Multilevel Factors for (Non)Reporting Intimate Partner Violence: The Case of Bulgaria

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What are the factors that deter victims of intimate partner violence in Bulgaria from reporting to the police?

- RQ2: What are the factors that may prompt victims to disclose intimate partner violence?

- RQ3: Who do victims of intimate partner violence first turn to for help?

2. Literature Overview

3. Materials and Methods

Ethical Considerations

4. Results

4.1. Macro-Level Factors

4.1.1. Legal Framework

“It happened in a hurry, these laws had to be passed […] Yes, there was such an attempt to legalize some kind of intimate relationship, but this definitely creates some chaos […] how it is defined, when does their relationship start to be intimate, there are definitely ambiguities there that I would say should be reviewed.”(iDI-32)

“So, people, victims, first look for their close circle, then they turn to the non-governmental sector, to consultants like me, I’m a lawyer, I give legal advice, and only then, when we’re talking about severe physical violence, do they turn to the police. This lady had not contacted the police and as she said: ‘You are the first one who does not judge me and understands why I did not contact the police.’ And I understand her because these women think like that: If I go and accuse him, they will arrest him, they will try him, they will put him in prison, he is the father of my child, my child will grow up without a father, a father in prison, it will be a stigma, a mark for my child.”(iDI-11)

“We also have a discrepancy between the definitions in the PDVA and the Criminal Code, some things that are violence under the PDVA are not violence under the Criminal Code and vice versa. And accordingly, some of the subjects who can be protected under the PDVA cannot seek protection under the Criminal Code and vice versa.”(iDI-22)

“That is, we do not have this connection. For example, for the prosecutor, after a protection order for domestic violence has been issued against an individual, to assess whether a crime has been committed and whether state intervention is required or no […]”(iDI-22)

4.1.2. Culture Norms

“Unfortunately, I believe it has yet to be recognized as a societal problem. Yes, society reacts violently and sharply in individual cases, but it does not recognize it as a larger general problem, but rather as an individual problem. Including the polar reactions in some cases: she is a victim, helpless, but she deserved it. So, society distances itself, gives its verdict, but the problem remains for the person and, at most, in the family, and in the narrow circle of the family, not in the extended family.”(Participant 2, FG-05)

“We work in a small town, and admitting that you are a victim of violence is not always acceptable in society. In most cases, you will be accused, and people will look for a reason in your actions rather than the violence itself. This leads to the victim’s own limitation, as she limits herself without disclosing it or seeking help.”(Participant 12, FG-02)

4.2. Meso Level Factors

4.2.1. The Role of Family and Community

“…the expression of the patriarchal model—a woman should serve her husband, care for the children and the home… the man should take care of the financial aspect. These understandings have been kept since the past.”(iDI-23)

“Even relatives are reluctant to help because […] they have values that are by no means bad, but sometimes they simply work against the victim, because the main value is the family, the harmony in the family, the peace of the children.”(iDI-22)

“[…] they say nothing special happened, he was just sniffing me a little.”(iDI-10)

“I think there is a certain tolerance for milder forms of violence that are perceived as completely normal…”(iDI-30)

4.2.2. Institutional Response and Access to Protection and Support Services

“Sometimes the victim complains that when she went the first time, she was not paid attention to or was told that there is no point just to do paperwork, file a complaint, and then nothing could be done about this complaint.”(iDI-22)

“It is clear that half of the administrative districts in the country, no matter what you do, do not have crisis centers. In other words, you cannot escape. However, the other 50%, not all crisis centers are full, which means that victims do not know about them and cannot reach them.”(iDI-21)

“The other option is for them [the victims. a.n.] to leave home themselves and stay in a crisis center, but there are only two in Sofia. However, not all cities have shelters, where you can urgently spend the night and escape somewhere […] I will just tell you that the crisis center in Sofia has eight beds. Is that enough?”(iDI-50)

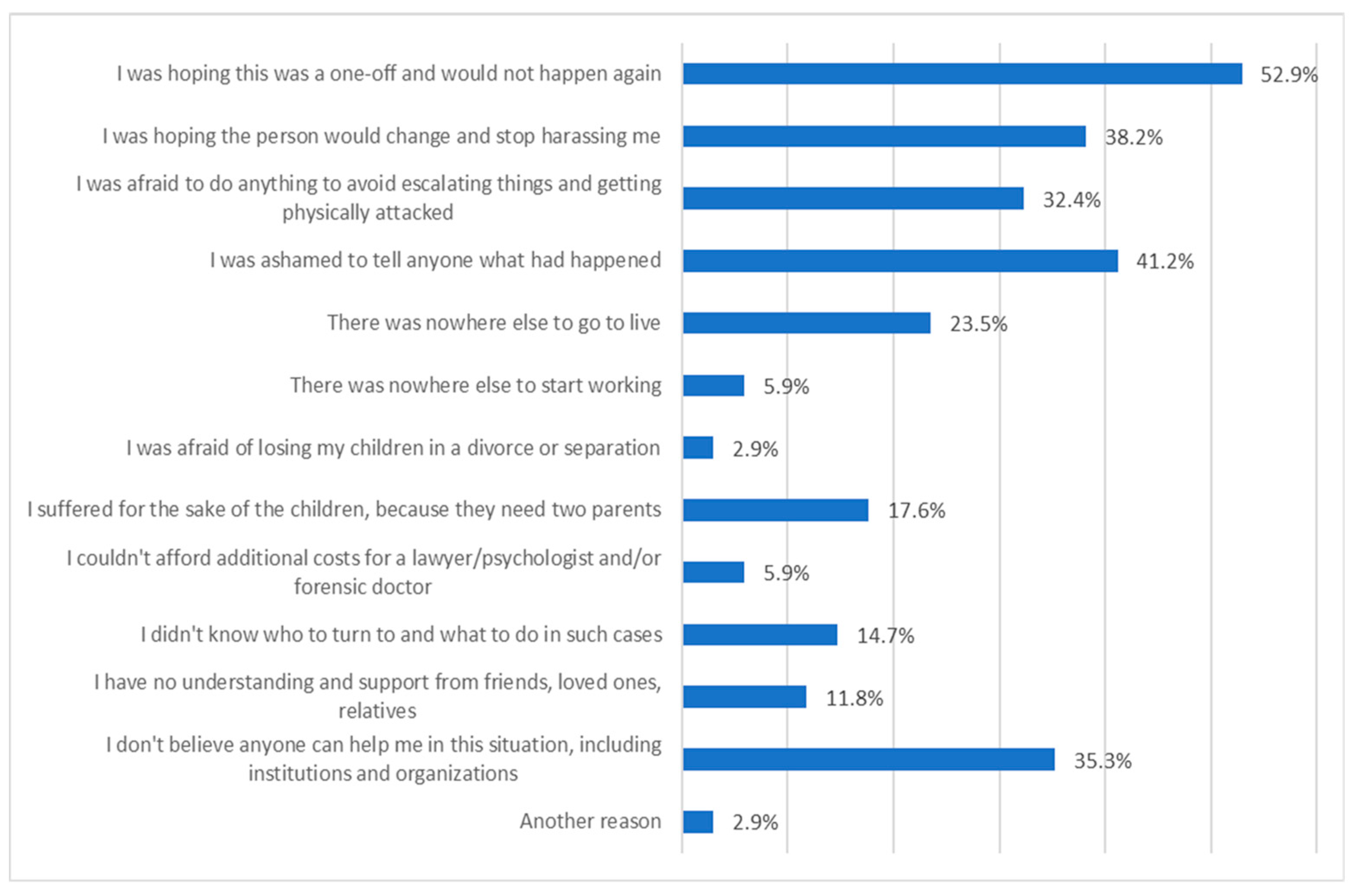

4.3. Micro Level Factors

4.3.1. Hope It Is a One-Time Act and Will Not Happen Again

“However, my experience reveals that it never goes away and is never a one-time incident; it merely re-peats itself at some later time, with the “detonator capsule” being any form of struggle or disagreement in the home, or in the couple’s relationship.”(Participant 09, FG-06)

4.3.2. Shame and Guilt in the Victim

“Are they silent because of upbringing? Many people are silent for different reasons. Even more so, in my opinion, in small towns they are silent out of shame, so that the neighbors don’t find out. They don’t want people to talk about them.”(Participant 13, FG-01)

“Very often, women who have suffered blame themselves for certain negative reactions, including physical and psychological violence against them by their husbands.”(iDI-11)

4.3.3. Fear of Escalation of Violence and Lack of Trust in Institutions

“Out of fear, out of dependence on the abuser, but they don’t report it. We check for previous reports, and there are none. She didn’t report it at all, but she was a victim of violence the whole time.”(Participant 07, GF-02)

“She is afraid to file a report because, for example, the district police officer who will come is a friend of her husband. Acquaintances in small towns play a role. How is she supposed to file a report?”(Participant 06, FG-06)

“A large proportion of victims of domestic violence do not believe that anyone would help them, which means they do not trust the police, the prosecutor’s office, or the court.”(Participant 09, FG-06)

4.3.4. For the Sake of Protecting Children

“We are currently working on a case in which the woman suffered domestic violence for many years but did not leave and did not report it for the sake of the children […]. And for this reason, the woman preferred to remain silent for years and to endure absolutely all the beatings that happened at different times of the day.”(Participant 12, FG-01)

4.3.5. Dependence (Emotional and/or Economic) on the Abuser

“… it happens that very often they decide to return to the abuser to live in whatever kind of abuse it is, because they have nowhere to go. She is economically dependent on him. […] Emotional attachment to the abuser is also a reason. Especially if they have lived together for years. The victim cannot even decide without his participation. She cannot take any step without his intervention. And she cannot make a decision on her own.”(Participant 8, FG-01)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FG | Focus group |

| iDI | In-depth interview |

| IPV | Intimate partner violence |

| PDVA | Protection from domestic violence act |

Appendix A

| iDI 10—police officer, female, 41, conducted on 2 October 2024 |

| iDI 11—police officer, female, 48, conducted on 10 October 2024 |

| iDI 12—police officer, male, 42, conducted on 10 October 2024 |

| iDI 13—prosecutor, male, 30, conducted on 14 October 2024 |

| iDI 14—advisor to a minister, female, 48, conducted on 10 October 2024 |

| iDI 20—NGO, male, 37, conducted on 13 August 2024 |

| iDI 21—NGO, female, 52, conducted on 15 August 2024 |

| iDI 22—judge, female, 42, conducted on 4 September 2024 |

| iDI 23—NGO, female, 45, conducted on 12 September 2024 |

| iDI 24—police officer, male, 46, conducted on 26 September 2024 |

| iDI 30—NGO, female, 32, conducted on 19 August 2024 |

| iDI 31—NGO, female, 30, conducted on 19 August 2024 |

| iDI 32—state institution, female, 45, conducted on 20 August 2024 |

| iDI 33—NGO, male, 61, conducted on 20 August 2024 |

| iDI 34—state institution, female, 58, conducted on 3 October 2024 |

| iDI 40—politician, female, 51, conducted 20 September 2024 |

| iDI 41—international organization, female, 47, conducted on 25 September 2024 |

| iDI 42—NGO, female, 40, conducted on 25 September 2024 |

| iDI 43—NGO, female, 60, conducted on 27 September 2024 |

| iDI 44—journalist, female, 35, conducted on 30 September 2024 |

| iDI 45—politician, female, 47, conducted on 2 October 2024 |

| iDI 50—lawyer, female, 45, conducted on 7 August 2024 |

| iDI 51—investigator, female, 50, conducted 20 September 2024 |

| iDI 52—judge, female, 45, conducted on 26 September 2024 |

| iDI 53—prosecutor, female, 48, conducted on 16 October 2024 |

| iDI 61—trade unionist, female, 59, conducted on 27 January 2025 |

Appendix B

| Focus group 1, two moderators, conducted on 11 September 2024 | Participant 1—prosecutor, female, 51 |

| Participant 2—prosecutor, male, 39 | |

| Participant 3—police officer, female, 44 | |

| Participant 4—police officer, female, 42 | |

| Participant 5—police officer, male, 49 | |

| Participant 6—police officer, female, 49 | |

| Participant 7—prosecutor, female, 41 | |

| Participant 8—police officer, female, 52 | |

| Participant 9—pros87ecutor, male, 39 | |

| Participant 10—prosecutor, male, 42 | |

| Participant 11—police officer, male, 40 | |

| Participant 12—social worker, NGO, female, 52 | |

| Participant 13—social worker, NGO, female, 40 | |

| Participant 14—social worker, NGO, female, 44 | |

| Focus group 2, two moderators, conducted on 11 September 2024 | Participant 1—police officer, female, 34 |

| Participant 2—prosecutor, male, 35 | |

| Participant 3—prosecutor, female, 49 | |

| Participant 4—prosecutor, female, 44 | |

| Participant 5—investigator, female, 62 | |

| Participant 6—investigator, female, 48 | |

| Participant 7—police officer, male, 41 | |

| Participant 8—police officer, male, 45 | |

| Participant 9—police officer, male, 50 | |

| Participant 10—police officer, female, 52 | |

| Participant 11—social worker, NGO, female, 29 | |

| Participant 12—social worker, NGO, female, 48 | |

| Participant 13—social worker, NGO, female, 59 | |

| Focus group 3, two moderators, conducted on 17 September 2024 | Participant 1—prosecutor, female, 43 |

| Participant 3—judge, male, 34 | |

| Participant 4—social worker, NGO, female, 24 | |

| Participant 5—prosecutor, female, 31 | |

| Participant 6—police officer, male, 54 | |

| Participant 7—police officer, male 50 | |

| Participant 8—prosecutor, male, 30 | |

| Participant 10—social worker, Agency for Social Assistance, female, 45 | |

| Participant 11—social worker, NGO, female, 25 | |

| Participant 12—judge, female, 41 | |

| Focus group 4, two moderators, conducted on 17 September 2024 | Participant 1—social worker, NGO, female, 25 |

| Participant 2—social worker, NGO, female, 28 | |

| Participant 3—prosecutor, male, 40 | |

| Participant 4—prosecutor, male, 31 | |

| Participant 5—social worker, Agency for Social Assistance, female, 52 | |

| Participant 6—prosecutor, male, 35 | |

| Focus group 5, two moderators, conducted on 18 September 2024 | Participant 1—social worker, NGO, female, 33 |

| Participant 2—social worker, NGO, female, 47 | |

| Participant 5—social worker, Agency for Social Assistance, female, 60 | |

| Participant 6—prosecutor, female, 38 | |

| Participant 8—prosecutor, female, 44 | |

| Participant 9—prosecutor, female, 36 | |

| Participant 11—prosecutor, female, 40 | |

| Participant 12—police officer, male, 45 | |

| Focus group 6, two moderators, conducted on 18 September 2024 | Participant 1—NGO, female, 40 |

| Participant 2—judge, female, 38 | |

| Participant 4—police officer, female, 45 | |

| Participant 5—police officer, female, 56 | |

| Participant 6—NGO, female, 43 | |

| Participant 8—prosecutor, female, 42 | |

| Participant 9—prosecutor, male, 34 | |

| Participant 10—prosecutor, male, 30 | |

| Participant 11—police officer, female, 48 | |

| Participant 12—social worker, NGO, female, 36 | |

| Participant 13—social worker, NGO, female, 38 | |

| Participant 14—social worker, Agency for Social Assistance, female, 53 |

Appendix C

| Sample, Nationally Representative Survey | NSI, Population Census | |

| 18–24 years old | 9.1% | 6.9% |

| 25–29 years old | 5.4% | 5.6% |

| 30–39 years old | 19.7% | 15.4% |

| 40–49 years old | 16.1% | 18.0% |

| 50–59 years old | 21.5% | 17.2% |

| 60 years and older | 28.1% | 36.9% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 49.8% | 47.4% |

| Female | 50.1% | 52.6% |

| Other | 0.1% | |

| Education: | ||

| Primary education | 8.8% | 19.0% |

| Secondary education (general and vocational) | 55.4% | 52.0% |

| Higher education | 35.5% | 29.0% |

| I do not want to answer | 0.3% | |

| Place of residence | ||

| Capital | 19.7% | 18.5% |

| Regional city | 38.9% | 33.1% |

| Small town | 21.2% | 21.5% |

| Village | 20.2% | 26.8% |

| Region of a settlement | ||

| Blagoevgrad | 2.4% | 4.5% |

| Burgas | 5.1% | 5.8% |

| Varna | 6.5% | 6.6% |

| Veliko Tarnovo | 4.4% | 3.2% |

| Vidin | 1.1% | 1.2% |

| Vratsa | 2.7% | 2.3% |

| Gabrovo | 2.0% | 1.5% |

| Dobrich | 2.7% | 2.3% |

| Kardzhali | 2.5% | 2.2% |

| Kyustendil | 2.2% | 1.7% |

| Lovech | 2.6% | 1.8% |

| Montana | 2.2% | 1.9% |

| Pazardzhik | 1.7% | 3.5% |

| Pernik | 0.5% | 1.8% |

| Pleven | 4.4% | 3.5% |

| Plovdiv | 9.8% | 9.7% |

| Razgrad | 1.3% | 1.6% |

| Russe | 3.2% | 3.0% |

| Silistra | 2.7% | 1.5% |

| Sliven | 2.6% | 2.6% |

| Smolyan | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| Sofia-city | 19.7% | 19.4% |

| Sofia-area | 0.7% | 3.6% |

| Stara Zagora | 4.0% | 4.5% |

| Targovishte | 2.4% | 1.5% |

| Haskovo | 3.6% | 3.3% |

| Shumen | 3.2% | 2.3% |

| Yambol | 2.3% | 1.7% |

| 1 | The case, known as the “Deborah case,” is about an 18-year-old woman who was attacked by a masked man who she recognizes as her former intimate partner in her home in the summer of 2023. A hit to the face knocked the woman unconscious, and the perpetrator then cut off all of the victim’s hair and slashed her body with a knife. The court case is still ongoing. This case is also included in the speech of the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, in her address in 2024 for the Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. |

| 2 | The research project “Violence against Women: Typologies, Economic and Social Consequences” is implemented by research teams from the University of National and World Economy (base organization), through the Center for Sociological and Psychological Research at the Department of Economic Sociology, and Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski” (partner organization), through the Faculty of Economics, within the framework of the Competition for Funding of Fundamental Scientific Research—2023 of the Bulgarian National Science Fund (Grant agreement № KП-06-H75/2 from 7 December 2023). |

References

- World Health Organization. Understanding and Addressing Violence Against Women: Intimate Partner Violence. 2012. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/77432 (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- UN Women. Types of Violence against Women and Girls. 2024. Available online: https://unwomen.org.au/types-of-violence-against-women-and-girls/ (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Sangeetha, J.; Mohan, S.; Hariharasudan, A.; Nawaz, N. Strategic Analysis of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) and Cycle of Violence in the Autobiographical Text—When I Hit You. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanesi, C.; Tomasetto, C.; Guardabassi, V. Evaluating Interventions with Victims of Intimate Partner Violence: A Community Psychology Approach. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018: Global, Regional and National Prevalence Estimates for Intimate Partner Violence Against Women and Global and Regional Prevalence Estimates for Non-Partner Sexual Violence Against Women; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022256 (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Stöckl, H.; Devries, K.; Rotstein, A.; Abrahams, N.; Campbell, J.; Watts, C.; Moreno, C.G. The global prevalence of intimate partner homicide: A systematic review. Lancet 2013, 382, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juarros-Basterretxea, J.; Fernández-Álvarez, N.; Torres-Vallejos, J.; Herrero, J. Perceived Reportability of Intimate Partner Violence against Women to the Police and Help-seeking: A National Survey. Psychosoc. Interv. 2024, 33, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FRA; EIGE; Eurostat. EU gender-based violence survey—Key results. In Experiences of Women in the EU-27; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Institute. Survey on Gender-Based Violence EU-GBV, 2021. 2022. Available online: https://www.nsi.bg/sites/default/files/files/pressreleases/GBV_2021_en.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Makeva, B. Domestic Violence in Bulgaria—Statistics and Facts. Legis. Protection. NBU Law J. 2024, 20, 95–114. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelaurain, S.; Graziani, P.; Monaco, G.L. Intimate Partner Violence and Help-Seeking. A Systematic Review and Social Psychological Tracks for Future Research. Eur. Psychol. 2017, 22, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.R.; Ravi, K.; Voth Schrag, R.J. A Systematic Review of Barriers to Formal Help Seeking for Adult Survivors of IPV in the United States, 2005–2019. Trauma Violence Abus. 2020, 22, 1279–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heron, R.L.; Eisma, M.C. Barriers and facilitators of disclosing domestic violence to the healthcare service: A systematic review of qualitative research. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, 612–630. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, E. Unreported cases of domestic violence against women: Towards an epidemiology of social silence, tolerance, and inhibition. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2004, 58, 536–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodson, A.; Hayes, B.E. Help-Seeking Behaviors of Intimate Partner Violence Victims: A Cross-National Analysis in Developing Nations. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 36, NP4705–NP4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Ferraresso, R. Factors Associated With Willingness To Report Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) to Police in South Korea. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 37, NP10862–NP10882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, K.; Cardenas, I.; Steiner, J.J.; Khetarpal, R. Women’s Help-Seeking in China and Papua New Guinea: Factors That Impact Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.-Y.; Wachter, K.; Kappas, A.; Brown, M.L.; Messing, J.T.; Bagwell-Gray, M.; Jiwatram-Negron, T. Patterns of Help-seeking Strategies in Response to Intimate Partner Violence: A Latent Class Analysis. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 37, NP6604–NP6632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoshal, R.; Patil, P.; Sinha, I.; Gadgil, A.; Nathani, P.; Jain, N.; Ramasubramani, P.; Roy, N. Factors associated with help-seeking by women facing intimate partner violence in India: Findings from National Family Health Survey-5 (2019–2021). BMC Glob. Public Health 2024, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravi, K.E.; Leat, S.R.; Voth Schrag, R.; Moore, K. Factors Influencing Help-seeking Choices Among Non-Service-Connected Survivors of IPV. J. Fam. Violence 2024, 39, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, K.; Chavdarova, V.; Tasevska, D. Research into the Ethnopsychological and Cultural Characteristics of the Bulgarian Family in the Context of Gender-Based Violence; Faber: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2021. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev, I. Some specific features of the judicial proceedings for protection from domestic violence. Contemp. Law 2016, 29, 94–107. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Goleva, P. Domestic violence—Legal issues. Prop. Law 2019, 45–549. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Rangelova, R. Policies against domestic violence in a comparative international perspective and conclusions for Bulgaria. In The Reform for Protection from Domestic Violence; Institute of State and Law, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2024; pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kostadinova, R. The reform of protection against domestic violence and Bulgarian criminal law. In The Reform of Protection Against Domestic Violence: Collection of Reports from a Scientific and Applied Conference, Proceedings of the Sofia Scientific and Applied Conference: The Reform of Protection Against Domestic Violence, Sofia, Bulgaria, 22 November 2023; Institute of State and Law, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2024. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Azorin, J. Mixed methods research: An opportunity to improve our studies and our research skills. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2016, 25, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for Health Improvement & Disparities. Mixed Methods Study. GOV.UKp, 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/mixed-methods-study (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985; pp. 289–331. [Google Scholar]

- Kish, L. A Procedure for Objective Respondent Selection within the Household. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1949, 44, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoncheva, A. Overview of the Changes in the Domestic Violence Act and the Gaps in Their Implementation. Bulgarian Platform—European Women’s Lobby. 2024. Available online: https://womenlobbybulgaria.org/domestic-violence-law-changes-effect/ (accessed on 21 June 2025). (In Bulgarian).

- Stamenkov, R.; Petrunov, G. The vulnerability of migrants from Bulgaria to human trafficking for labor exploitation. Dve Domov. 2025, 61, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrunov, G. Prostitution and Public Policy in Post-Socialist Bulgaria. Croat. Political Sci. Rev./Politička Misao Časopis Za Politol. 2023, 60, 11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Petrunov, G. Public Attitudes Towards Prostitution in Bulgaria in the Context of Social and Legal Neglection. Sociologija 2024, 66, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, I.M. Economic, Situational, and Psychological Correlates of the Decision-Making Process of Battered Women. Fam. Soc. 1992, 73, 168–176. [Google Scholar]

- Heise, L.; Ellsberg, M.; Gottemoeller, M. Ending Violence Against Women; Population Reports Series L, No. 11; Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Petrunov, G. Cultural, Ideological and Structural Conditions Contributing to the Sustainability of Violence Against Women: The Case of Bulgaria. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gover, A.R.; Welton-Mitchell, C.; Belknap, J.; Deprince, A.P. When Abuse Happens Again: Women’s Reasons for Not Reporting New Incidents of Intimate Partner Abuse to Law Enforcement. Women Crim. Justice 2013, 23, 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA). Violence Against Women: An EU-Wide Survey. 2014. Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2014/violence-against-women-eu-wide-survey-main-results-report (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Heron, R.L.; Eisma, M.; Browne, K. Why Do Female Domestic Violence Victims Remain in or Leave Abusive Relationships? A Qualitative Study. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2022, 31, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.; Kearns, M.C.; McIntosh, W.L.; Estefan, L.F.; Nicolaidis, C.; McCollister, K.E.; Gordon, A.; Florence, C. Lifetime economic burden of intimate partner violence among U.S. adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahenge, B.; Stöckl, H. Understanding Women’s Help-Seeking with Intimate Partner Violence in Tanzania. Violence Against Women 2020, 27, 937–951. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petrunov, G. Multilevel Factors for (Non)Reporting Intimate Partner Violence: The Case of Bulgaria. Societies 2025, 15, 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15100265

Petrunov G. Multilevel Factors for (Non)Reporting Intimate Partner Violence: The Case of Bulgaria. Societies. 2025; 15(10):265. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15100265

Chicago/Turabian StylePetrunov, Georgi. 2025. "Multilevel Factors for (Non)Reporting Intimate Partner Violence: The Case of Bulgaria" Societies 15, no. 10: 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15100265

APA StylePetrunov, G. (2025). Multilevel Factors for (Non)Reporting Intimate Partner Violence: The Case of Bulgaria. Societies, 15(10), 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15100265