Abstract

Climate change is one of the most pressing environmental challenges of our time, with consequences that extend far beyond temperature rise. Its impacts include extreme weather events, sea level rise, biodiversity loss, and disruptions to food and water systems, all of which threaten ecosystems and human well-being. Addressing this crisis requires a broad understanding and engagement from society. However, climate change denial persists, often amplified through online platforms, slowing down effective action. Universities can play a critical role in this context, not only as spaces where scientific knowledge is produced and shared, but also as institutions that train future leaders to respond to environmental crises. In this study, we examined the prevalence of climate change denial among members of a Portuguese public university and explored its relationship with gender, religion, and political orientation. We collected 89 responses and analyzed the data. The findings indicate that individuals with right-leaning political views, certain religious affiliations, and male respondents were more likely to deny climate change. These results highlight the need for targeted educational approaches that address specific audiences, fostering a better understanding of the scientific and environmental realities of climate change, and ultimately promoting informed action toward sustainability.

1. Introduction

Climate change is one of the most pressing global challenges, with its effects increasingly evident across the planet. Rising temperatures, more frequent extreme weather events, and shifting ecosystems provide compelling evidence of ongoing alterations in the Earth’s climate system. Despite this, a substantial proportion of the population continues to doubt or deny the reality of climate change [1,2]. The scientific consensus is unequivocal: human activities are the primary drivers of contemporary climate change, mainly through greenhouse gas emissions resulting from fossil fuel combustion, deforestation, and industrial processes [3,4]. Nevertheless, misinformation and organized denial campaigns persist, promoted by individuals, organizations, and corporations seeking to minimize or obscure the severity of the crisis [5,6,7].

Climate change denial can take several forms, categorizing denial strategies into four main types: rejecting evidence of warming, attributing observed changes to natural rather than human causes, minimizing potential impacts, and portraying scientific consensus as uncertain or contested [8]. Social media amplifies the reach of these narratives, allowing false information to spread rapidly and gain visibility far beyond traditional media channels [9]. Algorithms favor content that evokes strong emotional reactions, further enhancing the influence of denialist messages [10,11]. Research indicates that denial campaigns are sometimes financially supported by interest groups aiming to slow climate action [6,12], making the issue both a social and political concern [13]. Individual characteristics play a critical role in shaping perceptions of climate change. Political orientation is one of the strongest predictors: conservatives, particularly in Western countries, often express lower trust in climate science and are more likely to question human causation, reflecting the influence of ideological beliefs and motivated reasoning [14,15,16]. Men are generally more likely than women to downplay environmental risks, potentially due to societal norms regarding risk perception and environmental responsibility [17,18]. Religious beliefs can also influence attitudes, as some traditions emphasize divine control over nature, reducing perceived human responsibility for climate impacts [19,20]. Education is another crucial factor: higher levels of formal education are consistently associated with increased climate literacy, greater support for mitigation policies, and stronger trust in scientific institutions [2,21,22]. Together, these findings demonstrate a complex interplay between cultural, political, religious, and educational influences on climate change beliefs.

A common misconception among skeptics is the inability to predict future climate due to the inherent variability of weather. While short-term weather forecasts can be uncertain beyond a few days, climate refers to long-term statistical trends and averages over decades, which can be reliably projected using physical models of the Earth’s atmosphere, oceans, and biosphere. Climate models, validated against historical data, successfully reproduce observed temperature trends and other climate variables, providing robust projections under different greenhouse gas emission scenarios [23]. Therefore, claims that climate science is unreliable because “we cannot predict next week’s weather” reflect a misunderstanding of the distinction between weather and climate.

Education and public awareness are essential for addressing climate change skepticism. Schools and universities play a central role in developing climate literacy, fostering critical thinking, and training experts capable of addressing environmental challenges [24]. Despite this, the integration of climate science into higher education curricula remains uneven globally. A study covering universities in 51 countries found that, although the climate crisis is worsening, awareness and understanding of the issue vary considerably, particularly in some Asian institutions. Strengthening climate education and fostering international collaboration among universities are crucial strategies for combating misinformation and promoting evidence-based understanding of climate science [25].

In summary, climate change skepticism is a multifaceted phenomenon influenced by political ideology, gender, religious beliefs, and educational background. It is exacerbated by the spread of misinformation through digital media and by deliberate denial campaigns. Understanding the factors that contribute to skepticism is essential for designing effective communication strategies, enhancing climate literacy, and fostering informed action. Universities, as centers of scientific knowledge and critical thought, have a pivotal role to play in preparing future generations to confront climate challenges and to develop sustainable solutions across diverse fields.

2. Materials and Methods

About the study descriptive/exploratory, quantitative, descriptive-analytical. The study was conducted at the Polytechnic Institute of Bragança, a public higher education institution located in northeastern Portugal. The institution offers a wide range of undergraduate and graduate programs across science, technology, education, and social sciences, attracting students primarily from small- and medium-sized towns in the region.

The objective was to estimate the prevalence of climate denial among members of the university community and examine associations with sociodemographic variables (gender, religion, political orientation). The instrument was developed by the authors based on the literature on scientific perceptions and climate denialism. This study may be important, given the lack of specific literature in Portugal.

The questionnaire included three main sections: (A) sociodemographic data (age, gender, course/area, year, religious affiliation, political-ideological orientation), (B) questions about beliefs regarding climate change (items on existence, causes—anthropogenic vs. natural—perception of risk, and trust in science), and (C) questions about sources of information and behavior (e.g., reading the media, participating in environmental activities).

The instrument was validated through expert review to ensure content and construct validity. The university ethics committee also gave us its approval (information edited for double-blind review). The questionnaire was administered online via Google Forms. The first page contained the Informed Consent Form, which explained the study’s objectives, the principles of anonymity/confidentiality, the voluntary nature of participation, and the option to withdraw at any time. Only participants who indicated their consent were allowed to proceed. All data were collected during February 2025. No financial rewards were offered.

The responses were exported from Google Forms into a CSV file and checked for completeness and consistency. Data analysis was performed using JAMOVI 2.6.45, an open-source statistical software. Descriptive statistics were computed, and data normality was assessed to determine the appropriate nonparametric tests. The Mann–Whitney U test was applied for comparisons between categorical and continuous variables, while the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare more than two independent groups.

The following data-cleaning criteria were applied: (i) exclusion of responses with more than 50% missing values; (ii) identification and removal of potential duplicates; and (iii) plausibility checks for age and inconsistent responses. It is acknowledged that the sample was convenience-based and relatively small (n = 89), with a 100% completion rate, which limits the generalizability of the findings and the power to detect small subgroup differences. Furthermore, as the data were self-reported and collected online, potential selection bias and socially desirable responding cannot be ruled out. Table 1 provides an overview of participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (sex, religion, and political spectrum) are expressed in percentages.

3. Results

Below, we present the main results for the variables gender, religion, and political spectrum.

Since there were just two groups, we used the Mann–Whitney U test to see if their answers to the climate denialism questions were different. The results indicate that men and women have different ideas about climate change, including how much they trust certain sources and what they believe about climate denial. You can see these differences in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mann–Whitney U test results, correlation of gender with items.

For the item “I consider climate change to be an excuse for scientists to exploit monetary interests”, the t-value is 2.83 and p = 0.006, suggesting that there is a significant difference between men and women, with men more likely to agree with this idea. For “Scientific entities IPCC, NASA are trustworthy,” the negative t (−4.33) indicates that women trust these institutions more than men. Predicting the weather for the next week is difficult; predicting climate scenarios for the future is impossible. Men tend to agree more with the statement that predicting the climate for the future is impossible. The idea that women are more sensitive to environmental issues is not new; several studies consistently show that women tend to have stronger beliefs and concerns about climate change than men. [26,27,28].

When it comes to the statement, “I think climate change is just scientists trying to get money,” the data show a notable difference between men and women (t = 2.83, p = 0.006). Men are more inclined to agree with this. Regarding trust in scientific groups like the IPCC and NASA, the data (t = −4.33) point to women trusting these groups more than men. Men also seem to agree more that predicting future climate scenarios is impossible, even if predicting next week’s weather is tough. The idea that women care more about the environment is not breaking. Studies [26,27,28] back this up, showing women usually have stronger feelings and worries about climate change than men.

3.1. Religion

We used the Kruskal–Wallis Test, which is a test that does not rely on specific distribution assumptions and lets us see if the medians differ across the four religions we are studying. You can find the specifics in Table 3 and Figure 1 below.

Table 3.

Chi-square test results showing differences in responses to climate change statements according to religion.

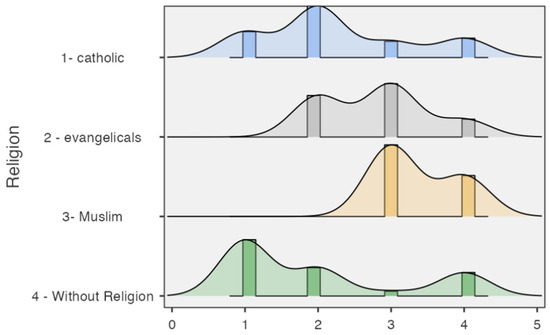

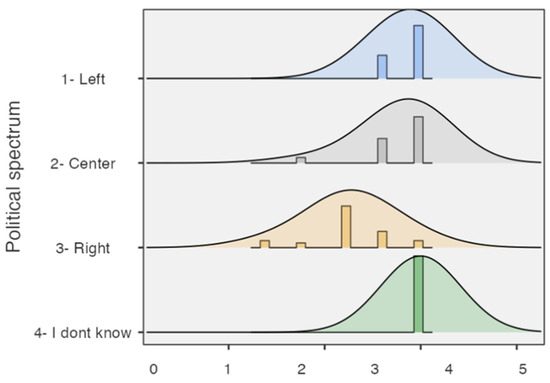

Figure 1.

Distribution of responses by religion “I think climate change is just an excuse to exploit taxpayers.” The numbers 0 to 5 in the graph refer to the Likert scale where lower values are “I completely disagree” and higher values are “I completely agree”. (Source: made by authors).

We used the Kruskal–Wallis Test to see if there were differences in the average opinions among the four religious groups. You can find specifics in Table 3 and Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3.

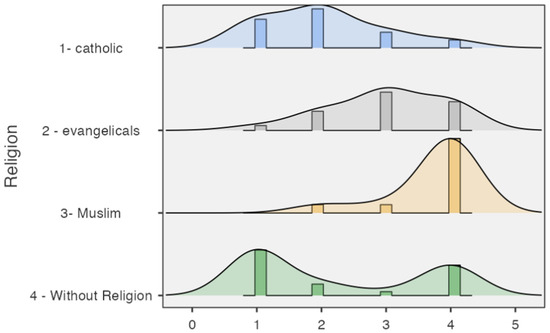

Figure 2.

Distribution of responses by religion “Climate Change has always been part of the planet’s history, and I don’t think human beings have interfered with it”. The numbers 0 to 5 in the graph refer to the Likert scale where lower values are “I completely disagree” and higher values are “I completely agree”. (Source: made by authors).

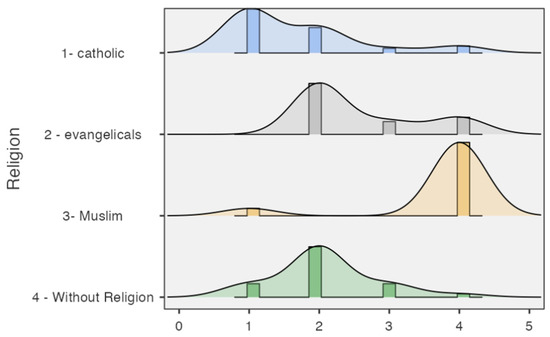

Figure 3.

Distribution of responses by religion “Predicting the weather for the following week already implies error, I think predicting climate scenarios for the future is impossible”. The numbers 0 to 5 in the graph refer to the Likert scale where lower values are “I completely disagree” and higher values are “I completely agree”. (Source: made by authors).

Looking at Figure 1, participants’ responses varied by religious affiliation. Catholics exhibited mixed views, with some expressing mild skepticism. Evangelicals were generally more doubtful regarding human influence on climate change and the credibility of scientific organizations, tending to agree with statements expressing doubt. Muslims were also more likely to endorse skeptical ideas, although variability existed within this group. Participants with no religious affiliation displayed more scattered responses, but tended to disagree with skeptical statements, consistent with prior research indicating that secular individuals are more likely to trust science and recognize human impacts on climate [29].

Figure 2 highlights the statement “Climate change has always existed, and humans have nothing to do with it,” showing a bimodal distribution: one group agreed while another disagreed. This illustrates that religious affiliation does not uniformly determine beliefs about climate change, reflecting internal diversity and potential conflicts between traditional beliefs and scientific understanding. Despite public calls by religious leaders [30,31], to care for the planet, a substantial portion of participants within Christian and Islamic groups still expressed climate skepticism. International studies similarly show that evangelicals exhibit lower concern for climate change and are more prone to denial compared to other groups [31]. These results underscore the importance of considering religious beliefs when developing targeted climate communication and educational interventions and suggest that engaging religious authorities as advocates for environmental stewardship could help mitigate skepticism within these communities.

Figure 3 presents the distribution of responses to the statement, “Predicting the weather for the following week already implies error; I think predicting climate scenarios for the future is impossible,” analyzed according to religious affiliation. The results indicate that participants identifying as Muslim were the most likely to agree with this statement, reflecting a higher level of skepticism regarding the ability of climate science to provide reliable long-term projections. In contrast, Catholics and participants with no religious affiliation tended to disagree, demonstrating greater confidence in the predictive capacity of climate models. This pattern suggests that religious beliefs may influence not only general attitudes toward climate change but also perceptions of scientific methodology and uncertainty. The findings align with broader evidence that skepticism can be shaped by cultural, educational, and ideological factors, highlighting the importance of addressing misconceptions about climate science in targeted educational interventions. Understanding these differences is particularly relevant for improving climate literacy and communicating the distinction between short-term weather forecasting and long-term climate projections [32].

3.2. Political Spectrum

We used the Kruskal–Wallis test to compare the medians of more than two groups because it is a non-parametric test. You can find the specifics in Table 3. If a p-value is less than 0.001 (p; 0.001) for an analyzed statement, it tells us that there are real differences between the political groups.

See the results considering the political spectrum in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results for the political spectrum variable.

In general, individuals who identify with right leaning or conservative political ideologies are more likely to express skepticism or outright denial of climate change. One contributing factor is that conservative groups often prioritize free-market principles and advocate for limited government intervention in economic affairs. Climate policies, such as carbon taxes, emissions regulations, or restrictions on industrial practices, may therefore be perceived as direct threats to economic growth, private enterprise, and individual financial interests. Beyond economic concerns, the discourse surrounding climate change frequently implies significant changes to personal lifestyles, including reductions in energy consumption, decreased reliance on fossil fuels, and shifts toward more sustainable but sometimes less convenient behaviors. For members of conservative communities, such changes may be perceived not only as economic burdens but also as challenges to deeply held values, cultural norms, and ways of life [33,34]. Moreover, research suggests that political identity can strongly shape the interpretation of scientific information through processes such as motivated reasoning and identity-protective cognition, whereby individuals selectively accept evidence that aligns with their ideological beliefs while discounting contradictory information. This intersection of economic, cultural, and cognitive factors helps explain why right-leaning individuals may be more resistant to acknowledging the scientific consensus on climate change and why political ideology remains a powerful predictor of environmental attitudes.

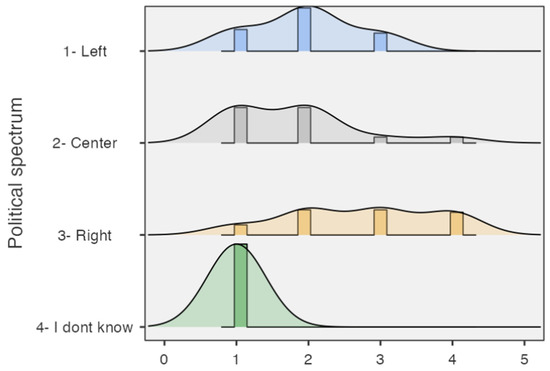

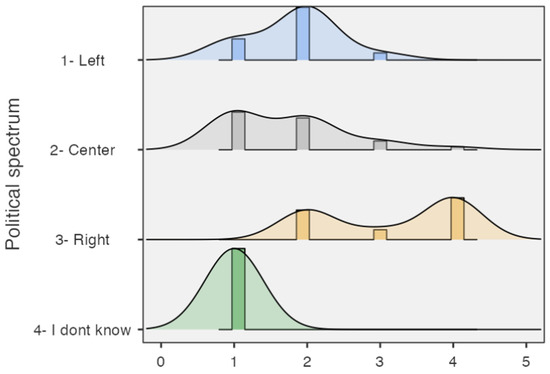

Figure 4 shows, based on the political spectrum, that supporters on the far right seem to agree that climate scientists have a financial interest in denying climate change, i.e., that scientists are paid to spread false articles about the climate crisis being real. This belief fits into what several authors call “climate change conspiracy beliefs” or “motivated denial,” in which ideological and identity factors outweigh scientific evidence. Studies in the US, UK, and even some recent work in Europe show that conservative/right-wing political orientation correlates with a greater likelihood of denying the existence or severity of climate change [35,36]. In Figure 5, we can see the level of trust participants have in reputable scientific organizations such as NASA and the IPCC.

Figure 4.

How Responses Are Spread Out Based on the Political Spectrum. “I think there are monetary interests on the part of scientists who study the climate”. The numbers 0 to 5 in the graph refer to the Likert scale where lower values are “I completely disagree” and higher values are “I completely agree”. (Source: made by authors).

Figure 5.

How Responses Are Spread Out Based on the Political Spectrum “I believe that entities that study the climate, such as NASA, NOAA, and the IPCC, are reliable from a scientific point of view”. The numbers 0 to 5 in the graph refer to the Likert scale where lower values are “I completely disagree” and higher values are “I completely agree”. (Source: made by authors).

Our findings also indicate that right-leaning participants expressed more distrust toward major scientific institutions such as the IPCC and NASA, despite their global reputation as highly credible organizations. This pattern is consistent with previous research showing that political conservatism is linked to selective skepticism toward scientific authorities, especially when their conclusions imply regulatory action or economic transformation. Such distrust is often tied to anti-elitist narratives and conspiracy-like beliefs, which portray international scientific bodies as politically or financially motivated. These perceptions represent a barrier for effective climate communication and highlight the importance of transparency and tailored engagement strategies to bridge trust gaps [37].

Through Figure 6, we see that students who identify with right-wing politics seem to agree that it is impossible to make predictions or climate scenarios for the future, showing a lack of understanding of the differences between climate and weather. It is important to clarify the distinction between weather and climate. While weather refers to short-term atmospheric conditions and is inherently difficult to predict beyond approximately 10 days, climate refers to long-term statistical patterns and averages that span decades. Climate models, based on well-established physical principles, allow scientists to project future scenarios depending on greenhouse gas emissions. Numerous studies and the IPCC reports demonstrate with very high confidence that these models have successfully predicted past climate trends, including global temperature rise [23]. Therefore, contrary to the misconception that “if we cannot predict next week’s weather, we cannot predict future climate,” current science provides strong evidence that projections of long-term climate scenarios are both reliable and essential for policy and adaptation.

Figure 6.

How Responses Are Spread Out Based on the Political Spectrum “Predicting the weather for the next week is difficult; predicting climate scenarios for the future is impossible.” The numbers 0 to 5 in the graph refer to the Likert scale where lower values are “I completely disagree” and higher values are “I completely agree”. (Source: made by authors).

4. Conclusions

This study offers preliminary insights into factors potentially associated with climate change skepticism among members of a Portuguese university, suggesting possible influences of gender, religion, and political orientation. Men appeared somewhat more likely than women to express climate change skepticism, which may reflect broader societal influences shaping environmental perceptions—consistent with previous findings indicating that men tend to downplay ecological risks. Religious affiliation also seemed to play a role: Catholics showed mixed responses, leaning slightly toward doubt, while Evangelical and Muslim participants tended to express greater skepticism, particularly regarding human causation and the reliability of scientific institutions. In contrast, participants with no religious affiliation were generally less likely to agree with skeptical statements, aligning with research suggesting higher trust in science among non-religious individuals. Political orientation also appeared relevant: right-leaning respondents tended to downplay human influence on climate change and to view scientists as motivated by political or financial interests, whereas left-leaning participants showed greater trust in science and stronger recognition of anthropogenic causes—reflecting broader global patterns of political polarization around climate issues.

Several limitations must be acknowledged when interpreting these findings. The study was conducted within a single university, limiting the generalizability of the results. Institutional culture, student demographics, and regional factors may have shaped the responses observed here. The cross-sectional design prevents causal inference—while associations were identified, directionality cannot be established. The relatively small sample size (N = 89), especially in subgroup analyses by religion or political orientation, reduces statistical power and increases uncertainty. Furthermore, the quantitative design did not capture the deeper reasoning or motivations underlying participants’ beliefs; qualitative methods such as interviews or focus groups could provide richer contextual understanding. At some point, part of the original file containing the statistical data was lost, which may have affected the study and its robustness. As a sensitivity analysis, exact Mann–Whitney U tests were conducted to verify the robustness of the results obtained with the approximate method. The conclusions remained unchanged. Additionally, permutation-based tests of median differences yielded consistent outcomes, supporting the stability of the findings.

Future research should therefore explore these relationships in larger and more diverse samples, incorporating additional variables such as field of study, socioeconomic status, prior climate knowledge, and trust in institutions.

Overall, the study suggests that climate change skepticism is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon influenced by cultural, religious, and political factors. Universities can play an important role in addressing these patterns—not only through targeted education on climate science but also by integrating environmental literacy across curricula. Tailored communication strategies that acknowledge group-specific perspectives may help promote informed engagement, counter misinformation, and foster critical thinking, reinforcing universities as key spaces for scientific dialogue and sustainable problem-solving.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R.; Methodology, R.R. and I.R.; Validation, M.J.R. and I.R.; Data curation, R.R. and M.J.R.; Visualization, M.J.R.; Supervision, I.R.; Funding acquisition, M.J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia within the Project Scope: UID/05777/2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics committee of the Polytechnic Institute of Bragança (Approval Code: 640051; Approval Date: 5 July 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bretter, C.; Schulz, F. Why focusing on “climate change denial” is counterproductive. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2217716120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornsey, M.J.; Harris, E.A.; Bain, P.G.; Fielding, K.S. Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynas, M.; Houlton, B.Z.; Perry, S. Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 114005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermak, A. Scientific Consensus NASA Science. NASA. 2022. Available online: https://science.nasa.gov/climate-change/scientific-consensus/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Bardon, A. The Truth About Denial: Bias and Self-Deception in Science, Politics, and Religion; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Maslin, M. The Five Corrupt Pillars of Climate Change Denial. The Conversation. 2019. Available online: http://theconversation.com/the-five-corrupt-pillars-of-climate-change-denial-122893 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Oreskes, N.; Conway, E.M. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming; Bloomsbury Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Björnberg, K.E.; Karlsson, M.; Gilek, M.; Hansson, S.O. Climate and environmental science denial: A review of the scientific literature published in 1990–2015. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, R.; Vaz, P.; Rodrigues, M.J. Climate denialism on social media: Qualitative analysis of comments on Portuguese newspaper Facebook pages. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlova, N.A.; Fisher, K.E. A Social Diffusion Model of Misinformation and Disinformation for Understanding Human Information Behaviour Informationr.net. 2013. Available online: https://informationr.net/ir/18-1/paper573.html?fbclid=IwAR1DCcwre3zlnLMHrVROXfTovYtBvOrYPtHFzJhElqtzGFJXpsi3oIrJA_A (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Del Vicario, M.; Bessi, A.; Zollo, F.; Petroni, F.; Scala, A.; Caldarelli, G.; Stanley, E.H.; Quattrociocchi, W. The spreading of misinformation online. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, N. Oil and Gas Giants Spend Millions Lobbying to Block Climate Change Policies [Infographic] Forbes. 2019. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2019/03/25/oil-and-gas-giants-spend-millions-lobbying-to-block-climate-change-policies-infographic/?sh=74babaf17c4f (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Treen, K.M.D.; Williams, H.T.P.; O’Neill, S.J. Online misinformation about climate change. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2020, 11, e665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cologna, V.; Kotcher, J.; Mede, N.G.; Besley, J.; Maibach, E.W.; Oreskes, N. Trust in climate science and climate scientists: A narrative review. PLoS Clim. 2024, 3, e0000400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohr, J. Reporting on climate change: A computational analysis of U.S. newspapers and sources of bias, 1997–2017. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 61, 102038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, A.; Nagler, J.; Tucker, J. Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCright, A.M. The effects of gender on climate change knowledge and concern in the American public. Popul. Environ. 2010, 32, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCright, A.M.; Dunlap, R.E. Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Glob. Environ. Change 2011, 21, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, W.; Berry, E.; Kreider, L.B. Religion and climate change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2018, 43, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haltinner, K.; Sarathchandra, D. The nature and nuance of climate change skepticism in the United States. Rural Sociol. 2021, 86, 673–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.J.; Maki, A. Climate change belief, sustainability education, and political values: Assessing the need for higher-education curriculum reform. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.M.; Markowitz, E.M.; Howe, P.D.; Ko, C.-Y.; Leiserowitz, A.A. Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausfather, Z.; Drake, H.F.; Abbott, T.; Schmidt, G.A. Evaluating the performance of past climate model projections. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2019GL085378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Mifsud, M.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Nagy, G.J.; Veiga Ávila, L.; Salvia, A.L. Climate change scepticism at universities: A global study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, A.G.; Noordzij, K.; de Koster, W.; van der Waal, J. The educational divide in climate change attitudes: Understanding the role of scientific knowledge and subjective social status. Glob. Environ. Change 2024, 86, 102851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A.R.; Ballew, M.T.; Naiman, S.; Schuldt, J.P. Race, Class, Gender and Climate Change Communication Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; Available online: https://oxfordre.com/climatescience/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228620-e-412 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Remsö, A.; Bäck, H.; Renström, E.A. Gender differences in climate change denial in Sweden: The role of threatened masculinity. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1450230. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11673762/ (accessed on 24 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; McCright, A.M. Explaining Gender Differences in Concern about Environmental Problems in the United States. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2012, 25, 1067–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRRI. The Faith Factor in Climate Change: How Religion Impacts American Attitudes on Climate and Environmental Policy PRRI. 2023. Available online: https://www.prri.org/research/the-faith-factor-in-climate-change-how-religion-impacts-american-attitudes-on-climate-and-environmental-policy (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Francis, P. Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home Vatican.va. 2015. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si.html (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Alper, B. Religious Groups’ Views on Climate Change Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. 2022. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2022/11/17/religious-groups-views-on-climate-change/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Leka, J.; Furnham, A. Correlates of climate change skepticism. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1328307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Feygina, I. Responding to Climate Change Skepticism and the Ideological Divide. Mich. J. Sustain. 2017, 5. Available online: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/mjs/12333712.0005.102?view=text;rgn=main (accessed on 24 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. The Politics of Climate Pew Research Center. 2016. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2016/10/04/the-politics-of-climate/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Gregersen, T.; Doran, R.; Böhm, G.; Tvinnereim, E.; Poortinga, W. Political Orientation Moderates the Relationship Between Climate Change Beliefs and Worry About Climate Change. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1573–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, E.Y.; Faria, A.A. Political ideology and climate change-mitigating behaviors: Insights from fixed world beliefs. Glob. Environ. Change 2022, 72, 102440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, Z.P.; Hobolt, S.B. Going Against the Grain: Climate Change as a Wedge Issue for the Radical Right. Comp. Political Stud. 2024, 23, 1733–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).