Abstract

eGovernment brings administration closer to its citizens and entrepreneurs, speeding up, facilitating, and increasing the transparency of administrative actions, consequently saving time and money and increasing efficiency. The study aims to explore the digital divide and digital citizenship in eGovernment usage in Slovakia and Norway according to their national statistics. The study adopted quantitative secondary data from Eurostat’s individual-level database, originating from the questionnaire ‘Information and Communications Technology (ICT) use in households and by individuals’. The analysis was applied to Norwegian and Slovak data from 2021, and the research sample consists of 2145 observations from Norway and 3252 observations from Slovakia. The results show that being a beneficiary of eGovernment services aligns with sociodemographic variables to a lower extent in Norway than in Slovakia. In Slovakia, the usage of the services varies not only according to the education of the user but also according to income, even if an individual has access to the Internet and sufficient skills. Due to the high level of development, and especially the inclusive nature of eGovernment, the Norwegian approach with the implementation of electronic identification (eID), digital mailbox, contact information, Altinn, and public common registers could serve as a benchmark for the further development of public digital services—not only in Slovakia but also for other countries. The conclusion shows that there is less inequity in the possibility to use eGovernment within individual social groups in Norway than in Slovakia. Norway manifests and emplaces strategies to guarantee critical judgment, ensuring the use of digital tools with safety. Slovakia, with lower levels of digital service users, tends to experience higher levels of digital divide which make the situation with eGovernment penetration even more difficult.

1. Introduction

Internet technology, the media, and social networks dominate as a means of communication and have empowered people to participate in a broader range of social activities that are not confined by geographic boundaries [1,2]. Each citizen is perceived as human social capital, and using digital competencies benefits him/herself and society. Harnessing the existence of social capital has implications for economic growth, health, education, and well-being and has the potential to be a good educational tool in relation to citizenship, as well as being important in terms of cultivating citizenship engagement [3]. The era of digital citizenship in a social context requires citizens to be able to interact with each other in different circumstances and contexts. Digital technologies are related to digital inclusion, and along with the rise of the Internet, opportunities to participate in civic, social, and political life have increased [4]. This context has raised the concept called ‘digital citizenship’. Early approaches to digital citizenship were mostly concerned with bridging the digital divide; issues of access, inclusion, and communicative rights and liberties were a priority [5,6]. In the digital and democratic context, citizenship is almost a given, but it does necessitate performing a series of tasks or acts, such as deciphering news feeds or constructing digital identities.

Digital citizens use digital technologies and the Internet appropriately and responsibly to participate in society. A digital citizen can be considered anyone who uses modern digital technologies through digital acts, and who develops their skills and knowledge to use the Internet and digital technologies effectively. These acts include interpreting multiple streams of local and global information and, in the age of datafication, anticipating unknown consequences [7]. The COVID-19 pandemic became a major driving factor in forcing all citizens to increase their online interaction time. This applies to countries with low performance in eGovernment usage (e.g., Slovakia), as well as countries with the highest performance in the use of eGovernment (e.g., Norway). The COVID-19 pandemic ‘helped’ public administration to reduce the digital divide and increased digital citizenship without citizens even realizing it.

To promote the inclusivity of public services, it is important to pay attention to not only the characteristics of the service itself but also the ability of the citizens to benefit from the service. Research on the digital divide has shown that with the increasing maturity of the Internet, the digital world tends to replicate ‘offline’ inequalities resulting from differences in cultural, economic, and social capital [8,9,10]. eGovernment has become an important tool for achieving the European Union’s goal in connection with developing a smarter, knowledge-based greener economy, with the consequence that fast and sustainable growth creates high levels of employment and social progress [11]. The European Commission and other research bodies have conducted studies about selected countries with the aim of explaining or examining factors that influence the degree of usability of eGovernment services; previous studies have included comparisons between Iraq and Finland [12], between Ukraine and the UK, France, and Estonia [13], and between the UK and Algeria [14]. In our study, researchers from Norway and Slovakia—inspired by previously published studies—decided to contribute by exploring the differences in the digital divide and digital citizenship and eGovernment usage between citizens of their native countries.

Although the European Commission [15] strongly supports the digitalization of public services, the level of eGovernment usage differs significantly in the countries of the European Union and the European Economic Area. Moreover, the differences do not exist only at the macro level; the ability to benefit from using digital technologies generally differs among individual social groups and tends to replicate traditional social inequalities. There are differences in eGovernment usage in the countries of the European Union and the European Economic Area, ranging from Iceland (94% of all individuals use certain forms of eGovernment) to Romania (15% usage rate). In Norway, 91%, and in Slovakia, 56% of all individuals use a certain form of eGovernment [16]. Furthermore, the data show that differences on the macro level reflect the uneven use of digital services on an individual level. The countries with low levels of digital service users tend to experience higher levels of digital divide, which makes the situation with eGovernment penetration even more difficult [17].

Digital transformation has been one of the Norwegian government’s priority areas in recent years and has put Norwegian businesses at the forefront of adopting new technologies and using them to achieve organizational goals. The main reason why Norway scores so well is that Norwegians are considered to be early adopters of digital technologies and have very good digital skills. There is very good coverage of the Internet, a good mobile infrastructure, and good connectivity [18]. Although Slovakia (5,431,235 citizens) and Norway (5,475,240 citizens) had a similar population in 2022, the Nordic country is one of the richest countries in the world and has regularly invested in its public ICT infrastructure over the years [19,20]. In addition, part of the roots of digital transformation in Norway is closely linked to the Scandinavian or Nordic model, which is generally characterized by a strong welfare state, a system based on trust between authorities and citizens, and a collaborative three-party approach involving the state, business organizations, and employee organizations (especially trade unions). Norway has also been successful in many areas in its efforts to digitalize public services, with public authorities and municipalities increasingly offering digital services, and their use growing dramatically. Norway has very good results in Internet literacy, broadband, and the digitalization of business and services in state and public administration and achieves above-average results in the digital skills of the population [21]. We have chosen to research Norway and Slovakia because of their different use of ICT, the differences in the digital world, and the fact that they are both located on the same continent and are partners in the EEA agreement. The analysis of the digital divide in Slovakia is an output of the project VEGA No. 1/0668/20 ‘Digital Inequality and Digital Exclusion as a Challenge for Human Resources Management’.

While a growing body of literature suggests that adults’ digital skills are needed to enable both individuals and organizations to make the most of the digital workplace, empirical understanding of their impact on technology adoption and performance is currently limited. This study aims to explore the digital divide and digital citizenship in eGovernment usage with a focus on the differences within various social groups in Slovakia and Norway, according to national statistics.

The Conceptual Framework

The relationship between people and the nation-state is traditionally conceptualized as citizenship. Citizenship represents a certain way of thinking and looking at social problems and a set of practices that constitute a change in the relationship between citizens and the nation-state. A citizen is also able to impact the development of the way society is governed [22]. State citizenship and democratic citizenship are not the same and may offer different levels of legal and formal rights. In a practical matter, a particular person can only exercise these rights to varying degrees [23]. A person may, for example, be a Norwegian citizen and hold all the formal rights that come with Norwegian nationality but still have difficulty functioning as a full member or citizen of Norwegian society. There are many possible causes for such a situation to occur in the process of adaptation to a multicultural country, but the most common causes are poverty, serious or chronic illness and disability, and language problems [24]. The opportunities to participate in civic, social, and political life have increased with the rise of the Internet. The idea of citizenship being digital, for example, carries within it the principles of scale, immediacy, and information control that are all immanent in the idea of big data and which exert a change in understanding [4]. Digital citizenship can therefore be defined as simply ‘the right to participate in society online’, thus increasing the democratic aspects of participation [25]. Early approaches to digital citizenship were mostly concerned with bridging the digital divide where issues of access, inclusion, and communicative rights and liberties were a priority [26,27]. The discussion of digital citizenship is described as a contextual approach, which understands digital citizenship as a context-dependent and fluid concept. In this approach, digital citizenship ‘encompasses very diverse experiences of what it is like to live as a citizen in the digital age’ [28,29]. Digital citizenship is not just about the obligations of the state or the responsibilities of the citizen, but also how digital tools and technologies facilitate new forms of participation. Digital platforms now offer more opportunities to be an informed and engaged citizen, as well as civic participation with a significant impact on democratic politics.

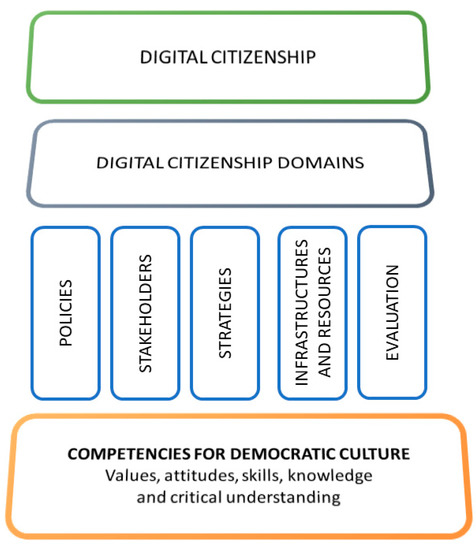

Digital citizenship encompasses a wide range of activities in a constantly evolving digital environment, which means that acquiring the necessary competencies is a lifelong process. The Council of Europe’s foundational competencies for democratic culture provides an overview of the competencies that citizens need to acquire if they are to participate effectively in a culture of democracy [30], and the conceptual model for digital citizenship (Figure 1) builds on this.

Figure 1.

The Council of Europe Model of Digital Citizenship [30].

As depicted in the model above, the five pillars provide the basic framework structure that supports the entire digital citizenship development process. Digital citizenship and engagement involve a wide range of activities, from creating, consuming, sharing, playing, and socializing to investigating, communicating, learning, and working. Competent digital citizens can respond to new and everyday challenges related to learning, work, employability, leisure inclusion, and participation in society, respecting human rights and intercultural differences. In the above model, which is illustrated in Figure 1, the basis of digital citizenship consists of competencies for a democratic culture. The five constructs emerge as essential for the development of digital citizenship practices. Policies and evaluation represent the two framework pillars of the model. In fact, progress in education-related fields is largely shaped by policies and best practices that can be analyzed and possibly replicated through effective monitoring and evaluation methodologies. Stakeholders include various factors such as the education system, public administration, health, industry, and policymakers who have an active interest and responsibility in promoting digital citizenship. The strategies serve as guiding frameworks that govern the activities and initiatives carried out to promote and develop digital citizenship. Strategies are at the heart of the model and serve as a focal point and key indicator of the level of development of digital citizenship education in each country. Infrastructure and resources provide the necessary conditions and technical and other learning resources to support the ongoing development of digital citizenship activities [30] (p. 12).

2. Materials and Methods

This study has a quantitative descriptive design. This type of design aims to report a population, situation, or phenomenon accurately and systematically; it emphasizes the collection of objective data to assess a social phenomenon [31]. Additionally, quantitative secondary data were used in this research to provide a deepening in the analysis of the eGovernment in both countries and to give the possibility of providing better statistical data interpretation and correlation. The source of the data is Eurostat’s individual-level database, originating from the questionnaire ‘ICT use in households and by individuals’. The data come from a questionnaire survey that has been performed annually since 2002, and they systematically map any trends in the penetration of ICT into the everyday life of EU citizens. The analysis was applied to Norwegian and Slovak data from 2021, which consist of 2145 observations from Norway and 3252 observations from Slovakia. The data are weighted to consider the difference in sample size in relation to the populations of the two countries.

2.1. Data Collection

The questionnaire available from Eurostat contains six modules: mapping access to ICT, use of the Internet (frequency, purpose), use of eGovernment, use of e-commerce, digital skills, and privacy and protection of personal data. In addition to this, it solicits information from the user regarding a variety of sociodemographic indicators of the individual and the household. The actual usage of eGovernment is represented by three variables in the survey. The respondents answer the question of whether they contacted or interacted with public authorities or public services over the Internet for private purposes in the last 12 months for the following three activities: obtaining information from websites or apps, downloading/printing official forms, and submitting completed forms online.

The measurement of the use of digital skills as a composite indicator is based on the user’s activity in five specific areas: information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, digital content creation, safety, and problem solving.

For the purposes of anonymization, the variable describing the age was provided using categories of a 10-year range interval, which was recorded as a dummy variable describing individuals under and over 55 years old. To measure education, the ISCED classification was used. ‘Lower secondary and below’ refers to the ISCED categories 0–2, ‘Upper secondary’ indicates categories 3 and 4, and ‘Tertiary’ includes categories 5–8. The variables Sex and Income quantile are self-explanatory.

2.2. Data Analysis

The purpose of the analysis was to ascertain the inclusivity of eGovernment usage in Norway and in Slovakia; to find out if the probability of using these digital services differs with the sociodemographic background of an individual; and to take into account an individual’s digital skills and other variables, particularly regarding the age, education, gender, and income of the user.

We hypothesize that if an individual has access to the Internet and possesses at least basic digital skills, the probability of him/her benefitting from eGovernment use is not significantly associated with socioeconomic variables. To put it in a different way, eGovernment use does not vary within various social groups given similar digital skills. To examine the structure of the eGovernment users in Norway and in Slovakia, we ran a logistic regression using Stata 17 software, with the activities of eGovernment usage as dependent variables and a set of socioeconomic indicators as independent variables, separately for each activity and both countries. To be able to compare the countries, we calculated the average marginal effect for independent variables, which describes the difference in the probability of using eGovernment between the category in question and the base category.

This study used a method regression analysis, the study of relationships between two or more variables usually conducted to learn whether any relationship between two or more variables exists, to understand the nature of the relationship between the variables, and to predict a variable given the value of others [32].

3. Results

Digital technologies have changed the requirements for accessing information. Access to information is easier/cheaper/more available in terms of time and space, no matter how demanding in terms of assets and skills. Although the process of digitalization itself started later in Slovakia due to the transition to a market economy in early 1990, it is catching up rapidly. Table 1 describes the level of connection, Internet usage, and digital skills in Norway and in Slovakia.

Table 1.

Internet usage and digital skills in Norway and Slovakia—descriptive statistics.

The data show that digital technologies are available for most of the population in both Norway and Slovakia. In Slovakia, there is still room to improve the infrastructure and access to technology, as more than one-tenth of households lack connection to the Internet, and approximately the same portion of individuals have not used the Internet within three months. Interaction with public authorities online often requires a whole set of skills as it requires management of information, communication, creation of documents, awareness about the safety of one’s interaction mainly in terms of personal data, and a user who is relatively familiar with recent technology. The distribution of digital skills in both populations is shown in Table 1. We can observe in relation to overall digital skills (composite indicator) that, despite the Internet being used by most of the population, more than 37% of Slovaks lack basic digital skills, as compared to approximately 20% of Norwegians.

With regard to the structure of digital skills connected with the areas of information and data literacy, communication, and problem solving, more than 90% of users have a minimum of basic digital skills in both countries. What is noteworthy is that more than 12% of Norwegians and 28% of Slovaks lack basic skills connected to safety when using the Internet.

The data connected with the actual usage of the eGovernment (Table 2) describes two modes of possible interaction between citizens and public authorities; informative (obtaining information and materials) and transactional (complex interaction—submitting forms online).

Table 2.

eGovernment usage (percentage of Internet users).

Although the gap between Norway and Slovakia is relatively small in terms of access to technology and available skills, this is not translated into real-life benefits—i.e., dealing with one’s administrative matters efficiently online. While more than two-thirds of Norwegians have used digital technologies to interact with public entities, this proportion is less than one-third in Slovakia in terms of downloading and submitting completed forms.

To offer a more detailed view of eGovernment usage in both countries, we ran a logistic regression with activities of eGovernment usage as dependent variables and socioeconomic factors as independent variables (namely variables indicating age over 55, sex, type of education, and income quintile). The regression answers the question, considering access and usage of the Internet, of the factors which increase/decrease the probability of using the services of eGovernment.

In Norway (Table 3) the most important characteristic in relation to informative use (obtaining information and downloading forms), which correlates with the low probability of usage of eGovernment, was a lack of digital skills followed by a lower level of education. For transactional use (submitting complete forms), the order is the opposite—low education predicts a lower probability of using eGovernment to a higher extent than digital skills. From the point of view of equality, it is important that belonging to any income quintile is not associated with the probability of benefiting from any activity of eGovernment. Weak correlation was also observed between the age being over 55 and a low probability of obtaining information and submitting forms. In addition, women have a higher probability of obtaining information online than men.

Table 3.

Regression results for Norway.

The situation is different in Slovakia (Table 4). Possession of digital skills is associated with the probability of using eGovernment more intensively (except for downloading forms). Education and income categories are also significant factors in the probability of using eGovernment services. The effect of age is mixed—it is significant for obtaining information and submitting complete forms, but not significant for downloading forms. In comparison to the possession of digital skills and education, the effect of age does not carry so much significance.

Table 4.

Regression results for Slovakia.

Based on the analysis, we can conclude that being a beneficiary of eGovernment services aligns with sociodemographic variables to a lower extent in Norway than in Slovakia. In Slovakia, the usage of the services varies based not only on an individual’s education but also based on his/her income, even if an individual has access to the Internet and sufficient skills.

4. Discussion

eGovernment has several phases of interaction and service delivery; some types have four different phases of interaction, and some may have five phases. There is a large degree of agreement on the initial three phases: (i) informational (in which information is directly delivered to citizens, such as through downloading reports and brochures from websites); (ii) interactional (where citizens have the ability to ask questions, make complaints, or search for information sources); and (iii) transactional (where users are able to complete all steps of a complex interaction online). One or two of the following phases can also be considered participatory (where citizens participate in shaping policies): transformational or integrated (where the internal organization of government is adapted to the needs of providing services in an integrated, client-centric way), and connected (combining features of both) [33]. In addition, eGovernment interactions are sometimes classified as government-to-citizens or G2C (such as when citizens file income tax declarations), government-to-business or G2B (such as when businesses seek permits), or government-to-government or G2G (as when different branches or levels of government exchange information) [34]. Norway is a digitally advanced market, and compared to Slovakia, a significant proportion of the population uses the Internet daily. Several service industries, such as banking, tourism, and electronic healthcare, have undergone many procedures in the digitalization of their business processes, and thanks to this transformation, their activities have become more efficient. Norway has also been successful in its efforts to digitalize public services, with public authorities and municipalities increasingly offering digital services and their use growing dramatically. The Norwegian approach to the implementation of eID, digital mailbox, contact information, Altinn, and public common registers could serve as a benchmark for further development of public digital services [35].

All digital citizenship development initiatives are defined by contextual, information, and organizational principles [32,35]. Within the contextual principle, most of the citizens in both selected countries have access to digital technology, and most of them have basic functional and digital literacy skills. These are the basic predictors of the inclusion of a digital citizen in a digital society. Both countries provide a secure technical infrastructure that enables citizens of all ages to have sufficient confidence and trust to digitally engage in online community activities. In particular, this precondition completes the first level of the guiding principles for digital citizenship. Access, inclusion, and increasing education in functional and digital literacy are part of a never-ending process within the social frameworks. Reliable information sources are essential for positive active communication in community life, in addition to a knowledge of rights and responsibilities. According to the Digital Citizenship Education Handbook [30] (p. 18), without sources of reliable information, digital citizenship can morph into extremism, discourage participation, and even prevent certain sectors of the population from practicing their digital citizenship rights. While schools and families play an important role in fostering discernment through critical thinking and educational practices, digital platforms and mobile providers have a large part to play too in ensuring the reliability of information sources. Participation skills such as critical thinking and oral and written expression skills are significant aspects of digital citizenship, and the development of these attributes is necessary in both countries. Organizational principles relating to ‘living digital citizenship’ refer to the skills and tools used to interact, disseminate, and receive information at a personal and societal level; these principles require flexible thinking and problem solving as well as communication. The last and most important principle is citizenship opportunity. This is the ultimate guiding principle, without which digital citizens are unable to hone their citizenship skills or exercise their rights and responsibilities [30] (p. 19).

Therefore, digital competence is not only familiarity with the usage of digital technologies, but it also involves skills connected to the evaluation and responsible use of information, as stressed by The Council of the European Union [36]. Digital competence includes information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, media literacy, digital content creation (including programming), safety (including digital well-being and competencies related to cybersecurity), intellectual property, problem solving, and critical thinking [37]. In the present study, we consider the eGovernment system as the infrastructure pillar. To support digital citizenship, it should represent a tool which enables the citizens to participate. As in the case of democratic citizenship, the right to participate is ensured for anybody, although certain individuals may experience difficulties exercising their rights. Previous research showed that exclusion or weakened ability to participate in certain realms of the ‘offline’ world are good predictors of lack of participation in the digital world [38,39]. The studies which focused specifically on eGovernment use showed that possession of digital skills is important, but only as a predictor of eGovernment usage. Several studies show a correlation between low eGovernment usage and low education and income [40,41,42]. However, the research also points out other barriers to eGovernment usage: age, low levels of trust, or being a non-native speaker of the official language [43,44,45]. The goal of pointing out the existence of the digital divide is to highlight the fact that these differences in usage decrease very slowly over time and need to be addressed by the government through a targeted series of actions, e.g., by redesigning the services or training vulnerable groups.

Almost every citizen in Norway uses online banking, pays their bills online, communicates with public institutions through digital channels such as platforms, chatbots, and meeting-based apps, files their tax returns electronically, and exchanges money through mobile payment apps. A private sector and industry perspective would provide a similar picture; companies are investing significantly in digital platforms for collaboration, virtualization, and data sharing and analysis. In addition, Norway has been working on a strategy called The Skills Reform—Lifelong Learning to prevent digital exclusion, which increases the number of citizens able to be included in digital citizenship [46]. Norway, together with the other Nordic countries, regularly ranks at the top of the digitalization rankings in Europe [15,16]. Table 1, with descriptive statistics related to the countries studied, shows that Norway has a high rate of data literacy at more than 98%; even in this scenario, the government is actively working to include parts of the population that might not adapt so well to a digital citizenship reality.

Although the regression analysis shows that the gap between Norway and Slovakia is relatively small in terms of access to technology and available skills, this reality is not always translated into real-life benefits. To achieve the optimization of public administration with the active involvement of citizens in the implementation of changes, modifications at the national level are necessary. Each of the EU and EEC countries can introduce measures such as targeted education, the dissemination of information through various channels among the citizens of the country, and the digitalization of society with the aim of saving public expense and improving digital skills for all age groups. To successfully face the challenges of digital transformation, it is necessary to improve the digital skills of a whole population, from primary school pupils to adults. In order to meet such a challenge, the Slovak government established a new strategy entitled ‘The 2030 Digital Transformation Strategy for Slovakia’, which aims to transform Slovakia into a successful digital country and economy. The measures expounded upon by this document are in accordance with the Norwegian strategy to digitally include populations that would otherwise experience digital citizenship as challenging [46]. This strategy is a framework for all the different sections of government, defining the policy and particular priorities of Slovakia under the influence of innovative technologies and global megatrends of the digital era.

Slovakia needs to continue its efforts to improve and extend digital public services. Although progress has been made, the country remains below the EU average. In December 2021, the Slovak Government approved a new strategic document, entitled ‘National Concept of Informatisation of Public Administration for 2021–2026’ [47]. The strategy outlines a vision for more reliable and user-friendly digital public services, including eHealth, and is explicitly aligned with the European Commission’s ‘Digital Decade’s Policy Programme 2030’ objectives in this area. The necessity to increase the digital competencies of people in Slovakia is also emphasized in several national strategic documents; the ‘Strategy and Action Plan for Improving Slovakia’s Position in the DESI by 2025’ and the ‘Action Plan for Slovakia’s Digital Transformation 2019–2022’ outline concrete measures to help the country make progress in the human capital dimension, whereas the ‘2030 Digitalisation Agenda for Education’ emphasizes the importance of supporting the digital competencies of children, students, and educators from pre-primary to tertiary education.

The Slovak government must continue with its effort to establish a new stand-alone digital skills strategy covering all population groups (young people, employees, jobseekers, older people, ICT professionals, etc.) to help Slovakia meet the Digital Decade target; namely, 80% of people should have the minimum of basic digital skills by 2030. In 2021, the government adopted a new lifelong learning strategy which aims to make the Slovak education system more flexible, offer new opportunities for adult and continuing education, and better respond to labor market needs. The strategy includes the introduction of micro-qualifications to help the workforce broaden or reorient their qualifications, and especially to adapt to digital transformation. The strategy also sets out a roadmap for the creation of new digital skills [47].

In Norway, the strategy for digital competency is based on the premise that users should have the ability to use digital services with digital judgment. This way, the main goal of the strategy is ‘to counteract digital exclusion by ensuring that all citizens have sufficient digital competence to be able to participate in society on an equal basis’ [46]. Differently from Slovakia, the Norwegian government aims to prevent digital exclusion in all groups by facilitating extra assistance for those citizens without enough digital competence. It also aims to instill digital literacy throughout the population.

Compared to Norway, Slovakia ranks relatively low on the UN’s annual eGovernment Development Index (EGDI). In 2022, it ranked 47th, while Norway ranked 17th [48]. One of the challenges for Slovakia is the creation and development of a central point of access to public administration services and information, as inspired by the Norwegian model. One of the trends supporting the new concept of eGovernment is the migration of public portals. The functioning of integrated portals is made possible by inter-ministerial eGovernance systems that manage, among other things, the backends of such portals. Their main advantage is the sharing of a single state-of-the-art platform that presents a variety of different information in a clear form, organized either by topic, lifecycle, or another preferred method. By using single sign-on technologies, such a portal can also become a ‘single point of contact’ for all eGovernment services. The citizen wants interaction with public administration not to be a burden, but rather to be able to handle everything they need easily and efficiently. The citizen can be duly informed about the progress of his/her proceedings and their results through all available channels if he/she so requests. Countries such as the United States, South Korea, Australia, Norway, and Denmark are already close to such a solution. This new service concept will change the relationship between citizens and public administrations and ensure the provision of better services at a lower overall cost, thanks to the necessity of only minimal bureaucracy.

One of the problems of this system is that users do not trust eGovernment services and have doubts about ensuring the protection of their data, as well as the security of their access. Trust is much more difficult to build in an online space, where the competence, honesty, and conscientiousness of the various interlocutors are more difficult to assess than in face-to-face interaction. One of the solutions here is following the premisses of digital judgment that Norway works to implement, namely giving the citizen the tools to think critically and make conscious decisions about data protection, security of the information, and critical understanding of the media [46].

A high level of e-services for citizens and businesses improves the quality of life and the competitiveness of the economy. The availability of eGovernment services across countries strongly supports the use of the Internet and motivates citizens to acquire ICT skills to reap the full benefits provided by public administration. The main task of public administration is to serve citizens as much and as efficiently as possible with the goal of saving public funds, which can be further invested in the development of electronic healthcare or education.

5. Conclusions

The use of eGovernment has a direct impact on the development of a democratic culture with values, attitudes, skills, and critical understanding as a basis for the effective practice of digital citizenship. eGovernment reflects how a country uses information technology to support access and inclusion of its citizens. The provision of online services, ICT connectivity, and human capacities are important dimensions of eGovernment. The main findings from this study indicate that there is less inequity in the possibility of using eGovernment within individual social groups in Norway than in Slovakia. Even with the already high rates of adherence to the use of digital tools, Norway strives to include every one of its citizens in the digital citizenship era, and its strategy places high importance on digital literacy. In addition, Norway manifests and emplaces strategies to guarantee critical judgment ensuring the use of digital tools with safety.

In Slovakia, the usage of the services varies based not only on a person’s education but also on their income, even if an individual has access to the Internet and sufficient digital skills. These facts create challenges when implementing digital citizenship in the country; however, increasing access and usage of digital citizenship and digital literacy can guarantee long-term stability and high standards in the implementation process. These findings give researchers the opportunity to take a closer look at the importance of improving education with a focus on the use of eGovernment, especially in Slovakia, paying special attention to low-income groups. One challenge for politicians, educators, and other eGovernment platform creators is how to prioritize young people’s ability to develop a democratic culture through a digital citizenship approach in the context of their online interactions. Employers could play their part in increasing digital skills by preparing e-learning courses for their employees with the goal of increasing knowledge and critical understanding through online use. Another key consideration is how the findings of this study can inform revised digital citizenship curricula and learning resources in respect of formal education.

Several limitations should be considered in this study. The study is designed as a descriptive study with the use of regression analysis of existing data from Eurostat’s individual-level database; thus, a deep correlational data analysis was not emplaced. This means that the current study presents and opens a discussion about eGovernment in Norway and Slovakia but does not seek specific solutions and does not present deep comparisons between the two countries. In addition, from a qualitative perspective, the authors point out that a wider range of documents (e.g., research articles or national annual reports) and own data collection may provide additional insight on eGovernment implications for practice and the impact of digital citizenship. We believe that our research contains meaningful results and fills a gap in the field, but the limitations present suggest there are implications for future studies and opportunities for further research in this area. It would be an exciting path to explore the gap between the availability of eGovernment services and their actual uptake and use. Aspects of future research may take the form of interviews with the various target groups of eGovernment services, perhaps focusing on the barriers and possibilities of eGovernment use and ways to build better trust and increase online safety in the digital society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T. and A.S.; methodology, A.V. and M.T.; software, A.V.; validation, V.N.F., A.S. and M.T.; formal analysis, A.V. and A.S.; investigation, A.V.; resources, M.T. and V.N.F.; data curation, A.S., A.V. and V.N.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T. and A.V.; writing—review and editing, V.N.F., A.S. and A.V.; visualization, M.T.; supervision, M.T.; project administration, M.T. and A.S.; funding acquisition, V.N.F. and M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research paper originated as a partial outcome of a research project BIN SGS02_2021_002: University Enhancing the Smart Active Aging (UESAA), supported by EEA and Norway Grants. The APC and proofreading service were paid for by this project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, L.L.; Mirpuri, S.; Rao, N.; Law, N. Conceptualization and measurement of digital citizenship across disciplines. Educ. Res. Rev. 2021, 33, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenkova, V.; Lendzhova, V. Digital Citizenship and Digital Literacy in the Conditions of Social Crisis. Computers 2021, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanda, A.Y.; Muchtarom, M.; Rusnaini, R. The Formation of New Social Capital and Civic Engagement in Society 5.0 Viewed from Digital Citizenship Education. In Proceedings of the ICOPE 2020, Bandar Lampung, Indonesia, 16–17 October 2020; Available online: http://eprints.eudl.eu/id/eprint/2604/ (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Pangrazio, L.; Sefton-Green, J. Digital Rights, Digital Citizenship and Digital Literacy: What’s the Difference? J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 2021, 10, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam Ibrahim, O.; Dzang Alhassan, M. Bridging the global digital divide through digital inclusion: The role of ICT access and ICT use. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2021, 15, 580–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, Ł.; Eliseo, M.A.; Costas, V.; Sánchez, G.; Silveira, I.F.; Barros, M.-J.; Amado-Salvatie, H.R.; Oyelere, S.S. Digital divide in Latin America and Europe: Main characteristics in selected countries. In Proceedings of the 2019 14th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Coimbra, Portugal, 19–22 June 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Close, S. Being Digital Citizens, by Engin Isin and Evelyn Ruppert. J. Cult. Econ. 2016, 9, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deursen, A.; van Dijk, J. The digital divide shifts to differences in usage. New Media Soc. 2014, 16, 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.; Cotten, S.R.; Ono, H.; Quan-Haase, A.; Mesch, G.; Chen, W.; Schulz, J.; Hale, T.M.; Stern, M.J. Digital inequalities and why they matter. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2015, 18, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerder, A.; van Deursen, A.; van Dijk, J. Determinants of Internet skills, uses and outcomes. A systematic review of the second- and third-level digital divide. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1607–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Europe 2020. A European Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth. 2010. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eu2020/pdf/COMPLET%20EN%20BARROSO%20%20%20007%20-%20Europe%202020%20-%20EN%20version.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Abubakr, M.; Kaya, T. A Comparison of E-Government Systems Between Developed and Developing Countries: Selective Insights from Iraq and Finland. Int. J. Electron. Gov. Res. (IJEGR) 2021, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliychenko, I.; Ditkovska, M.; Shabardina, Y.; Lashuk, O.; Zhovtok, V. Improvement of e-government in Ukraine based on the experience of developed countries. Int. J. Electron. Gov. 2023, 15, 4–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaida, M. e-Govenrment Usability Evaluation: A Comparison between Algeria and the UK. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Decision (EU) 2022/2481 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 Establishing the Digital Decade Policy Programme 2030 (Text with EEA Relevance); Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. E-Government Activities of Individuals via Websites [Data Set]. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ISOC_CIEGI_AC/settings_1/table?lang=en (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Kuráková, I.; Vallušová, A.; Marasová, J. Measuring the digital divide in the V4 countries using the Digital Divide Index. Ekon. A Spoločnosť 2021, 22, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmiggiani, E.; Mikalef, P. The Case of Norway and Digital Transformation over the Years. In Digital Transformation in Norwegian Enterprises; Mikalef, P., Parmiggiani, E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. Demographic and Social Statistics. Population and Migration. Stock of Population in the Slovak Republic on 30 June 2022; Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Norway. Population Count. Population in Norway 3rd Quarter 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/folketall/statistikk/befolkning (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- European Commission. Norway in the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2022. Norway. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/desi-norway (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Payne, M. Modern Social Work Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sépulchre, M. Disability and Citizenship Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossberger, K.; Tolbert, C.; McNeal, R. Digital Citizenship: The Internet, Society and Participation; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley, M.; Thrane, L.; Shulman, S.; Lang, E.; Beisser, S.; Larson, T.; Mutiti, J. Digital citizenship: Parameters of the digital divide. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2004, 22, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrane, L.E.; II, M.C.S.; Shulman, S.W.; Beisser, S.R.; Larson, T.B. E-political empowerment: Age effects or attitudinal barriers. J. E-Gov. 2004, 1, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørring, L.; Valentim, A.; Porten-Cheé, P. Mapping a Changing Field. A Literature Review on Digital Citizenship. Digit. Cult. Soc. 2019, 4, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jæger, B. Digital Citizenship—A Review of the Academic Literature. Dms Der Mod. Staat Z. Für Public Policy Recht Und Manag. 2021, 14, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.; Akyeşilmen, N.; Raulin-Serrier, P.; Santos Silva, B. Implementing Council of Europe Recommendation CM/Rec (2019)10 on Digital Citizenship Education: A Policy Development Guide. Council of Europe. 2022. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/0900001680a6afb7 (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Richardson, J.; Milovidov, E. Digital Citizenship Education Handbook; Council of Europe Publishing: Strasbourg, France, 2019; Available online: https://rm.coe.int/digital-citizenship-education-handbook/168093586f (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Bhattacharya, A.; Chetty, P. A Comparison of Descriptive Research and Experimental Research. 2020. Project Guru. Available online: https://www.projectguru.in/a-comparison-of-descriptive-research-and-experimental-research/ (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Ranganathan, S.; Gribskov, M.; Nakai, K.; Schonbach, C.; Cannataro, M. Encyclopedia of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 978-0-12-811414-8. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, R.; eGovernment. Using technology to improve public services and democratic participation. EPRS Eur. Parliam. Res. Serv. 2015. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2861/150280 (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Hoti, L.; Dermaku, K.; Klaiqi, S.; Dermaku, H. Protection and Exchange of Personal Data on the Web in the Registry of Civil Status. Emerg. Sci. J. 2023, 7, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwegian Ministries. Digital Agenda Norway. Digitizing Public Sector Services Norwegian eGovernment Program. 2012. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/fad/kampanje/dan/regjeringensdigitaliseringsprogram/digit_prg_eng.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- The Council of the European Union. Council Recommendation on Key Competencies for Lifelong Learning. 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legalcontent/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018H0604(01&from=EN (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Porat, E.B.; Barak, I. Measuring digital literacies: Junior high-school students’ perceived competencies versus actual performance. Comput. Educ. 2018, 126, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragnedda, M.; Ruiu, M.L.; Addeo, F. The self-reinforcing effect of digital and social exclusion: The inequality loop. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 72, 101852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranchordás, S. The Digitization of Government and Digital Exclusion: Setting the Scene. In The Rule of Law in Cyberspace. Law, Governance and Technology Series; Blanco de Morais, C., Ferreira Mendes, G., Vesting, T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodel, M.; Aguirre, F. Digital inequalities’ impact on progressive stages of e-government development. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Galway, Ireland, 4–6 April 2018; pp. 459–463. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Morote, R.; Pontones-Rosa, C.; Núñez-Chicharro, M. The effects of e-government evaluation, trust and the digital divide in the levels of e-government use in European countries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 154, 119973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chohan, S.R.; Hu, G. Strengthening digital inclusion through e-government: Cohesive ICT training programs to intensify digital competency. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2020, 28, 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botrić, V.; Božić, L. The digital divide and E-government in European economies. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2021, 34, 2935–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazier, D.; Harvey, M. eGovernment and the digital divide: A study of english-as-a-second-language users’ information behaviour. In Proceedings of the Advances in Information Retrieval: 39th European Conference on IR Research, ECIR 2017, Aberdeen, UK, 8–13 April 2017; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 266–277. [Google Scholar]

- Seljan, S.; Miloloža, I.; Pejić Bach, M. e-Government in European countries: Gender and ageing digital divide. Interdiscip. Manag. Res. 2020, 16, 1563–1584. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation. Digital Throughout Life National Strategy to Improve Digital Participation and Competence in the Population. 2022. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/8f8751780e9749bfa8946526b51f10f4/digital_throughout_life.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Ministry of Investments, Regional Development and Informatization of the Slovak Republic. National Concept of Informatisation of Public Administration for 2021–2026. 2021. Available online: https://www.mirri.gov.sk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Narodna-koncepcia-informatizacie-verejnej-spravy-2021.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- UN E-Government Knowledgebase. E-Government Development Index (EGDI). 2023. Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/About/Overview/-E-Government-Development-Index (accessed on 22 October 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).