Hygiene Practice, and Sanitation with the Stunting: A Case-Control Study in Sambas Regency. Amerta Nutr. 2024, 8, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhyami, S.; Yunita, H. Sustainable Food Security: An Ethnobotanical Study of Dlingo Village, Grobogan Regency. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1357, 12013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, W.U.; Nisa, K.; Usman, M. Analysis of Food Security Factors in Indonesia using SEM-GSCA with the Alternating Least Squares Method. JTAM (J. Teor. Apl. Mat.) 2024, 8, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuveni, S. The Role of Food Prices and Market Access in Contributing to Hunger in Low-Income Populations. Eximia 2025, 14, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalia, S.; Maria, S.; Fitrianitha, D. The Dynamics of Food security in Indonesia: A Study on the Availability, Affordability, and Utilization of Food in Districts and Cities with the Lowest Index in 2022. Int. J. Econ. 2024, 3, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinia, S.; Choiriyah, I.U. Strategi Program Ketahanan Pangan Dalam Menanggulangi Stunting Di Desa Ketapang Kecamatan Tanggulangin Kabupaten Sidoarjo. Equilib. J. Ilm. Ekon. Manaj. Akunt. 2024, 13, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabibah, I.F.A.; Anggraeny, D.; Irot, R.A. Optimizing the Role of Posyandu Cadres in Providing Nutrition Education and Stimulation as Prevention and Handling of Stunting. ABDIMAS J. Pengabdi. Masy. 2023, 6, 4086–4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruel, M.T.; Alderman, H. Nutrition-sensitive interventions and programmes: How can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? Lancet 2013, 382, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutta, Z.A.; Das, J.K.; Rizvi, A.; Gaffey, M.F.; Walker, N.; Horton, S.; Webb, P.; Lartey, A.; Black, R.E. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: What can be done and at what cost? Lancet 2013, 382, 452–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakaya, Y.; Kadir, S.; Kasim, V.N.A. Implementasi Kebijakan Intervensi Gizi Sensitif dalam Penanganan Stunting di Kabupaten Gorontalo. Health Inf. J. Penelit. 2023, 15, e1244. [Google Scholar]

- Priyono, P. Strategi Percepatan Penurunan Stunting Perdesaan (Studi Kasus Pendampingan Aksi Cegah Stunting di Desa Banyumundu, Kabupaten Pandeglang). J. Good Gov. 2020, 16, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Sub Variable | Note | Indicator | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stunting prevention efforts (STGs) | Health Prevention Practices | HPPs | Health insurance coverage | STG1 |

| Impact of social guidance | STG2 | |||

| Effect of the household environment | STG3 | |||

| Interventions to Prevent Stunting | IPSs | Proactive responses to stunting information | STG4 | |

| Consistency in stunting prevention efforts | STG5 | |||

| Eating Behaviour in Toddlers | EBT | Decrease in instant food consumption | STG6 | |

| Sufficiency of daily energy intake | STG7 | |||

| Provision of exclusive breastfeeding | STG8 | |||

| Adherence to the immunization schedule | STG9 | |||

| Timely introduction of complementary foods | STG10 | |||

| Incidence of infectious diseases | STG11 | |||

| Sanitation and Hygiene Practices | SHPs | Waste management discipline | STG12 | |

| Accessibility of clean water | STG13 | |||

| Instilling handwashing habits in children | STG14 | |||

| Food security (FC) | Food availability | AV | Fulfilment of nutritional food requirements | AV1 |

| Days lacking nutritious food | AV2 | |||

| Challenges in providing complementary foods | AV3 | |||

| Storage of food supplies | AV4 | |||

| Food accessibility | AC | Time invested in acquiring nutritious food | AC1 | |

| Transportation expenses to reach the market | AC2 | |||

| Interruptions in transport or supply chains | AC3 | |||

| Food utilization | UT | Frequency of health facility visits | UT1 | |

| Frequency of serving nutritious meals | UT2 | |||

| Receiving food assistance | UT3 |

| N | S | N | S | N | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 10 | 220 | 140 | 1200 | 291 |

| 15 | 14 | 230 | 144 | 1300 | 297 |

| 20 | 19 | 240 | 148 | 1400 | 302 |

| 25 | 24 | 250 | 152 | 1500 | 306 |

| 30 | 28 | 260 | 155 | 1600 | 310 |

| 35 | 32 | 270 | 159 | 1700 | 313 |

| 40 | 36 | 280 | 162 | 1800 | 317 |

| 45 | 40 | 290 | 165 | 1900 | 320 |

| 50 | 44 | 300 | 169 | 2000 | 322 |

| 55 | 48 | 320 | 175 | 2200 | 327 |

| 60 | 52 | 340 | 181 | 2400 | 331 |

| 65 | 56 | 360 | 186 | 2600 | 335 |

| 70 | 59 | 380 | 181 | 2800 | 338 |

| 75 | 63 | 400 | 196 | 3000 | 341 |

| 80 | 66 | 420 | 201 | 3500 | 346 |

| 85 | 70 | 440 | 205 | 4000 | 351 |

| 90 | 73 | 460 | 210 | 4500 | 354 |

| 95 | 76 | 480 | 214 | 5000 | 357 |

| 100 | 80 | 500 | 217 | 6000 | 361 |

| 110 | 86 | 550 | 226 | 7000 | 364 |

| 120 | 92 | 600 | 234 | 8000 | 367 |

| 130 | 97 | 650 | 242 | 9000 | 368 |

| 140 | 103 | 700 | 248 | 10,000 | 370 |

| 150 | 108 | 750 | 254 | 15,000 | 375 |

| 160 | 113 | 800 | 260 | 20,000 | 377 |

| 170 | 118 | 850 | 265 | 30,000 | 379 |

| 180 | 123 | 900 | 269 | 40,000 | 380 |

| 190 | 127 | 950 | 274 | 50,000 | 381 |

| 200 | 132 | 1000 | 278 | 75,000 | 382 |

| 210 | 136 | 1100 | 285 | 100,000 | 384 |

| No | Village | Number of Stunted Children | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lombok Kulon | 33 | 28 |

| 2 | Tumpeng | 13 | 11 |

| 3 | Jempong | 10 | 9 |

| 4 | Tangsil Wetan | 29 | 25 |

| 5 | Lorok | 16 | 14 |

| 6 | Bendo | 14 | 12 |

| 7 | Pasarejo | 17 | 15 |

| Sample | 113 | ||

| Variables | Indicators | Note | Loading | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Prevention Practices (HPPs) | Health insurance coverage | STG1 | 0.957 | 0.956 | 0.878 |

| Impact of social guidance | STG2 | 0.919 | |||

| Effect of the household environment | STG3 | 0.935 | |||

| Interventions to Prevent Stunting (IPSs) | Proactive responses to stunting information | STG4 | 0.956 | 0.961 | 0.924 |

| Consistency in stunting prevention efforts | STG5 | 0.967 | |||

| Eating Behaviour in Toddlers (EBT) | Decrease in instant food consumption | STG6 | 0.860 | 0.947 | 0.751 |

| Sufficiency of daily energy intake | STG7 | 0.712 | |||

| Provision of exclusive breastfeeding | STG8 | 0.943 | |||

| Adherence to the immunization schedule | STG9 | 0.901 | |||

| Timely introduction of complementary foods | STG10 | 0.949 | |||

| Incidence of infectious diseases | STG11 | 0.811 | |||

| Sanitation and Hygiene Practices (SHPs) | Waste management discipline | STG12 | 0.838 | 0.882 | 0.714 |

| Accessibility of clean water | STG13 | 0.774 | |||

| Instilling handwashing habits in children | STG14 | 0.917 | |||

| Food availability (AV) | Fulfilment of nutritional food requirements | AV1 | 0.889 | 0.953 | 0.835 |

| Days lacking nutritious food | AV2 | 0.882 | |||

| Challenges in providing complementary foods | AV3 | 0.954 | |||

| Storage of food supplies | AV4 | 0.928 | |||

| Food accessibility (AC) | Time invested in acquiring nutritious food | AC1 | 0.957 | 0.954 | 0.873 |

| Transportation expenses to reach the market | AC2 | 0.961 | |||

| Interruptions in transport or supply chains | AC3 | 0.883 | |||

| Food utilization (UT) | Frequency of health facility visits | UT1 | 0.838 | 0.925 | 0.804 |

| Frequency of serving nutritious meals | UT2 | 0.897 | |||

| Receiving food assistance | UT3 | 0.952 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | 0.934 | ||||||

| OF | 0.431 | 0.914 | |||||

| EBT | 0.589 | 0.798 | 0.867 | ||||

| HPPs | 0.576 | 0.857 | 0.847 | 0.937 | |||

| IPSs | 0.339 | 0.785 | 0.771 | 0.711 | 0.961 | ||

| SHPs | 0.407 | 0.787 | 0.799 | 0.803 | 0.696 | 0.845 | |

| OUT | 0.621 | 0.804 | 0.758 | 0.818 | 0.603 | 0.702 | 0.897 |

| Path Coefficients | Original Sample | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | p Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC → EBT | 0.258 | 0.048 | 5.397 | 0.000 | Supported |

| AC → HPPs | 0.178 | 0.043 | 4.173 | 0.000 | Supported |

| AC → IPSs | 0.038 | 0.055 | 0.700 | 0.484 | Not supported |

| AC → SHPs | 0.024 | 0.086 | 0.273 | 0.785 | Not supported |

| OFF → EBT | 0.584 | 0.086 | 6.809 | 0.000 | Supported |

| OFF → HPPs | 0.597 | 0.071 | 8.358 | 0.000 | Supported |

| OFF → IPSs | 0.856 | 0.088 | 9.746 | 0.000 | Supported |

| OFF → SHPs | 0.633 | 0.103 | 6.174 | 0.000 | Supported |

| OUT → EBT | 0.127 | 0.108 | 1.183 | 0.238 | Not supported |

| OUT → HPPs | 0.228 | 0.080 | 2.862 | 0.004 | Supported |

| OUT → IPSs | −0.109 | 0.108 | 1.005 | 0.315 | Not supported |

| UT → SHPs | 0.178 | 0.112 | 1.598 | 0.111 | Not supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prayitno, G.; Auliah, A.; Zuhriyah, L.; Efendi, A.; Arifin, S.; Rahmawati, R.; Nugraha, A.T.; Siankwilimba, E. Exploring the Role of Food Security in Stunting Prevention Efforts in the Bondowoso Community, Indonesia. Societies 2025, 15, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050135

Prayitno G, Auliah A, Zuhriyah L, Efendi A, Arifin S, Rahmawati R, Nugraha AT, Siankwilimba E. Exploring the Role of Food Security in Stunting Prevention Efforts in the Bondowoso Community, Indonesia. Societies. 2025; 15(5):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050135

Chicago/Turabian StylePrayitno, Gunawan, Aidha Auliah, Lilik Zuhriyah, Achmad Efendi, Syamsul Arifin, Rahmawati Rahmawati, Achmad Tjachja Nugraha, and Enock Siankwilimba. 2025. "Exploring the Role of Food Security in Stunting Prevention Efforts in the Bondowoso Community, Indonesia" Societies 15, no. 5: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050135

APA StylePrayitno, G., Auliah, A., Zuhriyah, L., Efendi, A., Arifin, S., Rahmawati, R., Nugraha, A. T., & Siankwilimba, E. (2025). Exploring the Role of Food Security in Stunting Prevention Efforts in the Bondowoso Community, Indonesia. Societies, 15(5), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050135