European Tendencies of Territorialization of Income Conditional Policies to Insertion: Systematic and Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Fonts

2.3. Selection Process and Data Collection

3. Results

3.1. Research Question

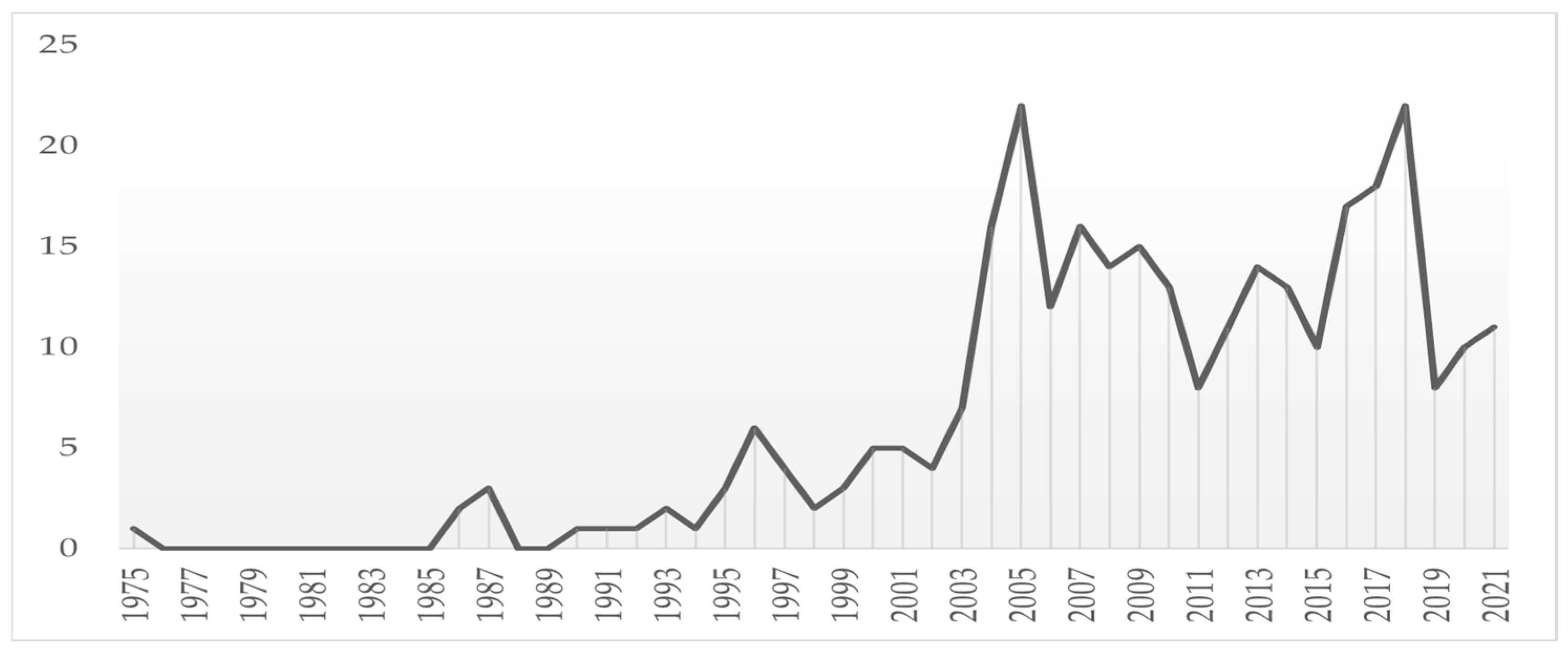

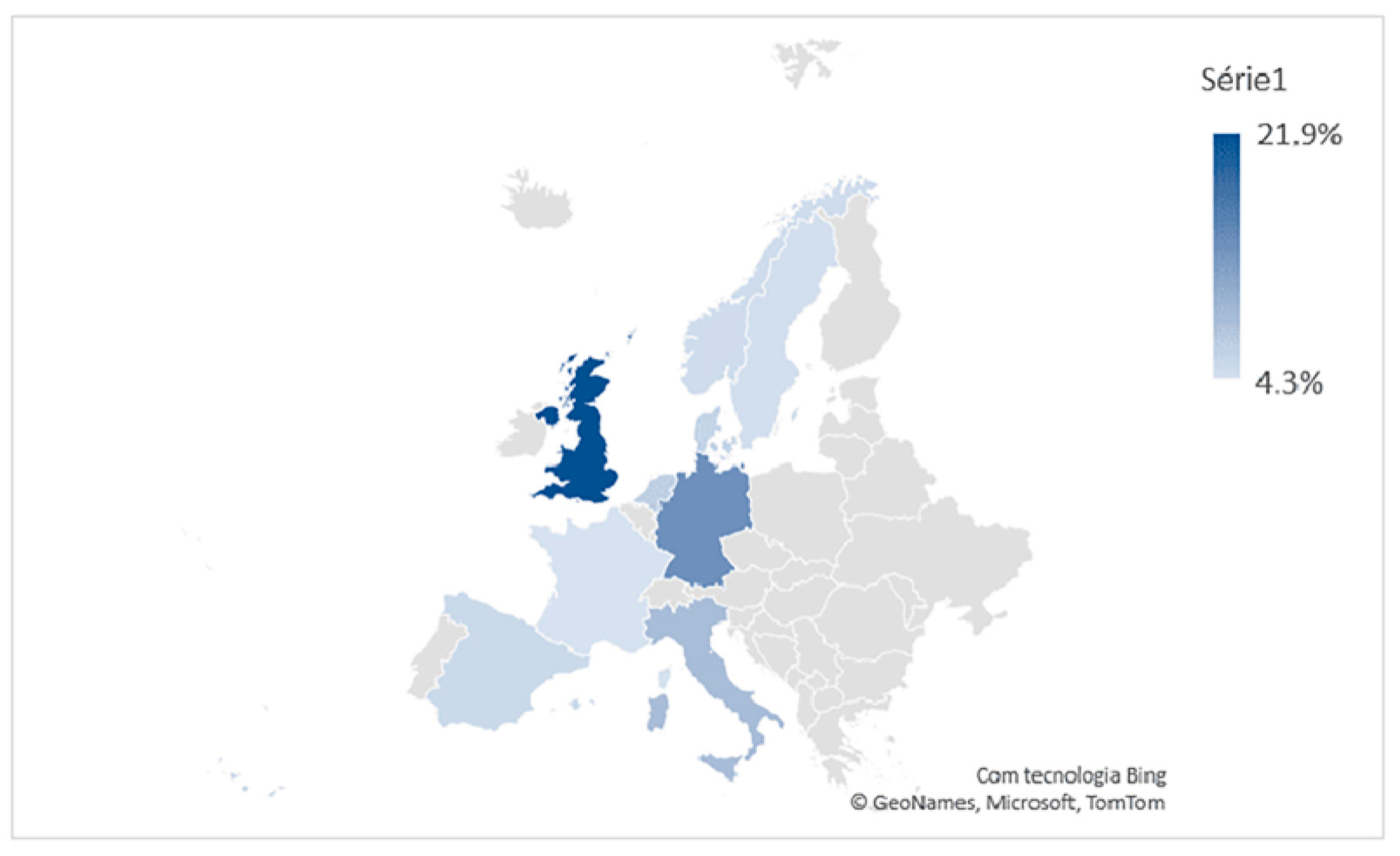

3.2. Publications Evolution (1975–2022)

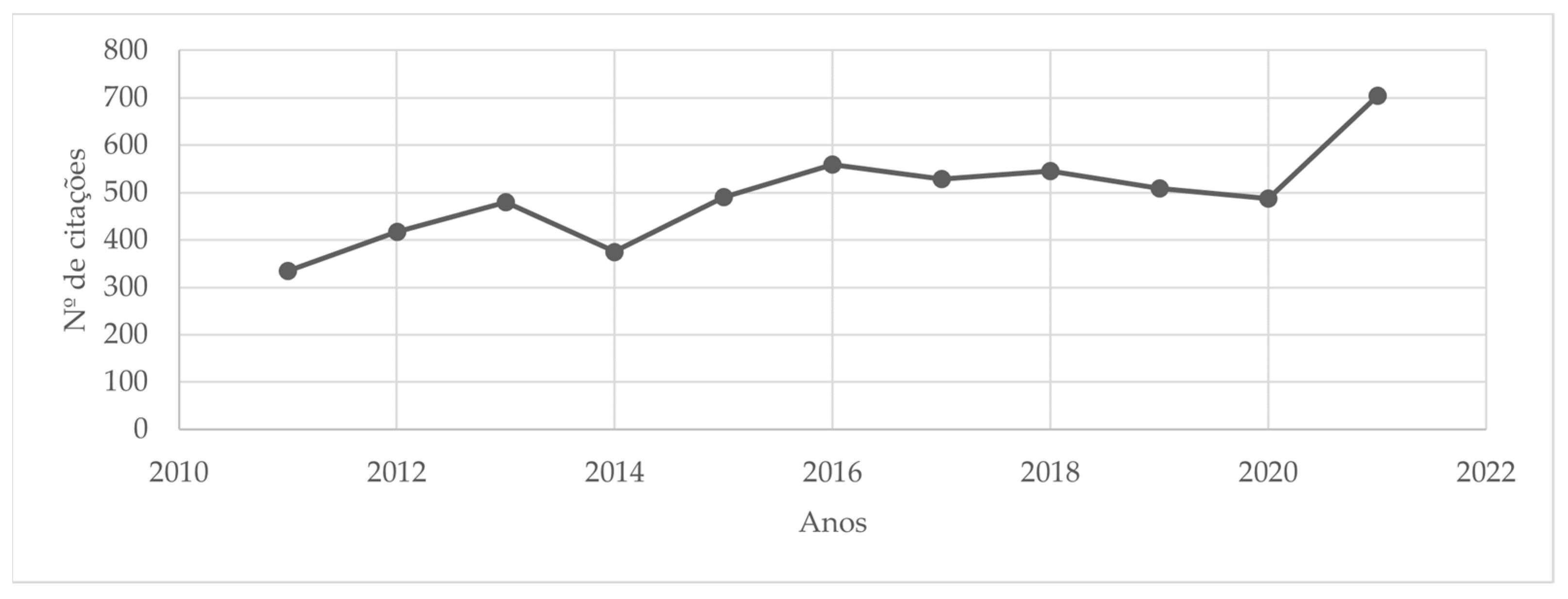

3.3. Citation Analysis

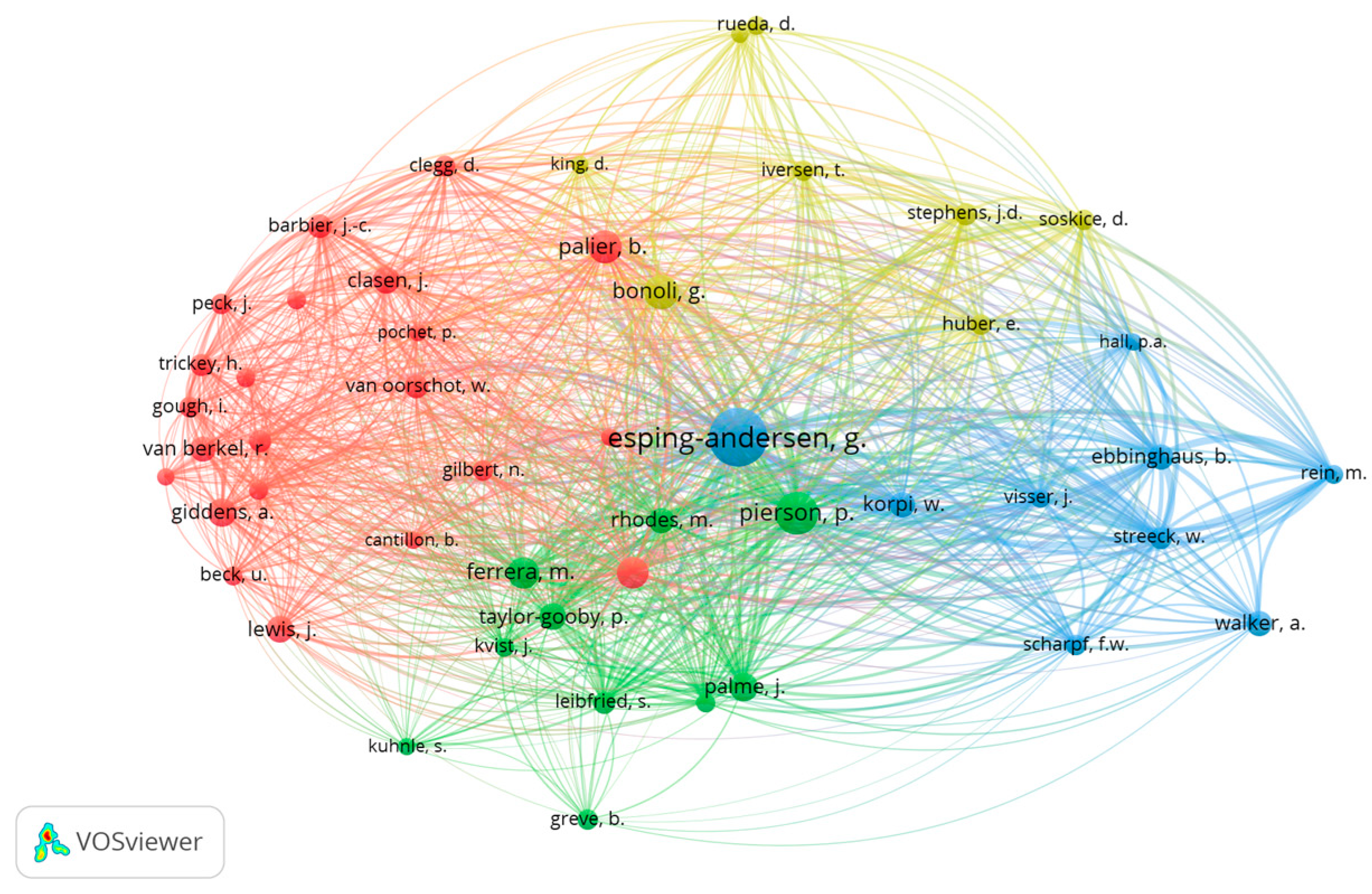

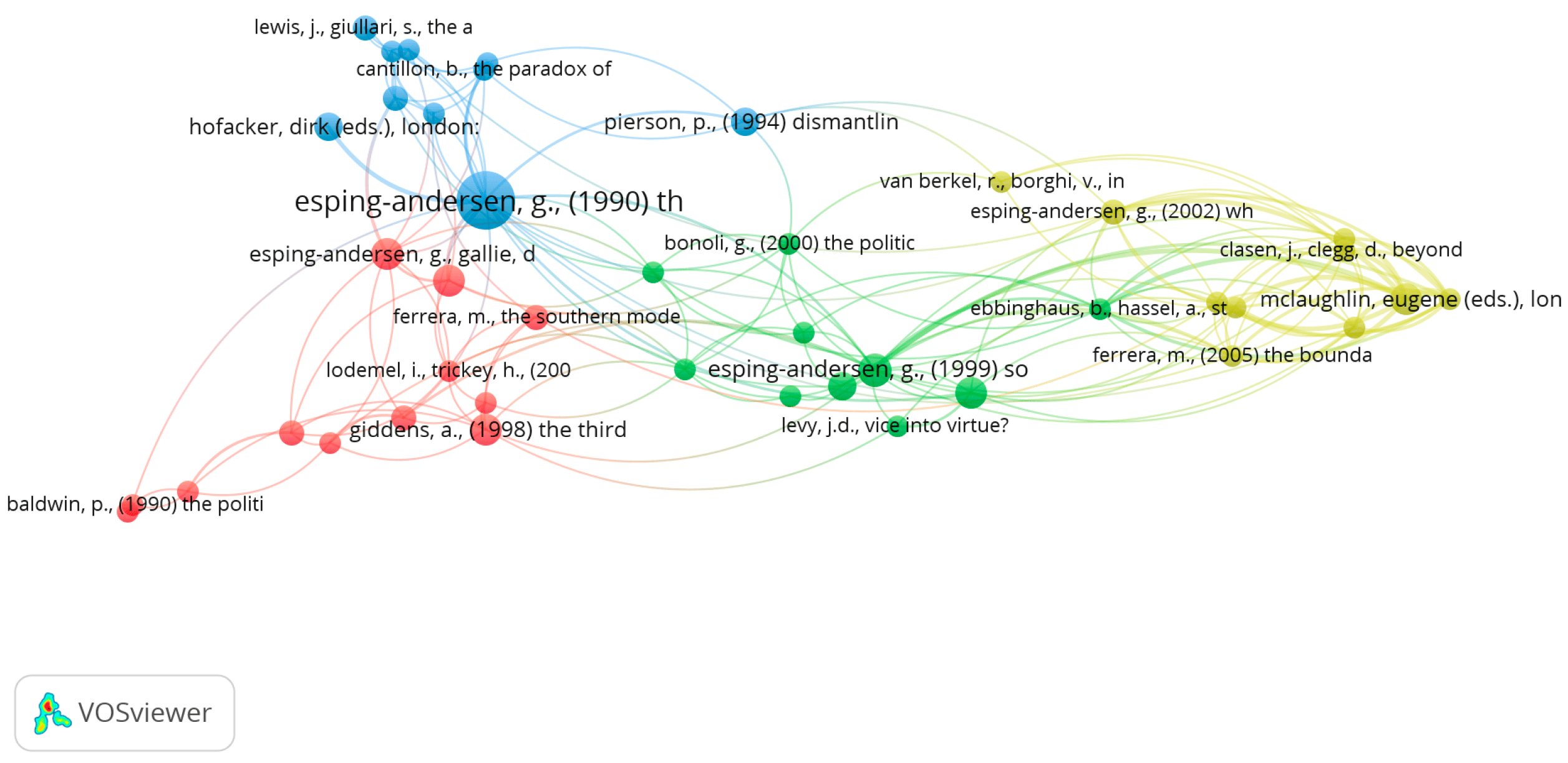

3.4. Co-Citation Analysis

3.5. Cluster Analysis

- Cluster 1: The reconfiguration of the Welfare State (17 items);

- Cluster 2: The workfare model (14 items);

- Cluster 3: New social risks (14 items);

- Cluster 4: The decentralization and territorialization of ICIP (7 items).

3.5.1. Cluster 1: The Reconfiguration of the Welfare State

3.5.2. Cluster 2: Workfare Model

3.5.3. Cluster 3: New Social Risks

3.5.4. Cluster 4: The Decentralization and Territorialization of ICIP

3.6. Trends around Territorialization of ICIP in the Different Models of the Welfare State

3.6.1. Northern Europe

3.6.2. Central Europe

3.6.3. Western Europe

3.6.4. Mediterranean Europe

4. Discussion

- In the decentralization model, based on the principle of vertical subsidiarity and, simultaneously, on horizontal intergovernmental arrangements in which the decision-making, administrative and fiscal process is transferred to the regional level, and there is no intervention by the central government, the regions have the autonomy to regulate, implement and supervise the ICIP, resulting in different eligibility criteria and social integration services in the territory, creating deep territorial inequalities.

- As for the decentralization process based on the hierarchical model, the state holds legislative and fiscal power, and based on the logic of centralism and intergovernmental cooperation, it gives the autonomous communities the power to implement specific policies and evaluate measures to support the ICIP [76]. Hierarchical decentralization is more effective in terms of maintaining territorial cohesion since it establishes the framework law, and the regions have the autonomy to formulate their specific policies around national objectives, which are subject to monitoring by coordination and cooperation mechanisms at the central level and across the whole territory [77].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Cluster | Author | Article | No of Co-Citations | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [17] Esping-Andersen, G., Gallie, D., Hemerijck, A, & Myers, J. | Why we need a new Welfare State? | 6 | Qualitative |

| [78] Giddens, A. | The third way: the renewal of social democracy | 6 | Qualitative | |

| [30] Pierson, P | The new politics of the welfare state | 6 | Qualitative | |

| [22] Ferrera, M. | Welfare State in Southern Europe: fighting and social exclusion in Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece | 4 | Qualitative | |

| [23] Beck, U. | Risk Society: towards a new modernity | 4 | Qualitative | |

| 2 | [24] Esping-Andersen, G. | Social foundations of Postindustrial Economics | 7 | Qualitative |

| [26] Torfing, J. | Workfare with welfare: recent reforms of the Danish welfare state | 6 | Qualitative | |

| [75] Van Oorschot, W. | Making the difference in social Europe: deservingness perceptions among citizens of European welfare states | 5 | Quantitative | |

| 3 | [29] Esping-Andersen, G. | The three worlds of Welfare capitalism | 21 | Qualitative |

| [30] Pierson, P. | Dismantling the welfare state? | 5 | Qualitative | |

| [31] Blossfeld, H., Buchholz, S., & Hofacker, D. | Globalization, uncertainty, and late careers in society. | 5 | Quantitative | |

| [32] Bonoli, G. | The politics of new social policies. Providing coverage against new social risks in mature welfare states | 4 | Qualitative | |

| [33] Lewis, J. & Giullari, S. | The adult worker model family, gender equality and care: the search for new policy principles and possibilities and problems of a capabilities approach | 4 | Qualitative | |

| 4 | [34] Ferrera, M. | The boundaries of welfare European integration and the new spatial politics of social integration | 3 | Qualitative |

| [37] Finn, D. | Welfare to workfare: the local dimension | 3 | Qualitative | |

| [38] Gough, I. | Social assistance regimes: a cluster analysis | 3 | Mixed models |

| 1 | Esping-Andersen is a sociologist and Professor of Sociology at the University of Bocconi, Milan and Professor Emeritus at the University of Pompeu Fabra. In 2009, he was appointed professor by ICREA—Academia. One of the most prominent publications in the area of social policy was the book, The Three Worlds of Welfare State Capitalism, also awarded by APSA’s Aaron Wildavsky and by the Social Foundation of Post-industrial Economies. |

| 2 | Pierson is a Professor of Political Science at the University of California, and from 2007 to 2010, he was Chair of the Department of Political Science at Berkeley. He is on the editorial boards of The American Political Science Review, Perspectives on Politics and The Annual Review of Political Science. His book, Is Your job Dismantling the Welfare State? Reagan, Thatcher and Politics of Retrenchment, was awarded by the American Political Science Association as the best book on American national politics. |

| 3 | Bonoli is an economist, Professor at the University of Lausanne and member of the projects, “Coupled Inequalities” and “Vulnerability due to lack of employment: companies, inequalities and job loss”. |

References

- Barca, F.; McCann, P.; Rodriguez-Pose, A. The case of regional development intervention: Place-based vs place-neutral approaches. J. Reg. Sci. 2012, 52, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, M.; Rice, D. Integrating Social and Employment Policies in Europe; Edward Elgar Publish: Cheltenham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, R.; Seixas, P. Territorialization of public policies, process or approach? Port. Rev. Reg. Stud. 2019, 55, 47–60. Available online: http://review-rper.com/index.php/rper/article/view/9 (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Capucha, L. Desafios da Pobreza, 1st ed.; Celta Editora: Oeiras, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Heindenreich, M.; Graziano, P.R. Lost in activation? The governance of activation policies in Europe. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2014, 23, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentzen, T.; Dahl, E. Active labour market programes in Norway: Are they helful for social assistance recipients? J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2005, 15, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazepov, Y. The subsidiarization of social policies: Actors, processes, and impacts. Eur. Soc. 2008, 10, 247–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.C.; Teixeira, A.A. Methods of assessing the evolution of science: A review. Eur. J. Sci. Res. 2012, 68, 616–635. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.701.2231&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Azevedo, L.F.; Sousa-Pinto, B. Avaliação crítica de uma revisão sistemática e meta- análise: Da definição da questão de investigação à pesquisa de estudos primários. Rev. Da Soc. Port. De Anestesiol. 2019, 28, 53–56. Available online: https://revistas.rcaap.pt/anestesiologia/article/view/17320 (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Tyndall, J. AACODS Checklist; Flinders University: Bedford Park, Australia, 2010; Available online: https://dspace.flinders.edu.au/dspace/ (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Heclo, H. Frontiers of social policy in Europe and America. Policy Sci. 1975, 6, 403–421. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4531617 (accessed on 7 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Nickell, S.; Layard, R. Labor market institutions and economic performance. In Handbook of Labor Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 3, pp. 3029–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Gooby, P. New Risks, New Welfare: The Transformation of the European Welfare State; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacquant, L. The penalization of poverty and the rise of neoliberalism. Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 2001, 9, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbinghaus, B. Reforming Early Retirement in Europe, Japan and the USA; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascall, G.; Lewis, J. Emerging gender regimes and policies for gender equality in a wider Europe. J. Soc. Policy 2004, 33, 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esping-Andersen, G.; Gallie, D.; Hemerijck, A.; Myles, J. Why We Need a New Welfare State, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hemerijck, A. In search of a new welfare state in Europe: Na international perspective. In The Welfare State in Post-Industrial Society: A Global Perspective; Hendricks, J., Powel, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 71–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Gooby, P. The new welfare settlement in Europe. Eur. Soc. 2008, 10, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, P. The new politics of Welfare State. World Politics 1996, 48, 143–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green-Petersen, C.; Kees, V.; Hemerijck, A. Neo-liberalism, the ‘third way’ or what? Recent social democratic welfare policies in Denmark and the Netherlands. J. Eur. Public Policy 2001, 8, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrera, M. Welfare Reform in Southern Europe: Fighting Poverty and Social Exclusion in Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Greece, 1st ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity, 1st ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen, G. Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economies, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Van Berkel, R.; Flemming, L.; Caswell, D. Introduction: Frontline delivery of welfare-to-work in different European contexts. Int. Soc. Secur. Rev. 2018, 71, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torfing, J. Workfare with welfare: Recent reforms of the Danish welfare state. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 1999, 9, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hespanha, P. Políticas sociais: Novas abordagens, novos desafios. Rev. Ciências Sociais 2008, 39, 5–15. Available online: http://www.repositorio.ufc.br/handle/riufc/752 (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- Nelson, M. Making markets with active labor market policies: The influence of political parties, welfare regimes and economic change on spending on different types of policies. Eur. Political Sci. Rev. 2012, 5, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esping-Andersen, G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, 1st ed.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pierson, P. Dismantling the Welfare State? Reagan, Thatcher and the Politics of Retrenchment, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld, H.; Buchholz, S.; Hofäcker, D. Globalization, Uncertainty and Late Careers in Society, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonoli, G. The politics of new social policies: Providing coverage against new social risks in mature welfare states. Policy Politics 2005, 33, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.; Giullari, S. The adult worker model family, gender equality and care: The search for new policy principles and the possibilities and problems of a capabilities approach. Econ. Soc. 2005, 34, 76–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrera, M. The Boundaries of Welfare: European Integration and the New Spatial Politics of Social Protection, 1st ed.; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ervik, R.; Kildal, N.; Even, N. New Contractualism in European Welfare State Policies, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsdorf, A.; Willem, S. Spatial reconfiguration and problems of governance in urban regions of Europe. An introduction to the belgeo issue on advanced service sectors in European urban regions. Belgeo 2007, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, D. Welfare to work: The local dimension. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2000, 10, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, I. Social assistance regimes: A cluster analysis. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 1997, 11, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsaganis, M.; Ferrera, M.; Capucha, L.; Moreno, L. Mending nets in the South: Anti-poverty policies in Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. Soc. Policy Adm. 2003, 37, 639–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minas, R.; Wright, S.; van Berkel, R. Decentralization and centralization: Governing the activation of social assistance recipients in Europe. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2012, 32, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Berkel, R.; Borghi, V. The governance of activation. Soc. Policy Soc. 2008, 7, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, H. Welfare-partnership dynamics and sustainable development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrera, M. The Southern Model of Welfare in Social Europe. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 1996, 6, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapir, A. Globalization and the reform of European Social Models. J. Common Mark. Stud. 2006, 44, 369–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. Europa na era Global; Sociedade Global, Editora Presença: Lisboa, Portugal, 2007. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Powell, M. Understanding the Mixed Economy of Welfare, 1st ed.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Santana, M.; Moyer, R. Decentralising the Active Welfare State: The relevance of intergovernmental structures in Italy and Spain. J. Soc. Policy 2012, 41, 769–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, B. Denmark: Universal or not so universal welfare state. Soc. Policy Adm. 2004, 38, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hviden, B.; Johansson, H. Citizenship in Nordic Welfare States: Dynamics of Choice, Duties and Participation in a Changing Europe, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daguerre, A. Active Labour Market Policies and Welfare Reform: Europe and US in Comparative Perspective, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, B. Denmark: A Universal Welfare System with Restricted Austerity. In Handbook of European Welfare System, 2nd ed.; Blum, S., Kuhlmann, J., Schubert, K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 129–144. Available online: https://forskning.ruc.dk/en/publications/denmark-a-universal-welfare-system-with-restricted-austerity (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Lindsay, C.; Mailand, M. Different routes, common directions? Activation policies for young people in Denmark and the UK. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2004, 13, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonoli, G. The Origins of Active Social Policy. Labour Market and Childcare Policies in a Comparative Perspective, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Borosch, N.; Kuhlmann, J.; Blum, S. Opening opportunities and risks? Retrenchment, activation and targeting as main trends of recent welfare state reforms across Europe. In Challenges to European Welfare Systems; Schubert, K., de Villota, P., Kuhlmann, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 769–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzel, S. The local dimension of active inclusion policy. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2012, 22, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandford, M. Devolution to Local Government in England; Briefing Paper No. 07029; House of Commons Library: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn07029/ (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- Vampa, D. Comparative Territorial Politics: The Regional Politics of Welfare in Italy, Spain and Great Britain, 1st ed.; Palgrave: Millan, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereirinha, J.; Branco, F.; Pereira, E.; Amaro, M. The guaranteed minimum income in Portugal: A universal safety net under political and financial pressure. Soc. Policy Adm. 2020, 54, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamessini, M. Continuity and change in the Southern European social model. Int. Labour Rev. 2008, 147, 43–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambarloukou, S. Greece after the crisis: Still a south European welfare model? Eur. Soc. 2015, 17, 653–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsaganis, M. Safety nets in (the) crisis: The case of Greece in the 2010s. Soc. Policy Adm. 2019, 54, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellaropous, T.; Kourachanis, N. The social impact of the ‘Social solidarity income’ in Greece: A qualitative interpretation. Soc. Cohes. Dev. 2019, 14, 5–20. Available online: http://www.epeksa.gr/assets/variousFiles/file_1.Sakellaropoulos%20issue27.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Borghi, V.; van Berkel, R. New modes of governance in Italy and the Netherlands: The case of activation policies. Public Adm. 2007, 85, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén, A.M. Citizenship and social policy in democratic Spain: The reformulation of the Francoist Welfare State. South Eur. Soc. Politics 1996, 1, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerven, M.; Vanhercke, B.; Gurocak, S. Policy learning, aid conditionality or domestic politics? The Europeanization of Dutch and Spanish activation policies through the European social fund. J. Eur. Public Policy 2014, 21, 509–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén, A.; Álvarez, S.; Silva, P.A. Redesigning the Spanish and Portuguese welfare states: The impact of accession into European Union. South Eur. Soc. Politics 2003, 8, 231–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera, J.A. The political debate on basic income and welfare reform in Spain. Soc. Policy Soc. 2018, 18, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaza, C.R.; Alaiz, M.M.; Lobato, J.M.; García-Araque, J. Heterogeneidad territorial de las políticas públicas de protección social: El caso de las rentas mínimas de inserción en España. Rev. De Ciência Política 2020, 40, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Segurança Social. Rendimento Social de Inserção; Carência socioeconómica; Instituto de Segurança Social: Sou Cidadão, Portugal, 2020; Available online: http://www.seg-social.pt/rendimento-social-de-insercao (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Branco, F.; Amaro, I. As práticas do serviço social ativo no âmbito das novas tendências da política social: Uma perspetiva portuguesa. Serviço Soc. E Soc. 2011, 108, 656–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, M.; Costa, S. Impactos dos Acordos de Inserção no Desempenho do RSI (Entre 2006 e 2009)—Relatório Final; Centro de Estudos Sobre a Mudança Socioeconómica do Território, ISCTE-IUL: Lisbon, Portugal, 2012; Available online: http://www.seg-social.pt/documents/10152/2995463/Relat%C3%B3rio_RSI_impactos_2006-2012/30e02bce-6383-4973-b5bb-1c91a90a4682 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Saraceno, C. Social assistance policies and decentralization in the countries of southern Europe. Rev. Française Des Aff. Soc. 2006, 5, 97–117. Available online: https://www.cairn.info/revue-francaise-des-affaires-sociales-2006-5-page-097.htm (accessed on 18 December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. Network Society, 1st ed.; Paz e Terra: São Cristovão, Brazil, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Estivill, J. Local Development and Social Protection in Europe. Strategies and Tools against Exclusion and Poverty Program; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; Available online: https://labordoc.ilo.org/discovery/fulldisplay/alma994128933402676/41ILO_INST:41ILO_V2 (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- Van Berkel, R.; Van der Aa, P. The marketization of activation services: A modern panacea? Some lesson from dutch experience. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2005, 15, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oorschot, W. Making the difference in social Europe: Deservingness perceptions among citizens of European welfare states. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2006, 16, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agranoff, R. Local Governments and Their Intergovernmental Networks in Federalizing Spain, 1st ed.; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Third Way: The Renewal of Social Democracy, 1st ed.Polity Press: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

| Review | Description | No of Documents |

|---|---|---|

| Systematic |

| 409 |

| 311 | |

| 303 | |

| 303 | |

| 285 | |

| Narrative |

| |

| ||

| 114 |

| Journal | Publications | 1st Publication | Last Publication | Citations | Cit Score a | SJR b | SNIP c | Discipline(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Journal of European Social Policy | 19 | 1996 | 2021 | 741 | 4.4 | 1.429 | 2.262 | Social sciences and environment |

| Social Policy and Administration | 16 | 1996 | 2020 | 403 | 3.7 | 0.972 | 1.926 | Social sciences |

| Journal of Social Policy | 13 | 2002 | 2018 | 684 | 4.6 | 1.425 | 2.385 | Social sciences |

| International Journal of Social Welfare | 7 | 1996 | 2017 | 108 | 2.1 | 0.664 | 1.67 | Social sciences |

| Social Science and Medicine | 6 | 1991 | 2012 | 306 | 6.1 | 1.913 | 2.331 | Art and humanities, social sciences, health |

| Author | Publications | Citations | Average Citation per Article |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taylor-Gooby, P. | 7 | 617 | 88.4 |

| Hemerijck, A. | 4 | 115 | 28.75 |

| Bonoli, G. | 3 | 165 | 55 |

| Daly, M. | 3 | 234 | 78 |

| Ervik, R. | 3 | 22 | 7.3 |

| Graziano, P.R. | 3 | 50 | 16.7 |

| Greve, B. | 3 | 46 | 15.33 |

| Nilssen, E. | 3 | 16 | 5.3 |

| Kvist, J. | 2 | 103 | 51.5 |

| Dahl, E. | 2 | 69 | 34.5 |

| Van Berkel, J. | 2 | 81 | 40.5 |

| Hofacker, D. | 2 | 87 | 43.5 |

| Principi, A. | 2 | 55 | 27.5 |

| Straubhaar, T. | 2 | 43 | 21.5 |

| Unt, M. | 2 | 70 | 35 |

| Author | Journal | Objectives | No of Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| [12] Nickell, S. & Layard, R. | Handbook of Labor Economics | Explore the suitability and flexibility of the European labor market for the modern global economy. | 542 |

| [13] Taylor-Goody, P. | Oxford Scholarship Online | It provides an approach to the implications of designing social policies at European and national levels, considering new social risks. | 390 |

| [14] Wacquant, L. | European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research | It explains the use of the penal system as an instrument for managing the social insecurity generated in the classes by the neoliberal policies of economic deregulation and reduction of the action of the Social State. | 259 |

| [15] Ebbinghaus, B. | Oxford Scholarship Online | It assesses the impact of the reconfiguration of the various Welfare State regimes, production systems and labor relations. | 218 |

| [16] Pascall & Lewis | Journal of Social Policy | It addresses the implications of policies for gender equality in terms of family, economic and political transformations in Europe. | 208 |

| Author | No. of Co-Citations | No. of Publications |

|---|---|---|

| Esping-Andersen, G. | 212 | 73 |

| Pierson, P. | 116 | 52 |

| Bonoli, G. | 76 | 75 |

| Palier, B. | 68 | 74 |

| Ferrera, M. | 67 | 72 |

| Hemerijck, A. | 66 | 34 |

| Palm, J. | 54 | 6 |

| Giddens, A. | 53 | 51 |

| Quinlan, M. | 49 | 94 |

| Lewis, J. | 48 | 130 |

| Welfare Model | Description | Social Assistance Regime | Use of ICIP and Impact | Description | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social democrat | Decommodification and universal social protection system, on a non-contributory basis, accompanied by active professional integration policies | Residual protection based on citizenship | ICIP with high activation programs and high generosity, with the involvement of social partners. ICIP contributes to reducing unemployment rate | Extension and inclusion/exclusion levels medium and high benefits | Finland, Denmark, and Sweden |

| Conservative corporatist | Robust social protection system, ensures non-universal minimum benefits on a contributory basis and high tax rates | Dual social protection | ICIP with activation programs and average generosity and low involvement of social partners. However ICIP helps to reduce poverty, it needs more intersectoral coordination | Below average length and inclusion/exclusion levels and average benefits | France, Germany, Belgium and Austria |

| Liberal | Commodified, social protection depends on the private sector, more than on State intervention, with high levels of poverty and social inequalities being evident, but on the other hand, high employability rates | Integrated social protection networks | ICIP programs, generosity and impact may vary according to decentralization degree | Extensive, inclusive, and above average benefits | UK and Ireland |

| Mediterranean | Prominence of contributory social protection and old-age pensions, marked by low taxes and informal protection networks, namely the family. In these countries, the cultural dimension and family values that structure civil society are evident, translating into mechanisms of intra-family professional integration and clientelism. | Rudimentary assistance | ICIP with activation programs and low/average generosity. Assistance tends to be decentralized and the impact depends on local resources. | Minimum extension, exclusive and low level of benefits | Portugal, Spain, Italy, and Greece |

| Post-Comunist | Corporatist characteristics and is described as a late effort to develop a welfare state similar to Western Europe, albeit in development and with high levels of inequality. | Dual social protection | ICIP programs are rudimentary, with high poverty rate and high level of unemployment. | Below-average range and inclusion/exclusion levels and average benefits | Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Cyprus, Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic, Croatia, Bulgaria, Romania, Russia and Ukraine |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinto, A.F.; Gonçalves, H. European Tendencies of Territorialization of Income Conditional Policies to Insertion: Systematic and Narrative Review. Societies 2023, 13, 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13080185

Pinto AF, Gonçalves H. European Tendencies of Territorialization of Income Conditional Policies to Insertion: Systematic and Narrative Review. Societies. 2023; 13(8):185. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13080185

Chicago/Turabian StylePinto, Ana Filipa, and Hermínia Gonçalves. 2023. "European Tendencies of Territorialization of Income Conditional Policies to Insertion: Systematic and Narrative Review" Societies 13, no. 8: 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13080185

APA StylePinto, A. F., & Gonçalves, H. (2023). European Tendencies of Territorialization of Income Conditional Policies to Insertion: Systematic and Narrative Review. Societies, 13(8), 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13080185