A Review of Qualitative Studies of Parents’ Perspectives on Climate Change

Abstract

1. Introduction

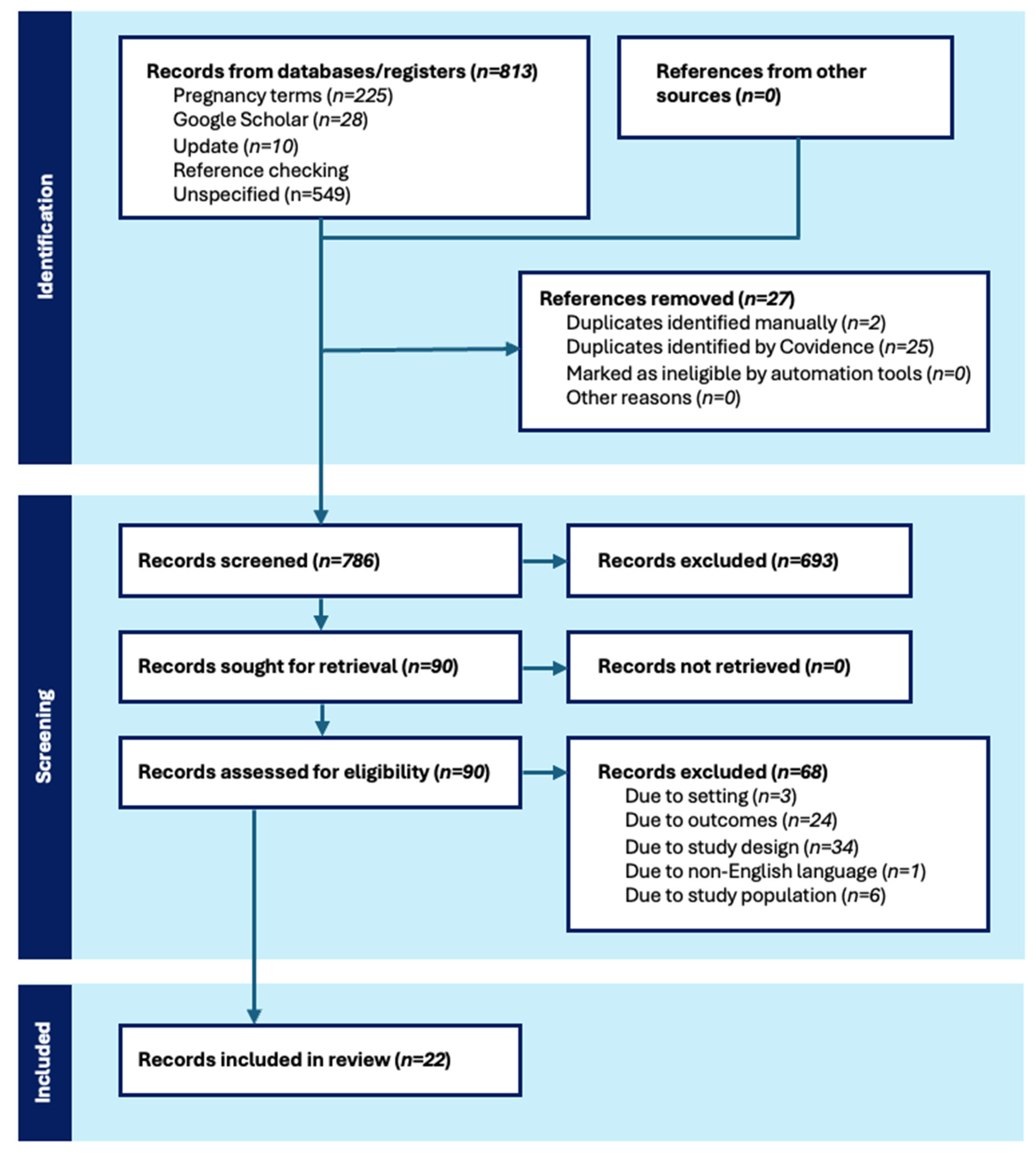

2. Methods

3. Results

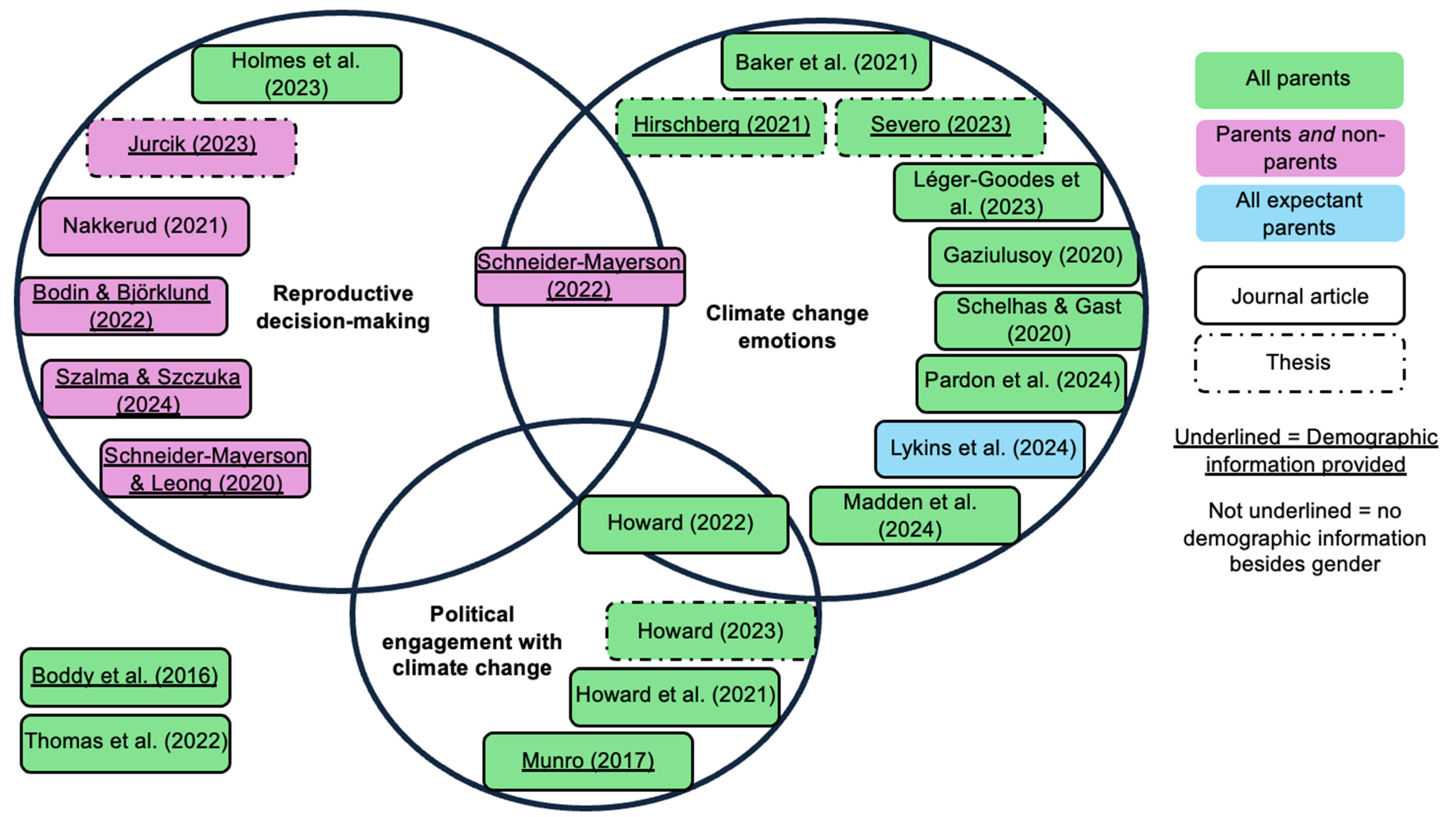

3.1. Focus of the Studies

3.2. Study Populations

3.3. Participant Profiles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patz, J.A.; Gibbs, H.K.; Foley, J.A.; Rogers, J.V.; Smith, K.R. Climate Change and Global Health: Quantifying a Growing Ethical Crisis. EcoHealth 2007, 4, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helldén, D.; Andersson, C.; Nilsson, M.; Ebi, K.L.; Friberg, P.; Alfvén, T. Climate change and child health: A scoping review and an expanded conceptual framework. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e164–e175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. The Climate Crisis is a Child Rights Crisis: Introducing the Children’s Climate Risk Index; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/105376/file/UNICEF-climate-crisis-child-rights-crisis.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; Van Susteren, L. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, Y.; Bhullar, N.; Durkin, J.; Islam, M.S.; Usher, K. Understanding Eco-anxiety: A Systematic Scoping Review of Current Literature and Identified Knowledge Gaps. J. Clim. Change Health 2021, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donger, E. Children and Youth in Strategic Climate Litigation: Advancing Rights through Legal Argument and Legal Mobilization. Transnatl. Environ. Law 2022, 11, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.E. Storms of My Grandchildren: The Truth About the coming Climate Change catastrophe And Our Last Chance to Save Humanity; Bloomsbury: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.C.; Marais, B.; Isaacs, D.; Preisz, A. Ethical considerations regarding the effects of climate change and planetary health on children. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2021, 57, 1775–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. Introduction to YOUNGO. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Introduction%20to%20YOUNGO%202022.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Office for National Statistics. Childbearing for Women Born in Different Years, England and Wales: 2021 and 2022. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/conceptionandfertilityrates/bulletins/childbearingforwomenbornindifferentyearsenglandandwales/previousReleases (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Office of the Commissioner for Wales. Well-Being of Future Generations (Wales) Act. Available online: https://www.futuregenerations.wales/about-us/future-generations-act/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Groves, C.; Adam, B. Future Matters: Action, Knowledge, Ethics; Brill Academic Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, J. Children and civil society. In The Golden Chain: Family, Civil Society and the State; Nautz, J., Ginsborg, P., Nijhuis., T., Eds.; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D.F. Representing future generations: Political presentism and democratic trusteeship. In Democracy, Equality, and Justice, 1st ed.; Matravers, M., Meyer, L.H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Treaty Bodies. Statement of the Committee on the Rights of the Child on Article 5 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/hrbodies/crc/statements/CRC-Article-5-statement.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Köppen, K.; Mazuy, M.; Toulemon, L. Childlessness in France. In Childlessness in Europe: Contexts, Causes, and Consequences; Kreyenfeld, M., Konietzka, D., Eds.; Demographic Research Monographs; Springer: Champagne, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rotkirch, A.; Miettinen, A. Childlessness in Finland. In Childlessness in Europe: Contexts, Causes, and Consequences; Kreyenfeld, M., Konietzka, D., Eds.; Demographic Research Monographs; Springer: Champagne, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. Percentage of Childless Women in the United States in 2020, by Age. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/241535/percentage-of-childless-women-in-the-us-by-age/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Graham, H.; Gao, N.; Glerum-Brooks, K.; Golder, S.; Lampard, P.; Lister, J.; Petticrew, M. Informing Public Health Messaging on Health and Climate Change. Available online: https://www.phpru.online/projects/completed-projects/informing-public-health-messaging-on-health-and-climate-change.html (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Li, Z.; Khurshid, A.; Rauf, A.; Qayyum, S.; Calin, A.C.; Iancu, L.A.; Wang, X. Climate change and the UN-2030 agenda: Do mitigation technologies represent a driving factor? New evidence from OECD economies. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2023, 25, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Family Database. Available online: https://web-archive.oecd.org/temp/2024-06-21/69263-database.htm (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. xv, 336. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.A.; Duncan, A.A. Systematic and scoping reviews: A comparison and overview. Semin. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 35, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golder, S.; Lampard, P.; Glerum-Brooks, K.; Graham, H. Parental Concern About Climate Change’s Impacts on Children: A Scoping Review of qualitative Studies (Reviewregistry1860). Review Registry: 2024. Available online: https://www.researchregistry.com/browse-the-registry#registryofsystematicreviewsmeta-analyses/registryofsystematicreviewsmeta-analysesdetails/669788a2a88410002834fa6f/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO:The SPIDER Tool for Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence. Covidence Systematic Review Software; Covidence: Melbourne, Australia, 2024; Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br. Med. J. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes É, B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.; Roberts, C.; Williamson, R.; Kurz, E.; Barnes, K.; Behie, A.M.; Aroni, R.; Nolan, C.J.; Phillips, C. Opportunities for primary health care: A qualitative study of perinatal health and wellbeing during bushfire crises. Fam. Pract. 2022, 40, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechard, E.; Silverstein, J.; Walke, J. What Are the Impacts of Concern About Climate Change on the Emotional Dimensions of Parents’ Mental Health? A Literature Review. Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, C.; Clayton, S.; Bragg, E. Educating for resilience: Parent and teacher perceptions of children’s emotional needs in response to climate change. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddy, J.; Phoenix, A.; Walker, C.; Vennam, U.; Austerberry, H.; Latha, M. Telling ‘moral tales’? Family narratives of responsible privilege and environmental concern in India and the UK. Fam. Relatsh. Soc. 2016, 5, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, M.; Björklund, J. “Can I take responsibility for bringing a person to this world who will be part of the apocalypse!?”: Ideological dilemmas and concerns for future well-being when bringing the climate crisis into reproductive decision-making. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 302, 114985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaziulusoy, A.İ. The experiences of parents raising children in times of climate change: Towards a caring research agenda. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 2, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberg, T. Strategies Parents Use to Support Adolescents Experiencing Climate Grief. Ph.D. Thesis, Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, USA, 2021. Available online: https://hazards.colorado.edu/news/dissertations/strategies-parents-use-to-support-adolescents-experiencing-climate-grief (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Holmes, M.; Natalier, K.; Pascoe Leahy, C. Unsettling maternal futures in climate crisis: Towards cohabitability? Fam. Relatsh. Soc. 2023, 12, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, L.; Howell, R.; Jamieson, L. (Re)configuring moral boundaries of intergenerational justice: The UK parent-led climate movement. Local Environ. 2021, 26, 1429–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, L. When global problems come home: Engagement with climate change within the intersecting affective spaces of parenting and activism. Emot. Space Soc. 2022, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, L. Where ‘Green’parenting Meets Climate Activism: Understanding the Affective, Political, Generative, but Challenging ‘Space in-Between’of Radical Eco-Parenting. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 2023. Available online: https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/40871 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Jurcik, N. Parental Decision-Making in the Face of Climate Change. Ph.D. Thesis, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, ON, Canada, 2023. Available online: https://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/bitstream/handle/2453/5208/JurcikN2023m-1a.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Léger-Goodes, T.; Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Hurtubise, K.; Simons, K.; Boucher, A.; Paradis, P.-O.; Herba, C.M.; Camden, C.; Généreux, M. How children make sense of climate change: A descriptive qualitative study of eco-anxiety in parent-child dyads. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lykins, A.D.; Bonich, M.; Sundaraja, C.; Cosh, S. Climate change anxiety positively predicts antenatal distress in expectant female parents. J. Anxiety Disord. 2024, 101, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, L.; Joshi, A.; Wang, M.; Turner, J.; Lindsay, S. Parents’ perspectives on climate change education: A case study from New Jersey. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2024, 8, 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, K. Hegemonic stories in environmental advocacy testimonials. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 31, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakkerud, E. “There Are Many People Like Me, Who Feel They Want to Do Something Bigger”: An Exploratory Study of Choosing Not to Have Children Based on Environmental Concerns. Ecopsychology 2021, 13, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardon, M.K.; Dimmock, J.; Chande, R.; Kondracki, A.; Reddick, B.; Davis, A.; Athan, A.; Buoli, M.; Barkin, J.L. Mental health impacts of climate change and extreme weather events on mothers. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2024, 15, 2296818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelhas, I.; Gast, M. “I Owe It to My Daughter”: How Parents Deal with the Climate Crisis. Psychodynamic Interviews with Parents Committed to Climate Protection. Psychoanal. Study Child 2024, 77, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Mayerson, M.; Leong, K.L. Eco-reproductive concerns in the age of climate change. Clim. Change 2020, 163, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Mayerson, M. The environmental politics of reproductive choices in the age of climate change. Environ. Politics 2022, 31, 152–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severo, A.F.F. Parenting and Climate Change: What are Parents’ Perceived Roles and Worries? Master’s Thesis, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal, 2023. Available online: https://repositorium.sdum.uminho.pt/bitstream/1822/85923/1/Ana%20Flavia%20Franco%20Severo.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Szalma, I.; Szczuka, B.J. Reproductive Choices and Climate Change in a Pronatalist Context. East Eur. Politics Soc. 2024, 08883254241229728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, I.; Martin, A.; Wicker, A.; Benoit, L. Understanding youths’ concerns about climate change: A binational qualitative study of ecological burden and resilience. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Global Warming’s Six Americas. Available online: https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/about/projects/global-warmings-six-americas/ (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Hadré, E.; Küpper, J.; Tschirschwitz, J.; Mengert, M.; Labuhn, I. Quantifying generational and geographical inequality of climate change. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiery, W.; Lange, S.; Rogelj, J.; Schleussner, C.-F.; Gudmundsson, L.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Andrijevic, M.; Frieler, K.; Emanuel, K.; Geiger, T.; et al. Intergenerational inequities in exposure to climate extremes. Science 2021, 374, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Victoria, C.; Elicia, B.; Louise, D.; and McEvoy, C. The online survey as a qualitative research tool. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2021, 24, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspers, P.; Corte, U. What is Qualitative in Qualitative Research. Qual. Sociol. 2019, 42, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, H. The logic of qualitative survey research and its position in the field of social research methods. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2010, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K. The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2005; Volume 1, p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Percentage of Adults Who Perceive Climate Change as a Major Threat in OECD Countries, 2020; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-skills-outlook-2023_27452f29-en.html (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Jakučionytė-Skodienė, M.; Liobikienė, G. The Changes in Climate Change Concern, Responsibility Assumption and Impact on Climate-friendly Behaviour in EU from the Paris Agreement Until 2019. Environ. Manag. 2022, 69, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample | Any sample of parents (mothers/fathers/both) or grandparents or expectant parents in OECD country. | Any sample not composed, in whole or part, of parents, grandparents, and/or expectant parents. Samples recruited in non-OECD countries. |

| Phenomenon of Interest | Attitudes, experiences, or opinions to climate change and global warming. | Attitudes, experiences, or opinions on specific actions (e.g., recycling, transport, energy use) and/or other environmental issues. |

| Design | Any qualitative data collection methods (e.g., interviews, observations, or focus groups). | Quantitative research (e.g., fixed-response surveys). |

| Evaluation | Any information on attitudes, experiences, or opinions of parents; may be the primary or secondary focus of the study. | Information on health impact or behaviour. |

| Research type | Qualitative or mixed methods (e.g., combining fixed and open-ended responses). | Quantitative research and non-empirical research (e.g., commentaries, editorials, letters). |

| Year of Publication (n = 22) | Count (%) |

| 2000–2004 | 0 (0%) |

| 2005–2009 | 0 (0%) |

| 2010–2014 | 0 (0%) |

| 2015–2019 | 2 (9%) |

| 2020–2024 | 20 (91%) |

| Countries (n = 19 *) | Count (%) |

| United States | 7 (37%) |

| Australia | 4 (21%) |

| United Kingdom | 3 (16%) |

| Canada | 2 (11%) |

| Nordic countries (Finland, Norway, Sweden) | 1 each (5%) |

| Switzerland, Belgium, Hungary, Netherlands, Turkiye, France | 1 each (5%) |

| Qualitative Data Collection Method/s (n = 19) | Count (%) |

| Interviews | 10 (53%) |

| Focus groups | 3 (16%) |

| Open-ended questions/free-text responses in quantitative survey | 6 (32%) |

| Diary entries | 1 (5%) |

| Testimonials | 2 (11%) |

| # | Author, Year, Form of Output | Country | Aims | Study Methods | Population | Recruitment Methods | Sample Size (n) | Participant Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baker, et al. [31] (journal article) | Australia | To explore ‘caretaker perceptions of children’s climate change emotions, and the needs and challenges of supporting children’ (p687) | Quantitative survey with open-ended questions | Those with caring responsibilities for school-aged children (parents and teachers) | Online survey posted to Australian Facebook groups | 141 | Majority were parents. Parents had children aged 1–17 years and all lived in Australia. |

| 2 | Boddy, et al. [32] (journal article) | UK, India | To provide a ‘narrative analysis of family practices’ relating to environmentalism and climate change (p359) | Visits and interviews | Affluent parents in England and India | Recruited via schools | Parents in 10 families | Four of the ten families had children attending private/fee-paying schools. |

| 3 | Bodin and Björklund [33] (journal article) | Sweden | To explore ‘how people of different ages discuss and justify their stance concerning reproduction in relation to their knowledge about climate change and overpopulation’ (p2) | Age-specific focus groups | People living in Skåne County, Sweden. | Recruited through social media, university website, and author networks | 98 | Aged 17–90; the majority identified as women. ’An overrepresentation of white, heterosexual, middle class women’ (p2). |

| 4 | Gaziulusoy [34] (journal article) | Finland, Australia, Turkiye, USA, Nether-lands | To capture ‘the lived experiences of parents raising children during climate change’ (p1) | Interviews with open-ended questions | Parents aware of climate change and implications for their children | Invitation through online and offline social networks | 12 | Gender: 8 women, 4 men. Parents aged 36–46; 8 women, 4 men. No information on socio-economic background or ethnic identity. |

| 5 | Hirschberg [35] (undergraduate dissertation) | USA | To fill the gap in knowledge on the perspectives of parents of children aged 12–17 on climate grief | Interviews with open-ended questions | Parents aged 30 and over with an adolescent child experiencing emotional distress about climate change | Recruitment via organisational contacts, and author networks | 8 parents and 8 children | 7 female, 1 male parent participants; majority white. All had at least a Bachelor degree and professional backgrounds relating to environmental sciences. |

| 6 | Holmes, et al. [36] (journal article) | USA | ‘To explore the emotionally reflexive processes by which some women build maternal futures in the unsettling context of climate change’ (p357) | Online testimonies | Women providing personal testimonies on a woman-led network focusing on reproductive justice and climate change | Testimonies provided in response to researcher’s invitation and house parties hosted by network members | 67 | Largest group were women aged 20–29 without children. No information on socio-economic background or ethnic identity. |

| 7 * | Howard, et al. [37] (journal article) | UK | ‘To explore the emotional spaces of parenting and campaigning for inter-generational climate justice’ (p1429) | Semi-structured qualitative diary + semi-structured interview | UK-based activist mothers and fathers | Recruitment via social media and snowballing | 20 | 12 mothers; 8 fathers. No further information provided. |

| 8 * | Howard [38] (journal article) | UK | ‘To investigate the overlapping emotional spaces of climate activism and parenting’ (p1) | Qualitative diary entries and interviews | Parents/guardians worried about climate change and impact on their children and involved in climate change campaigning | Recruitment via social media and snowballing | 20 | 12 mothers; 8 fathers. ’Participants were mainly middle class, possessing a tertiary level education and a medium to high household income. All but one participant were White’. |

| 9 * | Howard [39] (doctoral thesis) | UK | To address ‘knowledge gaps in the ways action on the climate “crisis” is mobilised in the context of family and personal relationships’ (p3) | Interviews; diary entries | Parents engaged in any type of organised, shared campaigning to address climate change | Recruitment via social media and climate parent groups | 20 | 12 mothers; 8 fathers. |

| 10 | Jurcik [40] (Masters dissertation) | Canada | To explore ‘the impact of climate change on individuals considering parenthood and the complexities of becoming a parent during the current climate crisis’ (piii) | Semi-structured interviews | Participants who identified as being of childbearing age, years/the gestational parent and considering climate change deciding about parenthood | Recruitment via social media to climate change groups and influencers known to the researcher | 20 | Majority did not have children/stepchildren; had a Bachelor degree or higher, identified as white, did not identify as First Nation. |

| 11 | Léger-Goodes, et al. [41] (journal article) | Canada | To ‘gain insight into the ways in which children experience eco-anxiety’ (p2) and how parents understand their child’s lived experiences and help them cope with their concerns | Survey with free text response | Parents of children aged 8–12 years | Recruitment via organisations working with families and via pro-environmental organisations | 12 | The majority identified as women and as White Canadian. No information provided on educational status/ family socio-economic circumstances. |

| 12 | Lykins, et al. [42] journal article) | Australia | ‘To assess the contribution of climate change anxiety to antenatal worry and depression’ (p3) | Survey with open-ended questions | Women who identified as female and were currently pregnant | Recruitment via expectant parent social media networking sites | 49 participants responded to open-ended questions | No socio-demographic information on participants. |

| 13 | Madden, et al. [43] (journal article) | USA | To understand parental perspectives on climate change education standards introduced into schools in New Jersey, USA | Quantitative survey with open-ended questions and free text option at the end of survey | Parents of children attending public (state) schools | Recruitment via social media and emails using professional listservs | 83 | No parental socio-demographic data on participants. |

| 14 | Munro [44] (journal article) | USA, Belgium, Switzerland | To critically analyse testimonials by parents and grandparents engaged in environmental advocacy organisations | Mission statements and testimonials | Web-based testimonials from environmental advocacy organisations | Recruitment via environmental advocacy organisations | 40 testimonials | Testimonial writers were ‘primarily white, middle-class women exclusively living in the Global North’, the majority from US-based organisations. |

| 15 | Nakkerud [45] (journal article) | Norway | To explore ‘the psychological and social processes surrounding choices to be environmentally childfree’ (p200) | Semi-structured interviews | People wanting to have no children or only have child because of environmental concerns | Recruitment social media or direct invite | 20 | Majority identified as women with no children. No information on socio-economic background or ethnic identity. |

| 16 | Pardon, et al. [46] (journal article) | Australia | ‘To explore the negative mental health consequences of climate change and/or extreme weather events as reported by new Australian mothers’ (p3) | Focus groups | Mothers aged ≥ 18 years and with baby ≤ 12 months | Recruitment via social media and university networks | 31 | 14 participants had two or more children. No other socio-demographic information. |

| 17 | Schelhas and Gast [47] (journal article) | Germany | To focus on ‘parents who are actively engaged in climate protection […] to find out how they deal with the climate crisis against the backdrop of their own parenting and concern for the future of their children’ (p402) | Interviews | Parents engaged in ’climate protection’ | Recruitment via parents engaged in climate activism groups | 4 | 3 mothers; 1 father. No further information provided. |

| 18 ** | Schneider-Mayerson and Leong [48] (journal article) | USA | To fill the gap in scholarship ‘on the relationship between climate change and individual reproduction intentions and practices’ (p1009) | Survey with open-ended questions | Young people factoring climate change into reproductive decision-making | Link to survey posted via climate thinkers, activists, and organisations | 607 | Majority identified as female, non-parents white, very liberal with a Bachelor degree or higher. |

| 19 ** | Schneider-Mayerson [49] (journal article) | USA | ‘To explore the nexus between reproductive choices and environmental politics in relation to climate change’ (p153) | Survey (with free text response) | Climate ‘leftists’ factoring climate change into reproductive decision-making | Link to survey posted via climate thinkers, activists, and organisations | 607 | Majority identified as female, non-parents white, very liberal with a Bachelor’s degree or higher. |

| 20 | Severo [50] (Masters dissertation) | Portugal | To explore parents’ perceptions of their roles and worries with respect to parenting and climate change | Interviews | Parents of children aged 10–14 years | Recruitment face-to-face and online dissemination in a school close to the university | 29 | Majority had completed higher education; 40% of families eligible for free/reduced prices school lunches for their children. |

| 21 | Szalma and Szczuka [51] (journal article) | Hungary | To better understand ‘how individuals make decisions about childbearing according to their views on climate change and how they rationalise their choices in a pronatalist country’ (p1) | Semi-structured interviews | Childless and single-child women between 18 and 45 years | Initial recruitment via social networks and snowball sampling | 44 | 21 had no children; 21 had one child; 2 were pregnant; 25 had a higher degree. |

| 22 | Thomas, et al. [52] (journal article) | USA, France | A small number of parents included in a study of ‘young people’s views about climate change’ (p1) | Focus groups | Parents of children aged under 10 | Recruitment via social media platforms | 12 | Parents had children under 10 years; no other data provided. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Graham, H.; Lampard, P.; Golder, S. A Review of Qualitative Studies of Parents’ Perspectives on Climate Change. Societies 2025, 15, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040104

Graham H, Lampard P, Golder S. A Review of Qualitative Studies of Parents’ Perspectives on Climate Change. Societies. 2025; 15(4):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040104

Chicago/Turabian StyleGraham, Hilary, Pete Lampard, and Su Golder. 2025. "A Review of Qualitative Studies of Parents’ Perspectives on Climate Change" Societies 15, no. 4: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040104

APA StyleGraham, H., Lampard, P., & Golder, S. (2025). A Review of Qualitative Studies of Parents’ Perspectives on Climate Change. Societies, 15(4), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040104