Abstract

The 360 tours have become increasingly popular as immersive technologies that allow users to explore environments in a highly interactive way; as such their use and applications have grown exponentially in recent years. Accordingly, this paper aims to review and analyze the existing scientific literature on 360 tours. The analysis delves into primary sources and central themes of research related to 360 tours in the XXI century, offering insights into how these technologies intersect with social behaviors and cultural practices. The aim is to identify key academic documents, institutional contributions, influential authors, institutions, challenges, and dominant research trajectories. Technical aspects related to the creation and implementation of these tours are also analyzed. The results highlight the growing integration of 360 toursin various fields, particularly education, culture, and tourism.

1. Introduction

A 360 tour is composed of a series of 360 images that are grouped together to create a tour that allows users to move along the different images. These are also referred to as 360-panorama tours or 360-pano tours [1]. Each 360 image captures a full 360° field of view. The 360 tours are a cutting-edge approach to exploring and experiencing locations through advanced technology. These tours provide a navigable pathway within a three-dimensional space, enabling viewers to immerse themselves in the environment. By utilizing 360° images of a particular location, a 360 tour offers an engaging experience where users can explore the surroundings and take in a complete panoramic view of the area.

The versatility of 360 tours extends beyond traditional applications, with virtual tours being used for educational purposes, promoting tourist destinations, showcasing cultural sites, and facilitating immersive experiences in general [2,3]. The social impact of 360 tours is substantial, encompassing aspects such as emotional involvement, stress reduction, educational enhancement, and behavioral intentions [4,5]. By leveraging innovative digital tools like 360 tours, cultural institutions and tourism destinations can create dynamic and informative virtual experiences that contribute to the preservation and dissemination of cultural heritage while providing engaging and immersive experiences for visitors [6,7,8,9].

Using point-tracking technology and multimedia tools, virtual tours have been instrumental in introducing users to different environments. The concept of a 360 tour began to gain traction with the increasing applications of virtual reality (VR) technology [10]. While VR technologies offer a more immersive and interactive experience, the accessibility and ease of use of 360 tours constitute an important advantage for practical applications, as 360 tours require minimal equipment and technical expertise compared to VR [11]. A user can navigate through the tour using a smartphone, tablet, or computer, by the ‘hot spots’. These are elements to navigate to different areas or access to additional information.

The terms “virtual tour”, “3D tour”, and “360 tour” are often used interchangeably, but they have distinct meanings. A virtual tour provides an experience where users can explore a specific location or environment using virtual technology. By contrast, a 3D tour refers to an interactive simulation within a computer-generated three-dimensional environment [12]. In essence, a “virtual tour” encompasses a fully immersive exploration of a place, while a “3D tour” emphasizes the three-dimensional digital representation, and a “360 tour” focuses on providing a panoramic 360° view of the surroundings.

It is also crucial to distinguish between two terms that are often confused: “360 tour” and “360 video”. A 360 Tour is an interactive experience where users can explore a specific environment or location through 360° views, allowing them to navigate in various directions and choose their own path. By contrast, a 360 video enables the viewer to adjust their perspective and viewing angle to explore different parts of the recorded scene but does not permit changing the trajectory [13]. While 360 videos are more limited due to the inability to select a path, they are gaining popularity as many social media platforms and video hosting sites, such as YouTube and Facebook, support 360 content. This accessibility makes it easier to share these immersive experiences with a broad audience [14].

Although there is no exact start date, the beginnings of 360 tours can be traced back to the 1990s, when the first virtual tour software was developed [1]. Initially, these tours relied on simple static photographs taken from a single point, which were then stitched together to create a 360° panoramic view. These early images provided a wide view of the environment, but lacked interactive browsing capabilities. As technology advanced, new tools and software emerged, enabling users to interact with panoramic photos in more accessible ways. Multiple images were combined to create virtual tours, allowing users to navigate through various viewpoints within a given environment, thereby offering a more comprehensive experience [15]. Over time, capturing 360° images in real-time has become increasingly easier [16,17]. Specialized cameras and apps now enable users to quickly and easily capture high-quality 360° images [18,19]. With the growing popularity of 360 tours, many specialized platforms and tools have been developed to streamline the creation, management, and publishing of these tours [1,20,21,22]. These platforms offer advanced features such as map integration, points of interest, additional information, and the ability to share and collaborate on tours. As 360 tours continue to evolve, they hold promise for transforming how individuals interact with and understand their social and cultural environments.

One of the most popular examples of 360 tours is Google Maps [23,24,25,26]. This platform allows users to view maps of the world, search for addresses and points of interest, and navigate streets using 360° views. Another Google application, Google Earth, allows users to view the Earth from any angle and explore remote and exotic locations [27,28,29]. In the real estate sector, 360 tours are often used to showcase properties for sale and rent. This feature allows users to explore properties through immersive 360° views and access detailed information about each listing, revolutionizing the home search process and allowing real estate agents to present properties to clients in a more engaging way [30,31,32]. Similarly, Airbnb uses 360 tours to allow users to explore rental accommodations, providing a comprehensive view of the spaces [33,34,35]. National Geographic provides a range of 360 tours, including those of Yosemite National Park, the Great Barrier Reef, and the Everglades National Park [36]. NASA also offers 360 tours of some of the most famous sites in space. Several museums, including the Louvre, the British Museum, and the Prado Museum, offer 360 tours that allow users to explore their art collections through immersive 360° views [37,38]. This initiative has made it possible for people around the world to access the museums’ works of art without having to be physically present. As technology continues to advance, 360 tours are expected to continue to evolve [39].

Several reviews of 360 tours can be found in the academic literature. Gafar et al. [40] focused on 360 panoramic virtual tours as a medium for place promotion. Chen et al. [41] conducted a literature review on virtual technology in hospitality and tourism, highlighting the increasing applications of 360 tours in hotel and destination marketing. Hamilton et al. [42] focused on immersive virtual reality as a pedagogical tool in education, emphasizing quantitative learning outcomes and experimental design. Shadiev et al. [43] delved into a review of research on 360 video and its applications in education, shedding light on the educational potential of this technology. Snelson and Hsu [20] reviewed the use of 360 video in education, highlighting the advantages and disadvantages of such tools. Ranieri et al. [44] also conducted a scoping review of empirical research to explore the integration of 360 videos in educational contexts, with the goal of developing a systematic and evidence-based approach to its educational use.

The present work seeks to explore and analyze the existing literature on 360 tours through both a qualitative and a quantitative analysis. A range of factors, including academic documents, institutional contributions, influential authors, and the broader societal impacts, are examined. The analysis delves into the primary sources and central themes of the research related to 360 tours, offering insights into how these immersive technologies intersect with social behaviors and cultural practices. The objective is to map out the dominant research trajectories, identify enduring and emerging challenges, highlight key institutions and researchers, and pinpoint both foundational and contemporary research topics. Technical aspects related to the realization of the tours have also been analyzed. The study provides significant progress and added value by providing a comprehensive overview of the existing literature on 360 tours, mapping the dominant research trajectories and summarizing key contributions from 2000 to 2023. In addition, the examination of technical aspects related to the creation and implementation of 360 tours provides practitioners with valuable insights for developing more effective virtual experiences. This can contribute data and ideas to enrich the discourse surrounding these techniques.

2. 360 Images and 360 Tours

The 360 tour development process involves two main phases, the creation of the 360 images and the development of the 360 tours themselves. Both processes are described below.

2.1. Creation of 360 Images

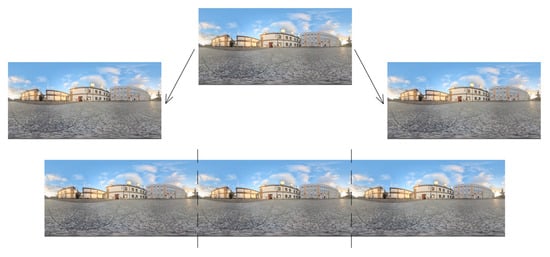

A 360 image, as shown in Figure 1, captures an entire 360° field of view. These images are produced using specialized cameras with wide-angle lenses and/or software that stitches together multiple photos.

Figure 1.

Example of a 360 image. Source: own source.

A 360 image is seamless and identical on all sides. As illustrated in Figure 2, these images can be seamlessly joined due to the symmetry across its sides. This characteristic ensures that both sides align perfectly, allowing for seamless integration without noticeable transitions. Similarly, both the top edge and the bottom edge actually constitute a single point when viewed in a 360° viewer.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the equality of both sides of the 360 image. Source: own source.

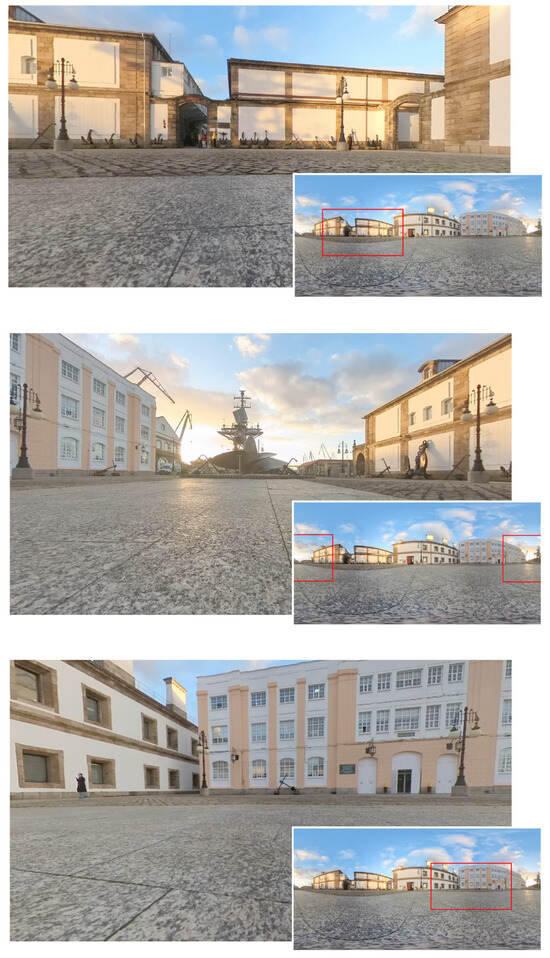

To view a 360 image, there are specific viewers that allow users to move and change their perspective within the image. This process is illustrated in Figure 3, which shows four screen captures obtained by horizontally rotating the previous 360 image. Each perspective is shown in the image in the bottom right corner. In the same way, moving to the left, right, up, or down allow the user to see the environment from different angles.

Figure 3.

Different perspectives of a 360 image obtained through a 360 viewer. Source: own source.

It is important to highlight the difference between 360 images and spherical images. Despite the fact that both provide a 360° perspective, the difference is that a spherical image captures a complete 360° view both horizontally and vertically, resembling a crystal ball that encompasses the entire surroundings from the photographer’s point of view [45]. This allows the viewer to look in any direction within the scene. Conversely, a 360 image also covers a full 360° horizontal view but does not always include vertical coverage, meaning it may not fully represent a spherical perspective. It is also essential to distinguish between a panoramic image and a 360 image. A panoramic image captures a broad, horizontal view of a landscape or scene, offering a wider aspect ratio than a typical photo. However, unlike a 360 image, which provides a full, immersive 360° view, a panoramic image is usually limited to a single horizontal perspective without offering vertical coverage or a complete surrounding view [46].

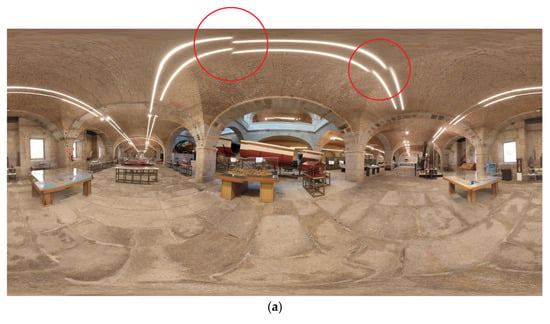

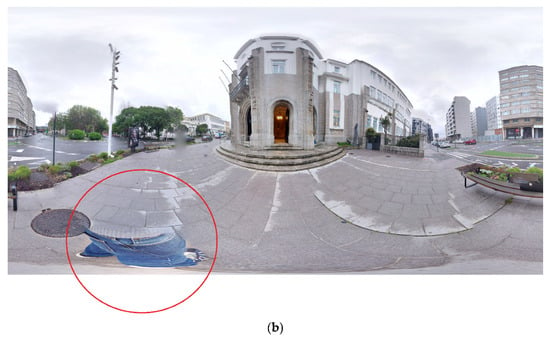

In recent years, smartphones have become incredibly powerful tools. Most modern devices can make 360° images by stitching several ordinary images together through an appropriate app. As an example, Figure 4a was created assembling 29 ordinary photographs. However, the main challenge lies in properly assembling these images, as any movement of the device can result in misaligned images. Other problems can be improper stitching of the different parts, as shown in the red circles of Figure 4a, or the person taking the picture coming out, red circles of Figure 4b, since the use of a tripod with a timer or shutter release makes it unfeasible to take so many pictures for a single 360. However, it is important to note that some of these defects can be solved by graphic editing, which, on the downside, requires graphic editing skills on the part of the user.

Figure 4.

The 360 Tour images taken with smartphones; (a) defect due to bad stitching between the different sub-images; (b) defect due to the apparition of the person who is taking the photograph. Source: own source.

To create 360 images using a smartphone, it is necessary to select an appropriate application. Most of these apps operate on a similar principle: after capturing a series of images, the app stitches them together to form a single 360 image. Additionally, some apps offer editing tools to fine-tune the image, and many provide options to share or upload the 360 image to social media [1,21]. These apps vary in features, ease of use, and device compatibility. While smartphone-based virtual tour creators might not match the professionalism of PC-based software, some deliver excellent results. Some of the most well-known smartphone apps to create 360 images and/or tours include Google Street View, Cardboard Camera, 360 Photo sphere Camera, Panorama 360, 360 Panorama, 360 Camera, DMD Panorama, RoundMe, Kuula, iStaging, 3D Vista VR, SeekBeak, HoloBuilder, and fyuse—3D Photos, among others.

2.2. Creation of 360 Tours

After creating the 360 images, software or applications are required to assemble them into interactive tours. This section focuses on the various software, smartphone applications, and online tools available for creating these immersive tours.

The development of software for creating 360° virtual tours has gained significant traction in recent years, driven by advancements in technology and an increasing demand for immersive experiences across various sectors [1,4]. The 360 Tour industry offers a wide range of software and platforms for creating and hosting immersive virtual tours. This section synthesizes recent studies that explore the capabilities, applications, and effectiveness of 360 Tour software. In the origins of 360°, in the mid-1990s, early software allowed for the creation of static panoramic images stitched together to form a cohesive view of a location [47]. Over the years, the technology has evolved significantly, enabling the integration of interactive elements and multimedia content, which enhances user engagement and experience. The accessibility of software tools has expanded the ability of users to create virtual tours, making it feasible for a wider audience to explore various locations virtually [22]. This democratization of technology has been particularly beneficial in contexts where physical access is restricted, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic [48]. Widely used software include 3DVista [1,49,50,51,52], Pano2VR [53,54,55,56], HoloBuilder [57], Mozilla Hubs [58,59,60], Cupix [61,62,63], Unity [49,64,65], Panotour Pro, VPiX Virtual Tour Creator, Garden Gnome Pano2VR, Tourweaver, Marzipano, 360 VR Studio, and krpano, among others.

Nemtinov et al. [66] discussed the integration of various software environments to create educational content, specifically highlighting the use of 3D modeling and virtual tour software to enhance learning experiences. They emphasized the effectiveness of using specialized tools, like Twinmotion and 3DVista Virtual Tour Pro, in developing immersive 360° tours for educational purposes, thus providing a framework for creating engaging virtual environments. Cardona et al. [21] provided a comprehensive overview of virtual tour software by categorizing different types based on technical attributes and usability, which is essential for understanding the landscape of 360 Tour creation tools. They also identified current research trends and gaps, informing future developments in this area. Grosser et al. [53] discussed the development and effectiveness of the VR4Hydro tool, a virtual reality platform utilizing 360° panoramas for hydrological education, demonstrating its value as a supplement to traditional field trips, particularly during restrictions like those imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Their study highlights the potential of software for creating 360 tours to enhance learning experiences and accessibility in educational contexts. Iglesias et al. [60] discussed a web-based virtual tour pipeline that enables organizations to create interactive 360 tours with minimal coding, utilizing tools like Marzipano and Hubs. Their work contributes a software framework and documentation that facilitates the development of low-cost, shareable virtual experiences for prospective students. Nemtinov et al. [52] discussed the use of software environments, including 3D Vista Virtual Tour Pro, for creating immersive virtual production spaces, which is relevant for developing 360 tours in educational contexts. This highlights the application of such software in visualizing complex environments, thereby supporting the task of creating engaging 360° experiences.

The comparative effectiveness of different virtual tour formats has been reported in several studies. One can refer to Kalving et al. [67], who conducted a heuristic evaluation of VR and desktop 360 video museum tours, identifying key dimensions, such as authenticity and interaction, that contribute to the overall user experience. This comparative analysis is crucial for understanding how different technologies can be leveraged to create more effective virtual tours. Rahaman et al. [1] developed an exhaustive overview of the current software and online services to create 360 tours.

There are also online applications that enable users to create 360 virtual tours without needing to install any software on their PC or smartphone. These web-based platforms provide a convenient and accessible way to build interactive virtual tours directly from an internet browser. With these online applications, users can create and share immersive virtual tours using just a web browser, making them accessible from any device with an internet connection. These platforms often feature user-friendly interfaces, making them suitable for users with varying levels of technical expertise. Additionally, they offer hosting options, allowing users to share their virtual tours with others or embed them on their website or educational platforms. Some popular online applications for creating 360 virtual tours include Tour Creator, Kuula, RoundMe, SeekBeak, iStaging, Cupix, My360, ThingLink, HoloBuilder, StoryMap JS, and Unity3D, among others.

3. Overview of the Academic Works Related to 360 Tours

This section provides an overview of the existing academic literature on 360 tours. The information used in this study was obtained from the Scopus database. The documents were obtained by selecting “360 tour” in the fields “Article Title, Abstract, Keywords”. The period analyzed was 2000–2023. All the article titles and abstracts were reviewed to ensure that they comply with the subject matter analyzed in this study. A total of 269 works were obtained. From these, four were eliminated since they refer to a whole congress or conference instead of a single work. These works were “The 28th International Geological Congress (Washington, 1989)”, “Resumee on the 42nd mechanical working and steel processing conference”, “IS and T international symposium on electronic imaging science and technology”, and “SpaceOps 2010 conference”. The most important information is summarized in Table 1. As can be seen in this table, a total of 265 works were analyzed. These papers come from 217 sources. The annual growth rate is 19.31%, which indicates a high increase in the number of documents with the passage of the years. The average age of the documents is too low, 4.54 years, since most of the papers have been published recently. The average number of citations per document is 8.257. A total of 854 authors were analyzed, with an average of 3.61 authors per document, and an international co-authorship of 14.5%.

Table 1.

Main information.

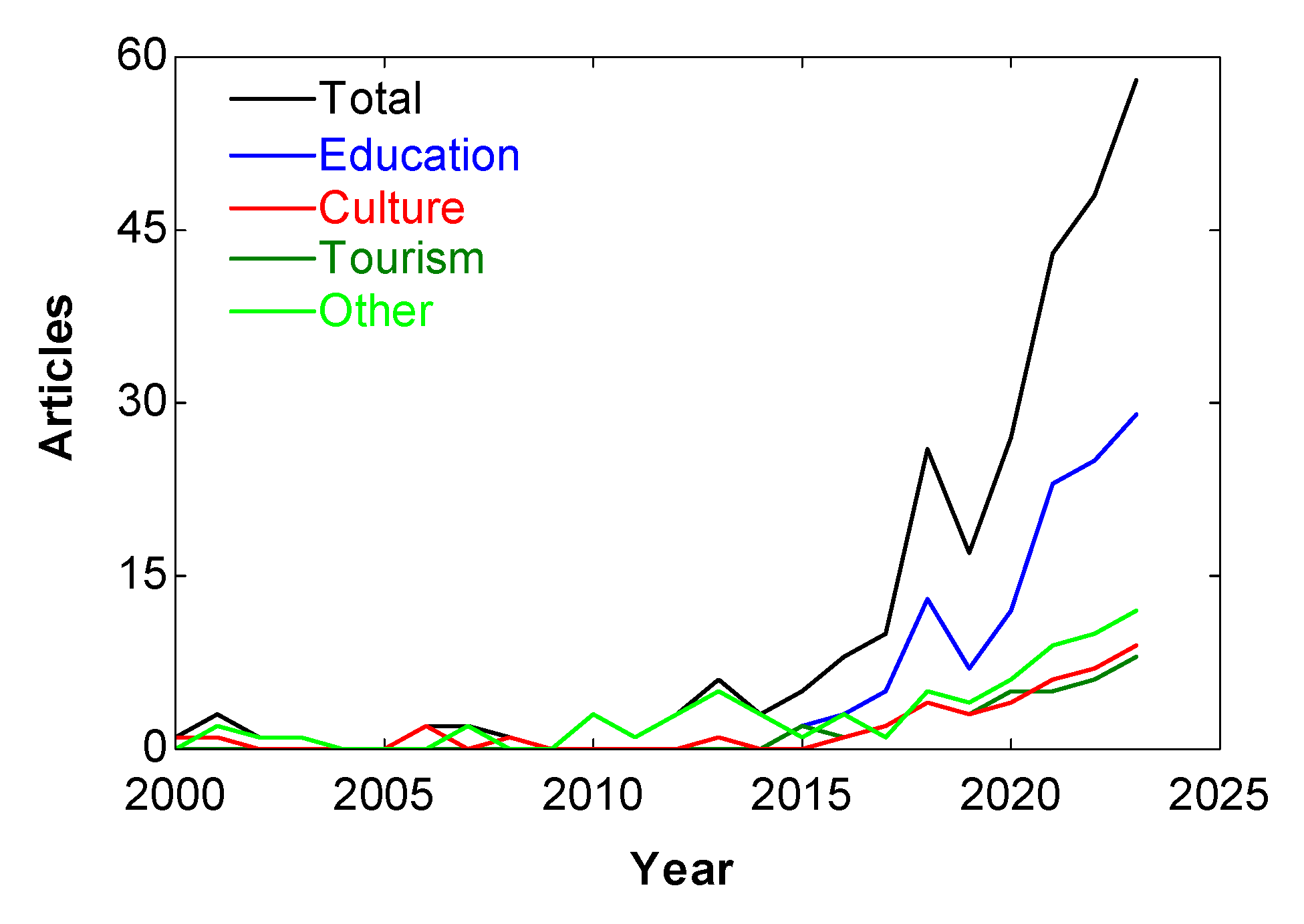

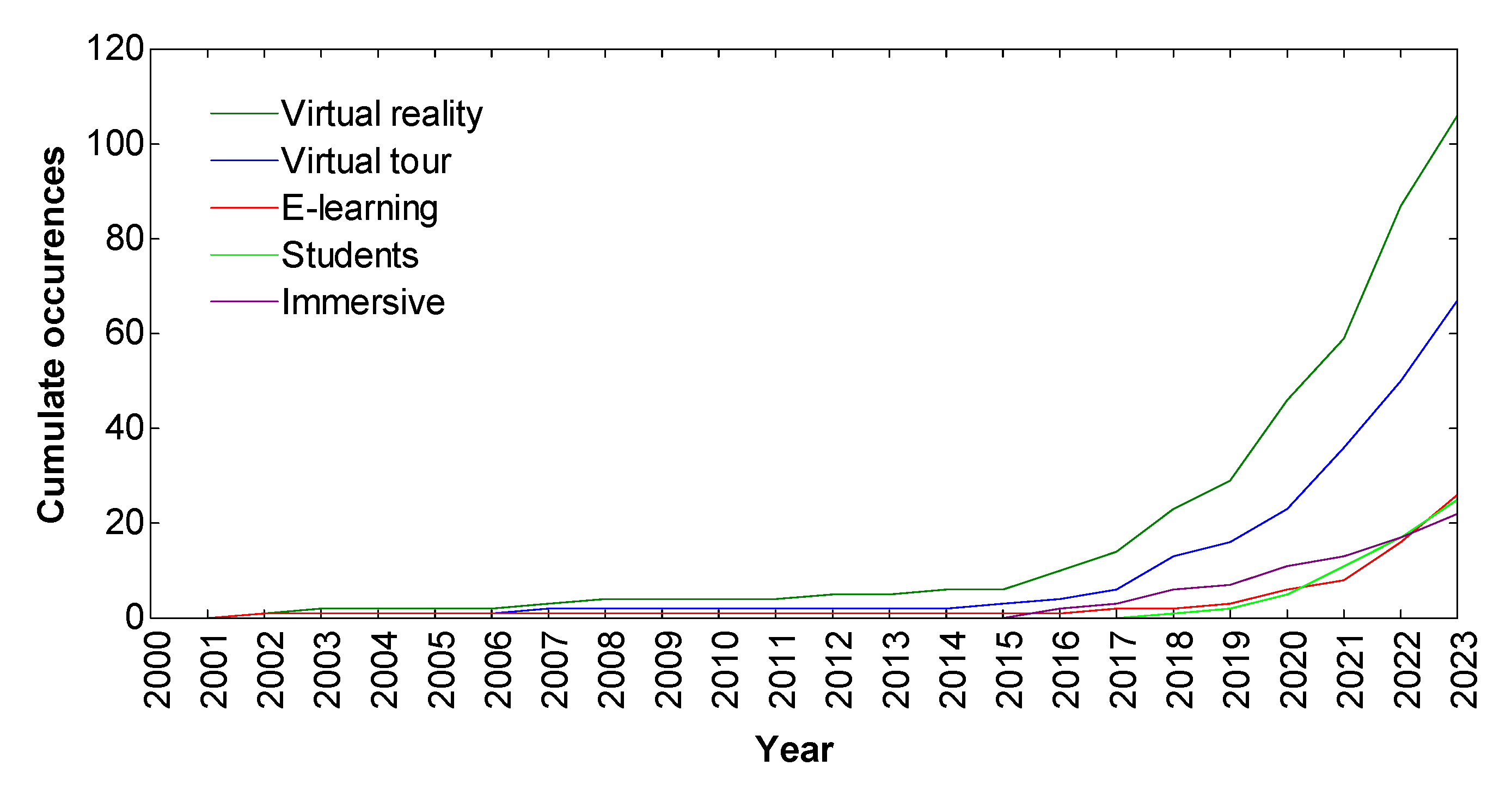

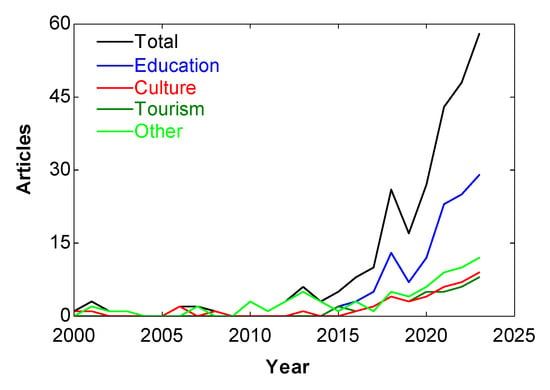

The annual scientific production along the analyzed period is shown in Figure 5. This figure shows the total number of documents published each year, as well as the number of documents according to the most relevant topics. Specifically, the topics were divided into education, culture, tourism, and others. As can be seen, Figure 5 shows an exponential growth in terms of publications related to 360 tours in general. A particular increment can be observed for the period 2016–2019, mainly due to the technological progress that facilitated the creation of 360 tours, as well as their visualization by users. Another new period of high increase in the number of publications can be observed from 2020 onwards. This increase was particularly significant in the educational sector. As in-person educational events were discontinued during the lockdowns caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual tours, such as 360 tours, emerged as a valuable tool to facilitate knowledge transfer.

Figure 5.

Number of documents published during the reporting period. Source: own source.

In terms of subject matter, the works related to education mostly include lessons prepared for distance learning, illustrating tours through laboratories, architecture, medicine, archaeology, or even master classes, where the aim is to provide a more immersive experience than that offered by traditional photos. Most of these works illustrate the implementation of 360 tours in teaching, analyzing the results obtained in terms of student learning. These studies underscore the positive social impact of 360 tours in education, including increased engagement, knowledge acquisition, and the promotion of creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship among students. By utilizing 360 tours and other innovative digital tools, educational institutions can develop dynamic and immersive learning experiences that improve student learning outcomes and contribute to a more engaging and effective educational setting. Some of these studies demonstrated that 360 tours can enhance learning, promote independent knowledge acquisition, and stimulate the students’ curiosity [39,68,69].

It is important to note that another emerging field relies on 360 tours of university campuses. The results show that the creation of 360 tours to show university campuses, and institutions in general, is a very promising measure to attract students. The social impact of 360 tours in showcasing university campuses extends to enhancing accessibility, promoting sustainability, and fostering community engagement. Regarding the evolution of the works on 360 tours over the years, a relevant increase is observed from around 2015, since the works before this date are scarce. The main reason for this is that the development of 360 tours was initially aimed at other sectors such as tourism and culture [70]. Once the effectiveness of 360 tours was demonstrated in sectors such as tourism and culture, this technique was transferred to the education sector.

With regard to the 360 tours applied to tourism, it can be observed that the evolution of the number of published works is more stable throughout the period analyzed (2000–2023), with the number of works related to tourism being greater in the early years and being surpassed in recent years by works related to education. The reason for this is that the 360 tours, although initially focused on aspects of tourism, are of little interest in scientific journals, and recent works are published in the journals of other fields.

When it comes to 360 tours applied to culture, the situation is similar to the case of tourism. At the beginning of the 21st century, there was great interest in applied 360 tours, especially tours through museums, libraries, and monuments, among other locations. However, over the years, this type of work began to be published in different types of journals other than scientific journals. Nevertheless, as shown in Figure 5, very interesting works continue to be published in the scientific literature, reflecting surveys, opinions, results, and conclusions of 360 Tour applications aimed at cultural aspects.

The section classified as “other” in Figure 5 mainly includes works related to technical aspects of 360 tours, such as tour creation techniques, cameras, studies on voice effects, motivation techniques, and how to capture attention, the effect of photo localization, advertising, digital twins, etc.

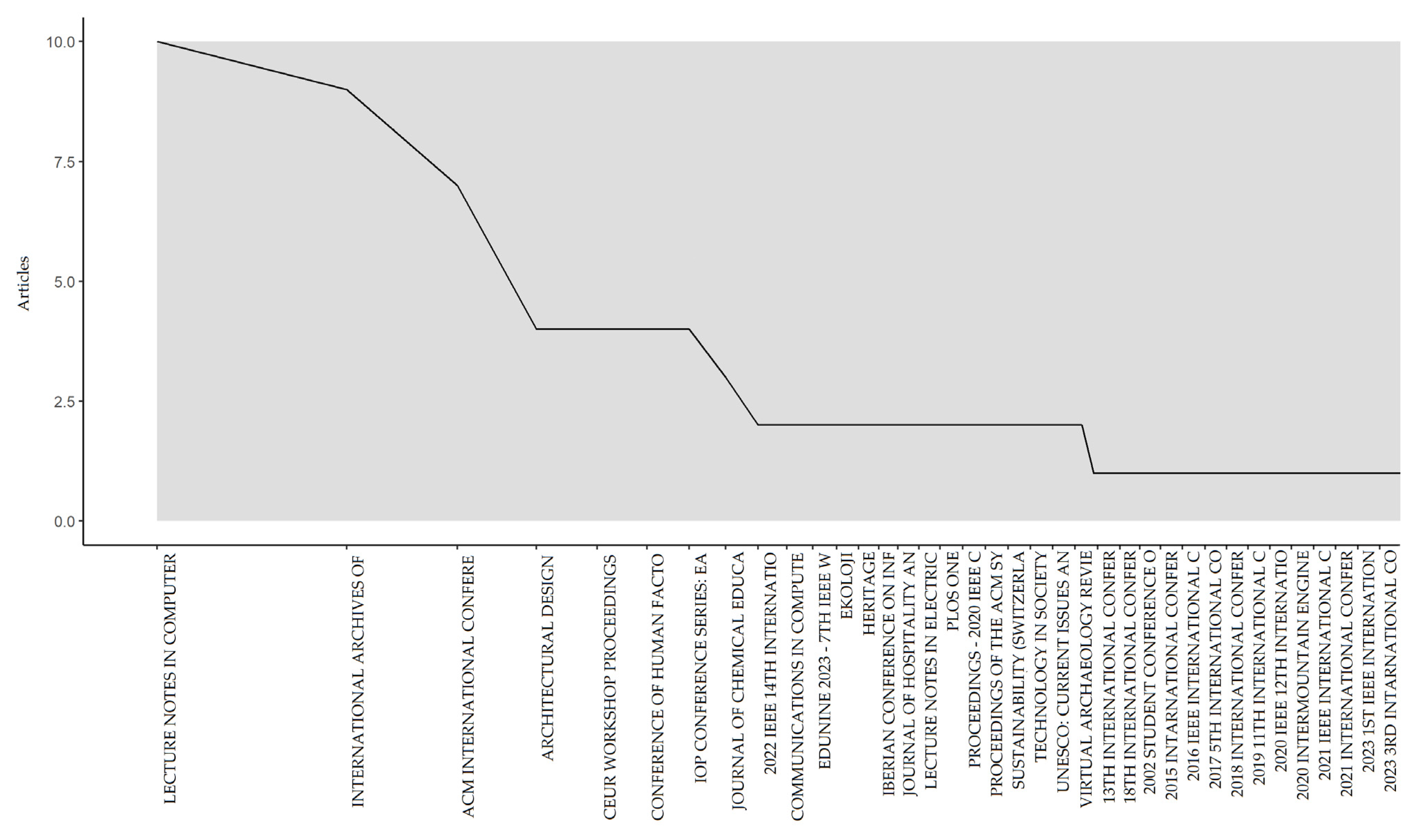

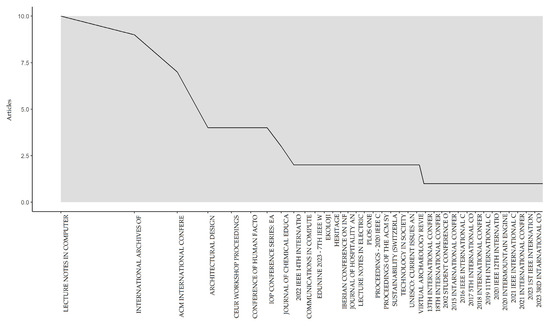

Identifying the key sources and their importance in the field of 360 tours is crucial for guiding interested authors to appropriate platforms for disseminating their work. A common method for identifying these key sources is to apply the model based on Bradford’s law [71]. Figure 6 illustrates the application of this model. This figure shows that the most prominent sources are “Lecture Notes in Computer Science” with ten documents, “International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences” with nine documents, and “ACM International Conference Proceeding Series” with seven documents. The other sources have a noticeably smaller number of documents.

Figure 6.

Core sources by Bradford’s law. Source: own source.

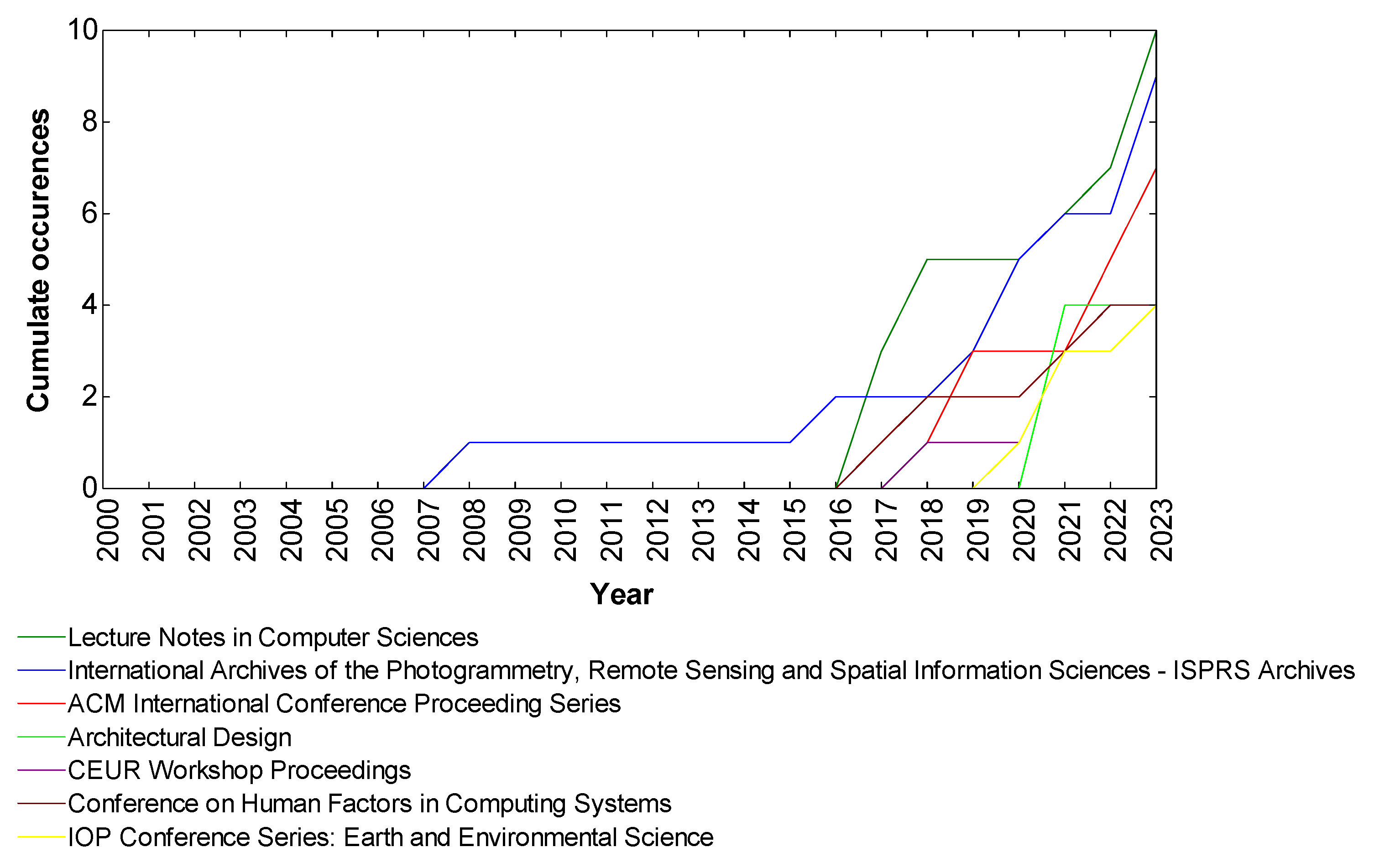

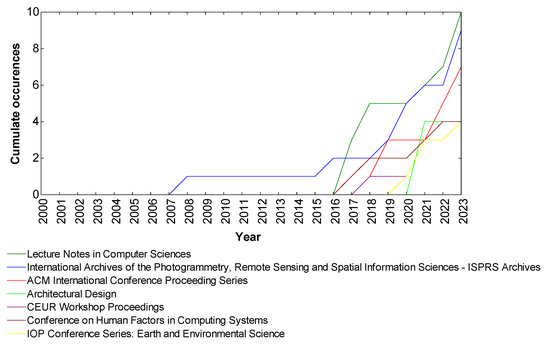

Figure 7 complements the information provided by Figure 6 by illustrating the trends in the cumulative frequency of documents on 360 tours published by the most relevant core sources over time. These sources include “Lecture Notes in Computer Science”, “International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences”, “ACM International Conference Proceeding Series”, “Architectural Design”, “CEUR Workshop Proceedings”, “Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems”, and “IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Sciences”. It is important to note that the documents published in conferences refer to different editions of the same conferences over the years. In general, Figure 7 shows an exponential trend in the mentioned sources in recent years, which is consistent with what was mentioned earlier, regarding 360 tours work in general experiencing rapid growth in recent years. The only exception is the case of the “International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences”.

Figure 7.

Sources’ production over time. Source: own source.

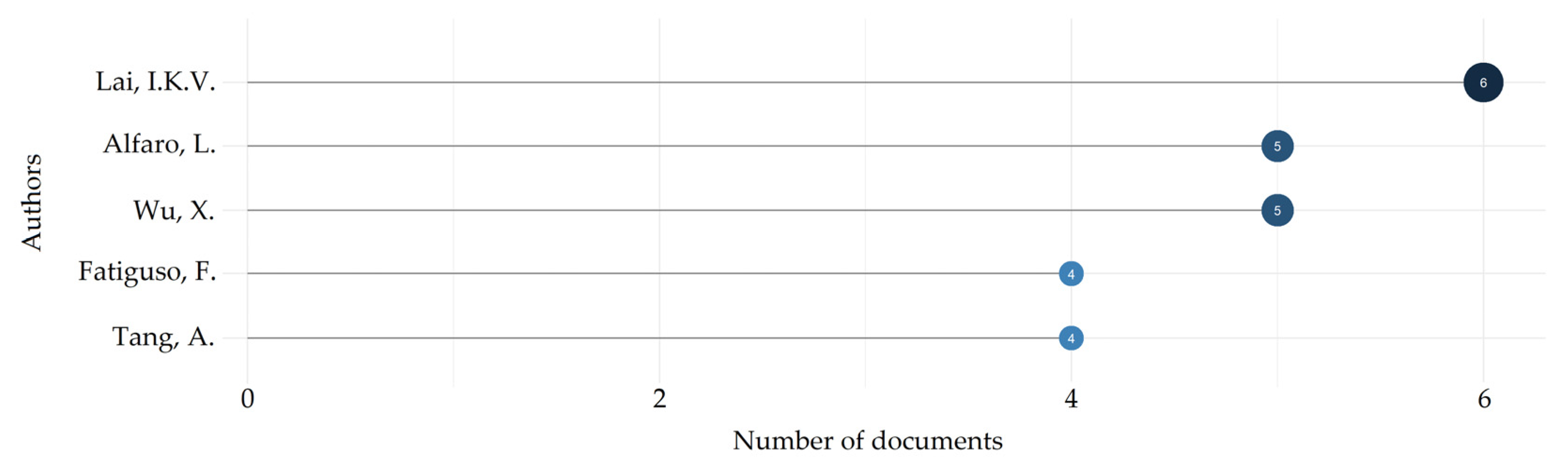

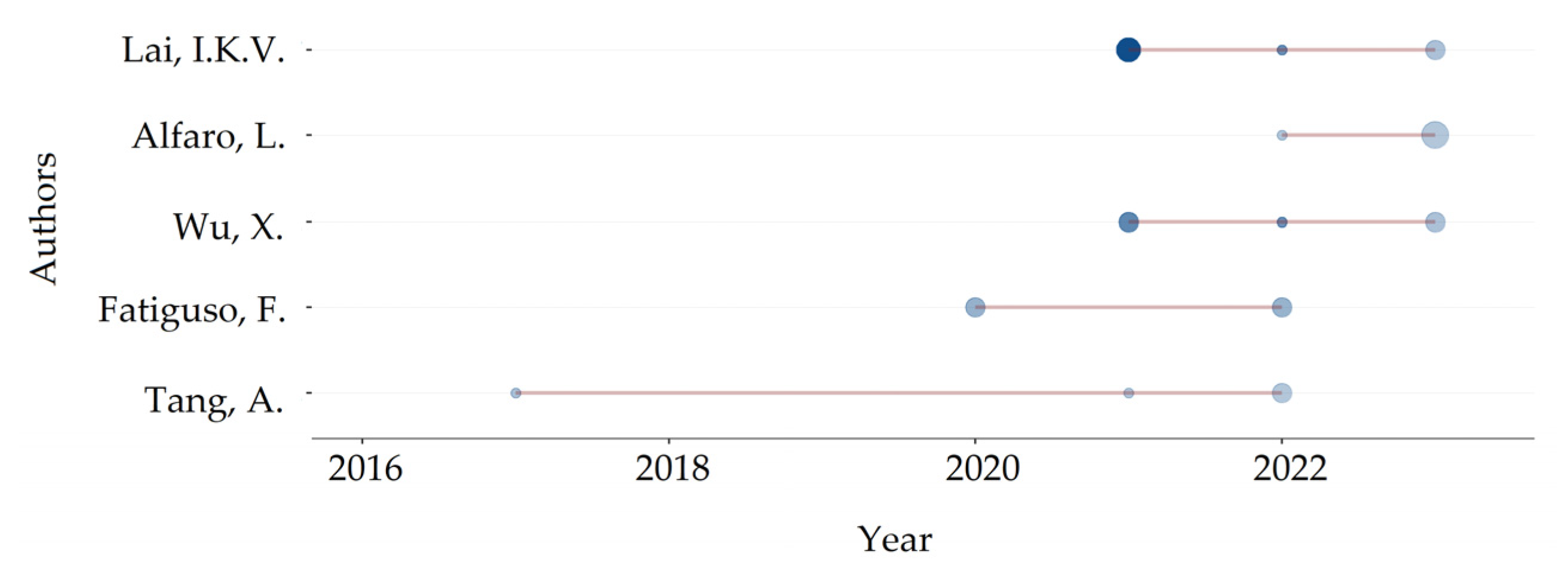

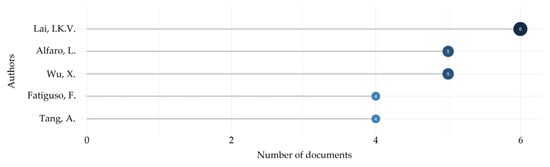

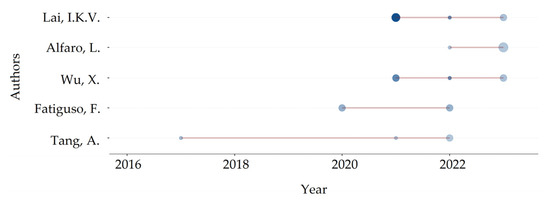

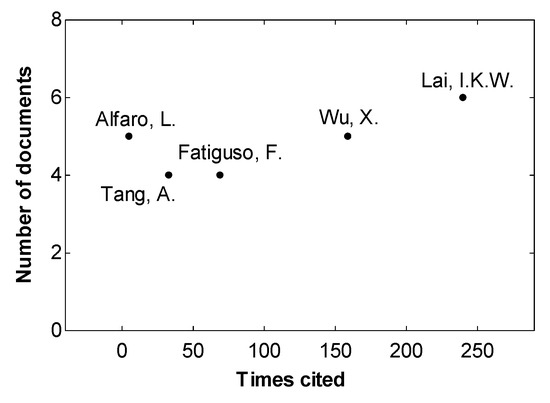

The identification of the authors who have carried out this research is also useful. Figure 8 shows the six most productive researchers in the field of 360 tours. The authors’ production over time is shown in Figure 9. In this figure, the size and color of the balls are proportional to the number of articles. As can be seen, these authors have recently published their work. This confirms the boom in the field of 360 tours in recent years. They are still active and new research talents are gradually becoming involved, which underlines the relevance and importance of 360 tours.

Figure 8.

Most relevant authors. Dark blue indicates a higher number of works. Source: own source [72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90].

Figure 9.

Authors’ production over time. Dark blue indicates a higher number of works. Source: own source [72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90].

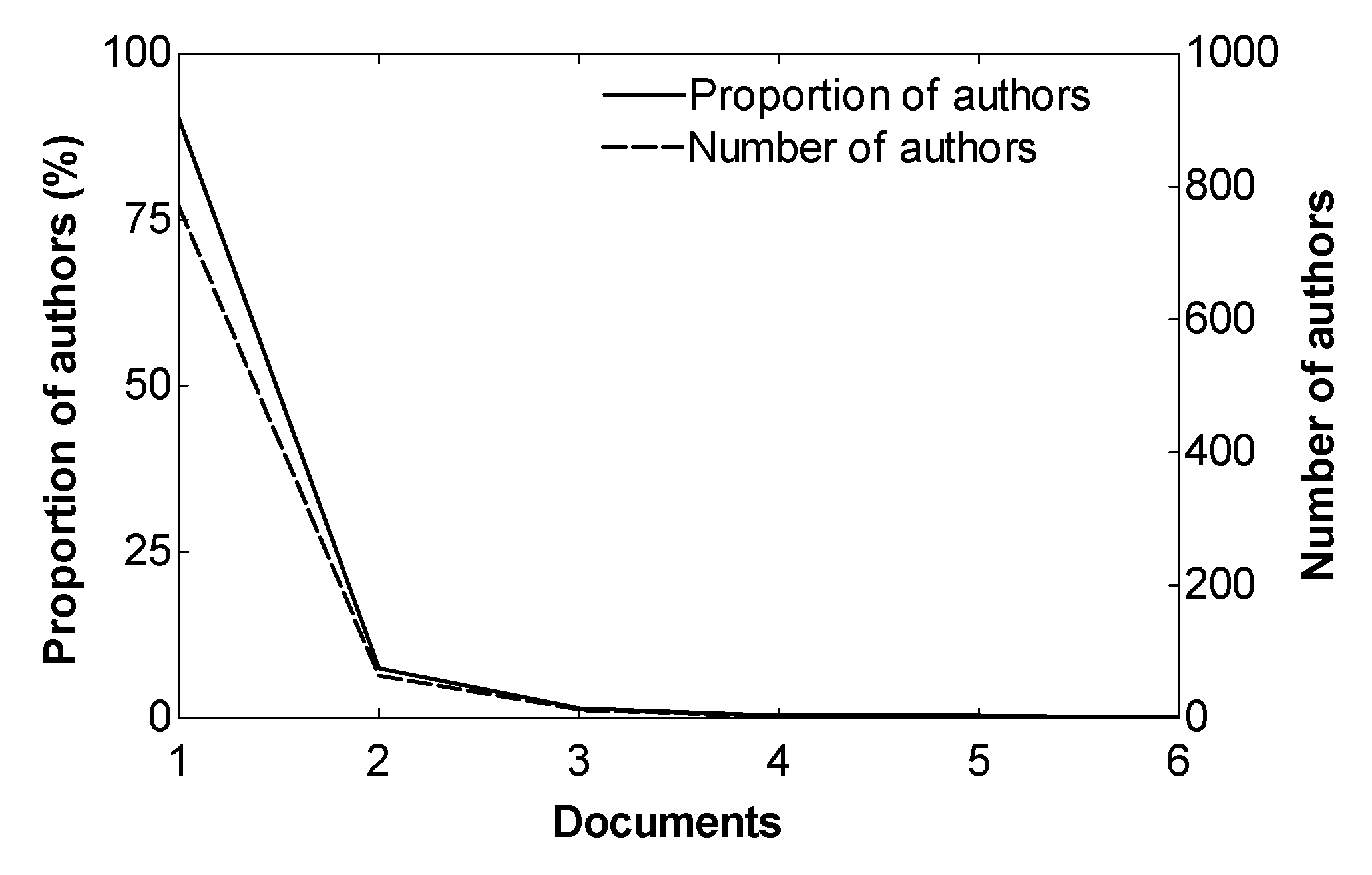

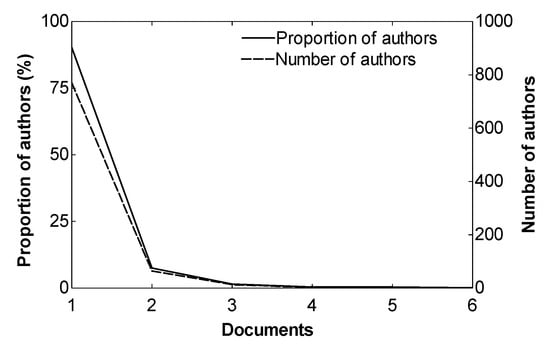

In general, the productivity of each author is very low. Figure 10 shows the productivity according to Lotka’s law. This figure shows that 770 authors published one document, 64 authors published two documents, 13 authors published three documents, 3 authors published four documents, 3 authors published five documents, and one author published six documents. This means that 90.2% of the authors published only one document.

Figure 10.

Author productivity through Lotka’s law. Source: own source.

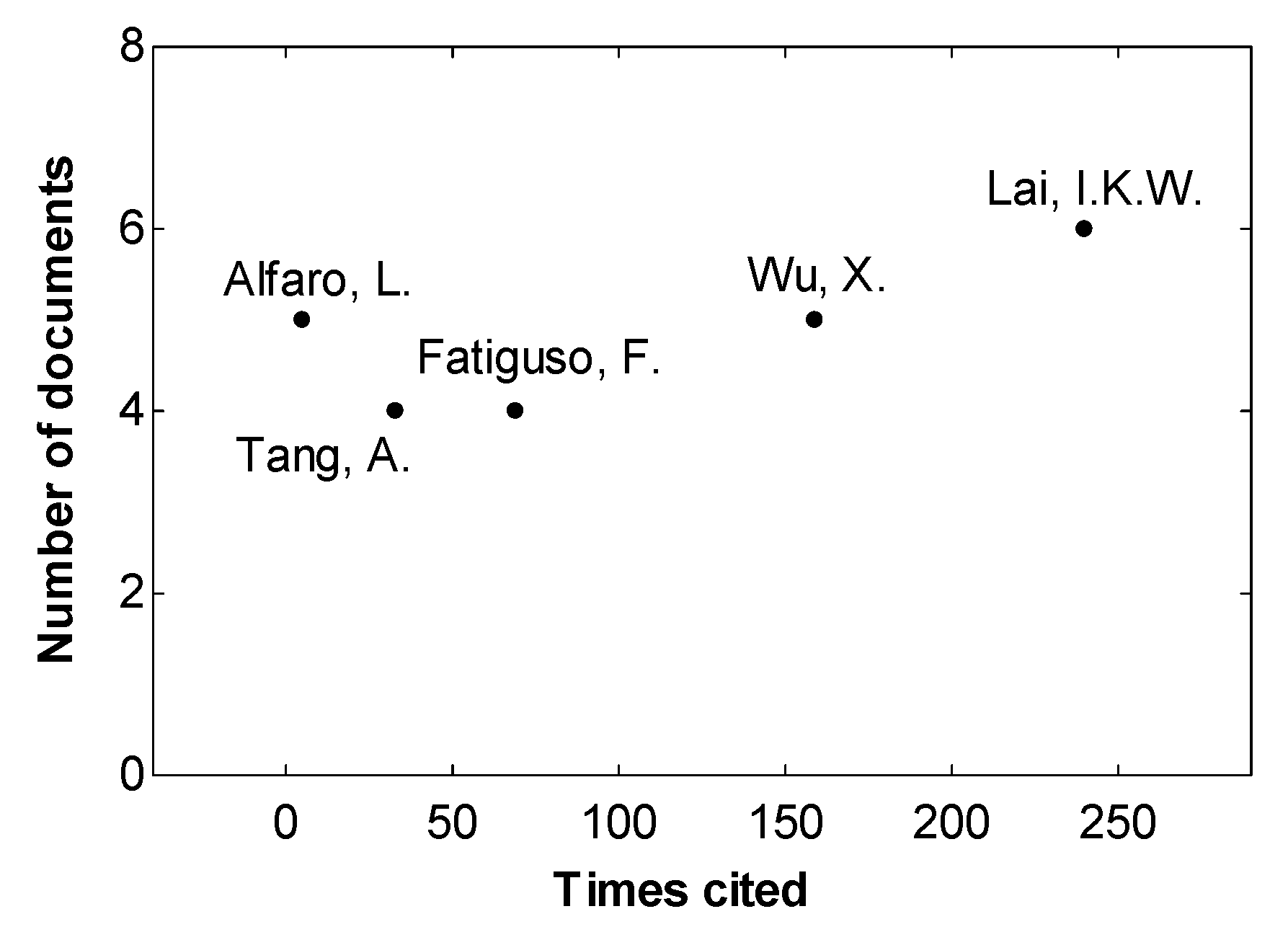

The works of the authors with more documents and their respective citations are summarized in Table 2. These are I.K.W. Lai (with six documents [72,73,74,75,76,77]), L. Alfaro (with five documents [78,79,80,81,82]), X. Xu (with five documents [72,73,74,75,77]); F. Fatiguso (with four documents [83,84,85,86]), and A. Tang (with four documents [87,88,89,90]).

Table 2.

Most productive authors.

A common way to analyze the balance between published documents and citations is to create a scatterplot, as shown in Figure 11, where each point represents a researcher defined by their number of documents and corresponding citations. Figure 11 shows that the authors with the best balance between production and impact are I.K.W. Lai and X. Wu, both from the City University of Macau, China. The 360 Tour works published by these authors are mainly focused on tourism.

Figure 11.

Scatterplot with the most prolific researchers on 360 tours. Source: own source [72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90].

Regarding citations, Table 3 shows the 35 most cited authors. As can be seen, the most cited authors are V. Bogicevic, S.Q. Liu, N.A. Rudd, S. Seo, and J.A. Kandampully, who maintain 321 citations. These citations are provided from two studies: Bogicevic et al. [91] with 269 citations and Bogicevic et al. [92] with 52. Another important group is the one constituted by I.K.W. Lai, X. Wu, Z.B. Fan, Q.M. Mo, and T. Yang, who have their citations mainly from the works [75,77,92,93]. Other highly cited authors include M.D. Hanus and A. Wagler, who have obtained 86 citations from a single manuscript [94], M. Pedelty, who has obtained 79 citations from [95], L. Argyriou, V. Bouki, and D. Economou, who have obtained 74 citations from [93], and F. Fatiguso, who has accumulated 69 citations from several works. C. Chen and M.Z. Yao have obtained their citations mainly from the works [96,97], while D.J. Chiam, K. Dean, C.C. Feng, O.B.P. Mah, J.S.Y. Tan, Y.X. Tan, G.Q.Y. Tay, Y.X. Wang, and Y. Yan have obtained 58 citations from [98]. E. Baek, H.J. Choo, X. Wei, and S.Y. Yoon have obtained 48 citations from [11]. J.B. Barhorst and G. McLean obtained 45 citations from [99]. M. De Fino has obtained 39 citations from the works [84,85]. Most of the aforementioned works deal with tourism and culture. As the 360 Tour works about education have been published mainly in recent years, they have not yet had enough time to accumulate many citations.

Table 3.

Most cited authors.

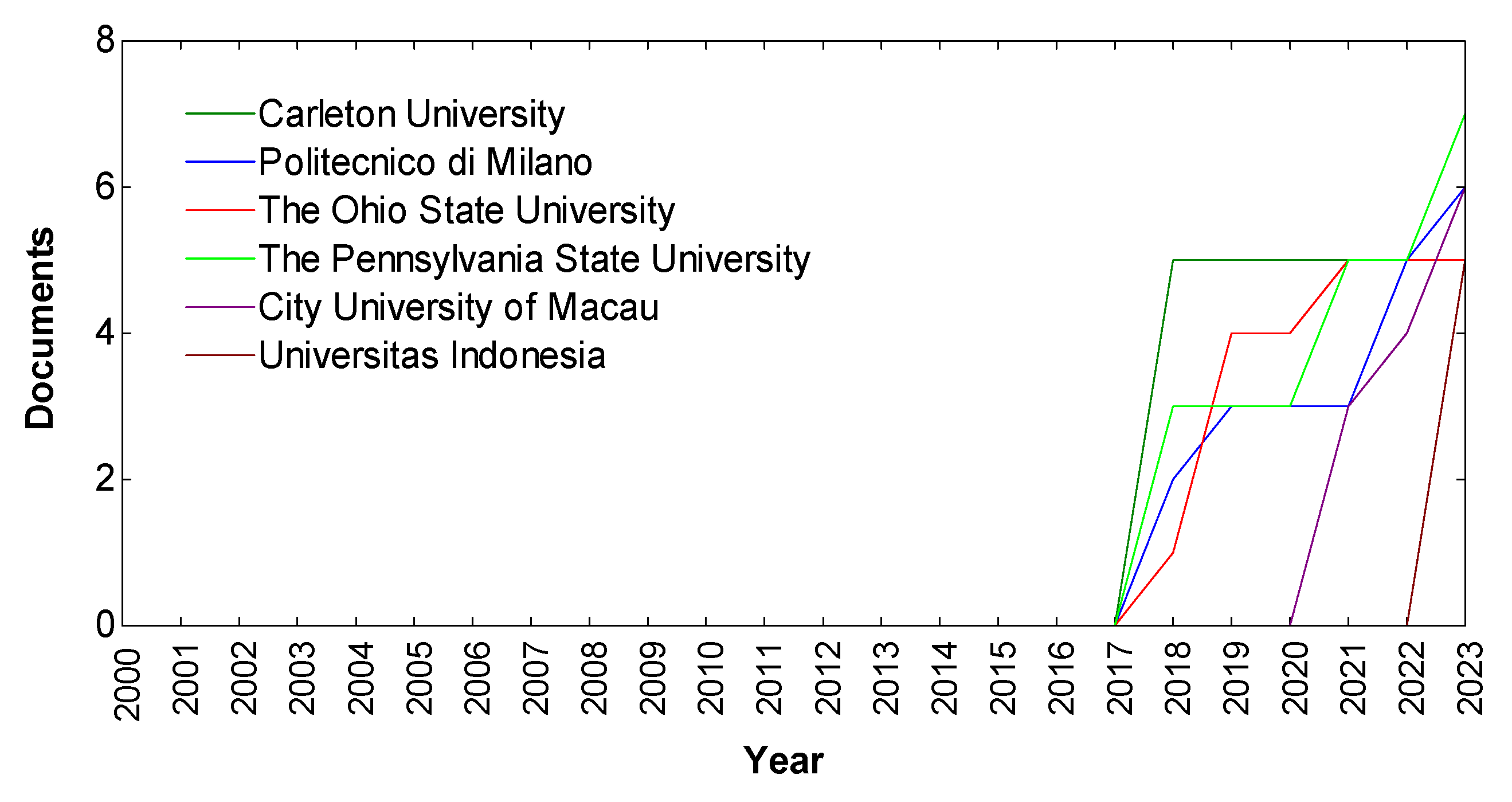

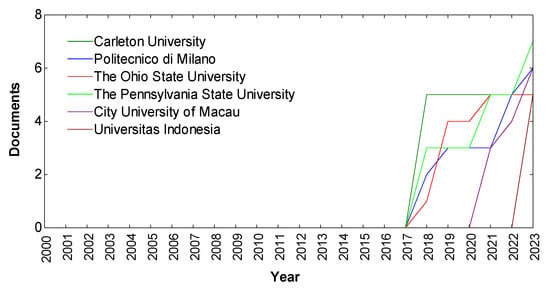

After describing the overall production scale, visibility, and impact of 360 tours research, another interesting aspect is to identify the key institutions and countries where this research is conducted. Table 4 shows the ten institutions with the highest production of 360 tours. In terms of production over time, Figure 12 shows the production over the years. As can be seen, the production of these institutions is too incipient.

Table 4.

Institutions with the highest amount of publications.

Figure 12.

Affiliations’ production over time. Source: own source.

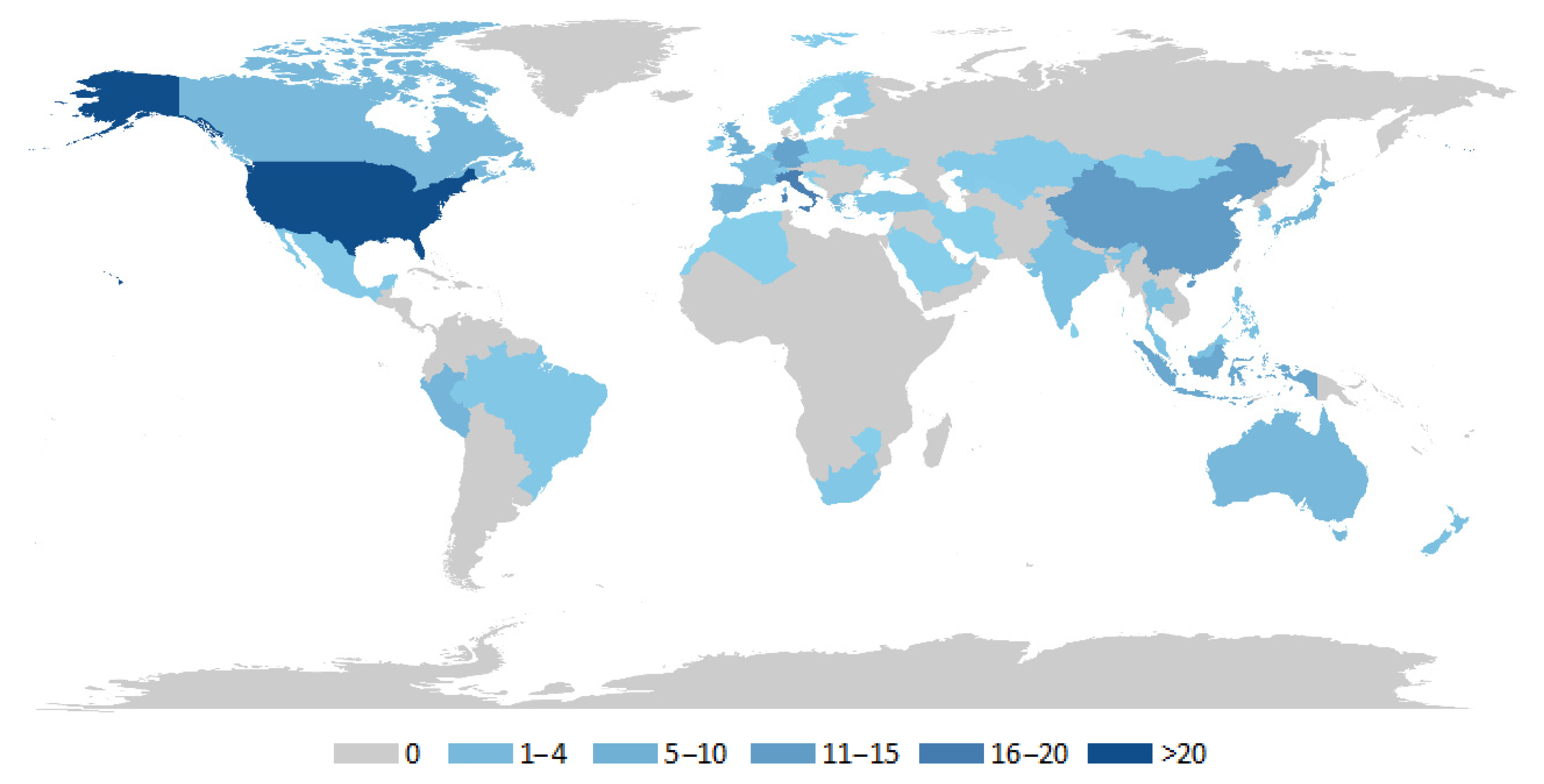

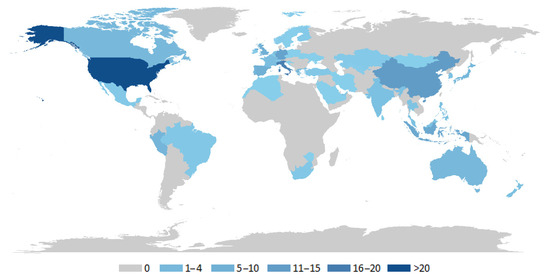

Table 5 provides the 11 countries with higher production in 360 tours, and Figure 13 graphically illustrates the production worldwide. The USA, with 21 works, leads in research on 360 tours. This indicates a strong interest and investment in immersive technologies, likely driven by advanced technological infrastructure and funding in higher education and research institutions. Italy follows closely with 17 works, suggesting significant interest in utilizing 360 tours due to its rich cultural heritage and tourism sector, which can benefit from such technologies. Ranking third with 11 works, China demonstrates growing engagement with 360 tours, reflecting its rapid technological advancements and application of new technologies. With eight works, Spain shows a substantial focus on 360 tours, which could be attributed to its strong tourism industry and emphasis on cultural heritage. Germany (seven works), Indonesia (five works), Japan (five works), and the UK (five works) are notable contributors. These countries have diverse applications of 360 tours, spanning education, tourism, and cultural sectors, indicating a balanced interest in leveraging these technologies across various fields. Australia (four works), Republic of Korea (four works), and New Zealand (four works) represent emerging research communities in the field of 360 tours. Their contributions, though fewer in number, indicate growing recognition of the potential of 360 tours.

Table 5.

Countries with the highest amount of publications.

Figure 13.

Countries’ scientific production. Source: own source.

Table 6 shows the most cited countries. The USA leads both in the number of publications and total citations, indicating a strong influence and significant research output in the field of 360 tours. The high citation count reflects the impact and recognition of the research conducted in the USA. Italy ranks second in terms of publications and also has a high citation count. This suggests that Italy is both prolific and influential in 360 tours research, contributing substantially to the academic discourse. China has a notable number of publications and a significant citation count, indicating active research and substantial contributions to the field. Spain has a moderate number of publications, but a relatively lower citation count compared to other leading countries. This might suggest emerging research strength with growing influence. Despite having fewer publications, the UK has a high citation count, indicating that its research is highly impactful and recognized within the academic community. Korea’s relatively low number of publications but high citation count suggests that the research conducted is of high quality and significance. Australia shows a balance between the number of publications and citations, indicating a steady contribution to the field. Similar to Australia, New Zealand has a moderate number of publications and citations, suggesting consistent research output and impact. Singapore and Turkey are highly cited despite not being in the top list for the number of publications, indicating that their contributions are highly valued and influential.

Table 6.

Most cited countries.

4. Discussion

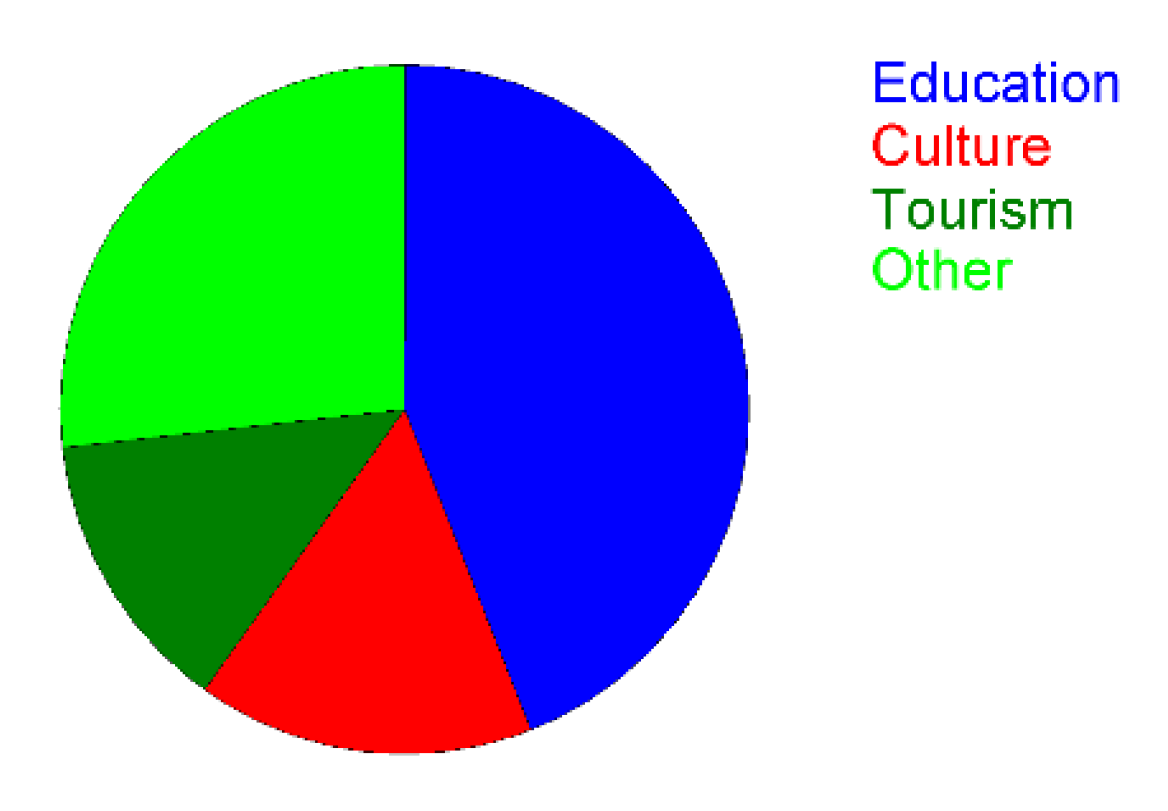

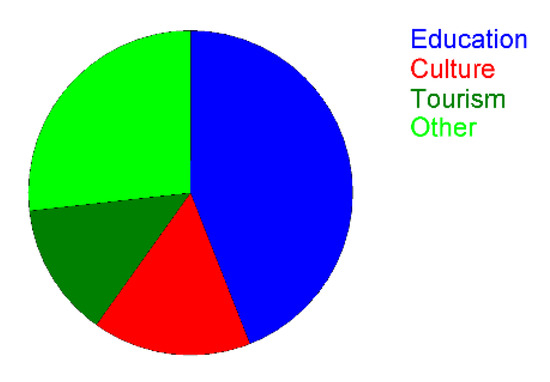

Many issues have been addressed over the years. As indicated above, the present work classifies the topics as indicated in Figure 14 into four groups: education, culture, tourism, and other. In the group categorized as “others”, different types of works have been included, such as the technical aspects of 360 tours, technological innovations for their development, hardware, software, and motivational strategies, among others. The proportion of publications shown in Figure 14 is 44.2% for education, 15.6% for culture, 13.4% for tourism, and 26.8% for other.

Figure 14.

Main topics about 360 tours. Source: own source.

The research indicates that 360 virtual tours have notably influenced various social sectors, especially tourism, culture, and education, by reshaping how individuals interact with and perceive these areas [2,5,100,101]. In the realm of tourism, 360 tours have transformed promotional strategies, providing potential visitors with immersive previews of destinations and accommodations. This innovation has been associated with increased tourist satisfaction and enhanced the overall value of the travel experience [4,8,102,103,104]. From a sociological perspective, these tours facilitate a deeper connection to cultural heritage sites and museums by offering accurate, virtual representations that engage users in a more meaningful exploration of cultural artifacts [5]. In education, the integration of 360 tours has introduced new dynamics into learning environments, enabling virtual field trips that complement traditional methods and foster higher levels of student engagement [14]. This highlights how technological advancements can influence social behaviors and educational practices, making 360 tours a significant tool in understanding contemporary interactions with cultural and educational content.

The focus on education in the context of 360 tours is often emphasized due to significant advancements and research surrounding immersive learning experiences; however, it is essential to recognize that 360 tours have also made substantial impacts in other sectors, particularly tourism and cultural heritage. The limited discussion on these areas may stem from several factors: much of the recent academic literature has concentrated on the educational applications of 360 tours, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, which accelerated the adoption of digital learning tools, potentially overshadowing the exploration of trends in tourism and cultural heritage where the integration of 360 tours is also evolving. Additionally, the rapid development of technologies such as virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) has drawn attention away from the traditional applications of 360 tours in tourism and cultural heritage, as discussions may prioritize their innovative uses rather than established practices. Furthermore, there may be a perception that 360 tours are primarily educational tools, leading to a narrower exploration of their applications and limiting the recognition of their potential in enhancing visitor experiences in tourism and cultural heritage contexts.

It is worth noting that while both cultural and tourism applications of 360 tours use similar technology to create immersive experiences, their purposes and impacts are significantly different, which is why they have been divided into different groups in the present work. Cultural applications focus on the accessibility of cultural heritage. These tours are often developed by museums, galleries, historical sites, and cultural institutions to provide virtual access to their collections and exhibits. The main goals include accessibility and inclusion (providing access to cultural heritage for individuals who may not have the means or ability to visit in person, thereby democratizing access to cultural knowledge), preservation (preserving cultural sites and artifacts for future generations), and enhanced engagement (engaging users more deeply, fostering a greater appreciation and understanding of cultural heritage). On the other hand, 360 tours in the tourism sector are primarily designed for marketing and promotional purposes. Tourism applications aim to market destinations, enhance visitor experiences, and generate economic benefits.

As mentioned above, there has been a clear trend in recent years to use 360 tours for education. 360 tours have received considerable attention in the field of education as a promising pedagogical tool. Hamilton et al. [42] highlighted the importance of 360 tours in education, focusing on quantitative learning outcomes and experimental design. Several studies have shown that 360 tours can enhance the learning experience by providing a sense of presence in virtual environments, leading to improved learning outcomes [105]. The virtual 360 tours, and virtual reality in general, have been found to be superior to traditional educational methods, providing powerful interventions that result in immediate and lasting educational benefits [106]. The use of 360 tours in education has been shown to have significant advantages, with the technology supporting personal, social, and environmental presence, thereby enhancing the learning experience [107]. In addition, 360 tours allow for the embodiment of design principles that include gestures and hand controls, which are essential for optimizing pedagogy within the classroom. By creating immersive and interactive virtual environments, 360 tours enable learners to engage with content in a more intuitive and experiential way, leading to a deeper understanding of complex concepts [108].

In addition, 360 tours have been used in various educational settings to complement traditional learning methods. For example, virtual lab tours have been introduced to familiarize students with research lab facilities and equipment, thereby enhancing their practical skills and knowledge [39]. Additionally, these tours have been integrated into academic forestry education to provide students with immersive experiences that complement their learning of forest management practices [109]. Furthermore, the use of 360 tours in education extends beyond campus promotion to cover a wide range of educational applications. These tours have been used to facilitate historical learning, explore cultural heritage, and enhance geography–environment education [68,110]. By providing students with interactive and engaging experiences, 360 tours have the potential to improve learning outcomes, encourage independent knowledge acquisition, and stimulate students curiosity [59].

Enriching learning environments is not the only application of 360 tours in the field of education since 360 tours have also emerged as a valuable tool for promoting educational institutions. These tours allow students to engage in virtual experiences that go beyond physical constraints, offering insights into campus life and educational facilities [111]. Through the utilization of this technology, educational institutions can develop virtual campus tours that give prospective students, families, and international visitors a sense of connection and familiarity with the campus environment [112].

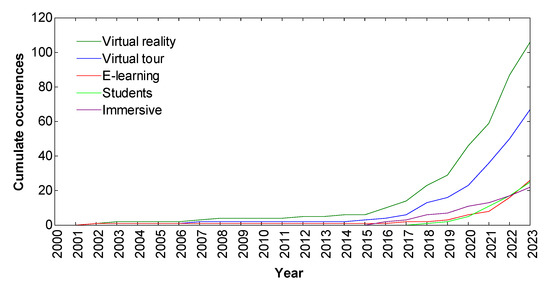

The use of 360 tours in education has been shown to increase student engagement, motivation, and learning outcomes by providing interactive and multi-sensory learning experiences. By leveraging the immersive quality of 360 tours, educators can create environments that promote experiential learning, critical thinking, and knowledge retention. In addition, 360 tours have been praised for their ability to facilitate cultural immersion, providing students with a unique opportunity to explore different environments and perspectives. In addition, the development of web-based virtual tour experiences has enabled prospective students to virtually explore university campuses, facilitating informed decision-making regarding their educational journey [60]. In addition, the integration of 360 tours in education has the potential to revolutionize teaching practices by providing innovative and effective ways for students to learn, explore, and interact with educational content. As technology advances, the integration into education is likely to become more commonplace, offering students an innovative and effective way to learn, explore, and interact with the world around them. Table 7 shows the most common keywords over the study period and Figure 15 the frequency over time. As can be seen, e-learning and students appear many times.

Table 7.

Most frequent words.

Figure 15.

Words’ frequency over time. Source: own source.

Regarding the cultural sector, the most analyzed works focus on museums, offering immersive and interactive experiences through 360 tours. There are also works on other cultural sectors, such as theaters, libraries, archaeology, monuments, and more. 360 tours are essential for cultural education, preservation, and promotion by providing immersive and interactive experiences that increase visitor engagement and knowledge acquisition. By embracing 360 tours, and innovative digital tools in general, cultural institutions can create dynamic and informative virtual tours that contribute to the preservation and dissemination of cultural heritage for present and future generations. Museum visitors, for instance, engage with 360 tours to access cultural heritage and art collections that they might not be able to visit in person. These virtual experiences not only provide broader access to cultural artifacts and exhibitions but aim to deepen user engagement by offering contextual information and interactive elements that enrich the viewing experience. Many museums leverage these tours to create a sense of presence and connection, allowing users to appreciate artworks and historical artifacts from various perspectives while learning about their significance and historical context. 360 tours can facilitate cultural immersion by allowing users to explore exhibits at their own pace, making the pursuit of cultural knowledge more personalized and accessible.

In the tourism industry, 360 tours offer a glimpse of destinations before the actual visit. Examples include virtual tours of resorts, hotels, national parks, and city landmarks designed to attract tourists and provide detailed previews of what they can expect during their visit. While most of the literature on virtual tours in tourism is not scientific, it plays a crucial role in marketing destinations and engaging travelers. The use of virtual tours has gained momentum, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, as a safe alternative to physical travel. These tours have the potential to enhance the tourism experience, effectively promote destinations, and contribute to the recovery of the tourism sector after the pandemic. Researchers have highlighted the importance of virtual tours in attracting tourists, enhancing destination visibility, and providing interactive experiences that can influence travelers’ perceptions and decisions. Tourists interact with 360 tours primarily for planning and enhancing their travel experiences. These tours offer immersive previews of potential destinations, accommodations, and experiences, allowing users to navigate through locations before booking. This pre-visit exploration helps tourists make informed decisions, enhancing their anticipation and satisfaction when they arrive at the physical site. The involvement in 360 tours provides a sense of familiarity and comfort, especially for international travelers who might be unfamiliar with a new culture or locale. Furthermore, the ability to explore areas that may be less accessible or traditionally hard to reach adds an element of inclusivity and democratizes travel experiences.

While contemporary discussions around 360 tours often focus on cutting-edge technologies, like VR and AR, it is crucial to acknowledge the historical significance of 360-degree battle panoramas in tourism, as these early immersive experiences laid the foundation for modern practices and continue to offer valuable insights into engaging with history and culture. The practice of creating 360-degree battle panoramas has a rich history, with notable examples dating back to the early 20th century, such as the panoramic depiction of the Battle of Waterloo established in 1911, designed to transport viewers to significant historical events and engage with history uniquely. These panoramas served as artistic representations and educational tools, providing insights into historical events and shaping public understanding, contributing to the collective memory of societies. The establishment of 360-degree battle panoramas as tourist attractions highlights their importance in the tourism sector, drawing visitors eager to learn about history and experience it more engagingly. While the original battle panoramas relied on traditional artistic techniques, the advent of new technologies, such as VR and AR, has transformed how these experiences are created and consumed, incorporating interactive elements and enriching the visitor experience. Recognizing the value of historical practices, like battle panoramas, in the context of modern technological advancements is essential, as future research should explore how these traditional forms of immersive storytelling can inform the development of contemporary 360 tours. The legacy of 360-degree battle panoramas underscores the importance of preserving cultural heritage. As new technologies emerge, there is an opportunity to digitize and recreate historical panoramas, making them accessible to a broader audience and ensuring that the stories and lessons of the past continue to resonate with future generations.

5. Conclusions

This study delves into the world of 360 tours, exploring their growth and importance in various fields. By analyzing the literature and key contributors in the field, the study highlights the transformative potential of 360 tours in enhancing immersive experiences and their growing relevance in a post-pandemic world. The software for creating 360 tours has evolved to meet the demands of various sectors, providing immersive and interactive experiences that enhance user engagement and learning. The ongoing advancements in technology and the increasing accessibility of software tools will likely continue to shape the future of virtual tours, making them an integral part of tourism, education, and beyond.

The implications of the findings regarding 360 tours highlight their transformative potential across various sectors. In education, they enhance learning experiences by fostering greater engagement and retention, suggesting an urgent need for educators to leverage these immersive tools, particularly given the shift towards digital learning trends. In the realm of cultural preservation, 360 tours democratize access to heritage sites and artifacts, thereby promoting public engagement and appreciation for cultural practices. For tourism, these tours improve customer experiences by creating deeper connections with potential visitors, advocating for their inclusion in marketing strategies.

A notable finding of the present work was the significant increase in the relevant literature since 2017, indicating a growing body of work in this area. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a notable increase in publications, particularly in the area of education. While initially focused on tourism, the application of 360 tours has expanded to various sectors, including culture and education.

This study identifies key contributors and institutions in the field, noting that the United States leads in both publications and citations, indicating a strong influence in 360 Tour research. Other countries, such as Italy and China, also show significant contributions. Overall, the growing adoption of 360 tours across multiple sectors underscores their versatility and social impact. Future research should continue to explore and address the challenges and considerations associated with integrating 360 tour sin different contexts in order to fully realize their benefits. As technology continues to evolve, the potential for 360 tours will undoubtedly expand, offering even more innovative and engaging ways to connect with and understand the world. This analysis suggests that further research is needed to explore the sociological implications of 360 tours, particularly how they intersect with social behaviors and cultural practices. This could provide deeper insights into the ongoing evolution of digital interactions in different social contexts.

For the limitations of the present work, it is worth noting that only the Scopus database was used, there are many other scientific databases, such as Web of Sciences. This study is limited by a selection of the literature reviewed that primarily focuses on published academic documents. This could exclude valuable insights, such as industry reports or case studies that are not formally published. In addition, the study’s reliance on citation counts as the primary metric for assessing the quality and impact of selected papers highlights a significant limitation in understanding the true influence and relevance of research in the field of 360 tours. While useful for indicating scholarly attention on certain works, citation counts do not necessarily reflect the quality of the research or its concrete impact on practice and user experience. For example, highly cited works may have gained attention due to their novelty or the popularity of their findings rather than their methodological rigor or applicability. Another limitation is that the present analysis is based on the literature available up to 2023, which does not capture the most recent developments or emerging trends in the field of 360 tours, especially given the rapid advancements in technology. In the same way, the present work has mentioned software and apps that are currently available to create both images and 360 tours. This field is subject to such rapid change that it is likely that new relevant software and apps will soon be available and some of those listed here will cease.

6. Future Directions

While the immediate benefits of 360 tours, such as enhanced engagement and immersive experiences, are well-documented, it is essential to explore their potential long-term impacts, particularly technological evolution. Technology is continually evolving, and 360 tours are likely to undergo significant transformations as new advancements emerge. Future research should examine how 360 tours can integrate with other immersive technologies, such as augmented reality and virtual reality, to create even more engaging and interactive experiences. Additionally, the incorporation of artificial intelligence could personalize 360 tours, tailoring content to individual user preferences and learning styles. As technology advances, it will be essential to assess how these innovations can enhance the effectiveness of 360 tours and expand their applications in various fields.

Research should also delve into the sociocultural implications of 360 tours, exploring how they intersect with social behaviors, cultural practices, and community engagement. Future studies should focus on how 360 tours can be designed to be more accessible and inclusive for diverse populations, including individuals with disabilities, to ensure equitable access to immersive experiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R. and M.I.L.; methodology, L.C.-S.; software, J.R.; formal analysis, J.R., M.I.L. and L.C.-S.; investigation, J.R., M.I.L. and L.C.-S.; resources, L.C.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.I.L.; writing—review and editing, L.C.-S.; visualization, L.C.-S.; supervision, L.C.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study contributes to the international project 3E-Partnership (proposal number 101128576) funded with support from the European Commission under the Action ERASMUS-LS and the Topic ERASMUS-EDU-2023-CBHE-STRAND-2.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rahaman, H.; Champion, E.; McMeekin, D. Outside Inn: Exploring the Heritage of a Historic Hotel through 360-Panoramas. Heritage 2023, 6, 4380–4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaidou, I.; Zupančič, R.; Fiedler, A.; Andresen, K.; Hoxha, A.; Ntaltagianni, C.; Aivalioti, M.; Kasapovic, M.; Milioni, D. Virtual Tours as Emerging Technologies to Engage Children and Youth with their Country’s Historical Conflicts. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2022, 17, 164–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadiev, R.; Yi, S.; Dang, C.; Sintawati, W. Facilitating Students’ Creativity, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship in a Telecollaborative Project. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 887620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stappung, Y.; Aliaga, C.; Cartes, J.; Jego, L.; Reyes-Suárez, J.A.; Barriga, N.A.; Besoain, F. Developing 360° Virtual Tours for Promoting Tourism in Natural Parks in Chile. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petousi, D.; Katifori, A.; Boile, M.; Kougioumtzian, L.; Lougiakis, C.; Roussou, M.; Ioannidis, Y. Revealing Unknown Aspects: Sparking Curiosity and Engagement with a Tourist Destination through a 360-Degree Virtual Tour. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2023, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, L.; Aris, A.B.; Yan, X. Digital display and storytelling: Creating an immersive experience of Lingnan costume cultural heritage tourism project. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1366, 012047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-L.; Ng, W.-K.; Jiang, J.L.; Shih, Y.S. Cultural Heritage Service Design and Experience Innovation: A Case Study of Taiwan. Cult. Arts Res. Dev. 2024, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasco, A. Beyond virtual cultural tourism: History-living experiences with cinematic virtual reality. Tour. Herit. J. 2020, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.; Ammar, S.; Soliman, K. Virtual Reality Technology as a Tool for Promoting Luxor as a Cultural Tourism Destination. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 5, 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VijayKumar, S.; Thyagaraj, S.P. Congestion and throughput optimization protocol for providing better quality of service and experience. IAES Int. J. Artif. Intell. 2024, 13, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, E.; Choo, H.J.; Wei, X.; Yoon, S.-Y. Understanding the virtual tours of retail stores: How can store brand experience promote visit intentions? Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2020, 48, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdian, S.; Hermawan, A.; Edy, E. Designing a Chatbot Based on Full-Text Search and 3D Modelling as a Promotional Media. JUITA J. Inform. 2023, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamas Galdo, M.I.; Orosa García, J.A.; Cartelle Barros, J.J. 360 Virtual Tours in Education. Towards New Dimensions of Teaching; LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2023; ISBN 9786206781240. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, L.; Sung, B. User experiences with 360 brand videos: Device experiences, presence, and creativity driving brand engagement. J. Brand Manag. 2024, 31, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukerch, I.; Takarli, B.; Saidi, K.; Karich, M.; Meguenni, M. Development of panoramic virtual tours system based on low cost devices. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2021, 43, 869–874. [Google Scholar]

- Iorns, T.; Rhee, T. Real-Time Image Based Lighting for 360-Degree Panoramic Video. In Image and Video Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 139–151. [Google Scholar]

- Midoglu, C.; Alay, Ö.; Griwodz, C. Evaluation Framework for Real-Time Adaptive 360-Degree Video Streaming over 5G Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 on Wireless of the Students, by the Students, and for the Students Workshop, Los Cabos, Mexico, 21 October 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Vishwas Venkat; Raja Reddy Review and analysis of the properties of 360-degree surround view cameras in autonomous vehicles. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2023, 8, 656–661. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Kwon, O.-J.; Choi, S. Generation of a Panorama Compatible with the JPEG 360 International Standard Using a Single PTZ Camera. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snelson, C.; Hsu, Y.-C. Educational 360-Degree Videos in Virtual Reality: A Scoping Review of the Emerging Research. TechTrends 2020, 64, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, H.; Lara-Alvarez, C.; Parra, E.; Villalba-Condori, K. Virtual Tours to Facilities for Educational Purposes: A Review. TEM J. 2023, 12, 1725–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieva García, O.; Luna González, P.; Arellano Pimentel, J. Comparativa de características de software para la creación de recorridos virtuales 360 en Web. Rev. Investig. Tecnol. Inf. 2021, 9, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuire, S. One map to rule them all? Google Maps as digital technical object. Commun. Public 2019, 4, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenković, N.; Bakač, A.; Slivar, I. Photo representation of EU cities on Google Maps: 2016 and 2022 comparison. Zb. Rad. Departmana za Geogr. Turiz. i Hotel. 2022, 3, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, V.J.D.; Chang, C.-T. Feature Positioning on Google Street View Panoramas. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2012, I-4, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, A.N.; Ibrahim, H.M. Online Destinations Map using Google Maps API Based on the Private Database. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Comput. Eng. 2023, 3, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzerillo, L. Integrated SfM techniques using data set from google earth 3d model and from street level. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, XLII-2/W5, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paor, D.G.; Dordevic, M.M.; Karabinos, P.; Burgin, S.; Coba, F.; Whitmeyer, S.J. Exploring the reasons for the seasons using Google Earth, 3D models, and plots. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2017, 10, 582–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobert, J.; Wild, S.C.; Rossi, L. Testing the effects of prior coursework and gender on geoscience learning with Google Earth. In Google Earth and Virtual Visualizations in Geoscience Education and Research; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sahray, K.; Sukereman, A.S.; Rosman, S.H.; Jaafar, F.N.H. The Implementation of Virtual Reality (Vr) Technology in Real Estate Industry. Plan. Malays. 2023, 21, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, T.F.; Zou, Y. Improving search efficiency in housing markets using online listings. Real Estate Econ. 2024, 52, 1020–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, M.Z.; Aziz, M.N.A.; Bakar, M.H.A.; Halili, N.A.; Azuddin, M.A. Matterport: Virtual Tour as A New Marketing Approach in Real Estate Business During Pandemic COVID-19. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Innovation in Media and Visual Design (IMDES 2020), Tangerang, Indonesia, 10–11 November 2020; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, P.M.C.; Zhang, H.Q.; Hung, K.; Lin, B.; Fan, D.X.F. Stakeholders’ views of travelers’ choice of Airbnb. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 1037–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Biljecki, F. The implementation of big data analysis in regulating online short-term rental business: A case of airbnb in beijing. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, IV-4/W9, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duso, T.; Michelsen, C.; Schaefer, M.; Tran, K.D. Airbnb and rental markets: Evidence from Berlin. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2024, 106, 104007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kőszegi, M.; Gessert, A.; Nestorová-Dická, J.; Gruber, P.; Bottlik, Z. Social assessment of national parks through the example of the Aggtelek National Park. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2022, 71, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Kim, Y. From Image-Based to Immersive: Exploring Virtual Museums that enhance Accessibility and Forms of Museums. J. Digit. Media Cult. Technol. 2023, 3, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Stash, N.; Sambeek, R.; Schuurmans, Y.; Aroyo, L.; Schreiber, G.; Gorgels, P. Cultivating Personalized Museum Tours Online and On-Site. Interdiscip. Sci. Rev. 2009, 34, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levonis, S.M.; Tauber, A.L.; Schweiker, S.S. 360 C Virtual Laboratory Tour with Embedded Skills Videos. J. Chem. Educ. 2021, 98, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafar, I.A.; Arif, Z.; Syefudin, S. Systematic Literature Review: Virtual Tour 360 Degree Panorama. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Lai, I.K.W. A Systematic Literature Review of Virtual Technology in Hospitality and Tourism (2013–2022). SAGE Open 2023, 13, 21582440231193297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, D.; McKechnie, J.; Edgerton, E.; Wilson, C. Immersive virtual reality as a pedagogical tool in education: A systematic literature review of quantitative learning outcomes and experimental design. J. Comput. Educ. 2021, 8, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadiev, R.; Yang, L.; Huang, Y.M. A review of research on 360-degree video and its applications to education. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2022, 54, 784–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranieri, M.; Luzzi, D.; Cuomo, S.; Bruni, I. If and how do 360° videos fit into education settings? Results from a scoping review of empirical research. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2022, 38, 1199–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silveira, T.L.T.; Jung, C.R. Dense 3D Indoor Scene Reconstruction from Spherical Images. In Proceedings of the Conference on Graphics, Patterns and Images (SIBRAPI Estendido 2020); Sociedade Brasileira de Computação: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2020; pp. 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Sandnes, F.E.; Huang, Y.-P. Translating the viewing position in single equirectangular panoramic images. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Budapest, Hungary, 9–12 October 2016; pp. 000389–000394. [Google Scholar]

- Kingstone, H. Contemporary History in Panoramas. In Panoramas and Compilations in Nineteenth-Century Britain: Seeing the Big Picture; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 27–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Khan, N.; Mahroof Khan, M.; Ashraf, S.; Hashmi, M.S.; Khan, M.M.; Hishan, S.S. Post-COVID 19 Tourism: Will Digital Tourism Replace Mass Tourism? Sustainability 2021, 13, 5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Campos, M.; Guzmán-Arias, L.C.; Aguilar-Cordero, J.F.; Rojas-Muñoz, E.; Leandro-Elizondo, R.; Law, Y.C. Improving Motivation and Learning Experience with a Virtual Tour of an Assembly Line to Learn about Productivity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, C.; Saorín, J.L.; Díaz Parrilla, S.; Bonnet de León, A.; Melián Díaz, D. User Experience of Virtual Heritage Tours with 360° Photos: A Study of the Chapel of Dolores in Icod de los Vinos. Heritage 2024, 7, 2477–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keep, T. The Mernda VR Project: The Creation of a VR Reconstruction of an Australian Heritage Site. J. Comput. Appl. Archaeol. 2022, 5, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemtinov, V.A.; Borisenko, A.B.; Morozov, V.V.; Nemtinova, Y.V.; Nemtinov, K.V. Visualization of Digital Transformation of Industrial Production into the Educational Process. Sci. Vis. 2022, 14, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosser, P.F.; Xia, Z.; Alt, J.; Rüppel, U.; Schmalz, B. Virtual field trips in hydrological field laboratories: The potential of virtual reality for conveying hydrological engineering content. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 6977–7003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeloni, R. Digitization and Virtual Experience of Museum Collections. The Virtual Tour of the Civic Art Gallery of Ancona. IT-SCIentific Res. Inf. Technol. 2023, 12, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisusilo, A. Design and Development of Android-based interactive 3D Virtual Tours for Campuses. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2024, 5, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Af’idah, D.I. Virtual Tour As A Tourist Attraction Promotion Media Using Multimedia Development Life Cycle. Int. Conf. Digit. Adv. Tour. Manag. Technol. 2023, 1, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wu, W.; Morales, G.; Mohammadiyaghini, E. Immersive Virtual Field Trips with Virtual Reality in Construction Education: A Pilot Study. EPiC Ser. Built Environ. 2022, 3, 614–623. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Albeaino, G.; Gheisari, M.; Eiris, R. Virtual Collaborative Spaces for Online Site Visits: A Plan-Reading Pilot Study. EPiC Ser. Built Environ. 2022, 3, 688–696. [Google Scholar]

- Guichet, P.L.; Huang, J.; Zhan, C.; Millet, A.; Kulkarni, K.; Chhor, C.; Mercado, C.; Fefferman, N. Incorporation of a Social Virtual Reality Platform into the Residency Recruitment Season. Acad. Radiol. 2022, 29, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, M.I.; Jenkins, M.; Morison, G. Enhanced low-cost web-based virtual tour experience for prospective students. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops, VRW 2021, Lisbon, Portugal, 27 March 2021–1 April 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 677–678. [Google Scholar]

- Perdana, D.; Irawan, A.; Munadi, R. Implementation of a Web Based Campus Virtual Tour for Introducing Telkom University Building. Int. J. Simul. Syst. Sci. Technol. 2020, 20, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohizan, R.B.; Vistro, D.M.; Puasa, M.R.B. Enhanced visitor experience through campus virtual tour. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1228, 012067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J.; Li, J.; Vinayagamoorthy, V.; Shamma, D.A.; Cesar, P. Proxemics and Social Interactions in an Instrumented Virtual Reality Workshop. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 8–13 May 2021; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro, S.; Grandi, F.; Peruzzini, M.; De Canio, F. Virtual Tours to Promote the Remote Customer Experience. Adv. Transdiscipl. Eng. 2021, 16, 477–486. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez de Ágredos Pascual, M.L.; Fantoni, R.; Francucci, M.; Guarneri, M.; Mongelli, M.; Pierattini, S.; Puccini, M.; Ferrero Gil, S.; Izquierdo Garay, J.C.; Gil Bordallo, J.M. 3D Model Acquisition and Image Processing for the Virtual Musealization of the Spezieria di Santa Maria della Scala, Rome. Heritage 2022, 5, 1253–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemtinov, V.A.; Podina, A.A.; Borisenko, A.B.; Morozov, V.V.; Protasova, Y.V.; Nemtinov, K.V. Integrated Use of Various Software Environments for Increasing the Level of Visualization and Perception of Information. Sci. Vis. 2023, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalving, M.; Paananen, S.; Seppälä, J.; Colley, A.; Häkkilä, J. Comparing VR and Desktop 360 Video Museum Tours. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia, Lisbon, Portugal, 27–30 November 2022; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 282–284. [Google Scholar]

- Masruroh, H.; Sahrina, A.; Al Khalidy, D.; Trihatmoko, E. Generating Mobile Virtual Tour Using UAV and 360 Degree Panorama for Geography-Environmental Learning in Higher Educationw. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2024, 18, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuta, J.; Gill, N.; Rooney, R.; Coombs, A.; Murphy, D. Use of 360° Video for a Virtual Operating Theatre Orientation for Medical Students. J. Surg. Educ. 2021, 78, 391–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, N.Z.; Yanti Mahadzir, S. 360° Virtual Tour of the Traditional Malay House as an Effort for Cultural Heritage Preservation. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; Indonesia, 2020, IOP Publishing Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 764. [Google Scholar]

- Vickery, B.C. Bradford’s Law of Scattering. J. Doc. 1948, 4, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lai, I.K.W. How A 360° virtual tour is more effective than photographs on communication effects: The roles of mental imagery processing and a sense of presence. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 3813–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lai, I.K.W. The psychological premise of spatial presence in 360° virtual tours: The role of the spatial situation in first-time and repeat users. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2023, 14, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lai, I.K.W. The use of 360-degree virtual tours to promote mountain walking tourism: Stimulus–organism–response model. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2022, 24, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lai, I.K.W. The acceptance of augmented reality tour app for promoting film-induced tourism: The effect of celebrity involvement and personal innovativeness. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2021, 12, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Lai, I.K.W.; Fan, Z.B.; Mo, Q.M. The impact of a 360° virtual tour on the reduction of psychological stress caused by COVID-19. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lai, I.K.W. Identifying the response factors in the formation of a sense of presence and a destination image from a 360-degree virtual tour. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 100640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, C.; Alfaro, L.; Luna-Urquizo, J.; Castañeda, E. Self-Reported Measurement of the Impact of 360° VR Images on Affective and Cognitive Responses in Hotel Promotion. In Proceedings of the 2023 Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, and Applied Computing, CSCE 2023, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24–27 July 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1800–1805. [Google Scholar]

- Quecara, S.; Alfaro, L. 360° Virtual reality video tours generation model for hospitality, tourism and education using case-based reasoning. In Proceedings of the EDUNINE 2023—7th IEEE World Engineering Education Conference: Reimaging Engineering—Toward the Next Generation of Engineering Education, Merging Technologies in a Connected World, Bogota, Colombia, 12–15 March 2023; Proceedings. da Rocha Brito, C., M.M., C., Eds.; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Veliz, D.; Ccori, R.; Alfaro, L. Division and composition of 360°videos for the generation of personalized tours for tourism, hotel industry and education based on immersive VR. In Proceedings of the EDUNINE 2023—7th IEEE World Engineering Education Conference: Reimaging Engineering—Toward the Next Generation of Engineering Education, Merging Technologies in a Connected World, Bogota, Colombia, 12–15 March 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro, L.; Rivera, C.; Suarez, E.; Raposo, A. 360° Virtual Reality Video Tours Generation Model for Hostelry and Tourism based on the Analysis of User Profiles and Case-based Reasoning. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2022, 13, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, L.; Rivera, C.; Luna-Urquizo, J.; Arroyo-Paz, A.; Delgado, L.; Castañeda, E. Experiential Marketing Tourism and Hospitality Tours Generation Hybrid Model. Mendel 2023, 29, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, S.; Scioti, A.; Pierucci, A.; Rubino, R.; Di Noia, T.; Fatiguso, F. Verbum—virtual enhanced reality for building modelling (virtual technical tour in digital twins for building conservation). J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2022, 27, 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fino, M.; Bruno, S.; Fatiguso, F. Dissemination, assessment and management of historic buildings by thematic virtual tours and 3D models. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2022, 13, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fino, M.; Ceppi, C.; Fatiguso, F. Virtual tours and informational models for improving territorial attractiveness and the smart management of architectural heritage: The 3d-imp-act project. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, XLIV-M-1-2, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantatore, E.; Lasorella, M.; Fatiguso, F. Virtual reality to support technical knowledge in cultural heritage. The case study of cryptoporticus in the archaeological site of egnatia (Italy). Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2020, 54, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Poretski, L.; Li, J.; Tang, A. Tourgether360: Exploring 360° Tour Videos with Others. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Extended Abstracts, New Orleans, LA, USA, 29 April–5 May 2022; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.; Poretski, L.; Li, J.; Tang, A. Tourgether360: Collaborative Exploration of 360° Videos using Pseudo-Spatial Navigation. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2022, 6, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lyu, J.; Sousa, M.; Balakrishnan, R.; Tang, A.; Grossman, T. Route Tapestries: Navigating 360° Virtual Tour Videos Using Slit-Scan Visualizations. In Proceedings of the UIST 2021—34th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, Virtual Event, 10–14 October 2021; Association for Computing Machinery, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, A.; Fakourfar, O. Watching 360° videos together. In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 2017-May, pp. 4501–4506. [Google Scholar]

- Bogicevic, V.; Seo, S.; Kandampully, J.A.; Liu, S.Q.; Rudd, N.A. Virtual reality presence as a preamble of tourism experience: The role of mental imagery. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogicevic, V.; Liu, S.Q.; Seo, S.; Kandampully, J.; Rudd, N.A. Virtual reality is so cool! How technology innovativeness shapes consumer responses to service preview modes. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyriou, L.; Economou, D.; Bouki, V. Design methodology for 360° immersive video applications: The case study of a cultural heritage virtual tour. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2020, 24, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagler, A.; Hanus, M.D. Comparing Virtual Reality Tourism to Real-Life Experience: Effects of Presence and Engagement on Attitude and Enjoyment. Commun. Res. Reports 2018, 35, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedelty, M. Ecomusicology: Rock, Folk, and the Environment; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-143990712-2. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Yao, M.Z. Strategic use of immersive media and narrative message in virtual marketing: Understanding the roles of telepresence and transportation. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 524–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Nelson, M.R.; Yao, M.Z. Using virtual reality to promote the university brand: When do telepresence and system immersion matter? J. Mark. Commun. 2020, 26, 362–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, O.B.P.; Yan, Y.; Tan, J.S.Y.; Tan, Y.-X.; Tay, G.Q.Y.; Chiam, D.J.; Wang, Y.-C.; Dean, K.; Feng, C.-C. Generating a virtual tour for the preservation of the (in) tangible cultural heritage of Tampines Chinese Temple in Singapore. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 39, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, G.; Barhorst, J.B. Living the Experience Before You Go. but Did It Meet Expectations? The Role of Virtual Reality during Hotel Bookings. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 1233–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]