Abstract

This participatory action research (PAR) study explored the diversity and cultural competencies essential for working effectively and appropriately with diverse patients in healthcare and healthcare education. Ninety-four (94) medical students participated in two PAR cycles, engaging in brainstorming, group exercises, collaborative work, discussions, reflections, and role-plays. Together, they addressed the central question regarding the diversity and cultural competencies that are necessary for working effectively with diverse patients in healthcare. Participants identified eight core competencies, namely open-mindedness, empathy and cultural empathy, deep listening, explore further, knowledge, self-reflection, work in partnership, and praise the patient. They also ranked these competencies and explained their significance in healthcare settings. Based on participants’ explanations, a thematic network was developed, illustrating how these competencies interrelate. The analysis highlighted that these competencies must function together to foster a deeper understanding of patients, ultimately contributing to improved health outcomes. This interrelationship is represented in the Wheel Model proposed in the study, showing that empathy and cultural empathy sit at the center of the wheel, supported and reinforced by the other competencies all of which interact to enable the wheel to roll smoothly. Interestingly, the driving force seems to be the competency “open mindedness” as it puts most of the rest competencies in motion. The study also revealed that participants came to appreciate the importance of these competencies gradually, particularly after engaging in specific diversity-related activities and completing the two PAR cycles. This finding highlights that prior experience or knowledge alone might be insufficient for working effectively with diversity, underscoring the need for lifelong training, continuous learning, and the accumulation of relevant experience. In the absence of other PAR on diversity and cultural competencies in healthcare and healthcare education, the findings of this study both align with and diverge from those of Delphi studies, offering new directions for future research.

1. Introduction

Cultural competence in healthcare has been acknowledged as essential for providing high-quality care that respects patients’ cultural backgrounds. Broadly, it refers to the knowledge and skills related to the social and cultural determinants of health and illness, as well as the actions taken by healthcare professionals or organizations to ensure the best possible care [1]. Cultural competence has been linked to improved patient satisfaction, adherence to therapy, and health outcomes [2,3,4,5]. International guidelines for doctors and medical students also highlight the importance of cultural competence in healthcare settings. For instance, to work professionally with both patients and colleagues the GMC’s (General Medical Council) “Good Medical Practice” [6] stresses the need for doctors to be aware of their own biases, understand how their culture and beliefs affect their professional relationships, show respect and sensitivity towards others’ cultures and beliefs, and avoid discrimination or abuse based on individual characteristics or background. Similarly, the AAMC’s (Association of American Medical Colleges) “The Core Competencies of Entering Medical Students” [7] includes cultural competence among the fifteen core professional competencies. In this paper, we approach ‘cultural competence’ as an umbrella term consisting of specific competencies which are sets of skills, knowledge and behaviors, along the lines of how the term is used by GMC (General Medical Council) [6].

Several models attempted to identify the specific competencies that make up cultural competence. Specifically, the LIVE & LEARN model encompasses a range of competencies, including listening, evaluating, acknowledging, recommending, and negotiating [8]. Leininger’s Sunrise Model [9] emphasizes the importance of healthcare professionals considering a broad spectrum of cultural influences, such as values, religious and philosophical beliefs, economic conditions, educational backgrounds, political and legal systems, technological factors, kinship and social relationships. The Purnell Model, by contrast, presents an extensive compilation of knowledge areas, covering topics such as high-risk behaviors, family roles, heritage, and modes of communication [10]. In a comprehensive literature review, Alizadeh and Chavan [2] identified 18 models of cultural competence. Except for one model developed through the Delphi method, the remainder were derived from literature-based analyses. These models collectively highlight key competencies, including awareness, understanding, compassion, sensitivity, appreciation of diversity, attitudes, openness, communication abilities, self-awareness, contextual understanding, intercultural engagement, and cultural intelligence.

Empirically, cultural competencies have been identified in several studies, including Delphi studies involving experts in the field [11,12]. Hordijk et al. [11], for example, recruited 34 professionals—including medical doctors, nurses, social scientists, educational specialists, and psychologists with experience in cultural competence—to identify the most effective competencies. These included self-reflection, effective communication, empathy, awareness of intersectionality and ethnic backgrounds, and knowledge of social determinants of health. Mohammadpour et al. [13], in a study involving 10 experts, concluded that the most relevant competencies are related to cultural attitude, cultural desire, cultural humility, humanistic competence, and readiness for education. Similarly, Montecinos and Grünfelder [14] drew on insights from 47 experts and identified the following competencies: cultural awareness, open-mindedness, active listening, critical self-reflection, being non-judgmental, respect, sharing experiences, and flexibility. Chae et al. [15] organized competencies into four categories: awareness (e.g., culture, diversity, self-awareness), knowledge (e.g., health-related cultural differences), attitude (e.g., acceptance), and skills (e.g., effective communication, building trust). A similar framework was adopted by Ojanen et al. [16], who grouped competencies into knowledge and awareness, skills, and action (e.g., showing respect). Johansson et al. [17] also emphasized knowledge of other cultures and self-reflection. Meanwhile, Castro, Dahlin-Ivanoff and Mårtensson [18] highlighted the importance of understanding gender and social vulnerability, while Farokhzadian et al. [19] stressed curiosity, empathy, and shared decision-making. By the same token, Franzen et al. [20], working with 12 experts across European countries, identified competencies such as understanding patients’ views—including social roles, rules, religion, and traditions—working with interpreters, being flexible and patient, and engaging in self-reflection. Jervelund et al.’s [21] study of nine experts in Denmark added competencies such as interpreting services, health promotion, equality, and co-created healthcare policies with minority communities.

Earlier studies did not identify fundamentally different competencies. For example, Jirwe et al. [12] focused on cultural sensitivity, understanding, intercultural encounters, and knowledge of health, illness, and healthcare. Hart et al. [22] emphasized understanding patients’ cultural beliefs and practices. Notably, although Deardorff’s [23] study of 23 U.S.-based experts did not identify unique competencies for working with diverse patients, it highlighted ‘cultural empathy’ as a core generic skill when working with any patient.

Interestingly, the literature on cultural competence has focused predominantly on ethnicity and cultural background, often overlooking other forms of difference such as gender identity, age, health literacy, sexual orientation, disability, and socio-economic status. In this regard, the term ‘diversity competence’ captures a broader range of differences and refers to the set of knowledge and skills necessary for working appropriately and effectively with patients from diverse backgrounds—including ethnicity, culture, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation, age, socio-economic background, education, disability, and more. Ziegler, Michaëlis and Sørensen [24] conducted a Delphi study to identify the diversity competencies needed by healthcare professionals to improve the quality of care. Some of the important competencies that the experts identified were: respectfulness, communicating understandably, self-reflection, working with interpreters, empathy, open-mindedness, etc. Taking into account both cultural and diversity competencies, Constantinou and Nikitara [25] reviewed Delphi studies that focused on healthcare and proposed a set of overarching competencies summarized by the acronym RESPECT. These included: Reflect, Educate, Show interest and Praise, Empathy, and Collaborate for Treatment.

Although cultural and diversity competencies have been widely studied through expert input in Delphi studies or through professionals working with diverse populations, there is limited knowledge about the competencies that can emerge from active participation by individuals with some, but not expert-level, experience—such as medical students, practicing healthcare professionals, junior doctors or doctors with no relevant expertise. Therefore, the aim of this study is to identify the core cultural and diversity competencies as generated by medical students themselves through Participatory Action Research (PAR). In other words, medical students will not only articulate competencies based on their prior experiences, but will also develop them in a dynamic and diverse environment. This study aims to address the following questions: (a) What diversity and cultural competencies do medical students consider necessary for ensuring high-quality healthcare for different patients? (b) How are these diversity and cultural competencies shaped by an active learning environment?

2. Methodology

2.1. Participatory Action Research (PAR)

For this study, we employed the methodology of Participatory Action Research (PAR), following the guidelines outlined by Cornish et al. [26]. According to Cornish et al., “Participatory action research (PAR) is an approach to research that prioritizes the value of experiential knowledge for tackling problems caused by unequal and harmful social systems, and for envisioning and implementing alternatives.” In other words, PAR is a research approach in which participants actively contribute to the process by collecting data and offering solutions or suggestions based on their personal experiences. The aim of PAR is to bring together community members to generate knowledge and drive change.

PAR involves a cyclical process that is repeated until the identified problem is addressed. Specifically, the PAR cycle consists of four steps: define the problem, take action, observe, and reflect. “Define the problem” refers to participants working collaboratively to identify the issue that needs to be addressed. This is followed by taking “action,” then “observing” and collecting information based on the outcomes of those actions, and finally “reflecting” to understand what was learned and what further developments are needed. These steps are iterative, and the cycle continues with a “redefinition” of the problem, followed by additional “actions,” further “observation,” and more “reflection” until the issue is fully resolved.

Through these repeated cycles, teamwork is strengthened as participants engage in what Cornish et al. [26] refer to as the six building blocks of PAR. These are: building relationships, establishing working practices, developing a shared understanding of the issue, observing, gathering and generating materials, conducting collaborative work, and planning and taking action. For the purposes of this study, the PAR cycle was repeated twice. Participants enhanced their teamwork through activities such as brainstorming, group exercises, collaborative work, discussions, reflections, and role-play. Further details are provided in Section 2.3.

2.2. Sampling and Recruitment

Year 4 medical students from a 6-year medical degree program at the University of Nicosia Medical School in Cyprus were invited to participate in this study. We focused on Year 4 students specifically because they had already received some training in cultural competence through their curriculum in previous years and had just begun their clinical training. At this stage, they had limited practical experience working with socially and culturally diverse patients in healthcare settings. Ninety-four (94) out of 180 eligible students agreed to participate, who were then divided into groups of 6–7 and worked with a trained facilitator. Facilitators were trained during one-hour session before the start of the study, and all had the same facilitator guide that they had to implement during the study. The study was reviewed and approved by the Cyprus National Bioethics Committee (ΕΕΒΚ ΕΠ 2024.01.296). Participants were informed about the study and were invited to sign an informed consent form. All data was anonymized and treated confidentially as per the GDPR law.

2.3. Procedure of Data Collection

Participants engaged in diversity and cultural competence activities as part of their involvement in the study. Following the four steps of the PAR cycle, as previously described, participants were initially asked—drawing from their personal experiences and prior knowledge—to consider how healthcare professionals should work with diversity in clinical settings. They concluded that the first step was to identify the skills and behaviors required for healthcare professionals to work effectively and appropriately with diverse populations. In doing so, they “defined the problem.”

Next, they created an initial list of relevant skills and behaviors, which they would revisit after taking further action. The first “action” involved a group exercise to share their prior experiences with diversity. Through this exercise, they began to “observe” and practice key diversity competencies, such as listening to understand, valuing team members’ contributions, collaborating, and showing respect and curiosity toward one another’s perspectives. After completing this exercise, the final step of the first cycle was to “reflect” on the initial question that defined the problem and related to essential skills and behaviors for working with diversity. The goal was to expand their list based on insights gained from the exercise. While completing this first cycle, they naturally transitioned into the second cycle, as the central question about necessary skills remained open.

The second cycle involved additional “action.” Participants watched several short videos on diversity at their own time, and a week later, they worked in their small groups to discuss scenarios and agree on responses. These scenarios were designed to prompt reflection and help them “observe” additional competencies relevant to working effectively with diverse populations. Participants took further action by applying the identified skills and competencies in a role-play activity involving trained simulated patients. Simulated patients were trained for their participation in the study, and they all received the same scenario in advance to practice, followed by briefing on the day of the role play. Participants’ engagement with role-play allowed them to “observe” and experience more diversity-related competencies, followed by a final “reflection” on the knowledge and skills required for effective and appropriate care. As in the first cycle, the objective was for participants to use what they had found meaningful from the videos, group discussions, and role-play exercises to refine and complete their list of necessary skills and behaviors. Having exhausted their list, the PAR cycles closed by reaching group consensus and agreed on a comprehensive list of necessary diversity and cultural competencies for working effectively with diverse patients.

The process of completing the two par cycles was done by each student’s group separately. These comprehensive lists were then consolidated into core competencies. Finally, after the completion of the two PAR cycles, each participant was invited via email to identify the three most important competencies and provide a justification for their choices by writing their explanations in a Google Form. The whole procedure of data collection, including the two PAR cycles, was completed over a period of three weeks.

To address any potential biases, we applied a process of standardization of facilitators. As mentioned earlier, all facilitators were trained and briefed before data collection began. In addition, they were provided with a detailed plan regarding how to facilitate and how to take notes on the flip chart. Finally, three of the researchers moved among all groups to ensure that the instructions were applied properly and the research process ran smoothly.

2.4. Coding and Analysis

During the two PAR cycles, data were recorded on flip charts by the facilitator of each group on three occasions: during the ‘brainstorming’ prompt before students engaged with any diversity activities; during the ‘reflection’ prompt after students had completed the group exercise of sharing experiences; and during the ‘agreed’ prompt following the videos and students’ involvement in group work and role play. As part of their training, facilitators had to record the exact words of the participants without any interpretations. More data was collected after the two PAR cycles were completed by inviting students to select and justify the three most important competencies.

For the analysis, we employed the ‘Framework Method’ as outlined by Ritchie and Spencer [27]. This involved familiarizing ourselves with the data through multiple readings and note-taking, constructing themes, identifying which data corresponded to each theme, creating charts, and then mapping and interpreting the data. For the construction of themes, we used Braun and Clarke’s [28] process of thematic analysis and their guidelines regarding themes, which refer to grouping codes that could make an overarching theme. Through this process of coding and thematic development, the core diversity and cultural competencies were generated.

After participants selected and justified their three most important competencies, we first quantified their selections. We then returned to the Framework Method to closely examine the data, coding participants’ responses and identifying thematic patterns. In this phase, we also looked for interconnections and constructed themes following Attride-Stirling’s [29] “Thematic Network” approach.

To ensure the rigor of our study, we employed a thorough internal process of quality assurance. The first two authors were more involved in data collection and coding. The initial coding and analysis were undertaken by the first author, while the second author independently reviewed both the codes and the analysis, leading to adjustments where necessary. An additional quality assurance process was conducted by the third and fourth authors, who reviewed all results and analyses separately before refining the study’s analysis and outcomes.

3. Results

The analysis procedure described above resulted in four sections presenting the results. It is imperative to briefly introduce these sections here. (1) Identifying the diversity and cultural competence. We achieved this by grouping participants’ suggestions regarding what they considered the necessary skills and behaviors during the initial ‘brainstorming’ prompt, during the ‘reflection’ prompt, and during the ‘agreed’ prompt. (2) Ranking the diversity and cultural competencies. Following the completion of the two PAR cycles and the identification of competencies, we measured how many times each core diversity and cultural competency was selected by participants. (3) Justifying the diversity and cultural competencies. By coding the participants’ selections, we described the reasons behind their choices. (4) Connecting the diversity and cultural competencies. After explaining participants’ selection of competencies, we looked for any connections between them as revealed in participants’ justifications.

These four sections are analysed below and fully address the question about the necessary diversity and cultural competencies in healthcare that this PAR study aimed to explore.

3.1. Identifying the Diversity and Cultural Competencies

To identify the diversity and cultural competencies, 94 medical students responded to the question regarding the necessary skills and behaviors for working effectively with diverse patients. As described in Section 2 of this paper, during the “brainstorming” prompt, students reflected on these skills and behaviors based on their prior experiences and knowledge. During the “reflection” prompt, students were asked to draw not only from their existing knowledge and experiences but also from the group exercise they had just completed. For the “agreed” prompt, students were invited to consider the videos they had watched, their group work on short scenarios, and the role-play activity with simulated patients.

The findings indicated that during the “brainstorming” prompt, students identified 128 behaviors or skills. During the “reflection” and “agreed” prompts, students generated 118 and 99 behaviors or skills, respectively. In total, students mentioned 345 behaviors or skills. Many of these were repeated by different students, while some students contributed multiple responses. Examples include: be open-minded, listen, avoid stereotyping, show empathy, be patient, be flexible, etc.

The 345 behaviors or skills were treated as codes because, on the flip charts, they appeared as keywords or short sentences and could not be simplified further. Subsequently, we grouped these codes to form overarching themes, as per the guidelines by Braun and Clarke [28]. Following the GMC’s (General Medical Council) [6] approach to ‘competence’, these themes were considered competencies, as they combined interrelated behaviors, skills, and knowledge. Thereafter, through the coding process, we generated eight themes or core competencies, namely:

- (1)

- Be open-minded, non-judgmental and make no assumptions or stereotypes (this competency also includes behaviors such as picking up cues, body language, patience, and being flexible).

- (2)

- Show empathy and cultural empathy (i.e., understand and show understanding of the patient’s feelings, cultural beliefs and perspective).

- (3)

- Engage in active and deep listening (i.e., attentive listening for in-depth understanding of the patient’s perspective).

- (4)

- Self-reflect to identify and tackle own biases and microaggressions.

- (5)

- Explore further to show interest, give value, and learn about the patient’s beliefs, perspective and social history.

- (6)

- Praise the patient (i.e., appreciate the patient’s willingness to share their beliefs or perspective) to give value to their beliefs or perspective.

- (7)

- Work in partnership with the patient (shared-decision making).

- (8)

- Knowledge in how culture (including religion), socioeconomic background, and lifestyle affect patients’ health, illness, and illness management.

Having identified all core diversity and cultural competencies generated by the medical students throughout the various stages of the research, we then revisited the PAR cycles to examine which competencies were mentioned during each prompt. This was done by classifying the behaviors or skills from each prompt under the relevant competency. For example, behaviors or skills from the “brainstorming” prompt, such as ‘open-minded’, ‘avoid stereotypes’, and ‘be flexible’, were grouped under Competency 1 ‘Be open-minded’. Similarly, behaviors or skills from the “reflection” prompt, like ‘explore if you do not know’ and ‘explore, show interest’, were counted under Competency 5 ‘Explore further’.

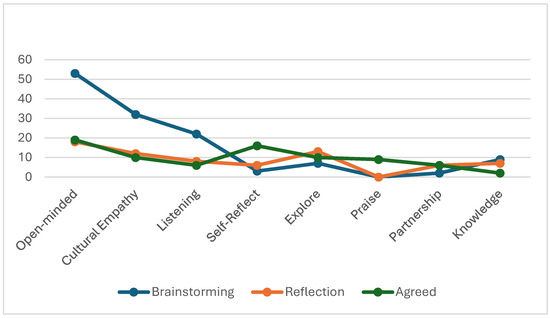

This process revealed some interesting findings. As shown in Table 1, only Competencies 1 (53 mentions), 2 (32 mentions), and 3 (22 mentions) were strongly emphasized by students during the “brainstorming” prompt. As a reminder, during brainstorming, students were asked to identify the necessary behaviors or skills based on their prior experiences and knowledge, before participating in any diversity-related activities. Competency 4 was mentioned three times, Competency 5 seven times, Competency 6 not at all, Competency 7 twice, and Competency 8 nine times.

Table 1.

Competencies mentioned per prompt.

The pattern shifted during the “reflection” prompt, after students had completed the exercise of sharing their experiences with diversity. While Competencies 1, 2, and 3 continued to be valued, students increasingly referred to Competencies 4 (six mentions), 5 (13 mentions), and 7 (six mentions). Competency 8 (Knowledge) remained relatively stable with seven mentions. Competency 6 (‘Praise the patient’) still received no mentions.

In the “agreed” prompt, after students had engaged in group work on short scenarios and participated in role-play with simulated patients, greater emphasis was placed on Competencies 4 (16 mentions), 5 (10 mentions), and 6 (nine mentions), while the importance of the other competencies was maintained. Figure 1 illustrates the trajectory of each competency across the three prompts based on the times each competency was mentioned.

Figure 1.

Trajectory of competencies per prompt.

Conclusively, the findings revealed that the core competencies identified as important for working with diverse patients evolved across the three prompts, suggesting that students recognized the value of specific competencies only after engaging in particular diversity activities.

3.2. Ranking the Diversity and Cultural Competencies

Having identified the eight diversity and cultural competencies necessary for working effectively with diverse patients, as well as their progression across the prompts, students were then invited to select the three competencies they considered most important and justify their choices. Fifty-six (56) students responded to this invitation, ranked the competencies, and provided feedback.

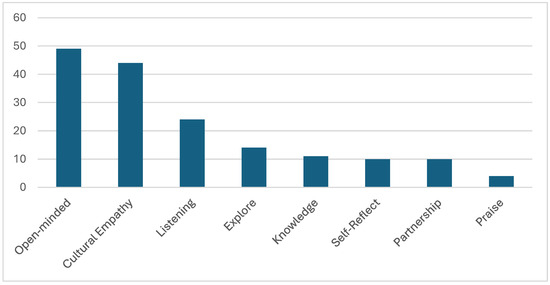

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 2, ‘Be open-minded’, ‘Empathy and cultural empathy’, and ‘Deep listening’ were selected as the most important competencies, reflecting the students’ responses during the “brainstorming” prompt and prior to engaging in the diversity activities. Then the most important competencies were ‘Explore further’, ‘Knowledge’, ‘Self-reflect’, ‘Work in partnership’, and ‘Praise the patient’.

Table 2.

All competencies ranked by medical students.

Figure 2.

All competencies ranked by medical students.

3.3. Justifying the Diversity and Cultural Competencies

Medical students explained why they believed the three competencies they selected were important. We coded their responses, generated overarching explanations, and included specific quotes from students’ own words. To avoid confusion, the competencies below are presented in the order ranked by medical students, as shown in Table 2 above.

3.3.1. Be Open-Minded, Non-Judgmental and Make No Assumptions or Stereotypes

Medical students considered being open-minded, non-judgmental, and avoiding assumptions or stereotypes crucial in healthcare, as they fostered a safe, inclusive, and respectful environment where patients felt genuinely heard and valued—regardless of their background. They believed this approach helped build trust and rapport, which were essential for a strong doctor–patient relationship. Students explained that when patients felt comfortable and understood, they were more likely to share their experiences, enabling accurate assessments and more effective communication. Such openness allowed healthcare professionals to tailor care to individual needs, improving treatment adherence and overall outcomes. Approaching patients without judgment also encouraged continuous learning—about the patient, their context, and even the clinician’s own biases or microaggressions. As one student stated: “It is impossible to know everything about every culture, therefore being open-minded and collaborating with the patient are the most important to be culturally competent.”

It is evident from students’ explanations that open-mindedness promotes empathy and active listening. According to students, being open-minded not only strengthens connections between doctors and patients but also enhances cultural sensitivity, enabling providers to adapt to diverse populations and deliver equitable care. This mindset signals to patients that their stories matter and that the doctor is genuinely there for them, creating an atmosphere of mutual respect, understanding, and partnership. Reflecting this, a student noted: “Being non-judgmental and open-minded with patients allows them to feel comfortable sharing their ideas, thoughts, and concerns which can lead to the correct diagnosis and better patient adherence.” Another student added: “We should approach our patients like an open book, ready to learn from zero.”

3.3.2. Showing Empathy and Cultural Empathy

Students identified showing empathy and cultural empathy as essential for working effectively with diverse patients. They believed this competency allowed healthcare professionals to understand the patient not just medically, but also emotionally and culturally. It helped create a safe, supportive environment where patients felt seen, valued, and comfortable sharing. Students explained that when patients sensed genuine care and understanding, they would be more likely to open up and share important details about their lives, beliefs, and symptoms.

Cultural empathy, in particular, helped healthcare providers recognize and respect culturally specific habits, beliefs, and values, enabling them to provide more personalized care. According to students, empathy builds rapport and trust, forming the foundation of a good doctor–patient relationship. Ultimately, both emotional and cultural empathy shows patients that they are important and their voices matter, leading to more respectful and effective healthcare. As one student explained, “Empathy is the key tool for a doctor to show caring and understanding to the patient.” Another emphasized, “We need to feel for people, understand their struggle, and validate their experiences.”

3.3.3. Engaging in Active and Deep Listening

Students viewed active and deep listening as a vital competency in healthcare, as it strengthened the doctor–patient relationship through genuine connection, trust, and understanding. They explained that when healthcare professionals truly listen—not only to words but also to non-verbal cues—they gain a fuller understanding of patients’ experiences and concerns. One student noted: “Deep listening helps you catch all the necessary information.” This approach enabled more personalized and effective care, fostering an inclusive, respectful environment where patients feel safe to open up. As another student stated: “Engaging in active deep listening is crucial to form a doctor-patient relationship. It helps build rapport and understand the patient better.” Students also emphasized that listening contributes to better health outcomes. One said, “[Listening to the patient] leads to more personalized and effective care,” while another highlighted that it helps providers adapt to diversity. Listening also complements other competencies like exploring further to gain deeper insights into the patient’s situation, as one student noted: “Exploring further adds to deep listening and shows interest in what the patient is saying.”

3.3.4. Exploring Further to Understand a Patient’s Beliefs, Perspective, and Social History

Students considered exploring further to understand a patient’s beliefs, perspectives, and social history critical for building a strong, trusting doctor–patient relationship. They asserted that when providers showed genuine interest in learning about the person behind the symptoms, it created a more inclusive, respectful environment.

This deeper exploration helped reduce misunderstandings by providing insight into the motivations behind a patient’s decisions, behaviors, and adherence. Students said:

“Actively seeking to understand a patient’s background fosters a stronger patient-provider relationship, reduces misunderstandings, and ensures culturally competent care.”

“By exploring and showing interest, the patient will entrust us with more information about their health, leading to correct diagnosis and therefore management. Their perspective is important as it could explain numerous behavioral aspects such as adhering to medication.”

“It’s important to further explore with the patient to show interest in what they’re saying and show that you are trying to help.”

These quotes illustrated that exploration was closely tied to other competencies like listening, praising, and valuing the patient. By appreciating a patient’s background, clinicians could offer more personalized care that respects the individual’s context and values. This promotes openness, strengthens communication, and enhances outcomes. As explained below, this competency was also closely linked with knowledge.

3.3.5. Having Knowledge of How Culture, Religion, Socioeconomic Background, and Lifestyle Affect a Patient’s Health, Illness Experience, and Illness Management

Students understood knowledge of how culture, religion, socioeconomic background, and lifestyle influence health and illness as crucial for effective care. They believed this understanding allowed providers to see the full picture of a patient’s context, thereby improving patient-centered care. Some students noted that openness to learning about diverse and marginalized communities helped providers grasp the unique struggles and values affecting health decisions. As one student explained: “We may not know anything about our patients, but we must be open to learning. Minorities have disproportionately been affected by systems set up only benefiting the rich white man.” Students also linked knowledge to empathy and understanding. For example:

“By having a well-rounded education and understanding of other cultures we can empathize with the patient.”

“Being aware of the cultural and socioeconomic background of a patient can help doctors understand the patient’s difficulties and struggles so that they can work together with the patient for a treatment plan that serves best to the patient’s needs.”

Such knowledge fosters deeper empathy, builds trust, and creates a safe environment where patients feel understood and valued.

3.3.6. Self-Reflection to Identify and Tackle One’s Own Biases and Microaggressions

Self-reflection to identify and tackle biases and microaggressions was viewed by medical students as essential for respectful, equitable healthcare. They explained that by becoming aware of their own biases, providers could reduce unintentional harm, understand their own perspective, improve their skills and ensure that all patients felt respected. One student stated: “Self-reflection should be a part of doctors’ everyday life because there are behaviors that we don’t notice but should.” This practice fostered a more supportive and trusting environment, allowing patients to share their experiences more openly. Reflecting on one’s own attitudes enhanced empathy, communication, and understanding. As one student noted: “Since being open-minded is very important when approaching different cultural aspects, being able to identify one’s own microaggressions and biases also helps to provide the best support to the patient.”

3.3.7. Working in Partnership with the Patient

Medical students saw working in partnership with the patient as vital for delivering respectful, effective, and patient-centered healthcare. As one student explained: “Have a better understanding of what’s the patient’s mindset around health, what he thinks is best for him, and how he wants to be treated.” They believed that involving patients as active participants fostered openness, led to more tailored care and helped patients better adhere to therapy. Another student highlighted: “Working in partnership is important to reach a treatment that a patient can conform to.” This collaboration strengthens rapport and trust, creates a safe environment and causes patients to feel comfortable opening up, and as a result, it helps doctors better understand their patients.

3.3.8. Praising the Patient to Give Value to Their Beliefs or Perspective

Interestingly, some medical students emphasized that praising the patient for sharing their experiences is a way to show appreciation, build a safe environment and rapport, causing the patient to feel included. One student offered a detailed perspective regarding the importance of praising the patient: “Remember, as doctors we have patients not cases. Yes, it is important to find out what’s the reason that the patient comes into your office, but you also have to build rapport and a good healthy relationship. You need to include them and talk with them, like you are supposed to do with your friends and family. They are humans with their own interests and own experiences that they might want to share. Giving them space to talk, showing how interested you are to hear more about them and their beliefs—patients get more comfortable to share with you even deeper thoughts later on.”

Echoing this quote, some students explained that valuing the patient’s perspective helped build empathy, trust, and a stronger doctor–patient connection. As one student put it: “Praising patients validates their perspectives, fostering respect.”, while another student concluded: “I believe that praising the patient is a quality that every doctor should have in order to build better rapport, as well as empathy and confidence.”

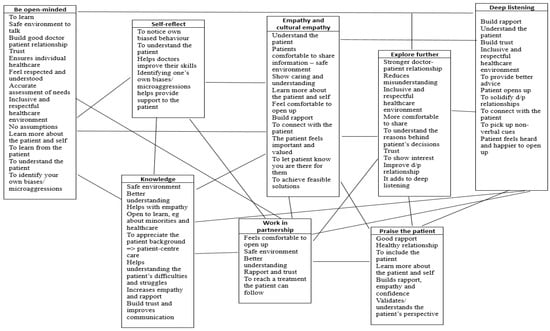

3.4. Connecting the Competencies in the Wheel Model

Following the guidelines by Attride-Stirling [29], we identified which codes and themes interconnected and constructed a thematic network (Figure 3). Our thematic network revealed that each competency centers on creating a connection between healthcare providers and patients. Overall, these competencies emphasize respect, understanding, and inclusivity as foundational principles for delivering care that is not only clinically sound but also emotionally and culturally appropriate. A key commonality across these competencies is the recognition of the patient as a social being, with an emphasis on understanding the individual’s values, beliefs, emotions, and lived experiences. These competencies promote safe, non-judgmental environments where patients feel comfortable sharing information, thereby building trust and rapport. This, in turn, is expected to lead to better communication, more accurate assessments, and improved adherence to treatment. Another shared theme is the importance of learning and reflection. In our thematic network, healthcare providers are not positioned as the sole authority but as collaborators who must remain open to learning from their patients. Whether reflecting on one’s own biases, exploring a patient’s social or cultural background, or actively listening to truly understand, the goal is continuous growth as practitioners to provide better, more inclusive care.

Figure 3.

Thematic network showing the links between codes and themes.

Beyond these overarching principles, our thematic network revealed three important patterns. First, the core diversity and cultural competencies identified are not isolated skills to be learned and practiced independently; rather, they are interconnected. For example, “Be open-minded” is directly linked with “Deep listening” because open-mindedness helps healthcare professionals pay closer attention to their patients. It is also linked with “Self-reflect,” as open-mindedness facilitates better understanding of oneself. “Explore further” links with “Deep listening”, “Praise the patient”, “Work in partnership”, etc. These links between competencies are detailed in Figure 3.

Second, “Be open-minded” appears to be the driving force behind most of the competencies. To elaborate, medical students explained that when healthcare professionals are open-minded, they are more eager to listen carefully, learn about their patients’ cultures and backgrounds as well as their own, self-reflect on their biases, work in partnership with patients, explore patients’ perspectives and beliefs further, and as a result, are more prepared to show genuine empathy.

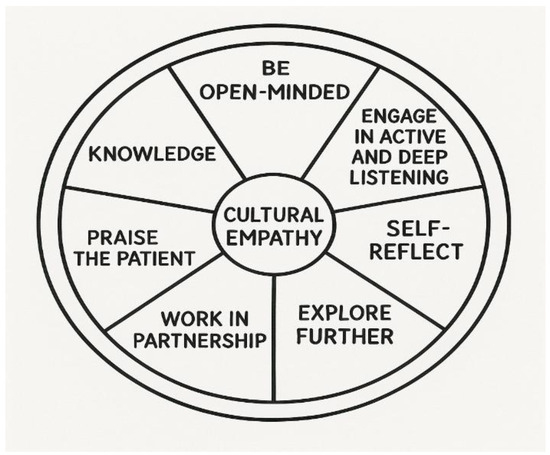

Third, “Empathy and cultural empathy” are woven throughout all the diversity and cultural competencies, as every competency supports understanding the patient. However, based on participants’ justifications, empathy and cultural empathy cannot stand alone—they are supported by all other competencies. In Figure 4, we propose the Wheel Model of diversity and cultural competencies, where empathy and cultural empathy occupy the center of the wheel, with all other competencies linked to the center and interwoven with each other. This central placement does not imply that empathy and cultural empathy are more important. In fact, as our thematic network shows, none of the eight competencies is more important than the others; all contribute to helping the doctor understand patients and, based on that understanding, work better with them. The Wheel Model emphasizes that all competencies together form a strong core—understanding or empathy—but to keep the wheel rolling, all competencies are needed and constantly interact with each other.

Figure 4.

The Wheel Model of diversity and cultural competencies.

4. Discussion

This study identified and explained the necessary diversity and cultural competencies derived within a PAR framework involving medical students. Through initial brainstorming and subsequent immersion in diversity activities, the medical students agreed that “Be open-minded,” “Empathy and cultural empathy,” “Deep listening,” “Explore further,” “Knowledge,” “Self-reflect,” “Partnership,” and “Praise” were essential competencies for working effectively and appropriately with diverse patients. To the best of our knowledge, no other PAR study in healthcare has focused specifically on diversity and cultural competencies. Therefore, we cannot directly compare our findings with those from similar studies.

However, diversity and cultural competencies have been generated in Delphi studies involving experts. Although the medical students in our study were not experts in working with diversity, the competencies they identified aligned closely with many of those found in Delphi studies. More specifically, our findings share similarities with Johansson et al. [17], who emphasized knowledge of other cultures and self-reflection, and with Hordijk et al. [11], who identified self-reflection, good communication, empathy, and knowledge as important competencies. Chae et al. [15] also highlighted communication as a key competency for working effectively with diversity. Interestingly, the medical students in our study did not list “good communication” as a general competency but emphasized the importance of rapport and a strong doctor–patient relationship, which could stem from competencies such as listening, exploring, and working in partnership. It appears that the medical students broke down communication into separate but interwoven components. Their focus on interconnected competencies that facilitate communication may reflect the teaching of communication skills delivered in this school, based on spiral learning of individual skills that underpin effective patient-centered communication. A similar breakdown of communication was observed in Montecinos and Grünfelder [14], who drew on input from 47 experts and identified competencies such as open-mindedness, active listening, self-reflection, and flexibility.

The competencies generated by the medical students were similar to those found in the Delphi study by Ziegler, Michaëlis, and Sørensen [24], whose experts gave the highest scores to competencies such as respectfulness, communicating understandably, identifying and addressing patient needs, self-reflection, non-discrimination, working with interpreters, finding solutions with patients, the ability to listen, empathy, avoiding generalizations, and open-mindedness. Ziegler, Michaëlis, and Sørensen explored diversity competencies broadly, not only cultural ones, giving their participants a wider frame of reference. Similarly, our study explored both diversity and cultural competencies. Furthermore, although “open-mindedness” was identified as a competency by experts in both Ziegler, Michaëlis, and Sørensen’s and Montecinos and Grünfelder’s studies, it was in our study that open-mindedness played a more important role—acting as a driving force that mobilizes the other competencies and facilitates reaching the desired level of empathy.

Other Delphi studies, such as those by Castro, Dahlin-Ivanoff, and Mårtensson [18] and Farokhzadian et al. [19], discussed knowledge, the importance of curiosity, empathy, and shared decision-making. Additionally, some studies emphasized knowledge of other cultures, health beliefs, and practices [12,20,21,22]. Interestingly, while many studies identified empathy as a key competency for working with diversity, only one Delphi study explicitly used the concept of “cultural empathy,” defined as showing understanding of the patient’s cultural beliefs, practices, and perspectives. In our study, medical students regarded cultural empathy as equally important as empathy. This likely resulted from their active participation in diversity activities, which prompted group discussions on culture and health beliefs, followed by interactions with simulated patients expressing their cultural views on health management. Thus, medical students recognized the distinct importance of showing empathy for a patient’s culture, separate from empathy for their feelings.

Unlike the studies outlined above, this PAR study directly indicated the relationships between competencies. This means diversity and cultural competencies should not be approached as a checklist of discrete skills to be learned and ticked off. All eight competencies generated in this study interrelate, support one another, and collectively contribute to the most critical goal: understanding the patient—how they think, feel, their cultural beliefs and practices, their reservations, and their knowledge. In support, Montecinos and Grünfelder’s [14] (p. 52) study highlighted the importance of commonalities and differences among competencies. Although they did not directly show the interconnection among these competencies, in their Delphi study, they stated that ‘all elements of a situation enter into the transaction as active components’.

Our study also revealed additional noteworthy findings. Since students developed the diversity and cultural competencies gradually through immersion in diversity activities, they initially did not recognize the importance of some competencies. Before engaging in these activities, students considered only open-mindedness, listening, and empathy as important for working effectively with diverse patients. It was only after completing specific diversity activities and working with simulated patients that they appreciated the relevance of self-reflection, exploration, partnership, praise, and knowledge of cultural beliefs and practices. This finding is significant because, although these medical students had some prior knowledge and experience with diversity and were just beginning their clinical training, they were not experts. It indicates that prior experience alone might be insufficient and that healthcare professionals require lifelong development in working with diversity, supported by refresher training and ongoing experience with patients from diverse cultural and social backgrounds. This reflects the fact that the world is constantly evolving, and certain factors that were less apparent in the past are now more visible. For example, increased population mobility, language barriers, a growing aging population, and the widespread availability of health information—which can lead to assumptions about high health literacy—are all more prominent today. Additionally, reflecting on clinical experiences requires time, which is often limited. This highlights the importance of lifelong learning and continuous professional development. This is likely applicable to junior healthcare professionals in any field and to those without extensive expertise in diversity.

Another important contribution of this study is the Wheel Model of diversity and cultural competencies, which shows that empathy and cultural empathy are at the center of the wheel, while open-mindedness is the driving force. However, all competencies are needed in order to get the wheel rolling effectively. On this note, the Wheel Model can guide medical curricula and continuing education by framing diversity and cultural competence as an interconnected skill set rather than isolated learning objectives. Embedding each competency—such as knowledge, open-mindedness, exploration, deep listening, empathy, partnership, praising, and self-reflection—into foundation disciplines (like sociology and psychology), communication training, clinical skills sessions, simulations, and clinical placements encourages learners to learn and practice them simultaneously. Positioning empathy and cultural empathy at the center reinforces that understanding patients is the foundation of effective care. Educators can use the model to design longitudinal activities, reflective exercises, and feedback processes that highlight how the competencies interact. Such integrated approach promotes sustained development of culturally responsive and patient-centered practitioners.

In spite of these insightful findings, our study has some limitations. First, it focused on only one cohort of medical students; students in Years 5 or 6 might have identified different competencies, drawing from greater clinical experience. Therefore, it would be helpful to also study Year 5 and 6 cohorts and undertake a comparative analysis. Second, the diversity activities themselves may have influenced the competencies students identified. Although students were encouraged to reflect critically rather than adopt views passively, their limited experience may have hindered deeper reflection. This limitation could be overcome with further reflection and a comparative analysis of older cohorts of students. Third, although facilitators coordinating the groups were trained to make prompts and record students’ responses on flip charts, some variability in interpreting students’ input could have occurred. This limitation could be addressed by introducing a pilot phase in any follow-up studies. Fourth, our study did not involve a comparison with independent observational data or clinical assessments and relied solely on what participants experienced and understood. A follow-up study that would consider both participants’ experiences and facilitators’ observations in combination with participants’ performance in exams would provide more insights into the effectiveness of the competencies.

Despite these potential limitations, the striking similarities between our findings and those of several Delphi studies with diversity and cultural competency experts suggest our participants were unlikely to be biased by the diversity activities or their limited knowledge and experience. Moreover, this study opens new avenues for research into diversity and cultural competencies as generated by students or professionals in other fields such as nursing, physiotherapy, nutrition, pharmacy, and more. Additionally, it would be valuable to examine the impact of each competency and the relationships among them on patient satisfaction, adherence to therapy, and health outcomes.

5. Conclusions

The medical students who participated in this PAR study identified eight overarching diversity and cultural competencies: “open-mindedness,” “empathy and cultural empathy,” “deep listening,” “explore further,” “knowledge,” “self-reflect”, “work in partnership,” and “praise the patient” as essential for working effectively and appropriately with diverse patients. These competencies are interconnected rather than standing alone, all contributing toward the goal of understanding the patient as deeply as possible to provide the highest quality of care. In this context, the study proposed the Wheel Model, which places “empathy and cultural empathy” at the center, with the other competencies reinforcing healthcare professionals’ understanding of their patients, and “open-mindedness” as the driving force. This model also opens new avenues for research to explore the impact of diversity and cultural competence on health outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.C.; Methodology, C.S.C., P.A., E.K. and A.P.; Formal analysis, C.S.C. and P.A.; Investigation, C.S.C., P.A., E.K. and A.P.; Data curation, C.S.C. and P.A.; Writing—original draft, C.S.C.; Writing—review & editing, C.S.C., P.A., E.K. and A.P.; Supervision, C.S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Cyprus National Bioethics Committee (protocol code: ΕΕΒΚ ΕΠ 2024.01.296, 23 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Betancourt, J.; Green, A.R.; Carrillo, J.E.; Ananeh-Firempong, O. Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public. Health Rep. 2003, 118, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, S.; Chavan, M. Cultural competence dimensions and outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Health Soc. Care Community 2016, 24, e117–e130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvat, L.; Horey, D.; Romios, P.; Kis-Rigo, J. Cultural competence education for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renzaho AM, N.; Romios, P.; Crock, C.; Sønderlund, A.L. The effectiveness of cultural competence programs in ethnic minority patient-centered health care—A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2013, 25, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, E.G.; Beach, M.C.; Gary, T.L.; Robinson, K.A.; Gozu, A.; Palacio, A.; Smarth, C.; Jenckes, M.; Feuerstein, C.; Bass, E.B. A systematic review of the methodological rigor of studies evaluating cultural competence training of health professionals. Acad. Med. 2005, 80, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GMC. Good Medical Practice. 2024. Available online: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/good-medical-practice-2024---english-102607294.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- AAMC. The Core Competencies of Entering Medical Students. 2024. Available online: https://students-residents.aamc.org/media/15376/download (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Carballeira, N. The Live & Learn Model for culturally competent family services. Contin. (Soc. Soc. Work Adm. Health Care) 1997, 17, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Leininger, M. Culture Care Theory: A Major Contribution to Advance Transcultural Nursing Knowledge and Practices. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2002, 13, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnell, L. The Purnell Model for Cultural Competence. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2002, 13, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordijk, R.; Hendrickx, K.; Lanting, K.; MacFarlane, A.; Muntinga, M.; Suurmond, J. Defining a framework for medical teachers’ competencies to teach ethnic and cultural diversity: Results of a European Delphi study. Med. Teach. 2019, 41, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirwe, M.; Gerrish, K.; Keeney, S.; Emami, A. Identifying the core components of cultural competence: Findings from a Delphi study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 2622–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour, I.; Irandoost, M.; Lorestani, H.; Sahabi, J. Identifying the Factors Affecting the Cultural Competence of Doctors and Nurses in Government Organizations in the Health and Medical Sector of Iran. J. Healthc. Manag. 2022, 12, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Montecinos, J.B.; Grünfelder, T. What if we focus on developing commonalities? Results of an international and interdisciplinary Delphi study on transcultural competence. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2022, 89, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, D.; Kim, H.; Yoo, J.Y.; Lee, J. Agreement on Core Components of an E-Learning Cultural Competence Program for Public Health Workers in South Korea: A Delphi Study. Asian Nurs. Res. 2019, 13, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojanen, T.T.; Phukao, D.; Boonmongkon, P.; Rungreangkulkij, S. Defining Mental Health Practitioners’ LGBTIQ Cultural Competence in Thailand. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. 2021, 29, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, C.; Lindberg, D.; Morell, I.A.; Gustafsson, L.-K. Swedish experts’ understanding of active aging from a culturally sensitive perspective—A Delphi study of organizational implementation thresholds and ways of development. Front. Sociol. 2022, 7, 991219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, D.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S.; Mårtensson, L. Development of a cultural awareness scale for occupational therapy students in Latin America: A qualitative Delphi study. Occup. Ther. Int. 2016, 23, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Farokhzadian, J.; Nematollahi, M.; Nayeri, N.D.; Faramarzpour, M. Using a model to design, implement, and evaluate a training program for improving cultural competence among undergraduate nursing students: A mixed methods study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzen, S.; Papma, J.M.; Berg, E.V.D.; Nielsen, T.R. Cross-cultural neuropsychological assessment in the European Union: A Delphi expert study. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2021, 36, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jervelund, S.S.; Vinther-Jensen, K.; Ryom, K.; Villadsen, S.F.; Hempler, N.F. Recommendations for ethnic equity in health: A Delphi study from Denmark. Scand. J. Public Health 2023, 51, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, L.M.; Jorm, A.F.; Kanowski, L.G.; Kelly, C.M.; Langlands, R.L. Mental health first aid for Indigenous Australians: Using Delphi consensus studies to develop guidelines for culturally appropriate responses to mental health problems. BMC Psychiatry 2009, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, D.K. Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome of Internationalization. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2006, 10, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, S.; Michaëlis, C.; Sørensen, J. Diversity Competence in Healthcare: Experts’ Views on the Most Important Skills in Caring for Migrant and Minority Patients. Societies 2022, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinou, C.S.; Nikitara, M. The Culturally Competent Healthcare Professional: The RESPECT Competencies from a Systematic Review of Delphi Studies. Societies 2023, 13, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, F.; Breton, N.; Moreno-Tabarez, U.; Delgado, J.; Rua, M.; de-Graft Aikins, A.; Hodgetts, D. Participatory action research. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2023, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Spencer, L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In Analysing Qualitative Data; Bryman, A., Burgess, G., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).