Abstract

The perception of the concept of Eros has evolved through shared cinematic experiences, to the point of shaping collective imagery in Cadiz, Spain. This city is known for its creativity and an extraordinary amount of performances during the period of carnival, and is represented annually by anonymous citizens. The research method employed consisted of an exhaustive analysis of bibliographic, press, and archival references on audience behavior from the introduction of the cinematograph to the present day. The authors have designed a table that organizes the emergence of movie theaters in the city and completed the background information, delving into the historical, geographical, and idiosyncratic factors that have contributed to collective creativity in the city. From there, we analyzed the evolution of the concept of Eros through the perspectives of Byung Chul Han and Georges Bataille. As a result, we recovered the value of projection interruptions in the analog environment as an opportunity for collective interaction, confronting them with the demands of technological perfection. We demonstrated the resilience of the analog through new experiences that show the evolution of the need for collective contact. Future studies will focus on other contexts, such as supermarkets and terraces, to contribute to a broader understanding of urban spaces, social cohesion, and perceptions of Eros.

1. Introduction

The progressive digitization of everyday life entails a series of changes in how humans interact and connect. These changes are occurring across all domains: work, education, social relationships, and beyond. Therefore, it is essential for the academic world to stay alert to the transformations that happen in this regard and how these transformations reshape the very structure of society. In this case, we wanted to focus on one of the experiences that has changed the most in recent decades with the initial digitalization of sound reproduction systems in the 1990s and the subsequent digitalization of image projection in the first decade of the 21st century: cinematic projection. To do this, we chose to concentrate on how this experience has changed in a city that, due to its geographical and social characteristics, might seem more resilient to adopting the forms that digitalization imposes on nearly all venues dedicated to cinematic projection: the city of Cádiz, the southernmost provincial capital on mainland Spain. This town enjoys a forgiving climate, allowing for numerous outdoor screenings, and is also home to one of the most significant carnivals in the world, which fosters imagination and public participation. Carnival is a popular festival of pagan origin that precedes Lent, a period of 40 days of abstinence and reflection in the Christian tradition that ends with Holy Week. These festivities are present in many countries, with important cultural and local variations. People usually participate in masquerades, musical groups, and dances, creating an atmosphere of joy, permissiveness, debauchery, and even subversion.

For this purpose, we analyzed how the people of Cádiz interact with cinema today, but we consider the evolution of the economic and sociocultural conditions that influence how citizens understand the experience of attending a cinematic projection. This has been studied, for example, in the case of Indian audiences watching English-language films in the 1930s, French audiences viewing American cinema in the 1940s, and Portuguese audiences experiencing Mexican films in the 1950s [1], so we took these variations over time into account when designing our study.

Our research focuses on the unique characteristics of the population of Cádiz and aims to analyze the changes in aesthetic experiences resulting from the improvement and expansion of cinema theater technology. This study fits within the tradition of works that examine the transformation of pseudo-analog experiences in a digital world and compares them to other consumerist experiences of the present day. Additionally, our research overcomes the limitations of a purely historical perspective by adopting a broader view of the evolution of cinema theater spaces. In our approach, we emphasize the significance of the geography of the Cádiz peninsula and its impact on the social characteristics of its population and historical context. However, the conclusions we draw are equally applicable to any cinema hall that undergoes a process of digitalization and adaptation to new technological conditions.

Throughout our investigation, we conduct a review of previous studies on cinema in Cádiz, which primarily focus on audience behavior within cinema halls. During our discussion, we ponder the emerging sense of being, pornography, and eroticism in their philosophical dimensions. To explore these topics, we refer mainly to the works of Georges Bataille (1957) [2], Byung-Chul Han (2013, 2014) [3,4], and Walter Benjamin (1936) [5]. We discuss the perception of Eros and its role in transforming life through movie theaters in various ways. First, we clarify the definition of the concept of eroticism and how it disrupts the notion of a perfectionist projection to become a living trajectory. Secondly, we analyze the impact of technical advancements in cinema in Cádiz and the limitations on freedom during Francoism. Third, we apply the notions of the “agony of Eros” (Han) [4] and the “aura” (Benjamin) [5] to the city, noting how some theaters continue to use analog devices despite resistance. By examining the distinctive qualities of Cádiz, a city that, since Romanticism, has been said to offer a captivating setting for a philosophical exploration of eroticism, we gain insights into the negative impact of technology on our experience of Eros, as contended by Han (2014) [4].

This discussion led us to valuable conclusions for other analyses of urban spaces in relation to the perception of Eros, which we plan to conduct in future articles, such as those focused on supermarkets and outdoor terraces of bars and restaurants.

2. Materials and Methods

This research is based on three primary elements. Firstly, a historical investigation was conducted into the evolution of audience behavior in cinema theaters and other sorts of entertainment, with a focus on the Spanish city of Cádiz due to its unique sociopolitical conditions. Secondly, a meticulous examination was carried out on the works of Georges Bataille and Byung Chul Han regarding the concept of Eros. Lastly, an analysis was conducted, applying Byung Chul Han’s concept of the agony of Eros to the cinematic spectacle to determine to what extent this concept influences audience behavior when deciding whether or not to attend theaters.

As mentioned, this study commenced with an in-depth analysis to understand the influence of local audience behavior in cinema theaters, with a particular focus on the city of Cádiz. To ensure a comprehensive understanding, an exhaustive list of cinemas within the city was compiled. This list included details such as their geographical locations, operational specifics, and the evolution of equipment used within these spaces.

While the equipment used was not exclusive to the city, it was observed that their utilization was significantly influenced by the unique characteristics of the local population. This observation was made during our extensive fieldwork within the city, where we discovered a movie theater named La Bombilla. This cinema offered a unique pseudo-analogical experience, which was explored in detail to understand its impact on the audience.

A comprehensive literature review was conducted by visiting various libraries in Cádiz. This was primarily due to the fact that many relevant monographs, often authored by local scholars, had not yet been digitized. We delved into public behavior articles documented in local newspapers, with particular attention given to La Voz de Cádiz and Diario de Cádiz, one of the oldest newspapers in Spanish journalistic history.

In addition to this, we also visited former cinema sites, paying special attention to the outdoor ones. The city’s variable wind patterns were taken into consideration, as they affected the screenings and could potentially provoke interactions among the audience. These unique characteristics were then debated in the context of aesthetic notions related to Eros and aura.

This study also delved into the historical background, taking into account a variety of historical events and movements that shaped the city and its cinemas. These included the decline in overseas trade, the rise of liberal thought, and the influence of anarcho-syndicalist labor movements, like that attributed to Fermín Salvochea. The history of cinemas in Cádiz was reviewed through articles from newspaper, municipal, and provincial records.

On another note, this study analyzed Georges Bataille’s concept of Eros in contemporary society. This concept explores the role of erotic desire and its manifestations in today’s social and cultural dynamics. Furthermore, this study examined Byung-Chul Han’s theory regarding the ‘agony of Eros’ in the present age.

Han’s theory explores how advancements in technology and the rise of individualism have transformed the erotic experience into a type of self-centered isolation. Such a shift in the perception and experience of Eros was critically analyzed in the context of the alterations in the cinematic spaces of Cádiz. The cinemas, once bustling group-gathering areas, have progressively transformed into personal seclusion spaces, reflecting this societal transformation.

The results of these debates are presented in this article, focusing on the specific objectives of our study. To ensure clarity and coherence, discussions involving other spaces beyond cinemas have been omitted, for the time being. This study provides a comprehensive understanding of how local audiences’ behavior in theaters has evolved over time, influenced by various social, cultural, and technological factors.

The history of cinemas in Cádiz was reviewed through articles from newspaper, municipal, and provincial records. The transformation of cinemas from 1898 to the post-war era was studied in detail, covering various historical periods, such as the Second Spanish Republic, the Spanish Civil War, and the post-war Francoist dictatorship. Each of these periods had a significant impact on the evolution of cinemas and audience behavior within them.

Furthermore, the alterations in the cinematic spaces of Cádiz have reflected the societal shift from group gathering areas to personal seclusion spaces that is explained by Byung-Chul Han’s theory.

In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive understanding of local audience behavior in theaters, the transformation of cinemas over time, and the influence of societal and technological changes on erotic experience in contemporary society.

3. The City of Cadiz, the Citizenship of Cadiz, and the Cinema Spectators

3.1. Exploring the Social Characteristics of the Population of Cádiz through Collective Performative Experiences

Festivals offer a unique window into the defining traits of a community. One such celebration, the carnival of Cádiz, was granted the coveted designation of a Treasure of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Spain by the International Bureau of Cultural Capitals in 2009 [6]. The 609/2019 legislation has also officially registered the carnival of Cádiz, a Cultural Property of Interest, as an Ethnological Interest Activity in the General Catalog of Andalusian Historical Heritage. As we said above, the carnival of Cádiz is renowned for its vast array of musical pieces, created annually by known and anonymous composers. A multitude of groups participate in a diverse range of characters across the city, with some groups being more “institutionalized” and taking part in the Official Carnival Groups Contest. Located on a southwestern isthmus in the southernmost province of Andalusia, the city of Cádiz undergoes a significant metamorphosis during its extensive carnival revelries. Various groups of citizens, both formalized as carnival entities and groups or informal, come together for communal gatherings, competitions, parades, and processions marked by costumes, parodies, original verses, distinctive rhythms, playing, and lively carnival performances. Thousands of individuals, in public and private establishments, as well as on various streets and squares, take part in this annual spectacle.

After months of extensive preparations, it can be asserted that a large portion of the local society and a significant number of visitors participate in a symbolic “appropriation” of urban space through a profoundly experiential and identity-rich festive ritual rooted in profound historical connections and characterized by active citizen participation [6] (pp. 154–155).

Historical records dating back to the 16th century document this festival, which, like other carnivals, challenges the institutional power structure [7]. Additionally, over time, it has been influenced by other celebrations, due to the city’s bustling trade with the Mediterranean and the Atlantic.

The experience of carnivals is deeply ingrained in the city’s collective memory and often influences daily communication and behavior, either directly or indirectly [8]. Popular beliefs, rooted in local socio-political history, are reinforced through oral tradition and memory, despite their contradictions. Social reality is reconstructed through each individual’s unique relationship with shared consciousness and memories expressed in a festive context, deviating from the ordinary. The behavior of the audience in cinemas in Cádiz is not what you might consider “normal”. Instead of silence and respect for the movie being shown, there is a continuous interaction with the film. This interaction includes engaging with the on-screen image as well as with other members of the audience. These behaviors contain festive elements that are characteristic of the carnival celebration.

3.2. The City’s History Encourages People to Interact with Those Who Are Different

The city of Cadiz, founded by the Phoenicians in 1100 BC, is often referred to as having 3000 years of history. Its historical background has contributed to the creation of imagery that extends from its oldest coastal ruins through literature [9] and the creation of carnival songs [10]. The city’s location as a peninsula and rich maritime, naval, commercial, and port traditions have significantly influenced its historical development as an open city. This, in turn, has contrasted with the rural practices prevalent in much of the province. The city’s unique geography and economic history have fostered a culture of openness, diversity, and innovation, making it a dynamic hub of commerce, culture, and creativity. As we said above, it experienced the impact of the decline in overseas trade, the influence of early liberal thought and cantonalism in the 19th century, and anarcho-syndicalist labor movements in the early 20th century. In recent decades, there has been widespread opposition to deindustrialization and recurrent economic and social crises.

The French and Italian influences date back to the intense overseas trade, which influenced both popular spectacles and those institutionalized by the bourgeoisie and aristocrats. Genoese merchants have been present in Cadiz since the 15th century, and by the 18th century, the city had become an important center of trade with the American colonies. This history of the town and its carnivals’ artistic manifestations, sentiments, and factors all reinforce each other and contribute to the recreation of a complex detachment and disbelief towards “political correctness”, while also exalting a localist and relativistic view of Cadiz and its identity. It is a form of face-to-face self-affirmation that can be seen as a cultural response to global homogenization [11].

The life connected to the sea and the intense and continuous encounters in the streets over the centuries in a city with a mild climate create an urban dynamic of encountering the other, which contributes to transforming urban space into public space, an intensely lived space by its citizens [11]. In its most comprehensive and complex sense, the street can be interpreted as a cultural space inherent to the festival, not only during celebrations but also in their symbolic extensions throughout the rest of the year. Certain areas within the city’s historical district hold significant value, such as the La Viña and El Pópulo neighborhoods and the Falla Theater. In various corners of streets and squares, informal carnival groups, also called street or Illegal Chirigotas (Figure 1), perform their repertoires in front of a live audience. Categorizing these groups can be challenging, due to their flexible and creative approach, which leads to unique and innovative outcomes. This makes it helpful to explore Eros’s development in cinema and its challenges.

Figure 1.

Carnival groups. (a) “Las Motomami, de venta en venta” (Motomami, from bike bar to bike bar), and a street “Chirigota” of women. Photograph taken on Armengual Street, Cádiz, on 11 February 2024. Source: Inmaculada Rodríguez-Cunill (b); multimedia videos with carnival groups (above) and a zenithal view of the city of Cadiz (below). Display in La Casa del Carnaval (Interpretation Center of the carnival of Cádiz), and photograph taken on 13 February 2024. Source: Inmaculada Rodríguez Cunill.

During the post-war era and the early stages of democratic transition, two opposing patterns emerged during the carnival of Cadiz. Firstly, the working class demonstrated a strong desire for freedom of expression and actively participated in the festivities to express themselves. Secondly, the local social elites and political authorities sought to control the carnival and viewed it as challenging to establish order and moral values [12]. This tension between popular participation and institutionalization has been a defining aspect of the festival’s history. These two dynamics have become more pronounced as globalization has taken hold.

3.3. Previous Studies on Cinemas in Cádiz

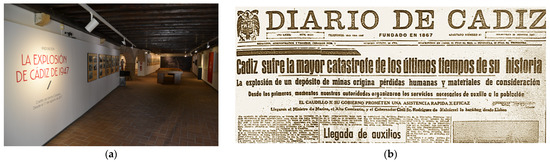

Extensive research on the history of cinemas in Cádiz, Spain, has been conducted by local scholars. Their work is based on various newspaper archives and municipal and provincial records, and is categorized according to the city’s history, that of Spain and the world [13,14]. Some studies focus on the period between 1898 and 1930, which includes the end of the Spanish Civil War [15]. Other research [16] explores pre-cinematic shows that laid the foundation for cinematic advancements, particularly in science fiction [17]. Specific years, such as the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939) [18] (Amar 1997), the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) [19], the Francoist dictatorship in the post-war era, with a geographical focus on the entire Andalusian region [20], and the city’s recovery after the disaster called “explosion of Cádiz” [1] (Figure 2a,b), have garnered significant historical interest. This last event had a profound impact on the town and the cinematic experience of its residents. Existing research has primarily focused on cinematic, historical, and architectural aspects, rather than on the impact of audience behavior in cinemas. We have gathered information from newspaper reports and believe that there is a fascinating opportunity to explore the evolution of public entertainment in a city shaped by its rich cultural and historical heritage. Our research offers insight into the connection between the unique characteristics of the people and the influence of technological advancements on social structures, stemming from a new technological paradigm. In the following sections, we will examine the socio-cultural dynamics that have reflected social changes since the early days of cinematographic projections, as well as the local implications of technological and architectural progress. Personal stories and ethnographic details will highlight the emotional and sensory experiences associated with going to the movies. Additionally, archaeological findings will shed light on the deep historical layers intertwined with the city’s cinematic heritage. It is worth noting that there is no local literature that covers the approach presented in this paper.

Figure 2.

The Cádiz explosion of 1947 (a), La explosión de Cádiz de 1947 (The Cádiz explosion of 1947). Exhibition view. Showcases of photographs and other documents about the historic disaster at Saint Catherine Castle on 17 August 2017. Photo by Emilio J. Rodríguez Posada, captured on 28 September 2017. Available through https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/9b/Exposici%C3%B3n_%22La_Explosi%C3%B3n_de_C%C3%A1diz_de_1947%22_%2837359048182%29.jpg (accessed on 25 September 2023); (b) the front page of the Cadiz newspaper on 19 August 1947, which featured the news of the catastrophe due to the explosion. Source: the authors.

3.4. Performativity of the Audience in the Cinema Halls in Cádiz

The manner in which the audience engages in cinema halls in Cádiz has developed over time, in sync with the city’s rich history. Refer to Table 1 for a comprehensive list of cinemas in the area. Certain cinemas have undergone transformations and name alterations; complete details for others remain unknown.

Table 1.

Table compiled from the consulted sources, particularly the various works of Garófano [1,13,15,16,21] and Amar [14,18,19]. Some peculiarities that could affect the experience of interactions in cinema halls are marked with an asterisk. Cineclubs are not included in this list due to their variable location.

Since the first projections of the cinematograph in the city, news of audience interactions began to emerge. Initially, these short films were exhibited in movie theaters or ad hoc barracks. During the aforementioned period, journalism focused on scrutinizing the quality of projectors, the luminosity of lighting equipment, and the vibrancy of images. It was a time when these technical aspects were considered the foremost parameters of success in the industry [21]. Another unifying element was that the audience could see themselves represented, such as when the first cinematographic images obtained from Cádiz were projected on June 6, 1898 (featuring the Corpus procession), or the view of the Cadiz Pier upon the arrival of the mixed train from Madrid on 1 February 1900 [13] (pp. 32–33). However, institutions soon saw the need to create a cinema, especially for summer nights. In 1908, the City Council used the Plaza de la Constitucion (now San Antonio Square) to set up the first open-air public cinema.

“The projector booth was located near Calle Ancha, and the delimited area was the closest to the San Antonio church. The screen was placed in the middle of the perimeter, so the chairs were distributed in front of and behind the screen (400 on each side). This had the advantage of reducing the distance between the low-power projector lamp and the transparent screen, whose images were seen in reverse by the spectators behind (from right to left). This became a minor inconvenience when text appeared in the films, but it was insignificant given the number of viewers who could read.”[21] (p. 74)

Some responses from newspaper articles provided clues about how these images affected the audience. One testimony is particularly relevant. On 22 November 1916, the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky was in the audience at the Teatro Principal and commented, “I was surprised by the Spanish audience’s passion in the cinema… the heroine approaches the box, and the audience erupts in cheers… the enemy of the family falls, and the whole room explodes in exclamations of jubilation. What will happen during bullfights?”1 [13] (p. 75). In January 1917, the Bishop of Cádiz stated that these films displayed immoral spectacles that aroused passions. He said he was obliged to warn the faithful that it was not permissible to attend cinemas and theaters [13] (p. 75). On 19 August 1917, local doctor Gómez Plana noted the great impression made by a film called Los Vampiros and confessed to attending to four patients (three children) because of it [13] (p. 77). This was the era of “virgin spectators”.

Garófano (2020) described human interactions in cinema theaters: the “smells of humanity”, loud comments (many directed at the projectionist), children’s screams, street vendors’ shouts, and, sometimes, a military band [21]. Newspapers spoke of a “social hodgepodge”; occasionally, the screening was interrupted because a deceased person was leaving the nearby San Antonio church. The urban center experienced a significant reduction in population due to the allure of a particular cinema during the night and subsequent establishments of a similar nature. The arrival of sound cinema (the first screening took place on 23 May 1931, at the Gran Teatro Falla) [1] did not inhibit the city’s interactions, noises, and other ethnographic aspects. When Teatro Falla screened La Bodega in 1929, the audience was disappointed because they could not hear the songs of Conchita Piquer, whose lips moved to the silent tunes. During the production of the film Perucha in 1924, a flamenco singer known as “La Niña del Patrocinio” sang a saeta (lament) during a projected procession. Meanwhile, the French actor Musidora danced, dressed in her film attire, and sang along with the images [13] (p. 83). In 1926, while the silent movie Los Enemigos de la Mujer (Enemies of Women) (1923) was being played, an announcement was made to the public that there would be technicians behind the screen creating the sound effects of shots. This was done to prevent the audience from getting frightened by the sudden and unexpected noises [13] (p. 87). However, the first talking picture, “Río-Rita” (1929), with Spanish subtitles, disappointed the spectators because it was spoken in English, which was not their native language. The media captured the audience’s reactions, but it was not until May 1931 that viewers were delighted. With the release of the American films El Precio de un Beso (A Mad Kiss) (1931) and A Media Noche (Midnight) they could finally understand and enjoy the Spanish dialogue and songs [13].

During the Republican period, when the documentary Fiesta de Carnaval en Cádiz (Carnival Festival in Cádiz) was screened, the reinforcement of identity signs forged a love for cinema that aligned with the city’s imagination. During this time (August 1933), the first air conditioning system was inaugurated at Cine Gades [22], which helped it resist the competition of open-air public cinemas. The necessary space of a comfortable temperature for many people in the summer led the Municipal Cinema to install a ventilation system in August 1933, too. Promoting interactions with the city, Cine Gades, which screened La Modistilla de Luneville (The Little Seamstress from Luneville) (1931), invited the city’s seamstresses to the film session [13] (p. 100).

In November 1933, Teresa Daniel sang and danced after the screening of the film La Chica de Montparnasse (La Petite de Montparnasse). In March 1935, after the screening of the film La Dolorosa (1934), one of the performers ended the show by singing on stage2. “Cine Oliva” was inaugurated in March 1944, which combined a movie screening with a boxing event [13] (p. 115). Another constant throughout the 20th century was the presence of spectators who did not pay for entry outside the perimeter of the screening spaces.

That festivity continued in the 1980s in Cádiz, as Domínguez (2016) reminds us: “I want to begin with a memory. It is the Cinema Caleta, an open-air cinema in an enclosed area in a popular neighborhood of Cádiz, the capital of the southernmost province of Spain. The chairs are made of iron and are welded in rows. Their appearance is not flashy: the paint covering the metal has numerous chips, and rust is visible everywhere. On the other hand, the auditorium’s walls are whitewashed and have a few damp spots due to the beach’s proximity, although they were painted at the beginning of the season, like every summer. People enter carrying various snacks, with sunflower seeds being the dominant choice. Inside, at the back of the theater, under a large balcony on the first floor, which is also open-air, is a bar where patrons drink beer or Fanta. People talk to each other. The air carries the aromas of the beach. I sit on the ground floor. I have never dared to go to that huge balcony above the bar. Everyone knows that you do not go there to watch the movie but rather to cause trouble. The film starts as a spaghetti western starring Bud Spencer and Terence Hill from the They Call Me Trinity series. The celluloid has numerous scratches, and occasionally, there is a break in the image, which, due to the way the image and sound are synchronized in celluloid projection, a few frames later is also a sound break. Sometimes, entire sequences are even cut. Every time there is one of those cuts, they shout from upstairs. In addition, there are interventions commenting on or responding to the characters’ dialogue or the actions seen on the screen. When the film ends, we stay inside for a while, talking about the movie or laughing at the comments, some of which we heard from upstairs. We leave the cinema, but it remains a part of our lives. When they close it down some years later and build a student residence, I will always feel that they have usurped the space of my affective memory, a space of erotic enjoyment, and replaced it with a functional space” [23] (p. 484).

References to movies within local newspapers disappeared during the summer, as they generally repeated programmed titles, and there were no new releases. This caused the few comments about the theaters to focus on atmospheric, phenomenological, and philosophically erotic elements that captured the viewers’ attention. For example, the Caleta cinema was inaugurated, highlighting its environmental quality in advertising: “The only summer venue sheltered from the easterly wind” [1,13]. Fernando Quiñones, for instance, commented on the delight of watching movies under the stars:

“The summer cinemas in Cádiz serve more for enjoying the coolness while having images before our eyes than for enjoying a movie (…) These cinemas in Cádiz have a great charm, and perhaps they are projecting a sensationalist polar report while the audience is watching the trees moving softly in response to the calm air, and the neighbors in the adjacent houses eating gazpacho and chatting with their girlfriends (…) Summer cinemas are truly charming because they offer us freshness and entertainment. They are joyful, with the joy of creaking wooden chairs, cool sand under our feet, and the wind on our faces, which is what makes it worthwhile (…) During the summertime in Cádiz, it would be great to have floating cinemas installed that could move along with the tide and good weather. This would allow us to start watching a movie in Cádiz and then finish it on one of the beautiful beaches, enjoying the splendid view of the silver bay, which is especially glorious to see under the moonlight.”[24]

Simultaneous to the Cinema Caleta, the Terraza Cinema used the lure of low prices at its bar and raffled roasted chickens among the audience [13]. This had happened since the early days of cinema in Cádiz and many other cities, as it aimed to spread the invention of the cinematograph3. In January 1898, “on the occasion of the cold fair, a small theater called Proyecciones Luminosas (Luminous Projections) was set up in the public street. To incentivize attendance, raffles were held for gifts amongst the audience, one of which was a trained horse” [13] (p. 32). During this early period, theatrical performances alternated with projections accompanied by music and a humorous narrator who commented on the images. The advertisements highlighted the brand of the new projectors, sometimes without mentioning the featured film, and indicated the device’s main attraction [13] (p. 32). We will explore the significant differences between current film perception experiences and the return to analog in a city where, as we announced, the notion of Eros is very present.

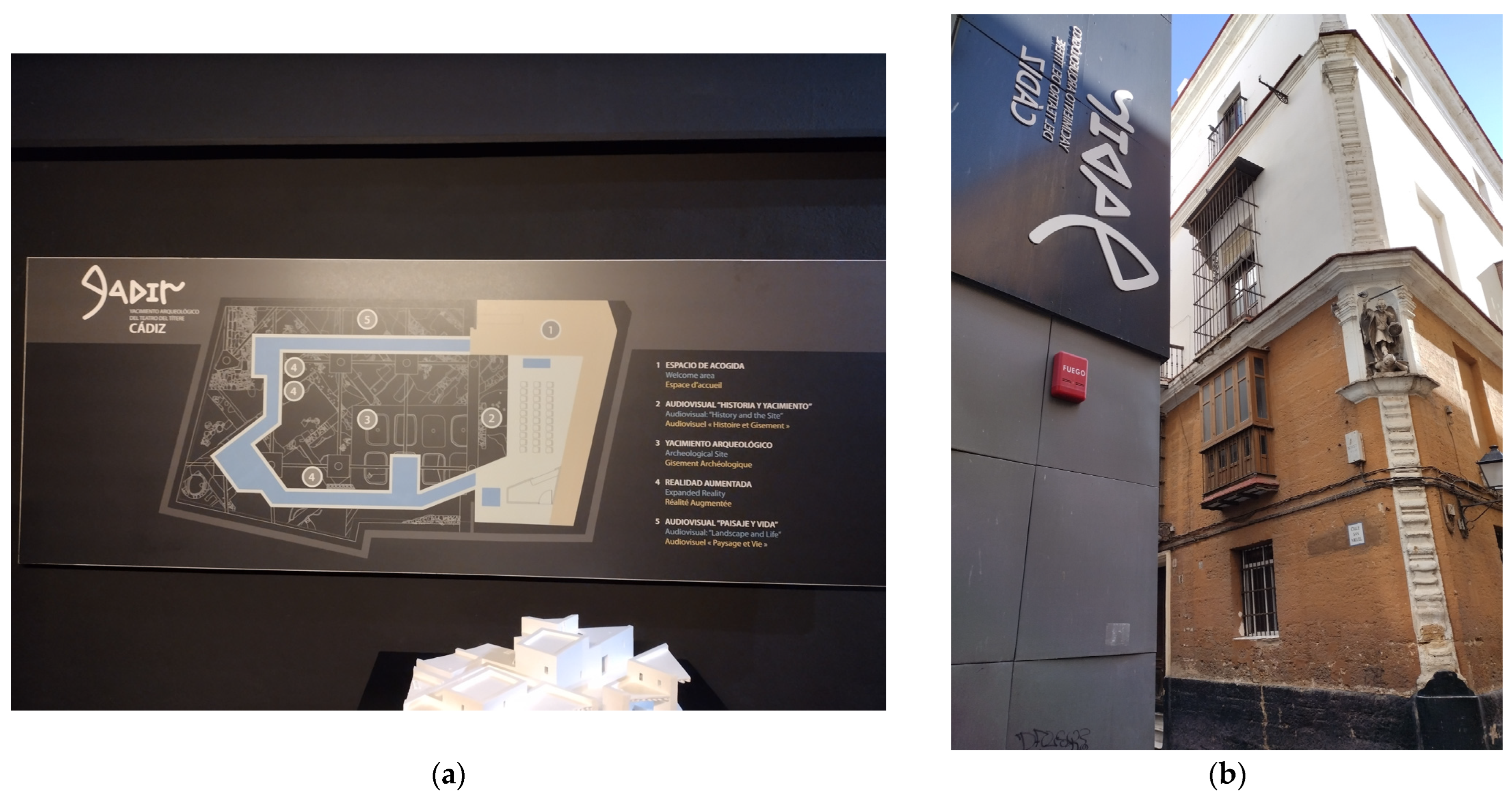

Another exciting aspect that connects the city with the collective imagination comes from archaeology [9]. Movie theaters have essential links to the city’s ancient history, as was evidenced when Cine Andalucía was closed down and replaced with a residential building. During the construction, a Roman-era salt factory was discovered, restored, and can now be visited. Another example that links movie theaters to archaeological sites is the current Títeres La Tía Norica Theater (formerly Cinema Cómico, Cinema Popular, and Cinema San Miguel) (Figure 3a,b). Underneath these movie theaters lies the Gadir site—a crucial site for detecting the Phoenician settlement in the city, as it contains the layout of streets, houses, and utensils from the 9th century BCE. The foundations of eight houses are preserved, distributed in two terraces, and organized around two cobblestone streets.

Figure 3.

An archaeological site beneath the San Miguel cinema: (a) a plan of the archaeological remains currently on permanent display beneath what is now the Títeres La Tía Norica Theater. Source: Inmaculada Rodríguez-Cunill; (b) an exterior corner of the Tía Norica Theater, with the Gadir site advertisement. The letters are arranged for reading through the rear-mirrors of cars. Across the street, you can find the statue of Archangel San Miguel, which gave its name to one of the cinemas in this location’s history. Source: Inmaculada Rodríguez-Cunill.

4. Discussion: Eros and the Transformation of Life through Movie Theaters

4.1. Eroticism

Numerous authors have written about eroticism, approaching it from philosophical or political perspectives. Some of these authors include Nietzsche [25,26], Martin Heidegger [27], Marcuse [28], and Levinas [29]. However, Georges Bataille is the most representative thinker, who has extensively analyzed the role of Eros in contemporary society. This Eros constitutes a foundation for transforming a simple hominid into a human being. In his essay, crucial to the subject at hand, Erotism [2], he proposes a series of concepts and ideas that can be used to analyze contemporary society from the viewpoint of love attraction and the impulse that humans have towards life in the face of death. His essay suggests that humans are discontinuous, due to how they reproduce, wherein each individual constitutes an independent being from the moment they are given life, unlike the reproduction of cellular animals, for example. This discontinuity drives humans to seek continuity through communion or congress with other human beings. Such a complete union is impossible, of course, but that does not prevent there from being experiences close to that union, in which the ego dies, even if only for a moment. That is what the erotic experience is about—the annihilation of the ego in favor of another being, separate from oneself, external to oneself, but who becomes essential. The other is always a challenge. They are incomprehensible, indiscernible, and impossible to possess, but from that impossibility arises life, interest, and passion—everything that leads human beings to go beyond themselves to seek answers, investigate, and create. These types of questions go beyond the sexual aspect, of course, but they are deeply anchored in it.

Human beings experience sex in a particular way. As Bataille explains through an interpretation of history and anthropology, humans are animals that, from their beginnings, are bewildered and overwhelmed by two fundamental experiences: Eros and Thanatos; sex and death. In both cases, Bataille argues, “they remain more or less disturbed and not knowing what to do, but their reaction always differs from that of other animals” [2] (p. 54). From death and sex, prohibitions arise—the basic interdictions of human beings—and depending on historical circumstances, a series of customs, ways of understanding the sexual and affective relationships, and religion, especially after the notion of “the majesty of death” [6], are formed. These prohibitions attempt to order sex and death as much as possible to prevent them from interfering with social order and work, so that a functional and organized human society can be built.

Throughout history, eroticism has flourished through transgression, while work and order have limited its potential for generating life. The transgression that eroticism implies has always struggled against the power that seeks to domesticate it. One of the traditional ways of trying to dominate erotic forces is through marriage. However, according to Bataille, marriage can escape this regulation as, even when it tries to regulate sex, it can also serve as a space to explore erotica more deeply. In short, history, with regard to eroticism, has been a game in which human beings have tried to lead erotic lives in defiance of social order’s dictates, which sought to domesticate that life to reduce it to the bare minimum, or to exploit its mere reproductive function.

Bataille defined eroticism as “the affirmation of life even in death” [2] (p. 15). Following this definition, Byung Chul Han highlights that this was an era where the existence of eroticism, that affirmation of life, became difficult, if not impossible [4]. On the other hand, the life to which Bataille refers is not just any life, but the good life (a rich life filled with intellectual and sensorial stimuli), confronted with what Han calls mere life (the dull life devoid of desire). The good life would be the life that seeks to be lived according to non-commercial parameters. In contrast, depending on our level, mere life would be dedicated to mere subsistence or the excessive pursuit of economic benefits from our efforts.

Han speaks of this agony of Eros, which manifests itself in many ways in our society. The city, where the condition of citizenship is exercised, is the privileged space where we can observe many manifestations of this agony of Eros. As we can see, the cinema interactions in Cadiz throughout the 20th century have shown a strong presence of Eros. However, we are also investigating its agony, as proclaimed by Han, and the possible resistance that was shown to this transformation.

We live in a time where the word eroticism is often associated with pornography [30], even though its philosophical meaning is in a very distant, significant space. We have started with a historical and social contextualization of a city with a strong presence of Eros in a philosophical sense. This does not contradict, however, the fact that once the democratic transition began in 1984, the Cine Nuevo became the first X-rated cinema in Cadiz, following the enactment of a Decree-Law in April 1983: “Art. 9. Films of a pornographic nature or that promote violence will be classified as X-rated films by Resolution of the Ministry of Culture, based on the report of the Classification Commission, and will be exclusively shown in special theaters, known as X-rated theaters (Article 1. of Law 1/1982)” [31]. Three years later, the Cinema Nuevo closed its doors to be remodeled into a multiplex [13].

4.2. Interruption as Life

Let us compare the erotic sense described by Bataille with the circumstances found in movie theaters, as we recall in 3.4 Performativity of the audience in the cinema halls in Cádiz. We can say that, in general, life appeared when the screening was interrupted.

“The film screenings were interrupted, usually to allow time for the celluloid reels to be changed in the projection booth, and for the audience to smoke a cigarette, chat, or consume something in the theater’s refreshment area4, which was announced on the screen. These unpleasant disruptions of the film narrative were used to project glass slides with advertisements from commercial companies.”[1] (pp. 25–26)

This life has to do with a love for cinema, which was part of the school year. The first campaign for School Cinema in 1954–55 attracted 21,000 students in 72 film sessions at the municipal hall [13] (p. 134). The expansion and multiplication of theaters and projection venues can be seen in the early 1960s, with 14 theaters used for a small city and 16 cinemas used during the summer of 1965. The golden age of cinema was about to fade, because a powerful competitor arrived in Cadiz, ready to grow and attract viewers: television. However, the arrival of TV signals faced many setbacks. The Portuguese signal from Faro would sometimes reach Cadiz, and occasionally, there were “spots” from France and Italy. Only when construction work was carried out to install a transponder in the village of Guadalcanal would Spanish television reach Cadiz. Spanish television was founded in 1956, but it would take until October 1961 for the few television receivers in Cadiz to offer any images. Local Cadiz newspapers spoke of the disruption to daily life caused by television. La Voz del Sur published an unsigned article on 10 December 1950, titled “Television threatens to end cinema”: “Millions of Americans (there are already more than five million households with television) prefer to stay at home watching a parade of still-imperfect images (…) people who used to go to the cinema once or twice a week now stay at home, or go to their neighbor’s or the nearest bars. It is a kind of social epidemic that affects not only the film industry but also restaurants, housewives, schoolchildren, etcetera” [1]. However, currently, the need for storytelling persists. It is not that the love for cinema has diminished; instead, it is consumed in diverse ways.

4.3. Technical Improvements in Cinema’s Effect on Audiences

It only took time for the otherness found in movie theaters to dissolve into a path toward the narcissistic solitude that Han commented on. Just before the Civil War, a new relief image system called Audioscopik was projected in the film El Rayo de Acero (The Steel Ray). The audience was given two-colored glasses, but this technical feat did not impress the public.

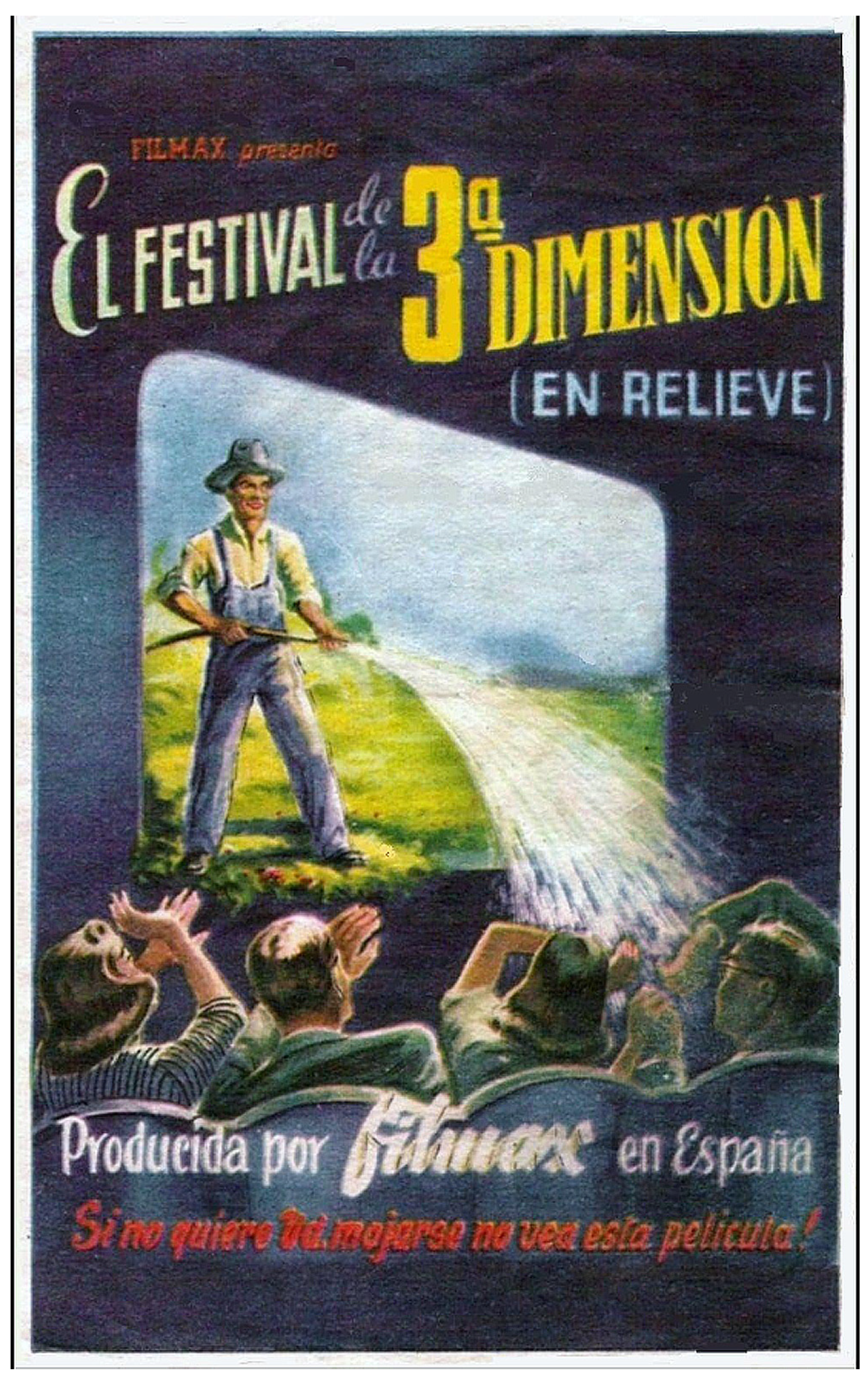

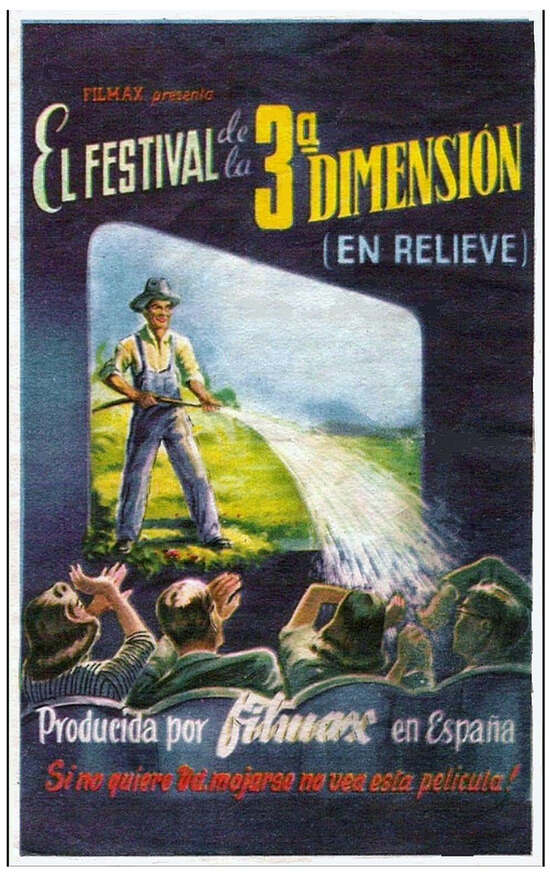

Contrasting the imperfection of television images, from the beginning of cinema in Cadiz, local journalistic articles insisted on technical improvements5, such as the size of the frames, the colorful chemistry in films, projector optics, the dimensions of projection screens, stereophonic sound, and three-dimensional images with reliefs. The idea of “the scientific” and “progress” advanced through the technology that was advertised and was supposed to meet “social demands”. The “3D Festival” (Figure 4) significantly impacted the city in October 1953.

Figure 4.

Poster of the movie directed by Luis Torreblanca. 30 min. 1953. A short documentary filmed with the 3D system, divided into three parts: (1) “Al alcance de la mano” (at hand) (miscellaneous effects), (2) “Desde la Barrera” (bullfighting scenes), and (3) “Baile español” (dances in El Retiro Park). Available at http://documentitosdeunindocumentado.blogspot.com/2022/02/cine-espanol-en-relieve-cosecha-de-1953.html (accessed on 28 September 2023).

This genuinely Spanish technical invention (the national version of Technicolor was “cinefotocolor”, which did not have much success) influenced the phenomenological experience of the spectators [33]. Specifically, in Cadiz, the news insisted that the audience return the glasses6 in the best possible condition, thus avoiding increasing ticket prices for future spectators. On the other hand, columnist Donato Millán insisted on the future possibilities of this technology and put forth the not-so-farfetched idea that spectators could “coexist with the actors inside the movie”, even if it meant watching projections “in many dimensions and without any common sense”. In fact, throughout his columns in 1954, he recalled that thirty years earlier, images with colored glasses and some experimental 3D short films had already been seen in Cadiz, and that mediocre films that would have gone unnoticed received public acceptance because they were projected with the novelty of relief and made the audience feel “that the images were coming out of the screen” [1]. That attempt to make the images come out of their frames and become part of the reality of the spectators was present in the advertising for the Third Dimension Festival (Figure 4), where the following could be read: “If you do not want to get wet, do not watch this movie”. At the same time, as Figure 4 shows, a man on the screen sprayed the seated spectators with a hose. From the old fairground booths, attempts to mix representation (within a frame) with presentation (the real world, the present where the spectator lives) had been developed using various technological devices [34]. In 1953, in Cadiz, there was the possibility of immersing oneself in the representation of the projection (Figure 4), and the following year, that same incitement served to spur the population, this time with the inauguration of the first panoramic screen.

“Numerous systems had been setting milestones in the first steps towards this great novelty, which soon would be presented to the people of Cadiz in one of its most perfect forms: the Panoramic Screen adopted by Metro Goldwyn Mayer. The lion of MGM had let out its most resounding and spectacular roar, and this time, the viewers would squirm uneasily and justifiably alarmed in their seats because the familiar and precursor wild beast of great successes was going to materialize out of the screen and behind it, taking shape and substance, Robert Taylor and Deborah Kerr in the most excellent film ever made after Gone with the Wind.”[35]

The following year, the first film in Vistavision was screened at the Andalucía Cinema-Theatre [13] (p. 135).

In short, the idea of progress, science, and technical advancement through improvements in movie screening was an attempt to associate technology with positive values, even for the less literate audiences, which would create a seed for behavioral modifications that would lead to profound changes in the collective experience of cinematic narration in the long term. These types of changes were intellectually encouraged: the audiences not only wanted to watch but also wanted to know how to watch, and the sale of small visualizing devices began. Through the revival of stereoscopic photography, which had already had great international success since 1851, a high-performance viewer for viewing collections of stereoscopic photographs arranged on inserted discs became popular in Cadiz, available at affordable prices (Figure 5). From the collective experience of being in a cinema, we moved to a manageable experience of visualizing, popularized at cheap rates. We witnessed the first steps of an aesthetic experience that would culminate in a new paradigm, where Eros would dissolve7.

Figure 5.

View-Master. Exterior and interior view (with inserted disc) of the View-Master. Source: Inmaculada Rodríguez-Cunill.

In another vein, it is necessary to point out how the cinema opened a field for entrepreneurs. In 1953, advertisements for “Cine Sonoro a Domicilio” (Home Sound Cinema) appeared, with special portable equipment, a series of films, and feature-length movies and projectors suitable for schools, casinos, and cultural centers. This aspect has been present since the beginning of cinematography. Commercial uses, not only for projection but for other purposes, implied that a local business field was opening up.

4.4. Political Influences on Film Screenings

The tumultuous 20th century in Spain allows us to delve into the signals by which passion or desire became part of the audience’s interaction in theaters. From the beginning of cinema, a darkened theater posed a problem for “young ladies”. During the Second Republic, which began in 1931, there was a period of two years (1933–1935) where the Catholic right wing was in power—this period contrasted the first two-year period of Republican-socialist rule, which was more open towards personal freedoms. The Catholic right wing tried to eliminate the modernization efforts that had been made during the first Republican-socialist rule. It is understandable then that a typical film featuring “sensationalism” was scheduled, advertised with a supposed scientific character by several “wise professors”, but also requesting “the absence of ladies” [13]. During those two years, cinematographic achievements uplifted the national spirit. Finally, a Spanish film, Agua en el suelo (Water on the floor) (1934), premiered at the Gades cinema. The fact that the CEA studios in Madrid and the distributor CIFESA (Compañía Industrial Film Española SA) presented this film fueled Spanish sentiments [13] (p. 103).

With a civil war brewing (1936–1939), movie theaters became a stage for political confrontations. Prior to the war, when the German film Casta Diva (1935) was screened, preceded by a German newsreel featuring Adolf Hitler, the press reported that a “fierce struggle between disparate elements” took place without any intervention from the authorities, as had happened in other scandals. This social and political radicalization would soon culminate in the tragedy of the civil war [13] (p. 105). The screening of The Battleship Potemkin (1925) by the General Association of Orchestra Conductors to raise funds for unemployed musicians catalyzed civil confrontations that would hasten the war [13] (p. 106). The same association screened Soviet films shortly before Franco’s nationalist uprising.

The day after the nationalist uprising on 18 July 1936, cinemas were closed for thirteen days and reopened as “national cinemas”, meaning Cadiz was unaware of any film production from the Republican zone. Additionally, during the shooting of the film Asilo Naval in Cadiz (which would not be released until 1944), the materials, technicians, and filmmakers were placed at the service of the military to produce war reports and propaganda in favor of Franco and against the Republic.

In 1938, amidst the war and with Cadiz under the control of the fascist regime that staged the coup d’état, predominantly, documentaries were screened. On 9 July, Hitler’s Trip to Italy was shown. The subsequent chronicle in Diario de Cadiz magnified the work of the far right: “Parades, displays revealing Italy’s potential, magnificent naval and aerial maneuvers, in short, all the events held in honor of the German Chancellor are presented with the splendor and fervor that the promoter of universal peace imprints in this solemn international hour. The viewer also proudly witnesses the act in which Mussolini, in Genoa, pronounces solemn and encouraging words for Franco’s Spain. The film, one of the best in its technique and presentation by the Instituto Luce, was underscored with constant and enthusiastic ovations” [19] (p. 61).

During the civil war, the limited cinema produced had noticeably clear intentions of indoctrinating subjects, praising military victories and historical heritage, and combating the “dangerous” red enemy [19] (p. 58). Cinema was controlled and dependent on Francoist interests, which was a prelude to what would unfold in the coming years of military dictatorship. Cinema from Germany and Italy, which were aligned with the Franco regime, was prioritized.

During the Franco era, cinematographic proposals were imbued with a conservative language (“Cult and moral spectacle” and “Aristocratic-religious film week”) [13] (p. 12), although the 1950s represented a particular opening. This is why a Japanese film, Rashomon, could be seen for the first time, although the audience, unable to understand it, laughed at the film. However, Francoism had led to a more constrained society, so it is not surprising that it was reported in the press that the Spanish film that won the Cannes Film Festival in 1955, Death of a Cyclist, although it surpassed the censor’s apparatus and was praised as excellent by critics, seemed daring to a large part of the public, “due to the scandalous nature of the subject” [13] (p. 135). During these years, the great success of a film like Lady of Fatima (1951), which included a direct speech from the Virgin and had a record of 45 consecutive screenings over 14 days, manifested the influence of Catholicism within the Franco regime. It was only surpassed the following year, with 22 days of screenings, by the highly anticipated Gone with the Wind (1939). This indicated Spain’s shift in international politics, particularly its openness to American infiltration.

It is important to note that the efforts to screen quality films in the face of the massive demand for entertainment products were parallel to the popularization of these devices and the advance of technology. This led to the creation of film clubs in Spain. In the case of Cadiz, after several appeals in newspapers by columnists, a University Film Club was inaugurated on 5 December 1953. It seemed to be a space for socialization again, but not for the working classes, not “a social melting pot”, and where women were even welcome. In the same year, articles of the Mundo Film Club appeared. The reaction against the pure spirit of fairground entertainment to delve into more “pure” film issues had much to do with the relationship between high and low culture and street or institutionalized carnival. However, it was also a focus of new ideas that had to be controlled by the censoring apparatus of the regime, so the Ministry of Information and Tourism issued an order with the rank of law creating the Official Register of Film Clubs. By registering the film clubs, the State encouraged them to “improve their influence on the moral education of the viewers” [36]. Numerous actions of the Francoist regime were channeled through cinemas in the 1950s, such as the Youth Front Film Club, Youth Cinema, and the Movement Film Club. Other screenings were organized to honor the regime on cruise ships that docked in the port of Cadiz, inviting orphaned children to watch movies in their onboard projection rooms (as part of the media operation under the Madrid Agreements of 1953, in which Franco ceded Spanish territory for use by the United States government: the naval base of Rota, a few kilometers from Cadiz, on the other side of its bay).

4.5. How Does Eros Agonize?

The film screening room highlights Eros’ agony on a global scale. How have the transformations of performative interactions occurred, and how have they led to the manifestation of this agony? Can we detect resistance in its definitive establishment, especially in the city in question? First, we must clarify more of Han’s concepts.

4.5.1. The Evolution of Eros in the New Millennium According to Han

A vast social change has occurred in recent decades, long after Bataille published his book in the late 1950s. In this change, power, understood as the economic (more) and political (less) forces that shape society, mixed with the development of communications, has been refining the way to eliminate eroticism as a life-creating force so that human beings focus on work and productivity. According to Byung-Chul Han, the destruction of eroticism has arrived; eroticism is agonizing for many reasons. First, we do not recognize the otherness of other human beings [4] (pp. 6–7). Moreover, what is otherness? Otherness is the awareness that all other people are just that, others, completely elusive, irreplaceable, and completely free. This awareness that the other will always be another and that we can never fully grasp them is what allows desire to exist, the erotic need to complete oneself with others, to seek the continuity of my discontinuous body, knowing that I will never achieve it because others are different from me, they are. Therefore, I cannot/should not invade their space, freedom, and uniqueness, and ultimately possess them.

For Han, this is a unique and essentially narcissistic moment in history, in which the neoliberal ideology of maximum economic profit and maximum efficiency governs us, which implies a total valuation of work above any other desire that may threaten its status as the sole engine of society. This leads to a lack of recognition of the other as something distinct from myself, but only as an extension of the self that must be at my service and fully aligned with me in the pursuit of maximum efficiency. The other should never be a source of pain or contradiction, but a source of constant pleasure. Relationships are based not on erotic attraction to the other, but on the simple pursuit of satisfying my preferences. Thus, at most, symbiotic relationships can occur where there is no struggle or violence or parasitic relationships, and where there is no confrontation either. The other ceases to exist as an enigma and becomes merely a means for my pleasure and goals. The concept of love is reduced to sex, and sex, as a field of conflict between such otherness, is reduced to a simulation in which eroticism is replaced by mechanism and quantitative analysis.

In contrast to the free and transgressive Eros that can cause pain and doubt, pornography is established [4]. In this context, the exploration of pornography serves as an illustrative example of an issue that may inadvertently trigger Eros at a surface level, as proposed by Byun Chul Han. Nonetheless, this serves as a peripheral point, limiting rather than thoroughly delving into the contentious topic. Some additional insights would be beneficial. Pornography is organized, has its channels and its laws, and is designed to please the consumer, and there is no transgression or doubt (the only annoyance it produces is against small bourgeois customs, but it does not question the social system or challenge individuals beyond forcing their catalog of so-called good customs). Additionally, it can be bought and sold and falls within the logic of work in that those who create it are workers. Erotic items are also commercialized and fall within this order of work and trade. A relationship with things, objects, images, and artifacts replaces the erotic relationship that presupposes alterity. In this new situation, the relationship is always at the service of something else that is concretized and defined as an orgasm, to which, at most, so-called preliminaries, lacking value in and of themselves, are added. The number of orgasms is quantified, and their quality is established. The G-spot, clitoris, or penis are discussed as places, things, or objects, where the erotic experience is concretized, precisely to dominate this experience and reduce it to the scarce ten seconds that the orgasm lasts. A novel such as Fifty Shades of Grey [37] was translated into Spanish as Cincuenta sombras de Grey, losing the double meaning of the words shade and grey. In this novel, every movement is valued, where there is no eroticism, but rather a transaction of actions and pleasures that are sold as erotic, even though they are only pantomime and simulation [4] (p. 14). Shades of gray suggest the same material, intended to be dark but whiter than a first communion suit. The conflict of going out to flirt—with the consequent possibility of failure—is replaced by websites like Badoo or Tinder. We reduce the possibility that our partner may not be as we expected by signing up for Meetic or E-Darling. The polite and mercantile exchange of partners is esteemed as a way of living in sexual freedom. Married people who want to avoid conflict with their partner can sign up for Ashley Madison or Victoria Milan (names that could be on the cover of any 19th-century romance novel) to have a discreet affair that undoubtedly will not take them to the Orinoco jungle but, more likely, to a quiet hotel room with three or four stars, paid for with a credit card, not a gold one but, this time, gray, like the color of shade (an adventure or simulation thereof, which again will be confined to the circle of work, efficiency, and profit). As we have indicated in recent examples, this need to reduce risk in relationships is also seen in attempts to minimize the risk or minimal consequences of any disease in our lives. It is not about wearing a seatbelt to avoid the consequences of car accidents or dressing warmly to avoid catching a cold, but the neurosis for security and health that prioritizes security and health over freedom [4] (p. 19). We are attentive and alert to the flu, cancer, heart disease, obesity, cholesterol, uric acid, lack of exercise, and COVID-19 (which had not yet appeared when Han published his essay). If we are sick, we seek ways to bypass the symptoms, putting the actual cure of the disease on the back burner in order to continue working, or even denying ourselves the possibility of getting sick, because that is seen as a weakness—something that the system also makes clear by cutting down on sick leave options—especially if we are self-employed, which Han dedicates a considerable amount of space too. If necessary, we externalize our internal conflicts and give them the name of a psychological syndrome, so that the annoyance of returning from vacation is now called post-vacation syndrome, for which treatment can be found, instead of trying to accept it as frustration or, worse, turning it into anger towards work. Moreover, going further, we settle for a small salary that provides us with enough to eat and do not protest because, in the current situation, it is not good to take risks. We do not confront power for fear of what we might lose. In short, we want to forget that going to certain places and engaging in certain activities carries risks. We want to fly in airplanes but eliminate the risk of crashing. We want to go bungee jumping but eliminate the risk of the rope breaking. We want to attend crowded parties and fairs but eliminate the risk of being crushed to death. All risks seem like anomalies to us when, in reality, many of them are logical consequences and corollaries of our behaviors. If we lived life more erotically, we would be more willing to face those risks and decide if it is worth risking our lives to fly, bungee jump, go to a football game, or attend a popular festival.

In some cases, it may be worth it; in others, it may not. However, those who live an erotic life do not dismiss the negative consequences of their actions and take them into account as a possibility. To be sure, living entails the possibility of dying, but we live a cowardly life because we are increasingly incapable of taking the risk of dying. Moreover, as Han indicates, only those not afraid to die can live freely. The enslaved person would rather remain an enslaved person than face the threat of death. In Han’s own words, “Eros, as excess and transgression, confronts both work and mere life. That is why the slave who works and clings to mere life cannot have erotic experiences, erotic desire” [4] (p. 36).

Han believes that the self-employed worker figure, mentioned earlier, is the final step towards creating a passive and fearful mass lacking courage and sensuality. This figure is highly praised and valued by neoliberalism, as it encourages individuals to become their own exploiters. By doing so, they become unable to confront their oppressors. The same person is both an enslaved person and an exploiter and is doomed to succeed; that is to say, one demands oneself to achieve some goals, whether or not they are compatible with the good life. After establishing this figure, Han proceeds to analyze it further in his book The Burnout Society, insisting that humans only seek to ensure survival and live a mere life without contradictions. A life without liveliness fears contradiction, paradox, and failure because it fears death [38].

4.5.2. Eros and Aura

The concept of Eros can be related to another concept introduced by Walter Benjamin, the German thinker from the Frankfurt School, to refer to how we perceive art. Benjamin was concerned, throughout his life, with the relationship between humans and objects and humans and society embodied in the contemporary city. These ideas are developed in several of his works, although the most important and well known are his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” [5] and the work known as Arcades Project [39], an unfinished and labyrinthine work composed of thousands of quotations and notes on the subject of the city, embodied in Paris.

One of the fundamental concepts introduced by this thinker is that of aura. Aura can be defined as the eroticism of objects. In saying that aura could be the eroticism of objects, we run the risk of someone confusing aura with fetishism, understood in the sense that this word has within it sexual behaviors. However, as with the concept of eroticism concerning pornography, as we will see below when speaking of the eroticism of objects, we are not referring, in any case, to the sexual or rather genital connotations that some give to this type of concept.

In this sense, when Benjamin speaks of aura, he is referring to the character that objects have as works of art, not to their ability to serve as objects of sexual arousal in their presence. Benjamin introduces this concept when discussing how the reproduction of artworks through photography and other mechanical means had changed the perception of art. Benjamin says that the aura is the “unique apparition of a distance, no matter how close it may be” [5] (p. 56). At an earlier point in the same essay, to better explain his idea, he says that “even the most perfect reproduction is lacking in one thing: the here and now of the work of art, its unique existence in the place where it is located” [5] (p. 53). Thus, for a work to be artistic, it must have an aura; that is, it must be unique and have a certain distance, a space that can be defined in terms of distance or time but also in terms of function. This way of describing the aura is reminiscent of what we have said about the need to recognize otherness and be aware of the insurmountable distance that separates people, considering the other as a free, unique, and unrepeatable subject. Benjamin, who committed suicide on the Spanish border, was himself an admirer of the Spanish joy of life that he had experienced on holidays. Of course, eroticism remains the exclusive domain of human beings. That is to say, the Mona Lisa may have an aura, but not eroticism. Alternatively, in other words, we can feel that our relationship with the painting is auratic, but saying that it is erotic would imply attributing human qualities to it that it does not possess. Perhaps it is advisable to make this clear in a world that still confuses eroticism with pornography and that tries to attribute erotic qualities to objects as a commercial strategy, to the point that pornography is now the first model to follow in the sexual education of many teenagers.

What is defined as the agony of Eros in the world of human beings can be defined as the death of aura in the world of art. Digitization, combined with the distribution of works on networks, makes their aura almost disappear entirely. The high-definition quality and immediacy offered by internet distribution eliminates practically any distance [4] (p. 31). It is interesting to note that the pornographic industry, which is the opposite of eroticism, is at the forefront of using the highest possible image quality. They were the first to adopt 4K or UHD production, and their demand for effective distribution systems has driven technological advancement.

Continuing with the line of thought that connects us with Benjamin’s ideas, let us explore how digitization impacted public spaces crucial for coexistence during the 20th century. We will also examine how digitization has brought about changes, particularly in the first few years of the 21st century [40,41].

Today, with the digitalization of film projection, it has become easy to forget about celluloid projection. There are no longer any cuts in the film or tremors on the screen caused by the engine’s vibrations. Scratches, changes in texture, or differences in color from one reel to the next are also absent. Even the sound is uninterrupted, with no extraneous noises or clicks caused by the wear of the audio tape on the celluloid. However, in an environment like the city of Cádiz, it feels as if the soul yearns for the return of analog imperfections to make the experience an encounter with the other.

The picture and sound quality of every film is identical on every screen, whether it is being played in the studio where it was initially produced in Hollywood or Paris or a cinema hall anywhere else in the world. Undeniably, we have achieved technical perfection, and can now enjoy cinema with exceptional visual and audio clarity, irrespective of the viewing location. However, in exchange, a fact has been spreading from big cities to the periphery since the 1980s. The contemporary state of cinema has been marked by a shift towards technical proficiency at the expense of its erstwhile sociocultural significance. Once a hub of collective engagement, the cinema hall has been reduced to an antiseptic space that prioritizes formal perfection over the potential for dialogue, debate, and dissent. In this present-day context, the transformative power of cinema as a catalyst for social change has been diluted, if not altogether diminished.

The viewer has been convinced that the important thing about watching a film is the technical perfection of the screening, not the social aspect. In addition to enthroning the technical quality of the screening, the old cinema cafeteria (ambigu in Spanish) has been replaced in most cases by a fast-food restaurant-type bar. Of course, it is not that technique is unimportant, or that selling popcorn is terrible. What we are referring to, concerning the ideas we are trying to develop in this article, is the fact that technical (screening) and economic (selling the most popcorn and other knick-knacks) supremacy leaves little room for the social character of both acts (watching a film, eating popcorn, and sharing it). Part of the progressive loss of cinema-goers comes from that side. If what matters is technical quality and just eating popcorn, it is enough to do it at home. In modern times, home cinema systems have advanced so much that they can provide an audiovisual experience rivaling a cinema’s. This has led to a decrease in the number of people who choose to venture out to watch a movie. The idea of being in a room with unfamiliar individuals, facing uncomfortable seating arrangements, or being obstructed by someone tall can be a deterrent.

The duality of presentation/representation arises when we combine the idea of being present, alluding to senses such as smell, the warmth of bodies, and the breathlessness of respirations, with watching movies that represent another reality. The superposition of presentation and representation creates an analogical otherness that has been widely reflected upon in the context of art forms like installation or happening. However, with the advent of virtualization, this intrusion of representations–presentations can be seen as the opposite of augmented reality.

The viewing public has developed a refined palate when it comes to entertainment. Regrettably, this evolution has been influenced by the notion that a film’s technical components are paramount and the promotion of excessive snacking. Consequently, the chance to partake in a collective and enjoyable encounter has been obscured. In fact, to the extent that the exhibition space has ceased to be social, it has become an anodyne place, lacking in aura. We have already referred to converting the former ambigu into a hamburger franchise bar, but the cinema has also succumbed to this technological imposition. The cinema is no longer beautiful, just like every other cinema in the world: a greyish carpet covers the walls of a quadrangular space where armchairs are placed precisely like in any other multiplex. Despite this, cinemagoers miss the social character of film projection. Proof of this is how, in Spain, the so-called cinema parties (in which films are accompanied by other types of entertainment, like live music, costumes, and the possibility of singing along with the music on the screen) succeed. The allure of socializing within a cinematic space that provides an array of amenities beyond the mere projection of films continues to captivate individuals. We look for unique events because we want to have the possibility to relate erotically in a specific area.

On the other hand, let us remember that in a society of exhaustion, with individuals focused on their performance, joint action, courage, and collective identity are also atrophied [38]. If movie theaters lead us to narcissistic consumption, centered on the self rather than the shared spectacle, the loss of Eros is a fact. The isolated experience to which the technological perfection of movie theaters leads us eliminates the relationship between Eros and politics, the possibility of change, and the narrative tension (which is not only in the plot of the movie we are watching). In essence, elucidating these issues cannot be achieved by merely examining consumption data. They lead to the development of a theory of the significance of the effects of life in the non-analog environment. Therefore, it is an aesthetic question and a matter of the transcendence of being, a confrontation with the crisis of the spirit, that we witness in this abyssal paradigm shift.

In another vein, we detected analogical and pseudo-analogical resistances. The evolution and transformation of social needs during leisure time and entertainment also adapt to the technological innovations that allow for social interaction and sound isolation. There was a hidden and forgotten cinema from the Franco era in the center of Cádiz. This discovery is a common occurrence when digging into the ground, similar to the discovery of archaeological sites, which Landi compares to the encounter with the past that involves La Bombilla Cinema: “If this were part of a script, it could be said that someone has discovered a hidden summer cinema, abandoned and concealed in the heart of the touristy old city of Cádiz, and it would be forgiven. With a history of over 2700 years of human presence, 80 years might seem insignificant. However, it was the life of many who experienced the most astounding reality one can imagine—open-air movies on a summer night—on the screen, and in the eyes of their companions.” [42].

In the case of the future La Bombilla Cinema (Figure 6), located in an abandoned lot in the center of Cádiz, obtaining urbanism permits depends on the sound isolation of the projection project [43,44]. However, this isolation relies not on walls but on the spectators’ ears. Thus, the experience of a summer cinema (this time with movies from the 1950s, which was the post-Spanish Civil War era, when such outdoor cinemas operated) is only possible with sound isolation: an individual device in each spectator’s ears, like those used for explaining monuments in crowded spaces with many visitors (wireless audio guides). The outdoor setting also implies that the screenings will only occur at night.

Figure 6.

Panoramic view of the future open-air cinema La Bombilla in the center of the city of Cádiz. Source: Inmaculada Rodríguez-Cunill.

The privately owned cinema, La Bombilla, provided refuge for many citizens during the 1947 explosion in Cádiz. Today, the cinema has been revamped, maintaining its historical roots, and is now a distinctive venue for social gatherings. It is worth mentioning that access to the cinema is only possible through the bar, La Bombilla, located within the same building (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

La Bombilla summer cinema: (a) access to the cinema from Libertad Street. Source: Inmaculada Rodríguez Cunill. (b) Access corridor (50 m) to the interior of the vacant lot where the La Bombilla summer cinema is planned to be located, with posters of movies from the era. Source: Inmaculada Rodríguez Cunill.

5. Conclusions and Coda: Other Spaces Where Eros Has Been Transforming Itself

Our study demonstrates a significant transformation in social dynamics within cinemas. Our investigation primarily focuses on the city of Cádiz; however, the conclusion we have drawn applies to other cinematic spaces. It is important to note that our findings are not limited to this particular location and can be extended to a broader range of settings. Our analysis verified how cinemas functioned historically as vibrant communal spaces that fostered collective experiences and interactions. However, in the present day, these interactions have evolved towards more individual experiences, reflecting broader societal shifts toward a self-centric focus. This change is indicative of the agony of Eros, as conceptualized by Byung-Chul Han, where a more narcissistic solitude overshadows the communal aspect of Eros.

Technological advancements in cinema have played a dual role. While they have enhanced the cinematic experience through objectively improved imagery and sound quality in terms of color, contrast, dynamic range, noise absence, et cetera, they have also contributed to converting cinema halls into spaces of technical execution, rather than social gathering for audiences, thereby altering the traditional erotic experience. This development aligns with Bataille’s notion of eroticism, where these apparent technical improvements increasingly challenge the pursuit of a deeper connection and continuity through shared experiences.

This research confirmed the agony of Eros, proclaimed by Byung Chul Han in the context of contemporary cinematic spaces. Eros, traditionally associated with physical and emotional connectivity, is transforming in response to changes in social values and technological advancements. This has led to a redefinition of the erotic experience within the public realm of cinemas, where interpersonal connection and collective enjoyment are being modified.

The historical context of Cádiz’s cinemas and their evolution into modernity are intricately interwoven. The city’s unique history and cinemas have played a crucial role in shaping the manifestation of social interactions and erotic experiences within the context of cinema as a space for entertainment and social engagement. Understanding this historical perspective is critical in comprehending the current status of cinema as a social platform.

The results of this study have important implications for the future of cultural spaces in urban areas. Cinemas serve as more than mere buildings for screening movies. They embody the essence of societal transformations in technology, Eros, love, and communal spaces. Cinemas have long been at the forefront of new technological advancements and their impact on society. They have also significantly influenced how people perceive and experience love and romance.