1. Introduction

Young people are a group that has been excluded from studies on crime and insecurity, even though they are in a critical phase for the development of their identity and the adoption of a place in society [

1]. A study in Brussels reported that insecurity affects their emotional connection with neighborhood spaces and their feelings of belonging, as well as aspects of psychosocial development, including socialization, identity construction, and citizenship. Their relationship to space allows them to acquire autonomy, learn how to negotiate conflicts with different groups, and manage risks [

2]. It is necessary to modify the representation of young people as “passive victims” of crime and recognize their capacity for agency, without dismissing the need to modify structural living conditions to promote security in their communities [

3]. Recovering their voices allows the design of inclusive public policies on public security.

Youth are situated in the sense that they are linked to a certain geographic location; to economic, political, social, and cultural contexts; to a historical period; to the social space they inhabit; to identity affiliations; and to a network of intersubjective relationships with others. These social markers are articulated with dimensions such as gender and socioeconomic level. However, a significant sector of young people also find themselves “under siege” by multiple unfavorable conditions in which their life trajectories take place, such as the disruptive presence of organized crime in daily life [

4].

In Mexico, drug trafficking has become one of the types of organized crime that generates high levels of insecurity among young people due to its violent manifestations in communities. Murders associated with organized crime have increased in the last two decades. This violence has not been evenly distributed around the country. The conflict has intensified in stages and has erupted sporadically on the municipal level [

5]. A study in Mexicali reported that drug trafficking organizations also create feelings of insecurity in young people through their associations with sexual violence, feminicides, and disappearances [

6].

Young people have been one of the main victims of violence associated with drug trafficking. Various conditions favor the participation of young people in drug trafficking: deterioration in the structural conditions that favor effective incorporation into society, the weakening of public health, education, and employment institutions to meet the needs of a growing youth population, mistrust toward formal politics, and the tendency to value extralegal practices. Young people are victims of a system that negates and excludes them, where they face objective and symbolic difficulties in constructing meaningful lives in circumstances of greater stability. They become the “social refuse” on which drug traffickers operate [

7].

In addition to the risk of violence, drug trafficking represents another threat to young people: it exposes them to models of criminal activity, opportunities for involvement in crimes, and other problematic behaviors. Particularly in neighborhoods with insufficient informal social control, these types of activities are more likely because adults do not monitor or sanction them or provide alternative identities, employment, or economic independence [

8]. Conditions that encourage young people to get involved in drug trafficking include the lack of connection between education and the labor market, low wages coupled with the stimulus to consumerism, the crisis of family authority, and even the perception of selling drugs as a less morally problematic activity than crimes such as theft or robbery [

9].

Drug trafficking also creates a third threat to young people. A study in San Luis Potosí showed that drug use has various effects on communities: individual behavior becomes less predictable, aggressive and criminal behavior increases, and a variety of places are dedicated to drug use [

3]. These factors contribute to the intensification of violence and the reconfiguration of spaces through changes in social and personal practices as well as the perception of space [

10]. Considering the various psychosocial impacts that drug trafficking has on the daily lives of young people, this work aims to understand their perspective on the transformations generated in the neighborhood they live in, as well as their relationship with this space.

Theoretical Approach

This work is based on critical realism. This philosophy of science assumes the existence of a stratified, structured, and changing reality independent of our knowledge of it. This stratified reality has three levels. The first level contains the experiences observed by the actors (which are sought to be approximated by means of appropriate data collection methods); the second level includes both observable and non-observable events; and the third level contains the structural mechanisms that generate the events observed in the first level. The approach to these mechanisms is carried out through theoretical devices that allow us to understand the relationship between the problems and social, cultural, and historical conditions [

11]. In this section, the theoretical devices used to understand the experiences of young people with drug trafficking will be reviewed.

A criminal activity such as drug trafficking can be conceived from two logical levels (inseparable and interrelated): a structural problem and a problem experienced by agents. Furthermore, crime has a material dimension, since observable events occur related to the activity, and a symbolic dimension, since the agents make interpretations of crime, framed by historical, social, and political configurations [

12]. Agents respond to crime through symbols shared with their reference groups, collectively constructed from a social process of risk interpretation [

13,

14].

One of the means of this construction is the talk of crime, which encompasses conversations, comments, discussions, and/or narratives related to the problem. Talk of crime is fragmentary and repeated in numerous exchanges; it reinforces feelings of danger, insecurity, and worry. It not only has an expressive function, but it also produces meanings and explanations about crime and contributes to the reorganization of public space by defining social interactions and everyday protective strategies [

15]. When talking about crime, an interrelation occurs between the internal world and the external world, the agent and the structure, which results in a network of representations, emotions, and practices [

16].

Exploring young people’s agency in the face of crime requires understanding the links they make between their lived worlds, broader societal discourses, and their own felt internal narratives through a series of reflexive feedback loops. Such loops constitute narrative movements by individuals, from their internal worlds to their external worlds, transcending the boundaries between the internally felt world and the external world of social action, connecting thought, feeling, and action. During this process, young people appropriate, shape, or reconstruct discourses about crime that explicitly or implicitly invite them to shape actions in urban space [

17].

The practices linked to the talk of crime affect the construction of space as they shape the way in which it is used and appropriated. At the same time, space is constructed through representations that allow it to be interpreted and give meaning to practices in space [

18]. The living space of the inhabitants collapses as the space of crime in the city expands. The places and times for the activities of the inhabitants are reduced, their routes are altered, and even their expulsion from the spaces may be promoted [

19].

The talk of crime also allows an approach to the construction of drug trafficking as a public problem by young people, considering that it does not have the same meaning for all times, places, and social groups. Public problems have a cognitive dimension and a moral dimension. The first includes explanations about their origin and beliefs about their alterability. The second involves the recognition of the problem as generating social harm, which makes its resolution desirable. Within the public arena, not all social groups have the same access and power to define the problem, nor the same degree of responsibility in its resolution [

20]. It is, therefore, important to give voice to a group that is affected daily by drug trafficking but has not been sufficiently included in public security policies.

The purpose of this study is to understand, from the perspective of young people, the impact on communities of drug trafficking organizations in a city on the border between Mexico and the United States. The study seeks to identify, based on their talk of crime, the transformations perceived in their experience in the neighborhood, their spatial practices, the problems generated by drug trafficking, and the cultural changes in terms of meanings associated with drug trafficking, as well as the material and symbolic transformations of the neighborhood.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was carried out in the border city of Mexicali, the capital of the Mexican state of Baja California, located on the border with the U.S. state of California. The city’s population of more than one million has recently increased in response to internal and international migration. From January to September 2022, 31,907 foreign immigrants were rescued in Baja California [

21]. Among the state’s major economic activities are agriculture, livestock, trade, and services, as well as the “maquila” industry (a manufacturing operation or factory that temporarily imports materials and/or equipment for the production of goods). The local economy also benefits from tourism, which is not only recreational and cultural in nature but also economic as visitors come for shopping and medical care. The cultural and economic exchange also includes drug and arms trafficking, human trafficking, and sexual tourism.

Mexicali ranks second among Baja California municipalities in the incidence of numerous crimes. Over time, the most common crimes have been burglary, street robbery, family violence, and drug dealing. The neighborhoods with the greatest levels of crime have included parts of the city center but mainly the periphery [

22].

Recent years have seen various confrontations and murders linked to territorial disputes between cells of the Sinaloa Cartel after the fragmentation associated with the capture of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. The conflict between “Los Chapitos” and “Los Rusos” (in which the “Omegas” and the “Garibay” have also been involved) has been one of the most violent, affecting especially the safety of residents of the Valle de Mexicali, although the murders, confrontations, and attacks have also taken place in other parts of the city [

23]. There has been a recent increase in forced disappearances associated with organized crime, although these are underreported by the authorities [

24].

Lomnitz has pointed out that there are various subsystems of criminal economy, such as regional subsystems focused on the organization of retail sales, subsystems with a producer node, and subsystems with a smuggling node [

25]. In Mexicali, various subsystems coexist since, due to its border condition, a subsystem with a smuggling node may predominate, but there are also subsystems in the city focused on retail sales (where prison mafias may participate), and relationships are established with subsystems with production nodes that transport drugs to the northern border.

This study is part of a larger qualitative project examining young people’s perspective on the social construction of insecurity related to crime. This paper presents findings related to the influence of drug trafficking in neighborhoods of Mexicali. Forty-eight group interviews were conducted in 25 public schools (10 junior high schools, 10 high schools, and 5 universities). In order to enter the schools, the school authorities were initially approached to explain the purpose of the project and the conditions of participation. In case of acceptance, informed consent was requested from the parents. Within schools, students were contacted through counselors and teachers. The purpose of the study was explained to the students, and they were asked for informed assent. Afterwards, participants went to a space within the school where a sociodemographic data questionnaire could be applied individually, and then the group interview was conducted. It was considered more appropriate to contact young people in schools to talk with them in a safer space since the presence of criminal groups in their neighborhoods (or proximity to actors related to crime in their families or social networks) could limit their participation.

The purpose of the study was to understand their perspectives on insecurity associated with crime, regardless of whether they had suffered direct victimization or not or whether they participated in criminal activities. Group interviews were conducted due to limitations in access to students within schools, particularly in junior high schools and high schools. Group interviews were also conducted with university students to employ the same interview technique across educational levels. During the study, students were not asked directly if they had carried out criminal activities because participation in the group interview could be limited due to difficulties in maintaining confidentiality.

Saraví points out that in cities with high levels of social and economic inequality, there is a fragmented urban structure that is complemented by urban practices, interaction patterns, and territorial stigmas that favor the reciprocal exclusion of young people so that isolated and distant worlds coexist within the same city [

26]. This phenomenon also occurs in Mexicali as young people from different socioeconomic levels have a contrasting experience of the city in terms of the types of mobility, the places they visit, the level of crime in their neighborhoods, and access to public and private security services.

In this study, public schools located in neighborhoods where the crime rate was between the third and fourth quartiles during the period 2015–2020 were selected [

22]. The schools were public because the students have a different experience of the city than students in private schools as they tend to live in neighborhoods with higher levels of crime; they do not usually live in residential neighborhoods with higher levels of surveillance where entry is limited; they have less access to private security services both in the neighborhoods and in the schools; and there is a greater use of public transportation, or they usually walk to move through the city (although they also resort to moving by car for security reasons due to the extreme climate of the city and the limitations of the public transportation system).

In accordance with the principle of maximum diversity, an attempt was made to select schools with high levels of crime incidence located in different areas of the city (

Table 1). A limitation to this process is that in the city, the number of schools decreases as the educational level increases. For this reason, fewer universities were selected, which are concentrated in certain areas of the city (so there are not universities in all areas).

A stratified purposive sampling was used. The strata were formed by gender (in each school, group interviews were conducted with men and women, except for two schools where the group of men did not agree to participate or a mixed interview was conducted because there was not a sufficient number of participants) and educational level (as previously mentioned, the number of group interviews in universities was lower because there are more middle schools and high schools in the city). It is worth mentioning that this is a qualitative study where the sample does not intend to represent the population of students in public schools in the city but rather to develop a process of analytical generalization (in the sense of identifying conceptual categories that allow understanding the phenomenon of study in other places in the city or in other contexts).

The research protocol was presented to school authorities prior to fieldwork, and informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians of the students and from students who were legally of age. Informed assent was also obtained from minor students. The consent and assent described the nature of the study, the conditions of participation, the confidential character of participation, the audio recording of the interviews, and the mechanisms for protection of data; they also requested authorization for the publication of the findings.

A total of 48 group interviews were conducted, with groups of five to eight students (

Table 2). The main technique for data collection was the group interview. Although notes were obtained during the fieldwork, an ethnographic approach was not carried out due to the multiplicity of sites where the students came from and because the purpose of the study was focused on identifying patterns in the transformations associated with drug trafficking, which the young people perceived in their neighborhoods.

Prior to the interviews, participants completed a sociodemographic questionnaire in order to obtain data on sex, age, educational level, socioeconomic level, family type, and the perception of insecurity in the neighborhood (

Table 3). The group interview was carried out using a guide that covered the following topics: the concept of public insecurity, situations related to insecurity (in their neighborhood, at school, and in other parts of the city), perceived causes of insecurity, psychosocial consequences of insecurity, strategies for managing insecurity, and proposals for reducing insecurity in the city (

Appendix A). The questions in the guide were asked to the various members of the group. During the interview dynamic, the participants gave their point of view, which could coincide or contrast with the perspectives of the other members of the group. When a participant did not answer a question or there were aspects that needed clarification in the answer, follow-up questions were asked before moving on to the next question in the guide. The groups were homogeneous by educational level and sex (except for a mixed group due to access issues). This decision was made because we considered that young people of the same educational level shared similar experiences with drug trafficking based on their degree of autonomy in public space and because access to young people was facilitated by educational institutions at different school levels. In terms of gender, the separation of groups was due to the fact that the work is part of a broader project on public insecurity, and the participation of women in homogeneous groups was facilitated since they addressed issues related to sexual harassment in the streets and other forms of gender violence.

The interviews were conducted by two interviewers (first and third author). The interviewers were clinically trained psychologists with experience in conducting research interviews. Both were professors and researchers at a public university in the study site, have teenage children, and work with young people daily. Although the interviewers currently live in private residences and move around the city mainly by car, during their adolescence and a large period of their adult life, they lived in open neighborhoods and moved around by public transportation or walking. The interviewers had no prior knowledge of the participants. During the interviews, one interviewer took the lead (based on the gender of the participants), while the other took notes, helped facilitate the group process, and asked probing questions. This decision was made because the project addressed various situations associated with insecurity in the city in addition to drug trafficking. Specifically on the topic of gender violence in public spaces, the pilot study of the interview showed that the participation of young women was facilitated when the main interviewer was a woman. The interviews were conducted in educational spaces such as classrooms, computer labs, conference rooms, or libraries without the presence of school staff. The length of the interviews ranged from 40 min to 1 h.

Before describing the analysis process, it is necessary to mention some limitations of the method. One issue to consider is that the interviews were conducted in a group, in a school setting, by adults who were unfamiliar to the participants. These conditions may limit the depth of information provided, especially if young people are afraid to reveal the involvement of members of their social networks or themselves in drug trafficking or prefer to hide sensitive information about how drug trafficking operates and its consequences in the community. On the other hand, although the schools were located in neighborhoods with high levels of crime incidence, the young people who attended school could come from different neighborhoods and, therefore, be exposed to different levels of insecurity. In addition, group interviews allow an insight into young people’s perspectives through their talk about crime at a certain point in time, although crime incidence often fluctuates over time. Other data collection techniques, such as participant observation, would allow the perspectives of young people to be compared with the material conditions of criminality in the neighborhood over longer periods of time.

A thematic content analysis was conducted, which seeks to identify, analyze, and report patterns or themes in the data. The analysis was contextualist or based on critical realism as it recognizes the ways in which individuals give meaning to their experience and, at the same time, assumes that such meaning is limited by the sociocultural context and structural conditions. Although the themes identified are considered to be socially produced, they were not subjected to a discursive analysis [

27].

The analysis was inductive as themes emerged through the texts constructed in interaction with the participants rather than using a pre-established code tree based on theoretical preconceptions. The identification of themes focused on a semantic or explicit level [

27]. It should be noted that the topics presented in this paper focus on the transformations in their neighborhoods perceived by young people based on their talk of crime. These transformations can include their experience in the neighborhood space, changes in care practices and the meanings given to drug trafficking, and the emergence of social problems (including both material and symbolic transformations). The study assumes that these transformations are not the only possible ones but that they represent those experienced and perceived as relevant by young people.

Talk of crime is also seen to not only represent the direct experiences young people have had but also incorporate indirect experiences. Talk of crime is influenced by objective conditions of existence as well as broader social discourses about drug trafficking and insecurity, among others. Talk of crime reflects young people’s common-sense knowledge about drug trafficking in a local context. This knowledge is built in everyday life from concrete experiences with crime and insecurity, stories from others, conversations with members of their social networks, and the influence of the media and the entertainment industry, as well as other sources of social discourse about drug trafficking, such as the State. Although the degree to which participants have been incorporated into drug trafficking or the distance that exists with this type of activity (in terms of the participation of family members, friends, or acquaintances in it) is not known, it is considered that young people are witnesses of the social damage that can be caused by drug trafficking (although young people do not have a single position regarding this phenomenon, acceptance or naturalization coexists with ambivalence and rejection).

The thematic content analysis was carried out using MAXQDA 20 computer software. For this study, text segments were selected from the various group interviews in which young people spoke about the influence of drug trafficking in their community, either directly or indirectly. Using the program, notes were initially made about the texts, and codes and sub-codes were subsequently developed by carrying out a line-by-line analysis. A review of the coding was then carried out, and the codes and sub-codes that were relevant to the analysis were kept. The codes and sub-codes were then grouped into broader themes or categories that reflected the transformations in the neighborhoods, using the criterion of internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity between the themes and verifying the fit of the themes with the extracts [

27]. Using the software, frequency tables were obtained that showed the presence of the categories or themes across the interviewed groups. Finally, a thematic map was created that showed the central themes identified, and its fit with the data set was verified. The main categories and sub-categories identified are found in

Table 4.

3. Results

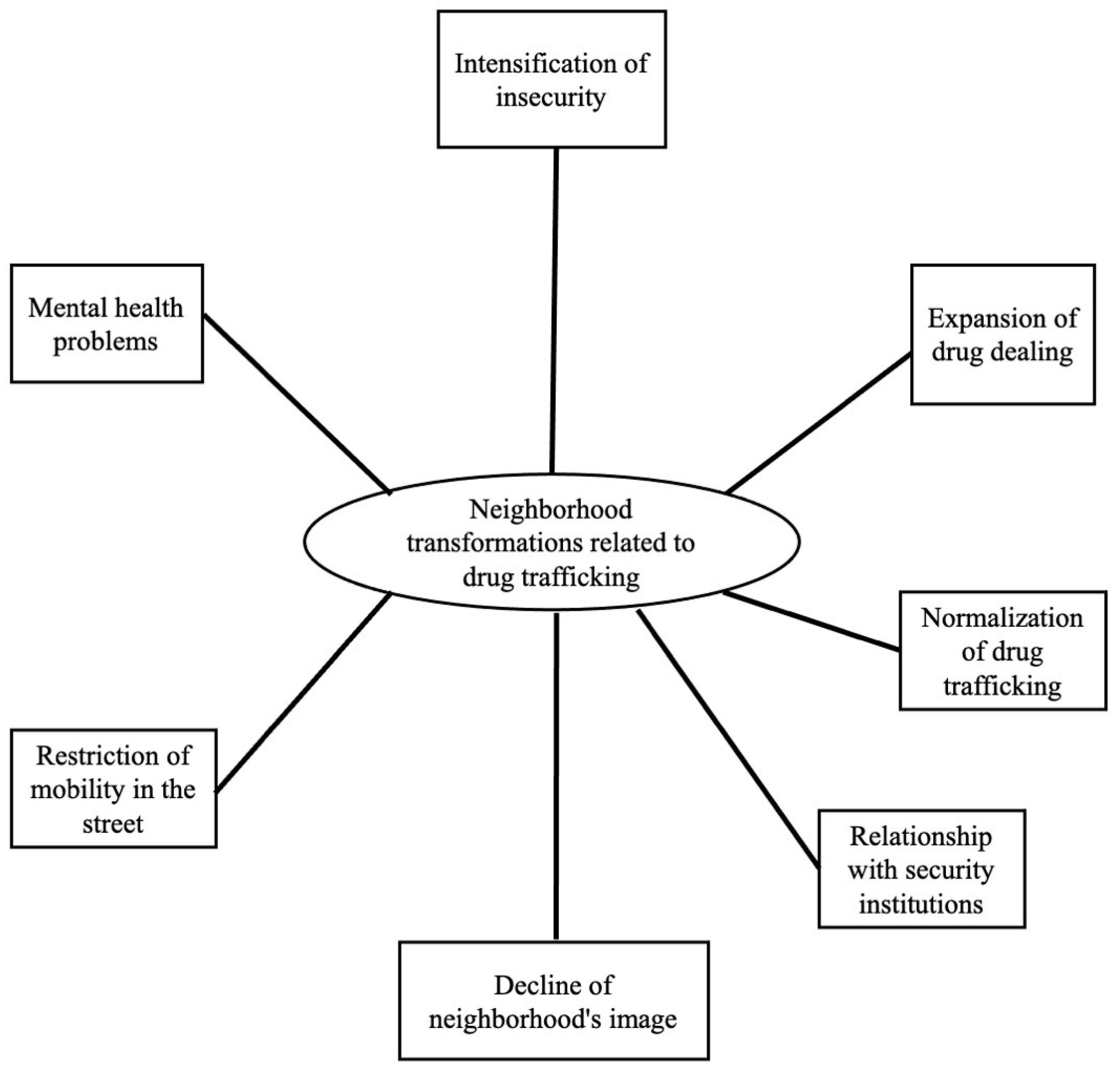

This section presents the categories that represent the main changes generated by drug trafficking in the neighborhoods from the perspective of young people (

Figure 1). The testimonies exemplify various categories and sub-categories found in the study. The main changes identified were as follows: the intensification of insecurity, the expansion of drug dealing, the emergence of mental health problems (especially related to addictions), the normalization of drug trafficking, the restriction of mobility on the street, changes in the relationship with security institutions, and the decline of the neighborhood’s image.

It is worth noting that these changes are interrelated; for example, the expansion of drug dealing leads to the emergence of mental health problems and contributes to the intensification of insecurity through common crimes associated with the need for consumption or incivilities against residents due to disinhibition or intoxication. In addition, young people mainly refer to drug trafficking that operates in the local market, not to drug trafficking as a transnational organized crime (although both manifestations have historically coexisted in the city due to its geographic location on the border with the United States and as a transit point on the drug trafficking route from other states in the country). It is worth mentioning that the names of the participants were changed to protect confidentiality, and each participant was assigned a pseudonym.

3.1. Intensification of Insecurity

From the perspective of young people, the main consequence of the presence of drug trafficking in their neighborhoods is insecurity. There are risk situations directly or indirectly associated with drug trafficking. Direct risk situations are high-impact crimes, such as shootouts, homicides, forced disappearances, and the dumping of bodies in public spaces such as empty lots or canals (although it should be noted that not all crimes can be attributed to criminal organizations; they can also be committed by private or state agents). From the perspective of community members, these events are the result of conflicts between rival groups, the settling of scores, and shifts in the balance of power in the sale of drugs in a particular area. For example, Alexa, a female high school student, tells that in her neighborhood, there have been homicides related to drug sales.

The block behind us, all of us know the house where they sell drugs, and on the next block they sell drugs, and then two blocks further down there have already been murders.

[Group interview No. 39]

Murders associated with organized crime are not evenly distributed around the city. The violence is intensified in areas where there is a conflict between rival groups for the control of routes or local markets, where there is a fragmentation of power in an organization, or where there is a rupture in the official collusion that allows the organizations to operate with impunity. Sofia, a female university student, describes how drug confiscation by the police affect drug dealing and at the same time generate an atmosphere of tension and conflict in the community.

Well, in my community there seem to be a lot of men involved in that, but since they have an agreement there in the community, and since no one interferes with anyone else, but for example, a little while ago a new man was put in charge of the police, and they stopped a van filled to the roof with pure cocaine, and that created a conflict in the community, they couldn’t sell drugs. At least in the community, it’s known where drugs are sold. And it created a bit of conflict because they seized a lot of money. At the same time, it was one or two months that things were like that, that they didn’t do anything, or people went to ask and they said no, there’s nothing to sell because all of that was going on.

[Group interview No. 48]

In some neighborhoods, drug trafficking organizations establish a system of surveillance to operate. Using motorcycles or hidden observers, they monitor the appearance of police or other security services (such as the army in areas with high levels of conflict between criminal organizations), although these measures also allow them to identify rival organizations or suspicious persons from outside the community. This surveillance is an indication of the degree of control they maintain. It does not create the same concern among residents as other measures, such as the use of roadblocks or searches of community members. Carmen, a female high school student, recounts how drug trafficking groups often employ an informal surveillance system to monitor police appearances, especially when there are no agreements in place to allow drug dealing.

It’s that they have their lookouts, who are watching when people go out, when they come in, who arrives …when the police car passes by and when it gets here … and the people in the tienditas and all that are warned when the police car is coming. And they already know the police. … Guess what? Policeman X is coming in that patrol car. And everyone disappears. … and that’s that. So they come back in a little while; they look around to make sure the dust has settled, and they come back… If not, no one comes back.

[Group interview No. 29]

3.2. Expansion of Drug Dealing

Another consequence in the neighborhood is the increase in the sale of illegal drugs. Although Mexicali is a border city where drugs are trafficked to the United States, young people make more reference to the neighborhood becoming a sales point that attracts residents from other neighborhoods, as well as consumers from within the neighborhood. It should be noted that drug dealing in the city is not linked only to criminal organizations that control selling in a particular neighborhood; there are also independent sellers, where the dealer is a middleman, so that the buyer does not have to go directly to the neighborhood.

Drug dealing tends to be concentrated in specific areas of the city. This concentration has repercussions on daily life in these neighborhoods; drugs are sold in public spaces, such as streets or parks, and in private spaces such as houses that become tienditas (lit., “little stores”), parties, or facade businesses. The proliferation of places where drugs are sold affects the social ecology of the neighborhood, with various interrelated results. For example, Alan, a male university student, identifies several ramifications of the tienditas: the initiation of consumption among young people, distrust in social relationships due to the perception of consumers as dangerous, or a greater risk of criminal behavior.

The sale of drugs leads to the fact that there’s a tiendita, so more drug users go to that tiendita, and the block or the neighborhood is going to fill up with people who, well, are maybe not trustworthy, or there could also be a settling of scores, something could happen. So the neighbors don’t feel safe living there anymore, even if it’s a neighborhood that would seem not to be dangerous. It also leads to that. Or maybe that the young people begin to use drugs, and because they don’t have any way to pay for their habit, they start stealing where they live.

[Group interview No. 23]

Along with the increase in spaces for the sale of drugs, people from the community partly or completely appropriate public spaces to use them. They invade spaces like vacant lots or vandalized, abandoned houses and turn them into shooting galleries (

picaderos). They also use drugs in parks or outside supermarkets, which contributes to these places being socially constructed as “dangerous”. Residents perceive that they could be victims of aggressive or inappropriate behavior by people whose drug use has become problematic. It should be noted that not all substance use is considered problematic. The degree of use can be described along a continuum. At one extreme is beneficial use, which has a positive impact on health, spirituality, or social issues. For example, beneficial use occurs when drugs are used as medicine, to increase alertness, or for relational and ceremonial purposes. Next comes non-problematic use, which is characterized by being recreational or casual, and does not have a significant impact on health or social relationships. This is followed by problematic use, which can be potentially harmful because it has negative health consequences for the individual, friends, families, or society. At the other extreme is problematic use, which culminates in a substance use disorder, according to psychiatric criteria [

28]. In this testimony, Julia, a female university student, comments that shooting galleries have expanded in the city. This has occurred mainly in neighborhoods with a higher degree of community disorganization.

I think it’s really obvious when there are picaderos in a neighborhood, because it’s a place where people are always coming out, and you can see the type of people going in and out, day and night. I think there’s a picadero in every neighborhood. Here at least in Mexicali I have seen one place, I have been here for seven years, and in every place I have lived, maybe not next door to me, but I have always seen the picadero.

[Group interview No. 46]

3.3. Mental Health Problems

As mentioned, drug trafficking in the community also creates insecurity indirectly by increasing drug consumption in public spaces and subsequently causing the emergence of incivilities and common crimes. For users whose drug use has become problematic, crime represents a strategy to continue use, especially when tolerance to the substance has developed or withdrawal symptoms are experienced. Residents mainly experience thefts from their homes, which means that they must remove valuable objects from their yards, keep their homes locked, and be constantly on guard against suspicious persons. Other common crimes are the theft of auto parts, such as batteries, and street robberies (sometimes armed). In the story of David, a male high school student, he expresses that some of his friends have resorted to theft to support their substance use.

Sometimes it even makes me sad, because the same people who go around robbing people are friends who left school and got involved in drugs and all that. You think, they could have done something better. And they’re from the community, I mean, it doesn’t make sense.

[Group interview No. 19]

Substance use can lead to mental health problems in users, especially substance use disorders. In the communities, this is expressed in the figure of a lumpen-user called “tecolín”, characterized by a deteriorated body and ragged clothing, who might be in street situation. The term “lumpen” is used to indicate belonging to the lowest social stratum. In the Marxist tradition, it refers to the part of the proletariat in conditions of extreme poverty such that it cannot acquire class consciousness. In this work, the term lumpen-user is used to refer to users in conditions of structural vulnerability or socioeconomically marginalized users. It is believed that tecolines resort to robbery or theft to survive and keep using drugs and that they depend on the charity of residents, on helping with household chores, and on income from collecting and recycling trash. Residents worry that they might turn hostile or aggressive during a psychotic episode or in a state of intoxication and harm someone. Some young people also use the term “drug addict” to refer to both consumers in street situation and consumers in better socioeconomic conditions. In this conversation, two high school boys consider that lumpen-users follow a trajectory of progressive deterioration, culminating in severe mental health problems.

Jonás: Where I live most of the female tecolinas are crazy (“están mal de la cabeza”), I don’t know. Most of the ones I’ve seen are like that.

Interviewer 2: But why are they like that?

Jonás: Most of the tecolinas are like that because they got into drugs. For example, I might be okay, but if I start using drugs, little by little I get worse, my family is going to leave me, throw me out on the street, since I’m trying to steal.

Luis: It’s a habit.

[Group interview No. 11]

3.4. Restriction of Mobility in the Street

The insecurity generated in the neighborhood, due to high-impact crimes associated with the dynamics of drug trafficking, the appropriation of public space for drug dealing, and the proliferation of consumption (associated with mental health problems, incivilities, or common crimes), contributes to the restriction of mobility on the streets.

Families are afraid that young people will be exposed to drug use in public spaces or that dealers will sell them drugs or recruit them to selling drugs. They are also worried about falling victim to robbery, aggression, injury, or sexual attack by people using substances or who are in a state of intoxication, as well as by those with other mental health problems associated with chronic use. These conditions limit mobility in public space and promote the adoption of strategies such as changing routes and schedules, the accompaniment of family and friends, constant vigilance, the avoidance of people perceived as dangerous, and the use of self-defense practices. In this excerpt, Diana, a female high school student, tells how her father was the victim of drug-related assaults on multiple occasions. As a result, her father had to develop different strategies to protect himself in his community.

My father, when he goes to work in the morning, leaves at 4 a.m., before the sun is up … One time he was leaving … and he told me he was going to take his bike. Now he takes the car, but when he took his bike he took a stick or something like that, because they robbed him like four times, and he always looked for the same people, and it was like … he already knew … he had a bat and … they were on drugs … and they stopped him like four times, so now it’s better to take the car.

[Group interview No. 37]

The selling of drugs is usually the most visible part of the criminal organizations linked to drug trafficking in the community, owing to the transformations brought about by their sale and use. The main roles identified by young people in drug trafficking are dealers and consumers. They express less visibility in their neighborhoods of other actors who play the roles of distributors, “jefes” (bosses) or “sicarios” (hitmen). Although the roles within drug trafficking most associated with violence are less visible in everyday life, the expansion of drug dealing and consumption in public spaces and its influence on the development of common crimes and mental health problems have a significant impact on spatial practices within the neighborhood and the generation of emotions of uneasiness and fear that affect the quality of life of young people, their families, and peers.

3.5. Normalization of Drug Trafficking

Drug trafficking manifests its power through the control it exercises over neighborhood territory and its capacity to use violence toward multiple ends. If the tecolín is the devalued product of narcocapitalism, at the other extreme is the narco, a figure that provokes ambivalence: a mixture of fear and admiration, an image of the search for social mobility through violence and illegal activity. The figure of the narco proliferates as the organizations of drug trafficking move around to colonize territories through the expansion of their activities and control routes and local markets. Simultaneously, the neighborhood can be a place of shelter from conflicts between rival organizations or police agencies. In addition, when the narco is part of community life, together with his family, the members of criminal organizations are shown not to have a relationship of exteriority with society but to be immersed in it; to a degree, they can hide themselves based on the way in which they display their social and economic power in public spaces. In this conversation, two female university students mention how the figure of the narco blends in with the rest of the community, although they can be identified by gestures that express their economic power.

Interviewer 1: Ok, so you say that they [the narcos] came to hide out, and that caused more violence.

Cinthia: To hide out in the small communities because they act like normal people, I mean, you really don’t identify them as …

Interviewer 1: Yes, it’s not like you look at them.

Cinthia: It doesn’t really show what they do, but you look, for example, you go someplace to eat, we’ve seen that they want to pay and instead of pulling out one bill they pull out a wad of cash, and it’s clear that …

Interviewer 1: Ah.

Daniela: It’s something natural.

Interviewer 1: It’s like a clue, or, well, you know that if someone pulls out …

Daniela: Why would someone carry so much money in their pocket, and they’re men…

Interviewer 1: And they’re men?

Daniela: Most of them are men.

[Group interview No. 44]

The figure of the narco has various forms. They can blend in with ordinary citizens, as a way of making themselves invisible, of incorporating themselves into the social body, of camouflaging themselves. But they also express themselves through an aesthetic of ostentation, big spending, and the flaunting of power with arms, money, clothing, cars, jewelry, women, and substance use. The ambivalence toward the figure of the narco is reflected in a cultural transformation of some parts of the population who pretend to be part of their world as an expression of aspirations that are not only aesthetic but also that pertain to social and economic power. For example, Gabriel, a male university student, makes a distinction between “real” narcos and “fake” narcos (or “pseudo-narcos”). The latter do not belong to organized crime but identify with the figure of the narco and pass themselves off as one; that is, they behave in everyday life according to stereotypical representations of narcos in the locality.

Here in Mexicali I have heard a lot about people who think they are, who have ideas about going around with narcos and all that, and that carry guns, and well, they don’t bother me so much as the people they hang out with who are narcos and do know how to use a gun.

[Group interview No. 22]

One difference between “real” narcos and pseudo-narcos is that the formers tend to use violence selectively (as in the case of homicides or “ajustes de cuentas”) and in a more hidden way to avoid being apprehended. In contrast, the pseudo-narco only tries to show power and threaten or have conflicts with inhabitants as a form of ostentation and affirmation of a social hierarchy, taking advantage of the symbolic construction of the narco in the city. In this conversation, two female university students rate pseudo-narcos negatively for two reasons: they generate unnecessary conflicts, and they do not have enough power.

Mariana: And I’m not defending the narcos or anything, but many times I have come to see that the narcos show more respect than the pseudo-narcos, the ones who think they’re narcos … They show more respect.

Arely: They do their work quietly; I think it doesn’t interest them.

Mariana: I have heard a lot that they come to kill someone and more people die where that person is.

Arely: That’s true, when they’re out for someone, they don’t see, they don’t think about who’s there …

Mariana: … okay, so that, okay, they themselves, since they’re quote-unquote taking care of each other and such, because I think that those who are narcos and do have power, it’s more cautious, and those who fight, who carry guns, “I’ve got a gun, look at me, for my balls” are those who think they’re something but don’t really do anything, and they’ve got a gun and they don’t let go of it.

[Group interview No. 47]

Another consequence of the activities of drug trafficking organizations is that they facilitate the entrance of young people into drug dealing. This incorporation is not only due to the fact that young people are exposed to drug trafficking or are recruited by its members but is also facilitated by the symbolic construction of drug trafficking in the community. There is no monolithic construction of drug trafficking, rather there are coexisting perspectives that range from acceptance to rejection. Although a large part of the participants considered drug trafficking to be an illegal activity, most young people perceived it as a job or a business. This situation reveals that drug trafficking in the neighborhoods also generates a cultural transformation: the acceptance and normalization of drug trafficking as a strategy for social mobility. Especially in poor communities, these organizations represent a path to economic mobility and social status. They also contribute to a sense of belonging and the construction of an identity. Families not only fear that young people will start using drugs at an early age and become addicted to substances but also that they will begin a life of crime. Diego, a male high school student, talks about his involvement in drug dealing in his neighborhood.

Just because I was there in the street, they offered me a certain amount of money if I would sell a drug package, and I accepted. Yes, it was dangerous. The first time you feel like they’re going to entrap you, but every time you do it, you’re a little less afraid.

[Group interview No. 6]

3.6. Relationship with Security Institutions

Another consequence of the presence of drug trafficking organizations is the change in the relationship with public security institutions, especially due to corruption. Young people express that the police are bought off; that is, they collect a regular payment to allow criminal organizations to carry out their activities, they guarantee a certain degree of impunity, or they provide a warning of police operations. The degree to which corruption has affected the local security agencies is unknown, given that it is a hidden practice, only partially visible to community residents. For example, Liliana, a female high school student, mentions that agreements with the police are necessary for the daily operation of the “tienditas”.

Or the police often even charge a “fee.” … Over there where I live is where … Everyone knows it but no one says anything. … It’s like everything. … And there’s a house that always full of people taking drugs. The police go by … their vans lit up… They arrive, they stop, they collect what they have to collect, and they leave.

[Group interview No. 33]

The violence of criminal organizations in some neighborhoods has brought an increase in police operations. Although these measures are intended to contain violence and restore peace, residents are concerned that the search for suspicious persons leads to violations of their human rights and that they could provoke confrontations. There is also skepticism about the possibility of a truce without changes in the social, economic, political, and cultural conditions that allow for control of their neighborhoods by criminal organizations. There is uncertainty about what will happen after the police intervention because when the state disappears, the criminal organizations reappear—with the partial complicity of sectors of the state. In this conversation, two female high school students discuss how security forces can limit the rights of community members during raids.

Katia: And there were soldiers there … but because there was a “connection” in back, where they sold every kind of drug … and they always go there.

Edith: In fact, recently I have been seeing a lot of police here, in all the neighborhoods around here, I have been seeing a lot of police. Now they stop anyone and search them from head to toe so they aren’t going to be carrying anything.

[Group interview No. 27]

3.7. Decline of Neighborhood’s Image

There is not only a material transformation of the neighborhood but also a symbolic one. The image of the neighborhood is transformed: the presence of abandoned houses used as picaderos, tienditas for the sale of drugs, the tolerance of drug use in public spaces, and the increase in criminal activity and its connection to addictions are all symptoms of community decline. Neighborhoods are seen as “dangerous” or “unsafe,” which contributes to residents of other areas avoiding the streets because of the perceived risks. This situation has other repercussions, such as making it difficult for businesses to locate in areas with high crime rates and limitations on buying or renting property, especially given the absence of a state that actively collaborates in the renovation of the social fabric and the recovery of such spaces. In this conversation, two male university students talk about neighborhoods that have deteriorated in the city due to the multiple consequences of drug trafficking. This has led to the stigmatization and abandonment of these spaces.

Andrés: Well, I feel it’s because that’s where marginalized people or families go, like they are leaving … they are clearing out and leaving the worst. Maybe it’s discriminatory, but it’s the reality, the worse are left out. Like Santorales, Progreso … all of those.

Enrique: For example, Ángeles de Puebla is on the outskirts, and if you go through there you see more abandoned houses than houses with people living in them, with graffiti everywhere, and you look around … I drive an Uber and go through there around midnight, and you turn around and look, and it’s nothing but people doing drugs, people who are drunk.

[Group interview No. 24]

4. Discussion

Daily life in the neighborhoods shows a variety of consequences of narcocapitalism: capitalism based on illegal drugs. Its predatory logic targets the victims of drugs, and it takes advantage of the availability of precarious, unemployed, or underemployed workers who are driven by need into the world of drug trafficking as a disposable labor force used to pursue profit. The operation of narcocapitalism requires a process of mystification, the construction of a reality where what exists is hidden by what is said to exist. A discourse is constructed where the wars on drugs fight for peace, order, and development, while their reality is to tear apart communities and promote capitalist profit through drug businesses or money-laundering investment in legitimate businesses [

29].

The activity of organizations associated with drug trafficking in the communities amplifies the density of places providing access to illegal substances, and the presence of criminal hotspots is associated with the increase in risk behaviors in adolescents, be these aggressive, criminal, or caused by substance use, especially in areas with high levels of marginalization and violence [

30]. It is not only a matter of exposure: the beginning of drug use is also linked to the normalization of recreational drug use in social media, peer pressure, distress, and mechanisms for coping with trauma [

31]. It is also associated with family relationships where there is insufficient support and supervision or where parents themselves use legal and illegal substances [

30].

The

lumpen-user, or

tecolín, is a social type that provides young people with a warning or moral tale about the risks of substance use. Its relationship with the operations of street dealing is usually obscured. The figure of the

tecolín is constructed as anomic, excluded, and stigmatized. It allows community members to define the limits of the community and express their superiority in terms of status [

32]. It represents an essentialized category that naturalizes and legitimizes inequities; as a symbol of evil and the causes of crime, it is a means through which feelings related to neighborhood transformation are expressed. The

tecolín is perceived as an invading figure that degrades the environment and is treated as contaminated [

15].

Although young people are aware of the risks associated with drug trafficking, it has become an alternative for social mobility. Exposure to and incorporation into illicit labor markets during childhood favors the formation of criminal capital that legitimates criminal, illegal, and violent lifestyles and limits the ability to stay in school and benefit from education. This in turn reduces opportunities for access to better wages in the formal sector. In adulthood, it increases the probability of remaining in illicit drug trafficking, being imprisoned for violent or drug crime, and harboring distrust toward state institutions such as the police and justice system [

33].

Although drug trafficking organizations do provide a mechanism of social mobility [

34], young people’s entrance into such activity is not solely motivated by a lack of resources for basic needs. It also responds to a relative privation: their local context emphasizes the consumption of objects of pleasure to which they have limited access. They are motivated to enter drug trafficking by a desire for money and consumer goods, for economic independence, and for self-affirmation. The adoption of a hedonist lifestyle exists side by side with the excitement of the power to offend, the feeling of having nothing to lose, a lack of meaning linked to critical life events such as abandonment, violence, abuse, and traumatic experiences, or as compensation for having suffered multiple losses [

31].

For young people, the main source of knowledge about organized crime is people in their immediate circle, such as friends and acquaintances. Without social institutions such as the family, educational institutions, or media providing objective information sufficiently shaping their perspective and civic position, they can acquire distorted views of organized crime that encourage its romanticization, ambiguous moral values, or the use of fear and threats as means of control. If they live in an environment where people have criminal pasts, it is difficult to acquire social roles and assimilate moral and ethical values that legitimize respect for the law [

35]. Drug trafficking organizations require symbolic violence to impose the legitimacy of multiple meanings inscribed in the social dynamic [

7]. To construct their legitimacy, it is necessary to have a process of identification with figures linked to illegal activity, such as the

narco.

The adoption by young people of a position resistant to the ideological domination of organized crime can be limited when the community is immersed in a symbiotic relationship with drug trafficking. In this relationship, the community provides work and offers protection and services, while drug trafficking offers “jobs,” economic activity, infrastructure, and informal networks of “protection” that provide security and resolve disputes. The minimal cooperation of the community consists of not actively opposing its operations and not collaborating with the authorities: a minimal degree of tolerance or indifference. This cooperation is not necessarily the reflection of a collective moral defect or the glorification of criminal activity but of an everyday reality lacking in opportunities for social mobility and where relationships with the state are negative. The reduction in levels of drug-related violence in communities may be related to community support for its activities, since enforced solidarity becomes a form of protection for their residents [

36].

In addition to symbolic violence, drug trafficking organizations need to develop other control mechanisms. There are regimes of narco-governance in communities in opposition to or in collusion with the legal authorities that are a basis for survival, income, and avoiding arrest. They are partially separate from the state, constantly articulating their own unwritten rules and power structures to govern the drug traffic. They resort to violence as a mechanism of regulation, and they derive power from other direct relationships, such as threats, personal connections, and their ability to evade or negate the written law. Criminal organizations imitate the state and simultaneously insert themselves into it; they are mirror images of the state that they are at war with. If criminal organizations become stronger, they could simulate an oppressive or controlling state [

37].

The experience of insecurity in communities grows as drug trafficking organizations acquire greater criminal autonomy, plunder local economies, exercise continuous violence, and affect social relationships and the moral order [

34]. Faced with the inability of their institutions to provide sufficient protection, and an intensification of fear that makes collective action impossible, community members turn to withdrawal into the individual and private spheres, the establishment of limits, daily life focused on personal security, and the political production of “zero-risk zones” [

7].

This work coincides with the findings of several previous studies. In a study conducted in the United States in a community where violent crimes occurred, consequences such as decreased feelings of security and a poor reputation of the neighborhood were identified [

38]. Another study in Central Mexico also showed that the commercial expansion of drug trafficking in the neighborhoods is manifested in the creation of fixed sales points (“tienditas”) and semi-fixed ones (such as parks or parties). The more visible these points of sale are, the greater the complicity required from authorities and community members [

39].

A comparative study conducted in Sinaloa and Michoacán also found that drug trafficking is associated with various expressions of social harm such as insecurity, violence, and the development of addictions. However, the degree to which drug trafficking is normalized depends on conditions such as its historical presence in the city, the way it is inserted into the life of communities, and the use of violent methods in public spaces [

40].

Studies in Baja California (located in the northwest region of Mexico), the same state where this work was carried out, also reported that, among young people, there is a predominance of a normalization of drug trafficking as a business, a “work” option, or a paradoxical “illegal job”. This position coexists with a demonization of drug trafficking due to its association with violence and addictions [

41,

42,

43]. A study carried out in the northeastern region of Mexico, in the state of Tamaulipas, also reported that the presence of organizations linked to drug trafficking increased the levels of insecurity and violence in the city, as well as restricted mobility and an increase in parental care [

44]. Although, in the present work, it was found that one impact of drug trafficking has been the increase in substance consumption and the development of mental health problems, another study reported a decrease in consumption and access to drugs due to the control of organized crime in the community, the limitation of the internal market in the city, and the fear of young people to become victims of violence or being recruited [

45].

Policy to combat drug trafficking organizations and promote peace and development cannot be separated from the social, political, and cultural context in which such organizations operate. This policy may affect border economies and local communities by interfering in networks of exchange and investment capital associated with the drug trade, the interests of elites, and political arrangements among the parties involved. Existing conflicts might be exacerbated or new ones created that lead to a greater exposure to violence in public space. It has thus been suggested that public policy be implemented gradually, prioritizing the reduction in harms and violence created by drug use over the forced eradication of drug trafficking [

46].

In urban contexts, in addition to reducing the perception of neighborhood crime, it has also been proposed to increase levels of informal social control by connecting young people with mentors and providing them with educational and recreational activities, appropriately structured for their level of development [

8]. Policy must be directed at the prevention of addiction and criminal behavior, the recovery of public space, and the construction of mechanisms for the psychosocial protection of young people. The strengthening of systems of security and justice is also essential in order to reduce the extent of drug traffickers’ control over communities and rising violence in public space.

Among the limitations of the study, it is important to mention that it is necessary to incorporate the perspective of young people not in school and young people of a high socioeconomic level since young people are a heterogeneous group and multiple positions coexist with respect to drug trafficking in the local context. It is also necessary to recover the voices of other actors with whom young people interact in their communities, such as families, school staff, health personnel, the police, or religious institutions. Finally, it should be noted that the impact of drug trafficking is not similar across neighborhoods either; ethnographic approaches are required to delve deeper into the singular way in which drug trafficking is inserted into specific communities and the transformations that occur over time.