Consumer Boycotts and Fast-Food Chains: Economic Consequences and Reputational Damage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual Framework of Boycotts

2.1.1. Political Consumerism

2.1.2. Social Justice Theory

2.1.3. Integrating Political Consumerism and Social Justice Theory

2.2. Economic Impacts of Boycotts on ICRs

2.2.1. Financial Consequences

2.2.2. Impact on Corporate Strategy and Behavior

- (1)

- How do boycott actions against international chain restaurants affect their economic performance according to publicly posted textual data, including business statements and news reports?

- (2)

- What arguments do people use to understand why ICR boycotts advance social justice during the Israeli–Palestinian conflict?

- (3)

- What are the discursive strategies used by ICRs in response to boycotts, as evidenced in their public communications?

- (4)

- What are the key themes and emerging trends related to consumer boycotts of ICRs?

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Context

3.2. Research Approach

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

3.3.1. Identification of Boycott Groups and Campaigns

3.3.2. Data Collection Timeframe

3.3.3. Data Sources

“Fast food giant McDonald’s drew the ire of Israel’s critics, especially in the Middle East, when its Israel branch gave thousands of free meals to Israeli troops in October, the month the country launched its bombardment and ground offensive in Gaza, which have now killed more than 27,000 people.”

“The boycott of McDonald’s in Egypt caused 70% sales reduction with data reported by McDonald’s Egypt which demonstrates strong consumer activism power in this region (The information in this sentence originates from Buheji and Ahmed [7] on page 1). This specific quote furnishes empirical evidence about economic effects to strengthen the argument about declining product sales.”

“In Jordan, pro-boycott residents sometimes enter McDonald’s and Starbucks branches to encourage scarce customers to take their business elsewhere. Videos have circulated of what appear to be Israeli troops washing clothes with well-known detergent brands which viewers are urged to boycott.”

“No one is buying these products”, said Ahmad al-Zaro, a cashier at a large supermarket in the capital Amman where customers were choosing local brands instead.

“In Kuwait City on Tuesday evening, a tour of seven branches of Starbucks, McDonald’s and KFC found them nearly empty.”

“In Rabat, the capital of Morocco, a worker at a Starbucks branch said the number of customers had dropped off significantly this week. The worker and the company gave no figures.”

“McDonald’s Corp said in a statement last month that it was “dismayed” by disinformation regarding its position on the conflict and that its doors were open to all. Its Egyptian franchise has underlined its Egyptian ownership and pledged 20 million Egyptian pounds (USD 650,000) in aid to Gaza.”

“The Social Justice and Ethical Consumerism Theme would be supported with a social media post from the BDS movement as follows: Stand with Palestine by joining the boycott of Starbucks and McDonald’s which targets the profit-oriented activities of corporations that condone human rights violations in Palestine.”

“The Facebook post created from Palestinian BDS National Committee model suggests “#BDS #FreePalestine” (hypothetical post based on Palestinian BDS National Committee [79], cited on p. 28). The stated quote presents how activism operates and communicates ideas which match social justice principles.”

3.3.4. Data Cleaning and Preparation

3.3.5. Data Analysis Procedures

4. Results

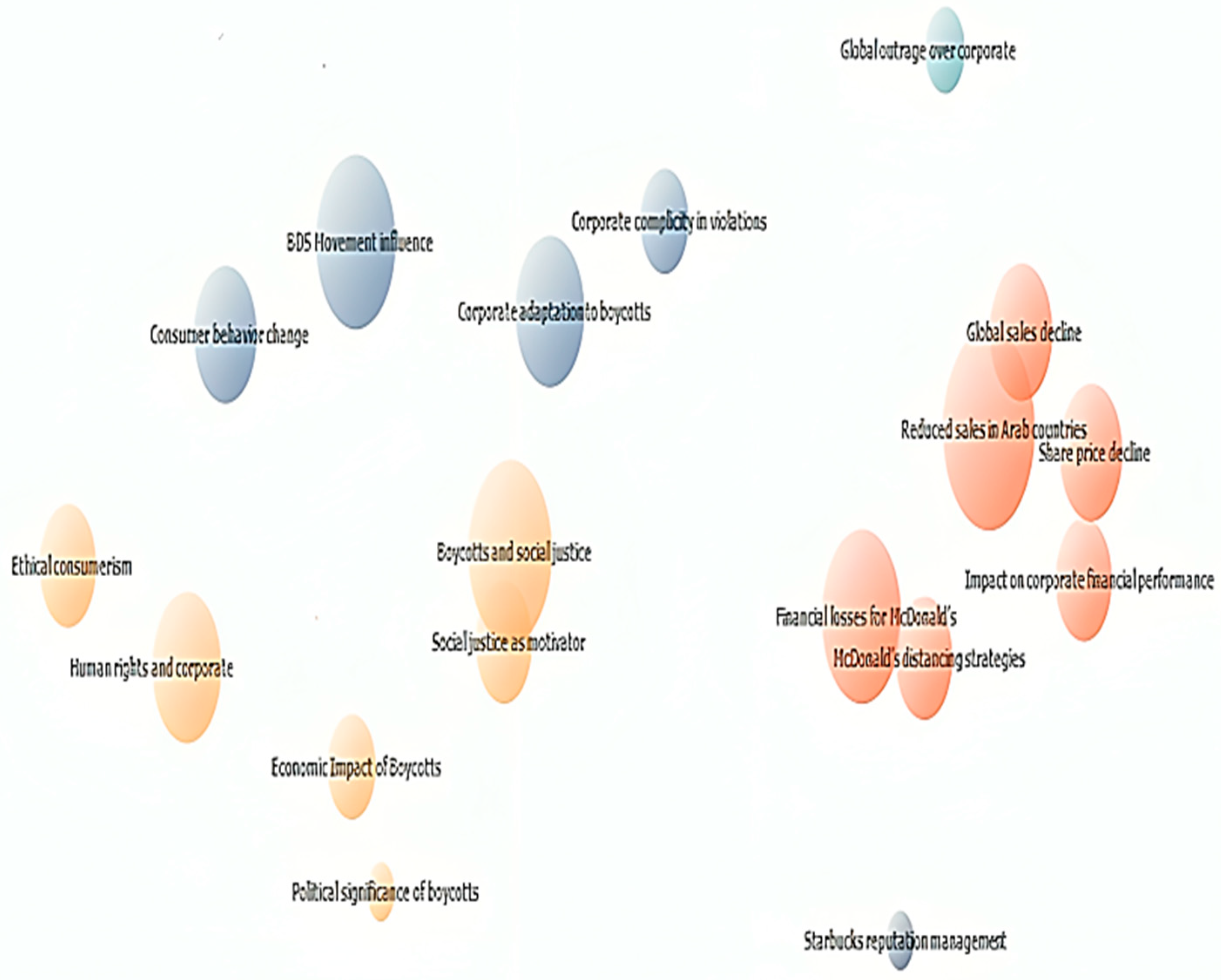

4.1. Distributions of Codes

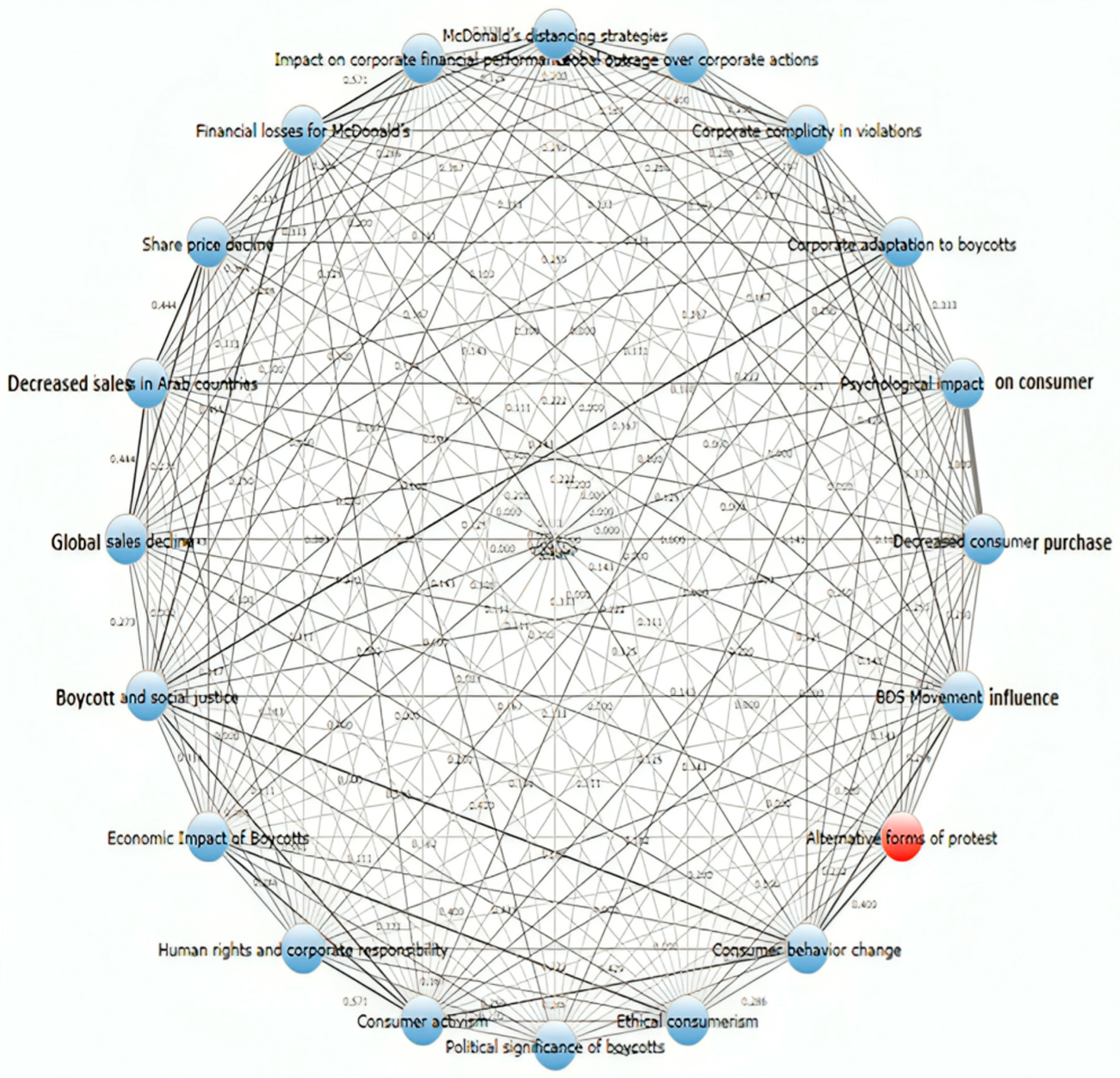

4.2. Co-Occurrence of Codes

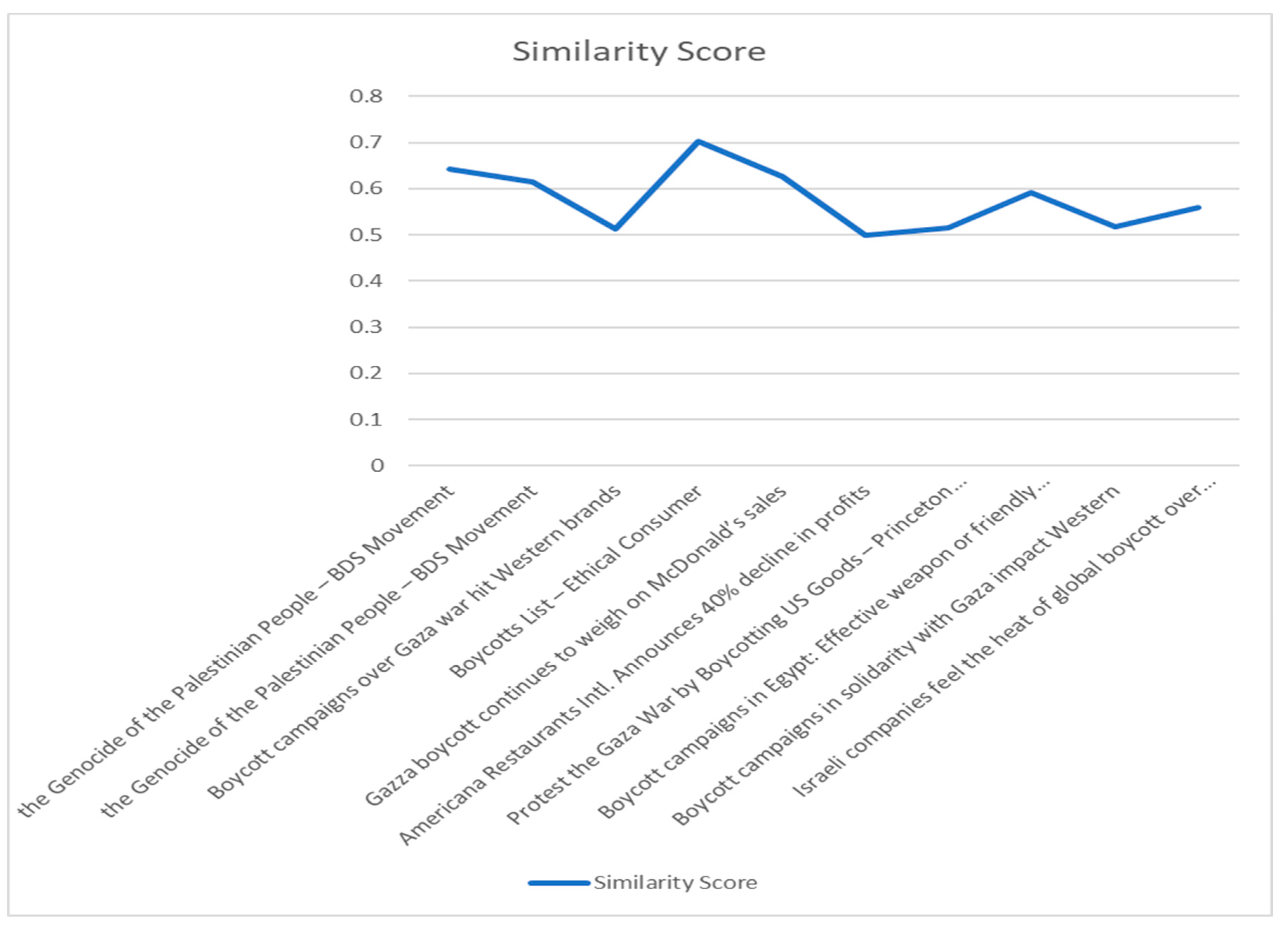

4.3. Case Similarity

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.1.1. Economic Impacts of Boycotts on ICRs

5.1.2. Social Justice and Ethical Consumerism

5.1.3. Corporate Response and Adaptation to Boycotts

5.1.4. Impact of Boycotts on Consumer Behavior

5.1.5. Political and Ethical Dimensions of Boycotts

5.2. Theoretical Implication

5.3. Practical Implication

5.4. Research Limitations and Directions for Future Research

5.5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Sample Codebook Excerpt for Thematic Analysis

| Code | Definition | Example Data Excerpt | Theme |

| Economic Loss | Financial declines together with sales drops and market value losses occur because of boycotts. | “According to Sentosa and Sitepu [6], the company suffered a USD 11 billion loss in market capitalization from boycott campaigns (p. 6).” | Economic Impacts |

| Justice Appeal | Boycott defenses that depend on language related to human rights or justice or equality. | “Social media posts promote the call for McDonald’s boycott as a means to support Palestinian rights alongside justice (hypothetical, based on BDS posts, p. 11).” | Social Justice and Ethical Consumerism |

| Corporate Denial | Companies express their non-compliance with conflicts by refusing to claim participation or accountability. | “TIME reports that the organization (hypothetical, based on TIME [80], p. 20) does not support any political funding initiatives.” | Corporate Response Strategies |

| Consumer Solidarity | Expressions of collective action or empathy for Palestine. | “People boycott as a stand for Palestine even though small efforts matter most to them (hypothetical from social media, p. 21).” | Social Justice and Ethical Consumerism |

References

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Blanchard, L.-A.; Urbain, Y. Peace through Tourism: Critical Reflections on the Intersections between Peace, Justice, Sustainable Development and Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinou, C.S.; Andreou, P.; Nikitara, M.; Papageorgiou, A. Cultural Competence in Healthcare and Healthcare Education. Societies 2022, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.C. The Politics of Tourism in Myanmar. Curr. Issues Tour. 2003, 6, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Conflict and Stability: The Potential of Heritage Tourism in Promoting Peace and Reconciliation. In Heritage and Cultural Heritage Tourism: International Perspectives; Yu, P.-L., Lertcharnrit, T., Smith, G.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 183–191. ISBN 9783031448003. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, P.C.; Everingham, P.; Everingham, C. The Political Economy of the Supercars Newcastle 500 Event. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2023, 4, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentosa, D.S.; Sitepu, N.I. Descriptive Analysis of Israeli Product Boycott Action: Between Fatwas and the Urgency of Compliance. Int. J. Kita Kreat. 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buheji, M.; Ahmed, D. Keeping the Boycott Momentum-from “WAR on GAZA” Till “Free-Palestine”. Int. J. Manag. (IJM) 2023, 14, 205–229. [Google Scholar]

- Patidar, A.K.; Jain, P.; Dhasmana, P.; Choudhury, T. Impact of Global Events on Crude Oil Economy: A Comprehensive Review of the Geopolitics of Energy and Economic Polarization. GeoJournal 2024, 89, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheer, I.; Insch, A.; Carr, N. Tourism Destination Boycotts—Are They Becoming a Standard Practise? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2018, 43, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; McManus, R.; Yen, D.A.; Li, X. (Robert) Tourism Boycotts and Animosity: A Study of Seven Events. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 80, 102792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M. Tourism, Sanctions and Boycotts; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 0429279108. [Google Scholar]

- Rastegar, R.; Breakey, N.; Driml, S.; Ruhanen, L. Does Tourism Development Shift Residents’ Attitudes to the Environment and Protected Area Management? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2024, 49, 921–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Tse, E.C.-Y.; He, Z. Influence of Customer Satisfaction, Trust, and Brand Awareness in Health-Related Corporate Social Responsibility Aspects of Customers Revisit Intention: A Comparison between US and China. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2024, 25, 700–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Alyahya, M.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Ali, M.A.S.; Fathy, E.A.; Fouad, A.M.; Soliman, S.A.E.M.; Fayyad, S. Building Digital Trust and Rapport in the Tourism Industry: A Bibliometric Analysis and Detailed Overview. Information 2024, 15, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomhave, A.; Vopat, M. The Business of Boycotting: Having Your Chicken and Eating It Too. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Jia, B.; Huang, Y. How Do Destination Negative Events Trigger Tourists’ Perceived Betrayal and Boycott? The Moderating Role of Relationship Quality. Tour. Manag. 2022, 92, 104536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.G.; Smith, N.C.; John, A. Why We Boycott: Consumer Motivations for Boycott Participation. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegar, R.; Ruhanen, L. The Injustices of Rapid Tourism Growth: From Recognition to Restoration. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 97, 103504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, L.; Boulianne, S. Political Consumerism: A Meta-Analysis. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 2020, 43, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Consumerism, Tourism and Voluntary Simplicity: We All Have to Consume, But Do We Really Have to Travel So Much to Be Happy? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2011, 36, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capeheart, L.; Milovanovic, D. Social Justice: Theories, Issues, and Movements (Revised and Expanded Edition); Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2020; ISBN 1978806876. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, L. Conceptualizing Political Consumerism: How Citizenship Norms Differentiate Boycotting from Buycotting. Polit. Stud. 2013, 62, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, D. Politics at the Mall: The Moral Foundations of Boycotts. J. Public Policy Mark. 2020, 39, 494–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinou, C.S.; Nikitara, M. The Culturally Competent Healthcare Professional: The RESPECT Competencies from a Systematic Review of Delphi Studies. Societies 2023, 13, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalakas, V.; Melancon, J.P.; Szczytynski, I. Brands in the Eye of the Storm: Navigating Political Consumerism and Boycott Calls on Social Media. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2023, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasarov, W.; Hoffmann, S.; Orth, U. Vanishing Boycott Impetus: Why and How Consumer Participation in a Boycott Decreases Over Time. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 182, 1129–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Kooli, C.; Alqasa, K.M.A.; Afaneh, J.; Fathy, E.A.; Fouad, A.M.; Fayyad, S. Resilience for Sustainability: The Synergistic Role of Green Human Resources Management, Circular Economy, and Green Organizational Culture in the Hotel Industry. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, I.E.; Fathy, E.A.; Magdy, A.; Elsaqqa, M.A.; Kamal Abdien, M. Unlocking Organizational Ambidexterity via the Role of Cross-Functional Coopetition in Quick-Service Restaurants. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2025, 2025, 14673584241313353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abosag, I.; Farah, M.F. The Influence of Religiously Motivated Consumer Boycotts on Brand Image, Loyalty and Product Judgment. Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 2262–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekhil, F.; Jridi, H.; Farhat, H. Effect of Religiosity on the Decision to Participate in a Boycott. J. Islam. Mark. 2017, 8, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.; Brown, F. The Tourism Industry’s Welfare Responsibilities: An Adequate Response? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2008, 33, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Rastegar, R.; Kuhzady, S.; Hall, C.M.; Saarinen, J. Whose Justice? Social (in)Justice in Tourism Boycotts. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2023, 4, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Li, C. Will Consumers Silence Themselves When Brands Speak up about Sociopolitical Issues? Applying the Spiral of Silence Theory to Consumer Boycott and Buycott Behaviors. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2021, 33, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, K.; Gundelach, B. Psychological Roots of Political Consumerism: Personality Traits and Participation in Boycott and Buycott. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 2020, 43, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubuisson-Quellier, S. Anti-Corporate Activism and Market Change: The Role of Contentious Valuations. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2021, 20, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, D.A. Responsible Tourism: A Kierkegaardian Interpretation. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2008, 33, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neureiter, M.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Why Do Boycotts Sometimes Increase Sales? Consumer Activism in the Age of Political Polarization. Bus. Horiz. 2021, 64, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Fayyad, S.; Mohamed, S.A.; Fouad, A.M.; Fathy, E.A. From Data to Delight: Leveraging Social Customer Relationship Management to Elevate Customer Satisfaction and Market Effectiveness. Information 2024, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dynel, M.; Poppi, F.I.M. Caveat Emptor: Boycott through Digital Humour on the Wave of the 2019 Hong Kong Protests. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2021, 24, 2323–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Saarinen, J.; Vo-Thanh, T. Understanding Drivers and Barriers Affecting Tourists’ Engagement in Digitally Mediated pro-Sustainability Boycotts. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 2526–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkey, B. Ethical Consumerism, Democratic Values, and Justice. Philos. Public Aff. 2021, 49, 237–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, E.; Dulsrud, A. Will Consumers Save The World? The Framing of Political Consumerism. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2007, 20, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundelach, B. Political Consumerism as a Form of Political Participation: Challenges and Potentials of Empirical Measurement. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 151, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niva, M.; Jallinoja, P. Taking a Stand through Food Choices? Characteristics of Political Food Consumption and Consumers in Finland. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 154, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo Vázquez, A.; García-Espejo, I. Boycotting and Buycotting Food: New Forms of Political Activism in Spain. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 2492–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, C. Configuring Ethical Food Consumers: Understanding the Failures of Digital Food Platforms. J. Cult. Econ. 2024, 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröckerhoff, A.; Qassoum, M. Consumer Boycott amid Conflict: The Situated Agency of Political Consumers in the Occupied Palestinian Territory. J. Consum. Cult. 2019, 21, 892–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosta, M.; Zabkar, V. Antecedents of Environmentally and Socially Responsible Sustainable Consumer Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorell, C.V. Varieties of Political Consumerism; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 9783319910468. [Google Scholar]

- Sabbagh, C.; Schmitt, M. Handbook of Social Justice Theory and Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; ISBN 1493932160. [Google Scholar]

- Uzar, U. Income Inequality, Institutions, and Freedom of the Press: Potential Mechanisms and Evidence. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M. International Sanctions, Tourism Destinations and Resistive Economy. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2019, 11, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheletti, M.; Stolle, D. Sustainable Citizenship and the New Politics of Consumption. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci 2012, 644, 88–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, J. Ethical Tourism and Development: The Personal and the Political. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2015, 40, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, V. Consumer Boycotts as Instruments for Structural Change. J. Appl. Philos. 2019, 36, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Recreational Hunting: Ethics, Experiences and Commoditization. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2014, 39, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Migacz, S.J. Why Service Recovery Fails? Examining the Roles of Restaurant Type and Failure Severity in Double Deviation With Justice Theory. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2020, 63, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, D.A. Sustainability Ethics in Tourism: The Imperative next Imperative. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 44, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhzady, S.; Siyamiyan Gorji, A.; Rezvani Parkand, R.; Vo-Thanh, T.; Zaman, M. Voices in the Digital Crowd: A Discursive Analysis of Airbnb Boycott. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2024, 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nero, A.; Haya, A. The Power of Boycotts in the Food Industry: A Study of Consumer Behavior amid Conflict. Bachelor Thesis, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Michalon, M.; Martin, M. Tourism(s) and the Way to Democracy in Myanmar. Asian J. Tour. Res. 2017, 21, 150–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illia, L.; Colleoni, E.; Ranvidran, K.; Ludovico, N. Mens Rea, Wrongdoing and Digital Advocacy in Social Media: Exploring Quasi-Legal Narratives during #deleteuber Boycott. J. Public Aff. 2022, 22, e2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Case Study. Sage Handb. Qual. Res. 2011, 4, 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 1315834367. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, T.A. Critical Discourse Analysis. In The Handbook of Discourse Analysis; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 466–485. [Google Scholar]

- Flowerdew, J.; Richardson, J.E. The Routledge Handbook of Critical Discourse Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 1138826405. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, R.; Meyer, M. Methods of Critical Discourse Studies; Introducing Qualitative Methods Series; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781473934252. [Google Scholar]

- Esfehani, M.H.; Walters, T. Lost in Translation? Cross-Language Thematic Analysis in Tourism and Hospitality Research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 3158–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liasidou, S. Representation of Cultural Tourism on the Web: Critical Discourse Analysis of Tourism Websites. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 12, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, M. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. Eval. J. Australas. 2021, 22, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic Analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G. Applied Thematic Analysis; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2021; ISBN 9781529755992. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1994; ISBN 9780803955400. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, P.; Roth, K. Why Companies Go Green: A Model of Ecological Responsiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilber, T.B. Institutionalization as an Interplay Between Actions, Meanings, and Actors: The Case of a Rape Crisis Center in Israel. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palestinian BDS National Committee Act Now Against These Companies Profiting from the Genocide of the Palestinian People. Available online: https://bdsmovement.net/Act-Now-Against-These-Companies-Profiting-From-Genocide (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Rajvanshi, A.; Serhan, Y. What to Know About the Global Boycott Movement Against Israel. Available online: https://time.com/6694986/israel-palestine-bds-boycotts-starbucks-mcdonalds/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Khalil, N.; Fathy, E. Assessing the Accessibility of Disabled Guests’ Facilities for Enhancing Accessible Tourism: Case Study of Five- Star Hotels’ Websites in Alexandria. Int. J. Herit. Tour. Hosp. 2017, 11, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Saarinen, J.; Vo-Thanh, T. Do International Sanctions Help or Inhibit Justice and Sustainability in Tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 2716–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trochim, W.M.K. An Introduction to Concept Mapping for Planning and Evaluation. Eval. Program. Plann. 1989, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikomitis, L.; Wenning, B.; Ghobrial, A.; Adams, K.M. Embedding Behavioral and Social Sciences across the Medical Curriculum: (Auto) Ethnographic Insights from Medical Schools in the United Kingdom. Societies 2022, 12, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenedy, A.; Toruan, L.G.O.L.; Pahlefy, M.R.; Maskilo, O.H.S. Dynamics of Franchise Business Independence: A Case Study of McDonald’s in Indonesia Amidst the Israel-Palestine Conflict. J. Ilm. Wahana Pendidik. 2024, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Shawky, I.; El Enen, M.A.; Fouad, A. Examining Customers’ Intention and Attitude Towards Reading Restaurants’ Menu Labels by Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Int. Tour. Hosp. J. 2019, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Fouad, A. Factors Affecting the Intention to Use Airbnb in Egypt: A PLS-SEM Approach. Int. Tour. Hosp. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.A.A. Military Activism in Malaysia and Its Boycott Towards Mcdonald’s Malaysia: A Case Study of Palestine-Israel Conflict. J. Media Inf. Warf. 2024, 17, 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Stolle, D.; Hooghe, M.; Micheletti, M. Politics in the Supermarket: Political Consumerism as a Form of Political Participation. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 2005, 26, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descubes, I.; McNamara, T.; Claasen, C. E-Marketing Communications of Trophy Hunting Providers in Namibia: Evidence of Ethics and Fairness in an Apparently Unethical and Unfair Industry? Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1349–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindley, A.; Font, X. Ethics and Influences in Tourist Perceptions of Climate Change. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1684–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, M.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wall, G. Authenticity, Ethics and Restoration of an Earthquake-Modified Landscape: Jiuzhaigou World Natural Heritage Site. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 3944–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, E.A.; Salem, I.E.; Zidan, H.A.K.Y.; Abdien, M.K. From Plate to Post: How Foodstagramming Enriches Tourist Satisfaction and Creates Memorable Experiences in Culinary Tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, E.A.; Fouad, A. Testing the Theory of Planned Behavior TPB in Determining Intention and Behavior to Hire People with Disabilities in Egyptian Hotels. J. Tour. Hotel. Mansoura Univ. 2022, 11, 747–819. [Google Scholar]

- Fouad, A.M.; Salem, I.E.; Fathy, E.A. Generative AI Insights in Tourism and Hospitality: A Comprehensive Review and Strategic Research Roadmap. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2024, 2024, 14673584241293124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Zayed, M.A.; Ameen, F.A.; Fayyad, S.; Fouad, A.M.; Khalil, N.I.; Fathy, E.A. Innovating Gastronomy through Information Technology: A Bibliometric Analysis of 3D Food Printing for Present and Future Research. Information 2024, 15, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, A.M.; Abdullah Khreis, S.H.; Fayyad, S.; Fathy, E.A. The Dynamics of Coworker Envy in the Green Innovation Landscape: Mediating and Moderating Effects on Employee Environmental Commitment and Non-Green Behavior in the Hospitality Industry. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2025, 2025, 14673584251324618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, I.E.; Fathy, E.A.; Fouad, A.M.; Elbaz, A.M.; Abdien, M.K. Navigating Green Innovation via Absorptive Capacity and the Path to Sustainable Performance in Hotels. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, E.A.; Fouad, A.M.; Kahly, A.M. Navigating The Path to Sustainability and Overcoming Environmental Barriers in the Egyptian Hotel Industry. In Sustainable Waste Management in the Tourism and Hospitality Sectors; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 245–272. [Google Scholar]

- Fayed, H.; Fathy, E.A. The Impact of Transformational Leadership on Front Office Employees’ Satisfaction and Organisational Commitment. Pharos Int. J. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 1, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Keywords |

|---|---|

| General Keywords | Boycotting McDonald’s/Starbucks in Palestine, Global restaurant chains boycott Palestine, Palestinian boycott international restaurants, Boycott international restaurants Palestine, Palestinian rights boycott global food chains |

| Specific Brand Keywords | McDonald’s Palestine boycott, Starbucks boycott Palestine impact, KFC boycott Palestine, Palestine boycott Burger King, Boycotting Americana Restaurants Palestine |

| Economic and Political Impact Keywords | Financial loss international restaurant boycott Palestine, Economic consequences of restaurant boycott Palestine, Palestinian boycott of global restaurant chains economic impact, Political influence of restaurant boycotts in Palestine |

| Keywords Linking Social Justice and Activism | Boycott for human rights Palestine food chains, Consumer activism boycott Palestine international restaurants, Restaurant boycotts social justice Palestine |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Fayyad, S.; Kooli, C.; Fouad, A.M.; Hamdy, A.; Fathy, E.A. Consumer Boycotts and Fast-Food Chains: Economic Consequences and Reputational Damage. Societies 2025, 15, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050114

Elshaer IA, Azazz AMS, Fayyad S, Kooli C, Fouad AM, Hamdy A, Fathy EA. Consumer Boycotts and Fast-Food Chains: Economic Consequences and Reputational Damage. Societies. 2025; 15(5):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050114

Chicago/Turabian StyleElshaer, Ibrahim A., Alaa M. S. Azazz, Sameh Fayyad, Chokri Kooli, Amr Mohamed Fouad, Amira Hamdy, and Eslam Ahmed Fathy. 2025. "Consumer Boycotts and Fast-Food Chains: Economic Consequences and Reputational Damage" Societies 15, no. 5: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050114

APA StyleElshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., Fayyad, S., Kooli, C., Fouad, A. M., Hamdy, A., & Fathy, E. A. (2025). Consumer Boycotts and Fast-Food Chains: Economic Consequences and Reputational Damage. Societies, 15(5), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050114