Abstract

What can be the contribution of oral history to the interpretation of tangible cultural assets? Starting from this conceptual question, this article focuses on the case study of the experiences Second World War in Naples bomb shelters, recently included within the Underground Built Heritage (UBH) class. The hypothesis of the research is that bomb shelters are very significant elements in the subsoil of Naples but that, due to the lack of distinctive elements and dedicated storytelling, they are only partially exploited in the context of urban parks or generic itineraries Naples’s subsoil. The thesis of the research is that the memories of those children that took refuge there during World War II (WWII), which were collected with the adoption of the oral history methodology, can integrate their value as elements of local cultural heritage and eventually support their interpretation for the benefit of the new generations. The methodology adopted was the collection, via structured and unstructured interviews, of the direct testimonies of those who took refuge in Naples’ underground during the alarms. Twenty-three interviews were carried out, and all the issues introduced have been classified according to the various themes addressed during the narration in order to allow the reconstruction of dedicated storytelling in the future. The research was carried out immediately after the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, an event that claimed many victims belonging to the generation of our witnesses, whose memories were at risk of being lost forever.

1. Introduction

How can historical research support the enhancement processes of selected elements of local cultural heritage from wars and conflicts [1,2,3]?

Starting from this question, this research aims at establishing a “connection” between the narration of World War II (WWII) via the adoption of the oral history methodology [4] and the definition of “actions” with regard to the enhancement of WWII bomb shelters in the city of Naples.

The main goal is to test in Naples an experimental approach for the transformation of private memories into public heritage [5] via the implementation of the archaeological value of WWII shelters for the benefit of new generations, which no longer have access to direct witnesses who could describe historical uses. In this perspective, the site-based approach is addressed not only for the reconstruction of the biography of places [6] but also for the consolidation of the sense of place connected to this architecture [7], for educational purposes [8], and for the witnesses’ adoption as access doors to more general information about WWII.

We have to say that WWII bomb shelters, which all resulted from the transformation of pre-existent historical caves, are very common elements in the underground scenario of Naples. Despite this, and even though they have been recently included within the Underground Built Heritage (UBH) class [9] and are currently part of several enhancement projects, they are still unexploited with respect to their potential for narrative.

On the basis of these premises, the hypothesis of the research is that WWII Neapolitan bomb shelters, which have become significant as a result of their inclusion within the class of heritage from wars and conflicts, are not fully utilized yet.

The focus of the thesis of this research is that the memories of those children who took refuge there during the WWII bombings that were collected with the adoption of the oral history methodology can activate the reconstruction of their identity and integrate their significance within the local historical heritage.

The thesis of the research is that the elaboration of the outputs of the interviews can eventually support the interpretation [10,11,12,13] of WWII in Naples within dedicated enhancement projects.

The research has been carried out according to the following six phases:

- The adoption of the UBH theoretical approach to Naples WWII shelters: analyses were conducted on original functions, use during the conflict, post-war reuses and contemporary function;

- The selection and analysis of case studies of former shelters that are included in touristic routes, located in urban parks or reused in various areas of the city;

- The selection of the sample for the interviews;

- Interviews with people who took cover in the shelters during the WWII;

- The analysis and classification of the results;

- A final hypothesis of the adoption of the results as sources for the interpretation of WWII shelters in the reconstruction of the correspondent storytelling of selected case studies.

The research was stimulated by the publication of “Guerra Totale” from Gabriella Gribaudi [14], who successfully introduced the adoption of oral history sources in the city of Naples during WWII. From then on, this theoretical approach has been adopted by several scholars [15,16] in the reconstruction of the so-called minor history [17] of the city.

The interest towards WWII shelters dates back to the activities of the multidisciplinary project “Undergrounds in Naples” (2007/2009) supported by the Province of Naples, Campania Region, Metropolitana di Napoli spa, Tecnoin and Ansaldo [18]. In that project, WWII shelters were listed among the huge variety of underground cavities that played a significant role on the history of the aboveground city, which could be enhanced by a task force including geologists, archeologists, engineers, urbanists, psychologists, economists from the academy, and local bodies.

During the project “Underground for Kids” (2008)—sponsored by the Office for Public Instruction of Naples (MIURAOODRCA.UFF., Prot. 11915, 21 July 2008), the Municipality of Naples (Comune di Napoli, Prot. 401, 5 August 2008) and the Province of Naples (Provincia di Napoli, Prot. 22981, 4 March 2008)—a systematic approach was taken dedicated to the collection of memories of people who took refuge in the Neapolitan underground shelters during WWII. The goal of the project was the activation of an intergenerational exchange between students from primary schools and their ancestors. In this context, the schemes of both structured and unstructured interviews were studied.

WWII shelters in Naples have also been selected for case studies within the bilateral project between CNR and the Japanese Society for Promotion of Sciences (JSPS) (2018–2019/2020–2021), “Damage assessment and conservation of underground space as valuable resources for human activities and uses in Italy and Japan” [19,20,21].

Last but not least, the debate carried on within the current CA18110 Underground4value project (2019/2023)—“an expert network, aiming at promoting balanced and sustainable approaches for the conservation of underground heritage and, at the same time, realizing the potential of underground spaces” [22,23]—which stimulated the adoption of innovative elements for the interpretation of UBH elements [24,25].

Although the first interviews have already been carried out immediately after the definition of the guidelines, the project has been on hold for a few years.

The COVID-19 pandemic, which has claimed many victims precisely among the people that could have been included in the group covered by this work, made the collection of testimonies unfeasible. This is why the collection of testimonies and their elaboration have undergone an acceleration in the last year and have been brought to completion.

The research, unfortunately, is very topical today: the Russian–Ukrainian conflict, still ongoing, has re-proposed the same dynamics of escape and the search for places of protection underground. Today, the narrative of pain, now in the media, is taking place precisely with the dissemination of news and testimonies concerning the most vulnerable, the children [26,27,28,29,30]. Concerning the WWII stories, the main goal of this research is not only to report the stories but also to adopt them as sources in the interpretation of WWII shelters in Naples in order to improve their significance within the local historical scenario and eventually activate dedicated enhancement processes.

2. Materials and Methods

During the first phase of the research, the UBH theoretical approach was adopted in the analysis of WWII shelters in Naples [9]. This approach was selected because, from one side, it allows the inclusion of those elements in an international classification dedicated to caved architecture and, from the other, it can be adopted in the analysis of their history and subsequent uses as well.

The methodology consists of a systematic flux of analysis that allows a special focus on the adoption of cavities as shelters during WWII and supports the analysis of their previous historical uses and their subsequent reuses. All the above-mentioned aspects can be profitably included in the dedicated enhancement projects at the core of the research.

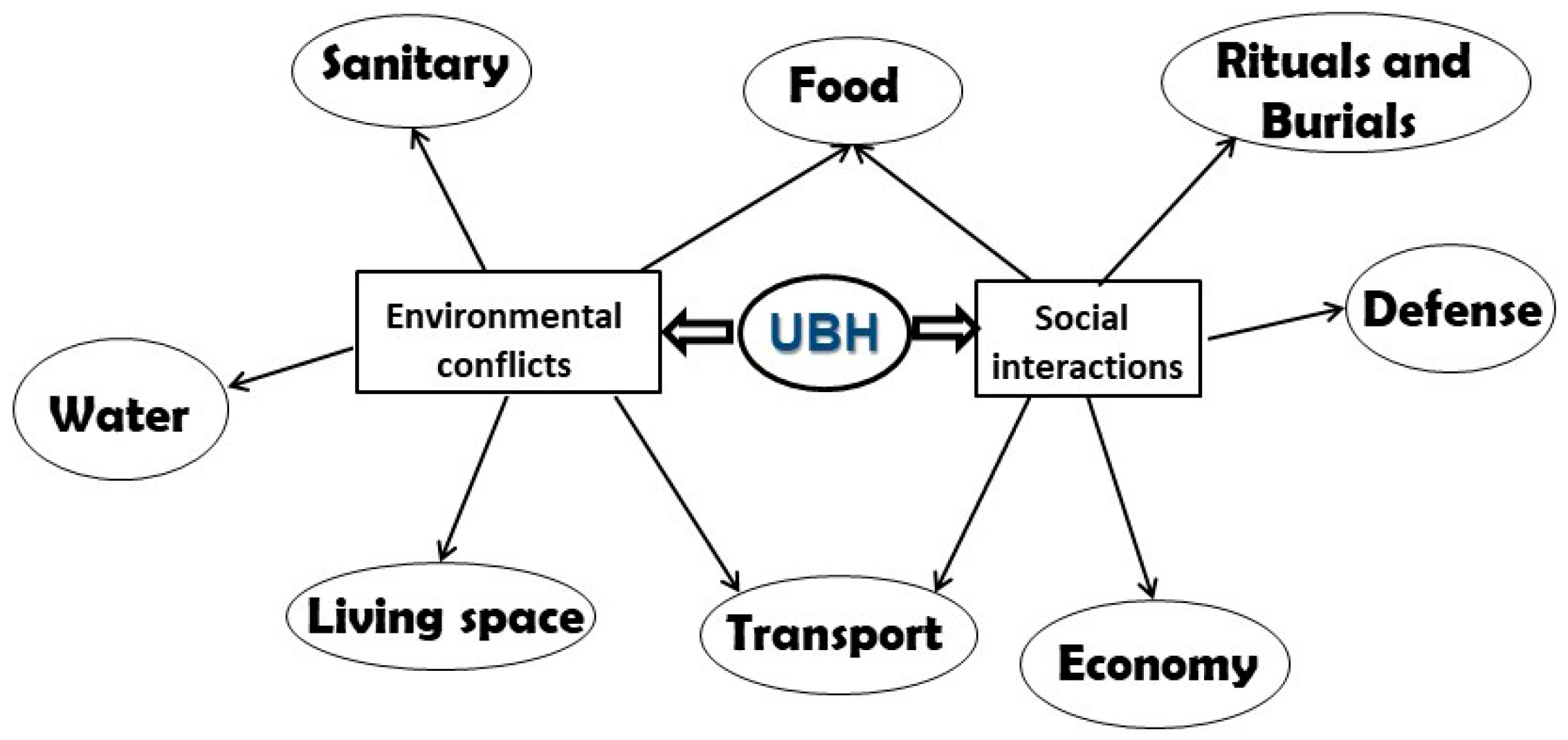

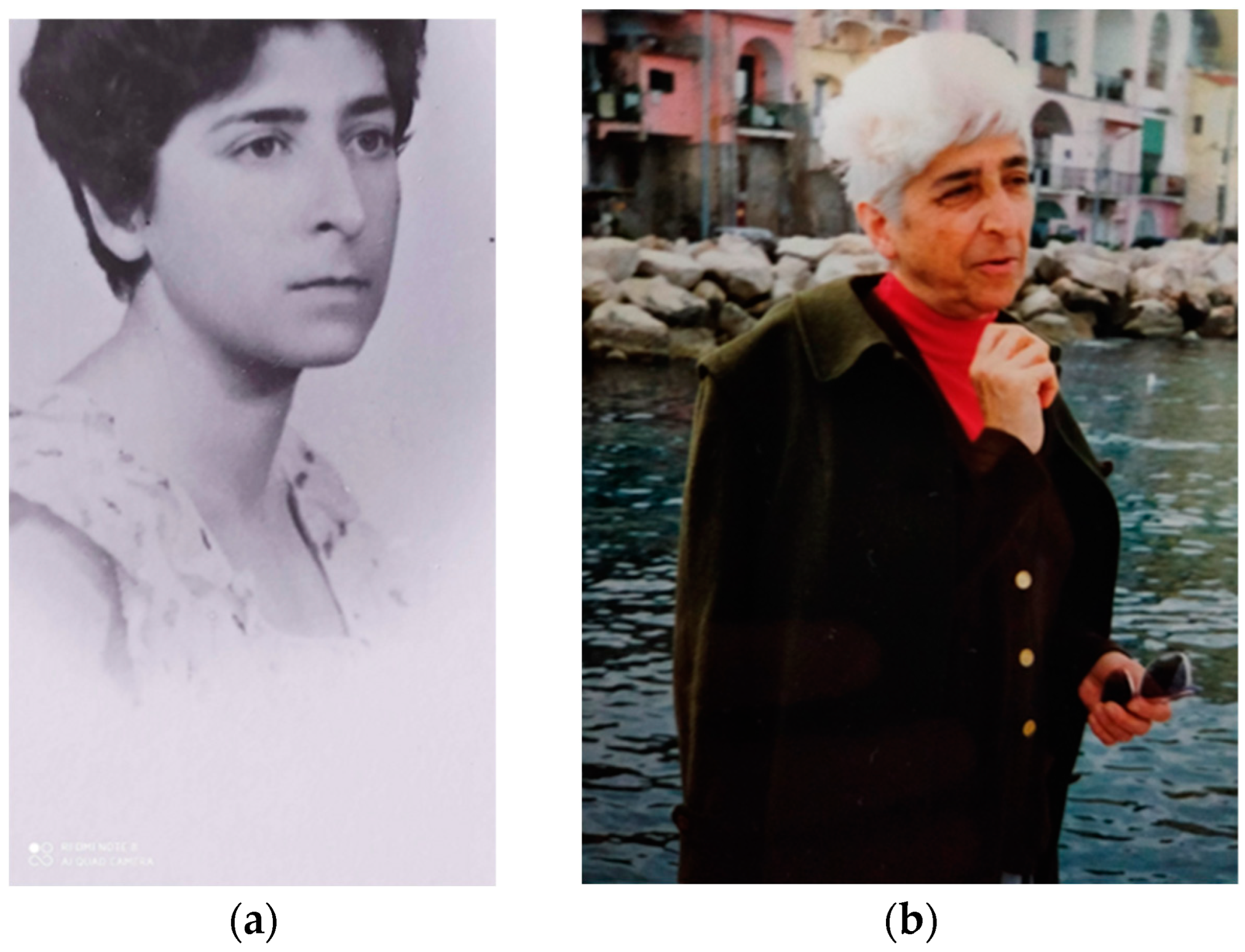

The UBH approach classifies all elements historically built, enlarged or transformed in the underground that, today, can be considered significant assets of local cultural heritage. Regarding their classification, two main groups have been pointed out: the first refers to elements that were used to manage several environmental conflicts, and the second refers to elements built to manage some social interactions. Eight functions are connected to these two main groups: Water, Sanitary and Living Space are included in the first group; Rituals and Burials, Defense and Economy are included in the second; and Food and Transport are included in both of them (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Underground Built Heritage (UBH) chart (by author).

Once classified with reference to their adoption as WWII shelters, histories of these elements were studied. While adopting again the UBH approach, all the possible primary uses, the correspondent functions and all transformations that occurred before their final adoption during WWII were analyzed.

In the end, the research focused on the state of the art with reference to the shelters’ current role as cultural assets from wars and conflicts. Again, the UBH approach was adopted to study the four levels of possible contemporary reuses. In the cases of WWII shelters, the following levels of possible reuses have been listed:

- Interpreted WWII Shelters: shelters transformed into museums and included in protected areas or within cultural routes;

- Protected;

- Reused WWII: the hypothesis of the introduction of a new function into the former shelters;

- Abandoned.

During the second phase, with reference to the above-listed criteria, a few case studies of WWII shelters in Naples were selected.

They have been classified as follows: included in underground touristic routes and museums; protected within urban parks; neglected with reference to their cultural value. All the sites selected have been inspected; during the onsite visits, pictures were taken as well.

Third, fourth and fifth phases of the research can be considered those which characterized it the most from the theoretical and methodologic points of view. In this section, a socio-anthropological analysis of people involved in wars and conflicts was conducted by adopting oral sources from witnesses who recovered in bomb shelters to access new information [31] about WWII in Naples. These phases were stimulated by the theoretical contributions to the reconstruction of cultural values of war shelters “to exploit their commemorative potential” [32], by adopting the memories of children [33].

During the third phase, the focus was on the selection of people to be included in the sample. Initially, friends, relatives and colleagues who were in contact with potential candidates were asked for their cooperation, and then managers from the most significant underground cultural routes were contacted to ask them if they knew former refugees. Finally, a call for interviews within a dedicated Facebook page called Racconti dal sottosuolo. La guerra vista con gli occhi dei bimbi rifugiati [34] (Figure 2) was opened. The page stimulated more than 60 responses, which were verified one by one. During this selection, all second-hand testimonies and those of people who did not live in the city of Naples during WWII were excluded. COVID-19 affected this phase of the research. Several proposals could not be finalized because people were very afraid of welcoming strangers into their homes; some participants also died before restrictions ended. The final sample consisted of 23 people.

Figure 2.

Home page of the Facebook call for interviews (by author).

During the fourth phase, the memories of children who took cover in the WWII shelters were collected. Interviews were carried on and recorded on the basis of both structured and unstructured interviews and according to the oral history methodological approach [35,36,37,38]. Data collected during the structured interviews included name, nickname, date of birth, components of the family, pets, address at the time, city area at the time, nature of the shelter (private or public), shelters’ equipment, personal equipment, recovery bag, and parents’ occupation at the time. Data collected during the unstructured interview focused on personal memories, and they have been organized as follows: food, fear, parental protection, collective special events, personal special events, community life, family life, cloth, war bag, personal diary, social and economic issues, and family displacement. During this phase, pictures of witnesses were taken, and old pictures representing them during WWII were reproduced as well. For all the interviewees, participation in the research was a very important occasion; they were all well dressed and very excited. At the beginning, they were very scared, and, above all, they thought they did not remember enough elements that could be useful to the research. After an initial moment of embarrassment, however, each conversation was very lively. On some occasions, the interviews were attended by caregivers, children or grandchildren; however, they were forbidden to interfere with the narration. At the end of the interviews, even the closest relatives of the witnesses reported that they had never had such a detailed account about their memories regarding WWII. All the interviews were fully recorded with a portable recorder. However, since all the visits turned into convivial events—which included sharing coffee, chocolates, homemade cookies or desserts—and the conversation often deviated from the subject of the interview by including the most varied topics, during the transcription, all the elements not related to the purposes of the research were omitted.

Even though sensitive data such as family names, dates of birth and current addresses have not been published, at the end of the interviews, all contents of the interviews and pictures were licensed, and declarations of consent were recorded and uploaded when the research was submitted.

During the fifth phase, all data collected were organized and classified with reference to all the different issues that emerged during the interviews. In this phase, outputs from the interviews have been approached for the interpretation of WWII shelters as cultural elements of wars and conflicts for the first time.

In the final phase, selected case studies and the outputs from interviews were matched on the basis of territorial criteria, i.e., the areas of the city where shelters were located and where witnesses lived during WWII.

Finally, the hypothesis of introducing the results from interviews as sources for the interpretation and enhancement of the corresponding assets, in the form of artistic interpretation, has been introduced.

3. WWII Shelters as Elements of the UBH Class

During WWII, Naples was one of the cities most affected by bombing. In fact, the city was a strategic objective: its port was one of the most important ones in the Mediterranean area, and it was a fundamental commercial and industrial crossroad as well. Its logistic role was the reason why the city was bombed all the war long: in the beginning by the English (1940/41) and then by the Allied Forces (1941/44) [16,39]. During the attacks, about 25,000 citizens died out of a total of about 900,000 [40]; over 200,000 rooms collapsed, 65% of the transport facilities went out of order, telephone connections were interrupted and the port was seriously damaged. The gasholder was destroyed, 10 hotels collapsed and historical monuments, museums and churches were bombed as well [41].

Despite the fact that the local population was involved in all phases of the conflict and struggled with all of the social and economic issues connected to the war, during the air attacks, citizens had to face and solve the vital problem of defending their physical safety over all.

The subsoil of Naples supported Neapolitans by offering refuge to those who could not move away from the city. Tuff caves, dismissed aqueducts and pools, canteens and transport galleries were transformed, connected and equipped to be reused as shelters.

From the moment the siren sounded, a parallel life began in the underground of Naples, a life in which the death and destruction of the emerged city were shortly suspended, and the possibility of salvation and integrity was offered by the bowels of the city: a life in which there was the opportunity of sharing time and things with other people, sometimes strangers.

The Ministry for Internal Affairs on 30 April 1943 listed 413 shelters in the city: 175 were classified as safe, 210 were classified as caves, and 28 were in the course of evaluation [41]. They can all be classified according to the UBH theoretical approach.

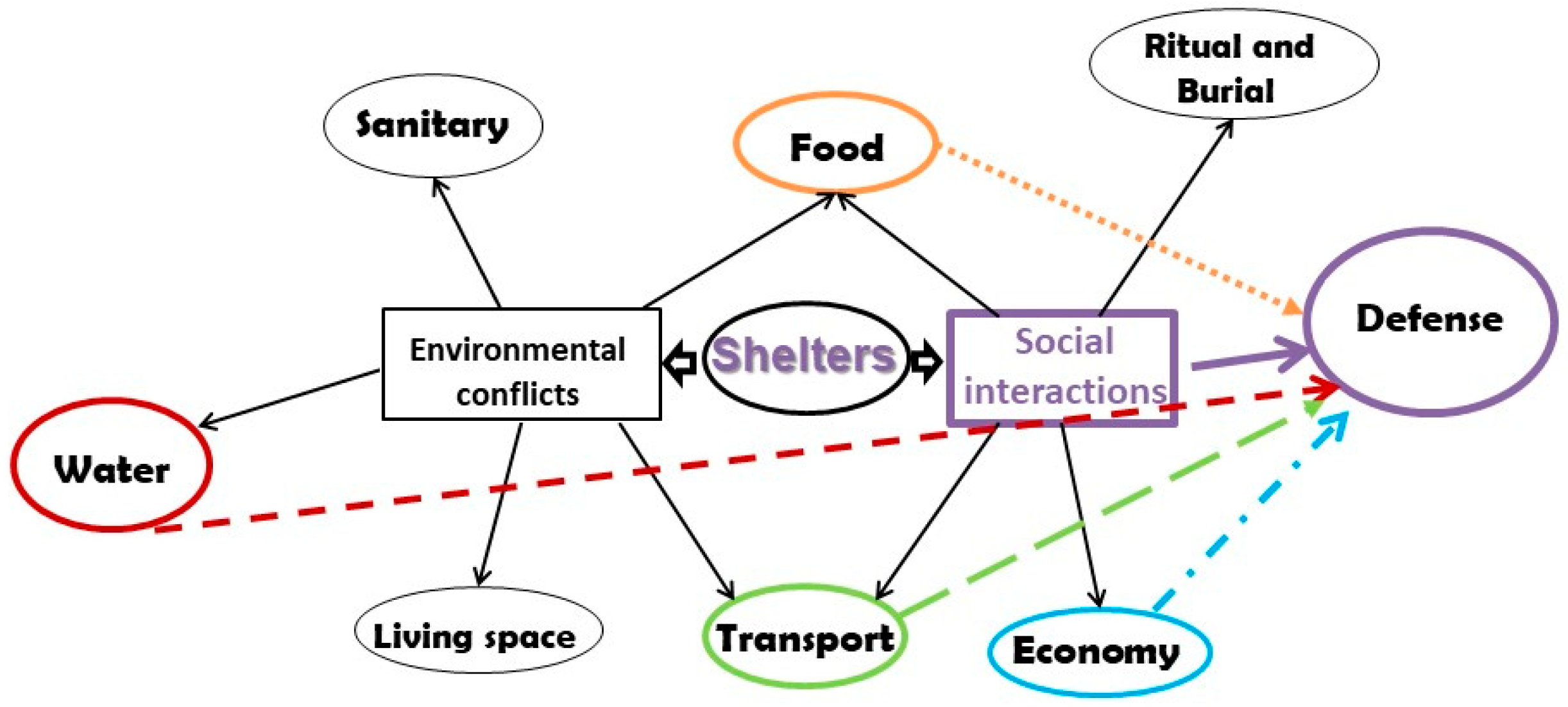

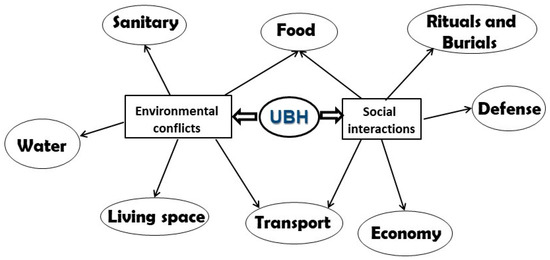

While adopting the theoretical approach of UBH, all WWII Neapolitan shelters can effectively be classified in the Defense function since they were all used by local citizens for their personal safety during the conflict (the violet line in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

WWII shelters as elements of the UBH class (by author).

However, since Neapolitan shelters were the result of the transformation of preexistent cavities, by adopting the UBH theoretical approach, all the possible previous uses of Neapolitan WWII shelters can be analyzed and visualized as well (the colored lines in Figure 3).

Sometimes wine and food cellars, originally caved for personal or collective uses, were adopted (the orange line in Figure 3). Sometimes galleries or pools from dismissed water aqueducts (the red line in Figure 3) and sometimes galleries of funiculars not in use during the war (green line in Figure 3) were adopted, but, usually, tuff caves from the modern era were transformed into shelters (the blue line in Figure 3). Very frequently, those cavities were interconnected to improve their performances as shelters. For example, very frequently, aqueduct pipes, mostly from the Roman Augustus network, were used to connect tuff caves, while stairs, once adopted to inspect pools and entrances to private cellars, were transformed into entrances to public shelters.

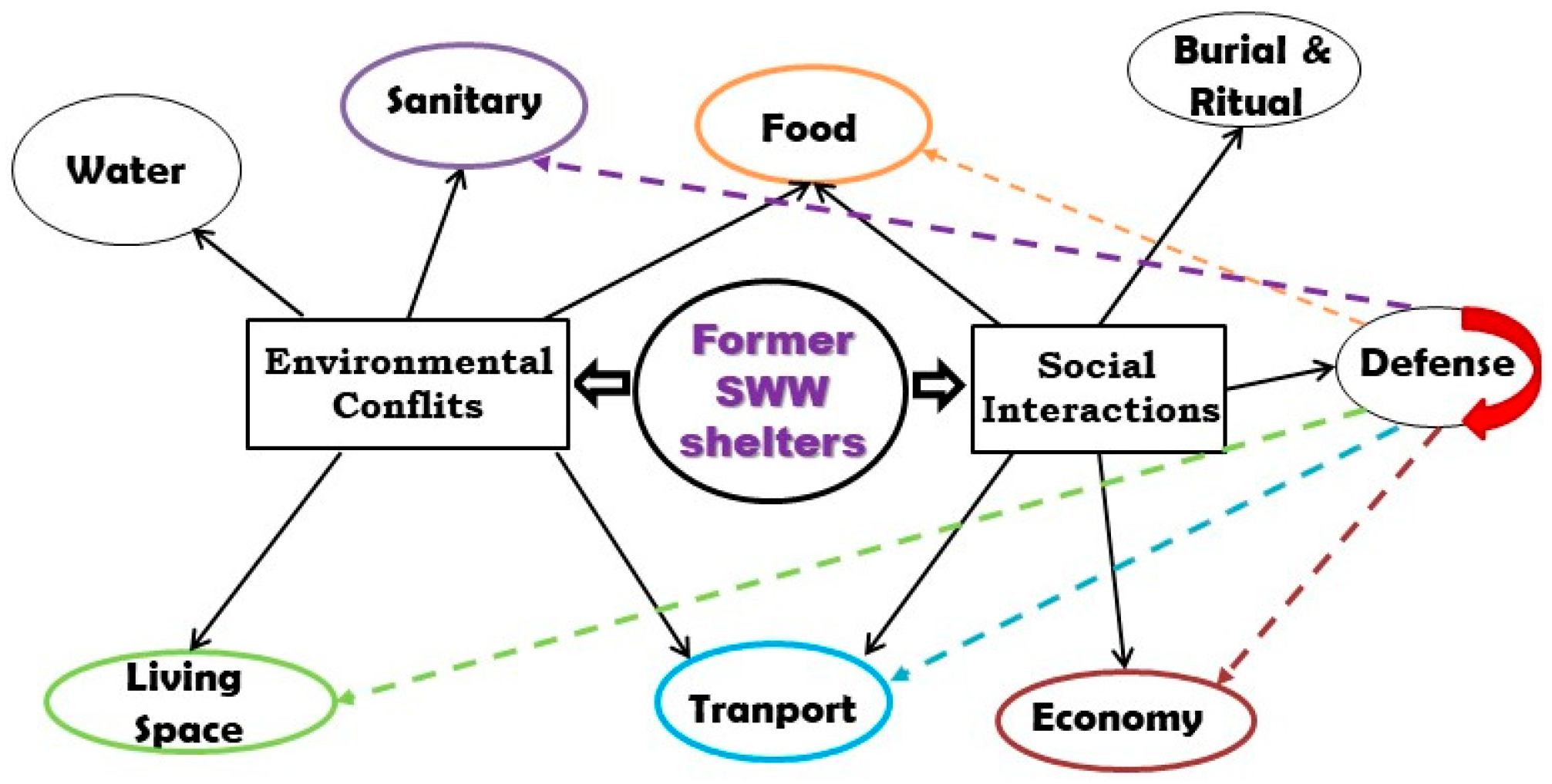

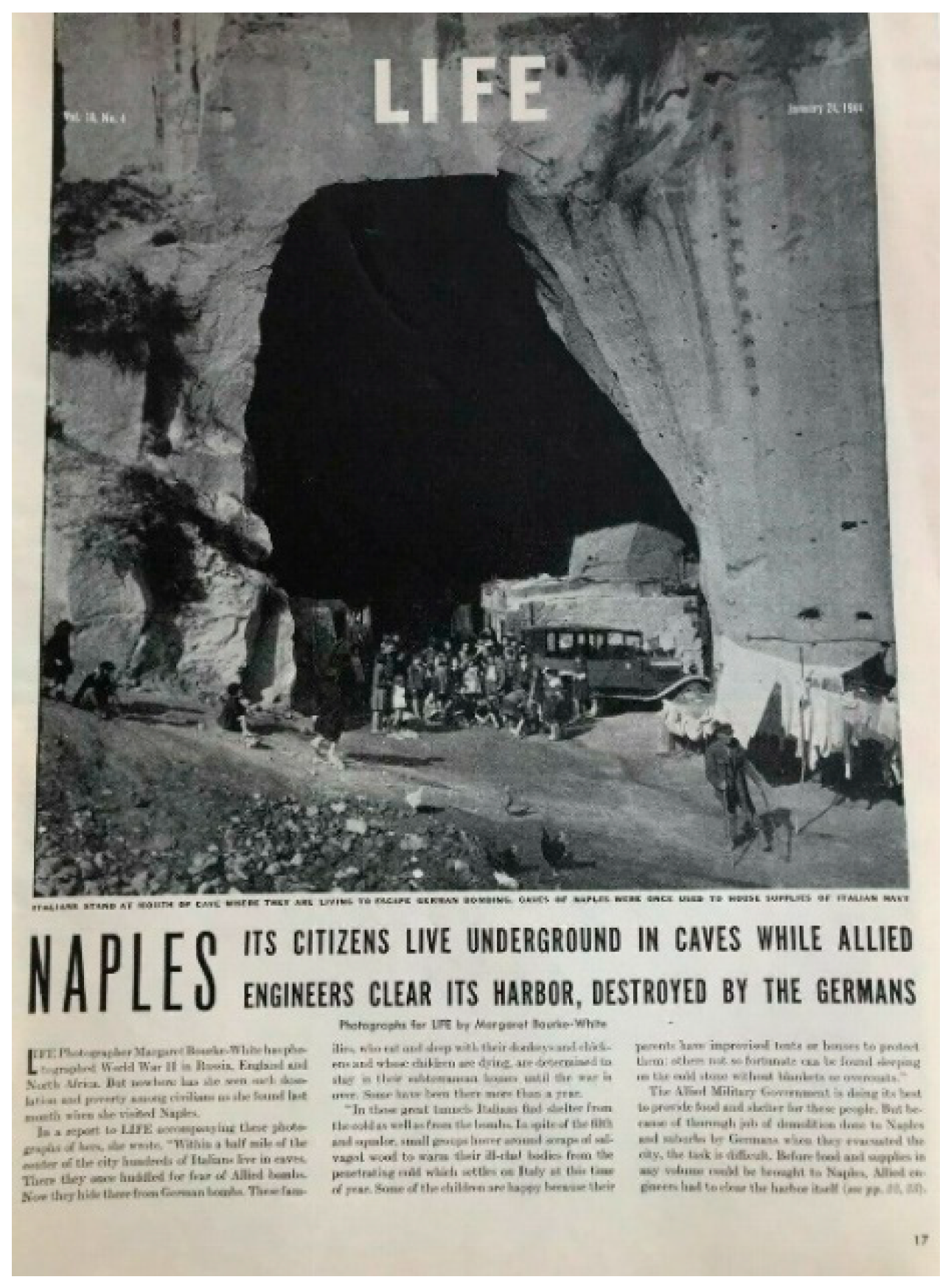

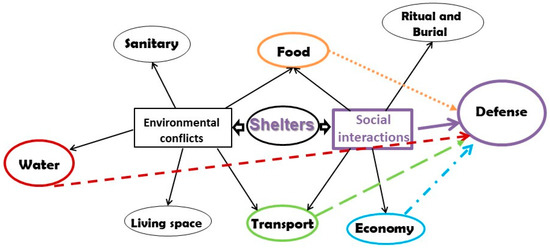

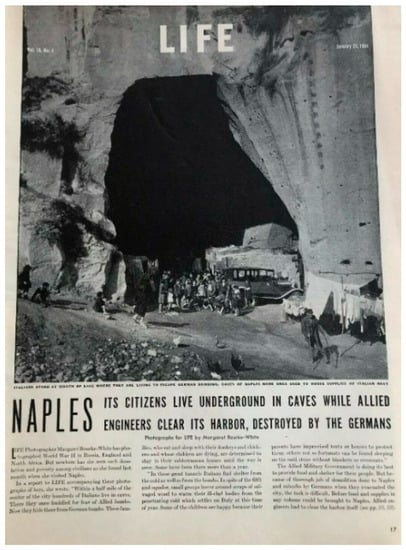

After the end of WWII, shelters were dismissed, but they were very often reused, the new functions were analyzed by adopting the UBH approach again (Figure 4). Firstly, the old shelters continued to be inhabited by those who had lost their homes during the bombings; in this case, the cavities passed from Defense to Living Space (green in Figure 4). This post-war troglodytic lifestyle was brought to light after the publication of a famous special issue of Life magazine [42] (Figure 5), and it turned to be one of the elements with the greatest impact in the media coverage about the conditions of the city of Naples at the end of WWII. When abandoned, many shelters became large landfills for the debris resulting from the collapses; in this case, the cavities passed from Defense to Sanitary (violet in Figure 4). Later, the empty spaces were used as deposits for impounded vehicles, which is another use within the Defense function (the Red U-turn in Figure 4) but also as depots or mechanical workshops, which pass from being classified as Defense to Economy (brown in Figure 4), or as food canteens, which pass from Defense to Food (yellow in Figure 4). After the great boom in private motorization, many cavities were reused as parking lots, passing from Defense to Transport (blue in Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Dismissed WWII shelters (by author).

Figure 5.

Troglodytic life as a symbol of post-war social and economic conditions (by author).

In conclusion, by always adopting the UBH approach, the former WWII shelters have been classified with reference to their current uses:

- Interpreted: transformed into a museum or included in subterranean touristic routes;

- Protected: included in protected areas and sometimes described in billboards but closed to the public;

- Reused: adopted as deposits, parking facilities, commercial places, etc.;

- Abandoned.

4. Selection and Inspection of Case Studies

The selection of case studies was carried out according to the criteria of having levels 1, 2, and 3 of reuse represented in the sample.

With reference to the first level, we selected two cases: some WWII shelters included in very popular touristic underground routes and some interpreted as museums. With reference to the second, we selected some WWII shelters protected within two urban parks. With reference to the third, we selected a shelter today reused as a parking facility.

The sites have been studied and inspected one by one; inspections took place in the period 2020-2022.

The case studies selected within the first group include the WWII shelters of Piazza Cavour 140 and those located in the underground of Pizzofalcone Hill.

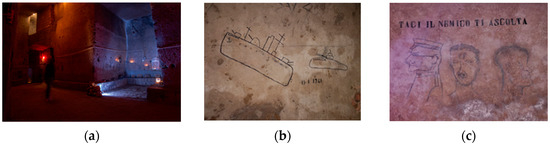

The WWII shelters of Piazza Cavour 140 are today included in the “Museo del Sottosuolo” (underground museum) [43]. This underground route includes the visit to the stone seats created to accommodate refugees and to the wall of graffiti created by people who recovered there during the attacks. Today, the seats are used as spaces for the exposition of art crafts, while the graffiti are illustrated during the onsite visits by the guides (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

WWII shelters in Museo del Sottosuolo: The stone seats (a). The graffiti realized by refugees: submarines (b) and Hitler, Mussolini and Hirohito caricatures (c) (by author).

Museo del Sottosuolo is a very well preserved and popular property [44], but the storytelling adopted focuses more on the primary use of cavities, tuff extraction caves and historical aqueducts, than on their historical reuse as shelters. In addition, the graffiti are not given the role they deserve, and their narrative power is mostly unexploited.

The shelters in the underground of Pizzofalcone Hill are today included in Galleria Borbonica [45], one of the top tourist destinations in Naples [46]. It is a former Bourbon tunnel, which interacts with the historic aqueduct of Bolla and several modern tuff caves. It offers four different tours:

- The standard tour, which is focused on the tunnel itself and its reuse as an impounded car deposit in the 1970s, on the aqueduct and on several heterogeneous historical remains;

- The adventure tour, which includes the navigation through a water tank;

- The speleologist tour, in which a tourist can visit the cavities wearing a caving helmet with a headlamp to explore the tunnels of the ancient underground aqueduct system of Naples;

- The memory tour, which focuses on the historical role played by those spaces. This tour includes the visit to the WWII museum, which collects some authentic objects of the time found in the subsoil during the excavations.

In Galleria Borbonica, tourists are introduced to the WWII shelters during the memory tour. They can visit facilities such as the toilets and the electric system; listen to the alarm, which is played on demand; and enjoy the museum setting as well (Figure 7). Even if the visit is very emotional, the inspection revealed that the exposition also includes non-dramatic elements such as, for example, a bath tub (Figure 7b). In fact, the remains from the excavation discovered in recent decades are organized with a significant scenic impact, but they are not all connected to life in the shelters, being very often the result of the use of the cave as a rubbish dump. The interpretation, the storytelling and the museum setting, with reference to this specific use of caves, need to be improved.

Figure 7.

WWII shelters in Galleria Borbonica: toilets (a) and the museum display of accessories found during recovery excavations (b) (by author).

With reference to the second group, the shelters included in Viviani Park and those of Via dei Cinesi were inspected.

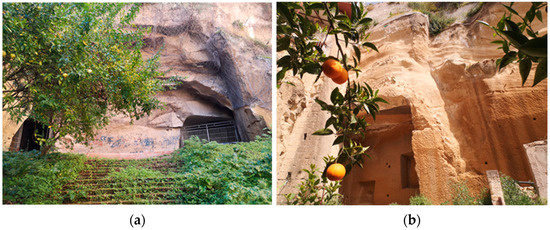

Caves included in Viviani Park are located in a green area, which interconnects the upper side of the city and the city center. The park is one of the most popular recreational areas of the district; it hosts a playground and a dog area. In the webpage from the Municipality of Naples [47], the cavities are described with reference to their first historical use: modern tuff extraction caves. Their reuse as WWII shelters is not mentioned anywhere, and they lay in a state of abandonment; when they were inspected, they were closed to the public (Figure 8a).

Figure 8.

WWII in urban parks: Viviani Park (a) and the Orange Garden (b) (by author).

The caves of Via dei Cinesi have been recently included in a recovery plan financed by Fondazione Banco di Napoli, Saint Gobain e Futura Trust and supported by the Neapolitan designer Riccardo Dalisi [48]. Today, they are part of the Orange Garden, a retraining space dedicated to marginalized children and local enterprises in one of the poorest areas of the city. The cavities are closed to the public, and their original historic function, their tuff extraction caves, and their historical reuse as WWII shelters are not mentioned anywhere (Figure 8b).

With reference to the third level, a complex of caves located in Corso Vittorio Emanuele, a gateway between the lower and the upper sides of the city, was inspected. Those cavities, born as tuff caves and then used as shelters during WWII, are conveniently located beside several famous hotels, the Cumana Railway station, the Chaia Funicolare’s station and in within a very populated area of the city with a lack of parking facilities. In this perspective, it is not surprising that they have been reused as a parking facility: Parker’s Garage (Figure 9). Today managed by a private firm [49], this efficient parking area offers several facilities dedicated to tourists such as shuttle services, caravan and touristic bus parking, a bike rental, and special prices for groups. Even if Parker’s Garage is one of the most structured and efficient underground parking facilities in the city, there is no evidence of this implementation of the historical caves during WWII.

Figure 9.

Parker’s Garage (by author).

5. The Interviews

Today, about 80 years after the end of the war, those who took cover in the underground shelters during over 100 attacks [39] still keep the memories of their lives in the WWII shelters, and those stories are very often part of their family storytelling.

The attempt of transforming those memories into additional values for WWII in Naples has been the result of the optimization of previous academic approaches to address the interpretation of shelters [6] and the implementation of their biographies as historical places [3]. In addition, the experimental adoption of visual art to interpret the emotions of children who took cover in safety shelters was studied [50].

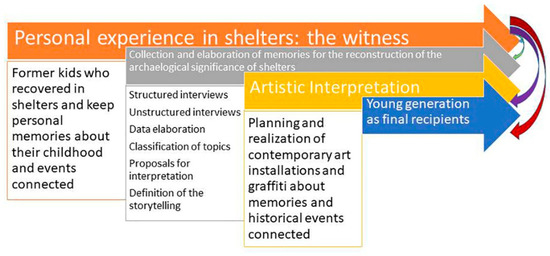

The final goal of this phase of the research was to schematize the intergenerational passage of experiences from the generation of witnesses to the final recipients; this attempt is summarized in Figure 10. The experiences pass from the witness (first stage in orange) to the professional researcher who collected and elaborated data (second stage in grey), to contemporary artists for the transformation of outputs from research to installations (third stage in yellow), to the final recipients (fourth stage in blue).

Figure 10.

The intergenerational passage: from memories to artistic interpretations (by author).

Figure 10 also shows how the research optimizes previous approaches to the adoption of oral history for the implementation of the archaeological value of shelters and their biographies as historical places (green arrow on the right) [3,6] and the adoption of artistic creativity in the interpretation of shelters by children who took shelter during conflicts (violet arrow on the right) [50]. The red arrow shows the passage from the memories of former children to the final recipients in this research.

The main actors of this phase of the research are the children who lived through WWII; in their memories, the time spent in the shelters does not have an exclusively negative connotation; it is part of their childhood, and the subsoil was the place where their future was born. It was not only a time of darkness and danger but also of parental care, social life and daily routine during WWII.

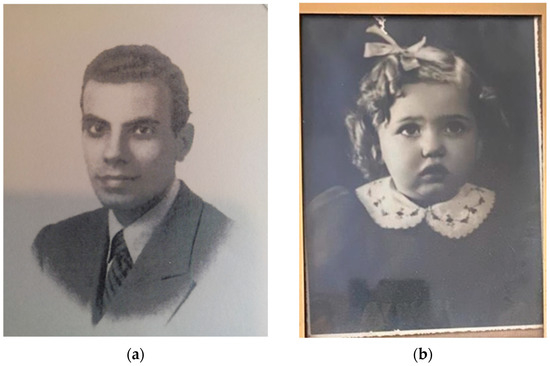

The results of 23 interviews have been published; they consist of two different sections: the first is based on a structured scheme, the second is the organized around fixed topics of unstructured interviews. Due to the age of the people, it was sometimes difficult to pass from one section to the other, and very frequently, heterogeneous topics were discussed, such as, for example, general memories from their childhood that were not connected to their time in the shelters at all. In those cases, only the memories connected to the current research have been selected and studied even if, according to the oral history methodology adopted, all the interviews have been integrally recorded. Pictures were taken during the interviews (Figure 11), and old pictures from WWII were collected. When diaries, documents, lists, pictures and newspapers from WWII were shown during the interviews, pictures were taken as well. The final goal of the research was to collect the largest variety of elements, not only for the transformation of “individual memories into collective ones” [51,52,53] to implement the value of WWII shelters but also to adopt those historical caves as gateways for some historical events that occurred in Naples during WWII in Naples.

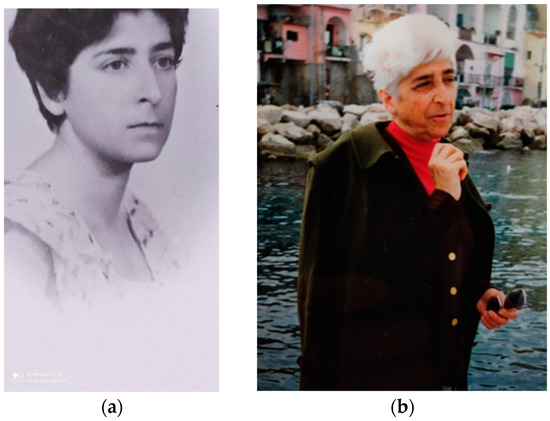

Figure 11.

Pictures taken during the interviews (by author).

During structured interviews, general data were collected: name, nickname, year of birth, number of family members during WWII, address, city district (which was codified for a better impression), the nature of the shelter (private or public), the shelter’s equipment, personal equipment, recovery bag, and the parents’ occupation. During the unstructured interviews, data and information about food, fear, parental protection, collective special events, personal special events, community life, family life, clothes, diary or documents, social/economic issues and family displacement were collected.

Anna, Antonio, Melina, Giuseppina, Pina, Renata, Nina, Annamaria, Lenù, Bruna, Assunta, Lilli, Chiara, Bellella, Elena, Maria Rosaria, Florio, Pasquale, Elvira, Paolo, Olimpia, Vera and Maria were the protagonists of the interviews.

6. Topics and Values for the Interpretation of WWII Shelters

The results from both structured and unstructured interviews have been organized with reference to five main topics: the histories of children, social life, social inequities, personal events and historical events.

6.1. Histories of Children

Twenty-three former children (Figure 12) with very distinctive characters have been interviewed: from the upper classes to the poorest, orphans and those with large families, those who recovered in public shelters and those who recovered in private cellars.

Figure 12.

WWII children (by author).

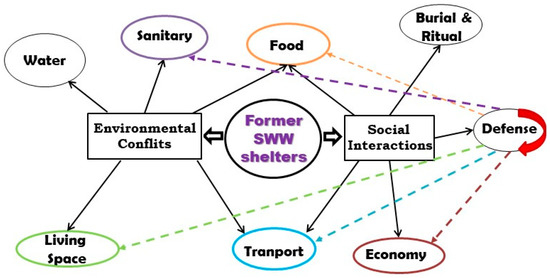

Of the 23, 17 were females, and 6 were males, they were born in the period between 1912 (Florio) (Figure 13a) and 1940 (Maria Rosaria) (Figure 13b).

Figure 13.

Florio, the eldest, (a) and Maria Rosaria, the youngest (b) (by author).

They lived in various districts of the city, and in some cases, they moved during WWII as an effect of bombings. Sometimes they belonged to very big families, such as in the case of Bellella, whose family had 16 members. Sometimes they were only children, such as in the cases of Pasquale, who had been raised by his grandparents, and Maria Rosaria, who was adopted by her uncles. Sometimes their parents were very distinguished professionals; sometimes they were struggling with structural unemployment or unemployment due to the conflict.

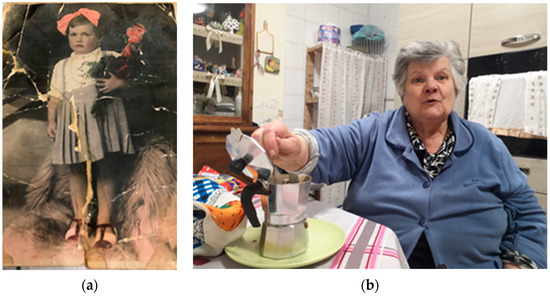

All those differences had effects on parental cares, personal and collective equipment and time spent in the shelters. Frequently, children from a lower social and economic level adopted caves as a stable living space, such as in the cases of Bellella (Figure 14) and Giuseppina. When this happened, their parents carried down mattresses and blankets, movable toilets for children and food pots as well. In the case of the upper classes, children had special cloths and spent only a few hours in the shelters, never having food there. In those cases, they remember a special recovery bag with the family’s valuable items that their parents used to carry with them during the attacks.

Figure 14.

Bellella at the time of WWII (a) and during the interview (b) (by author).

While considering all these differences and the fact that sometimes the interviews were in Italian and sometimes in Neapolitan, the most common words adopted were food, [54] and fear. In fact, all the children experienced a poor diet during the war, and they all connected their experience in the shelter with darkness and bombing.

The interviews have been summarized below.

Anna (1928, interviewed on 29 January 2011) was the daughter of the capopalazzo, the person in charge for her private shelter in one of the most beautiful buildings in the upper side of the city. She reported that her father maintained his leadership attitude (he was an electric engineer) in the underground. During the alarms, her father had to check that all people had moved before closing the main door of the building and the shelter’s entrance; she also reported that her father had to report to the local authority.

Giuseppina (1937, interviewed on 11 April 2013) had to take care of her six siblings in the underground since her mother left them there all day to go to work. She remembers that when her mother came back in the night, she carried with her a pot with the soup and a clean portable toilet for her children; when she left in the morning, she carried the pot and the toilet back.

Pina (1927, interviewed on 19 August 2015) was a piano student and kept a personal diary in which she reported all the most salient events of this difficult period with dates, comments and drawings. During the interview, she proudly showed her diary and reported that during the alarms she spent her time reading by candlelight or studying algebra and trigonometry with her classmates.

Renata (1934, interviewed on 5 October 2015) reported that, during the first period of the bombings, the private shelter of her building was accessible only from her apartment and that all the inhabitants had to run across her living room to reach it. She recalls that the children had their favorite toys with them and that they played with each other. Their shelter had been set up with armchairs and other comforts, but it was still very cold; she remembers her older sister always saying she did not know if she was shivering from cold or from fear. She recalls that her mother would prepare a special lunch on Saturdays and that the alarm always interrupted their main meal of the week. She also reported that the alarms were always preceded by a phone call from a family friend who worked in the prefecture and who warned them of danger.

Nina (1936, interviewed on 9 October 2015) was motherless and she was subjected to a regime of extreme protection: she had no friends, could not play with other children, and did not attend school. In this context, the time spent in the shelter was the opportunity to hang out with other children who, in the dark, could not see the hated black dress she was forced to wear as a sign of mourning.

Annamaria (1932, interviewed on 10 October 2015) recalls that the first shelter they took refuge in was not safe and that her family decided to move to another one. She reported that her mother carried with her blankets for her and her little brother and that she always had a bag containing all the family valuables.

Lenù (1930, interviewed on 20 January 2020) was a special girl. She had suffered through the polio epidemic, and she came out with some mobility difficulties. During the war, she lived with her family on the fourth level of a beautiful building in the upper side of the city. During the alarms, her relatives, usually her father or her brother, helped her down the stairs that led to her building private shelter. She reported that once, she was in the house alone with her old grandmother during the alarm and that she told her, lying, that it was not a serious alarm and that it was not necessary to go down. However, after the first explosion, which shattered some glass, they rushed down to the shelter; she did not realize how it could have happened! Lenù had a pet, a white cat named Frufrù, and she remembers that she was not allowed to take him to the shelter; she reminds that she was very upset because another girl was allowed to take her doggy in her arms, while her pet struggled with fear alone and took refuge in pots during the bombings.

Bruno (1938, interviewed on 12 February 2021) was very young at the time of the war, and he does not have many memories regarding the shelter; however, he reported that once, going up to the surface, they found themselves facing a great fire: the building next to the one where they recovered had collapsed. Following this episode, the family decided to move to the countryside.

Assunta (1928, interviewed on 25 January 2020) was the daughter of a railway man who worked on tank components during the war; her mother, of Tuscan origins, always carried a blanket for her two daughters and a bottle of water. The mother did not want them to socialize with other children because she was afraid they would take on the Neapolitan accent, which she detested.

Lilli (1927, interviewed on 25 January 2021) was the daughter of a wealthy pharmacist; during the attacks, her family took refuge in the private shelter of her building. The shelter did not have toilets and, since her home was on the ground floor, the refugees had to go to their private bathroom in case of need.

Chiara (1931, interviewed on 29 January 2020) lived in the Sanità district, in the building next to the famous Sanfelice Palace. Chiara and her family were terrified by bombings because on many occasions when they came out of the shelter they had seen the bodies of the victims of the collapses. Their shelter was dark and cold, and there were no places to sit, the refugees’ only thought was death.

Rita (1936, interviewed 15 February 2021) was the fourteenth child of a very poor family, and she was the first girl. Being blonde and with blue eyes, she has always been called by the nickname of Bellella, the pretty girl (Figure 13a). She still lives in the same basement, one of the famous Neapolitan bassi, in which she has lived all her life. Her house is located right in front of the caves where her family moved during the period of the bombings, adopting them as a living space. Bellella reported that her father had a heart condition and that he could not face the alarms; this was the reason why the family had equipped a space in the cave with beds, mattresses, a fire set and various pots for preparing meals. It is in that quarry that her younger sister was born and that Bellella witnessed the birth. Her older brother was in charge of running the shelter. In particular, he was responsible for collecting water for daily needs from a public fountain and transporting it inside the quarry in some tanks; he also took care of coordinating the collection of wood to feed the fire inside the shelter.

Elena (1934, interviewed on 16 February 2021) belonged to a middle-class family who had recently moved into a beautiful Art Nouveau building. During the alarms, the family moved to the basements of the building, which were lit up and had been equipped with tables, chairs and armchairs. Elena’s mother had also brought down a rocking chair where Elena’s younger sister rested, wrapped in a blanket during the alarms. Elena reported that at a certain point her private shelter was connected to the public one and that, therefore, the confidentiality of the first accommodation was lost to the great disappointment of her family. For her, instead, this new situation was an opportunity to meet her classmates; even after the end of the war, they continued to talk to each other about the events related to the war and the shelter.

Maria Rosaria (1940, interviewed on 18 February 2021) originally belonged to a very large family, but a couple of very wealthy uncles who raised her as if a princess eventually adopted her. She reported about all the attentions of her mother who carefully prepared the clothes and blankets to be used in the shelter. She also recalls how everyone pampered her and how everyone always offered her good things to eat; when she was in the shelter, she used to play with her friends and was never afraid. For her, that was an adventure.

Florio (1919, interviewed on 23 March 2021) was the oldest witness of my research. When he was interviewed, he was already 102 and still very lively and enthusiastic about this research. Florio, at the time of WWII, was already a young man who had finished his high school studies and worked for a company in Ponticelli, a Neapolitan suburb. Florio still retains a rich self-made documentation: a list of bombings, a list of the shelters where he lived, newspaper clippings, personal pictures, maps and a list of all the most important events. He shared with me all these documents. He reported that the company he worked for, OCREN, had set up a shelter for the employees but that it was not considered a very safe place; his brother, who worked with him, took refuge there during the alarms, but he preferred to flee to the surrounding countryside. When the alarm sounded outside working hours, he took refuge in various city shelters: once in the tunnel of the central funicular, once in the quarries of the Cellammare Palace, other times in the private shelter of the building where he lived with the family. In the Cellammare shelter, once he met an architect who spoke to him about the possible post-war recovery of those quarries as a theater; after the opening of the Metropolitan Theater, he always wondered if the architect he met by chance had signed the project. The definitive closing date of the Naples shelters is reported in his personal diary: 1 April 1945.

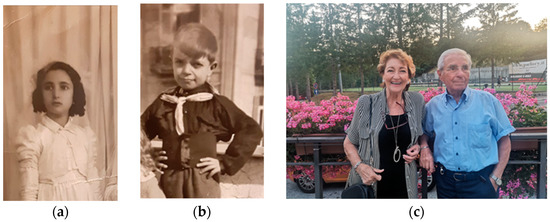

Antonio (1930, interviewed on 11 April 2013) and Melina (1933, interviewed on 11 April 2013) met in the shelters, and they got married at the end of the war (Figure 15a). They remember that the underground network was much extended and made it possible to reach even areas of the city that were very distant from each other. It was thanks to this possibility that the two young lovers could carve out moments of intimacy in the area near the sea, Mergellina.

Figure 15.

Couples: Antonio and Melina, who met in the shelter (a); Pasquale and Elvira (b) (by author).

Pasquale (1926, interviewed on 25 May 2021) lived with his grandparents who had raised him since they had lost, during the First World War, one of their sons named Pasquale as well. During the war, however, he moved in with his uncle, a priest, in the upper side of the city but continued attending the Vittorio Emanuele classical high school in the historical center. During the alarms, he took refuge with his uncle in a shelter near the church; he remembers that all the refugees prayed under the direction of his uncle. After the end of the war, Pasquale met Elvira (1933, interviewed on 25 May 2021), one of his sister’s classmates, and married her (Figure 15b). During the time spent in the shelter, Elvira sat next to her grandmother of Tuscan origins. She reported that the grandmother prayed and that she often repeated the phrase in her typical dialect, “Madonnina legagli le mani” (Madonnina tie his hands). She also remembers the access stairs to the refuge and that the younger boys sat down on the stairs to talk to each other; once, a blast caused by a bomb knocked them all forward raising a cloud of smoke. When the family moved to the financial district, they took refuge in the shelter where employees from the nearby post office came as well. Since the post office was one of the strategic objectives of the attacks, it was also bombed, and Elvira recalls that many bleeding employees, one even with an ear hanging off, reached the shelter. After this shocking event, the family moved to the Veneto Region and came back to Naples only at the end of the war.

Olimpia (1931, interviewed on 16 August 2021) was a beautiful blue-eyed child who lived with her family in the upper part of the city (Figure 16a). They did not move to the countryside because their father’s work commitments did not allow them to leave, and their mother did not want to leave her beloved husband alone. The mother’s love for her family is the leitmotif of Olympia’s testimony: the preparation of meals, sometimes left warm during the bombings; the care for special clothing for the shelter; her concern that everyone took refuge in time. Olimpia still remembers her mother with her hands on her head in desperation because she was late since she was supporting her old grandmother. Olimpia married Paolo (1929, interviewed on 16 August 2021) (Figure 16b), who at the time of the war was a very lively and inquisitive boy. Paolo reported that, despite the fear, he loved to peek through the cracks of the entrance to the shelter to see what happened during the bombings. His parents were terrified by his liveliness and always scolded him without being able to make him give up. Olimpia and Paolo are today a happy and beautiful couple (Figure 16c).

Figure 16.

Olimpia (a) and Paolo (b) at the time of WWII and together during the interview (c) (by author).

Vera (1933, interviewed on 6 December 2021) lived near the port, one of the strategic objectives of the attacks. During the first phases of bombing, the family took refuge in a private shelter, which was later declared unusable; from then on, they took refuge in a public shelter equipped with electricity but no toilets. Once there, the little girl was the object of ridicule by the older boys who said that an imaginary monster named Pantaleone was looking for her. She was terrified, and, even if her mother tried to reassure her, she only found comfort in a little friend of hers, Antonietta.

Maria (1932, interviewed on 2 January 2022) lived with her family in one of the first buildings that collapsed in WWII. The family was then housed in a former tobacco shop, which was closed during the war. It was a makeshift accommodation, without water and without electricity and with lots of insects, mice and cockroaches. During the alarms, her older sister supported her mother in organizing the escape into the well: the access was very narrow and became slippery when it rained; the refugees called it “l’occhio” (the eye). Even today, while remembering those circumstances, Maria exclaims, “tengo ‘o cuore comme ‘nu drappillo” (my heart is broken). Maria recalls that she spent time playing with her neighbors, waiting for the all-clear signal.

6.2. Social Life

In the darkness of the shelters, social life continued and did not always follow the rules adopted on the surface. Sometimes some social obstacles were removed, and the subsoil offered a freedom unthinkable on the surface. In other cases, children reported that their personal interactions with other children were hindered by their parents or that, even in those extreme conditions, there were forms of bullying and prevarication.

Perhaps Antonio and Carmela would not have met and would not have started their love story if they did not benefit from the freedom of movement they had in the shelter.

After all, shelters were a place for love affairs, reported Lilli. She remembers that in the darkness of the shelter the love between a young student on the top floor and a girl on the first floor took place. She reported that the girl came out pregnant during those underground encounters, and the wedding between the two lovers was organized in a few days. Another couple, clandestine in this case, also met in the darkness of the basement, and all children knew about that. Lilli reported that on the surface she would never have been made aware of those love affairs.

Elena, like almost all of the participants, reported that, during the stay in the shelters, male adults played cards, women talked to each other about family care and children used to play. For Maria Rosaria, the shelter was the place where she felt like a protagonist. In fact, because of her blond curls, she was called Shirley Temple, and she was always the center of attention. She remembers that she was asked to sing standing on a table and that she felt like a little star.

6.3. Social Inequities

With reference to the topic of solidarity among refugees and economic and social differences, the children’s stories show a very complex reality.

In fact, even if it is true that in many cases, especially in public shelters, during their stay in the underground, people from different social backgrounds found themselves sharing the same spaces, the differences existing on the surface were not always cancelled.

So, even if Lilli reported about the inclusive approach of her father with reference to other occupants and Maria Rosaria remembered sharing with other occupants, not all social inequities were eliminated in the shelters.

Lilli’s father was a pharmacist, and many customers, not having the money needed for medicine, paid him with food. This food was kept in their private cellar and, since at the beginning, their private shelter was closed to the public, they used to share food with their friends and relatives. When the shelter was opened to the public, the scenario changed; at the beginning, there were robberies, but, finally, her father, in contrast to the members from the original group of refugees, decided to share fruits, cheese and vegetables with all the newcomers.

However, sometimes, this situation was perceived as momentary, even as a sociological experience. Renata’s aunt, while referring to sharing spaces with people from different social backgrounds, used to say that in the shelters she smelled something like a “profumo di umanità” (scent of humanity).

Basically, as Antonio reported during the interview, “i ricchi rimanevano ricchi, i poveri rimanevano poveri, anche nel sottosuolo” (rich stayed rich, poor stayed poor, also in the underground). As proof of his assertion, he reported that there was a lot of envy and competition among children from different social backgrounds. Vera confirmed this conflictual approach: she remembered that her best friend, Antonietta, had no toys and only second-hand clothes. Vera used to share her toys with her during the time spent in the shelter, but she felt that Antonietta always envied her new dresses.

6.4. Special Events

Special events have been classified into two different groups: personal events and historical events. Personal ones are generally family experiences somehow connected to the time spent in the shelters; historical ones are significant WWII events that occurred in Naples and impacted life in the shelters.

6.4.1. Personal Events

Vera’s father died because he did not want to join his family in the shelter; she remembers that he used to say that he was afraid of the dark. The story Vera reported demonstrates how these children’s memories crystallized in the past. Vera’s father was a handsome man with somewhat libertine conduct; several times her mother had broken into his workplace in the throes of fits of jealousy. Before the last fatal attack, Vera remembers her father waving goodbye while he was standing nearby the entrance of their building. It is the last image she has of her father. That day, after the all-clear signal, she and her family emerged from the shelters and verified that their building had collapsed. The search for the missing began immediately, but, only the following day, her father was found. He was still alive, protected by the back of his iron bed, and he was beside a young woman. He was very seriously injured, and the first thing he said to his mother was that the woman told him the place where she kept her jewels; this information was intended for her heirs in case she died. In the end, she survived, but her father died after a few days of agony. Vera never elaborated on the events, and she still reports them with the innocence of a ten-year-old girl (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Vera at the time of WWII (a) and during the interview (b) (by author).

Sometimes even sickness was managed in the shelter; Bellella reported that her father once had a heart attack and that the doctor visited him in the shelter.

During the attacks, the variables were many: the choice of the shelter could be fatal, like the fear of the dark and closed places.

Pasquale reported that he survived an attack by chance. Once, he was on his way back home from the district beside the central station, where he had gone with a friend of his to buy a radio, when the alarm sounded. The two boys began to follow the line, which was heading towards the closest shelter, a building with two access stairways: A and B. They were about to enter by stairway A when the two boys were stopped by the “capopalazzo” (building supervisor) who suggested they use stairway B. It was their salvation. When they went back to the surface, they realized that a bomb had hit the A entrance, causing many deaths.

Olimpia reported that, even if the shelter were not always safe, it was better than nothing. A friend of hers, who was afraid of the dark and suffered from claustrophobia, never recovered and died because his building had collapsed.

The subsoil was not only a place of death and disease but also of life. Maria’s little sister was born shortly before a bombing in their makeshift lodgings; the newborn was placed into a drawer. When the siren sounded, everyone was concerned about supporting the young mother, but, in the general confusion, the baby was left behind. As soon as the mother realized what had happened, she cried and screamed so loudly that the father climbed up and walked home under the bombs to retrieve the little girl; she was sleeping peacefully in the drawer.

6.4.2. Historical Events

Several pieces of information about WWII historical events that were connected to the use of the shelters were discussed in the interviews.

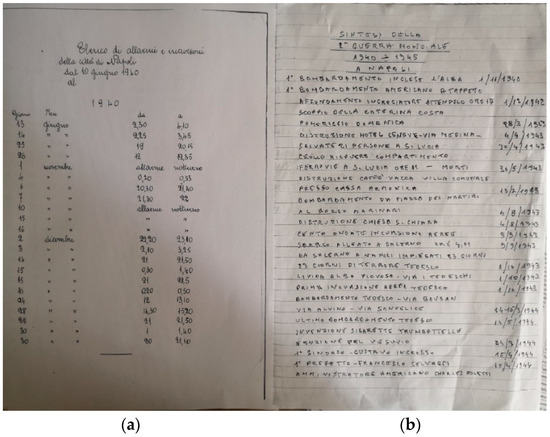

Florio and Pina reported the most significant events in their personal diaries (Figure 18). Pina reported all the alarms; she listed 384 alarms in total. The last line of her diary is dedicated to the A.R.M.I.S.T.I.Z.I.O. (end of the war) on 8 September 1943 (Figure 18a).

Figure 18.

Front pages from the personal diary of Pina (a) and Florio (b) (by author).

Florio, instead, listed all the major events that occurred during WWII in Naples from his personal perspective (Figure 18b). In fact, together with some very famous historical events, he also listed minor ones that impressed him very much: the collapse of Geneve Hotel (4 April 1943), the collapse of the shelter for workers from the railway company (30 April 1943), the collapse of the Café in the Municipal Garden (13 July 1943). He also reported about the eruption of Vesuvius (24 March 1944), the introduction of “trumbettelle cigarettes” (1944), the elections of the major of the city (15 April 1944) and of the person in charge for the local prefecture (14 April 1944). In his diary, there was space for events that impacted his personal life: the re-opening of San Carlo Theater where the Aida was performed (14 April 1945) and the improvement of the daily bread ration from 200 g up to 300 g (1 July 1944).

Florio, Bellella and Maria, reported about Nazi roundups looking for young men to enlist; they still remember how often people came to hide in the shelters. Florio reported that in his private shelter there was a very narrow space between the access stairway and the ceiling where, on several occasions, young men had been hidden. He also reported that, once, a young man was late and the door was closed so that I could not recovery in time; he was caught by Nazi “che giorno triste!” (what a sad day!).

Bellella reported about a secret place in the cavity that her brother had arranged to accommodate young men in the event of a roundup by Nazis. She remembers that his brother had been exempted from military service due to some health problems and that he was very motivated in supporting other young men.

The collapse of Santa Chiara Monastery [55], 4 August 1943, was one of the recurrent historical events in the interviews. Pina (Figure 19) reported it in her personal diary, and she made a pencil sketch of the scene she witnessed as soon as she left the shelter. The monastery was on fire, and a column of black smoke rose towards the sky: “sembrava come un altro Vesuvio!” (it looked like another Vesuvius!).

Figure 19.

Pina at the time of WWII (a) and at the time of the interview (b) (by permission of the heir).

The explosion of the ship Caterina Costa in the port of Naples, 23 March 1943 [56], was reported during the interviews as well. The ship, berthed in Naples on its way to Tunisia, had a load of explosives, tanks, tracks, ammunition, cannons and more than a thousand tons of petrol in drums in the holds. Its sabotage remains one of the unsolved mysteries of WWII. The explosion caused many deaths, including many colleagues of Florio, who only by pure chance was not on board. Florio reported that once he heard the news, he went to the port and watched in terror the fire that killed his friends.

Additionally, details from the so-called Four Days of Naples [57,58,59], were discussed in the interviews. This event concerns the insurrection of the Neapolitan population against the Nazis, which took place from 27 to 30 of September 1943. In those days, Naples was mobilizing in different districts and with diversified social and political intensity and participation in order to impose the accelerated exit of the Germans from Naples and, therefore, facilitate the entry of the allied troops. One of the symbols of this insurrection was the Littorio Stadium, transformed by the Nazis into a concentration camp for local prisoners to be deported to Germany [60]. Since Lilli sheltered nearby the stadium, she reported that during those days they recovered some insurgents who collected gunpowder, even from unexploded shots, to make bombs to be delivered to the Neapolitan troops. She recalls how all the children who hid with her in the shelter were involved in these very risky operations; she was very proud of the support given to this important page of the history of the city. This testimony is particularly important because there is no official documentation from the Nazi side or from the insurgent one. In fact, all documents from the German police were burned before leaving the city, and there is no official documentation from the clandestine insurrection. This is the reason why all the reconstructions of this event are supported by personal testimonies from the protagonists, all of which are of anti-fascist origin [61,62].

7. Discussion and Results

The results from the structured interviews are organized in Table 1. Regarding the names, in most of the cases, I adopted as the ID the given name. In the case of Carmela, Giuseppina (2), Liliana, Elena and Rita, their nicknames have been adopted. Only in the case of Nina a fantasy name was adopted. The districts where they lived have been codified as follows: U for upper side of the city, which corresponded to six people; H for the historical center, which corresponded to nine people; C for the city center, which corresponded to six people; and S for the Sanità district, which corresponded to two. Most of them, 12, lived in public shelters. Six of them lived in private ones, and five moved from public to private ones due to some security reasons. Due to the age of the sample, most of those interviewed were students at that time; there were 16 students in total. This aspect was strongly influenced by the corresponding social conditions. In fact, if we exclude Nina, who had a parental education; Bruno and Maria Rosaria, who were too young to go to school; and Florio, who was already an office worker, the remaining children who did not attend school (three in total) belonged to the poorest families of my sample. In fact, Bellella’s father and Melina’s father were unemployed, while Giuseppina’s was an angler struggling with unemployment during the war. In all those cases, they belonged to very large families with more than eight members, and, as it has emerged in the unstructured interviews, they had to take care of their younger siblings.

Table 1.

Structured interviews (by author).

The results from the unstructured interviews have been classified and organized in Table 2. Most of those interviewed reported about a lack of food (13 in total), about their fear during their time in the shelters (14 in total) and about their parental care connected (18 in total).

Table 2.

Unstructured interviews (by author).

The collapse of Santa Chiara church, the closure of schools, collapses, histories about Nazis and Americans, the sinking of the ship Caterina Costa and histories about the Naples insurrection against the Nazi regime were the most significant historical events they introduced in their interviews.

The interviewed also reported some personal histories connected to the shelters: people met there; special relationships; births, illness and deaths faced in the underground; etc.

Several social and economic issues have been introduced as well: poverty; unemployment; social and economic disparity; support from relatives; solidarity.

The data from both structured and unstructured interviews introduce several social and economic issues connected to the use of WWII shelters. They are about personal and family stories, daily and social life during WWII, parental care, friendship and social interactions and inequities. Sometimes they are even connected to main historical events. All these related issues, of course, improve the significance of WWII shelters as cultural heritage from wars and conflict, but how can they be profitably adopted in the integration of their interpretation while considering that WWII shelters are already the result of transformations of historical caves?

The option I selected is to adopt the storytelling based upon memories from children to integrate their significance for the benefit of younger generations that cannot benefit from direct familiar storytelling anymore. On the basis of this idea, my proposal is to adopt those memories as sources for the creativity of current young artists to convey contents about WWII that could be lost forever.

In this perspective, the WWII shelters of Naples could be the gateways to the issues that came out from the oral history research. This goal can be achieved using different approaches: from billboards to figurines; from video reconstruction to exposition settings; from audio installations to virtual reconstructions. It depends on the current use of cavities, their location and the users’ target as well.

With reference to the selected case studies and on the basis of the outputs of the oral history research, three hypotheses of possible re-inventions have been highlighted.

The first one refers to shelters already included in selected underground touristic routes. With reference to the case studies of Museo del Sottosuolo and Galleria Borbonica, which are both located in the historical district of the city, the improvement of the storytelling connected to the adoption of those spaces as WWII shelters is suggested. This goal could be achieved by including the elements which came out from the interviews of children who recovered in shelters located in this district: Antonio, Melina, Giuseppina, Annamaria, Bruno, Maria Rosaria, Pasquale, Elvira, Vera and Maria. A more relevant museum setting with reference to this specific topic is suggested, and the adoption of figurines, pictures of the protagonists of my research and of visual elements, which introduce the historical period, are recommended. Some graffiti could be displayed at the entrances of both the touristic routes.

The second refers to caves included in urban parks. With reference to the WWII shelters of Viviani Park, the adoption of the issues introduced by children who sheltered in the upper side of the city where the property is located (Anna, Lenù, Lilli, Florio, Paolo and Olimpia) is suggested. In this case, while considering that the audience of users of the site is intergenerational, the proposal refers to their interpretation as a cultural site and the adoption of billboards about personal histories of refugees and figurines as well.

With reference to the Orange Garden case study, located in the Sanità district, personal histories that emerged during the interviews with Bellella and Chiara could profitably be included in the enhancement of the former shelter. Since that property is connected to several historical reuses, starting from its original function as a modern tuff cave, the reconstruction of the relationship with the history of the Sanità district is suggested. In this case, their interpretation could be dedicated to local children that today adopt this open space as a playground is suggested. The proposal refers to the introduction of billboards and graffiti representing the personal histories of Bellella and Chiara and some WWII events in comic form.

The third refers to the case study of Parker’s Garage, located in the center of the city. In this case, the creation of a “museo obbligatorio” (the mandatory museum) has been imagined, a concept already successfully elaborated for the Linea 1 metro in Naples [63]. It consists of a permanent museum setting that has been realized as an exposition dedicated to passengers who benefit from the visit by simply accessing the stations. In this specific case, the intangible elements collected during the interviews to Pina, Nina, Renata, Elena and Assunta, who recovered WWII shelters located in the area where the parking facility is located, could be the subject of street art works on the walls of the quarry for the benefit of the users of the parking service.

8. Conclusions

The six-phase methodology adopted in the study of the WWII shelters in Naples provided the reconstruction of their historical functions and current reuses, focused on selected case studies, provided the collection of memories of WWII children who recovered there and supported the analysis of the results. In particular, the structured and unstructured interviews provided several additional elements for the interpretation and the enhancement of WWII shelters as elements of heritage from wars and conflicts.

During the first steps of the research, the WWII shelters of Naples have been included in the UBH class. Historical functions, historical reuses and the current uses have been analyzed both at a theoretical level and with reference to selected case studies. During the second steps, twenty-three interviews have been carried out, and all the issues introduced have been classified according to the various themes addressed during the narration in order to allow the reconstruction, in the future, of dedicated storytelling for WWII shelters. In the end, some operative hypotheses regarding the interpretation of WWII shelters as cultural sites from wars and conflicts have been highlighted with reference to the selected case studies.

I have to say that all the collected data are about WWII, a period little covered in the narration of the city of Naples, which mainly receives focus for its ancient history. From this point of view, WWII shelters, which are very common elements in the underground of the city, could be the gateway to the exploitation of this underestimated historical period.

In this perspective, the outputs of this research are, at the same time, the hypothesis of future research, which will be about planning several enhancements for WWII shelters in Naples, in collaboration with the Municipality of Naples.

Two projects have already been submitted to the Municipality of Naples for approval: a public event and two performances from a local young street artist. During the commemorative event, the mayor of the city should award the protagonists of this research for having passed the baton to the new generations with their precious testimonies. The second proposal refers to the display of two pieces of graffiti to be shown on the walls of the gallery, which connect Galleria Borbonica and Piazza Vittoria, and on the walls of Giardino degli Aranci.

Of course, this research is not exhaustive in regard to this topic. In the future, I really hope I can integrate more direct memories. By now, some archival sources have been highlighted in the library of the MANN museum in Naples where documents from the person in charge for the Galleria di Seiano WWII shelter have been collected. Data from the analysis of those documents are expected to integrate the research in the future; they report the same situation, the adoption of Neapolitan caves as bomb shelters during WWII, but from a different point of view. In this direction, a comparative study regarding social interactions between people recovered and those who were in charge of order and security is planned, and a new project will be submitted to Municipality of Naples.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants of the interviews or their heirs.

Data Availability Statement

Institute for Studies on the Mediterranean (ISMed), National Research Council of Italy (CNR), 80134 Napoli, Italy, https://www.ismed.cnr.it/it/ accessed on 18 December 2022.

Acknowledgments

I thank Gianluca Minin from Galleria Borbonica and Ettore Liberati from Parkers’ Garage for welcoming me and supporting me during my inspections. I thank Anna, Antonio, Melina, Giuseppina, Pina, Renata, Nina, Annamaria, Lenù, Bruna, Assunta, Lilli, Chiara, Bellella, Elena, Maria Rosaria, Florio, Pasquale, Elvira, Paolo, Olimpia, Vera and Maria for their support in the research. I thank Paolo Pironti for the optimization of Table 1 and Table 2.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Benjamin, W.P.; Noel, B.S. Heritage Tourism, Conflict, and the Public Interest: An Introduction. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2005, 11, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinidad, R. Negative Heritage: The Place of Conflict in World Heritage. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2008, 10, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, M.L.S.; Viejo-Rose, D. (Eds.) War and Cultural Heritage; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, P.; Shopes, L. Oral History and Public Memories; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Ruibal, A. Making things public: Archaeologies of the Spanish Civil War. Public Archaeol. 2007, 6, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshenska, G. Oral History in the Historical Archaeology: Escavating sites of Memory. Oral Hist. Lond. 2007, 35, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi, M.; Shariff, M.K.B.M. The concept of place and sense of place in architectural studies. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2011, 5, 1054–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Kudryavtsev, A.; Stedman, R.C.; Krasny, M.E. Sense of place in environmental education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varriale, R. “Underground Built Heritage”: A Theoretical Approach for the Definition of an International Class. Heritage 2021, 4, 1092–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, M. Heritage Interpretation and Sustainable Development: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenu, C.; German, R.; Gressier-Soudan, E.; Levillain, F.; Astic, I.; Roirand, V. Transmedia Storytelling and Cultural Heritage Interpretation: The CULTE Project; hal-01504222; Museum and the Web: Florence, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsche, N.; Reino, S.; Knox, D.; Bauernfeind, U. Enhancing Cultural Tourism e-Services through Heritage Interpretation. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2008; O’Connor, P., Höpken, W., Gretzel, U., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staiff, R. Re-Imagining Heritage Interpretation: Enchanting the Past-Future, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribaudi, G. Guerra Totale. Tra Bombe Alleate e Violenze Naziste, Napoli e Il Fronte Meridionale 1940-44; Bollati Boringhieri: Torino, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chianese, G. Napoli nella Seconda Guerra Mondiale. Ital. Contemp. 1994, 195, 343–362. [Google Scholar]

- Gargiulo, M. Uscire dalla catastrophe. La Città di Napoli Fra Guerra Aerea E Occup. Alleata Diacronie 2018, 33, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaro, P. (Ed.) Microstoria. A Venticinque Anni da L’eredità Immateriale; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Varriale, R. (Ed.) Undergrounds in Naples. I Sottosuoli Napoletani; CNR/ISSM: Roma, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Varriale, R.; Parise, M.; Genovese, L.; Leo, M.; Valese, S. Underground Built Heritage in Naples: From Knowledge to Monitoring and Enhancement. In Handbook of Cultural Heritage Analysis; D’Amico, S., Venuti, V., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 2001–2035. [Google Scholar]

- Bilateral Project CNR-JSPS Damage Assessment and Conservation of Underground Space as Valuable Resources for Human Activities Use in Italy and Japan. Available online: https://www.cnr.it/en/bilateral-agreements/project/2945/damage-assessment-and-conservation-of-underground-space-as-valuable-resources-for-human-activities-use-in-italy-and-japan (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- Varriale, R. Underground Built Heritage in Italy and Japan. From the methodological approach to the comparative analysis of Pizzofalcone and Yoshimi Hyakuana hills case-studies. Opera Ipogea. 2020, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cost Action 18110 (2019–2023) Underground Built Heritage as Catalyser for Community Valorisation. Available online: https://www.cost.eu/actions/CA18110/ (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- Pace, G. An Introduction to Underground4value. In Underground Built Heritage Valorization: A Handbook; Pace, G., Salvarani, R., Eds.; CNR Edizioni: Roma, Italy, 2021; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Rodriguez, S.; Pace, G. (Eds.) Practice for Underground Built Heritage Valorization; CNR Edizioni: Roma, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Rodriguez, S. (Ed.) Valorización del Patrimonio Subterrraneo y Dinamización de la Comunidad; CNR Edizioni: Roma, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fear, Darkness and Newborn Babies: Inside Ukraine’s Underground Shelters. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/feb/26/fear-darkness-and-newborn-babies-inside-ukraine-underground-shelters (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- In Ukraine, Residents Keep Calm and Stock the Bomb Shelters. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/2022/02/24/in-ukraine-residents-keep-calm-and-stock-the-bomb-shelters (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- Kyiv Residents Spend Night Sheltering in Basements and Metro Stations. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-60522450 (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- Waiting, Fearing, Singing. Available online: https://www.opb.org/article/2022/02/28/waiting-fearing-singing-a-night-sheltering-in-ukraine/ (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- Ucraina, la Guerra Dei Bambini: Dalle Terapie Intensive Neonatali Nei Bunker Ai «Giochi-Bomba» Dagli Aerei Russi. Available online: https://www.ilmessaggero.it/mondo/ucraina_bambini_guerra_bunker_giocattoli_bomba_ultime_notizie-6529896.html (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- Viejo-Rose, D. Cultural heritage and memory: Untangling the ties that bind. Cult. Hist. Digit. J. 2015, 4, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshenska, G. Resonant Materiality and Violent Remembering: Archaeology, Memory and Bombing. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2009, 15, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshenska, G. A hard rain: Children’s shrapnel collections in the Second World War. J. Mater. Cult. 2008, 13, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racconti Dal Sottosuolo. La Guerra Vista Con Gli Occhi Dei Bimbi Rifugiati. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100064861743089 (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Thompson, P. The Voice of the Past; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermani, C. Introduzione Alla Storia Orale; Odradek: Roma, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi, B.; Poni, C.; Triulzi, A. (Eds.) Fonti Orali—Oral Sources—Sources Orales; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, A. Four Paradigm Transformations in Oral History. Oral Hist. Rev. 2007, 34, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monda, L. Napoli durante la II Guerra Mondiale ovvero: I 100 bombardamenti di Napoli. In Proceedings of the Convegno I.S.S.E.S. (Istituto di Studi Storici Economici e Sociali), Napoli, Italy, 5 March 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Popolazione Napoli 1861–2016. Available online: http://www.comuni-italiani.it/063/049/statistiche/popolazione.html (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Esposito, C. Il Sottosuolo di Napoli; Intra Moenia: Napoli, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Naples inside Wartime WW2. Life Mag. 1944, 18, 4.