Transitioning from Communicative Competence to Multimodal and Intercultural Competencies: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Rationale of the Study

3. Methods

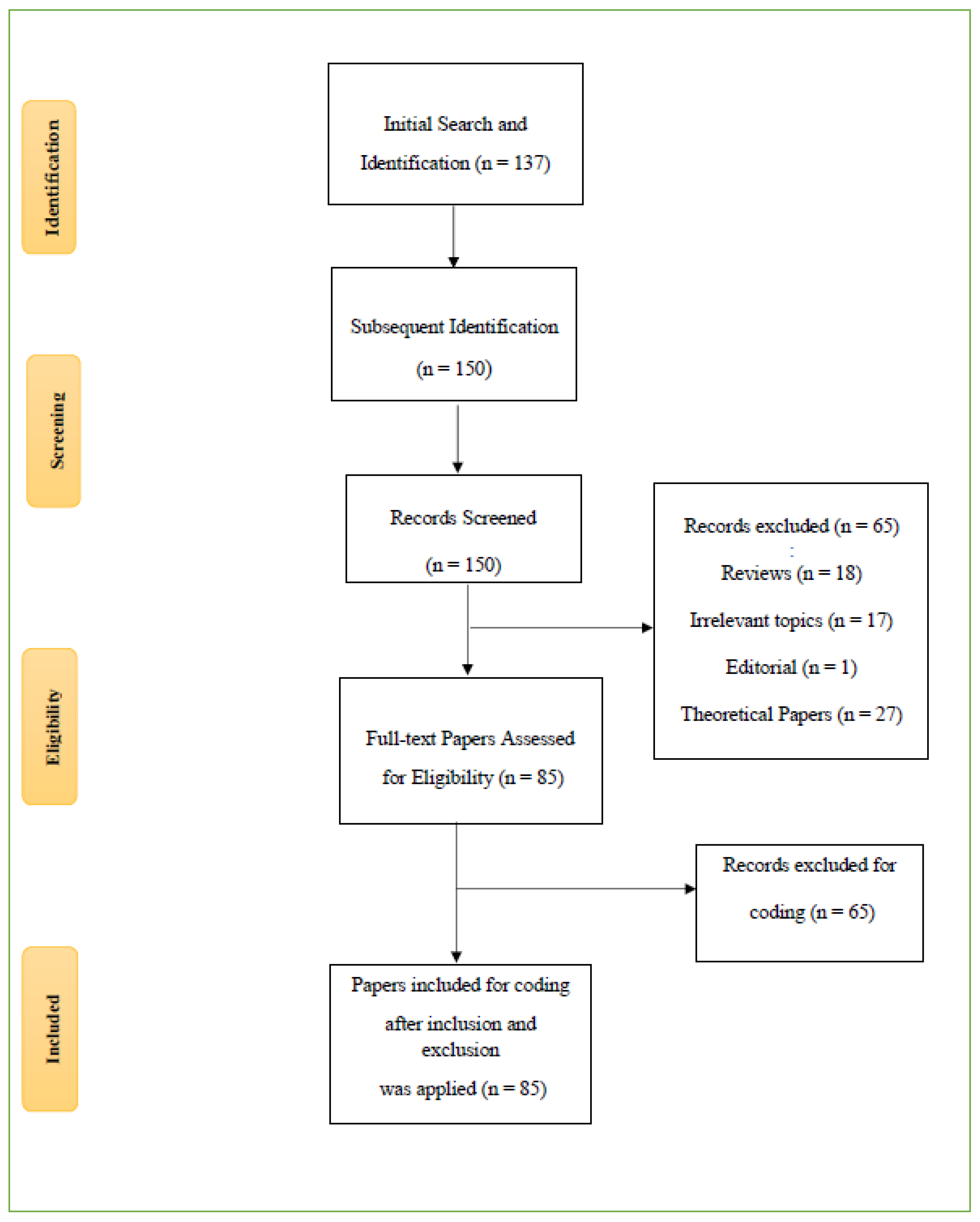

3.1. Procedures

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.3. Coding Scheme

3.4. Coding Reliability

4. Results

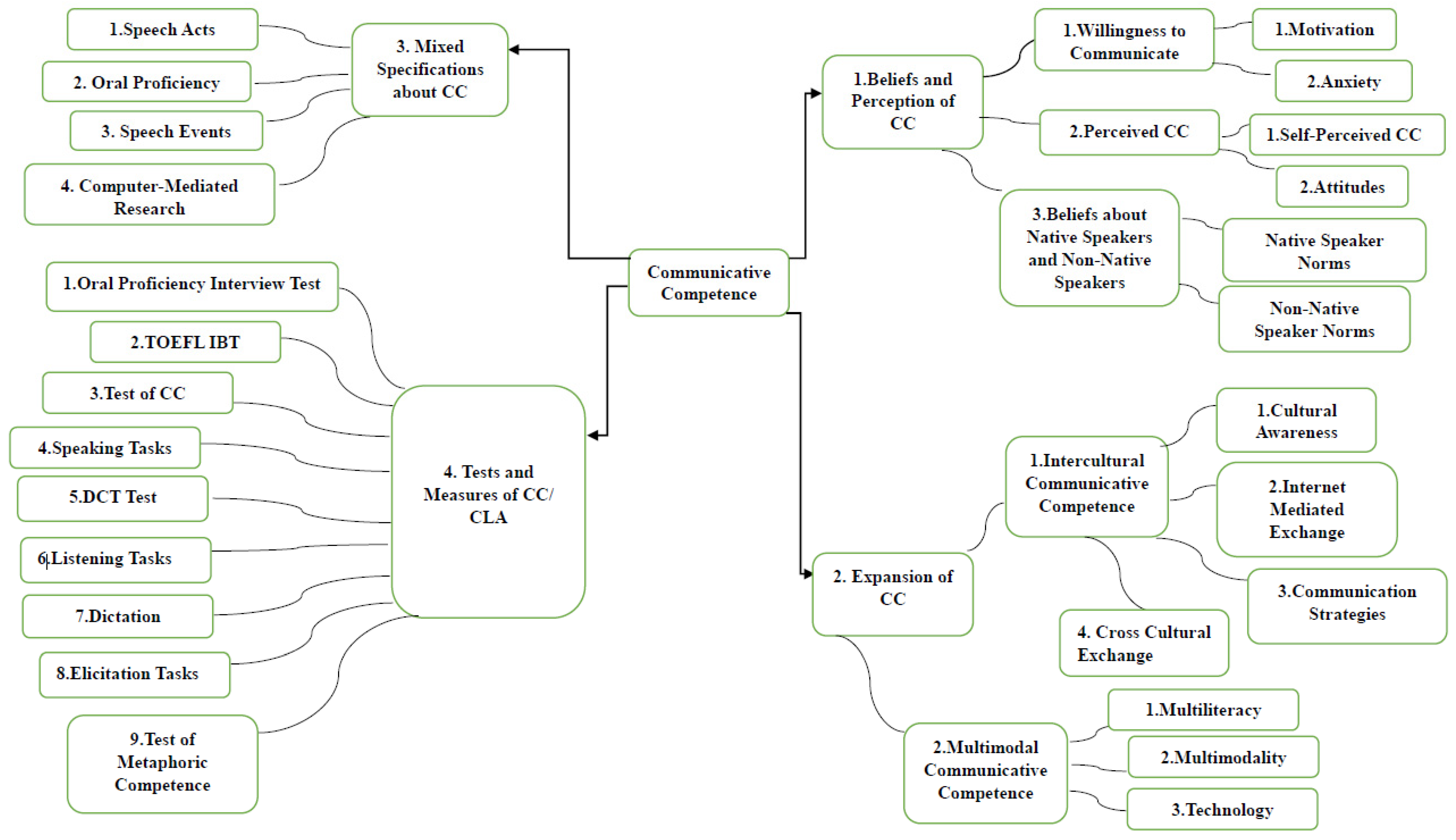

4.1. Research Question 1

4.2. Beliefs and Perceptions about CC

4.2.1. Willingness to Communicate

4.2.2. Perceived Communicative Competence

4.2.3. Beliefs about Native Speakers and Non-Native Speakers

4.3. Expansion of Communicative Competence

4.3.1. Intercultural Communicative Competence

4.3.2. Multimodal Communicative Competence

4.3.3. Mixed Specifications of CC

4.4. Components of Communicative Competence

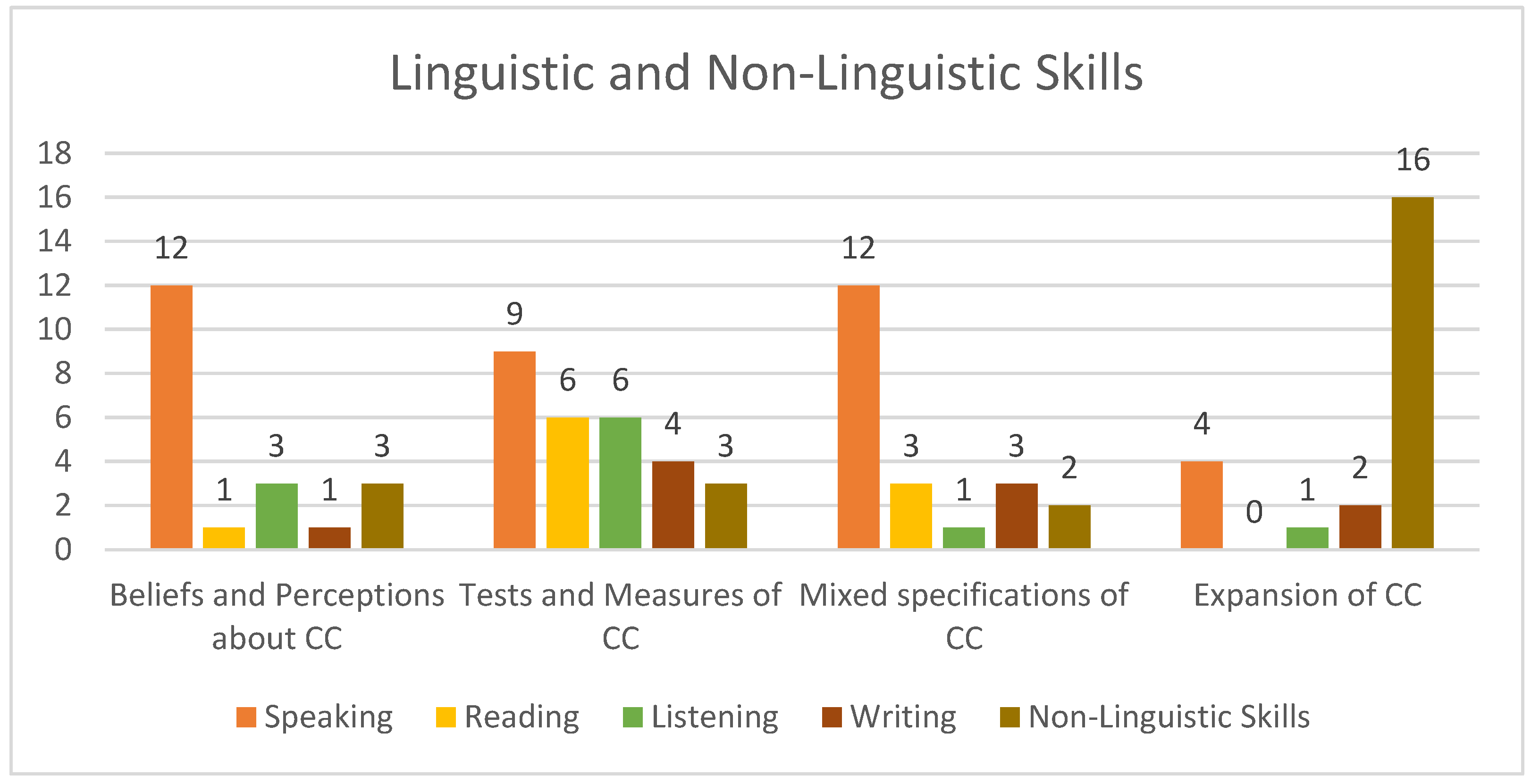

4.5. Linguistic and Non-Linguistic Skills

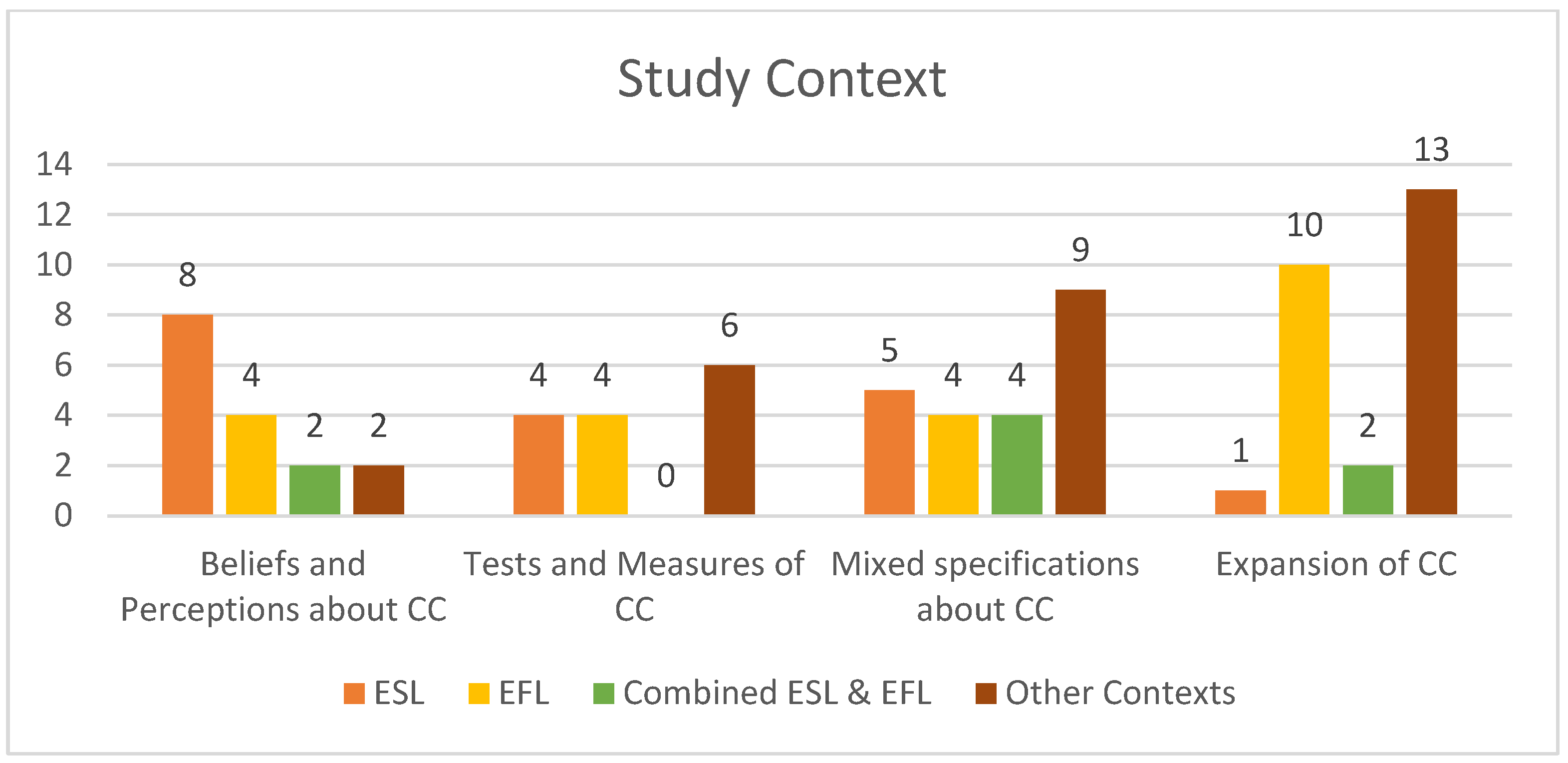

4.6. Study Context

4.7. Research Question 2

| Test Types of CC/ CLA | Instrumentation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| OPI | Discrete point test | [73] |

| Speaking Test of TOEFL | MCQ items Speaking tasks (spoken stimulus); Reading passage | [74] |

| Japanese OPI | Structured face to face interview | [76] |

| PACT CELT Parallel versions of CC test | MCQ test (oral stimulus) Written MCQ test Responses elicited by pictures Behaviour questionnaires Global rating scales | [77] |

| Listening comprehension test Oral production test Assessment of CC | MCQ (Standardized Test) Visual stimulus Rating scale | [78] |

| Test of CLA | 15 min oral interview | [79] |

| Assessment tasks | Individual presentation Group oral discussion | [80] |

| Listening test Pronunciation test C-test Grammar test Vocabulary test Discourse completion test oral interview Oral interview Student role-play | IELTS practice test referring to syllable stress, weak forms, individual sound recognition similar to a traditional cloze test MCQ items Schmitt’s vocabulary levels test (version 1) use eight different request speech acts with audio visual prompts Interview, a version of the IELTS speaking test A chance meeting with a friend in the street | [81] |

| Communicative competence | Dictation as a measure of CC | [82] |

| Written communicative competence | Rating Scale described as Pertinence, Clarity, Structural Accuracy | [83] |

| Sociolinguistic test | MCQ test IELTS as pre-test | [84] |

| ACTFL OPI ITA test | Rating score of proficiency 10 min mock teaching test, Rating Scale | [85] |

| Written discourse competence task | Description of 12 request situations | [86] |

| Knowledge Test Proficiency in oral English communication Satisfaction and usability questionnaire | MCQ Auditory discrimination and verbal production Questionnaire using 5-point Likert scale | [87] |

5. Discussion

5.1. Construct Definition in CC Research

5.2. Construct Operationalization in CC Research

5.2.1. Features of Operationalization in CC Research

5.2.2. Tests and Methods of Operationalization in CC Research

6. Summary of Findings

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bachman, L. Fundamental Considerations in Language Testing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman, L.F.; Palmer, A. The Construct Validation of Some Components of Communicative Proficiency. TESOL Q. 1982, 16, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, M. From Communicative Competence to Communicative Language Pedagogy. In Language and Communication; Richards, J., Schmidt, R., Eds.; Longman: London, UK, 1983; pp. 2–27. [Google Scholar]

- Canale, M.; Swain, M. Theoretical Bases of Communicative Approaches to Second Language Teaching and Testing. Appl. Linguist. 1980, 1, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celce-Murcia, M.; Dornyei, Z.; Thurrell, S. Communicative Competence: Pedagogically Motivated Model with Content Specifications. Issues Appl. Linguist. 1995, 6, 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwit, M.; Solon, M. (Eds.) Communicative Competence in a Second Language: Theory, Method, and Applications; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savignon, S.J. Communicative Competence: An Experiment in Foreign Language Teaching; Centre for Curriculum Development: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R. Interaction, Acculturation, and the Acquisition of Communicative Competence: A Case Study of an Adult. In Sociolinguistics and Language Acquisition; Wolfson, N., Judd, E., Eds.; Newbury House: Rowley, MA, USA, 1983; pp. 137–174. [Google Scholar]

- Savignon, S.J. Communicative Competence: Theory and Classroom Practice; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hymes, D.H. Models of the Interaction of Language and Social Setting. J. Soc. Issues 1967, XXIII, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymes, D.H. On Communicative Competence. In Sociolinguistics; Pride, J.B., Holmes, J., Eds.; Penguin Books: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1972; pp. 269–293. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman, L.F.; Palmer, A. Language Assessment in Practice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, C.; Scarino, A. Reconceptualizing the Nature of Goals and Outcomes in Language/s Education. Mod. Lang. J. 2016, 100, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, M. Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kramsch, C. The Symbolic Dimensions of the Intercultural. Lang. Teach. 2011, 44, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramsch, C. Teaching Foreign Languages in an Era of Globalization: Introduction. Mod. Lang. J. 2014, 98, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, D.M. The Role of Technology in SLA Research. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2016, 20, 98–115. [Google Scholar]

- Hult, F.M. Covert Bilingualism and Symbolic Competence: Analytical Reflections on Negotiating insider/outsider Positionality in Swedish Speech Situations. Appl. Linguist. 2014, 35, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royce, T. Multimodality in the TESOL Classroom: Exploring Visual-Verbal Synergy. TESOL Q. 2002, 36, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H.; Hedges, L.V.; Valentine, J.C. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Aryadoust, V.; Luo, L. The Typology of Second Language Listening Constructs: A Systematic Review. Lang. Test. 2023, 40, 375–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avgousti, M.I. Intercultural Communicative Competence and Online Exchanges: A Systematic Review. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2018, 31, 819–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phakiti, A. Construct Validation of Bachman and Palmer’s (1996) Strategic Competence Model Over Time in EFL Reading Tests. Lang. Test. 2008, 25, 237–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavarro, D.; Ismael, R.; Puay, T. To What Extent is Inclusion in the Web of Science an Indicator of Journal ‘Quality’? Res. Eval. 2018, 27, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riazi, M.; Shi, L.; Haggerty, J. Analysis of the Empirical Research in the Journal of Second Language Writing at its 25th Year (1992–2016). J. Second Lang. Writ. 2018, 41, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phakiti, A.; De Costa, P.; Plonsky, L.; Starfield, S. Applied linguistics research: Current issues, methods, and trends. In The Palgrave Handbook of Applied Linguistics Research Methodology; Phakiti, A., De Costa, P., Plonsky, L., Starfield, S., Eds.; Palgrave-MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Coccetta, F. Developing University Students’ Multimodal Communicative Competence: Field Research into Multimodal Text Studies in English. System 2018, 77, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royce, T. Multimodal Communicative Competence in Second Language Contexts. In New Directions in the Analysis of Multimodal Discourse; Royce, T., Bowcher, W., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 361–390. [Google Scholar]

- Purpura, J. Assessing Communicative Language Ability: Models and their Components. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 2nd ed.; Shohamy, E., Hornberger, N.H., Eds.; Volume 7: Language Testing and Assessment; Springer Science & Business Media LLC: Cham, Switzerland, 2008; pp. 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, D. Assessing Languages for Specific Purposes; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hulstijn, J.H. Language Proficiency in Native and Non-Native Speakers: Theory and Research; John Benjamins Publication: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Plonsky, L.; Gass, S. Quantitative Research Methods, Study Quality, and Outcomes: The Case of Interaction Research. Lang. Learn. 2011, 61, 325–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.C.; MacIntyre, P.D. The Role of Gender and Immersion in Communication and Second Language Orientations. Lang. Learn. 2000, 50, 311–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.C. Motivation and Second Language Acquisition: Perspectives. J. CAAL 1996, 18, 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, A.; Gass, S. Second Language Research: Methodology and Design, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Celce-Murcia, M. Rethinking the Role of Communicative Competence in Language Teaching. In Intercultural Language Use and Language Learning; Soler, E.A., Jordà, M.P.S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, S.W.; Plonsky, L. A primer on Qualitative Research Synthesis in TESOL. TESOL Q. 2021, 55, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCroskey, J.C.; Richmond, V.P. Communication Apprehension and Shyness: Conceptual and Operational Distinctions. Cent. States Speech J. 1982, 33, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoon, J.K. The Unwillingness-to-Communicate Scale: Development and Validation. Commun. Monogr. 1976, 43, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCroskey, J.C.; Richmond, V.P. Willingness to Communicate. In Personal and Interpersonal Communication; McCroskey, J.C., Daly, J.A., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1987; pp. 129–156. [Google Scholar]

- Piechurska-Kuciel, E. Openness to Experience as a Predictor of L2 WTC. System 2018, 72, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders, H.; Wattana, S. Can I say something? the Effects of Digital Game Play on Willingness to Communicate. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2014, 18, 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, B.L.; Yu, M.H. Addressing the Language Needs of Administrative Staff in Taiwan’s Internationalised Higher Education: Call for an English as a Lingua Franca Curriculum to Increase Communicative Competence and Willingness to Communicate. Lang. Educ. 2018, 32, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subtirelu, N. A Language Ideological Perspective on Willingness to Communicate. System 2014, 42, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.M. Understanding Chinese Learners’ Willingness to Communicate in a New Zealand ESL Classroom: A Multiple Case Study Drawing on the Theory of Planned Behavior. System 2013, 41, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymes, D.H. Foundations in Sociolinguistics: An Ethnographic Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, A.; Apelgren, B.M. Young Learners and Multilingualism: A Study of Learner Attitudes before and after the Introduction of a Second Foreign Language to the Curriculum. System 2008, 36, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C. Using Wikis to Facilitate Interaction and Collaboration among EFL Learners: A Social Constructivist Approach to Language Teaching. System 2014, 42, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, B.N. Social Identity, Investment and Language Learning. TESOL Q. 1995, 29, 9–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, P.D.; Noels, K.A.; Clement, R. Biases in Self-Ratings of Second Language Proficiency: The Role of Language Anxiety. Lang. Learn. 1997, 47, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revesz, A. Task Complexity, Focus on L2 Constructions, and Individual Differences: A Classroom-Based Study. Mod. Lang. J. 2011, 95, 162–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Sanchez, S.; Lujan-Garcia, C. Ubiquitous Knowledge and Experiences to Foster EFL Learning Affordances. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2016, 29, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkovic, V. Online Informal Learning of English through Smartphones in Slovenia. System 2019, 80, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulstijn, J.H. An Individual-Differences Framework for Comparing Non-native with Native Speakers: Perspectives from BLC Theory. Lang. Learn. 2019, 69, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymes, D.H. On Communicative Competence; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, S.Y. Dealing with Communication Problems in the Instructional Interactions between International Teaching Assistants and American College Students. Lang. Educ. 2009, 23, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.A. Communicative Competence and Beliefs about Language among Graduate Teaching Assistants in French. Mod. Lang. J. 1993, 77, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, L.D. Primary Stress and Intelligibility: Research to Motivate the Teaching of Suprasegmentals. TESOL Q. 2004, 38, 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, O. Relative Salience of Suprasegmental Features on Judgments of L2 Comprehensibility and Accentedness. System 2010, 38, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relano, P.A.; Poveda, D. Native Speakerism and the Construction of CLIL Competence in Teaching Partnerships: Reshaping Participation Frameworks in the Bilingual Classroom. Lang. Educ. 2020, 34, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oranje, J.; Smith, L.F. Language Teacher Cognitions and Intercultural Language Teaching: The New Zealand Perspective. Lang. Teach. Res. 2018, 22, 310–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskoz, A.; Gimeno-Sanz, A. Engagement and Attitude in Telecollaboration: Topic and Cultural Background Effects. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2019, 23, 136–160. [Google Scholar]

- Uzum, B.; Akayoglu, S.; Yazan, B. Using Telecollaboration to Promote Intercultural Competence in Teacher Training Classrooms in Turkey and the USA. ReCALL 2020, 32, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zheng, X. Chinese University Students’ Attitude Towards Self and Others in Reflective Journals of Intercultural Encounter. System 2019, 84, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregi, K.; de Graaff, R.; van den Bergh, H.; Kriz, M. Native/Non-native Speaker Interactions through Video-Web Communication: A Clue for Enhancing Motivation? Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2012, 25, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.R.; Rose, D. Working with Discourse: Meaning Beyond the Clause; Continuum: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Birlik, S.; Kaur, J. BELF Expert Users: Making Understanding Visible in Internal BELF Meetings through the Use of Nonverbal Communication Strategies. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2020, 58, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.; Hauck, M.; Mueller-Hartmann, A. Promoting Learner Autonomy through Multiliteracy Skills Development in Cross-Institutional Exchanges. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2012, 16, 82–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, G. Literacy in the New Media Age; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman, L.F.; Palmer, A. Language Testing in Practice: Designing and Developing Useful Language Tests; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Halleck, G.B. The Oral Proficiency Interview—Discrete Point Test or a Measure of Communicative Language Ability. Foreign Lang. Ann. 1992, 25, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgeman, B.; Powers, D.; Stone, E.; Mollaun, P. TOEFL iBT Speaking Test Scores as Indicators of Oral Communicative Language Proficiency. Lang. Test. 2012, 29, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnsworth, T.L. An Investigation into the Validity of the TOEFL IBT Speaking Test for the International Teaching Assistant Certification. Lang. Assess. Q. 2013, 52, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, N. Self-Qualification in L2 Japanese: An Interface of Pragmatic, Grammatical, and Discourse Competences. Lang. Learn. 2007, 57, 337–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politzer, R.L.; McGroarty, M. An Exploratory Study of Learning Behaviors and their Relationship to Gains in Linguistic and Communicative Competence. TESOL Q. 1985, 19, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyers, J.R. The Effect of Authentic Video on Communicative Competence. Mod. Lang. J. 1999, 83, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlemore, J. Metaphoric Competence: A Language Learning Strength of Students with a Holistic Cognitive Style? TESOL Q. 2001, 35, 459–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Z.; Davison, C.; Hamp-Lyons, L. Topic Negotiation in Peer Group Oral Assessment Situations: A Conversation Analytic Approach. Appl. Linguist. 2009, 30, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, A. “I Prefer Not Text”: Developing Japanese learners’ Communicative Competence with Authentic Materials. Lang. Learn. 2011, 61, 786–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savignon, S.J. Dictation as a Measure of Communicative Competence in French as a 2nd Language. Lang. Learn. 1982, 32, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R.A. Testing Written Communicative Competence in French. Mod. Lang. J. 1984, 68, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.C. Teaching and Learning Sociolinguistic Skills in University EFL Classes in Taiwan. TESOL Q. 2008, 42, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halleck, G.B.; Moder, C.L. Testing Language and Teaching Skills of International Teaching Assistants: The Limits of Compensatory Strategies. TESOL Q. 1995, 29, 733–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Lai, C. The Effects of Deductive Instruction and Inductive Instruction on Learners’ Development of Pragmatic Competence in the Teaching of Chinese as a Second Language. System 2017, 70, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schaik, E.; Lynch, E.M.; Stoner, S.A.; Sikorski, L.D. Can a Web-Based Course Improve Communicative Competence of Foreign-born Nurses? Lang. Learn. Technol. 2014, 18, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.A. Towards Respecification of Communicative Competence: Condition of L2 Instructions or its Objective? Appl. Linguist. 2006, 27, 349–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, D.M. The Neglected Role of Intonation in Communicative Competence and Proficiency. Mod. Lang. J. 1988, 72, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savignon, S.J. Evaluation of Communicative Competence: The ACTFL Provisional Proficiency Guidelines. Mod. Lang. J. 1985, 69, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, G. Multimodality: Challenges to Thinking about Language. TESOL Q. 2000, 34, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A. Communicative Competence as Language Use. Appl. Linguist. 1989, 10, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulston, C.B. Linguistic and Communicative Competence. TESOL Q. 1974, 8, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, S.L. The Intercultural Turn and Language Learning in the Crucible of New Media. In Telecollaboration 2.0: Language and Intercultural Learning in the 21st Century; Guth, S., Helm, F., Eds.; Peter Lang: Berne, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 139–165. [Google Scholar]

- Kusumaningputri, R.; Widodo, H.P. Promoting Indonesian University Students’ Critical Intercultural Awareness in Tertiary EAL Classrooms: The Use of Digital Photograph-Mediated Intercultura199l tasks. System 2018, 72, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Coleman, J.A. A Survey of Internet-mediated Intercultural Foreign Language Education in China. ReCALL 2009, 21, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohinski, C.A.; Leventhal, Y. Rethinking the ICC Framework: Transformation and Telecollaboration. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2015, 48, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, E. Promoting EFL Learners’ Intercultural Communication Effectiveness: A Focus on Facebook. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2017, 30, 510–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Song, J. Developing Intercultural Competence through Study Abroad, Telecollaboration, and On-campus Language Study. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2019, 23, 178–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ryshina-Pankova, M. Discourse Moves and Intercultural Communicative Competence in Telecollaborative Chats. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2018, 22, 218–239. [Google Scholar]

- Tecedor, M.; Vasseur, R. Videoconferencing and the Development of Intercultural Competence: Insights from Students’ Self-Reflections. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2020, 53, 761–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolsky, B. Communicative Competence, Language Proficiency, and Beyond. Appl. Linguist. 1989, 10, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, L.; Macqueen, S.; Pill, J. Assessing Communicative Competence. In Communicative Competence in a Second Language: Theory, Method, and Applications; Kanwit, M., Solon, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2023; pp. 187–207. [Google Scholar]

- Rydell, M. Performance and Ideology in Speaking Tests for Adult Migrants. J. Socioling. 2015, 19, 535–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siskin, H.J.; Spinelli, E. Achieving Communicative Competence through Gambits and Routines. Foreign Lang. Ann. 1987, 20, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widdowson, H.G. Knowledge of Language and Ability for Use. Appl. Linguist. 1989, 10, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, G.; Van Leewen, T. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schuetze, U. Exchanging Second Language Messages Online: Developing an Intercultural Communicative Competence? Foreign Lang. Ann. 2008, 41, 660–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaffer, J. Terminology and its Discontents: Some Caveats about Communication Competence. Mod. Lang. J. 2006, 90, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, M.; Fleming, M. Language Learning in Intercultural Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Savignon, S.J.; Sysoyev, P.V. Cultures and Comparisons: Strategies for Learners. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2005, 38, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solon, M.; Kanwit, M. Looking Forward: Future Directions in the Study of Communicative Competence. In Communicative Competence in a Second Language: Theory, Method, and Applications; Kanwit, M., Solon, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2023; pp. 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryadoust, V.; Zakaria, A.; Jia, Y. Investigating the Affordances of OpenAI’s Large Language Model in Developing Listening Assessments. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. Sex-differences and Apologies—One Aspect of Communicative Competence. Appl. Linguist. 1989, 10, 194–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerantz, A.; Bell, N.D. Humor as Safe House in the Foreign Language Classroom. Mod. Lang. J. 2011, 95, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornberger, N.H. Trámites and Transportes—The Acquisition of 2nd Language Communicative Competence for One Speech Event in Puno, Peru. Appl. Linguist. 1989, 10, 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.; Lewkowicz, J. Language Communication and Communicative Competence: A View from Contemporary Classrooms. Lang. Educ. 2013, 27, 398–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.R. A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, C.; Chen, H.-I. Designing Talk in Social Networks: What Facebook Teaches about Conversation. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2017, 21, 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.Y.; Liu, Y. From Problem-Orientedness to Goal-Orientedness: Re-Conceptualizing Communication Strategies as Forms of Intra-Mental and Inter-Mental Mediation. System 2016, 61, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ferrada, D.; Del Pino, M. Communicative Competences Required in Initial Teacher Training for Primary School Teachers of Spanish Language in Contexts of Linguistic Diversity. Int. Multiling. Res. J. 2020, 14, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gablasova, D.; Brezina, V.; Mcenery, T.; Boyd, E. Epistemic Stance in Spoken L2 English: The effect of Task and Speaker Style. Appl. Linguist. 2017, 38, 613–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graus, J.; Coppen, P.A. The Interface between Student Teacher Grammar Cognitions and Learner-Oriented Cognitions. Mod. Lang. J. 2017, 101, 643–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, K. Computer-Assisted Learning of Communication (CALC): A Case Study of Japanese Learning in a 3D Virtual World. ReCALL 2018, 30, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morell, T. Interactive Lecture Discourse for University EFL Students. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2004, 23, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, P.B. Moi Tarzan, Vous Jane? A Study of Communicative Competence. Foreign Lang. Ann. 1975, 8, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, S.; Woll, N.; French, L.M.; Duchemin, M. Language Learners’ Metasociolinguistic Reflections: A Window into Developing Sociolinguistic Repertoires. System 2018, 76, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranney, S. Learning a New Script: An Exploration of Sociolinguistic Competence. Appl. Linguist. 1992, 13, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Moral-Perez, M.E.; Villalustre-Martinez, L.; Neira-Pineiro, D.M. Teachers’ Perception about the Contribution of Collaborative Creation of Digital Storytelling to the Communicative and Digital Competence in Primary Education Schoolchildren. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2019, 32, 342–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinder, R. Blending Technology and Face-to-Face: Advanced Students’ Choices. ReCALL 2016, 28, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.T.; Fiske, D.W. Convergent and Discriminant Validation by the Multitrait-Multimethod Matrix. Psychol. Bull. 1959, 56, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.H.; Bailey, A.L.; Sass, D.A.; Chang, Y.-H.S. An Investigation of the Validity of a Speaking Assessment for Adolescent English language learner. Lang. Test. 2020, 38, 401–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, A.; Knoch, U. Examining the Validity of an Analytic Rating Scale for Spanish Test for Academic Purposes Using the Argument-Based Approach to Validation. Assess. Writ. 2018, 35, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.; Liao, Y.-F.; Wagner, S. Authenticated Spoken Texts for L2 Listening Tests. Lang. Assess. Q. 2020, 18, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsmeier, S. Primary Teachers’ Knowledge When Initiating Intercultural Communicative Competence. TESOL Q. 2017, 51, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Hu, X.; Lai, C. Chinese as a Second Language Teachers’ Cognition in Teaching Intercultural Communicative Competence. System 2018, 78, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, S.A. Exploring Manifestations of Curiosity in Study Abroad as Part of Intercultural Communicative Competence. System 2014, 42, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, R. Understanding the “Other Side”: Intercultural Learning in a Spanish-English-E-Mail Exchange. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2003, 7, 118–144. [Google Scholar]

- Shiri, S. Intercultural Communicative Competence Development during and after Language Study Abroad: Insights from Arabic. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2015, 48, 541–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickler, U.; Emke, M. Literalia: Towards Developing Intercultural Maturity Online. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2011, 15, 147–168. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.J.; Yang, S.C. Fostering Foreign Language Learning through Technology-Enhanced Intercultural Projects. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2014, 18, 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Tudini, V. Negotiation and Intercultural Learning in Italian Native Speaker Chat Rooms. Mod. Lang. J. 2007, 91, 577–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Yang, S.C. Promoting Cross-Cultural Understanding and Language Use in Research-Oriented Internet-Mediated Intercultural Exchange. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2016, 29, 262–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitade, K. An Exchange Structure Analysis of the Development of Online Intercultural Activity. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2012, 25, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, K.; Hoffstaedter, P. Learner Agency and Non-Native Speaker Identity in Pedagogical Lingua Franca Conversations: Insights from Intercultural Telecollaboration in Foreign Language Education. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2017, 30, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| List of 20 Journals |

|---|

| Annual Review of Applied Linguistics |

| Applied Linguistics |

| Applied Linguistics Review |

| Assessing Writing |

| Computer Assisted Language Learning |

| English for Specific Purposes |

| Foreign Language Annals |

| International Multilingual Research Journal |

| Journal of Second Language Writing |

| Language and Education |

| Language Assessment Quarterly |

| Language Learning |

| Language Learning & Technology |

| Language Teaching Research |

| Language Testing |

| Modern Language Journal |

| RECALL |

| Studies in Second Language Acquisition |

| System |

| TESOL Quarterly |

| Inclusion Criteria: The Paper… | Exclusion Criteria: The Paper… |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Journal | No. of Papers | % |

|---|---|---|

| System | 12 | 14.11% |

| TESOL Quarterly | 11 | 12.94% |

| Language Learning & Technology | 10 | 11.76% |

| Foreign Language Annals | 9 | 10.59% |

| Computer Assisted Language Learning | 9 | 10.59% |

| Applied Linguistics | 8 | 9.41% |

| Modern Language Journal | 6 | 7.05% |

| Language Learning | 5 | 5.88% |

| RECALL | 3 | 3.53% |

| Language Assessment Quarterly | 3 | 3.53% |

| English for specific purposes | 3 | 3.53% |

| Language and Education | 2 | 2.35% |

| Language Testing | 1 | 1.18% |

| Studies in Second Language Acquisition | 1 | 1.77% |

| Assessing Writing | 1 | 1.77% |

| Language Teaching Research | 1 | 1.77% |

| Total | 85 | 100% |

| Variables | Definition | References | Research Aims |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Identification | [34] | To ascertain the eligibility of the research papers that demonstrate a clear link to CC | |

| Authors | Researchers who undertook the study | ||

| Title | The title of the research paper | ||

| Year | The year in which the scholarly papers were published | ||

| Journal | The journals in which the scholarly papers were published | ||

| Construct definition | |||

| Research theme | Identification of the themes present in the dataset which were largely defined by linguistic outcomes and non-linguistic outcomes | [36] | To ascertain construct definition |

| Study design | |||

| Methodology | Qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methodology | To ascertain construct definition | |

| Research techniques | Instruments and techniques employed in the dataset to collect data | [37] | |

| Study context | ESL, EFL, or combined | ||

| Operationalization of CC | |||

| Components of CC | Whether the articles report linguistic competence, sociolinguistic competence, strategic competence, discourse competence, or pragmatic competence | [1,3,4,5] | To ascertain construct operationalization |

| Instrumentation of tests & measures | Self-report questionnaires, likert scale type, elicitation tasks, assessment tasks are employed | To ascertain construct operationalization | |

| Language skills | Whether the articles report a language skill, namely reading, writing, listening, or speaking, or a combination of skills | To ascertain construct operationalization | |

| Theoretical frameworks | Whether studies report or employ theoretical frameworks related to CC | To ascertain construct operationalization | |

| Results | Findings from the articles |

| Themes and Sub-Themes | # of Studies | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|

| Construct Definition | ||

| 1. Beliefs and perceptions about CC | 18 | 21.18 |

| 1.1 Willingness to communicate | 6 | 7.06 |

| 1.2 Perceived CC | 7 | 8.24 |

| 1.3 Beliefs about NS and NNS | 5 | 5.88 |

| 2. Expansion of CC | 27 | 31.76 |

| 2.1 Intercultural Communicative Competence | 24 | 28.24 |

| 2.2 Multimodal Communicative Competence | 3 | 3.53 |

| 3. Mixed Specifications about CC | 22 | 25.88 |

| Construct Operationalization | ||

| 4. Test and Measures of CC and CLA | 18 | 21.18 |

| Total | 85 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mootoosamy, K.; Aryadoust, V. Transitioning from Communicative Competence to Multimodal and Intercultural Competencies: A Systematic Review. Societies 2024, 14, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14070115

Mootoosamy K, Aryadoust V. Transitioning from Communicative Competence to Multimodal and Intercultural Competencies: A Systematic Review. Societies. 2024; 14(7):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14070115

Chicago/Turabian StyleMootoosamy, Khomeshwaree, and Vahid Aryadoust. 2024. "Transitioning from Communicative Competence to Multimodal and Intercultural Competencies: A Systematic Review" Societies 14, no. 7: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14070115

APA StyleMootoosamy, K., & Aryadoust, V. (2024). Transitioning from Communicative Competence to Multimodal and Intercultural Competencies: A Systematic Review. Societies, 14(7), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14070115