Instruments to Assess People’s Attitude and Behaviours towards Tolerance: A Systematic Review of Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Search Strategy

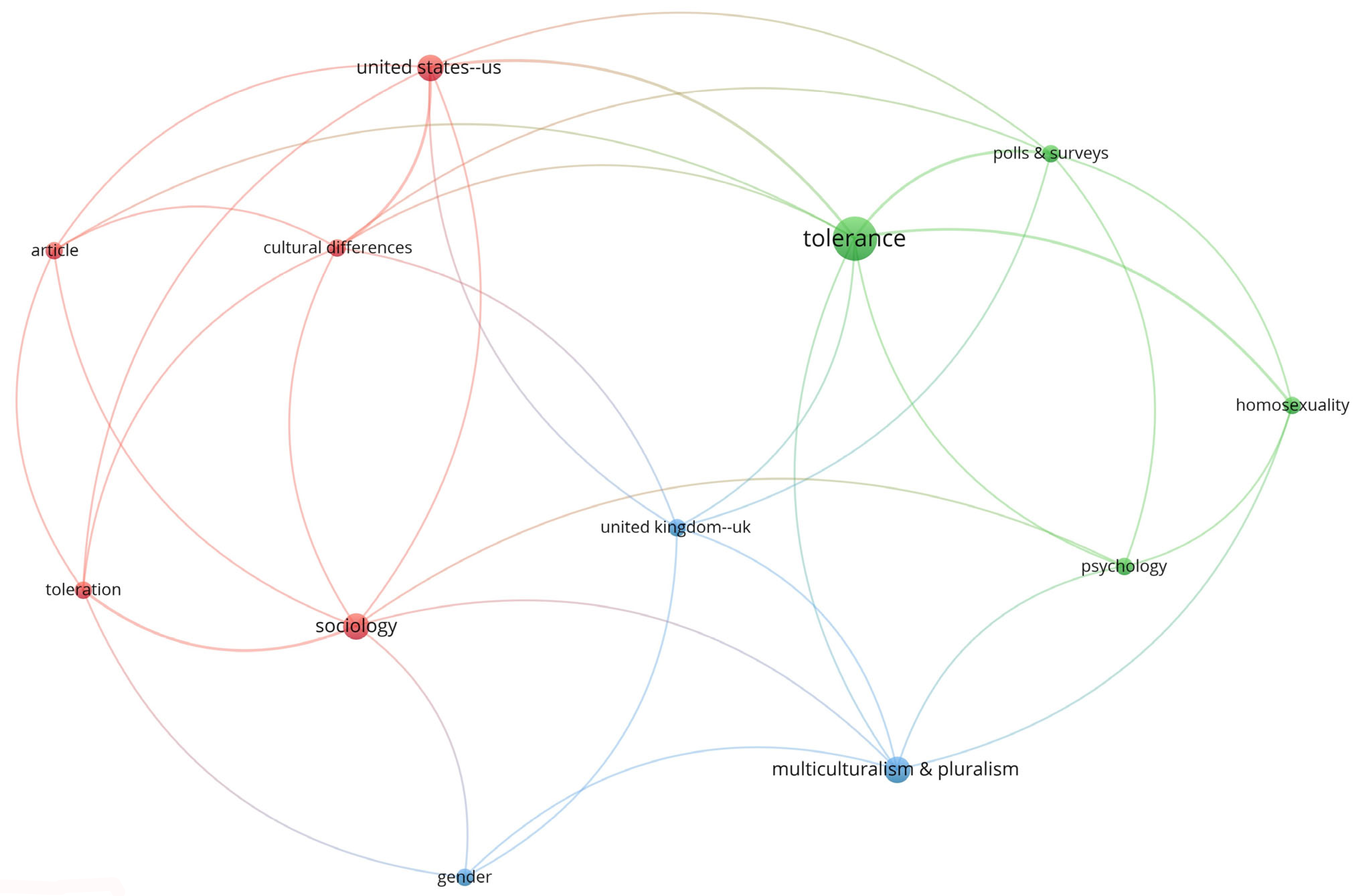

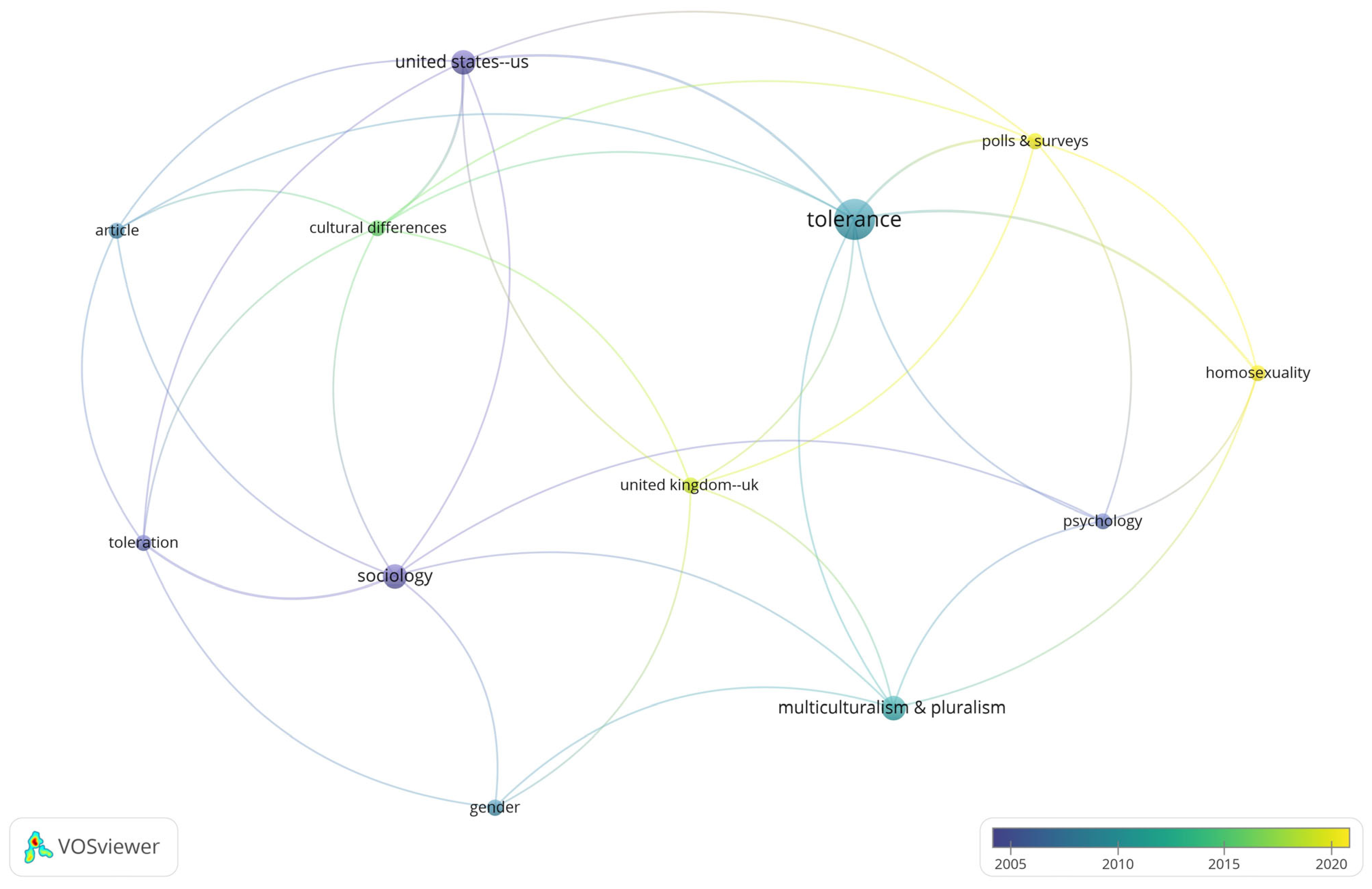

3. Results

3.1. Political Tolerance Scale

3.2. Cultural Tolerance Scale

3.3. Ethnic and Racial Tolerance Scale

3.4. Racial and Religious Tolerance Scale

3.5. Gender and Sexual Tolerance Scale

3.6. Social Tolerance Scale

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Number | Title | Authors, Year | Study Characteristics | Study Location | Sample Characteristics | Sample Count | Aim/Dimension Explored | Tolerance Scale Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | An Alternative Conceptualization of Political Tolerance: Illusory Increases 1950s–1970s | Sullivan et al., 1979 [28] | The study design in this paper involves conducting two independent surveys in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, during the spring and summer of 1976. The surveys included two independent random samples of size 300 each, selected from the Twin Cities’ city directories. Interviews were completed with 200 persons using the old questions and with 198 persons using the new questions. The study design can be characterised as observational, cross-sectional, and comparative between the two sets of questions used in the surveys. | Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota | The study population consisted of adults from Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, with two independent random samples of size 300 each being selected from the Twin Cities’ city directories in 1976. | 398 | To propose an alternative conceptualisation of political tolerance, introduce a new measurement strategy, challenge previous methods of measuring tolerance, and provide new findings based on this revised approach. | The tolerance scale measured in the study is a content-controlled measure where respondents selected the group they liked the least from a list of potentially unpopular groups and were then asked a series of questions testing their willingness to extend civil liberties to that self-selected group. This approach allowed for a more personalised and context-controlled measurement of tolerance. |

| 2 | The Sources of Political Tolerance: A Multivariate Analysis | Sullivan and John L, 1981 [29] | Observational study. | United States | Education Age Religion Sex, size of city, and region | 1509 | To address the problems in previous studies on political tolerance by using a content-controlled measure of tolerance and a more fully specified multivariate model. | The tolerance scale measured in the study is a six-item political tolerance scale, with scores ranging from 6 to 30 and a coefficient alpha of 0.78. |

| 3 | The Illusion of Political Tolerance: Social Desirability and Self-Reported Voting Preferences | Brown-Iannuzzi et al., 2019 [30] | Between-subjects design, nationally representative sample, random assignment to three conditions, traditional self-report, indirect measure using UCT. | United States | American adults Sample size of 3000 Data collected in June 2016 Data collected from U.S. residents | 3000 | To investigate the degree to which self-reported tolerance for stigmatised groups is overstated, estimate rates of political tolerance for various groups, and compare indirect estimates to direct self-reported tolerance. The study also utilises Bayesian hierarchical modelling for data analysis. | The tolerance scale measured in the study is self-reported willingness to vote for candidates from different stigmatised social groups, as well as indirectly measured tolerance using the unmatched count technique (UCT). |

| 4 | Development of a Scale to Measure Cross-Cultural Sensitivity in the Canadian Context | Pruegger et al., 1993 [31] | Observational study. | Canada | Undergraduate psychology students and geologists working in the International Geology Department of a large Calgary oil firm 55 undergraduate psychology students + 10 geologists + 49 female undergraduate psychology students + 22 male undergraduate psychology students. | 136 | To develop a measure of cross-cultural sensitivity in the Canadian context with acceptable levels of internal consistency and content validity, and to explore its validity through further research. | The tolerance scale measured in the study is the Cross-Cultural Sensitivity Scale, which was based on the response values for the “disagree-keyed” items, with higher scores indicating greater cross-cultural sensitivity. |

| 5 | Issues in Cross-Cultural Counseling—An Examination of the Meaning and Dimensions of Tolerance | Sutter and McCaul, 1993 [32] | Quantitative study. | Sweden | Professionals working with immigrants and refugees in Southern Sweden 65% social workers, 20% counsellors, 10% language teachers, 5% medical personnel. 64% female, 36% male Age ranged from 25 to 64, with 70% between 30 and 50. Majority from rural areas or small towns Relatively well educated with a mean of 3.6 years of education beyond high school. | 123 | Develop a measure of ethnic tolerance through fieldwork Assess the reliability and construct validity of the tolerance measure based on two models of ethnic tolerance. Investigate the relationship between factors like age, gender, and exposure to different cultures with scores on the tolerance measure. | The tolerance scale measured in the study is a 24-item ethnic tolerance measure that was found to be a unidimensional construct with a reliability coefficient of 0.80 and showed some evidence of construct validity through correlational analysis. |

| 6 | When the Rubber Meets the Road: Effects of Urban and Regional Residence on Principle and Implementation Measures of Racial Tolerance | Carter et al., 2005 [33] | Observational study. | United States | Individuals aged 18 years and older in the United States. Consideration of differences in racial tolerance based on urban and regional residence. Assessment of the influence of urban residency on attitudes, independent of socioeconomic status. | 10,123 | To revisit racial tolerance differences based on urban vs. non-urban residence, non-Southern vs. Southern residence, and changes over time, while incorporating both principle and implementation questions. | The tolerance scale measured in the study includes both principle questions focusing on endorsing broad principles of equal treatment regardless of race and implementation questions putting principles of equal treatment into effect by ending discrimination and enforced segregation. The study uses composite measures of tolerance based on responses to questions related to interracial marriage, voting for an African American president, neighbourhood segregation, government intervention in busing, and discriminatory practices of homeowners. |

| 7 | Race and Religion in the Bible Belt: Parental Attitudes Toward Interfaith Relationships | Sahl and Baston, 2011 [34] | Observational study. | United States | Majority white population in the Bible Belt region. Significant presence of Baptist religious affiliation in the survey area. Religious importance in the everyday lives of respondents. 78% white and 22% black respondents in the final sample. Historically racially segregated region in the South. African Americans more likely than whites to engage in religious activities. | 412 | To include examining racial and religious differences in parental attitudes toward interfaith relationships, determining differences in attitudes based on religion and race, exploring the increase in opposition as relationships become more intimate, and investigating variations in the association between religion and attitudes across racial groups. | The tolerance scale measured in the study ranges from 0 to 12, with different scores for race, religious affiliation, and religious importance. Whites had a mean tolerance score of 6.97, while black respondents had a score of 8.11. Baptists were less tolerant with a score of 6.96 compared to non-Baptists with a score of 7.72. Religious importance did not show significance in the tolerance scale analysis. |

| 8 | Between Homohysteria and Inclusivity: Tolerance towards Sexual Diversity in Sport | Piedra et al., 2017 [35] | The study design is a correlational study using a Likert scale self-report questionnaire, with data collected through different methods in Spain and the UK. The study did not involve randomisation, blinding, control groups, or placebos. | Spain and UK | The study population consisted of 879 men and women aged 16–78 from Spain and the United Kingdom who were actively participating in or following sports. 67.7% of the participants were involved in sports within a federation, while 32.2% were not. 75.3% of the participants had higher education backgrounds. The majority of participants (88.9%) identified as heterosexual, with smaller percentages identifying as lesbians (3.2%), gays (2.3%), bisexuals (2.5%), and others (0.6%) | 879 | To describe the level of tolerance towards sexual diversity in sport in Spain and the UK, measure and validate sportspeople’s attitudes in two dimensions (non-rejection and acceptance), identify metacognitive profiles based on tolerance dimensions, and contrast the samples from both countries to theorise the main differences. | The tolerance scale measured in the study includes two dimensions: non-rejection and acceptance of sexual diversity in sport, measured using a new instrument with high reliability, the Attitudes towards Lesbians and Gays (ATLG) scale, and the Attitude Scale towards Sexual Diversity in Sport. |

| 9 | Disapproved, but Tolerated: The Role of Respect in Outgroup Tolerance | Simon et al., 2019 [36] | Observational study | United States | Participants who self-identified as supporters of the Tea Party movement in the United States, with a mean age of 55 years, 60% male, 47% with a college or university degree, and a total household income ranging from up to USD 5000 to more than USD 250,000, with a mean of USD 68,026. | Total: 485 Tea Party supporters: 422 Undergraduate students in the experiment: 63 | To test the hypothesis that respect for disapproved outgroups increases tolerance toward them, investigate the influence of respect for homosexuals and Muslims on Tea Party supporters’ tolerance, and conduct a larger longitudinal survey and an experiment with members of a majority as research participants and minorities as target groups. | The tolerance scale measured in the study includes individual tolerance towards specific groups (homosexuals and Muslims) as well as tolerance towards a specific student group in a university setting, measured using 5-point and 10-item scales, respectively. |

| 10 | A New Approach to the Study of Tolerance: Conceptualizing and Measuring Acceptance, Respect, and Appreciation of Difference | Hjerm et al., 2020 [37] | The study design is a cross-sectional observational study involving national and cross-national surveys to develop and validate measures of tolerance. | Sweden, Australia, Denmark, Great Britain, and the United States | The study includes a national sample from Sweden and a cross-national sample from Australia, Denmark, Great Britain, Sweden, and the United States. The Swedish sample has a slightly lower percentage of individuals with three or more years of tertiary education compared to the general population in 2016. The sample includes 11.1% foreign-born individuals, which is lower than the foreign-born percentage in the total population in 2016. The study does not provide specific demographic breakdowns by age, sex, race, ethnicity, or other characteristics. | 6300 | To advance research that distinguishes analytically between tolerance and prejudice, conceptualise tolerance as a value orientation towards difference, improve the measurement of tolerance, and assess the relationship between tolerance and prejudice. | The tolerance scales measured in the study are tolerance as respect for diversity and tolerance as appreciation for diversity |

| 11 | Measuring Tolerant Behavior | Liberati et al., 2021 [38] | Observational, cross-sectional study | Italy | University students at the University of Milan-Bicocca. | 3389 | To develop a multidimensional index for Likert-scale data to measure tolerant attitudes towards different social domains, determine the contribution of each dimension to overall tolerance, and apply this measure in a case study with Italian university students. | The tolerance scale measured in the study is a multidimensional index specifically designed for Likert-scale data, reflecting the intensity of tolerant attitudes towards different social domains and combining these dimensions using a weighted scheme. The study also discusses the potential generalisation of the index for non-Likert-scale data. |

References

- Appardurai, A. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hagendoorn, L. Intergroup biases in multiple group systems: The perception of ethnic hierarchies. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 6, 199–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J.; Pratto, F. Social dominance theory: A new synthesis. In Social Dominance; Sidanius, J., Pratto, F., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks Cole: Stamford, CT, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- van Doorn, M. The nature of tolerance and the social circumstances in which it emerges. Curr. Sociol. 2014, 62, 905–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.L. Enigmas of intolerance: Fifty years after Stouffer’s communism, conformity, and civil liberties. Perspect. Politics 2006, 4, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.L.; Piereson, J.; Marcus, G.E. Political Tolerance and American Democracy; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Walzer, M. On Toleration; Yale University Press: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, W.P. Tolerance and Education: Learning to Live with Diversity and Difference; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fukazawa, K.; Takayama, H. Shinko to Tasha (Faith and Others); University of Tokyo Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mutz, D.C. Cross-cutting Social Networks: Testing Democratic Theory in Practice. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2002, 96, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouffer, S.A. Communism, Conformity and Civil Liberties: A Cross-Section of the Nation Speaks Its Mind; Peter Smith: Gloucester, MA, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- The Philosophical Dictionary, Voltaire. Hanover Historical Texts Project by Hanover College Department of History. Selected and Translated by H.I. Woolf; Knopf: New York, NY, USA. 1924. Available online: https://history.hanover.edu/texts/voltaire/voltoler.html (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- UNESCO. Declaration of Principles on Tolerance. 1995. Available online: https://www.oas.org/dil/1995%20Declaration%20of%20Principles%20on%20Tolerance%20UNESCO.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Ferrar, J.W. The dimensions of tolerance. Pac. Sociol. Rev. 1976, 19, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Witenberg, R.; Sanson, A. The socialization of tolerance. In Understanding Prejudice, Racism and Social Conflict; Augoustinos, M., Reynolds, K.J., Eds.; Sage: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India, 2001; pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.L. Parsimony in the study of tolerance and intolerance. Political Behav. 2005, 27, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyd, D. Toleration: An Elusive Virtue; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Oberdiek, H. Tolerance: Between Forbearance and Acceptance; Rowman and Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon, T.M. Philosophy; University of Cambridge Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Galston, W.A. Review of Autonomy, Accommodation, and Tolerance: Three Encounters with Diversity, by Emily R. Gill, Sanford Levinson, and T. M. Scanlon. Political Theory 2005, 33, 582–588. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30038442 (accessed on 2 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Verkuyten, M. Tolerance of Muslim beliefs and practices: Age related differences and context effects. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2007, 31, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, B. Anything but heavy metal symbolic exclusion and musical dislikes. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1996, 61, 884–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A. Understanding audience segmentation: From elite and mass to omnivore and univore. Poetics 1992, 21, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. Cities and the Creative Class; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, J.L.; Transue, J.E. The psychological underpinnings of democracy: A selective review of research on political tolerance, interpersonal trust, and political tolerance, interpersonal trust, and social capital. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1999, 50, 625–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.L.; Piereson, J.; Marcus, G.E. An Alternative Conceptualization of Political Tolerance: Illusory Increases 1950s–1970s. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1979, 73, 781–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.L. The sources of political tolerance: A multivariate analysis. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1981, 75, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Iannuzzi, J.L.; Najle, M.B.; Gervais, W.M. The Illusion of Political Tolerance: Social Desirability and Self-Reported Voting Preferences. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2019, 10, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruegger, V.J.; Rogers, T.B. Development of a scale to measure cross-cultural sensitivity in the Canadian context. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 1993, 25, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, J.; McCaul, E. Issues in Cross-Cultural Counseling—An Examination of the Meaning and Dimensions of Tolerance. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 1993, 16, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.; Steelman, L.; Mulkey, L.; Borch, C. When the rubber meets the road: Effects of urban and regional residence on principle and implementation measures of racial tolerance. Soc. Sci. Res. 2005, 34, 408–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahl, A.H.; Batson, C.D. Race and Religion in the Bible Belt: Parental Attitudes Toward Interfaith Relationships. Sociol. Spectr. 2011, 31, 444–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedra, J.; García-pérez, R.; Channon, A.G. Between Homohysteria and Inclusivity: Tolerance Towards Sexual Diversity in Sport. Sex. Cult. 2017, 21, 1018–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, B.; Eschert, S.; Schaefer, C.D.; Reininger, K.M.; Zitzmann, S.; Smith, H.J. Disapproved, but Tolerated: The Role of Respect in Outgroup Tolerance. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bulleti 2019, 45, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjerm, M.; Eger, M.A.; Bohman, A.; Connolly, F. A New Approach to the Study of Tolerance: Conceptualizing and Measuring Acceptance, Respect, and Appreciation of Difference. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 147, 897–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, C.; Longaretti, R.; Michelangeli, A. Measuring Tolerant Behavior. J. Econ. Stat. 2021, 241, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Search String | Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Web of Science | “tolerance scale*” OR “tolerance measure*” OR “measure* of tolerance” OR “scale* of tolerance” | Behavioural Sciences, Psychology, Paediatrics, Sociology, Social Issues, Anthropology, Family Studies, Ethnic Studies, Cultural Studies, Religion, Social Work |

| Science Direct | “tolerance scale” OR “tolerance measure” OR “scale of tolerance” OR “tolerance scales” OR “tolerance measures” OR “scales of tolerance” OR “tolerance measurement” OR “measurement of tolerance” | Psychology, Social Sciences |

| ProQuest | “tolerance scale*” OR “tolerance measure*” OR “measure* of tolerance” OR “scale* of tolerance” | Psychology, Political Science, Studies, Sociology, Religion, Social Psychology, Education, Tolerance, Politics, Personality, Mental Health, Research, Humans, Behaviour, Questionnaires, Attitudes, Emotions, Hypotheses, Male, Female, Minority and Ethnic Groups, Anxiety, Experiments, Families and Family Life, Students, College Students, Perceptions, Quantitative Psychology, Democracy, Population, Stress, Adult |

| Number | Title | Authors, Year | Definition of Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | An Alternative Conceptualization of Political Tolerance: Illusory Increases 1950s–1970s | Sullivan et al., 1979 [28] | The definition of tolerance refers to the willingness to permit the expression of those ideas or interests that one opposes. |

| 2 | The Sources of Political Tolerance: A Multivariate Analysis | Sullivan and John L, 1981 [29] | The “tolerance definition” refers to the measurement of political tolerance using a content-controlled measure, which allows respondents to specify the groups they most strongly oppose without contaminating the tolerance/intolerance dimension with their political beliefs. The paper emphasises the importance of using a content-controlled measure to avoid bias in assessing political tolerance. |

| 3 | The Illusion of Political Tolerance: Social Desirability and Self-Reported Voting Preferences | Brown-Iannuzzi et al., 2019 [30] | The definition of tolerance is that a tolerant person accepts the presence and participation of all kinds of people in society, regardless of personal thoughts or feelings about them. |

| 4 | Development of a Scale to Measure Cross-Cultural Sensitivity in the Canadian Context | Pruegger et al., 1993 [31] | Tolerance is defined as the willingness to permit the expression of ideas or interests that one opposes, implying a wide acceptance of challenging viewpoints in a political context. It arises when there is opposition or disagreement, and it is considered valuable for maintaining a stable democratic regime. |

| 5 | Issues in Cross-Cultural Counseling—An Examination of the Meaning and Dimensions of Tolerance | Sutter and McCaul, 1993 [32] | The tolerance definition is the presence of mutual respect, acceptance, and exchange of cultural beliefs between counsellor and client, and the absence of prejudicial attitudes and beliefs that interfere with accepting the reality of the individual. It also includes the concepts of ethnocentrism, stereotyping, and the influence of social, economic, and cultural threats on prejudicial attitudes. |

| 6 | When the Rubber Meets the Road: Effects of Urban and Regional Residence on Principle and Implementation Measures of Racial Tolerance | Carter et al., 2005 [33] | The tolerance definition is something that can be seen as merely putting up with people that are different. Rather than just passive acceptance of others, the paper envision tolerance from a more activist perspective, including favourable views and willingness to help others. |

| 7 | Race and Religion in the Bible Belt: Parental Attitudes Toward Interfaith Relationships | Sahl and Baston, 2011 [34] | The “tolerance definition” refers to the measurement of attitudes towards interfaith unions at different levels of intimacy, such as friendship, dating, and marriage, using a tolerance scale. This scale helps to explore racial and religious gaps in opposition towards interfaith relationships. |

| 8 | Between Homohysteria and Inclusivity: Tolerance towards Sexual Diversity in Sport | Piedra et al., 2017 [35] | Tolerance is defined as the acceptance regarding the participation of LGBT people in sport. |

| 9 | Disapproved, but Tolerated: The Role of Respect in Outgroup Tolerance | Simon et al., 2019 [36] | The tolerance definition refers to the valuation and acceptance of different cultures, particularly among dominant group members in Canada. It is a key aspect of cross-cultural sensitivity being measured in the study. |

| 10 | A New Approach to the Study of Tolerance: Conceptualizing and Measuring Acceptance, Respect, and Appreciation of Difference | Hjerm et al., 2020 [37] | The tolerance definition is a value orientation towards difference. It measures the response to the existence of diversity. It focuses on subjective reactions to difference; thus, this conceptualisation does not require dislike of or identification of potentially objectionable groups, ideas, or behaviour. |

| 11 | Measuring Tolerant Behavior | Liberati et al., 2021 [38] | The tolerance definition refers to a multidimensional view of tolerance, with attitudes along each dimension of tolerance contributing to overall tolerance. |

| Number | Title | Authors, Year | Focus of Questionnaire | Number of Questions | Response Options |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | An Alternative Conceptualization of Political Tolerance: Illusory Increases 1950s–1970s | Sullivan et al., 1979 [28] | Political tolerance | Total: 12 questions | 1 to 5 Likert scale 1 = Strongly disagree 5 = Strongly agree |

| 2 | The Sources of Political Tolerance: A Multivariate Analysis | Sullivan and John L, 1981 [29] | Political tolerance | Total: 6 questions | 1 to 5 Likert scale 1 = Strongly disagree 5 = Strongly agree |

| 3 | The Illusion of Political Tolerance: Social Desirability and Self-Reported Voting Preferences | Brown-Iannuzzi et al., 2019 [30] | Political tolerance | Total: 8 questions | 6 Candidate options Yes/No |

| 4 | Development of a Scale to Measure Cross-Cultural Sensitivity in the Canadian Context | Pruegger et al., 1993 [31] | Cultural tolerance | Total: 24 questions Agree-keyed: 13 Disagree-keyed: 11 | 1 to 6 Likert scale 1 = Strongly disagree 6 = Strongly agree |

| 5 | Issues in Cross-Cultural Counseling—An Examination of the Meaning and Dimensions of Tolerance | Sutter and McCaul, 1993 [32] | Ethnic and racial tolerance | Total: 24 questions Cultural subscale: 10 Economic subscale: 4 Social subscale: 4 Others: 6 | 1 to 5 Likert scale 1 = Yes, absolutely 5 = No, absolutely not |

| 6 | When the Rubber Meets the Road: Effects of Urban and Regional Residence on Principle and Implementation Measures of Racial Tolerance | Carter et al., 2005 [33] | Ethnic and racial tolerance | Total: 5 questions | 1 to 4 Likert scale 1 = Strongly agree 4 = strongly disagree Yes/No |

| 7 | Race and Religion in the Bible Belt: Parental Attitudes Toward Interfaith Relationships | Sahl and Baston, 2011 [34] | Racial and religious tolerance | Total: 3 questions | 0 to 4 Likert scale 0 = Yes, absolutely 4 = No, absolutely |

| 8 | Between Homohysteria and Inclusivity: Tolerance towards Sexual Diversity in Sport | Piedra et al., 2017 [35] | Gender and sexual tolerance | Total: 32 questions Acceptance questions: 20 Non-rejection questions: 12 | 1 to 5 Likert scale 1 = Totally agree 5 = Totally disagree |

| 9 | Disapproved, but Tolerated: The Role of Respect in Outgroup Tolerance | Simon et al., 2019 [36] | Social tolerance | Total: 6 questions | −3 to +3 Likert scale 0 to 5 acceptance scale |

| 10 | A New Approach to the Study of Tolerance: Conceptualizing and Measuring Acceptance, Respect, and Appreciation of Difference | Hjerm et al., 2020 [37] | Social tolerance | Total: 8 questions | 1 to 5 Likert scale 1 = Completely disagree 5 = Completely agree |

| 11 | Measuring Tolerant Behavior | Liberati et al., 2021 [38] | Social tolerance | Total: 13 questions Interreligious dialog: 3 Women/religion relationship: 3 Death/religion relationship: 2 Multicultural society: 3 Homosexuality: 2 | 1 to 5 Likert scale 1 = Strongly disagree 5 = Strongly agree |

| Number | Authors, Year | Validity and Reliability Tests |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sullivan et al., 1979 [28] | The measurement scale has been tested and shown to have validity, as the groups selected as least liked by respondents aligned with their self-reported political ideology in an expected way. |

| 2 | Sullivan and John L, 1981 [29] | The measurement scale has been tested and found to be reliable and appropriate for measuring political tolerance, addressing the content bias of previous measures. |

| 3 | Brown-Iannuzzi et al., 2019 [30] | The measurement scale (the unmatched count technique) has been tested and used in prior research to measure sensitive or socially undesirable attitudes and behaviours, suggesting it is a validated approach for overcoming social desirability concerns. |

| 4 | Pruegger et al., 1993 [31] | The measurement scale has been tested and demonstrates reasonable levels of content validity and impressive internal consistency, but further testing is needed to fully evaluate the scale’s psychometric properties. |

| 5 | Sutter and McCaul, 1993 [32] | The measurement scale has been tested through a pilot study with faculty and graduate students and revised based on their feedback. |

| 6 | Carter et al., 2005 [33] | The measurement scale (the principle-based questions index) has been tested and found to be a similar and strong measure of racial tolerance and may even be more parsimonious and effective than the previous six-question index used in prior research. |

| 7 | Sahl and Baston, 2011 [34] | The measurement scale has been tested and found to have strong reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.880. |

| 8 | Piedra et al., 2017 [35] | The measurement scale has been tested and found to have high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.95) and construct validity through factor analysis, demonstrating it is a reliable and valid measure of tolerance towards sexual diversity in sport. |

| 9 | Simon et al., 2019 [36] | The measurement scales used in the study had been tested and used in prior research, as indicated by the paper’s statement that the measures were “adapted from earlier work” and “the same measures were used at both time points”. The paper also reports on the reliability of some of the measures, such as Cronbach’s alpha for the tolerance measure in Study 2. |

| 10 | Hjerm et al., 2020 [37] | The measurement scale has been tested and validated through confirmatory factor analysis in a single country (Sweden) and across multiple countries (Australia, Denmark, Sweden, the UK, and the US), showing good model fit and metric invariance across countries. |

| 11 | Liberati et al., 2021 [38] | The measurement scale has been tested and found to have high internal consistency, as indicated by the relatively high Cronbach’s alpha values for the two submatrices of survey items. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Costantini, H.; Al Mujahid, M.A.A.; Hosaka, K.; Ono, T.; Nihei, M. Instruments to Assess People’s Attitude and Behaviours towards Tolerance: A Systematic Review of Literature. Societies 2024, 14, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14070121

Costantini H, Al Mujahid MAA, Hosaka K, Ono T, Nihei M. Instruments to Assess People’s Attitude and Behaviours towards Tolerance: A Systematic Review of Literature. Societies. 2024; 14(7):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14070121

Chicago/Turabian StyleCostantini, Hiroko, Muhammad Abdul Aziz Al Mujahid, Kengo Hosaka, Takazumi Ono, and Misato Nihei. 2024. "Instruments to Assess People’s Attitude and Behaviours towards Tolerance: A Systematic Review of Literature" Societies 14, no. 7: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14070121

APA StyleCostantini, H., Al Mujahid, M. A. A., Hosaka, K., Ono, T., & Nihei, M. (2024). Instruments to Assess People’s Attitude and Behaviours towards Tolerance: A Systematic Review of Literature. Societies, 14(7), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14070121