Abstract

Most highly developed countries invest considerably in language training programmes for refugees, which are assumed to facilitate economic, social, and cultural integration. Although recent research has turned to particular patterns of host country language acquisition amongst refugees, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has hitherto remained understudied. Consequently, this article assesses changes in refugees’ uptake and outcomes of language training over the onset of the pandemic using longitudinal population data for Belgium (Flanders). Findings confirm theoretical expectations, as refugee cohorts entering the country after the onset of the pandemic exhibit lower Dutch language credentials, mostly due to lower enrolment and lower proficiency at intake for language courses. Furthermore, this study indicates that such changes are considerably weaker for highly educated and female refugees. These findings are interpreted in terms of increased vulnerability resulting from the pandemic as well as within-group diversity in potential barriers to integration in the host country.

1. Introduction

As host country language acquisition is widely considered an intrinsic dimension of the economic, social, and cultural integration of refugees, most highly developed countries invest considerably in formal language training programmes [1,2,3,4,5]. Host country language acquisition is assumed to stimulate contact with native speakers, facilitate educational opportunities, and provide access to other public or private services (e.g., employment services and childcare), allow refugees to communicate with employers and colleagues, and can also foster a sense of belonging to the host country [1,6]. Quantitative research has only recently started to fully acknowledge the fact that refugees exhibit vulnerabilities distinctive from other migrants by focussing on particular patterns and determinants of language acquisition amongst refugees [2,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Findings indicate that—in comparison to other types of migrants—refugees profit strongly from structured learning in formal language courses [7,8]. However, language acquisition has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which not only compromised social interaction and economic activity but also convoluted the organisation of language courses. This study is the first to assess changes in the uptake and outcomes of language training programmes over the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The fact that we currently lack understanding of how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected language acquisition amongst refugees is unfortunate both from a theoretical and a societal perspective. Regarding the former, according to the widely adopted three-pillar “exposure”, “efficiency”, and “incentives” theory of language acquisition [13,14], the COVID-19 pandemic is assumed to affect the uptake and outcomes of formal language training programmes in various ways. In addition to limited exposure due to the low availability of language courses and partial turn to digital language courses [15,16,17], incentive structures in terms of social and economic gains in times of social restrictions and limited labour market opportunities are also assumed to play a role. However, such assumptions have hitherto not been confronted with data. The assessment of how the uptake and outcomes of language training programmes changed during the pandemic also bears particular policy relevance. The available literature suggests that host country language learning inside and outside a classroom complement each other to maximise language acquisition [3,18]. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted social and economic life, implying that refugees arriving during the pandemic depend even stronger on language training programmes.

This study contributes to our understanding of language programme participation and outcomes amongst refugees in two ways. First, using longitudinal register data for cohorts entering Belgium (Flanders) before and after the onset of the pandemic, this is the first study to assess how refugees’ language programme enrolment and outcomes have changed in this period. Second, the available literature indicates that there is more individual-level socio-demographic variation within the group of refugees than when comparing refugees to other broad categories such as labour migrants [19]. Such variation is increasingly acknowledged in research and policy-making on language acquisition [1,10,20,21]. However, the routine usage of relatively small-scale (survey) data has hitherto hampered comparisons of different refugee profiles [9,10,22]. Consequently, this study draws on large-scale population data to assess whether changes in language programme uptake and outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic differ depending on refugees’ age at arrival, level of education, and gender. Hence, we provide novel information on refugee subgroups’ vulnerability to COVID-19-related complications in the acquisition of language credentials.

2. The Flemish Context

Across the globe, the COVID-19 pandemic affected refugee flows, daily opportunities for host country language acquisition, as well as the organisation of language training. With respect to migration flows, permanent migration to OECD countries fell by 30 percent to a historical low since 2003. The number of new asylum applications similarly plummeted by 31 percent in the first year since the COVID-19 pandemic, and the number of resettled refugees dropped by two-thirds compared to 2019 [23]. These decreases occurred in tandem with COVID-related barriers such as closing borders and tightening immigration regimes complicating migration routes for refugees [24,25,26]. Similarly, Flanders exhibits a 27 percent decrease in permanent immigration and the Belgian federal state (responsible for asylum) reports a 44 percent decrease in new asylum applications from 2019 to 2020 [27,28].

Regarding daily opportunities for language acquisition, similarly to many other countries, the March-May 2020 lockdown in Flanders implied that only so-called “essential” movements were allowed, including commuting, grocery shopping, or visiting post offices and petrol stations, whereas all “non-essential” shops were closed, remote work and adult education was obliged, and social gatherings were banned. A second large wave of infections resulted in a second (partial) lockdown from November 2020 implying a weaker limitation of social contacts, but also the closure of bars, restaurants, non-essential shops, and services involving close contact, in combination with the obligation of remote organisation of adult education and work, and social distancing in the workplace [29].

This study addresses participation in language courses and the acquisition of formal language credentials. Flemish language policy includes not only language classes but also intake tests of Dutch proficiency. The latter is intended to assign participants to the correct course and use standardised linguistic tests for proficiency (reading, writing, speaking, listening). Language classes follow the language levels of the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR), firstly focusing on basic interactions with support (i.e., A1-courses), then gradually increasing independence in specific situations (i.e., A2-courses), and later also providing skills to deal with most situations (i.e., B1- or higher-level courses) [30,31]. Flemish language policy for migrants adopts a monolingual approach to language acquisition, viewing the host country’s language as a tool necessary to transform ideas and to build up social capital, with little attention to the fact that second language learning also implies constructing a new self and relationship with one’s surroundings. This contrasts with contemporary scholarly work in applied linguistics that tests assumptions about acquisition as a psychological/cognitive process, presumed to reside in the mind of the individual, versus a socio-cognitive view that regards acquisition in terms of increasing meaningful participation in the world [32,33,34]. Consequently, the usage of the term “acquisition” in this study about language certificate acquisition should be interpreted in the context of Flemish language policy monolingual view on language acquisition as an individual cognitive process.

Formal language course participation was already hampered before the onset of the pandemic by structural barriers such as waiting lists, information deficits, lack of childcare, and travelling costs [2,10,31]. The pandemic resulted in an additional mixture of postponements and a rapid turn to digital tools in many countries [15,23], which is routinely assumed to disproportionally affect the most vulnerable groups of refugees [16,17,35]. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, language courses for refugees in Flanders were cancelled in March-April 2020 and the “Agencies for Adult Education” organising language courses for refugees with higher learning capacity invested maximally in digital classes thereafter. The organisation of language courses for groups with lower learning capacity by “Agencies for Basic Education” was hampered by the limited digital skills of targeted groups, as well as COVID regulations preventing physical courses.

3. Theory

In order to understand the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, we use the widely adopted three-pillar theoretical framework of language acquisition, consisting of (I) exposure, (II) incentives, and (III) efficiency [14].

The “exposure” pillar includes a wide range of passive or active learning opportunities for migrants to learn the host country’s language. The COVID-19 pandemic potentially affected both so-called pre- and post-migration sources of exposure [7,9,36,37,38,39,40]. Regarding the former, given the global negative impact of COVID-19 on educational opportunities [17], enrolment in language training in the origin country is presumably scarce during the pandemic. This not only potentially limits general linguistic skills, but also familiarity with the host country language (i.e., Dutch), or linguistically similar languages (e.g., German). With respect to post-migration exposure, the occurrence and intensity of social interaction with speakers of the host country’s language are likely to be limited by COVID-19 restrictions explicitly aimed at minimal social contact [29]. In addition, exposure to language courses during the pandemic is potentially complicated by limited availability or digital organisation which might exclude individuals without access to high-quality ICT or adequate digital skills [15,16,17]. The available literature suggests that cumbersome access to suitable wi-fi, particularly during closures of public buildings (e.g., libraries), concerns about data protection amongst migrants from repressive regimes, and privacy concerns amongst those in unfavourable housing circumstances further hamper online class attendance [15].

The “incentives” pillar refers to the expected (non-)economic returns on investments in language acquisition, or in this study the acquisition of language credentials. The available literature on incentives for language acquisition suggests two major pathways through which the pandemic might affect language training outcomes. First, whereas easier access to the host country’s human capital (e.g., education) and the labour market are widely recognised incentives to invest in the language acquisition [7,14,36,38,41,42,43], the pandemic has severely limited such opportunities—particularly during lockdown periods—which in turn might weaken this incentive amongst refugees. Second, in line with previous research, putting forward the possibility to engage in inter-ethnic contact as an incentive to invest in the host country’s language acquisition [3,7,39], regulations restricting social contact might have crippled this incentive to participate in formal language training.

The “efficiency” pillar refers to the extent to which a certain amount of exposure translates into language acquisition [14]. In contrast to the self-evident impact of the pandemic on exposure and incentives, it is assumed unlikely that such an external shock has directly affected individual levels of learning efficiency.

In line with the aforementioned mechanisms in terms of exposure and incentives, we put forward the following hypothesis. As a result of limitations in exposure and incentives during the COVID-19 period, we assume that refugee cohorts entering the country after the onset of the pandemic will exhibit lower language credentials (Hypothesis 1).

Finally, we can also adopt the three-pillar theoretical framework of language acquisition to theorise about potential population heterogeneity in how host country language acquisition changed since the start of the pandemic. First, in line with the available literature indicating that migrants’ host country language acquisition varies by age at arrival, and changes over the onset of the pandemic might also be age sensitive. In addition to the established fact that younger individuals possess superior digital skills and learning strategies, social contacts were most severely limited amongst older age groups during the pandemic [44], and the educational and economic incentives are assumed to be higher for younger refugees [7,13,14,16,21,37,45]. Consequently, younger refugees are expected to be less susceptible to changes in the acquisition of language credentials (Hypothesis 2).

Second, consistent with the previous literature identifying the level of education as an important differentiating factor in the efficiency of the host country’s language learning [7,19,38], but also digital skills [15], it is likely that refugees with higher educational qualifications suffered less from complications in language certificate acquisition over the onset of the pandemic (Hypothesis 3).

Third, with respect to potential gender differences in language acquisition, previous research presents conflicting expectations [2]. On the one hand, refugee women experience fewer opportunities to practice host country languages, and access to language classes is often complicated by family responsibilities such as caregiving (e.g., children) [2,10]. As a result, it might be expected that during the pandemic—a period characterised by increasing intra-household care needs and household chores—women exhibit stronger changes in language certificate acquisition over the onset of the pandemic than men (Hypothesis 4a). However, on the other hand, the literature also highlights that women typically adopt more efficient learning strategies [2,7,8,36], and—if the acquisition of language credentials is strongly related to employment—a weaker orientation towards labour force participation amongst female refugees [46,47] might imply a limited impact of suddenly decreasing labour market opportunities (Hypothesis 4b).

4. Data and Methods

This study uses unique longitudinal population data covering all refugees and asylum seekers who entered Belgium in 2016–2017 or 20201–2022 and subsequently resided in Flanders. This data is drawn directly from the Crossroads Bank for Civic Integration (“KBI”), which is the digital client monitoring and tracking instrument used by the Flemish Agency for Integration (“Agentschap Inburgering”) for intake meetings, language class reservation, and coaching of refugees [31]. A cohort approach is taken, in which changes in formally recognised language acquisition through language programmes since the onset of the pandemic are estimated by following-up refugees who entered the country in 2016–2017 for a maximum of two years, in comparison to refugees entering the country in 2020–2022 with the same duration of residence. As such the outcomes of the pre-pandemic cohorts cannot be influenced by the pandemic, whereas the outcomes of the latter cohorts are only composed of experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This paper studies changes in migrants’ language credentials over time. A migrant can exhibit four different positions, closely following the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR): (I) no Dutch language credentials, (II) successful completion of A1-courses, (III) A2-courses, and (IV) B1- or higher-level courses [30,31]. We estimate four sets of models. The first set (model A) estimates refugees’ highest language credentials (i.e., one of the aforementioned positions) over time since arrival in Belgium. These models are pooled multinomial models with parameter standard errors corrected for clustering. Exponentiated effects are interpreted as relative risk ratios, using no language credentials as the base category. Although this set of models allows us to accept or reject the aforementioned hypotheses, further sensitivity analyses assess specific components of formal language acquisition: uptake of language courses, level at intake, and progress since the start of participation. Consequently, the second set (model B) consists of discrete-time hazard models of entering a first language course by time since arrival to assess the timing and occurrence of participation. A logit link function implies that the exponentiated parameter estimates can be interpreted as odds ratios. Third, we use a set of logit regressions (model C) to assess whether refugees receive a first language credential at the intake test, which implies that the proficiency tests indicate that the migrant can start at a higher level. Fourth and finally (models D), pooled multinomial models estimate whether refugee participants exhibit progress in their Dutch language credentials after the start of enrolment, again based on the aforementioned four positions (no credentials, A1, A2, B1 or higher) using no progress as the base category and correcting parameter standard errors for clustering.

Within every set of models, we use the same sequence of four nested model specifications. The first specification simply estimates whether outcomes differ between the 2016–2017 and the 2020–2022 refugee cohorts using a COVID dummy variable, time measured as months since arrival (models A and B) or months since start of participation (models D), and interactions between COVID and time. The second specification controls for socio-demographic composition and will be used to address the first hypothesis. The demographic controls are region of origin (European countries from North Africa, other African, American countries, Australian countries, and Asian countries), age at arrival (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50+), and gender (male versus female). Additionally, controls for educational attainment (low ISCED 0–2, medium ISCED 3–4, high ISCED 5–6), language knowledge at arrival (Dutch, English, French, German, Italian, Greek, other Romance or Basque languages, other Germanic languages, Baltic Slavic Paleo-Siberian, and Ural languages, other Indo-European languages, Arabic, Berber languages, other Afro-Asian languages, Turkish, other Asian languages), and a time-varying indicator for first contact with the Flemish employment office (no contact versus first contact in the past year, first contact more than one year ago) are included. The third, fourth, and fifth specifications additionally include interaction terms between COVID and age, COVID and educational attainment, and COVID and gender to address the second, third, and fourth hypotheses.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Descriptive Results

Before assessing whether formally recognised language acquisition has changed, it is necessary to address differences in socio-demographic composition, which in turn are likely to affect language acquisition and thus bias the comparison between the 2016–2017 to the 2020–2022 cohorts.

Table 1 features clear differences—both in terms of unique individuals and monthly person periods—which need to be controlled for in the pooled multivariate models. Regarding country of birth, the share of refugees originating from European, American, and Australian countries has increased2, whereas the share of refugees from non-Northern African countries or Asia has decreased. The gender distribution of incoming refugees has become more male-dominated in the 2020–2022 cohort, with 71.16 percent males compared to 61.71 percent in the 2016–2017 cohort. The share of refugees accompanied by minor children has strongly decreased. In contrast, differences between the 2016–2017 and 2020–2022 refugee cohorts in terms of age at arrival and level of educational attainment are more limited. Regarding language knowledge at arrival, the share of refugees who report proficiency in Dutch or French, the most spoken national languages in Belgium, but also Arabic has decreased markedly when comparing the 2016–2017 to the 2020–2022 cohorts. Finally, the comparison of both cohorts in terms of a time-varying indicator for contact with the employment office indicates lower contact for the 2020–2022 cohort, which is presumably related to both more limited labour market opportunities but also a lower-than-average follow-up period for the most recently arrived refugees.

Table 1.

Sample size by socio-demographic control variables (unique individuals and person years), 2016–2017 and 2020–2022 refugee cohorts, Flanders, Belgium.

5.2. Model Results

5.2.1. Comparing Formal Language Acquisition before and during the Pandemic

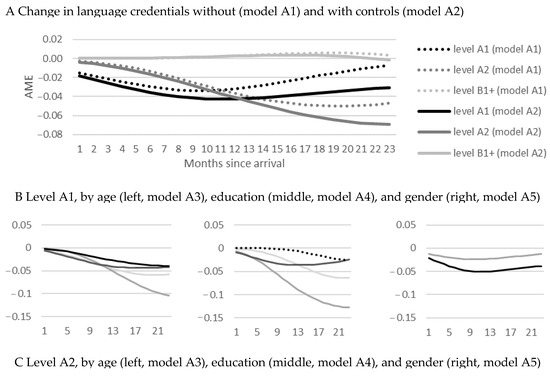

Figure 1 displays the results of models estimating the differences in Dutch language credentials between the 2016–2017 and 2020–2022 refugee cohorts (model A). Results indicate that—compared to the pre-COVID refugee cohorts—the 2020–2022 cohorts exhibit substantively lower probabilities of holding A1 or A2 Dutch language credentials (Figure 1A). Regarding the acquisition of B1 or even higher-level language credentials, the 2020–2022 cohorts display similar marginally higher probabilities. However, such uncontrolled estimates of change are likely to be influenced not only by COVID-related contextual factors but also by differential composition between refugee cohorts.

Figure 1.

Change in language credentials from 2016–2017 to 2020–2022 cohort in terms of Average Marginal Effects (AME), models A1–A5.

The comparison of model specifications 1 and 2 indicate that the aforementioned differentials in A1 or A2 language credentials become larger when controlling for differential socio-demographic composition (cf. Appendix A for full results). After controlling for the positively selective profile of the 2020–2022 cohorts, the results indicate an up to 5 and up to 7 percentage point decrease in the probability of holding an A1 or A1 language credential, respectively. These differentials emerge gradually over time as refugees have had more time to enrol in language training programmes. As a result of these estimates, the hypothesis that refugee cohorts entering the country after the onset of the pandemic exhibit lower formal language credentials compared to their pre-COVID counterparts is accepted (Hypothesis 1).

With respect to differential changes over the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, depending on refugees’ age at arrival, level of education at arrival, and gender (Figure 1B–D), the results indicate larger differentiation in the change by gender (Δ−2LL: 299.89; Δdf. 6; p < 0.000) and level of educational attainment (Δ−2LL: 394.06; Δdf. 18; p < 0.000) than age at entry (Δ−2LL: 72.69; Δdf. 18; p < 0.000). Differentiation by age is limited to inconsistent differentials in attaining B1+ level credentials for refugees who have been residing in the country for a longer period only, extremely limited differentials regarding A2 level language credentials, yet also a more attenuated negative change in A1 level attainment over the onset of the pandemic for 18–29 and particularly 20–29-year-olds at arrival. Consequently, the hypothesis that younger refugees are less susceptible to changes in formal language acquisition is rejected (Hypothesis 2).

Regarding varying changes by level of education, COVID-related penalties in formal language acquisition are limited amongst highly educated refugees, and the increase in B1 or higher-level credentials occurs amongst highly educated groups only. These patterns contrast with stronger decreases in the probability of holding an A1 credential for refugees with a medium level of educational attainment and stronger decreases in A2 credentials for refugees with a low or medium level of education over the onset of the pandemic. These findings are consistent with the expectation that negative changes in formal language acquisition are weakest amongst highly educated refugees (Hypothesis 3).

With respect to gender differences, COVID-related decreases in language credentials are strongest amongst male refugees, with considerable decreases in A1 and particularly A2 credentials. These patterns contrast with much more limited decreases amongst female refugees. As a result of these findings, the hypothesis that the change in formal language acquisition is greatest amongst women (Hypothesis 4a) is rejected, whereas the alternative hypothesis expecting stronger COVID-related penalties amongst male refugees is accepted (Hypothesis 4b).

5.2.2. Unpacking COVID-Related Changes into Enrolment and Progress Thereafter

As the aforementioned estimated changes in host country language credentials by refugees could result from COVID-induced changes regarding enrolment and intake test results, as well as changes regarding progress in Dutch language credentials after starting participation in language classes, this section further unpacks COVID-related shifts in language acquisition into several subcomponents.

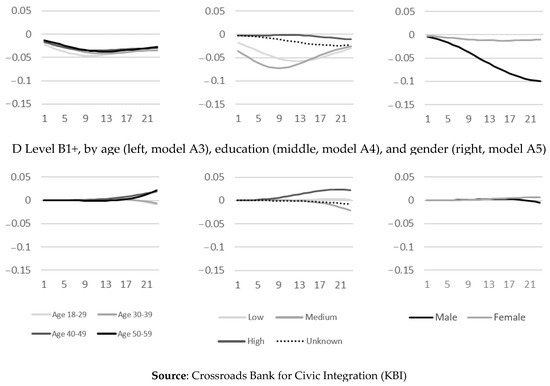

Figure 2 illustrates how the hazard of enrolling into language programmes, as well as the acquired level at enrolment has shifted from the 2016–2017 to 2020–2022 cohort. With respect to the enrolment hazard (Figure 2A), model estimates indicate a clear negative change from the 2016–2017 to 2020–2022 cohort, both without (model B1) and with socio-demographic controls (model B2). These lower uptake hazards are accumulated over time and there is no clear sign of recuperation amongst the 2020–2022 cohort as the effects do not turn positive at longer durations since arrival.

Figure 2.

Enrolment hazard and level at intake from the 2016–2017 to 2020–2022 cohort in terms of Average Marginal Effects (AME).

Differential effects of COVID on the uptake of language programmes by age at arrival and level of educational attainment (Figure 2B) indicate that the aforementioned differentials in COVID-related penalties in language credentials are related to differentiation in the postponement of enrolment. In contrast to limited variation by age (Δ−2LL: 8.43; Δdf. 6; p < 0.208), during the first nine months since arrival, drops in uptake over the onset of the pandemic are notably greater amongst medium-level and particularly lower-educated groups (Δ−2LL: 43.97; Δdf. 6; p < 0.000). This implies that low and medium-level-educated refugees exhibit a postponement of uptake, which is partly recuperated at higher durations since arrival. Similarly, gender-specific estimates of the COVID-related change in enrolment hazards illustrate postponement and partial recuperation amongst men, who are more strongly affected than women (Δ−2LL: 16.50; Δdf. 2; p < 0.000).

Furthermore, despite the finding that 2020–2022 refugee cohorts start language training later, Figure 2C indicates that these cohorts also display lower intake test results. When controlling for socio-demographic composition (model C2), the 2020–2022 cohort is 8.8 percentage points less likely to receive a language certificate at intake, suggesting that the longer timespan between arrival and enrolment does not entail informally acquired language skills for the cohorts during the pandemic. Although parameter estimates indicate the strongest COVID-related disadvantage in terms of intake tests for refugees in younger age categories, medium levels of educational attainment, and amongst men, group variation in the COVID-related decrease in intake level remains statistically insignificant (model C3, Δ−2LL: 4.78; Δdf. 3; p < 0.189; model C4, Δ−2LL: 6.96; Δdf. 3; p < 0.073; model C5, Δ−2LL: 3.55; Δdf. 1; p < 0.059).

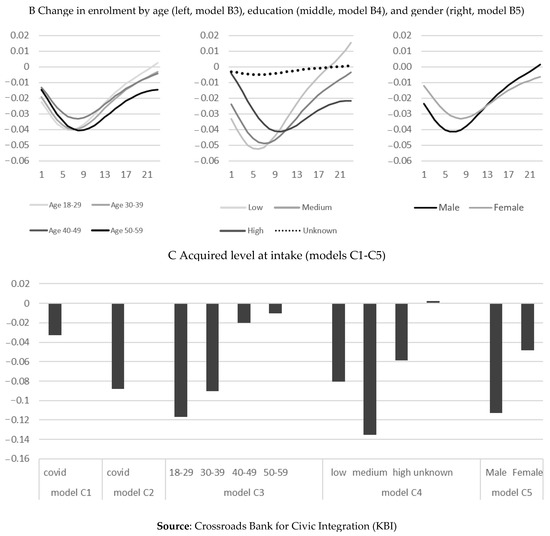

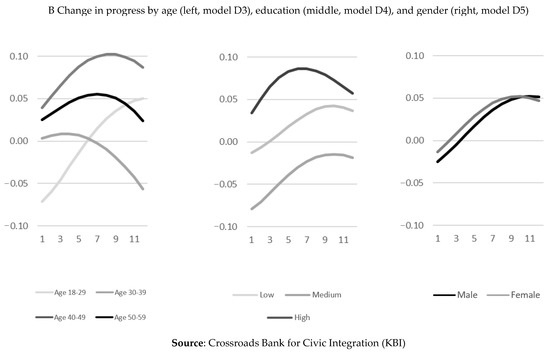

In addition to the contribution of lower enrolment hazards and lower intake levels of Dutch language credentials, Figure 3 illustrates whether shifts between the 2016–2017 and 2020–2022 cohorts in formal language acquisition might also be due to changing progress after enrolment. The finding that positive COVID-related changes largely disappear when controlling for socio-demographic composition (Figure 3A, model D2 versus D1) suggests that lower enrolment hazards for 2020–2022 cohorts entail a positively selective profile of participants in terms of progress. When taking socio-demographic selectivity into account, progress does not change dramatically over the onset of the pandemic, which contrasts with the aforementioned strong decreases in enrolment and starting levels.

Figure 3.

Change in formal language progress since the start of enrolment, comparing 2016–2017 to 2020–2022 cohorts in terms of Average Marginal Effects (AME).

In line with the main results, COVID-related penalties in terms of progress after enrolment occur amongst younger age categories only (Δ−2LL: 75.57; Δdf. 6; p < 0.000) (Figure 3B). Regarding educational attainment, in line with expectations as well as aforementioned education-specific results in terms of language level and programme enrolment, negative effects of the onset of the COVID pandemic in terms of progress since the start of enrolment into language programmes do not occur amongst highly educated refugee groups, which contrasts with a particularly pronounced COVID-related penalty amongst medium level educated, and mixed effects amongst low educated refugees (Δ−2LL: 64.14; Δdf. 4; p < 0.000). Finally, in line with the aforementioned results indicating a more limited negative impact of COVID on formally recognised language acquisition amongst female refugees, the positive shift in progress after starting enrolment in language classes is marginally stronger for women compared to men (Δ−2LL: 6.96; Δdf. 2; p < 0.05).

6. Conclusions

As the COVID-19 pandemic has presumably complicated host country language acquisition amongst refugees [15], yet such assumptions have hitherto not been confronted with data, this study is the first to empirically assess COVID-related shifts in the acquisition of language credentials. The first and foremost finding of this study is that refugee cohorts entering the country after the onset of the pandemic exhibit lower credentials compared to their counterparts before the onset of the pandemic. This finding confirms theoretical expectations based on reduced opportunities and incentives. In addition to potential limitations before migration (e.g., language training in the home country), language acquisition after migration has been limited in social settings due to COVID restrictions, in economic contexts as a result of economic shrinkage and remote working, and in formal structured language acquisition was less available due to cancelations or digital organisation [15,16,17]. Furthermore, this study indicates that low enrolment hazards and a lower intake level of proficiency are to be held responsible for generally lower levels of language credentials, rather than changes in progress after starting course participation.

Given that language programmes for refugees in the first years, since the arrival mostly focuses on the language level required for basic interaction [31], the finding that cohorts entering the country after the onset of the pandemic exhibit lower language credentials signals an important vulnerability amongst recent cohorts of refugees in terms of basic host country language credentials. Although only time can tell whether these refugee cohorts will manage to recover from COVID-related penalties in language acquisition, the potential longer-term relevance of the identified short-term disadvantage in language credentials is highlighted by previous research putting forward early enrolment in formal language programmes as a crucial factor to safeguard effective language acquisition in the longer run [3,7,36,37].

In addition, COVID-related language credentials penalties potentially entail unfavourable consequences [1] in terms of employment opportunities and wage potential in highly credential-based labour markets [5,10,13,48], but also regarding social integration into the host society [10,49] the development and educational trajectories of their children [50], and (mental) health [51,52]. As such, this study complements previous qualitative research identifying COVID-related social and economic vulnerabilities experienced by immigrants [53,54,55], which potentially accumulate and interact with vulnerabilities that already existed before the pandemic such as lengthy asylum procedures and difficulties ensuring adequate housing [1,56,57,58,59]. Consequently, specific inquiries of how COVID-related barriers to language acquisition interacted with pre-existing barriers and how this temporary context of host country language acquisition has affected refugees’ patterns of early integration in various domains should be encouraged.

The second main finding is that changes in formal language acquisition over the onset of the pandemic vary depending on the subgroup of refugees considered. Whereas limited and inconsistent differentiation by age at arrival contrasted with the theoretical expectations of weaker penalties amongst younger groups due to stronger learning and digital skills and stronger incentives in terms of social, educational, or labour market participation [10,16,21,44,45], the fact that particularly highly educated refugees seem relatively insensitive to COVID-related penalties is a consistent finding throughout this study. Highly educated groups are found to suffer less from COVID-induced postponement of enrolment and lower intake test levels but also exhibit a COVID-related premium regarding credential increases since the start of course participation. This finding adds to the available literature discussing higher-educated migrants’ higher efficiency in host country language acquisition and higher digital skills [7,10,15,19,38], by indicating that this subgroup of refugees also seems most resistant to COVID-related obstacles to host country language acquisition.

In addition, this study contributes to the inconclusive strand of the literature assessing gender differences in refugees’ host country language acquisition [2], providing clear evidence of stronger COVID-related penalties amongst male refugees. This finding suggests that—although female access to language classes is often complicated by family responsibilities such as caregiving (e.g., children) (Morrice et al., 2019; Bernhard and Bernhard, 2022)—women’s more efficient learning strategies might have protected them from stronger downward trends in language credentials. To conclude, this empirical assessment of varying changes in formal language acquisition depending on refugees’ age, educational attainment, and gender contributes to the available literature that stresses the diversity of resettled refugees and their differential capacities, needs, and opportunities for learning [10]. Although this study infuses the concept of heterogeneity between different refugee subgroups into the assessment of COVID-related shifts in language acquisition, further assessments of subgroup differences in the wide myriad of potential COVID-related effects on refugees should be encouraged.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Foundation Flanders (grant numbers G045722N and G0AHS24N) and the Research Council of the University of Antwerp (grant number INT-LIFE FFB240145).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available since the author(s) do not have the legal right to publicly share this information which was used under licence for the current study. Example code excerpts are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dries Lens for his advice and assistance in executing code using the latest possible data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Estimates of multinomial logit model of language acquisition (model A2), discrete-time hazard model of language programme enrolment (model B2), logit model of the acquired level at enrolment (model C2), and logit model of progress in language acquisition since start enrolment (model D2), relative risk ratios (RRR) and odds-ratios (OR) for 2016–2017 to 2020–2022 refugee cohorts.

Table A1.

Estimates of multinomial logit model of language acquisition (model A2), discrete-time hazard model of language programme enrolment (model B2), logit model of the acquired level at enrolment (model C2), and logit model of progress in language acquisition since start enrolment (model D2), relative risk ratios (RRR) and odds-ratios (OR) for 2016–2017 to 2020–2022 refugee cohorts.

| Model A2 | Model B2 | Model C2 | Model D2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level A1 | Level A2 | Level B1+ | ||||||||||

| RRR | Sig. | RRR | Sig. | RRR | Sig. | OR | Sig. | OR | Sig. | OR | Sig. | |

| Exposure (months) | ||||||||||||

| Linear | 1.30 | 0.000 | 1.61 | 0.000 | 2.03 | 0.000 | 1.35 | 0.000 | 0.98 | 0.00 | 1.35 | 0.000 |

| Square | 0.99 | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.000 | 0.97 | 0.000 | 0.97 | 0.000 | ||

| Cubic | 1.00 | 0.000 | 1.00 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| Cohort (pre- COVID is reference) | ||||||||||||

| COVID | 0.61 | 0.000 | 0.66 | 0.003 | 1.95 | 0.213 | 0.51 | 0.000 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 0.000 |

| COVID X linear months | 1.00 | 0.960 | 0.99 | 0.125 | 0.95 | 0.068 | 0.97 | 0.257 | 0.97 | 0.257 | ||

| COVID X square months | 1.00 | 0.033 | 1.00 | 0.033 | ||||||||

| Country of birth (European is reference) | ||||||||||||

| North African | 0.57 | 0.006 | 0.42 | 0.001 | 0.27 | 0.024 | 0.80 | 0.087 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.80 | 0.087 |

| Other African | 1.38 | 0.081 | 0.77 | 0.204 | 0.79 | 0.682 | 1.15 | 0.213 | 0.67 | 0.14 | 1.15 | 0.213 |

| American and Australian | 2.02 | 0.004 | 2.05 | 0.033 | 1.05 | 0.932 | 1.30 | 0.129 | 1.38 | 0.46 | 1.30 | 0.129 |

| Asian | 1.19 | 0.158 | 1.03 | 0.824 | 0.70 | 0.279 | 0.99 | 0.939 | 0.93 | 0.67 | 0.99 | 0.939 |

| Gender (male is reference) | ||||||||||||

| female | 0.90 | 0.031 | 1.18 | 0.008 | 1.36 | 0.040 | 1.10 | 0.004 | 0.91 | 0.19 | 1.10 | 0.004 |

| Children (none is reference) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 0.88 | 0.042 | 0.66 | 0.000 | 0.21 | 0.000 | 1.16 | 0.000 | 0.62 | 0.00 | 1.16 | 0.000 |

| Age (18–29 is reference) | ||||||||||||

| 30–39 | 0.79 | 0.000 | 0.71 | 0.000 | 0.54 | 0.000 | 1.10 | 0.005 | 0.78 | 0.00 | 1.10 | 0.005 |

| 40–49 | 0.72 | 0.000 | 0.68 | 0.000 | 0.47 | 0.000 | 1.14 | 0.004 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 1.14 | 0.004 |

| 50–59 | 0.45 | 0.000 | 0.34 | 0.000 | 0.16 | 0.000 | 1.02 | 0.762 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 1.02 | 0.762 |

| Educational attainment (low is reference) | ||||||||||||

| Medium | 2.56 | 0.000 | 4.37 | 0.000 | 5.99 | 0.000 | 1.33 | 0.000 | 2.38 | 0.00 | 1.33 | 0.000 |

| High | 3.69 | 0.000 | 9.54 | 0.000 | 14.18 | 0.000 | 1.31 | 0.000 | 4.21 | 0.00 | 1.31 | 0.000 |

| Unknown | 0.10 | 0.000 | 0.26 | 0.000 | 0.08 | 0.009 | 0.07 | 0.000 | 2.04 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.000 |

| Language knowledge at arrival | ||||||||||||

| Dutch | 1.36 | 0.005 | 3.68 | 0.000 | 8.56 | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.887 | 3.82 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.887 |

| English | 1.63 | 0.000 | 2.57 | 0.000 | 3.95 | 0.000 | 1.10 | 0.017 | 1.99 | 0.00 | 1.10 | 0.017 |

| French | 0.87 | 0.291 | 0.81 | 0.154 | 0.85 | 0.619 | 0.73 | 0.000 | 1.21 | 0.26 | 0.73 | 0.000 |

| German | 0.81 | 0.469 | 1.16 | 0.685 | 2.43 | 0.118 | 0.82 | 0.288 | 1.78 | 0.11 | 0.82 | 0.288 |

| Italian | 0.43 | 0.012 | 0.62 | 0.229 | 1.38 | 0.658 | 0.78 | 0.283 | 1.93 | 0.18 | 0.78 | 0.283 |

| Greek | 0.63 | 0.615 | 0.64 | 0.641 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.91 | 0.816 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.91 | 0.816 |

| Other Romance or Basque | 1.02 | 0.912 | 0.63 | 0.139 | 0.88 | 0.812 | 0.82 | 0.195 | 0.75 | 0.47 | 0.82 | 0.195 |

| Other Germanic | 0.89 | 0.779 | 0.72 | 0.759 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 1.49 | 0.227 | 1.22 | 0.78 | 1.49 | 0.227 |

| Baltic Slavic Paleo-Siberian, Ural | 1.08 | 0.779 | 2.41 | 0.012 | 4.18 | 0.009 | 1.51 | 0.008 | 1.26 | 0.48 | 1.51 | 0.008 |

| Other Indo-European | 1.00 | 0.971 | 0.87 | 0.152 | 0.92 | 0.697 | 1.01 | 0.801 | 0.91 | 0.43 | 1.01 | 0.801 |

| Arabic | 1.19 | 0.029 | 1.37 | 0.002 | 1.65 | 0.071 | 1.60 | 0.000 | 0.58 | 0.00 | 1.60 | 0.000 |

| Berber | 3.70 | 0.002 | 8.31 | 0.000 | 2.66 | 0.384 | 3.02 | 0.000 | 1.60 | 0.48 | 3.02 | 0.000 |

| Other Afro-Asian | 1.06 | 0.716 | 1.29 | 0.171 | 0.55 | 0.274 | 1.33 | 0.005 | 0.81 | 0.38 | 1.33 | 0.005 |

| Other African | 1.20 | 0.244 | 1.12 | 0.524 | 0.90 | 0.828 | 1.08 | 0.395 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 1.08 | 0.395 |

| Turkish | 1.57 | 0.000 | 2.24 | 0.000 | 3.55 | 0.000 | 1.58 | 0.000 | 1.07 | 0.66 | 1.58 | 0.000 |

| Other Asian | 1.14 | 0.416 | 0.88 | 0.524 | 0.67 | 0.422 | 0.96 | 0.725 | 0.87 | 0.54 | 0.96 | 0.725 |

| Contact with Employment Office (no contact is reference) | ||||||||||||

| First contact in past year | 2.03 | 0.000 | 4.71 | 0.000 | 7.21 | 0.000 | 1.54 | 0.000 | 1.38 | 0.00 | 1.54 | 0.000 |

| First contact 1+ year ago | 1.88 | 0.000 | 5.02 | 0.000 | 8.76 | 0.000 | 0.78 | 0.079 | 2.38 | 0.00 | 0.78 | 0.079 |

Notes

| 1 | For 2020 we exclude those who entered in January as this preceded the pandemic in Belgium. |

| 2 | Further analyses (detailed results not shown due to privacy regulations) indicate that the pronounced increase of refugees originating from American and Australian countries is mostly due to a sharp increase in refugees from El Salvador and to a lesser extent Colombia. |

References

- OECD. Language Training for Adult Migrants, Making Integration Work; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard, S.; Bernhard, S. Gender differences in second language proficiency-Evidence from recent humanitarian migrants in Germany. J. Refug. Stud. 2022, 35, 282–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehne, J.; Michalowski, I. Long-Term Effects of Language Course Timing on Language Acquisition and Social Contacts: Turkish and Moroccan Immigrants in Western Europe. Int. Migr. Rev. 2016, 50, 133–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiswick, B.R.; Rebhun, U.; Beider, N. Language Acquisition, Employment Status, and the Earnings of Jewish and Non-Jewish Immigrants in Israel. Int. Migr. 2020, 58, 205–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyar-Busto, M.; Mato Díaz, F.J.; Gutiérrez, R. Immigrants’ educational credentials leading to employment outcomes: The role played by language skills. Rev. Int. Organ. 2020, 167–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibel, V. What Do Migrants Know About Their Childcare Rights? A First Exploration in West Germany. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2021, 22, 1181–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosyakova, Y.; Kristen, C.; Spörlein, C. The dynamics of recent refugees’ language acquisition: How do their pathways compare to those of other new immigrants? J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2021, 48, 989–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristen, C.; Sueuring, J. Destination-language acquisition of recently arrived immigrants: Do refugees differ from other immigrants? J. Educ. Res. Online 2021, 13, 128–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Tubergen, F. Determinants of Second Language Proficiency among Refugees in the Netherlands. Soc. Forces 2010, 89, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrice, L.; Tip, L.K.; Collyer, M.; Brown, R. ‘You can’t have a good integration when you don’t have a good communication’: English-language Learning among Resettled Refugees in England. J. Refug. Stud. 2019, 34, 681–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzo, M. Moving on from Dutch to English: Young refugees feeling betrayed by the Dutch language integration policy and seeking for more inclusive environments. J. Refug. Stud. 2022, 35, 348–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzo, M.; Nerghes, A. Dutch without the Dutch: Discourse, policy, and program impacts on the social integration and language acquisition of young refugees (ages 12–23). Soc. Identities 2020, 26, 842–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiswick, B.R.; Miller, P.W. The Endogeneity between Language and Earnings: International Analyses. J. Labor Econ. 1995, 13, 246–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiswick, B.R.; Miller, P.W. A model of destination-language acquisition: Application to male immigrants in Canada. Demography 2001, 38, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullin, C. Migrant integration services and coping with the digital divide: Challenges and opportunities of the COVID-19 pandemic. Volunt. Sect. Rev. 2021, 12, 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, K.; Imran, S. The digital divide and social inclusion among refugee migrants. Inf. Technol. People 2015, 28, 344–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Connected Education for Refugees: Addressing the Digital Divide. In UNHCR Education Team in the Division of Resilience and Solutions; Agency UTUR, Ed.; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schuller, K. Der Einfluss Des Integrationskurses Auf Die Integration Russisch-Und Türkischstämmiger Integrationskursteilnehmerinnen Qualitative Ergänzungsstudie Zum Integrationspanel; Des Forschungsgruppe des Bundesambtes Working Paper 37; Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF) Forschungszentrum Migration, Integration und Asyl (FZ): Nuremberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sporlein, C.; Kristen, C. Educational Selectivity and Language Acquisition among Recently Arrived Immigrants. Int. Migr. Rev. 2019, 53, 1148–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozar, O.; Yates, L. Factors in language learning after, 40, Insights from a longitudinal study. Int. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach. 2019, 57, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ajlan, A. Older Refugees in Germany: What Are the Reasons for the Difficulties in Language-learning? J. Refug. Stud. 2021, 34, 2449–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solheim, E.F.; La Parra-Casado, D. Identifying Refugees and Other Migrant Groups in European Large-scale Surveys: An Explorative Analysis of Integration Outcomes by Age Upon Arrival, Reasons for Migration and Country-of-birth Groups Using the European Union Labour Force Survey 2014 Ad Hoc Module. J. Refug. Stud. 2019, 32, i183–i193. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. International Migration Outlook 2021; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Guadagno, L. Migrants and the COVID-19 pandemic: An initial analysis. In Migration Research Series; International Organization for Migration (IOM)—United Nations: Grand-Saconnex, Switzerland, 2021; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S.; Bergmann, J. (Im)mobility in the Age of COVID-19. Int. Migr. Rev. 2021, 55, 660–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.L.; Eger, M.A. Suppression, Spikes, and Stigma: How COVID-19 Will Shape International Migration and Hostilities toward It. Int. Migr. Rev. 2021, 55, 640–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistiek Vlaanderen. Internationale Migratie [“International Migration”]. 2021. Available online: https://www.vlaanderen.be/statistiek-vlaanderen/bevolking/internationale-migratie (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- CGVS. Asielstatistieken 2020 2021, 2022 [“Asylum Statistics 2020 2021, 2022”]; Commissariaat-Generaal voor de Vluchtelingen en de Staatlozen: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wolters Kluwer. Overzicht van Alle Wettelijke Maatregelen Tegen COVID-19; Opgehaald van LegalWorld; Wolters Kluwer N.V.: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Qualitative Aspects of Spoken Language Use—Table 3 (CEFR 3.3): Common Reference Levels. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages/table−3-cefr−3.3-common-reference-levels-qualitative-aspects-of-spoken-language-use (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Devlieger, M.; Lambrechts, D.; Steverlynck, C.; Van Woensel, C. Verbindingen: Eindrapport Werkjaar 2012–2013 van de Inhoudelijke Inspectie Inburgering [“Connections: 2012_2013 Report of Inspection Integration”]; Vlaamse Overheid—Onderwijsinspectie—Inburgering: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kramsch, C. Afterword: The multilingual turn in language teacher education. Lang. Educ. 2022, 36, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, S.S. The Social Turn in Second Language Acquisition; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, D. Toward a sociocognitive approach to second Llanguage acquisition. Mod. Lang. J. 2002, 86, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Cobo, M.; Garcia-Martin, J.; Bianco, R. Will the “normality” times come back? L2 learning motivation between immigrants and refugees before COVID-19. XLinguae 2021, 14, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristen, C.; Mühlau, P.; Schacht, D. Language acquisition of recently arrived immigrants in England, Germany, Ireland, and the Netherlands. Ethnicities 2016, 16, 180–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, G. Age at immigration and second language proficiency among foreign-born adults. Lang. Soc. 1999, 28, 555–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamuti-Trache, M. Language Acquisition among Adult Immigrants in Canada: The Effect of Premigration Language Capital. Adult Educ. Q. 2013, 63, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espenshade, T.J.; Fu, H. An Analysis of English-Language Proficiency among U.S. Immigrants. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1997, 62, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.-S.; Xi, J. Structural and Individual Covariates of English Language Proficiency. Soc. Forces 2008, 86, 1079–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiswick, B.R.; Miller, P.W. Immigrant earnings: Language skills, linguistic concentrations and the business cycle. J. Popul. Econ. 2002, 15, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesch, G.S. Language Proficiency among New Immigrants: The Role of Human Capital and Societal Conditions:The Case of Immigrants from the Fsu in Israel. Sociol. Perspect. 2003, 46, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Tubergen, F.; Kalmijn, M. Destination-Language Proficiency in Cross-National Perspective: A Study of Immigrant Groups in Nine Western Countries. Am. J. Sociol. 2005, 110, 1412–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; Berlin, J.; Kiti, M.C.; Del Fava, E.; Grow, A.; Zagheni, E.; Melegaro, A.; Jenness, S.M.; Omer, S.B.; Lopman, B.; et al. Rapid Review of Social Contact Patterns During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Epidemiology 2021, 32, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özmete, E.; Pak, M.; Duru, S. Problems and Issues Concerning Social Integration of Elderly Refugees in Turkey. J. Refug. Stud. 2021, 35, 93–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salikutluk, Z.; Menke, K. Gendered integration? How recently arrived male and female refugees fare on the German labour market. J. Fam. Res. 2021, 33, 284–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spehar, A. Navigating Institutions for Integration: Perceived Institutional Barriers of Access to the Labour Market among Refugee Women in Sweden. J. Refug. Stud. 2021, 34, 3907–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dustmann, C.; Fabbri, F. Language Proficiency and Labour Market Performance of Immigrants in the UK. Econ. J. 2003, 113, 695–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinovic, B.; van Tubergen, F.; Maas, I. Dynamics of Interethnic Contact: A Panel Study of Immigrants in the Netherlands. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2008, 25, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnepf, S.V. Immigrants’ educational disadvantage: An examination across ten countries and three surveys. J. Popul. Econ. 2007, 20, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemitro, C.; D’Andrea, G.; Cesa, F.; Martinotti, G.; Pettorruso, M.; Di Giannantonio, M.; Muratori, R.; Tarricone, I. Language proficiency and mental disorders among migrants: A systematic review. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 64, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, A.B.; Quinn, N. Integration or Isolation? Refugees’ Social Connections and Wellbeing. J. Refug. Stud. 2019, 34, 328–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardon, L.; Hari, A.; Zhang, H.; Hoselton, L.P.S.; Kuzhabekova, A. Skilled immigrant women’s career trajectories during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. Equal. Divers. Incl. 2022, 41, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Bo, B.; Tjoflat, I.; Eslen-Ziya, H. Immigrants in Norway: Resilience, challenges and vulnerabilities in times of COVID-19. J. Migr. Health 2022, 5, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popyk, A.; Pustulka, P. Educational Disadvantages during COVID-19 Pandemic Faced by Migrant Schoolchildren in Poland. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2022, 24, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosyakova, Y.; Brenzel, H. The role of length of asylum procedure and legal status in the labour market integration of refugees in Germany. Soz. Welt 2020, 71, 123–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hainmueller, J.; Hangartner, D.; Lawrence, D. When lives are put on hold: Lengthy asylum processes decrease employment among refugees. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1600432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hvidtfeldt, C.; Schultz-Nielsen, M.L.; Tekin, E.; Fosgerau, M. An estimate of the effect of waiting time in the Danish asylum system on post-resettlement employment among refugees: Separating the pure delay effect from the effects of the conditions under which refugees are waiting. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissoon, P. From persecution to destitution: A snapshot of asylum seekers’ housing and settlement experiences in Canada and the United Kingdom. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2010, 8, 4–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).