1. Introduction

The rapid development of information and communication technology (ICT) has transformed everyday communication, learning, and social interaction. The internet provides opportunities for acquiring knowledge, connecting with others, and expanding access to information, but it also brings new social risks related to exposure to inappropriate content and harmful online behavior. The rapid digitalization of children’s lives has created both opportunities and serious online risks. Digital violence is a broad concept encompassing non-physical but harmful online behaviors such as cyberbullying, online harassment, impersonation, and social exclusion. Although these acts lack physical force, they are conceptualized as forms of violence because they may cause psychological harm and social exclusion, consistent with the broader definitions of violence adopted by the World Health Organization [

1] and UNESCO [

2], which include physical, psychological, and social forms occurring both offline and online.

These risks particularly affect children and adolescents, who spend increasing amounts of time in digital environments and are more vulnerable to the consequences of online interactions [

3,

4,

5]. Recognizing this, the protection of children from online risks has become a growing priority for educational and social policy in many countries [

6]. The double nature of digital communication—its potential for both empowerment and harm—makes understanding online behavior among youth a crucial issue for education and social policy.

Children today start using the internet at very early ages, most often through personal mobile devices and without sufficient parental supervision [

7]. Constant exposure to digital content shapes their communication, values, and emotional development but also increases their vulnerability to inappropriate and violent material [

4,

7]. Therefore, it is essential to guide them toward responsible and safe internet use. In accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, children should have access to age-appropriate online content and protection from harmful influences. Developing digital literacy among both children and parents is a key factor for reducing online risks and strengthening children’s ability to use technology safely [

8].

Modern information and communication technologies have created new forms of aggressive and harmful behavior, leading to the emergence of a complex social issue—digital violence [

7,

9]. Unlike traditional, physical forms of violence, digital violence occurs in virtual spaces and includes non-physical but psychologically and socially harmful acts such as cyberbullying, online harassment, impersonation, and social exclusion. These behaviors can cause emotional distress, humiliation, and social isolation, producing effects comparable to offline violence. According to the broader definitions of violence established by [

1,

2], such acts represent intentional harm that may be physical, psychological, or social in nature. Therefore, digital violence can be understood as a continuum of violent behavior extending into the digital environment. It also overlaps with other online risks and forms of abuse, including sexual exploitation and exposure to harmful content, which are recognized as serious threats to the well-being and safety of children in modern society [

6,

10].

Families play a critical role in preventing and managing digital violence. Unlike traditional peer violence that typically occurs in physical settings such as schools, digital violence penetrates the home environment and therefore parental supervision becomes especially important [

11]. Effective supervision includes not only parents’ awareness of children’s online activities and free time, but also children’s willingness to report their experiences. The dynamic of parental insight and children’s disclosure is a key factor in monitoring and responding to potential online harm [

12,

13].

Conceptual framing and terminology. In this manuscript, we use digital violence as an umbrella construct that encompasses non-physical but harmful online behaviors—most notably cyberbullying, online harassment, impersonation, and social exclusion. Although these acts do not involve physical force, they are conceptualized as forms of violence because they can produce psychological harm, emotional distress, and social exclusion. This framing is consistent with broader public-health and human-rights approaches that recognize physical, psychological, and relational forms of violence occurring both offline and online [

1,

2]. Empirically, we operationalize digital violence through survey items capturing cyberbullying-related experiences and reactions. Throughout the paper, we use specific labels (e.g., cyberbullying, online harassment) when referring to particular behaviors/items and digital violence when referring to the overarching construct.

For clarity, digital violence denotes the overarching construct; cyberbullying, online harassment, impersonation, and social exclusion refer to specific behaviors/items analyzed in this study.

1.1. Digital Violence

The World Health Organization defines violence as the intentional use or threat of physical force against another person, a group, or a community, which can result in injury, death, psychological harm, developmental disorders, or deprivation [

14]. In line with this definition, digital violence can be understood as intentional acts committed through digital technologies that primarily cause psychological or emotional harm rather than physical injury. These behaviors, which include various forms of aggression and abuse in online spaces, reflect the broader understanding of violence extended into the digital context.

Various terms are used to describe such behaviors, including digital bullying, cyberbullying, online violence, and similar expressions [

3]. Recent literature conceptualizes cyber-violence as a multidimensional phenomenon encompassing behaviors such as cyberbullying, online harassment, doxing, and non-consensual image distribution, highlighting its increasing complexity in the digital society [

15]. For conceptual clarity in this study, digital violence is used as an overarching construct that includes specific forms such as cyberbullying, online harassment, impersonation, and social exclusion.

The term cyberbullying was first introduced at the beginning of the 21st century [

16]. There are many interpretations of what exactly constitutes cyberbullying, but all definitions share a common element—the use of technology (such as computers, mobile phones, tablets, and other electronic devices) with the intent to harm or hurt another person [

17].

“

Cyberbullying is defined as intentional, aggressive behavior carried out by a group or individual, using electronic forms of communication, repeatedly and over time, against a victim who cannot easily defend themselves [

18]”. This type of violence, unlike traditional violence, can take place at any time of day, in any place, and can take place in front of a wider audience. Another aspect that distinguishes cyberbullying from traditional bullying is the potential for anonymity. A person who commits cyberbullying can remain invisible, meaning their identity can be hidden, which further frustrates the victim and increases their sense of powerlessness [

19]. The perpetrator in this form of communication may be less aware, or even unaware, of the consequences of their actions [

9]. Recent findings from a nationally representative study conducted in the United States [

20] indicate that more than half of adolescents (55%) have experienced some form of cyberbullying, with about one in four (27%) reporting incidents within the previous month.

Given the various definitions of digital violence, the question arises as to whether the fundamental criteria used to define traditional violence can be applied to digital violence as well. By these criteria we mean: intent to cause harm, repetitiveness of violent behavior, and power imbalance between the perpetrator and the victim [

21]. The three primary roles in digital violence are the role of the bully, the victim, and the bully-victim (former victim, current bully) [

22]. The prevalence of the main roles in digital violence varies, but a consistent finding is that there are more victims of digital violence than perpetrators.

As the literature suggests, the motivation for digital violence is the same as the motivation for traditional forms of violence, in-person forms of violence. Violence serves as a means to an end, rather than an end in itself [

21].

Varjas and colleagues categorized the motives for cyberbullying into internal and external [

23]. Internal motives, which are based on emotional states, include the desire for revenge, boredom, jealousy, and role-playing. Revenge in particular, is frequently identified as a primary motive for digital violence in numerous studies [

24]. Abusers often identify their anger and desire for revenge as immediate reactions to the frustration they experience. In such cases, digital devices provide the opportunity for an immediate reaction that should contribute to reducing anger and frustration. Violence is often a “mask” to cover up feelings of inadequacy, thereby regulating that feeling by humiliating another person. In other words, the perpetrator may experience a sense of relief or empowerment by making someone else feel worse. In this way, violence serves to build a more positive self-image [

21]. External motives relate to characteristics of the victim or the situation [

21]. These motives arise from an unwillingness to confront the victim directly, the lack of consequences from the violent act, or the characteristics of the victim that make them different from others. Perpetrators tend to commit violence against passive individuals, whom they believe will not retaliate or take revenge [

25].

1.2. Types of Digital Violence

Scientific and professional literature identifies several different forms of digital violence, highlighting specific behavioral patterns that aim to threaten the dignity, safety, or social integration of an individual in the online environment. The most common forms of digital violence include: sending messages with offensive and vulgar content; issuing threats; spreading rumors and false information with the intention of damaging someone’s reputation or social relationships; impersonation using pseudonyms or someone else’s identity; misuse of private information, such as revealing secrets and sharing personal photos without consent; social isolation through excluding an individual from virtual communities (forums, discussion groups, etc.); sending inappropriate sexual content; as well as recording and sharing scenes of physical violence [

13,

26].

The classification of digital violence presented by Li [

27] served as the basis for identifying seven characteristic models of online violent behavior. However, the terminology and conceptual descriptions of these forms have been further clarified and refined in more recent studies exploring this phenomenon in greater depth [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]:

Verbal aggression, i.e., sending angry, offensive and rude messages to an individual or group in the digital space. Verbal aggression frequently occurs in multiplayer online video games, where players may feel more disinhibited to insult, offend, or verbally bully one another through chat or character interaction.

Repeated harassment, manifested through the frequent sending of threatening content directed at one person.

Cyberstalking, involving prolonged harassment with the aim of causing emotional or psychological harm to the victim. Cyberstalking involves the persistent monitoring and pursuit of a victim through digital means, using online information, social media platforms, or mobile communication networks to track their activities and invade their privacy.

Defamation and spreading falsehoods—publishing harmful, inaccurate, or malicious claims about a person. Publishing defamatory content online carries broader consequences than traditional forms of defamation, as digital materials are globally accessible, easily shared, and often produced under anonymity—factors that intensify reputational harm and complicate accountability in the online environment.

False representation, impersonating someone else in order to send or disseminate content that discredits or presents the victim as a threat. The widespread anonymity and accessibility of fake accounts on social media have intensified the issue by allowing users to participate in cyberbullying and other forms of digital aggression with diminished responsibility for their actions.

Abuse of trust, sharing confidential, private or compromising information, including personal messages and photos. Recent data indicates many online abuse cases involve non-consensual sharing or threats thereof of private images, thereby constituting a clear breach of trust and a distinct form of digital violence.

Social exclusion, as the intentional omission or elimination of an individual from virtual communities or groups.

The literature also identifies other forms of digital violence, such as “happy slapping”, i.e., a physical attack on a person that is recorded and then shared online, as well as the intentional disruption of some online activities such as texting or playing games online [

33,

34].

1.3. Protection from Digital Violence

Protecting children from digital violence requires a multisectoral approach that includes coordinated action by all relevant actors—the state, family, educational institutions and the media. Systemically and responsibly directed activities at all these levels are a prerequisite for ensuring a safe digital environment and enabling children to use the internet in a way that is safe, developmentally stimulating and in line with their rights and needs [

8]. The key to preventing digital violence, as previously stated, lies in the cooperation of educators, students, parents, and the media, but also in their adaptation to the evolving digital environment. Social support, as research suggests, reduces exposure to digital violence, so parents and teachers should be encouraged to get involved in children’s social lives and strengthen these relationships. Peer support has also been identified as a significant protective factor, and intervention and prevention strategies should aim to increase the stability and effectiveness of peer support [

20,

35,

36]. A comprehensive national framework should therefore combine legislative safeguards with proactive community engagement, digital literacy, and parental mediation strategies aimed at fostering responsible and safe online behavior [

37].

Reducing the participation of young people in digital violence can be achieved through the implementation of well-designed preventive programs. In the implementation of these programs, state institutions, the educational system, the family and the media play a key role. These programs should be aimed at raising social awareness about the consequences of digital violence and promoting non-violent communication in the online space. Special emphasis must be placed on educating young people that threats and aggressive behavior towards others are a form of abuse that can cause serious and lasting psychological consequences for the victim. It is essential to develop the capacities of young people to recognize violence, not to withdraw into themselves, and to have the confidence to report any form of digital abuse to an adult and responsible person [

26,

38].

Since some children, due to their demographic and individual characteristics, are at greater risk of experiencing negative consequences associated with digital technologies and the Internet, it is essential to identify these children and provide them with appropriate preventive measures, as well as help when negative consequences occur [

7].

The research results indicate that both perpetrators and victims of digital violence represent groups that should be included in programs aimed at reducing involvement in such behavior and mitigating its consequences, particularly depression, anxiety, and stress. These programs should incorporate strategies for emotion regulation, as the absence of empathy is often a characteristic of individuals who perpetrate this form of violence [

39,

40]. Therefore, intervention programs for perpetrators should be specifically designed to promote empathy towards victims [

39].

There are various prevention programs around the world that educate young people on how to focus on healthy friendships and relationships, so as to avoid becoming victims of violence. The effectiveness of one such program was demonstrated in 2020 in a study by Vivilo Kantor and colleagues. The program, originally called Dating Matters, aims to educate students and prevent all forms of violence before any such behavior occurs. The results of this research showed that students attending schools implementing this program reported 11% less violence compared to students in schools implementing other student education programs. Compared to other programs, Dating Matters has shown protective effects on both physical and digital violence [

41]. Although many technology companies are introducing various safety tools and procedures for reporting digital violence, there is a need to further improve user protection measures. Social networks enable users to manage access to their content and to block or report unwanted contacts [

5]. Recent European analyses underline that protecting children online requires a two-fold approach—systematic investment in education and the development of comprehensive child-centered legislation. According to Eurochild Report [

42], multi-level digital-literacy education involving children, parents, teachers, and law-enforcement officers is essential to enhance digital awareness and resilience. At the same time, legislative reforms are needed to establish clear mechanisms for risk assessment, removal of harmful content, and stronger support systems for children, in line with the Better Internet for Kids+ strategy [

43], and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

1.4. Digital Violence Prevention in Serbia

The prevention of digital violence in Serbia is grounded in several key legislative and institutional mechanisms. The Regulation on the Safety and Protection of Children in the Use of Information and Communication Technologies, adopted in 2016, requires the Ministry of Trade, Tourism and Telecommunications to establish a single reporting and counseling point for cases of digital violence, thereby promoting awareness and accountability in the digital environment. The Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development and its Violence Prevention Group has been implementing prevention initiatives since 2009, notably through the national project “Click Safely”, A significant role in the fight against this type of violence is played by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Department for High-Tech Crime, which have been dealing with this problem since 2007. Additional institutional support is provided by the Violence Prevention Team at the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development, which has existed since 2012 [

8]. In the context of Serbia, findings from the Eurochild Digital Sub-Report [

42], indicate that cyberbullying is identified as the most pressing issue children face in the digital environment. This phenomenon is particularly prevalent in schools, peer groups, and sports teams, with potentially severe and long-lasting consequences for affected children. The anonymity provided by online platforms facilitates such behavior, while the increasing digitalization of society has further amplified the pre-existing problem of traditional bullying [

42].

In recent years, Serbia has implemented numerous projects dedicated to the prevention of digital violence, targeting children, parents, and teachers through training, workshops, and educational campaigns. Through training, workshops and expert lectures, as well as publications and research, these programs contribute to raising awareness about this type of violence. The celebration of Safe Internet Day on 9 February is accompanied by a series of public events and forums. However, most initiatives are implemented at the national level, while local support is less represented. Future efforts should include the establishment of counseling centers and regional response teams that provide psychological support and guidance to victims of digital abuse [

8].

In addition, it is important that parents are sufficiently informed and literate when it comes to digital technologies. It is not uncommon for children to be more digitally literate than their parents [

11,

12]. In a survey conducted in the Republic of Serbia in 2019, the data that is particularly concerning is that more than half of the surveyed students aged 9–12 often help their parents when they do not know how to do something online, as do three-quarters of respondents aged 13–17 (more often girls than boys). The authors of this research recommend that adults, particularly parents, guardians, and individuals working in education, acquire appropriate digital skills to adequately prepare children for entering the digital world in a timely and developmentally appropriate manner [

7]. Furthermore, the Eurochild Report [

42], Digital Sub-Report emphasizes that Serbia has highlighted the need to invest in multi-level education in digital literacy to strengthen children’s online protection. This approach involves coordinated training and awareness programs for children, parents, teachers, and law enforcement officials, aiming to build a safer and more informed digital environment [

42].

Likewise, it is important to transfer knowledge to children and jointly establish rules for internet use in order to help them develop skills for recognizing and responding to potential online dangers. Every child needs proper guidance and direction. Any feeling of fear, discomfort, or offense caused by a perpetrator is considered a form of violence, with children being the primary targets [

5]. Unlike in previous years when the internet was also used, today’s digital environment presents much greater risks—particularly regarding online content. This should be a major concern for parents, as reducing the generational gap can improve communication between children and parents about challenges in the virtual world [

5,

44]. The same authors state that in addition to reacting to others’ inappropriate behavior on the Internet, it is important for children to understand the potential consequences of their own behavior. Therefore, it is necessary to systematically support students (of all ages) in acquiring digital skills that will enable them, as independent users of digital devices, to protect themselves from potential risks (including technical protection measures), with an emphasis on self-regulation and personal responsibility for their own behavior in the digital environment [

7,

44].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study applied a quantitative, descriptive, and comparative research design to examine the experiences, perceptions, and responses of students and parents regarding digital violence. The research design allowed for identifying key differences in perception and behavior between children and parents in the context of digital violence.

2.2. The Subject of the Research

This research is focused on the examination of differences in the perception of digital violence between parents and children. The subject of this research is to explore the perceptual differences between parents and children in relation to digital violence, with a focus on their views regarding the type of cyber violence and regarding protection from cyber violence.

The research seeks to encompass multiple analytical aspects, including: assessing the time children and young people spend online, examining different ways of accessing digital content, identifying experiences and perceptions regarding cyberbullying, and analyzing awareness and attitudes regarding reporting violent behavior in the online environment. Special attention was paid to comparing the reactions of parents and children to experienced forms of digital violence.

2.3. Sample and Setting

The research involved 5054 children (47.9% boys), students at regular elementary schools, from 5th to 8th grade. Data were collected from January 2022 to October 2022 in primary schools in the territory of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina as part of the project of the Provincial Secretariat for Education, Regulations, Administration and National Minorities-National Communities “Violence on the Internet: How to Prevent and Fight Violence on the Internet?”. The distribution of students by grade and gender is shown in

Table 1. It can be observed that the 8th grade students are the least represented numerically, while the gender distribution among all participants is balanced. For the purposes of this research, data were collected through questionnaires completed by the students.

Additionally, 6309 parents or guardians (11.7% male), with an average age of 40.1 years (SD = 7.43), whose children attend regular primary school from 5th to 8th grade, also participated in the study. To collect data within the research, questionnaires for parents were created and used in the research.

2.4. Instruments

In order to collect data within the framework of the research, anonymous questionnaires were created for both children and parents. The questionnaires consisted of two parts: the first part covered sociodemographic data, while the second part focused on experiences with digital violence, attitudes toward this type of violence, and the possibilities for protection against it. An online version of the questionnaire was used for parents.

The questionnaire for parents was designed to gather information on gender and place of residence, as well as their awareness of where their children most often access the Internet and how they use it. The second part of the questionnaire was designed to gather information from parents about their awareness of whether their children have ever experienced online violence, the type of violence encountered, and how they responded if such incidents occurred. The final part of the questionnaire for parents consists of statements related to protection from online violence. In order to help parents, understand the meaning of the term “online bullying”, a definition of the term was provided before completing the questionnaire.

The questionnaire completed by the students consisted of questions related to gender, place of residence, age, time spent on the Internet, the location from which they most often access the Internet, and the purposes for which they use it. The second part of the questionnaire referred to whether they had ever experienced any form of digital violence, when the incident occurred, and how they responded to it. The final part consisted of statements related to protection from digital violence.

4. Discussion

The increasing presence of technology in our daily lives has not only expanded opportunities but also heightened the risks, including the emergence of new forms of violence such as digital violence. Increased cyberbullying among primary school children is being observed more and more frequently. The new WHO/Europe study finds that one in six school-aged children experiences cyberbullying [

45]. According to a study conducted in Slovenia by the national awareness center Safe.si, 65% of girls and 55% of boys reported experiencing some form of cyberbullying during the final three years of primary education [

46]. The growing number of children who possess their own mobile phones contributes to their digital independence, which, in turn, heightens the risk of exposure to digital violence.

In order to gain insight into the situation in Serbia regarding digital violence and primary school children, specifically those from 5th to 8th grade, this research was conducted. This study examined differences between parents and children regarding their perceptions of various forms of cyber violence, as well as their perceptions of protection against cyber violence. The study examined the views of both parents and children on the following issues: how much time children in this age group spend online, their access to a personal mobile phone, and whether they have experienced any specific form of digital violence.

The findings reveal a statistically significant discrepancy between parents’ and children’s estimates of online time, with parents consistently underestimating the actual time their children spend online. The data also shows disagreements in the assessment of the devices children use to access the internet. While most children report that they most often connect via their personal mobile phone, a slightly smaller percentage of parents recognize this. This indicates limited parental insight into their children’s daily online habits, which has implications for the effectiveness of parental supervision and the possibility of preventing risky situations in the digital environment. These findings also indicate that between 85% and 95% of children from 5th to 8th grade in Serbia own a mobile phone. This aligns with international trends, where, for example, in the UK, 91% of children own a smartphone by the age of 11 [

47]. Similarly, a study across 19 European countries found that 80% of children aged 9 to 16 use a smartphone to access the internet daily or almost daily, while in the United States, 42% of children own a smartphone by the age of 10, and ownership increases to 91% by the age of 14.

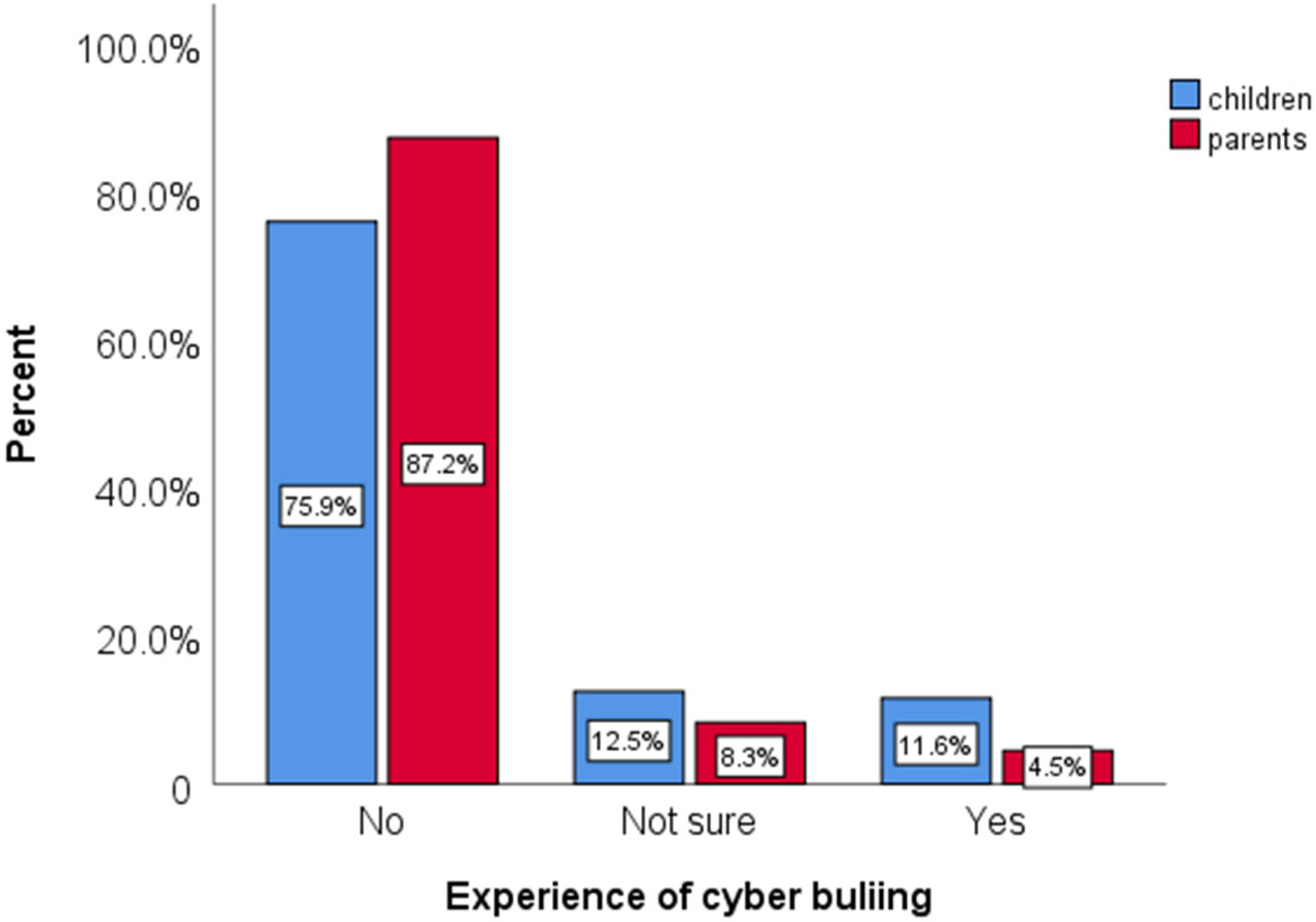

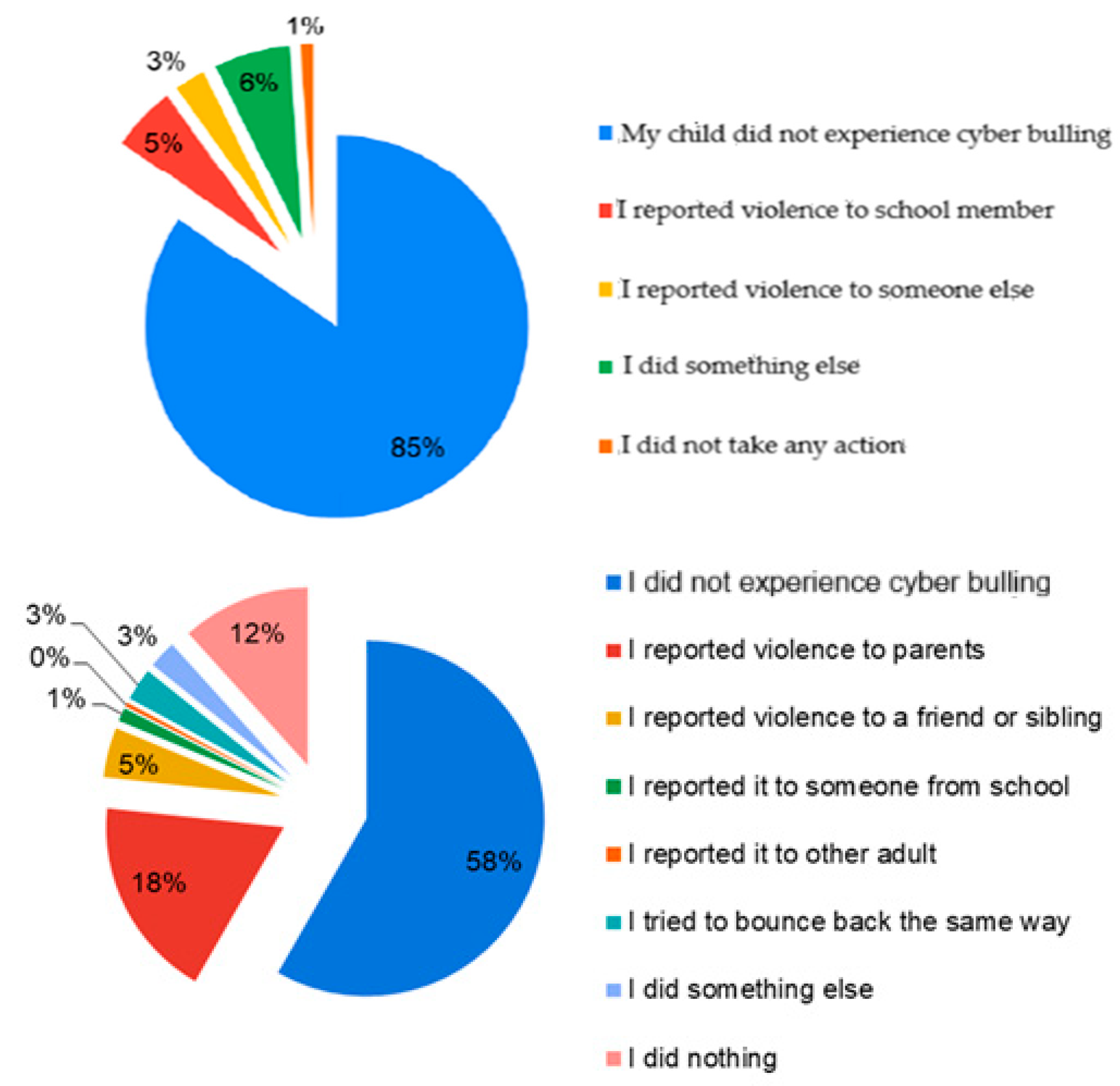

Most children and parents reported no experience with cyberbullying, indicating that some children do not inform their parents about such experiences, highlighting a gap in communication and awareness between the two groups. Most children have not experienced cyberbullying, but their slightly higher average responses compared to parents suggest they do not report everything they encounter online.

Both parents and children expressed a high level of agreement with the views related to the importance of prevention and intervention, although parents, in line with expectations, expressed a slightly higher level of information.

When it comes to specific reactions to experienced violence, it was observed that children most often report the problem to their parents, while turning to school or friends is much less common. The analysis of reactions to cyberbullying revealed communication asymmetry. Children reported a higher frequency of cyberbullying experiences than their parents recognized, implying that some incidents remain undisclosed. This gap may arise from children’s reluctance to share experiences due to shame, fear of losing online privileges, or the perception that adults will overreact. In contrast, parents who were aware of incidents generally acted upon them, most often by discussing the matter with the child or contacting the school. The data thus suggest that the challenge lies not in parental inaction but in limited transparency and dialog between generations. These patterns underline the importance of strengthening reciprocal communication and digital literacy within families. These findings emphasize the importance of fostering open and trusting family communication. Parents should be supported through digital literacy programs that help them identify warning signs of online abuse, while children should be actively encouraged and empowered to share their experiences without fear of blame or restriction. Schools can play a mediating role by promoting dialog between families and educators, ensuring that both children and adults understand the mechanisms for reporting and managing cyberbullying. By removing emotional and informational barriers to disclosure, such coordinated approaches can significantly improve early detection, response, and prevention of digital violence.

The research results indicate that cooperation and communication are essential both within the family and between the family and the school. It is necessary to strengthen trust among groups and individuals, as this would facilitate honest communication and mutual confidence, which are key for timely response in cases of digital violence.

5. Conclusions

The everyday use of electronic media has become deeply embedded in the lives of many individuals—particularly children and adolescents—who rely on them for communication, social interaction, and access to information [

48]. Given this growing digital presence, the findings of our study provide valuable insight into how these online environments also expose children to potential risks, particularly various forms of digital violence and cyberbullying.

This statistically significant difference indicates that parents systematically underestimate their children’s actual online activity, suggesting limited insight into their daily digital routines. Such a discrepancy points to a lack of parental supervision and awareness, which may reduce the effectiveness of prevention and timely intervention in cases of risky or harmful online behavior. These findings align with recent European studies highlighting the persistent digital literacy gap between generations, where children’s independent internet use often exceeds parental perception and control [

42].

The implementation of broader research that includes a larger number of parents and children is crucial for understanding the current state of digital violence among primary school-aged children, particularly by comparing the perceptions of children and their parents. The findings of this study confirm that the growing access of children to personal mobile devices increases the likelihood of encountering online risks. Naturally, modern information technology cannot be separated from our everyday lives, but it is necessary to monitor children’s activities and foster cooperation, communication, and trust within the family and between the family and the school. Continuous programs and training are needed on the types of digital violence, how it manifests, and how children and parents can respond when they find themselves in such situations.

Future investigations should explore longitudinal patterns of children’s exposure to online risks, as well as the long-term effects of preventive education programs. Comparative international research could provide insight into cultural and systemic differences in how families, schools, and institutions respond to digital violence.