Understanding Primary School Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Water Management: Insights from Environmental Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Graphical Analysis Using OriginLab 2019b

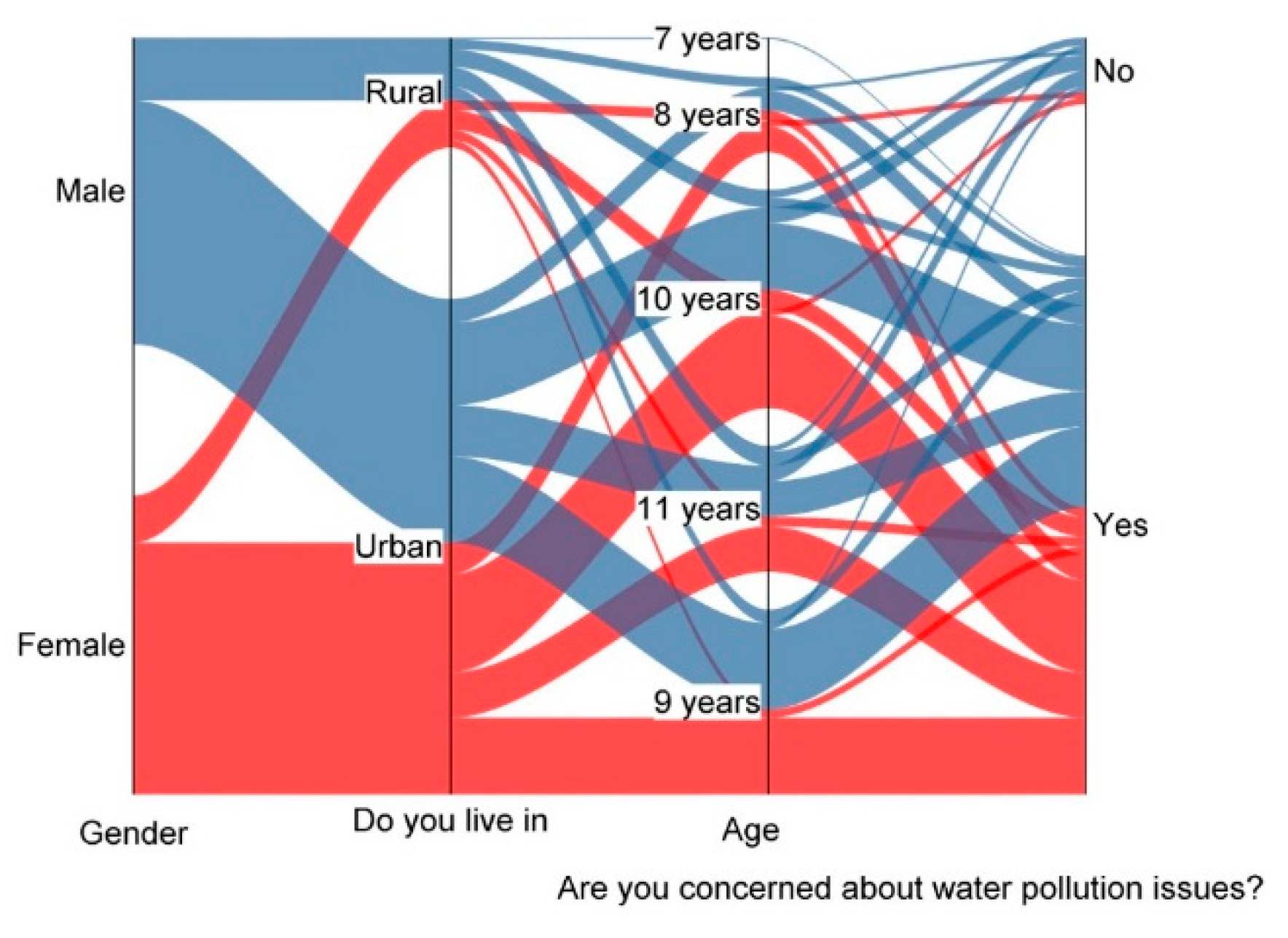

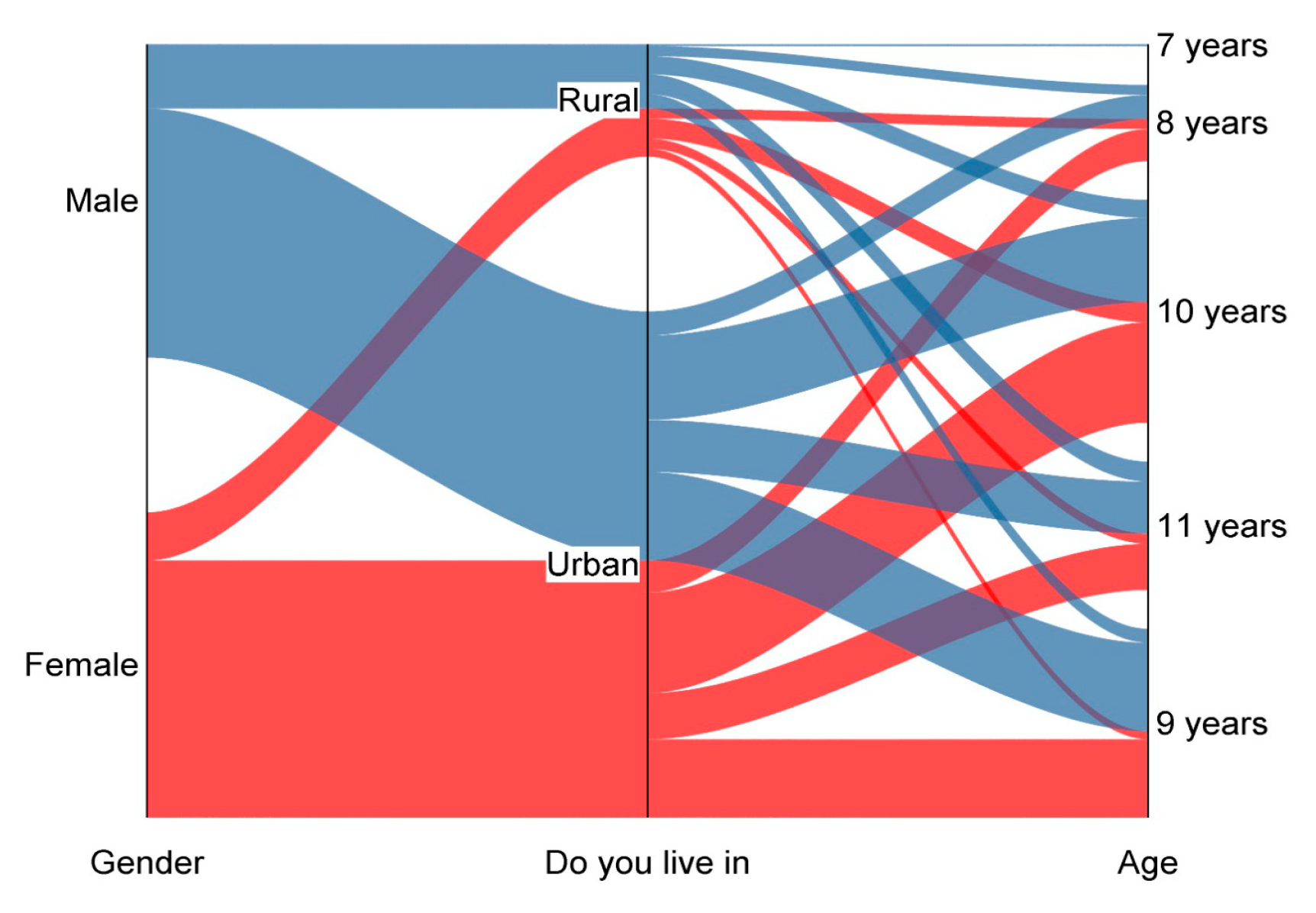

3.1.1. “Are You Concerned About Water Pollution?”

- Gender—it can be seen that 96.05% of girls responded positively and only 82.05% of boys;

- Area where they live—89.25% of urban and 87.5% of rural respondents answered positively to this question;

- Age group—the highest number of respondents who answered positively were those in the 10 years’ age group, followed by those in the 9 years’ age group, 11 years’ age group, 8 years’ age group, and finally the 7 years’ age group;

- The group of 10-year-old girls from an urban environment, composed of 47 respondents;

- The group of girls aged 9 years in urban areas, composed of 39 respondents;

- The group of boys aged 9 years in an urban environment, composed of 41 respondents;

- The group of boys aged 10 years in an urban environment, composed of 34 respondents.

- In relation to the gender of the respondent, there is an equal distribution in terms of number, this characteristic being specific to students living in urban areas;

- Referring to pupils living in rural areas, it is observed that the number of girls is 8 less than the number of boys, which is 32;

- By carrying out the analysis of the data obtained from the questionnaire corresponding to the respondent’s gender and age, we obtained:

- ✓

- The highest number of boys, 51 with 9-year-old students and 51 with 10-year-old students, followed by those aged 11 with 36 and those aged 8 with 17, and the lowest number, 1 participant, was identified at age 7;

- ✓

- For the girls’ group, the highest number of participants was identified as being in the 10-year-old group, followed by the 9-, 11-, and 8-year-old age groups, with 60, 43, 28, and 21 participants, respectively;

- ✓

- A combined analysis of the three characteristics (gender, location, and age) shows that: the largest group of 50 respondents is identified as being in the group of female respondents aged 10 and living in urban areas. Two other large groups were also identified in the case of male respondents corresponding to the ages of 9- and 10-years-old living in an urban environment, these being characterized by a number of 44 and 42 respondents, respectively; the smallest groups of respondents are specific to those living in rural areas, characterized by a maximum number of 10 respondents identified in the group of girls aged 10 and in the group of boys aged 11.

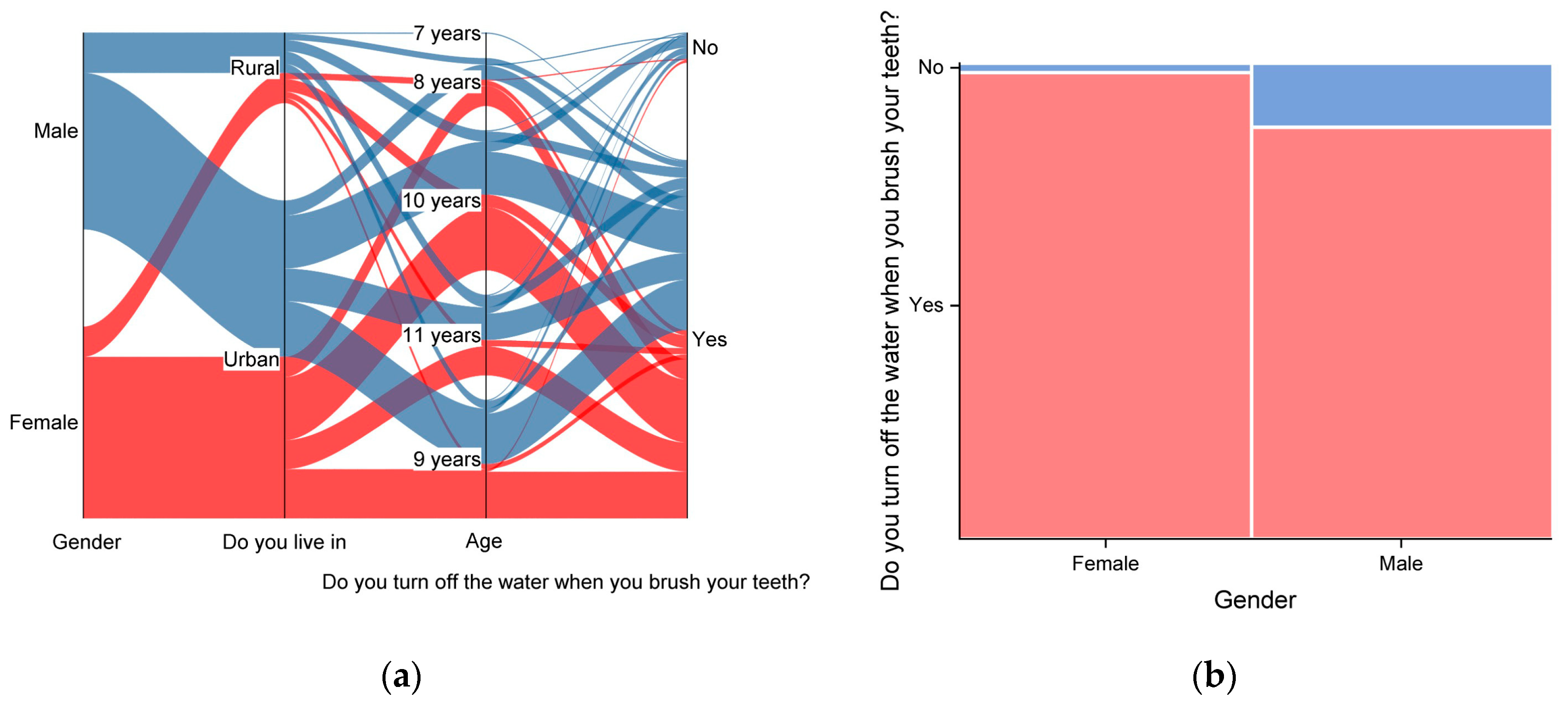

3.1.2. “Do You Turn off the Water When You Brush Your Teeth?”

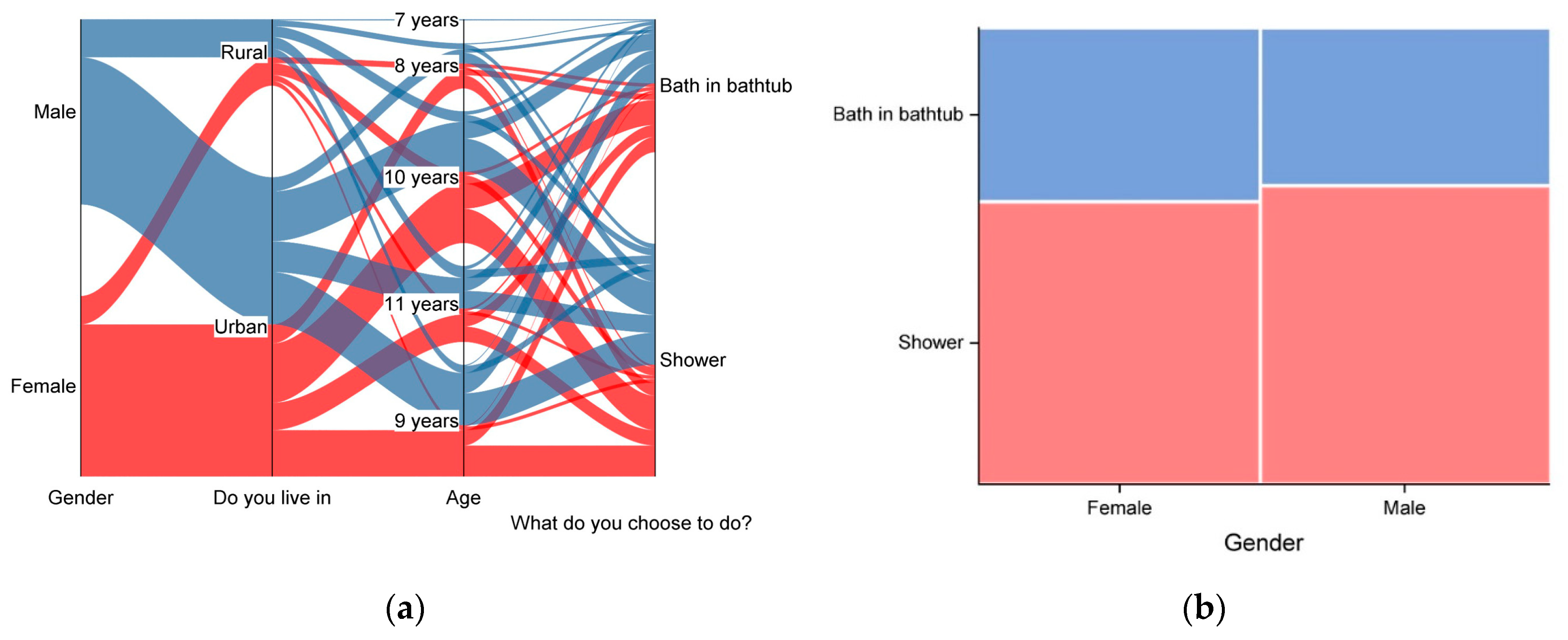

3.1.3. “What Do You Choose to Do?”

- Overall, 51.78% are female and 48.21% are male;

- Concerning the environment of origin, 83.9% of respondents come from urban areas and 16.1% from rural areas;

- Most of the respondents who are 10 years old use this way of performing body hygiene, that is 41 respondents, followed by those aged 9 years, where we have 32 respondents, then those aged 11 years with 26 respondents;

- Those aged 8 years with 12 respondents, and finally those aged 7 years;

- Overall, the group of 10-year-old girls from urban areas who use this way of carrying out personal hygiene is predominant, with 21;

- In this case, the gender distribution is the opposite compared to the responses obtained for “Bath in bathtub”, i.e., 47.95% represents the share of female individuals and 52.05% of male individuals;

- Concerning the environment the weighting is approximately the same as for “Bath in bathtub”, i.e., 80.6% urban and 19.4% rural;

- When analyzing by age group, it was found that the largest number of individuals is made up of those aged 10 (with 70 respondents), followed by those aged 9 (62 respondents), 11 (38 respondents), and 8 (26 respondents);

- Overall, three large groups were identified with 27 respondents, as follows: group of boys aged 11 from urban areas—27 respondents; group of boys aged 10 from urban areas—28 respondents; group of girls aged 10 from urban areas—29 respondents.

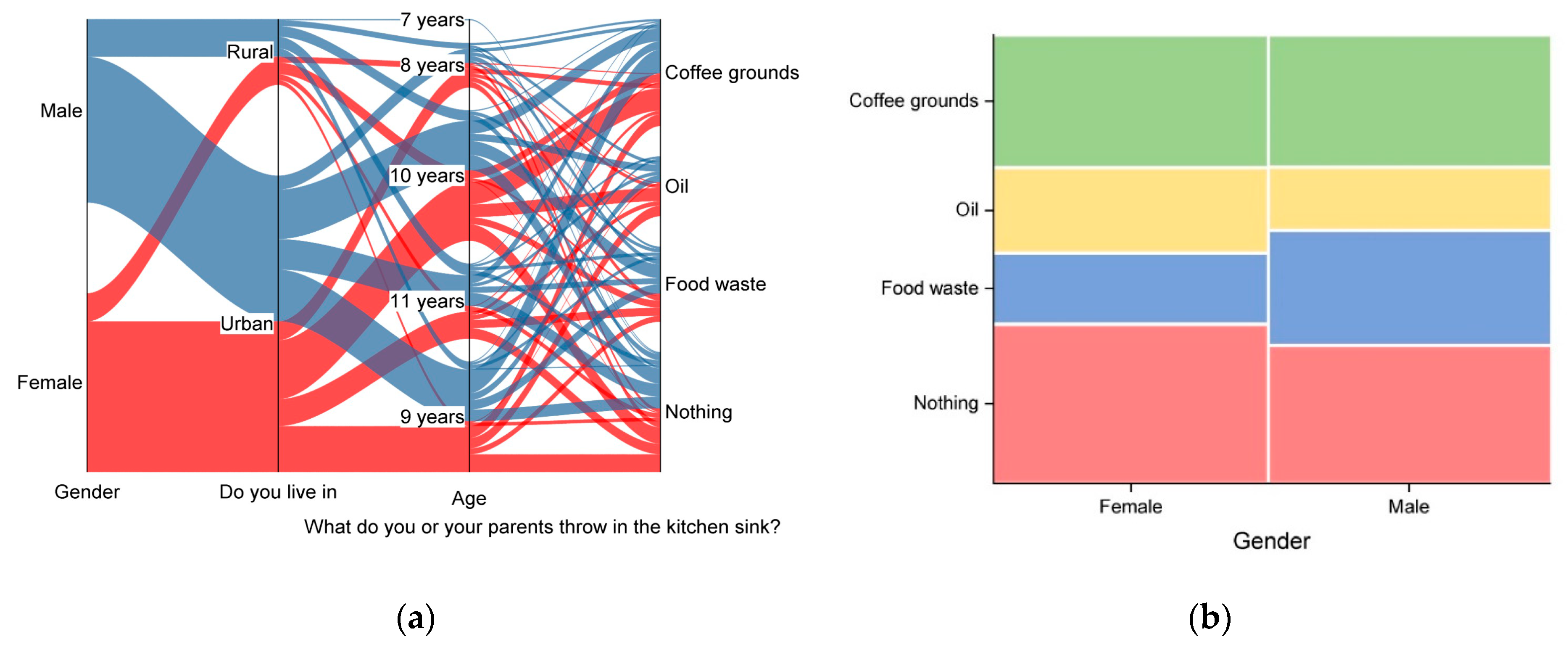

3.1.4. “What Do You or Your Parents Throw in the Kitchen Sink?”

- Regardless of the gender under analysis, it is found that the largest share of responses is for “Nothing”, with 35.53% for girls and 30.77% for boys. The second category found from the data analysis is “Coffee grounds” with approximately the same share for both groups—29.6% for girls and 29.49% for boys. The other products analyzed were “Food waste” at 15.79% for girls and 25.64% for boys, and “Oil” at 19.08% for girls and 14.1% for boys;

- Analyzing from the point of view of the area where the respondent lives, the highest number of responses was obtained for “Nothing”, at 79, i.e., 31.35% of those living in urban areas and 23, i.e., 41.07% of those living in rural areas. For “Coffee grounds”, 30.56% of those living in urban areas and 25% of those living in rural areas chose this answer. For the other answer options we have for “Food waste” 51 urban and 13 rural respondents, and for “Oil”, there are 45 urban and 6 rural respondents;

- When analyzing the responses by age group, due to the large number of data and the complexity of interpretation, it was decided to present the most representative values, i.e., the highest percentage values were obtained for: the group of students aged 11 years, 43.75% of them chose the answer “Nothing”; the group of students aged 10 years, 34. 23% of them opted for the answer “Coffee grounds”; the same answer was chosen by 32.98% of the pupils aged 9 years; also, only 30.85% of the pupils aged 9 years opted for the answer “Nothing”; for the other age groups and answers, the share is below 30%.

- A total of 19 female respondents aged 10 living in urban areas chose the answer “Coffee grounds”;

- A total of 15 female respondents aged 9 living in urban areas chose the answer “Nothing”;

- For the same answer, “Nothing”, a group of 14 female respondents aged 10 living in urban areas were identified;

- For the response “Coffee grounds”, the largest group of 20 respondents was identified in the category of 9-year-old males living in urban areas;

3.1.5. “What Items Are Flushed Down Your Toilet (WC)?”

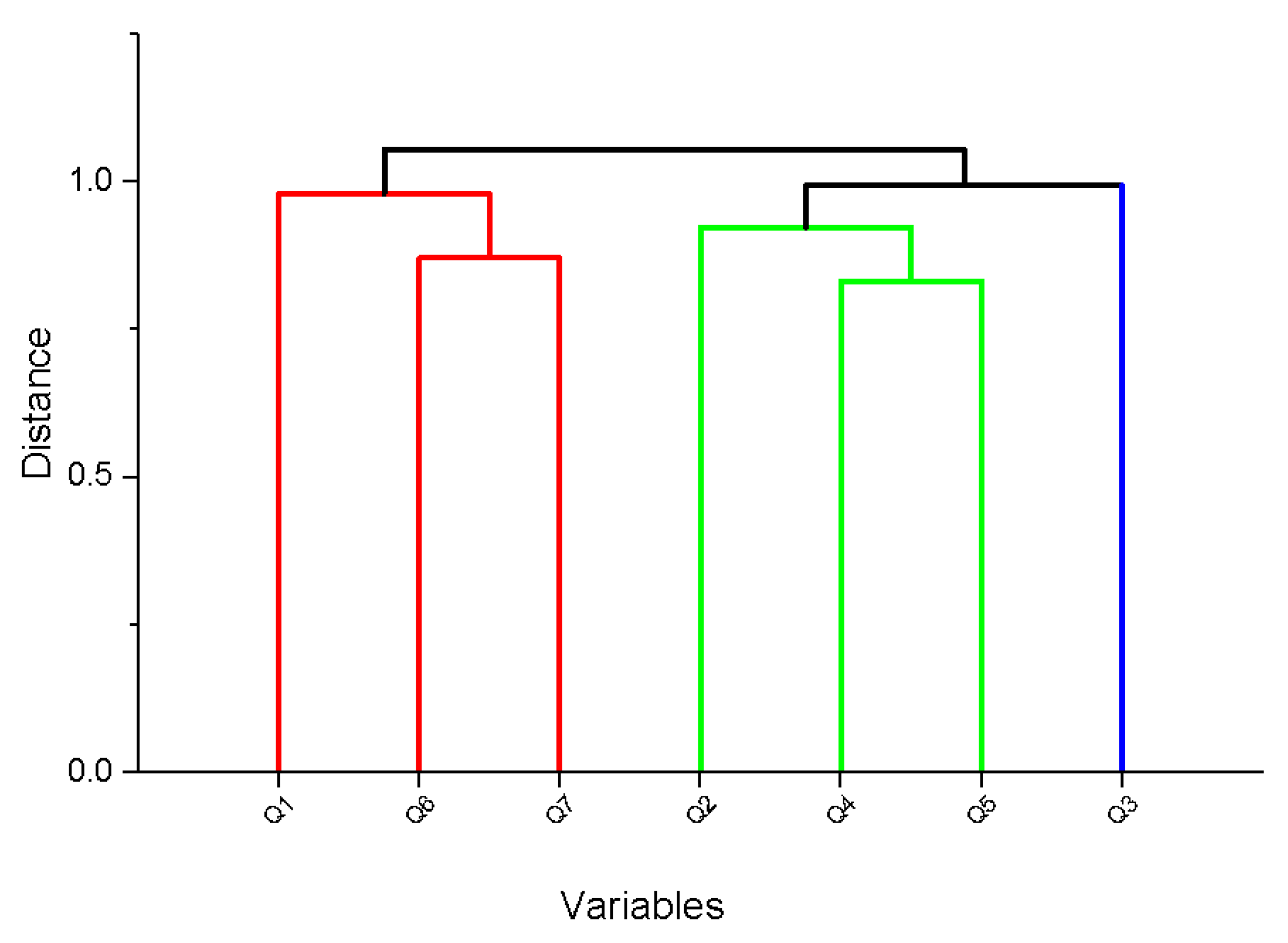

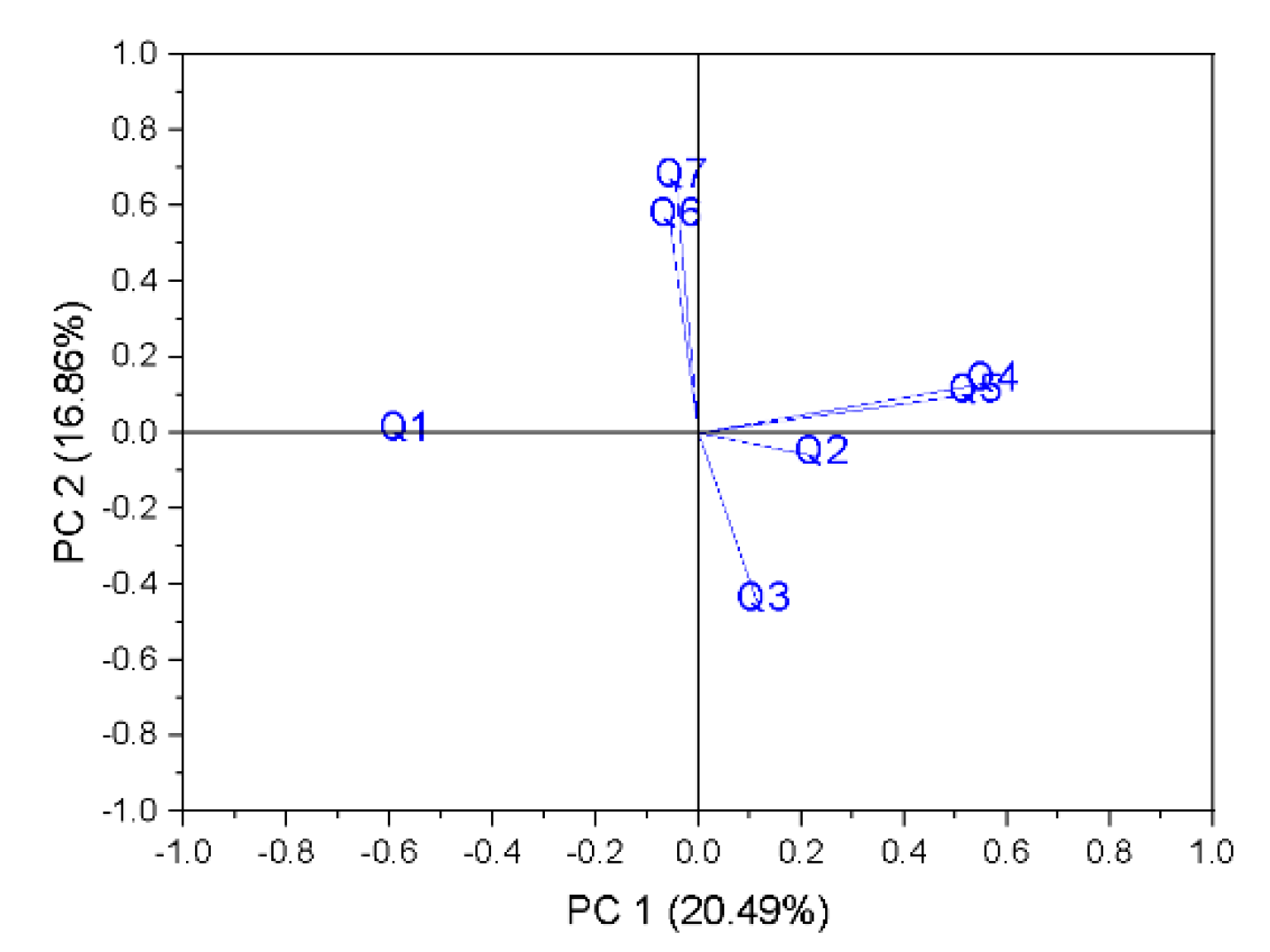

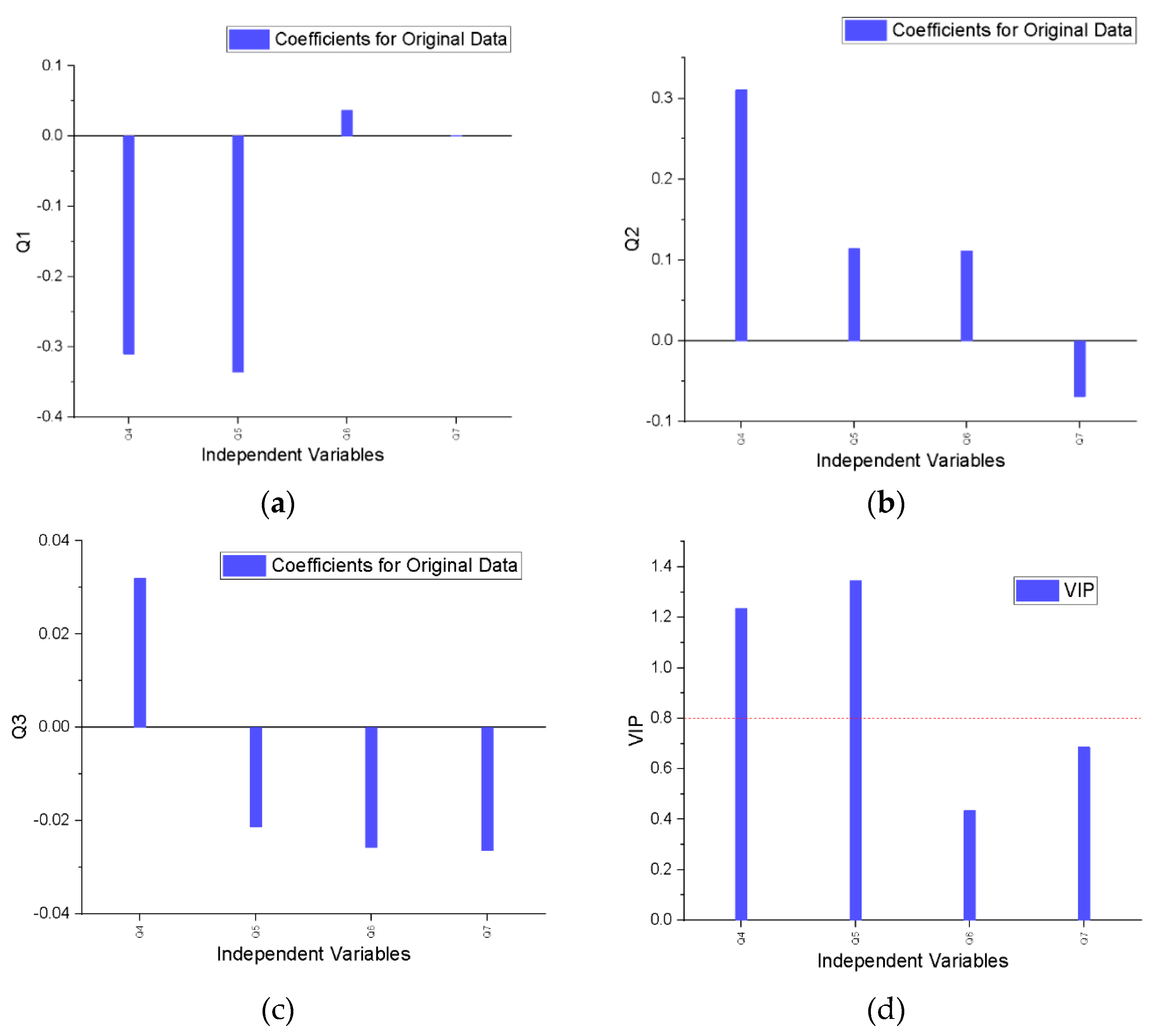

3.2. Statistical Analysis Performed Using OriginLab Software

- The first formed from questions Q4 and Q5, the second formed from questions Q6 and Q7;

- Regarding the two secondary clusters: question Q2 is added to the first cluster, and question Q1 is added to the second cluster;

- Question Q3 is outside the obtained clusters;

- Analyzing the obtained result, it can be said that question Q1 has a significant impact on the answers obtained to questions Q6 and Q7; question Q2 has a significant impact on the answers obtained to questions Q4 and Q5;

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Taking gender into account, an equal distribution of children was observed in the study (156 boys and 152 girls);

- The majority of the respondents are from urban areas; this is mainly due to the fact that the school chosen to participate in this study is located in Bacău and is situated 1.8 km from the city center;

- The predominant age group of respondents is given by those aged 10 years, followed by those aged 9 years, 11 years, 8 years, and the last being those aged 7 years;

- Regarding the way of conserving water resources, it was observed that there is a significant rate of people who turn off the water when brushing their teeth;

- The same conclusion can be drawn about the way of performing intimate hygiene, i.e., more than half of the respondents prefer showering instead of bathing;

- Regarding the habits related to throwing waste in the kitchen sink, it can be observed that the majority of respondents do not throw anything in the sink;

- Concerning the items thrown in the toilet bowl, there is a considerable variety of products, with a significant weight attributed to the category “other products”, which are not specified in the list provided. In the second place are wet wipes. There is also a significant percentage of people who do not flush anything down the toilet. Overall, there is a diversity of items that are flushed down the toilet, highlighting the need for education and awareness of the impact on the sewerage system and the environment.

- The conclusion of the statistical analysis conducted shows that there are significant correlations between the questions asked of the respondents, which can be grouped into certain clusters or related through Principal Component Analysis and Partial Least Squares Analysis, such as: Gender + What do you choose to do? + What do you or your parents throw in the kitchen sink? Age + Are you concerned about water pollution issues? + Do you turn off the water when you brush your teeth?

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fróna, D.; Szenderák, J.; Harangi-Rákos, M. The Challenge of Feeding the World. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Muñoz, M.P.; Martín-Gámez, C.; Velasco-Martínez, L.C.; Tójar-Hurtado, J.C. Research and Development of Environmental Awareness about Water in Primary Education Students through Their Drawings. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avtar, R.; Tripathi, S.; Aggarwal, A.K.; Kumar, P. Population–Urbanization–Energy Nexus: A Review. Resources 2019, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximillian, J.; Brusseau, M.L.; Glenn, E.P.; Matthias, A.D. Chapter 25—Pollution and Environmental Perturbations in the Global System. In Environmental and Pollution Science, 3rd ed.; Brusseau, M.L., Pepper, I.L., Gerba, C.P., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 457–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandh, S.A.; Shafi, S.; Peerzada, M.; Rehman, T.; Bashir, S.; Wani, S.A.; Dar, R. Multidimensional analysis of global climate change: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 24872–24888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nourredine, H.; Barjenbruch, M.; Million, A.; El Amrani, B.; Chakri, N.; Amraoui, F. Linking Urban Water Management, Wastewater Recycling, and Environmental Education: A Case Study on Engaging Youth in Sustainable Water Resource Management in a Public School in Casablanca City, Morocco. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djankov, S.; Saliola, F.; Avitabile, C.; Chen, R.D.; Connon, D.L.; Cusolito, A.P.; Gatti, R.V.; Gentilini, U.; Islam, A.M.; Kraay, A.C.; et al. World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work (Vol. 1 of 2): Main Report (English). Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/816281518818814423/main-report (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Garito, M.A.; Caforio, A.; Falegnami, A.; Tomassi, A.; Romano, E. Shape the EU future citizen. Environ. Educ. Eur. Green Deal. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.; So, H.-J. Role of environmental interaction in interdisciplinary thinking: From knowledge resources perspectives. J. Environ. Educ. 2019, 50, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segoni, S. A role-playing game to complement teaching activities in an ‘environmental impact assessment’ teaching course. Environ. Res. Commun. 2022, 4, 051003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asah, S.T.; Bengston, D.N.; Westphal, L.M.; Gowan, C.H. Mechanisms of Children’s Exposure to Nature: Predicting Adulthood Environmental Citizenship and Commitment to Nature-Based Activities. Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 807–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanuwat, P.K.C.; Viriya, T.; Wee, R.; Sumit, S.; Seree, W. Factors influencing science and environmental education learning of blind students: A case of primary school for the blind in Thailand. Int. J. Educ. Pract. 2023, 11, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piras, S.; Righi, S.; Banchelli, F.; Giordano, C.; Setti, M. Food waste between environmental education, peers, and family influence. Insights from primary school students in Northern Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 383, 135461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodanovic, R.; Puvaca, N. Level of elementary school student’s knowledge bout nature and their behavior in the environment. In Proceedings of the 89th International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development—”Economical, Agricultural and Legal Frameworks of Sustainable Development”—Novi Sad, Novi Sad, Serbia, 4–5 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Amran, A.; Perkasa, M.; Satriawan, M.; Jasin, I.; Irwansyah, A. Assessing students 21st century attitude and environmental awareness: Promoting education for sustainable development through science education. Proc. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1157, 022025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, P.; Kydonakis, P.; Botzori, M.; Skanavis, C. Augmented reality proves to be a breakthrough in Environmental Education. In Proceedings of the Protection and Restoration of the Environment XIV, Thessaloniki, Grecia, 3–6 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, T.T.P.; Kato, T. Measuring the effect of environmental education for sustainable development at elementary schools: A case study in Da Nang city, Vietnam. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2016, 26, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefländer, A.K.; Bogner, F.X. Educational impact on the relationship of environmental knowledge and attitudes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaydin, E.; Demirel, G.; Altin, S.; Altin, A. Environmental Knowledge of Primary School Students: Zonguldak (Turkey) Example. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 141, 1150–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, M. The Effects of Ecology-Based Summer Nature Education Program on Primary School Students’ Environmental Knowledge, Environmental Affect and Responsible Environmental Behavior. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2011, 11, 2233–2237. [Google Scholar]

- Grodzinska-Jurczak, M.; Bartosiewicz, A.; Twardowska, A.; Ballantyne, R. Evaluating the Impact of a School Waste Education Programme upon Students’, Parents’ and Teachers’ Environmental Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviour. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2003, 12, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajiboye, J.O.; Olatundun, S.A. Impact of Some Environmental Education Outdoor Activities on Nigerian Primary School Pupils’ Environmental Knowledge. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2010, 9, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaardingerbroek, B.; Taylor, T.G.N. The Environmental Knowledge and Attitudes of Prospective Teachers in Lebanon: A Comparative Study. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2007, 16, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Bowers, A.W.; Roth, N.W.; Holthuis, N. Environmental education and K-12 student outcomes: A review and analysis of research. J. Environ. Educ. 2018, 49, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marianne, E.K. Advancing Environmental Education Practice; Comstock Publishing Associates, Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA; London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson, S.N.; Stephens, J.C.; White, B. Environmental education in transition: A critical review of recent research on climate change and energy education. J. Environ. Educ. 2019, 50, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselow, M.; Stoll-Kleemann, S. Role-playing games in natural resource management and research: Lessons learned from theory and practice. Geogr. J. 2018, 184, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.; Thomas, I. ‘The learning sticks’: Reflections on a case study of role-playing for sustainability. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeth, A.M.; Carter, K. Climate change summit: Testing the impact of role playing games on crossing the knowledge to action gap. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 29, 1796–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, S.C.; Moore, D.; Barnes, M. Teacher Identities as Key to Environmental Education for Sustainability Implementation: A Study From Australia. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2018, 34, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schild, R. Fostering environmental citizenship: The motivations and outcomes of civic recreation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. Taylor Fr. J. 2018, 61, 924–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, S.L.; Huang, L. Environmental Citizenship in a Nordic Civic and Citizenship Education Context. Nord. J. Comp. Annd Int. Education 2019, 3, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Borchers, C.; Boesch, C.; Riedel, J.; Guilahoux, H.; Ouattara, D.; Randler, C. Environmental Education in Côte d’Ivoire/West Africa: Extra-Curricular Primary School Teaching Shows Positive Impact on Environmental Knowledge and Attitudes. Int. J. Sci. Educ. Part B 2014, 4, 240–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanišić, J.; Maksić, S. Environmental Education in Serbian Primary Schools: Challenges and Changes in Curriculum, Pedagogy, and Teacher Training. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 45, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarroll, M.; Hamann, H. What We Know about Water: A Water Literacy Review. Water 2020, 12, 2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vliet, M.T.H.; Jones, E.R.; Flörke, M.; Franssen, W.H.P.; Hanasaki, N.; Wada, Y.; Yearsley, J.R. Global water scarcity including surface water quality and expansions of clean water technologies. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 024020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhary, P.; Bharagava, R.N.; Mishra, S.; Khan, N. Role of Industries in Water Scarcity and Its Adverse Effects on Environment and Human Health. In Environmental Concerns and Sustainable Development: Volume 1: Air, Water and Energy Resources; Shukla, V., Kumar, N., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, J.; Jaffe, J.; Lombardi, D.; Holzer, M.A.; Roemmele, C. Students’ Scientific Evaluations of Water Resources. Water 2020, 12, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amahmid, O.; El Guamri, Y.; Yazidi, M.; Razoki, B.; Kaid Rassou, K.; Rakibi, Y.; Knini, G.; El Ouardi, T. Water education in school curricula: Impact on children knowledge, attitudes and behaviours towards water use. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2019, 28, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzaberis, N. Investigating Students’ Knowledge of Water Issues in the Context of Education for Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the 12th annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation, Seville, Spain, 11–13 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Uralovich, K.S.; Toshmamatovich, T.U.; Kubayevich, K.F.; Sapaev, I.B.; Saylaubaevna, S.S.; Beknazarova, Z.F.; Khurramov, A. A primary factor in sustainable development and environmental sustainability is environmental education. Casp. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 21, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Chi, A.A.; Viga-de Alva, M.D. Environmental education (EE) policy and content of the contemporary (2009–2017) Mexican national curriculum for primary schools. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 564–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Crt. nr. | Year/Location | The Sample of Respondents | Number of Questionnaires | The Environmental Problem Addressed | Number of Questions/Water Questions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2023 Thailand | students aged between 5 and 11 years | 56 | attitude towards the environment; environmental knowledge, in general | 26/NO | [12] |

| 2. | 2023 Modena, Italy | students aged between 10 and 11 years | 420 | waste management | -/NO | [13] |

| 3. | 2022 Novi Sad, Serbia | third grade and sixth grade students | 127 | biodiversity, environmental knowledge, in general | 12/NO | [14] |

| 4. | 2019 Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia | sixth grade students | 184 | education for sustainable development | -/NO | [15] |

| 5. | 2018 Athens, Greece | fourth, fifth, and sixth grade students | 241 | waste, renewable energy | 13/NO | [16] |

| 6. | 2016 Da Nang, Vietnam | first through fifth grades | 247 | sustainable development | 32/YES | [17] |

| 7. | 2015 Bavaria, Germany | fourth grade students | 133 | attitude towards the environment; environmental knowledge, in general | 20/YES | [18] |

| 8. | 2014 Zonguldak, Turkey | students from the third and fourth grade primary school | 130 | participation of students into recycling activities | 15/NO | [19] |

| 9. | 2011 Côte d’Ivoire, West Africa | fifth and sixth grade students | 145 | attitude towards the environment; environmental knowledge | 25/NO | [20] |

| 10. | 2010 Ankara, Turkey | students aged between 8 and 13 years | 64 | knowledge about ecological and environmental concepts | 15/NO | [21] |

| 11. | 2010 Kraków, Poland | students aged between 11 and 13 years | 220 | knowledge regarding waste management in Poland | 11/NO | [22] |

| 12. | 2010 Ibadan, Nigeria | primary school students | 480 | air pollution | -/NO | [23] |

| 13. | 2018 Lebanon and Australia | final-year primary student | 87/169 | environmental knowledge, in general | -/YES | [24] |

| Question | Gender | Age | Do You Live in? | Are You Concerned About Water Pollution Issues? | Do You Turn off the Water When You Brush Your Teeth? | What Do You Choose to Do | What Do You or Your Parents Throw in the Kitchen Sink? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Irimia, O.; Tomozei, C.; Panainte-Lehadus, M.; Chitimus, D.; Nedeff, F.; Barsan, N.; Mosnegutu, E.; Mirila, D. Understanding Primary School Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Water Management: Insights from Environmental Education. Societies 2025, 15, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040109

Irimia O, Tomozei C, Panainte-Lehadus M, Chitimus D, Nedeff F, Barsan N, Mosnegutu E, Mirila D. Understanding Primary School Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Water Management: Insights from Environmental Education. Societies. 2025; 15(4):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040109

Chicago/Turabian StyleIrimia, Oana, Claudia Tomozei, Mirela Panainte-Lehadus, Dana Chitimus, Florin Nedeff, Narcis Barsan, Emilian Mosnegutu, and Diana Mirila. 2025. "Understanding Primary School Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Water Management: Insights from Environmental Education" Societies 15, no. 4: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040109

APA StyleIrimia, O., Tomozei, C., Panainte-Lehadus, M., Chitimus, D., Nedeff, F., Barsan, N., Mosnegutu, E., & Mirila, D. (2025). Understanding Primary School Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Water Management: Insights from Environmental Education. Societies, 15(4), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040109